Abstract

PURPOSE

Providers treating adults with advanced cancer increasingly seek to engage patients and surrogates in advance care planning (ACP) and end-of-life (EOL) decision making; however, anxiety and depression may interfere with engagement. The intersection of these two key phenomena is examined among patients with metastatic cancer and their surrogates: the need to prepare for and engage in ACP and EOL decision making and the high prevalence of anxiety and depression.

METHODS

Using a critical review framework, we examine the specific ways that anxiety and depression are likely to affect both ACP and EOL decision making.

RESULTS

The review indicates that depression is associated with reduced compliance with treatment recommendations, and high anxiety may result in avoidance of difficult discussions involved in ACP and EOL decision making. Depression and anxiety are associated with increased decisional regret in the context of cancer treatment decision making, as well as a preference for passive (not active) decision making in an intensive care unit setting. Anxiety about death in patients with advanced cancer is associated with lower rates of completion of an advance directive or discussion of EOL wishes with the oncologist. Patients with advanced cancer and elevated anxiety report higher discordance between wanted versus received life-sustaining treatments, less trust in their physicians, and less comprehension of the information communicated by their physicians.

CONCLUSION

Anxiety and depression are commonly elevated among adults with advanced cancer and health care surrogates, and can result in less engagement and satisfaction with ACP, cancer treatment, and EOL decisions. We offer practical strategies and sample scripts for oncology care providers to use to reduce the effects of anxiety and depression in these contexts.

A critical review finds that anxiety and depression have multiple negative effects on advance care planning (ACP) and end-of-life decision making by patients with cancer and their caregiver surrogates. The review leverages the evidence base on anxiety, depression, and their treatment to offer recommendations to cancer care providers for how to reduce the negative effects of anxiety and depression in ACP and end-of-life contexts.

INTRODUCTION

Anxiety and depression, which are the most common mental health symptoms and disorders worldwide,1,2 are highly prevalent among patients with cancer,3,4 including about one in three adults with metastatic cancer5-11 and their caregivers.6,12 One of the leading causes of death worldwide,13,14 metastatic cancer is associated with multiple experiences (difficult symptoms, treatments, and losses; threatened sources of identity and meaning15,16; and fear of dying5) that contribute to or co-occur with anxiety and depression.17-19 Anxiety and depression can also have a negative impact on advance care planning (ACP) and end-of-life (EOL) decision making—both of which are critical to the care of patients with metastatic cancer and typically involve patients and/or caregivers who serve as health care surrogates.

ACP refers to a process that supports adults in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care,20 and specifically facilitates their ability to discuss their goals and preferences with loved ones and health care providers, and to review and document their preferences, if appropriate, in the form of advance directives.21 EOL decision making is the process in which individuals and families make decisions about the care they will receive before death22 in collaboration with their health care team, sometimes significantly ahead of time during the ACP process, and often in the moment, when an urgent decision is necessary. Such decisions can include symptom management, suspension or continuation of treatments, and feeding and hydration procedures.23,24

In studies of patients with advanced cancer and/or critical illness and their health care surrogates, ACP and EOL decision making and communication interventions have often failed to affect meaningful outcomes such as goal-concordant care, length of intensive care unit (ICU) stays, resource use, or surrogate's satisfaction with patient care or mental health outcomes.25-30 Emerging research that more directly investigates the effects of anxiety and depressive symptoms and disorders on ACP and EOL decision making has the potential to inform more impactful interventions and help oncology providers to navigate the complex intersection of mental health and cancer care decision making.

A systematic review31 shows that about one in three patients with metastatic cancer experience clinically significant anxiety and depression symptoms, with anxiety symptoms in particular remaining high at EOL. Cancer caregivers report even higher rates, with nearly half reporting clinically significant anxiety or depression symptoms.19,32 Finally, death anxiety,33 the worry and apprehension generated by death awareness, is common in metastatic cancer,34,35 and is strongly linked to higher anxiety and depression symptoms among patients.36-38

Using a critical review framework to synthesize diverse findings across numerous literatures,39 the present goal is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the impacts of anxiety and depression on ACP and EOL decisions. We conducted a critical review rather than a meta-analysis or systematic review because a critical review involves integrating across literatures with an emphasis on conceptual synthesis and innovation. In addition, the modest empirical literature on anxiety and depression within ACP and EOL cancer care decision making is not yet large enough for a meta-analysis or systematic review. As the current topic is relatively new, it required synthesizing across multiple empirical literatures, including the sizable literature on the influence of anxiety and depression in decision making broadly with the more modest literature on their role in decision making in metastatic cancer specifically—an approach best reflected in a critical review. We predicted that both anxiety and depression among patients with metastatic cancer and their surrogates would have negative impacts on ACP and EOL decision making. On the basis of the review findings and informed by empirically supported behavioral interventions for anxiety and depression,40-44 in the discussion, we offer provider-friendly recommendations and sample scripts for reducing the negative effects of anxiety and depression on ACP and EOL decision making among individuals with late-stage cancer and their health care surrogates.

METHODS

Literature Search

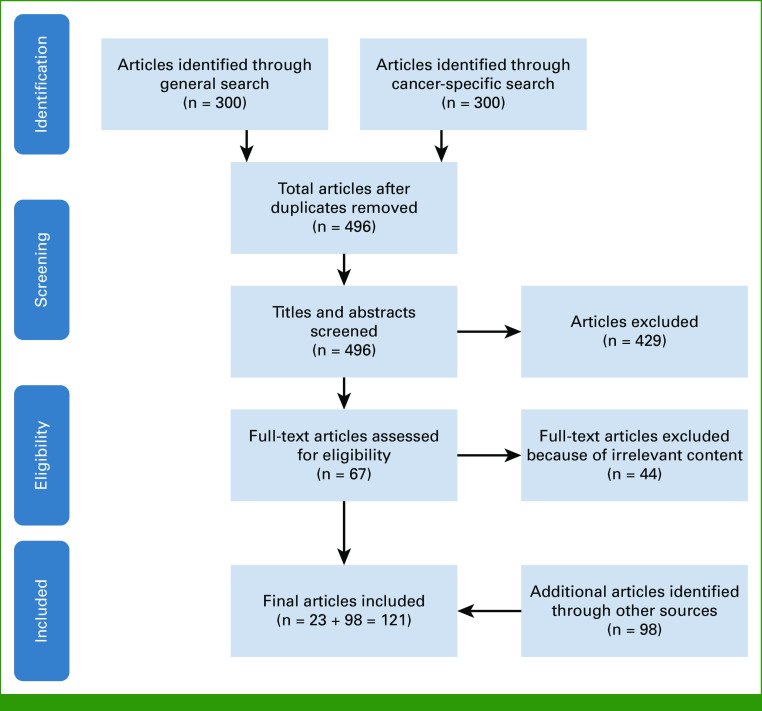

We used a critical review framework39 to identify the most significant literature in the field. In October 2022, we searched three databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. These databases were selected after consulting with a research librarian specializing in reviews, on the basis that they covered oncology (PubMed, Web of Science), psycho-oncology (all), and anxiety and depression (all, especially PsycINFO), providing good coverage and breadth for the relevant literatures. The Data Supplement (online only) details the terms and criteria of the search, with article flow summarized in Figure 1. Search terms were generated in consultation with the research librarian and articles were not restricted by year. We conducted two separate searches in each of three databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science) and pulled the first 100 articles that were listed in order of relevance in the output for each search, yielding 600 total papers (300 per search; 496 total unique records after removing duplicates; Fig 1). The first search targeted conceptual or review articles on decision making in the context of anxiety or depression; only English-language, peer-reviewed, topically relevant reviews, meta-analyses, and conceptual syntheses/models were selected for inclusion. The second search targeted health care and ACP decision making in the context of cancer and anxiety or depression; only English-language, peer-reviewed empirical studies were considered. The title and abstract of each article were reviewed for relevance by L.B.F., J.J.A., and E.E.B. on the basis of the aims of the critical review. Additional references were identified by hand-searching the bibliographies of relevant articles.

FIG 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of database search.

Synthesizing and Building on the Findings

The Results section is organized into the three empirical foci that the search strategies identified: Empirically based reviews and models of the influence of anxiety and depression on broad decision making; the role of anxiety and depression in health behavior adherence (as ACP can be conceptualized as a series of health behaviors45-47); and most specifically, their role in ACP and EOL decision making in care for patients with metastatic cancer. Following critical review recommendations,39 the most methodologically rigorous and evidence-based review and conceptual papers in the first two literatures were leveraged to inform a more comprehensive understanding of the potential negative impacts of anxiety and depression on ACP and EOL decision making in metastatic cancer, as empirical research on the latter remains comparatively modest. Analysis of the literature was conducted by a multidisciplinary team with many decades of relevant research and clinical experience across academic and community care settings, with principal analysis led by J.J.A. (clinical psychologist) and secondarily by E.E.B. (health psychologist), in close consultation with D.J.A. (medical oncologist), J.S.K. (palliative care physician), R.M.F. (palliative care nurse), and J.L.M. (oncology social worker).

RESULTS

Anxiety and Depression in the Context of Broader Decision Making

Affect and Decision Making

Decades of research48-53 show that affect—particularly in the form of immediate gut feelings experienced at the moment of decision making51 and quick judgments of good/bad or gain/loss,50 which can occur unconsciously53—serves as a foundation for decision making. Anxiety and depression, however, introduce affective and cognitive biases that can negatively affect such decisions.54

Anxiety-Related Biases

Anxious states, traits, and related disorders entail two principal information-processing biases55 that function to avoid threat: (1) a bias toward threat-related information56 (avoiding it at low levels of threat and hyperattending to it at moderate to high levels of threat57) and (2) a tendency to interpret ambiguous or uncertain situations negatively.56,57 Thus, anxiety heightens attention to negative information, increases the likelihood that uncertain options will be viewed negatively, heightens reactivity to uncertainty, and intensifies the motivation to avoid potential negative outcomes (even low-probability negative outcomes),56,58,59 often at the cost of missing potential benefits. Anxiety also leads people to inflate the likelihood of poor outcomes and to catastrophize the consequences of these outcomes if they occur.56,60-62 Furthermore, highly anxious patients typically seek more reassurance63 and greater intensity/frequency of health care visits64 than less anxious patients. To the extent that ACP and EOL decision making focus on an uncertain future, engaging in these processes may be particularly anxiety-provoking for patients and surrogates who are already anxious, and require more provider time, discussion, and deliberation.

Depression-Related Biases

Depression decreases action toward seeking benefits or rewards.60,65 A large body of evidence indicates that people who have depression or are in depressed states underestimate the value of rewarding outcomes (eg, patients with metastatic cancer may undervalue the physical relief from palliative radiation and thus choose not to pursue it), their ability to influence or control outcomes (“no matter what I do, my disease course won't improve”), and the likelihood of rewarding outcomes occurring (“the treatment may work for others, but it won't work for me”).60,66 Depressed patients may also overestimate the effort required to take action (“this treatment seems impossible to do”). These biases result in low motivation to invest attention or energy to addressing challenges,60 particularly when potential rewards or benefits require effort67 or can be realized only in the future, not immediately,68 as typically is the case with cancer treatment and ACP. Given that depressed patients tend to view rewarding future outcomes as weak, unlikely, and difficult to pursue,60,66,69 inaction often follows.

Attention, Memory, and Processing Information

Anxiety- and depression-related biases are driven by numerous neural mechanisms including poor attentional control and selective attention,70-73 working memory,72-74 and executive functioning72,73,75,76 (the ability to monitor and maintain goals, plans, and other task-relevant information77). Together, these functional challenges make it more difficult for patients and surrogates to focus and recall information in a balanced manner (eg, balanced recalling of risks and benefits), engage in complex tasks (eg, thinking through the relevant dimensions of ACP), and maintain focus on the goals and decisions at hand (eg, weighing different EOL care options to arrive at a care decision).

The Impact of Anxiety and Depression on Health Behavior Adherence

ACP as a Health Behavior

ACP involves a nuanced and progressive series of health behaviors,45-47 and thus is linked to the vast literature on health behavior adherence.45-47 Health behaviors (actions and routines that target well-being through health maintenance, restoration, and improvement) that are part of the ACP process reflect the need for patients and caregivers/surrogates to engage in a series of conversations and documentations that clarify the patient's health care and EOL-related values and preferences.78 These conversations can involve caregiver values and preferences too.78 Common ACP behaviors include learning about EOL care options; clarifying patient and caregiver surrogate values regarding quality of life and EOL care; appointing, documenting, and communicating with a health care surrogate; discussing with the health care team the patient's preferences and the appointment of the surrogate; documenting health care preferences if appropriate; and updating these conversations and documents as health and personal circumstances change. Although studies have not yet evaluated the direct effects of anxiety and depression on adherence to ACP or engagement in EOL decision making, the broader literature showcases how anxiety and depression affect adherence to other health behaviors in ways that have implications for ACP and EOL decision making.

Anxiety and Health Behavior

Anxiety has a bimodal relationship with health behavior adherence, such that very low and high levels of anxiety interfere with engagement in health behaviors, but moderate levels of anxiety often facilitate engagement.79,80 In addition, certain symptoms of anxiety, such as avoidance, make engagement in health behaviors difficult, whereas other symptoms, such as increased vigilance, can increase engagement in health behaviors, reflecting the finding that anxiety can motivate action to prevent future threat or harm,81 including in health domains.82,83 Given this variation, it is not surprising that studies of the relationship between anxiety and engagement in health behaviors have been mixed.84 For example, studies of the association between anxiety and likelihood of engaging in breast cancer screenings (mammography) have shown both positive85-87 and negative relationships.88,89 Furthermore, a more limited body of research has found support for a curvilinear relationship between anxiety and mammography such that moderate levels of anxiety are associated with keeping scheduled mammogram appointments but low and high levels of anxiety are not.90,91 Finally, among colorectal cancer survivors, greater worry and anxiety were associated with intentions to make healthy behavior changes.92 These findings suggest that moderate levels of worry and anxiety may promote engagement in ACP and EOL decision making while lower and higher levels may interfere.

Depression and Health Behavior

Symptoms of depression, such as reduced energy and hopelessness, hinder patient engagement in health behaviors.84,93 Patients with depression have more difficulty communicating with their medical team and understanding their care plans,94 which present potential barriers to ACP and EOL decision making.95 Furthermore, depression symptoms and disorders are associated with noncompliance to medical treatment.84 In a meta-analysis of 31 studies, depressed patients had 1.76 times greater estimated odds of being nonadherent to medication than nondepressed patients.93 Among adults with cancer, depression is negatively associated with adherence to anticancer medication,96 and engagement in cancer-preventing health behaviors such as exercise97,98 and smoking cessation.99,100 Given the active steps that ACP and EOL decision making entails, findings indicate that an elevation of depression symptoms would likely reduce engagement in ACP and EOL decision making.

The Role of Anxiety and Depression in EOL and Cancer-Related Decision Making

An emerging group of studies evaluate the impact of anxiety and depression on decision making related to EOL and to cancer treatment generally. Because no meta-analyses or reviews have yet summarized this modest literature, we discuss relevant individual studies.

Decisional Conflict and Regret

Patients and surrogates are often asked to make EOL decisions in highly activated emotional states, such as when they feel scared or overwhelmed.101-103 People prone to anxiety or depression may become activated more easily than others, and are likely to experience anxiety- and depression-related biases in this state. Thus, predisposition toward anxiety or depression, or emotional contexts such as at initial cancer diagnosis or EOL, can place patients and health care surrogates at particular risk for making care decisions that do not resonate once they return to less-activated emotional states. A 2015 systematic review of decisional regret in prostate cancer treatment104 identified anxiety or depression as a predictor of decisional regret. In one large study, higher trait anxiety at baseline (ie, a general tendency to be anxious) was one of the most robust predictors of decisional regret 6 months later105 (depression was not examined). A more recent large study of urology outpatients,106 including 42% with a uro-oncologic diagnosis, found that clinically elevated levels of anxiety or depression reported immediately before a urologic consult predicted greater decisional conflict immediately after the consultation (ie, feeling uncertain, unsupported, uninformed, ineffective, and unclear of values regarding a medical decision107). Finally, a systematic review of breast reconstruction after mastectomy for breast cancer108 found that higher levels of patient depression, anxiety, and distress were associated with greater decisional regret. The review included one longitudinal study showing that anxiety during treatment predicted greater decisional regret 5 years later among young breast cancer survivors.109 It also included another study of patients with early-stage breast cancer considering breast surgery, which showed that preconsult patient depression predicted subsequent decisional conflict and preconsult patient anxiety predicted subsequent lower satisfaction with the medical consult and decisional regret.110 Together, these studies suggest that in the context of cancer care, anxiety and depression increase subsequent decisional conflict and regret.

Decision-Making Roles in Intensive Care Settings (ICU)

In the context of metastatic cancer, discussions about goals of care ideally occur before hospitalization or ICU admission, when there is less urgency. Nonetheless, for many people with metastatic cancer, EOL discussions and decisions take place in the ICU. These discussions often involve family members or surrogates as patients are frequently too ill to participate. Family members and surrogates are highly prone to anxiety and depression symptoms in ICU contexts.103 A study of 50 family members of patients in the ICU, including but not limited to patients with cancer, found that elevated anxiety and depression symptoms were each strongly linked to greater preference for a passive decision-making role over an active or shared role111 (although findings were cross-sectional and could not establish causality). Importantly, passive decision making is associated with worse anxiety and depression outcomes for the family members of patients treated in the ICU,112 risking a vicious cycle.

Decision Making in Outpatient Cancer Care Settings

In a large sample of adults with advanced cancer, worrying about dying, a form of death anxiety, was associated with significantly lower likelihood of completing a living will/advance directive or discussing EOL wishes with the oncologist.113 Furthermore, anxious adults with advanced cancer were more likely to experience discordance between their preferences and their actual receipt of life-sustaining treatments,114 suggesting less communication of EOL wishes.

Communication and the Patient-Physician Relationship

Dozens of studies evaluating EOL communication interventions,30,115 most aimed at health care professionals, have identified communication as an important facet of EOL decision making.115,116 Adults with advanced cancer who met criteria for an anxiety disorder (specifically, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) had less trust in their physicians, felt less comfortable asking questions, and felt less likely to understand information that their physician communicated, and were more likely to believe their physician would offer them futile treatments and would not sufficiently control their symptoms,117 suggesting an important relationship between these anxiety disorders and difficulties in the physician-patient relationship. A longitudinal study of patients with advanced cancer showed that higher levels of patient anxiety, but not patient depression, longitudinally predicted significantly fewer patient-physician EOL care discussions,118 suggesting avoidance of such discussions. The findings suggest that anxious patients' bias for avoiding contexts perceived as threatening translates into less trust in physicians and fewer EOL care discussions. Physicians may also avoid such discussions with anxious patients, suggesting that this relationship may be bidirectional. Future studies should directly investigate this possibility.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this critical review was to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the role of anxiety and depression in ACP and EOL decision making. We predicted that both would exert negative (or largely negative) effects on decision making in these contexts, and found strong evidence in support of this prediction.

Discussion of Critical Review Findings

The review identified extensive evidence that anxiety and depression often bias and affect engagement with decision making, and a subset of studies supported this conclusion in the context of health care and specifically cancer care. As EOL decision making for patients with metastatic cancer frequently involves health care surrogates or caregivers, many current findings are relevant for both patients and surrogates. Key findings include evidence that depression reduces compliance with recommended health care treatment, reduces motivation and engagement in decision making, and is associated with surrogates adopting a more passive decision-making role in acute care settings, which further increases their depression. Depression also predicts greater decisional conflict and regret in the context of cancer treatment. The overall picture that emerges is that depression predicts lower engagement in the process of decision making followed by enduring conflict and regret.

The findings for anxiety are more nuanced in that moderate levels of anxiety can motivate adaptive responses to threat,81 including higher engagement in cancer prevention behaviors.90,91 In the context of ACP and EOL decision making, however, moderate to high anxiety is likely to create biases toward decisions or care options perceived as threatening in such a manner that promotes catastrophizing, overwhelm, strong averseness to pursuing decisions or care options that entail any risk, and avoidance of engaging in EOL decision making and ACP. Indeed, among patients with advanced cancer, higher anxiety or anxiety disorders predict lower completion of advance directives, less trust in and less comprehension of information conveyed by their physicians, and less discussion of EOL wishes. Thus unsurprisingly, anxiety among patients with advanced cancer predicts a larger gap between desired versus received life-sustaining treatments and higher decisional conflict and regret. The overall picture is that anxiety predicts negative reactivity toward anything perceived as uncertain or (at all) risky and predicts avoidance of ACP and EOL decision making, followed by enduring decisional conflict and regret. In that many decisions in metastatic cancer entail risks and uncertainty, anxious patients and surrogates are more likely to require significant oncologist time and reassurance.

Practical Recommendations for Providers

On the basis of research findings, ASCO recommends early integration of palliative care as a gold standard for patients with advanced cancer, citing benefits of improved quality of life, decreased symptom burden, reduced anxiety and depression, and goal-concordant care.119,120 Multiple authors121-124 have explored the importance of promoting health care provider education for facilitating ACP and EOL decision-making communication. Recommended strategies include establishing trust, providing respect, recognizing patient concerns, attending to patient affect, acknowledging emotions, expressing empathy, and reframing hope.121,122 Providing prompts and scripts can help to overcome barriers in having these important discussions,123,124 and represent tools and strategies that we integrate next.

Given the review findings, it may prove beneficial for cancer care providers to use brief, scalable strategies for shifting the immediate negative emotional and cognitive state of a patient or surrogate before engaging in sensitive health care discussions or decisions regarding ACP or EOL. As a recent review on anxiety and decision making concluded,55 “techniques for altering fear and anxiety may also change decisions (p. 113), with similar findings for depression.”125

In the context of care for persons with metastatic cancer, cancer care providers are aware that some degree of anxiety and depression is normal and expected and there is no correct ACP or EOL decision, with many sociocultural, familial, and spiritual factors to consider together with the prognosis, functional status, and treatment options. Given current findings, it remains important to assess the nature, severity, and source of patient or surrogate anxiety and depression symptoms at the point of decision making—a task with which supportive care providers (eg, clinical social workers, psychologists, and spiritual care providers) can assist.

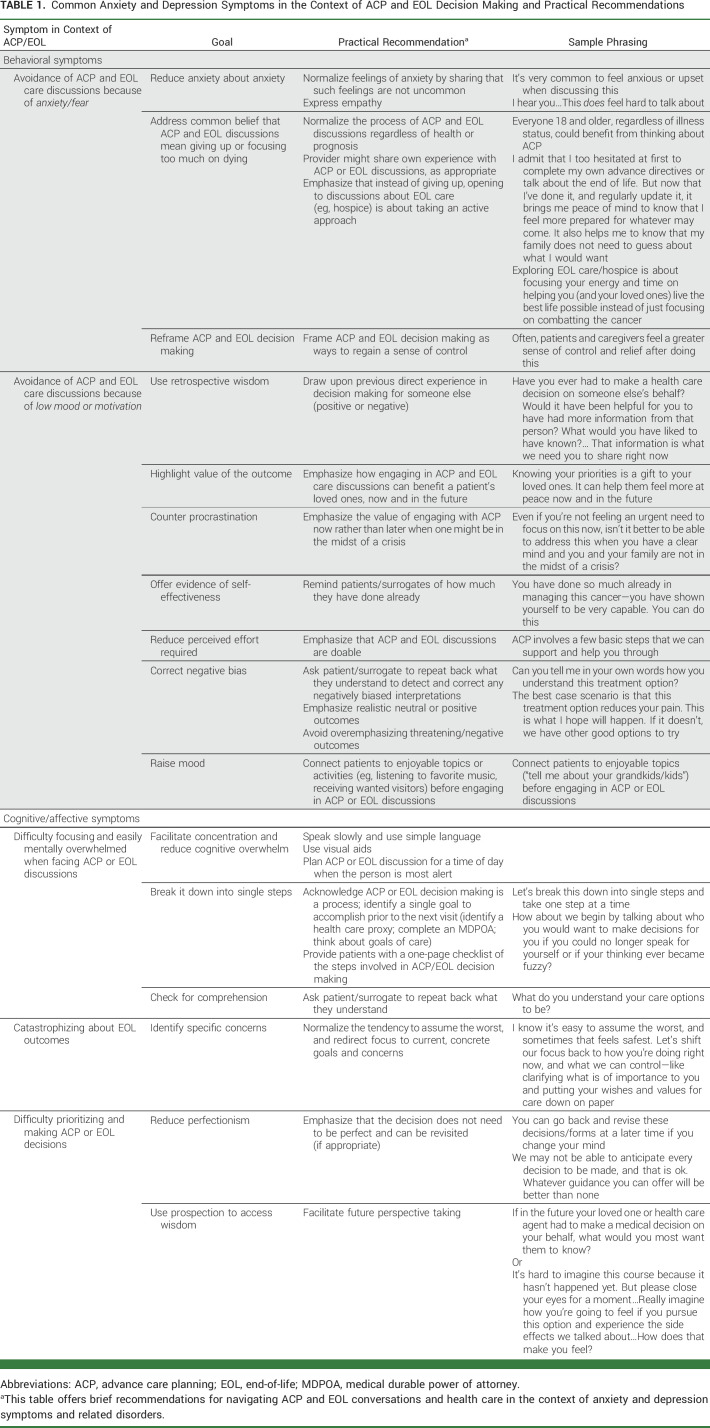

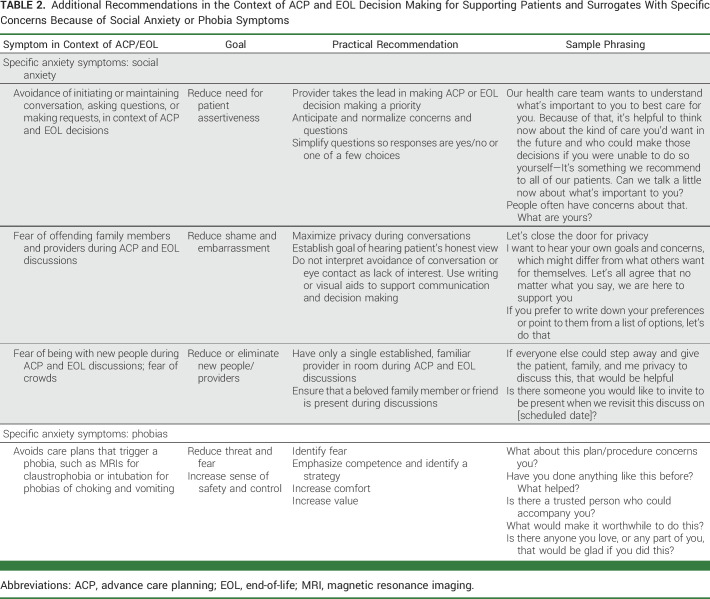

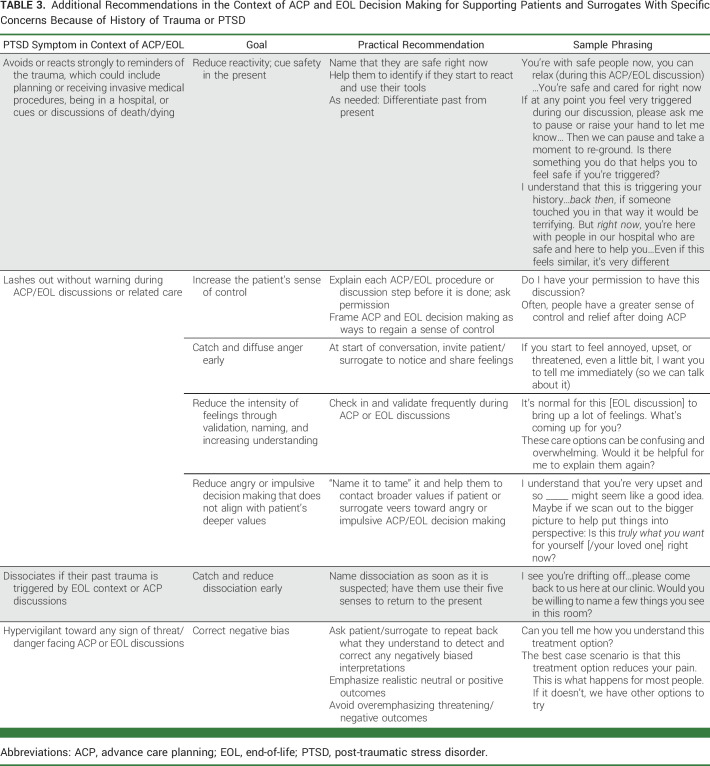

Table 1 presents common effects of anxiety and depressive symptoms relevant to ACP and EOL decision making, derived from scientific models on anxiety and depression and their influence on decision making reviewed currently.56,60,61,69,76 The table provides practical recommendations and sample scripts for how to reduce these symptoms and biases in the context of ACP and EOL decision making, on the basis of empirically supported behavioral intervention models for anxiety and depression,40-44,126 with scripts further refined by our collective clinical experience in medical oncology, palliative care medicine, palliative care nursing, clinical/health psychology, and clinical social work. These recommendations aim to help providers manage these symptoms in the moment, toward the goal of facilitating better conditions for ACP and EOL decision-making discussions. Specifically, they focus on helping anxious and depressed patients and surrogates engage more fully in ACP and EOL decision making, maintain a more balanced cognitive and emotional state, reduce or better tolerate the anxiety and overwhelm that such decision processes can trigger, clarify their values and goals, and become motivated to act on them. Table 1 emphasizes core relevant symptoms of common forms of elevated anxiety and depression. Tables 2 and 3 provide recommendations for responding to social anxiety and phobia (Table 2) and PTSD symptoms (Table 3) that are relevant for ACP and EOL decision making (PTSD was classified as an anxiety disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5), and shares many neurobiologic features and empirical treatment approaches with the anxiety disorders; thus, it is included here). These recommendations are not intended to replace established treatment approaches for anxiety or depressive symptoms or disorders. However, in the context of ACP and EOL decision making, there are at least three possible barriers to effective treatment of anxiety and depression.

In EOL contexts, patients must often make decisions in the moment on an urgent time scale, and thus there is not enough time to treat the underlying anxiety or depression.

For acutely or seriously ill patients, recommended behavioral treatments may be impractical and psychiatric medications can negatively affect the cognitive functioning127,128 and alertness129 required for ACP and EOL discussions, or interfere with anticancer medications such as tamoxifen.130

For about half of the adults (without cancer), the evidence-based pharmacologic and psychological treatments for anxiety and depression are ineffective or only partially effective.131-134

If the anxious or depressed individual is the surrogate rather than the patient, providers can offer resources, information, and support,135 but it may fall outside of their purview to suggest treatment.

TABLE 1.

Common Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in the Context of ACP and EOL Decision Making and Practical Recommendations

TABLE 2.

Additional Recommendations in the Context of ACP and EOL Decision Making for Supporting Patients and Surrogates With Specific Concerns Because of Social Anxiety or Phobia Symptoms

TABLE 3.

Additional Recommendations in the Context of ACP and EOL Decision Making for Supporting Patients and Surrogates With Specific Concerns Because of History of Trauma or PTSD

In conclusion, people with metastatic cancer and their health care surrogates commonly experience anxiety and depression, both of which are characterized by symptoms and biases that can negatively affect ACP and EOL decision-making engagement, content, and satisfaction. If providers recognize that patients or surrogates are experiencing anxiety or depression symptoms, they can use a range of brief strategies to reduce the extent and influence of these symptoms in the context of ACP and EOL decision making. Research to evaluate the effectiveness of these strategies in the context of ACP and EOL decision making, and how best to train providers in their provision, represent important next steps toward the goal of increasing patient and surrogate engagement and satisfaction with cancer care decisions.

SUPPORT

Supported by National Institutes of Health R01NR018479 to J.J.A.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Joanna J. Arch, Emma E. Bright, Regina M. Fink, Jill L. Mitchell, David J. Andorsky, Jean S. Kutner

Collection and assembly of data: Joanna J. Arch, Lauren B. Finkelstein

Data analysis and interpretation: Joanna J. Arch, Emma E. Bright, Jill L. Mitchell, David J. Andorsky, Jean S. Kutner

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Anxiety and Depression in Metastatic Cancer: A Critical Review of Negative Impacts on Advance Care Planning and End-of-Life Decision Making With Practical Recommendations

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Joanna J. Arch

Consulting or Advisory Role: AbbVie/Genentech (I), Bristol Meyers Squibb (I)

Research Funding: NCCN/AstraZeneca

Jill L. Mitchell

Employment: Rocky Mountain Cancer Centers/USON, Meru Health

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Teladoc Health stock, Walgreens Boots Alliance stock, FSPHX (ETF), XLV (etf)

Research Funding: Cancer Support Community, University of Colorado—Boulder/NIH grant funding

David J. Andorsky

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, AstraZeneca, AbbVie/Genentech, Novartis

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, AbbVie, Epizyme, Novartis

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Santomauro DF, Herrera AMM, Shadid J, et al. : Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398:1700-1712, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators : Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 9:137-150, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arch JJ, Genung SR, Ferris MC, et al. : Presence and predictors of anxiety disorder onset following cancer diagnosis among anxious cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 28:4425-4433, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, et al. : Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 14:721-732, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grossman CH, Brooker J, Michael N, et al. : Death anxiety interventions in patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review. Palliat Med 32:172-184, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart NH, Crawford-Williams F, Crichton M, et al. : Unmet supportive care needs of people with advanced cancer and their caregivers: A systematic scoping review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 176:103728, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadan-Lottick NS, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. : Psychiatric disorders and mental health service use in patients with advanced cancer: A report from the coping with cancer study. Cancer 104:2872-2881, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. : Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: A meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol 12:160-174, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miovic M, Block S: Psychiatric disorders in advanced cancer. Cancer 110:1665-1676, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vodermaier A, Linden W, MacKenzie R, et al. : Disease stage predicts post-diagnosis anxiety and depression only in some types of cancer. Br J Cancer 105:1814-1817, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker ZJ, Xue S, Jones MP, et al. : Depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders in patients with cancer in low-and lower-middle–income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JCO Glob Oncol 7:1233-1250, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang T, Molassiotis A, Chung BPM, et al. : Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: A systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 17:1-29, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, et al. : The ever‐increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer 127:3029-3030, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. : Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 136:E359-E386, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halstead MT, Hull M: Struggling with paradoxes: The process of spiritual development in women with cancer, Oncol Nurs Forum 28:1534-1544, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caldeira S, Timmins F, de Carvalho EC, et al. : Clinical validation of the nursing diagnosis spiritual distress in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Int J Nurs Knowl 28:44-52, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerrits MM, van Marwijk HW, van Oppen P, et al. : Longitudinal association between pain, and depression and anxiety over four years. J Psychosom Res 78:64-70, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown LF, Kroenke K: Cancer-related fatigue and its associations with depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Psychosomatics 50:440-447, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geng HM, Chuang DM, Yang F, et al. : Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 97:e11863, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. : Defining advance care planning for adults: A consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manag 53:821-832.e1, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rietjens JA, Sudore RL, Connolly M, et al. : Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: An international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol 18:e543-e551, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murali KP: End of life decision-making: Watson's theory of human caring. Nurs Sci Q 33:73-78, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manalo MFC: End-of-life decisions about withholding or withdrawing therapy: Medical, ethical, and religio-cultural considerations. Palliat Care 7:1-5, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albert RH: End-of-life care: Managing common symptoms. Am Fam Physician 95:356-361, 2017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bibas L, Peretz-Larochelle M, Adhikari NK, et al. : Association of surrogate decision-making interventions for critically ill adults with patient, family, and resource use outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2:e197229, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jimenez G, Tan WS, Virk AK, et al. : Overview of systematic reviews of advance care planning: Summary of evidence and global lessons. J Pain Symptom Manage 56:436-459.e25, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernacki R, Paladino J, Neville BA, et al. : Effect of the serious illness care program in outpatient oncology: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 179:751-759, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrison RS, Meier DE, Arnold RM: What's wrong with advance care planning? JAMA 326:1575-1576, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Periyakoil VS, Gunten CFV, Arnold R, et al. : Caught in a loop with advance care planning and advance directives: How to move forward? J Palliat Med 25:355-360, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selman LE, Brighton LJ, Hawkins A, et al. : The effect of communication skills training for generalist palliative care providers on patient-reported outcomes and clinician behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manag 54:404-416.e5, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, et al. : Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag 34:94-104, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bedaso A, Dejenu G, Duko B: Depression among caregivers of cancer patients: Updated systematic review and meta‐analysis. Psychooncology 31:1809-1820, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Templer DI: The construction and validation of a death anxiety scale. J Gen Psychol 82:165-177, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neel C, Lo C, Rydall A, et al. : Determinants of death anxiety in patients with advanced cancer. BMJ Support Palliat Care 5:373-380, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong Y, Yuhan L, Youhui G, et al. : Death anxiety among advanced cancer patients: A cross-sectional survey. Support Care Cancer 30:3531-3539, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menzies RE, Sharpe L, Dar‐Nimrod I: The relationship between death anxiety and severity of mental illnesses. Br J Clin Psychol 58:452-467, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonen G, Kaymak SU, Cankurtaran ES, et al. : The factors contributing to death anxiety in cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol 30:347-358, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krause S, Rydall A, Hales S, et al. : Initial validation of the Death and Dying Distress Scale for the assessment of death anxiety in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 49:126-134, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grant MJ, Booth A: A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 26:91-108, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barlow DH, Craske M: Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic. Albany, NY, Graywind Publications, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Craske MG, Barlow DH: Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic: Therapist Guide (ed 5). New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beck JS: Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York, NY, Guilford Publications, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Craske MG, Meuret AE, Ritz T, et al. : Positive affect treatment for depression and anxiety: A randomized clinical trial for a core feature of anhedonia. J Consult Clin Psychol 87:457-471, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change. New York, NY, Guilford Press, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, et al. : Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc 57:1547-1555, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ernecoff NC, Keane CR, Albert SM: Health behavior change in advance care planning: An agent-based model. BMC Public Health 16:1-9, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levoy K, Salani DA, Buck H: A systematic review and gap analysis of advance care planning intervention components and outcomes among cancer patients using the transtheoretical model of health behavior change. J Pain Symptom Manag 57:118-139.e6, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tversky A, Kahneman D: The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 211:453-458, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greifeneder R, Bless H, Pham MT: When do people rely on affective and cognitive feelings in judgment? A review. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 15:107-141, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Slovic P, Finucane M, Peters E, et al. : Rational actors or rational fools: Implications of the affect heuristic for behavioral economics. J Socio Econ 31:329-342, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Loewenstein GF, Weber EU, Hsee CK, et al. : Risk as feelings. Psychol Bull 127:267-286, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lerner JS, Keltner D: Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgement and choice. Cogn Emot 14:473-493, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winkielman P, Knutson B, Paulus M, et al. : Affective influence on judgments and decisions: Moving towards core mechanisms. Rev Gen Psychol 11:179-192, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paulus MP, Angela JY: Emotion and decision-making: Affect-driven belief systems in anxiety and depression. Trends Cogn Sci 16:476-483, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartley CA, Phelps EA: Anxiety and decision-making. Biol Psychiatry 72:113-118, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grupe DW, Nitschke JB: Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: An integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nat Rev Neurosci 14:488-501, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mathews A, MacLeod C: Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 1:167-195, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peng J, Xiao W, Yang Y, et al. : The impact of trait anxiety on self‐frame and decision making. J Behav Decis Making 27:11-19, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wake S, Wormwood J, Satpute AB: The influence of fear on risk taking: A meta-analysis. Cogn Emot 34:1143-1159, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bishop SJ, Gagne C: Anxiety, depression, and decision making: A computational perspective. Annu Rev Neurosci 41:371-388, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barlow DH: Anxiety and Its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic (ed 2). New York, NY, Guilford Press, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Craske MG, Rauch SL, Ursano R, et al. : What is an anxiety disorder? Depress Anxiety 26:1066-1085, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stark D, Kiely M, Smith A, et al. : Reassurance and the anxious cancer patient. Br J Cancer 91:893-899, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lebel S, Tomei C, Feldstain A, et al. : Does fear of cancer recurrence predict cancer survivors' health care use? Support Care Cancer 21:901-906, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Halahakoon DC, Kieslich K, O'Driscoll C, et al. : Reward-processing behavior in depressed participants relative to healthy volunteers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 77:1286-1295, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grahek I, Shenhav A, Musslick S, et al. : Motivation and cognitive control in depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 102:371-381, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Horne SJ, Topp TE, Quigley L: Depression and the willingness to expend cognitive and physical effort for rewards: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 88:102065, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amlung M, Marsden E, Holshausen K, et al. : Delay discounting as a transdiagnostic process in psychiatric disorders: A meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 76:1176-1186, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Craske MG, Meuret AE, Ritz T, et al. : Treatment for anhedonia: A neuroscience driven approach. Depress Anxiety 33:927-938, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peckham AD, McHugh RK, Otto MW: A meta‐analysis of the magnitude of biased attention in depression. Depress Anxiety 27:1135-1142, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shi R, Sharpe L, Abbott M: A meta-analysis of the relationship between anxiety and attentional control. Clin Psychol Rev 72:101754, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rock PL, Roiser J, Riedel WJ, et al. : Cognitive impairment in depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 44:2029-2040, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Langarita-Llorente R, Gracia-Garcia P: Neuropsychology of generalized anxiety disorders: A systematic review [in Spanish]. Rev Neurol 69:59-67, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moran TP: Anxiety and working memory capacity: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol Bull 142:831-864, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Snyder HR: Major depressive disorder is associated with broad impairments on neuropsychological measures of executive function: A meta-analysis and review. Psychol Bull 139:81-132, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sharp PB, Miller GA, Heller W: Transdiagnostic dimensions of anxiety: Neural mechanisms, executive functions, and new directions. Int J Psychophysiol 98:365-377, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, et al. : The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol 41:49-100, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sudore RL: Can we agree to disagree? JAMA 302:1629-1630, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lindberg NM, Wellisch D: Anxiety and compliance among women at high risk for breast cancer. Ann Behav Med 23:298-303, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Buelow JR, Zimmer AH, Mellor MJ, et al. : Mammography screening for older minority women. J Appl Gerontol 17:133-149, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miloyan B, Bulley A, Suddendorf T: Episodic foresight and anxiety: Proximate and ultimate perspectives. Br J Clin Psychol 55:4-22, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nel A, Kagee A: Common mental health problems and antiretroviral therapy adherence. AIDS Care 23:1360-1365, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weaver KE, Llabre MM, Durán RE, et al. : A stress and coping model of medication adherence and viral load in HIV-positive men and women on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Health Psychol 24:385-392, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW: Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med 160:2101-2107, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moser RP, McCaul K, Peters E, et al. : Associations of perceived risk and worry with cancer health-protective actions: Data from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J Health Psychol 12:53-65, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McCaul KD, Schroeder DM, Reid PA: Breast cancer worry and screening: Some prospective data. Health Psychol 15:430-433, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Consedine NS, Magai C, Neugut AI: The contribution of emotional characteristics to breast cancer screening among women from six ethnic groups. Prev Med 38:64-77, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schwartz MD, Taylor KL, Willard KS: Prospective association between distress and mammography utilization among women with a family history of breast cancer. J Behav Med 26:105-117, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lerman C, Daly M, Sands C, et al. : Mammography adherence and psychological distress among women at risk for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:1074-1080, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Andersen MR, Smith R, Meischke H, et al. : Breast cancer worry and mammography use by women with and without a family history in a population-based sample. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12:314-320, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Champion VL, Skinner CS, Menon U, et al. : A breast cancer fear scale: Psychometric development. J Health Psychol 9:753-762, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mullens AB, McCaul KD, Erickson SC, et al. : Coping after cancer: Risk perceptions, worry, and health behaviors among colorectal cancer survivors. Psychooncology 13:367-376, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Grenard JL, Munjas BA, Adams JL, et al. : Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 26:1175-1182, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Piette JD, Richardson C, Valenstein M: Addressing the needs of patients with multiple chronic illnesses: The case of diabetes and depression. Am J Manag Care 10:152-162, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zolnierek KBH, DiMatteo MR: Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: A meta-analysis. Med Care 47:826-834, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mausbach BT, Schwab RB, Irwin SA: Depression as a predictor of adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) in women with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 152:239-246, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Goudarzian AH, Nesami MB, Zamani F, et al. : Relationship between depression and self-care in Iranian patients with cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 18:101-106, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Gelmon K, et al. : Predictors of supervised exercise adherence during breast cancer chemotherapy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 40:1180-1187, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Guimond A-J, Croteau VA, Savard M-H, et al. : Predictors of smoking cessation and relapse in cancer patients and effect on psychological variables: An 18-month observational study. Ann Behav Med 51:117-127, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Berg CJ, Thomas AN, Mertens AC, et al. : Correlates of continued smoking versus cessation among survivors of smoking‐related cancers. Psychooncology 22:799-806, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Loewenstein G: Hot-cold empathy gaps and medical decision making. Health Psychol 24:S49-S56, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ellis EM, Barnato AE, Chapman GB, et al. : Toward a conceptual model of affective predictions in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 57:1151-1165, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, et al. : Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: Ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med 29:1893-1897, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Christie DR, Sharpley CF, Bitsika V: Why do patients regret their prostate cancer treatment? A systematic review of regret after treatment for localized prostate cancer. Psychooncology 24:1002-1011, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Berry DL, Wang Q, Halpenny B, et al. : Decision preparation, satisfaction and regret in a multi-center sample of men with newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer. Patient Educ Couns 88:262-267, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Köther AK, Alpers GW, Büdenbender B, et al. : Predicting decisional conflict: Anxiety and depression in shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns 104:1229-1236, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.O'Connor AM: User manual-decisional conflict scale. 2010. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Decisional_Conflict.pdf

- 108.Flitcroft K, Brennan M, Spillane A: Decisional regret and choice of breast reconstruction following mastectomy for breast cancer: A systematic review. Psychooncology 27:1110-1120, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fernandes‐Taylor S, Bloom JR: Post‐treatment regret among young breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 20:506-516, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lam WW, Kwok M, Chan M, et al. : Does the use of shared decision-making consultation behaviors increase treatment decision-making satisfaction among Chinese women facing decision for breast cancer surgery? Patient Educ Couns 94:243-249, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, et al. : Passive decision-making preference is associated with anxiety and depression in relatives of patients in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care 24:249-254, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fang T, Du P, Wang Y, et al. : Role mismatch in medical decision-making Participation is associated with anxiety and depression in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. J Trop Med 2022:8027422, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rodenbach RA, Althouse AD, Schenker Y, et al. : Relationships between advanced cancer patients' worry about dying and illness understanding, treatment preferences, and advance care planning. J Pain Symptom Manage 61:723-731.e1, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wen F-H, Chen J-S, Chou W-C, et al. : Extent and determinants of terminally ill cancer patients' concordance between preferred and received life-sustaining treatment states: An advance care planning randomized trial in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manage 58:1-10.e10, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Walczak A, Butow PN, Bu S, et al. : A systematic review of evidence for end-of-life communication interventions: Who do they target, how are they structured and do they work? Patient Educ Couns 99:3-16, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Back AL, Anderson WG, Bunch L, et al. : Communication about cancer near the end of life. Cancer 113:1897-1910, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Spencer R, Nilsson M, Wright A, et al. : Anxiety disorders in advanced cancer patients: Correlates and predictors of end‐of‐life outcomes. Cancer 116:1810-1819, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tang ST, Chen CH, Wen F-H, et al. : Accurate prognostic awareness facilitates, whereas better quality of life and more anxiety symptoms hinder end-of-life care discussions: A longitudinal survey study in terminally ill cancer patients' last six months of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 55:1068-1076, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. : Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 35:96-112, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Smith CB, Phillips T, Smith TJ: Using the new ASCO clinical practice guideline for palliative care concurrent with oncology care using the TEAM approach. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 37:714-723, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tulsky JA: Beyond advance directives: Importance of communication skills at the end of life. JAMA 294:359-365, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Knutzen KE, Sacks OA, Brody-Bizar OC, et al. : Actual and missed opportunities for end-of-life care discussions with oncology patients: A qualitative study. JAMA Netw Open 4:e2113193, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Anderson RJ, Bloch S, Armstrong M, et al. : Communication between healthcare professionals and relatives of patients approaching the end-of-life: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Palliat Med 33:926-941, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sagara Y, Mori M, Yamamoto S, et al. : Current status of advance care planning and end‐of‐life communication for patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist 26:e686-e693, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cooper JA, Gorlick MA, Denny T, et al. : Training attention improves decision making in individuals with elevated self-reported depressive symptoms. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 14:729-741, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Forsyth JP, Eifert GH, Barrios V: Fear conditioning in an emotion regulation context: A fresh perspective on the origins of anxiety disorders, in Craske MG, Hermans D, Vansteenwegen D (eds): From Basic Processes to Clinical Implications. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2006, pp 133-153 [Google Scholar]

- 127.Stewart SA: The effects of benzodiazepines on cognition. J Clin Psychiatry 66:9-13, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Foy A, O'Connell D, Henry D, et al. : Benzodiazepine use as a cause of cognitive impairment in elderly hospital inpatients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 50:M99-M106, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Buffett-Jerrott S, Stewart S: Cognitive and sedative effects of benzodiazepine use. Curr Pharm Des 8:45-58, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kelly CM, Juurlink DN, Gomes T, et al. : Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and breast cancer mortality in women receiving tamoxifen: A population based cohort study. BMJ 340:c693, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Loerinc AG, Meuret AE, Twohig MP, et al. : Response rates for CBT for anxiety disorders: Need for standardized criteria. Clin Psychol Rev 42:72-82, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Arroll B, Macgillivray S, Ogston S, et al. : Efficacy and tolerability of tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs compared with placebo for treatment of depression in primary care: A meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med 3:449-456, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Johnsen TJ, Friborg O: The effects of cognitive behavioral therapy as an anti-depressive treatment is falling: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 141:747-768, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, et al. : Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: A meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med 5:e45, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Molassiotis A, Wang M: Understanding and supporting informal cancer caregivers. Curr Treat Options Oncol 23:494-513, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]