ABSTRACT

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a syndrome of isolated elevated intracranial pressure of unknown aetiology. The IIH spectrum has evolved over the past decade making the diagnosis and management more challenging. The neurological examination in IIH is typically normal except for papilloedema and possible cranial nerve 6 palsy. Recent publications have highlighted skull base thinning and remodelling in patients with chronic IIH. Resulting skull base defects can cause meningo-encephalocoeles, which are potential epileptogenic foci. We describe the clinical and radiological characteristics of five IIH patients with seizures and meningo-encephalocoeles as the presenting manifestations of IIH spectrum disorder.

KEYWORDS: Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, seizures, meningocele, encephalocele, meningoencephalocele

Introduction

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a syndrome of isolated elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) of unknown cause.1 The neurological examination in IIH is typically normal except for papilloedema and possible cranial nerve 6 palsy, although rare atypical symptoms and signs can occur.2 With the rising incidence of obesity worldwide and the corresponding increasing number of cases of IIH,3,4 the spectrum of IIH has evolved over the past decade to include isolated radiological changes secondary to chronically elevated ICP and spontaneous skull base cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks.5,6 Bony remodelling of the skull base is common in IIH and may result in encephalocoeles and meningo-encephalocoeles,7 which likely underly skull base CSF leaks.5,6 Recent reports have suggested an association between IIH and seizures, presumably secondary to skull base meningo-encephalocoeles, especially those with temporal lobe herniation (Table 1).8–17

Table 1.

Reported patients with seizures and radiological findings of idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

| Study | Number | Temporal lobe encephalocoele | Temporal lobe epilepsy | Gender | Age/age range | BMI (kg/m2) range | IIH symptoms* | Papilloedema | LP opening pressure (cm water) | Radiological findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McCorquodale et al.8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 F | 63 | NA | Chronic headaches | NR | 32 | Temporal lobe encephalocele; empty sella turcica; flat globes; tortuosity of optic nerves; TSS |

| Urbach et al.9 | 22 | 20 | 22 | 9 F 13 M |

12–59 | 19–36 | None | NR | NR | 20 temporal lobe encephalocoele; 10 empty sella turcica; 11 flat globes; 10 optic nerve sheath dilatation, 12 TSS |

| Campbell et al.10 | 418 | 52 | 46 | 43 F 9 M |

12–43 | Mean 37 | NR | Yes (6) | NR | 52 temporal lobe encephalocoele; 48 empty sella turcica; 5 enlarged Meckel’s cave |

| Sandhu et al.11 | 474 | 25 | 10 | 6 F 4 M |

23–64 | Mean 31 ± 8 | Headaches (3) | No | LP done in 6 (2 with OP > 25) | 25 temporal lobe encephalocoele; 4 empty sella turcica; 4 optic nerve sheath dilatation |

| Martinez-Poles et al.12 | 58 | 29 | 29 | 16 F 13 M |

13–48 | Mean 26 | None | No | NR | 29 temporal lobe encephalocoele; 26 empty sella turcica; 42 optic nerve sheath dilatation |

| Urbach et al.13 | 15 | 15 | 6 | 6 F 9 M |

16–55 | 21–42 | None | NR | NR | 15 temporal lobe encephalocoele; 6 empty or partially empty sella turcica; 5 optic nerve sheath dilatation, 3 vertical tortuosity of optic nerves; 4 enlarged Meckel’s cave; 6 TSS |

| Sayal et al. 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 M | 38 | 36 | Headaches, tinnitus | Yes (1) | 48 | Temporal lobe encephalocoele with gliosis and brain parenchyma herniating into left foramen ovale; empty sella turcica; flat globes; tortuosity of optic nerves; TSS |

| Graese et al.15 | 474 | 103 | 103 | 80 F 23 M |

14–44 | NR | Headaches (17) | NR | >25 (12) | 103 temporal encephalocoele |

| Kamali et al.16 | 40 | 6 | 9 | 20 F 20 M |

1–16 | NR | NR | NR | >25 | 6 temporal lobe encephalocoele |

| Samudra et al.17 | 46 | 37 | 21 | 31 F 6 M |

Mean 32 | Mean 32 | Headaches (2) | NR | 33 (1) | 37 anterior temporal encephalocoele; 7 empty sella turcica |

*None of the patients apart from 4 patients in Samudra et al.17 had a previous diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

BMI = body mass index; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; F = female; IIH = idiopathic intracranial hypertension; LP = lumbar puncture; M = male; NR = not reported; TSS = transverse sinus stenosis.

We present five patients with new-onset seizures from meningo-encephalooceles, most likely related to chronically elevated ICP from IIH spectrum disorder.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all adult patients with definite IIH according to the modified Dandy criteria1 seen in our neuro-ophthalmology service from 2015 to 2022 to identify those with a history of seizures. We also searched all patients seen in our service with a diagnosis of seizures over the same time period. We identified five patients with seizures related to frontal or temporal lobe encephalocoeles revealing IIH spectrum disorder. This study was approved by our institutional review board.

We performed a detailed review of the literature by searching PubMed for articles in English between 1 January 1992 and 1 December 2022 using the following key words: idiopathic intracranial hypertension; pseudotumour cerebri; skull base defect; meningo-encephalocoele; meningocoele; encephaloocele; epilepsy; seizure; and CSF leak.

Case descriptions

Patient 1

A 79-year-old non-obese White woman with a body mass index (BMI) of 25.2 kg/m2, a history of hypertension and a 2-year history of recurrent episodes of transient loss of consciousness without warning symptoms or postictal confusion, was brought to the emergency department (ED) in status epilepticus. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed multiple dural osseous defects in the middle fossa with an encephalocoele in the left anterior temporal lobe and a meningocoele in the right sphenoid sinus. Other MRI findings included an empty sella turcica, optic nerve tortuosity, dilated optic nerve sheaths, posterior globe flattening, and bilateral transverse venous sinus stenoses, suggesting chronically elevated ICP (Figure 1). A scalp electroencephalogram (EEG) showed signs of bitemporal dysfunction with occasional independent focal polymorphic nonrhythmic delta waves with no epileptiform activity or seizures. She was started on levetiracetam. She reported chronic headaches but no visual symptoms or tinnitus. She had never had significant weight gain and had never used vitamin A derivatives or tetracyclines. Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) and angiography (MRA) ruled out a dural arteriovenous fistula. Neuro-ophthalmological examination showed normal afferent visual function, including full Humphrey visual fields (HVF). Ocular funduscopic examination and optical coherence tomography (OCT) did not show papilloedema, but revealed peripapillary changes suggesting prior optic disc oedema in both eyes. She reported that she had had rhinorrhoea with clear fluid from her right nostril that had started about the same time as her episodes of loss of consciousness, consistent with a spontaneous skull base CSF leak. A lumbar puncture (LP), prior to CSF leak repair, showed an opening pressure of 26 cm of water with normal CSF contents. She underwent endonasal sphenoid dural repair and was started on acetazolamide. Her headaches and rhinorrhoea resolved and she remained seizure-free.

Figure 1.

Brain imaging from patient 1. Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (a) and coronal T1-weighted MRI with contrast (b) showing a temporal encephalocoele (arrows). Head computed tomography scan without contrast (c) showing a meningocoele erupting into the sphenoid sinus (arrow) through an osseous defect in the posterior wall of the sphenoidal sinus (arrowhead). The meningocoele is better seen on T1-weighted with contrast MRI (d). Sagittal T1-weighted MRI with contrast showing an empty sella turcica (e, arrow). Axial T2-weighted MRI showing optic nerve tortuosity with slightly dilated optic nerve sheaths (f, arrows).

Patient 2

A 34-year-old obese Black woman with a BMI of 45.8 kg/m2 was brought to the ED after an episode of loss of consciousness. She had had a 3-year history of recurrent focal and generalised seizures that had been poorly controlled with medical treatment. A computed tomography (CT) scan of her head showed anterior skull base defects with a left frontal encephalocoele extending into the frontal sinus. MRI of her brain confirmed the left frontal encephalocoele and showed an empty sella turcica, dilated optic nerve sheaths and bilateral transverse venous sinus stenoses, suggesting chronically elevated ICP. She was diagnosed with non-convulsive generalised seizures and was started on levetiracetam. She reported that she had had headaches and clear rhinorrhoea for the previous year. Neuro-ophthalmological examination showed normal afferent visual function including full HVFs and mild bilateral optic disc oedema suggesting papilloedema from elevated ICP. She underwent endoscopic repair of the frontal encephalocoele and CSF leak repair, and was then started on acetazolamide. Her headaches and rhinorrhoea resolved, but mild papilloedema was still present 4 months after initiation of treatment. An LP at that time showed an opening pressure of 27 cm of water with normal CSF contents. She later underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, and the papilloedema resolved with weight loss and continued treatment with acetazolamide. She remained seizure-free.

Patient 3

A 34-year-old obese Black woman with a BMI of 45.5 kg/m2 and a history of migraine headaches had a 2-year history of focal to bilateral generalised tonic-clonic seizures treated with zonisamide and lacosamide. Long-term video-EEG showed right temporal electrical seizures and left temporal electroclinical seizures. MRI demonstrated an encephalocoele along the floor of the left middle cranial fossa anterior to the foramen ovale, an empty sella turcica, optic nerve tortuosity and bilateral transverse venous sinus stenoses. She reported intermittent headaches and pulsatile tinnitus, but denied visual symptoms. Neuro-ophthalmological examination showed normal afferent visual function with full HVFs, and bilateral mild optic atrophy with peripapillary changes, suggesting prior optic disc oedema (Figure 2). The LP opening pressure was 28 cm of water with normal CSF contents. She was subsequently lost to follow-up.

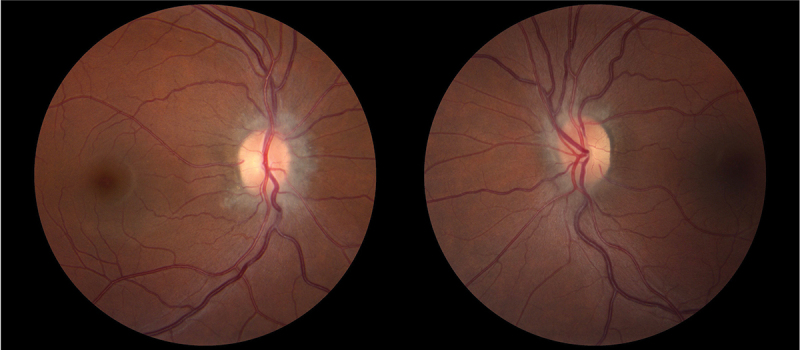

Figure 2.

Fundus photography of patient 3 showing temporal pallor and peripapillary changes in both eyes (left: right eye; right: left eye).

Patient 4

A 43-year-old obese White man with a BMI of 51.7 kg/m2 and a history of hypertension developed focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures with postictal aggressivityand focal non-motor seizures with behaviour arrest. A sinus CT scan and MRI of his face showed focal osseous dehiscence in the anterior skull base with a meningo-encephalocoele protruding into the right frontal sinus and small excavating meningocoeles along the olfactory recesses. The MRI also showed dilated optic nerve sheaths, posterior scleral flattening, and a partially empty sella turcica. He reported headaches and right-sided rhinorrhoea consistent with a spontaneous skull base CSF leak that had begun about 6 months after the onset of seizures. He denied visual symptoms or pulsatile tinnitus. Neuro-ophthalmological examination showed normal afferent visual function including full HVFs. There was no papilloedema, but he had elevated optic discs and peripapillary changes likely from previous chronic papilloedema. He did not have an LP. He subsequently underwent endoscopic repair of right frontal and cribriform defects and was treated with acetazolamide, brivaracetam, and lamotrigine. The rhinorrhoea and the headaches improved and he remained seizure-free.

Patient 5

A 38-year-old obese Black woman with a BMI of 42.3 kg/m2 had a 3-year history of intractable epilepsy with focal non-motor seizures with behavioural arrest and focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures. EEG recordings showed interictal bilateral temporal epileptiform activity and electroclinical focal seizures in the left temporal region. MRI showed a left mid-temporal encephalocoele and another small encephalocoele involving the right temporal lobe. She also had a partially empty sella turcica, dilated optic nerve sheaths, optic nerve tortuosity, prominent Meckel’s caves, and bilateral transverse venous sinus stenoses, suggesting chronically elevated ICP. She reported transient visual obscurations and pulsatile tinnitus in the past. She denied unusual headaches. Neuro-ophthalmological examination showed normal afferent visual function including full HVFs. Fundus examination revealed peripapillary changes and temporal pallor suggesting likely previous papilloedema. OCT showed mild thinning of the peripapillary retinal fibre layer and ganglion cell and inner plexiform layer in both eyes. Intracranial EEG electrodes recorded electroclinical focal to bilateral seizures with onset predominantly in the left temporal pole abutting the left encephalocoele. She underwent radiofrequency ablation of the left temporal lobe for intractable epilepsy. On topiramate, levetiracetam, and lamotrigine she continued to experience auras and memory impairment, but her seizure burden improved. She did not have an LP and she did not received acetazolamide because she had no symptoms of active IIH other than the seizures.

Discussion

Our five patients presented with new onset seizures secondary to frontal and temporal meningo-encephalocoeles in the setting of skull base thinning. The presence of multiple other radiological signs of chronically elevated ICP (Figure 1), spontaneous skull base CSF leaks in three patients, papilloedema in one patient (Figure 2), and optic disc and peripapillary changes in four patients, suggested likely previous papilloedema and was consistent with likely previously undiagnosed IIH.

In our series, three patients with a history of seizures and temporal lobe encephalocoeles had electroclinical seizures or interictal epileptiform activity or focal EEG slowing in one or both temporal lobes. Two patients with frontal lobe encephalocoeles had clinical seizures with reportedly normal interictal EEGs. In addition to the epileptogenic encephalocoeles, all patients had diffuse skull base bony defects and at least three typical radiological signs of chronically elevated ICP (empty sella turcica, dilated optic nerve sheaths, optic nerve tortuosity, posterior scleral flattening, prominent Meckel’s caves, or transverse venous sinus stenosis without thrombosis). Three patients had rhinorrhoea from spontaneous CSF leaks secondary to the skull base bony defects. All patients denied visual symptoms. Only one patient had very mild papilloedema and the other four patients had chronic peripapillary changes suggesting probable prior papilloedema. These patients were each managed differently, based on presentation and radiological findings. Patients with seizures were primarily under the care of epilepsy specialists, while CSF leak patients were treated by otorhinolaryngologists with surgical repair of bony defects. Three patients underwent LPs with opening pressures between 26 and 28 cm of water. Acetazolamide was prescribed when deemed necessary after treatment of the CSF leak and one patient was treated with bariatric surgery and rapid weight loss.

Most meningo-encephalocoele-related seizures result from bony defects located in the middle cranial fossa.18 Several studies have suggested an association between epilepsy secondary to temporal lobe meningo-encephalocoeles and obesity and MRI signs of chronically elevated ICP (Table 1). However, as shown in our patients, typical clinical manifestations of IIH such as papilloedema are not always present, most likely because a history of active IIH may be remote or because patients have developed a spontaneous skull base CSF leak resulting in decreased ICP and resolution of papilloedema.19

This case series highlights meningo-encephalocoele-related seizures as an unusual manifestation of unrecognised IIH. Chronically elevated ICP induces bony remodelling of the skull base as part of the expanding spectrum of IIH5 and is likely responsible for several of the unusual manifestations of chronically raised ICP, such as seizures.

Funding Statement

VB, NJN are supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Eye Institute core grant P30-EY06360 (Department of Ophthalmology, Emory University School of Medicine) and by a departmental grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY). WB received a scholarship from Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland.

Contributors

NAB, WB, AB, and RM collected the data, designed the manuscript, prepared the first draft, figure, table, and panel. VB, AMS and NJN designed the manuscript, contributed to the discussion, critically edited the review, and approved its final version.

Disclosure statement

None of the authors have any competing interest. VB is consultant for GenSight Biologics and Neuro-phoenix. NJN is consultant for GenSight Biologics, Santhera/Chiesi, Stoke, and Neurophoenix; receives research support from GenSight Biologics and Santhera/Chiesi.

References

- 1.Friedman DI, Liu GT, Digre KB.. Revised diagnostic criteria for the pseudotumor cerebri syndrome in adults and children. Neurology. 2013;81(13):1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0b013e3182a55f17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen BS, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Atypical presentations of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2020;11(1):25–38. doi: 10.4103/tjo.tjo_69_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mollan SP, Aguiar M, Evison F, Frew E, Sinclair AJ. The expanding burden of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Eye. 2019;33(3):478–485. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0238-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, et al. Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. New Engl J Med. 2019;381(25):2440–2450. doi: 10.1056/nejmsa1909301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biousse V, Newman NJ. The expanding spectrum of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Eye. 2022;37(12):2361–2364. doi: 10.1038/s41433-022-02361-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bidot S, Levy JM, Saindane AM, et al. Spontaneous skull base cerebrospinal fluid leaks and their relationship to idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2021;35(1):36–43. doi: 10.1177/1945892420932490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bialer OY, Rueda MP, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V, Saindane AM. Meningoceles in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(3):608–613. doi: 10.2214/ajr.13.10874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCorquodale D, Burton TM, Winegar B, Pulst SM. Teaching NeuroImages: Meningoencephalocele and CSF leak in chronic idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2016;87(20):e244. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000003330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urbach H, Jamneala G, Mader I, Egger K, Yang S, Altenmüller D. Temporal lobe epilepsy due to meningoencephaloceles into the greater sphenoid wing: a consequence of idiopathic intracranial hypertension? Neuroradiology. 2018;60(1):51–60. doi: 10.1007/s00234-017-1929-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell ZM, Hyer JM, Lauzon S, Bonilha L, Spampinato MV, Yazdani M. Detection and characteristics of temporal encephaloceles in patients with refractory epilepsy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39(8):1468–1472. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.a5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandhu MRS, Mandel M, McGrath H, et al. Management of patients with medically intractable epilepsy and anterior temporal lobe encephaloceles. J Neurosurg. 2022;136(3):709–716. doi: 10.3171/2021.3.jns21133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez-Poles J, Toledano R, Jiménez-Huete A, et al. Epilepsy associated with temporal pole encephaloceles. Clin Neuroradiol. 2021;31(3):575–579. doi: 10.1007/s00062-020-00969-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urbach H, Duman I, Altenmüller D, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension – a wider spectrum than headaches and blurred vision. Neuroradiol J. 2022;35(2):183–192. doi: 10.1177/19714009211034480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sayal AP, Vyas M, Micieli JA. Seizure as the presenting sign of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15(1):e246604. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-246604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graese P, Yazdani M, Campbell Z. Headache characteristics among patients with epilepsy and the association with temporal encephaloceles. IBRO Neurosci Rep. 2022;13:488–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ibneur.2022.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamali A, Park ES, Lee SA, et al. Introducing the “temporal thumb sign” in pediatric patients with new-onset idiopathic seizures with and without elevated cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure. Pediatr Neurol. 2023;140:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2022.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samudra N, Armour E, Gonzalez H, et al. Epilepsy with anterior temporal encephaloceles: baseline characteristics, post-surgical outcomes, and comparison to mesial temporal sclerosis. Epilepsy Behav. 2023;139:109061. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2022.109061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gompel JJV, Miller JW. How epileptogenic are temporal encephaloceles? Neurology. 2015;85(17):1440–1441. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000002073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bidot S, Levy JM, Saindane AM, Oyesiku NM, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Do most patients with a spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak have idiopathic intracranial hypertension? J Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2019;39(4):487–495. doi: 10.1097/wno.0000000000000761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]