Abstract

The lens is a transparent and ellipsoid organ in the anterior chamber of the eye that changes shape to finely focus light onto the retina to form a clear image. The bulk of this tissue comprises specialized, differentiated fiber cells that have a hexagonal cross section and extend from the anterior to the posterior poles of the lens. These long and skinny cells are tightly opposed to neighboring cells and have complex interdigitations along the length of the cell. The specialized interlocking structures are required for normal biomechanical properties of the lens and have been extensively described using electron microscopy techniques. This protocol demonstrates the first method to preserve and immunostain singular as well as bundles of mouse lens fiber cells to allow the detailed localization of proteins within these complexly shaped cells. The representative data show staining of the peripheral, differentiating, mature, and nuclear fiber cells across all regions of the lens. This method can potentially be used on fiber cells isolated from lenses of other species.

Introduction

The lens is a clear and ovoid tissue in the anterior chamber of the eye that is made up of two cell types, epithelial and fiber cells1 (Figure 1). There is a monolayer of epithelial cells that covers the anterior hemisphere of the lens. Fiber cells are differentiated from epithelial cells and make up the bulk of the lens. The highly specialized fiber cells undergo an elongation, differentiation, and maturation programming, marked by distinct changes in cell membrane morphology from the lens periphery to the lens center2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12, also known as the lens nucleus. The function of the lens to fine-focus light coming from various distances onto the retina depends on its biomechanical properties, including stiffness and elasticity13,14,15,16,17,18,19. The complex interdigitations of lens fibers have been hypothesized20,21 and recently shown to be important for lens stiffness22,23.

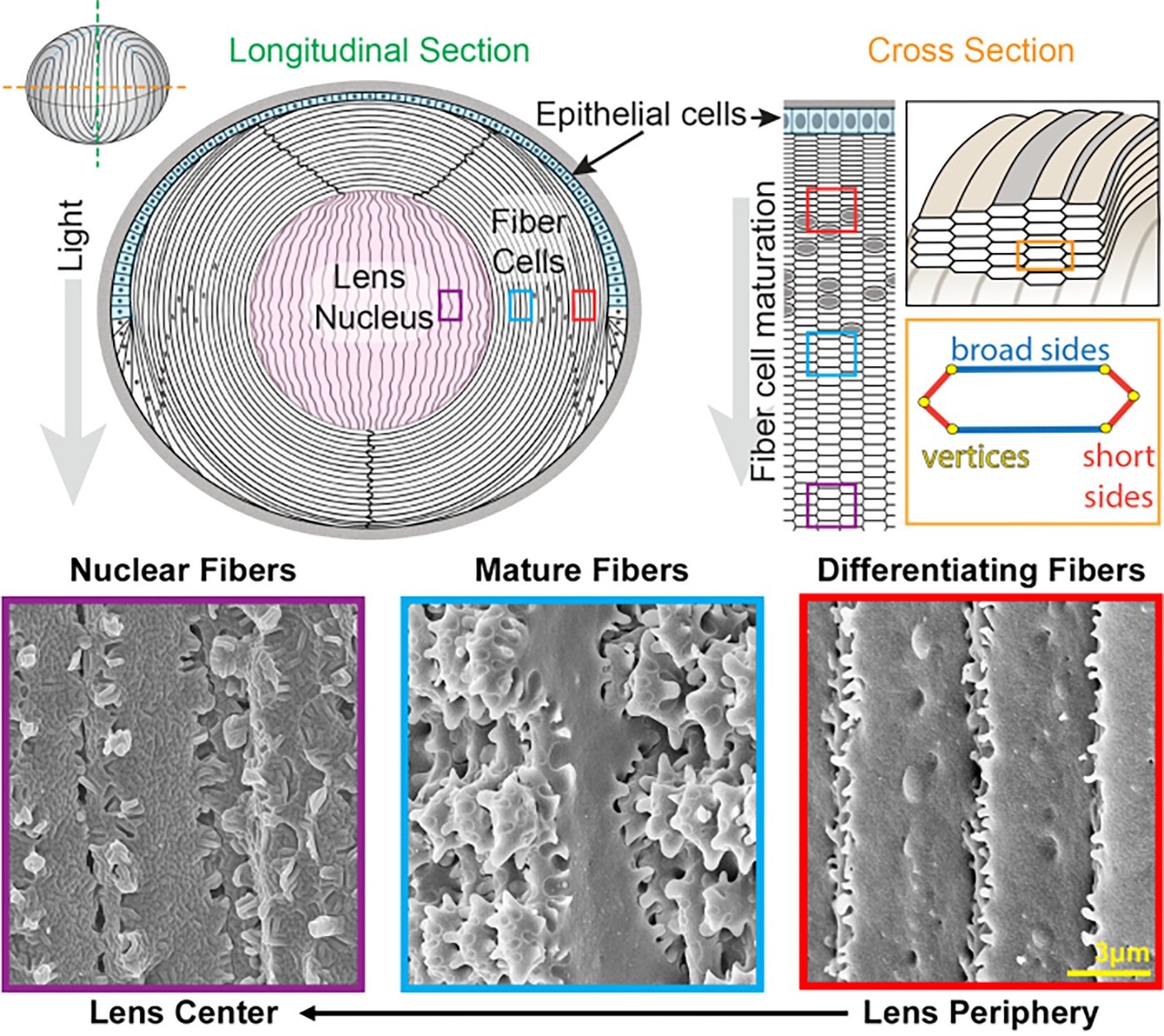

Figure 1: Lens anatomy diagrams and representative scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images from lens fibers.

The cartoon shows a longitudinal (anterior to posterior from top to bottom) view of the anterior monolayer of epithelial cells (shaded in light blue) and a bulk mass of lens fiber cells (white). The center of the lens (shaded in pink) is known as the nucleus and comprises highly compacted fiber cells. On the right, a cross-section cartoon reveals the elongated hexagon cell shape of lens fibers that are packed into a honeycomb pattern. Fiber cells have two broad sides and four short sides. Representative SEM images along the bottom show the complex membrane interdigitations between lens fiber cells at different depths of the lens. From the right, newly formed lens fibers at the lens periphery have small protrusions along the short sides and balls-and-sockets along the broad side (red boxes). During maturation, lens fibers develop large paddle domains that are decorated by small protrusions along the short sides (blue boxes). Mature fiber cells possess large paddle domains illustrated by small protrusions. These interlocking domains are important for lens biomechanical properties. Fiber cells in the lens nucleus have fewer small protrusions along their short sides and have complex tongue-and-groove interdigitations (purple boxes). The broad sides of the cell display a globular membrane morphology. The cartoon was modified from22,32 and not drawn to scale. Scale bar = 3 μm.

The lens grows by adding shells of new fiber cells overlaid on top of previous generations of fibers24,25. Fiber cells have an elongated, hexagonal cross section shape with two broad sides and four short sides. These cells extend from the anterior to the posterior pole of the lens, and depending on the species, the lens fibers can be several millimeters in length. To support the structure of these elongated and skinny cells, specialized interdigitations along the broad and short sides create interlocking structures to maintain the lens shape and biomechanical properties. Changes in cell membrane shape during fiber cell differentiation and maturation have been extensively documented by electron microscopy (EM) studies2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,20,26,27,28,29. Newly formed fiber cells have balls-and-sockets along their broad sides with very small protrusions along their short sides, while mature fibers have interlocking protrusions and paddles along their short sides. Nuclear fibers display tongue-and-groove interdigitations and globular membrane morphology. Little is known about the proteins that are required for these complex interlocking membranes. Previous studies on protein localization in fiber cells have relied on lens tissue sections, which do not allow clear visualization of the complex cell architecture.

This work has created and perfected a novel method to fix single and bundles of lens fiber cells to preserve the complex morphology and to allow immunostaining for proteins at the cell membrane and within the cytoplasm. This method faithfully preserves cell membrane architecture, comparable to data from EM studies, and allows staining with primary antibodies for specific proteins. We have previously immunostained cortical lens fibers undergoing differentiation and maturation22,23. In this protocol, there is also a new method to stain fiber cells from the lens nucleus. This protocol opens the door to understanding the mechanisms for formation and changes in membrane interdigitations during fiber cell maturation and lens nucleus compaction.

Protocol

Mice have been cared for based on an animal protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Indiana University Bloomington. The mice used to generate representative data were control (wild-type) animals in the C57BL6/J background, female, and 8–12 weeks old. Both male and female mice can be used for this experiment, since the sex of the mice is very unlikely to affect the experiment’s outcome.

1. Lens dissection and decapsulation

-

Euthanize mice following the National Institutes of Health’s “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” as well as animal use protocols approved by the institution.

NOTE: For the present study, mice were euthanized by CO2 overdose followed by cervical dislocation in accordance with an approved animal protocol (Indiana University).

Enucleate the eyes from the mice using curved forceps by depressing the tissue around the eyes with one side of the forceps to displace the eye out of the socket. Next, close the forceps underneath the eye and lift to remove the eye from the socket. Transfer the eyes to fresh 1x phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in a dissection tray.

Cut the optic nerve with ultra-fine scissors as close as possible to the eyeball. Carefully insert fine-tip, straight tweezers into the eyeball through the optic nerve’s exit at the posterior of the eye.

-

Carefully insert scissors at the same location as the tweezers in step 1.3 and begin cutting an incision from the posterior toward the corneal-scleral junction.

NOTE: Rodent lenses occupy ~30% of their eyes. Accidental damage will occur if the tweezers or scissors are inserted too deep into the eye.

Continue cutting along the corneal-scleral junction until at least half of the junction has been separated.

Use tweezers to gently push on the cornea so that the lens can exit through the incision made with steps 1.4 and 1.5.

Carefully remove any large pieces of tissue from the lens using fine-tip, straight tweezers. Inspect the lens to find the equatorial region.

Shallowly pierce the lens using fine-tip, straight tweezers, and then remove the lens capsule. The mass of lens fiber cells will remain intact, and the lens epithelial monolayer will remain attached to the lens capsule. Discard the lens capsule.

2. Lens single fiber cell staining

-

Transfer the lens fiber cell mass to a well plate with 500 μL of freshly made 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA; in 1x PBS) solution and incubate the samples at 4 °C overnight with gentle nutation (Figure 2A).

NOTE: The volumes for the solutions given are optimized for 48-well plates. If another size well-plate or tubes are used, adjust the volumes of the solutions accordingly. Fixation, blocking, and washing (1x PTX, 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1x PBS) solutions were made with 10x PBS and double distilled water (ddH2O) to a final concentration of 1x PBS.

-

Transfer the lens fiber cells to a 60 mm dish with 1% PFA. Use a sharp scalpel to split the ball of fiber cells in half along its anterior-posterior axis (Figure 2B). Cut the halves in half again along the same axis to produce quarters.

NOTE: The anterior-posterior axis is easily recognized by the direction of the fiber cells in the tissue mass.

-

Use straight tweezers to remove the nucleus region from the lens fiber cell quarters (Figure 2C).

NOTE: The lens nucleus region is rigid in rodent lenses, and the center of the lens will separate from the softer cortical fibers easily.

Post-fix the quarters of the lens cortex region in 200 μL of 1% PFA for 15 min at room temperature (RT) with gentle shaking (300 rpm on a plate shaker).

Wash the tissue quarters twice in 750 μL of 1x PBS for 5 min each with gentle shaking at RT.

-

Block the samples using 200 μL of blocking solution (5% serum, 0.3% Triton X-100, 1x PBS) for 1 h at RT with gentle shaking.

NOTE: For the representative data in this protocol, the samples were not stained with primary or secondary antibodies. After the blocking step, the samples were incubated with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA; 1:100) and phalloidin (1:100) (see Table of Materials) for 3 h at RT with gentle shaking and protection from light. Primary antibody staining has been demonstrated in previous publications22,23.

-

Incubate with 100 μL of primary antibody solution overnight at 4 °C with gentle shaking.

NOTE: The antibodies are diluted in blocking solution. Compared to slides with tissue sections, there are more cells in this type of preparation. Primary antibody concentrations should be increased to provide ample antibodies to stain more cells. Doubling the antibody concentration from what is used on tissue sections is recommended. The same applies to secondary antibodies.

Wash the tissue quarters three times with 1x PTX (0.1% Triton X-100, 1x PBS) for 5 min each at RT with gentle shaking.

-

Incubate the fiber cells with 100 μL of secondary antibody/dye solution for 3 h at RT with gentle shaking. Protect the samples from light during this and subsequent steps.

NOTE: WGA, phalloidin, and other fluorescent dyes can be added to the secondary antibody solution for simultaneous labeling of the cell membrane, cytoskeleton, or other organelles while also labeling the primary antibody.

Wash the fiber cells four times with 1x PTX for 5 min each at RT with gentle shaking.

Add one drop or 50 μL of mounting media onto a plus-charged microscope slide before transferring the tissue quarters to the slide.

Use tweezers to gently separate the fiber cells from each other and try to limit overlapping of the cell bundles.

-

Gently apply a #1.5 coverslip on top of the sample in mounting media. The mounting media should spread to the edge of the coverslip; if this does not occur, add some additional mounting media to the edge of the coverslip. Aspirate away any excess mounting media around the edge of the coverslip and use nail polish to seal the edges of the coverslip on the slide.

NOTE: Any type of mounting medium that is formulated for confocal microscopy can be used for these experiments.

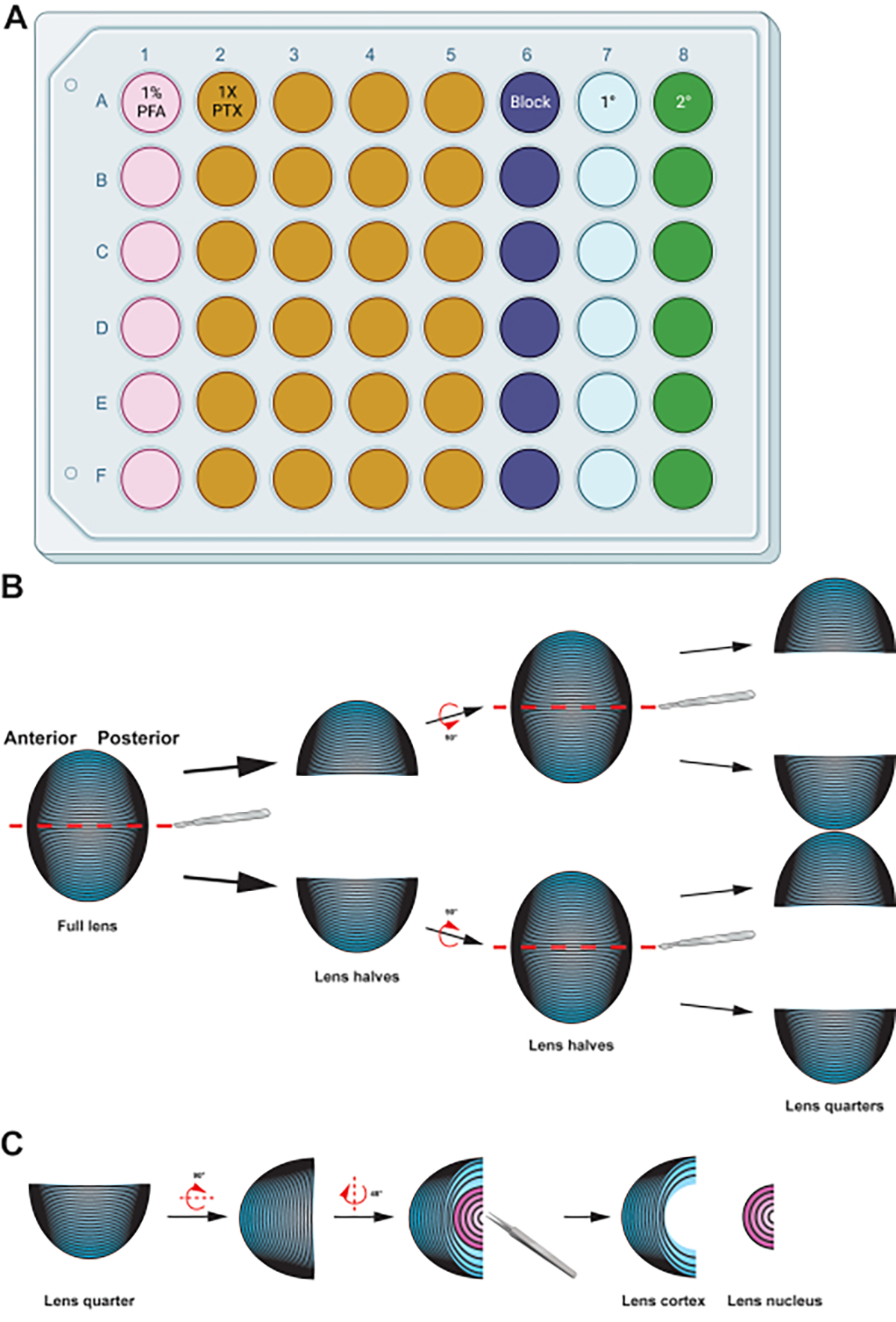

Figure 2: Graphical summary detailing the preparation and immunostaining of lens fiber cells.

(A) This 48-well plate has been color-coded by column to demonstrate a sample plate setup for the described methods, allowing easy transfer of samples between the various immunostaining steps by gentle handling using forceps. While the representative data for this protocol is not incubated with a primary antibody, the diagram includes a column for primary antibody incubation, and the wells for washing can be reused after removing used wash buffers by aspiration. (B) After fixation of the lens fiber cell mass, the tissue is split along the anterior-posterior axis (red dashed lines) to preserve the original structure of the cells. Once the tissue mass has been halved, the samples are rotated and the halves split into quarters along the anterior-posterior axis (red dashed lines). (C) Removing the lens nucleus region (in pink) is easily done using tweezers to dig out the dense central tissue from the cortical fiber cells (in blue). Cartoon diagrams were partially created using BioRender.com and not drawn to scale.

Materials.

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100% Triton X-100 | FisherScientific | BP151-500 | |

| 60mm plate | FisherScientific | FB0875713A | |

| 16% paraformaldehyde | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 15710 | |

| 10X phosphate buffered saline | ThermoFisher | 70011-044 | |

| 1X phosphate buffered saline | ThermoFisher | 14190136 | |

| 48-well plate | CytoOne | CC7672-7548 | |

| Cover slips (22 × 40 mm) | FisherScientific | 12-553-467 | |

| Curved tweezers | World Precision Instruments | 501981 | |

| Dissection microscope | Carl Zeiss | Stereo Discovery V8 | |

| Fine tip straight tweezers | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 72707-01 | |

| Fisherbrand Superfrost Plus Microscope Slides | FisherScientific | 12-550-15 | |

| LSM 800 confocal microscope with Airyscan (63X) and Zen 3.5 Software | Carl Zeiss | ||

| Nail polish | |||

| Normal donkey serum | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 017-000-121 | |

| Phalloidin (rhodamine) | ThermoFisher | R415 | |

| Primary antibody | |||

| Scalpel Feather Disposable, steril, No. 11 | VWR | 76241-186 | |

| Secondary antibody | |||

| Straight forceps | World Precision Instruments | 11252-40 | |

| Thermo Scientific Nunc MicroWell MiniTrays (dissection tray) | FisherScientific | 12-565-154 | |

| Ultra-fine scissors | World Precision Instruments | 501778 | |

| VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI | Vector Laboratories | H-1200 | |

| Wheat germ agglutinin (fluorescein) | Vector Laboratories | FL-1021-5 |

3. Lens nucleus single fiber cell staining

Complete the dissection outlined in section 1.

-

Mechanically remove the cortical fibers from the ball of the lens fiber cells, leaving the lens nucleus, by gently transferring the fiber cell mass to wet, gloved fingertips and gently rolling the tissue mass.

NOTE: In mouse lenses, rolling the ball of lens fiber cells between gloved fingertips is an effective method for removal of the cortical fiber cells from the hard lens nucleus28,30. For lenses where this mechanical method is not effective, careful dissection or a vortexing method29 may be used to remove the cortical fiber cells.

Transfer the lens nucleus to freshly made 1% PFA solution in a well-plate and incubate overnight at 4 °C with gentle shaking.

Transfer the sample to a 60 mm dish with 1% PFA and use a sharp scalpel to split the lens nucleus along the anterior-posterior axis. Halve the tissue samples again to produce nucleus quarters.

Follow the process outlined in steps 2.4–2.13 for immunostaining and sample mounting.

Representative Results

Lens fiber cells are prepared from the lens cortex (differentiating fibers and mature fibers) and the nucleus, and the cells are stained with phalloidin for F-actin and WGA for the cell membrane. A mixture of bundles of cells or single lens fibers (Figure 3) are observed and imaged. From the lens cortex, two types of cells (Figure 3A) are found. Differentiating fiber cells in the lens periphery are straight, with very small protrusions along their short sides. As the cell differentiates, the fiber cells become wavy with small interlocking protrusions. Further, along the maturation process, fiber cells develop large paddles decorated with small interlocking protrusions. The lens nucleus is highly compact and rigid in mouse lenses, and is isolated via mechanical removal of the softer lens cortex before fixation and staining of the nuclear lens fibers. From the lens nucleus, bundles of lens fibers are found that are smaller in diameter and have fine membrane structures that cannot be easily seen on a low-magnification image.

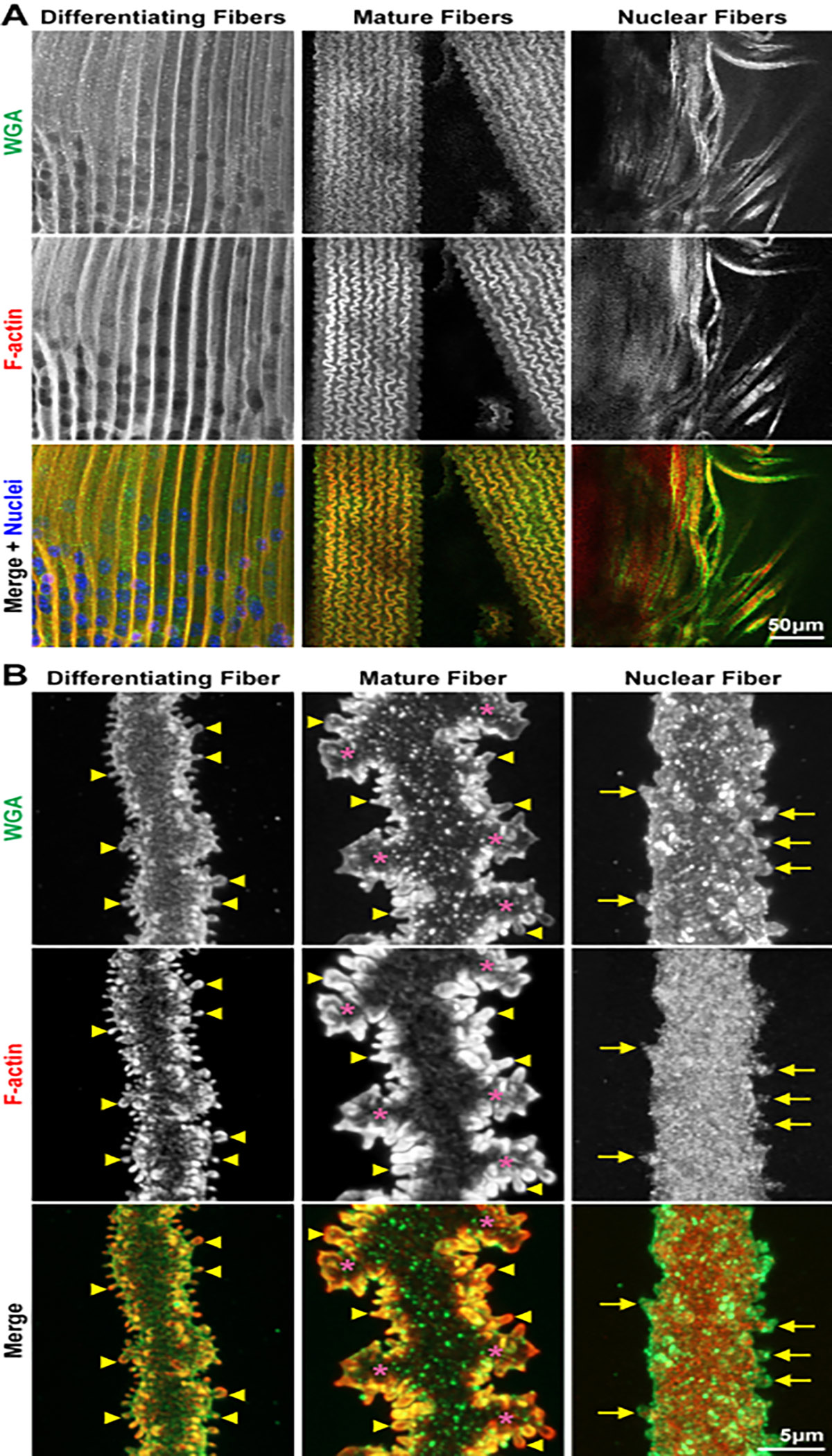

Figure 3: Confocal images of bundles (low-magnification) and single (high-magnification) images of fiber cells from different regions of the lens.

Cells are stained with WGA (cell membranes, green), phalloidin (F-actin, red), and DAPI (nuclei, blue). (A) In these preparations, bundles of lens fiber cells are often found from different regions. In the cortical preparations, there are differentiating and mature fiber cells. These different cells have distinct morphologies, allowing for easy identification. In the samples from the lens nucleus, fiber cell bundles as well as dissociated fibers are found. Scale bar = 50 μm. (B) Z-stacks through single differentiating, mature, and nuclear fiber cells are collected, and 3D rendering is used to reconstruct the images shown. The differentiating and mature fibers have many small protrusions along their short sides (the arrowheads mark select ones). These small protrusions are enriched for F-actin. The mature fiber also has large interlocking paddle domains (asterisks). The nuclear fibers have small membrane pockets and divots stained by WGA and retain a few protrusions along their short sides (arrows). Surprisingly, the F-actin network is now distributed in the cell cytoplasm without enriched signals at the cell membrane. The F-actin network does extend into small protrusions. Scale bar = 5 μm.

In high-magnification 3D reconstructions of lens fiber cells from different regions of the lens (Figure 3B), it is found that F-actin and WGA are highly colocalized at the cell membrane in differentiating and mature fiber cells. F-actin is enriched in the interlocking protrusions along the cell membrane in differentiating and mature fibers (Figure 3B, arrowheads). Mature fiber cells develop large interlocking paddles (Figure 3B, asterisks). The WGA staining is not completely colocalized with the F-actin signal, especially in the mature fiber cell, suggesting that the cortical actin network does not support all the smaller structures along the cell membrane. Unexpectedly, it is found that the F-actin network is within the cytoplasm of nuclear fiber cells. While the F-actin signal extends into the protrusions (Figure 3B, arrows) along the nuclear fiber cell membrane, the actin network is no longer enriched near the cell membrane or within the protrusions. The morphology of the nuclear fiber cell lacks paddles, in addition to a decrease in the organization and frequency of protrusions.

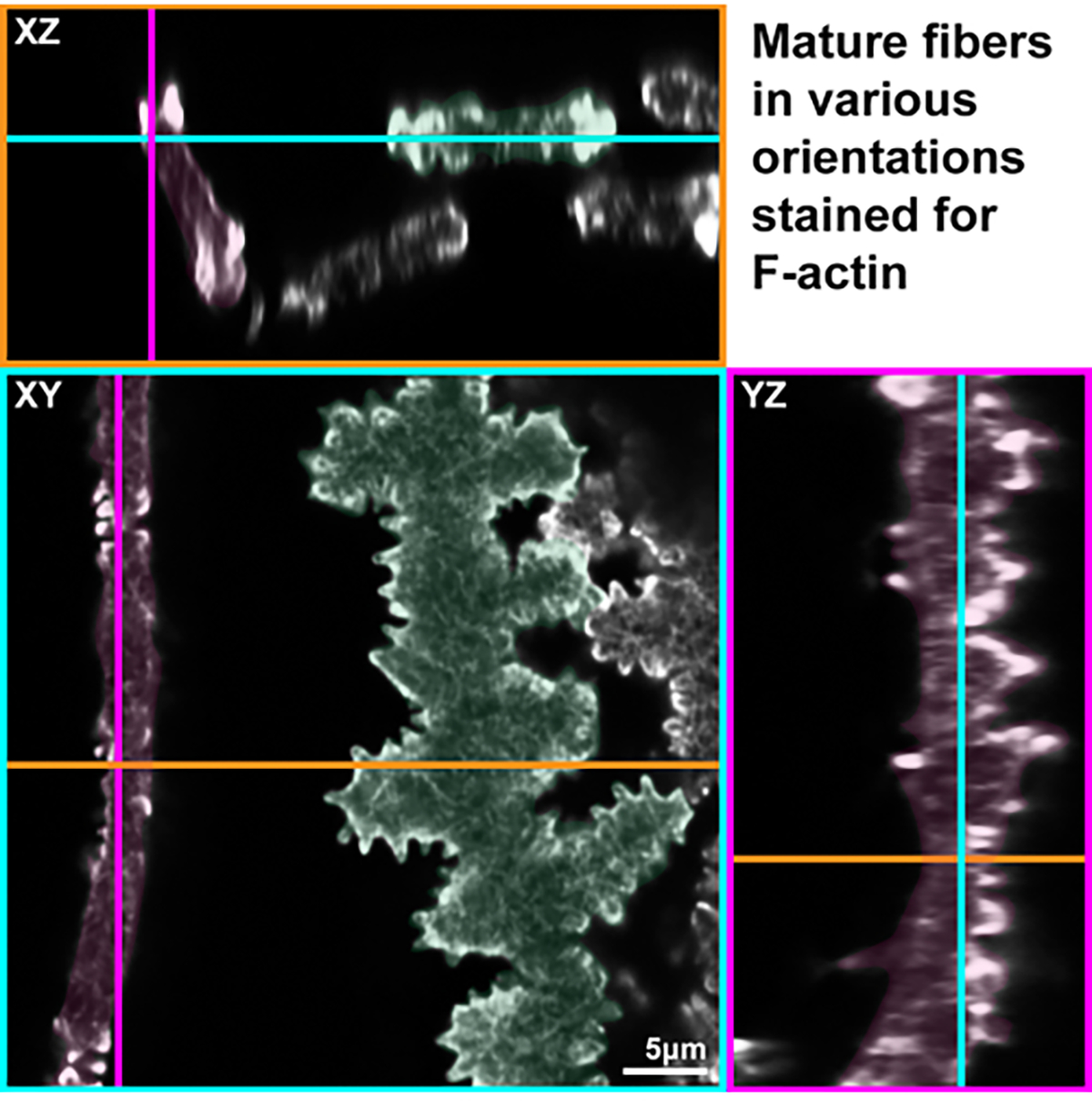

When the fiber cells are examined, it is important to note the orientation of the cells to avoid confusion about which type of cell is being observed. Z-stacks are collected through the cells, and then 3D reconstruction is used to look at the orthogonal 2D projections in the XY, XZ, and YZ planes. Due to the random orientation of cells in this preparation, it is possible to have cells that are not lying perfectly flat on the glass slide (Figure 4). All the cells in this representative image are mature lens fibers, but each cell has a drastically different appearance in the XY plane. The cell pseudo-colored in green is oriented broad side-up with visible paddles and protrusions, while the cell pseudo-colored in pink is lying with the short side up. This is more easily visualized in the XZ plane, showing the perpendicular orientations of the two cells shown in the XY plane. Examination of the YZ plane clearly shows the paddles of the mature fiber that is colored pink from the XY plane.

Figure 4: Orthogonal 2D projections (XY, XZ, and YZ planes) of 3D confocal z-stacks through a group of single mature lens fiber cells stained with phalloidin for F-actin.

Two cells are pseudo-colored in pink or green for identification on each plane. In the XY plane, the pink cell is lying with its short side facing up, while the green cell is lying flat with its broad side facing up. In the XZ plane, it is observed that the pink cell is tilted in orientation, while the green cell is parallel to the glass slide. In the YZ plane, the paddles and protrusions of the pink cells are observed, confirming that this cell is a mature fiber cell. Scale bar = 5 μm.

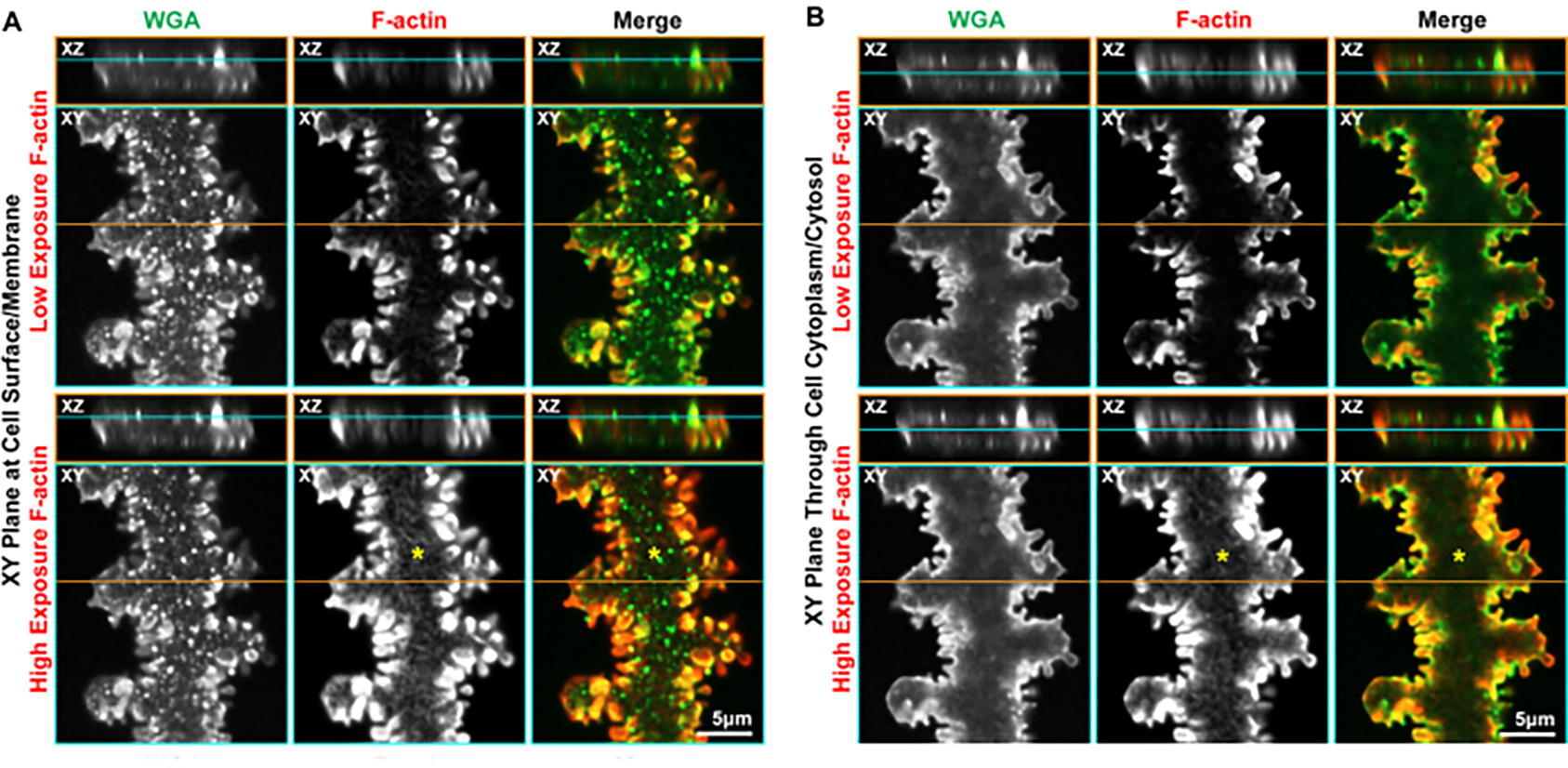

Since fibers are about 2–4 μm in thickness25,31, it is possible through the collection of z-stacks to view the cell surface or a plane through the cytoplasm (Figure 5). This works best on cells that are nearly parallel with the coverslip, with the broad side of the cell facing up. The cell surface in this mature fiber cell can be appreciated by observing the WGA signal (Figure 5A). The XZ plane clearly shows that this XY plane is along the broad side of the cell. Small WGA+ puncta along the membrane suggests a rough cell surface morphology. The small protrusions along the short side in low-exposure images show a greatly enriched F-actin signal. At higher exposure, where the F-actin signal in the protrusions is saturated, a fine reticulated F-actin network is observed across the cell membrane (asterisks). When an XY plane is considered through the cytoplasm of the mature fiber (Figure 5B), WGA staining is observed mainly along the cell membrane. Similar to what is seen at the cell surface, F-actin is enriched in the protrusions along the short sides, with a reticulated cytoplasmic F-actin network visible at higher exposure (asterisks). Our previous work has shown the staining for membrane proteins in XY planes through the cell cytoplasm22,23, but with this method, it is also possible to localize proteins along the broad side cell surface.

Figure 5: Orthogonal 2D projections (XY and XZ planes) of 3D confocal z-stacks through a single mature fiber cell stained with WGA (green) and phalloidin (F-actin, red).

(A) Projections from the cell surface along the broad side show WGA along the cell membrane, and the puncta of WGA suggest the membrane is not completely smooth. F-actin is enriched in the protrusions along the short sides, and a high-exposure image of the F-actin staining reveals a reticulated network along the cell membrane (asterisks). (B) Another plane through the cytoplasm of the same cell shows WGA along the cell membrane, framing the cell. F-actin forms a reticulated network through the cytoplasm (asterisks) and is greatly enriched in the protrusions along the cell membrane. Scale bars = 5 μm.

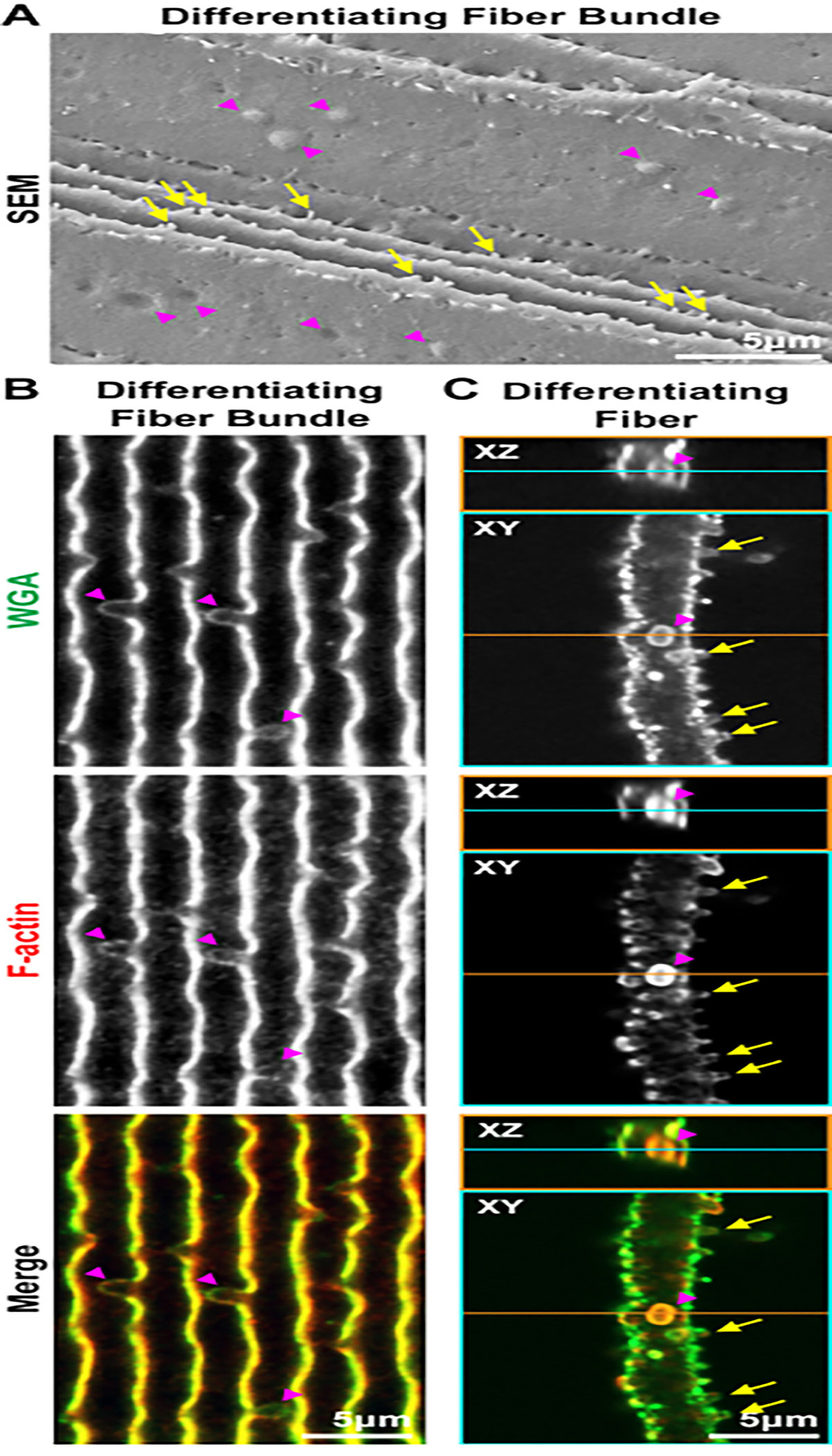

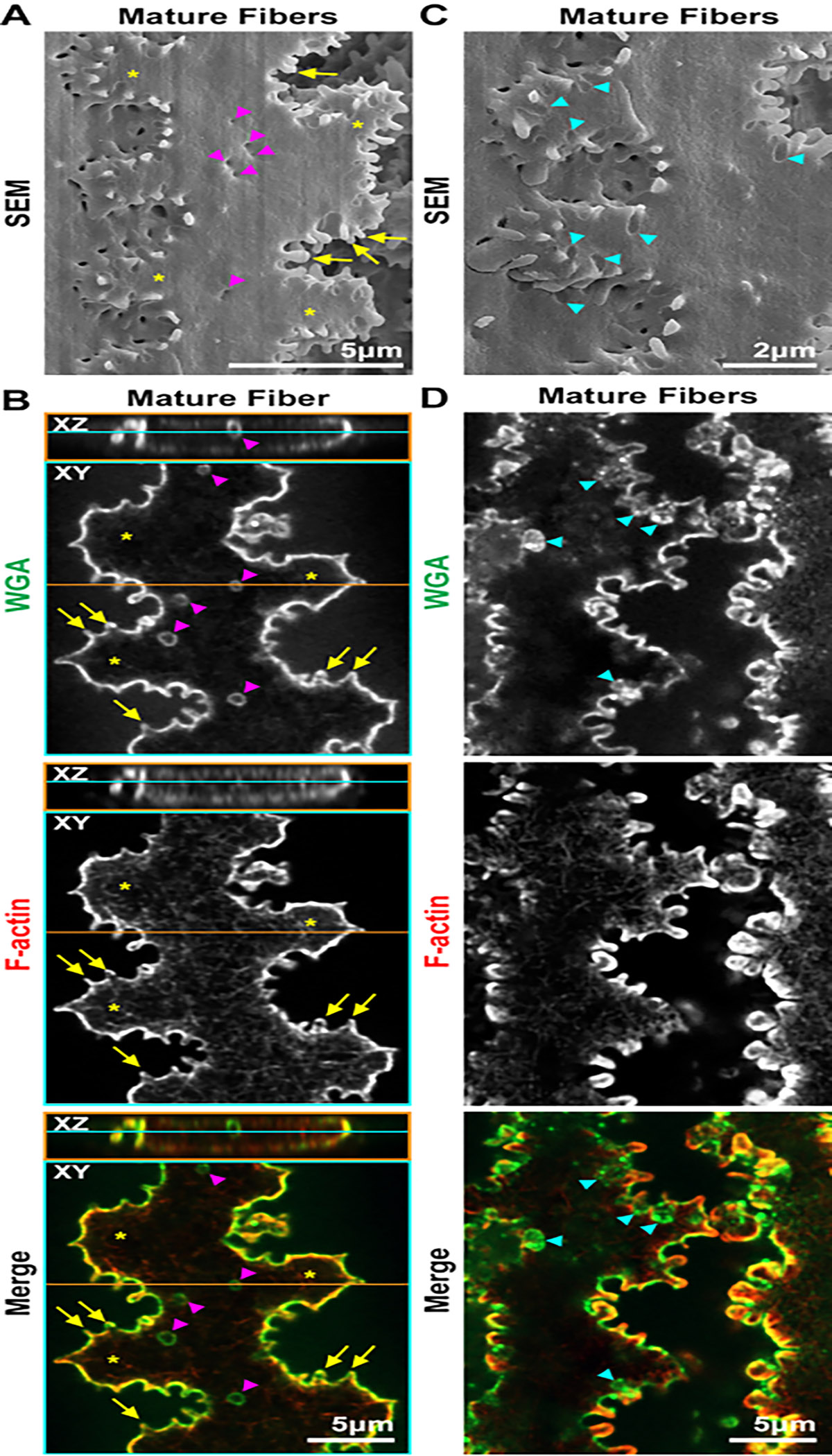

Next, images of lens fibers from the scanning EM (SEM) and staining experiments are compared. SEM experiments are performed as previously described29, and images are taken sequentially from the center of the sample to the periphery. First, differentiating lens fibers with small protrusions (Figure 6, arrows) along their short sides and a ball-and-socket (arrowheads) along their broad sides are examined. Similar to the SEM image (Figure 6A), in a bundle of differentiating fibers oriented along their short sides, the ball-and-socket interdigitations are large protrusions and grooves extending along the broad side of the cells (Figure 6B, arrowheads). A socket is found (Figure 6C, arrowheads) when the cell in the XY and XZ orthogonal 2D projections is viewed in single differentiating lens fibers. Small interlocking protrusions along the short sides are also faithfully preserved in these stained lens fiber cells compared to those in the SEM image (arrows). Next, the morphology of mature fiber cells is investigated (Figure 7). In the SEM image and the stained cell, there are small divots along the broad side of the cells (Figure 7A,B, arrowheads). Presumably, these are the remnants of the ball-and-socket interdigitations that are shrinking during the maturation process. The large paddles (asterisks) decorated by small interlocking protrusions (arrows) are comparable between the cells in SEM and the stained mature fiber. The cells in the SEM image also have obvious grooves where an interlocking protrusion is docking in the cell membrane (Figure 7C, arrowheads). These grooves can also be seen in these stained cells and are filled by the WGA signal (Figure 7D, arrowheads). The grooves can look like protrusions going inward toward the cell cytoplasm instead of projecting outward from the cell membrane, and often only WGA staining is visible in the grooves that have very little, if any, F-actin staining signal.

Figure 6: SEM and confocal microscope images of differentiating fiber cells from the lens cortex.

Fiber cells for confocal microscopy are stained with WGA (green) and phalloidin (F-actin, red). (A) SEM of a bundle of differentiating lens fibers shows ball-and-socket interdigitations (arrowheads) along the broad side of the cells with small interlocking protrusions (arrows) along the short sides of the cells. (B) Confocal images of a bundle of differentiating fibers imaged from the short sides show large ball-and-socket interdigitations along the broad sides of the cells (arrowheads). (C) Orthogonal 2D projections (XY and XZ planes) through a single differentiating lens fiber show a ball-and-socket interdigitation (arrowheads) along the broad side and small interlocking protrusions along the short side (arrows). Scale bars = 5 μm.

Figure 7: SEM and confocal microscope images of mature fiber cells from the lens cortex.

Fiber cells for confocal microscopy are stained with WGA (green) and phalloidin (F-actin, red). (A) The SEM image has two interlocking mature fibers with paddles (asterisks) decorated by small protrusions (arrows) along the short sides of the cells. There are also small indentations (arrowheads) along the broad side of the cell. These are possibly the shrinking remnants of ball-and-socket protrusions. Scale bar = 5 μm. (B) Orthogonal 2D projections (XY and XZ planes) through a single mature lens fiber have interlocking large paddles (asterisks) and small protrusions (arrows) along the short sides of the cells. Small WGA+ rings (arrowheads), similar to the indentations in the SEM image, are seen along the broad side of the cell. These WGA+ structures do not have F-actin staining. F-actin is mostly enriched at the cell membrane in the small protrusions and has a weak reticulated staining pattern in the cytoplasm. Scale bar = 5 μm. (C) SEM image of the mature fibers showing many grooves in the cell membrane (arrowheads), where protrusions from the neighboring cells rest and interlock. Scale bar = 2 μm. (D) A pair of mature fibers that are just separated showing grooves (arrowheads) stained by WGA. The grooves do not have enrichment of F-actin staining and look like protrusions extending inward toward the cytosol, rather than extending outward as an interlocking structure. Scale bar = 5 μm.

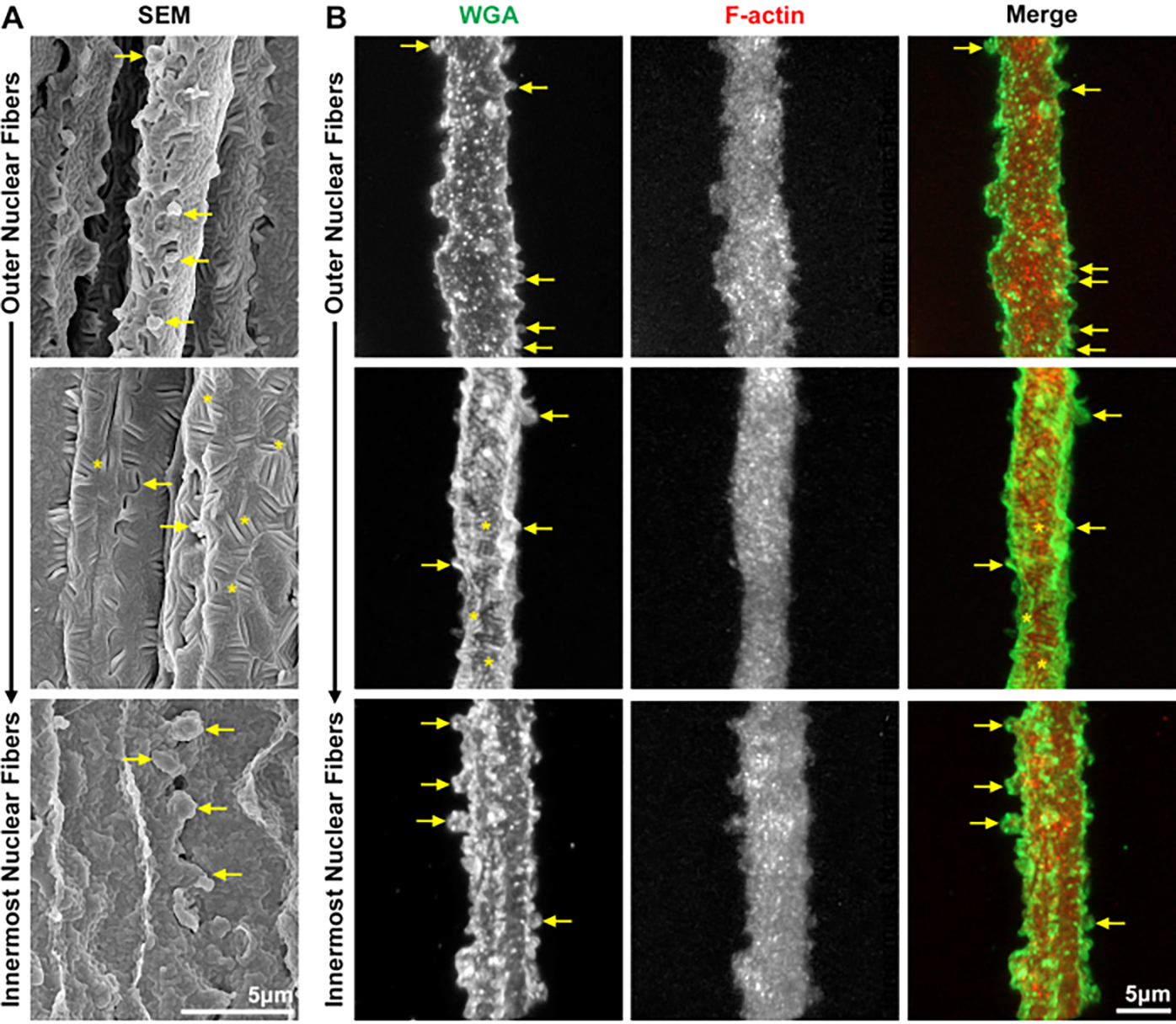

Finally, the stained nuclear lens fibers are compared with images from SEM preparations. This new method to fix and stain nuclear lens fibers faithfully preserve the morphology of nuclear lens fibers throughout different areas of the lens (Figure 8). Nuclear fiber cells have infrequent and larger interlocking protrusions along their short sides (arrows). The outermost nuclear lens fibers have a rough cell membrane texture, as seen in both SEM and the stained cell images. As the cells undergo further compaction toward the center of the nucleus, tongue-and-groove interdigitations appear along the cell membrane (asterisks), and the innermost nuclear fibers have a globular membrane morphology that can be appreciated on the SEM image and with WGA staining. F-actin is no longer enriched at the cell membrane, but forms a network filling the cytoplasm and extending weakly into the protrusions.

Figure 8: SEM and confocal microscope images of nuclear lens fiber cells.

Fiber cells for confocal microscopy are stained with WGA (green) and phalloidin (F-actin, red). (A) SEM images of nuclear fibers from the outermost layers toward the lens center reveal infrequent and larger interlocking protrusions on the short sides of the cells (arrows). The cell membrane is rough in these cells, with tongue-and-groove interdigitations (asterisks) and globular membrane morphology in the innermost cells. (B) 3D reconstructions of confocal z-stacks through single nuclear lens fibers have comparable features as the SEM images, including protrusions along the short sides (arrows), tongue-and-groove interdigitations (asterisks), and the rough membrane morphology that is apparent with WGA staining. F-actin forms a network that fills the cell cytoplasm and weakly extends into the protrusions. Scale bars = 5 μm.

Discussion

This protocol has demonstrated the fixation, preservation, and immunostaining methods that faithfully preserve the 3D membrane morphology of bundles or singular lens fiber cells from various depths in the lens. The stained lens fibers are compared with SEM preparations that have long been used to study lens fiber cell morphology. The results show comparable membrane structures between both preparations. EM remains the gold standard for studying cell morphology, but immunolabeling is more challenging in SEM samples for localizing proteins33,34,35 and requires an electron microscope to be imaged. This immunostaining method’s advantage is that multiple targets may be labeled at once, and images are collected on a confocal microscope.

While the method preserves the complex cell morphology, SEM is still required to compare interdigitations between control and altered lens fibers due to genetic mutation, aging, pharmaceutical treatments, etc. The immunostaining preparation creates a mixture of cells from the lens cortex or nucleus that are randomly distributed on the slide. Thus, if the morphology of the cells is altered, it may be more difficult to discern the depth at which cells were located in the lens before dissociation for staining. In these cases, it may be necessary to further dissect the lens into regions of interest after fixation and staining smaller bundles of lens fibers for higher spatial accuracy. The staining results should also be compared to SEM images to ensure the immunostained fibers preserve the morphology of the altered cells.

It has been shown for the first time that nuclear fiber cells can also be preserved for staining using this newly created method. It is important to remove the lens cortex before fixation of the nucleus because fixative penetration does not reach the lens nucleus when fixing the whole lens27. This protocol’s method to isolate the lens nucleus describes the mechanical removal of softer cortical lens fibers. This is possible in rodent lenses due to the very hard and compact lens nucleus28,30,36. In other species, the lens nucleus is softer and may require other methods to isolate those cells for staining. Previously, a vortexing method was used to remove cortical fiber cells from a knockout mouse line with a softer lens nucleus that could not be reliably isolated by mechanical removal29.

While we did not demonstrate primary antibody staining in these representative data, we have previously carried out the same type of staining with primary antibodies and appropriate secondary antibodies22,23. In our experience, many of the membrane proteins have a punctate signal, and thus the use of WGA or F-actin in cortical fibers or WGA in nuclear fibers is recommended to clearly delineate the cell membrane to better localize cell membrane proteins and recognize each stage of cell differentiation and maturation. The WGA or F-actin staining should be in a visible channel (red, green, or blue) to allow the observer to find the appropriate cells for imaging using the eyepiece easily. This type of membrane staining can also help identify any damage to the cells from the fixation, staining, and mounting process to exclude mechanically damaged cells. In this and previous works22,23, mechanically damaged cells are rarely observed.

This method requires patient and systematic examination of cells for imaging. The random mixture of cells can be quite daunting at first glance, but cells that are lying in the optimal orientation can usually be found. This method could be adapted for lens fibers isolated from other species. In larger lenses, it may be possible to use careful dissection to separate the different layers of cells before immunostaining. In summary, this study has created a robust and reliable method to preserve bundles of fibers or single fiber cells to study their complex morphology and localize proteins in 3D in these specialized cells. This unique protocol for nuclear fiber staining opens a new area of study into the less-well studied central fibers of the lens.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01 EY032056 (to CC) from the National Eye Institute. The authors thank Dr. Theresa Fassel and Kimberly Vanderpool at the Scripps Research Core Microscopy Facility for their assistance with the electron microscope images.

Footnotes

A complete version of this article that includes the video component is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.3791/65638.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Lovicu FJ, McAvoy JW Growth factor regulation of lens development. Developmental Biology. 280 (1), 1–14 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuszak J, Alcala J, Maisel H The surface morphology of embryonic and adult chick lens-fiber cells. The American Journal of Anatomy. 159 (4), 395–410 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuszak JR The ultrastructure of epithelial and fiber cells in the crystalline lens. International Review of Cytology. 163, 305–350 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuszak JR, Macsai MS, Rae JL Stereo scanning electron microscopy of the crystalline lens. Scanning Electron Microscopy. (Pt 3), 1415–1426 (1983). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo WK, Harding CV Square arrays and their role in ridge formation in human lens fibers. Journal of Ultrastructure Research. 86 (3), 228–245 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor VL et al. Morphology of the normal human lens. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 37 (7), 1396–1410 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vrensen GF Aging of the human eye lens-a morphological point of view. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part A, Physiology. 111 (4), 519–532 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vrensen GF, Duindam HJ Maturation of fiber membranes in the human eye lens. Ultrastructural and Raman microspectroscopic observations. Ophthalmic Research. 27 Suppl 1, 78–85 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willekens B, Vrensen G The three-dimensional organization of lens fibers in the rabbit. A scanning electron microscopic reinvestigation. Albrecht von Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Opthalmology. 216 (4), 275–289 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willekens B, Vrensen G The three-dimensional organization of lens fibers in the rhesus monkey. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 219. (3), 112–120 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou CJ, Lo WK Association of clathrin, AP-2 adaptor and actin cytoskeleton with developing interlocking membrane domains of lens fibre cells. Experimental Eye Research. 77 (4), 423–432 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuwabara T The maturation of the lens cell: a morphologic study. Experimental Eye Research. 20 (5), 427–443 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weeber HA, Eckert G, Pechhold W, van der Heijde RG Stiffness gradient in the crystalline lens. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 245. (9), 1357–1366 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weeber HA et al. Dynamic mechanical properties of human lenses. Experimental Eye Research. 80 (3), 425–434 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weeber HA, van der Heijde RG On the relationship between lens stiffness and accommodative amplitude. Experimental Eye Research. 85 (5), 602–607 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heys KR, Cram SL, Truscott RJ Massive increase in the stiffness of the human lens nucleus with age: the basis for presbyopia? Molecular Vision. 10, 956–963 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heys KR, Friedrich MG, Truscott RJ Presbyopia and heat: changes associated with aging of the human lens suggest a functional role for the small heat shock protein, alpha-crystallin, in maintaining lens flexibility. Aging Cell. 6 (6), 807–815 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glasser A, Campbell MC Biometric, optical and physical changes in the isolated human crystalline lens with age in relation to presbyopia. Vision Research. 39 (11), 1991–2015 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierscionek BK Age-related response of human lenses to stretching forces. Experimental Eye Research. 60 (3), 325–332 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biswas SK, Lee JE, Brako L, Jiang JX, Lo WK Gap junctions are selectively associated with interlocking ball-and-sockets but not protrusions in the lens. Molecular Vision. 16, 2328–2341 (2010). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lo WK et al. Aquaporin-0 targets interlocking domains to control the integrity and transparency of the eye lens. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 55 (3), 1202–1212 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng C et al. Tropomyosin 3.5 protects the F-actin networks required for tissue biomechanical properties. Journal of Cell Science. 131 (23), jcs222042 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng C et al. Tropomodulin 1 regulation of actin is required for the formation of large paddle protrusions between mature lens fiber cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 57 (10), 4084–4099 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuszak JR The development of lens sutures. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 14 (2), 567–591 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bassnett S, Costello MJ The cause and consequence of fiber cell compaction in the vertebrate lens. Experimental Eye Research. 156, 50–57 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biswas S, Son A, Yu Q, Zhou R, Lo WK Breakdown of interlocking domains may contribute to formation of membranous globules and lens opacity in ephrin-A5(−/−) mice. Experimental Eye Research. 145, 130–139 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blankenship T, Bradshaw L, Shibata B, Fitzgerald P Structural specializations emerging late in mouse lens fiber cell differentiation. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 48 (7), 3269–3276 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng C et al. Age-related changes in eye lens biomechanics, morphology, refractive index and transparency. Aging. 11 (24), 12497–12531 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng C et al. EphA2 affects development of the eye lens nucleus and the gradient of refractive index. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 63 (1), 2 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng C, Gokhin DS, Nowak RB, Fowler VM Sequential application of glass coverslips to assess the compressive stiffness of the mouse lens: strain and morphometric analyses. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (111), 53986 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forrester JV, Dick AD, McMenamin PG, Roberts F, Pearlman E Anatomy of the eye and orbit. in The Eye (Fourth Edition). W. B. Saunders. 1–102.e2 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng C, Nowak RB, Fowler VM The lens actin filament cytoskeleton: Diverse structures for complex functions. Experimental Eye Research. 156, 58–71 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg MW, Fiserova J Immunogold labeling for scanning electron microscopy. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1474, 309–325 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg MW High-resolution scanning electron microscopy and immuno-gold labeling of the nuclear lamina and nuclear pore complex. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1411, 441–459 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermann R, Walther P, Muller M Immunogold labeling in scanning electron microscopy. Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 106 (1), 31–39 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gokhin DS et al. Tmod1 and CP49 synergize to control the fiber cell geometry, transparency, and mechanical stiffness of the mouse lens. PLoS One. 7 (11), e48734 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]