Abstract

The effect of CheY and fumarate on switching frequency and rotational bias of the bacterial flagellar motor was analyzed by computer-aided tracking of tethered Escherichia coli. Plots of cells overexpressing CheY in a gutted background showed a bell-shaped correlation curve of switching frequency and bias centering at about 50% clockwise rotation. Gutted cells (i.e., with cheA to cheZ deleted) with a low CheY level but a high cytoplasmic fumarate concentration displayed the same correlation of switching frequency and bias as cells overexpressing CheY at the wild-type fumarate level. Hence, a high fumarate level can phenotypically mimic CheY overexpression by simultaneously changing the switching frequency and the bias. A linear correlation of cytoplasmic fumarate concentration and clockwise rotation bias was found and predicts exclusively counterclockwise rotation without switching when fumarate is absent. This suggests that (i) fumarate is essential for clockwise rotation in vivo and (ii) any metabolically induced fluctuation of its cytoplasmic concentration will result in a transient change in bias and switching probability. A high fumarate level resulted in a dose-response curve linking bias and cytoplasmic CheY concentration that was offset but with a slope similar to that for a low fumarate level. It is concluded that fumarate and CheY act additively presumably at different reaction steps in the conformational transition of the switch complex from counterclockwise to clockwise motor rotation.

Bacterial chemotaxis occurs by chemostimulus-controlled modulation of the probability to change the direction of flagellar rotation (see reference 9 for a recent review). Switching the rotational sense requires several proteins of the flagellar basal body that are assembled in the switch complex (for a review, see reference 13 and references therein). Clockwise (CW) rotation depends in addition on the response regulator CheY (6, 21, 23, 28, 29), and the average time spent in the CW mode (CW bias) is regulated via its phosphorylation level (1). CheY is specifically phosphorylated by the histidine kinase CheA, whose activity is controlled by the sensory input via the methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein (MCP) chemoreceptors (4, 10, 19). Although the sensory control of switching via the two-component system is understood in great molecular detail, the mechanism of switching is not known.

Cytoplasm-free cell envelopes, produced by osmotic lysis of intact cells, spin the flagellar motors exclusively counterclockwise (CCW) (8). CW rotation of envelopes depends on the addition of CheY to the lysis buffer (23). However, CW-spinning envelopes do not switch the rotational sense. Switching can be restored upon addition of fumarate (2), an intermediate of the citric acid cycle. The function of fumarate as a prokaryotic switch factor was originally discovered in Halobacterium salinarum (14). The cytoplasmic concentration of fumarate is under sensory control of the excitation state of the sensory rhodopsin-transducer complex that mediates phototaxis in this archaebacterium (15, 17). Because of the finding that CheY and fumarate are required for switching in cell envelopes of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, it was proposed that CheY may be a bias regulator (the bias is defined as the fraction of time an individual flagellar motor spins on average in the CW rotational sense) and fumarate may enable switching without interfering with the bias (3). Here we analyze how CheY and fumarate are involved in rotational bias regulation and switching in living cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains used and growth of bacterial cultures.

The E. coli strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacterial cultures were grown in tryptone broth by inoculation with 1% (vol/vol) of an overnight culture and were shaken at 250 rpm at 37°C until an optical density of 0.5 at 590 nm was reached. Strains with deletions in fumarases were grown either in tryptone broth with 0.4% glycerol as a supplementary energy source or in H1 minimal medium supplemented with 0.4% glycerol as the sole carbon source (11).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| RP437 | Wild type for chemotaxis | 20 |

| RP1091 | Δ(cheA-cheZ)2209 | 20 |

| EW13 | Δ(cheA-cheZ)2209(pJH120>) | This study |

| EW13ΔFac | Δ(cheA-cheZ)2209 ΔfumA ΔfumC(pJH120) | 18 |

| EW22 | Δ(cheA-cheZ)2209 ΔgltA6(pJH120) | 3 |

| EW23 | Δ(cheA-cheZ)2209 fumA1(pJH120) | 3 |

| EW44 | Δ(cheA-cheZ)2209 fumA1 sdh-1::λplacMu9 | 3 |

| EW45 | EW44(pJH120) | This study |

Estimation of cytoplasmic fumarate.

The cytoplasmic fumarate concentration was assayed in cell lysates by an enzymatic cycling reaction as described previously (17, 18).

Behavioral measurements and data acquisition.

Cells were resuspended in motility buffer and tethered to a coverslip as described previously (25). Single spinning cells were observed at 23°C on a thermostated stage and digitized on-line with a video frame grabber (Motion Analysis Corp., Santa Rosa, Calif.) at a frequency of 60 frames per s. Sequences of 10 s were recorded and evaluated with respect to rotational sense and switching frequency by using the motion analysis algorithms described below. Choosing an observation period of 10 s provided a compromise between resolution of switching frequency and bias on the one hand and statistically relevant sample size on the other.

Motion analysis algorithms.

The frame grabber provided video data that consisted of pixels marking the boundary of dark-light transitions within the video image at an adjusted-intensity threshold. Data evaluation started with the definition of the outline of a cell in each video frame. Next, the center of the cell was calculated and the length axis of the outline was drawn through the center of the cell. By considering the length axes in all successive frames of a sequence, the rotational center of the cell was determined. This rotational center was used in turn to calculate the angular displacement of the length axis from frame to frame. To smooth the pixel noise, the angular displacement of three successive frames was averaged to give 1/20 s or 50 ms time resolution. By using this algorithm, the angular velocity and the sense of rotation were evaluated in 50-ms time intervals in each sequence. To avoid stroboscopic effects, cells rotating extremely quickly were excluded from the analysis. It has been shown that tethered cells occasionally pause in addition to switching. Pausing was shown to be an intrinsic property of the flagellar motor rather than the result of nonspecific adhesion of the cell body to the coverslip (12). Brief pausing intervals were also clearly detectable by computerized motion analysis. However, the data evaluation was restricted to those cells that paused for less than a total of 10% of the observation period. To correct for possible tracking errors that might be caused by pixel noise or rotational diffusion of pausing cells, the system was calibrated by using mutants locked in either the CCW or CW rotational sense. As expected, in cells of the gutted strain RP1091, only a few switching events were detected by the system, and these were followed by very brief periods of CW rotation only (see Fig. 1A). Although some of these events may be due to pixel noise, we cannot exclude that brief periods of CW rotation indeed might occur even in the absence of CheY at room temperature.

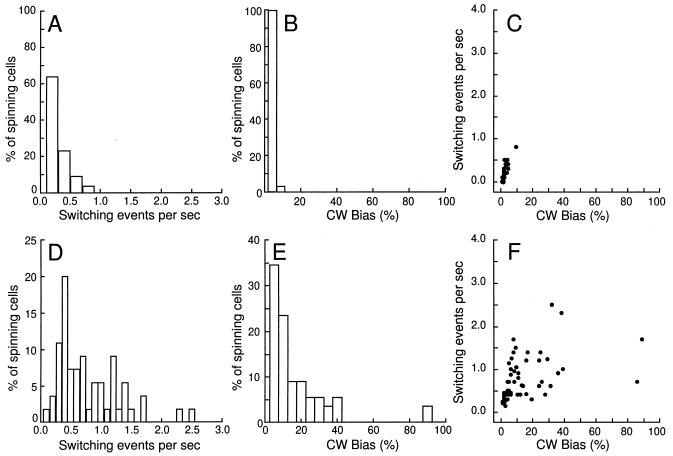

FIG. 1.

Calibration of the motion analysis setup and behavior of wild-type cells. Switching frequency and rotational bias of tethered cells of the gutted strain RP1091 (ΔcheA-cheZ) (A to C) and those of the wild-type strain RP437 (D to F) are shown. Frequency distributions of switching events per second (A and D) and rotational bias (B and E) as detected by the system are plotted. Panels C and F correlate switching frequency and bias of each individual cell as averaged from observation periods of 10 s. The sample size was 50 cells for each of the two strains.

RESULTS

Rotational sense and switching of motor rotation were measured in the tethered-cell assay by computer-assisted motion analysis. The setup was calibrated for tracking errors and possible CheY-independent switching events by using the gutted strain RP1091 (Fig. 1A to C) (for details, see Materials and Methods). In RP437 wild-type cells, there was a positive correlation of switching frequency and rotational bias for up to 50% CW rotation when short observation periods of 10 s were compared (Fig. 1D to F).

To investigate the dependence of switching frequency and bias on CheY activity, the gutted (i.e., with cheA to cheZ deleted) strain RP1091 was transformed with pJH120 (7), yielding EW13, in which the expression level of the cheY gene is under the control of the arabinose promoter. With an increasing concentration of arabinose, the rotational bias of EW13 cells was gradually shifted to higher values, inducing in some cells close to 100% CW rotation (Fig. 2A and B). With maximal induction of CheY, the correlation of switching frequency and bias, although not rigid, seemed to fit a bell-shaped curve centered at a value of about 50% CW rotation (Fig. 2B). The important observation in this experiment is that the expression level of CheY changed both the switching frequency and the bias. Observation of individual cells for many successive periods of 10 s each revealed a considerable variation in time of switching frequency, bias, and the correlation of the two even for one and the same cell (Fig. 3).

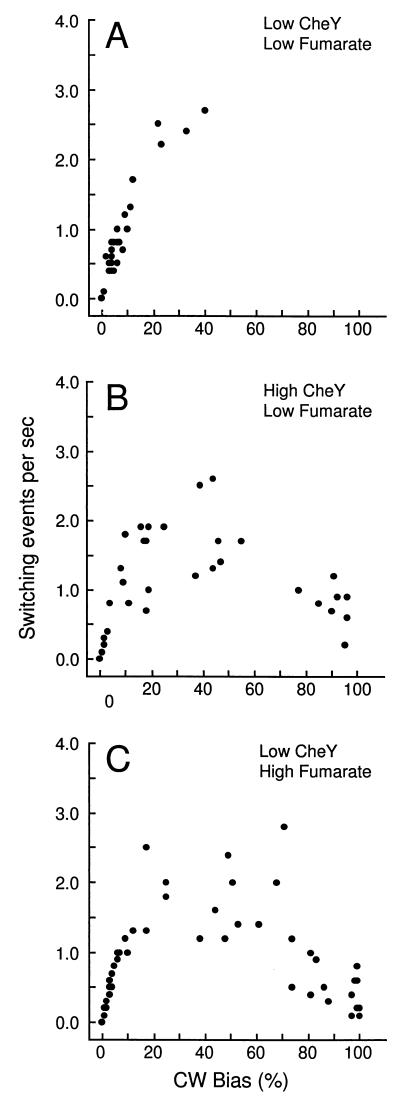

FIG. 2.

Effect of CheY overexpression and cytoplasmic fumarate concentration on switching frequency and bias. The gutted strain RP1091 was transformed with pJH120 (7), which carries the CheY gene under the control of the arabinose promoter, yielding EW13. Switching frequency and bias as measured during observation periods of 10 s are plotted for each individual cell. (A) EW13 without induction of CheY expression; (B) EW13 with maximal induction of CheY by 100 μM l-arabinose; (C) EW13ΔFac, derived from EW13 by deletion of fumarase but without induction of CheY expression. The steady-state concentrations of cytoplasmic fumarate were 7,250 ± 450 and 55,400 ± 3,000 molecules per cell (mean ± standard error of the mean) in EW13 and EW13ΔFac cells, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Correlation of switching frequency and bias and their variation in single cells over time. Cells of strain EW13 induced with 100 μM l-arabinose were observed for successive periods of 10 s. The correlation of switching frequency and bias was averaged and plotted for each observation period separately. Each symbol corresponds to one individual cell.

To analyze how switching frequency and bias depend on fumarate at a given CheY level, generation of cells with a high cytoplasmic fumarate level was necessary. Fumarases expressed by fumA and fumC under aerobic conditions convert fumarate into malate within the citric acid cycle. Disrupting the fumarases was expected to reduce the decay rate of fumarate, thereby raising its cytoplasmic steady-state concentration. Therefore, the two genes were disabled in EW13 to give EW13ΔFac. To verify the expected phenotype of the deletion strain, cells were lysed by rapid injection into boiling water and the fumarate concentration in the lysate was assayed enzymatically as described previously (17, 18). In EW13ΔFac, the cytoplasmic fumarate level was enhanced 7.6-fold over that of EW13, to about 55,400 molecules per cell. Strains with deletions in fumarases and/or other tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle enzymes (see below) grew at a normal rate, indicating that these cells were sufficiently fueled through alternative metabolic pathways.

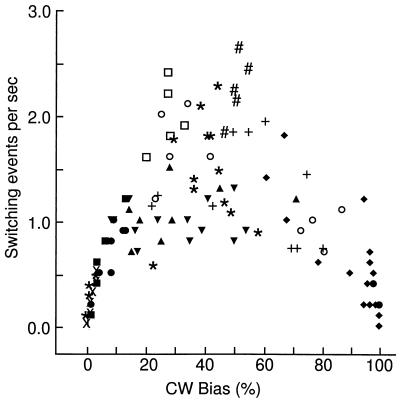

When observed at room temperature, cells lacking CheY rotated CCW exclusively, irrespective of whether the fumarate level was low (corresponding to the wild-type level) or high (data not shown). When the CheY level was high (pJH120; CheY overexpression induced by arabinose), the switching frequency and the bias at a low fumarate level were similar to those in cells with a low CheY level but a high fumarate level (Fig. 2B and C). Stepwise overexpression of CheY in cells of another gutted strain with a high cytoplasmic fumarate concentration (EW23) gradually increased the average CW rotation bias, again without any obvious change in the bell-shaped correlation curve of switching frequency and bias (Fig. 4). Hence, the switching frequency and the bias could be increased by raising the concentration of either CheY or fumarate. In addition, the cytoplasmic fumarate concentration affected both the switching frequency and the bias.

FIG. 4.

Response of switching frequency and bias to stepwise CheY overexpression at a high fumarate level. Due to a deletion in fumA, the steady-state cytoplasmic concentration of fumarate was 70,800 ± 2,500 molecules per cell (mean ± standard error of the mean) in EW23 (10-fold higher than that of the wild type). CheY overexpression from pJH120 was at baseline (A) or induced by addition of 60 (B) or 100 (C) μM l-arabinose. Each data point represents the correlation of switching frequency and bias of a cell averaged over an observation interval of 10 s.

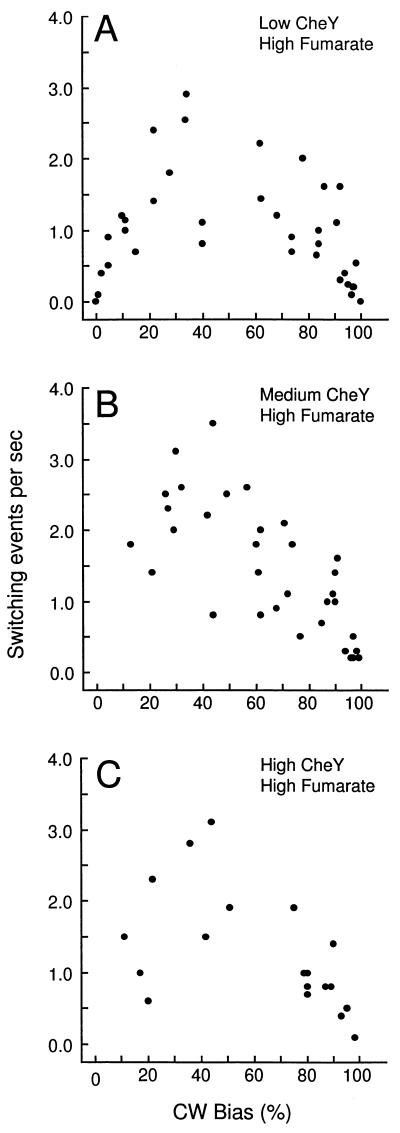

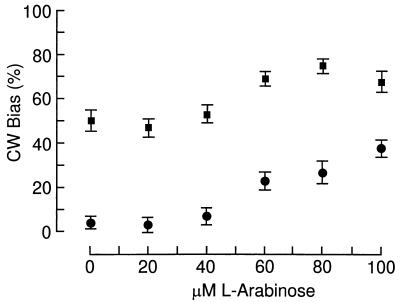

The dependence of the average CW rotation bias on the CheY concentration was measured in cells with a high or low cytoplasmic fumarate level. Averaging the data from the bimodal bias distributions gave titration curves with similar shapes and slopes but separated by an offset of about 50% CW rotation (Fig. 5). This suggests an additive rather than a multiplicative effect of CheY and fumarate on regulation of the bias (see Discussion).

FIG. 5.

CW bias plotted as a function of the CheY expression level at low and high fumarate levels. CheY expression in cells of strains EW13 ΔcheA-cheZ (pJH120) (•) and EW23 ΔcheA-cheZ (pJH120) ΔfumA (▪) was induced by different concentrations of l-arabinose, and the CW bias of tethered cells was estimated. Note that in the absence of arabinose, the promoter exhibits baseline activity. For each data point, 40 cells taken from two independent cultures were evaluated. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean.

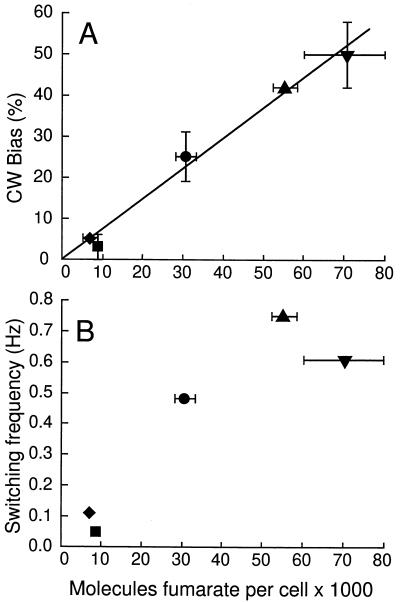

Additional strains with a steady-state cytoplasmic concentration of fumarate different from that of the wild type were obtained by deleting fumarases, fumarases and succinate dehydrogenase, or citrate synthase (Table 1). A linear correlation between CW rotation bias and cytoplasmic fumarate level was found with all of these strains. Extrapolation of the data points predicted a bias of 0% CW rotation in the absence of fumarate (Fig. 6A). The switching frequency, as well, depended on the fumarate concentration, as expected from the bell-shaped curve showing correlation to the bias. Extrapolation of the experimental data again suggested that there is no switching (frequency equals or is close to zero) in the absence of fumarate, which for formal reasons of course is expected for 0% CW rotation bias (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

CW bias (A) and switching frequency (B) plotted versus the cytoplasmic fumarate concentration of several gutted strains expressing CheY from pJH120 in the absence of arabinose. The relevant genotypes of strains EW13 (⧫), EW13ΔFac (▴), and EW22 (▪) EW23 (▾), and EW45 (•) are given in Table 1. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. The data points in panel A were fitted to a straight line, with the assumption that there is no switching (0% CW bias) in the absence of fumarate.

DISCUSSION

Although the protein machinery mediating signal transduction during chemotaxis is understood in great detail, the mechanism for switching the sense of flagellar rotation remains an enigma. It is known that the cellular concentration of CheY and CheY-phosphate determines the probability for CW flagellar rotation. Any given bias between 0 and 100% in principle could occur at any switching frequency, and therefore switching frequency and bias might be independently regulated.

In addition to CheY, fumarate has been shown to be involved in motor switching of E. coli and S. typhimurium. Flagellar motors of cytoplasm-free cell envelopes switch the sense of rotation only when CheY and fumarate (or an analogous compound) are present (2, 3). Malate, maleate, and succinate also have switch factor activity in the envelope system, but at a lower efficiency than that of fumarate, while aspartate and lactate are inactive (3). Since the cell envelopes were shown to be completely devoid of any cytoplasmic components, CheY and fumarate must be active per se.

Recently, evidence for the function of fumarate in regulating motor switching of intact cells has been obtained. Reversible inhibition of the TCA cycle enzyme fumarase by the repellent indole or benzoate transiently increases the cytoplasmic fumarate concentration. The fumarate pulse positively correlates with the switching activity of cells that are genetically deleted in phosphorylation-dependent chemotaxis but express CheY at a low level (18). The correlation holds for cells expressing double-mutated CheY (CheY D13K and D57A) (5), which cannot be phosphorylated (either by the kinase CheA or by metabolic sources) but retains some activity in allowing CW rotation (18). Although phosphorylation of CheY enhances its efficiency in causing CW rotation, nonphosphorylated CheY as well as nonphosphorylatable mutants of CheY do bind to FliM (a component of the switch complex) to a low extent (26, 27) and a high level of nonphosphorylated CheY can even cause CW rotation (1). The cumulative evidence presented here and by the results mentioned above strongly suggests that fumarate per se is involved in reversing motor rotation in the living cell rather than by changing the phosphorylation level of CheY via other metabolic intermediates. While the effect of fumarate on switching and CW rotational bias requires a minimal level of CheY to be detectable at room temperature, fumarate can be active even in the complete absence of CheY when the temperature is low (22).

Fumarate as a central metabolic intermediate seems to directly signal the metabolic flux through the cell to the flagellar motor, eventually bypassing the two-component system. Direct metabolic signaling was shown to occur in strains expressing CheY in a gutted background (18). In wild-type cells, the effect of an enhanced fumarate level is evident as well, although its strength seems to be slightly buffered possibly via feedback looping by the Che protein system (16).

Despite the evidence for the involvement of fumarate in motor switching, its mechanistic function relative to that of CheY was not clear until now. From the cell envelope experiments, it seemed plausible that fumarate may act as a switching factor whereas CheY is a bias regulator (3). We have measured switching frequency and bias simultaneously as a function of cytoplasmic concentration of fumarate and CheY. Plots of the data from our experiments revealed a bell-shaped correlation between switching frequency and bias, which allows some presumably stochastic variation even in a single cell. Replotting of the most recent data from Scharf et al. (24), who measured bias and switching frequency as a function of the absolute CheY concentration, yields a similar correlation. To what extent the plot of the correlation curve is populated by data points depends on the concentration of both CheY and fumarate. Most interestingly, variation of the CheY level qualitatively produced the same effect on switching and bias as variation of the cytoplasmic concentration of fumarate did and their correlation remained constant. It seems that fumarate and CheY act additively in regulating the bias. To test this assumption, the CW bias of the cell population was plotted as a function of the CheY level. The resulting dose-response curve was offset by the increased fumarate level, but the slopes of the two curves were similar (Fig. 5). This strongly argues against any direct or indirect effect of fumarate on the effectiveness of CheY, which should dramatically change the slope of the dose-response curve. The same arguments hold against a changed level of phosphorylated CheY produced by metabolic sources in response to an increased concentration of fumarate. An interaction of CheY and fumarate with the same binding site seems unlikely; instead, we propose that the two factors are involved in consecutive steps of the switching process. The flagellar motors of gutted strains with no CheY at low temperatures (e.g., 2.5°C) rotate more CW and switch more frequently when the cytoplasmic fumarate level is high, also indicating that the target of fumarate is the switch complex and not CheY (22).

Extrapolation of the correlation of switching frequency and fumarate level measured in strains that were wild type or carried various deletions in TCA cycle enzymes to a zero concentration of fumarate yields 0% of CW rotation. This suggests that in addition to CheY, fumarate is essential for CW rotation of the flagellar motor in vivo. The CW rotation of cytoplasm-free cell envelopes obtained by Barak et al. (2, 3) does not contradict this result and might be explained by a locking of the rotational sense during the moment of lysis when both CheY and fumarate are still present.

Conclusion.

We have recently shown that phosphorylation-independent chemoresponses of cells with a disabled two-component system correlate with changes in the cytoplasmic level of fumarate (18). This holds for cells with nonphosphorylatable CheY. The finding that fumarate and CheY are required for motor switching in cytoplasm-free cell envelopes (2, 3) and the effectiveness of fumarate to promote CW rotation and switching in intact cells at low temperature even in the absence of CheY (22) strongly suggest a direct interaction of fumarate and CheY with the flagellar motor switch. The results shown here extend this conclusion and suggest that fumarate and CheY are additively involved in both switching and bias regulation but act on different steps in the conformational transition of the switch from CCW to CW rotation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the German-Israeli Binational Foundation to M.E. and D.O. and by a doctoral fellowship from the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds to M.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barak R, Eisenbach M. Correlation between phosphorylation of the chemotaxis protein CheY and its activity at the flagellar motor. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1821–1826. doi: 10.1021/bi00121a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barak R, Eisenbach M. Fumarate or a fumarate metabolite restores switching ability to rotating flagella of bacterial envelopes. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:643–645. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.643-645.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barak R, Giebel I, Eisenbach M. The specificity of fumarate as a switching factor of the flagellar motor. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:139–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.365889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borkovich K A, Kaplan N, Hess J F, Simon M I. Transmembrane signal transduction in bacterial chemotaxis involves ligand-dependent activation of phosphate group transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1208–1212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourret R B, Drake S K, Chervitz S A, Simon M I, Falke J J. Activation of the phosphosignaling protein Che Y. II. Analysis of activated mutants by 19F NMR and protein engineering. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13089–13096. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clegg D O, Koshland D E., Jr The role of a signaling protein in bacterial sensing: behavioral effects of increased gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5056–5060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.16.5056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conley M P, Wolfe A J, Blair D F, Berg H C. Both CheA and CheW are required for reconstitution of chemotactic signalling in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5190–5193. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5190-5193.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenbach M, Adler J. Bacterial cell envelopes with functional flagella. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:8807–8814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenbach M. Control of bacterial chemotaxis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:903–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hess J F, Oosawa K, Kaplan N, Simon M I. Phosphorylation of three proteins in the signaling pathway of bacterial chemotaxis. Cell. 1988;53:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaiser A D, Hogness D S. The transformation of Escherichia coli with deoxyribonucleic acid isolated from bacteriophage lambdadg. J Mol Biol. 1960;2:392–415. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(60)80050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lapidus I R, Welch M, Eisenbach M. Pausing of flagellar rotation is a component of bacterial motility and chemotaxis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3627–3632. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3627-3632.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macnab R M. Flagellar switch. In: Hoch J A, Silhavy T J, editors. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 181–199. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marwan W, Schäfer W, Oesterhelt D. Signal transduction in Halobacterium depends on fumarate. EMBO J. 1990;9:355–362. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marwan W, Oesterhelt D. Light-induced release of the switch factor during photophobic responses of Halobacterium halobium. Naturwissenschaften. 1991;78:127–129. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montrone M. Untersuchungen zur Funktion von Fumarat als Schaltfaktor in der photophobischen Reaktion von Halobacterium salinarium und der chemophobischen Reaktion bei Escherichia coli. Ph.D. thesis. Munich, Germany: University of Munich; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montrone M, Marwan W, Grünberg H, Mußeleck S, Starostzik C, Oesterhelt D. Sensory rhodopsin-controlled release of the switch factor fumarate in Halobacterium salinarium. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:1077–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montrone M, Oesterhelt D, Marwan W. Phosphorylation-independent bacterial chemoresponses correlate with changes in the cytoplasmic level of fumarate. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6882–6887. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6882-6887.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ninfa E G, Stock A, Mowbray S, Stock J. Reconstitution of the bacterial chemotaxis signal transduction system from purified components. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:9764–9770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parkinson J S, Houts S E. Isolation and behavior of Escherichia coli deletion mutants lacking chemotaxis function. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:106–113. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.106-113.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkinson J S, Parker S R, Talbert P B, Houts S E. Interactions between chemotaxis genes and flagellar genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:265–274. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.1.265-274.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prasad, K., S. R. Caplan, and M. Eisenbach. Fumarate modulates bacterial flagellar rotation by lowering the free energy difference between the clockwise and counterclockwise states of the motor. J. Mol. Biol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Ravid S, Matsumura P, Eisenbach M. Restoration of flagellar clockwise rotation in bacterial envelopes by insertion of the chemotaxis protein CheY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7157–7161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.19.7157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scharf B E, Fahrner K A, Turner L, Berg H C. Control of direction of flagellar rotation in bacterial chemotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:201–206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silverman M, Simon M. Flagellar rotation and the mechanism of bacterial motility. Nature. 1974;249:73–74. doi: 10.1038/249073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welch M, Oosawa K, Aizawa S-I, Eisenbach M. Phosphorylation-dependent binding of a signal molecule to the flagellar switch of bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8787–8791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welch M, Oosawa K, Aizawa S-I, Eisenbach M. Effects of phosphorylation, Mg2+, and conformation of the chemotaxis protein CheY on its binding to the flagellar switch protein FliM. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10470–10476. doi: 10.1021/bi00200a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfe A J, Conley M P, Kramer T J, Berg H C. Reconstitution of signaling in bacterial chemotaxis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1878–1885. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.5.1878-1885.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamaguchi S, Aizawa S-I, Kihara M, Isomura M, Jones C J, Macnab R M. Genetic evidence for a switching and energy-transducing complex in the flagellar motor of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:1172–1179. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1172-1179.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]