Abstract

Picture in online customer reviews conveys detailed product information to help potential customers make purchase decisions, which is an important form of digital data. Therefore, understanding the predictors of picture sharing in online customer reviews is crucial for retail businesses to achieve digital transformation strategies for competitive advantage, high quality service and sustainable performance. By analyzing 6211 online customer reviews of 16 products crawled from the famous online shopping site JD.com in China, this study tests the effects of reviewer rank (who), product type (what), time interval (when), review device (where), consumption satisfaction (why), and the level of involvement (how) on whether customers sharing picture and picture count in online customer reviews based on the 5W1H analysis framework. The results show that: (1) with or without picture and picture count both influence the helpfulness of online customer reviews; (2) product type, time interval, review device, consumption satisfaction and the level of involvement significantly affect whether consumers share picture; and (3) review device, consumption satisfaction and the level of involvement significantly affect picture count. The findings can help managers manage picture reviews to improve business performance.

Keywords: 5W1H, Helpfulness, Online consumer review, Picture, Picture count, Digital data

1. Introduction

With the development of online communication technology, picture information is shared as well as text information in online consumer reviews (OCRs). According to the dual coding theory, pictures are likely to be coded both visually and verbally, resulting in them being easy to recognize and retain [[1], [2], [3]]. Pictures in OCRs capture the details of product, which afford tangible reference points to potential customers to help them assess product benefits and reduce uncertainty [4,5]. As the old saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words. Therefore, picture in OCRs is an important form of digital data for retail businesses. Most popular online shopping and online review websites, such as Amazon.com, TripAdvisor.com and Yelp.com in America, and JD.com, Taobao.com and Dianping.com in China, encourage post-purchase consumers to share pictures in their reviews [6]. Some studies investigate the effect of picture in OCRs on consumer response [3,4,[7], [8], [9], [10]]. It is generally accepted that picture in OCRs plays a positive role in influencing consumers’ perception and purchase decisions, which appeals to managers to promote picture sharing with appropriate marketing activities [9]. Therefore, understanding the predictors of picture sharing in OCRs is crucial for retail businesses to achieve digital transformation strategies for competitive advantage, high quality service and sustainable performance.

A small stream of research has investigated the role of picture sharing in OCRs [4,[8], [9], [10]]. However, knowledge about the predictors that influence picture sharing in OCRs is scarce. The decision to share pictures includes two phases: the first is to decide whether to share picture in reviews; if the answer is yes, then the second is to decide how many pictures to share. As the 5W1H analysis framework can be used to categorize a variety of information and interpret the contexts of objects [11], this work aims to investigate the predictors of whether consumers will share picture and picture count in OCRs based on the 5W1H framework. The results show that product type, time interval, review device, consumption satisfaction and the level of involvement significantly affect whether consumers will share picture, and review device, consumption satisfaction and the level of involvement significantly affect picture count.

This work has important theoretical and practical implications. To the best of our knowledge, it is one of the first to systematically investigate the determinants of picture sharing in OCRs by analyzing real online reviews, which complements the research on graphical reviews in the online review literature. In addition, this work is the first study to distinguish between with or without picture and picture count and reveals the differences in the predictors between whether consumers will share picture and picture count, which provides insight into the acquisition of picture superiority effect. Moreover, this work finds several differences between sharing pictures and textual content, which complements the knowledge sharing theory literature. The findings can help managers manage picture reviews to improve business performance.

The remainder of this work is organized as follows. The following section introduces relevant literature on picture superiority effect and the 5W1H framework, followed by an outline of the data collection and measurement methods. Subsequently, the research results and discussion are presented. Finally, the theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and future research directions are provided.

2. Literature review and hypotheses

2.1. Picture superiority

Dual coding theory suggests that individuals encode and store information in memory using two separate mental codes: the verbal code for processing linguistic information and the nonverbal code for processing non-linguistic (visual) information [1]. Textual and visual product information are typically provided to assist consumers in evaluating online products [12]. According to dual coding theory, pictures stimuli are more likely to be coded visually and verbally, while words are less likely to be coded visually. The dual coding of pictures makes them easier to be recognized and retained than words, resulting in the picture superiority effect [[1], [2], [3]].

Given that the superiority of picture, a small stream of research has investigated the role of picture sharing in OCRs. Most studies focus on the effect of with or without picture on consumer response. These studies all support the positive effect of picture, such as increasing shopping efficiency and effectiveness when consumers are familiar with the product items [13], enhancing review quality, credibility, usefulness, helpfulness [4,9,10,14,15], increasing trust and product sales [8,[16], [17], [18], [19]]. A few studies investigate the effect of picture count on consumer response and also support its positive effect, including increasing review usefulness and enjoyment [3,15], and purchase intention [20]. In addition, a few scattered studies explore the effect of picture type (process-focused vs. outcome-focused) and sentiment on consumer response [21,22]. As these previous studies have demonstrated the value of picture in OCRs, a few studies have begun to pay attention to the predictors of picture sharing. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one study focusing on the predictors of whether consumers will share picture [23] and one study focusing on the predictors of picture count [24]. The predictors in these two studies mainly focus on travel distance, travel experience and traveler status by analyzing online travel reviews. Generally, knowledge about the predictors of picture sharing in OCRs is scarce. Table 1 lists the recent literature related to picture in OCRs.

Table 1.

Recent literature related to picture in OCRs.

| Source |

Research object |

Research content |

Data source | Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Picture | Picture count | Predictor | Outcome | |||

| [10,15] | ✓ | ✓ | Experiment | OCRs accompanied by pictures are more helpful than word-only reviews. | ||

| [4] | ✓ | ✓ | Experiment | High-risk averse travelers feel travel product picture enhances usefulness of the positive online reviews. | ||

| [8,16] | ✓ | ✓ | Amazon | Picture in OCRs influences product sale. | ||

| [9] | ✓ | ✓ | Survey | Potential consumers value the pictures of food and physical evidences of restaurants in OCRs. | ||

| [17,18] | ✓ | ✓ | Experiment | Reviews containing a picture can increase trust and purchase intention. | ||

| [19] | ✓ | ✓ | experiment | Pictures affect tourists' intention and decision to visit a destination and its attractions. | ||

| [21] | ✓ | ✓ | Online restaurant reviews | Picture sentiment has a U-shaped relationship with review usefulness, and positively affects review enjoyment. | ||

| [22] | ✓ | ✓ | Experiment | OCRs with process-focused (vs. outcome-focused) food pictures lead to stronger purchase intention. | ||

| [25] | ✓ | ✓ | Experiment | Consumers make inferences about the reviewers' socioeconomic status (SES) from the background of online review pictures, which affect purchase intention. | ||

| [7] | ✓ | ✓ | Online restaurant reviews | Readers feel online reviews with larger image count more practical and useful. | ||

| [3] | ✓ | ✓ | Online restaurant reviews | The number of food and beverage images positively affects review enjoyment and review usefulness. | ||

| [20] | ✓ | ✓ | Online restaurant reviews | Pictures count positive affects the number of visitors. | ||

| [24] | ✓ | ✓ | Online restaurant reviews | Travel distance and travel experience positively affect picture count in OCRs. | ||

| [23] | ✓ | ✓ | Online travel reviews | Trip distance has a positive effect and traveler status has a negative effect on the inclination to share photos. | ||

| This study | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Online shopping reviews | (1) With or without picture and picture count both influence the helpfulness of OCRs; (2) Product type, time interval, review device, consumption satisfaction and the level of involvement significantly affect whether consumers sharing picture; And (3) review device, consumption satisfaction and the level of involvement significantly affect picture count. | |

2.2. 5W1H framework

The 5W1H framework, also known as the Kipling Method, is a method of questioning and problem solving that answers all the essential elements in a problem, namely what, who, when, where, why and how, to enable a comprehensive analysis of the problem. This framework can be used when gathering information and investigating a problem by categorizing a variety of information and interpret the contexts of objects [11]. It can also be used to explore the causality behind a particular problem, identifying a problem by analyzing all dimensions from different perspectives.

To gain insight into the predictors of picture sharing in OCRs, the six essential elements included in the 5W1H framework can help us to conduct a comprehensive and systematic analysis of these predictors from various perspectives. Therefore, the current study employs this framework to categorize the predictors of picture sharing in OCRs.

2.3. The predictors of picture sharing in OCRs

2.3.1. Reviewer rank

Previous study shows that the status characteristics of online reviewers have an impact on their review behaviors [26]. Incentive hierarchies are commonly employed by online platforms to motivate users to contribute by awarding them increasingly higher status on the platform after achieving more and more difficult goals [27,28]. The status ranks that users obtain are prominently displayed on their public profile, serving as symbols of their status in the community [29]. As reviewers are the people who share pictures in OCRs and their rank status in incentive hierarchies describes their status characteristics, reviewer rank is used to investigate the ‘who’ in the 5W1H analysis framework in this work.

Schuckert et al. suggest that reviewers with a high-level badge tend to post reviews in a cautious and objective manner than those with a lower status, because they are aware that their reviews will influence more readers [25]. Compared with textual reviews, which often include private opinions, the information conveyed by a picture is more objective. Therefore, it is expected that reviewers with a higher status would be more likely to upload picture and upload more pictures in OCRs than those with a lower status. Hence, this work proposes the following hypotheses.

H1a

Reviewers with a higher status rank are more likely to share picture in OCRs.

H1b

Reviewers with a higher status rank are more likely to share more pictures in OCRs.

2.3.2. Product type

The product purchased by reviewers is the evaluation object in OCRs. Products can be classified into search products and experience products [30]. Search products are those products whose information on product quality is relatively easy to obtain before purchasing, and whose key attributes are objective and easy to compare. Experience products are those products whose information on product quality is relatively difficult and costly to obtain before purchasing, and those key attributes are subjective or difficult to compare [31,32]. Previous research has showed that product type influences the content and star rating that consumers share in online reviews: the word count of search products is fewer than that of experience products and the star rating of search products is lower than that of experience products [32]. As product type (search/experience product) is an important product characteristic related to the online review behavior of consumers, it is employed to investigate the ‘what’ in the 5W1H framework in this work.

Search products and experience products differ in the role of product attributes in judging the quality of products before purchasing [31,32]. Pictures are highly concrete [33], which include many special product attributes. As product attributes are more useful in helping readers evaluate the quality of search products than of experience products [34], consumers may be more likely to share picture and share more pictures when they review search products online. In addition, although the picture of usage experience of some experience products can afford useful direct experience to help readers evaluate product quality (e.g., a garment displayed by a buyer), the risk of personal information exposure may prevent many consumers from uploading pictures online. Therefore, this work proposes the following.

H2a

Reviewers are more likely to share picture of search products than that of experience products in OCRs.

H2b

Reviewers are more likely to share more pictures of search products than that of experience products in OCRs.

2.3.3. Time interval

Reviewers have the right to choose time to share online reviews during the given time frame. Time interval is used to describe the number of days between the purchase date and the day when the review is posted [28,35]. As the time interval is related to the duration of experience with the products, previous studies suggest that it is an important review characteristic [28,35]. Hence, it is employed to investigate the ‘when’ in the 5W1H framework in this work.

Construal level theory suggests that people tend to represent distance events (e.g., those that occurred in the past) in high-level terms of abstract features; whereas they are more likely to represent near events (e.g., those that just occurred) in low-level terms of concrete features [36,37]. Huang et al. demonstrate that time interval amplifies consumers’ high-level construal of textual OCRs [38]. Hence, consumers may use high-level and abstract construal when they review a consumption experience with a long delay; whereas they may use low-level and concrete construal when they review a consumption experience promptly. As pictures are highly concrete [33], consumers may be less likely to share picture when they use high-level and abstract construal. Therefore, this work proposes that consumers are less likely to share picture in OCRs when the time interval is longer. Even if they choose to share picture, the number of pictures may be fewer when the time interval is longer. The hypotheses are proposed as follows.

H3a

Reviewers are less likely to share picture in OCRs with a longer time interval.

H3b

Reviewers are less likely to share more pictures in OCRs with a longer time interval.

2.3.4. Review device

Sharing picture online requires the use of an information input device. With the development of the mobile Internet, both stationary PCs and mobile devices, such as smartphones and tablet computers, can be used to share online reviews [39]. There are significant differences in screen size, function, and usage context between PCs and mobile devices [40,41]. Previous studies show that the review device influences the content and star rating consumers shared in OCRs: the word count of OCRs submitted via mobile devices is shorter than via PCs [39,42]; the star rating submitted via mobile devices is higher than via PCs [42,43]. As the review device is an important factor related to the online review behavior of consumers, it is employed to investigate the ‘where’ in the 5W1H framework in this work.

Mobile devices are more portable and more flexible than PCs in terms of usage time and space [40,41]. Consumers can use mobile devices to take and then upload product pictures online at anytime, anywhere after receiving the goods [44]. However, the convenience in taking and uploading photos is lower when consumers use PCs to share product pictures online. Typically, they need to first take pictures and then upload the pictures to their PCs. The lower convenience in taking and uploading picture may impede consumers sharing picture in online reviews. Therefore, this work proposes that consumers are more likely to share picture and share more pictures in OCRs when they submit reviews via a mobile device than via a PC. The hypotheses are proposed as follows.

H4a

Reviewers are more likely to share picture in OCRs when they submit reviews from a mobile device than from a PC.

H4b

Reviewers are more likely to share more pictures in OCRs when they submit reviews from a mobile device than from a PC.

2.3.5. Consumption satisfaction

The attitude of consumers toward the purchased product affects their enthusiasm and motivation to post online reviews [35,45]. Consumption satisfaction manifests the attitude of consumers toward the product they purchased. Hence, consumption satisfaction is related to why consumers post reviews online. Sharing picture is a part of posting online reviews. Hence, consumption satisfaction is used to investigate the ‘why’ in the 5W1H framework in this work.

Ma et al. (2013) suggest that consumers write a long negative review to vent their frustrations, to retaliate against the seller, or to benefit others when they are not satisfied with their consumption experience [35]. In this case, consumers may also upload pictures to support their negative attitude. Similarly, when their consumption satisfaction is high, they may upload product pictures to support their positive attitude and reflect that they made a right decision in online reviews. Hence, this work proposes that when the consumption satisfaction is more polarity, reviewers are more likely to share picture and share more pictures in OCRs. The hypotheses are as follows.

H5a

Reviewers are more likely to share picture in OCRs when their consumption satisfaction is more polarity.

H5b

Reviewers are more likely to share more pictures in OCRs when their consumption satisfaction is more polarity.

2.3.6. The level of involvement

Reviewers who have a higher involvement in posting online review will devote more energy and time to contribute a more detailed review. Hence, the involvement level of reviewers reflects how they treat posting online reviews. Sharing picture is a part of posting online reviews. Hence, the level of involvement is used to investigate the ‘how’ in the 5W1H framework in this work.

Pan and Zhang find that the more involved a reviewer is, the more quality information will be reported to support other consumers' purchase decisions [34]. Besides textual OCRs, pictures are useful quality information to help others’ purchase decisions [4]. Hence, this work proposes that when the involvement level of reviewers in posting online review is higher, they are more likely to share picture and share more pictures. The hypotheses are as follows.

H6a

Reviewers are more likely to share picture in OCRs when their involvement level is higher.

H6b

Reviewers are more likely to share more pictures in OCRs when their involvement level is higher.

2.4. The helpfulness of OCRs with picture

Customers tend to seek visual information when making purchase decisions because it provides additional product information [7,8]. Picture in OCRs affords tangible reference points to help readers assess product benefits and reduce uncertainty [4,5]. Several studies have demonstrated that picture can improve the helpfulness of OCRs. For example, Yoon finds that customers judge e-WOM arguments presented with both text and pictures more effective than those presented with text-only [10]. Wu et al. show that verbal reviews accompanied by pictures are more helpful than word-only reviews [15]. Casaló et al. find that positive online reviews with travel product pictures can enhance the usefulness perception of high-risk averse travelers [4]. Based on the picture superiority effect [[1], [2], [3]], this study proposes that picture can increase the helpfulness of OCRs. The hypothesis is as follows.

H7a

OCRs with picture are more helpful than those without picture.

By analyzing online restaurant reviews, previous studies demonstrate the value of picture count to the helpfulness of OCRs. For example, Cheng and Ho find that readers feel reviews with a larger image count to be more practical and useful by analyzing online restaurant reviews [7]. Yang et al. find that the number of food and beverage images positively affects the usefulness of online restaurant reviews [3]. Mohring et al. show that pictures count positive affects the number of visitors [20]. Similarly, this study proposes that picture count can increase the helpfulness of OCRs. The hypothesis is as follows.

H7b

OCRs with more picture count are more helpful.

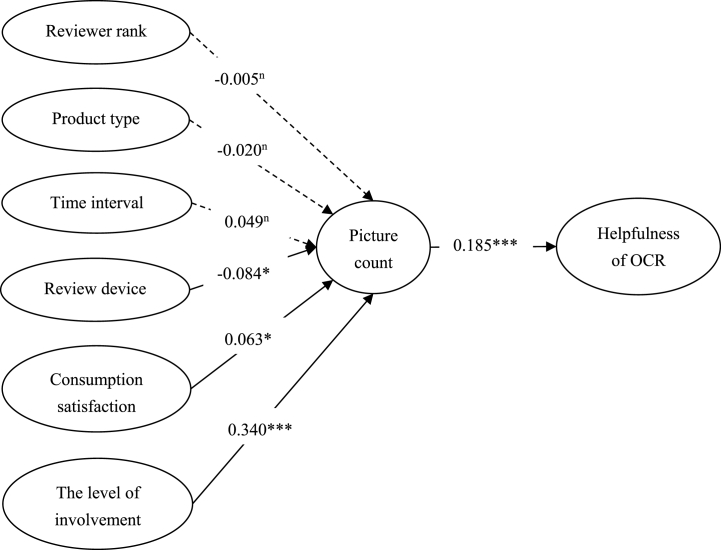

Fig. 1 shows the research model.

Fig. 1.

The research model.

3. Methods

3.1. Data collection

Actual review data reflect consumer experiences in natura without any interference from researchers [7,46,47]. The two existing articles investigating the predictors of picture sharing also used real OCRs (online restaurant reviews) as their data source [23,24]. Thus, this work adopts actual review data to perform empirical analysis. The data were crawled from JD.com during August 2017, the largest self-operated B2C e-commerce business in China. The reason we used OCRs collected in 2017 is that OCRs on JD.com at that time displayed the information of all the variables we investigated, but now the page no longer displays the information of review device and reviewer rank. Although not the latest data, since online shopping has not undergone disruptive changes in recent years, and this work examines causal relationships rather than absolute differences, we believe that the data is still representative in the current scenario. Sixteen products were selected as the source of sample data, consisting of eight search products (smartphone, memory card, router, television, computer, webcam, earphone, digital camera) and eight experience products (bottled water, milk, fresh fruit, down jacket, music album, book, perfume, skin care). The selection of search products and experience products is based on previous studies and a pre-test conducted with 30 undergraduates. Price was also a major factor when sampling, with half of the products being high-priced and half low-priced.

About 3500 reviews of each product were crawled. Each review consisted of reviewer's ID, reviewer rank, information input device, product name, star rating, purchase time, review time, textual review, picture count, and the number of helpfulness votes. The total number of reviews of the sixteen products was 55,161. However, due to the prevalence of smartphones, the number of reviews from mobile devices is far more than that from PCs. By referring to the study of Zhu et al. [42], we conducted further sample extraction to maintain a relatively balanced volume of review data from mobile devices and PCs. The reviews were sorted by purchase time and then two adjacent reviews, one from a mobile device and the other from a PC, were paired and extracted. Finally, 10,066 OCRs were extracted. In addition, JD.com have three types of members: ordinary members, plus members (i.e., charge members), and corporate members. The ordinary members make up the majority of the members and only they are subject to a status rank management strategy. As reviewer rank is an independent variable in this work, we deleted the reviews from plus members and corporate members who have no reviewer rank information. The final samples for analysis comprised 6211 reviews.

3.2. Measures

Nine variables are investigated in this work: helpfulness of OCR, picture, picture count, reviewer rank, product type, time interval, review device, consumption satisfaction and the level of involvement.

Helpfulness of OCR refers to how many readers vote for the helpfulness of an online review. It is a nonnegative integer variable. Picture refers to whether there is at least one picture shared in an online review. It is a binary variable. Picture count refers to the number of pictures shared in an online review. It is a continuous variable, which ranges from 1 to 10 in this work.

Reviewer rank refers to the status characteristic of reviewer in incentive hierarchies. JD.com classifies consumers into 5 grades: the first level is iron, the following levels are bronze, silver, gold, and diamonds. The rank is determined by growth value, which is obtained by logging in, shopping and reviewing, and the higher the growth value, the higher the rank level. The 5 grades are employed as the values of reviewer rank.

Product type refers to whether product quality information is relatively easy to obtain before purchasing and key attributes are objective and easy to compare. Two types of product are distinguished, one is an experience product, and the other is a search product.

Time interval refers to the number of days between the purchase day and review posting day, which is a continuous variable. To take log of days, we take the starting point that purchase and posting review happen on the same day as ‘1’ day. In the end, the day ranges from 1 to 190. To smooth skewed distributions [48], this work uses the logarithmic values by refer to Cheng and Ho [7].

Review device refers to the device consumers used to share pictures. Two types of device are distinguished, one is PC with low convenience in sharing pictures, and the other is mobile device with high convenience in sharing pictures.

Consumption satisfaction refers to the attitude of consumers toward the product they purchased. As previous studies show that the numerical star rating of online reviews reflects reviewer attitude [32,35], the star rating is employed to test the consumption satisfaction of consumers. Numerical star ratings for OCRs typically range from one to five stars. A one-star rating indicates an extremely negative attitude of the product and a five-star rating reflects an extremely positive attitude of the product [32]. According to Mudambi and Schuff, one-star and five-star rating are regarded as the most polar consumption satisfaction, two-star and four-star rating are regarded as the less polar consumption satisfaction and three-star rating are regarded as the neutral consumption satisfaction [32].

The level of involvement refers to the amount of energy and time consumers devote to share an online review. Review length (also known as ‘review depth’, ‘review elaborateness’) is commonly used to describe the detail level of OCRs [35], which reflects the involvement level of reviewers [3,34]. Consumers who write longer reviews exert more time and effort to report their consumption experience [28]. Ma et al. suggest that review length is indicative of a reviewer's state of mind [35], which represents the elaborateness of the reviewer. According to cognitive consistency theory [49,50], reviewers who write a long review may be likely to exert time and effort to share pictures as well to support their attitude and others' purchase decisions. Hence, review length is employed to test the level of involvement. It is measured by the word count of the review based on the study of Mudambi and Schuff [32]. Word count is a continuous variable, which ranges from 1 to 911 in this work. To smooth skewed distributions [48], this work uses the logarithmic values for word count by referring to Cheng and Ho [7].

Table 2 shows the description, metric, and source of each variable.

Table 2.

The measurement of variables.

| Variable | Description | Metric | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reviewer rank | The level of reviewer status on JD.com. | Nonnegative integer, 1-5 | [28] |

| Product type | A binary variable that classifies products into experience and search products. | 0 = experience product, 1 = search product | [32] |

| Time interval | Number of days between the purchase day and review posting day. | Logarithm of the number of time interval, nonnegative number | [28] |

| Review device | A binary variable that shows the review input device is a PC or a mobile device. | 0 = PC, 1 = mobile device | [39] |

| Consumption satisfaction | The polarity of numerical star rating of the review. | Nonnegative integer, 3 = one-star and five-star rating, 2 = two-star and four-star rating, and 1 = three-star rating. | [32] |

| The level of involvement | Total number of words of the textual review | Logarithm of word count, nonnegative number | [32] |

| Picture | A binary variable that measures whether a consumer uploaded any picture in his or her online review. | 0 = the review without picture, 1 = the review with picture | [4] |

| Picture count | Total number of pictures in the review. | Integer, greater than 0 | [7] |

| Helpfulness of OCR | Total number of helpfulness votes the review received. | Nonnegative integer | [28] |

4. Results

The statistical software SPSS 22.0 is used to test the hypotheses with two steps. First, the 6211 samples are used to test H1a-H7a. Second, by referring to the study of Cheng and Ho [7], 821 reviews which include at least one picture are selected from the 6211 samples to test H1b-H7b.

4.1. Predictors, with or without picture, and helpfulness of OCRs

4.1.1. Descriptive statistics

The section aims to test the effect of with or without picture on the helpfulness of OCRs and the effect of reviewer rank, product type, time interval, review device, consumption satisfaction, and the level of involvement on with or without picture in OCRs. Table 3 provides the descriptive statistics of the 6211 samples.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for picture context (n = 6211).

| Variable | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reviewer rank | 1 | 5 | 3.78 | 1.146 |

| Product type | 0 | 1 | 0.57 | 0.494 |

| Time interval (In) | 0.000 | 5.247 | 2.399 | 1.230 |

| Review device | 0 | 1 | 0.54 | 0.499 |

| Consumption satisfaction | 1 | 3 | 1.91 | 0.339 |

| The level of involvement (In) | 0.000 | 7.601 | 2.692 | 1.053 |

| Picture | 0 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.339 |

| Helpfulness of OCR | 0 | 734 | 0.59 | 14.233 |

4.1.2. Empirical analysis

Firstly, the linear regression technique is used to test the effect of with or without picture on the helpfulness of OCRs (H1a). The result indicates that with or without picture significantly affects the helpfulness of OCRs (β = 0.087, p < 0.001). As we hypothesized that OCRs with picture would be more helpful than those without picture, hypothesis H7a is supported.

Secondly, the logistic regression technique is used to test the research hypotheses H1a-H6a with a binary dependent variable. Reviewer rank, product type, time interval, review device, consumption satisfaction, and the level of involvement are independents, and picture is the dependent. The results show that the value of Chi-square is: χ2 (df = 6, N = 6211) = 881.360, p < 0.001, which indicates that the full model is statistically significant, i.e., the variables included in the model can explain the with or without picture well. The value of pseudo R2 (Nagelkerke R2) is 0.244, which approximately summarizes the proportion of variance in the dependent variable of with or without picture associated with the predictors. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test (p = 0.515), which also checks the overall fit of the model, came out to be insignificant. According to Patharia et al. [51], the result indicates that the model shows insignificant difference between the observed and predicted classification of the OCRs.

The results indicate that product type (B = 0.244, p < 0.01), time interval (B = −0.452, p < 0.001), review device (B = 1.653, p < 0.001), consumption satisfaction (B = 0.333, p < 0.05), and the level of involvement (B = 0.790, p < 0.001) significantly affect picture, whereas reviewer rank has no significant effect (p = 0.114) (Table 4). As we hypothesized that reviewers with a higher status rank, reviewing search products versus experience products, posting reviews in a shorter time interval, submitting reviews via a mobile device versus a PC, with higher consumption satisfaction, and with higher involvement would be more likely to share picture in their online reviews, hypotheses H2a-H6a are supported, while H1a is not.

Table 4.

The results of the effects of 5W1H on picture.

| 5W1H | B | S.E. | Sig. | Exp (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reviewer rank | 0.063 | 0.040 | 0.114 | 1.065 |

| Product type | 0.244 | 0.085 | 0.004 | 1.276 |

| Time interval | −0.452 | 0.036 | 0.000 | 0.636 |

| Review device | 1.653 | 0.101 | 0.000 | 5.223 |

| Consumption satisfaction | 0.333 | 0.143 | 0.020 | 1.395 |

| The level of involvement | 0.790 | 0.043 | 0.000 | 2.203 |

4.2. Predictors, picture count, and helpfulness of OCRs

4.2.1. Descriptive statistics

This section aims to test the effect of picture count on the helpfulness of OCRs and the effect of reviewer rank, product type, time interval, review device, consumption satisfaction, and the level of involvement on picture count in OCRs. Those reviews without picture in the 6211 samples collected from JD.com are not employed to make analysis. Table 5 provides the descriptive statistics of the 821 reviews which include at least one picture.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics for picture count context (n = 821).

| Variable | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reviewer rank | 1 | 5 | 3.83 | 0.949 |

| Product type | 0 | 1 | 0.62 | 0.486 |

| Time interval (In) | 0.000 | 4.500 | 1.811 | 1.077 |

| Review device | 0 | 1 | 0.81 | 0.395 |

| Consumption satisfaction | 1 | 3 | 1.94 | 0.260 |

| The level of involvement (In) | 0.000 | 6.466 | 2.300 | 0.928 |

| Picture count | 1 | 10 | 2.5 | 2.160 |

| Helpfulness of OCR | 0 | 734 | 3.76 | 37.799 |

4.2.2. Empirical analysis

Firstly, the linear regression technique is used to test the effect of picture count on the helpfulness of OCRs (H7b). The result indicates that picture count significantly affects the helpfulness of OCRs (β = 0.185, p < 0.001). As we hypothesized that OCRs with more pictures would be more helpful, H7b is supported.

Secondly, the linear regression technique is used to test the relationships between the six predictors and picture count (H1b-H6b). Reviewer rank, product type, time interval, review device, consumption satisfaction, and the level of involvement are independents, and picture count is the dependent. The results show that the R2 is 0.136, which summarizes the proportion of variance in the dependent variable of picture count associated with the predictors. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) is used to measure the severity of multicollinearity in the ordinary least square regression analysis. The results show that the values of VIF are between 1 and 2, which indicates that the multicollinearity is not serious in this study.

The results indicate that review device (β = −0.084, p < 0.05), consumption satisfaction (β = 0.063, p < 0.05), and the level of involvement (β = 0.340, p < 0.001) significantly affect picture count, whereas reviewer rank, product type, and time interval have no significant effect (Fig. 2). As we hypothesized that reviewers with a higher status rank, reviewing search products versus experience products, posting reviews in a shorter time interval, submitting reviews via a mobile device versus a PC, with more polar consumption satisfaction, and with higher involvement would be likely to share more pictures in their online reviews, hypotheses H5b, H6b are supported, while H1b-H4b are not.

Fig. 2.

The linear regression results for picture count context

Note: *---p<0.05; **---p<0.01; ***---p<0.001; n---not significance.

5. Discussion

With or without picture and picture count both influence the helpfulness of OCR. The findings are fit with previous studies that OCRs with picture are more helpful than those without picture and the number of pictures positively affect review usefulness [7,10]. Picture in OCRs captures the details of products, which affords tangible reference points to other consumers [4]. More pictures afford more tangible reference points. Hence, both picture and picture count affect the helpfulness of OCR.

Product type significantly affects whether consumers share or not share picture in OCRs, but it has no significant effect on picture count when consumers decide to share picture. Because of the difference between search and experience products, product attributes are more useful in helping readers evaluate the quality of search products than experience products [34]. The main information presented by product picture is product attributes. Altruistic motivation is an important driver of posting online reviews [52,53]. When consumers think that the picture of experience product purchased has lower value for readers, they may have less motive to share picture in OCRs. This may be the reason that consumers are more likely to share picture in OCRs when they review search products. In addition, once consumers think that the picture of experience product purchased also has good value for readers, they may have motive to share the same number of pictures as they do for search products. Hence, product type has a significant effect on with or without picture but has no significant effect on picture count.

Time interval negatively affects whether consumers share or not share picture in OCRs, but it has no significant effect on picture count when consumers decide to share picture. It fits with Huang et al. that time interval amplifies consumers’ high-level construal of textual OCRs [38]. Pictures are highly concrete [33], which are more likely to be shared in near temporal distance. Hence, time interval has a significantly negative effect on whether consumers share or not share picture in OCRs. However, when consumers still decide to share picture for some reason after a long-time interval, they may not be affected by the concrete characteristic of picture and then have the same picture sharing behavior as they do in a short interval. Hence, time interval has a significant effect on with or without picture but has no significant effect on picture count.

Review device significantly positively affects whether consumers share or not share picture in OCRs, but it has a significant negative effect on picture count. As mobile devices are more portable and more flexible in usage time and space than PCs [40,41] and which are generally equipped with camera, sharing picture in OCRs by using mobile devices is more convenient than using PCs. Hence, when consumers decide whether to share picture, they are more likely to share via mobile devices than via PCs. However, when consumers decide to share picture, those who overcome the inconvenience of taking and uploading pictures via PCs may be more willing to share more picture to match their effort. Hence, review device has a significant positive effect on with or without picture but has a significant negative effect on picture count.

The polarity of consumption satisfaction positively affects whether consumers share or not share picture in OCRs, and it also has a positive effect on picture count when consumers decide to share picture. When the consumption satisfaction of consumers is high, they may be willing to share and share more pictures in an online review to express their good mood and share their success; when their consumption dissatisfaction is high, they may be willing to share and share more pictures in an online review to vent their frustrations, to retaliate against the seller, or to benefit others. Hence, the polarity of consumption satisfaction has a positive effect on whether consumers share or not share picture and picture count in OCRs.

The level of involvement positively affects whether consumers share picture in OCRs, and it also has a positive effect on picture count when consumers decide to share picture. When consumers have a higher level of involvement in posting online reviews, they are willing to spend more time and effort to evaluate the product purchased in reviews. As sharing picture is a part of posting online reviews, consumers who are willing to spend much time and effort in posting online reviews will be willing to share picture and even share more pictures. Hence, the level of involvement has a positive effect on whether consumers share picture or not and picture count.

Reviewer rank has no significant effect on whether consumers share picture or not and picture count in OCRs. These results are inconsistent with our hypotheses. According to JD. com's rules, membership levels are calculated not only by the number of reviews posted, but also by the number of logins and purchases. Whether consumers share pictures may have more to do with how often they comment than with how often they log in and shop. This may be the reason why the effect of reviewer rank on whether consumers share picture or not and picture count are not significant.

6. Contributions, implications, and limitations

Our study has several implications for academic research. First, our study extends the literature on OCRs. Although there has been a huge amount of research in the field of OCRs, these studies mainly focus on star ratings and textual reviews, and there is only limited research on graphical reviews. Moreover, these limited studies on graphical reviews mainly focus on their consequences. Sharing picture in OCRs is the premise of the impact of graphical reviews on consumption. However, knowledge about the antecedents of sharing picture in OCRs is scarce. This work is one of the first to systematically investigate the determinants of picture sharing in OCRs by analyzing real online reviews, which complements the research on graphical reviews in the online review literature.

Second, our study enriches the picture superiority effect. The conclusions of this work support the picture superiority effect and further examine how to practice the effect. To the best of our knowledge, this work is the first study to distinguish between with or without picture and picture count and reveals the differences in the predictors between whether consumers sharing picture and picture count, which provides insight into the acquisition of picture superiority effect.

Third, our study complements the knowledge sharing theory literature. This work finds several differences between sharing picture and textual content: (1) In terms of product types, previous research shows that the word count of search products is fewer than that of experience products [32]. In contrast, this work finds that consumers are more likely to share picture in OCRs when they review search products (vs. experience products). When consumers have the willingness to share, the product type no longer affects the count of pictures shared. (2) In terms of time interval, previous studies show that time interval affects consumers’ textual review behavior [28,35]. However, this work finds that while the time interval negatively affects whether consumers share pictures, once they are willing to share, it no longer affects the count of pictures shared. (3) In terms of review device, preview studies show that the word count of OCRs submitted via mobile devices is shorter than via PCs [39,42]. However, this work finds that while consumers are more likely to share pictures via mobile devices than via PCs, they share more pictures via PCs than via mobile devices once they are willing to share pictures. These new findings contribute to a better understanding of consumer knowledge-sharing behavior.

Our study also has several practical implications for online stores. First, e-retailers should encourage post-purchase consumers share more product pictures in OCRs, not just sharing. This work finds that whether OCRs with or without picture and picture count are helpful. More pictures in OCRs have better diagnostic to help potential customers reduce the uncertainty of purchase decisions, improve purchase confidence, and accelerate purchase decision. Hence, online stores which do not have plentiful product pictures in OCRs not only need to encourage consumers to share picture, but also should pay attention to encourage them to share more pictures.

Second, e-retailers can encourage post-purchase consumers post online reviews as soon as possible after they received product. This work finds that the number of days between the purchase day and review posting day is shorter, consumers are more likely to share picture in OCRs. Hence, online stores which do not have plentiful product pictures in OCRs should take tactics to encourage consumers post online reviews as early as possible. For example, with the development of logistics technology, e-retailers can real-time track the logistics information of product packages. When consumers receive their package, e-retailers can send message to inform them that the package has been sign for it and request them to post online review with more product pictures as early as possible to help other consumers make decision.

Third, online stores which want to promote more consumers to share picture can encourage consumers to post online reviews via their mobile device, while those want to promote consumers to share more pictures should encourage consumers to post online reviews via their PC. This work shows that when consumers post online reviews with mobile devices (vs. PCs), they are more likely to share picture, whereas they share more pictures when they post online reviews with PCs (vs. mobile devices).

Fourth, e-retailers can encourage consumers who have positive attitude toward purchase experience share more pictures in OCRs. This work shows that consumers with a higher consumption satisfaction are more likely to share picture and share more pictures in online reviews. Hence, online stores which do not have plentiful product pictures in OCRs can encourage satisfied consumers share product pictures in OCRs. For example, e-retailers can take active after-sale to pay a return visit to know the attitude of consumers on the product received. Those consumers who express their satisfaction at the purchase experience can be requested to share more pictures in online reviews.

Fifth, e-retailers should encourage consumers write more words and share more pictures in online reviews at the same time. This work shows that consumers who write more words are more likely to share picture and share more pictures in online reviews, and previous studies show that more detailed OCRs have better diagnostic to help potential customers make decisions [32,34]. Hence, encouraging consumers write more words and share more pictures at the same time helps not only the decision making of potential customers but also the promotion of reviewers sharing more pictures.

Though this work provides meaningful implications, there are still several limitations that should be addressed in future studies. First, as this work focuses on the number of pictures in OCRs, the content of pictures is not considered, which can be considered in future studies. Second, in this study the data were collected from JD.com in China. People with different cultures have differences in OCRs [54]. Data from other countries with different cultures can be considered in future studies. Third, Jingdong, the data source of this study, converts the status of login, shopping and posting reviews into growth value to determine the rank of reviewers. Since different companies adopt different membership level rules, the impact of other membership level systems can be considered in future studies. Fourth, the R2 of the research results is only 24.4 % and 13.6 %, respectively. Other variables outside the variables used in the research should be considered in future studies, such as the reviewer characteristics of personality, psychological, and demographic characteristics.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Funding

This research was supported by the Soft science project of Henan science and Technology Department, grant number 212400410507.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lili Su: Writing - original draft, Validation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Dong Hong Zhu: Writing - review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Lili Su, Email: suyy1015@zua.edu.cn.

Dong Hong Zhu, Email: zhudonghong1982@126.com.

References

- 1.Paivio A. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1990. Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stenberg G. Conceptual and perceptual factors in the picture superiority effect. Eur. J. Cognit. Psychol. 2006;18(6):813–847. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang S.-B., Hlee S., Lee J., Koo C. An empirical examination of online restaurant reviews on Yelp.com: a dual coding theory perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hospit. Manag. 2017;29(2):817–839. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casaló L.V., Flavián C., Guinalíu M., Ekinci Y. Avoiding the dark side of positive online consumer reviews: enhancing reviews' usefulness for high risk-averse travelers. J. Bus. Res. 2015;68:1829–1835. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lightner N.J., Eastman C. User preference for product information in remote purchase environments. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2002;3(3):174–186. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu P., Chen L., Santhanam R. Will video be the next generation of e-commerce product reviews? Presentation format and the role of product type. Decis. Support Syst. 2015;73:85–96. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng Y.H., Ho H.Y. Social influence's impact on reader perceptions of online reviews. J. Bus. Res. 2015;68:883–887. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hou F., Li B., Chong A.Y.-L., Yannopoulou N., Liu M.J. Understanding and predicting what influence online product sales? A neural network approach. Prod. Plann. Control. 2017;28(11–12):964–975. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveira B., Casais B. The importance of user-generated photos in restaurant selection. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology. 2019;10(1):2–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoon S.-J. A social network approach to the influences of shopping experiences on e-WOM. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012;13(3):213–223. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park H., Woo W. In: IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Media, Art, Social Science. Stadon J., Gwilt I., Smith C.H., editors. Humanities and Design; Fukuoka, Japan: 2015. Metadata design for location-based film experience in augmented places. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlos F.B., Raquel G.S., Carlos O.S. Effects of visual and textual information in online product presentations: looking for the best combination in website design. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2010;19(6):668–686. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chau P.Y.K., Au G., Tam K.Y. Impact of information presentation modes on online shopping: an empirical evaluation of a broadband interactive shopping service. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2000;10(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin T.M.Y., Lu K.-Y., Wu J.-J. The effects of visual information in EWOM communication. J. Res. Indian Med. 2012;6(1):7–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu R.J., Wu H.H., Wang C.L. Why is a picture 'worth a thousand words'? Pictures as information in perceived helpfulness of online reviews. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021;45(3):364–378. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nazlan N.H., Tanford S., Montgomery R. The effect of availability heuristics in online consumer reviews. J. Consum. Behav. 2018;17(5):449–460. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zinko R., Stolk P., Furner Z., Almond B. A picture is worth a thousand words: how images influence information quality and information load in online reviews. Electron. Mark. 2020;30(4):775–789. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park C.W., Sutherland I., Lee S.K. Effects of online reviews, trust, and picture-superiority on intention to purchase restaurant services. J. Hospit. Tourism Manag. 2021;47:228–236. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filieri R., Lin Z.B., Pino G., Alguezaui S., Inversini A. The role of visual cues in eWOM on consumers' behavioral intention and decisions. J. Bus. Res. 2021;135:663–675. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohring M., Keller B., Schmidt R., Dacko S. Google popular times: towards a better understanding of tourist customer patronage behavior. Tourism Rev. 2021;76(3):553–569. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H.Y., Ji H.P., Liu H., Cai D., Gao H.C. Is a picture worth a thousand words? Understanding the role of review photo sentiment and text-photo sentiment disparity using deep learning algorithms. Tourism Manag. 2022;92 Article number: 104559. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu H.B., Feng S.Z., Hu X.B. Process vs. outcome: effects of food photo types in online restaurant reviews on consumers' purchase intention. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2022;102 Article number: 103179. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu X., Luo J.F., Wu Z.Y. Conspicuous display through photo sharing in online reviews: evidence from an online travel platform. Inf. Manag. 2022;59(8) Article number: 103705. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu D.P., Deng L.F., Fan X., Ye Q. Influence of travel distance and travel experience on travelers' online reviews: price as a moderator. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2022;122(4):942–962. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang M.Y., Zhao H.C., Chen H.P. How much is a picture worth? Online review picture background and its impact on purchase intention. J. Bus. Res. 2022;139:134–144. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuckert M., Liu X., Law R. Stars. Votes, and badges: how online badges affect hotel reviewers. J. Trav. Tourism Market. 2016;33(4):440–452. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X., Schuckert M., Law R. Online incentive hierarchies, review extremity, and review quality: empirical evidence from the hotel sector. J. Trav. Tourism Market. 2016;33(3):279–292. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu D., Hong Y., Wang K., Fan W. Effects of membership tier on user content generation behaviors: evidence from OCRs. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018;18(3):457–483. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson C., Hildreth J.A., Howland L. Is the desire for status a fundamental human motive? A review of the empirical literature. Psychol. Bull. 2015;141(3):574–601. doi: 10.1037/a0038781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chua A.Y.K., Banerjee S. Helpfulness of user-generated reviews as a function of review sentiment, product type and information quality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;54:547–554. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bae S., Lee T. Product type and consumers' perception of online consumer reviews. Electron. Mark. 2011;21(4):255–266. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mudambi S.M., Schuff D. What makes a helpful online review? A study of customer reviews on amazon. Com. MIS Quarterly. 2010;34:185–200. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rim S., Amit E., Fujita K., Trope Y., Halbeisen G., Algom D. How words transcend and pictures immerse: on the association between medium and level of construal. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2015;6(2):123–130. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pan Y., Zhang J.Q. Born unequal: a study of the helpfulness of user-generated product reviews. J. Retailing. 2011;87(4):598–612. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma X., Khansa L., Deng Y., Kim S.S. Impact of prior reviews on the subsequent review process in reputation systems. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2013;30(3):279–310. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trope Y., Liberman N. Temporal construal and time-dependent changes in preference. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000;79:876–889. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trope Y., Liberman N. Temporal construal. Psychol. Rev. 2003;110(3):403–421. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.110.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang N., Burtch G., Hong Y., Polman E. Effects of multiple psychological distances on construal and consumer evaluation: a field study of online reviews. J. Consum. Psychol. 2016;26(4):474–482. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piccoli G., Ott M. Impact of mobility and timing on user-generated content. MIS Q. Exec. 2014;13(3):147–157. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghose A., Goldfarb A., Han S.P. How is the mobile internet different? Search costs and local activities. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013;24(3):613–631. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang R.J.H., Malthouse E.C., Krishnamurthi L. On the go: how mobile shopping affects customer purchase behaviour. J. Retailing. 2015;91(2):217–234. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu D.H., Deng Z.Z., Chang Y.P. Understanding the influence of submission devices on online consumer reviews: a comparison between smartphones and PCs. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2020;54 Article number: 102028. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mariani M.M., Borghi M., Gretzel U. Online reviews: differences by submission device. Tourism Manag. 2019;70:295–298. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sang J., Fang Q., Xu C. Exploiting social-mobile information for location visualization. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology. 2017;8(3) Article number: 39. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu N., Pavlou P.A., Zhang J. Overcoming the J-shaped distribution of product reviews. Commun. ACM. 2009;52(10):144–147. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanchez-Franco M.J., Navarro-Garcia A., Rondan-Cataluna F.J. Online customer service reviews in urban hotels: a data mining approach. Psychol. Market. 2016;33(12):1174–1186. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu D.H., Zhang Z.J., Chang Y.P., Liang S. Good discounts earn good reviews in return? Effects of price promotion on online restaurant reviews. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2019;77:178–186. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greene W.H. fifth ed. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2003. Econometric Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osgood C., Tannenbaum P. The principle of congruity in the prediction of attitude change. Psychol. Rev. 1955;62:42–55. doi: 10.1037/h0048153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wakefield R. The influence of user affect in online information disclosure. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2013;22(2):157–174. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patharia I., Rastogi S., Vinayek R., Malik S. A fresh look at environment friendly customers' profile: evidence from India. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Res. 2020;20(3):310–321. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathwick C., Mosteller J. Online reviewer engagement: a typology based on reviewer motivations. J. Serv. Res. 2017;20(2):204–218. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheung C.M.K., Lee M.K.O. What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion platforms. Decis. Support Syst. 2012;53(1):218–225. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu D.H., Ye Z.Q., Chang Y.P. Understanding the textual content of online customer reviews in B2C websites: a cross-cultural comparison between the U.S. and China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;76:483–493. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.