Abstract

Older people can experience health and social challenges such as loneliness, depression, and lack of social connectedness. One initiative that has been trialed to address these challenges is reminiscence programs. These programs can include music, art, photographs, sports, and general discussion to stimulate memories. This review aimed to systematically search for literature that explored the impact and experience of reminiscence programs for older people living in the community for the purposes of informing community programming. The PICOS framework was used to develop the review parameters and search strategy. Qualitative and quantitative research focused on community-based reminiscence programs were included. Commercially produced databases and grey literature were searched. The Critical Appraisal Skills Program qualitative critical appraisal tool and McMaster quantitative critical appraisal tool were used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. Quantitative data were descriptively synthesized, and qualitative data were thematically analyzed, with each reported separately. Twenty-seven studies were included in the review. All quantitative studies (n = 17) provided clear information regarding the purpose, sample size, and justification. The measures adopted were reliable and valid. All studies reported clear data collection/analysis information and statistically significant findings. All qualitative studies (n = 10) clearly articulated a purpose with nine clearly describing recruitment, data collection, and researcher relationship. Synthesis of quantitative data demonstrated positive findings through a reduction in depression, anxiety, and loneliness and improvements in quality of life and mastery. These findings were supported and broadened by qualitative findings with three key themes identified: program processes, program ingredients, and program benefits. Providing opportunities for older adults to come together to tell stories about their past experiences may positively contribute to social outcomes. As reminiscence programs gain popularity, their implementation in practice should be underpinned by clear and reproducible practices.

Keywords: health, loneliness, depression, quality of life, relationships

Introduction

The population across the Western world is ageing.1 This demographic shift is changing the health and social care needs of communities, creating a need to address complex health and social issues, such as loneliness and decline in abilities.2 Being connected with others is purported as one potential way of helping older people with maintaining their mental and social health.3 Reminiscence can provide social connectedness and belonging as it gives an opportunity to express views and feelings.4 Reminiscence involves thinking about past experiences and sharing these memories with others.5 If conducted in a group setting reminiscence can bring people together and create friendships through story-telling and through shared past experiences.6

Through his Life Review work, Butler7 identified that older people who reminisce may have beneficial outcomes, including stronger relationships, which can reduce mental health issues such as depression. In addition, reminiscence programs can have a role in promoting self-worth and a sense of self through the process of looking back over their life.8 An initial exploration of literature about reminiscence programs indicated that programs were often designed for people living with dementia.9–11 Programs may be delivered in ways that are focused and structured, or more fluid and organic, and they may reminisce using topics and activities such as art, drama, music, and sports.12–16

Reminiscence research has focused on issues such as depression, anxiety, loneliness, and well-being as well as improving memory or cognition of older people.17,18 Reminiscence research has been conducted in both aged care and community settings.5,17 Although older people may reside in care homes for older people, a relatively large proportion reside at home1,19,20 and, as such most reminiscence programs are designed for community dwelling older people.5 Despite the apparent value of reminiscence programs and the growing body of research,21 to date there does not appear to have been a systematic review of community-based reminiscence programs. The aim of this systematic review was to explore participants' experiences of, and outcomes from, community-based reminiscence programs. The review question is: “What is the impact of, and experience from, community-based reminiscence programs for older adults?”

Methods

Protocol

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA framework.22 The protocol for this review was registered with Open Science Framework. The registration DOI is https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TGFD9

Eligibility Criteria

As the focus of the Systematic Review was to explore outcomes for and experiences of reminiscence program participants, both qualitative and quantitative research were included. As reminiscence is about remembering the past, programs designed to stimulate the recollection of those memories were considered. Only primary research was included, involving both individuals and groups, with programs using any topics or activities for reminiscence. Older people aged 50 years of age and over were the primary participants of interest. Exclusions included opinions, editorials, commentaries, and studies involving people under 49 years.15 Example outcomes of interest included social connections, loneliness, boredom and mood. Given the broad psycho-social focus of this review, studies that included reminiscence programs aimed at improving memory and retention were excluded because of their narrow focus.

Search Strategy

The PICOS framework was used to develop the review parameters and the search strategy (see Table 1). The following electronic databases were searched: OVID: MEDLINE, EMBASE, EMCARE; ProQuest, The Cochrane Library, SPORTDiscus, PsychInfo, Web of Science, Ageline. These databases were chosen as they contain much of the health literature and are inclusive of single and multi-disciplinary databases. As a means of avoiding publication and location bias, the review also included searching of grey literature, including an internet search engine (Google), Trove, ProQuest and relevant aged care, dementia care and health websites in some Western countries (Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, and United States of America). Reference lists from systematic reviews and included articles were also searched.

Table 1.

PICOS Framework

| Construct | Inclusion | Exclusion | Keywords/MESH | Limits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Adult participants | Children under 18 | Adults/ | English humans |

| Intervention | Community reminiscence programs | Age care facilities, clinical settings. | Reminis* OR memor* program* OR nostalgi* | English humans |

| Comparison | Nil | Nil | Nil | |

| Outcomes | Included but not limited to Psychosocial factors (ie depression, loneliness) | Cost effectiveness | ||

| Study Designs | Qualitative and quantitative | Opinions, editorials, commentaries |

Note: *Truncation allows for variations in word endings within search.

Study Screening

Following completion of the searches, citations were initially exported to Endnote TM (https://endnote.com/) and Covidence TM (https://www.covidence.org/au), for collating references and screening process. An initial screening of title and abstracts determined the most relevant studies which then advanced to full-text screening. All screenings were undertaken by RL, with CM, CA, RM and SK equally sharing the screening, with conflicts resolved through discussion among the group.

Quality Assessment

The Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) tools (https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/) were used to critically appraise the included qualitative studies. The CASP tools were chosen as these are widely used, freely available and include different critical appraisal tools for varying study designs, and the researchers have experience in using these tools. The CASP tools include a yes/no/cannot tell response, which enabled comparison between the included studies. For the quantitative studies, the McMaster critical appraisal tool was used.23 The McMaster critical appraisal tool was chosen because of its reliability to determine methodological quality and is widely used, freely available, and includes different critical appraisal tools for varying study designs. The researchers have experience in using these tools. The McMaster critical appraisal tools include a yes/no/n-a response, which enables comparison between the included studies. Each included study was independently appraised by two reviewers (RL, CM, CA, RM, SK), and results compared. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and if not possible, a third reviewer provided the final decision.

Data Extraction and Analysis

As the review question had two components “impact” and “experience”, this mixed methods systematic review adopted a convergent segregated data extraction and analysis approach.24 Data extraction was done systematically from each article, with quantitative and qualitative data compiled separately.24 Data extraction for all studies was completed by the first author with duplicate extraction shared among the other authors. Data were extracted about study characteristics included sample sizes; settings; population; description of programs; type of media used; methods of data collection; and results. Quantitative data were extracted according to outcome measures used and organized into findings of significance or otherwise. After extraction, quantitative data were examined, synthesized and summarized descriptively. Qualitative data were extracted that included information about experiences of reminiscence programs. These data were extracted into tables with each data section assigned a code. The tables were printed, and the research team met to manually sort the qualitative data into categories. Through a process of writing up the categories, data were further synthesized and reduced to descriptive themes.25

Results

Study Selection

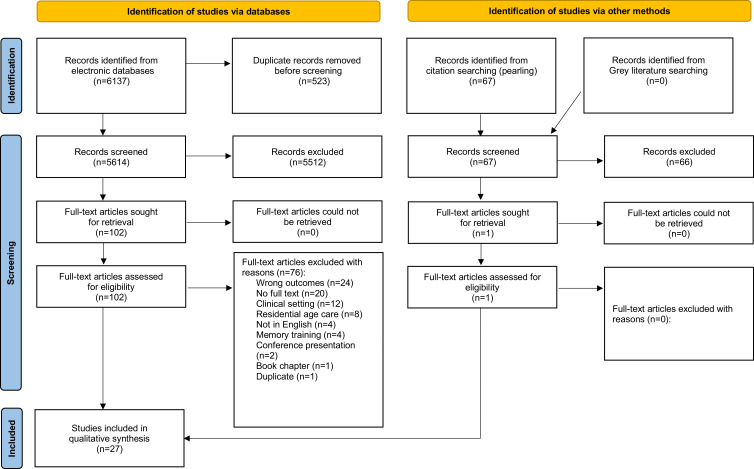

Searching of the literature yielded 6137 citations, and following the title and abstract screening there were 102 articles for full-text screening. Of these, twenty-six studies met the inclusion criteria. One additional study was identified during citation searching, which resulted in 27 included studies for this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. Adapted from Moher, D., Liberati, A, Tetzlaff, J, Altman DG & the PRISMA Group. Reprint—Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Physical Therapy. 2009;89(9): 873-880. Creative Commons.22

Study Characteristics

As reported in Table 2, 17 quantitative,13,26–41 and 10 qualitative6,8,14,42–48 studies were included in the review. In the quantitative studies, 12 studies used a randomized controlled design (n = 8)30–35,37,40 or quasi-experimental design (n = 4),13,29,36,39 as well as four,26,27,38,41 pre-post case studies and one28 controlled clinical trial. Four of the qualitative papers did not state their methodology,6,43,45,48 two used ethnography,44,46 one was participatory action research,42 one was qualitative descriptive,8 one was phenomenology,14 and one was qualitative realist.47 The methods of data collection used in the qualitative studies were participant observations (n = 5),8,44,46–48 interviews (n = 4),42,44,46,48 audio/recordings (n = 3),14,43,48 online posts,44 and yarning,45 while in one study had participants writing stories.6

Table 2.

Study Characteristics

| Author & Year | Country | Study Aim | Study Design | Method | Participants Details | Sample Size | Age Range | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al 201642 | USA | To describe the experience of RSVs | Community-based participatory research | Feedback meetings and individual interviews | RSVs who delivered the program | Feedback meeting = 45 interview = 6 | Not given | Not given |

| Anderson & Weber. 201543 | USA | To assess the feasibility and tolerability of a reminiscence program | N/S Qualitative. | Sessions were audio-recorded | Volunteers at retirement village | 19 | 80–99 | 10 w, 9 m |

| Bohlmeijer. 200926 | Ned | To explore the effects of a reminiscence on depressive symptoms | Case study pre-post | CES-D + PMS outcome measures | Volunteers with depressive symptoms | 108 (65 program; 43 control) | 55–87 Mean: 63.8 | Program: 48 w; 17 m; Control: 36 w 7 m |

| Chonody. 20136 | USA | To evaluate an intergenerational reminiscence program | N/S Qualitative | Stories, focus groups and responses on social media | Senior community centre | 26 (182 stories) 8 across 2 focus groups | 65–85 | 19 w, 7 men |

| Hanaoka. 201128 | Japan | Effects of odor stimulation in a group reminiscence program | Case study pre Post | GDS-15; LSI-K | Community-dwelling volunteers | 22 | Mean age: 76.8 | 17 w, 5 m |

| Hanaoka. 201827 | Japan | Effects of odor stimulation in a group reminiscence program | Controlled pre post clinical trial | GDS – 15. Five-cog Test | Community dwelling volunteers | 60 (27 program; 33 control) | Program (mean 78.4). control (mean 75.4) | Program: 22 w, 5 m; Control: 24 w, 9 m |

| Jo. 201529 | South Korea | Effects of reminiscence therapy on depression, quality of life, ego-integrity, social behaviour, and ADLs | Single pre-test post test | SF- GDS; LSI-A: EIS; SBFS; BI | PwD Registered to a mental health center. | 19 | 56–87 years | 14 w, 5 m |

| Kanayama. 200344 | Japan | To explore the online experience in virtual communities | Ethnography | Observation of messages and in-depth interviews | Anyone 65 or older | 13 interviews; 220 messages | 65-plus | Interviews = 6 w; 7 m |

| Korte. 201230 | Ned | To longitudinally investigate mediators of a life-review intervention on depression and anxiety | Randomized Controlled Trial | CES-D; HADS-A; RFS; MLQ; ATQ-P; PMS across 3 time points | Mild to moderate depressive symptoms and aged 55 + | 202 | 55–83 (mean 63) | 77% w, 23% m |

| Lukow. 201331 | USA | To examine if wellness was enhanced through the promotion of a sense of mattering to others | Randomized Controlled Trial using pre-post measures | 5F-WEL and Mattering Index | Residents of a retirement community | 19 (10 control and 9 intervention) | 76–95 (mean 83.26) | 15 w, 4 m |

| Osmond. 201845 | Aust | To explore the lived experiences and memories of Aboriginal women | Qualitative (Yarning sessions for oral history) | Two separate yarning sessions were observed | Members of Marching Girls groups (1950s and 1960s) | 14 | 60-plus | 14 w |

| Pearson. 200632 | USA | The efficacy integrative reminiscence on depression, acceptance of the past and mastery | Randomised controlled trial pre -post measures | GDS; APS and PMS | Community-dwelling elderly individuals | 36 (13 exp; 11 received CBT and 12 brochures) | 60–85 (mean 82) | 34 w, 2 m |

| Rawtaer. 201513 | Sing | To examine the impact of four psychosocial interventions on mental health | Pre post with repeated measures | GDS; GAI; MMSE; SDS; SAS at 4 time points over 1 year | Older people with depression and anxiety | 101 (29 music; 21 tai chi; 24 mindfulness and 27 art) | Mean 71 SD 5.95 (no range given) | 76 w, 25 m |

| Ren. 202133 | China | Effect of reminiscence therapy on spiritual wellbeing | Randomized controlled trial | SIWB; ULS; BRS | Community dwelling volunteers | Exp = 60; Ctl = 61 |

60-plus | Exp: 28 w, 32 m; Ctl: 31 w, 30 m |

| Sass. 202146 | UK | To determine what attending a reminiscence group meant to men living with dementia | Ethnography, | Participant observation; interviews | 12 PwD 9 without dementia 13 spouses 12 facilitators | 46 | 59-82 – m PwD; 60-82 – f spouse; 64-75 – other m | 20 w 26 m |

| Shellman. 20118 | USA | To explore perceived benefits and functions of reminiscence | Qualitative descriptive | Six focus groups and participant observations | Community-dwelling older African Americans | 52 | Over 60 (mean 72) | 90% w |

| Shellman. 200934 | USA | To evaluate the effects of integrative reminiscence on depressive symptoms | Randomised controlled trial | CES-D at 3 points | Community-dwelling older African Americans | 56 across intervention and 2 x controls | Over 60, mean age 72.6 | 43 w, 13 m |

| Sherman. 198735 | USA | To measure thoughts and feelings in the reconstruction of the past | Randomised controlled trial | Friends made and enjoyment LSI -Z; MSCM | Older people from 4 community settings | 104 | 60–91 Mean: 73.8 | 88 w, 15 m |

| Smiraglia. 201541 | USA | To examine mood changes from museum reminiscence program | Pre-test /post-test design with repeated measures | A short scale to measure 3 dimensions of mood | Older people from 12 retirement communities | 114 | 42–105. Mean: 83 | 74% w |

| Smiraglia. 201548 | USA | To explore how participants reacted to a museum reminiscence program | Qualitative | Recordings, interviews, observations | Older people from 12 retirement communities | 114 | 42–105 (mean 83) | 74% w |

| Somody. 201014 | USA | To explore the experiences of a reminiscence program | Phenomenology | Recordings of sessions | Community-dwelling older women | 6 | 74–86 | 6 w |

| Stevens-Ratchford. 199336 | USA | The effect of life review reminiscence on depression and self-esteem | Pre post with repeated measures | SES; BDI | Community dwelling older adults | 24 (12 exp; 12 ctl) | 69–91 mean 79.75 | 16 w, 8 m |

| Tolson-Schofield. 201147 | Scot | To evaluate the benefits of football-related reminiscence | Qualitative Realist evaluation. | Field notes | PwD | Participant numbers not given | Not given. | Men. |

| Woods. 201237 | UK | To evaluate quality of life and stress | RCT - measures at 3 time points | QoL- AD; EQ-5D | PwD and carers | 487 | PwD = 56 −93 (mean 77.5) | 242 w, 243 m (PwD) |

| Wu. 201738 | China | To understand the relationship between verbal response and emotional state | Pre-test/post-test design with repeated measures | GDS, SAS; RFS; CERQ | Women with depressive symptoms | 27 | 60–75 (mean 65.26 SD 4.32) | 27 w |

| Zauszniewski. 200439 | USA | To examine effect of program on negative emotions | Pre-test/ post-test | ESC, CES-D, SAS, HADS | Older people | 43 | 67–98 (mean 84) | 34 w, nine m |

| Zhou. 201140 | China | The effects of group RT on depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and affect | Randomised control trial | GDS; SES; ABS | Community depressive symptoms | 59 in exp group | 60+ mean = 69.75 (SD 6.56) | 34 w, 25 m |

Abbreviations: ABS, affect balance scale; ADLs, activities of daily living; APS, accepting the past scale; ATQ-P, automatic thoughts questionnaire positive; Aust, Australia; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BI, Bartel index BRS, brief resilience scale; CERQ, cognitive emotional regulation questionnaire; CES-D, Centre of Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale; CBT, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; CSRI, client services receipt inventory; Ctl, control; ESC, emotional symptom checklist; EQ-5D, European quality of life 5 dimensions; Exp, experimental; 5F-WEL, Five Factor Wellness Inventory; HADS-A, hospital anxiety and depression scale (A); GDS, geriatric depression scale; GAI, Geriatric Anxiety Inventory; GHQ, general health questionnaire; HADS, hospital anxiety depression scale; LSI-A, Life satisfaction index (A); LSI-K, life satisfaction index (K); LSI-Z, Life satisfaction index (Z); m, men; MLQ, Meaning in life questionnaire; MSCM, Monge Self Concept Measure; MMSE, Mini-mental state examination; Ned, Netherlands; PwD, people with dementia; PMS, Pearlin Mastery Scale (beliefs about control over environment); RT, reminiscence therapy; SAS, Zung self-rating anxiety scale; SDS, Zung self-rating depression scale; SD, standard deviation; SES, Rosenberg self-esteem scale; SIWB= Spirituality Index of Well-Being; SBFS, social behavior function scale; RFS, Reminiscence Function Scale; Scot, Scotland; Sing, Singapore; UK= United Kingdom; ULS – UCLA Loneliness Scale – 8; USA, United States of America; w, women.

Most studies were dated from between 2011 and 2021 with one study from 198735 and one from 1993.36 Two studies used a single reminiscence session,41,48 with all other studies accumulating results from multiple reminiscence sessions. Two authors had both a quantitative study34,41 and qualitative study included in the review.8,48 Thirteen studies were conducted in the USA,6,8,14,31,32,34–36,39,41–43,48 three in Japan27,28,44 and China,33,38,40 two in the Netherlands26,30 and United Kingdom37,46 and one each in South Korea,29 Australia,45 Singapore13 and Scotland.47

Reminiscence Program Characteristics

Across the 27 studies it was found that both structured and semi-structured reminiscence programs were used with details provided in Table 3. The use of the manualized life review technique was common (n = 13)8,14,26–28,30,32,34–36,38,39,42 with these programs being structured, discussion-based and outcomes-focused, while one program had a focus on mattering.31 Some of the other reminiscence programs were activity based with sensory and social elements. Activities included the use of slide/tape/photographs (n = 10);6,29,36,38,40,41,43,45,47,48 music/art/creativity (n = 6);13,14,29,37,40,42 physical activity (n = 4);13,33,37,46 socializing or making friends (n = 4);8,27,28,35 telling stories (n = 3);6,26,30 smelling objects (n = 2);27,28 writing/blogging (n = 2);6,44 visiting a museum and handling objects (n = 2);41,48 gardening (n = 1);29 discussion (n = 1);47 and yarning (n = 1).42 Areas of focus for reminiscence program included past sporting experiences,45–47 vintage automobiles43 and classic photography (old cameras).41,48

Table 3.

Reminiscence Program Characteristics

| Author | Program Content | Program Type | Program Aim | Location | Mode | Frequency | Who Delivered | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al 201642 | Reminiscence and creative activities | The manualized LIFE program | Social belonging, identity, and life review | Home visits | One volunteer with one palliative care pt and caregiver | Three sessions | Retired Senior Corps Volunteers | Not given |

| Anderson & Weber. 201543 | Showing photographs of cars | Sitting with facilitator at a computer | Give entry point to reminiscence | Home (retirement center) | One-on-one sessions | One to two sessions each | The researchers | Between 33–63 mins |

| Bohlmeijer. 200926 | Theme based story-telling | Integrative reminiscence narrative therapy | Life evaluation integrating negative life events | N/S Community based |

Groups with a maximum of 4 people | Weekly | A counsellor | 8 x 2-hour sessions |

| Chonody. 20136 | Writing shared with group and blogging online | Group reminiscence using storytelling | Empower older people and connect to others | Senior center plus outings | A face-to-face open group | Weekly for 10 months | Group leader and volunteers | 90 mins |

| Hanaoka. 201128 | Social theme based life review using odor | RT based on psychological therapy | Improve depression, psychological wellbeing | RT center | Groups of 4 to 6 older people | 8 fortnightly sessions held over 4 months | Staff member and older adult co-leader | 90 mins |

| Hanaoka. 201827 | Social theme based life review using odor | RT based on psychological therapy | Maintain mental health, wellbeing and cognition | 7 regional community center | Group of 4–6 older people | 8 fortnightly sessions held over 4 months | Nurses or care workers | 90 mins |

| Jo. 201529 | Theme based with music, art, photos, gardening | Group Reminiscence with focus on life stages | To decrease depression and increase quality of life, EI, SS, ADLs | Mental health center | Single group with 19 people b | 8 sessions over 2 months | Not stated | 2.5 hours |

| Kanayama. 200344 | Topics, books, questions, sharing, trivia; problems | Unstructured Daily messages posted online | To construct online social support relationships | Online | Virtual community | Daily for 10 months | A non-active participant and volunteers | Not applicable |

| Korte.a 201230 | Integration of life events, stories, goals, discussion | Life-review reminiscence | To cope with present life events and form goals | Mental healthcare institutions | Groups of 4 to 6 older people | Not stated | Psychologists and other therapists | 8 two-hour sessions |

| Lukow. 201331 | Based on four tenets of mattering | Structured group reminiscence | To create greater sense of mattering | Club at retirement community | Group program face to face | 10 sessions over 5 weeks | Two counselors | 105 mins |

| Osmond 201845 | Discussion using photographs of marching girls | Informal | To elicit value and meaning of marching | Community | Face to face in groups | 2 consecutive days | Aboriginal Elder | Over 2 hours each session |

| Pearson. 200632 | Themes such as family, turning points, emotions, stress, meaning | Life Review using a guided autobiographical approach | To reintegrate past events into ones’ life and examine them | At home or senior center | 3 randomly assigned groups | Once a week for 6 weeks | Psycho-therapist | 90 mins |

| Rawtaer. 201513 | Four groups - Tai Chi; Mindfulness; Music; Art Therapy | Structured to suit the different groups | Prevention of depression and anxiety | Community health centers | Usually in groups, for four interventions | Intensity decreases over 12 months | Nurses, instructors, and trainers | 90–120 mins |

| Ren. 202133 | Reminiscence discussion in combination with exercise | Structured based on feedback from group | To address healthy aging during covid-19 pandemic | A quiet and spacious room in the community | Face to face in groups | Once a week for 8 weeks | Members of the research team | Exercise: 50–60 mins Control: 45 mins |

| Sass.a 202146 | Boccia, darts, table tennis, archery, discussion | Structured ‘Sporting Memories’ | To express masculine identity through sport | Community | Face to face in groups | Weekly for 11 months | Not stated | Two hours |

| Shellman. 20118 | Discussion in culturally similar groups | Interpersonal and Integrative reminiscence; life review | To promote positive mental health and well being | Senior centers and churches | Face to face groups | 6 one off sessions | An African-American research assistant | Not given |

| Shellman. 200934 | Theme based structured life review questions to facilitate memories | Interpersonal and Integrative reminiscence; life review | To decrease depressive symptoms by reframing thinking | Senior centers or church | Face to face groups | Weekly for 8 weeks | African American research assistants | 45 mins |

| Sherman. 198735 | Conversational topics reflecting life stages | Conventional life review | To enhance well-being and build friendships | Home and community | Groups of 6–10 people | 10 sessions, either weekly or fortnightly | A social worker | 90 mins |

| Smiraglia.a 201541 | A visit to a museum to touch artifacts, such as historic cameras | Semi-structured, allowing for group interests; conversations | To stimulate memory and social interaction; multisensory | Historical museum | Face to face Groups | Single sessions | A museum educator | 60 mins |

| Smiraglia.a 201548 | A visit to a museum to touch artifacts, such as historic cameras | Semi-structured allowing for group interests; conversations | To improve participants’ mood and socialize | Historical museum | Face to face groups | Single sessions | A museum educator | 60 mins |

| Somody.a 201014 | Identifying meaningful music that relate to life themes and goals | Structured. A Musical Chronology and Life song | To facilitate life review and increase wellbeing | A senior community center | Face to face groups | 6 group sessions. Twice a week over 3 weeks | A counselor | 135 mins |

| Stevens-Ratchford. 199336 | Slide show of past objects, people and events, writing and then discussion | Structured Life Review | To reduce depression and improve self-esteem | N/S Community based | Divided into male and female groups | 6 sessions; 2 sessions a week for 3 weeks | Occupational therapist | 2 hours each session |

| Tolson & Schofield a 201247 | Using football images as a basis for discussion | Semi-structured reminiscence | Cognitive stimulation | 1 RACF, 2 community 1 home | Group and individual | Established, ongoing | Reminiscence facilitators and volunteers | Ongoing |

| Woods. a 201237 | Topics and activities for dyads | Structured, manualized REMCARE | To improve relationships and decrease depression | Community centers | Large and small groups | 12 consecutive weeks then monthly for 7 months | Two trained facilitators in each center and volunteers | 2 hours |

| Wu. 201738 | Themes using old photographs depicting life stages | Structured RT | To reduce depression and anxiety | Participant homes | Individual | Six sessions over six weeks | A nurse with psychology counseling qualifications | 50–60 mins |

| Zauszniewski. 200439 | Lifespan themes used for socialization | Focused reflection reminiscence | To reduce negative emotions | Retirement communities | Focused reflection groups | Weekly for 6 weeks | A psychiatric nurse | 90–120 mins per session |

| Zhou. 201140 | Health education and weekly topics | RT using psychology | To explore options for high quality community nursing | Community | 4 experimental groups and 4 control groups | Weekly for 6 weeks | Trained community nurses | 90–120 mins per session |

Notes: aIndicates programs that were already existing in the community. All other programs were established and implemented for the purposes of the research; bAuthor contacted to confirm only one group was conducted (not multiple groups).

Abbreviations: ADLs, activities of daily living; EI, ego integrity; LIFE= Legacy Intervention Family Enactment; mins, minutes; N/S, not stated; pt, patient; RACF, Residential aged care facility; REMAIR, Reminiscence groups for people with dementia and their family caregivers; RT, reminiscence therapy; SS, social skills.

Programs were delivered through group sessions (n = 21),6,8,13,14,26–37,39–41,45,46,48 one-on-one (n = 3),38,42,43 both group and one-on-one (n = 1)47 and one virtual community online.44 Most programs consisted of between 6 and 10 sessions, lasting between 45 minutes and two hours. Programs were conducted at community locations, including churches and a museum (n = 13),8,13,26,27,33–35,37,41,45–48 at retirement/senior centers or a nursing home (n = 11),6,8,14,31,32,34–36,39,43,47 at health service centers (n = 5),13,28–30,40 at home (n = 4),32,38,42,47 and one online (n = 1).44 Programs were delivered by nurses, educators, a psychologist, a psychotherapist, a social worker, an occupational therapist, and counsellors (n = 12),13,14,26,28,30–32,35,36,38–40 authors/researchers (n = 6),8,29,34,42,44,46 other paid professions (n = 4),13,27,37,47 volunteers (n = 4),6,43,44,47 an Aboriginal elder (n = 1)45 and a museum educator (n = 2).41,48 Of the 27 included studies, only seven were evaluating established community-based programs14,30,37,41,46–48 with the remainder implementing the programs for the research.

Critical Appraisal

Quantitative Research

Based on the use of the McMaster critical appraisal tool, the study purpose was clearly articulated in all 17 studies, with clear information regarding sample size and justification. Most measures adopted in studies were reliable and valid, and reminiscence programs were described in detail. All studies identified clear information on data collection methods and analysis. Clinical implications and importance of findings were also included in all studies. Details are in Table 4.

Table 4.

McMaster Appraisal Table

| Author and Year | Study Purpose | Literature | Sample Numbers | Sample Detail | Sample Size Justified | Measures Reliable & Valid | Intervention Described | Contamination Avoided | Cointervention Avoided | Statistical Significance | Analysis and Methods | Clinical Importance | Dropouts | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bohlmeijer 200926 | Yes | Yes | 108 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | n/a | n/a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hanaoka 201128 | Yes | Yes | 22 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | n/a | n/a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hanaoka 201827 | Yes | Yes | 72 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | n/a | n/a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jo 201529 | Yes | Yes | 19 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | n/a | n/a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Korte 201230 | Yes | Yes | 202 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lukow 201331 | Yes | Yes | 19 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pearson 200612 | Yes | Yes | 36 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rawtaer 201513 | Yes | Yes | 101 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | n/a | n/a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ren 202133 | Yes | Yes | 121 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Shellman 200934 | Yes | Yes | 56 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sherman 198735 | Yes | Yes | 104 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Smiraglia 201541 | Yes | Yes | 114 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | n/a | n/a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stevens-Ratchford 199336 | Yes | Yes | 24 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | n/a | n/a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Woods 201237 | Yes | Yes | 488 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Wu 201738 | Yes | Yes | 27 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | n/a | n/a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zauszniewski 200439 | Yes | Yes | 43 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | n/a | n/a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zhou, 201140 | Yes | Yes | 59 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Qualitative Research

A review of the qualitative studies using the CASP checklist found that all studies clearly articulated an aim and purpose, but only six stated a known qualitative methodology. Recruitment, data collection and researcher relationship were described appropriately in eight studies. Data analysis was adequately described in six studies. Two studies were scant in their methodological reporting with findings not fully discussed.43,47 Details are in Table 5.

Table 5.

Qualitative Critical Appraisal Findings with CASP

| Author and year | Aim | Purpose is Qualitative | Research Design | Recruitment | Data Collection | Researcher Relationship | Ethics | Data Analysis | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen. 201642 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Anderson & Weber. 201543 | Yes | Cannot tell | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | No | Cannot tell | No | No |

| Chonody. 20136 | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kanayama. 200344 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes |

| Osmond. 201845 | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes |

| Sass. 202146 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Shellman. 20118 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Smiraglia. a 201548 | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Somody. 201014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tolson-Schofield. 201147 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Cannot tell | No |

Note: aAuthor contacted and confirmed that ethical approval was obtained and participants gave informed consent.

Participant Characteristics

The ages of participants ranged from 42 to 105 years. While this Systematic Review was focused on studies involving older people aged 50 years and over, the inclusion of one study with a single participant aged 42 years48 was deemed appropriate as the remainder of the participants met the eligibility criteria. Across the studies that reported the number of participants and their gender, the majority were women (n = 67%; 1190 women and 585 men). One study did not specify gender or age range of participants42 while both Smiraglia papers41,48 had the same participants (n = 114). Three studies included only women14,38,45 and two studies included only men.46,47 One Australian study45 included all Aboriginal women and two studies from the USA were all African American people.8,34 Seven studies reported participants to have depression,12,13,26,30,34,39,40 four studies reported participants to have dementia,29,37,46,47 three studies reported participants to have anxiety13,30,39 and one focused on people who were lonely.39

Outcome Measurements

Outcomes of interest in the quantitative studies included mental health – depression, anxiety, dementia (n = 12);13,26–30,32,34,36–38,40 life satisfaction (n = 7);27,29,30,33,35,36,40 memory (n = 4);28,30,37,38 mastery (n = 3);26,30,32 wellness (n = 3);31,37,40 mood (n = 3);31,37,41 positive/negative thoughts/feelings (n = 2);30,38 social connectivity (n = 2);29,31 mattering (n = 1);31 resilience (n = 1);33 affect (n = 1);40 Independence in daily living (n = 1);29 and loneliness (n = 1).33

Depression

Twelve studies used depression measurements. As indicated in Table 6, six studies27–29,32,38,40 used the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) while four26,30,34,39 used Centre of Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). One32 used the accepting the past scale (APS) as well as GDS, while another one39 used the Emotional Symptom Checklist (ESC) as well as CES-D. The others included Zung self-rating depression scale (SDS),13 and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).36 Of the 12 studies that used a depression measure, reminiscence featured in all, with life review,30 mattering31 and psychosocial intervention13 also used.

Table 6.

Overview of Quantitative Findings

| Depression | Anxiety | Loneliness | Quality of Life | Mastery | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D | SDS | GDS | BDI | ESC | Misc | SAS | HADS-A | RAID | ESC | ULS | SES | ABS | SIWB | Qol-AD | Misc | PMS | BRS | EIS | |

| Bohlmeijer 200926 | ↓* | ↑* | |||||||||||||||||

| Hanaoka 201827 | ↓* | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hanaoka 201128 | ↓* | NC a | |||||||||||||||||

| Jo 201529 | ↓ b | ↑* c | ↑* | ||||||||||||||||

| Korte 201230 | ↓* | ↓ * | ↑* | ||||||||||||||||

| Lukow 201331 | ↑* d | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pearson 200632 | ↓* | ↓* e | ↑ | ||||||||||||||||

| Rawtaer 201513 | ↓* | ↓* | |||||||||||||||||

| Ren 202133 | ↓* | ↑* | ↑* | ||||||||||||||||

| Shellman 200934 | ↓* | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sherman 198735 | ↑* f | ||||||||||||||||||

| Smiraglia 201541 | ↑* g | ||||||||||||||||||

| Stevens-Ratchford 199336 | ↓* | ↑* | |||||||||||||||||

| Woods 201237 | NC | ↑ h | |||||||||||||||||

| Wu 2018 38 | ↓* | ↓* | ↑* i | ||||||||||||||||

| Zauszniew-ski 200439 | ↓* | ↓* j | ↓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Zhou 201140 | ↓* | NC | ↑* | ||||||||||||||||

Note: aLSI-K, life satisfaction index (K); bSGDS, Short-form Geriatric Depression Scale; cLSI-A, Life satisfaction index (A); dMLQ, Meaning in life questionnaire; eAPS, accepting the past scale; f5F-WEL, Five Factor Wellness Inventory; gLSI-Z, Life satisfaction index (Z); hEQ-5D, European quality of life 5 dimensions; IGHQ, general health questionnaire; jReduction in depression significant after 6 weeks but not after 12 weeks. *Significant.

Abbreviations: ↓, decrease; ↑, increase; ABS, affect balance scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BRS, Brief Resilience Scale; CES-D, Centre of Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale; EIS – Ego Integrity Scale; ESC- Emotional Symptom Checklist; GDS, geriatric depression scale; HADS-A, hospital anxiety depression scale; MLQ, Meaning in life questionnaire; NC, no change; PMS, Pearlin Mastery Scale (beliefs about control over environment); QoL-AD, Quality of life Alzheimer's Disease; RAID, rating anxiety in dementia; SAS, Zung self-rating anxiety scale; SDS, Zung self-rating depression scale; SES, Rosenberg self-esteem scale; SIWB= Spirituality Index of Well-Being; ULS – UCLA Loneliness Scale – 8.

Mattering

Mattering is the general belief that you are important to others. One study31 used the Mattering Index to measure mood, via self-consciousness, self-esteem, self-monitoring, alienation, and perceived social support.

Anxiety/Loneliness

Of the five studies that used anxiety or loneliness measurements, two used Zung self-rating anxiety scale (SAS),13,38 with one each for hospital anxiety depression scale (HADS)30 and ESC.39 All anxiety measures from the four studies also included a measure for depression. UCLA Loneliness Scale – 8 (ULS)33 was the single measurement for loneliness.

Quality of Life

There were eleven studies28–31,33,35–38,40,41 that measured quality of life using 11 different tools. Two studies37,40 used tools that also included life satisfaction, self-esteem, and well-being.

Mastery

There were five26,29,30,32,33 studies that measured mastery. Three26,30,32 used the Pearlin Mastery Scale (PMS) (beliefs about control over environment), while one29 used the Ego Integrity Scale (EIS) and one33 used Brief Resilience Scale (BRS).

Quantitative Findings

Collectively, quantitative research, which investigated the effectiveness of reminiscence programs, generally reported positive findings irrespective of the program parameters and outcomes measured.

Depression

There was consistent evidence from the literature on the positive impact of reminiscence on depression among participants. All but one study reported statistically significant reduction in depression. The study by Jo,29 which was a pre-post study design with a small sample size of 19 people with dementia measured changes in depression using Short-form Geriatric Depression Scale (SGDS). Whilst there were decreases in depression found, this was not significant. Similarly, Pearson32 used two depression measures (GDS and APS) to compare the effect of cognitive behaviour therapy, reminiscence therapy and education (control group). Pearson32 found that while there were significant within-group differences in depression scores (GDS), there were no between group differences. However, for the APS measure, there were significant differences between the pre and post test scores for both the reminiscence and cognitive behaviour therapy groups, but not the control group. Zauszniewski,39 which also used two depression measures (CES-D, ESC) reported a reduction in depression at six weeks after the intervention, although this effect was not sustained at 12 weeks. Therefore, collectively the evidence base indicates that reminiscence programs may have a positive impact on depression.

Mattering

Findings reported by Lukow31 in relation to mattering were mixed and not statistically significant, with a slight decrease in mattering occurring for the intervention group from pre to post test and a slight increase in mattering for the control group.

Anxiety/Loneliness

There was consistent evidence from the literature on the positive impact of reminiscence on anxiety among participants. All studies reported a reduction in anxiety, with a significant effect noted for anxiety measures SAS and HADS.13,30,38 Results for one study39 were not statistically significant revealing an increase in anxiety immediately after commencing participation in the program, which decreased over time at six weeks and 12 weeks. The one study which measured the effect of reminiscence programs on loneliness33 found positive outcomes but more research is needed.

Quality of Life

All but three studies28,30,37 reported significant increases in quality of life, giving consistent evidence for the positive impact of reminiscence on quality of life. Woods,37 which also included carers in their research, used two quality of life measurements (Quality of life Alzheimer's Disease (QoL-AD) and European quality of life 5 dimensions (EQ-5D)) with conflicting findings. While there was no change in the Qol-AD measure, there was an increase in EQ-5D, which was not statistically significant. Similar conflicting findings were reported by Zhou40 whereby significant positive increases in quality of life were reported using the affect balance scale (ABS), but no change was recorded using the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (SES).

Mastery

There were significant findings in four of the studies,26,29,30,32,33 with the exception of Pearson32 which showed an increase which was not significant.32 There were reported increases in sense of control over their own lives (PMS), recovery from stressful situations (BRS) as well as significant increases on feelings of autonomy, competency and connection to others (EIS).

Qualitative Findings

Thematic analysis identified three main themes: program processes, program ingredients and program benefits. Program processes were the tools used and skills required for delivery of reminiscence programs. Program ingredients were the activities and approaches adopted by reminiscence program facilitators with a key program ingredient being the need to “draw from the past”. Two program benefits were identified, including “relationship with others” and “improved sense of self”. Quotes drawn from qualitative studies have been provided to illustrate themes (Table 7).

Table 7.

Overview of Qualitative Findings

| Qualitative Findings | Quote | Papers Included in Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1 Program processes | “I think you guys said that we should see them once a week, but I think that’s too close. So I was giving the clients two weeks apart” (Allen et al, 2016, p. 363).42 “the point of being here is that we are allowed to share our stories” (Chonody & Wang, 2013, p. 87).6 “find everybody’s level, as an individual, and you have just got to try and work things in to suit each person. I can understand whereabouts to come in, where to sit back, where to interject on a subject and change a subject” (Tolson & Schofield, 2012, p. 66).47 “You will notice if it’s not engaging them they will go silent or just smile … but if they’re smiling they’re fairly happy … you just try and provide as many varied things as possible and hope that you spark something” (Sass et al, 2021, p. 2179).46 |

[6,14,42,46,47] n = 5 |

| Theme 2 Program ingredients | “the reminiscence was so powerful to these women …[the music] brought it out for them … I think several of them were incredibly surprised that the music was as powerful as it was at helping them remember their life stories or talking about and sharing” (Somody, 2010, p. 219).14 “For some people … who might have problems communicating and cannot just jump in [with comments] … they love having a go at darts and they do archery … some of them would rather forego the bit of chat at the start and just crack straight on with the activities” (Sass et al, 2021, p. 2177).46 “thinking about the past to prepare for death makes me depressed” (Shellman et al, 2011, p. 352).8 |

[6,8,14,43,44,46–48] n = 8 |

| Theme 2 Program ingredients: Subtheme 1 Drawing on the past | “We are not only able to go back and talk about old memories and things that happened years ago but also we can compare those times with these times”. (Chonody & Wang, 2013, p. 88)6 “[we] came from …oppression, racism, poverty, you name it, but we went on … make us feel proud, and when I think of our old people, the sacrifice that they’ve made for us … that’s the memories I have”. (Osmond & Phillips, 2018, p. 572).45 “When I decided to meet with you I felt there could not be much to talk about. I was wrong. I really enjoyed the meeting with you—especially recalling so much about the cars”. (Anderson &Weber 2015, p. 478)43 “This was so different … when I first came in here I said he is going to start talking and asking me a bunch of stupid questions. I was wrong. Now, I have a whole new knowledge about myself with reminiscing”. (Shellman et al, 2011, p. 352)8 |

[6,8,14,43–48] n=9 |

| Theme 3 Program Benefit: Subtheme 1 Relationships with others | “Many of the people here are just like family to me. This is one group that I truly enjoy. And all the [volunteers]. They are just marvelous people. I like how they treat us as people, not just old folks”. (Chonody and Wang, 2013, p. 88)6 “I do not have time to go out and socialize because I nurse my wife, who is not able to speak and eat by herself. I am very lonely with no one to talk to. I enjoy having responses from folks”. (Kanayama, 2016, p. 280).44 “Participants frequently checked to ensure that neighbors had seen an object being passed around; residents also showed each other how something worked or explained what the parts of an object were. They gave advice about using the object and demonstrated actions for their peers” (Smiraglia, 2015, p. 242)48 |

[6,8,14,42,44–48] n=9 |

| Theme 3 Program Benefit: Subtheme 2 Improved sense of self | “It [the class] allowed me to express myself verbally and also in written papers. I like this because it gives me information on how to express myself” (Chonody & Wang, 2013, p. 87).6 “If we didn’t think anything of ourselves before, we do now. We’re walking out of here with a brand new knowledge of ourselves. We are very special people, this age group … if people only realise what we know” (Shellman et al, 2011, p. 352).8 “she could share about her own personal growth, which to me is the most brave thing … I felt like she left much more empowered, much more positive, than she came”. (Somody, 2010, p. 222).14 |

[6,8,14,42,44,46,47] n = 7 |

Theme 1: Program Processes

The use of a program manual was useful,42 but facilitators reported this also restricted their ability to use their intuition. Facilitators needed to have skills in patience46 and providing encouragement47 without pushing too hard to force participation.46 For group programs, facilitators aimed to create an environment where people felt safe to participate.6,14 They needed to be well prepared14 and able to adapt quickly depending on the group mood and participant capabilities.47 Given participants may not always be able to express their feelings, observational skills and varied approaches to engagement were required.46 Generally, program facilitators reported finding their involvement rewarding14 and cost-effective.42 Community settings (such as a hotel) were preferred for inclusion as participants found this more relaxed when compared with a clinical environment.47

Theme 2: Program Ingredients

At the start of each new reminiscence program, ice-breaking techniques and inclusive activities were important.44 Defining group purpose and goals up front promoted trust and security,14 while having some chronology to program content helped to order memories.43 Initially, agreeing to participate in programs was dependent on people being willing to “give it a chance” and sometimes relied on someone bringing them along and giving encouragement to help them feel safe.6 Consistency of attendance and making sure everyone could hear were necessary to avoid feeling disconnected from the group.14 Having a topic or occupation to focus the program each week supported engagement, as well as playfulness, humor,46–48 and gentle physical activity.46 Even though the sessions had a focus, occasionally participants would talk about other things and facilitators would follow their lead.47 Where participants were of similar age and background, they were able to find things in common leading to natural disclosure, and further interactions.8,44–46 Sometimes there was discomfort about the topics being discussed, such as regret and forgiveness, and grief,14 and concerns about sharing stories from their past because they evoked sadness14 or meant reliving past trauma.8 Some did not like the idea of using reminiscence to prepare for death and found this depressing.8

Subtheme 2.1 Drawing on the Past

Drawing on the past is a key program ingredient. Program designs that involved participants drawing on and disclosing past experiences were common.6,8,43–45,47,48 The group process helped participants to relate the memories of others to their own and to extend their recall of memories.14 Participants connected based on past experiences,6,8,44 and nostalgia.6,45 For example, there was pride expressed about past achievements during times of oppression and trauma.45 Participants in Somody14 all found a connection to the music that was shared in the sessions and also found the process supported them to reconnect with memories they had forgotten. The group structure in Sass46 enabled reminiscence about past involvement in sport and evoked some vivid memories that drew them into a social world where others shared similar experiences. Rekindled memories elicited expressions of enjoyment and lifted mood.46

Theme 3: Program Benefits

Two key benefits were identified across the qualitative studies reviewed, these being “Relationships with others” and “improvements in sense of self”. These two key benefits appear to be a result of the program processes and ingredients through drawing on the past.

Subtheme 3.1 Relationships with Others

The structure of reminiscence programs enabled rapport building between different participants and with facilitators. There was a tendency for participants to take seats in the same position each week, suggesting growing sense of group belonging.47 As noted previously, playfulness was a key ingredient in the programs46–48 with humor (sometimes self-deprecating) and laughter featuring,48 leading to camaraderie, friendly banter and proud showing off.46–48 Being with others assisted participants to cope with life challenges and process some difficult emotions.14,44 Program participants came to care about the other group members and they valued the mutual support they provided each other.6,8,14,48 The opportunity to reunite with women from their past in Osmond and Phillips45 reinforced emotional bonds and expressions of grief from those from their group who were no longer alive.

The building of friendships/new relationships and connecting with people8,45 provided opportunity for self-expression and meant participants kept attending the sessions.6 The new relationships meant they had friends who were often in similar situations who they could turn to in times of need.44 Involvement in the program also prompted facilitators to think about their relationships and to rekindle their family relationships.42 Generally, the communication between participants and their families and friends was enhanced by the programs, including sharing past experiences on blogs and using the internet.6,44 On the other hand, in one study the relationships between the invited family or friends of participants were reported as unchanged.14

These new connections were a powerful means of relational growth and reported as a valued outcome for participants.14,44 The construction of relationships occurred through sharing personal essays through email,44 public sharing of blogs on social media.6 Participants enjoyed getting feedback and comments from their contributions and this helped them to reveal more of themselves and be reflective.6,44 They also began to feel connected to the broader society, which was highly valued for those who may have felt isolated due to their personal circumstances (for example being a carer).44

Subtheme 3.2 Improved Sense of Self

For some, participating in a reminiscence program was something they had always wanted to do, and they felt a sense of accomplishment.42 Participants also reported feeling good about themselves as reminiscence programs provided a place to feel heard6 and to try new things.6,44 One program had participants doing gentle physical activity sometimes using equipment (eg, darts) which promoted friendly competition and self-esteem, which was particularly important for some who struggled with self-worth and communicating.46 For people with dementia, attendance at the program and the group environment led to them being stimulated and they were described as being both alert and calm.47 Reminiscence sessions were sometimes transformative, leading participants to get to know and see themselves through a new lens,8 be more reflective and self-aware14 and to “feel better” after sharing.44

Prior to the music program, the five women had lost sight of thinking about their future and afterwards some of them could see new possibilities and hope for the future, including traveling and meeting new people (including possible romance).14 In other reminiscence programs, those who had health issues were able to evoke positivity in their outlook from their participation.42 Discussions online sometimes implied future plans44 and in some circumstances there was effort required to shift negative thought processes to a more positive frame.44

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to explore participants experiences of, and outcomes from, community-based reminiscence programs. Twenty-seven studies from quantitative and qualitative research paradigms contribute to the evidence base for this review. Collectively, there appears to be consistent evidence to indicate that community-based reminiscence programs may have positive effects on health and social outcomes. While these were positive findings, the literature also highlighted considerable heterogeneity in the parameters underpinning reminiscence programs, suggesting the need for greater development of the theory base and guides for delivery.21 In addition, there were some concerns about methodological quality of the evidence base.

Positioning the programs in the community, such as local hotels, museums or community centers seemed favorable over more medicalized settings. Creating programs in community settings may improve their accessibility for older people living at home who may not have many social connections and feel lonely.49 The prevalence of loneliness is increasing for older people2,50–52 and has been linked to depressive symptoms.53–55 The opportunity to meet new people as well as collectively reflect and chat about past times appears to be a useful approach to overcome being alone.56,57 While only one quantitative study33 in this review focused on measuring the impact of a reminiscence program on loneliness, the qualitative studies found that new relationships and friendships were built from reminiscence programs. Decrease in depression and anxiety identified in this review could, in part, be due to overcoming feelings of loneliness.58,59 These findings are consistent with results identified in similar community-based programs targeting older people, (such as Men’s Sheds60) and other systematic reviews of the literature exploring programs in residential aged care facilities.61,62

Qualitative studies indicated that reminiscence programs can assist with improving sense of self. This finding aligns with some of the original tenets behind the delivery of reminiscence programs63 and may relate to the improvements in quality of life found in this review. There are possible links between quality of life and having opportunities to reflect on the past and build relationships with others.64 Cammisuli et al found that reminiscence therapy not only slowed cognitive deterioration but also reduced depressive symptoms and improved quality of life.64 Reminiscence programs provide opportunities for older people to affirm (or reaffirm) cognitive abilities (particularly memory recall) which in turn may enhance self-esteem and spark a positive sense of self. Recounting past events and stories can also provide a sense of mastery over personal perceptions of declining cognition. The opportunity to touch, feel or see old objects/pictures or listen to sounds/voices/music during reminiscence sessions can rekindle emotions such as pride and self-esteem.

The sharing of personal stories with others during reminiscence sessions can also provide an opportunity to feel noticed, cared for and that they matter. While only one quantitative study31 measured Mattering (with findings indicating change had not occurred over time), it could be argued that the collective findings from this systematic review indicate reminiscence programs can contribute to sense of mattering. As Flett65 indicates,

mattering is essentially the feeling of being valued and having personal significance to others. The person who has a sense of mattering to others is someone who feels valued and cared for.

Building new friendships, rekindling old ones, and receiving feedback from others through reminiscence sessions can create opportunities for participants to feel connected and valued (mattering). Being a member of a friendship group can also assist with reconciling negative life issues, and forming interpersonal resiliency.65

This systematic review provides evidence that reminiscence programs could be used for social prescription purposes66 to assist with alleviating mental health issues such as depression and anxiety as well as to overcome social isolation and loneliness. Social prescribing has emerged in the US, UK and Canada in recent years as a referral pathway that gives non-biomedical and non-pharmaceutical options for social issues (such as loneliness and social isolation) as well as mental health issues (such as depression and anxiety).67

Reminiscence programs in populations prone to negative thinking may have negative outcomes such as sadness, particularly if the reminiscence sessions are prolonged and segue into a longing for the past.5,68 Skilled facilitators appeared to be pivotal in building rapport, responding to participant cues and noticing when thinking is becoming unhelpful. This review found that skilled facilitators can promote a positive participant experience which was a finding consistent with a systematic review of programs in residential aged care61 The value of trained facilitators has been reported in published models for reminiscence with predictability and safety foregrounded as pivotal to program enjoyment.47,69 Interestingly, the role of reminiscence program facilitators as a key ingredient in program delivery and success has minimal attention in evidence-based guidelines for reminiscence therapy.70 Having said that there is a recommendation that facilitators be trained for the purposes of recognizing adverse outcomes of reminiscence such as recalling distressing memories or becoming uncomfortable.71

While findings from this systematic review indicate generally positive results, there is a paucity of studies focused on community reminiscence programs compared to those conducted in aged care and nursing homes.61,62,72 There is also a need for more research exploring the relationship between participating in reminiscence programs and loneliness and a sense of mattering for people living in the community. Given the convergent findings in this systematic review, the required skills of facilitators are also worthy of more scholarly attention. Developing a deeper understanding of how best to deliver reminiscence programs will improve program outcomes.73

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this systematic review is the inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative research designs thus providing in-depth understanding of the impact and experiences of people involved in reminiscence programs. In addition, the study was informed by best practice standards in the conduct and reporting of a systematic review using PRISMA guidelines. However, some caution should be applied as there are inherent limitations of any systematic review. While the quantitative findings demonstrated statistically significant changes in depression, anxiety, loneliness, quality of life and mastery, less than half of the studies (eight out of 17) were randomized controlled, thus compromising claims of causality. It should also be noted while the reminiscence programs included in this review were provided in a community setting, the majority of studies (n = 22) curated these programs exclusively for the purpose of the research. Only five reminiscence programs had already been established prior to research being conducted with participants. As such, the research parameters established for the majority of the studies may not be able to be replicated in practice by community facilitators. Another limitation relates to the length of all studies reviewed, with only one study indicating any findings based on longitudinal, ongoing data collection approaches.39 As such, the effects of reminiscence programs over time remain relatively unknown.

Conclusion

The impact and experience of reminiscence programs for older people appears to be mostly positive for health and social outcomes. The process of sharing stories provided opportunities for participants to improve their sense of self, to feel noticed, and that they matter. This likely contributed to decreasing depression and loneliness as well as building relationships. The success of reminiscence programs is likely reliant on skilled facilitators who can get the group for success through setting up group dynamics, use of ice breakers and balancing structure with spontaneity. While catering to local contexts is important, as reminiscence programs gain popularity, its implementation in practice should also be underpinned by clear and reproducible practices. Further research that has standardized reminiscence programs in the community with long term follow-up would strengthen the evidence base. This research would be used to guide further program development.

Disclosure

Dr Carolyn Murray reports non-financial support as an associate editor for Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, grants from arts and health collaborative alliance and office for ageing well (SA Government), outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia – Stories from the Census. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogrin R, Cyarto EV, Harrington KD, et al. Loneliness in older age: what is it, why is it happening and what should we do about it in Australia? Austr J Ageing. 2021;40(2):202–207. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruggencate TT, Luijkx KG, Sturm J. Social needs of older people: a systematic literature review. Ageing Soc. 2018;38(9):1745–1770. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X17000150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coll-Planas L, Watchman K, Doménech S, et al. Developing evidence for football (Soccer) reminiscence interventions within long-term care: a co-operative approach applied in Scotland and Spain. J Am Med Direct Assoc. 2017;18(4):355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henkel L, Kris A, Birney S, et al. The functions and value of reminiscence for older adults in long-term residential care facilities. Memory. 2017;25(3):425–435. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2016.1182554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chonody J, Wang D. Connecting older adults to the community through multimedia: an intergenerational reminiscence program. Activit Adapt Aging. 2013;37(1):79–93. doi: 10.1080/01924788.2012.760140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler RN. The life review: an interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry. 1963;26(1):65–76. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1963.11023339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shellman J, Ennis E, Bailey-Addison K. A contextual examination of reminiscence functions in older African-Americans. J Aging Stud. 2011;25(4):348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2011.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evers C. Early psychosocial interventions in dementia: evidence-based practice. Ageing Soc. 2010;30(4):724–726. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X10000024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holroyd‐Leduc J. Preserving the Memories: Managing Dementia, in Evidence‐Based Geriatric Medicine. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:73–93. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan F, O’Shea E, Murphy K. ‘Seeing me through my memories’: a grounded theory study on using reminiscence with people with dementia living in long-term care. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(23–24):3564–3574. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yen H, Lin L. A systematic review of reminiscence therapy for older adults in Taiwan. J Nurs Res. 2018;26(2):138–150. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rawtaer I, Mahendran R, Yu J, et al. Psychosocial interventions with art, music, Tai Chi and mindfulness for subsyndromal depression and anxiety in older adults: a naturalistic study in Singapore: psychosocial interventions in late life. Asia-Pac Psychiatry. 2015;7(3):240–250. doi: 10.1111/appy.12201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Somody CF. Meaning and Connections in Older Populations: A Phenomenological Study of Reminiscence Using “A Musical Chronology and the Emerging Life Song”. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark M, Murphy C, Jameson-Allen T, et al. Sporting memories & the social inclusion of older people experiencing mental health problems. Ment Health Soc Inclu. 2015;19(4):202–211. doi: 10.1108/MHSI-06-2015-0024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connellan K. Senses of memory in dementia care: the transcendent subject. Art Ther Online. 2018;9(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan Z, Dong M, Lin L, et al. Effectiveness of reminiscence therapy interventions for older people: evidence mapping and qualitative evaluation. J Psychiatr Ment Health NurS. 2023;30(3):375–388. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuevas PEG, Davidson PM, Mejilla JL, et al. Reminiscence therapy for older adults with Alzheimer’s disease: a literature review. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(3):364–371. doi: 10.1111/inm.12692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office for National Statistics. Profile of the older population living in England and Wales in 2021 and changes since; 2011. [12th August 2023]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/articles/profileoftheolderpopulationlivinginenglandandwalesin2021andchangessince2011/2023-04-03. Accessed December 5, 2023.

- 20.U. S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2020 profile of older Americans; 2021. [12th August 2023]. Available from: https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/aging%20and%20Disability%20In%20America/2020Profileolderamericans.final_.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2023.

- 21.Webster JD, Bohlmeijer ET, Westerhof GJ. Mapping the future of reminiscence: a conceptual guide for research and practice. Res Aging. 2010;32(4):527–564. doi: 10.1177/0164027510364122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG The PRISMA Group, reprint—preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phys Ther. 2009;89(9):873–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Law M. Critical review form - quantitative studies. 1998.

- 24.Stern C, Lizarondo L, Carrier J, et al. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evid Implement. 2021;19(2):120–129. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bohlmeijer E, Kramer J, Smit F, et al. The effects of integrative reminiscence on depressive symptomatology and mastery of older adults. Commun Ment Health J. 2009;45(6):476–484. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9246-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanaoka H, Muraki T, Ede J, et al. Effects of olfactory stimulation on reminiscence practice in community‐dwelling elderly individuals. Psychogeriatrics. 2018;18(4):283–291. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanaoka H, Muraki T, Yamane S, et al. Testing the feasibility of using odors in reminiscence therapy in Japan. Phys Occup Ther Geriatrics. 2011;29(4):287–299. doi: 10.3109/02703181.2011.628064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jo H, Song E. The effect of reminiscence therapy on depression, quality of life, ego-integrity, social behavior function, and activities of daily living in elderly patients with mild dementia. Educ Gerontol. 2015;41(1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2014.899830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korte J, Cappeliez P, Bohlmeijer ET, et al. Meaning in life and mastery mediate the relationship of negative reminiscence with psychological distress among older adults with mild to moderate depressive symptoms. Eur J Ageing. 2012;9(4):343–351. doi: 10.1007/s10433-012-0239-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lukow HR. Structuring Reminiscence Group Interventions for Older Adults Using a Framework of Mattering to Promote Wellness. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson L. The Effect of Integrative Reminiscence on Depression, Ego Integrity and Personal Mastery in the Elderly. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren Y, Tang R, Sun H, et al. Intervention effect of group reminiscence therapy in combination with physical exercise in improving spiritual well-being of the elderly. Iran J Public Health. 2021;50(3):531–539. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v50i3.5594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shellman JM, Mokel M, Hewitt N. The effects of integrative reminiscence on depressive symptoms in older African Americans. West J Nurs Res. 2009;31(6):772–786. doi: 10.1177/0193945909335863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherman E. Reminiscence groups for community elderly. Gerontologist. 1987;27(5):569–572. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.5.569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevens-Ratchford RG. The effect of life review reminiscence activities on depression and self-esteem in older adults. Am J Occup Ther. 1993;47(5):413–420. doi: 10.5014/ajot.47.5.413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woods RT, Bruce E, Edwards RT, et al. REMCARE: reminiscence groups for people with dementia and their family caregivers - effectiveness and cost-effectiveness pragmatic multicentre randomised trial. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(48):v–xv. doi: 10.3310/hta16480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu D, Chen T, Yang H, et al. Verbal responses, depressive symptoms, reminiscence functions and cognitive emotion regulation in older women receiving individual reminiscence therapy. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(13–14):2609–2619. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zauszniewski JA, Eggenschwiler K, Preechawong S, et al. Focused reflection reminiscence group for elders: implementation and evaluation. J Appl Gerontol. 2004;23(4):429–442. doi: 10.1177/0733464804270852 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou W, He G, Gao J, et al. The effects of group reminiscence therapy on depression, self-esteem, and affect balance of Chinese community-dwelling elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;54(3):e440–e447. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smiraglia C. Museum programming and mood: participant responses to an object-based reminiscence outreach program in retirement communities. Arts Health. 2015;7(3):187–201. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2015.1010443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen R, Azuero CB, Csikai EL, et al. “It was very rewarding for me”senior volunteers’ experiences with implementing a reminiscence and creative activity intervention. Gerontologist. 2016;56(2):357–367. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson K, Weber K. Auto therapy: using automobiles as vehicles for reminiscence with older adults. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2015;58(5):469–483. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2015.1008169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanayama T. Adults ethnographic research on the experience of Japanese elderly people online. New Media Soc. 2016;5(2):267–288. doi: 10.1177/1461444803005002007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osmond G, Phillips M. Indigenous women’s sporting experiences: agency, resistance and nostalgia. Austr J Polit His. 2018;64(4):561–575. doi: 10.1111/ajph.12516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sass C, Surr C, Lozano-Sufrategui L. Expressions of masculine identity through sports-based reminiscence: an ethnographic study with community-dwelling men with dementia. Dementia. 2021;20(6):2170–2187. doi: 10.1177/1471301220987386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tolson D, Schofield I. Football reminiscence for men with dementia: lessons from a realistic evaluation. Nurs Inq. 2012;19(1):63–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00581.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smiraglia C. Qualities of the participant experience in an object-based museum outreach program to retirement communities. Educ Gerontol. 2015;41(3):238–248. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2014.954493 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Todd C, Camic PM, Lockyer B, et al. Museum-based programs for socially isolated older adults: understanding what works. Health Place. 2017;48:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lasgaard M, Karina F, Mark S. “Where are all the lonely people?” a population-based study of high-risk groups across the life-span. Social Psych Psych Epidem. 2016;51(10):1373–1384. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1279-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luhmann M, Hawkley LC. Age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to oldest old age. Develop Psychol. 2016;52(6):943–959. doi: 10.1037/dev0000117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Victor CR, Yang K. The prevalence of loneliness among adults: a case study of the United Kingdom. J Psychol. 2012;146(1–2):85–104. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2012.629501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hand C, Morin S, Leslie W, et al. Social isolation in older adults who are frequent users of primary care services. Can Fam Phy. 2014;60(4):324–329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hawkley C, Hawkley LC, Waite LJ, et al. Loneliness, health and mortality in old age: a national longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(74):907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]