Abstract

Breast cancer is one of the most common and deadly cancers worldwide. Approximately, 20% of all breast cancers are characterized as triple negative (TNBC). TNBC typically is associated with a poorer prognosis relative to other breast cancer subtypes. Due to its aggressiveness and lack of response to hormonal therapy, conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy is the usual treatment; however, this treatment is not always effective, and an important percentage of patients develop recurrence. More recently, immunotherapy has started to be used on some populations with TNBC showing promising results. Unfortunately, immunotherapy is only applicable to a minority of patients and responses in metastatic TNBC have overall been modest in comparison to other cancer types. This situation evidences the need for developing effective biomarkers that help to stratify and personalize patient management. Thanks to recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI), there has been an increasing interest in its use for medical applications aiming at supporting clinical decision making. Several works have used AI in combination with diagnostic medical imaging, more specifically radiology and digitized histopathological tissue samples, aiming to extract disease-specific information that is difficult to quantify by the human eye. These works have demonstrated that analysis of such images in the context of TNBC has great potential for 1) risk-stratifying patients to identify those patients who are more likely to experience disease recurrence or die from the disease and 2) predicting pathologic complete response. In this manuscript, we present an overview on AI and its integration with radiology and histopathological images for developing prognostic and predictive approaches for TNBC. We present state of the art approaches in the literature and discuss the opportunities and challenges with developing AI algorithms regarding further development and clinical deployment, including identifying those patients who may benefit from certain treatments (e.g., adjuvant chemotherapy) from those who may not and thereby should be directed toward other therapies, discovering potential differences between populations, and identifying disease subtypes.

Keywords: triple negative breast cancer, Predictive Biomarkers, Prognostic Biomarkers, Computational Pathology, radiomics, Deep learning

1. Introduction

Except for skin cancer, breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, comprising more than 10% of all new cancers globally. It is the fifth leading cause of cancer death worldwide, accounting for an estimated 700,000 deaths. In 2022, approximately 300,000 new cases were expected to be diagnosed in US women. Recent data showed that (as of January 1st, 2022) over 4 million women in the United States had a history of this disease and about a third of newly diagnosed malignancies in women are predicted to be breast cancer (1,2).

Breast cancer is divided into different subtypes based on, amongst others, a molecular profile established by the varying expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (3,4). When a breast carcinoma lacks all these receptors, it is called triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). TNBC accounts for about 20% of all breast cancers (5), and, unlike the other types, it tends to grow and spread faster, has a worse prognosis, and fewer treatment options due to its lack of response to hormone therapy or targeted HER2 drugs (4,6). Recurrences in TNBC patients are well documented with a detailed study of cases indicating elevated chance of distant metastases and death within 5 years of diagnosis (7). Additionally, TNBC patients have a higher mortality rate compared to other subtypes, and the median time to death is around 4 years versus 6 years for non-TNBC patients (7). Due to its aggressiveness and lack of response to hormonal therapy, the treatment of patients with TNBC represents a challenge (8). Although there are genomic assays such as the Oncotype DX (21 genes) or Mammaprint (70 genes) that help guiding the treatment of some breast cancer types (e.g., hormone receptor (HR)-positive and HER2-negative), those are not recommended for TNBC (9).

Given the lack of known targetable biomarkers, conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy has been the usual treatment for patients with TNBC in both early and advanced stages of the disease (8,10). Interestingly, patients with TNBC have a higher response to chemotherapy than patients with other breast cancer types (10,11); however, the treatment is not fully effective for all patients, especially for those with metastatic TNBC, who will inevitably die of the disease (10,11). In recent years, there has been a growing interest in developing innovative, multi-drug combination systemic therapies in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings aiming to improve current treatment outcomes (11,12). However, some studies remain controversial because of the added toxicities (e.g., platinum agents) and others are still in initial phases and require more extensive validation in independent series of patients (10). While chemotherapy has been the standard of care for TNBC, over the past decade, substantial advances in cancer immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have changed therapeutic strategies for advanced cancer (13). Recent clinical trials have shown promising pathologic complete response (pCR) rates of up to 90% for TNBC patients treated with ICI (11). Unfortunately, responses to immunotherapy in metastatic TNBC have been modest in comparison to other cancer types and applicable only to a minority of patients (8). Patient selection is, therefore, critical to identify patients with TNBC who will benefit from certain therapies, so those who are unlikely to respond can be spared the associated toxicities and directed toward other therapies (8).

Another important concern in the space of TNBC is that different studies have shown that this disease disproportionately affects Black (or African American) women (14-18). While the incidence of breast cancer is lower in Black women than in White women, disease specific mortality rate is twice in Black women. Black women with TNBC had a 21% higher risk of mortality than White women even after adjustment for treatment related factors. Similarly, they had lower pCR to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) compared to White women, indicating that Black patients may be more resistant to chemotherapy. A reason for this may be differential access to health and social inequity; however, another plausible reason is the presence of morphologic and molecular differences in the disease phenotype (15). For example, a study by Hoskin et al. (19) demonstrated that tissue-based genomic assays such as OncotypeDx may be less accurate in underserved populations like Black women. This therefore raises the question of how to incorporate these population specific differences in developing new companion diagnostic tools for managing treatment strategies for TNBC patients.

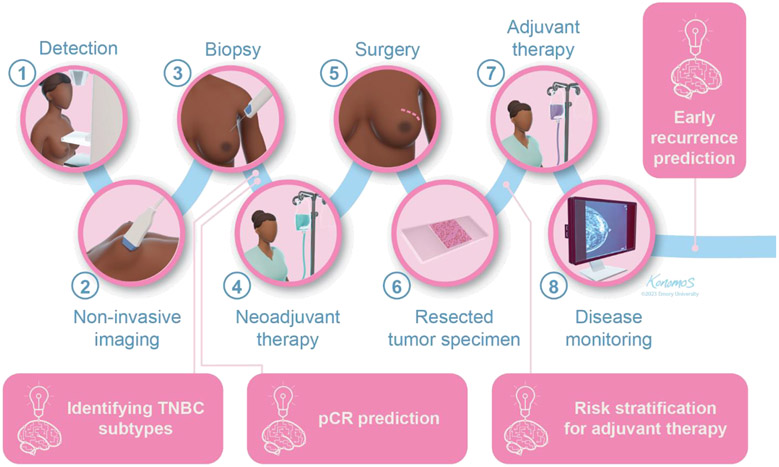

The problematic situation of TNBC has exhibited the need for developing effective predictive and prognostic biomarkers that help to stratify and personalize patient management (8,9,11). Traditionally, radiological scans and histopathological tissue samples have been used by physicians to diagnose and guide the treatment of patients with TNBC (Figure 1); however, these images and samples possess disease-specific information that may not be easily perceived by the human eye and thereby may be unexploited (20,21). Thanks to advances in computational power and the development of new techniques, there has been an increasing interest in the use of artificial intelligence (AI) for medical applications aiming at supporting clinical decision making (20). In recent years, AI and deep learning have been used in combination with medical imaging and have facilitated the development of radiomics (based on radiological scans) and computational pathology (based on histopathological samples), approaches that use computational tools for extracting quantitative information and complex patterns that are difficult to capture by physicians (20,21). The information extracted by such approaches has shown great potential for tasks such as 1) risk-stratifying patients to identify those who are more likely to experience disease recurrence or die from the disease and 2) predicting pathologic complete response. In this manuscript, we start by presenting an overview on AI, deep learning, radiomics, and computational pathology-based approaches. Next, we review some relevant AI-based prognostic and predictive biomarkers developed for TNBC employing radiomics and computational pathology approaches. Lastly, we address the possibilities and obstacles in the advancement and clinical application of AI algorithms. This includes the differentiation of patients who could potentially benefit from specific treatments like chemotherapy or immunotherapy, guiding them towards suitable therapies while identifying others who may not benefit. Additionally, we discuss published work that explores the potential to uncover variances between populations and identify distinct subtypes of the disease.

Figure 1.

General pipeline for TNBC and opportunity areas for AI-based imaging biomarkers. Radiological scans and histopathological tissue samples are usually employed for diagnostic purposes and for guiding the treatment. The integration with AI has the potential to provide complementary information for a more tailored treatment by predicting pathologic complete response (pCR), risk-stratifying patients, and predicting early recurrence.

2. Artificial intelligence and imaging biomarkers

Artificial intelligence and deep learning

AI is a branch of computer science in which a computer is used to solve complex problems emulating what an intelligent human would do in the same situation (22). Thanks to the development of AI and machine learning techniques in the past decade, multiple “intelligent” models are playing important roles in daily life and have transformed various industries through their superior performance and efficiency in prediction tasks (23). There are two common approaches to extract feature representations for building AI models (24): The first is usually known as hand crafted feature extraction, and it uses exiting domain knowledge to identify characteristics that are potentially useful for the computer to solve a task. The second is usually known as unsupervised feature learning, and it allows the computer to learn the characteristics that are relevant for solving a problem automatically.

One popular example of this unsupervised feature learning approach is deep learning, a class of machine learning technique that attempts to learn by example using artificial neural networks (abstract representations of the human neural architecture) with multiple layers (25). Given a data set, a deep-learning algorithm discovers representations that distinguish between categories of interest automatically. Convolutional neural networks (CNN) are a specialized form of artificial neural networks adapted for processing images. Thanks to recent advancements of computational capacities and resources, CNN have earned a lot of recognition and have shown great power in tackling various computer vision tasks such as image classification, segmentation, and object detection (23). Some popular CNN architectures include LeNet5, AlexNet, VGG, InceptionNet, ResNet, and U-Net. Generative adversarial networks (GAN) are another type of neural network that consists of two networks that are trained at the same time: the generator and the discriminator. The generator is trained to create fake images trying to fool the discriminator while the discriminator attempts to distinguish between real and generated fake images. GANs have been useful for tasks such as style transfer and object segmentation (23).

Radiomics

In the past years, there has been a constant increase in digitization of information generated during clinical workflow (20), including radiological images (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], computerized tomography [CT], positron emission tomography, or echography). Radiomics is an approach that aims to extract quantitative information from radiological diagnostic images that are not easily perceived by the human eye (20,21). Thus, images are transformed into high-dimensional and reproducible data that can be used for different purposes, for example, capturing tissue and lesion properties such as shape and heterogeneity (21). Interestingly, radiomic data are mineable, which means that, in sufficiently large datasets, they can be used to discover previously unknown patterns useful not only for diagnostic purposes but also for developing prognostic and predictive biomarkers (21,26-28).

Computational pathology

In the last decade, the advancement and application of whole slide imaging technology has enabled the development of digital pathology. Digital pathology is an approach that involves the digital acquisition of high-resolution images representing entire stained tissue sections from glass slides in a format that allows them to be viewed by a pathologist on a computer monitor (29). In turn, digital pathology has facilitated the expansion of computational pathology that consists of the use of AI tools to extract quantitative information from histopathological samples (e.g., hematoxylin & eosin [H&E]-stained tissue slides and special stains such as immunohistochemistry [IHC] or immunofluorescence). Similar to radiomics, computational pathology has the premise that biomedical images contain data of disease-specific processes that are difficult to quantify by the human eye and that can be captured by a combination of computational techniques (20).

3. AI-based imaging biomarkers in TNBC

3.1. Machine Learning based prognostication in TNBC

Different works have used multiple perspectives for the development of imaging-based prognostic biomarkers that exploit visual information from either radiological or histopathological images aiming to identify those who are at a higher risk to experience disease recurrence or death (Table 1).

Table 1.

Publications regarding AI-based imaging biomarkers for TNBC.

| Biomarker type/ Modality |

Biomarker | Method(s) | Result(s) | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prognostic/Computational Pathology | Quantification of TILs: Deep learning-based computational TIL assessment | Analysis of TIL densities in tumor and microenvironment (n=94) using CD3, CD8 and FOXP3 markers. | Improved survival outcomes linked to the presence of a high density of TILs. | Balkenhol et al. (38) |

| Stromal TIL assessment and prognosis evaluation on Asian (n=184) and Caucasian cohort (n= 117). | Tool to assess stromal TILs and prognosis. | Sun et al. (39) | ||

| Prognostic/Computational Pathology | Quantification of TILs: AI enabled software | Association between TILs, PD-L1, CD8 and FOXP3(n=244). | Increased PD-L1 expression on residual disease after NACT | Dieci et al. (41) |

| Hotspot evaluation (n=66) based on CD8+ TIL enumeration using digital image analysis. | Highly reproducible method to quantify CD8+ TILs, hotspots may reduce TIL count variations due to heterogeneity. | McIntire et al. (42) | ||

| Unsupervised nuclei segmentation followed by ML- based cell classification to quantify TILs (n=920) based on variables such as proportion of TILs in relation to whole tumor cell count, and to the area of intra-tumoral stromal regions. | Significant prognostic relevance with outcomes (p ≤ 0.01) was found for five TIL variables, which were determined by a cell classifier guided by neural networks. | Bai et al. (43) | ||

| Prognostic/Computational Pathology | TIL Spatial architecture | Extraction of morphological features (n=5, wsi = 1000, n=92) that capture inter- and intra-tumoral heterogeneity | Role of invasive front in tumor immune architecture; Spatial TILs indicated patient outcomes; Proved to be more prognostic than TIL density alone. | Mi et al. (44), Lu et al. (46), Corredor et al. (48) |

| Correlation of morphological features with gene expression profiles (n=187) | Four morphological traits distinguished survival results. Gene clusters linked to these features predicted patient survival in various gene expression databases. | Wang et al. (56) | ||

| Distance between TILs and individual and cluster of cancer cells (n=181) | The method shows positive correlation with multiple gene expression indicators associated with immune infiltration. | Yuan et al. (45) | ||

| Prognostic/Computational Pathology | Unsupervised feature extraction | Patient risk stratification based on immunofluorescence images of CD8+ T lymphocytes (n=55) | Estimated the risk of TNBC relapse over a 3-year span with an accuracy rate of 0.86. | Yu et al. (49) |

| Prognostic/Radiomics | Vascular characteristics of the tumor | Rim enhancement from DCE-MRI and its association with long-term patient outcome (n=65, n=194, n=281) | Recurrence was lower in non-rim-enhancing tumors compared to rim-enhancing tumors (p = 0.001); a spiculated margin may predict favorable prognosis; | Schmitz et al. (60), Lee et al. (62), Lee et al.(64) |

| Prognostic/Radiomics | Radiomic Nomograms for prognosticati on of patients based on textural features | Integration of clinical factors and radiomics features (intra- and peritumoral ultrasound features) from ultrasound images (n=486, n=426, n=200, n=150). Mammography-derived textural features such as the grey-level co-occurrence matrix, the neighborhood grey-level different matrix, the grey-level run length matrix, and the grey-level zone length matrix are prominent characteristics contributing to prognostic information. | Ultrasound-based radiomics features stratified patients and provided individual relapse risk accurately; Nomogram may be employed as a reliable tool to predict axillary lymph node (ALN) metastasis; The mammography-based nomogram in conjunction with clinical factors predicted DFS (C-index of 0.873 (95% CI: 0.758–0.989) in patients with early-stage TNBCs; MRI features-based nomograms stratified patients (p<0.001) predicted DFS. | Yu et al. (63), Yu et al. (67), Jiang et al. (66), Xia et al. (70) |

| Prognostic/Radiomics | Peritumoral heterogeneity | Multi-omics dataset (Radiomics n = 860 and radio-genomics n = 202) to distinguish molecular subtypes and identify prognostic markers. | Identified a peritumoral heterogeneity-based prognostic feature PeriVDN and its clinicopathological associations. | Jiang et al. (71) |

| Prognostic/Radiomics | Non-invasive assessment of TILs | Radiomic features extracted from mammographic and MRI data (n=129 and n=43) | Predicted TILs status with AUC of 0.790, 95% CI 0.638–0.943 for MRI based model and the low and high TIL groups were statistically different using the mammographic features (p<0.05). | Su et al. (72). Yu et al. (73) |

| Predictive/Computational Pathology | Deep neural networks to predict response to NACT | Automated tumor detection and nuclear segmentation (n=58) to extract nuclear count, area, circularity, and image-based first- and second-order features. | Tumor multicentricity (p=0.012), nuclear intensity (p=0.018), and texture features (p=0.043) were independently associated with achieving pCR. | Dodington et al. (77) |

| Combination of H&E and immunohistochemical biomarkers Ki67 and PHH3 (n=73) using spatial attention mechanism to predict response | Achieved 0.93 accuracy for pCR prediction, includes complementary tissue phenotype and molecular information to improve prediction. | Duanmu et al. (78) | ||

| Predictive/Radiomics | Radiomic prediction model derived from pre and post NACT MR sequences | Radiomic feature models built on pre-NACT, post-NACT and a combination of pre and post NACT MRI scans (n=147) | Models pre-, post, and combined yielded AUCs of 0.814, 0.802, and 0.933 in the testing set, respectively, to predict recurrence. | Ma et al. (80) |

| Longitudinal MRI-based fusion model to predict pCR | Ensemble learning models using longitudinal multiparametric MRI (n = 50) to predict pCR | The study focused on all subtypes of breast cancer. Though the AUC of TNBC was the least among the subtypes, the performance was comparable when validated on 3 external datasets. | Huang et al. (81) | |

| Predictive/Radiomics | Bio-radiomic model combining radiomic and histopathologic data | Pretreatment MRI radiomic features and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytic-based model to predict response to NACT (n=80) | Combined radiomic and pathology model performed best with an AUC of 0.75 when compared against 0.63 (pathology) and 0.71 (radiomics). | Jimenez et al. (84) |

| Predictive/Radiomics | 3D tumor segmentation and radiomics feature extraction | Assessment of Morphological features such as tumor volume, longest axial and volumetric diameters, and sphericity (n = 74) | TNBC tumors with pCR exhibited a markedly heightened minimum signal intensity (p = 0.004) and a diminished standard deviation of intensity when compared to tumors with no pCR (p<0.001). | Choudhery et al. (85) |

Biomarkers based on computational pathology

Cancer progression is a complex process that relies on the interplay between cells in the tumor, the microenvironment, and the immune system, which can act both to promote and suppress tumor growth and invasion (30). This has motivated the search for biomarkers that reflect the immune state and predict the likelihood of response to therapy (8). Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) comprise a mixture of immune cell types (cytotoxic T cells, natural killer cells, dendritic cells, helper T cells, B cells, and regulatory T cells) that are considered a marker of the adaptive component of the immune response and may indicate immune-mediated host defense against the tumor (8,31). Interestingly, higher levels of TILs are usually observed in TNBC and HER2-positive breast cancer in comparison to other breast cancers such as hormone receptors positive (8,30,32,33). Clinical trials and retrospective analyses suggest that TILs act as synergic agents given their association with improved disease-free and overall survival in TNBC patients treated with adjuvant anthracycline-based chemotherapy, pembrolizumab, or other neoadjuvant agents (30,34-36).

Assessment of lymphocytic infiltration is currently carried out by means of visual inspection, and there are guidelines to help pathologists to perform an adequate quantification (37); however, this process is time-consuming, costly, subjective, and error prone. For this reason, different studies (38-43) have used computerized tools to get an objective quantification of TILs in histopathology samples of patients with TNBC. In these works, authors have collected samples that have been stained using H&E and/or IHC (e.g., CD3, CD4, CD8, CD20, or FOXP3) and have automatically segmented tissue compartments (e.g., tumor and stroma) and identified TILs and other cells by means of either in-house developed machine learning models (deep neural networks) (38,39) or AI-enabled software tools (e.g., QuPath, Visiopharm, or HALO)(41-43). They were then able to extract different TIL-related quantitative measures; for example, total number of TILs, number of stromal TILs, proportion of TILs over tumor cells, abundance of CD8-positive cells, among others. In consistency with previous works, these studies have found that the presence of a high density of TILs is correlated with improved survival, demonstrating the potential of computational tools for an automated quantification.

Noteworthy, tumors and their environments are spatially organized ecosystems comprised of distinct cell types, which can assume a variety of phenotypes defined by co-expression of multiple proteins (30), suggesting that interrogation of tumor biology and response to treatment should take into consideration spatial information. Some studies have attempted to go beyond density measures by performing a spatial characterization of TILs in TNBC. For example, using IHC samples, Mi et al. (44) applied automatic tools on IHC samples to build cell groups within tissue regions (invasive front, central tumor, and normal tissue) and then extracted morphometric features from such groups. They found that the invasive front tends to have higher densities of immune cells, thereby highlighting the importance of this region in the tumor immune architecture. Yuan (45) used an automated image analysis tool to detect and classify cells in H&E samples. A quantitative measure of intratumor lymphocyte ratio was then computed based on the distances between TILs and 1) individual cancerous cells and 2) clusters of cancer cells (See Figure 2e). Such a measure was found to be significantly associated with disease-specific survival in TNBC. Similarly, Lu et al. (46) used deep learning to build TIL maps on H&E samples of patients with TNBC as well as other breast cancer types. They extracted TIL spatial features from such maps and computed a TIL score, which was associated with patient outcomes. Finally, it is known that TNBC patients with residual invasive disease have poorer prognosis compared to ER-positive patients with residual invasive disease (47). In a preliminary study, Corredor et al. (48) developed an AI-based-model that characterizes the spatial architecture of TILs in residual TNBC after NACT using H&E samples. This model builds clusters of TILs and non-TILs and extracts features from those clusters that are then used to identify patients who are at higher risk of death and recurrence. Although these works have highlighted the importance of analyzing spatial organization of the tumor as opposed to analyzing individual cells, an important limitation is the relatively small sample sizes that were employed. More experimentation is thereby required to determine whether these approaches are able to generalize to real-world scenarios.

Figure 2.

Examples of radiomic and computational pathology approaches using imaging-based predictive and prognostic biomarkers; (a) Tumor segmentation and 3D volumetric reconstruction of whole tumor and peritumoral ring (68) (b) Depiction of mammographic radiomic features and the level of TILs with mass density color overlay showing uneven, smooth mass (top pane in b) and uniform, unsmooth mass (bottom pane in b) (73) ; (c) Breast CE-MRI scans with prognostic radiomic feature Peri_V_DN (71) ; (d) Invasive ductal carcinoma with epithelium (red), stroma (green) and fat (white) cells (54); (e) Intratumor heterogeneity of cancer cell and lymphocyte distributions where the height of the hills represents the density of cells (45); (f) H&E, IF image (shown with higher magnification), and heat map based on density of CD3+ lymphocytes (38).

While most of the studies have used AI for identifying TILs (and other nucleated cells) and then extracting information from them (e.g., density or spatial), others have opted for an unsupervised feature learning approach in which the system automatically learns and selects appropriate features from the image while maximizing class separability. For example, Yu et al. (49) developed a deep learning model that receives as input immunofluorescence images of CD8+ T lymphocytes, and then it predicts whether a patient with TNBC is expected to have a good or poor outcome. While hand crafted approaches (e.g., those extracting metrics from TILs) are relatively easy to interpret as each feature can be analyzed independently, deep learning models are often referred to as "black boxes" because they are difficult to interpret (50). For this reason, authors using deep learning approaches are encouraged to use techniques that enable a deeper understanding of why a particular prediction was made. Grad-CAM (50), for example, is an approach that highlights regions of an input image that are most relevant to the model's decision, enabling users to gain insights into the model's reasoning.

In addition to TILs, high rates of PD-L1 expression have been reported in TNBC (8). Unfortunately, there is a lack of consensus on how to deliver PD-L1 as a clinical biomarker, thereby evidencing the need of objective, reproducible, and accurate approaches for quantifying PD-L1 expression (51). Aiming to address such an issue, Humphries et al. (51) used QuPath (52), an open-source digital image analysis software platform, for automatic quantification of PD-L1 in IHC samples and found that a high PD-L1 expression is associated with improved clinical outcome in TNBC in the context of standard of care chemotherapy. Similarly, Keren et al. (30) used multiplexed ion beam imaging by time-of-flight (MIBI-TOF) to quantify in situ expression of different proteins in TNBC patients, including tumor and immune antigens and immunoregulatory proteins. They developed a deep-learning-based pipeline for processing, segmentation, and quantification of cell types, and they concluded that expression of PD-L1 by distinct cells relate to tumor histology and survival. Finally, Wang et al. (53) used QuPath for analyzing multiplexed immunofluorescence TNBC samples and found that a high number of CD68+PD-L1+ macrophages were associated with improved prognosis of overall survival in patients receiving chemotherapy, improving incrementally upon the predictive value of PD-L1+ alone for breast cancer specific survival.

Tumor and stroma play an important role in the growth and spread of solid tumors and their response to therapy (54). For this reason, different works have used either histopathological analysis or radiomics to extract tumor-related visual information that can be useful for risk-stratifying patients. Previous work (54,55) has shown that there is a correlation between tumor stroma-ratio and patient prognosis in different breast cancer types, including TNBC. On this basis, Millar et al. (54) used QuPath to train a model able to segment tumor epithelium and stroma in H&E tissue micro arrays (TMAs) of patients with triple negative and luminal breast cancer (See Figure 2d). The tumor-stroma ratio was then calculated by dividing the epithelial area by the stromal area. Authors found that, for TNBC, low ratio (i.e., high stroma) was associated with poor prognosis. An important consideration is that TMAs only include small tissue cores from different samples, so important spatial and architectural information can be missed. Whole slide images are preferred as they capture the entire tissue section and provide a more comprehensive representation of the sample.

Aiming to exploit tumor morphological information, Wang et al. (56) developed an image analysis workflow that starts by dividing H&E images into superpixels (small regions with relatively homogeneous cellular components and morphology) and then extracts visual features related to intensity, texture, shape, and cellular density from such super pixels. They studied the correlation between the extracted features and found association with overall survival. A limitation of this work is the use of frozen sections, which may contain larger artifacts compared to formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded images.

Finally, Zhao et al. (57) developed a neural network that integrates features of an entire H&E image and clinicopathological factors (e.g., T-stage and N-stage) for stratifying patients into groups with different survival outcomes. Remarkably, authors validated their model using data of the public dataset The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). The use of public datasets is highly encouraged nowadays as they allow researchers to compare the performance of different algorithms and models on a standardized set of data. Moving forward, this work would benefit from experimentation on larger datasets; ideally, on prospective clinical trials.

Of note, even though approaches using ancillary techniques such as IHC or MIBI-TOF may appear more convenient given its utility to identify cell phenotypes (e.g., CD3+ cells, CD4+ cells) that are not discernible using H&E alone, they are more expensive, time-consuming, and not routinely used everywhere. As H&E is the standard for pathology diagnosis and is widespread, approaches based on this staining technique have the potential to be more quickly adopted in actual clinical scenarios.

Biomarkers based on Radiomics

Different imaging techniques such as mammography, ultrasound, and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE)-MRI characteristics have been used for screening and prognostic evaluation in TNBC. For example, Li et al. (58) used mammography and ultrasound to identify aberrant imaging features in TNBC tumors. They found that a spiculated margin and increased posterior acoustic enhancement with spotted patterns in color Doppler flow imaging were associated with a worse prognosis. Other works (59-63) have explored the prognostic value of vascular characteristics of the tumor obtained from DCE-MRI such as rim enhancement. Rim enhancement is the pronounced contrast at the tumor periphery compared to the center of the tumor, caused by lower micro-vessels within the tumor. This is associated with fast tumor development, less tumor differentiation, fibrosis, and necrosis (60). Interestingly, among all breast cancer subtypes, ER-negative and TNBC subtypes are observed to have a high percentage of rim-enhanced regions. Furthermore, TNBC patients with rim enhancement showed shorter survival than those without it (64.3% vs. 94.4% 10-year survival) (60). Similarly, other authors investigated the association between image features, clinical factors such as lymphovascular invasion, and recurrence. Lymphovascular invasion, is the infiltration of tumor emboli into the blood vessels and lymphatic spaces (64). In 281 surgically confirmed TNBC cases, rim enhancement and lymphovascular invasion were independently associated with recurrence. Additionally, 3D voxel-based radiomic features from DCE-MRI built a risk score capable of predicting systemic recurrence in TNBC patients (65).

Many studies have explored Nomograms for prognostication of patients with TNBC. They have shown promising results by outperforming clinical models (66-68). A nomogram is a statistical predictive tool that considers a range of variables that help in predicting patient outcomes (66). Radiomics signatures, concocted using machine learning on ultrasound images after resection of TNBC, found that radiomics nomogram performed better in predicting disease-free survival (DFS) than a clinicopathology-based model and a tumor node metastasis staging system (p<0.01). The concordance indices were 0.75, 0.73 and 0.71 for training, internal, and external validation, respectively (63). Similarly, Wang et al. (69) combined ultrasound radiomics with clinicopathological features and implemented an improved feature sampling method to boost DFS prediction, increasing the AUC from 0.69 to 0.9. Likewise, Jiang et al. (66) developed a nomogram using mammography-derived textural features from patients with TNBC. Features such as the grey-level co-occurrence matrix, the neighborhood grey-level different matrix, the grey-level run length matrix, and the grey-level zone length matrix were prominent characteristics that contributed to prognostic information. Furthermore, a study by Xia et al. (70) investigated the association of DFS from preoperative MRI scans of patients before being treated by NACT. A Rad-score of 0.2528 effectively distinguished patients into low- and high-risk groups for DFS in both the training and external validation sets. Through a comprehensive analysis, the study identified three independent markers: multifocal/centric disease, pCR status, and the Rad-score. These markers were incorporated into a nomogram, which exhibited significant discriminatory capability. A concordance index (C-index) of 0.834 (95% CI, 0.761–0.907) for training, and 0.868 (95% CI, 0.787–949) for validation was achieved. The model surpassed the clinico-radiological nomogram by obtaining higher C-index values, thus demonstrating enhanced predictive performance for DFS. Similar performance levels were observed when the radiomic features extracted from T2 weighed and T1-weighed MRI scans were associated with DFS (p = 0.002 on training and 0.033 on validation datasets). Thus, nomograms constructed from ultrasound, mammography, and MRI features consistently demonstrated superior performance compared to clinicopathological or clinico-radiological models.

Tumor heterogeneity is a vital indicator of distinct molecular and cellular subpopulations within a tumor, which can have implications for prognosis, treatment response, and disease progression. Jiang et al. (71) identified TNBC molecular subtypes and measured peritumoral heterogeneity to predict patient outcomes (See Figure 2c). They employed a cohort of TNBC patients who underwent both preoperative MRI and genomic profiling. The researchers focused on classifying TNBC patients into four molecular subtypes based on radiomic features, namely basal-like immune suppressed (BLIS), immunomodulatory (IM), mesenchymal like (MES), and luminal androgen receptor (LAR). They discovered that combining radiomics with other approaches, such as IHC, held promise for identifying TNBC molecular subtypes. Furthermore, they investigated robust prognostic radiomic features in 202 TNBC patients. Among them, an interesting peritumoral feature extracted from the gray level dependence matrices is Peri_V_DN (71). This feature has displayed a strong correlation between the aggressiveness of the tumor and unfavorable prognosis (Figure 2c). Experiments indicated that the high Peri_V_DN group tended to encompass a greater number of immune-desert tumor clusters while the low Peri_V_DN group exhibited a higher prevalence of immune-inflamed tumor clusters (p = 0.09). Moreover, this study used transcriptomic and metabolomic data to suggest that peritumoral heterogeneity could be linked to aberrant metabolism and suppressed immune reactions.

As explained earlier, a deep understanding of TILs, encompassing their density and spatial configuration, is crucial for gaining insights into the immune status and effectively predicting treatment response. Due to the reliance on pathological slides for the assessment of TILs, Su et al. (72) employed radiomics features instead to create a TILs-predicting model. Subsequent examination using transcriptomics confirmed that tumors with elevated TILs predicted by radiomics (Rad-TILs) exhibited heightened activation of immune-related pathways. Moreover, high Rad-TILs tumors displayed a vibrant immune microenvironment characterized by increased T cell infiltration gene signatures, cytokines, costimulators, major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs), CD8+ T cells, follicular helper T cells, and memory B cells. Thus, the transcriptomics analysis helped validate the radiomic signatures.

Though studies have primarily focused on MRI features while examining the correlation between TIL levels and pCR, Yu et al. (73) illustrated this association in digital mammographic images (See Figure 2b). Since Mammography is widely employed as the primary approach for routine breast cancer screening, the implementation of automated radiomics analysis to assess TIL levels could offer significant insights in identification and management of TNBC. The study identified six radiomics features (uniformity, variance, GLCM correlation, GLDM low gray level emphasis, NGTDM contrast, and GLCM autocorrelation) as the most significant variables influencing tumor TILs. These mammographic features not only differentiate between high and low TIL levels in TNBC patients, but they also serve as imaging biomarkers, enhancing the diagnosis and response assessment of neoadjuvant therapies and immunotherapies. However, most of the radiomics features that exhibited differences between the two TIL levels did not show statistical significance. Based off these findings, conducting a follow-up study comparing the performance of these features to MRI data in the same patient population could be revealing.

3.2. Machine Learning based treatment response prediction in TNBC

As previously mentioned, TNBC is often treated with conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy (8). After receiving NACT, the patients who achieve pCR (i.e., complete absence of signs of in situ or invasive tumor), present favorable survival rates (47,74,75). Unfortunately, about 80% of the patients do not achieve pCR and are at high risk of relapse, meaning they experience unnecessary morbidity for receiving a highly toxic treatment with limited benefit (74,75). This situation reflects the need of developing biomarkers to identify patients who will achieve pCR, so physicians may have an opportunity to improve treatment planning with more aggressive or novel treatments while preventing overtreatment in patients expected to achieve pCR with the standard of care (74). Figure 2 shows an example pipeline for TNBC pathological pCR prediction for both computational pathology and radiomics approaches.

Biomarkers based on computational pathology

Different AI-based imaging pCR predictors have been presented in the literature (Table 1); most of them have used deep learning approaches. Naylor et al. (76) introduced a deep learning model for predicting response to NACT employing pre-treatment samples. Using a dataset containing H&E-stained samples of patients with TNBC digitized at 40x, this model achieved a modest area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) of 0.65 at predicting pCR. Dodington et al. (77) used H&E samples of both HER2-positive and TNBC patients. They used three deep learning models for tumor bed detection and nuclear features, and then features related to nuclear color, shape, and texture were extracted. These features were used to train a logistic regression model for predicting response to NACT, which yielded an accuracy of 79% at predicting partial and complete response. An important limitation of this study, however, is the low number of samples. Duanmu et at. (78) developed a deep learning model to predict pCR to NACT using a combination of H&E and two immunohistochemical biomarkers (Ki67 and phosphohistone H3 [PHH3]). Experiments using pre-treatment samples from 73 patients with TNBC yielded a 93% patient-level accuracy. Finally, Ogier du Terrail et al. (79) presented a federated learning approach in which they collected 519 whole slide images of patients treated at two cancer centers and used a series of neural networks to predict pCR. On a validation subset, this approach achieved AUCs of 61.5 and 78.0 for the first and second centers, respectively. An interesting finding of this work is that machine learning models relying on whole slide images can predict response to NACT, but collaborative training of machine learning models further improves performance.

Biomarkers based on radiomics

Deep learning approaches to predict systemic recurrence after NACT have been developed on DCE-MRI pre-NACT and post- NACT (80). Models built on these scans include independent clinical factors. Ma et al. (80) showed that combining both pre- and post-NACT image features was highly predictive of systemic recurrence, this model performed better than the clinical model.

Huag et al. (81) conducted a study showcasing the potential of longitudinal MRI-based ensemble learning models in assessing response to NACT in various breast cancer subtypes including TNBC. The study gathered longitudinal MRI data, which encompassed both pre-NACT and post-NACT sequences, providing a comprehensive understanding of tumor changes during NACT. These findings emphasized the significance of pre-NACT, post-NACT, and delta-NACT features in accurately predicting pCR. Notably, the Shapley analysis of the features consistently revealed that delta-NACT features had the highest contribution, followed by post-NACT features and pre-NACT features, across all subtypes. Th model yielded high accuracy in the validation cohorts: cohort 1 achieved AUCs of 0.904 (HR+/HER2−), 0.896 (HER2+), and 0.873 (TNBC) while cohort 2 attained AUCs of 0.908 (HR+/HER2−), 0.929 (HER2+), and 0.901 (TNBC), cohort 3 exhibited AUCs of 0.882 (HR+/HER2−), 0.920 (HER2+), and 0.837 (TNBC). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the presence of a class imbalance problem, with TNBC cases representing less than 18% of the total cases, and the existence of tumor heterogeneity within TNBC cases may have contributed to the relatively low AUCs observed across the different cohorts.

Although some radiomics-based biomarkers have shown potential for prognosis and predicting response, they have not been standardized yet. This is specifically true for background parenchymal enhancement (BPE) on MRI, prevalent in TNBC patients (82,83). Although preliminary studies have shown that BPE is a likely marker of pCR after NACT, the substantial variability observed necessitates the validation of this finding using external datasets (83).

Additionally, Jimenez et al. (84), developed a model combining pretreatment MRI radiomics features and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes to predict response to NACT. Although the performance of the radiomics features (p = 0.001, 72.7% positive predictive value (PPV), 72.0% negative predictive value [NPV]) were comparable to the TIL-based model (p = 0.038, 65.5% PPV, 72.6% NPV), combined features improved the prognosis accuracy considerably (p < 0.001, 90.9% PPV, 81.4% NPV). Consequently, the study demonstrated that image characteristics benefited from clinicopathological information, particularly in cases with sampling bias. 3D volumetric tumor radiomic features have also been investigated in association with pCR (85). Features such as lower entropy, lower maximum signal intensity and standard deviation of intensity, and higher mean, median, and minimum intensity have been correlated with pCR. An additional parameter that helped assess the complete response such as Residual Cancer Burden (RCB), was found to be correlated with the signal intensities (statistical measures of signal intensity) extracted from the volumetric data. However, these findings, based on a sample size of 27 TNBC cases, require testing on prospective, multi-institutional data that includes other postcontrast series.

The application of deep learning techniques has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in accurately segmenting TNBC tumors (86) and distinguishing them from non-TNBC cases, marking a significant milestone in diagnosis (87). However, the true power of machine learning lies in its potential for prediction and prognostication, going beyond tumor classification. By leveraging vast amounts of data and complex algorithms, machine learning can provide insights into the future behavior and outcomes of TNBC patients. With the ability to analyze various factors such as molecular markers, patient demographics, treatment protocols, and clinical histories, these algorithms can generate personalized prognostic models for TNBC patients, aiding in treatment planning and decision-making.

4. Challenges and opportunities

4.1. Novel and underexplored biomarkers

Most of the current AI-enabled imaging prognostic biomarkers have focused on analyzing TILs. However, as previously mentioned, an important body of research has been devoted to identifying mutations and subtypes of TNBC that are associated with prognosis and response to treatment, and this presents a great opportunity for developing novel AI-imaging biomarkers.

For instance, previous research has shown that PI3K downregulation holds potential for identifying glioblastoma patients who will respond to ICI. Bearing this in mind, in a preliminary work, Mo et al. (89) developed a radiomics approach that extracted features relating to shape, intensity, fractal, and texture from MRI for automatic identification of PI3K-activated glioblastoma. An analogous approach could be developed for TNBC in which the PIK3CA gene is one of the most common mutations (10), thereby helping in identifying patients who may benefit from immunomodulation. Similarly, Shiri et al. developed a radiomics signature that used PET/CT images for prediction of KRAS and EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer that were associated with response to targeted therapy (90). This approach could be extrapolated to the TNBC space for identifying imaging features correlated with PARP inhibitor or androgen receptor response, for example. Along the same lines, other potential biomarkers that could be captured by means of image analysis include cytokine signaling pathways, which are associated with immunomodulators; hormone receptor signaling, associated with LAR; growth factor signaling pathways, associated with mesenchymal subtype; and finally downregulation of immune response, cell activation, and DNA repair pathways, which are associated with BLIS (91).

It is important to mention that although these models have been developed for other types of cancer, they hold immense potential for translation and utilization in the context of TNBC. While TNBC is a distinct subtype of breast cancer with unique molecular characteristics, the fundamental principles of AI remain applicable across different cancer types: these models have been trained on vast amounts of diverse data, enabling them to recognize patterns, identify relevant features, and make accurate predictions. By leveraging this existing knowledge and expertise, AI-based imaging models can be adapted and fine-tuned to analyze TNBC-specific datasets, facilitating the discovery of valuable insights.

4.2. Validation using retrospective and prospective clinical trials

The majority, if not all, of the prognostic and predictive biomarkers have been developed using retrospective datasets with rather limited sample sizes. Aiming to develop robust approaches that can be translated into clinical scenarios, a robust validation must be carried out. An approach towards this direction is validation using prospective clinical trials (92). For example, Li et al. (93) developed a computational pathology model that characterizes the collagen fiber organization on H&E images from patients with ER-positive cancer for prognosticating disease-free survival. Interestingly, the model was trained using samples from TCGA and validated on patients from the prospective clinical trial Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study E2197 (ECOG 2197). Considering the considerable quantity of clinical trials that have been and are being carried out for TNBC, this situation presents an important opportunity for a robust validation.

Another alternative is to acquire data for validation prospectively. This could be done as part of a secondary objective in a phase II or III clinical trial involving the target population (92), with well-defined procedures for both radiological image acquisition and tissue sample processing and digitization. Such prospective studies should, ideally, involve multiple centers thereby facilitating a rapid acquisition of a large number of samples from a broader population (92).

4.3. Data access

Data access represents an important challenge for developing prognostic and predictive biomarkers. Given the sensitivity of the data employed for these tasks, multiple medical centers may be reluctant to share information with external entities. Currently, data use agreements (DUAs) have enabled data transferring while enforcing data protection; however, the procedures related to DUAs may be laborious and time consuming. New paradigms such as collaborative federated learning offer a promising alternative to deal with data access. Federated learning is a distributed, decentralized training process that aims to build machine learning models on local datasets and exchange updates to the model across centers in a secure and traceable procedure. It facilitates the training of a single global model that has indirectly been exposed to data from all centers (79). In this way, original institutions preserve data control and ownership while enabling collaboration. This approach, which can revolutionize biomedical research, has been started to be explored in the field of TNBC (79).

4.4. Predicting response to immunotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy

In recent years, there is a growing interest in the identification and development of predictive approaches for the efficacy of treatments such as chemotherapy or immunotherapy, and imaging-based biomarkers have a lot of potential for this task (94). In lung cancer, for example, imaging-based biomarkers have been used to predict response to immunotherapy. Khorrami et al. (95) extracted texture features from CT scans from patients with non-small lung cancer before and after two to three cycles of ICI therapy, and they found that changes in radiomic patterns from the intra- and peri-nodular regions are associated with response to therapy. Similarly, Vaidya et al. (96) used intra- and peri-tumoral textural patterns as well as tortuosity of tumor-associated vasculature to characterize patients treated with ICI. This study found that such radiomics features are useful to differentiate among responders, non-responders, and hyper progressors, i.e., patients who experience an accelerated disease progression after initiation of immunotherapy. Finally, Wang et al. (97) developed an automated image classifier that characterizes the spatial architecture and arrangement of TILs on H&E images to predict clinical outcomes in ICI-treated patients.

Although imaging-based biomarkers for predicting response to immunotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy have not been widely investigated in TNBC, this area has much potential. Imaging-based biomarkers offer multiple advantages, for example they are inexpensive, non-invasive (for the case of radiomics), non-tissue destructive (for the case of computational pathology) and can provide quantitative metrics for characterizing the tumor heterogeneity. Future work may benefit from developing models for response to therapy and validating on specimens from recent clinical trials that have shown promising results in the treatment of patients with TNBC, for example IMpassion130 or KEYNOTE-355.

4.5. AI for identifying potential differences between populations

As previously mentioned, TNBC disproportionately affects some populations, e.g., Black women. Computerized analysis of images from patients with TNBC can enable interrogation of morphology and architecture of the tissue, which could help to discover biological differences between different populations. For instance, Koyuncu et al. have shown that morphologic differences between Black and White populations are statistically significant in oropharyngeal cancer (98). AI holds potential in providing more optimized and tailored disease outcome predictions for TNBC, which may potentially aid underserved communities and play a critical role in efforts to eliminate disparities.

4.6. Translation into actual clinical environments

The final aim of development of prognostic and predictive biomarkers is to achieve translation into the clinical workflow, so they can be used as companion tools to guide treatment decisions. Before this is a reality, there are multiple challenges that need to be addressed. Undoubtedly, the most important challenge is related to the effectiveness of the biomarkers. First, it is imperative that the biomarkers have demonstrated a reasonable accuracy while validated on independent large datasets (92); however, there are other important points to consider.

Interpretation of the results provided by the AI-enabled imaging biomarkers is imperative. If pathologists, radiologists, or oncologists do not understand what features AI algorithms use and how the algorithms make decisions, they will be reluctant to believe results and adopt AI approaches. This is especially important for deep-learning-based approaches, which are characterized by their black box nature. In those cases, the use of methods to aid interpretability (e.g., GradCAM) will be imperative (92). Along similar lines, engineers need to develop user friendly graphic interfaces that facilitate physicians’ use of such AI algorithms.

Other important considerations include infrastructure. AI-based imaging biomarkers require a powerful hardware infrastructure that guarantees efficient data analysis. Similarly, Internet bandwidth may constitute a barrier considering the amount of data that needs to be transferred, which is especially relevant for computational pathology images characterized by their large size on the order of Gigabytes. Hospitals and medical centers interested on the use of AI-enabled software must be willing to invest in an adequate infrastructure that supports the entire workflow.

Finally, one important issue with the clinical translation of AI-based imaging biomarkers is the appropriate regulatory approval pathways from agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). At present, there is no FDA-approved AI-based imaging biomarkers for TNBC on the market. Fortunately, there are initiatives focused on supporting the development and approval of similar approaches such as the Digital Health Innovation Action Plan. Some AI-enabled approaches have already been approved by the FDA (e.g., Paige Prostate for identify areas of interest on prostate biopsy images or Aidoc’s software for identifying intracranial hemorrhage in head CTs), which could pave the way for future approval of AI-based biomarkers for TNBC.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute under award numbers R01CA268287A1, U01CA269181, R01CA26820701A1, R01CA249992-01A1, R01CA202752-01A1, R01CA208236-01A1, R01CA216579-01A1, R01CA220581-01A1, R01CA257612-01A1, 1U01CA239055-01, 1U01CA248226-01, 1U54CA254566-01, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute 1R01HL15127701A1, R01HL15807101A1, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering 1R43EB028736-01, VA Merit Review Award IBX004121A from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, through the Breast Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-19-1-0668), the Prostate Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-20-1-0851), the Lung Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-18-1-0440, W81XWH-20-1-0595), the Peer Reviewed Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-18-1-0404, W81XWH-21-1-0345, W81XWH-21-1-0160), the Kidney Precision Medicine Project (KPMP) Glue Grant, the Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer SPORE grant P50 CA116201 from the National Institutes of Health, and sponsored research agreements from Bristol Myers-Squibb, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli-Lilly and Astrazeneca. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Michael Konomos, MS, CMI for designing Figure 1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

Dr Madabhushi is an equity holder in Elucid Bioimaging and in Inspirata Inc. In addition, he has served as a scientific advisory board member for Inspirata Inc, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb and Merck. Currently, he serves on the advisory board of Aiforia Inc. He also has sponsored research agreements with Philips, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Bristol Myers Squibb. His technology has been licensed to Elucid Bioimaging. He is also involved in a NIH U24 grant with PathCore Inc, and 3 different R01 grants with Inspirata Inc. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2021. May;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Miller KD, Kramer JL, Newman LA, Minihan A, et al. Breast Cancer Statistics, 2022. CA A Cancer J Clinicians. 2022. Nov;72(6):524–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertucci F, Finetti P, Cervera N, Esterni B, Hermitte F, Viens P, et al. How basal are triple-negative breast cancers? Int J Cancer. 2008. Jul 1;123(1):236–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abramson VG, Lehmann BD, Ballinger TJ, Pietenpol JA. Subtyping of triple-negative breast cancer: Implications for therapy: Subtyping Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer. 2015. Jan 1;121(1):8–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000. Aug 17;406(6797):747–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakashoji A, Matsui A, Nagayama A, Iwata Y, Sasahara M, Murata Y. Clinical predictors of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncology Letters. 2017. Oct;14(4):4135–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, et al. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Clinical Features and Patterns of Recurrence. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007. Aug 1;13(15):4429–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown LC, Salgado R, Luen SJ, Savas P, Loi S. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyctes in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Update for 2020. Cancer J. 2021. Jan;27(1):25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris LN, Ismaila N, McShane LM, Andre F, Collyar DE, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Use of Biomarkers to Guide Decisions on Adjuvant Systemic Therapy for Women With Early-Stage Invasive Breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016. Apr 1;34(10):1134–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bianchini G, Balko JM, Mayer IA, Sanders ME, Gianni L. Triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016. Nov;13(11):674–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergin ART, Loi S. Triple-negative breast cancer: recent treatment advances. F1000Res. 2019. Aug 2;8:F1000 Faculty Rev–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collignon J, Lousberg L, Schroeder H, Jerusalem G. Triple-negative breast cancer: treatment challenges and solutions. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2016. May 20;8:93–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu M, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Wu M, Ye Z. Imaging-based Biomarkers for Predicting and Evaluating Cancer Immunotherapy Response. Radiology: Imaging Cancer. 2019. Nov 1;1(2):e190031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jatoi I, Sung H, Jemal A. The Emergence of the Racial Disparity in U.S. Breast-Cancer Mortality. N Engl J Med. 2022. Jun 23;386(25):2349–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sturtz LA, Melley J, Mamula K, Shriver CD, Ellsworth RE. Outcome disparities in African American women with triple negative breast cancer: a comparison of epidemiological and molecular factors between African American and Caucasian women with triple negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014. Feb 4;14(1):62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stark A, Kleer CG, Martin I, Awuah B, Nsiah-Asare A, Takyi V, et al. African ancestry and higher prevalence of triple-negative breast cancer: findings from an international study. Cancer. 2010. Nov 1;116(21):4926–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doepker MP, Holt SD, Durkin MW, Chu CH, Nottingham JM. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Comparison of Race and Survival. Am Surg. 2018. Jun 1;84(6):881–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tariq K, Latif N, Zaiden R, Jasani N, Rana F. Breast cancer and racial disparity between Caucasian and African American women, part 1 (BRCA-1). Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2013. Aug;11(8):505–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoskins KF, Danciu OC, Ko NY, Calip GS. Association of Race/Ethnicity and the 21-Gene Recurrence Score With Breast Cancer-Specific Mortality Among US Women. JAMA Oncol. 2021. Mar 1;7(3):370–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Timmeren JE, Cester D, Tanadini-Lang S, Alkadhi H, Baessler B. Radiomics in medical imaging—“how-to” guide and critical reflection. Insights Imaging. 2020. Dec;11(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayerhoefer ME, Materka A, Langs G, Häggström I, Szczypiński P, Gibbs P, et al. Introduction to Radiomics. J Nucl Med. 2020. Apr;61(4):488–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bera K, Schalper KA, Rimm DL, Velcheti V, Madabhushi A. Artificial intelligence in digital pathology – new tools for diagnosis and precision oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(11):703–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong R, Fenyö D. Deep Learning and Its Applications in Computational Pathology. BioMedInformatics. 2022. Feb 3;2(1):159–68. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viswanathan VS, Toro P, Corredor G, Mukhopadhyay S, Madabhushi A. The state of the art for artificial intelligence in lung digital pathology. The Journal of Pathology. 2022. Jul;257(4):413–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015. May;521(7553):436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mireștean CC, Volovăț C, Iancu RI, Iancu DPT. Radiomics in Triple Negative Breast Cancer: New Horizons in an Aggressive Subtype of the Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022. Jan;11(3):616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L, Yang W, Xie X, Liu W, Wang H, Shen J, et al. Application of digital mammography-based radiomics in the differentiation of benign and malignant round-like breast tumors and the prediction of molecular subtypes. Gland Surgery. 2020. Dec;9(6):2005016–2002016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwamoto T, Kajiwara Y, Zhu Y, Iha S. Biomarkers of neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Chinese Clinical Oncology. 2020. Jun;9(3):27–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukhopadhyay S, Feldman MD, Abels E, Ashfaq R, Beltaifa S, Cacciabeve NG, et al. Whole Slide Imaging Versus Microscopy for Primary Diagnosis in Surgical Pathology: A Multicenter Blinded Randomized Noninferiority Study of 1992 Cases (Pivotal Study). American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2018. Jan;42(1):39–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keren L, Bosse M, Marquez D, Angoshtari R, Jain S, Varma S, et al. A Structured Tumor-Immune Microenvironment in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Revealed by Multiplexed Ion Beam Imaging. Cell. 2018. Sep;174(6):1373–1387.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wimberly H, Brown JR, Schalper K, Haack H, Silver MR, Nixon C, et al. PD-L1 Expression Correlates with Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. Cancer Immunology Research. 2015. Apr 1;3(4):326–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El Bairi K, Haynes HR, Blackley E, Fineberg S, Shear J, Turner S, et al. The tale of TILs in breast cancer: A report from The International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group. npj Breast Cancer. 2021. Dec 1;7(1):150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dieci MV, Radosevic-Robin N, Fineberg S, van den Eynden G, Ternes N, Penault-Llorca F, et al. Update on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer, including recommendations to assess TILs in residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy and in carcinoma in situ: A report of the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group on Breast Cancer. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2018. Oct;52:16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao G, Wang Z, Qu X, Zhang Z. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with triple-negative breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2020. Dec;20(1):179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kilmartin D, O’Loughlin M, Andreu X, Bagó-Horváth Z, Bianchi S, Chmielik E, et al. Intra-Tumour Heterogeneity Is One of the Main Sources of Inter-Observer Variation in Scoring Stromal Tumour Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers. 2021. Aug 31;13(17):4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.García-Teijido P, Cabal ML, Fernández IP, Pérez YF. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Triple Negative Breast Cancer: The Future of Immune Targeting. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2016. Jan;10s1:CMO.S34540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salgado R, Denkert C, Demaria S, Sirtaine N, Klauschen F, Pruneri G, et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(2):259–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balkenhol MCA, Ciompi F, Świderska-Chadaj Ż, van de Loo R, Intezar M, Otte-Höller I, et al. Optimized tumour infiltrating lymphocyte assessment for triple negative breast cancer prognostics. The Breast. 2021. Apr;56:78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun P, He J, Chao X, Chen K, Xu Y, Huang Q, et al. A Computational Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Assessment Method Comparable with Visual Reporting Guidelines for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. EBioMedicine. 2021. Aug;70:103492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hendry S, Salgado R, Gevaert T, Russell PA, John T, Thapa B, et al. Assessing Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Solid Tumors: A Practical Review for Pathologists and Proposal for a Standardized Method from the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarkers Working Group: Part 2: TILs in Melanoma, Gastrointestinal Tract Carcinomas, Non–Small Cell Lung Carcinoma and Mesothelioma, Endometrial and Ovarian Carcinomas, Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck, Genitourinary Carcinomas, and Primary Brain Tumors. Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 2017. Nov;24(6):311–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dieci MV, Tsvetkova V, Griguolo G, Miglietta F, Tasca G, Giorgi CA, et al. Integration of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes, programmed cell-death ligand-1, CD8 and FOXP3 in prognostic models for triple-negative breast cancer: Analysis of 244 stage I–III patients treated with standard therapy. European Journal of Cancer. 2020. Sep;136:7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McIntire PJ, Zhong E, Patel A, Khani F, D’Alfonso TM, Chen Z, et al. Hotspot enumeration of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes using digital image analysis in triple-negative breast cancer yields consistent results. Human Pathology. 2019. Mar;85:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bai Y, Cole K, Martinez-Morilla S, Ahmed FS, Zugazagoitia J, Staaf J, et al. An Open-Source, Automated Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Algorithm for Prognosis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2021. Oct 15;27(20):5557–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mi H, Gong C, Sulam J, Fertig EJ, Szalay AS, Jaffee EM, et al. Digital Pathology Analysis Quantifies Spatial Heterogeneity of CD3, CD4, CD8, CD20, and FoxP3 Immune Markers in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Front Physiol. 2020. Oct 19;11:583333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan Y Modelling the spatial heterogeneity and molecular correlates of lymphocytic infiltration in triple-negative breast cancer. J R Soc Interface [Internet]. 2015;12(103). Available from: http://rsif.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/12/103/20141153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu Z, Xu S, Shao W, Wu Y, Zhang J, Han Z, et al. Deep-Learning–Based Characterization of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Breast Cancers From Histopathology Images and Multiomics Data. JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics. 2020. Nov;(4):480–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hatzis C, Symmans WF, Zhang Y, Gould RE, Moulder SL, Hunt KK, et al. Relationship between Complete Pathologic Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Survival in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016. Jan 1;22(1):26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corredor G, Toro P, Lu C, Fu P, Vinayak S, Castillo Garcia M, et al. Computational features of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte architecture of residual disease after chemotherapy on H&E images as prognostic of overall and disease-free survival for triple-negative breast cancer. JCO. 2021. May 20;39(15_suppl):584–584. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu G, Li X, He TF, Gruosso T, Zuo D, Souleimanova M, et al. Predicting Relapse in Patients With Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) Using a Deep-Learning Approach. Front Physiol. 2020. Sep 23;11:511071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selvaraju RR, Cogswell M, Das A, Vedantam R, Parikh D, Batra D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) [Internet]. Venice: IEEE; 2017. [cited 2023 May 30]. p. 618–26. Available from: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8237336/ [Google Scholar]

- 51.Humphries MP, Hynes S, Bingham V, Cougot D, James J, Patel-Socha F, et al. Automated Tumour Recognition and Digital Pathology Scoring Unravels New Role for PD-L1 in Predicting Good Outcome in ER-/HER2+ Breast Cancer. Journal of Oncology. 2018. Dec 17;2018:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernández JA, Dombrowski Y, McArt DG, Dunne PD, et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep. 2017. Dec 4;7(1):16878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J, Browne L, Slapetova I, Shang F, Lee K, Lynch J, et al. Multiplexed immunofluorescence identifies high stromal CD68+PD-L1+ macrophages as a predictor of improved survival in triple negative breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2021. Dec;11(1):21608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Millar EK, Browne LH, Beretov J, Lee K, Lynch J, Swarbrick A, et al. Tumour Stroma Ratio Assessment Using Digital Image Analysis Predicts Survival in Triple Negative and Luminal Breast Cancer. Cancers. 2020. Dec 13;12(12):3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kramer CJH, Vangangelt KMH, van Pelt GW, Dekker TJA, Tollenaar RAEM, Mesker WE. The prognostic value of tumour–stroma ratio in primary breast cancer with special attention to triple-negative tumours: a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019. Jan;173(1):55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang C, Pécot T, Zynger DL, Machiraju R, Shapiro CL, Huang K. Identifying survival associated morphological features of triple negative breast cancer using multiple datasets. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013. Jul;20(4):680–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao S, Yan CY, Lv H, Yang JC, You C, Li ZA, et al. Deep learning framework for comprehensive molecular and prognostic stratifications of triple-negative breast cancer. Fundamental Research. 2022. Jun;S2667325822002771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li B, Zhao X, Dai SC, Cheng W. Associations Between Mammography and Ultrasound Imaging Features and Molecular Characteristics of Triple-negative Breast Cancer. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2014. Apr 30;15(8):3555–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen H, Min Y, Xiang K, Chen J, Yin G. DCE-MRI Performance in Triple Negative Breast Cancers: Comparison with Non-Triple Negative Breast Cancers. Current Medical Imaging. 18(9):970–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmitz AMT, Loo CE, Wesseling J, Pijnappel RM, Gilhuijs KGA. Association between rim enhancement of breast cancer on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and patient outcome: impact of subtype. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014. Dec;148(3):541–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Szabo B, Aspelin P, Wiberg M, Tot T, Bóné B. Invasive breast cancer: Correlation of dynamic MR features with prognostic factors. European radiology. 2003. Dec 1; 13:2425–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee SH, Cho N, Kim SJ, Cha JH, Cho KS, Ko ES, et al. Correlation between High Resolution Dynamic MR Features and Prognostic Factors in Breast Cancer. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9(1):10–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu F, Hang J, Deng J, Yang B, Wang J, Ye X, et al. Radiomics features on ultrasound imaging for the prediction of disease-free survival in triple negative breast cancer: a multi-institutional study. BJR. 2021. Oct;94(1126):20210188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee YJ, Youn IK, Kim SH, Kang BJ, Park W chan, Lee A. Triple-negative breast cancer: Pretreatment magnetic resonance imaging features and clinicopathological factors associated with recurrence. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2020. Feb 1;66:36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koh J, Lee E, Han K, Kim S, Kim D kyu, Kwak JY, et al. Three-dimensional radiomics of triple-negative breast cancer: Prediction of systemic recurrence. Sci Rep. 2020. Feb 19;10(1):2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang X, Zou X, Sun J, Zheng A, Su C. A Nomogram Based on Radiomics with Mammography Texture Analysis for the Prognostic Prediction in Patients with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2020;2020:5418364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu FH, Wang JX, Ye XH, Deng J, Hang J, Yang B. Ultrasound-based radiomics nomogram: A potential biomarker to predict axillary lymph node metastasis in early-stage invasive breast cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2019. Oct;119:108658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huang X, Mai J, Huang Y, He L, Chen X, Wu X, et al. Radiomic Nomogram for Pretreatment Prediction of Pathologic Complete Response to Neoadjuvant Therapy in Breast Cancer: Predictive Value of Staging Contrast-enhanced CT. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2021. Aug 1;21(4):e388–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]