Abstract

Background

Enormous clinical and biomedical researches have demonstrated that microbes are crucial to human health. Identifying associations between microbes and diseases can not only reveal potential disease mechanisms, but also facilitate early diagnosis and promote precision medicine. Due to the data perturbation and unsatisfactory latent representation, there is a significant room for improvement.

Results

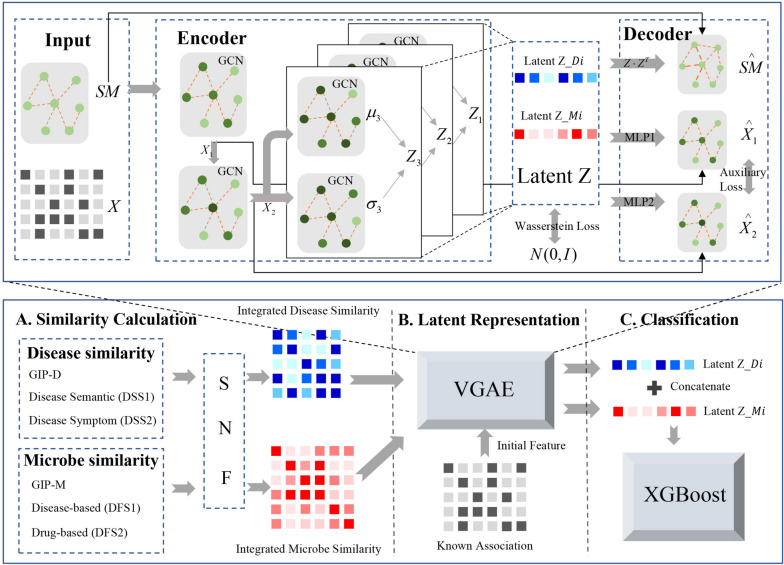

In this work, we proposed a novel framework, Multi-scale Variational Graph AutoEncoder embedding Wasserstein distance (MVGAEW) to predict disease-related microbes, which had the ability to resist data perturbation and effectively generate latent representations for both microbes and diseases from the perspective of distribution. First, we calculated multiple similarities and integrated them through similarity network confusion. Subsequently, we obtained node latent representations by improved variational graph autoencoder. Ultimately, XGBoost classifier was employed to predict potential disease-related microbes. We also introduced multi-order node embedding reconstruction to enhance the representation capacity. We also performed ablation studies to evaluate the contribution of each section of our model. Moreover, we conducted experiments on common drugs and case studies, including Alzheimer’s disease, Crohn’s disease, and colorectal neoplasms, to validate the effectiveness of our framework.

Conclusions

Significantly, our model exceeded other currently state-of-the-art methods, exhibiting a great improvement on the HMDAD database.

Keywords: Variational graph autoencoder, Wasserstein distance, Microbe-disease association, XGBoost

Background

Microorganisms are a class of microscopic organisms that exist in the form of single cells or colonies [1]. Extensive research has confirmed the close interaction between human hosts and the majority of microbial colonies, which mostly consist of bacteria, archaea, viruses, and protozoa [2, 3]. Microorganisms are commonly present on and within various human body organs, such as the mouth, skin, and intestines. Particularly, the majority of these microorganisms are located within the gastrointestinal tract [4]. Actually, the majority of commensal microorganisms inhabiting humans are not detrimental to health and even have mutually beneficial relationships with their human hosts [5]. The human microbiome is usually perceived as the “humanity’s forgotten organ” due to its liver-like abilities, including promoting nutrient absorption, resisting the invasion of pathogens, and promoting metabolism [6–8]. There has reached a consensus that dysbiosis or imbalance in microbial communities can lead to human disease [9, 10], such as asthma [11], diabetes [12], and cancer [13]. For instance, the overgrowth of Klebsiella bacteria in the gut has been shown to play a role in several chronic diseases, including colitis and Crohn’s disease [14]. Conversely, following a low-starch diet can help impede the growth of Klebsiella bacteria and thus, potentially alleviate symptoms of Crohn’s disease [15]. Therefore, identifying associations between microbes and diseases can not only reveal potential disease mechanisms, but also facilitate early diagnosis and promote precision medicine through potential biomarkers. Considering that traditional biomedical experiments are time and labor consuming, it is critical to develop computational methods with high accuracy and efficiency for microbe-disease association prediction.

In recent years, a multitude of computational methods has been proposed to predict microbe-disease associations. These methods can be roughly categorized into four groups: network-based methods, matrix factorization methods, regularization methods, and neural network methods, as mentioned by Wang et al. [16] and Wen et al. [17]. (1) The first category was the most intuitionistic method with strong interpretability, which adopted topological information from networks constructed using multiple databases. For example, Chen et al. [18] proposed KATZHMDA based on the KATZ measure for predicting microbe-disease association, while Lei et al. [19] designed LGRSH, which implemented node2vec algorithm [20] to obtain the low-dimensional representations and adopted the improved rule-based inference method for microbe-disease association prediction. (2) The core idea of matrix factorization methods is factorizing the input matrix into two matrixes of lower dimensionality, which simultaneously maintain the property of reconstruction. RNMFMDA, proposed by Peng et al. [21], employed random walk with restart to achieve reliable negative sampling on the microbe-disease network and subsequently employed a neighborhood regularized logistic matrix factorization technique to predict the likelihood of microbe-disease associations. (3) Regularization methods are characterized by their application to least square classifications using different forms of regularization. Typically, Xu et al. [22] proposed MDAKRLS by combining hamming interaction spectral similarity with Kronecker regularized least squares for microbe-disease association prediction. (4) Neural network methods prevailed over other methods by miles. Long et al. [23] designed a new framework named GATMDA, to represent microbes and diseases and predict associations based on an optimized graph attention network with inductive matrix completion. Furthermore, MVGCNMDA, proposed by Hua et al. [24], utilized the multi-view graph for data augmentation and multi-channel attention to predict disease-related microbes.

Despite the promising progress made by the aforementioned methods, there are still some limitations and shortcomings. Firstly, the most vital point is the perturbation, including noise and deficiency, in similarity networks or other heterogeneous networks, which is usually caused by the incomplete data or the bias of network construction means. Secondly, merely considering a similarity network from a single perspective may result in information insufficiency. Meanwhile, the simple averaging of similarity networks from different perspectives seems too naïve and how to reasonably aggregate similarity networks is still challenging. Thirdly, we observed that models with strong interpretation generally performed unsatisfactorily, whereas some models with lower interpretation, especially in neural network methods, performed better, indicating the capacity of latent representation needs to be improved.

Taking the above limitations into consideration, in this work, we proposed a novel framework, Multi-scale Variational Graph AutoEncoder embedding Wasserstein distance (MVGAEW) for identifying disease-related microbes. Firstly, we calculated disease and microbe similarities from different perspectives, including disease functional similarity, microbe functional similarity, and Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarity. Further, we integrated different similarity matrixes by leveraging similarity network confusion (SNF [25]). Secondly, we introduced the variational graph autoencoder (VGAE [26]) to learn node latent representations. The Wasserstein distance(WD [27]) and the idea of multi-scale [28] were employed to improve the representational capacity of VGAE. Moreover, inspired by the diffusion model [29] and parallel neighborhood reconstruction [27], we innovatively proposed an auxiliary task, multi-order node embedding reconstruction, to enhance the robustness of VGAE. Ultimately, we utilized XGBoost [30] to predict the potential microbe-disease pairs by inputting the concatenation of latent representations for each microbe and disease. Our experimental results on the HMDAD database indicated that our proposed model exceeded other current SOTA methods with a great promotion. Significantly, we also conducted validations based on common drugs and several case studies on Alzheimer’s disease, Crohn’s disease, and colorectal neoplasms, which further validate the effectiveness of MVGAEW.

Results and discussion

Experiment settings

In this study, tenfold cross-validations were adopted to ensure the accuracy and reliability of our model. We conducted a series of frequently used metrics from multiple perspectives, including AUROC, AUPR, F1, Precision, Recall, and Accuracy, to evaluate our model’s performance across all comparison experiments. In the SNF part, we set the number of neighbors in KNN as 5 and 30 for diseases and microbes in the HMDAD database. In the VAGE part, we used three scales of multi-scale encoders for both disease and microbe similarity networks, including 16, 32, and 64. In addition, the parameters of the XGBoost classifier were set as default. We adopted the StepLR strategy to schedule the learning rate during training, in which the learning rate will be progressively updated until it reached the specified epochs.

Ablation study

To provide a detailed analysis of the contribution of each component in VGAE, we carried out ablation experiments based on the HMDAD database. MVGAEW refers to the complete model without any components removed. Del_WD denotes the model without the WD component, replaced with KL-divergency. Del_multi-scale represents the model without a multi-scale layer in the encoder portion. Del_aux_1 and Del_aux_2 represent the model without the auxiliary 1st-order and 2nd-order node embedding reconstruction tasks, respectively. Literally, Del_aux_1_2 indicates the model taking no account of auxiliary task. Through these experiments, we aimed to analyze the individual contribution of each component towards the overall model accuracy and performance Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance of ablation experiments based on the HMDAD database

| Method | AUROC | AUPR | F1 | Precision | Recall | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVGAEW | 0.9798 | 0.9855 | 0.9412 | 0.9524 | 0.9302 | 0.9444 |

| Del_WD | 0.9446 | 0.9419 | 0.8842 | 0.8077 | 0.9767 | 0.8778 |

| Del_multi-scale | 0.9684 | 0.9715 | 0.9111 | 0.8723 | 0.9535 | 0.9111 |

| Del_aux_1 | 0.9746 | 0.9789 | 0.9091 | 0.8889 | 0.9302 | 0.9111 |

| Del_aux_2 | 0.9749 | 0.9808 | 0.9213 | 0.8367 | 0.9534 | 0.9222 |

| Del_aux_1_2 | 0.9737 | 0.9799 | 0.8913 | 0.8367 | 0.9530 | 0.8889 |

The bold values denote the max value in columns

As shown in Table 2, we notice that almost each experiment with the prefix Del does not perform as well as MVGAEW, indicating the three major ideas integrated into our model are effective. In terms of AUROC and AUPR, the sharply reduced experiment is Del_WD, verifying the contribution brought from WD is more than KL-divergency and other major ideas, which is also consistent with the point that bottleneck lies in the disappearance of gradient information from KL-divergence during later stages of training. Similarly, the second sharply reduced experiment is Del_multi-scale with a decreasing percentage of 1.164%, revealing that the strategy of the multi-scale encoder is effective. Compared to Del_aux_1_2, Del_aux_1 and Del_aux_2 both demonstrate improved performance except Recall, suggesting that either 1st-order or 2nd-order node embedding reconstruction tasks can be valid. Furthermore, the degree of decline of Del_aux_1 is greater than that of Del_auu_2, highlighting the importance of 1st-order node-wise feature information over the 2nd-order counterparts.

Table 2.

The comparison between our model and other methods under tenfold cross-validations on the HMDAD database

| Method | AUROC | AUPR | F1 | Precision | Recall | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVGAEW | 0.9798 | 0.9855 | 0.9412 | 0.9524 | 0.9302 | 0.9444 |

| GATMDA | 0.9398 | 0.9364 | 0.8151 | 0.8672 | 0.7689 | 0.8256 |

| RNMFMDA | 0.9124 | 0.2767 | 0.1297 | 0.0753 | 0.4667 | 0.9732 |

| KATZHMDA | 0.8348 | 0.5910 | 0.2017 | 0.1160 | 0.7733 | 0.7482 |

| LRLSHMDA | 0.8851 | 0.6080 | 0.2243 | 0.1290 | 0.8600 | 0.7553 |

| MVGCNMDA | 0.9196 | 0.9237 | 0.9113 | 0.9843 | 0.8484 | 0.9178 |

| MVFA | 0.9718 | 0.8864 | 0.8755 | 0.7961 | 0.9729 | 0.8622 |

The bold values denote the max value in columns

Performance comparison with SOTA methods

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed model, we conducted several comparative experiments against classical representative prediction approaches. Within these experiments, we compared some representative methods from Matrix Factorization, Regularization, and Neural Network, As previously mentioned by wang et al. [16] and Wen et al. [17]. The brief summarization is shown as follows:

KATZHMDA [18], the first proposed method for the prediction of microbe-disease associations, utilized KATZ measurement to calculate the node centrality for prediction.

RNMFMDA [21], which integrated reliable negative sampling into neighborhood regularized logistic matrix factorization to evaluate the likelihood of associations for all microbe-disease pairs.

LRLSHMDA [31], which featured with the least squares classifier with Laplacian regularization to solve the link prediction task.

GATMDA [23], incorporated the concept of “talking heads” into the optimized graph attention network to learn latent representations from microbes and disease.

MVGCNMDA [24], which analogously adopted the idea of multi-scale and utilized the multi-view graph for data augmentation to predict disease-related microbes.

MVFA [32], which proposed a multi-view feature aggregation model that combines both linear and nonlinear features to recognize disease-related microbes.

The comparison experiments were scheduled under tenfold cross validations based on HMDAD database. In addition, we also carried out parameter adjustment experiments for each of the implemented methods to ensure that their performance was as close as possible to that reported in their original papers.

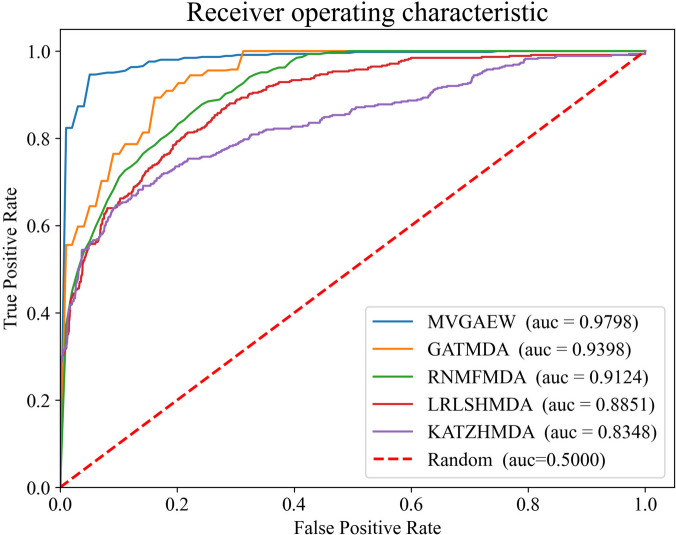

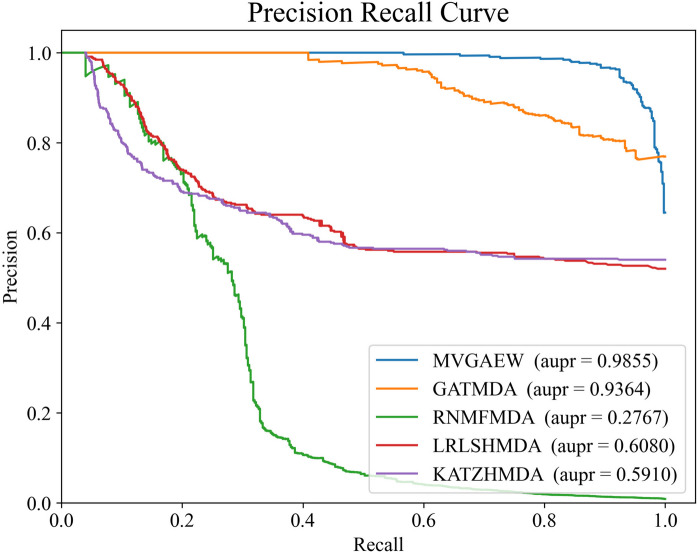

As shown in Figs. 1 and 2, our proposed model achieves higher AUROC and AUPR scores compared to other methods, demonstrating its superior performance. Furthermore, the performance of different methods across multiple metrics is demonstrated in Table 2. It is obvious that the F1 value of our model also dominates other approaches. Despite the precision and recall values of our model not being the highest, the balance between precision and recall is fabulous in a higher level, rather than the large gap in a lower level like that in LRLSHMDA, KATZHMDA and RNMFMDA. As well-known, the F1 metric is designed to make a tradeoff between precision and recall and is considered a splendid metric to measure the performance of the model, which is consistent with the fact that the F1 value of our model exceeds others. It is also evident that the traditional methods, such as LRLSHMDA, KATZHMDA, and RNMFMDA, perform poorly, while other neural network methods show superior performance. In addition, we note that the accuracy of our model ranks second, with RNMFMDA achieving the best performance. It is worth noting that RNMFMDA adopted a reliable negative sampling strategy, resulting in the negative samples fed into the model being quite simple and leading to the trained model tended to learn simple knowledge and local distribution. Furthermore, this also can be verified in the lower AUPR and precision scores, which are metrics that focus on negative samples.

Fig. 1.

The ROC curves of different models on tenfold cross-validations

Fig. 2.

The PR curves of different models on tenfold cross-validations

Performance comparison with widely used databases

As the accumulation of data, databases become more mature, containing increasingly valid associations between microbes and diseases. To ensure scalability and powerful generalization, we conducted several experiments based on three additional databases. Giving enough thought to the sparse matches of microbes between the microbe-disease database and the microbe-drug database, we calculated the microbe similarities for the latter database without relying on drug-based functional similarity.

As shown in Table 3, our model based on three additional databases also performs well. Apart from HMDAD, the most impressive results come from Peryton, the latest published database, with the highest density of known association networks. We observed that model performance improves over time as the databases increase in both quality and quantity, and their distribution becomes more representative of the true global distribution.

Table 3.

The comparison of all microbe-disease databases under tenfold cross validations

| Database | AUROC | AUPR | F1 | Precision | Recall | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMDAD | 0.9798 | 0.9855 | 0.9412 | 0.9524 | 0.9302 | 0.9444 |

| Disbiome | 0.9451 | 0.9388 | 0.8761 | 0.8590 | 0.8939 | 0.8717 |

| MicroPhenDB | 0.9616 | 0.9576 | 0.8899 | 0.8779 | 0.9022 | 0.8902 |

| Peryton | 0.9668 | 0.9630 | 0.9013 | 0.8726 | 0.9320 | 0.9029 |

The bold values denote the max value in columns

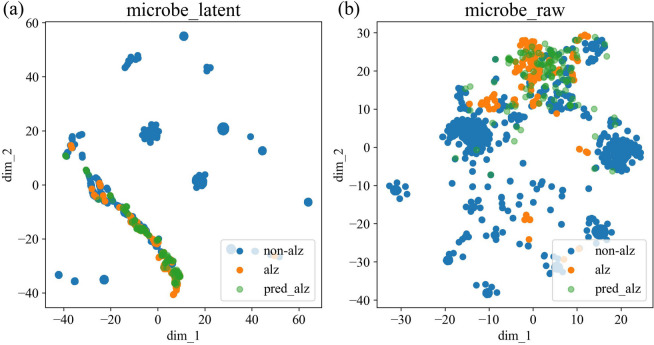

Interpretation of latent representation

Our model has undeniably demonstrated outstanding performance for the microbe-disease associations prediction task. With the purpose of further exploring the interpretability of latent representation from the insight of distribution, we visualized the feature distribution of the adopted latent representation for microbes. Specifically, we accomplished this by employing the t-SNE [33] method to project high-dimensional data into a two-dimensional (2D) plane for visualization.

Figure 3a demonstrates the distribution after adopting latent representation, while Fig. 3b shows the distribution of raw integrated similarity network without the use of latent representation. The points labeled as “alz” and “non-alz” on both figures indicate whether a particular microbe is related to Alzheimer’s disease [34] in the peryton database, while the points labeled as “pred_alz” in both figures represent the potential microbes that MVGAEW predicts to be related to Alzheimer’s disease within the top 50 probabilities. The clusters in Fig. 3a are clearly more tightly packed and exhibit a pattern characterized by long strips associated with specific diseases. However, some points labeled as “pred_alz” in Fig. 3b are completely disconnected from known associations, suggesting that microbes with a high probability may not be identified if the integrated similarity network is used alone, without employing other representation learning methods.

Fig. 3.

Visualizations of distribution whether adopting latent representation for microbes related to Alzheimer’s disease. a The latent distribution by adopting latent representation proposed in our framework and b the raw distribution of integrated similarity network

Validation based on common drugs

Subsequently, with the purpose of further exploring the validity of our model, we investigated common drugs related to specific microbes and diseases. It is well-known that specific drugs can impact diseases and interfere with microbial metabolism. Spontaneously, there may be a strong association between a disease and a microbe if they do share common related drugs. To further support the potential association between a disease and a microbe, we conducted literature verification in Pubmed to identify any relevant explanations or studies regarding the specific microbe-disease pair.

We obtained disease-related drugs by utilizing the MalaCard database [35], which is an integrated and continuously updated database of human diseases and their annotations from 75 data sources. To extract microbe-related drugs, we utilized both the MDAD and aBiofilm databases, which contain high-confidence microbe-drug associations. To maximize the number of microbe-related drugs obtained, we mapped microbes of MicroPhenDB with those in MDAD and aBiofilm. We presented the probabilities predicted by MVGAEW between a given microbe-disease pair in Table 4, along with corresponding PubMed IDs (PMID). As expected, the pairs with higher probabilities shared more common drugs, which is in line with the observation that disease-related drugs tend to impact multiple microbes. For instance, in the case of colorectal cancer, tobramycin has been shown to impact both Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

Table 4.

The common drugs related to specific microbe and disease

| Microbe | Disease | Common drugs | Probability | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | Sorbitol, rifampicin | 0.9491 | 31,808,577 |

| Escherichia coli | Colorectal cancer | Ertapenem, tobramycin, framycetin | 0.9474 | 28,106,826 |

| Escherichia coli | Atopic eczema | Zinc oxide, tannic acid | 0.9403 | 33,023,370 |

| Escherichia coli | Cirrhosis of liver | Imipenem, cefoperazone, cefoxitin | 0.8973 | 31,295,531 |

| Escherichia coli | Hiv infection | Sulfamethoxazole | 0.8920 | 25,482,819 |

| Escherichia coli | Mouth neoplasm | Sorbitol | 0.8245 | 35,096,312 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Colorectal cancer | Azithromycin, tobramycin | 0.7997 | 24,467,507 |

| Escherichia coli | Bacterial vaginosis | Tetracycline, tannic acid | 0.7771 | 29,933,767 |

| Escherichia coli | Congenital short bowel syndrome | Daidzein | 0.7081 | 9,125,641 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Cirrhosis of liver | Imipenem, azithromycin, cefoxitin | 0.6987 | 22,833,245 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | Rifampicin | 0.6948 | 34,978,141 |

| Escherichia coli | Dental caries | Sorbitol | 0.6351 | 30,657,107 |

| Escherichia coli | Sclerosing cholangitis | Curcumin, minocycline | 0.6282 | 30,252,934 |

| Escherichia coli | Otitis media | Cefpodoxime | 0.6270 | 28,613,732 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Periodontitis | Norgestimate, azithromycin, minocycline | 0.5752 | 30,241,716 |

Case studies

In this section, we conducted case studies on specific diseases to demonstrate the capability of predicting disease-related microbes. The diseases we focused on include Alzheimer’s disease [34], Crohn’s disease [36], and colorectal neoplasms [37]. Based on the peryton database, we screened out known microbe-disease associations and predicted microbes with probability in the top 20 for each concerned disease. In addition, we also provided corresponding evidence from Pubmed to confirm the existence of these associations.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a prevalent, chronic, and progressive neurodegenerative disease that is considered a kind of dementia. Often characterized by symptoms of memory loss and emotional regulation disorders, weakened learning ability, and loss of motor ability, it can significantly impact the development of individuals, families and even society [38]. As previous works reported, there is a direct link between altered gut microbiota and the development of AD. Furthermore, studies have indicated that AD can be prevented through intermittent fasting [39]. As demonstrated in Table 5, 17 kinds of microbes have the support of literature, while the remainder suggest a strong potential association related to AD. In particular, we further conducted validations on Fusobacteriaceae from multiple perspectives. Through high throughput DNA sequencing, researchers have shown that levels of Fusobacteriaceae are consistently higher, while levels of Prevotellaceae are generally lower, in subjects without dementia [40]. In the aspect of inflammation, Fusobacteriaceae have been found to be strongly associated with inflammation in hepatic encephalopathy [41]. Additionally, high levels of Fusobacteriaceae in the IR-MO group have been found to be associated with low-grade inflammation in adipose tissue among people with insulin resistance and morbid obesity [42]. Simultaneously, Yang et al. [43] suggested that inflammation may be a contributing factor in the progression of AD. Collectively, these findings strengthen the evidence linking Fusobacteriaceae to the development of AD.

Table 5.

Top 20 predicted microbes related to Alzheimer’s disease

| Rank | Microbe | PMID |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fusobacteria | 25,576,662 |

| 2 | Roseburia | 35,173,707 |

| 3 | Fusobacteriaceae | Unconfirmed |

| 4 | Megasphaera | Unconfirmed |

| 5 | Actinomycetaceae | 35,275,538 |

| 6 | Fusobacterium | 25,576,662 |

| 7 | Klebsiella | 36,068,280 |

| 8 | Veillonellaceae | 32,533,776 |

| 9 | Butyricicoccus | 36,185,477 |

| 10 | Veillonella | 34,931,394 |

| 11 | Coprococcus | 35,807,841 |

| 12 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | 25,576,662 |

| 13 | Corynebacterium | 32,290,475 |

| 14 | Campylobacter | 32,290,475 |

| 15 | Oribacterium | Unconfirmed |

| 16 | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | 34,622,235 |

| 17 | Oscillospira | 36,185,477 |

| 18 | Citrobacter | 22,891,247 |

| 19 | Escherichia coli | 29,472,250 |

Crohn’s disease (CD), a subtype of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), is characterized by gut microbiome dysbiosis and accompanied by extraintestinal symptoms such as fever and nutritional disturbance. Colorectal neoplasms (CN), a common malignant tumor in the gastrointestinal tract, are often caused by unhealthy living habits or environmental pollution. Similarly, CN are also characterized by dysbiosis in the gut microbiota [37]. As shown in Tables 6 and 7, we have provided the top 20 predicted microbes and corresponding evidence for both CD and CN for future research. It is important to note that the unconfirmed microbes are supposed to attract more attention in the future studies.

Table 6.

Top 20 predicted microbes related to Crohn’s disease

| Rank | Microbe | PMID |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Atopobium | 35,122,247 |

| 2 | Barnesiella | 35,806,099 |

| 3 | Parasutterella | 35,971,134 |

| 4 | Methylobacterium | 33,430,702 |

| 5 | Xanthomonadales | Unconfirmed |

| 6 | Corynebacteriaceae | 25,689,526 |

| 7 | Lachnoclostridium | 36,034,848 |

| 8 | Leptotrichia | Unconfirmed |

| 9 | Parvimonas | 34,935,421 |

| 10 | Rhodococcus | 25,546,345 |

| 11 | Epsilonproteobacteria | 32,040,665 |

| 12 | Sphingobacteriia | Unconfirmed |

| 13 | Enterobacter | 31,764,438 |

| 14 | Schwartzia | 3,318,407 |

| 15 | Salmonella | 22,009,735 |

| 16 | Bradyrhizobiaceae | Unconfirmed |

| 17 | Ochrobactrum | Unconfirmed |

| 18 | Halomonas | Unconfirmed |

| 19 | Halomonadaceae | Unconfirmed |

| 20 | Bacillaceae | 35,967,326 |

Table 7.

Top 20 predicted microbes related to colorectal neoplasms

| Rank | Microbe | PMID |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Actinomycetales | 33,934,716 |

| 2 | Erysipelotrichia | Unconfirmed |

| 3 | Escherichia coli | 28,106,826 |

| 4 | Rothia mucilaginosa | Unconfirmed |

| 5 | Limosilactobacillus fermentum | 31,581,581 |

| 6 | Flavonifractor | 34,799,562 |

| 7 | Barnesiella | 32,502,642 |

| 8 | Holdemanella | 31,988,379 |

| 9 | Erysipelotrichales | Unconfirmed |

| 10 | Selenomonadales | Unconfirmed |

| 11 | Erysipelatoclostridium | 35,269,806 |

| 12 | Veillonella dispar | 26,549,775 |

| 13 | [Clostridium] leptum | 18,237,311 |

| 14 | Candidatus Saccharibacteria | Unconfirmed |

| 15 | Barnesiellaceae | Unconfirmed |

| 16 | Verrucomicrobia | 34,389,559 |

| 17 | Bifidobacterium longum | 31,340,751 |

| 18 | Butyrivibrio | 16,317,136 |

| 19 | Roseburia faecis | 21,850,056 |

| 20 | Comamonadaceae | 28,431,244 |

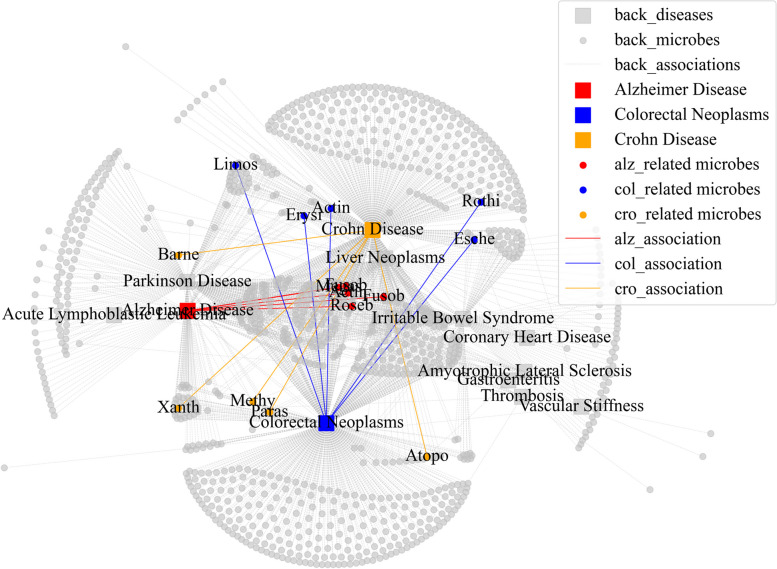

Further, we visualized the distribution of existing and predicted associations related to specific diseases as shown in Fig. 4. The four most relevant diseases were screened out for each case disease through an integrated disease similarity matrix and identified the top 5 predicted microbes related to each case disease. In Fig. 4, we observed that the microbes in the center appear to affect multiple diseases, and the predicted microbes further support this finding. For instance, Xanthomonadales was found to be associated with both Parkinson’s disease and CN. We also noticed that there are common microbes shared between CD and CN, as well as a considerable overlap between CD and Parkinson’s disease. Therefore, it is highly likely that Xanthomonadales is related to CD, and this observation further highlights the pattern of second-order neighbors.

Fig. 4.

The distribution of existing and predicted associations related to case diseases

Conclusions

In this study, we proposed a novel framework, named MVGAEW, to identify disease-related microbes. Starting with the point of data perturbation, we utilized VGAE to fit distribution, which allow us to deal with the interference caused by perturbation. VGAE was advantageous in capturing neighbor structure information while mitigating the impact of noise and deficiency to some extent by modeling the true probability distribution. To further enhance the representational capacity of VGAE, we incorporated the multiscale concept to capture local and global patterns at different scales. This allowed us to learn a more complicated probability distribution with high robustness. Additionally, we innovatively designed an effective auxiliary task, called multi-order node embedding reconstruction, to maintain the neighbor embeddings during message propagation. Furthermore, the Wasserstein distance was employed to substitute KL divergence to maintain the gradient information during backpropagation. After calculating and integrating similarity networks, we utilized the improved VGAE for latent representation. Ultimately, XGBoost was adopted to predict the probability between a given pair of microbe and disease. To validate the performance of our model, we carried out several comparison experiments with SOTA methods and performed an ablation study. Most importantly, our approach not only provided the interpretation of latent representation, but also included sufficient validations to verify the effectiveness of our model.

Although outstanding performance has been achieved in several studies, there is still room for improvement. Particularly in handling imbalanced samples, there is a lack of research on generating productive positive samples, which is still a challenging task. It seems meaningless to sample out reliable negative samples, which would perhaps learn a simple distribution and result in overfitting. Relatively, how to generate productive positive samples remains a significant challenge. Furthermore, it is fascinating to predict signed microbe-disease association as the undirected network would lead to loss of information. Last but not least, a promising research direction is the introduction of multi-task learning into the prediction of disease-microbe-drug associations, which can leverage shared structures and potentially enhance the model’s overall performance.

Methods

Data sources

Microbe-disease association databases

Until now, researchers have developed several widely used databases for microbe-disease association prediction as summarized in Table 8. In 2016, Ma et al. developed the first Human Microbe–Disease Association Database (HMDAD [44]), which collected 450 confirmed microbe-disease associations between 39 diseases and 292 microbes from published literature after redundancy elimination. In 2018, Janssens et al. established Disbiome [45], a database that catalogs 8731 known associations between 1622 microbes and 374 diseases, by screening out from 1191 published academic papers without redundancy. Subsequently, MicroPhenDB [46] was constructed by the same means of HMDAD and Disbiome, including 5511 non-redundant associations between 500 diseases and 1,774 microbes in 22 newly collected human parts. Recently, Skoufos et al. proposed Peryton [47], which was constructed by collecting experimentally supported associations and contained 4172 available associations between 1396 microbes and 43 diseases. We converted the information on known microbe-disease associations into a binary matrix for ease of use, in which the value is 1 if microbe-disease item exists in database, and 0 otherwise. and represent the number of unique diseases and unique microbes, respectively.

Table 8.

Databases for microbe-disease association prediction

| Database | Microbes | Diseases | Associations | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMDAD | 292 | 39 | 450 | 2016 |

| Disbiome | 1622 | 374 | 8731 | 2018 |

| MicroPhenDB | 1774 | 500 | 5511 | 2020 |

| Peryton | 1396 | 43 | 4172 | 2021 |

Disease similarity network

In our proposed framework, we adopted three kinds of disease similarity calculation methods: semantic, symptom, and Gaussian interaction profile kernel.

Disease semantic similarity (DSS1)

We obtained the disease semantic information from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) database. Generally, the semantic information of a disease can be represented by a directed acyclic graph, (DAG) with MeSH descriptors. The formula for the DAG of a disease is typically formulated as , where denotes all related nodes in the DAG of the disease , and represents all edges in specific DAG.

With the introduction of DAG, Wang et al. [48] exploited the first disease semantic similarity computing method, in which the contribution of each disease to disease could be formulated as below:

| 1 |

where represents the contribution factor. Whereafter, the semantic value of a disease can be aggregated by the semantic contribution of nodes in corresponding DAG, described below:

| 2 |

Considering the symmetry, we calculated the semantic contribution for each disease and normalized it by the sum of the semantic values of each disease, described as below:

| 3 |

2) Disease symptom similarity (DSS2)

Human symptom-based disease network (HSDN [49]) was proposed by Zhou et al. The core idea is counting the cooccurrence of disease and symptoms in different literature. In HSDN, each disease can be represented by a vector of symptoms, of which utilizes the inverse document frequency to depict the association strength between symptom and disease. Whereafter, the cosine similarity is adopted to determine the similarity between disease and disease by leveraging the corresponding vector of symptoms, described below:

| 4 |

where represents a vector of symptoms of disease .

3) Disease Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarity (GIP-D)

Recently, there seems to reach a consensus that GIP kernel similarity performs well in pair-wise association prediction task. Under the inspiration that similar diseases generally show latent patterns with similar microbes [18], we calculated the GIP-D based on the known microbe-disease association matrix A. The equation for this calculation is as below:

| 5 |

Where is the ith column vector in . Moreover, is adopted to control the bandwidth and is usually set as 1 for normalization [50].

Microbe similarity network

To collect a broad range of information, we considered multiple perspectives and sources. We not only adopted the GIP similarity, but also utilized the concept of functional similarity, which is recognized in other types of pair-wise known associations. Below are the two types of functional similarity we calculated: DFS1 and DFS2.

1) Microbe Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarity (GIP-M)

Similar to GIP-D, the computation difference of GIP-M differs in , of which was replaced by in GIP-M. The subscript r denotes the row in . Moreover, other parameters were kept the same as GIP-D.

2) Disease-based functional similarity (DFS1)

Inspired by the calculation method of miRNA functional similarity [48], we computed the DFS1 based on DSS1. To begin with, the similarity score between a disease and a set of disease was calculated as below:

| 6 |

The functional similarity value between microbe and microbe can be derived from the corresponding disease set and the specific equation is described as below:

| 7 |

where and represent the disease sets related to microbe and microbe in , respectively. Moreover, the operator denotes the number of elements in the set .

3) Drug-based functional similarity (DFS2)

To calculate DFS2, we focused on the relationship between microbes and drugs and made use of existing databases (MDAD [51] and aBiofilm [52]) for the microbe-drug association prediction task. In the work of predecessors [53], the similarity matrix of drugs had been well calculated. We screened out common microbes between microbe-disease databases and microbe-drug databases and calculated two similarities using the same method as DFS1 from MDAD and aBiofilm. Subsequently, the final DFS2 was computed by averaging the two similarities if the corresponding value of one item is not zero in two databases, and choosing a nonzero item otherwise.

Similarity network confusion

In previous works [25, 54], SNF is a commonly used non-linear method that combines multiple similarities to create a unified similarity network. SNF adopted a new normalization method, of which takes self-similarity into consideration. In addition, SNF also computed local affinity for a certain similarity network by the means of K nearest neighbors (KNN). The key step of SNF is iteratively updating the corresponding similarity matrix for each network based on the new normalized matrix and local affinity matrix. Considering that the ability to procure complementary and shared information from multiple sources and robustness to noise, we ultimately utilized SNF to integrate similarities for microbes and diseases, respectively.

MVGAEW

The overall framework of MVGAEW is shown in Fig. 5. We started by integrating similarity matrixes for microbes and diseases using the SNF method. Next, we utilized improved VGAE to represent node embedding based on microbe and disease similarity matrix, respectively. Ultimately, XGBoost was adopted to predict potential disease-related microbes after the concatenation of the latent representation of each microbe and disease. In the stage of latent representation, we designed a multi-scale encoder and decoder with auxiliary tasks to enhance the representational capacity. In addition, we utilized Wasserstein distance to precisely measure two distributions. The main sections of MVGAEW were described as follows:

Fig. 5.

Overall framework of MVGAEW. A Calculate and integrate the similarities for microbes and diseases. GIP-D represents the Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarity for disease. DSS1 denotes disease semantic similarity while DSS2 denotes disease symptom similarity. GIP-M is similar to GIP-D, DFS1, and DF2 are functional similarities based on disease and drug, respectively. B Adopt an improved VGAE for latent representation with auxiliary tasks. C Utilize XGBoost for potential disease-related microbe prediction by inputting the concatenation of latent representation of each microbe and disease

Multi-scale encoder

For convenience, the adjacency matrix was set to the integrated similarity matrix , while the node features were initialized with the known association matrix . Our encoder including two shared base layers implemented by GCN and a multi-scale variational inference layer, in which two GCNs are supposed to compute the mean and the variance and then incorporated them as the latent variable . The output of the first base GCN layer can be represented as:

| 8 |

where denotes the matrix with self-loop, while denotes the matrix processed by symmetrically normalized laplacian matrix. In addition, presents the parameters of the GCN model that needs to be learned and is a non-linear activation function. Similarly, the output of the second base GCN layer can be represented as:

| 9 |

where represents the parameters of the second GCN that needs to be learned. The third multi-scale GCN layer depicts the data distribution by the mean and the log variance as follows:

| 10 |

For ith scale layer, the dimension of and are consistent, while the dimension between layers differs a lot. Considering calculating the gradient during the backpropagation, we utilized the reparameterization technique to determine the latent variables at different scales, as shown below:

| 11 |

where obeys the standard normal distribution . By means of concatenation, we obtained the output latent as follows:

| 12 |

Decoder with auxiliary task

Inspired by the diffusion model [29] and parallel neighborhood reconstruction [27], we innovatively proposed an auxiliary task, multi-order node embedding reconstruction, to enhance the robustness of VGAE. The main decoder is implemented through the inner product between latent variables with a sigmoid function to scale the output, as below:

| 13 |

To maintain dimensional consistency, we utilized two MLPs to project the dimension of into dimensions of and , respectively. The specifics of this process are described below:

| 14 |

Wasserstein distance

In order to address a common issue where the gradient from KL divergence becomes ineffective or even vanishes during later stages of training [55, 56], we instead employed Wasserstein distance (WD [27, 57]) to substitute KL divergence as the gradient from WD always existed. Accurately measuring the distance between two distributions is critical. While the KL divergence is unsymmetrical, the WD is symmetrical, making it a more suitable choice in some scenarios. In addition, the fabulous property of WD is measuring the distance of two distributions quite well when the degree of overlapping between two distributions is quite low. On the contrary, KL divergence will compute an infinite value. The only shortcoming of WD lies in the demand of large computation, which is often solved by mean of approximation in polynomial time.

For convenience, we used and to denote two probability distributions with finite secondary moment defined on . The optimal mass transportation problem with transport cost can be solved through 2-Wasserstein distance between and defined on and , respectively [58]:

| 15 |

where denotes the joint distributions of marginals and . The problem mentioned above can be perceived as a matching problem, and the Hungarian algorithm [59] is well-suited for solving it with the time complexity of . In this work, we utilized an efficient algorithm Sinkhorn for approximation, of which adopted a surrogate loss based on continuous relaxation with complexity [60].

Loss function

The loss function is formulated below [27, 28]:

| 16 |

where denotes the binary cross entropy between input similarity network and reconstruction similarity network . The second part represents the loss of WD between all-scale latent representation and the prior distribution . The third part denotes the binary cross entropy between -order node embedding and auxiliary node embedding reconstruction . In addition, we employed Adam optimizer [61] to minimize the loss function.

XGBoost classifier

In this work, we trained an XGBoost model by inputting the concatenation of the latent representations to predict the likelihood between pairs of microbes and diseases. XGBoost [30] is used for supervised learning problems as the classical boosting model in ensemble learning, which is famous for excellent scalability and high efficiency. XGBoost adopted greedy learning through a forward distribution algorithm. In detail, it will learn a CART tree for each iteration to approximate the residuals, which is implemented by a negative gradient between true values and predicted values from the combination model of the previous iteration during training, exactly as other GBDT models. The key point is that XGBoost conducted plenty of optimizations: (1) utilizing the second-order Taylor formula expansion for the optimization of the loss function, which improves its computational accuracy, (2) integrating a regularization term to reduce the form of the objective function and prevent overfitting, (3) adopting blocks storage structure to enables the processing of data in parallel by breaking it down into smaller blocks that can be processed simultaneously on multiple computing units.

Acknowledgements

Prof. L.Y. thanks to all those who maintain excellent databases and to all experimentalists who enabled this work by making their data publicly available.

Abbreviations

- SNF

Similarity network confusion

- VGAE

Variational graph autoencoder

- HMDAD

Human Microbe–Disease Association Database

- DSS1

Disease semantic similarity

- MeSH

Medical Subject Headings

- DAG

Directed acyclic graph

- DSS2

Disease symptom similarity

- HSDN

Human symptom-based disease network

- GIP-D

Disease Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarity

- GIP-M

Microbe Gaussian interaction profile kernel similarity

- DFS1

Disease-based functional similarity

- DFS2

Drug-based functional similarity

- KNN

K-nearest neighbors

- WD

Wasserstein distance

- KL divergence

Kullback–Leibler divergence

- CART

Classification and Regression Tree

- GBDT

Gradient Boosting Decision Tree

- PMID

PubMed IDs

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- CD

Crohn's disease

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- CN

Colorectal neoplasms

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the article. HZ and LY conceived and designed this paper. HZ collected and analyzed the data. HZ, HH, and LY designed the experiments and analyzed the results. HZ drafted the paper. HZ, HH, and LY revised and edited the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 62072353 and 62272065.

Availability of data and materials

The code of the model and datasets can be downloaded from GitHub (https://github.com/LiangYu-Xidian/MVGAEW, and Zenodo ). All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, its supplementary information files, and publicly available repositories.

For previously published datasets:

Ma W, Zhang L, Zeng P, Huang C, Li J, Geng B, Yang J, Kong W, Zhou X, Cui Q. An analysis of human microbe–disease associations. https://academic.oup.com/bib/-article/18/1/85/2562737?login=false#supplementary-data. (2016); Janssens Y, Nielandt J, Bronselaer A, Debunne N, Verbeke F, Wynendaele E, Van Immerseel F, Vandewynckel Y-P, De Tré G, De Spiegeleer B. Disbiome database: linking the microbiome to disease. https://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/\-articles/10.1186/s12866-018–1197-5#Sec10 . (2018); Yao G, Zhang W, Yang M, Yang H, Wang J, Zhang H, Wei L, Xie Z, Li W. Microphenodb associates metagenomic data with pathogenic microbes, microbial core genes, and human disease phenotypes. http://www.liwzlab.cn/microphenodb/-#/download. (2020); Skoufos G, Kardaras FS, Alexiou A, Kavakiotis I, Lambropoulou A, Kotsira V, Tastsoglou S, Hatzigeorgiou AG. Peryton: a manual collection of experimentally supported microbe-disease associations. https://dianalab.e-ce.uth.gr/peryton/-#/associations. (2021).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing interests.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Vitor Sousa.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hongxia Hao, Email: hxhao@xidian.edu.cn.

Liang Yu, Email: lyu@xidian.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Cénit M, Matzaraki V, Tigchelaar E, Zhernakova A. Rapidly expanding knowledge on the role of the gut microbiome in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2014;1842(10):1981–1992. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommer F, Bäckhed F. The gut microbiota—masters of host development and physiology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11(4):227–238. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. nature 2012, 486(7402):207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Holmes E, Wijeyesekera A, Taylor-Robinson SD, Nicholson JK. The promise of metabolic phenotyping in gastroenterology and hepatology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(8):458–471. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leviatan S, Segal E. Identifying gut microbes that affect human health. Nature. 2020;587:373-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Gill SR, Pop M, DeBoy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS, Gordon JI, Relman DA, Fraser-Liggett CM, Nelson KE. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Sci. 2006;312(5778):1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1124234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shoaie S, Ghaffari P, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Mardinoglu A, Sen P, Pujos-Guillot E, De Wouters T, Juste C, Rizkalla S, Chilloux J. Quantifying diet-induced metabolic changes of the human gut microbiome. Cell Metab. 2015;22(2):320–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cross ML. Microbes versus microbes: immune signals generated by probiotic lactobacilli and their role in protection against microbial pathogens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002;34(4):245–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2002.tb00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rathje K, Mortzfeld B, Hoeppner MP, Taubenheim J, Bosch TC, Klimovich A. Dynamic interactions within the host-associated microbiota cause tumor formation in the basal metazoan Hydra. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(3):e1008375. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee MH. Harness the functions of gut microbiome in tumorigenesis for cancer treatment. Cancer Commun. 2021;41(10):937–967. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang YJ, Boushey HA. The microbiome in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen L, Ley RE, Volchkov PY, Stranges PB, Avanesyan L, Stonebraker AC, Hu C, Wong FS, Szot GL, Bluestone JA. Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of Type 1 diabetes. Nat Methods. 2008;455(7216):1109–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature07336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwabe RF, Jobin C. The microbiome and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(11):800–812. doi: 10.1038/nrc3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan Q, Gu Y, Li X, Yang W, Jia L, Chen C, Han X, Huang Y, Zhao L, Li P. Alterations of the gut microbiome in hypertension. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:381. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rashid T, Ebringer A, Wilson C. The role of Klebsiella in Crohn’s disease with a potential for the use of antimicrobial measures. Int J Rheumatol. 2013;2013:610393-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Wang L, Tan Y, Yang X, Kuang L, Ping P. Review on predicting pairwise relationships between human microbes, drugs and diseases: from biological data to computational models. Brief Bioinform. 2022;23(3):bbac080. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbac080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wen Z, Yan C, Duan G, Li S, Wu F-X, Wang J. A survey on predicting microbe-disease associations: biological data and computational methods. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(3):bbaa157. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X, Huang Y-A, You Z-H, Yan G-Y, Wang X-S. A novel approach based on KATZ measure to predict associations of human microbiota with non-infectious diseases. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(5):733–739. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lei X, Wang Y. Predicting microbe-disease association by learning graph representations and rule-based inference on the heterogeneous network. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:579. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grover A, Leskovec J: node2vec: Scalable feature learning for networks. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining: 2016. 855–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Peng L, Shen L, Liao L, Liu G, Zhou L. RNMFMDA: a microbe-disease association identification method based on reliable negative sample selection and logistic matrix factorization with neighborhood regularization. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:592430. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.592430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu D, Xu H, Zhang Y, Wang M, Chen W, Gao R. MDAKRLS: Predicting human microbe-disease association based on Kronecker regularized least squares and similarities. J Transl Med. 2021;19:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-02732-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long Y, Luo J, Zhang Y, Xia Y. Predicting human microbe–disease associations via graph attention networks with inductive matrix completion. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(3):bbaa146. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hua M, Yu S, Liu T, Yang X, Wang H. MVGCNMDA: Multi-view Graph Augmentation Convolutional Network for Uncovering Disease-Related Microbes. Interdiscip Sci. 2022;14(3):669–682. doi: 10.1007/s12539-022-00514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang B, Mezlini AM, Demir F, Fiume M, Tu Z, Brudno M, Haibe-Kains B, Goldenberg A. Similarity network fusion for aggregating data types on a genomic scale. Nat Methods. 2014;11(3):333–337. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kipf TN, Welling M. Variational graph auto-encoders. arXiv preprint arXiv:07308. 2016. 10.48550/arXiv.1611.07308.

- 27.Tang M, Yang C, Li P. Graph auto-encoder via neighborhood Wasserstein reconstruction. arXiv preprint arXiv:09025. 2022. 10.48550/arXiv.2202.09025.

- 28.Guo Z, Wang F, Yao K, Liang J, Wang Z. Multi-scale variational graph autoencoder for link prediction. In: Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining. 2022. p. 334–342. 10.1145/3488560.3498531.

- 29.Kingma D, Salimans T, Poole B, Ho J. Variational diffusion models. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2021;34:21696–21707. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen T, Guestrin C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining. 2016. p. 785–794. 10.1145/2939672.2939785.

- 31.Wang F, Huang Z-A, Chen X, Zhu Z, Wen Z, Zhao J, Yan G-Y. LRLSHMDA: Laplacian regularized least squares for human microbe–disease association prediction. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):7601. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08127-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng W, Liu M, Dai W, Chen T, Fu Y, Pan Y. Multi-View Feature Aggregation for predicting microbe-disease association. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology Bioinformatics. 2021;20:2748–58. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Van der Maaten L, Hinton G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J Mach Learn Res. 2008;9(11):2579-605.

- 34.Mancuso C, Santangelo R. Alzheimer’s disease and gut microbiota modifications: the long way between preclinical studies and clinical evidence. Pharmacol Res. 2018;129:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rappaport N, Twik M, Plaschkes I, Nudel R, Iny Stein T, Levitt J, Gershoni M, Morrey CP, Safran M, Lancet D. MalaCards: an amalgamated human disease compendium with diverse clinical and genetic annotation and structured search. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D877–D887. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eckburg PB, Relman DA. The role of microbes in Crohn's disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):256–262. doi: 10.1086/510385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amitay EL, Krilaviciute A, Brenner H. Systematic review: Gut microbiota in fecal samples and detection of colorectal neoplasms. Gut Microbes. 2018;9(4):293–307. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1445957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.As A. 2019 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's Dementia. 2019;15(3):321–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan R-Y, Zhang J, Wang J, Wang Y, Li Z, Liao Y, Liao Y, Zhang C, Liu Z, Song L. Intermittent fasting protects against Alzheimer’s disease in mice by altering metabolism through remodeling of the gut microbiota. Nature Aging. 2022;2:1024–39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Cockburn AF, Dehlin JM, Ngan T, Crout R, Boskovic G, Denvir J, Primerano D, Plassman BL, Wu B, Cuff CF. High throughput DNA sequencing to detect differences in the subgingival plaque microbiome in elderly subjects with and without dementia. Investigative Genet. 2012;3(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/2041-2223-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bajaj JS, Ridlon JM, Hylemon PB, Thacker LR, Heuman DM, Smith S, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM. Linkage of gut microbiome with cognition in hepatic encephalopathy. J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302(1):G168–G175. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00190.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moreno-Indias I, Sánchez-Alcoholado L, García-Fuentes E, Cardona F, Queipo-Ortuño MI, Tinahones FJ. Insulin resistance is associated with specific gut microbiota in appendix samples from morbidly obese patients. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8(12):5672. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang HS, Zhang C, Carlyle BC, Zhen SY, Trombetta BA, Schultz AP, Pruzin JJ, Fitzpatrick CD, Yau WYW, Kirn DR. Plasma IL-12/IFN-γ axis predicts cognitive trajectories in cognitively unimpaired older adults. Alzheimer's Dementia. 2022;18(4):645–653. doi: 10.1002/alz.12399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma W, Zhang L, Zeng P, Huang C, Li J, Geng B, Yang J, Kong W, Zhou X, Cui Q. An analysis of human microbe–disease associations. Brief Bioinform. 2017;18(1):85–97. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbw005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janssens Y, Nielandt J, Bronselaer A, Debunne N, Verbeke F, Wynendaele E, Van Immerseel F, Vandewynckel Y-P, De Tré G, De Spiegeleer B. Disbiome database: linking the microbiome to disease. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1197-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yao G, Zhang W, Yang M, Yang H, Wang J, Zhang H, Wei L, Xie Z, Li W. Microphenodb associates metagenomic data with pathogenic microbes, microbial core genes, and human disease phenotypes. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2020;18(6):760–772. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2020.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skoufos G, Kardaras FS, Alexiou A, Kavakiotis I, Lambropoulou A, Kotsira V, Tastsoglou S, Hatzigeorgiou AG. Peryton: a manual collection of experimentally supported microbe-disease associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D1328–D1333. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang D, Wang J, Lu M, Song F, Cui Q. Inferring the human microRNA functional similarity and functional network based on microRNA-associated diseases. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(13):1644–1650. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou X, Menche J, Barabási A-L, Sharma A. Human symptoms–disease network. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):4212. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen X, Yan G-Y. Novel human lncRNA–disease association inference based on lncRNA expression profiles. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(20):2617–2624. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun Y-Z, Zhang D-H, Cai S-B, Ming Z, Li J-Q, Chen X. MDAD: a special resource for microbe-drug associations. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:424. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rajput A, Thakur A, Sharma S, Kumar M. aBiofilm: a resource of anti-biofilm agents and their potential implications in targeting antibiotic drug resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D894–D900. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deng L, Huang Y, Liu X, Liu H. Graph2MDA: a multi-modal variational graph embedding model for predicting microbe–drug associations. Bioinformatics. 2022;38(4):1118–1125. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ding Y, Lei X, Liao B, Wu F-X. Predicting mirna-disease associations based on multi-view variational graph auto-encoder with matrix factorization. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2021;26(1):446–457. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2021.3088342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liao Q, Wu X, Xie X, Wu J, Qiu L, Sun L. "Adversarial Residual Variational Graph Autoencoder with Batch Normalization". 2021 IEEE Sixth International Conference on Data Science in Cyberspace (DSC), Shenzhen, China. 2021, p. 40-46. 10.1109/DSC53577.2021.00013.

- 56.Cowell RG. Conditions under which conditional independence and scoring methods lead to identical selection of Bayesian network models. arXiv preprint arXiv: 2013. 10.48550/arXiv.1301.2262.

- 57.Tolstikhin I, Bousquet O, Gelly S, Schölkopf B. Wasserstein Auto-Encoders. In: 6th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2018). 2018. OpenReview. net. 10.48550/arXiv.1711.01558.

- 58.Villani C. Optimal transport: old and new, vol. 338: Springer; 2009. 10.1007/978-3-540-71050-9.

- 59.Jonker R, Volgenant T. A shortest augmenting path algorithm for dense and sparse linear assignment problems. In: DGOR/NSOR: Papers of the 16th Annual Meeting of DGOR in Cooperation with NSOR/Vorträge der 16 Jahrestagung der DGOR zusammen mit der NSOR. Springer: 1988. p. 622–622. 10.1007/978-3-642-73778-7_164.

- 60.Cuturi M. Sinkhorn distances: Lightspeed computation of optimal transport. Advances in neural information processing systems. vol 26. 2013. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2013/hash/af21d0c97db2e27e13572cbf59eb343d-Abstract.html.

- 61.Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2014. 10.48550/arXiv.1412.6980.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The code of the model and datasets can be downloaded from GitHub (https://github.com/LiangYu-Xidian/MVGAEW, and Zenodo ). All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, its supplementary information files, and publicly available repositories.

For previously published datasets:

Ma W, Zhang L, Zeng P, Huang C, Li J, Geng B, Yang J, Kong W, Zhou X, Cui Q. An analysis of human microbe–disease associations. https://academic.oup.com/bib/-article/18/1/85/2562737?login=false#supplementary-data. (2016); Janssens Y, Nielandt J, Bronselaer A, Debunne N, Verbeke F, Wynendaele E, Van Immerseel F, Vandewynckel Y-P, De Tré G, De Spiegeleer B. Disbiome database: linking the microbiome to disease. https://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/\-articles/10.1186/s12866-018–1197-5#Sec10 . (2018); Yao G, Zhang W, Yang M, Yang H, Wang J, Zhang H, Wei L, Xie Z, Li W. Microphenodb associates metagenomic data with pathogenic microbes, microbial core genes, and human disease phenotypes. http://www.liwzlab.cn/microphenodb/-#/download. (2020); Skoufos G, Kardaras FS, Alexiou A, Kavakiotis I, Lambropoulou A, Kotsira V, Tastsoglou S, Hatzigeorgiou AG. Peryton: a manual collection of experimentally supported microbe-disease associations. https://dianalab.e-ce.uth.gr/peryton/-#/associations. (2021).