Abstract

The gene encoding the general stress transcription factor ςB in the gram-positive bacterium Listeria monocytogenes was isolated with degenerate PCR primers followed by inverse PCR amplification. Evidence for gene identification includes the following: (i) phylogenetic analyses of reported amino acid sequences for ςB and the closely related ςF proteins grouped L. monocytogenes ςB in the same cluster with the ςB proteins from Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus, (ii) the gene order in the 2,668-bp portion of the L. monocytogenes sigB operon is rsbU-rsbV-rsbW-sigB-rsbX and is therefore identical to the order of the last five genes of the B. subtilis sigB operon, and (iii) an L. monocytogenes ςB mutant had reduced resistance to acid stress in comparison with its isogenic parent strain. The sigB mutant was further characterized in mouse models of listeriosis by determining recovery rates of the wild-type and mutant strains from livers and spleens following intragastric or intraperitoneal infection. Our results suggest that ςB-directed genes do not appear to be essential for the spread of L. monocytogenes to mouse liver or spleen at 2 and 4 days following intragastric or intraperitoneal infection.

Regulation of gene expression in response to environmental stress conditions is essential for bacterial survival (57). Host-imposed stress conditions include the acidic pH of the stomach for orally transmitted pathogens and the acidic pH and oxidative stress inside the host cell vacuole for intracellular pathogens. The gram-positive facultative intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes is subjected to both classes of stress during the course of a food-borne infection. The association of alternative sigma factors with core polymerase provides a mechanism for alterations in gene expression by directing transcription of new regulons in response to cellular signals (27). Well-characterized stress responses regulated by alternative sigma factors include sporulation in Bacillus subtilis (41) and the stationary phase (57) and heat shock responses (62) in Escherichia coli.

In some gram-negative pathogens, the stress-responsive alternative sigma factor RpoS has been shown to contribute to virulence. For example, RpoS regulates the expression of the plasmid virulence genes spvABCD in Salmonella and of the virulence gene yst in Yersinia enterocolitica (14, 30). Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella dublin rpoS mutants have increased susceptibility to nutrient deprivation, oxidative stress, and acid stress and significantly reduced virulence in mice (14, 21, 55). An altered rpoS allele in S. typhimurium contributes to avirulence in the laboratory strain LT2 (55).

In contrast, little is known regarding the contribution of stress-responsive sigma factors to virulence in gram-positive organisms. One well-studied example of such a sigma factor is ςB, which has been predominantly characterized for Bacillus subtilis (9–11, 19, 25, 26) but has also been reported for Staphylococcus aureus (58). ςB-dependent transcription in B. subtilis is activated upon entry into stationary phase or following exposure to various environmental stress and growth-limiting conditions, including heat shock, oxygen limitation, or exposure to ethanol and high salt concentrations (6, 8, 10, 12, 52). While disruption of sigB in B. subtilis has no apparent effect on the organism’s ability to sporulate or to grow under many conditions (19, 25, 29, 32), ςB mutants have been shown to be sensitive to oxidative stress (4, 20).

As a facultative intracellular pathogen, L. monocytogenes provides a model system for studying the role of alternative sigma factors, specifically ςB, in the virulence of gram-positive bacteria. We report the identification of a ςB homolog in L. monocytogenes. Our results indicate that although loss of ςB function diminishes acid resistance in L. monocytogenes, ςB-directed genes do not appear to be essential for the spread of the organism to mouse liver and spleen 2 and 4 days after intragastric or intraperitoneal infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

L. monocytogenes 689426 was used to determine the sigB sequence as well as a partial sequence of the sigB operon. Furthermore, sigB was sequenced from L. monocytogenes 2289 and 10403S and from Listeria innocua DD 680. L. monocytogenes 10403S was used to generate the sigB mutant.

Cloning and sequencing of sigB.

Based on the reported sigB sequences for B. subtilis (19) and S. aureus (58), two degenerate primers (LmsigB-1 and LmsigB-2 [Table 1]) were designed to amplify an internal sigB fragment from L. monocytogenes. These two primers were used in a touchdown PCR protocol (47) with an initial annealing temperature of 62°C, which was decreased by 0.5°C/cycle for 20 cycles, followed by 20 cycles with an annealing temperature of 52°C. This reaction led to amplification of a strong, single DNA fragment of the expected size (403 bp) from L. monocytogenes 689426. With BLASTN (3), this fragment shared 66 and 65% identities with the corresponding sigB regions from B. subtilis and S. aureus, respectively. This sequence was used to design primers LmsigB-3 and LmsigB-4 for inverse PCR amplification of the region adjacent to the 5′ end of the initial fragment. For inverse PCR, 10 μg of chromosomal DNA, isolated as described by Flamm et al. (23), was digested with selected restriction enzymes. Self-ligation of the digested DNA was performed at several DNA concentrations (0.5, 1.0, 2.25, 5, and 15 μg/μl) with a 50-μl reaction volume with 1 U of T4 DNA ligase (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). Subsequent PCR was performed with 5 ng of the self-ligated DNA per reaction. Primers LmsigB-3 and LmsigB-4 yielded a PCR product of approximately 415 bp with Sau3AI-digested chromosomal DNA. The degenerate primer LmrsbW-1 was designed based on the reported rsbW sequences for B. subtilis and S. aureus to allow amplification of DNA sequences 5′ to those previously obtained. PCR amplification with LmrsbW-1 and LmsigB-10 yielded a PCR product of approximately 715 bp, providing an additional 112 bp 5′ of the Sau3AI inverse PCR product. Further inverse PCR amplification with LmrsbW-3 and LmrsbW-4 and with LmsigB-17 and LmsigB-18 on Sau3AI- and HindIII-digested chromosomal DNA, respectively, yielded an additional 1,195 bp of sequence information. With two primer sets (LmsigB-8 and LmsigB-12 along with LmsigB-19 and LmsigB-20), a 1,000-bp fragment and a 460-bp fragment were amplified from HindIII- and NlaIII-digested chromosomal DNAs, respectively, yielding sequence information 3′ of the initially amplified internal L. monocytogenes sigB fragment.

TABLE 1.

PCR primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| LmsigB-1 | AC(A/G) TGC ATT TGA (C/G)(A/T)T A(A/T)A CCG A |

| LmsigB-2 | G(C/T)G T(A/T)C ATG T(G/T)C CGA GAC G |

| LmsigB-3 | TTT GCG GCG AGC TTT GTA AT |

| LmsigB-4 | CAT CGG TGT CAC GGA AGA AGA A |

| LmsigB-10 | CCC GTT TCT TTT TGA CTG C |

| LmsigB-12 | CAT TTA TTG AAA ATC GCA GTC |

| LmsigB-15 | AAT ATA TTA ATG AAA AGC AGG TGG AG |

| LmsigB-16 | ATA AAT TAT TTG ATT CAA CTG CCT T |

| LmsigB-17 | ACT TGA TAT ACT TCA AGT GCT |

| LmsigB-18 | GGG TAT AGT ACT TCG AAT CG |

| LmsigB-19 | CGA ATA TTA CCC ATA CCA G |

| LmsigB-20 | TAT GAT TGG GAT GGA AG |

| LmrsbW-1 | AAG GG(A/T) GAC AG(C/T) TTT GA(C/T) T(A/T)T GA |

| LmrsbW-3 | GGC ATT CTC CTC CAC CTG |

| LmrsbW-4 | CTC AAC CTG ATA AAG AGG CG |

| SOE-Aa | GGA ATT CCA GGT GGA GGA GAA TGC |

| SOE-Bb | CAC ACG TTC AAA TCC ATC ATC TGC AGC AAA TGC TTC AAA G |

| SOE-C | GAT GAT GGA TTT GAA CGT GTG |

| SOE-Dc | GCT CTA GAA CAT CCC CGC AGT ATT G |

The EcoRI restriction site incorporated into this primer to facilitate cloning is underlined.

The overhang complementary to SOE-C is underlined.

The XbaI restriction site incorporated into this primer to facilitate cloning is underlined.

For sequencing, PCR products were cloned into the pCR 2.1 vector with the Original TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Plasmids were purified with the QIAquick Plasmid Purification kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.) and used for DNA sequencing. To compare sigB allelic variations among L. monocytogenes strains, PCR primers LmsigB-15 and LmsigB-16 (Table 1) were used to amplify the complete sigB open reading frames (ORFs) from two additional L. monocytogenes strains and from L. innocua. The PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen) and then sequenced directly with the same primers.

DNA and protein sequence analyses were performed with Lasergene software (DNAStar, Madison, Wis.). Alignments were performed by the Clustal method (MEGALIGN). Phylogenetic analyses of ςB and ςF amino acid sequences were performed with Seqboot, Protdist, Neighbor, Consense, and Drawtree in the software package PHYLIP, version 3.57c (22).

Generation of an L. monocytogenes sigB mutant.

A nonpolar internal deletion mutant allele of sigB was created in the E. coli-L. monocytogenes shuttle vector pKSV7 by SOE (splicing by overlap extension) PCR (28) and was introduced into L. monocytogenes 10403S by allelic exchange mutagenesis. SOE PCR primers were designed to amplify two ∼300-bp DNA fragments, one comprising the 5′ end of sigB (nucleotides [nt] 1217 to 1490, amplified by primers SOE-A and SOE-B [Table 1]) and one comprising the 3′ end of sigB (nt 1788 to 2087, amplified by primers SOE-C and SOE-D [Table 1]). Subsequent PCR amplification with SOE-A and SOE-D created a 600-bp sigB fragment with an in-frame 297-bp deletion. This fragment was purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen) and was then digested with XbaI and EcoRI. The purified fragment was cloned into pKSV7 and transformed into E. coli DH5-α. The resulting plasmid, pTJA-57, was subsequently electroporated into L. monocytogenes 10403S as previously described (13), and transformants were selected on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar plates containing 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. A transformant was serially passaged at 42°C to direct chromosomal integration of the plasmid by homologous recombination. A single colony with a chromosomal integration was serially passaged in BHI and replica plated to obtain an allelic exchange mutant. Allelic exchange mutagenesis was confirmed by PCR amplification and direct sequencing of the PCR product (data not shown).

Acid tolerance assay.

The ability of L. monocytogenes to survive acid stress was evaluated as described by Wilmes-Riesenberg et al. (55), with some minor modifications. Briefly, 1 ml of L. monocytogenes cells grown overnight in BHI broth was pelleted and then resuspended in 10 ml of BHI agar (pH 2.5). Aliquots were removed immediately and at 30, 60, and 120 min for plating on BHI agar plates.

Mouse virulence assays.

Lightly anesthetized BALB/c mice (approximately 6 weeks old) were infected either intraperitoneally with approximately 2 × 104 bacteria (37) or intragastrically with approximately 2 × 109 bacteria in 0.9% saline (5). The mice were housed in an AAALAC-International accredited facility, and animal experiments were reviewed and approved by Cornell University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Food was withheld from the mice for 5 to 6 h prior to infection. Bacterial numbers in spleens and livers were determined at days 2 and 4 postinoculation. The results are expressed as mean values and standard deviations for five mice.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence of the L. monocytogenes 689426 sigB region has been assigned GenBank accession no. AF032444. The sigB sequences of L. monocytogenes 2289 and 10403S and L. innocua DD 680 have been assigned GenBank accession no. AF032445, AF032446, and AF032447, respectively.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of sigB and the partial sigB operon.

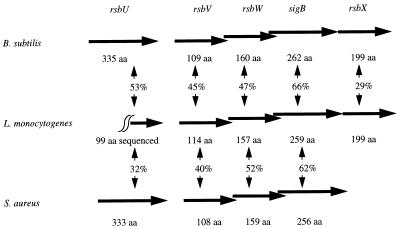

The complete DNA sequence obtained by PCR with degenerate primers followed by inverse PCR amplification was deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF032444. Because cloned PCR products are potentially subject to sequence alterations due to PCR misincorporation, our sigB DNA sequence was confirmed by directly sequencing a PCR product comprising the complete sigB open reading frame (ORF). Furthermore, overlapping sequences obtained by independent inverse PCR amplifications showed no sequence variations. DNA sequence analyses revealed one partial and four complete ORFs with significant predicted amino acid identities to RsbU, RsbV, RsbW, ςB, and RsbX in B. subtilis and RsbU, RsbV, RsbW, and ςB in S. aureus (Fig. 1). The rsbV ORF is preceded by a possible ςB promoter site. Alignments of the L. monocytogenes predicted amino acid sequences with RsbU, RsbV, RsbW, and ςB from B. subtilis and S. aureus and RsbX from B. subtilis are shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the organization of the sigB operon in L. monocytogenes, B. subtilis, and S. aureus. Predicted protein sizes and identities are indicated. For L. monocytogenes RsbU, a 99-aa C-terminal sequence was used for the calculation of identities.

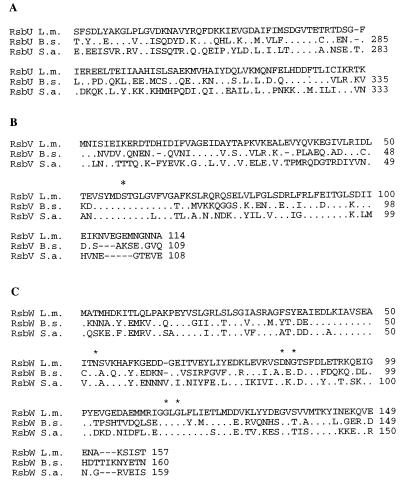

FIG. 2.

Alignments of the deduced ςB and Rsb amino acid sequences from L. monocytogenes (L.m.), B. subtilis (B.s.), and S. aureus (S.a.). The L. monocytogenes sequence is always shown on top; for the other species, amino acids are listed only when they differ from the L. monocytogenes sequence. Symbols: ., an amino acid that is identical to the L. monocytogenes sequence; −, a gap. (A) Alignment of the partial C-terminal L. monocytogenes RsbU sequence (99 aa) with the homologous regions of B. subtilis and S. aureus. (B) RsbV alignment. An asterisk above the alignment indicates a conserved serine residue that represents the site of phosphorylation by RsbW (33). (C) RsbW alignment. Asterisks above the alignment indicate conserved amino acid residues which are thought to be important for ATP binding in RsbW and in histidine kinases (33). (D) ςB alignment. This alignment also includes the amino acid sequence from L. innocua DD 680 (L.i.). The regions and subregions of ςB are indicated above the alignment (40). Amino acid conservation, calculated as the percent residues conserved in all four species relative to the number of residues in a given region, is indicated for each region. Numbers below the alignment indicate residues important for promoter recognition in region 2.4 (1 to 3) and in region 4.2 (4 to 6) for the following sigma factors (39): 1, Q-196 in B. subtilis ςA (35), R-96 in B. subtilis ςH (15), and Q-437 in E. coli RpoD (53); 2, T-440 in E. coli RpoD (48); 3, T-100 in ςH (63) and M-124 in ςE (50); 4, R-584 in E. coli RpoD (48); 5, mutations in this region switch promoter specificity among ςB, ςF, and ςG in B. subtilis (39); and 6, R-588 in E. coli RpoD (24) and R-347 in B. subtilis ςA (35, 36). (E) RsbX alignment. An RsbX homolog in S. aureus has not been identified (58).

B. subtilis residues previously shown to be important for the function of RsbV and RsbW (33) are also conserved in the predicted Listeria gene products (Fig. 2), providing further evidence of identification of the sigB operon in L. monocytogenes. For example, the conserved serine residue, which represents a phosphorylation site in RsbV, and the conserved amino acid residues, which are thought to be important for ATP binding in RsbW (and in histidine kinases), were conserved in the respective proteins among all sequenced Listeria strains.

Phylogenetic analysis of ςB and ςF.

Because of reported sequence heterogeneities in the stress-responsive RpoS protein of gram-negative organisms (31, 55), we investigated the phylogenetic diversity of ςB among Listeria strains. We PCR amplified and sequenced complete sigB ORFs from three L. monocytogenes strains, each representing one of three major genetic lineages (54), and from one L. innocua strain. In addition to L. monocytogenes 689426 (lineage III), we sequenced sigB from strains 2289 (lineage I) and 10403S (lineage II). Alignment of the three L. monocytogenes sequences revealed a total of 31 polymorphic nucleotide sites, but only one predicted a polymorphic amino acid (aa) site, located at aa 216. Residue 216 is a phenylalanine in strains 689426 and 2289 but a tyrosine in strain 10403S. The addition of the L. innocua sigB sequence to the L. monocytogenes alignments identified an additional 43 polymorphic nucleotide sites for a total of 74 among the four sequences. Comparison of L. innocua ςB with the predicted L. monocytogenes ςB sequences identified only two polymorphic amino acid residues (Fig. 2D) in addition to the presence of a tyrosine at aa 216, as found in L. monocytogenes 10403S.

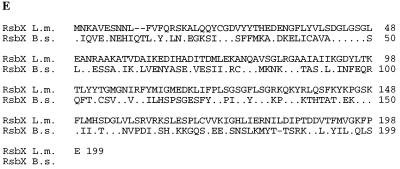

Previous reports (16, 17, 32, 44) and the results of our BLASTN analyses suggested phylogenetic relationships between sequences previously reported for ςB and ςF proteins. We probed these relationships by analyzing a multiple sequence alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences. This analysis revealed four ς factor clusters as follows: ςB from L. monocytogenes, B. subtilis, and S. aureus (cluster A); ςF from Streptomyces spp. (cluster B); putative ςF factors from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae (cluster C); and ςF from Bacillus spp. (cluster D). These clusters are displayed in a bootstrap tree in Fig. 3. Amino acid sequence identities among ςB proteins (cluster A) ranged from 58 to 66%; sequence identities within clusters B and D ranged from 46 to 85% and from 57 to 90%, respectively. In cluster C, M. tuberculosis and M. leprae had 62% predicted sigma factor amino acid identity. Amino acid identities among the four clusters ranged from 23 to 41%.

FIG. 3.

Unrooted bootstrap tree (100 replicates) for ςB and ςF sequences constructed by the neighbor joining method. The tree was constructed with the Seqboot, Protdist, Neighbor, Consensus, and Drawtree programs in the software package PHYLIP (22). The numbers at the nodes of the tree represent the bootstrap values for each node. Sequences used for this analysis include ςB from L. monocytogenes, B. subtilis (19) (GenBank accession no. M34995), and S. aureus (58) (GenBank accession no. Y09929) and ςF from Bacillus coagulans (42) (GenBank accession no. Z54161), Bacillus megaterium (49) (GenBank accession no. X63757), B. subtilis (60) (GenBank accession no. M15744), Bacillus stearothermophilus (43) (GenBank accession no. L47360), Bacillus licheniformis (61) (GenBank accession no. M25260), Bacillus sphaericus (43) (GenBank accession no. L47359), Paenibacillus polymyxa (43) (GenBank accession no. L47358), Streptomyces aureofaciens (44) (GenBank accession no. L09565), Streptomyces coelicolor (44) (GenBank accession no. L11648), Streptomyces setonii (34) (GenBank accession no. D17466), and M. leprae (GenBank accession no. U00012) and from two M. tuberculosis isolates (16) (GenBank accession no. U41641 and Z92771).

Characterization of an L. monocytogenes sigB null mutant.

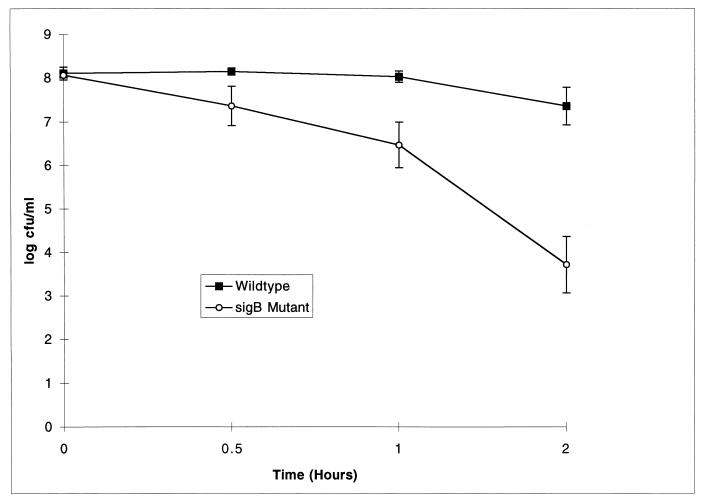

To evaluate the function of ςB in L. monocytogenes, we used allelic exchange mutagenesis to construct a nonpolar sigB mutant with an internal 99-aa deletion. Survival of L. monocytogenes ςB mutant stationary-phase cells exposed to pH 2.5 for 1 or 2 h was significantly reduced (P < 0.05; t test) compared with that of its isogenic parent (Fig. 4). Survival after 1 or 2 h was 1.6 or 3.6 logs lower, respectively, for the ςB mutant than for its isogenic parent.

FIG. 4.

Stationary-phase acid survival (pH 2.5) of L. monocytogenes. Values are the averages of two trials, each of which was performed in duplicate. Standard errors are given. The ςB mutant showed significantly decreased survival compared to its isogenic parent at 1 and 2 h (P < 0.05).

The sigB mutant was further characterized with mouse models of listeriosis by determining recovery rates of wild-type and mutant strains from livers and spleens following intragastric or intraperitoneal infection (Table 2). The sigB mutant was recovered at slightly lower levels from livers at day 4 for intragastric inoculation and at day 2 for intraperitoneal inoculation (P = 0.027 and 0.029, respectively). In general, however, mutant and wild-type strains showed similar recovery rates at 2 and 4 days postinoculation. One of the mice infected intraperitoneally with the wild-type strain showed liver abscesses by macroscopic evaluation at day 4. No liver abscesses were observed in the animals infected with the sigB mutant.

TABLE 2.

Recovery of L. monocytogenes 10403S and the isogenic sigB mutant from tissues of infected mice after intragastric or intraperitoneal infection

| Type of inoculation and tissue | Log10 no. of bacteria/g of tissue (± SD) at the following day postinfectiona:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2

|

4

|

|||

| 10403S | sigB mutant | 10403S | sigB mutant | |

| Intragastric | ||||

| Liver | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.7 (0.5)c | 2.9 (0.4)c |

| Spleen | 4.0 (1.0) | 4.1 (1.5) | 4.9 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.2) |

| Intraperitoneal | ||||

| Liver | 4.3 (0.5)b | 3.6 (0.3)b | 3.9 (1.5) | 4.3 (0.9) |

| Spleen | 5.1 (0.4) | 4.8 (0.4) | 5.0 (1.5) | 5.1 (0.5) |

Values are the averages of five inoculated animals, except for the intragastric-inoculation day-2 data, which represent the averages of four animals (one animal was excluded from each group because fewer bacteria than the detection limit [10 CFU/g for liver and <102 CFU/g for spleen] were recovered).

Bacterial numbers differ significantly at P = 0.029.

Bacterial numbers differ significantly at P = 0.027.

DISCUSSION

The following evidence supports our identification of sigB, the gene encoding ςB, in L. monocytogenes: (i) phylogenetic analyses of reported amino acid sequences for ςB and the closely related ςF proteins from various species grouped L. monocytogenes ςB in the same cluster with the ςB proteins from B. subtilis and S. aureus; (ii) B. subtilis residues previously shown to be important for the function of RsbV and RsbW (33) are also conserved in the predicted Listeria gene products (Fig. 2); (iii) the gene order in the 2,668-bp region of the L. monocytogenes sigB operon is rsbU-rsbV-rsbW-sigB-rsbX and is therefore identical to the order of the last five genes of the sigB operon in B. subtilis; and (iv) L. monocytogenes ςB mutant cells are more sensitive to acid exposure than wild-type cells. Because stress-responsive sigma factors have been shown to be important for virulence among gram-negative bacteria (14, 21, 55), we tested the possible contribution of ςB to L. monocytogenes virulence in a mouse model system. In mouse infection experiments, mutant and wild-type cells showed similar degrees of spreading to livers and spleens after either intragastric or intraperitoneal infection, although recovery of the mutant from livers was lower than that for the wild type at day 4 for intragastric inoculation and at day 2 for intraperitoneal infection (P = 0.027 and 0.029, respectively). Taken together, these findings suggest that ςB-dependent proteins contribute to acid resistance in L. monocytogenes but are not essential for spreading of the organism to livers and spleens at 2 and 4 days postinoculation in this mouse model.

L. monocytogenes sigB operon structure.

We have identified one partial and four complete ORFs in L. monocytogenes with significant predicted amino acid identities to RsbU, RsbV, RsbW, ςB, and RsbX in B. subtilis and RsbU, RsbV, RsbW, and ςB in S. aureus (Fig. 1). In B. subtilis, the sigB structural gene lies seventh in an operon which includes seven rsb genes, where rsb stands for regulator of ςB. The rsb products regulate ςB activity by means of coupled partner switching modules in response to signals of energy or environmental stress (1, 2, 6–8, 10, 12, 18, 33, 51, 56, 59). Each module is composed of three elements: a serine phosphatase (RsbU or RsbX), an antagonist protein (RsbS or RsbV), and a switch protein (RsbT or RsbW) (1, 33, 59). We speculate that the presence of RsbU and RsbX in L. monocytogenes predicts the existence of a dual-module ςB regulatory network similar to that of B. subtilis and thus also predicts the presence of the ςB regulatory proteins RsbR, RsbS, and RsbT in L. monocytogenes. In contrast, the gene order in the S. aureus sigB operon is rsbU-rsbV-rsbW-sigB, with an ORF (CTorf239) which shows no homology to rsbX immediately downstream of sigB (58). This finding suggests that the regulatory mechanisms controlling the activity of S. aureus ςB may lack the environmental stress-responsive regulatory module further composed of RsbR, RsbS, and RsbT and thus may differ from the ςB regulatory networks of B. subtilis and L. monocytogenes.

Phylogenetic analyses of ςB and ςF proteins.

Multiple alignments of predicted ςB and ςF amino acid sequences from Streptomyces spp., Mycobacterium spp., Bacillus spp., and L. monocytogenes clustered the products in a manner suggesting that ςB and ςF proteins sequenced to date represent four phylogenetically distinct ς factor groups with a possible common ancestor (Fig. 3). These results are also consistent with the hypothesis that ςB and ςF in the genus Bacillus may have arisen by tandem duplication from a common ancestor (32).

Alignment of the predicted ςB amino acid sequences from strains representing the three major genetic lineages of L. monocytogenes (54) and from an L. innocua strain identified 74 polymorphic nucleotide sites which predict only 3 polymorphic amino acid residues (Fig. 2D). This level of conservation is noteworthy in comparison with observed allelic variations in other well-characterized L. monocytogenes genes. To illustrate, 22 of 53 polymorphic nucleotides in a 539-bp fragment of the L. monocytogenes actA virulence gene are predicted to result in amino acid changes (54) and 2 of 12 polymorphic nucleotides in a 150-bp fragment of the hly virulence gene yield predicted amino acid changes (45, 46, 54). Our findings strongly suggest that functional constraints within Listeria spp. limit evolutionary alterations in the ςB protein.

Characterization of an L. monocytogenes ςB mutant.

Bacterial survival in the acidic environment of the stomach and in the vacuole of the macrophage is likely to be important for full virulence of an intracellular pathogen commonly transmitted by food, such as L. monocytogenes. We report a significant reduction in stationary-phase acid tolerance for our L. monocytogenes ςB mutant in comparison with its isogenic parent (Fig. 4). Our finding of increased acid sensitivity in the ςB mutant suggests that ςB-dependent proteins provide some protection to L. monocytogenes cells exposed to lethal acidic conditions. B. subtilis ςB mutant cells have been shown to be more sensitive than wild-type cells to oxidative stress, specifically exposure to cumene hydroperoxide and lethal doses of hydrogen peroxide (4, 20). Our demonstration of reduced tolerance to lethal acid stress for L. monocytogenes ςB mutant cells provides phenotypic evidence supporting the role of ςB-dependent proteins in response to conditions of environmental stress.

Based on the reduced acid resistance of the L. monocytogenes sigB mutant, we hypothesized that ςB might play a role in L. monocytogenes virulence. Specifically, we speculated that ςB may protect the organism from the acid stress encountered during stomach passage (∼2 hours at pH 2 to 3), which may enhance its survival and passage into the intestinal tract, the site of systemic invasion. Therefore, we evaluated the effects of loss of L. monocytogenes ςB function in mouse models of listeriosis.

Spreading of an L. monocytogenes sigB mutant to the liver 2 or 4 days after intragastric or intraperitoneal inoculation was only minimally impaired in comparison with that of its isogenic parent. The sigB mutant was recovered at slightly lower levels from livers 4 days after intragastric inoculation and 2 days after intraperitoneal inoculation (P = 0.027 and 0.029, respectively). These findings suggest that loss of ςB function has only minimal effects on the early spread of L. monocytogenes in this mouse virulence assay. Our findings contrast with results obtained with the gram-negative enteric pathogen S. typhimurium, in which the general stress ς factor RpoS (38) is essential for full virulence (21, 55). While our results with the mouse model appear to rule out a significant contribution of L. monocytogenes ςB to intracellular survival and spread, they do not rule out a contribution to the infection process. For example, it is possible that direct intragastric inoculation alters the stomach passage time normally encountered by ingested materials. If this proves to be the case, then our results do not rule out a direct contribution of ςB to pathogenesis in food-borne infections. Furthermore, the experiments that we report do not fully address the role of L. monocytogenes ςB in surviving environmental stress. Because loss of ςB function leads to decreased resistance to acid stress, we consider it likely that loss of ςB function will also lead to decreased resistance to other environmental stresses. Such environmental stress resistance may contribute to survival in foods and therefore indirectly to pathogenicity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank B. Miller for helpful discussions and assistance with primer design, D. Portnoy for providing plasmid pKSV7, and S. Dineen for help with the mouse virulence studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akbar S, Kang C M, Gaidenko T A, Price C W. Modulator protein RsbR regulates environmental signaling in the general stress pathway of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:567–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3631732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alper S, Duncan L, Losick R. An adenosine nucleotide switch controlling the activity of a cell type-specific transcription factor in B. subtilis. Cell. 1994;77:195–205. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antelmann H, Engelmann S, Schmid R, Hecker M. General and oxidative stress responses in Bacillus subtilis: cloning, expression, and mutation of the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase operon. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6571–6578. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6571-6578.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbour A H, Rampling A, Hormaeche C E. Comparison of the infectivity of isolates of Listeria monocytogenes following intragastric and intravenous inoculation in mice. Microb Pathog. 1996;20:247–253. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson A K, Haldenwang W G. Characterization of a regulatory network that controls ςB expression in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:749–757. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.749-757.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benson A K, Haldenwang W G. Bacillus subtilis ςB is regulated by a binding protein (RsbW) that blocks its association with core RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2330–2334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson A K, Haldenwang W G. The ςB-dependent promoter of the Bacillus subtilis sigB operon is induced by heat shock. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1929–1935. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.1929-1935.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Binnie C, Lampe M, Losick R. Gene encoding the ς37 species of RNA polymerase factor from Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5943–5947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boylan S A, Redfield A R, Brody M S, Price C W. Stress-induced activation of the ςB transcription factor of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7931–7937. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7931-7937.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boylan S A, Redfield A R, Price C W. Transcription factor ςB of Bacillus subtilis controls a large stationary-phase regulon. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3957–3963. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.3957-3963.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boylan S A, Rutherford A, Thomas S M, Price C W. Activation of Bacillus subtilis transcription factor ςB by a regulatory pathway responsive to stationary-phase signals. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3695–3706. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3695-3706.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camilli A, Portnoy D A, Youngman P. Insertional mutagenesis of Listeria monocytogenes with a novel Tn917 derivative that allows direct cloning of DNA flanking transposon insertions. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3738–3744. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3738-3744.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen C-Y, Buchmeier N A, Libby S, Fang F C, Krause M, Guiney D G. Central regulatory role for the RpoS sigma factor in expression of Salmonella dublin plasmid virulence genes. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5303–5309. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.18.5303-5309.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniels D, Zuber P, Losick R. Two amino acids in an RNA polymerase ς factor involved in the recognition of adjacent base pairs in the −10 region of a cognate promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8075–8079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.8075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeMaio J, Zhang Y, Ko C, Young D B, Bishai W R. A stationary-phase stress-response sigma factor from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2790–2794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diederich B, Wilkinson J F, Magnin T, Najafi S M A, Errington J, Yudkin M D. Role of the interactions between SpoIIAA and SpoIIAB in regulating cell-specific transcription factor ςF of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2653–2663. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dufour A, Haldenwang W G. Interactions between a Bacillus subtilis anti-ς factor (RsbW) and its antagonist (RsbV) J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1813–1820. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1813-1820.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duncan M L, Kalman S S, Thomas S M, Price C W. Gene encoding the 37,000-dalton minor sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase: isolation, nucleotide sequence, chromosomal locus, and cryptic function. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:771–778. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.771-778.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelmann S, Hecker M. Impaired oxidative stress resistance of Bacillus subtilis sigB mutants and the role of katA and katE. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:63–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang F C, Libby S J, Buchmeier N A, Loewen P C, Switala J, Harwood J, Guiney D G. The alternative ς factor KatF (RpoS) regulates Salmonella virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11978–11982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP-Phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flamm R K, Hinrichs D J, Tomashow M F. Introduction of pAMβ1 into Listeria monocytogenes by conjugation and homology between native L. monocytogenes plasmids. Infect Immun. 1984;44:157–161. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.1.157-161.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardella T, Moyle H, Susskind M M. A mutant Escherichia coli ς70 subunit of RNA polymerase with altered promoter specificity. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:579–590. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haldenwang W G. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:1–30. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.1-30.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haldenwang W G, Losick R. Novel RNA polymerase ς factor from Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7000–7004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helmann J D, Chamberlin M J. Structure and function of bacterial sigma factors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:839–872. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horton R M, Cai Z, Ho S N, Pease L R. Gene splicing by overlap extension: tailor-made genes using the polymerase chain reaction. BioTechniques. 1990;8:528–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Igo M, Lampe M, Ray C, Schafer W, Moran C P, Jr, Losick R. Genetic studies of a secondary RNA polymerase sigma factor in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3464–3469. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3464-3469.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iriarte M, Stainier I, Cornelis G R. The rpoS gene from Yersinia enterocolitica and its influence on expression of virulence factors. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1840–1847. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1840-1847.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jishage M, Ishihama A. Variation in RNA polymerase sigma subunit composition within different stocks of Escherichia coli W3110. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:959–963. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.959-963.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalman S, Duncan M L, Thomas S M, Price C W. Similar organization of the sigB and spoIIA operons encoding alternate sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5575–5585. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5575-5585.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang C M, Brody M S, Akbar S, Yang X, Price C W. Homologous pairs of regulatory proteins control activity of Bacillus subtilis transcription factor ςB in response to environmental stress. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3846–3853. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3846-3853.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kato F, Hino T, Nakaji A, Tanaka M, Koyama Y. Carotenoid synthesis in Streptomyces setonii ISP5395 is induced by the gene crtS, whose product is similar to a sigma factor. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;247:387–390. doi: 10.1007/BF00293207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kenney T J, Moran C P., Jr Genetic evidence for interaction of ςA with two promoters in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3282–3290. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3282-3290.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kenney T J, York K, Youngman P, Moran C P., Jr Genetic evidence that RNA polymerase associated with ςA factor uses a sporulation specific promoter in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9109–9113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lingnau A, Domann E, Hudel M, Bock M, Nichterlein T, Wehland J, Chakraborty T. Expression of the Listeria monocytogenes EGD inlA and inlB genes, whose products mediate bacterial entry into tissue culture cell lines, by PrfA-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3896–3903. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3896-3903.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loewen P C, Hengge-Aronis R. The role of sigma factor ςS (katF) in bacterial global regulation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:53–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lonetto M, Gribskov M, Gross C A. The ς70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3843–3849. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3843-3849.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lonetto M A, Brown K L, Rudd K E, Buttner M J. Analysis of the Streptomyces coelicolor sigE gene reveals the existence of a subfamily of eubacterial RNA polymerase ς factors involved in the regulation of extracytoplasmic functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7573–7577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Losick R, Stragier P. Crisscross regulation of cell-type-specific gene expression during development in B. subtilis. Nature. 1992;355:601–604. doi: 10.1038/355601a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park S G, Yudkin M D. Nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus coagulans homologue of the spoIIA operon of Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1996;177:275–276. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00306-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park S G, Yudkin M D. Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of the spoIIA operon from diverse Bacillus and Paenibacillus species. Gene. 1997;194:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Potuckova L, Kelemen G H, Findlay K C, Lonetto M A, Buttner M J, Kormanec J. A new RNA polymerase sigma factor, sigma F, is required for the late stages of morphological differentiation in Streptomyces spp. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:37–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17010037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rasmussen O F, Beck T, Olsen J E, Dons L, Rossen L. Listeria monocytogenes isolates can be classified into two major types according to the sequence of the listeriolysin gene. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3945–3951. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3945-3951.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rasmussen O F, Skouboe P, Dons L, Rossen L, Olsen J E. Listeria monocytogenes exists in at least three evolutionary lines: evidence from flagellin, invasive associated protein and listeriolysin O genes. Microbiology. 1995;141:2053–2061. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-9-2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roux K H. Optimization and troubleshooting in PCR. In: Dieffenbach C W, Dveksler G S, editors. PCR primer: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siegele D A, Hu J C, Walter W A, Gross C A. Altered promoter recognition by mutant forms of the ς70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:591–603. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tao Y P, Hudspeth D S, Vary P S. Cloning and sequencing of the Bacillus megaterium spoIIA operon. Biochimie. 1992;74:695–704. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(92)90142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tatti K M, Jones C H, Moran C P., Jr Genetic evidence for interaction of ςE with the spoIIID promoter in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7828–7833. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.24.7828-7833.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Voelker U, Dufour A, Haldenwang W G. The Bacillus subtilis rsbU gene product is necessary for RsbX-dependent regulation of ςB. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:114–122. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.114-122.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Völker U, Engelmann S, Maul B, Riethdorf S, Völker A, Schmid R, Mach H, Hecker M. Analysis of the induction of general stress proteins of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1994;140:741–752. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-4-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waldburger C, Gardella T, Wong R, Susskind M M. Changes in conserved region 2 of Escherichia coli ς70 affecting promoter recognition. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:267–276. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiedmann M, Bruce J L, Keating C, Johnson A E, McDonough P L, Batt C A. Ribotypes and virulence gene polymorphisms suggest three distinct Listeria monocytogenes lineages with differences in pathogenic potential. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2707–2716. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2707-2716.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilmes-Riesenberg M R, Foster J W, Curtiss R., III An altered rpoS allele contributes to the avirulence of Salmonella typhimurium LT2. Infect Immun. 1997;65:203–210. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.203-210.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wise A A, Price C W. Four additional genes in the sigB operon of Bacillus subtilis that control activity of the general stress factor ςB in response to environmental signals. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:123–133. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.123-133.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu Q-L, Kong D, Lam K, Husson R N. A mycobacterial extracytoplasmic function sigma factor involved in survival following stress. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2922–2929. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2922-2929.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu S, de Lencastre H, Tomasz A. Sigma-B, a putative operon encoding alternate sigma factor of Staphylococcus aureus RNA polymerase: molecular cloning and DNA sequencing. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6036–6042. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.6036-6042.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang X, Kang C M, Brody M S, Price C W. Opposing pairs of serine protein kinases and phosphatases transmit signals of environmental stress to activate a bacterial transcription factor. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2265–2275. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yudkin M D. Structure and function in a Bacillus subtilis sporulation-specific sigma factor: molecular nature of mutations in spoIIAC. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:475–481. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-3-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yudkin M D, Appleby L, Smith A J. Nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus licheniformis homologue of the sporulation locus spoIIA of Bacillus subtilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:767–775. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-4-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou Y-N, Kusukawa N, Erickson J W, Gross C A, Yura T. Isolation and characterization of Escherichia coli mutants that lack the heat shock sigma factor ς32. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3640–3649. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3640-3649.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zuber P, Healy J, Carter III H L, Cutting S, Moran C P, Jr, Losick R. Mutation changing the specificity of an RNA polymerase sigma factor. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:605–614. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]