Abstract

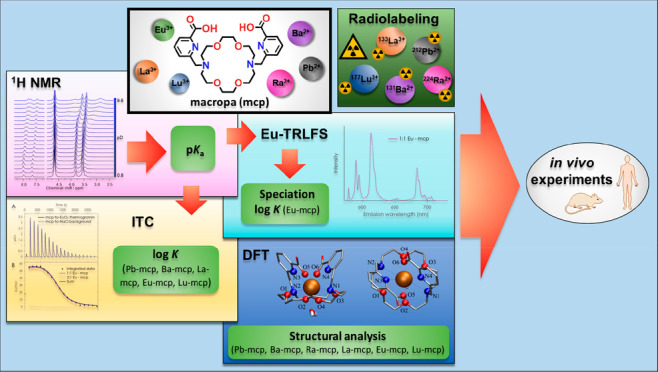

To pursue the design of in vivo stable chelating systems for radiometals, a concise and straightforward method toolbox was developed combining NMR, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), and europium time-resolved laser-induced fluorescence spectroscopy (Eu-TRLFS). For this purpose, the macropa chelator was chosen, and Lu3+, La3+, Pb2+, Ra2+, and Ba2+ were chosen as radiopharmaceutically relevant metal ions. They differ in charge (2+ and 3+) and coordination properties (main group vs lanthanides). 1H NMR was used to determine four pKa values (±0.15; carboxylate functions, 2.40 and 3.13; amino functions, 6.80 and 7.73). Eu-TRLFS was used to validate the exclusive existence of the 1:1 Mn+/ligand complex in the chosen pH range at tracer level concentrations. ITC measurements were accomplished to determine the resulting stability constants of the desired complexes, with log K values ranging from 18.5 for the Pb-mcp complex to 7.3 for the Lu-mcp complex. Density-functional-theory-calculated structures nicely mirror the complexes’ order of stabilities by bonding features. Radiolabeling with macropa using ligand concentrations from 10–3 to 10–6 M was accomplished by pointing out the complex formation and stability (212Pb > 133La > 131Ba ≈ 224Ra > 177Lu) by means of normal-phase thin-layer chromatography analyses.

Short abstract

Complexes formed by the chelator macropa and the metal ions of La, Eu, Lu, Pb, and Ba were analyzed by NMR, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), europium time-resolved laser-induced fluorescence spectroscopy (Eu-TRLFS), and density functional theory to determine the pKa values for macropa (2.40, 3.13, 6.80, and 7.73) and the stability constants (log K) of the respective complexes (Pb-mcp, 18.5; La-mcp, 13.9; Eu-mcp, 13.0; Ba-mcp, 11.0; Lu-mcp, 7.3). Additionally, structural information was obtained, and radiolabeling of macropa with selected radionuclides was realized with a complex stability gradation in the order of 212Pb > 133La > 131Ba ≈ 224Ra > 177Lu.

1. Introduction

Radiometals and especially the design of chelating systems to create stable radiometal complexes continue to be an important element of radiopharmaceutical development for both diagnostic and therapeutic applications in nuclear medicine.1,2 Since the development of technetium-99m as a still-dominating diagnostic radionuclide and the emergence of the 99Mo/99mTc generator in the 1960s,3 several radiometal-based nuclides have been identified and implemented as potential radiopharmaceuticals.4 A critical aspect of radiometal-based radiopharmaceuticals is their stability under in vivo conditions. The radiometal-coordinating ligand is the key to determining the radiometal complex stability. Release of the radiometal ion should be avoided to prevent the accumulation of free radiometal in vivo (off-target accumulation).5 So far, no single chelator is known to be ideal for all metals or radioconjugates. Hence, discovering appropriate complexation systems is of unabated interest. The precise determination of the thermodynamic association constants (log K) allows the prediction of in vivo stability of radiometal complexes at the radiotracer level. In addition, thermodynamic studies can help to identify conditions under which the desired thermodynamic product dominates over a possibly less stable kinetic product. It should be noted that the kinetic stability of the complex formed cannot be directly determined from complex formation constants because the complex formation constant corresponds to the ratio of the association and dissociation rates.

The stability of the radiometal complex in vivo is not just influenced by the chelator.6 Moreover, the biodistribution and clearance are affected as well. In this regard, the net charge and hydrophilicity of the resultant radiometal conjugate have an impact, which has been shown for Cu2+ complexes conjugated to the same targeting moiety.7−10 It is therefore important to search for appropriate chelators to match both the radiometal and biological target in order to obtain the best target-to-nontarget uptake ratio of the radiopharmaceutical for either imaging or therapy. Mostly, encapsulation by the multidentate and macrocyclic chelator 2,2′,2″,2‴-(1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetrayl)tetraacetic acid (DOTA) as the most used standard ligand is required.11 It works well for radiometals, namely, 43/44/47Sc, 177Lu, 111In, and 67/68Ga, but it is not the best choice for other radiolanthanides like 133La or radioactinides like 225Ac and even worse for radionuclides from main group 2 metals such as 90Sr, 131Ba,12 and 223/224Ra.13

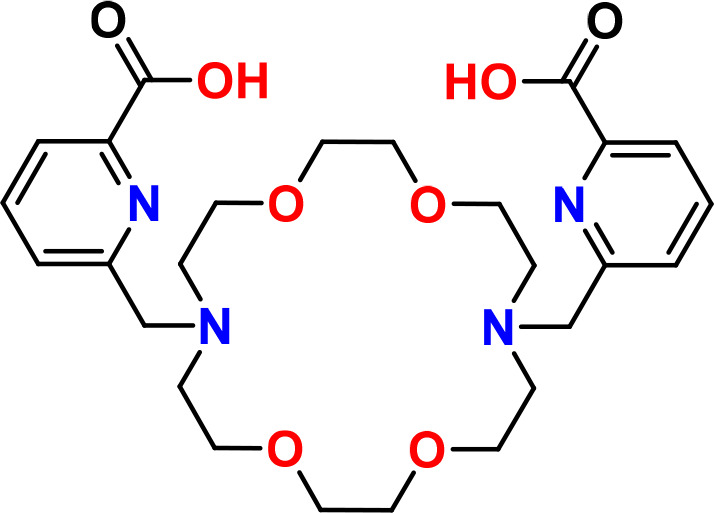

Macropa (mcp) as a macrocyclic chelator, originally known as H2bp18c6 and invented for actinide and lanthanide separation,14,15 with two pendant picolinic side arms (Figure 1) has entered the field of radiopharmaceutical sciences especially for the complexation of 225Ac,16−18133La,19213Bi,20,21131Ba,22 and 223/224Ra.23 Macropa’s superiority over DOTA in forming highly stable complexes with the trivalent cation of 225Ac has been shown.24 Moreover, water-soluble complexes with divalent cations of barium25 and radium23 in conjunction with macropa are known. Due to the lack of stability data for macropa-derived complexes, especially for radiopharmaceutical in vivo applications, extensive research on new chelating systems, combined with precise analytical methods for the log K determination, is still necessary.

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of the macropa chelator.

Various attempts were made in the past to determine the complex stability of the (radio)metal complexes. Different analytical methods are known to generally measure the association constants such as UV/vis titration, potentiometry, or NMR titrations.11 However, these methods are sometimes carried out at their limit of validation.26−28 The often low concentration of either the (radio)metal or the ligand falls below the limit of detection for these methods. Other standard methods like UV/vis or NMR are not appropriate for Ra2+ because a high amount of metal salt is required. Additionally, radiochemical two-phase extractions are not suitable due to the high solubility of the complexes in aqueous media.

To overcome these obstacles, our aim was to establish a reliable method toolbox consisting of a combination of NMR, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), and europium time-resolved laser-induced fluorescence spectroscopy (Eu-TRLFS) for the accurate determination of association constants for complexes formed with macropa and selected cations. The latter thereby comprise Pb2+ and Ba2+ as well as the (radio)lanthanides La3+, Eu3+, and Lu3+, which are commonly applied as radiometal ions for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in radiopharmaceutical applications (except of Eu3+). Moreover, measurements with concentrations in the micromolar range are possible, enabling a more realistic prediction of the radiopharmaceutical’s behavior at tracer-level concentrations.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Synthesis and Preparation of Solutions

All chemicals were used without further purification. The synthesis of the macropa ligand was accomplished according to published methods.14,29 NMR samples were prepared with deuterated solvents (Deutero) D2O (99.95% D) as well as D2O solutions of both DCl (38% in D2O with 99% D) and NaOD (40% in D2O with 99% D) to adjust the pD using a pH meter (VWR pHenomenal MU 6100 L) equipped with a pH electrode (WTW SenTix Mic) and corrected for deuterium according to the common relationship pD = pH meter reading + 0.4.30 A stock solution of 2 mM macropa and 0.2 M NaCl was prepared by weighing and dissolving the required amounts in D2O. Samples were prepared by taking 1 mL of the stock solution and adjusting the pD and total volume to 2 mL to finally yield samples of 1 mM macropa and 0.1 M NaCl, with a pD range from 0.8 to 9.6.

The samples for TRLFS and ITC were prepared at 25 °C with an ionic strength of NaCl set to 0.1 M. For all samples, the pH was adjusted using NaOH and HCl and a pH meter (VWR pHenomenal MU 6100 L) equipped with a pH electrode (WTW SenTix Mic).

2.2. NMR Spectroscopy

All NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C using Agilent DD2-600 and 400MR DD2 systems, operating at 14.1 and 9.4 T, with corresponding resonance frequencies of 599.8 and 399.8 MHz for 1H and 150.8 and 100.6 MHz for 13C, respectively, using 5 mm NMR probes. 1H NMR spectra were measured by accumulating 16–128 scans, depending on the concentrations and line widths, using 2 s of acquisition time and a relaxation delay, respectively, applying a 2 s presaturation pulse on the water (HDO) resonance for water signal suppression. NMR spectra were processed with MestReNova, version 14.2.3 (Mestrelab Research SL).31 The creation of graphs for numerical data visualization and data fitting by nonlinear sigmoidal dose–response fit algorithm were performed with Origin 2020, version 9.7.0.185 (OriginLab Corp.). Furthermore, macropa complexes of La3+, Eu3+, Lu3+, Pb2+, and Ba2+ were prepared.

2.3. TRLFS

For TRLFS, a pulsed Nd:YAG-OPO laser system (Ekspla, NT230, 50 Hz, ∼5 ns pulse, 1.1 mJ/pulse) with an excitation wavelength of 394 nm was used. For the detection of Eu3+ luminescence, an Andor iStar ICCD camera (Lot-Oriel Group) connected to the rear end of a spectrograph (Oriel MS 257 monochromator, a 300 lines/mm grid, a gate width of 300 μs) was used. The luminescence decay was detected by measuring 21 different temporal offsets to the laser beam using a linearly increasing step size [7 + 7x (μs), 0–1610 μs] and an initial delay of 12 μs to suppress emission from higher states (5D1). Five solutions with 10 μM EuCl3 and 10 μM macropa in a 0.1 M NaCl solution in the pH range from 1.7 to 11.6 were prepared. Furthermore, for titration, a 500 μM macropa with 10 μM EuCl3 (0.1 M NaCl) solution and a 10 μM EuCl3 (0.1 M NaCl) solution at pH 3.5 were prepared.

In addition to the measurement at ambient temperatures, samples (10 μM EuCl3, 25 μM macropa, I = 0.1 M NaCl, pH 5) were measured under cryogenic conditions (<40 K, a closed-cycle helium refrigerated cryostat). The above-described laser system was used for excitation. Emission detection was performed with different grids (300, 600, and 1200 lines/mm). Due to longer lifetimes, the linear increasing step size was set to 15 + 15x (μs) [0–3450 μs].

All TRLFS data sets were analyzed by parallel factor analysis (PARAFAC) using an implemented N-way toolbox32 for MATLAB with modifications as previously described.33,34 The luminescence decays of individual species were constrained to be exponential, and the species distribution had to reflect a speciation of the Eu-macropa system. The pKa values of macropa, which were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy, were considered for the speciation calculation to extract complex stability constants log K.

2.4. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

MicroCal PEAQ-ITC (Malvern Panalytical) with a cell volume of approximately 200 μL was used for calorimetry. The titrant was injected into the sample cell by an automated syringe (40 μL) at 25 °C under continuous stirring (750 rpm) and was titrated in 0.5–2 μL steps in 19 aliquots with a time interval of 150 s into the sample cell. The syringe was filled with 500 μM macropa in a 0.1 M NaCl solution, and the sample cell contained 50 μM metal in a 0.1 M NaCl solution at the same specific pH (±0.1). An analogous setup without metal was used as the background measurement.

ITC data where analyzed using a MATLAB code based on speciation calculations35 and equations (e.g., displaced volume) provided by Malvern. Unless otherwise stated, the data were evaluated globally. The estimation of errors and the goodness of the model was performed with a Monte Carlo approach as previously described.36

2.5. Radiolabeling

Caution!212Pb, 133La, 131Ba, 224Ra, and 177Lu, and their radioactive decay products, represent α-, β-, and γ-emitting radionuclides. Special attention should be paid when working with unsealed radionuclides to avoid unnecessary contamination and incorporation. Only persons who are adequately trained or experienced are allowed to work with radioactive material in laboratories that are authorized to use radioactive material. Hence, all studies with these radionuclides were conducted in laboratories equipped with continuous air monitors, fume hoods (certified), and monitoring equipment appropriate for α-, β-, and γ-radiation detection. Entrance to the laboratory space (controlled area) was controlled with a hand and foot monitoring instrument for α-, β-, and γ-emitting isotopes and a personnel contamination monitoring station.

The production of 131Ba and 133La was carried out at the TR-FLEX (ACSI) cyclotron at HZDR and is described elsewhere.22,37177Lu was commercially supplied by ITM as a [177Lu]LuCl3 solution. 224Ra and 212Pb were obtained from the 228Th/224Ra generator, as described elsewhere.38,39 Radiolabeling was performed using 100 kBq of 131Ba, 133La, 224Ra, 212Pb, or 177Lu. The respective ligand stock solution (10–2–10–4 M) in 0.2 M NH4OAc buffer (pH 6) was used to reach the required ligand concentration (10–3–10–6 M). For comparability, all reaction mixtures were maintained at 25 °C for 1 h in a thermomixer at 600 rpm. Once the labeling reaction was finished, samples were taken out and analyzed via radio-TLC [thin-layer chromatography; two systems: normal phase –50 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; pH 7) on silica plates and normal phase (cyano-modified)–70:30 acetonitrile/water on Alugram-CN plates].17 Radio-TLC plates were imaged by radiation-sensitive imaging plates and scanned by an Amersham Typhoon 5 (GE Healthcare).

2.6. Computational Calculations

Geometry optimizations using density functional theory (DFT) were performed in Orca 5.0.3 to investigate the 1:1 complex of Ba2+, La3+, Eu3+, Lu3+, Pb2+, and Ra2+ with the macropa ligand, accompanied by a single water molecule within the coordination sphere.40 The initial geometries were extracted from crystal structures exhibiting 10 coordinative bonds between the central atom and the macropa ligand.14,25,41 Implicit solvation with water was incorporated using the conductor-like polarizable continuum model.42 The PBE0 hybrid functional was employed, along with two distinct basis sets.43,44 For the alkaline-earth metals Ba2+ and Ra2+, the aug-cc-pvTZ-DK3 all-electron basis set was utilized in conjunction with the DKH-def2-TZVPP basis set for all atoms except the metal centers.45 On the other hand, the def2-TZVPP basis set with effective core potentials for the central atoms was employed for optimizations involving La3+, Eu3+, Lu3+, and Pb2+.46 In contrast to the total energy of certain complex structures, the geometry information is comparable for calculations with different basis sets. Therefore, structural and visual analyses were performed after the DFT optimizations with VMD 1.9.3.47 It is noteworthy that using the same basis set for all metal complexes consistently led to convergence difficulties in the self-consistent-field calculations. Subsequent to the geometry optimization, a numerical vibrational frequency analysis was conducted for the Ba2+ and Ra2+ complexes, while an analytical approach was employed for the La3+, Eu3+, Lu3+, and Pb2+ complexes. This analysis ensured the absence of imaginary frequencies, thereby confirming the attainment of a local energy minimum.

3. Results and Discussion

Spectroscopic techniques, which are excellently applicable for studying (aqueous) complex formation from both the organic ligand and (luminescent) metal-ion perspectives, are combined with calorimetry to benefit from each method’s advantages to finally identify the real species along with their molecular structures and to obtain the corresponding reliable thermodynamic data.48 A prerequisite to obtaining robust thermodynamic constants is the determination of reliable pKa values of the ligand. For this purpose, 1H NMR spectroscopy was used. Advantageously, structure-related information is provided by covering a wider pH range. For example, the determination of a pKa value of about 1 is hardly feasible in potentiometric or calorimetric titrations because the detectability of the abstracted proton is poor against background H+ concentrations ranging between 0.1 and 1 M corresponding to pH values between 1 and 0, respectively. Also, NMR’s structure sensitivity allows for an assignment of abstracted H+ to the corresponding protolytic site. Additionally, the pH-dependent behavior of the ligand–Eu3+ system was investigated by TRLFS in order to verify the exclusive existence of one single pH-independent 1:1 mcp/metal complex. The suitable pH value for the concentration titrations to determine log K was established. The latter was then determined complementarily using ITC and TRLFS. The strength of these two methods is the extremely high sensitivity enabling experiments with analyte concentrations in the micromolar concentration range.

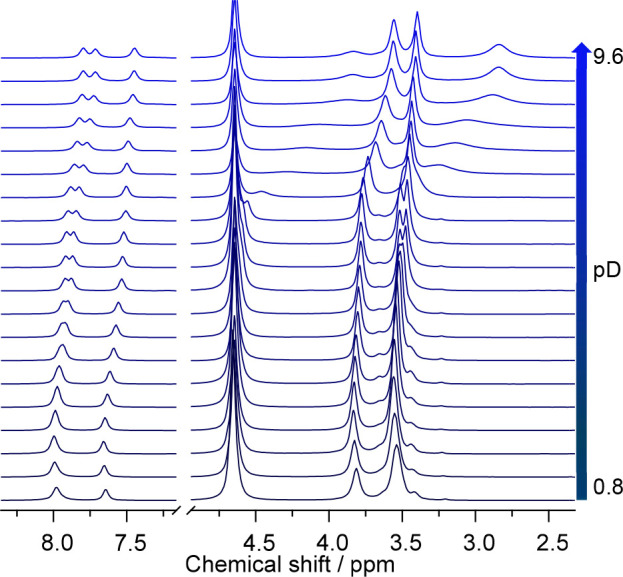

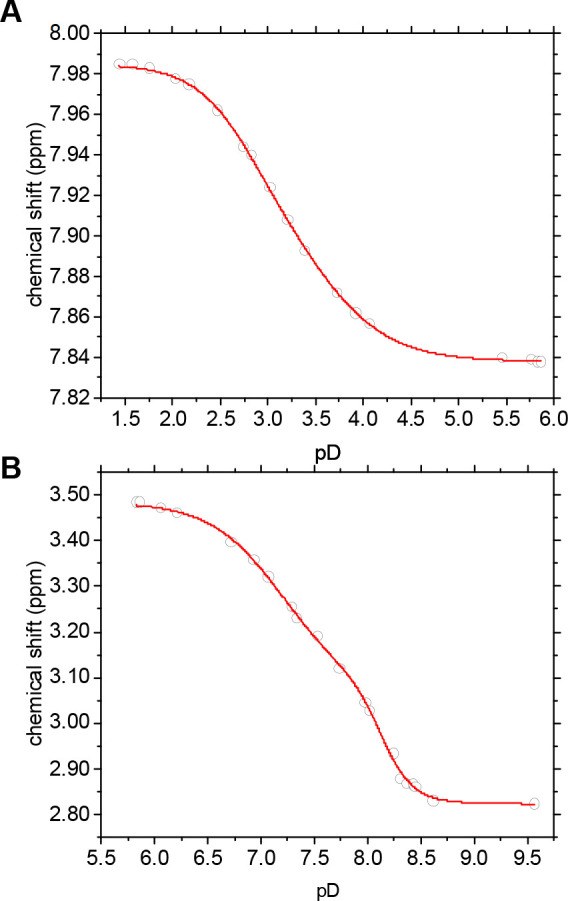

3.1. pKa Determination by NMR Spectroscopy

To ascertain the protonation–deprotonation regime of macropa as a chelating system, pKa values of the functional groups were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy. This allows a good assessment of a pH range for the later TRLFS and ITC measurements. For the pKa determination, samples with 1 mM macropa in a 0.1 M NaCl D2O solution covering the pD range from 0.8 to 9.6 were prepared. pKa values of the ligand were determined according to procedures successfully applied to other ligand systems.48−50

Upon increasing pH, a successive ligand deprotonation takes place, resulting in a general upfield shift of the signals due to the higher electron density remaining with the ligand caused by the increasing anionic charge (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

1H NMR pD-titration series of the macropa ligand obtained from 1 mM ligand in 0.1 M NaCl aqueous D2O solutions at (25 ± 1) °C in the pD range of 0.8–9.6 (from bottom to top). For clarity, only selected spectra and spectral regions of interest are shown. For better visualization of the broad signals, an exponential line broadening factor of 20 Hz was applied. The signal at 4.65 ppm is the residual HDO resonance, partly obscuring the benzylic methylene 1H signal.

The variable line widths (signal width at half-amplitude) are strong indicators of kinetic processes associated with protonation/deprotonation reactions. Especially, the signals of 1H nuclei in the direct vicinity reveal significant broadening at the pH range close to the amines’ pKa values. The four inflections observed for ligand titration, in agreement with Roca-Sabio et al.,14 refer to two protons abstracted from the carboxylic groups in acidic media as well as two protons abstracted from the macrocyclic ring amine nitrogen atoms (ammonium form) under nearly neutral-to-alkaline conditions. 1H NMR titration data were evaluated in the corresponding δH versus pD plots by means of sigmoidal (bi)dose–response fit functions, as shown in Figure 3, with the respective inflection points representing pKa values.

Figure 3.

Graphs of pD-dependent 1H NMR chemical shift values (grey circles) based on the spectra shown in Figure 2, along with sigmoidal bidose–response fits (red lines) for pKa determination. Signals associated with the aromatic residue (A) and macrocycle (B) are used as representative molecular probes to monitor the abstraction of protons from the carboxyl groups and amine nitrogen atoms, respectively.

In order to correct the deuterium isotope effect in the pKa value determination, a constant value of 0.4 was subtracted to obtain the pKa values comparable to water solutions, according to the linear term in the pD determination from a pH meter reading.51 Determined pKa values are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Determined Deuterium-Corrected pKa Values of Macropa Obtained from NMR Spectroscopy at an Ionic Strength of I = 0.1 M NaCl in Comparison to the Literature Data.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H4L2+ → H3L+ | H3L+ → H2L0 | H2L0 → HL– | HL– → L2– | |

| pDa (D2O) | 2.80 | 3.53 | 7.20 | 8.13 |

| pKaa | 2.40 | 3.13 | 6.80 | 7.73 |

| pKa(lit.)b,(14) | 2.36 | 3.32 | 6.85 | 7.41 |

Estimated error values of ±0.15, considering the uncertainties arising from the pH electrode including temperature effects during calibration and measurement.

Potentiometric titration (I = 0.1 M KCl).

3.2. Investigations of the Eu-mcp Complex by TRLFS

Thermodynamic investigations of metal complexes with high-affinity ligands reveal intrinsic difficulties. The affinity of the completely deprotonated ligands toward the metal ion of interest is in the range for which a useful concentration regime is below the detection limits of most spectroscopic techniques for direct measurement of the complex formation constants. The resulting species distributions consist of a linear increase in the complex concentration followed by a kink and a plateau (Figure S5). This fast saturation is not suitable for the direct determination of the complex formation constants because it does not allow for correct measurement of the equilibrium free metal concentration required for the law of mass action. Our approach is to perform the experiment at a lower pH, reducing the ligand’s affinity because of competition between the metal ion and protons for the functional groups. In that case, a direct accessibility of the log K values of these high-affinity ligand complexes is possible. Thus, it must first be validated that the complex under investigation remains stable in the considered pH range (Figure S4). The experiments were repeated at pH 3.5 with a reduced affinity of the ligand, leading to a smooth asymptotic saturation (Figure S6). By utilizing the exact pKa values (Table 1), it is now possible to determine the log K values in a suitable concentration range, as previously demonstrated for nitrilotriacetic acid, EDTA, and ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid.48

3.3. Thermodynamic Investigations by TRLFS and ITC

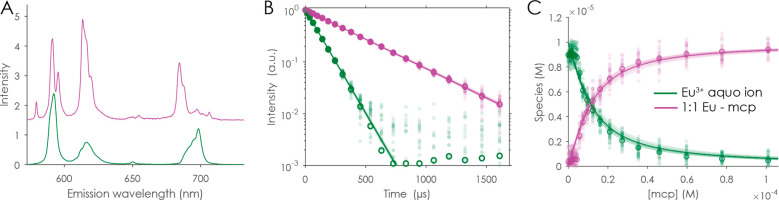

The combination of the discussed TRLFS titration of macropa to the Eu3+ solution at pH 3.5 and measurement of the pKa values by 1H NMR allowed the determination of the complex stability constant of the Eu-mcp complex with log KEu-mcp = 12.9 (Figure 4), which is in perfect agreement with the literature data (log K = 13.0) obtained by from potentiometric titration.14

Figure 4.

PARAFAC results of mcp titration (0–112 μM) to 10 μM EuCl3 in 100 mM NaCl at pH 3.5. Besides the Eu3+ aquo ion (green), the Eu-mcp complex (magenta) is clearly identified. Because of PARAFAC’s trilinearity, the emission spectra (A), luminescence decay of the Eu3+ aquo ion (109 ± 1.2 μs), 1:1 Eu-mcp complex (385 ± 4 μs) (B), and speciation (C) were simultaneously determined. The shaded data points were artificially created to be used in a Monte Carlo approach for the error estimation of the underlying model.

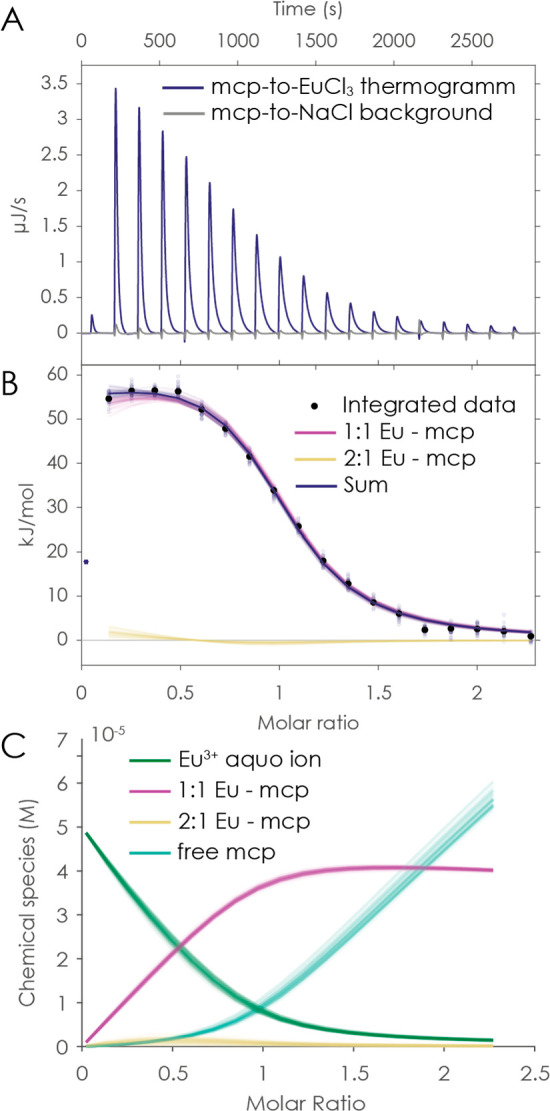

Additionally, the complex stability constant log K of the Eu-mcp complex was determined by ITC (Figure 4). Therefore, aliquots of a macropa solution were titrated to the Eu3+ solution at pH 3.5, as discussed previously and analyzed by including the pKa values from 1H NMR. The complex stability was determined as log KEu-mcp = 13.0, which is highly consistent with both the values obtained by TRLFS and those from the literature. This technique was subsequently used for the log K value determination of all other selected metal ions with the macropa ligand.

With the consistent data for the Eu3+ system, we generalized our approach for the selected nonluminescent metal ions Pb2+, La3+, Lu3+, and Ba2+ of radiopharmaceutical interest. Prior to the thermodynamic investigations, the identity of the formed Mn+-mcp complexes was validated by 1H NMR (Figure S1) and compared with those reported.14,25,41 Based on the pKa determination by NMR, the pH dependency of macropa’s affinity to different metal ions had to be fine-tuned by pH adjustment to determine the thermodynamic data. A pH value of 2 was used for Pb2+, whereas a pH of 3.5 was applied for La3+ and pH 5 was used for Ba2+ and Lu3+. By comparing the thermograms, an obvious difference between the lanthanides (Figures 5, S6, and S7) and main-group metals (Figures S8 and S9) was apparent. In the thermograms, an endothermic complexation reaction was found for the lanthanides, with heat being consumed, whereas for the other metals, an exothermic reaction was observed, with heat being released during complexation. The stripping of the hydration shell of the lanthanides compared to the complexation itself can be an explanation for this behavior.52 However, the expected 1:1 complex stoichiometry was verified for all of the Mn+-mcp complexes. The resulting complex stability constants log K, considering the pKa values of macropa, are shown in Table 2.

Figure 5.

ITC results for a titration of 500 μM macropa to 50 μM EuCl3 in 100 mM NaCl at pH 3.6. The integrated heat (B) of the thermograms (A) was fitted with an additional 2:1 Eu3+-mcp complex due to comparability to lanthanum ITC (see the Supporting Information). The underlying speciation is shown in part C.

Table 2. Complex Stability Constants (log K) of Selected Metal Ions and the Macropa Chelator (Determined at 25 °C; Ionic Strength of I = 0.1 M NaCl) Compared with the Literature-Known Data Obtained from Potentiometric Titration.

Additionally, the respective 2:1 Ln-mcp complexes (Ln = Eu, Lu, La) needed to be considered during the initial injections of the ITC titration (high excess of metal ion) to fit the data correctly. This is especially observed in the ITC data for the La-mcp complex (Figure S7). The underlying speciation is shown in Figure 5C. However, these 2:1 Ln-mcp complexes play only a very minor role for consideration of the thermodynamic stability and no role at all for future applications in radiopharmaceuticals, where the metal is in deficit compared to the chelator.

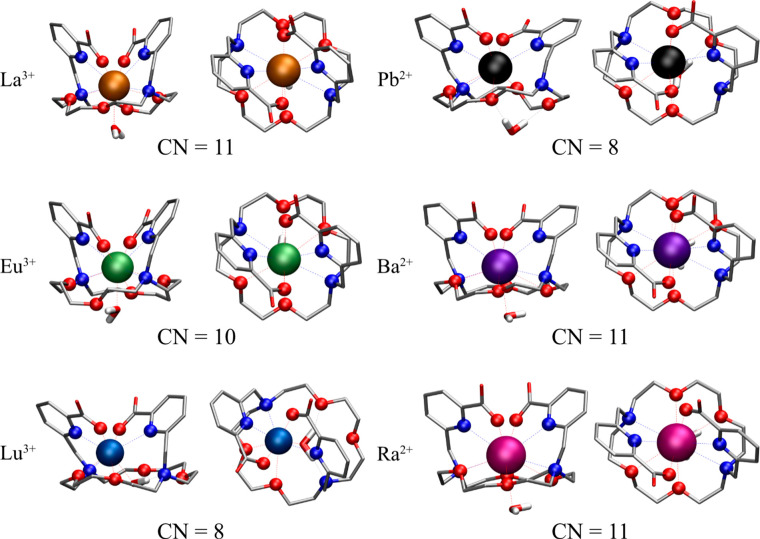

3.4. Structural Investigation of the Mn+-mcp Complexes

Over the past years, first DFT calculations with macropa complexes were performed on a high theoretical level.53−55 However, only a few metal complexes have been examined, so that general knowledge about the metal-dependent complexation of the macropa ligand is still missing. Therefore, mcp complexes with Pb2+, Ba2+, Ra2+, La3+, Eu3+, and Lu3+ were optimized to create a comparable pool of structures, with these heavy elements coordinating to the macropa ligand. In combination with information received from NMR and TRLFS, structure elucidation was possible.

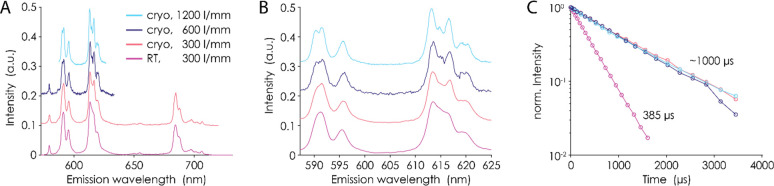

Such structural information about the complex can be obtained from the Eu emission spectra. This type of information requires high-quality spectra, which are prevented by various physical effects, such as Doppler broadening. Therefore, in addition to TRLFS at 25 °C, a sample containing EuCl3 (10 μM) and macropa (25 μM) was measured at T < 40 K. Under such conditions, the splitting pattern of the ligand-field level of the 7FJ terms can be fully resolved. The resolution of the emission can be further increased by the choice of the used grid.

By using the emission spectrum of the Eu-mcp complex (Figure 6), it is possible to probe the site symmetry. Especially, the J = 0, 1, 2 transitions of the 5D0 → 7FJ Eu3+ luminescence (Figure S3) were inspected closely and compared with the emission spectrum of the Eu3+ aquo ion. First of all, the 5D0 → 7F0 transition, which is symmetry-forbidden according to the Laporte selection rule,56 is visible in the macropa complex.

Figure 6.

Comparison of TRLFS at 25 °C and cryo-TRLFS of the Eu-mcp complex. (A) Emission spectra collected at different temperatures and using different grids. Generally, all emission spectra provide the same features so that the complex can be assumed to be temperature-stable. (B) Zoomed representation for the comparison of the F1 and F2 bands. It can clearly be seen, by decreasing the temperature, that more details are revealed. The maximum resolution is achieved using cryogenic conditions combined with the 1200 lines/mm grid (light blue). The three- and five-times splittings are attributed to the F1 and F2 band, respectively. (C) Lifetime of the Eu emission assumed to be temperature-independent. However, in our case, the emission lifetime significantly increases to around 1 ms under cryogenic conditions.

In Figure 6B, it is pointed out that the 5D0 → 7F1 transition is split 3-fold. Furthermore, a 5-fold splitting of the 5D0 → 7F2 transition is clearly visible using the best resolution grid under cryogenic conditions. The splitting patterns of these two transitions cannot be resolved under ambient conditions. The 5D0 → 7F4 transition shows the most significant change in the emission spectra. It can split up to a maximum of 9, and a low-energy J level of the macropa complex provides the highest probability. In summary, the splitting patterns of the 7F0, 7F1, and 7F2 transitions of the Eu-macropa complex are representative to a low-symmetry class such as C2 or lower.57−59

Additional information about the complex structure is given by the luminescence decay time of the Eu3+ complex. The energy transfer from the excited metal to the OH oscillators represents an efficient quenching mechanism of Eu3+. On this basis, an empirical equation was established [so-called Horrocks equation: n(H2O) ± 0.5 = 1.05/τ – 0.44] to estimate the number of water molecules in the first coordination sphere of Eu3+.60−62

While the determined lifetime of the Eu-mcp complex at 25 °C is quite short (∼385 μs) and suggests about two water molecules remaining in the coordination sphere, the lifetime increases significantly to ∼1 ms under cryogenic conditions. This value suggests 0 or 1 remaining water molecule and seems more realistic for the highly coordinating ligand. The standard quenching of OH oscillators should be temperature-independent. Significant changes in the luminescence decay are therefore indicative of structural changes. However, the emission spectra are fully conserved. It is likely that, because of the unique multidentate cage structure, at ambient temperatures additional quenching effects arising from, e.g., CH2 oscillators, add to the regular quenching mechanism from OH oscillators.

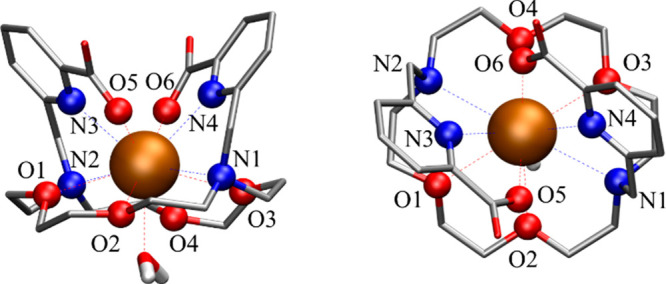

Structural analysis of the complexes using DFT calculations reveals distinct coordination characteristics for different metal ions. In the case of Ba2+, La3+, and Ra2+, the macropa ligand retains the coordination type observed in the crystal structures of certain Mn+-mcp complexes.14,25,41 A total of four nitrogen atoms and six oxygen atoms are involved in the coordination between the metal center and ligand. Additionally, one water molecule is involved in the first coordination sphere. In contrast, the water molecule in the Pb-mcp complex exhibits a different behavior. Instead of coordinating to the metal center by its oxygen atom, it rather features a second-shell explicit ligand hydrogen-bonded to two oxygen atoms of the macropa ligand.

A coordination number (CN) of 10 was found for Eu3+ complexed by the macropa ligand, with one coordination site occupied by an explicit water molecule. Thus, unlike the complete coordination observed in the macropa complexes Ba2+, Ra2+, and La3+, one oxygen atom of the macropa ring is not involved. The presence of an explicit water molecule fits very well with the luminescence lifetime under cryogenic conditions. The symmetry of the DFT-optimized complex of Eu3+ with macropa is slightly disturbed compared to that of the La3+ complex and thus agrees well with the results of cryo-TRLFS. In the case of Lu3+, only 7 out of the possible 10 donor atoms of the macropa ligand participate in the complexation. The remaining water molecule in this complex acts as a bridge between certain heteroatoms in the macropa ring and the metal center, resulting in a total CN of 8 for the Lu-mcp complex. As a borderline cation according to the hard–soft acid–base concept, Pb2+ is found in complexes with CNs between 2 and 10.39,63 In the case of Pb-mcp, a total CN of 8 was found, which is also observed in Pb complexes of DOTA, DOTAM, or DTPA with high log K values of >18. One out of the four oxygen atoms and one of the nitrogen atoms of the aza-crown ether moiety found in macropa do not participate. Due to the flexibility of this ring, together with the two picolinate residues that embed the Pb2+, a highly stable coordination is possible.

In terms of coordination with the macropa ligand, all of the complex structures appear to be similar. The metal ion is located above the plane of the macrocyclic ring system and is enclosed by both picolinic residues from above the plane. However, the CNs of the metal ions range from 8 to 11, while the hapticity of the mcp ligand ranges from η7 to η10, resulting in complex structures of different symmetry. A slightly reduced η9 coordination was found for the Eu-mcp complex, binding one less oxygen atom. Remarkably, the Pb-mcp complex is unique because its metal coordination is fully satisfied by the macropa ligand itself and requires no additional water molecule in the first coordination sphere. However, within the threshold of 3.4 Å defined as a coordinating bond, DFT calculations imply that one ether oxygen and one amine nitrogen of the macrocycle are not coordinating (η8); cf. Table 3 and Figures 7 and 8.

Table 3. Binding Distances M–X (Å) of the [M(mcp)(H2O)](m−2)+ Complexes (M = Ba2+, La3+, Eu3+, Lu3+, Pb2+, and Ra2+) in Aqueous Solutionsawith Atom Assignment in the Macropa Structure Shown in Figure 8.

| (M−)X |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb–X | Ba–X | Ra–X | La–X | Eu–X | Lu–X | |

| O1 (mcp) | 3.09 | 3.00 | 3.07 | 2.84 | 2.72 | 2.37 |

| O2 (mcp) | 3.29 | 3.01 | 3.12 | 2.92 | 2.75 | 2.89 |

| O3 (mcp) | – | 2.93 | 3.19 | 2.83 | 2.97 | – |

| O4 (mcp) | 3.08 | 3.25 | 2.95 | 2.98 | – | – |

| N1 (mcp) | 2.91 | 3.02 | 3.10 | 2.98 | 2.89 | 2.57 |

| N2 (mcp) | – | 3.19 | 3.22 | 2.98 | 2.97 | – |

| O5 (mcp) | 2.39 | 2.70 | 2.72 | 2.44 | 2.29 | 2.17 |

| O6 (mcp) | 2.35 | 2.70 | 2.78 | 2.45 | 2.32 | 2.19 |

| N3 (mcp) | 2.54 | 2.88 | 2.88 | 2.70 | 2.54 | 2.37 |

| N4 (mcp) | 2.71 | 2.85 | 2.94 | 2.70 | 2.57 | 2.66 |

| O (H2O) | – | 2.96 | 3.10 | 2.59 | 2.45 | 2.25 |

| estimated total CN | 8 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 8 |

Atom pairs with distances above 3.4 Å are considered to form no coordinative bond and are marked with “–”.

Figure 7.

Side and top views of geometry-optimized [M(mcp)(H2O)](m−2)+ complexes (Pb2+, Ba2+, Ra2+, La3+, Eu3+, and Lu3+) in aqueous solutions and the metal CNs.

Figure 8.

Side and top views with the atom labeling of macropa in the example of the [La(mcp)(H2O)]+ complex.

Similarly, a notable decrease in coordination (η7) was found for the Lu-mcp complex, interacting with three less donor atoms in the macropa ligand. Additionally, the Lu-mcp complex exhibits asymmetry due to the added water molecule occupying a position between the metal center and macropa ligand, bridging the coordination. This observation arises from the small size of the Lu3+ ion, which prevents it from accommodating the full 10-fold coordination of the macropa ligand. Along the series of La3+, Eu3+, and Lu3+, i.e., for decreasing ionic radius, the complexes’ asymmetry increases with decreasing binding affinity.14

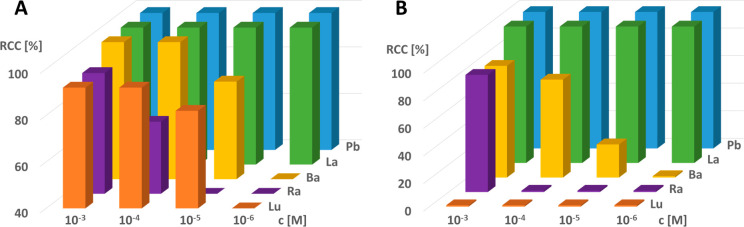

3.5. Radiolabeling

The macropa chelator was reported as a well-working complexing agent for 225Ac64 and, to the best of our knowledge, is the best chelator for 223/224Ra23,65 so far, but it is not ideal. Moreover, there is still a lack of suitable diagnostic radionuclides for these α emitters. For this purpose and to close this gap, the production and purification of 131Ba22 and 133La37 was established. Additionally, a new theranostic radionuclide pair was recently reported with 203Pb and 212Pb66,67 but is mainly used in DOTA-related chelating systems.39 For completeness, the therapeutic β-emitter 177Lu68 was also used for radiolabeling in this study. To compare the different radionuclides, 100 kBq of 212Pb, 133La, 131Ba, 224Ra, and 177Lu were incubated with different concentrations of macropa (10–3, 10–4, 10–5, and 10–6 M) for 1 h at 25 °C. Two normal-phase TLC systems were used to determine the radiochemical conversion (RCC).17 The first TLC system was designed to monitor the radiochemical conversion of radiolabeling, whereas the second system was developed to test the stability of the complex against other complex agents by challenging the complex with a 50 mM EDTA solution. In this case, the free radionuclide moves with the solvent front (Figures S10 and S11). Concentration-dependent RCCs for the tested radiometal ions, which were calculated by using both TLC systems, are presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Radiolabeling of macropa with 177Lu (red), 224Ra (violet), 131Ba (orange), 133La (green), and 212Pb (blue) in a serial dilution of four concentrations. RCCs were determined after 1 h of reaction time at 25 °C: (A) normal phase, cyano-modified (eluent: 3:7 acetonitrile/water); (B) normal phase (eluent: 50 mM EDTA, pH 5.5).

A quantitative conversion was found for the radiolabeling of 212Pb with macropa. No free 212Pb was observed even at a concentration of 10–7 M at room temperature (Figure S11). Additionally, by challenging the 212Pb-mcp complex with an EDTA solution, no free 212Pb was observed. This finding is superior over the labeling with standard DOTA derivatives,39 which mostly requires higher temperatures. Such mild radiolabeling conditions are highly favorable for use with temperature-sensitive biological targeting molecules such as antibodies that degrade at elevated temperatures. These results indicate that macropa provides an effective coordination environment for radioisotopes of Pb. Next, quantitative formation of the [133La]La-mcp complex was achieved at concentrations up to 10–6 M. This finding is consistent with the labeling conditions and results of a [133La]La-mcp-PSMA radioconjugate37 and of the [225Ac]Ac-mcp complex17 reported recently. [131Ba]Ba-mcp was previously investigated as well22 but showed quantitative complex formation only until 10–4 M. When the complex was challenged with a 50 mM EDTA solution, a major fraction of 81% intact [131Ba]Ba-mcp complex at a macropa concentration of 10–3 M combined with an increase of free 133Ba with 19% was observed. Furthermore, at a macropa concentration of 10–5 M, 24% of stable complex was still visible after the challenge. In contrast to 131Ba, 224Ra was formed with only 92% conversion at a ligand concentration of 10–3 M. At a concentration of 10–4 M, only 71% 224Ra was converted.100 These findings are comparable with the results published by Abou et al.69 Finally, the [177Lu]Lu-mcp complex was observed at ligand concentrations of 10–3 and 10–4 M with approximately 92% RCC at the chosen labeling conditions. However, the complex was challenged with a EDTA solution, only free [177Lu]Lu3+ was observed at all investigated concentrations, and no stable [177Lu]Lu-mcp complex remained.

4. Conclusion

This paper covers an analytical method workflow for the precise determination of stability constants using NMR, ITC, and Eu-TRLFS to fully characterize complexes, even at low metal-ion concentrations, which is particularly relevant for radiopharmaceutical applications. This can be used in ligand investigation to make precise predictions for work in the radiotracer range for an easy comparison of different chelating systems regarding their metal coordination behavior. To verify the whole concept, the decadentate ligand macropa was used as a chelating compound. pKa values were determined as a prerequisite for determination of the final log K values. Eu-TRLFS was used to examine the Eu3+ speciation in the desired pH range, giving the first molecular insight by showing a 1:1 Mn+/mcp ratio of the formed complexes. Subsequently, ITC measurements were accomplished to obtain the log K values (Pb-mcp, 18.5; La-mcp, 13.9; Eu-mcp, 13.0; Ba-mcp, 11.0; Lu-mcp, 7.3). These values were supported by theoretical calculations and are also in excellent agreement with previously published data. Although DFT calculations were not aimed at calculating the thermodynamic quantities, structural features provide clues about the relative order of experimentally determined stability constants. Finally, the radiolabeling results with five selected radionuclides perfectly underpin the obtained thermodynamic data, demonstrating the highest RCC and the highest stability with 212Pb even to a ligand concentration down to 10–7 M followed by 133La, which shows results comparable to those of 225Ac as a theranostic matched pair. Macropa is able to complex 133Ba, 224Ra, and 177Lu as well, however, with lower stability, and hence requires higher ligand concentrations.

The radiolabeling results nicely reflect the determined complex stabilities, proving that macropa provides an effective chelating system for 212Pb, 133La, and 225Ac, even under mild radiolabeling conditions, which is essential for sensitive macropa-functionalized biomacromolecules like antibodies or proteins.

Acknowledgments

The cyclotron team of HZDR is gratefully acknowledged for providing the radionuclides used in this paper. Linda Belke (HZDR) is gratefully acknowledged for support during the syntheses. Dr. Marc Pretze (University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus Dresden) is gratefully acknowledged for his support during the radiolabeling experiments.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c01983.

1H NMR data of the macropa ligand and complexes, along with data obtained from TRLFS, ITC, and DFT calculations, as well as TLCs from radiolabeling (PDF)

Author Contributions

† These authors contributed equally.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Jurisson S.; Berning D.; Jia W.; Ma D. Coordination compounds in nuclear medicine. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 1137–1156. 10.1021/cr00019a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wadas T. J.; Wong E. H.; Weisman G. R.; Anderson C. J. Coordinating radiometals of copper, gallium, indium, yttrium, and zirconium for PET and SPECT imaging of disease. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2858–2902. 10.1021/cr900325h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards P.; Tucker W. D.; Srivastava S. C. Technetium-99m: An historical perspective. Int. J. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1982, 33, 793–799. 10.1016/0020-708X(82)90120-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya S.; Dixit M. Metallic radionuclides in the development of diagnostic and therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 6112–6128. 10.1039/c1dt10379b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A.; Giuliano C. J.; Palladino A.; John K. M.; Abramowicz C.; Yuan M. L.; Sausville E. L.; Lukow D. A.; Liu L.; Chait A. R.; Galluzzo Z. C.; Tucker C.; Sheltzer J. M. Off-target toxicity is a common mechanism of action of cancer drugs undergoing clinical trials. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaaw8412 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw8412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeglis B. M.; Houghton J. L.; Evans M. J.; Viola-Villegas N.; Lewis J. S. Underscoring the influence of inorganic chemistry on nuclear imaging with radiometals. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 1880–1899. 10.1021/ic401607z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C. J.; Pajeau T. S.; Edwards W. B.; Sherman E. L. C.; Rogers B. E.; Welch M. J. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of copper-64-octreotide conjugates. J. Nucl. Med. 1995, 36, 2315–2325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers B. E.; Anderson C. J.; Connett J. M.; Guo L. W.; Edwards W. B.; Sherman E. L. C.; Zinn K. R.; Welch M. J. Comparison of four bifunctional chelates for radiolabeling monoclonal antibodies with copper radioisotopes: biodistribution and metabolism. Bioconjugate Chem. 1996, 7, 511–522. 10.1021/bc9600372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearling J. L. J.; Voss S. D.; Dunning P.; Snay E.; Fahey F.; Smith S. V.; Huston J. S.; Meares C. F.; Treves S. T.; Packard A. B. Imaging cancer using PET – the effect of the bifunctional chelator on the biodistribution of a 64Cu-labeled antibody. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2011, 38, 29–38. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearling J. L. J.; Paterson B. M.; Akurathi V.; Betanzos-Lara S.; Treves S. T.; Voss S. D.; White J. M.; Huston J. S.; Smith S. V.; Donnelly P. S.; Packard A. B. The ionic charge of copper-64 complexes conjugated to an engineered antibody affects biodistribution. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015, 26, 707–717. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoye N. C.; Baumeister J. E.; Najafi Khosroshahi F.; Hennkens H. M.; Jurisson S. S. Chelators and metal complex stability for radiopharmaceutical applications. Radiochim. Acta 2019, 107, 1087–1120. 10.1515/ract-2018-3090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reissig F.; Kopka K.; Mamat C. The impact of barium isotopes in radiopharmacy and nuclear medicine - From past to presence. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2021, 98, 59–68. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu A.; Wilson J. J. Advancing Chelation Strategies for Large Metal Ions for Nuclear Medicine Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 904–915. 10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca-Sabio A.; Mato-Iglesias M.; Esteban-Gómez D.; Tóth E.; de Blas A.; Platas-Iglesias C.; Rodríguez-Blas T. Macrocyclic receptor exhibiting unprecedented selectivity for light lanthanides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3331–3341. 10.1021/ja808534w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M. P.; Chiarizia R.; Shkrob I. A.; Ulicki J. S.; Spindler B. D.; Murphy D. J.; Hossain M.; Roca-Sabio A.; Platas-Iglesias C.; de Blas A.; Rodríguez-Blas T. Aqueous Complexes for Efficient Size-based Separation of Americium from Curium. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 6003–6012. 10.1021/ic500244p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadassery K. J.; King A. P.; Fayn S.; Baidoo K. E.; MacMillan S. N.; Escorcia F. E.; Wilson J. J. H2BZmacropa-NCS: A Bifunctional Chelator for Actinium-225 Targeted Alpha Therapy. Bioconjugate Chem. 2022, 33, 1222–1231. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.2c00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissig F.; Bauer D.; Zarschler K.; Novy Z.; Bendova K.; Ludik M. C.; Kopka K.; Pietzsch H.-J.; Petrik M.; Mamat C. Towards Targeted Alpha Therapy with Actinium-225: Chelators for Mild Condition Radiolabeling and Targeting PSMA-A Proof of Concept Study. Cancers 2021, 13, 1974. 10.3390/cancers13081974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissig F.; Zarschler K.; Novy Z.; Petrik M.; Bendova K.; Kurfurstova D.; Bouchal J.; Ludik M. C.; Brandt F.; Kopka K.; Khoylou M.; Pietzsch H.-J.; Hajduch M.; Mamat C. Modulating the pharmacokinetic profile of Actinium-225-labeled macropa-derived radioconjugates by dual targeting of PSMA and albumin. Theranostics 2022, 12, 7203–7215. 10.7150/thno.78043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B. J. B.; Andersson J. D.; Wuest F. Radiolanthanum: Promising theranostic radionuclides for PET, alpha, and Auger-Meitner therapy. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2022, 110–111, 59–66. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2022.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi S.; Di Marco V.; Tosato M. Bismuth chelation for targeted alpha therapy: Current state of the art. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2022, 114–115, 168–188. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2022.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahenkorah S.; Cassells I.; Deroose C. M.; Cardinaels T.; Burgoyne A. R.; Bormans G.; Ooms M.; Cleeren F. Bismuth-213 for Targeted Radionuclide Therapy: From Atom to Bedside. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 599. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13050599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissig F.; Bauer D.; Ullrich M.; Kreller M.; Pietzsch J.; Mamat C.; Kopka K.; Pietzsch H.-J.; Walther M. Recent Insights in Barium-131 as a Diagnostic Match for Radium-223: Cyclotron Production, Separation, Radiolabeling, and Imaging. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 272. 10.3390/ph13100272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abou D. S.; Thiele N. A.; Gutsche N. T.; Villmer A.; Zhang H.; Woods J. J.; Baidoo K. E.; Escorcia F. E.; Wilson J. J.; Thorek D. L. J. Towards the stable chelation of radium for biomedical applications with an 18-membered macrocyclic ligand. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 3733–3742. 10.1039/D0SC06867E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács A. Theoretical Study of Actinide Complexes with Macropa. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 26431–26440. 10.1021/acsomega.0c02873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele N. A.; MacMillan S. N.; Wilson J. J. Rapid Dissolution of BaSO4 by Macropa, an 18-Membered Macrocycle with High Affinity for Ba2+. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 17071–17078. 10.1021/jacs.8b08704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K.Quantitative Analysis of Binding Properties. In Analytical Methods in Supramolecular Chemistry; Schalley C. A., Ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 2006; pp 17–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H.-J.; Dürr H.. Frontiers in Supramolecular Organic Chemistry and Photochemistry; VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Weber G. In Molecular Biophysics; Pullman B., Weissbluth M., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, 1965; pp 369–396. [Google Scholar]

- Mato-Iglesias M.; Roca-Sabio A.; Pálinkás Z.; Esteban-Gómez D.; Platas-Iglesias C.; Tóth E.; de Blas A.; Rodríguez-Blas T. Lanthanide complexes based on a 1,7-diaza-12-crown-4 platform containing picolinate pendants: a new structural entry for the design of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 7840–7851. 10.1021/ic800878x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresge A. Solvent isotope effect in H2O–D2O mixtures. Pure Appl. Chem. 1964, 8, 243–258. 10.1351/pac196408030243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willcott M. R. MestRe Nova. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 13180–13180. 10.1021/ja906709t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson C. A.; Bro R. The N-way toolbox for MATLAB. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2000, 52, 1–4. 10.1016/S0169-7439(00)00071-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drobot B.; Steudtner R.; Raff J.; Geipel G.; Brendler V.; Tsushima S. Combining luminescence spectroscopy, parallel factor analysis and quantum chemistry to reveal metal speciation - a case study of uranyl(VI) hydrolysis. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 964–972. 10.1039/C4SC02022G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobot B.; Bauer A.; Steudtner R.; Tsushima S.; Bok F.; Patzschke M.; Raff J.; Brendler V. Speciation Studies of Metals in Trace Concentrations: The Mononuclear Uranyl(VI) Hydroxo Complexes. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 3548–3555. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. S.Solution of Simultaneous Chemical Equilibria in Heterogeneous Systems: Implementation in Matlab; Chemistry Faculty Publications, 2019; p 14; https://scholars.wlu.ca/chem_faculty/14.

- Drobot B.; Schmidt M.; Mochizuki Y.; Abe T.; Okuwaki K.; Brulfert F.; Falke S.; Samsonov S.; Komeiji Y.; Betzel C.; Stumpf T.; Raff J.; Tsushima S. Cm3+/Eu3+ induced structural, mechanistic and functional implications for calmodulin. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 21213–21222. 10.1039/C9CP03750K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brühlmann S. A.; Kreller M.; Pietzsch H.-J.; Kopka K.; Mamat C.; Walther M.; Reissig F. Efficient Production of the PET Radionuclide 133La for Theranostic Purposes in Targeted Alpha Therapy Using the 134Ba(p,2n)133La Reaction. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1167. 10.3390/ph15101167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissig F.; Hübner R.; Steinbach J.; Pietzsch H.-J.; Mamat C. Facile preparation of radium-doped, functionalized nanoparticles as carriers for targeted alpha therapy. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 1341–1349. 10.1039/C9QI00208A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kokov K. V.; Egorova B. V.; German M. N.; Klabukov I. D.; Krasheninnikov M. E.; Larkin-Kondrov A. A.; Makoveeva K. A.; Ovchinnikov M. V.; Sidorova M. V.; Chuvilin D. Y. 212Pb: Production Approaches and Targeted Therapy Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 189. 10.3390/pharmaceutics14010189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. 10.1002/wcms.81. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreirós-Martínez R.; Esteban-Gómez D.; Tóth C.; de Blas A.; Platas-Iglesias C.; Rodríguez-Blas T. Macrocyclic Receptor Showing Extremely High Sr(II)/Ca(II) and Pb(II)/Ca(II) Selectivities with Potential Application in Chelation Treatment of Metal Intoxication. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 3772–3784. 10.1021/ic200182e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone V.; Cossi M. Quantum Calculations of Molecular Energies and Energy Gradients in Solution by a Conductor Solvent Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995–2001. 10.1021/jp9716997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Ernzerhof M.; Burke K. Rationale for mixing exact exchange with density functional approximations. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105, 9982–9985. 10.1063/1.472933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adamo C.; Barone V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. 10.1063/1.478522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard B. P.; Altarawy D.; Didier B.; Gibson T. D.; Windus T. L. A New Basis Set Exchange: An Open, Up-to-date Resource for the Molecular Sciences Community. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2019, 59, 4814–4820. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F.; Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W.; Dalke A.; Schulten K. VMD – Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich S.; Sieber C.; Drobot B.; Tsushima S.; Barkleit A.; Schmeide K.; Stumpf T.; Kretzschmar J. Eu(III) and Cm(III) Complexation by the Aminocarboxylates NTA, EDTA, and EGTA Studied with NMR, TRLFS, and ITC – An Improved Approach to More Robust Thermodynamics. Molecules 2023, 28, 4881. 10.3390/molecules28124881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar J.; Wollenberg A.; Tsushima S.; Schmeide K.; Acker M. 2-Phosphonobutane-1,2,4,-Tricarboxylic Acid (PBTC): pH-Dependent Behavior Studied by Means of Multinuclear NMR Spectroscopy. Molecules 2022, 27, 4067. 10.3390/molecules27134067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller A.; Senwitz C.; Foerstendorf H.; Tsushima S.; Holtmann L.; Drobot B.; Kretzschmar J. Europium(III) Meets Etidronic Acid (HEDP): A Coordination Study Combining Spectroscopic, Spectrometric, and Quantum Chemical Methods. Molecules 2023, 28, 4469. 10.3390/molecules28114469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasoe P. K.; Long F. A. Use of glass electrodes to measure acidities in deuterium oxide. J. Phys. Chem. 1960, 64, 188–190. 10.1021/j100830a521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus Y. A simple empirical model describing the thermodynamics of hydration of ions of widely varying charges, sizes, and shapes. Biophys. Chem. 1994, 51, 111–127. 10.1016/0301-4622(94)00051-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov A. S.; Simms M. E.; Bryantsev V. S.; Benny P. D.; Griswold J. R.; Delmau L. H.; Thiele N. A. Elucidating the coordination chemistry of the radium ion for targeted alpha therapy. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 9938–9941. 10.1039/D2CC03156F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács A.; Varga Z. H2O coordination in macropa complexes of f elements (Ac, La, Lu): feasibility of the 11th coordination site. Struct. Chem. 2021, 32, 643–653. 10.1007/s11224-020-01717-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács A. Theoretical Study of Actinide Complexes with Macropa. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 26431–26440. 10.1021/acsomega.0c02873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte O.; Meggers W. F. Some rules of spectral structure. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1925, 11, 459–463. 10.1364/JOSA.11.000459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bünzli J. C. G.; Eliseeva S. V.. Basics of Lanthanide Photophysics. In Lanthanide Luminescence; Springer Series on Fluorescence; Hänninen P., Härmä H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, 2010; Vol. 7. 10.1007/4243_2010_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner P. A. Some misconceptions concerning the electronic spectra of tri-positive europium and cerium. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5090–5101. 10.1039/c3cs60033e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binnemans K. Interpretation of europium(III) spectra. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 295, 1–45. 10.1016/j.ccr.2015.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks W. DeW. Jr; Sudnick D. R. Lanthanide ion probes of structure in biology. Laser-induced luminescence decay constants provide a direct measure of the number of metal-coordinated water molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 334–340. 10.1021/ja00496a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T.; Choppin G. R. Luminescence study on determination of the hydration number of Cm(III). J. Alloys Comp. 1994, 213-214, 313–317. 10.1016/0925-8388(94)90921-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T.; Kato Y. Luminescence study on hydration states of lanthanide(III)–polyaminopolycarboxylate complexes in aqueous solution. J. Alloys Comp. 1998, 275–277, 806–810. 10.1016/S0925-8388(98)00446-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich R. V.; Stavila V.; Marinin D. V.; Voit E. I.; Whitmire K. H. Stereochemistry of lead(II) complexes with oxygen donor ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009, 253, 1316–1352. 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele N. A.; Brown V.; Kelly J. M.; Amor-Coarasa A.; Jermilova U.; MacMillan S. N.; Nikolopoulou A.; Ponnala S.; Ramogida C. F.; Robertson A. K. H.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez C.; Schaffer P.; Williams C. Jr; Babich J. W.; Radchenko V.; Wilson J. J. An Eighteen-Membered Macrocyclic Ligand for Actinium-225 Targeted Alpha Therapy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 14712–14717. 10.1002/anie.201709532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makvandi M.; Dupis E.; Engle J. W.; Nortier F. M.; Fassbender M. E.; Simon S.; Birnbaum E. R.; Atcher R. W.; John K. D.; Rixe O.; Norenberg J. P. Alpha-Emitters and Targeted Alpha Therapy in Oncology: from Basic Science to Clinical Investigations. Target Oncol. 2018, 13, 189–203. 10.1007/s11523-018-0550-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Máthé D.; Szigeti K.; Hegedüs N.; Horváth I.; Veres D. S.; Kovács B.; Szücs Z. Production and in vivo imaging of 203Pb as a surrogate isotope for in vivo 212Pb internal absorbed dose studies. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2016, 114, 1–6. 10.1016/j.apradiso.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil B. L.; Robertson A. K. H.; Fu W.; Yang H.; Hoehr C.; Ramogida C. F.; Schaffer P. Production, purification, and radiolabeling of the 203Pb/212Pb theranostic pair. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2021, 6, 6. 10.1186/s41181-021-00121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das T.; Banerjee S. Theranostic Applications of Lutetium-177 in Radionuclide Therapy. Curr. Radiopharm. 2015, 9, 94–101. 10.2174/1874471008666150313114644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer D.Investigation of heavy alkaline earth metals for radiopharmaceutical application. Ph.D. Dissertation, TU Dresden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abou D. S.; Thiele N. A.; Gutsche N. T.; Villmer A.; Zhang H.; Woods J. J.; Baidoo K. E.; Escorcia F. E.; Wilson J. J.; Thorek D. L. J. Towards the stable chelation of radium for biomedical applications with an 18-membered macrocyclic ligand. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 3733–3742. 10.1039/D0SC06867E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.