Abstract

Oligometastatic prostate cancer is a term that is most often used to refer to limited sites of disseminated tumor growth following primary radical prostatectomy (RP) or radiotherapy (RT), while de novo oligometastatic is a term that is used to refer to prostate tumors that have disseminated to limited sites before definitive treatment. In patients with de novo oligometastatic prostate cancer, treatment planning must thus consider the need to manage the primary tumor and the associated distant lesions. Traditionally, resectioning primary metastatic tumors is not thought to offer significant benefits to affected patients while increasing their risk of surgery-related complications. Recent clinical evidence indicates that patients undergoing cytoreductive prostatectomy (CRP) may observe substantial enhancements in overall survival rates while not experiencing a noticeable decline in their quality of life. Nevertheless, based on the current body of evidence, it is deemed inadequate to justify revising clinical guidelines. Consequently, it is not advisable to propose CRP for patients with oligometastatic prostate cancer. The present review was compiled to summarize available data regarding the indications, functional outcomes, and oncological outcomes associated with cytoreductive radical prostatectomy to provide a robust and objective foundation that can be used to better assess the value of this interventional strategy from a clinical perspective.

Keywords: oligometastatic prostatic cancer, cytoreductive prostatectomy, overall survival, survival benefits, indications

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common urological malignancy among middle-aged and older males and is second only to skin cancer in terms of overall male cancer incidence. 1 In China, PCa is the fourth most prevalent cancer in men, and Chinese PCa patients account for 34.2% of all cases throughout Asia. 2 While many PCa patients present with local disease that can be effectively cured via therapeutic intervention, 3 1 in 3 patients in China exhibit distant metastases when initially diagnosed owing to a lack of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening.1,4 In these patients, tumors that initially respond to endocrine therapy will ultimately become castration-resistant over time such that metastatic PCa (mPCa) patients exhibit a 5-year overall survival rate of just 29%. Significant progress has been made in the last 20 years regarding the treatment results for this group of patients diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer. 5

In 1995, Hellman et al initially proposed the concept of oligometastatic disease as an intermediate step in disseminating tumors from localized sites to an extensively metastatic disease characterized by a limited number of metastatic sites.6,7 Therefore, an isolated metastatic disease with 5 or fewer bone metastases and no visceral metastases is commonly called an oligometastatic disease. However, patients may or may not also have lymph node metastases.8,9

The precise determination of metastatic sites has historically posed difficulties due to limitations in the detection methods employed. Furthermore, the potential advantages of localized treatment in individuals with few metastases in PCa are typically constrained. Clinical guidelines do not recommend that oligometastatic PCa patients undergo first-line cytoreductive prostatectomy treatment.10–12 The NCCN and AUA guidelines suggest that patients with PCa undergo surgical castration, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), or other hormone therapy.10,13 However, the European Urological Association recently incorporated local radiotherapy as a treatment option in PCa patients with a low metastatic load. 14 Several retrospective studies have suggested that cytoreductive prostatectomy may confer survival benefits to treated patients.11,15–17 In 2014, Culp et al analyzed patients in the SEER database, ultimately detecting a 5-year OS rate of 67.4% for radical prostatectomy (RP) patients, while that for patients that did not receive local treatment was 22.5%. 11 A 2022 study using a murine model of mPCa found that mice that underwent primary tumor resection exhibited significantly prolonged survival as compared to those that did not (P < 0.01), with a corresponding slowing of PSA increases (P < 0.01) and fewer lung metastases (P = 0.073). 18 To date, however, it remains controversial as to the value of cytoreductive prostatectomy for the treatment of oligometastatic PCa.

Based on a recent systematic review published within the last 5 years,19–21 it has been found that cytoreductive prostatectomy is a viable and productive treatment approach for oligometastatic prostate cancer. This intervention demonstrates notable enhancements in overall survival rate, cancer-specific mortality, and clinical progression-free survival compared to systemic therapy. However, it should be noted that these systematic reviews have several limitations. One such limitation is the absence of a comprehensive assessment of surgical risks, postoperative sequelae, and postoperative quality of life. Additionally, there is a lack of analysis and summary of the ideal criteria for surgery patients. Hence, it is imperative to conduct additional research to bridge these information gaps and obtain a more holistic comprehension of the advantages and drawbacks of cytoreductive prostatectomy as a therapeutic approach for oligometastatic prostate cancer.

Based on the abovementioned factors, this review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the patient population suitable for cytoreductive prostatectomy and elucidate the safety and advantages of this procedure in the context of oligometastatic prostate cancer. This will be achieved by examining relevant prospective and retrospective studies available in the literature.

Materials and Methods

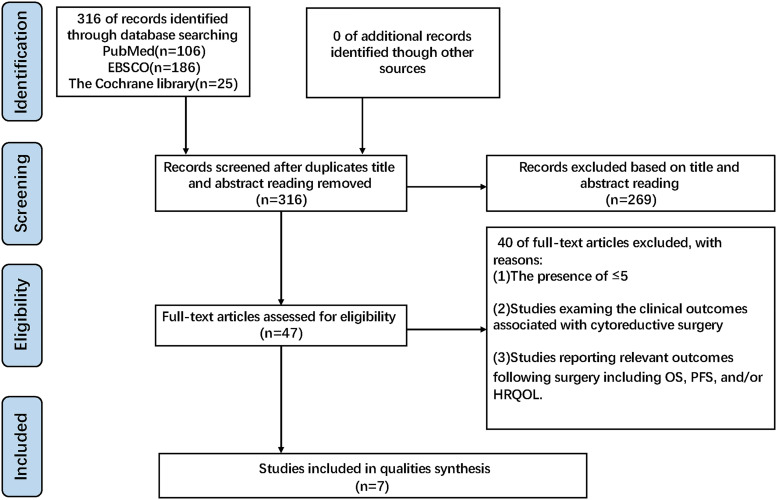

A comprehensive search was conducted to identify relevant research published in English between January 1, 2015, and December 2, 2022. The investigation was performed in reputable online databases such as PubMed and EBSCO. To ensure the inclusion of appropriate studies, the search strategy used specific keywords: oligometastatic prostate cancer, cytoreductive prostatectomy, postoperative complications, quality of life, and local symptoms. Included studies met the following criteria: (1) studies involving patients diagnosed with oligometastatic prostate cancer, defined as having ≤5 metastases; (2) studies investigating the clinical outcomes of cytoreductive surgery in patients with oligometastatic prostate cancer; and (3) studies reporting pertinent outcomes such as overall survival (OS), cancer-specific survival (CSS), and/or progression-free survival (PFS) following surgery. Both retrospective and prospective studies were included in this study selection process, which is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

Results

Cytoreductive Prostatectomy Patients Exhibit Improved Survival Outcomes

The precise processes by which cytoreductive prostatectomy can effectively treat oligometastatic PCa remain unclear despite its apparent success in multiple studies. Cytoreductive resection methods have demonstrated favorable outcomes in cancer patients, including metastatic renal, ovarian, colorectal, and lung cancer.22–25 The mechanistic basis for the benefits of cytoreductive surgery is thought to be related to a reduction in the overall systemic tumor load, decreasing the number of tumor cells shed into the systemic circulation from primary tumors and thereby reducing pro-tumorigenic growth factor secretion, enhancing sensitivity to subsequent radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and/or endocrine therapy.26–29 The SWOG 8894 randomized controlled trial (RCT) found that of 1286 patients with metastatic disease who underwent bilateral orchiectomy, those in the placebo or flutamide groups exhibited a significant reduction in the risk of death if they had experienced prior RP (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.53-0.80). 30 In line with these results, several retrospective studies and registration data (including monitoring, epidemiological findings, and final results) found that the OS and cancer-specific survival (CSS) of oligometastatic PCa patients were improved following cytoreductive prostatectomy.11,31–35 Several prospective and clinical studies have additionally confirmed that cytoreductive prostatectomy can significantly improve the progression-free survival (PFS) and CSS of patients with mPCa, delaying disease progression while enhancing the quality of life.36–38

A contentious debate surrounds the efficacy of lymph node dissection during radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. The feasibility, therapeutic outcomes, and optimal extent of lymph node dissection remain uncertain. Some studies indicate that lymph node dissection has a limited impact on direct treatment outcomes.39,40 Furthermore, there is a correlation between the degree of lymph node dissection and adverse outcomes during the surgery and the immediate postoperative period. There is a positive correlation between a more comprehensive dissection and several factors, including longer surgical durations, increased blood loss, extended hospital stays, and a heightened risk of postoperative complications. 40 However, research also presents contrasting results. For instance, Mazzone and colleagues found that lymph node dissection during radical prostatectomy is associated with lower cancer-specific and overall mortality rates, even in bone metastasis, compared to cases where lymph node dissection was not performed. Notably, there were no significant differences in postoperative complications between the 2 groups.41,42

Additionally, Pavlovich's study indicates that in patients with lymph node metastasis, RP + PLND has advantages in terms of oncology.

Tendency-adjusted analysis shows that RP + PLND has better cancer-specific mortality (CSM) and overall mortality (OM) rates than RP alone. Furthermore, NIS data did not indicate an increased short-term morbidity except for higher transfusion requirements in the RP + PLND group. 43 Another study yielded similar findings, conducting a thorough analysis of 311 cases comprising prostate cancer patients with bone metastases who underwent cRP + LND treatment. The results suggested that LND may improve overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) in patients. 44 Nevertheless, the existing body of evidence is inadequate to establish the requirement for lymph node dissection in the context of radical prostatectomy for patients with minimal metastases. 44 In low-risk patients, lymph node dissection may not yield significant benefits. As a result, in determining whether to conduct lymph node dissection alongside cytoreductive surgery, it is crucial to choose suitable individuals and contemplate extensive dissection carefully only when there are no substantial intraoperative risks.40,43

Overall Survival Outcomes

In 1 prospective case-control study of 61 patients, CRP (cytoreductive prostatectomy) and extended lymph node dissection (ePLND) were associated with a 12.4% (91.3% vs 78.9%) improvement in 3-year survival relative to control ADT-only treatment. 36 A retrospective study revealed that adding CRP to ADT significantly improved the survival outcomes in patients with oligometastatic prostate cancer. The 5-year survival rate increased by 14.9% (87% vs 73.1%). 45 In their prospective analysis, Sow et al found that the OS of patients who underwent CRP was similarly prolonged relative to that of patients who only underwent ADT (24 vs 14 months, P = 0.03). 46 CRP can also improve long-term prognostic outcomes in patients. Combining surgery and systemic medication may have long-term effects in a subset of individuals with oligometastatic PCa. One therapeutic research, for example, involved 25 patients with biopsies confirming cNxM1 disease and 7 patients with pathological stage cN1M0 disease who underwent CRP and continued systemic ADT treatment following surgery. Of these 32 patients, 25 (75%) remained alive as of the most recent follow-up, with overall estimated 5-year OS rates of 67% and 69% for the overall cohort and M1 patients, respectively. In these patients, PSA was undetectable after surgery, and 7 patients exhibited satisfactory postsurgical recovery such that their systemic treatment course was altered to intermittent ADT. After discontinuing systemic treatment for over 2 years, 5 patients showed normalized serum testosterone levels without any evidence of disease, with 3 having had M1 disease when initially diagnosed. 38

However, it is essential to note that other research studies have reported divergent results. A study led by Tian Lan et al found no statistically significant differences in PSA recurrence-free survival (P = 0.184), clinical progression-free survival (P = 0.118), and tumor-specific survival (P = 0.773) among patients diagnosed with oligometastatic prostate cancer who underwent ADT monotherapy compared to those who received combined treatment with CRP and ADT. 47 In a separate retrospective cohort study, SI and their colleagues focused on patients with oligometastatic prostate cancer. In this study, 57 patients received a combination of ADT (androgen deprivation therapy) and RP (radical prostatectomy), while another 57 patients received ADT treatment alone. Interestingly, the baseline characteristics of both patient populations were highly comparable. This study found no statistically significant differences in overall survival (OS) or survival rates for castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) between the 2 groups (P = 0.649, p = 0.183). 48

Furthermore, a prospective cohort study revealed no substantial difference in tumor-specific survival rates between the cRP (curative radical prostatectomy) and the control groups (P = 0.975). 38 It is noteworthy to emphasize that the only study providing tumor prognostic data was carried out by Steuber et al. Based on their data, neither of the group receiving continuous cRP nor the control group demonstrated statistically significant oncological advantages concerning overall survival and survival in the presence of castration resistance. 49

Progression-Free Survival Outcomes

Heidenreich et al determined that the clinical PFS of patients who underwent CRP was 12.1 months longer than that of controls who underwent ADT alone (38.6 vs 26.5 months, P = 0.032). 36 The study conducted by Ming-Xiong Sheng et al revealed a substantial prolongation in progression-free survival (PFS) (35 months vs 25 months, P < 0.0027) and castration resistance time (36 months vs 25 months, P < 0.0011) among patients who underwent CRP + ADT treatment, in contrast to those who received ADT alone. Notably, CRP was found to decrease the risk of progression by 79.3%. 45 In another prospective study, patients in the CRP group exhibited a longer PFS than that in the control group (42 vs 20 months, P = 0.025). 46

Other Findings

Heidenreich et al found patients in the CRP treatment group to exhibit a CSS that was improved by 11.4% (95.6% vs 84.2%, P = 0.043), suggesting that CRP can result in superior OS and CSS outcomes in patient cohorts carefully selected based on individual PSA responses to ADT. 36 Furthermore, it should be noted that CRP demonstrates certain advantages compared to single systemic treatment regarding the management of tumor recurrence. A prospective cohort research has shown a substantial decrease in the rate of biochemical recurrence in the CRP group throughout follow-up (34.6% vs 73.9%, P = 0.01). Additionally, a subsequent whole bone scan analysis indicated a significant reduction in metastatic volume within the CRP group (P = 0.003). 38

In patients diagnosed with oligometastatic prostate cancer, multiple studies have indicated that the performance of cytoreductive prostatectomy (CRP) and lymph node dissection can improve survival rates compared to receiving only androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).36,38,45,46 Several prospective studies have found that patients undergoing CRP surgery experience longer overall survival and progression-free survival, as well as a lower risk of disease progression, compared to those who receive only ADT treatment. Moreover, the combination of CRP and ADT can enhance long-term survival rates and demonstrate sustained effects in certain patients. However, there are variations in the findings of the research. Several studies indicate that CRP may not provide significant oncological benefits in overall and castration-resistant survival for individuals diagnosed with oligometastatic prostate cancer.38,47–49 These discrepancies may be attributed to variations in patient selection criteria, treatment protocols, and follow-up duration among the studies. The existing body of research provides evidence of the prospective benefits of combining CRP surgery with ADT treatment for patients diagnosed with oligometastatic prostate cancer. Nevertheless, additional research is imperative to ascertain the dependability and uniformity of the results and to advocate for establishing defined criteria for patient selection, surgical methodologies, and systemic therapy approaches.

Cytoreductive Prostatectomy Can Alleviate Local Urinary Tract Obstruction Symptoms

Patrikidou et al analyzed 263 new mPCa patients. They found that 64% exhibited local symptoms, including dysuria, acute urinary retention, and renal failure when initially diagnosed, with acute urinary retention and renal failure accounting for 25% of these symptoms. As the disease progressed to later stages, 3- and 2-fold increases in rates of pelvic pain and acute urinary retention were observed. Local symptoms ultimately developed in 205 (78%) male patients throughout the disease, with 121 (49%) requiring local treatment. 50 While CRP entails some risk of perioperative complications, these tend to be relatively minor, and patients who undergo CRP exhibit lower rates of local complications than patients who fail to undergo surgical treatment.36,49 CRP can readily alleviate dysuria, ureteral obstruction, and urinary retention, in addition to improving symptoms of bone pain in advanced PCa patients, leading to better quality of life outcomes.38,49,51 A prospective analysis of patients who underwent CRP did not reveal any evidence of complications associated with local progression, with roughly 33% of the patients treated with ADT alone exhibiting symptoms such as lower urinary tract obstruction, hematuria, bladder coagulation, or anemia. While surgical intervention can effectively alleviate these symptoms, it is often associated with a higher risk of adverse outcomes such as urinary incontinence, urinary retention, and clot retention. 36 These findings demonstrate the value of CRP for the prevention of local complications.

Steuber et al 49 analyzed prospective data and found that CRP was potentially beneficial, reducing local complication rates in oligometastatic PCa patients, as local complications arose in just 7% of patients in the CRP group relative to 35% of patients in the BST (best standard treatment) group (P < 0.01). In a separate prospective analysis, CRP and pelvic lymph node dissection in oligometastatic PCa patients decreased local symptom rates from 55.2% for patients who underwent systemic treatment to 29.4% in surgically treated patients (P = 0.014). 51 These results align well with retrospective data published by Won et al, who found that CRP effectively improved local complication incidence compared to patients who did not undergo local surgical treatment (20% vs 54.3% P < 0.001). 36 In their prospective study, Simforoosh et al observed the absence of urinary dysfunction in 84.6% of mPCa patients undergoing CRP treatment compared to 39.1% of control patients undergoing systemic therapy owing to differences in local control and disease progression. 38 CRP also exhibited better local control efficacy than radiotherapy, with 1 multicenter prospective study revealing a 92% local symptom-free survival rate in the CRP group compared to rates of 77% and 60% in patients that underwent radiotherapy and no local treatment, respectively. 52 One phase I clinical trial revealed that CRP was associated with improved PCa patient survival but can also lead to urinary incontinence. Considering the high probability of urological severe complications in patients with mPCa, the acceptability of this risk was determined for most patients. 37

Simforoosh et al found that in addition to improving urinary complications, CRP was also associated with reductions in bone pain. Specifically, 14 patients (53.8%) reported significant improvements in bone pain after CRP compared to just 3 in the standard treatment group, while 11 patients (47.8%) experienced new or aggravated bone pain. 38

The management of localized concerns in prostate cancer requires attention, as a substantial proportion of patients experience issues related to local disease progression. 38 These issues encompass urinary retention, bilateral renal hydronephrosis, and elevated creatinine levels linked to the tumor. Research indicates that patients with local symptoms at diagnosis have shorter median survival than asymptomatic counterparts(47 months vs 86 months, P = 0.0007). 50 Moreover, the advancement of a disease results in a progressive decline in lower urinary tract symptoms, which in turn affects renal function and has the potential to induce abrupt renal failure. In cases when individuals experience significant lower urinary tract symptoms, it may be required to employ procedures such as permanent Foley catheters, bilateral renal pelvis diversion, and other therapeutic measures. These interventions aim to restore regular urine flow, mitigate potential consequences, and preserve renal function.38,49 The prominence of these local issues underscores the need for a proactive treatment approach throughout the disease trajectory. 50 Research consistently shows that local treatments can improve patient survival, irrespective of tumor metastasis, aligning with findings from Culp et al's study. 11

The findings of the research, as mentioned above, indicate that most newly diagnosed patients with metastatic prostate cancer initially present with localized symptoms that worsen as the disease advances. 50 CRP surgery is an effective treatment option for patients with oligometastatic prostate cancer, as it can alleviate symptoms such as urinary difficulties, ureteral obstruction, and urinary retention and improve bone pain symptoms in advanced prostate cancer patients, thereby improving the quality of life for patients. Patients who undergo CRP surgery experience fewer local complications than those who do not undergo surgical treatment.38,49,51 Despite perioperative complications associated with CRP surgery, such as urinary incontinence, urinary retention, and blood clot retention, most patients find these risks acceptable when weighing them against the potentially severe complications of untreated prostate cancer. Hence, patients should communicate comprehensively and discuss with their physicians when deciding on CRP surgery, carefully evaluating the benefits and risks associated with the procedure. Patients with oligometastatic prostate cancer require comprehensive treatment strategies incorporating local and systemic interventions. Therefore, physicians must consider the patient's medical state, individual features, and treatment objectives to achieve favorable clinical outcomes while devising treatment programs. Nevertheless, further investigation is necessary to augment the thorough assessment of CRP surgery in managing oligometastatic prostate cancer despite the evidence supporting its efficacy. The findings of this study will provide valuable insights for improving clinical practice and enhancing patient treatment outcomes.

Cytoreductive Prostatectomy Is Safe and Feasible

Cytopenic treatment of oligometastatic PCa generally centers around achieving local control via CRP and pelvic lymph node dissection. 53 CRP was historically thought to expose patients to unnecessary complication risks without facilitating disease control such that this procedure was not recommended.54,55 However, surgical and technological advances have improved the prognosis of high-risk PCa patients concerning treatment-related complications and disease control.56,57 CRP is a safe and feasible treatment option for oligometastatic PCa patients in several studies, and this procedure is reportedly associated with complication rates similar to those for locally advanced PCa. 36 CRP can improve patient outcomes without increasing the rate of postoperative severe complications.36,38,51 Recent evidence suggests that adding CRP to systemic treatment may potentially reduce the incidence of local complications. 49

Heidenreich et al determined that just 21.7% of oligometastatic PCa patients who underwent CRP experienced postoperative complications, with this rate being lower than that among patients in the control group following systemic treatment (57.7%), and surgery was not associated with any Clavien grade 4 or 5 complications, 36 confirming the feasibility and safety of this procedure.31,32 Another multicenter prospective analysis found that of 17 cN1M1 patients, 5 developed stress urinary incontinence following CRP, compared to 2 (6.9%) of 29 patients in the control group that underwent ADT alone. At 3 months postsurgery, 5 of the patients in the CRP group (29.4%) exhibited postoperative complications, including urinary tract infection, long-term lymphatic leakage, and femoral genitourinary neurasthenia, while 2 patients (11.8%) experienced secondary deep vein thrombosis. No additional significant complications were detected among patients with CRP, and the rates of complications observed were comparable to those in the ADT group. Specifically, 11 patients (37.9%) in the ADT group experienced urinary obstructions requiring therapeutic intervention, while 2 patients (6.8%) were diagnosed with ureteral obstruction accompanied by hydronephrosis. The urinary control recovery control rate in the CRP group 6 and 12 months after surgery was 73% and 90%, respectively. 51

Similarly, another prospective analysis observed no postoperative dysuria in 22 (84.6%) of patients who underwent CRP, whereas 9 (39.1%) individuals in the systemic treatment group ultimately needed surgical treatment due to local tumor progression. In that study, postoperative complications arose in just 4 patients in the CRP group; none were grade 4 or 5 complications. 38 This overall complication rate was deemed acceptable and in line with that reported by patients with locally advanced PCa undergoing RP at this same treatment center, in addition to being similar to rates reported in a retrospective analysis of RP outcomes for mPCa.32,58 Steuber et al demonstrated that CRP was associated with improvements in local complication incidence rates from 35% in mPCa patients that underwent systemic therapy to 7% after CRP that CRP could improve the incidence rate of local complications in mPCa patients from 35% of systemic treatment to 7% (P < 0.01), supporting the potential benefits of CRP. 49

The studies mentioned earlier provide evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of CRP as a potential therapy option. Surgical intervention for CRP has demonstrated the potential to enhance patient prognosis and minimize the possibility of postoperative complications. Numerous research studies have yielded empirical proof substantiating the viability and safety associated with CRP surgery.36,38,49,51 These studies show lower rates of postoperative complications, reduced incidence of urinary incontinence, and favorable recovery rates for urinary control. Moreover, CRP surgery has demonstrated potential benefits by significantly reducing local complications in patients with oligometastatic prostate cancer.

CRP surgery has shown notable safety and feasibility in treating oligometastatic prostate cancer. It improves local control and treatment outcomes while reducing the risk of postoperative complications. These research findings offer valuable insights for clinical practice and positively influence patient treatment outcomes.

In addition, the performance of orchiectomy immediately following CRP surgery during the same anesthetic session can potentially obviate the necessity for a further procedure, thereby mitigating patient risks. This intervention effectively decreases the overall size of the tumor by a singular surgical practice while also offering castration therapy as a means of reducing the financial stress experienced by patients. However, further study is necessary to evaluate cytoreductive treatment's efficiency and potential benefits in oligometastatic prostate cancer.

CRP Does Not Adversely Impact Patients’ Quality of Life

Published evidence suggests patients do not exhibit a notable decline in urinary control following CRP. Multiple studies indicate that in treating individuals with locally advanced prostate cancer, urinary incontinence and the rate of urinary control recovery are comparable between CRP and RP.34,36,51 Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that there is no apparent improvement in patients’ sexual and erectile function.32,59–61

In their analysis of 23 patients who underwent CRP, Heidenreich et al found that 21 (91.3%) required using 0–1 urine pads daily, while just 2 patients (8.7%) required 2–4 pads a day. 36 No differences in functional outcomes following CRP were observed compared to reported results following the RP treatment of high-risk PCa patients for the postoperative recovery of urinary control.62,63 In a prospective analysis of 46 patients, stress urinary incontinence was reported in 5 patients (29.4%) in the CRP group and urgent urinary incontinence in 2 patients (6.8%) in the control group, with an overall urinary control rate of 73% (± 11%) and 90% (± 9%) at 6 and 12 months following CRP. Urinary incontinence rates at 3 months post-CRP were the same as those in patients with local or locally advanced PCa, suggesting that CRP is not linked to adverse outcomes for urinary incontinence. 51 In a retrospective analysis of 113 patients who underwent CRP over 12 months, 68.1%, 17.7%, and 14.1%, respectively, reported no urinary incontinence, mild urinary incontinence (1-2 pads/day), and severe urinary incontinence (>2 pads/day). 34 Urinary incontinence outcomes following CRP are generally similar to those following RP when treating locally advanced PCa.64,65 A prospective analysis conducted by Simforoosh et al observed no urinary dysfunction in 22 (84.62%) male patients following CRP, with just 3 (11.54%) requiring pads owing to varying degrees of stress urinary incontinence. 38 In a retrospective analysis of quality of life outcomes in 411 patients, including 79 patients with oligometastatic osteopathy (M1) following CRP and 332 patients with PCa cancer and no metastatic osteopathy (M0) following RP, significantly lower erectile function scores (TTEF-5) were observed in M1 patients relative to M0 patients (8.5 vs 11.3, P = 0.022; 1.3 vs 3.5, P < 0.001). No differences in ICIQ-SF scores, urinary incontinence rates, and number of pads used per day were observed between these groups. Before surgery, the ICIQ-SF scores for urinary incontinence in the M1 and M0 patient groups were 2.3 and 1.1, respectively, with scores rising to 6.4 after surgery. Throughout follow-up, urinary control recovered in 66% of M1 patients and 72% of M0 patients, with no significant difference in the timing of the recovery of urinary control between these groups (P = 0.773). Univariate and multivariate analyses also observed no significant differences in general quality of life or functional prognosis between these groups, suggesting that CRP represents a safe option for patients with oligometastatic disease who exhibit a quality of life below the standard level. 66 Several recent studies have reported satisfactory postoperative recovery of urinary control following CRP. For example, 1 phase I clinical trial published by Kim et al found that urinary pad use was not required in 48% of the 25 enrolled patients, while 8 of the 14 patients that did rely on pads required just 1 per day to prevent incontinence. When defining good recovery of urinary control by using 1 or fewer urinary pads per day, 80% of patients exhibited good recovery after CRP. 37 However, an analysis published by Kim et al reached the opposite conclusion, observing a significantly higher rate of urinary incontinence in the CRP group relative to the RP group (57.4% vs 90.8%, P < 0.0001). 67

Nevertheless, the study did not observe any significant improvement in sexual function and erectile performance among individuals who underwent CRP surgery. The results derived from the Kyrdalen trial indicate that patients, regardless of whether they received observation, standard systemic treatment, radiotherapy, or surgery, saw a decrease in erectile function during the follow-up period. Notably, a significant proportion of male individuals who underwent RP treatment experienced a considerable prevalence of erectile dysfunction, reaching as high as 89%. 59 An analysis of the experimental data reveals no significant correlation between poor erectile function and overall quality of life. Donovan's research arrived at a similar conclusion, underscoring that the adverse impact of RP on erectile function in prostate cancer patients is most pronounced at the 6-month mark, despite some partial recovery.

Furthermore, the long-term effects beyond 6 years are more unfavorable than other treatment groups. 60 CRP levels are significantly linked to a decline in self-reported male sexual function. Experimental findings illustrate that the average score on the Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM) decreased from 11.5 before surgery to 4.7 after surgery (P < 0.0018) in men. 61 This corresponds with the outcomes of Sooriakumaran's study, where most patients with anterior urethral cancer experienced erectile dysfunction at baseline. The median scores on the International Index of Erectile Function-5 (IIEF-5) for the control group were 18.5 (indicating mild erectile dysfunction), whereas the intervention group scored 13.0 (indicating mild to moderate erectile dysfunction). Notably, none of the patients exhibited a recovery in erectile function following surgery. 32

According to current research, CRP surgery has demonstrated the potential to improve urinary incontinence and urinary control recovery in patients diagnosed with oligometastatic prostate cancer. Research findings suggest that this surgical intervention may offer a safe and effective option, especially for patients with oligometastatic disease and below-standard quality of life. However, conflicting research findings may stem from factors including immature surgical techniques, variations in follow-up duration, different statistical methods, and other potential influencing factors. Consequently, additional large-scale and long-term follow-up studies are necessary to validate the existing research findings and provide a comprehensive evaluation of the advantages and limitations of CRP surgery concerning urinary incontinence and urinary control recovery. Furthermore, the study has also identified results in other domains, including erectile function scores and postoperative quality of life, which have significant implications for CRP surgery's overall effectiveness and patients’ quality of life. However, further research is still required to investigate the relationships between these results and factors, such as surgical types and postoperative recovery, and ascertain CRP surgery's long-term effects in these areas. Thus, additional research is necessary to thoroughly assess the safety and efficacy of CRP surgery and generate more substantial evidence for clinical practice. The findings of these studies will contribute to an enhanced comprehension and utilization of CRP surgery among researchers and clinicians, ultimately resulting in advancements in patients’ quality of life and functional recovery.

Indications for Cytoreductive Prostatectomy

Current clinical guidelines do not recommend CRP as a first-line treatment option for individuals diagnosed with oligometastatic PCa, instead suggesting that prostate radiotherapy be considered in individuals with a low oligometastatic load characterized by fewer than 4 systemic bone metastases and no extraspinal, extrapelvic, or visceral metastases. The value of CRP as a local treatment has thus remained controversial, emphasizing a need for further RCTs focused on this interventional approach using strict inclusion criteria. 14 As the above results emphasize, CRP can contribute to good survival outcomes in appropriate patient populations36,37 but may not achieve the desired effects when applied in patients who fail to meet screening criteria while exposing these individuals to an unnecessary risk of complications. 38

Prospective studies have employed variable screening criteria (Table 1). Heidenreich et al conducted a case-control study comparing ADT alone to ADT + CRP for a group of highly selected patients. These patients tended to respond well to a 6-month neoadjuvant ADT course, with PSA levels falling to under 1.0 ng/mL. These patients did not exhibit visceral or retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis and had 3 or fewer bone metastases. Throughout follow-up, individuals in the CRP group demonstrated prolonged clinical PFS (38.6 vs 26.5 months, P = 0.032) and lower local complication rates. 36 Patients in the interventional group showed favorable characteristics, including lower ages, PSA levels, ALP levels, and tumor metastasis burden. CRP can considerably benefit their survival and quality of life when patients are carefully selected and indicate a low overall load with few metastases. Kim et al performed studies of individuals with histologically confirmed prostate adenocarcinoma patients with MRI, bone scan, or biopsy evidence of lymph node or bone metastases (N1Mx or NxM1a/b). These patients had a disease of clinical stage T3 or lower with no ureteral or rectal invasion as detected by MRI and an ECOG performance status of 0–1. Patients were excluded if they had clinical stage T4 or M1c disease, had undergone prior treatment for mPCa, or exhibited known spinal cord compression, deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism within the past 6 months. Follow-up analyses revealed that the 5-year survival rate of these males following CRP was 67%. 37

Table 1.

Screening Criteria for Included Studies

| Authors and year | Interventions | No. of patients | Ag (year) | Inclusion criteria | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heidenreich, A. 2015 36 | CRP | 23 | 61 (42-49) |

|

91.3% (3-y) |

| Ming-Xiong Sheng 2017 39 | CRP + ADT | 23 | 68.1 ± 9.9 |

|

Median OS 24 |

| Tian Lan 2019 41 | CRP + ADT | 35 | 67.83 ± 7.19 |

|

88.6% (3-y) |

| Nasser Simforoosh 2019 38 | CRP | 26 | N/A |

|

76.9% (3-y) |

| Yaya Sow 2019 40 | CRP + ADT | 45 | 71.4 | Metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer | Median OS 24 |

| Isaac Yi Kim 2022 37 | CRP | 32 | 64.5 (57.5-70) |

|

69% (5-y) |

Another retrospective study produced comparable results. In a meticulously selected cohort of patients with oligometastatic prostate cancer who met the following criteria, namely, (1) confirmed diagnosis of prostate cancer through transperineal prostate needle biopsy under transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) guidance, (2) radionuclide bone scan confirmation of bone metastasis, (3) no evidence of visceral metastasis, (4) clinical stage ≤cT3a, (5) prostate volume ≤50 ml, and (6) prostate-specific antigen (PSA) decreasing to ≤1.0 ng/ml within 6 months of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), CRP surgery demonstrated a significant extension in patients’ 5-year survival rate, progression-free survival (PFS), and castration resistance time. 45 Simforoosh et al conducted a study enrolling 49 eligible PCa patients with the following criteria: (1) individuals with newly diagnosed oligometastatic PCa accompanied by increased PSA levels, lymph node metastasis, and extensive bone metastasis; (2) imaging results and digital rectal examination results indicating that the complete PCa removal was a possibility; (3) no visceral metastasis; (4) no apparent complications; (5) age <75 years; and (6) no history of prior radiotherapy treatment. Follow-up results revealed that patients in the CRP group exhibited a significantly lower biochemical recurrence rate relative to the control group (34.6% vs73.9, P = 0.01), with whole bone scans also indicating a significant decrease in the metastatic volume in the CRP group (P = 0.003). Higher mortality rates were observed in the CRP group (23%) compared to similar studies owing to differences in the utilized inclusion criteria. 38

The retrospective analysis performed by Lan et al suggested that the indications of CRP should not be limited to oligometastatic disease and should instead be based on particular prognostic factors and risk stratification models. 47 Favorable prognostic indicators for tumor progression include histopathological classification, 59 serum tumor markers, 60 TNM staging, and tumor metastasis.

RNA-sequencing results from some analyses and advances in molecular imaging techniques offer new opportunities to better screen for suitable candidates for CRP.35,59,60 For example, RNA-seq results published by Kim et al included data from patients undergoing CRP that were separated into 3 groups based on their clinical outcomes, with sequencing data demonstrating that TNF-α downregulation was closely associated with a good CRP response, potentially offering guidance that can enable the preselection of patients. 37

Typically, patients who respond well to CRP have the following characteristics: (1) limited bone metastases (<4 bone metastases) without metastases to the spine, pelvis, or viscera; (2) younger age (<75 years); (3) lower levels of PSA (<50 ng/mL); and (4) clinical stage T3 or lower. However, there is an ongoing debate regarding the recommendation of CRP as a treatment for oligometastatic prostate cancer. Previous research findings suggest potential survival and quality of life benefits among carefully selected patients who meet the specific criteria. Additional research and randomized controlled trials are needed to elucidate the effectiveness of CRP, establish optimal patient selection criteria, and compare it with alternative treatment modalities for clinical guidance. Subsequent studies could integrate RNA sequencing and molecular imaging techniques to refine patient selection criteria for CRP and identify individuals most likely to benefit from this therapeutic approach. Additionally, the determination of indications should rely on specific prognostic factors and risk stratification models rather than being solely confined to oligometastatic disease. Comprehensive utilization of histopathological classification, serum tumor markers, TNM staging, and tumor metastasis information can aid in evaluating patient suitability and prognosis.

In addition, current guidelines do not endorse cRP as the standard treatment for patients with oligometastatic prostate cancer. In clinical practice, physicians must meticulously select patients based on stringent screening criteria and provide a comprehensive overview of the advantages and disadvantages of surgery before proceeding. This entails a collaborative decision-making process with the patient to determine whether surgical treatment is appropriate. Physicians should duly apprise patients that cRP may enhance survival indicators, including overall survival rate, clinical progression-free survival rate, biochemical recurrence rate, and the likelihood of developing local complications. However, it is imperative to recognize that surgery may not be universally beneficial, as some patients may not experience improvements in their condition and may even deteriorate.

Moreover, cRP can give rise to perioperative complications such as urinary incontinence, urinary retention, and the formation of blood clots. Following surgery, patients may also face long-term complications, encompassing urinary tract infections, lymphatic leakage, deep vein thrombosis, and continued urinary incontinence, which can significantly impact their quality of life. Consequently, thorough communication and discussion with patients before surgery are paramount. Physicians must consider each patient's unique characteristics, the disease's progression, and the anticipated treatment goals to arrive at the optimal clinical decision.

Conclusion

For patients with oligometastatic prostate cancer, cytoreductive prostatectomy (CRP) in conjunction with lymph node dissection and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) has increased survival rates and extended overall survival. Compared to patients who receive ADT alone, patients who have CRP surgery routinely experience considerably higher overall survival, progression-free survival, and a decreased risk of disease progression. This has been shown in numerous prospective studies. Although the survival advantage of combining CRP surgery with ADT in patients with oligometastatic prostate cancer has been established, variations in research findings exist, possibly attributable to differences in patient selection criteria, treatment regimens, and follow-up durations. CRP surgery represents a safe and viable treatment option capable of enhancing patient prognosis and minimizing postoperative complications. However, additional research is still required to validate further the role of CRP surgery in managing oligometastatic prostate cancer. CRP surgery has demonstrated the potential to enhance urinary continence and control recovery; however, conflicting research findings exist. Additional studies are necessary to validate its long-term effects and explore its association with other factors, including surgical types and postoperative recovery.

Further research should persist in investigating the effectiveness, indications, and optimal criteria for patient selection in CRP surgery while also comparing it with alternative treatment modalities to provide additional guidance for clinical practice. Integrating emerging technologies, including RNA sequencing and molecular imaging techniques, can enhance patient selection criteria for CRP and effectively identify individuals most likely to benefit from this therapeutic approach. The utilization of multiple prognostic indicators facilitates the assessment of patient suitability and prognosis, enabling the identification of the optimal treatment approach.

Abbreviations

- ADT

androgen deprivation therapy

- CRP

cytoreductive prostatectomy

- CSS

cancer-specific survival

- mPCA

metastatic prostate cancer

- OS

overall survival

- OPC

oligometastatic prostate cancer

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PSA

prostate-specific antigen

- RP

radical prostatectomy

- RT

radiation therapy.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Guangdong Medical Science and Technology Research Fund Project, High-Level Hospital Construction Research Project of Maoming People’s Hospital and Maoming Municipal Science and Technology Bureau Special Plan, and the Key Projects of Anhui Provincial Educational Department (grant numbers A2022464, 2020KJZX018, KJ2019A0373).

ORCID iDs: Yuan Tian https://orcid.org/0009-0003-5595-1794

Mingqiu Hu https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1040-5856

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022;72(1):7-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RLet al. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiong E, Murphy DG, Akaza H, et al. Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer in the Asia Pacific region: ‘real-world’ consideration of results from the Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference (APCCC) 2017. BJU Int. 2019;123(1):22-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Y, Mo M, Wei Yet al. et al. Epidemiology and genomics of prostate cancer in Asian men. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2021;18(5):282-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly SP, Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Cook MB. Past, current, and future incidence rates and burden of metastatic prostate cancer in the United States. Eur. Urol. Focus. 2018;4(1):121-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hellman S, Weichselbam RR. Oligometastases. J. Clin. Oncol. 1995;13(1):8-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weichselbaum R, Hellman S. Oligometastases revisited. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011;8(6):378-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tosoian JJ, Gorin MA, Ross AE, Pienta KJ, Tran PT, Schaeffer EM. Oligometastatic prostate cancer: Definitions, clinical outcomes, and treatment considerations. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2017;14(1):15-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen B, Ye S, Bai P. The efficacy of cytoreductive surgery for oligometastatic prostate cancer: A meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2021;19(1):160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowrance WT, Breau RH, Chou R, et al. Advanced prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline PART II. J. Urol. 2021;205(1):22-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culp SH, Schellhammer PF, William MB. Might men diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer benefit from definitive treatment of the primary tumor? A SEER-based study. Eur. Urol. 2014;65(6):1058-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gratzke C, Engel J, Stief CG. Role of radical prostatectomy in metastatic prostate cancer: Data from the Munich cancer registry. Eur. Urol. 2014;66(3):602-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohler JL, Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ, et al. Prostate cancer, version 2.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2019;17(5):479-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornford P, van den Bergh R, Briers E, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II-2020 update: Treatment of relapsing and metastatic prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2021;79(2):263-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Qin Z, Wang Yet al. et al. The role of radical prostatectomy for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biosci. Rep. 2018;38(1):BSR20171379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghadjar P, Briganti A, De Visschere PJ, et al. The oncologic role of local treatment in primary metastatic prostate cancer. World J. Urol. 2015;33(6):755-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preisser F, Chun FK, Banek Set al. et al. Management and treatment options for patients with de novo and recurrent hormone-sensitive oligometastatic prostate cancer. Prostate Int. 2021;9(3):113-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linxweiler J, Hajili T, Zeuschner Pet al. et al. Primary tumor resection decelerates disease progression in an orthotopic mouse model of metastatic prostate cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(3):737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shemshaki H, Al-Mamari SA, Geelani IA, et al. Cytoreductive radical prostatectomy versus systemic therapy and radiation therapy in metastatic prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Urologia. 2022;89(1):16-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mao Y, Hu M, Yang G, et al. Cytoreductive prostatectomy improves survival outcomes in patients with oligometas-tases: A systematic meta-analysis[J]. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20(1):255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Qin Z, Wang Y, et al. The role of radical prostatectomy for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Biosci Rep. 2018;38(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mickisch GH, Garin A, van Poppel H, de Prijck L, Sylvester R, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Genitourinary Group. Radical nephrectomy plus interferon-alfa-based immunotherapy compared with interferon alfa alone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: A randomized trial. Lancet. 2001;358(9286):966-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, Trimble EL, Montz FJ. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20(5):1248-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treasure T, Milosevic M, Fiorentine F, Macbeth F. Pulmonary metastasectomy: What is the practice and where is the evidence for effectiveness? Thorax. 2014;69(10):946-949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spel TL, Andersson B, Nilsson J, Andersson R. Prognostic models for outcome following liver resection for colorectal cancer metastases: A systematic review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2012;38(1):16-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim MY, Oskarsson T, Acharyya Set al. et al. Tumor self-seeding by circulating cancer cells. Cell. 2009;139(7):1315-1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Comen E, Norton L, Massague J. Clinical implications of cancer self-seeding. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011;8(6):369-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoyanova T, Cooper AR, Drake JM, et al. Prostate cancer originating in basal cells progresses to adenocarcinoma propagated by luminal-like cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110(50):20111-20116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Qin Z, Wang Yet al. et al. The role of radical prostatectomy for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biosci. Rep. 2018;38(1):BSR20171379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson IM, Tangen C, Basler J, Crawford ED. Impact of previous local treatment for prostate cancer on subsequent metastatic disease. J. Urol. 2002;168(3):1008-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jang WS, Kim MS, Jeong WSet al. et al. Does robot-assisted radical prostatectomy benefit patients with prostate cancer and bone oligometastases? BJU Int. 2018;121(2):225-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sooriakumaran P, Karnes J, Stief C, et al. A multi-institutional analysis of perioperative outcomes in 106 men who underwent radical prostatectomy for distant metastatic prostate cancer at presentation. Eur. Urol. 2016;69(5):788-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sooriakumaran P. Testing radical prostatectomy in men with prostate cancer and oligometastases to the bone: A randomized controlled feasibility trial. BJU Int. 2017;120(5B):E8-E20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidenreich A, Fossati N, Pfister Det al. Cytoreductive radical prostatectomy in men with prostate cancer and skeletal metastases. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2018;1(1):46-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rusthoven CG, Jones BL, Flaig TWet al. Improved survival with prostate radiation in addition to androgen deprivation therapy for men with newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34(24):2835-2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heidenreich A, Pfister D, Porres D. Cytoreductive radical prostatectomy in patients with prostate cancer and low volume skeletal metastases: Results of a feasibility and case-control study. J. Urol. 2015;193(3):832-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim IY, Mitrofanova A, Panja S, et al. Genomic analysis and long-term outcomes of a phase 1 clinical trial on cytoreductive radical prostatectomy. Prostate Int. 2022;10(2):75-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simforoosh N, Dadpour M, Mofid B. Cytoreductive, and palliative radical prostatectomy, extended lymphadenectomy and bilateral orchiectomy in advanced prostate cancer with oligo and widespread bone metastases: Result of feasibility, our initial experience. Urol. J. 2019;16(2):162-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Małkiewicz B, Kiełb P, Karwacki J, et al. Utility of Lymphadenectomy in Prostate Cancer: Where Do We Stand?[J]. J Clin Med. 2022;11(9):2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fossati N, Willemse PM, Van den Broeck T, et al. The benefits and Harms of different extents of lymph node dissection during radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer: A systematic review[J]. Eur Urol. 2017;72(1):84-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Deimling M, Rajwa P, Tilki D, et al. The current role of precision surgery in oligometastatic prostate cancer[J]. ESMO Open. 2022;7(6):100597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mazzone E, Preisser F, Nazzani S, et al. The effect of lymph node dissection in metastatic prostate cancer patients treated with radical prostatectomy: A contemporary analysis of survival and early postoperative outcomes[J]. Eur Urol Oncol. 2019;2(5):541-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pavlovich CP. Is pelvic lymph node dissection necessary during cytoreductive radical prostatectomy?[J]. Eur Urol Oncol. 2019;2(5):549-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhai T, Ma J, Liu Y, et al. The role of cytoreductive radical prostatectomy and lymph node dissection in bone-metastatic prostate cancer: A population-based study[J]. Cancer Med. 2023;12(16):16697-16706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheng MX, Wan LL, Liu CM, et al. Cytoreductive cryosurgery in patients with bone metastatic prostate cancer: A retrospective analysis[J]. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2017;33(12):609-615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sow Y, Sow O, Fall Bet al. et al. Impact of tumor cytoreduction in metastatic prostate cancer. Res. Rep. Urol. 2019;11:137-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lan T, Chen Y, Su Q, et al. Oncological outcome of cytoreductive radical prostatectomy in prostate cancer patients with bone oligometastases[J]. Urology. 2019;131:166-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Si S, Zheng B, Wang Z, et al. Does surgery benefit patients with oligometastatic or metastatic prostate cancer? - A retrospective cohort study and meta-analysis[J]. Prostate. 2021;81(11):736-744. 48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steuber T, Berg KD, Roder MA, et al. Does cytoreductive prostatectomy have an impact on prognosis in prostate cancer patients with low-volume bone metastasis? Results from a prospective case-control study. Eur. Urol. Focus. 2017;3(6):646-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patrikidou A, Brureau L, Casenave J, et al. Locoregional symptoms in patients with de novo metastatic prostate cancer: Morbidity, management, and disease outcome. Urol. Oncol. 2015;33(5):202-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poelaert F, Verbaeys C, Rappe Bet al. Cytoreductive prostatectomy for metastatic prostate cancer: First lessons learned from the multicentric prospective local treatment of metastatic prostate cancer (LoMP) trial. Urology. 2017;106:146-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trelles CR, Martinez-Pineiro LR. The role of cytoreductive radical prostatectomy in the treatment of newly diagnosed low-volume metastatic prostate cancer. Results from the local treatment of metastatic prostate cancer (LoMP) registry. Eur Urol. 2021;80(6):764-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reeves F, Costello AJ. Is there a place for cytoreduction in metastatic prostate cancer? BJU Int. 2016;118(1):14-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bayne CE, William SB, Cooperber MR, et al. Treatment of the primary tumor in metastatic prostate cancer: Current concepts and future perspectives. Eur. Urol. 2016;69(5):775-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stenzl A, Merseburger AS. Radical prostatectomy in advanced-stage and-grade disease: Cure, cytoreduction, or cosmetics? Eur. Urol. 2008;53(2):234-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacobs EF, Boris R, Masterson TA. Advances in robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy over time. Prostate Cancer. 2013; 2013:902686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turpen R, Atalah H, Su LM. Technical advances in robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2009;1(5):251-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yao XD, Liu XJ, Zhang SL, Dai B, Zhang HL, Ye DW. Perioperative complications of radical retropubic prostatectomy in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer: A comparison with clinically localized prostate cancer. Asian J. Androl. 2013;15(2):241-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kyrdalen AE, Dahl AA, Hernes E, et al. A national study of adverse effects and global quality of life among candidates for curative treatment for prostate cancer[J]. BJU Int. 2013;111(2):221-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA, et al. Patient-Reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer[J]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1425-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuh BE, Kwon YS, Shinder BM, et al. Results of phase 1 study on cytoreductive radical prostatectomy in men with newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer[J]. Prostate Int. 2019;7(3):102-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Steuber T, Budaus L, Walz J, et al. Radical prostatectomy improves progression-free and cancer-specific survival in men with lymph node-positive prostate cancer in the prostate-specific antigen era: A confirmatory study. BJU Int. 2011;107(11):1755-1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spahn M, Joniau S, Gontero P, et al. Outcome predictors of radical prostatectomy in patients with prostate-specific antigen greater than 20 ng/ml: A European multi-institutional study of 712 patients. Eur. Urol. 2010;58(1):1-7. 10–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suardi N, Moschini M, Gallina A, et al. The nerve-sparing approach during radical prostatectomy is strongly associated with the rate of postoperative urinary continence recovery. BJU Int. 2013;111(5):717-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Joniau SG,, Van Baelen AA, Hsu CY,, Van Poppel HP. Complications and functional results of surgery for locally advanced prostate cancer. Adv Urol. 2012;2012(2):706309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chaloupka M,, Stoermer L,, Apfelbeck Met al. Health-related quality of life following cytoreductive radical prostatectomy in patients with de-novo oligometastatic prostate cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(22):5636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim DK,, Parihar JS,, Kwon YS,, et al. Risk of complications and urinary incontinence following cytoreductive prostatectomy: A multi-institutional study. Asian J. Androl. 2018;20(1):9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]