Abstract

PURPOSE

The purpose of this mixed-methods psychometric study was to translate and adapt the Arabic Pain Care Quality (APainCQ) Survey to Arabic and to measure the quality of pain care provided to Arab patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study used an iterative, mixed-methods approach that employed cognitive interviews, expert content analysis, and factor analysis to develop the APainCQ Survey. The study was conducted at Dubai Hospital, Dubai Health Authority, United Arab Emirates. Arabic-speaking patients admitted to the oncology/hematology inpatient units with a minimum 24-hour stay were eligible for the study.

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 155 patients. The iterative exploratory factor analysis process resulted in the sequential removal of three items. The results of the significant Bartlett test (P < .001) of sphericity and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test of 0.93 for both the health care team scale and the nurse scale. The total variance explained was 76.17% for the health care team scale and 60.91% for the nurse scale, which explained 56.51% for factor 1 with 14 items and 4.40% for factor 2. Regarding internal consistency reliability, Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega for the health care team scale and nurse scale were high; both values were .95. Internal consistency reliability of pain assessment and pain management subscales of nurse scales were also high, with values of 0.96 and 0.79, respectively. Moreover, there was a moderate correlation (r = 0.66; P < .001) between the two subscales in the nurse scale.

CONCLUSION

This study provides evidence that the APainCQ is a reliable and valid measure of pain dimensions, including pain management and monitoring. This APainCQ scale can potentially expand research and clinical assessment in the Arab world.

APainCQ Survey used a mixed-methods approach, with variance explained by health care team and nurse scales.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is a major global cause of morbidity and mortality, causing nearly 10 million deaths.1,2 Pain is a significant issue for patients, with 55% experiencing it during anticancer treatment and 66.4% with advanced, metastatic, or terminal disease.3,4 Pain can persist after treatment.5,6

CONTEXT

Key Objective

A mixed-methods psychometric study aimed to translate and adapt the Pain Care Quality Survey to Arabic and measure the quality of pain care provided to Arab patients.

Knowledge Generated

The study used an iterative, mixed-methods approach to develop the Arabic Pain Care Quality Survey at Dubai Hospital. It involved 155 patients, with cognitive interviews, expert content analysis, and factor analysis. Results showed high internal consistency reliability for both health care team and nurse scales. This study provides a valuable tool to provide baseline data on cancer pain management satisfaction and quality of care among Arab-speaking adult patients with cancer, which was not available before.

Relevance

The validity of this tool can pave the way for large-scale studies in Arab-speaking countries and can be used as a standard tool to benchmark pain management quality within the measured patient cohort.

Unrelieved pain in patients with cancer often leads to depression, anxiety, altered mood, functional impairment, and decreased quality of life.7 In up to 90% of cases, cancer pain can be eliminated or effectively managed.8 Despite advances in pain management, unrelieved pain remains a significant problem,9 with 38% reporting moderate to severe pain.3 The WHO10 recommends national pain relief policies and programs for community and health care organizations.

To improve the quality of pain care for patients with cancer, it is essential to measure pain care quality accurately.11 A few methods exist for measuring the quality of pain management care.12,13 However, insufficient or unstructured documentation in the electronic health record (EHR), difficulties in extracting data from the EHR, and a lack of adherence to regular checklist completion are limitations of such approaches.14,15 Most patient-reported measures focus on pain management satisfaction.16 In addition, patient-centered care now encompasses a cultural shift in care delivery, commencing with the patient's first encounter upon entering a facility.17 In the acute care setting, pain assessment and management are the responsibility of nurses and the interdisciplinary care team, making it a priority area.18

Pain management is crucial for hospitalized patients, and the interdisciplinary team, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, rehabilitation therapists, and social workers, may also play a role. Patient perceptions of care are not discipline-specific, and measurements are global. Nurses are the primary pain management providers, and their impact is crucial. A comprehensive method should be developed to assess the quality of pain management care, considering the interdisciplinary care team's responsibility and the impact of nurses' responses on patient pain. Therefore, measuring the quality of care is essential for various stakeholders within health care systems, and it serves as the foundation for various quality assurance and improvement strategies.19

One of the best examples of measures of pain care quality is the Pain Care Quality (PainCQ) Survey. The PainCQ surveys, consisting of two surveys, the Interdisciplinary Care Survey (PainCQ-I) and Nursing Care Survey (PainCQ-N), were developed and tested to evaluate the quality of pain care from the patient's perspective.18,20,21

PainCQ-I comprises 11 items and two subscales: Partnership with the Health Care Team, measuring collaboration between team members and patients, and Comprehensive Interdisciplinary Pain Care, focusing on the whole person's pain impact.

The PainCQ-N consists of 22 items divided into three subscales: Being Treated Right, representing care provided by concerned nurses who understand and respond promptly to a patient's pain; Comprehensive Nursing Pain Care, reflecting pain management provided by nurses, including patient education and nonpharmacologic approaches; and Efficacy of Pain Management, indicating that patient comfort results from medications that work quickly and effectively. For all subscales, Cronbach's alphas range from .76 to .95.21

This instrument has been used to evaluate the quality of pain care in studies12,22,23; however, it is currently only available in English and Chinese.18,20,21,24 Unfortunately, no other lingual translations are known. Notably, this survey was initially designed to include acute and chronic pain, as pain can be acute, such as the pain felt after cancer surgery, or chronic and progressive as the disease progresses. Patients with cancer, the majority of whom are elderly, also suffer from chronic comorbid conditions.

Inadequate cancer pain management is a current issue in the Arab world.25,26

Therefore, before developing appropriate cultural approaches to improve this population's pain care, a greater understanding of the quality aspects of pain care is a crucial first step. Moreover, no patient self-reported Arabic pain care quality scales were found in the literature,27 which is desired, as self-report provides a quality perspective from the patient's personal experience.

Therefore, this mixed-methods psychometric study aimed to translate and adapt the PainCQ Survey to Arabic and measure the quality of pain care provided to Arab patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Design, Setting, and Patients

This study used an iterative, mixed-methods approach that employed cognitive interviews (a questioning technique), expert content analysis, and factor analysis to develop the Arabic Pain Care Quality (APainCQ) Survey. Arabic-speaking patients admitted to the oncology/hematology inpatient units with a minimum 24-hour stay were eligible for the study. Patients admitted between September and December 2021 were asked to participate in a cognitive interview to test the survey's relevance and clarity. Participants were chosen to provide heterogeneity in pain types, such as tumor-related, chemotherapy-related, postdiagnostic, and procedural pain. Informed consent was obtained from each patient before cognitive interviews and APainCQ data collection. The Dubai Scientific Research Ethical Committee reviewed the study. Institutional review board approval (ref: DREC-06/2020_07) was obtained before starting data collection.

Phase I: Content Validity

Ninety-six items from the original PainCQ study question bank were obtained from the last author of this paper, who was part of the team that developed the original tool. Three pain management experts in the United Arab Emirates narrowed the items to 26; 70 items were deleted for redundancy and lack of cultural relevance (Appendix Tables A1 and A2).

Phase II: Translation and Cultural Adaptation

The 26 items were translated and adapted into Arabic in three phases: initial translation, backward translation, and an expert committee validation.

Initial Translation (forward translation)

The survey was given to three bilingual health professional judges from Lebanon, Jordan, and Egypt to validate the translation and determine the survey's cultural appropriateness. Standard Arabic was the language used in this study since it is the official language of Arabic speakers' countries worldwide and on the basis of the fact that standard Arabic is widely taught, understood, and spoken by native Arabs.28 The professional judges determined that the revised questionnaire was culturally appropriate.

Backward Translation

The translated Arabic survey was then back-translated to English by two bilingual people independently following the recommended procedure for translating research instruments.29,30 In addition, the six Likert responses were written next to each scale item on a horizontal line to ease responses and reduce errors. The 6-point Likert scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

Expert Committee Review

The survey was next evaluated for clarity and readability of the items by five Arabic adults, including one person with a degree in translation and experience in proofreading, two nurses, and two lay persons who did not have a health care background, but one of them who had personal experience with pain. The final output comprised the 26-item APainCQ Survey, which was used for psychometric testing.

Phase III: Cognitive Interviewing

Cognitive interviewing, a questioning technique, assesses patient understanding and perception of questionnaire questions using the think-aloud method and verbal probing to produce comprehensible reports of patients' thoughts.31 Patients were each asked the following question for one survey item: (1) state the question in their own words and (2) provide feedback on how hard the question was to answer. In this phase, investigators also assessed whether patients with cancer could effectively evaluate pain management care by shift.

Phase IV: Data Collection Procedures

Demographic and Clinical Data

The demographic survey gathered variables such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, cancer diagnosis, admission reason, length of stay, pain type, and comorbidities.

Quality of Pain Management Survey Collection

Patients on the oncology unit were approached by a research team member who explained the purpose of the study, obtained informed consent, and requested each patient to complete the APainCQ Survey. Patients completed the survey on paper; surveys were then collected by two trained researchers who were not involved in the day-to-day care on the unit. A few patients requested that the survey be read to them, and the same research team members conducted this.

Statistical Analysis

A sample size estimation of 50-100 is shown to be adequate on the basis of recommendations in the literature on conducting exploratory factor analysis (EFA).32 Data from the paper surveys were entered into Microsoft Excel. Incomplete surveys were discarded. A double data entry process was implemented, in which all data were entered twice and compared with the original entry to ensure accuracy; the research team examined discrepancies. The data were then exported to SPSS 26 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) and R for analysis.

We conducted EFA with a principal axis factoring (PAF) with oblimin rotation to explore the factor structure or dimensionality of the surveys.33-35 PAF was chosen because it is the preferred method when analyzing common variance.33,34 We first assessed the mean, standard deviation, and range of each item, interitem correlation, and item-total correlation of each item in the health care team and nursing care surveys. Then, interitem correlations were examined according to the recommended range from 0.30 to 0.70.

In factor analysis, we began with using eigenvalue and scree plots to determine the number of factors to extract for both surveys. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett's test of sphericity were used for assessing sampling adequacy; KMO ≥0.8 and significant Bartlett's test indicate the suitability of the data for EFA; moreover, the determinant of correlation matrix must be above 0 to indicate that multicollinearity is not an issue for the data.34,36,37 A panel of experts, who were the authors of this study, reviewed the results of EFA and the content of each item. Items were removed if they met any of the following elimination criteria: loadings below 0.50, having a loading >0.3 on multiple factors, or conveying similar or unclear meanings. Item communalities were evaluated; items with communalities of 0.4 or above indicated that items fit well with the other items in their factor.38

The reliability of the final model of the health care team survey and nursing care survey was examined using Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega coefficients for internal consistency. A Cronbach's alpha of .70 was considered acceptable for a new tool.39,40

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 155 patients. The majority were male (62.6%) and married (66.5%), with a mean age of 43 years (standard deviation, 15.6). A description of the sample is included in Table 1. The clinical characteristic as cancer diagnosis of the sample is summarized in Table 1. Most patients (57%) reported at least one comorbidity, most commonly diabetes mellitus and hypertension. The day of hospitalization at the time of survey completion ranged from 1 to 66, with a mean of 17.5 days.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics

The iterative EFA process resulted in the sequential removal of three items. With an elbow point at factor 2 (eigenvalue = 0.35), the plot indicates that only the first factor explains significant variance in the health care team scale (Fig 1A). However, the scree plot of eigenvalues showed an elbow point between factor 2 (eigenvalue = 1.17) and factor 3 (eigenvalue = 0.84), indicating that the data may be best represented by two factors in the nurse scale (Fig 1B). This yielded a six-item one-factor solution for the health care team scale and a 17-item two-factor solution for the nurse scale on the basis of eigenvalues greater than one and the scree plot.

FIG 1.

Scree plots of APainCQ. (A) Scree plot of health care team scale. (B) Scree plot of nurse scale. APainCQ, Arabic Pain Care Quality.

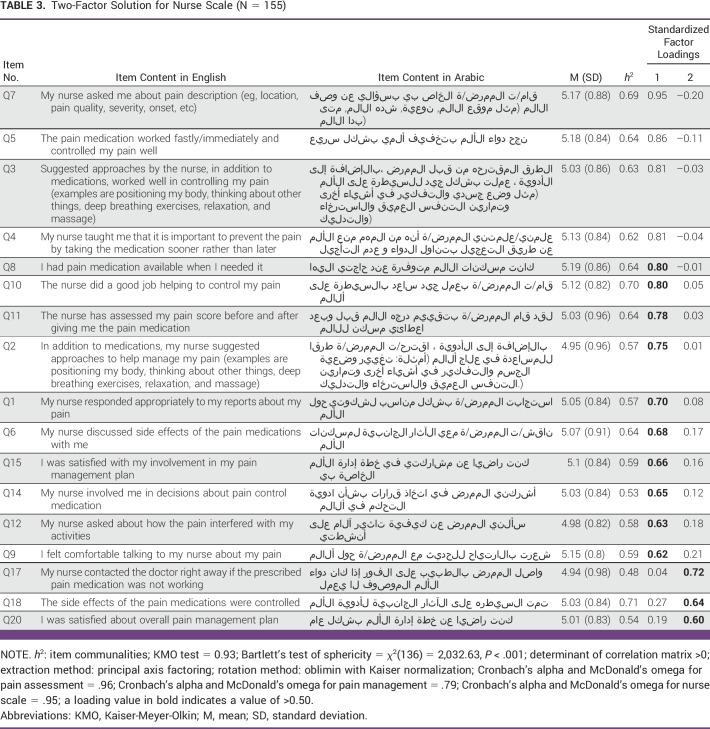

The results of the significant Bartlett test (P < .001) of sphericity and KMO test of 0.93 for both the health care team scale (Table 2) and the nurse scale (Table 3) suggested that the data were suitable for factor analysis. The total variance explained was 76.17% for the health care team scale and 60.91% for the nurse scale, which explained 56.51% for factor 1 with 14 items and 4.40% for factor 2. On the basis of the item meaning, the two factors were named pain management for factor 1 and pain assessment for factor 2. Item communalities ranged from 0.66 to 0.78 on the health care team scale for factor 1, and were from 0.48 to 0.71 for factor 2; this indicated that no problematic items in APainCQ and all the items were found to contribute to their factors.

TABLE 2.

Single-Factor Solution for Health Care Team Scale (N = 155)

TABLE 3.

Two-Factor Solution for Nurse Scale (N = 155)

Regarding internal consistency reliability, Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega for the health care team scale and nurse scale were high; both values were .95. Internal consistency reliability of pain assessment and pain management subscales of nurse scales were also high, with values of 0.96 and 0.79, respectively (Table 3). Moreover, there was a moderate correlation (r = 0.66; P < .001) between the two subscales in the nurse scale.

DISCUSSION

This research study aimed to develop a short and meaningful tool to examine the pain care quality in Arabic-speaking patients and is the first patient-reported pain care quality tool to our knowledge to be developed and tested in this population.

Patient-centered care has been a focus in the health care system, and patients' needs are considered in decision making.41 Therefore, patients' perception of care becomes integral in developing questionnaires for quality improvement purposes. The level of patient satisfaction depends not only on the effectiveness of pain relief but also on the care from the health care providers. An opportunity to participate in pain treatment and gain better knowledge about pain care may contribute to higher patient satisfaction.42 Unfortunately, well-developed and validated patient satisfaction questionnaires that may be used in clinical trials and survey research are in short supply. With few exceptions, there is a lack of rigor in the development of satisfaction questionnaires, and the measurement of treatment satisfaction has been characterized as poor.42,43

This study presents the results of a methodologically rigorous process to develop and validate a questionnaire specifically for cancer pain. The need to collect data on patient satisfaction with drug treatment, bother of side effects, patient satisfaction with the information provided and method of administration, and patient satisfaction with treatment outcomes is imperative—the revised American Pain Society Outcome Questionnaire.44 It measures satisfaction with pain treatment but excludes other comprehensive aspects such as nurse/health care team interactions and the patient's opportunity to be a part of the decision making in their care plan. The APainCQ addresses all these components. Patient satisfaction assessments are valuable for many reasons. First, satisfaction with treatment and care is related to adherence to clinician instructions, which is an essential determinant of health outcomes.45 Second, patient satisfaction assessments add another dimension to understanding patient outcomes. Although they are not objective and do not correspond directly to clinician assessments, the information captured goes beyond health care rating or health status.46 Third, patient feedback may be used to alter and improve the quality of health care delivery.45

The work described was focused primarily on steps to establish the validity and factor structure of the APainCQ. Survey development included item generation, expert judgment, and a systematic evaluation of items evaluated by hospitalized patients using the cognitive interviewing method. Insight into patient thought processes and conceptualization of pain and pain management helped to improve the wording and presentation of the questions in the survey. This methodology supports the validity of the APainCQ. Another set of hospitalized patients then scored the items to examine factor structure and reliability. These patients were hospitalized for various cancer-related reasons and had varying types and sites of pain. The APainCQ (consisting of 23 items) that resulted from this foundational work is undergoing psychometric testing in a multisite study. Testing the tool in other hospitalized patients will expand the generalizability.

The APainCQ may be used in randomized controlled trials, postmarketing surveillance research, or observational and survey studies. The APainCQ, suitable for individual patients and assessment in groups of pain sufferers, may also be used for its separate subscales or as an entire instrument. Additional testing of this modular approach is currently underway.

At a national level, performance measures such as the APainCQ can be helpful to benchmark and improve performance and could be integrated into the indicators adopted by national organizations. Finally, as a research tool, the APainCQ provides a method to link nursing care measures and patient outcomes directly during a shift of care while assessing interdisciplinary care overall. Using patient-reported pain experience measures will also encourage patient engagement in their pain care. This approach enhances methods available to examine the relationship between nursing and interdisciplinary care and patient outcomes, and can improve understanding of how the health care team can make a difference in the lives of individuals with pain.

The study has strengths and limitations to consider when interpreting the findings. The major strength is providing a valuable tool to provide baseline data on cancer pain management satisfaction and quality of care among Arab-speaking adult patients with cancer, which was not available before. In addition, the study adds to the growing international literature on the quality indicator of cancer pain management.

The study has some limitations. A convenience sample of patients with cancer was used in a single setting. This setting is a large center where significant emphasis is placed on pain management, including educating patients about the benefits of using analgesics to treat their pain and the minimal risks involved. It is, therefore, essential to use the APainCQ in other samples to increase generalizability. Although there was representation from both older and less-educated people, racial minorities were not represented, and they should be a target in future testing of the tool.

In conclusion, the psychometric testing of a measurement instrument is vital to support its use in research or clinical practice. This study has demonstrated the final construction of a valid and reliable Arabic version of the PainCQ and supports the APainCQ as a quality indicator tool for pain management evaluation in this setting. The validity of this tool can pave the way for large-scale studies in Arab-speaking countries. This validated questionnaire can be used as a standard tool to benchmark pain management quality within the measured patient cohort. Different questionnaire subscales allow clinicians or researchers to identify areas for improvement more effectively.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Opinions About Your Health Care Team (six questions)

TABLE A2.

Opinions About Your Nurse (total 17 questions; six for assessment and 11 for management)

Jia-Wen Guo

Research Funding: Hitachi

Jeannine M. Brant

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Carevive Systems

Honoraria: Daiichi Sankyo/Astra Zeneca

Speakers' Bureau: Daiichi Sankyo

Research Funding: Fuld (Inst), Daisy (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Elsevier royalties—book editor

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Nijmeh Al-Atiyyat, Nezar Ahmed Salim, Jeannine M. Brant

Collection and assembly of data: Nezar Ahmed Salim, Jia-Wen Guo, Mohammed Toffaha

Data analysis and interpretation: Nijmeh Al-Atiyyat, Nezar Ahmed Salim, Jia-Wen Guo, Jeannine M. Brant

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Jia-Wen Guo

Research Funding: Hitachi

Jeannine M. Brant

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Carevive Systems

Honoraria: Daiichi Sankyo/Astra Zeneca

Speakers' Bureau: Daiichi Sankyo

Research Funding: Fuld (Inst), Daisy (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Elsevier royalties—book editor

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer World health statistics 2022: Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals, 2022.

- 2. Chen S, Cao Z, Prettner K, et al. Estimates and projections of the global economic cost of 29 cancers in 204 countries and territories from 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9:465–472. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jan F, Singh M, Syed NA, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive restructuring on intensity of pain in cancer patients: A pilot study in oncology department of tertiary care hospital. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2022;23:2035–2047. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2022.23.6.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marinangeli F, Saetta A, Lugini A. Current management of cancer pain in Italy: Expert opinion paper. Open Med. 2022;17:34–45. doi: 10.1515/med-2021-0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gallaway MS, Townsend JS, Shelby D, et al. Pain among cancer survivors. Preventing Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E54. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.190367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, Hochstenbach LM, Joosten EA, et al. Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51:1070–1090.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Su WC, Chuang CH, Chen FM, et al. Effects of Good Pain Management (GPM) ward program on patterns of care and pain control in patients with cancer pain in Taiwan. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:1903–1911. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05656-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cluxton C. The challenge of cancer pain assessment. Ulster Med J. 2019;88:43–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glare P, Aubrey K, Gulati A, et al. Pharmacologic management of persistent pain in cancer survivors. Drugs. 2022;82:275–291. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01675-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative Geneva, Switzerland: OECD Publishing; 2018. 10.1787/9789264300309-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Al-Sayaghi KM, Fadlalmola HA, Aljohani WA, et al. Nurses' knowledge and attitudes regarding pain assessment and management in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare. 2022;10:528. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10030528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beck SL, Dunton N, Berry PH, et al. Dissemination and implementation of patient-centered indicators of pain care quality and outcomes. Med Care. 2019;57:159–166. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trosdorf M, Brédart A. Kassianos AP (ed): Handbook of Quality of Life in Cancer. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. Satisfaction with cancer care; pp. 235–249. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Institute of Medicine . To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McEwan M, Wills EM. Theoretical Basis for Nursing. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haley M.2022. Patient satisfaction/patient experience, patient-reported outcomes, and healthcare quality: Are we focusing on the wrong metrics? [doctoral dissertation]. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, University of Pittsburgh.

- 17. Fix GM, VanDeusen Lukas C, Bolton RE, et al. Patient-centred care is a way of doing things: How healthcare employees conceptualize patient-centred care. Health Expect. 2018;21:300–307. doi: 10.1111/hex.12615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beck SL, Towsley GL, Berry PH, et al. Measuring the quality of care related to pain management: A multiple-method approach to instrument development. Nurs Res. 2010;59:85–92. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181d1a732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quentin W, Partanen VM, Brownwood I, et al. Measuring Healthcare Quality. Improving Healthcare Quality in Europe. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO; 2019. p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pett MA, Beck SL, Guo JW, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Pain Care Quality Surveys (PainCQ©) Health Serv Res. 2013;48:1018–1038. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beck SL, Towsley GL, Pett MA, et al. Initial psychometric properties of the Pain Care Quality Survey (PainCQ) J Pain. 2010;11:1311–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beck SL, Brant JM, Donohue R, et al. Oncology nursing certification: Relation to nurses’ knowledge and attitudes about pain, patientreported pain care quality, and pain outcomes. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2016;43:67–76. doi: 10.1188/16.ONF.67-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rice KL, Castex J, Redmond M, et al. Bundling Interventions to Enhance Pain Care Quality (BITE Pain) in medical surgical patients. Ochsner J. 2019;19:77–95. doi: 10.31486/toj.18.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guo JW, Chiang HY, Beck SL. Cross-cultural translation of the nChinese version of Pain Care Quality Surveys (C-PainCQ) Asian Pac Isl Nurs J. 2020;4:165–172. doi: 10.31372/20190404.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Al-Atiyyat N, Salim NA, Tuffaha MG, et al. A survey of the knowledge and attitudes of oncology nurses toward pain in United Arab Emirates oncology settings. Pain Manage Nurs. 2019;20:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Salim NA, Tuffaha MG, Brant JM. Impact of a pain management program on nurses' knowledge and attitude toward pain in United Arab Emirates: Experimental-four Solomon group design. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;54:151314. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alhalal E, Jackson KT. Evaluation of the Arabic version of the Chronic Pain Grade scale: Psychometric properties. Res Nurs Health. 2021;44:403–412. doi: 10.1002/nur.22116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wolsey TD, Karkouti IM, Hiebert EH, et al. Texts for reading instruction and the most common words in modern standard Arabic: An investigation. Read Writ. 2022;36:1567–1587. [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization http://www.who.int/substanceabuse/researchtools/translation/en/ Process of translation and adaptation of instruments, 2009.

- 30. Cheung H, Mazerolle L, Possingham HP, et al. A methodological guide for translating study instruments in cross-cultural research: Adapting the ‘connectedness to nature’ scale into Chinese. Methods Ecol Evol. 2020;11:1379–1387. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Story DA, Tait AR. Survey research. Anesthesiology. 2019;130:192–202. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sapnas KG, Zeller RA. Minimizing sample size when using exploratory factor analysis for measurement. J Nurs Meas. 2002;10:135–154. doi: 10.1891/jnum.10.2.135.52552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Winter JCF, Dodou D. Factor recovery by principal axis factoring and maximum likelihood factor analysis as a function of factor pattern and sample size. J Appl Stat. 2012;39:695–710. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pett MA, Lackey NR, Sullivan JJ. Making Sense of Factor Analysis: The Use of Factor Analysis for Instrument Development in Health Care Research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goretzko D, Pham TTH, Bühner M. Exploratory factor analysis: Current use, methodological developments and recommendations for good practice. Curr Psychol. 2021;40:3510–3521. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. ed 6. Boston, Massachusetts: Pearson; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Field A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. ed 5. London, United Kingdom: Sage; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Costello AB, Osborne J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2005;10:7. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53–55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dunn TJ, Baguley T, Brunsden V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br J Psychol. 2014;105:399–412. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reuben DB, Jennings LA. Putting goal‐oriented patient care into practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:1342–1344. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organization https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/279700/9789241550390-eng.pdf WHO guidelines for the pharmacological and radiotherapeutic management of cancer pain in adults and adolescents, 2018. [PubMed]

- 43. Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Ball J, et al. Patient satisfaction with hospital care and nurses in England: An observational study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019189. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McNeill JA, Sherwood GD, Starck PL, et al. Assessing clinical outcomes: Patient satisfaction with pain management. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1998;16:29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zaid AA, Arqawi SM, Mwais RMA, et al. The impact of total quality management and perceived service quality on patient satisfaction and behavior intention in Palestinian healthcare organizations. Technol Rep Kansai Univ. 2020;62:221–232. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Podder V, Lew V, Ghassemzadeh S. SOAP Notes. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]