Abstract

Background

There is currently much focus on provision of general physical health advice to people with serious mental illness and there has been increasing pressure for services to take responsibility for providing this.

Objectives

To review the effects of general physical healthcare advice for people with serious mental illness.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register (last update search October 2012) which is based on regular searches of CINAHL, BIOSIS, AMED, EMBASE, PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and registries of Clinical Trials. There is no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records in the register.

Selection criteria

All randomised clinical trials focusing on general physical health advice for people with serious mental illness..

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data independently. For binary outcomes, we calculated risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI), on an intention‐to‐treat basis. For continuous data, we estimated the mean difference (MD) between groups and its 95% CI. We employed a fixed‐effect model for analyses. We assessed risk of bias for included studies and created 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADE.

Main results

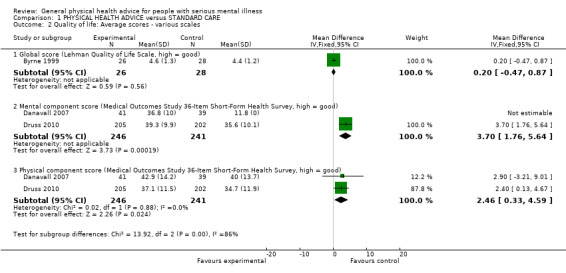

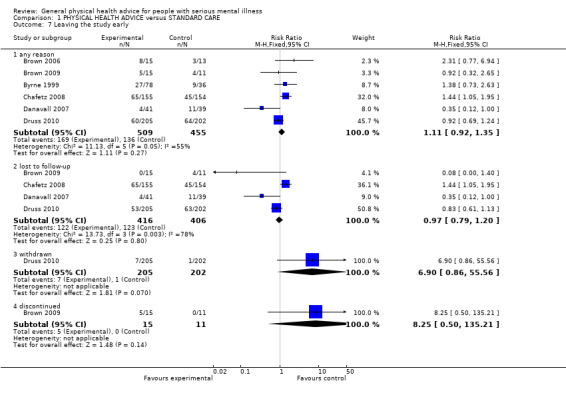

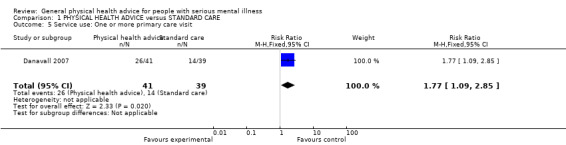

Seven studies are now included in this review. For the comparison of physical healthcare advice versus standard care we identified six studies (total n = 964) of limited quality. For measures of quality of life one trial found no difference (n = 54, 1 RCT, MD Lehman scale 0.20, CI ‐0.47 to 0.87, very low quality of evidence) but another two did for the Quality of Life Medical Outcomes Scale ‐ mental component (n = 487, 2 RCTs, MD 3.70, CI 1.76 to 5.64). There was no difference between groups for the outcome of death (n = 487, 2 RCTs, RR 0.98, CI 0.27 to 3.56, low quality of evidence). For service use two studies presented favourable results for health advice, uptake of ill‐health prevention services was significantly greater in the advice group (n = 363, 1 RCT, MD 36.90, CI 33.07 to 40.73) and service use: one or more primary care visit was significantly higher in the advice group (n = 80, 1 RCT, RR 1.77, CI 1.09 to 2.85). Economic data were equivocal. Attrition was large (> 30%) but similar for both groups (n = 964, 6 RCTs, RR 1.11, CI 0.92 to 1.35). Comparisons of one type of physical healthcare advice with another were grossly underpowered and equivocal.

Authors' conclusions

General physical health could lead to people with serious mental illness accessing more health services which, in turn, could mean they see longer‐term benefits such as reduced mortality or morbidity. On the other hand, it is possible clinicians are expending much effort, time and financial resources on giving ineffective advice. The main results in this review are based on low or very low quality data. There is some limited and poor quality evidence that the provision of general physical healthcare advice can improve health‐related quality of life in the mental component but not the physical component, but this evidence is based on data from one study only. This is an important area for good research reporting outcome of interest to carers and people with serious illnesses as well as researchers and fundholders.

Plain language summary

General physical health care advice for people with serious mental illness

People with serious mental illness tend to have poorer physical health than the general population with a greater risk of contracting diseases and often die at an early age. In schizophrenia, for example, life expectancy is reduced by about 10 years. People with mental health problems have higher rates of heart problems (cardiovascular disease), infectious diseases (including HIV and AIDS), diabetes, breathing and respiratory disease, and cancer.

Advising people on ways to improve their physical health is not without problems since there is often a perception, that advice offered is ineffective and will be ignored but it has been shown that healthcare professional advice can have a positive impact on behaviour. Advice can often motivate people to seek further support and treatment. Health advice could improve the quality and duration of life of people with serious mental illness. There is currently much focus on general physical health advice for people with serious mental illness with increasing pressure for health services to take responsibility for providing better advice and information.

This review focuses specifically on studies of general physical health advice and excludes more targeted health interventions.

Based on an electronic search carried out in 2012, this review now includes seven studies that randomised a total of 1113 people with serious mental illness. Six studies compared general physical health advice with standard care, one compared advice on healthy living with artistic techniques such as sketching and pottery. Information was of limited low or very low quality, there were a small number of participants and findings were ambiguous.

There is some limited evidence that the provision of physical healthcare advice can improve health‐related quality of life mentally but not physically. No studies returned results that suggest that physical healthcare advice has a powerful effect on physical healthcare behaviour or risk of ill health. More work is needed in this area. Only one adverse effect outcome was presented, death, but there were no differences between the treatment groups for this outcome.

Funders and policy makers should be aware that there may be some benefit for physical health advice for people with serious mental illness. There is an increased demand for preventative health services that involve the provision of advice and which may also reduce costs to health services.

This plain language summary has been written by a consumer, Ben Gray from RETHINK.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. PHYSICAL HEALTH ADVICE versus STANDARD CARE for people with serious mental illness.

| PHYSICAL HEALTH ADVICE versus STANDARD CARE for people with serious mental illness | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with people with serious mental illness Settings: Intervention: PHYSICAL HEALTH ADVICE versus STANDARD CARE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | PHYSICAL HEALTH ADVICE versus STANDARD CARE | |||||

| Physicl health awareness ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported on this outcome, which we had pre‐stated to be of importance. |

| Physical health behaviour moderate or vigorous physical activity Follow‐up: 6 months | The mean physical health behaviour in the control groups was 152 minutes | The mean physical health behaviour in the intervention groups was 39 higher (76.53 lower to 154.53 higher) | 80 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 | ||

| Quality of life Lehman Quality of Life Scale. Scale from: 1 to 7 Follow‐up: 18 months | The mean quality of life in the control groups was 4.45 points4 | The mean quality of life in the intervention groups was 0.2 higher (0.47 lower to 0.87 higher) | 54 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,5 | ||

| Adverse effects Death of participant Follow‐up: median 6‐12 months | Low‐risk population6 | RR 0.98 (0.27 to 3.56) | 487 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3,7 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (3 to 36) | |||||

| Medium‐risk population6 | ||||||

| 15 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (4 to 53) | |||||

| High‐risk population6 | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (14 to 178) | |||||

| Economic ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported on this outcome we had pre‐stated to be of importance. |

| Leaving the study early | Study population | RR 1.11 (0.92 to 1.35) | 964 (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,8 | ||

| 300 per 1000 | 333 per 1000 (276 to 405) | |||||

| Medium‐risk population | ||||||

| 292 per 1000 | 324 per 1000 (269 to 394) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations of design: rated 'serious' (lack of allocation concealment) 2 Limitations of design: rated 'serious' (lack of blinding) 3 Imprecision: rated 'serious' (small sample size) 4 Based on seven point Likert scale 5 Indirectness: rated 'serious' (authors admit that measurement tool was difficult to interpret) 6 Range based around data from control group 7 Limitations of design: rated 'serious' (duration of study may have negative effect on motivation) 8 Inconsistency: rated 'very serious' (some of the trials were cluster trials)

Summary of findings 2. HEALTH EDUCATION versus HEALTH EMPOWERMENT EDUCATION for people with serious mental illness.

| HEALTH EDUCATION versus HEALTH EMPOWERMENT EDUCATION for people with serious mental illness | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with serious mental illness Settings: Intervention: HEALTH EDUCATION versus HEALTH EMPOWERMENT EDUCATION | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | HEALTH EDUCATION versus HEALTH EMPOWERMENT EDUCATION | |||||

| Physical health awareness ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported on this outcome we had pre‐stated to be of importance. |

| Physical health behaviour ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported on this outcome we had pre‐stated to be of importance. |

| Quality of Life Lehaman Quality of Life Scale. Scale from: 1 to 7. Follow‐up: 12 months | The mean quality of life in the control groups was 4.45 points | The mean Quality of Life in the intervention groups was 0.3 lower (0.99 lower to 0.39 higher) | 51 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3,4 | ||

| Adverse Effects | Study population | RR 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0) | See comment | ||

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Medium‐risk population | ||||||

| Economic ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | |

| Leaving the study early Follow‐up: mean 12 months | Low‐risk population5 | RR 0.56 (0.26 to 1.19) | 78 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3,4 | ||

| 200 per 1000 | 112 per 1000 (52 to 238) | |||||

| Medium‐risk population5 | ||||||

| 300 per 1000 | 168 per 1000 (78 to 357) | |||||

| High‐risk population5 | ||||||

| 500 per 1000 | 280 per 1000 (130 to 595) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Limitations of design: rated 'serious' (lack of allocation concealment) 2 Limitations of design: rated 'serious' (lack of blinding) 3 Imprecison: rated 'serious' (small sample size) 4 Imprecision: rated 'serious' (high attrition rate) 5 Fewtrell et al. Arch Dis Child 2008; 93: 458‐461 (doi: 10.11361adc.2007.127316)

Summary of findings 3. HEALTHY LIVING STUDY CIRCLE versus AESTHETIC STUDY CIRCLE for people with serious mental illness.

| HEALTHY LIVING STUDY CIRCLE versus AESTHETIC STUDY CIRCLE for people with serious mental illness | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with people with serious mental illness Settings: Intervention: HEALTHY LIVING STUDY CIRCLE versus AESTHETIC STUDY CIRCLE | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | HEALTHY LIVING STUDY CIRCLE versus AESTHETIC STUDY CIRCLE | |||||

| Physical health: Identification of disease state (Metabolic syndrome) | Study population | RR 1.25 (0.35 to 4.49) | 13 (1 study7) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3,4,5,6 | ||

| 400 per 10001 | 500 per 1000 (140 to 1000)1 | |||||

| Medium‐risk population | ||||||

| 400 per 10001 | 500 per 1000 (140 to 1000)1 | |||||

| Physical health behaviour ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported on this outcome we had pre‐stated to be of importance. |

| Quality of life ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | |

| Adverse Effects ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | |

| Economic ‐ not reported | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | |

| Leaving the study early | Study population | RR 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0) | See comment | ||

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Medium‐risk population | ||||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Cluster trial (n = 10), results subject to design effect calculation (D.E.=1.23) 2 Limitations of design: rated 'serious' (lack of allocation concealment) 3 Limitations of design: rated 'serious' (lack of blinding) 4 Duration of study may have a negative effect on motivation 5 Imprecison: rated 'serious' (small sample size) 6 Imprecision: rated 'serious' (high attrition rate) 7 National Institue of Health ‐ National Cholestrol Education Programme ‐ Adult Treatment Panel III 2001

Background

Description of the condition

The definition of serious mental illness with the widest consensus is that of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (Schinnar 1990) and is based on diagnosis, duration and disability (NIMH 1987). People with serious mental illness have conditions such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, over a protracted period of time, resulting in erosion of functioning in day to day life. A European survey put the total population‐based annual prevalence of serious mental illness at approximately two per thousand (Ruggeri 2000). People with serious mental illness have a higher morbidity and mortality from chronic diseases than the general population, and this results in a significantly reduced life expectancy (Robson 2007). In schizophrenia, for example, life expectancy is reduced by around 10 years (Newman 1991). Sufferers from serious mental illness have increased rates of cardiovascular disease, infectious diseases (including HIV) (Cournos 2005), non‐insulin dependent diabetes, respiratory disease and cancer (Dixon 1999; Robson 2007).

Description of the intervention

Physical health advice/promotion can take many forms, and these are highly divergent and dependent on environmental and socioeconomic factors. Physical health monitoring is the focus of a previous review (Tosh 2010a). Whereas monitoring is passive, advice is the active provision of preventative information. It has an educative component and is delivered in a gentle non‐patronising manner (Stott 1990). In the context of this review we suggest that physical health advice should not be delivered solely in the form of a structured programme or training approach. Currently, much health promotion/advice exists (Smith 2007; Smith 2007a; Solty 2009). This is often targeted at a discrete problem, such as poor diet or smoking. In this review, however, we focus on studies of general physical health advice and exclude more targeted approaches. By general physical health we mean that which is not in any way focused on any one condition, system or behaviour/intervention.

How the intervention might work

Advising people on ways to improve their physical health is not without problems since there is often a perception, from family doctors in particular, that advice offered is ineffective and patients will reject it (Sutherland 2003). This is not necessarily the case. It has been demonstrated that physician or healthcare professional advice can have a positive impact on behaviour (Kreuter 2000; Russell 1979). Advice can often act as the catalyst for motivating people to seek further support and treatment (Sutherland 2003). Given the evidence of increased rates of potentially preventable health problems in people with serious mental illness (Cournos 2005; Dixon 1999; Robson 2007), and the suggestion from a 2005 systematic review (Bradshaw 2005) that methodologically robust, healthy living interventions give "promising outcomes" in people with schizophrenia, we believe that appropriate health advice could improve the quality and duration of life for sufferers of serious mental illness. Additional benefits may include a reduction in dependence on medical services. "There are potential savings to be made on prescribing acute care budgets through prevention or early detection of serious illness in these groups of service users" (DoH 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

There is evidence to suggest that the physical health needs of people with serious mental illness are often "unrecognised, unnoticed or poorly managed" (DoH 2006). Neglecting the physical healthcare needs of people with serious mental illness adds to the already high burden placed on individuals, careers, communities and society as a whole. It is estimated that the economic and financial cost of mental health problems in the UK stands at £77 billion, mainly as a result of lost productivity (HM Government 2009). In November 2004 the UK's Department of Health published 'Choosing health: making healthy choices easier' (DoH 2005). This set out key principles to support the public to make healthier and more informed choices about lifestyles. A report by the UK's King's Fund indicated that 86% of the general public agreed that the UK Government has a responsibility to provide information and advice to prevent illness (Kings Fund 2004). Despite government policy and the public desire for more physical healthcare advice, we could not identify any systematic reviews that refer to randomised controlled trials though a "systematic review of the published and grey literature" (Bradshaw 2005) concluded that "further research is needed to assist in the development of effective interventions to help this client group" (people with serious mental illness). This is one of a series of reviews (Table 4).

1. Series of related reviews.

| Title | Reference |

| General physical healthcare monitoring | Tosh 2010a |

| General physical healthcare advice | This review |

| Advice regarding smoking cessation | Khanna 2012 |

| Advice regarding oral health care | Khokhar 2011 |

| Advice regarding HIV/AIDs prevention | Wright 2012 |

| Advice regarding substance use | Underway |

Objectives

To review the effects of general physical healthcare advice for people with serious mental illness.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and economic evaluations conducted alongside included RCTs. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week. If we had encountered trials described in some way as to suggest or imply that the study was randomised and where the demographic details of each group's participants were similar, we intended to include them and in a sensitivity analysis of the effects of the presence or absence of these data.

Types of participants

We required that the majority of participants should be within the age range 18 to 65 years and suffering from severe mental disorder, preferably as defined by NIMH 1987 or, in the absence of this, from diagnosed illnesses such as schizophrenia, schizophrenia‐like disorders, bipolar disorder, or serious affective disorders. We did not consider substance abuse to be a severe mental disorder in its own right; however, we did feel that studies should remain eligible if they dealt with people with dual diagnoses, that is those with severe mental illness plus substance abuse. We did not include studies focusing on dementia, personality disorder and mental retardation, as they are not covered by our definition of severe mental disorder.

Types of interventions

1. General physical health advice

We have found it difficult to find a useful definition of ‘advice’. In the context of this review we define ‘advice’ as preventative information (Greenlund 2002) or counsel (Oxford English Dictionary) that leaves the recipient to make the final decision; it should have at least a suggestion of: i. an educative component; ii. a preventative aim; and iii. an ethos of self‐empowerment. Advice may be directional but not paternalistic in its delivery. It is not a programmed or training approach, focusing on the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and competencies as a result of formal teaching sessions.

We defined 'physical health' as 'soundness of body' as opposed to the World Health Organization's definition of 'health' which includes mental and social well being (WHO 1948).

‘General’ physical health advice involves the giving of advice that is not in any way focused on any one condition or system or behaviour/intervention.

2. Treatment as usual

Care in which physical health advice is not specifically emphasised above and beyond care that would be expected for people suffering from severe mental illness.

Types of outcome measures

For the purposes of this review we divided outcomes into four time periods, i. immediate (within one week) ii. short term (one week to six months) iii. medium term (six months to one year) and, iv. long term (over one year).

Primary outcomes

1. Physical health awareness

1.1 Failure to raise awareness of common physical health problems 1.2 Failure to raise awareness of behaviours which can contribute to ill‐health

2. Physical health behaviour

2.1 No substantial change in behaviour

Secondary outcomes

1. Physical health behaviour

1.1 No change in behaviour 1.2 Deterioration in physical health behaviour

2. Physical health

2.1 Failure to act on known risk factors 2.2 Failure to address disease potentially associated with psychiatric diagnosis 2.3 Failure to raise awareness of common physical health problems 2.4 Unchecked adverse effects of treatment

3. Quality of life

3.1 Loss of independence 3.2 Loss of activities of daily living (ADL) skills 3.3 Chronic pain 3.4 Immobility 3.5 Loss of social status 3.6 Healthy days 3.7 No clinically important change in general quality of life

4. Adverse event

4.1 Number of participants with at least one adverse effect 4.2 Clinically important specific adverse effects (cardiac effects, death, movement disorders, prolactin increase and associated effects, weight gain, effects on white blood cell count) 4.3 Average endpoint in specific adverse effects 4.4 Average change in specific adverse effects 4.5 Death ‐ natural or suicide

5. Service use

5.1 Hospital admission 5.2 Emergency medical treatment 5.3 Use of emergency services

6. Financial dependency

6.1 Claiming unemployment benefit 6.2 Claiming financial assistance because of a physical disability

7. Social

7.1 Unemployment/loss of earnings 7.2 Social isolation as a result of preventable incapacity 7.3 Increased burden to caregivers

8. Economic

8.1 Increased costs of health care 8.2 Days off sick from work 8.3 Reduced contribution to society 8.4 Family claiming careers’ allowance

9. Leaving the studies early (any reason, adverse events, inefficacy of treatment)

10. Global state

10.1 No clinically important change in global state (as defined by individual studies) 10.2 Relapse (as defined by the individual studies)

11. Mental state (with particular reference to the symptoms of schizophrenia)

11.1 No clinically important change in general mental state score 11.2 Average endpoint general mental score 11.3 Average change in general mental state score 11.4 No clinically important change in specific symptoms (positive/negative symptoms of schizophrenia) 11.5 Average endpoint specific symptom score 11.6 Average change in specific symptom score

12. 'Summary of findings' tables

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2008) and used the GRADE profiler (GRADE PRO) to import data from RevMan 5 (Review Manager) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes that we rated as important to patient‐care and decision making. We intended to include the following outcomes in a 'Summary of findings' table.

Physical health awareness ‐ Failure to raise awareness of common physical health problems or behaviours which can contribute to ill‐health

Physical health behaviour ‐ No substantial change in behaviour

Quality of life ‐ Loss of independence

Adverse event ‐ Clinically important specific adverse effects (cardiac effects, death, movement disorders, prolactin increase and associated effects, weight gain, effects on white blood cell count

Economic ‐ Increased costs of health care

Financial dependency ‐ Claiming financial assistance because of a physical disability

Global state ‐ No clinically important change in global state (as defined by individual studies)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. Original search (2009)

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trials Register was searched (November 2009) using the phrase:

[(*physical* or *cardio* or *metabolic* or *weight* or *HIV* or *AIDS* or *Tobacc* or *Smok* or *sex* or *medical* or *dental* or *alcohol* or *oral* or *vision* or *sight*or *hearing* or *nutrition* or *advice* or *monitor* in title of REFERENCES) AND (*education* OR *health promot* OR *preventi* OR *motivate* or *advice* or *monitor* in interventions of STUDY)]

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, handsearches and conference proceedings (see Group Module).

2. Update search (2012)

The Trials Search Co‐ordinator, Samantha Roberts, searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trials Register (October 2012) using the phrase:

[(*physical* or *cardio* or *metabolic* or *weight* or *HIV* or *AIDS* or *Tobacc* or *Smok* or *sex* or *medical* or *dental* or *alcohol* or *oral* or *vision* or *sight*or *hearing* or *nutrition* or *advice* or *monitor* in title of REFERENCES) AND (*education* OR *health promot* OR *preventi* OR *motivate* or *advice* or *monitor* in interventions of STUDY)]

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Registry of Trials is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including AMED, BIOSIS, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and registries of Clinical Trials) and their monthly updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings (see Group Module). There is no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations of inclusion of records in the register.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected the references of all identified studies for other relevant studies.

2. Personal contact

We contacted the first author of each included trial for information regarding unpublished studies, we also contacted the first author of each ongoing study and requested information about current progress. If authors responded with relevant information we used this and noted their response in the Characteristics of included studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the original review, review authors GT, AC and SM screened the results of theoriginal electronic search; to ensure reliability another review author MB inspected a random sample of the electronic search, comprising 10% of the total. GT and AC inspected all abstracts of studies identified through screening and identified potentially relevant reports. Where disagreement occurred we resolved this by discussion, and where there was still doubt, we acquired the full article for further inspection. We then requested the full articles of relevant reports for reassessment and carefully inspected them for a final decision on inclusion (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). In turn, GT and AC inspected all full reports and independently decided whether they met the inclusion criteria.

The results from the most recent 2012 electronic search were screened by JX who inspected all abstracts and identified potentially relevant reports. MW inspected full articles for final inclusion. JX, GT and AC were consulted in cases where there was uncertainty and a final decision was made when an agreement was reached by all authors. We were not blinded to the names of the authors, institutions or journal of publication.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

For the original review, authors GT and AC independently extracted data from included studies. Again, we discussed any disagreement, documented our decisions and, if necessary, we contacted the authors of studies for clarification. Whenever possible we only extracted data presented in graphs and figures, and we only included data if two review authors independently had the same result. We made attempts to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain any missing information or for clarification whenever necessary. Where possible, we extracted data relevant to each component centre of multi‐centre studies separately. From the 2012 update search, one of the studies previously listed as ongoing had been finished and the study was included in the review. JX and MW independently extracted data.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

For the original review, GT and AC extracted data onto standard, simple forms.

For the 2012 update, JX and MW independently extracted data from the new included study.

2.2 Data from multi‐centre trials

Where possible the authors verified independently calculated centre data against original trial reports.

3. Rating scales

A wide range of instruments are available to measure outcomes in mental and physical health studies. They vary in quality and are often not validated or are created for a particular study. It is accepted generally that measuring instruments should be both reliable and have reasonable validity (Rust 1989). For the original review, we included continuous data from rating scales only if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and not those written or modified by one of the trialists for a particular trial.

4. Endpoint versus change data

We preferred to use scale endpoint data, which typically cannot have negative values and are easier to interpret from a clinical point of view. Change data are often not ordinal and are very problematic to interpret. We did not identify such data for this review update. For future updates of this review, If endpoint data are unavailable, we will use change data.

5. Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we applied the following standards to all data before inclusion: (a) standard deviations (SDs) and means are reported in the paper or obtainable from the authors; (b) when a scale starts from the finite number zero, the SD, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution (Altman 1996); (c) if a scale starts from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay 1986), which can have values from 30 to 210), the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2 SD > (S‐S min), where S is the mean score and S min is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied. When continuous data are presented on a scale which includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not. We entered skewed data from studies of less than 200 participants in other tables within the data analyses section rather than into an statistical analysis. Skewed data pose less of a problem when looking at means if the sample size is large, and in future updates of the review, we will enter skewed data from studies with large sample sizes into syntheses, if more data are identified.

6. Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital, (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month). Although common measure was not an issue in this update review, the above procedures will be followed in future updates.

7. Conversion of continuous to binary

We had planned to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data wherever possible, however the need did not arise. The conversion could be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the PANSS (Kay 1986; Kay 1987), could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005; Leucht 2005a). In future updates if data based on these thresholds are not available, we will use the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

8. Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for general physical health advice.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Again working independently, for the original review, GT and AC and for the update review JX and MW assessed risk of bias using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This tool encourages consideration of how the sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, the integrity of blinding at outcome, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other biases. We excluded studies where allocation was clearly not concealed. We did not include trials with high risk of bias (defined as at least three out of five domains categorised as 'No') in the meta‐analysis; we have summarised the results of our assessment of risk of bias in Figure 1. Where the raters disagreed, the final rating was made by consensus with the involvement of another member of the review group. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted the authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. We reported non‐concurrence in quality assessment.

1.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). The Number Needed to Treat/Harm (NNT/H) statistic with its confidence intervals is intuitively attractive to clinicians but is problematic both in its accurate calculation in meta‐analyses and interpretation (Hutton 2009). For binary data presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables, where possible, we calculated illustrative comparative risks.

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes we estimated the mean difference (MD) between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference SMD). However, for future updates if scales of very considerable similarity are used, we will presume there is a small difference in measurement, and will calculate effect sizes and transform the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, CIs unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

For studies where clustering was not accounted for, we would have presented data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. If we find cluster‐randomised trial data in subsequent versions of this review, we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra class correlation co‐efficient (ICC) of their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). If clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We sought statistical advice during the protocol state of this review, and were advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC (Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC) (Donner 2002). If the ICC is not reported, we will assume it to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies have been appropriately analysed taking into account ICC and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies will be possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). No cross‐over trials were identified from either search for this review, but as both effects are very likely in serious mental illness, in future updates we will only use data from the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

No studies with multiple treatment groups were identified for this review, but for future updates, it is planned that where a study involves more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we will present the additional treatment arms in comparisons. Where the additional treatment arms are not relevant, we will not reproduce these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). In the original review, for any particular outcome, if more than 50% of data were unaccounted for, we did not reproduce these data or use them within analyses. If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we have addressed this within the 'Summary of findings' tables by down‐rating quality. Finally, we also downgraded quality within the 'Summary of findings' tables where loss was 25% to 50% in total.

2. Binary

In the original review, in the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis). Those leaving the study early were assumed to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed, with the exception of the outcome of death and adverse effects. For these outcomes, the rate of those who remained in the study ‐ in that particular arm of the trial ‐ were used for those who did not. We intended to undertake sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change when data only from people who complete the study to that point are compared to the intention‐to treat analysis using the above assumptions, but only two studies in separate comparisons reported data for the primary outcome so this was not possible. We intend to follow this procedure in future updates if new studies with data for this outcome are identified.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

In the case where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50%, and data only from people who completed the study to that point were reported, we reproduced these.

3.2 Standard deviations

All data used in analyses were provided in the study reports. We had planned that if standard deviations (SDs) were not reported, we would first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and confidence intervals (CIs) available for group means, and either 'P' or 't' values available for differences in mean, we could calculate them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systemic reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011): When only the SE is reported, SDs are calculated by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systemic reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P, t or F values, CIs, ranges or other statistics. If these formulae do not apply, we can calculate the SDs according to a validated imputation method which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. We nevertheless examined the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values. We will follow these procedure in future updates.

3.3 Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that in some studies the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) would be employed within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results (Leucht 2007). Therefore, in the original review, where LOCF data were used in the trial, if less than 50% of the data had been assumed, we presented and used these data and indicated that they were the product of LOCF assumptions. This will be followed in future updates.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

To judge clinical heterogeneity, we considered all included studies, initially without seeing comparison data. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying situations or people which we had not predicted would arise. Where such situations or participant groups arose, we fully discussed these. The same procedure will be followed for future updates.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

For future updates, we will consider all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We will simply inspect all studies for clearly outlying methods which we had not predicted would arise. When such methodological outliers arise in updates, we will fully discuss these. This was carried out for the original review.

3. Statistical

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I‐squared statistic

In the original review, we investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 method alongside the Chi2 P value. The I2 provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on i. magnitude and direction of effects and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. ) value from Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2). An I2 estimate greater than or equal to around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic was interpreted as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). If relevant studies are identified in updated versions of this review where substantial levels of heterogeneity are found in the primary outcome, we will explore the reasons for heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). If the inconsistency is high and clear reasons are found, we will present data separately.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Section 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not plan to use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In future updates of this review, where funnel plots are possible, we will seek statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

Where possible, we used a fixed‐effect model for analyses. We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. According to our hypothesis of an existing variation across studies, to be explored further in the meta‐regression analysis, despite being cautious that random‐effects methods do put added weight onto the smaller of the studies, we will favour using the fixed‐effect model in future updates. The reader is, however, able to choose to inspect the data using the random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses

We did not conduct any subgroup analyses.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

2.1 Unanticipated heterogeneity

For future updates, should unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity be obvious, we will simply state hypotheses regarding these. We have not undertaken and do not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

2.2 Anticipated heterogeneity

We are concerned that focused physical healthcare advice may have different effects than a more general approach. We therefore anticipate some heterogeneity for the primary outcomes and will propose to summate all data but also present them separately.

Sensitivity analysis

1. Implication of randomisation

We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way as to imply randomisation. In future updates of this review, for the primary outcomes we will include these studies and if there is no substantive difference when we add the implied randomised studies to those with better description of randomisation, we will then use all data from these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

For future updates, where assumptions will need to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we will compare the findings of the primary outcomes where we used our assumptions with completer data only. If there is a substantial difference, we will report results and discuss them, but will continue to employ our assumption.

Results

Description of studies

For substantive description of studies please see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The initial search of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's register of trials in November 2009 was a combined search designed to identify studies which would be relevant to this review and to a series of sister reviews looking at more targeted advice relating to specific problems or behaviours (e.g. oral health, HIV, smoking), some of these are already underway and some are already published, seeTable 4. This search PRISMA diagram is seen in Figure 2). An additional electronic search was performed in October 2012 in order to identify recent studies relevant to this review (Figure 3).

2.

PRISMA search flow diagram ‐ 2009 search

3.

Study flow diagram ‐ updated 2012

The original search identified 2382 references (from 1558 studies). After examining search results, we identified 15 reports which were suitable for further assessment. Of these, six fulfilled criteria for inclusion, we excluded seven and confirmed that two were awaiting classification. In our most recent search in 2012, 2428 (46 additional) studies were identified, 33 of these were suitable for further evaluation, one of which ended up fulfilling criteria for inclusion and was a study that was previously listed as awaiting classification.

Included studies

For details of included studies please see Characteristics of included studies. The seven included studies randomised 1113 people. No study was double blind although Brown 2006, Brown 2009 and Danavall 2007 did attempt to maintain rater (single) blindness. Byrne 1999 and Forsberg 2008 were cluster trials.

1. Length of studies

Two of the included studies fell in to the short‐term category with a duration of six to 10 weeks. Danavall 2007 was categorised as medium term with a six‐month follow‐up, and the remaining four studies were in the long‐term category and had a duration of 12‐18 months.

2. Setting

Brown 2006, Brown 2009 and Danavall 2007 were conducted in community mental health teams, while Druss 2010 was set in primary care. Byrne 1999 and Forsberg 2008 took place in supported accomodation in the community and Chafetz 2008 was conducted in a crisis residential unit .

3. Participants

Participants in Brown 2006 and Brown 2009 were diagnosed using the International Classification of Diseases ((ICD), version 10) (WHO 2007). Byrne 1999 asked participants to self‐report what type of mental health problems they had, while Chafetz 2008, Danavall 2007 and Druss 2010 included patients who were diagnosed with a 'severe mental illness', but they did not specify any diagnostic manual. The remaining study, Forsberg 2008, used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM IV 1994).

4. Study size

The largest studies were Druss 2010 (n = 407) and Chafetz 2008 (n = 309); the smallest were Brown 2006 (n = 28) and Brown 2009 (n = 26). Danavall 2007 involved 80 participants. The other two studies were cluster trials. Byrne 1999 randomised 22 clusters, with a total of 214 people therein, and Forsberg 2008 10 clusters that comprised 97 people.

5. Interventions

5.1 General physical health advice

Brown 2006 and Brown 2009 looked at semi‐structured health promotion that involved participants receiving six semi‐structured health promotion sessions, which followed the Lilly "Meaningful Day" (Lilly 2002) manual. Byrne 1999 involved a one‐year physical health educational programme consisting of an intensive 12‐week programme with less intensive follow‐up for nine months focusing on overall wellness. Chafetz 2008 promoted skills in self‐assessment, self‐monitoring, and self‐management of physical health problems. Danavall 2007 delivered six sessions to help participants become more effective managers of their chronic illnesses involving chronic disease management, exercise and physical activity, pain and fatigue management, healthy eating on a limited budget, medication management and finding and working with a regular doctor. Druss 2010 examined the effect of care management. Care managers provided "communication and advocacy with medical providers", health education and support in overcoming barriers to primary health care. This was based on standardised approaches documented in the care management literature (Druss 2010). The program was designed to help overcome patient, provider, and system‐level barriers to primary medical care experienced by persons with mental disorders. Forsberg 2008's intervention took the form of a study circle: study material comprised a book focusing on motivation, food content, stress and fitness and they also used a further comparator (aesthetic study circle) as described below. Although the trials we inspected used different methods of delivering general physical health advice, we thought these methods to be comparable on the basis that all fell under our broad definition of general physical healthcare advice.

5.2 Comparators

Comparators were largely 'standard care', which was variously described as 'treatment as usual' (Brown 2006; Brown 2009), 'control group' (Byrne 1999) and 'usual care' (Chafetz 2008; Danavall 2007; Druss 2010). Three studies, however, did not give any detailed description of their comparators (Brown 2006; Brown 2009; Byrne 1999). Both Brown studies failed to describe what 'treatment as usual' was and Byrne 1999 did not explain what treatment the 'control group' received. Chafetz 2008 described 'usual care' as basic primary care delivered by nurse practitioners and was an established part of the crisis residential unit which was the setting for the study. Danavall 2007 reported that participants should receive all medical, mental health, and peer‐based services that they were otherwise receiving prior to entry into the study. Druss 2010 described 'usual care' in which participants were given a list with contact information for local primary care medical clinics, which accepted uninsured and Medicaid patients, and these participants were allowed to obtain any type of medical care or medical service. Forsberg 2008 compared the effect of their experimental 'healthy living study circle' with a control in the form of an 'aesthetic study circle'. This was a study circle in which participants had the opportunity to learn and practice various kinds of artistic techniques such as sketching and pottery (Forsberg 2008). Additionally, because Byrne 1999 was the three‐arm study, this trial compared a one‐year health education programme not only with 'standard care' but also with an empowerment programme based on a model developed by Freire (Freire 1974; Freire 1983). This involved "group efforts identifying their problems, assessing the roots of their problems, and developing their goals" in a three‐phase process. First "the listening phase", second the "participatory dialogue" and in the final stage "group members tested out their understanding of the problem in the real world" (Byrne 1999).

6. Outcomes

6.1 General remarks

We were unable to use data from some studies (Brown 2006; Brown 2009; Chafetz 2008) because raw scores were not presented. Instead, outcomes were presented as inexact P values without means and standard deviations. We were unable to use some data in Forsberg 2008 as they were not reported by group. Byrne 1999 failed to report changes between baseline and completion of the intervention, and Druss 2010 did not reveal the distribution of individuals between the intervention arm and the control.

6.2 Outcome scales

Details of scales that provided usable data are shown below. Reasons for exclusion of data from other instruments are given under 'Outcomes' in the Characteristics of included studies.

6.2.1 Physical health behaviour

6.2.1.1 SILVA™ Pedometer plus The SILVA™ Pedometer plus was used to obtain measure of physical activity by counting the number of steps for 10 hours per day for one week. A higher score represents a higher rate of physical activity (high = good).

6.2.2.2 Physical health

6.2.2.1 Metabolic syndrome defined by the National Cholesterol Education Programme Adult Treatment Panel (NCEP 2001) This is a criterion for identifying metabolic syndrome where at least three of the following five criteria are needed: i) glucose ≥ 6.1 mmol/L, ii) blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or treatment for this, iii) triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/L, iv) high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) men > 1.0 mmol/L or female > 1.3 mmol/L, and v) waist men >102 cm or female > 88 cm. A decrease in the number of people with metabolic syndrome was the desired outcome (low = good).

6.2.2.2 Incremental Shuttle Walk Test ‐ ISWT (Singh 1992) The ISWT requires participants to walk up and down a 10‐m shuttle course in a set time. It provides a direct comparison of an individual's performance (high=good).

6.2.2.3 Borg RPE (Rate of perceived exertion) Scale (Borg 1982) The Borg RPE is used to measure the perceived exertion before and after the Incremental Shuttle Walk Test was measured. The scale ranges between six and 20. Six means 'no exertion at all' and 20 means 'maximal exertion' (high=good).

6.2.3 Quality of life

6.2.3.1 Lehman Quality of Life Scale (Lehman 1988) The 127‐item questionnaire was administered in an interview format and assessed both subjective and objective indicators in eight domains: living situation daily activities and skills, family relations, social relations, finances, work and school, legal and safety issues and health. Satisfaction with life domains rated on a seven‐point scale: one is 'terrible' and seven is 'delighted' (high = good). 6.2.3.2 Medical Outcomes Study 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey ‐ MOS SF‐36 Health Survey (Ware 1998) The MOS SF‐36 Health Survey is a measure of health status designed for use in clinical practice, research, health policy evaluations, and general population surveys. It includes eight scales that assess the following general health concepts: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. Summary scores can be constructed ranging from zero (poor health) to 100 (perfect health) (high = good).

6.2.4 Service use

6.2.4.1 U.S. Preventative Services Task Force guidelines ‐ USPSTF guidelines (AHRQ 2009) This scale is used to assess the quality of primary care. The USPSTF conducts rigorous, impartial assessments of the scientific evidence for the effectiveness of a broad range of clinical preventive services, including screening, counselling, and preventive medications. Its recommendations are considered the "gold standard" for clinical preventive services. A total of 23 indicators were included across four domains: 1) physical examination, 2) screening tests, 3) vaccination and 4) education. The primary study outcome was an aggregate preventive services score representing the proportion of services for which an individual was eligible that was obtained by the participant. The higher the value represents the percentage of recommended preventative services received (high = good).

6.2.5 Economic

6.2.4.1 Health Service Utilization Inventory (Browne 1990) The Health Service Utilization Inventory is designed to assess direct and indirect costs of health resources. A dollar value of health resource consumption is determined (low = good).

6.3 Missing outcomes

We had outlined in the first protocol for this review that we wished to find outcomes relevant to physical health awareness and behaviour, general physical health, quality of life, adverse events, service use, financial dependency, social functioning, economic implications, leaving the study early, global state and mental state. Of these outcomes, we failed to find any data at all relating to physical health awareness, financial dependency, social functioning, global state or mental state.

Excluded studies

For details of the excluded studies please see Characteristics of excluded studies. The original search strategy yielded 2382 references (from 1558 studies). From these we requested 15 studies for closer inspection. We excluded seven of these studies because their focus was on global mental well being rather than general physical health. In our most recent search from 2012 that yielded 46 studies, 18 underwent closer inspection, one of which met criteria for inclusion. An additional 14 of the studies were excluded because their focus was not on general physical health, two were not randomised and one included an education component in both arms of the trial.

1. Awaiting assessment

There are no studies awaiting assessment.

2. Ongoing studies

One study remains ongoing for the 2012 update review. For further details please see Characteristics of ongoing studies. Given the relatively small projected sample size in this study (n = 170) and considering the potential dropout rate, we do not anticipate that data from this study would significantly alter or add to the results of this review, although we look forward to them for further insights, or to be proved wrong.

Risk of bias in included studies

For details please refer to the Risk of bias in included studies tables and Figure 1.

Allocation

All included studies were stated to be randomised. Three did not describe the randomisation procedure (Brown 2006; Byrne 1999; Chafetz 2008). One randomised using a hidden computer‐generated random number programme (Brown 2009) and two using a "computerised algorithm" (Danavall 2007; Druss 2010). The final study was randomised at group level by drawing lots by a "person not in the project" (Forsberg 2008).

Blinding

Two studies failed to provide details about blinding (Byrne 1999; Forsberg 2008). One (Brown 2006) "attempted to maintain rater blindness" and, in a similar study (Brown 2009), the rater was blind to the interviewees status. In Danavall 2007 and Druss 2010 the "interviewers were blinded to subjects' randomisation status" and in the remaining study (Chafetz 2008), the "baseline severity of medical comorbidity was rated by Nurse Practitioners blind to study group". No study reported if they tested blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

The overall rate of leaving the study early was considerable (34%). In five of the studies the rate of leaving the study early was clearly above 30% (Brown 2006; Brown 2009; Byrne 1999; Chafetz 2008; Druss 2010). It is possible that reasons for this attrition were balanced across groups ‐ but there is no evidence to support this and there is also the possibility that the reasons differed for leaving early. This makes the studies vulnerable to bias. Danavall 2007 lost all but one of their participants due to being unable to locate them at follow‐up. Forsberg 2008 was a cluster trial and did not report the rate of leaving early by group.

Selective reporting

It would appear that all of the included studies reported on all of their intended outcomes. We did not, however, have access to any of the study protocols to confirm this.

Other potential sources of bias

Brown 2006 was supported by Eli Lilly (pharmaceutical industry) who supplied the Lilly "Meaningful Day" package; this package was then adapted for use in the subsequent study (Brown 2009). Danavall 2007 reported that one of the authors received royalties from the publisher of the book that was written for the intervention delivered the in the study. For Druss 2010 the lead author "received research funding from Pfizer", a pharmaceutical company which manufactures a wide range of medicines for conditions such as heart disorders, cancer, raised blood pressure, high cholesterol and sexual health. Chafetz 2008 was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research and Forsberg 2008 received grants from five different public bodies in Sweden. The remaining study (Byrne 1999) was funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health.

Additionally, all trials were small trials that are themselves particularly associated with risks of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Comparison 1. Physical health advice versus standard care

Six studies provided data for the comparison physical health advice versus standard care. We calculated risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous data and mean differences (MD) for continuous data, with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) throughout.

1.1 Physical health behaviour

Danavall 2007 reported no significant difference between groups for moderate or vigorous physical activity, the data were skewed (n = 80, 1 RCT, MD 39.00, CI ‐76.53 to 154.53, Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PHYSICAL HEALTH ADVICE versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 1 Physical health behaviour: Moderate or vigorous physical activity (min/week, skewed).

1.2 Quality of life

This outcome (Analysis 1.2) was reported by Byrne 1999, Danavall 2007 and Druss 2010 using different scales. Byrne 1999 (using the Lehman scale) reported no significant difference in quality of life (n = 54, 1 RCT, MD 0.20, CI ‐0.47 to 0.87). Danavall 2007 and Druss 2010 reported separately on the mental and physical components of the Quality of Life Medical Outcomes Study reporting a significant difference for the mental component (n = 487, 2 RCTs, MD 3.70, CI 1.76 to 5.64) and in the physical component (n = 487, 2 RCTs, MD 2.46, CI 0.33 to 4.59).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PHYSICAL HEALTH ADVICE versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 2 Quality of life: Average scores ‐ various scales.

1.3 Adverse effects: death

Danavall 2007 reported only on death and Druss 2010 reported seven deaths with "no significant difference" between treatment and control groups (n = 487, 2 RCTs, RR 0.98, CI 0.27 to 3.56, Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PHYSICAL HEALTH ADVICE versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 3 Adverse effects/events: Death.

1.4 Service use

One study (Druss 2010) provided data for the comparison care management versus usual care. Results significantly favoured the active treatment group (n = 363, 1 RCT, MD 36.90, CI 33.07 to 40.73, Analysis 1.4). Danavall 2007 also reported that significantly more people who received physical health advice attended primary care appointments than those receiving standard care alone (n = 80, 1 RCT, RR 1.77, CI 1.09 to 2.85).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PHYSICAL HEALTH ADVICE versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 4 Service use: Average percentage uptake of recommended health preventative services (US Preventative Services Task Force guidelines, high = good).

1.4 Economic

Byrne 1999 reported no significant difference between groups for general health service expenses. These data are, however, skewed and we report them in a table (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PHYSICAL HEALTH ADVICE versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 6 Economic: Total value of health resource consumption (dollars, low = good, skewed data).

| Economic: Total value of health resource consumption (dollars, low = good, skewed data) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Interventions | Average consumption (US $) | SD | N |

| Byrne 1999 | Health empowerment | 1476.51 | 2191.98 | 36 |

| Byrne 1999 | Control | 956.63 | 2506.18 | 39 |

1.5 Leaving the study early

Six studies reported on participants leaving early for a variety of reasons; none identified any significant difference between experimental and control groups (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PHYSICAL HEALTH ADVICE versus STANDARD CARE, Outcome 7 Leaving the study early.

1.5.1 Any reason

Six of our seven included studies provided data for the outcome of leaving the study early for any reason (n = 964, 6 RCTs, RR 1.11, CI 0.92 to 1.35). Brown 2006 and Brown 2009 reported considerable loss to follow‐up with 39% in the first study and 35% in the second. However, attrition occurred relatively evenly across intervention groups (n = 54, 2 RCTs, RR 1.49 CI 0.71 to 3.14). Byrne 1999 saw 31.6 % of participants leaving early but did not comment on the reasons for leaving (n = 114, 1 RCT, RR 1.38, CI 0.73 to 2.63). Chafetz 2008 reported 35.6% of participants leaving early (n = 309, 1 RCT, RR 1.44, CI 1.05 to 1.95) and defined these simply as "lost to follow up", citing that some had died, some had "moved on" and some were incarcerated. Further specifics were not available for these different reasons for leaving early. Danavall 2007 had the smallest percentage of participants leaving the study early of 18.8% with only one having died and the remaining being unable to locate for follow‐up (n = 80, 1 RCT, RR 0.35, CI 0.12 to 1.00). Druss 2010 only commented on "loss to follow up" (30.5%, n = 407, 1 RCT, RR 0.83, CI 0.61 to 1.13).

1.5.2 Lost to follow‐up

Brown 2009, Chafetz 2008, Danavall 2007 and Druss 2010 all reported on loss to follow‐up (n = 822, 4 RCTs, RR 0.97, CI 0.79 to 1.20).

1.5.3 Withdrawn

Druss 2010 reported on those "withdrawn" (n = 407, 1 RCT, RR 6.90, CI 0.86 to 55.56).

1.5.4 Discontinued

Brown 2009 provided data for those who 'discontinued' meaning they left for 'various personal reasons' (n = 26, 1 RCT, RR 8.25, CI 0.50 to 135.21).

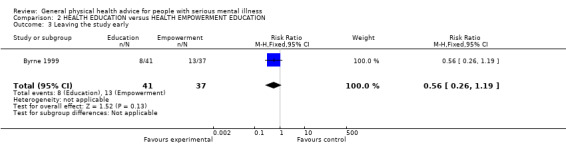

Comparison 2. Health education versus empowerment education

Byrne 1999 provided data for the comparison health education versus empowerment education.

2.1 Quality of life

There was no significant difference in quality of life as assessed on the Lehman Quality of Life scale (n = 51, 1 RCT, MD ‐0.30, CI ‐0.99 to 0.39, Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 HEALTH EDUCATION versus HEALTH EMPOWERMENT EDUCATION, Outcome 1 Quality of life: Average global score (Lehman Quality of Life scale, high = good).

2.2 Economic

There was no significant difference between groups for general health education versus empowerment education; however, these data are skewed and we report them in a table (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 HEALTH EDUCATION versus HEALTH EMPOWERMENT EDUCATION, Outcome 2 Economic: Total value of health resource consumption (dollars, low = good, skewed data).

| Economic: Total value of health resource consumption (dollars, low = good, skewed data) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean (US $) | SD | N |

| Byrne 1999 | Health education | 1432.03 | 2588.67 | 39 |

| Byrne 1999 | Health empowerment | 1476.51 | 2191.98 | 36 |

2.3 Leaving early

There was no significant difference in the number of participants leaving the study early (n = 78, 1 RCT, RR 0.56, CI 0.26 to 1.19, Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 HEALTH EDUCATION versus HEALTH EMPOWERMENT EDUCATION, Outcome 3 Leaving the study early.

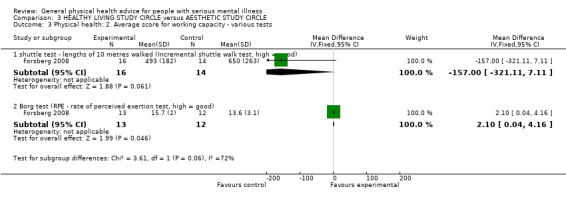

Comparison 3. Programme of healthy living in the form of a study circle versus aesthetic study circle

Forsberg 2008 provided data for the comparison programme of healthy living in the form of a study circle versus aesthetic study circle.

3.1 Physical health behaviour

There was an increase in physical activity (steps per day) in the intervention group, but no significant difference was reported. These data, however, are skewed and we report them in a table (Analysis 3.1). Additionally, the method of measurement, the Silva pedometer, had been discredited as an "unacceptably inaccurate" activity promotion tool, due to its lack of testing.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 HEALTHY LIVING STUDY CIRCLE versus AESTHETIC STUDY CIRCLE, Outcome 1 Physical health behaviour: Average steps per day (high = good, skewed).

| Physical health behaviour: Average steps per day (high = good, skewed) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | n | Notes |

| Forsberg 2008 | Healthy living study circle | 5586 | 3313 | 9 | Clustered data ‐ but analysed as non‐clustered in report. |

| Forsberg 2008 | Aesthetic study circle | 6487 | 2743 | 8 | Clustered data ‐ but analysed as non‐clustered in report. |

3.2 Physical health ‐ metabolic syndrome

There was no significant difference in the presence of metabolic syndrome (n = 13, 1 RCT, RR 1.25, CI 0.35 to 4.49, Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 HEALTHY LIVING STUDY CIRCLE versus AESTHETIC STUDY CIRCLE, Outcome 2 Physical health: 1. Metabolic syndrome ‐ present.

3.3 Physical health ‐ physical working capacity

3.3.1 Incremental Shuttle Working Test

In the control group there was a non‐significant increase in physical working capacity measured by the Incremental Shuttle Working Test (n = 30, 1 RCT, MD ‐157.00, CI ‐321.11 to 7.11, Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 HEALTHY LIVING STUDY CIRCLE versus AESTHETIC STUDY CIRCLE, Outcome 3 Physical health: 2. Average score for working capacity ‐ various tests.

3.3.2 Borg Exertion Test

In the control group there was a very slight decrease for the Borg Exertion Test (n = 25, 1 RCT, MD 2.10, CI 0.04 to 4.16).

3.4 Physical health: various continuous data

3.4.1 Metabolic criteria

Forsberg 2008 reported that at 12 months follow‐up among residents, the only significant change was a decrease in the mean number of metabolic criteria in the intervention group. Residents had decreased their mean number of metabolic criteria at the follow‐up and the number of with metabolic syndrome had decreased from 13 to 10; however, these data are skewed and are reported only as a table (Analysis 3.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 HEALTHY LIVING STUDY CIRCLE versus AESTHETIC STUDY CIRCLE, Outcome 4 Physical health: 3. Various continuous data (skewed).

| Physical health: 3. Various continuous data (skewed) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | n | Notes |

| metabolic syndrome ‐ average criteria score | |||||

| Forsberg 2008 | Healthy living study circle | 2.24 | 1.44 | 21 | Clustered data ‐ but analysed as non‐clustered in report. |

| average risk of fatal cardiovascular disease ‐ at present (Heart Score, high = good, skewed data) | |||||

| Forsberg 2008 | Healthy living study circle | 0.86 | 1.07 | 21 | Clustered data ‐ but analysed as non‐clustered in report. |

| average risk of fatal cardiovascular disease ‐ by 10 years (Heart Score, high = good, skewed data) | |||||

| Forsberg 2008 | Healthy living study circle | 4.67 | 3.9 | 21 | Clustered data ‐ but analysed as non‐clustered in report. |

3.4.2 Fatal cardiovascular disease

There was no significant difference in the initial risk of fatal cardiovascular disease between the intervention and the control groups; however, these data are skewed and are reported only as a table.

3.4.3 10‐year risk Heart Score

There was no significant difference in the 10‐year risk Heart Score between the intervention and the control groups; however, these data are skewed and are reported only as a table.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included seven studies with a total number of 1113 participants. Only Comparison 1 included more than one study. Across the six studies which reported data for leaving early, the attrition rate was 32%. Some studies had significant potential for influence from industry (Brown 2006; Brown 2009; Druss 2010). Much data were often reported in such a way as to make comparative analyses impossible and we were unable to report data for many outcomes These factors must be a threat to the validity, or at the very least, the credibility of results (Xia 2009).

1. Comparison 1: Physical health advice versus standard care

Most studies we identified were included in this comparison (6 RCTs, n = 964). There was, however, an attrition of 32% (Table 1).

1.1 Physical health behaviour