Abstract

The enzyme S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) synthetase, the Escherichia coli metK gene product, produces SAM, the cell’s major methyl donor. We show here that SAM synthetase activity is induced by leucine and repressed by Lrp, the leucine-responsive regulatory protein. When SAM synthetase activity falls below a certain critical threshold, the cells produce long filaments with regularly distributed nucleoids. Expression of a plasmid-carried metK gene prevents filamentation and restores normal growth to the metK mutant. This indicates that lack of SAM results in a division defect.

S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM) is a central metabolite of Escherichia coli and other cells. Synthesized from methionine and ATP by the enzyme SAM synthetase (5), it is the major methyl donor in metabolism. It is also a precursor of spermidine, formed from decarboxylated SAM and putrescine.

SAM is an essential metabolite in yeast, where mutations causing a lack of SAM synthetase have been shown to be lethal unless SAM is provided in the medium (7). This has not been established for E. coli, because the cell is impermeable to SAM (13). However, SAM is generally assumed to be essential in E. coli, although no single SAM-dependent reaction has been shown to be indispensable.

In E. coli, SAM synthetase is the metK gene product (15). Mutants in metK have been isolated by virtue of their resistance to ethionine (9) and γ-glutamyl methyl ester (GGME) (19). In addition to resistance to methionine analogs, the various phenotypes reported for different (leaky) metK mutants include overproduction of methionine (9) and methionine or vitamin B12 auxotrophy or complete inability to grow on defined media (33). All such mutants show residual SAM synthetase activity. Attempts to isolate mutants totally deficient in MetK via temperature sensitivity of growth were not successful (11).

Even with some SAM synthetase activity, the leaky metK mutants show growth deficiencies (33) such that populations of metK cells quickly accumulate suppressor mutations; the only ones identified so far are in the lrp gene, coding for the leucine-responsive regulatory protein (21).

We show here that the unsuppressed metK84 mutant has a complex phenotype. Growth at normal rates in glucose minimal medium requires supplementation with a high concentration of leucine (50 μg/ml). Cells grown at lower concentrations of leucine are hindered in cell division and produce long filaments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultures and growth conditions.

The strains used in this study, all derivatives of E. coli K-12, are described in Table 1. The plasmids used were pBR322 (3) and pBAD22 (10). Minimal medium, LB, and growth conditions were as previously described (31, 34). Carbon sources were added at 0.2%. Kanamycin was provided at 50 μg/ml, chloramphenicol was provided at 30 μg/ml, ampicillin was provided at 100 μg/ml, and tetracycline was provided at 15 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

E. coli K-12 strains

| Strains | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| CU1008 | ilvA | L. S. Williams |

| DRN-1 | serA::Mud1 | 21 |

| MEW1 | CU1008 Δlac | 21 |

| MEW26 | MEW1 lrp::Tn10 | 21 |

| MEW30 | MEW1 metK84 | 21 |

| MEW45 | MEW1 lrp::lacZ | 20 |

| RG62 | metK84 lrp | 8, 21 |

| MEW305 | serA::λplacMu9 | Z. Q. Shao |

| MEW311 | MEW305 Δara714 | 6 |

| MEW402 | MEW1 metK84; leucine-requiring | This work |

| MEW403 | MEW1 metK84 lrp::lacZ | This work |

Genetic methods.

Plasmid isolations, DNA manipulations, transductions, and transformations were performed as described by Maniatis et al. (24) and Miller (27).

Enzyme assays.

β-Galactosidase was assayed in whole cells by the method of Miller and expressed in the units used previously (27). SAM synthetase assays were carried out as previously described (13).

Strain constructions.

The metK84 mutation used in this study was transferred from its strain of origin, RG62 (8), to our strain background (strain CU1008) by P1 cotransduction with serA+, forming strain MEW30 (21). Further transfers of metK were made with strain MEW30 as the donor and strain MEW311 serA::λplacMu Δara714 or strain DRN-1 serA::Mud1 as the recipient. lrp mutants were created by using phage grown on strain MEW26 lrp::Tn10, selecting on LB medium plus tetracycline, and verifying the ability to grow with serine as the carbon source (21).

Cloning the metK gene.

The metK gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA extracted from strain MEW1 by using primer 1, CATCCCATGGCAAAACACCTTTTTACGTCC, corresponding to 24 bp from the start of the gene preceded by 6 bases providing an NcoI site, and primer 2, ACGAAGCTTGAACGCAGGTGAAGAAAGATTAC, corresponding to 24 bp at the 3′ end of the gene plus a 6-bp extension providing a HindIII site. This DNA was subcloned into pBAD22ampr (10) by using the same two restriction enzymes. The cloned DNA was identified by sequencing with an ABI model 377 automatic sequencer with the same two primers. The sequence, read on both strands (except for the 10 codons at the 5′ end, which were read on one strand only), was identical to the metK sequence found in the E. coli genome but was significantly different from the previously published sequence (26).

Fluorescence microscopy.

Cell samples were prefixed with 0.25% formaldehyde (final concentration) and stored at 4°C. Subsequently, cells were postfixed by adding OsO4 to a final concentration of 0.1% and stained with 0.2 μg of DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride hydrate) per ml (final concentration) for at least 1 h. The cells were concentrated by centrifugation and immobolized on object slides coated with a dried layer of 2% agarose. The preparations were illuminated at 330 to 380 nm. Images were taken with a Princeton charged-coupled-device camera mounted on an Olympus BH-2 fluorescence microscope equipped with a 100× phase-contrast Neofluar oil immersion lens, a 3.3× photo-ocular, and an emission filter of 420 nm.

Dark-field microscopy.

A wet mount of cells in liquid culture was prepared and placed in a Leitz Dialux EB20 microscope equipped with a dark-field condenser and a quartz-iodine light source. For examination under oil immersion, the no. 2 aperture could be stepped down by means of an adjustable rotating collar. Photomicrographs were taken with a WildMPS45 camera, top-mounted on the microscope.

RESULTS

Leucine requirement in an unsuppressed metK84 mutant.

The metK84 mutant RG62 was isolated by virtue of its ethionine resistance; it is also resistant to GGME and has a lower SAM pool (8). We showed that this strain at some point in its history had acquired an lrp mutation which conferred faster growth in glucose (21). In fact, the original RG62 isolate grew poorly on minimal glucose plates but faster in the presence of 5 mM leucine (8, 21), conditions in which Lrp exerts weaker regulation on many of its operons (29, 30). These observations suggested that a metK84 single mutant might require l-leucine for growth; as a result, we reconstructed such a strain by cotransduction, using phage P1 grown on MEW30 metK84 to transduce strain MEW311 (serA::λplacMu) to serine independence and selecting on minimal medium containing glucose, isoleucine, valine, and l-leucine (100 μg/ml). We found several leucine-requiring GGME-resistant strains and studied one further, strain MEW402. We grew strain MEW402 in liquid culture with concentrations of leucine ranging from 0 to 50 μg/ml and found that even 25 μg/ml was limiting for growth. This requirement is not likely to reflect a failure in leucine biosynthesis since biosynthetic mutants require less than 10 μg of leucine per ml (4). We suggest that this high leucine requirement reflects the need to inactivate Lrp when MetK84 activity becomes limiting, because Lrp either represses a gene whose expression becomes essential under these conditions or activates a gene whose expression becomes harmful.

Filamentation in leucine-starved metK84 mutants.

We have previously shown that the doubling time of metK strains in minimal medium is considerably shorter in the presence of leucine (85 min) than in its absence (>120 min). Nevertheless, these strains accumulate leucine-independent derivatives (data not shown). Experiments involving strain MEW402 were therefore done with recently constructed strains. When a fresh transductant was inoculated into glucose minimal medium and examined 14 to 18 h later, little or no growth was seen without leucine present, whereas the culture with 50 μg of leucine per ml grew to the same density as the leucine-nonrequiring parent strain. Cultures grown with 25 μg of leucine per ml had lower densities than those grown with 50 μg/ml; they also showed a striking morphological change.

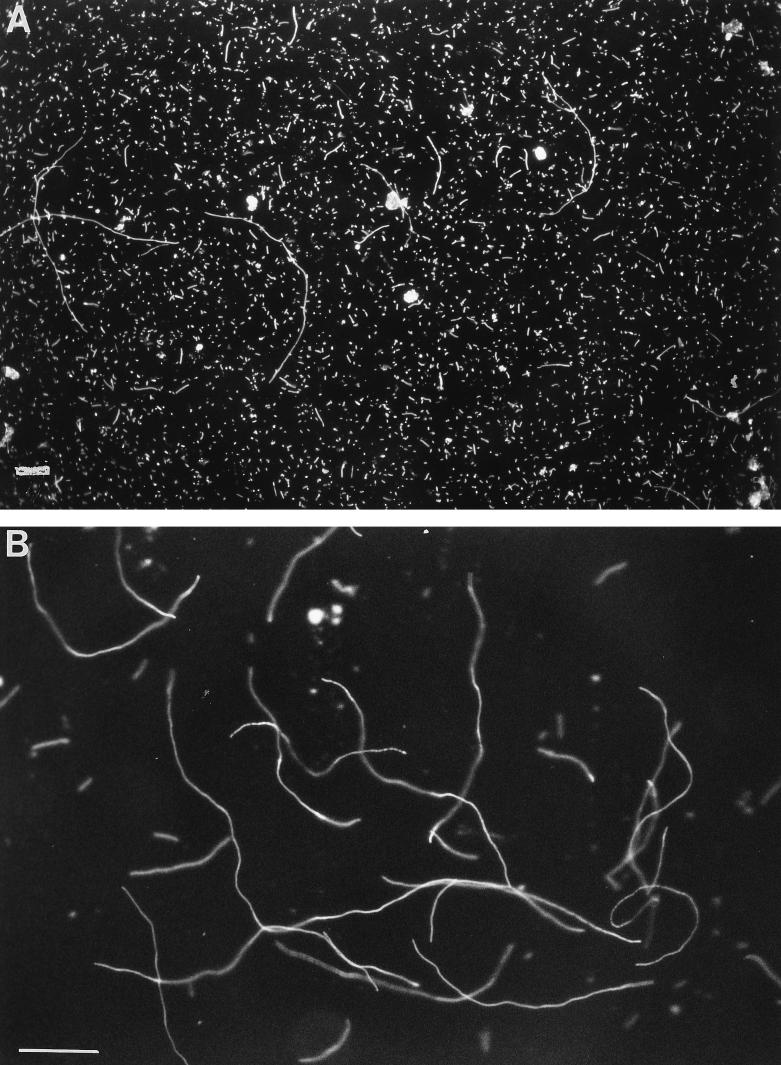

As shown in the photomicrographs (Fig. 1), the culture grown with 25 μg of leucine per ml contained a large proportion of very long filaments, some as long as 100 μm, i.e., 50 times the normal E. coli cell length; shorter filaments and cells of normal cell length were also seen. Cultures grown with 50 μg of leucine per ml consisted mainly of normal-length cells with a few filaments, occasionally very long. These filaments could also be observed in cultures grown with limiting leucine in the presence of GGME.

FIG. 1.

Filaments of the metK84 mutant grown under limiting leucine conditions. The photomicrographs of strain MEW402 were taken under dark-field illumination. (A) Culture growing with 50 μg of leucine per ml; bar, 20 μm. (B) Culture growing with 10 μg of leucine per ml; bar, 10 μm.

Linkage of the determinant for leucine requirement and filamentation to serA.

Strain MEW402 showed three phenotypes: GGME resistance, a leucine requirement, and filamentation on starvation for leucine. GGME resistance was highly linked to serA. In a transduction of metK into DRN-1 (serA::lacZ), selecting serine independence as described above, 10 of 46 colonies tested from the transduction plates grew in the presence of GGME. This linkage is in reasonable agreement with the known map positions of metK and serA (66.4 and 65.8 min, respectively). We purified the 46 transductants on the same minimal glucose plates supplemented with leucine. After three purifications on the same medium, three of the GGME-resistant transductants required leucine. It is clear that the leucine requirement is also caused by a gene linked to serA.

To show that the filamentation of strains grown with leucine limitation was linked to metK, we verified that strain MEW402 would produce filaments even in the presence of 500 μg of GGME per ml and then inoculated the 10 GGME-resistant strains directly from the colonies on the transduction plates into liquid minimal medium with isoleucine and valine, 500 μg of GGME per ml, and a limiting concentration of leucine, 10 μg/ml. We found some long filaments in 9 of the 10 cultures tested, although most of the cells were normal. It is clear that filamentation is also linked to serA.

The preceding linkage data are generally consistent with leucine auxotrophy and filamentation being due to the metK mutation. The reason that the expected 100% linkage of GGME resistance to these phenotypes was not obtained is likely to reflect the rapid appearance of suppressors during purification of transductants. As a further test to show that filamentation is due to the metK mutation, we wanted to determine whether a plasmid providing metK function could prevent filamentation and restore normal growth.

Suppression of filamentation by a plasmid-carried metK gene.

To determine whether a metK+ plasmid could suppress filamentation, we grew strain MEW402(pBADmetK) in glucose minimal medium with 50 μg of leucine per ml and 200 μg of ampicillin per ml, subcultured the strain in the same medium for 4 h with fresh ampicillin, and then subcultured it in glucose minimal medium with ampicillin and with 0, 10, 25, and 50 μg of leucine per ml, each with and without 500 μg of arabinose per ml.

Cultures without arabinose grew well with 50 μg of leucine per ml but produced much less dense cultures consisting mainly of long filaments at lower concentrations of leucine or completely without it. All cultures with arabinose grew to the usual density of E. coli overnight cultures (whatever the leucine concentration used) and consisted entirely of normal-size, nonfilamentous cells. It is clear that even in the presence of glucose, 500 μg of arabinose per ml can induce sufficient metK gene product to restore normal growth. To verify that the arabinose cultures were still composed of mutant cells, we plated the culture grown with glucose, 10 μg of leucine per ml, and 500 μg of arabinose per ml on LB medium, replicated the culture on LB medium plus ampicillin, picked one of the very rare ampicillin-sensitive colonies, and noted the filaments it made when grown with glucose and 10 μg of leucine per ml.

Suppression of filamentation by Lrp deficiency.

We showed earlier that Lrp deficiency restores a normal growth rate to the metK mutant. To determine whether the other phenotypes were also suppressed, we transduced lrp::lacZ from strain MEW45 into strain MEW402, producing strain MEW403 lrp::lacZ metK. This strain had no leucine requirement and showed no filaments.

Effects of leucine and Lrp on SAM synthetase activity.

A simple explanation of the Lrp effect on the metK84 mutant is that Lrp represses the metK gene, so that the absence of Lrp or the presence of leucine in the medium results in higher levels of SAM synthetase, which, in the case of the mutant enzyme, could have a significant effect on the SAM pool. To test this hypothesis, we assayed SAM synthetase activity in extracts of the metK and lrp mutants, a metK lrp double mutant, and our parental strain, grown in the presence or absence of leucine.

It is clear that SAM synthetase is induced either by leucine or by an lrp mutation (Table 2). The effects are small in the parental strain but large in the metK mutant, for which either condition increased SAM synthetase sevenfold. It seems that a SAM synthetase level over 0.25 nmol/min/mg of protein suffices for normal growth and that the parental strain produces a considerable excess of this enzyme. In the metK84 lrp double mutant, a level of 0.28 nmol/min/mg of protein is reached without leucine and not further increased in cells grown with leucine.

TABLE 2.

SAM synthetase activity of metK and lrp mutants

| Mediuma | SAM synthetase activity (nmol/min/mg of protein) in:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTb | lrp | metK84 | lrp metK84 | |

| −Leucine | 2.3 | 4.6 | 0.04 | 0.28 |

| +Leucine | 2.9 | 6.3 | 0.26 | 0.29 |

Cultures were grown in glucose-minimal medium with (+) and without (−) 100 μg of leucine per ml, and SAM synthetase was assayed. The cultures assayed were also examined with a microscope; all cells were short rods, except for cells of the metK84 mutant grown without leucine, which consisted mainly of filaments. The cultures used were MEW1 (wild type [WT]), MEW45 (lrp::kan), MEW402 (metK84), and MEW403 (lrp::kan metK84).

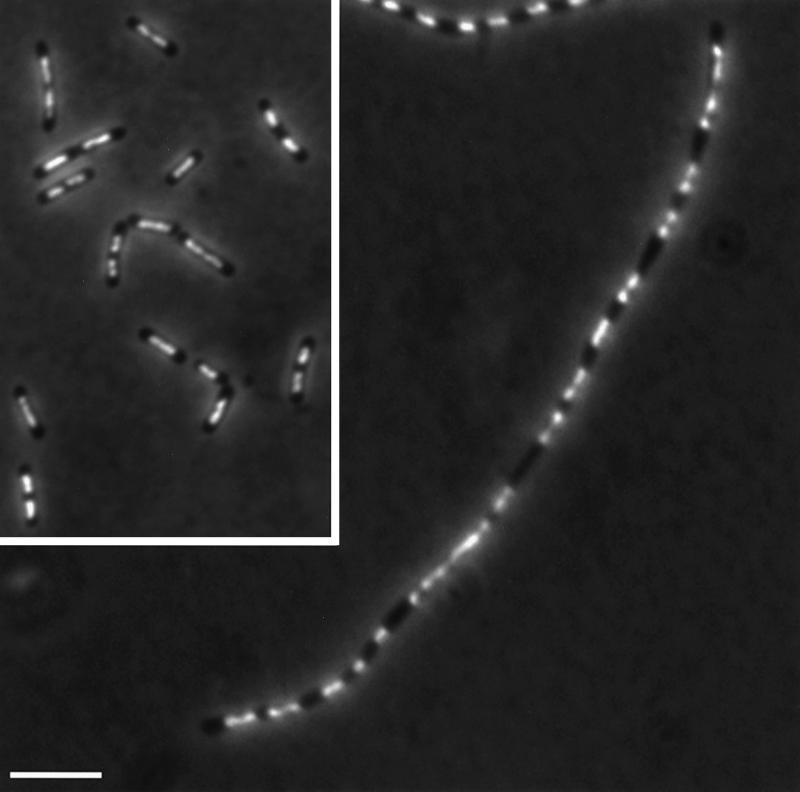

Nucleoid partioning in metK filaments.

E. coli populations produce filaments in response to a variety of mutations and environmental problems, although few of the filaments are as long as those shown in Fig. 1A. If the primary defect in the metK84 mutant involves DNA replication, while protein synthesis and cell wall elongation continue, one would expect to see long filaments with few nucleoids, as in filaments in which DNA synthesis has been blocked (2, 17, 28). If DNA synthesis is normal but septum formation is specifically inhibited, one would expect to see many evenly spaced nucleoids, with or without constrictions at the presumptive division site (18, 35).

To investigate nucleoid partitioning in the metK84 filaments, we took samples from cultures grown in glucose minimal medium with 25 or 50 μg of leucine per ml and fixed them for fluorescence microscopy. All filaments showed partitioned nucleoids (Fig. 2), indicating that DNA replication and nuclear segregation continue.

FIG. 2.

Nucleoid segregation in metK filaments. A culture of strain MEW402 was grown for 19 h with 25 μg of leucine per ml and prepared for fluorescence microscopy as described in Materials and Methods; control cells grown with 50 μg/ml are shown in the inset. It can be seen that the nucleoids are segregated uniformly along the length of the filament. Most nucleoid regions are in the form of a dumbbell, which presumably represents two not fully separated chromosomes. Analysis of the relative amount of DNA per individual nucleoid region by integrated density measurement shows that this filament contains 16 nucleoid equivalents. Bar, 5 μm.

DNA methylation in the metK84 strain MEW402.

E. coli DNA is normally methylated at GATC sequences by the Dam methylase (25). Although DNA synthesis continues in the metK84 mutant, when SAM synthetase activity is limiting, the DNA might be undermethylated, as has been observed when the SAM pool is lowered by expression of a SAM hydrolase (14). We tested this by transforming metK84 cells with pBR322, a multicopy plasmid containing 22 GATC sites (3). We isolated plasmid DNA from cells grown with 25 μg of leucine per ml, verified microscopically that the culture contained filaments, and showed that plasmid DNA was cut by restriction endonuclease DpnI, which cuts only methylated GATC sequences, and by Sau3, which cuts any GATC site, but not by MboI, which cuts only nonmethylated GATC sites. We conclude that metK84 cells methylate most of their GATC sequences and thus are not totally starved for SAM.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we present a new phenotype associated with decreased SAM synthetase activity in E. coli, a partial cell division defect resulting in the formation of long filaments, more than 50 times the normal cell length (Fig. 1). The filaments contain nucleoids evenly dispersed along their length (Fig. 2), suggesting that they have no problem in synthesizing and partitioning DNA but they do not form cross walls. The parental phenotype (growth as small rods) is restored by expression of metK from a plasmid-carried gene. This suggests that SAM is involved in septation.

Regulation of metK expression.

Leucine has a strong effect on the metabolism of the metK84 mutant, which is partially defective in SAM synthetase. A nearly normal growth rate can be restored to the metK84 mutant by the presence of leucine in the medium or by the loss of Lrp, as previously reported (8, 21). We show here that filamentation, too, is suppressed by exogenous leucine or by an lrp mutation. Growth rate, leucine independence, and a normal cell size were also restored by expression of metK carried on pBR322 under control of the arabinose promoter.

Slow growth and filamentation are observed in the metK84 mutant when SAM synthetase levels are extremely low, and suppressing conditions, i.e., the presence of leucine or the absence of Lrp, increase these levels more than sixfold. From this correlation, we conclude that SAM synthetase at 0.26 nmol/min/mg of protein is sufficient for normal growth and division, whereas a level of 0.04 nmol/min/mg of protein is insufficient. Our results can thus be explained in terms of the regulation of SAM synthetase activity.

The increased SAM synthetase activity observed in metK84 strains in the presence of leucine or in the absence of Lrp could reflect the expression, under these conditions, of a second SAM synthetase, and indeed the existence of such an enzyme, a product of the metX gene, has been suggested (33). However, a BLAST search (1) revealed no metK homolog in the E. coli genome, a significant result given the high conservation of SAM synthetases (e.g., E. coli MetK is 55.7% identical and 70% similar to the human enzyme). We conclude that there is only one E. coli gene coding for SAM synthetase, metK.

The observed variations in SAM synthetase activity must therefore reflect regulation of the metK gene. The simplest explanation of our results is that Lrp represses metK expression and leucine antagonizes Lrp, analogous to the action of Lrp and leucine on sdaA expression (21). This hypothesis is reinforced by the observation that loss of Lrp increases SAM synthetase activity in wild type cells as well (Table 2).

In this work, we tried to decrease SAM by decreasing SAM synthetase. This was done earlier by expression of a cloned SAM hydrolase (14). Cells became elongated and occasionally filamentous, but no leucine requirement was found. The authors concluded that SAM plays a direct or indirect role in cell division.

Role of SAM in cell division.

Why a low SAM level leads to a cell division block is unclear. This could be a direct or indirect effect on cell division. One possibility involves the elongation factor Tu, discovered for its role in translation but involved in other processes as well. EF-Tu associates with the cell membrane (16). Part of the EF-Tu population is methylated at Lys56 (22), and the membrane-associated molecules are preferentially methylated under starvation conditions (36). Furthermore, certain mutants with altered EF-Tu form filaments (37). A role of methylated EF-Tu in cell division is conceivable.

Another possibility for a role of SAM in cell division is as methyl donor at some particular step of the division process. The ftsJ gene product has a SAM-binding motif and might be a methyl transferase involved in cell division (32). The early steps in septation involve the formation of rings of the tubulin-like FtsZ protein, in association with the membrane protein ZipA and a number of other division proteins, leading to constriction and separation of the daughter cells (12, 23). Any of these division proteins might be activated by methylation, making a SAM-dependent step in division. While many cell division functions have been identified genetically in E. coli, at present there are no data on their methylation status. We are trying to determine the precise division step at which the metK84 filaments are blocked, and we are investigating the possibility that some division protein may be methylated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant A6050 from the Canadian National Science and Engineering Research Council, for which we are extremely grateful.

We thank Patrick Deschavanne for help with the BLAST search for metK analogs, P. G. Huls for help with microscopy, I. Krantz for help with sequencing, and V. P. Mathur, H. S. Su, and Z. Q. Shao for advice and discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E M, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Begg K J, Donachie W D. Experiments on chromosome partitioning and positioning in Escherichia coli. New Biol. 1991;3:475–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolivar F, Rodriguez R L, Greene P J, Betlach M C, Heyneker H L, Boyer H W, Cross J H, Falkow S. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. II. A multi-purpose cloning system. Gene. 1977;2:95–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns R O, Calvo J, Margolin P, Umbarger H E. Expression of the leucine operon. J Bacteriol. 1966;91:1570–1576. doi: 10.1128/jb.91.4.1570-1576.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantoni G L. Activation of methionine for transmethylation. J Biol Chem. 1951;189:745–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C F, Lan J, Korovine M K, Shao Z Q, Tao L, Zhang J, Newman E B. Metabolic regulation of lrp gene expression in Escherichia coli K-12. Microbiology. 1997;143:2079–2084. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-6-2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherest H, Surdin-Kerjan Y, Exinger F, Lacroute F. S-Adenosylmethionine-requiring mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: evidences for the existence of two methionine adenosyl transferases. Mol Gen Genet. 1978;163:153–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00267406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greene R C, Hunter J S V, Coch E H. Properties of metK mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1973;115:57–67. doi: 10.1128/jb.115.1.57-67.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greene R C, Su C-H, Holloway C T. S-adenosylmethionine synthetase deficient mutant of Escherichia coli K-12 with impaired control of methionine biosynthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1970;38:1120–1125. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guzman L M, Belin D, Carson M J, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hafner E W, Tabor C W, Tabor R. Isolation of a metK mutant with a temperature-sensitive S-adenosylmethionine synthetase. J Bacteriol. 1977;132:832–840. doi: 10.1128/jb.132.3.832-840.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hale C A, de Boer P A. Direct binding of FtsZ to ZipA, an essential component of the septal ring structure that mediates cell division in E. coli. Cell. 1997;88:175–185. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81838-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holloway C T, Greene R C, Su C-H. Regulation of S-adenosylmethionine synthetase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1970;104:734–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.104.2.734-747.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes J A, Brown L R, Ferro A J. Expression of the cloned coliphage T3 S-adenosylmethionine hydrolase gene, DNA methylation, and polyamine biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3625–3632. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3625-3632.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter J S V, Greene R C, Su C H. Genetic characterization of the metK locus in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1975;122:1144–1152. doi: 10.1128/jb.122.3.1144-1152.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson G R, Rosenbusch J P. Abundance and membrane association of elongation factor Tu in E. coli. Nature. 1976;261:23–26. doi: 10.1038/261023a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaffé A, D’Ari R, Norris V. SOS-independent coupling between DNA replication and cell division in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:66–71. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.1.66-71.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaffé A, D’Ari R, Hiraga S. Minicell-forming mutants of Escherichia coli. Production of minicells and anucleate rods. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3094–3101. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3094-3101.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraus J, Soll D, Low K B. Glutamyl-γ-methyl ester acts as a methionine analog in Escherichia coli: analog resistant mutants map at the metJ and metK loci. Genet Res Camb. 1979;33:49–55. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300018152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin R, D’Ari R, Newman E B. λplacMu insertions in genes of the leucine regulon: extension of the regulon to genes not regulated by leucine. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1948–1955. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.6.1948-1955.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin R T, D’Ari R, Newman E B. The leucine regulon of Escherichia coli: a mutation in rblA alters expression of l-leucine-dependent metabolic operons. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4529–4535. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4529-4535.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.L’Italien J J, Laursen R A. Location of the site of methylation in elongation factor Tu. FEBS Lett. 1979;107:359–362. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)80407-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lutkenhaus J, Addinall S G. Bacterial cell division and the Z ring. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:93–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marinus M G. Methylation of DNA. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella, cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 782–791. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markham G D, DeParasis J, Gatmaitan J. The sequence of metK, the structural gene for S-adenosylmethionine synthetase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:14505–14507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulder E, Woldringh C L. Actively replicating nucleoids influence positioning of division sites in Escherichia coli filaments forming cells lacking DNA. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4303–4314. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4303-4314.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newman E B, Lin R T. Leucine-responsive regulatory protein, a global regulator of gene expression in E. coli. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:747–775. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman E B, Lin R T, D’Ari R. The leucine/Lrp regulon. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1513–1525. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newman E B, Miller B, Colebrook L D, Walker C. A mutation in Escherichia coli K-12 results in a requirement for thiamine and a decrease in l-serine deaminase activity. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:272–276. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.1.272-276.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogura T, Tomoyasu T, Yuki T, Morimura S, Begg K J, Donachie W D, Mori H, Niki H, Hiraga S. Structure and function of the ftsH gene in Escherichia coli. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:279–282. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satishchandran C, Taylor J C, Markham G D. Novel Escherichia coli K-12 mutants impaired in S-adenosylmethionine synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4489–4496. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4489-4496.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su H, Newman E B. A novel l-serine deaminase activity in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2473–2480. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2473-2480.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Helvoort J M L M, Kool J, Woldringh C L. Chloramphenicol causes fusion of separated nucleoids in Escherichia coli K-12 cells and filaments. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4289–4293. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4289-4293.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young C C, Bernlohr R W. Elongation factor Tu is methylated in response to nutrient deprivation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3096–3100. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.10.3096-3100.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeef L A, Mesters J R, Kraal B, Bosch L. A growth-defective kirromycin-resistant EF-Tu Escherichia coli mutant and a spontaneously evolved suppression of the defect. Gene. 1995;165:39–43. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00487-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]