Abstract

Water desolvation is one the driving force of the free energy binding of small molecules to receptor. Thus, understanding the energetic effects of solvation and desolvation of individual water molecules can be crucial when evaluating ligands poses and to improve outcome of High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS). Over the last decades, several methods were developed to tackle this problem, ranging from fast approximate methods (based on empirical functions using either discrete atom-atom pairwise interactions, or continuum solvent models), to more computationally expensive and accurate ones (mostly based on Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, such as Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory (GIST) or Double Decoupling). On one hand, MD-based methods are prohibitive to use in HTVS to estimate the role of waters on the fly for each ligand. On the other hand, fast and approximate methods show unsatisfactory agreement with the results obtained with the more expensive ones. Here we introduce WaterKit, a new grid-based sampling method using explicit water molecules which can be integrated directly in the AutoDock docking software. The WaterKit method is able to sample specific regions on the receptor surface, such as the binding site of a receptor, without having to hydrate and simulate the whole receptor structure. For these hydrated regions thermodynamics properties can be computed using the GIST method. Our results show that the discrete placement of water molecules is successful in reproducing the position of crystallographic waters with very high accuracy. Moreover, results show that WaterKit can be used to calculate thermodynamic properties of individual water molecules with accuracy comparable to more expensive fully-atomistic MD simulations Together, those results show the feasibility of a general and approximated fast method to compute thermodynamic properties of water molecules, and as a first step for a subsequent integration of complex desolvation models in dockings.

Keywords: Protein solvation, GIST, Hydration sites prediction, AutoDock, Free energy

Introduction

The role played by water in biological processes spans over multiple scales. At the macromolecule scale, water plays an essential role in determining their structure, stability and function1. It is also now widely acknowledged that water molecules have a significant effect in ligand binding, if not sometimes the main driven force in biomolecular recognition2. When a small molecule binds to its target, it also have to compete with water molecules present in the binding site. And depending on the context, water molecules will be either retained or displaced, favoring or opposing ligand binding3. The displacement of tightly bound water molecules leads to a gain in entropy4 and the overall displacement process is favorable when the ligand compensates for the loss of the water-protein interaction enthalpy, but it does not seem to be always the case5,6. This has some important implications in lead-optimization and how functional groups are affecting water positions7,8. But in some cases, water molecules are so tightly bound and conserved across family members, that they might be considered as part of the binding site.

In addition to their individual contributions, they also need to be considered as a network. Water molecules present in binding sites are forming networks through hydrogen bonds, and the removal of one water molecule or more have consequences on the position and free energy of the remaining ones in a non-additive way9. Thus, it is important to consider water molecules as a whole, and not as discrete and isolated entities, in which each individual water plays a role but depends on its interactions with the others in highly cooperative interactions.9 In the context of ligand binding, this has a direct effect on its binding, when reorganization or replacement of water networks can be often observed, contributing to the enthalpy/entropy10–12. Mutations can also disrupt water networks and affect ligand binding indirectly, via concerted changes in the water network13,14.

Over the past decades, a lot of efforts were dedicated to the development of methods for identifying and characterizing water molecules in ligand binding site. This is reflected by the number of tools available, and still increasing, for such purpose. Those methods can be classified into four different groups: (1) empirical and knowledge-based like Consolv15, WaterScore16, AcquaAlta17 and WaterDock18,19, (2) Statistical and molecular mechanics with GRID20–22, SZMAP23 and 3D-RISM24,25 in combination with placevent26 or GAsol27, (3) Simulation-based methods, either based on Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations such as the post-processing methods IFST28–30 (used in WaterMap31,32, STOW33 and GIST34–38), WATCLUST39, WATsite40–42, SPAM43 or based on Monte-Carlo (MC) simulations44, like JAWS45, grand-canonical Monte-Carlo (GCMC) simulations9 and Double Decoupling46 or by combining MC steps with MD (MC/MD) simulations47–49, and very recently, (4) deep neural network approaches made their first appearances, promising instantaneous hydration free energies from static structures50. For more detailed information about the various methods, you can refer to the following recent reviews on the subject: Bodnarchuk51, Biedermannová and Schneider52, Spyrakis et. al.3, Graves et. al.53, Nittinger et. al.54 and Hu et. al.55.

More rapid methods perform acceptable placement predictions, but they trade accuracy for speed, therefore their energy estimates are usually only qualitative56,57. Indeed, the accurate determination of individual water molecules position and properties requires more expensive calculations to sample multiple configurations, in part also due to the necessity of accounting for the water-water interactions essential to reproduce the correct water network. For that, methods based on MD simulations using explicit solvent models are considered as a de facto gold standard because they provide both positions and orientations sampling that can be used to perform quantitative estimate on thermodynamic properties, but are significantly more expensive than empirical methods. Moreover, conventional MD simulations have some significant limitations, such as the inability of sampling accurately water molecule positions in cavities that are not easily accessible and therefore have limited exchange with the bulk solvent (i.e., buried or enclosed pockets). This can lead to either the formation of vacuum or abnormal low density regions which lead to artifacts58. Different strategies and protocols have been developed to circumvent this issue9,47,48,59, at the cost of increased computational cost.

One of the principal motivations for the development of the previously presented methods is the characterization of water molecules to guide drug design efforts, and the improvement of molecular modeling predictions.

Computationally intense free energy calculation methods like Double Decoupling60,61, Free Energy Perturbations (FEP)62 or Thermodynamic Integration (TI)63, are used when precision and detailed thermodynamics are a priority for the study. They have been successfully applied for numerous sets of protein-ligand complexes64, and such positive outcome is often linked to a proper treatment of buried water molecules after alchemical transformations, which is at the origin of large hysteresis observed during calculations6,7,64–68. However, those methods are not yet suitable for high throughput applications such as docking.

In docking applications, water molecules are very often neglected for complexity reasons and the lack of a standard protocol for their treatment. In practice, water molecules are commonly treated implicitly, with the possibility for users to chose special protocols when an explicit treatment is necessary. Efforts have been made to improve the modeling of desolvation effect during docking simulations with the goal of improving accuracy of large virtual screening libraries and reducing the number of false positives. While docking software are using different strategies, studies show in average an improvement of the docking pose accuracy and energy ranking55.

Some methods are using explicit water molecules during docking69–72. Other approaches were explored by incorporating more accurate hydration information from MD simulations during docking39,73–77. or as a post-processing step for re-ranking ligands78–80.

The choice of these protocols is dependent on the number of ligands to be docked, structural data availability, time constraints, and computational resources accessibility. Inclusion of more accurate and computational expensive methods into the docking pipeline is one of the main issue of a wider adoption of such methods. In particular, the need to run MD simulations prior to docking presents computational and technical challenges that can discourage common users to incorporate hydration information into their docking protocols, and limits its general applicability in a high-throughput fashion.

Having an accurate description of the solvent-related energy components of the target structure during docking is essential to increase the accuracy of results, and reduce false positives. The motivation for development of WaterKit was the exploration of an alternative physics-based method to rapidly sample water configurations and generate high quality energy models of individual molecules. Such method needs to provide comparable accuracy to MD-based methods, providing full thermodynamic profiling of multiple hydration shells with much smaller computational needs. The protocol described here has been designed to be compatible and easily integrated with the AutoDock docking protocol81. Here we describe the proof-of-principle of its implementation in Python based on existing tools such as AutoGrid and OpenMM.

Materials and Methods

Dataset.

To design the method and assess its performance, we compiled a dataset of 10 proteins from the DUD-e dataset82, representative of different target topographies (deep vs. shallow) and topologies (solvent-accessible vs. closed). For nine of them, the PDB entries in DUD-e dataset were used: coagulation factor X (fa10, PDB id: 3kl683), FK506-binding protein 1A (fkb1a, PDB id: 1j4h84), heat shock protein HSP 90- (hsp90, PDB id: 1uyg85), leukocyte adhesion glycoprotein LFA-1 (ital, PDB id: 2ica86), fatty acid binding adipocyte (fabp4, PDB id: 2nnq87), neuraminidase (nram, PDB id: 1b9v88), thymidine kinase (kith, PDB id: 2b8t89) and cyclooxygenase-2 (pgh2, PDB id: 3ln190). For HIV-1 protease (hivpr), the structure used in the DUD-e (PDB id 1xl291) is characterized by an asymmetric conformation of the flap loops induced by the binding of an atypical ligand91, which prevents the binding of the key structural water 301. Therefore this structure was replaced with 1hpx92 and 2zye93, both binding with the same potent inhibitor KNI-272. These structures were used to assess the impact of the backbone amide geometry of ILE50 and ILE50’ on the water 301 position. Finally, the widely studied streptavidin-biotin complex (PDB id: 1stp94) was also added to perform a comparison with results reported for other desolvation estimate methods, such as the WaterMap method31.

Structure preparation.

The preparation of the target structures for both methods was done using AmberTools19 toolkit95. Crystallographic water molecules and Amber non-standard residues were removed from the receptor, while ions were kept. Hydrogens were added using LEaP and N- and C-terminal charge patches applied according to the standard Amber protocol95. Histidines were modeled in the default neutral form (HID) with one hydrogen atom on nitrogen. For hivpr, residue Asp25 of chain B was modeled in the neutral form (ASH)96,97. Disulfide bridges were automatically detected during the preparation using pdb4amber (https://github.com/Amber-MD/pdb4amber) and built by LEaP. In order to use AutoGrid4 to calculate the grid maps, parmed (http://github.com/ParmEd/ParmEd) was used to convert output parameter, topology, and coordinate files, to the PDBQT format retaining Amber atom types and partial charges previously defined. Unlike the standard AutoDock protocol81, an all-atoms model is used and non-polar hydrogen atoms were kept (i.e., instead of being merged with heavy atoms).

WaterKit protocol.

The WaterKit simulation protocol is an iterative hydration process of a target structure, and can be summarized in four main steps (Fig.1): 1) identify and rank of all initial available hydrogen bond donor and acceptors (anchor points, AP) on the target structure; 2) for each anchor point a spherical model is used for the initial placement of individual water molecules, which are then converted to an explicit model to sample their orientation; this process is repeated until all available target anchor points are saturated (first hydration layer); 3) previously placed water molecules are then used to identify new anchor points to build multiple hydration layers, which are added until either the user-defined number of layers is placed, or there is no free volume left; 4) perform a quick energy minimization to relax protein-water and water-water interactions.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the four main steps of the WaterKit sampling protocol: 1) identification of anchor points, and affinity grid maps preparation 2) placement order (a) and sampling (b and c) methods used to generate an ensemble of discrete water molecule conformations; 3) minimization of the fully hydrated system; 4) the estimation of the thermodynamic properties; of water molecules using GIST.

These steps produce a frame, and by repeating the process multiple times it is possible to generate an ensemble in which different water molecule configurations are sampled.

Anchor points identification.

The first step of the protocol is the identification of the locations for the initial placement of water molecules (Fig. 1). For that, hydrogen bond anchors points (AP) are defined on the target surface, using opportune SMARTS patterns (File S1). Two different methods have been tested for the selection of AP: one more strict including only standard HB acceptors and donors , and another more permissive which includes also non-polar hydrogens . For each AP, hydrogen bond anchor vectors (AV) with a length of 2.8 Å are generated on the heavy atom, with number and angles varying according to its valence and hybridization. Initially, the pool of APs contains only the anchor points on the dry target which are used for the placement of the first hydration layer. Then, each newly added water will add its APs, which will be used to build subsequent layers.

Sampling.

The sequential placement of water molecules (Fig. 1, steps 2a, 2b and 2c) is performed in a stochastic fashion. At each step, a probability is calculated based on the energy using the Boltzmann distribution. This probability associated to each state , either a placement order, a position or an orientation of a certain water molecule is obtained by the following equation (eq. 1):

| (1) |

where is the probability of the state and are the energy of the state and , respectively, the Boltzmann constant (1.9872041 × 103 kcal/mol/K), the temperature in Kelvin, and the total number possible states. A state is first randomly selected based on its probability , then accepted or rejected by evaluating its energy with a modified Metropolis criterion (eq.2):

| (2) |

where is the acceptance ratio. With being a random number from a uniform distribution [0, 1], the state is accepted if , or rejected otherwise.

Anchor points

The order in which initial water molecules are placed on the protein surface is calculated using equations 1. For each AP, a pool of grid points is defined, containing the most favorable energy location at a distance between 2.5 and 3.6 Å from the AP and an angle ≤ 90° from the AV. Thus, while energetically favorable APs will have higher chance to be filled first at the expenses of those with less or no favorable positions available, different placement orders can still be sampled during the simulation.

Spherical water placement

The initial location of each water is identified by placing a spherical water molecule (Fig.1 step 2), and calculating its energy according to the grid maps. The choice of the position of a spherical water molecule is calculated using the energy of the grid points pool defined around each AP using the same geometric criteria as the placement order. The position is then picked based on Boltzmann probabilities in eq. 1 and accepted or rejected using equation 2.

Explicit water placement

The accepted spherical water model is converted to a TIP3P explicit water, and its orientation is chosen by calculating the energy of a pre-calculated set of 9897 uniformly distributed orientations98. These energies are used to calculate the probability of each orientation based also on in eq.1. Once an orientation is accepted, the grid maps are updated to include the information of the newly added water, and its APs are added to the pool of anchor points.

Iterations

The sampling process is repeated by saturating all the available APs on the protein or the previous hydration layer, until no water molecules can be added into the grid or the maximum number of hydration layers is reached. For all the systems analyzed here, was used, i.e.: three hydration shells on the receptor surface.

Energy minimization

Once the placement of all water layers is completed, the system is minimized using OpenMM99. Protein heavy atoms are restrained with a 2.5 kcal/mol/Å2 force constant, while water molecules are free to move. The minimization is done with a non-bonded cutoff of 9 Å and no periodic condition. The following minimization steps were tested: 50, 75, 100, 125.

Ensemble generation

The whole procedure, from the identification of the AP to the energy minimization, is repeated 10,000 times, generating an ensemble of individual frames representing different water configurations. This ensemble was used to estimate the desolvation free energy using the standard GIST method (i.e., in place of the MD trajectory used in the standard protocol).

Affinity grid maps calculations.

Grid maps were used to calculate water-protein and water-water interaction energies during the placement and orientation of each individual water molecule. Similarly to what is done for the AutoDock docking protocol,100, energy values were obtained by trilinear interpolation of the grid values, providing a significant performance improvement compared to pairwise energy evaluations. Affinity grid maps were calculated with different energy models using AutoGrid4100 and AutoDock-Vina 1.2101. When using AutoGrid4, the AutoDock4 forcefield was replaced with the Amber ff14SB force field102 to model the protein, ions, if present, and water molecules using the TIP3P water model103. When using AutoDock Vina, the standard non-directional, donor-acceptor oxygen probe (O_DA) from the Vina force field was used. Each time a water molecule is accepted, maps are updated by using a pre-calculated single water molecule grid box that is integrated and interpolated into the existing target maps.

Directional maps using TIP3P model

To model the directional interaction between the protein and an explicit water molecule we calculated two separate maps for oxygen and hydrogen probes. For that, two new atomic probes OW and HW were defined to model oxygen and hydrogen interactions, respectively, basing on the TIP3P water model in the ff14SB force field. According to that, the OW probe combines the vdW and electrostatic terms (−1 negative charge), while the HW probe included only the electrostatic term (+1 positive charge), since in the ff14SB force field, hydrogens have no explicit van der Waals term. AutoGrid was used to calculate maps for each probe, the electrostatic map was combined by applying the opportune coefficients from the TIP3P water model: −0.834 for oxygen; 0.417 for hydrogen atom.

Spherical map using TIP3P model

Directional grid maps calculated with OW and HW probes from the TIP3P model were combined to derive a non-directional interaction grid map, which was tested for the placement of spherical water molecules. To calculate the values for this map, at each grid point the predefined set of 9897 orientations was placed and their energy interpolated from the OW and HW grid maps. Then, the energy of a water molecule at a given position in the grid was calculated as the Boltzmann-weighted average energy of the orientation ensemble (eq. 3):

| (3) |

where and are the energy and the probability associated to the orientation , respectively, and the total number of orientations sampled (9897 orientations). Finally, only the value is stored in the grid map, while no directional information is conserved.

Spherical map using AutoDock-Vina

Another spherical map was calculated using the O_DA atomic probe, which defines a non-directional donor-acceptor oxygen in the AutoDock Vina empirical force field104. The force field includes a van der Waals-like potential (a combination of two attractive gaussian terms and a repulsion term), a non-directional linear hydrogen-bond term, a hydrophobic term, and no electrostatic term. Due to the lack of directionality for both donor and acceptor hydrogen bond terms, the O_DA probe is not affected by the position of explicit polar hydrogen atoms in the target structure (Fig. 2). This provides a clear advantage when sampling interactions around residues with disordered hydrogens such as those in hydroxyl (Ser, Thr, Tyr), thiol (Cys), and protonated amine groups (Lys, N-terminus). One potential downside is the complete lack of directionality also for the donors. This grid map was calculated using AutoDock-Vina 1.2101.

Fig. 2.

Difference between spherical maps using (A) AutoDock-Vina non-directional donor-acceptor oxygen probe (O_DA) and (B) TIP3P water model for the quaternary amine group (R-NH3+) in lysine residues. The spherical maps were contoured at 85 % of the most favorable energy value, corresponding to −0.22 and −11.56 kcal/mol for the AutoDock-Vina O_DA probe and TIP3P model, respectively.

Grid map parameters

For all targets, cubic grid boxes were centered on the ligand binding sites of interest, and their size set to 65 × 65 × 65 points, using the default grid spacing of 0.375 Å (resulting in 24.375 Å-side cubes). The default AutoGrid4 smoothing factor was disabled, and the dielectric constant was set to 1.

Molecular dynamic simulations.

System preparation.

The crystallographic structures of the targets were all prepared using CHARMM-GUI105. All non-standard residues (including ligands) and crystallographic water molecules were removed, while ions were kept. Receptors were modeled using Amber ff14SB forcefield. Missing N- and C-terminal parts were not reconstructed and charged N- and C-terminal patches were applied according to the standard Amber protocols. Disulfide bridges patches were also applied when necessary. For hivpr, the side chain of Asp25 in all chains B (PDB ids: 2zye, 1hpx) was modeled in the neutral form (Amber residue nomenclature: ASH)96,97. For all other systems, all aspartate and glutamate side chains were modeled in the deprotonated (negatively charged) form, while lysine and arginine sidechains were modeled as protonated (positively charged). Histidine residues were protonated on the position (Amber residue nomenclature: HID). Finally, each system was build using the tleap module in the Amber package. Protein targets were placed in an orthorhombic box sized such that faces were placed at 14 Å from the closest protein atom, and solvated with explicit TIP3P water molecules. The water box was placed using the solvatebox command with a closeness of 0.5, instead of 1.0, in order to accelerate the diffusion of water molecules inside the ligand binding pockets. To neutralize charges, Na+/Cl− counter-ions were added avoiding the binding site volume to prevent perturbing water molecules placement.

MD simulation protocol.

MD simulations were performed using pmemd.cuda from AmberTools 19 toolkit95. Periodic boundary conditions were applied for the simulations systems. The SHAKE algorithm106 was applied to all hydrogen-heavy atom bonds and SETTLE for bonds belonging to water molecules107, and an integration time-step of 2 fs was used for all simulations. Long-range electrostatic interactions were computed with Particle Mesh Ewald summation method108 with a cutoff of 12 Å. Prior to running the MD simulations, water positions were optimized while keeping the protein constraints with 100 kcal/mol/Å2 force constant, and energies minimized with 1000 steps of Conjugate Gradient (CG), then gradually heated up to 600 K over 46 ps, followed by 250 steps of CG, then heated again to 300 K over 50 ps. Following the GIST protocol, 2.5 kcal/mol/Å2 restraints were applied on the protein heavy atoms to prevent the protein to translate and rotate during the simulation, interfering with the volume discretization. Same restraints were applied to counter-ions to prevent them moving into the binding site and generate artefacts during the GIST analysis. Each system was then energy minimized with 2000 steps of CG, gradually heated to 300 K over 30 ps, and followed by an equilibration step of 1 ns in NPT condition and maintained at 1 atm and 300 K, using the Langevin barostat and thermostat, respectively. The average size of the box was calculated and a production run of 30 ns was performed in NVT condition at 300 K, using the Langevin thermostat. To improve convergence, production runs were extended to 100 ns for streptavidin, hivpr, and nram, and to 200 ns for fabp4 protein. Conformations were saved every 1000 steps (i.e., 2 ps) for the subsequent analysis. Finally, MD simulations were repeated for each system to generate 3 replicate trajectories.

Grid Inhomogenous Solvation Theory (GIST).

The GIST method estimates the thermodynamics properties of water in the context of a protein receptor34–38. Thermodynamics properties are derived from MD trajectories by discretizing a defined region of interest, such as a ligand binding site, into voxels in a 3D grid with a resolution of 0.5 Å2. Similarly, ensembles generated with WaterKit were processed as MD trajectories using the standard GIST protocol. Different types of grids are calculated to describe solvent-related thermodynamic properties of the system (all expressed in kcal/mol/Å3): solute-water enthalpy , water-water enthalpy , translational entropy and orientational entropy . Water oxygen and hydrogen densities (gO and gH, respectively) can also be calculated and expressed as the ratio between the measured grid density over the bulk density (i.e.: density/bulk density units). Therefore, voxels with a value of 1, means that the density is equal to the bulk density. In this study, the desolvation free energy grid was obtained using the following equation34–36:

| (4) |

GIST grids were generated using the CPPtraj tool from AmberTools 1995 by processing MD trajectories with a grid spacing of 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 Å. From MD trajectories, 30,000 frames (10,000 × 3 replicates) were extracted and analyzed for fa10, fkb1a, hsp90a, ital, kith, and pgh2 systems. Due to convergence issues, the GIST analyses for hivpr, nram, fabp4 and streptavidin systems were extended to include 100,000 frames (Fig. S18, S22, S16, S24). The grids were manipulated using the Python package gridData from MDAnalysis109,110

Hydration sites.

Identification.

In order to compare GIST results obtained from WaterKit ensembles and MD trajectories, we relied on the positions of high density water molecules, or called hydration sites, using the water oxygen density grid gO. The position of the first hydration site is identified by selecting the voxel with the highest water oxygen density. All the voxels within 2.5 Å of the first hydration site are then excluded from any future consideration. Then, the process is repeated for the next highest density voxel available, until no more voxels with density higher than 0.1 density / bulk density are available.

Thermodynamic properties.

Thermodynamic quantities and at each hydration site were calculated by summing all the grid points within a radius of 1.4 Å around it, and Gaussian-weighted by their distance using a value calculated as: . The Gaussian-weighting ensured that voxels in close proximity of the hydration site centers had more weight than distant ones. GIST grid energy values were converted to kcal/mol by multiplying them by the voxel volume (0.125 Å3).

Prediction evaluation.

The accuracy of WaterKit to correctly identify hydration sites, as well as predicting their correct thermodynamic properties, was measured by comparing it to the values obtained from the MD simulations. The continuous evaluation of predictions and the performance comparison with the MD simulation results were used to test the different combinations of parameters for WaterKit, and ultimately for the the choice of the optimal parameters.

Placement prediction.

Due to the intrinsic instability of water molecules distal from the protein surface, comparisons were focused on the hydration sites present in the first hydration shell of the ligand binding site. The first hydration shell around ligands was defined using a cutoff of 5 Å111 from any ligand heavy atoms using the refined PDBbind dataset (v2018)112. Ligands with serious steric clashes with the protein (< 2 Å distance between heavy atoms) were ignored.

Additionally, hydration sites identified as trapped (i.e., unable to exchange with the bulk solvent) were excluded from the analysis due to known convergence issue found in MD simulations47. To identify them, bulk solvent accessibility was determined using MSMS113 with the default probe radius (1.5 Å), except for fabp4 to allow characterizing its enclosed pocket (1.0 Å). For hsp90α, the tightly bound hydration site W1 was manually set as bulk-accessible.

The quality of the predictions with respect to MD simulations was assessed by defining two metrics, the True Positive Rate (TPR, sensitivity, or recall), and the Positive Predictive Value (PPV, precision), calculated as following:

| (5) |

where (true positive) is the number of correctly placed water molecules within 1.0 Å of a hydration site found in the simulations; (false negative) is the number of predicted hydrations in the simulation without an equivalent found by WaterKit and (false positive) the number of hydration sites found by the WaterKit simulation but not in the simulation.

The precision (PPV) provides the fraction of hydration sites found by WaterKit that are also present in MD simulations. The sensitivity (TPR) provides the fraction of hydration sites present in MD simulations that are also found by WaterKit. Sensitivity and precision were reported for both all hydration sites found in the ligand binding site.

Energy prediction.

Reference values for the thermodynamic quantities and for each hydration site were obtained by averaging results from the MD simulation triplicates. In the case where MD simulations were compared to each other, average values were obtained by excluding the one compared. The predictions were compared by calculating the RMSD (in kcal/mol), as well as the coefficient of determination , Kendall , Spearman’s , (calculated using the corresponding Scipy functions114). The energy evaluation was done using both all the hydration sites and the ligand binding site subset.

Results and discussion

The performance of the WaterKit method was evaluated using the MD simulations as a reference, analyzing 9 systems from the DUD-e dataset82 (fa10, fkb1a, hsp90α, ital, hivpr, fabp4, nram, kith and pgh2), plus the streptavidin-biotin complex, which water molecules have been extensively characterized and discussed in the literature115–121. The WaterKit method was designed to facilitate the generation of trajectories similar to those obtained with MD simulations, so that they can similarly used as input for the Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory (GIST) method. By sampling positions and orientations of individual water molecules, this approach can be used to calculate their individual thermodynamic properties, such as solute-water and water-water enthalpies (, respectively), and translational and orientational entropies (, respectively).

MD simulations.

To measure the variability among different simulations and obtain a robust reference, triplicates were performed for all the proteins, and compared to each other (Fig. 3) By using progressively longer MD trajectories (from 100 to 30,000, corresponding to 0.1 ns to 30 ns), the GIST analysis shows that 30 ns is sufficient to achieve an adequate degree of convergence, except for proteins hivpr, nram, fabp4 and streptavidin (Fig. S18, S22, S16, S24). MD trajectories had to be extended to 100 ns (100,000 frames) for all triplicates of streptavidin, nram and hivpr, and to 200 ns (200,000 frames) for fabp4 protein. While satisfactory convergence was reached with 100 ns for the streptavidin protein, longer MD trajectories did not yield better convergence for nram, hivpr and fabp4 proteins (Fig. S18, S22, S16, S24).

Fig. 3.

Results for each WaterKit model tested and averaged over all the studied systems (except PDB 1hpx for hivpr protein), varying the hydrogen bond anchor points definition (: polar HB donor/acceptors only; : polar and non-polar hydrogen atoms), the spherical water model (TIP3P water, Vina oxygen donor-acceptor) and the number of minimization steps. All the hydration sites identified in the ligand binding pocket were compared to MD simulations. The water placement with a distance cutoff of 1.0 Å was evaluated using the True Positive Rate (TPR) (sensitivity), the Positive Predictive Value (PPV) (precision). The different GIST energy components, as well as , were compared using the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and the coefficient of determination (r2).

Despite system-specific convergence issues, the results showed that the different replicates were overall successful in identifying most of the common hydration sites across the different MD simulations, with a sensitivity of 0.65 and a precision of 0.83. Moreover, high correlation coefficients r2 were obtained for each energy component, with values ranging from 0.75 for to 0.88 for . The average RMSD values observed are lower than 1 kcal/mol for , and , and around 0.15 kcal/mol for and . Such difference of orders of magnitude between the component terms are in agreement with previous studies73,122–125 reporting the predominance of enthalpy terms over entropy ones for water molecules, and consequently on their .

In our results for MD simulations, observed values for the enthalpic terms span over a wider range of energy, about −20 kcal/mol for the most favorable hydration sites, compared to the entropic terms that did not exceed −3 kcal/mol. The largest estimated total entropic costs was around 6 kcal/mol, which is higher than the empirical upper bound of 2.1 kcal/mol at 300K proposed by Dunitz126 for transferring a water molecule from the bulk to a binding site. This is likely a consequence of the protein flexibility restraints imposed by the GIST protocol, resulting in limited degrees of freedom for water.

Selection of the WaterKit model.

Different combinations of the parameters and sampling methods in WaterKit were tested for their accuracy in reproducing the GIST results obtained with MD simulations. The comparative analysis showed that optimal performance was achieved with only standard hydrogen bond anchor points , a non-directional interaction model for the initial placement of spherical water molecules (i.e.: based on the Vina O_DA interaction probe), and a final energy minimization of 100 steps.

Anchor points.

Water molecules were either placed on only polar anchor points using a predefined set of SMARTS patterns, or by including also non-polar hydrogen atoms . Results show that seems to achieve a marginally better agreement with the with MD simulation results (Fig. 3). This is not surprising given the Boltzmann weighted sampling scheme applied, since even when considering all hydrogens the lower energies associated to non-polar ones made them less likely to be selected for the initial spherical water placement.

Spherical water placement.

For the initial placement of spherical water molecules on APs, two different map models were tested, using either the one based on the explicit TIP3P water molecule with the electrostatic term, or the (O_DA) acceptor/donor probe from the Vina force field without electrostatic term. Surprisingly, the non-directional Vina O_DA probe resulted in better placements and energy predictions than the more accurate directional model (Fig. 3). Likely, the lack of both hydrogen directionality and electrostatic contributions provided an advantage to the Vina O_DA model, making it less susceptible to the structural bias associated with discrete orientations of disordered hydrogen atoms (i.e.: hydroxyls and amines, Fig. 2).

Minimization.

In the MD simulations, relatively soft restraints are applied on the target atom positions, while all water molecules free to move. Conversely, in WaterKit, both the target structure and previously placed water molecules are kept rigid during the entire process, in order to use the pre-calculated grid affinity maps.

This results in a reduced modeling accuracy of the contribution, with respect to the , because due to the sequential layer placement, newly placed water molecules can only take into account interactions within the current layer or the underlying ones. To mitigate this, we added a final minimization step (Fig. 1 step 4) allowing both water molecules and target atoms to relax within similar restraints used for the MD simulations. While this step allows only minimal adjustment of the water coordinates, it can remove possible strains added by the progressive water layers placement. In fact, this step improved the quality of water-water interactions () as well as the entropic components ( and ), resulting in higher r2 and lower RMSD values. Results show that 75 to 100 steps were sufficient to achieve optimal performance, while minimal to no gain was found beyond that (Fig. 3 and Fig. S1 for more details).

Prediction of the selected model.

When comparing WaterKit hydration sites within a stringent 1.0 Å cutoff from MD hydration sites, the method was able to achieve on average a recall (TPR, sensitivity) of about 0.59 and a precision (PPV) of about 0.63 (Fig. 3). Using a cutoff 1.2 and 1.4 Å (corresponding to a uncertainties up to about half the diameter of a water molecule), the average recall increased to 0.71 and 0.76 and the average precision to 0.76 and 0.81, respectively (Fig. S2). These values are very close to those measured across the individual MD simulation replicates, which achieved comparable recalls of 0.64, 0.71 and 0.79 when using a cutoff of 1.0, 1.2 and 1.4 Å, respectively (Fig. S2). Interestingly, the precision for MD simulation replicates was about 0.82, 0.87 and 0.92 for 1.0, 1.2 and 1.4 Å cutoffs, respectively.

In terms of energy estimates, the average performance of the best WaterKit model (Fig. 3, / Vina / 100 min. steps) in predicting individual thermodynamic components across the entire dataset using the most stringent distance cutoff (1.0 Å) was the highest for and , and the lowest for .

Conveniently, the low predictive power for results in a low error amplitude (0.52 kcal/mol), due to the relatively small energy range of this term, and in agreement with what observed also in the reference MD simulations. As a consequence, errors in this term will have only limited impact on the accuracy final predictions. Conversely, since is the dominating thermodynamic term, one might argue that this term alone could be used to calculate a sufficiently accurate estimate of the hydration sites . To test this hypothesis, MD-derived hydration sites were used to calculate energies by interpolating the TIP3P model and AutoDock Vina spherical maps, then values were compared to those obtained with MD trajectories. Results yield little to no correlation between them (Table S1), showing that using a crude single-point probe without proper sampling is insufficient to reproduce the full spectrum of thermodynamic properties obtained by processing the results of multi-state simulations.

Case studies.

Overall, a good agreement is found with the MD simulations for most thermodynamic terms (Fig. 4A, and Fig. S3 and Fig. S10–S14 for more details), including the total free energy , 1.39 kcal/mol RMSD). More in detail, for ranged from 0.67 to 0.92 for 8 of the 11 systems considered, with RMSD values ranging from 0.61 to 2.18 kcal/mol. Among all terms, and are the most accurately predicted. In 9 out of 11 systems, values were ≥ 0.70, with the exception of two systems in which it was lower than that (≥ 0.63). Similarly, 7 out of 11 systems showed RMSD values below 2.0 kcal/mol. A very similar trend is found also for for both and RMSD. On contrary, the term shows the biggest divergence between WaterKit and MD simulations, with poor (< 0.5) for 9 systems, except for kith and ital. These errors were mitigated by RMSD always smaller than 1.0 kcal/mol. Similarly small RMSD errors were found for the entropy terms ( and ), but associated to nearly systematically better values. As previously noted, the results suggest that significantly smaller range of energies for and compared to is a general rule. low RMSD values for , and entropic terms ( and ) is also observed for each system studied.

Fig. 4.

(A) Results for each system studied using the best WaterKit model: polar Hydrogen Bond Anchors (HBA); positions identified using the Vina O_DA spherical water model interactions relaxed with 100 steps of minimization. All hydration sites identified in the ligand binding pocket were compared to MD simulations. The number of True Positive (TP) corresponds to the total number of water molecules correctly identified by WaterKit, using a distance cutoff of 1.0 Å. The different GIST energy components, as well as , were compared using the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and the coefficient of determination (). RMSD and calculated for the MD triplicates is reported as a reference. (B) The water placement was evaluated using the True Positive Rate (TPR) (sensitivity) and the Positive Predictive Value (PPV) (precision) metrics. The sensitivity and precision were calculated on all the identified hydration sites, as well on different set of hydration sites based on their energy from −5 to −2 kcal/mol.

The data gathered in the analysis shows that energy prediction accuracy is highly correlated to the performance accuracy. Given the relatively small contribution from the absolute values of the other terms, the data suggests that an accurate estimate of might be sufficient to identify and characterize strongly bound water molecules.

A detailed analysis on individual system shows that WaterKit predictions can diverge significantly from MD simulations in a some cases. Divergences are observed for proteins kith ( RMSD 2.18 kcal/mol), nram ( RSMSD 1.90 kcal/mol), fabp4 ( RMSD 2.02 kcal/mol) and hivpr ( RMSD 1.83 kcal for 1hpx structure and 0.54 for structure 2zye). Similarly, the RMSD for those systems are about 2.21 to 2.78 for fabp4, hivpr (1hpx), nram and kith, showing again that inaccuracy in is mainly driven by inaccuracies.

In term of water placement prediction, results indicate that WaterKit is able to find the most favorable hydration sites present in the MD simulations with high precision (PPV) and only a minimal number of false positive. However, not all the favorable hydration sites present in MD simulations are found by WaterKit (Fig. 4B). When considering only favorable hydration sites (≤ −5 kcal/mol), the average sensitivity (TPR) and precision (PPV) are 0.47 ± 0.21 and 0.89 ± 0.24, respectively. The average precision goes down to 0.60 ± 0.16, when considering hydration sites with an Esw ≤ −2 kcal/mol and to 0.58 ± 0.07, when all hydration sites are included. The average sensitivity is less influenced by the energy cutoff, and oscillates between 0.47 and 0.56.

The analysis of individual systems provided useful information on the performance of WaterKit with respect to MD simulations. All simulations were performed in absence of bound ligands, which have been used afterwards to provide insight on the interpretation of the results for their possible use for drug design. For all systems, hydration sites were identified using an oxygen density gO ≥ 0.1 of bulk density, and the match of WaterKit results with MD results was evaluated using the strictest cutoff (1.0 Å).

Leukocyte adhesion glycoprotein LFA-1 (ital).

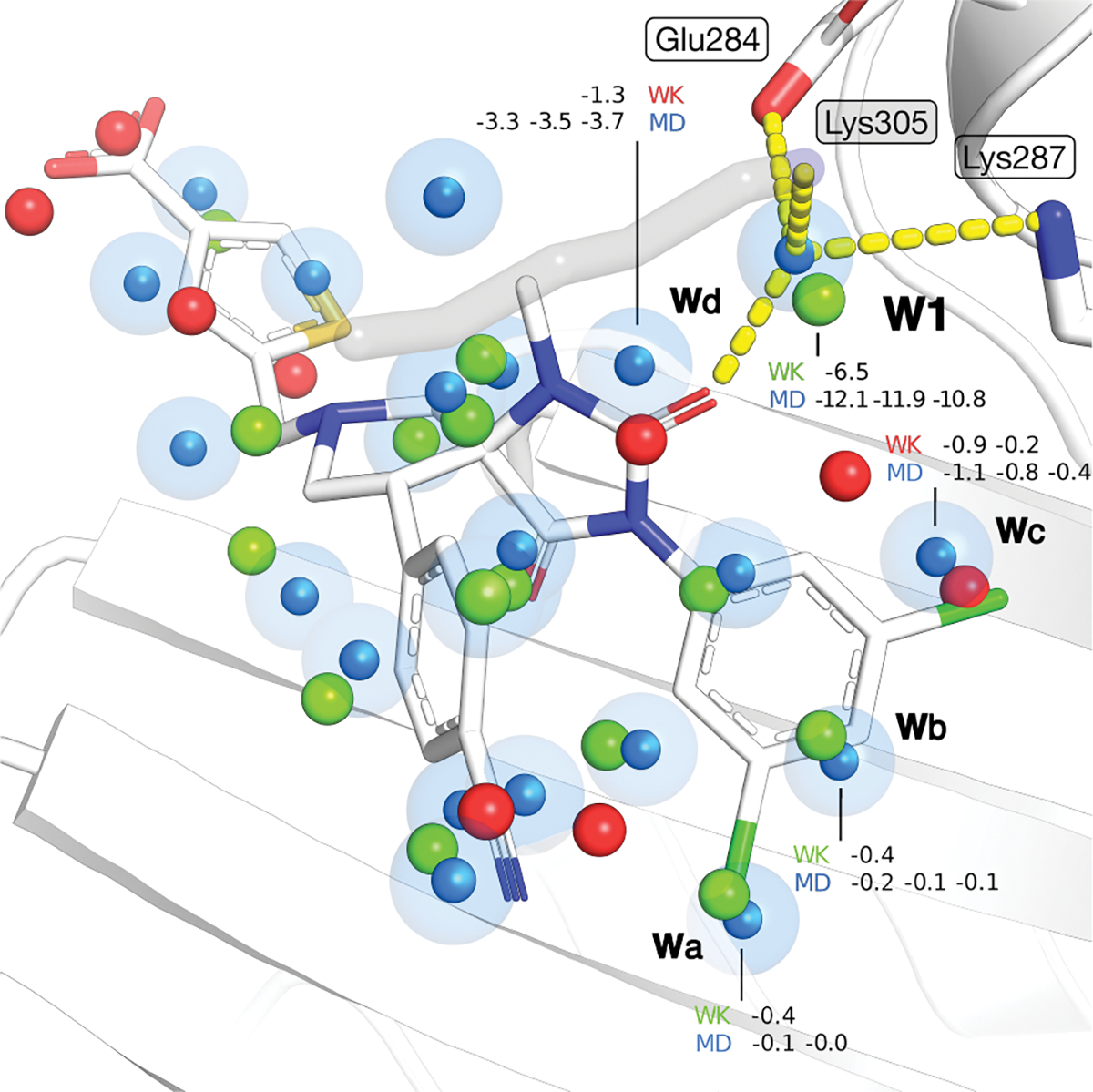

The I domain of the integrin alpha-L (ital) is about 175 residues long folded into a central -sheet that is surrounded by -helices, forming a Rossman fold. The crystallographic structure (pdb id: 2ica) shows that the binding site is widely open to the bulk solvent, but is mostly covered by non polar residues. Therefore, interactions between the ligand and the protein are mainly hydrophobic in nature except for the interaction of the urea carbonyl in the ligand with Glu284, Lys287 and Lys305 through a bridging water molecule.

The overall results for ital show that WaterKit is predicting accurately with a of 0.92 and a RMSD of 1.25 kcal/mol against the MD average. In comparison, RMSD and between MD triplicates are about 0.37 kcal/mol and 0.98 for (Fig. 4A, and Fig. S3 and S8). In line with previous observations (Fig. 4A), a poor correlation is obtained for term, despite a RMSD < 1 kcal/mol. Predictions were calculated over 33 hydration sites with an equivalent found in MD simulations. In total, 67 hydration sites were found in MD simulations, from which only 45 are common to all MD triplicates. Interestingly, WaterKit correctly predicted the position of water molecules in mostly hydrophobic regions, some of which appear to map on conserved features found in the ital ligand structures. In particular, hydration sites Wa, Wb and Wc are located in a fully hydrophobic part of the ligand binding pocket, and their positions overlap closely with the 1,3-dichlorobenzene moiety (Fig. 5), Their interactions with the protein are predicted to be weakly favorable by both methods (Fig. 5) suggesting that they have been easily displaced by the ligand, possibly with an favorable entropy contribution the overall binding affinity. Water Wd, which is predicted to be involved in a water network involving the chrystallographic water W1 (W324 in the PDB structure) is predicted to be more stable, and it is displaced by one of the ligand carbonyl groups. In the case of the crystallographic water W1, it position in a bridging role was still accurately predicted with the simulations performed in absence of the ligand with both WaterKit and MD (Fig. 5). The predicted with WaterKit (−6.5 kcal/mol) is smaller than the MD averages (−11.6 kcal/mol), possibly due to the higher entropy contribution estimates of the constrained simulation mentioned previously. Interestingly, other conserved water molecules predicted by WaterKit but not by MD simulations coincide with ligand features such as the nitrogen of benzonitrile and the carboxythiophene groups.

Fig. 5.

Hydration sites found in ital ligand binding site (PDB: 2ica) using MD simulations (triplicates) and WaterKit. Hydration sites found in MD simulation are represented as blue spheres. Hydration sites found with WaterKit are colored in green (found an equivalent in MD simulations) and red (no equivalent found in MD simulations) and represented as spheres. The protein is shown as cartoon (white) with side-chains in sticks. The co-crystallized ligand is colored in orange and represented in stick.

Heat Shock Protein 90α (hs90a).

The N-terminal domain of the Heat Shock Protein 90α (hsp90α, PDB 1uyg) is composed of 9 helices and an 8 strands antiparallel -sheet that fold together into an sandwich. The ligand binding pocket is located on the helical face at the center and it is widely open into the hydrophobic core of the structure. In it’s open conformation127, a channel coming from the ATP binding site is present under this helix. Although mainly hydrophobic in nature, it contains numerous water molecules which play a key role in ligand binding, and have been exploited for inhibitors design73,128. Four water molecules, named W1 to W4 in this study (Fig. 6), are conserved in the same position in several crystallographic complexes127,129–132. These water molecules are part of a hydrogen bond network involving Asp93, Asn51, Ser52, Thr248 and Gly97. The role they play in ligand affinity and their displacement were studied in detail133,134, making hsp90α also an ideal case for assessing the capabilities of the sampling method implemented in WaterKit. MD simulations identified 80 hydration sites found in at least a replicate, and 57 common in all triplicates. Of these sites, 44 and 27 are found also by WaterKit, respectively. Both MD simulations and WaterKit are able to identify the conserved water molecules W1-W4 (Fig. 6) matching experimental coordinates very closely (< 0.5 Å), but their ranking differs. In MD simulations, W1 is correctly identified as the most stable (average : −16.1 kcal/mol), while W2-W4 are considered roughly equivalent within 1 kcal/mol (: −6.8, −6.1 and −5.8 kcal/mol, respectively). On the other hand, WaterKit ranks them as following: W1 < W4 < W2 ≈ W3, with at −14.4, −10.2, −4.1 and −4.0 kcal/mol, respectively. Interestingly, the latter ranking is very close to what previously reported from a study based on IFST (a method analogous to the GIST approach used here33,73,135), which reported for W1, W4, W3 and W2 to be −23.19, −16.11, −11.57 and −8.43 kcal/mol, respectively73.

Fig. 6.

Hydration sites found in hsp90α ligand binding site using MD simulations (triplicates) and WaterKit (PDB: 1uyg). (A) comparison of MD and WaterKit predictions; (B) WaterKit hydration sites near the purine ring; (C) MD hydration sites near the purine ring. Hydration sites found with MD are represented by blue spheres. Hydration sites found with WaterKit shown as spheres colored in green (if found also in MD simulations) and red (no equivalent found in MD simulations) and represented by spheres. Spheres are labelled by their calculated enthalpy solute-water energy () in kcal/mol. The protein is shown in white with cartoons for the secondary structure and sticks for side chains and the bound ligand. Hydrogen bonds are shown as yellow dotted lines.

The analysis of hydration sites shows that water molecule positions predicted with both methods tend to closely match structural structural features of the bound ligand PU2 (Fig. 6). Hydration sites W5-W7 overlap with the positions of the atoms in the purine ring (Fig. 6B). The strongest is W5, which is stabilized by a HB interaction with Asp93 and displaced by the ligand amine group. The weakest is W7, which is displaced by the fluorine atom of PU2. WaterKit predicts a stable W6 positioned very closely (0.9 Å) to where N1 nitrogen of the ligand purine is found and displaces it upon binding (Fig. 6C). This prediction is unmatched by MD average results (Fig. 6C) because of the instability of individual MD replicates, which show a high degree of variability in oxygen density (gO: 0.1 – 39.3) and distances from the N1 nitrogen position between 0.6 and 1.6 Å. Finally, both MD and WaterKit predict a structured network of weakly bound water molecules in the hydrophobic pocket engaged by the dimethoxybenzene moiety of the ligand (Fig. 6A). An interesting finding of the hsp90α analysis is that despite the presence of numerous disordered hydroxyls in the binding site (Ser37, Tyr124, Thr169, Thr137), keeping hydrogen positions fixed during the WaterKit simulation (i.e.: when calculating grid maps) does not affect its accuracy. The use of the non-directional HB donor/acceptor probe Vina O_DA is able to compensate for this limitation (Fig. 2), so predictions can match fairly closely those obtained with MD simulations, reproducing almost entirely the water network with great accuracy.

HIV-1 protease (hivpr).

HIV-1 protease (hivpr) is a 99 amino acids viral aspartic protease that for role to cleave viral polyproteins to mature structural proteins and viral enzymes136. hivpr is a homodimeric enzyme whose active site exhibits perfect twofold symmetry in the absence of bound inhibitor or substrate137,138. The active-site region is covered by two symmetry-related hairpins (a glycine-rich loop), known as the “flaps”. It is part of substrate binding site and plays an important role in the substrate binding through a bridging water molecule, W30192. This water molecule forms two hydrogen bonds with the NH groups of Ile50 and Ile50’ in hivpr, and at the same time engages hydrogen bond acceptor groups at the P1’ and P2 sites like the carbonyls of the bound inhibitor KNI-27292. This bridging water molecule plays a critical role in the interaction between hivpr and its inhibitor and is in fact observed in nearly all hivpr complexes, except when specifically targeted for its displacement139. For example, the position of this water molecule has been exploited to design cyclic urea inhibitors able to bind by taking advantage of its displacement entropy140. The GIST analysis on hivpr showed convergence problems with the MD trajectories, requiring the MD simulations to be extended from 30 to 100 ns (Fig. S18). The difficulty reaching convergence might be responsible for the overall inferior performance of WaterKit on this system, with relatively lower agreement with MD results with respect to other systems (Fig. 4A, and Fig.S3 and S8).

A number of previous studies used different sampling protocols and methods to estimate desolvation free energy of W301 in complex with inhibitors. energies reported using MD-based methods range from −15.12 kcal/mol (Li and Lazaridis122), to −3.1 ± 0.6 and −3.2 ± 0.4 kcal/mol (Hamelberg and McCammon141; Lu et al61). In another study, Barillari et al.142 used multiple crystallographic structures to estimate energies ranging from −10 ± 0.5 to −7.1 ± 0.5 kcal/mol.

WaterKit predicted the position of W301 in the PDB structure 2zye within 0.3 Å from the crystallographic coordinates, with an estimated of −5.7 kcal/mol ( and ) (Fig.7A). Despite its well-defined receptor interaction pattern, MD simulations could not identify a well-defined hydration site, but predicted a network of multiple hydrogen bond-connected water molecules occupying positions in between the experimental coordinates of the conserved water (RMSD from W301 between 1.4 and 2.1 Å, Fig. 7B) and the atoms from the bound ligand KNI-272. We hypothesized that this result might be due to a possible bias in the crystallographic coordinates used. In absence of the inhibitor, the positions of Ile50 backbone amide nitrogens in the flaps appear to favor dynamic configurations with two water molecules interacting with each other and with each nitrogen independently. This, in turn, could lead to an unbalance between protein-water and water-water interactions, where protein-water interactions at position W301 are not strong enough to identify a stable energy minimum with a single water coordination. Such bias would be likely reinforced by the protein mobility restrains used in the MD simulations. This hypothesis was tested by repeating MD simulations using a different PDB (1hpx) bound to the same ligand (KNI-272) using an identical protocol. The new MD simulations were more successful in identifying a hydration site closer to W301 position in 2 out of 3 of the replicates, while WaterKit showed results consistent with the previous calculations (Fig. S4).

Fig. 7.

Hydration sites found around the crystallographic water W301 in hivpr (PDB: 2zye) using (A) WaterKit and (B) MD simulations (triplicates). Hydration sites found are represented by spheres colored in blue (found in MD simulation), green (found by WaterKit and present in MD simulations) and red (found by WaterKit but not present in MD simulations). Spheres are labelled by their calculated free energy () in kcal/mol. The protein is colored in white and represented in cartoon secondary structure and side-chains in sticks. The co-crystallized inhibitor KNI-272 is shown as orange sticks. Hydrogen bonds are represented by yellow dotted lines. Oxygen density (gO) map from WaterKit and MD simulation averages, contoured at 5.0 bulk density, is colored in green cyan and deep purple, respectively. (C) Network of hydration sites predicted by WaterKit within 1.5 Å from the heavy atoms of ligand KNI-272 bound in HIV-1 PR. Hydration sites found by Waterkit are represented by spheres and colored in green (if also found in MD simulations) and red (no equivalent found in MD simulations). KNI-272 ligand is shown as gray sticks. Hydration sites overlapping with key hydrogen bond features are surrounded by an additional transparent sphere.

Other stable water molecules surrounding bound ligands are considered responsible for stabilizing their binding92, either by potentially bridging ligands, or by being displaced by them. The geometric analysis of the water network reconstructed by WaterKit shows that a nearly-tetrahedral water cluster recovers the positions of the terminal methyls of the N-(ter-butyl amide group, suggesting that this group is optimally structured for their displacement. Similarly, another water cluster occupies the space engaged by the thiomethyl group of the ligand, while other more flattened clusters mimic the hydrophobic rings of the ligand. WaterKit also predicted the position of several water molecules in correspondence of key hydrogen bond acceptor and donoramide atoms on the inhibitor used to mimic the peptidic substrate of the enzyme. Of these amide water molecules, only one was detected by MD simulations.

Furthermore, both methods identified the positions of several structurally conserved water molecules in the vicinity of the ligand, such as HOH566, HOH608, HOH349, HOH422 (2zye residue numbering), which can be potentially exploited to further increase ligand affinity. Only the first two water molecules were identified by MD simulations, while WaterKit recovered all of them. Finally, both WaterKit and MD simulations identify the water molecule bound in between side chains of the catalytic Asp diad, and which is known to be actively involved in the catalytic mechanism of the enzyme143.

The data on hivpr highlights how relatively minor structural variations, such as those in the catalytic site flap region, can dramatically influence and alter water molecule positions calculated with constrained MD simulations. Conversely, the ensemble sampling used in WaterKit, appears to be less sensitive to the initial conformation used and able to systematically find the position of key structural water molecules, including the crystallographic water 301. Ultimately, while MD is capable

Fatty acid binding protein adipocyte (fabp4).

The Fatty acid binding protein adipocyte protein (fabp4) is composed of 132 amino acids arranged in 10-stranded anti-parallel -sheet forming a -barrel. Within this -barrel is a large cavity with a volume of approximately 950 Å, formed by the -barrel and two helices that are acting as a cavity “lid”144,145. Despite the hydrophobic nature of the endogenous fatty acids ligands the cavity is lined with both hydrophobic and polar amino acids. It was observed that several water molecules are conserved regardless of the presence or absence of ligand144. Those bound water molecules serve as side chain extensions for hydrophilic residues, forming a surface against which ligands are laying144. It was also hypothesizing that those internalized polar residues, and herein presence of conserved water molecules, are important to avoid the structure to collapse into an hydrophobic core, eliminating the cavity144. Visual inspection of the crystallographic structure (PDB: 2nnq) shows only two possible accesses for water molecules to exchange between the cavity and the bulk solvent (near residues Thr60 and Arg126), making fabp4 a good candidate for comparing water sampling methods in deeply buried cavity.

Results shows little to no correlation between MD simulations and WaterKit. For a more in-depth analysis and due to convergence issues, MD simulation triplicates were extended from 30 to 200 ns. While WaterKit is not dependent on the solvent accessibility of a given site, the difficulty of exchange with the bulk can have a dramatic effect on MD simulations, unless specific methods are applied to facilitate bulk/cavity exchanges47. In order to further characterize the discrepancies observed between WaterKit and the MD simulations, we analyzed the water density in fabp4 cavity. The water density was estimated based on the volume of the cavity using PyVol146 and the number of water molecules using a sphere of 8.0 Å radius centered on the ligand. The reference bulk density used was 0.0334 molecule per Å3 95. The average water density in MD simulations is about 10 % lower than the bulk density, with 0.90 ± 0.07 times the average bulk density (Fig. 8A; minimum and maximum density of 0.57 and 1.28 bulk density, respectively). WaterKit results appear to be more stable across the packing trajectory, with a calculated water density average of about 1.03 ± 0.07 bulk density, (Fig. 8B; minimum and maximum density of 0.70 and also 1.28 bulk density, respectively). The average density calculated with the MD simulations is similar to what was reported to the buried cavity of cytochromes P450, which was found to have an average density up to ≈ 20 % lower than the bulk solvent147. However, significant transient deviations from the mean can be observed during MD simulations of fabp4, in which the cavity goes through a temporary de-wetting phase (water density 40 % lower than the bulk density, around 100 ns in at least one of the triplicates) and a high-density phase (water density 1.1 times the bulk density, around 80 ns in another replicate). Previous studies showed that drying transition could naturally occur in confined regions148,149. However, due to the restraints on heavy atoms, the MD simulations show more difficulty to compensate for transient density fluctuations, and therefore reaching convergence, likely generate artifacts in the solvation energy. Conversely, the analysis suggests that WaterKit generate more consistent water configurations with reduced density fluctuations. The packing method prevents also de-wetting phenomena since water positions are sampled independently for each frame, which could also helps reaching convergence more rapidly. The difference in average density between the two methods translates approximately to 4 additional water molecules in the enclosed cavity with respect to MD results. These factors ultimately can be responsible of the reduced overall agreement with MD simulations.

Fig. 8.

Density expressed in bulk density unit in the ligand binding pocket of fabp4 (A) during MD simulations (triplicates) of 200 ns long each and (B) in the ensemble of 10,000 frames generated with WaterKit. The average density in WaterKit and MD simulations are represented by dotted red lines. The histograms represent the observed probability distribution of the density.

Neuraminidase (nram).

With the hemagglutinin, the neuraminidase dominate the surface of the influenza virus and form the main targets for neutralizing antibodies150. The functions of neuraminidase, as well as the hemagglutinin, involve interaction with the sialic acid bound to sugar residues expressed by glycoproteins or glycolipids at the cell surface150. The neuraminidase cleaves sialic acids in order to prevents virion aggregation (sialylation from cell host), and avoid the virus binding back to the dying host via the hemagglutinin receptor150. Neuraminidase assembles as a tetramer of four identical monomers. Each monomer is composed of four different structural domains: the cytoplasmic tail, transmembrane region, the stalk and finally the catalytic head, used here to assess the WaterKit protocol. A monomer is in the form of a six-bladed propeller structure, with each blade having four anti-parallel -sheet, stabilized by disulfide bridges and connected by loop of variable length. The catalytic site is present on the surface, and it is characterized by a large cavity with an unusual large number of charged residues150. The catalytic site is highly conserved with eight residues that interact directly with sialic acids (Arg118, Asp151, Arg152, Arg224, Glu276, Arg292, Arg371 and Tyr406) and with 11 other residues part of the outer shell. Mutations in the catalytic site are at the origin of the inhibitor resistance observed in some influenza strains151. For example in H1N1, the most common mutations found are E119D/G, I223R, S247G/R and H275Y. Combinations of some those mutations confer resistance against all approved neuraminidase inhibitors (Zanamivir, Oseltamivir (Tamiflu), Peramivir and Laninamivir). In the hope to find new neuraminidase inhibitors against those mutants, an accurate description of water molecules is necessary, largely due to the presence of charged residues, to properly describe protein-inhibitor interactions.

Neuraminidase is one of the systems showing also convergence issues using the MD simulations (Fig. S22), and consequently, the highest amount of deviations in both placement and ranking of water molecules when comparing the two methods. While not being the only problematic system, neuraminidase is interesting because its binding pocket is widely open with a direct access to the bulk solvent. One possible explanation could be the presence abundance of charged residues (6 Arg and 1 Lys just in the near vicinity of the ligand), which in combination with the heavy atom constraints used in the MD simulations, could be responsible of creating local energy minima hindering the sampling performance. No convergence improvement was found by running longer MD simulations (100 ns triplicates) (Fig S22). Because of these characteristics and the availability of multiple holo and apo experimentally determined structures (including mutants), this target is discussed more in detail.

Compared to other targets, WaterKit predictions for neuraminidase show a large deviation for values with respect to MD (2.78 kcal/mol, Fig. 4A, and Fig. S3 and S12), but an overall agreement between the WaterKit predictions and the MD results ( 0.68 for , and 0.73 ). This performance is likely a consequence of the instability from the lack of convergence of MD simulations. Nevertheless, the water network predicted by WaterKit shows a good agreement with several key water molecules found in apo structures (Fig. 9). Most of the predicted water molecules are found consistently across crystallographic structures and mutants (Fig. 9), and their position tend to be occupied by the atoms of the different bound ligands. To analyze the predicted water network, we isolated water molecules identified by WaterKit, as well as crystallographic water molecules from a few representative apo structures (PDB ids: 3nn9, 4nn9, 5nn9, 6nn9, 6crd, 6d3b, 6mcx), both within 1.5 Å from atoms in known binders of neuraminidase. The clusters of conserved crystallographic water molecules trace most of the essential features of sialic acid, the natural enzyme substrate (Fig. 9A). WaterKit results match these features, and extend the network to include water molecules not detected in the crystallographic structures. Two of them, located around the anomeric carbon of the ligand, match the anomeric hydroxyl (W1), and the position of the carbon itself (W2, Fig. 9 B). The position of W2 corresponds marks also the optimal placement for the electrophilic carbon of neuraminidase inhibitors designed to mimic neuraminidase-sialic acid intermediates152, and which undergo nucleophilic attack the Tyr406 152,153. Inhibitors of neuraminidase build upon the sialic acid scaffold by adding chemical moieties aimed at increasing affinity or escape resistance154,155. The analysis of WaterKit results support the hypothesis156,157 that potent and selective sialic acid analogues, such as drugs zanamivir (Relenza158,159) and oseltamivir (Tamiflu160), as well as the fluorinated derivative FeqGuDFSA154, might due their binding affinity by engaging a progressively larger number of water molecules in the predicted water network (Fig. 9 C–E), Similarly, the aromatic inhibitor BANA20688 (Fig. 9 F) was designed to establish interactions with conserved water molecules, using a cyclized amide to displace weakly bound water molecules in the vicinity of Ser102 and Glu150. The source of the convergence issues in the MD simulation was not identified. However, it is likelt that given the abundance of charged residues in this pocket, it is not unlikely that by using more accurate electrostatic models in both WaterKit and MD simulations might improve the quality of the results.

Fig. 9.

Comparison between (A) conserved crystallographic water molecules found in apo structures and (B-F) hydration sites predicted with WaterKit in the neuraminidase active site. Crystallographic water molecules are shown in red; all water molecules predicted by WaterKit are in gray, and water molecules are shown and WaterKit hydration sites are shown as red and green spheres, respectively. (A) Sialic acid bound to neuraminidase (PDB id:2bat 161) with crystallographic water molecules from apo neuraminidase structures (PDB entries 3nn9, 4nn9, 5nn9, 6nn9, 6crd, 6d3b, 6mcx) within 1.5 of ligand heavy atoms shown in in B-F. (B) Sialic acid (PDB id: 2bat) superposed to WaterKit results. (C) Oseltamivir (PDB id: 2ht7, 157). (D) Zanamivir (PDB id: 3ckz 158). (E) FeqGuDFSA (PDB id: 3w09 152). (F) BANA206 (PDB id: 1b9v 88)

Streptavidin.

Streptavidin is a bacterial protein that binds to biotin with femtomolar affinity162, among the highest known. Streptavidin is a dimer which binds one biotin molecule with each monomer, and since the availability of the first experimentally determined structures of the complex163, their interaction has been extensively investigated115–121,162. Multiple hypotheses have been made for the factors responsible for the exceptional affinity. The binding site is prevalently hydrophobic117, but the ligand establishes both van der Waals and hydrogen bond interactions117,121. Since the cumulative effect of these direct interactions is not sufficient to account for the measured affinity, cooperative hydrogen bonds and multiple hydration shells have been considered117,162. MD simulations identified a conserved pattern of water molecules in the ligand binding site31, forming a five-membered ring-like structure which occupies the position of of the bound ligand bi-cyclic core. Multiple studies5,31 suggested that those hydration sites are geometrically restricted, leading to unfavorable translational and orientational entropy. Consequently, their displacement is expected to play an important role in biotin binding. These characteristics make this the streptavidin-biotin system an interesting target for testing the performance of WaterKit.

Beside interactions with themselves, water molecules composing the ring are stabilized by a precise network of hydrogen bonds with polar side chains of Thr78, Asp116, Asn11, Ser15 and Ser33 surrounding the ring and nearly coplanar with it. Above and below the ring, the highly structured water cluster is capped by hydrophobic side chains of Trp96 and Leu13 (below the plane) and Leu25, Val47, Trp108, and Leu110 around and above the ring. The analysis of hydration sites predicted with the MD simulations and WaterKit (Fig. 10) shows that the five-membered structure is apparent in the oxygen densities calculated with both methods, but WaterKit is not able to correctly place two of them (W2 and W5) within 1 Å from the MD positions. For W2, WaterKit predicts two distinct hydration sites at 1.3 and 1.5 Å from the MD position, placing them at the edges of the MD-predicted oxygen high density location (gO map, Fig. 10 A), with the closest water overlapping with it. Hydration site W1 matches very closely two water molecules found in a recent high-resolution apo structure of streptavidin (Fig. 10 B). For W5, on the other hand, both MD and WaterKit show a more marked density smear, resulting in WaterKit placing the water at 1.5 Å from the MD position.

Fig. 10.

Hydration sites found (A) forming a five-membered ring-like structure in the streptavidin ligand binding site and (B) overlapping with biotin in the ligand binding site using MD simulations (triplicates) and WaterKit (WK). Hydration sites found in MD simulation are represented by blue spheres. Hydration sites found with WaterKit are colored in green (found an equivalent in MD simulations) and red (no equivalent found in MD simulations) and represented by spheres. The spheres are labelled by their enthalpy solute-water energy () in kcal/mol. Crystallographic water molecules found in apo structures of the streptavidin (pdb ids: 7knk, 7ek8 and 7ek9) are represented by crosses colored in red. The protein is colored in white and represented in cartoon with side-chains in sticks. The oxygen density (gO) map from WaterKit and MD simulations, contoured at 5.0 bulk density, is colored in green cyan and deep purple, respectively. The gO map for MD simulations was obtained by average the gO map from each MD replicates. Hydrogen bonds between hydration sites in MD are represented by yellow dotted lines.

Other weakly connected water molecules are predicted by both methods overlapping with the aliphatic tail of the biotin pentanoic acid, loosely matching water molecules found in various apo structures of streptavidin (Fig. 10 B). Finally, both methods predict hydration sites, WA and WB, located at the positions occupied by the carboxylic oxygen atoms of the acid, and which are visible in these apo structures, but are displaced upon ligand binding (Fig. 10 B).

While a certain degree of variability is found between WaterKit and MD predictions (especially on more unstable water positions), both methods capture the overall features of the site, including the key five-membered ring hydration site.

Conclusions

Water molecules play a key role in mediating and modulating the interactions occurring in biological environments, with important implications for drug design. Being able to capture their organization at the surfaces of biologically relevant sites is therefore essential to capture the forces behind binding events.

The WaterKit protocol discussed here represents a proof of principle to assess if an incremental MC-based simulation can efficiently approximate the calculation of water thermodynamic properties otherwise accessible only through more expensive MD calculations. In a purely MC-based simulation, water molecules make only small incremental movements, thus taking longer time to converge. In contrast, the WaterKit protocol consists of a repeated stochastic iterative placement and refinement of discrete water molecules on suitable locations on the target structure, and built layer by layer. The hypothesis is that by building progressive hydration shell layers and by repeatedly starting over the placement, it is possible describe plausible water networks on protein surfaces, and calculate their individual thermodynamic components with acceptable accuracy more rapidly using the GIST method. For that, conventional MD simulations and WaterKit were compared.

The results show that the approach of repeatedly building progressive water layers is effective at describing correct water networks, matching both MD results and experimental data. Interestingly, this confirms that by identifying the position of water molecules optimally interacting with the protein, it is possible to infer also the position of more weakly bound water molecules, which positions are influenced by them in a cascade effect.

The analysis of individual systems provided interesting insight for the interpretation of the results and their possible use for drug discovery and design. Therefore, the availability of a rapid analysis method such as the WaterKit protocol can have a beneficial impact in the wide adoption of GIST-based methods for the routine analysis of biologically and therapeutically relevant targets. For some systems studied here, WaterKit tends to identify more easily well-defined locations for water molecules compared to MD simulations. Uncertainty and divergence appear to be related to less favorable values associated with water molecules lacking a stable and well-defined position. Observations of this nature are particularly important in the context of docking applications, having a way to assess results confidence is a crucial factor. In the retrospective analysis, WaterKit appears to be also effective at capturing some of the features of known ligands biding in the sites considered (Fig. 10, 5,6). The water positions predicted by WaterKit recapitulate key ligand pharmacophoric features of well-characterized targets, such as HSP-90 (6), HIV-1 protease (Fig. 7), influenza neuraminidase (Fig. 9), and streptavidin (Fig.10).

Trajectories generated with WaterKit can therefore be used to replace MD simulations, presenting a number of advantages. It requires minimal user input, such as the target structure and the location and size of the region to analyze, which unlike MD simulations, can include only a subset of the protein volume. WaterKit seems to be less sensitive than MD simulations to the initial conformation of the target. While target atoms are constrained with both methods, the iterative placement and the ensemble sampling used in WaterKit appears to make it less sensitive to the initial conformation (see HIV-1 protease case study). Also, due to the method in which water positions is sampled, WaterKit is intrinsically less sensitive to aberrations resulting from trapped water molecules, i.e.: water molecules confined in buried cavities that have difficulty equilibrating between the binding site and the bulk solvent. To address this issue with MD simulations, dedicated approaches have been devised to facilitate this exchange47–49,164–166, but there are a number of resulting challenges, from the varying number of water molecules during the simulation, to computational inefficiencies. Equilibration issues might be source of some of the discrepancies we reported in some of the systems (neuraminidase, HIV-1 protease and FABP4).