Graphical abstract

Keywords: Ethnomedicine, Ethnobotany, Folk medicine, Women, Men, Traditional knowledge

Highlights

-

•

This article highlights that the use of medicinal plants is dependent on gendered social roles and experiences, as well as population structure.

-

•

Education and urbanization exert a greater impact on the preference for biomedical or traditional medicinal usage in light of the fact that very few studies in the Arab world look at how gender and location affect how people know about and use medicinal plants.

-

•

For the first time, differences in ethnobotanical knowledge of medicinal plants between men and women, as well as rural and urban populations in the Makkah district, are documented.

Introduction

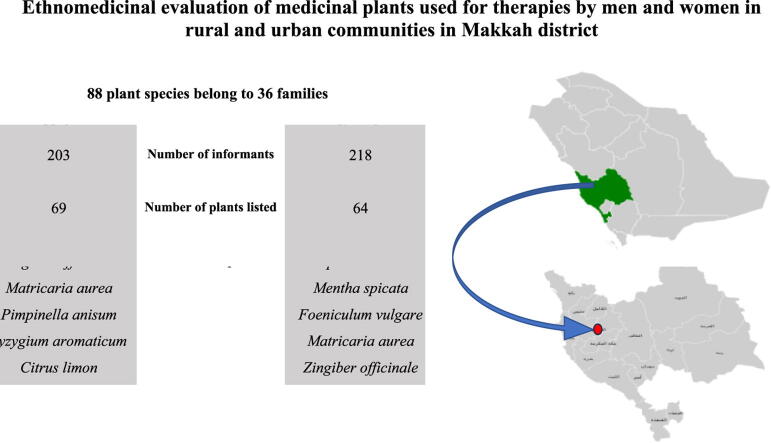

For the first time, differences in ethnobotanical knowledge of medicinal plants between men and women, as well as tribal and urban populations in the Makkah district, are investigated. The current research aims to provide responses to the following questions: (1) According to tribal and urban cultures, which medicinal plants are used by Saudis in Makkah? (2) In view of demographic differences, how much do male and female use medicinal plants? (3) Are the plants utilized by male and female considerably various? And, (4), how do men and women learn about therapeutic plants? Methods: Ethnomedicinal study was carried out in Makkah and its adjacent villages from September 2022 to January 2023. To document local medicinal plants, individuals used free-listing, semi-structured interviews, and an online survey form. In all, 59 male and 62 female were questioned face-to-face, and 239 participants completed the questionnaire, with 110 men and 129 women responding. Results: A total of 92 local folks for medicinal plants have been recorded, covering 88 different plant species belong to 36 families. Men cited 69 plants (34 families), whereas women referenced 64. (33 plant families). Males and females know in comparable ways, although they employ different medicinal herbs to remedy a variety of diseases. Conclusions: The use of medicinal plants by Saudis in Makkah is dependent on gendered social roles and experiences, as well as population structure. Education and urbanization exert a greater impact on the preference for biomedical or traditional medicinal usage.

1. Introduction

Ethnobotany is the study of the relationships and dealings between people and plants in light of gender perspectives, cultural values, etc. Interactions and relationships between people and plants are different from place to place because of their relative importance, uses, and different social, ethnic, and population factors. Plant exploration's population values are important in the pharmaceutical and nutritional industries (Thomas, 2017, Shinwari, 2010). The use of medicinal plant species for a variety of reasons is widespread in order to cover the basic needs for daily lifestyle, such as folk remediation, and to supply novel active elements for the production of modern medicines alongside the traditional ones (Hazrat et al., 2011, Yuan et al., 2016, Cheesman et al., 2017, Siraj, 2022). About 80 % of the world's population relies on an old medicinal system to treat their diseases (Mintah et al., 2019). Since ancient times, people have used an extensive variety of medicinal plants to treat a variety of diseases because they believed they had less side effects and were easy to obtain. (Savo et al., 2011, Betthauser et al., 2015, Bonini et al., 2018, Boy et al., 2018). Approximately 53,000 medicinal plant species are used for the treatment of diseases (Gulzar et al., 2019b, Gulzar et al., 2019a). For the year 2002, the value of aromatic and medicinal plants around the world was measured at $62 billion; however, this value is expected to reach $5 trillion by the year 2050 (Hamilton, 2004, Gulzar et al., 2019b, Gulzar et al., 2019a). Organic chemicals found in plants provide a source of medicines in the form of medicinal plants (Veeresham, 2012, Alqethami et al., 2020). Humans have been using medicinal plants as drugs and remedies for the treatment of various diseases since time immemorial (Savo et al., 2011, Mehmood et al., 2021). Medicinal plants are significant healthcare resources in the Arab world because they are integral parts of Prophetic medicine and because the Middle East has a longstanding tradition of studying medicinal plants (Aati et al., 2019).

Saudi Arabia was one of the world's most important crossroads, located between three continents. It has been a commerce center for centuries due to its proximity to both the Mediterranean Sea and the coasts of the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf (Vandebroek and Balick, 2012, Aati et al., 2019). This, combined with its different habitats, contributes to a wide range of native and foreign medicinal plants. It is thought that more than 1200 of the 2250 flowering plants in Saudi Arabia can be used in traditional medicine (Alqethami and Aldhebiani, 2021, Abdel-Sattar et al., 2015, Awadh Ali et al., 2017, Amar and Lev, 2017). The medicinal plants used in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia have been recorded in two volumes, “Medicinal Plants of Saudi Arabia,” published in 1987 and 2000 (Mossa, 1987, Alamgeer et al., 2013, Alqethami et al., 2020). A recent study (Aati et al., 2019) evaluated ethnomedicinal natural plants in Saudi Arabia, indicating that 309 genera and 471 species from 89 plant groups are used in traditional medicine. Although of great importance, these studies do not focus on individual differences in plant usage, nor do they focus on urban traditional medicine.

The Arab world's urban population is growing, reflecting a general trend (United Nations, 2014). This population growth is largely due to out-migration from tribal areas as people wanted good education, employment, and overall living conditions (Alqethami et al., 2020). Although biomedicine is commonly available in urban centers, healthcare dependence on medicinal plants may continue to be the most traditional and easy resource for a lot of people (Wayland and Walker, 2014, Alamgeer et al., 2013). Scientists have found that folk medicine is used a lot when people move from the village to the city (United Nations, 2014, Haque et al., 2018). Over a hundred medicinal plants have been recorded as being used in Mecca and surrounding villages in different ways depending on location, gender, experience, and level of education in Saudi Arabia (Alqethami et al., 2017). It was discovered that older people have more experience with and knowledge of medicinal plants that are used in remedy preparation than younger people. However. Men and women have different medicinal plant knowledge all over the world (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2014, Newing, 2010, Chekole et al., 2015, Bruschi et al., 2019) and may have different preferences for useful plant species (Ong and Kim, 2014, Bruschi et al., 2019). Women frequently transfer traditional medicinal plant knowledge in native medical systems (Torres-Avilez et al., 2016, Weckmüller et al., 2019). On the other hand, the men have been helped to originate this experience through the generations by some folkloric physicians throughout history, which led them to consider natural resources with a different vision (Torres-Avilez et al., 2016). Gendered divisions of occupation in traditional communities (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2014) and a focus on the diversity of learning help explain differences in knowledge between men and women. Different kinds of jobs for men and women and different ways of learning can make the knowledge of medicinal plants in urban Arab areas different from that in tribal areas (Torres-Avilez et al., 2016, da Costa et al., 2021).

The study's goal was to identify, know the correct application, and how men and women among urban and tribal peoples used medicinal plants to cure various health disorders, as well as to verify some ethnobotany facts among them in Makkah city and some surrounding villages by answering the following questions: (1) According to rural and urban cultures, which medicinal plants are used by Saudis in Makkah? (2) In view of demographic differences, how much do men and women use medicinal plants? (3) Are the plants utilized by men and women considerably different? And, (4), how do men and women learn about therapeutic plants? Considering the male and female structure of Saudi people and Arab world relations, the hypothesis is that men and women learn about plants in various cultures in different ways, which will assist in understanding any potential differences in using plants for treatments.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethics declaration

The ethnobotanical field investigation was carried out with careful attention to ethical guidelines. As the ethical criteria of the American Anthropological Association (2012) and the Code of Ethics of the International Society for Ethnobiology (2006) were adhered to, the institution's ethics committee granted official ethical approval. Ethics Committee of the Unit of Biomedical Ethics Research Committee approval, Umm Al-Qura University, was granted (Reference No HAPO-02-K-012–2023-02–1440). Before the interviews and questionnaire, each participant provided oral or written informed consent.

2.2. Survey duration

After the preliminary survey, a series of target expeditions were conducted in Makkah city and some villages during the fall and winter sessions. A detailed questionnaire for data collection was developed from September 2022 to January 2023. face to face and online-structured interviews were conducted for the ethnobotanical data collection. Before the interviews, all participants provided informed consent and consent for publication.

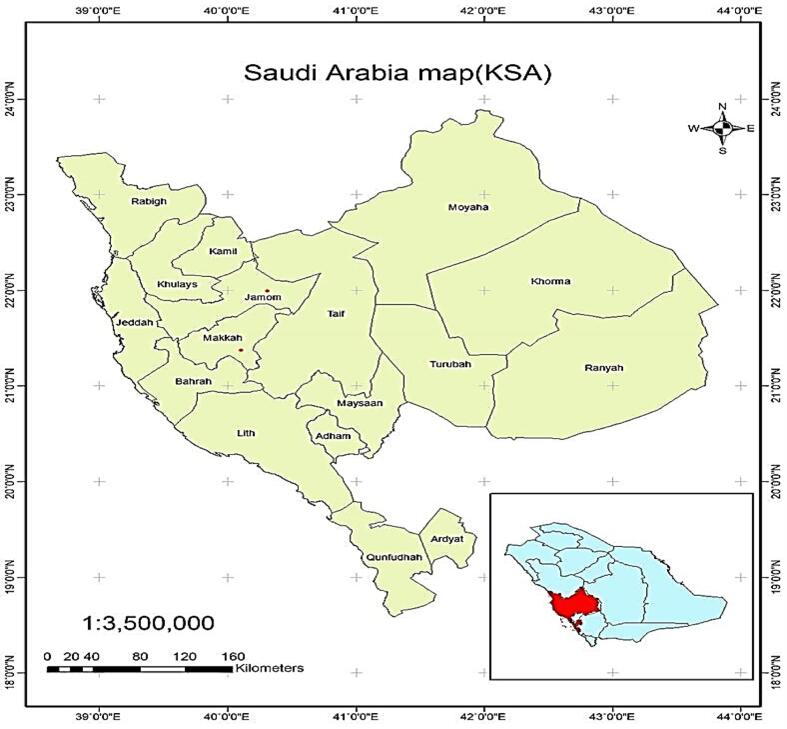

2.3. Study area

The study area District Makkah city is located in the Makkah governance area of the western region of Saudi Arabia, located at 22° 00′ and 30° 00′ North and 36° 00′ and 44° 00′ East, in a small valley (Fig. 1), 76 km south of the Red Sea coast, west of the Arabian Peninsula (Alqethami et al., 2017). Additionally, some villages surrounded Makkah in the north, e.g., Aljumum, Hada Alsham, and Alfoara. Makkah and its surrounding villages cover 1200 square kilometers and have a population of 9.0 million people, about 52 % Saudis and about 48 % non-Saudi nationals; the ratio of men to women is about 1.3. (Cities, 2018; UN-Habitat, 2018, General Authority for Statistics, 2023) Makkah's flora consists of plants that thrive in subtropical and arid environments.

Fig. 1.

Map of study area (red color) in Makkah region (Bayounis and Eldamaty, 2022).

2.4. Participants in the study area

The study area has a rich diversity of cultures and ethnic groups. Different languages like Arabic, Urdu, English, and others are spoken in the area. Arabic is the dominant language, as 100 % of the studied population can speak and understand it. Various ethnic groups like Saudis, Indians, Southeast Asians, and others reside in the study area. A total of 121 people, 58 men and 63 women, were interviewed about the purpose of the current study.

2.5. Data collection

Face-to-face interviews and an online questionnaire were used to collect ethno-medicinal data. The interviews with people give valuable qualitative information that serves as a benchmark for assessing results from online questionnaires. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to document medicinal plant knowledge and use; data from questionnaires were constructed using the methods of Alexandrides and Sheldon (1996) and Martin (1995), as shown in Supplementary Material (Form 1). Interviews were conducted in Arabic, the mother tongue of all participants. According to Newing's (2010) method, targeted participants who use medicinal plants were chosen. Fifty males and fifty females were questioned for a total of one hundred and twenty one participants in face-to-face interviewing (Ali et al., 2011, Mossa, 1987). Participants were divided into seven age groups: those under 25 (6.6 %), those between 25 and 34 (29.8 %), those between 35 and 44 (27.3 %), those between 45 and 54 (19.8 %), those between 55 and 64 (12.4 %), those between 65 and 74 (5.0 %), and those 75 and over (0.8 %) as illustrated in supplementary Material (Form 2). Questions were asked to record local plant names, parts used, uses, treatment and administration, toxicity and side effects, usage of mixes, and how participants learned about medicinal plants, as well as whether they preferred them over biomedicine or traditional medicine. Also, to enhance the fieldwork data, an online survey questionnaire was created with the same questions asked during face-to-face interviews. The online questionnaire page was built with Google Forms, and the link was distributed via social media. The questionnaire was completed by 239 persons, with 129 (54 % female) and 110 (46 % male) respondents. Face-to-face interviews also grouped participants into the same age categories, as shown in the supplemental material (Table S1, S2). Descriptive analyses were important for understanding individuals' attitudes, thoughts, and objectives, as well as for interpreting quantitative data (Abbas et al., 2002).

2.6. Plant collection and identification

The majority of voucher samples were received directly from informants. When this was not available, they were gathered from local apothecary plants and Alhwaj stores. Plant specimens from the Umm Al-Qura University herbarium that were not collected as voucher specimens were utilized to identify them using common names. Voucher specimens (including market samples) were stored in the herbariums of Aljumum University College, Umm Al-Qura University. Collection permissions were not required because no plants were collected freshly from the wild field. The identification of many specimens was also confirmed by taxonomist Qadri Abdul Khaleq, College of applied sciences, Umm Al-Qura University.

2.7. Literature review

A systematic literature study was carried out in order to examine the recorded Saudi Arabian medicinal plant knowledge. Google Scholar, the Saudi Digital Library, Research Gate, and the King Abdullah Library at Umm Al-Qura University searched for articles in both English and Arabic with the keywords “Medicinal Plant, Herbal Medicine, Traditional Medicine, or Ethnobotany,” with no date restrictions.

2.8. Data analysis

Regarding replies with in interviews and online questionnaires, two databases were developed. The information gathered was recorded for every individual. A single record of one participant's use of a plant that includes the common name, parts, folk usage, preparation, and intake method. Based on the basic biological mechanisms, explanatory model interview catalogue (EMIC), the diseases were assigned to one of twelve different ideographic categories of herbal remedies (digestive diseases, respiratory diseases, ear and throat diseases, neurologic diseases, dental and periodontal diseases, cardiovascular diseases, skeletal diseases, skin diseases, urologic diseases, reproductive system diseases, endocrine diseases, muscular diseases, pain killers, tonics, and carminatives); according to the international classification of primary care (ICPC) as recommended by (Staub et al., 2015). In order to provide a concise overview of the data provided within each of the databases, descriptive statistical analysis was applied. For each of the datasets, the mean and standard deviation of the number of plants mentioned by men and women within a city or village and across age groups were calculated. The ethnomedicinal information gathered during field surveys was transferred to a Microsoft Word and Excel spreadsheet and tabulated for presenting. Multiple measurement ethnobotanical statistics, such as frequency of citation (FC), fidelity level percentage (FL), and informant consensus factor (ICF), were utilized for the data visualization of the extracted statistical information.

2.8.1. Informant consensus factor (ICF)

The Factor Informant Consensus (ICF) was examined to investigate the overall application of plant species by gender and culture among participants. This criteria was developed by Heinrich et al., (1998) to determine potentially beneficial medicinal plants. FIC reveals a correlation between the number of usage reports in each medicinal category and the number of plant species used. Fic may be calculated using the formula Fic = nur - nt/nur − 1, where Fic is the informants' consensus factor, nur is the number of usage citations, and nt is the number of species used. FIC values vary between 0 and 1. The informant consensus factor was also calculated separately for men and women in order to identify any statistically significant differences (Tounekti et al., 2019, Heinrich et al., 1998; Hassan, Wang, et al., 2017; Asiimwe et al., 2021).

2.8.2. Fidelity level (FL)

The plant species that were medicinally used by men and women in Makkah city and some surrounding villages had a higher fidelity level (FL) than those with less usage. The fidelity level (FL) was calculated to identify medicinally important plant species in the study area. Aliments were grouped into different classes before computing the fidelity level. Fidelity Level (FL) was calculated using the formula FL = Ip/Iu × 100. Ip denotes the proportion of respondents who used medicinal plants for a specific disease, whereas Iu denotes the proportion of respondents who used the same plant for all diseases (Khan et al., 2014; Hassan, Wang, et al., 2017; Asiimwe et al., 2021).

3. Results

3.1. Medicinal plants traditionally used by Saudis in Makkah

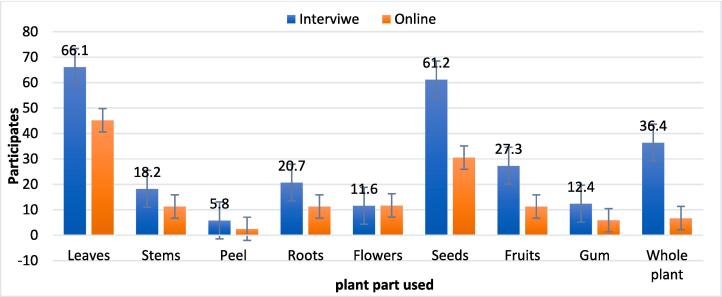

In current research survey a total of 88 medicinal plant species from 36 families were documented from 360 participants (121 from face-to-face interviews and 239 from online questionnaires) as presented in (Table 1). Plant parts were used in form of leaves (66.1 and 45.2 %), stems (18.2 and 11.3 %), peel (5.8 and 2.5 %), roots (20.7 and 11.3 %), Flower (11.6 and 11.7 %), seeds (61.2 and 30.5 %), Fruits (27.3 and 11.3 %), gum (12.4 and 5.9 %), and whole plant (36.4 and 6.7 %) for face-to-face interviews and online questionnaires respectively (Table 2). The most diverse families are Fabaceae (27.7 %; 10 species), Apiaceae (25 %; 9 species), Lamiaceae (22.2 %; 8 species). Amaranthaceae, Rosaceae, and Asteraceae were represented by five species each (13.9 %; 5 species). Zingiberaceae, Brassicaceae, Apocynaceae, and Burseraceae were represented by three species each (8.3 %). Poaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Asphodelaceae, Amaryllidaceae, Rutaceae, Myrtaceae, Lauraceae and Lythraceae were represented by two species each (5.5 %). Eighteen families were represented only by one species as presented in (Table 2). A high number of plant citations referred to four families: Apiaceae (133 citations), Lamiaceae (81 citations), Zingiberaceae (67 citations) Fabaceae (55 citations), and Brassicaceae (51 citations). The most popular medicinal species used in current study is Pimpinella anisum L. (57 citations), followed by Zingiber officinale Roscoe (45 citations), Matricaria aurea (Loefl.) Boiss (39 citations), Foeniculum vulgare Mill. (35 citations) and 24 citations for both Psidium guajava and Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L.M.Perry as shown in (Table 2).

Table 1.

An overview of the demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Variables | Participants' category | Number of participants |

Average number of ethno-species listed |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews |

Online questionnaire |

Interviews |

Online questionnaire |

||||||||||||||

| (Men + Women) |

(Men + Women) |

||||||||||||||||

| % | T | W | M | % | T | W | M | % | T | W | M | % | T | W | M | ||

| Age (years) | Gender | 239 | 129 | 110 | 121 | 63 | 58 | 415 | 257 | 158 | 300 | 155 | 145 | ||||

| <25 | 34.7 | 83 | 34 | 49 | 6.6 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 28.7 | 119 | 47 | 72 | 6.7 | 20 | 13 | 7 | |

| 25–34 | 25.1 | 60 | 40 | 20 | 29.8 | 36 | 17 | 19 | 28.9 | 120 | 89 | 31 | 31.7 | 95 | 42 | 53 | |

| 35–44 | 31.0 | 74 | 42 | 32 | 27.3 | 33 | 19 | 14 | 28.9 | 120 | 91 | 29 | 25.7 | 77 | 42 | 35 | |

| 45–54 | 7.5 | 18 | 10 | 8 | 19.8 | 24 | 15 | 9 | 15.9 | 66 | 44 | 22 | 18.0 | 54 | 32 | 22 | |

| 55–64 | 0.4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 12.4 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9.7 | 29 | 8 | 21 | |

| 65–74 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.0 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.7 | 17 | 11 | 6 | |

| Place | ≤75 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| City | 77.4 | 185 | 88 | 97 | 71.9 | 87 | 48 | 39 | 82.4 | 342 | 225 | 117 | 76.7 | 230 | 120 | 110 | |

| Literacy | Village | 22.2 | 53 | 42 | 11 | 28.9 | 35 | 16 | 19 | 23.6 | 98 | 84 | 14 | 23.7 | 71 | 33 | 38 |

| Illiterate | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.4 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.3 | 16 | 14 | 2 | |

| Primary education | 2.9 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 5.0 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 1.2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1.3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | |

| Secondary education | 18.4 | 44 | 17 | 27 | 43.0 | 52 | 20 | 32 | 15.4 | 64 | 28 | 36 | 42.0 | 126 | 45 | 81 | |

| Bachelor | 72.4 | 173 | 101 | 72 | 43.8 | 53 | 32 | 21 | 69.2 | 287 | 208 | 79 | 42.3 | 127 | 78 | 49 | |

| Source knowledge | Postgraduate | 1.7 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1.7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3.4 | 14 | 12 | 2 | 3.7 | 11 | 9 | 2 |

| Family | 77.8 | 186 | 97 | 89 | 83.5 | 101 | 53 | 48 | 78.3 | 325 | 210 | 115 | 75.7 | 227 | 116 | 111 | |

| Social media | 8.8 | 21 | 10 | 11 | 21.5 | 26 | 12 | 14 | 8.4 | 35 | 31 | 4 | 19.3 | 58 | 33 | 25 | |

| Internet | 9.6 | 23 | 14 | 9 | 28.9 | 35 | 17 | 18 | 12.8 | 53 | 19 | 34 | 24.3 | 73 | 34 | 39 | |

| Books | 3.3 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 5.0 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 1.9 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 4.3 | 13 | 13 | ||

| Plant part | Leaves | 45.2 | 108 | 63 | 45 | 66.1 | 80 | 40 | 40 | 34.5 | 143 | 75 | 68 | 37.3 | 112 | 60 | 52 |

| Stem | 11.3 | 27 | 13 | 14 | 18.2 | 22 | 10 | 12 | 11.6 | 48 | 22 | 26 | 12.7 | 38 | 12 | 26 | |

| Peel | 2.5 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 5.8 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 2.4 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 2.0 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| Root | 11.3 | 27 | 13 | 14 | 20.7 | 25 | 10 | 15 | 6.3 | 26 | 12 | 14 | 8.7 | 26 | 8 | 18 | |

| Flower | 11.7 | 28 | 19 | 9 | 11.6 | 14 | 11 | 3 | 7.5 | 31 | 18 | 13 | 8.3 | 25 | 16 | 9 | |

| Seeds | 30.5 | 73 | 51 | 22 | 61.2 | 74 | 41 | 33 | 20.2 | 84 | 55 | 29 | 35.0 | 105 | 57 | 48 | |

| Fruit | 11.3 | 27 | 13 | 14 | 27.3 | 33 | 17 | 16 | 6.0 | 25 | 10 | 15 | 12.3 | 37 | 13 | 24 | |

| Gum | 5.9 | 14 | 9 | 5 | 12.4 | 15 | 8 | 7 | 5.1 | 21 | 15 | 6 | 7.7 | 23 | 12 | 11 | |

| Whole plant | 6.7 | 16 | 10 | 6 | 36.4 | 44 | 19 | 25 | 7.0 | 29 | 19 | 10 | 16.7 | 50 | 23 | 27 | |

| Preparation | Decoction | 53.1 | 127 | 78 | 49 | 98.3 | 119 | 67 | 52 | 36.1 | 150 | 96 | 54 | 57.3 | 172 | 91 | 81 |

| Crushed | 28.9 | 69 | 45 | 24 | 33.9 | 41 | 19 | 12 | 16.6 | 69 | 37 | 32 | 13.0 | 39 | 22 | 17 | |

| Powder | 5.0 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 21.5 | 26 | 13 | 13 | 4.1 | 17 | 10 | 7 | 17.3 | 52 | 33 | 19 | |

| Extract | 2.5 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 6.6 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 1.0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1.7 | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| Raw | 10.9 | 26 | 17 | 9 | 14.9 | 18 | 7 | 11 | 7.0 | 29 | 19 | 10 | 11.3 | 34 | 14 | 20 | |

| Paste | 4.6 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 6.6 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4.8 | 20 | 17 | 3 | 2.7 | 8 | 3 | 5 | |

| Juice | 7.1 | 17 | 12 | 5 | 10.7 | 13 | 3 | 10 | 4.8 | 20 | 11 | 9 | 6.3 | 19 | 3 | 16 | |

| Fresh | 3.3 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 2.5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1.9 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 1.0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Administration | Oral ingestion | 74.1 | 177 | 105 | 72 | 132.2 | 160 | 88 | 72 | 53.7 | 223 | 123 | 100 | 64.3 | 193 | 86 | 107 |

| Mouth wash | 3.8 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 13.2 | 16 | 9 | 7 | 2.2 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 7.3 | 22 | 10 | 12 | |

| Rub in | 7.5 | 18 | 11 | 7 | 24.8 | 30 | 17 | 13 | 5.3 | 22 | 15 | 7 | 8.7 | 26 | 21 | 5 | |

| On wound | 2.1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1.7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2.2 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 3.3 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Feminine wash | 0.8 | 2 | 2 | 1.7 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 | 0.0 | 1 | ||||||

| Chewing | 4.2 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 5.8 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 3.4 | 14 | 11 | 3 | 3.7 | 11 | 2 | 9 | |

| Fumigation | 2.1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2.5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1.2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1.0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Hair wash | 0.4 | 1 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | ||||||||||

M=Men, W=Women.

Table 2.

A complete list of plant family used by Saudis in Makkah and the surrounding villages, including plant family and family frequency.

| No. | Family | Family frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Amaranthaceae | 5 |

| 2. | Amaranthaceae | |

| 3. | Amaranthaceae | |

| 4. | Amaranthaceae | |

| 5. | Amaranthaceae | |

| 6. | Amaryllidaceae | 2 |

| 7. | Amaryllidaceae | |

| 8. | Apiaceae | 9 |

| 9. | Apiaceae | |

| 10. | Apiaceae | |

| 11. | Apiaceae | |

| 12. | Apiaceae | |

| 13. | Apiaceae | |

| 14. | Apiaceae | |

| 15. | Apiaceae | |

| 16. | Apiaceae | |

| 17. | Apocynaceae | 3 |

| 18. | Apocynaceae | |

| 19. | Apocynaceae | |

| 20. | Arecaceae | 1 |

| 21. | Asphodelaceae | 2 |

| 22. | Asphodelaceae | |

| 23. | Asteraceae | 5 |

| 24. | Asteraceae | |

| 25. | Asteraceae | |

| 26. | Asteraceae | |

| 27. | Asteraceae | |

| 28. | Boraginaceae | 1 |

| 29. | Brassicaceae | 3 |

| 30. | Brassicaceae | |

| 31. | Brassicaceae | |

| 32. | Burseraceae | 3 |

| 33. | Burseraceae | |

| 34. | Burseraceae | |

| 35. | Capparaceae | 1 |

| 36. | Cucurbitaceae | 2 |

| 37. | Cucurbitaceae | |

| 38. | Euphorbiaceae | 1 |

| 39. | Fabaceae | 10 |

| 40. | Fabaceae | |

| 41. | Fabaceae | |

| 42. | Fabaceae | |

| 43. | Fabaceae | |

| 44. | Fabaceae | |

| 45. | Fabaceae | |

| 46. | Fabaceae | |

| 47. | Fabaceae | |

| 48. | Fabaceae | |

| 49. | Lamiaceae | 8 |

| 50. | Lamiaceae | |

| 51. | Lamiaceae | |

| 52. | Lamiaceae | |

| 53. | Lamiaceae | |

| 54. | Lamiaceae | |

| 55. | Lamiaceae | |

| 56. | Lamiaceae | |

| 57. | Lauraceae | 2 |

| 58. | Lauraceae | |

| 59. | Linaceae | 1 |

| 60. | Lythraceae | 2 |

| 61. | Lythraceae | |

| 62. | Malvaceae | 1 |

| 63. | Moraceae | 1 |

| 64. | Moringaceae | 1 |

| 65. | Myrtaceae | 2 |

| 66. | Myrtaceae | |

| 67. | Oleaceae | 1 |

| 68. | Piperaceae | 1 |

| 69. | Plantaginaceae | 1 |

| 70. | Poaceae | 2 |

| 71. | Poaceae | |

| 72. | Polygonaceae | 1 |

| 73. | Ranunculaceae | 1 |

| 74. | Rhamnaceae | 1 |

| 75. | Rosaceae | 5 |

| 76. | Rosaceae | |

| 77. | Rosaceae | |

| 78. | Rosaceae | |

| 79. | Rosaceae | |

| 80. | Rubiaceae | 1 |

| 81. | Rutaceae | 2 |

| 82. | Rutaceae | |

| 83. | Theaceae | 1 |

| 84. | Urticaceae | 1 |

| 85. | Zingiberaceae | 3 |

| 86. | Zingiberaceae | |

| 87. | Zingiberaceae | |

| 88. | Zygophyllaceae | 1 |

3.2. Ethnobotanical knowledge of medicinal plants

Out of 203 men and 218 women, informants referring to interviews and online surveys, 88 medicinal species were collected. 45 medicinal plants appear on both men's and women's lists; 22 medicinal plants are listed only by men, while 21 medicinal plants are listed exclusively by women. (Table 3). Men in Makkah and several of its villages most usually cite Zingiber officinale, Matricaria aurea, Pimpinella anisum, Syzygium aromaticum, and Citrus limon. as their preferred species. Women prefer Pimpinella anisum, Mentha spicata, Foeniculum vulgare, Matricaria aurea, Zingiber officinale, and Trigonella foenum-graecum. Women, as expected, cite more medicinal plants (353 citations) than men (282 citations) (Table 3). Also, women use a wider range of mixes (94) than men do (26), as shown in the “Supplemental Files” section under “Subtitle (Table S3)”.

Table 3.

A complete list of plants used by Saudis in Makkah and the surrounding villages, including scientific name, family, Flora of Saudi Arabia, vernacular name, therapeutic parts, frequency of citation, preparation, and administration.

| No. | scientific name | F | V | Part used | Therapeutic Use | Frequency of citation |

Preparation | Administration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | ||||||||

| Acacia ampliceps Maslin | Y | الطلح altalh | Leaves | Stop The Bleeding | 1 | 0 | decoction | Oral ingestion | |

| Acacia Senegal (L.) Willd. | N | الصمغ العربي alsamgh alarabi | Resin | For Kidneys And Salts, Arthritis, Indigestion, Back Treatment, Gingivitis | 2 | 4 | Crushed, chewing, added to water or milk, | Oral ingestion (drink, food), gargling | |

| Acacia sp. | Y | القرظ alqrd | Leaves | Body Protection | 1 | 0 | fumigation | inhalation | |

| Aerva javanica Juss. | Y | الطرف altarf | Flowers, Leaves | Diabetic - Diuretic | 1 | 1 | decoction | Oral ingestion | |

| Alkanna tinctoria Tausch | Y | الخوا جوا alkoagoa | leaves | Precipitated Blood -Uterin Air | 0 | 2 | crushed | fumigation | |

| Allium cepa L. | N | البصل albasal | Fruit | For Burns, Sniffles | 2 | 0 | decoction, Fresh | on wound, Oral ingestion | |

| Allium sativum L. | N | ثوم althom | Fruit, seeds | Disease Relief, Nerves, Uterus, Bones, Brain, Blood Pressure | 5 | 2 | By heating like tea, crushed, add to juice, chewing | Oral ingestion (drink, food) | |

| Aloe brevifolia Mill. | Y | الصبرة alsbrh | Resin | Paranasal Sinuses | 0 | 1 | crushed | Oral ingestion | |

| Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. | N | صبار sabar | Leaf, bark | Hair Strengthening, Arthritis, For The Skin | 0 | 1 | Fresh | Rub in | |

| Ammi visnaga (L.) Lam. | N | بذور الخلة bthor alklh | seeds | Bladder Stones | 0 | 1 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Anastatica hierochuntica L. | Y | كف مريم kaf maryam | Seed, leaf | Expedite Childbirth | 0 | 1 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Anethum graveolens L. | N | الشبث althbth | leaves | Respiratory System – Digestive | 1 | 0 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion | |

| anisosciadium lanatum Boiss. | Y | البسباس البري albsbas albri | Fruits | Digestive | 1 | 0 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion | |

| Artemisia Judaica L. | Y | الشيح alsheh | Shins, Leaves | Acidity, Ulcers | 1 | 0 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion | |

| Astragalus sarcocolla Dymock | Y | العنزوت alanzrot | Resin | Digestive | 1 | 2 | decoction | Oral ingestion | |

| Aucklandia costus Falc. | N | القسط الهندي alqesd alheendi | Roots, Stem | Respiratory, Delayed Pregnancy, Stomach Pain | 3 | 3 | Powder, By heating like tea | Oral ingestion (drink, food) | |

| Beta vulgaris L. | Y | البنجر albanjr | Roots | Anemia | 0 | 1 | juice | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Boswellia sacra Flück. | N | لبان الذكر lban althakr | Resin | Respiratory, Digestive | 0 | 3 | Decoction, infusion, powder, | Oral ingestion (drink, food) | |

| Cactaceae | N | الصبار alsabar | Resin | Hair Loss | 1 | 3 | Infusion | Rub in | |

| Calligonum comosum L'Hér. | الارطا alarta | shins | Feminine Lotion | 0 | 1 | solution | Feminine lotion | ||

| Calotropis procera (Aiton) Dryand. | N | العشر alashr | Resin, Leaves | Alopecia, Warts | 1 | 1 | Milky substance sweeps in alopecia | Sweep, rub in | |

| Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze | N | الشاي الاخضر alshaay alakhdar | Leaves | Digestive | 0 | 3 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Capparis spinosa L. | Y | الشفلح alshflh | Leaves | Teeth, Back Problems | 0 | 1 | crushed | On wound | |

| Carthamus tinctorius L. | العصفر alasfor | Flowers, Leaves | Respiratory, Endocrine, Treat Depression, Neurological | 2 | 2 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion (drink) | ||

| Carum carvii (Archila) J.M.H.Shaw. | Y | الكراوية alkarawia | seeds | Digestive, Menstrual Pain Relief | 5 | 0 | By heating like tea and put it with milk and honey | Oral ingestion | |

| Chenopodiastrum murale (L.) S.Fuentes, Uotila & Borsch. | N | العفينة alafenh | leaves | Teeth Pain In Babes | 0 | 1 | crushed | Put it in baby head | |

| Cinnamomum tamala T.Nees | ورق الغار warq alqar | Leaves | Respiratory, Digestive | 0 | 1 | With food | Oral ingestion (drink, food) | ||

| Cinnamomum verum J.Presl | N | القرفة alqurfa | All plant, bark, wood | Blood Sugar, Flatulence, Diarrhea, Facilitate Childbirth, Menstrual Pain | 9 | 5 | By heating like tea, crushed | Oral ingestion (drink, food) | |

| Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. | Y | الحدج alhdg | Fruits | Hemorrhoids | 2 | 0 | crushed | Rub in | |

| Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck. | N | الليمون allaymun | Leaves, Fruit | Respiratory, Stomach Pain, Ear And Throat, Hyperthermia, Cholesterol Lowering | 12 | 12 | Infusion, decoction, with honey and food, juice, powder, raw. | Oral ingestion (drink, food) | |

| Citrus-sinensis (L.) Osbeck. | N | البرتقال albortqal | Fruits | Immunity Booster, Sniffles | 5 | 2 | Fresh, juice | Oral ingestion | |

| Cocos nucifera | N | جوز الهند juz alhind | Leaf | Chronic Cough | 0 | 1 | By heating like tea, crushed, fresh, chewing | Mouth wash, Rub in | |

| Coffea arabica L. | البن alben | Seeds,peel | Wounds, Digestive | 1 | 2 | Decoction, powder | Oral ingestion, on wound | ||

| Coleus forskohlii Briq. | Y | الشار alshar | Leaves-resin | Ear Pain | 1 | 0 | Squeeze | Put in ear | |

| Commiphora gileadensis (L.) C.Chr. | Y | البشام albasham | Resin | For Burns - Wounds | 1 | 0 | Fresh | Rub in | |

| Commiphora myrrha Engl. | Y | المر almor | Resin, leaves | Hemorrhoids, Respiratory, Phlegm And Congestion, Wounds | 3 | 2 | Decoction, infusion, powder, | rub in, put it on wound, wash. | |

| Cucurbita ficifolia Bouché. | N | بذر القرع bthor alqra | Seeds | Prostate Enlargement | 1 | 0 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion | |

| Cuminum cyminum L. | Y | الكمون alkamo uwn |

Seeds, All plant | Digestive, Fungi, Flatulence | 3 | 6 | By heating like tea, crushed, solution | Oral ingestion (drink, food) | |

| Curcuma longa L. | N | الكركم alkarkum | Rhizome, All plant, fruit | Respiratory, Skeletal, Muscular Pain, For The Skin, Digestive | 8 | 13 | Decoction, infusion, powder, | Oral ingestion (drink), on wound, mouth wash | |

| Cydonia oblonga Mill. | Y | السفرجل alsfarqal | fruit | Digestive -Cholesterol -Anti-Inflammation | 0 | 1 | fresh | Oral ingestion | |

| Cymbopogon schoenanthus Spreng. | الاذخر aladhkhir | shins | Respiratory, Headache, Blood Pressure-Reduce Sugar Cholesterol-Anxiety-Stress | 2 | 5 | By heating like tea, fumigation | Oral ingestion (drink), inhalation | ||

| Elettaria cardamomum (L.) Maton | N | الهيل alhel | Seeds | Cold, Stomach | 0 | 1 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion | |

| Ferula assa-foetida L. | الحلتيت alhaltet | Seeds, Resin | Respiratory System - Digestive | 3 | 0 | Powder, By heating like tea | Oral ingestion (drink) | ||

| Ficus carica L. | Y | التين alteen | Fruits | Hemorrhoid Treatment, Blood Pressure | 1 | 1 | Juice, fresh | Oral ingestion | |

| Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | Y | الشمر alshamer | Seeds, whole plant | Digestive, Cough, Flatulence, Colic | 12 | 23 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Geum urbanum L. | Y | عشبة المدينة ashbat almadenh | Shins, Leaves | Expulsion Of Toxins | 0 | 2 | decoction | Oral ingestion | |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra L. | Y | عرق السوس arq asws | roots | Respiratory System-Skin-Stomach Sedative-Arthritis | 3 | 1 | Placed in a cloth Soaked in water | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Haloxylon salicornicum (Moq.) Bunge ex Boiss. | Y | الرمث alremth | Leaves | Joints, Bones | 3 | 0 | crushed | Rub in | |

| Hibiscus sabdariffa L. | N | الكركديه alkarkadih | Flowers, Leaves | To Lower Blood Pressure, For Healthy Hair, Sore Throat, Gastroenteritis | 6 | 3 | By heating like tea, Infusion, decoction, juice | Oral ingestion (drink), rub in | |

| Hordeum vulgare L. | N | الشعير alshair | Seeds | Kidney Pain, Diuretic, Expulsion Of Toxins | 2 | 1 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion | |

| Lawsonia inermis L. | Y | الحناء alhena | Leaves | For Hair Grow, Headaches | 0 | 2 | powder | Wash, rub in | |

| Lens culinaris Medik. | العدس aladas | Seeds | Muscular Pain | 1 | 0 | powder | on wound | ||

| Lepidium sativum L. | Y | الرشاد alrashad | Seeds | For Bruising, Hair Loss, For Bones, Diarrhea, Digestive | 3 | 10 | Powder, By heating like tea, soak with water, crushed | on wound, Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Leptadenia pyrotechnica (Forssk.) Decne. | Y | المرخ almarkh | Shins | Cough, Worms | 1 | 1 | decoction | Oral ingestion | |

| Linum usitatissimum L. | N | بذرة الكتان bthrat alkatan | seeds | Immunity Booster, Nerves, Uterus, Bones, Brain | 1 | 1 | Crushed, Fresh | On wound, Oral ingestion | |

| Malus domestica (Suckow) Borkh. | N | التفاح altofah | Peel | Immunity Booster | 0 | 1 | Fresh | Oral ingestion | |

| Matricaria aurea (Loefl.) Boiss. | Y | البابونج albabong | Flowers, Fruit, Leaves | Respiratory, Neurological, Digestive, Menstrual Pain, Anemia, Rheumatism Treatment | 19 | 20 | decoction | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Mentha spicata L. | Y | النعناع alneana | Leaves, flower | Ear And Throat, Respiratory, Stomach Pain | 10 | 24 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Moringa oleifera Lam. | Y | المورينجا almorenga | Leaves | To Lower The Sugar Level | 2 | 1 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Nasturtium officinaleR.Br. | Y | الجرجير algarger | leaves | Flu | 1 | 0 | fresh | Oral ingestion | |

| Nigella sativa L. | N | الحبه السوداء alhaba alsoda | Seeds | Congestion, Digestive, Expectorant, Immunity Booster, Kidney Disease-Breast | 7 | 10 | With honey and food, juice, powder, infusion, decoction, raw. | Oral ingestion (drink, food), fumigation, chewing. | |

| Olea europaea L. | Y | الزيتون alzeeton | Leaf, Seed, fruit | For Diabetics, Man's Cartilage, Roughness, Skin-Heart Health -Cholesterol-Digestive | 5 | 5 | By heating like tea, fresh, Infusion | Oral ingestion (drink),rub in | |

| Origanum majorana L. | Y | البردقوش albrdaqwsh | Leaves, Seed | Endocrine, Neurological, Digestive, Respiratory | 1 | 3 | decoction | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss | N | البقدونس albaqdunis | Leaves, whole plant | Gallstones, Stomach Pain, Urinary Tract | 7 | 11 | By heating like tea, fresh | Oral ingestion | |

| Pimpinella anisum L. | N | اليانسون alyansun | Seeds, whole plant | Ear And Throat, Digestive, Respiratory, Neurological | 17 | 40 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Piper nigrum L. | Y | فلفل ابيض felfl abid | Seeds | Improve Blood Circulation | 1 | 0 | Crushed | Oral ingestion | |

| plantago ovate L. | N | الاسبقول aliasbiqul | Leaves | Stomach | 1 | 0 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion | |

| Prunus dulcis D.A.Webb. | Y | لوز lwz | Seeds | Immunity Booster | 1 | 0 | Fresh | Oral ingestion | |

| Prunus mahaleb L. | N | المحلب almhalab | seeds | Poor Hair, Headaches | 0 | 2 | powder | Rub in | |

| Psidium guajava L. | N | الجوافة aljwafa | Leaves | Respiratory, Diarrhea, Childbearing | 6 | 14 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Punica granatum L. | N | الرمان alroman | Peel, Fruit | Gastritis, Skin Diseases, Stomach Pain, For Hair | 2 | 7 | By heating like tea, crushed, chaff, juice | Oral ingestion (drink), rubbed on the head | |

| Rhanterium epapposum Oliv. | Y | العرفج alarfag | Fruits, Shins |

Asthma, Joints | 0 | 1 | decoction | Oral ingestion | |

| Rhazya stricta Decne. | Y | حرمل harmel | Seed, Leaves, Roots | Toothache, Colic, Stomach Pain, Cough, Skin | 2 | 5 | Crushed, Add to the juice, decoction | Oral ingestion (drink),Rub in | |

| Ricinus communis L. | Y | زيت الخروع zayt alkharue | seeds | Digestive | 1 | 0 | Fresh oil | Oral ingestion | |

| Salvia hispanica L. | N | بذر الشيا budhur alshya | Seeds | Improve Blood Circulation | 1 | 0 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion | |

| Salvia officinalis L. | N | الميرمية almiramia | Leaf, flowers | Anxiety, Cleans The Womb, Abdominal Pain, Hormonal Problems, Reduce Bleeding | 7 | 6 | By heating like tea, crushed | Oral ingestion | |

| Salvia Rosmarinus Schleid. | N | اكليل الجبل aklil aljabal | Leaves | Digestive, Respiratory, Diuretic, Stimulate Blood Circulation | 1 | 5 | Powder, By heating like tea, inhalation | Oral ingestion | |

| Senna alexandrina Mill. | Y | السنا مكي alsna makiy | Leaves, Whole plant | Digestive, Constipation, Colon Cleaning | 11 | 4 | decoction | Oral ingestion (drink) | |

| Spinacia oleracea L. | N | سبانخ sbankh | Leave | Anemia | 0 | 1 | Fresh | Oral ingestion | |

| Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L.M.Perry. | N | القرنفل alqaranful | Flower buds, Seed | Dental And Periodontal, Digestive, Neurological Nausea, For Hair, Kidney-Organize Shugar In Blood – Gingivitis | 14 | 8 | By heating like tea. Crushed, chaff | Oral ingestion (drink), mouth wash | |

| Tamarindus indica L. | N | التمر الهندي altamr alhindiu | Fruits | Digestive-Reduces Fever | 2 | 0 | By heating like tea, juice | Oral ingestion | |

| Teucrium marum L. | الجعده aljaeduh | Leaves | Stomach Pain | 1 | 0 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion (drink) | ||

| Teucrium marum L. | Y | الجعدة aljaeduh | Leaves | Tummy Ache | 2 | 0 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion | |

| Thymus vulgaris L. | N | الزعتر alzaetar | Leaves, oil | Digestive, Respiratory | 5 | 10 | By heating like tea, crushed | Oral ingestion (drink),rub in | |

| Trachyspermum ammi Sprague | N | النانخة alnaanikha | Seeds, fruit | Stomach, Diarrhea, Flatulence Kidney Stones | 3 | 5 | By heating like tea | Oral ingestion | |

| Tribulus terrestris L. | Y | الشرشر alsharshar | Shins, Leaves | Kidney Stone | 1 | 0 | decoction | Oral ingestion | |

| Trigonella foenum-graecum L. | Y | الحلبة alhalba | seed | Cough, Diarrhea, Urinary Tract, Asthma, Obesity, Strengthen The Bones, Stomach Pain, Reduce Period Pain | 5 | 15 | By heating like tea, crushed, chaff | Oral ingestion (drink, food) | |

| Urtica dioica L. | N | القراص alqaras | flowers | Arthritis | 2 | 0 | Crushed, By heating like tea | Oral ingestion | |

| Vigna radiata (L.) R.Wilczek. | Y | الماش almash | Seeds | Strengthen The Bones | 1 | 1 | crushed | Oral ingestion | |

| Zingiber officinale Roscoe | N | الزنجبيل alzanjanil | Roots, Fruit, stalk | Digestive, Ear And Throat, Respiratory | 26 | 19 | Decoction, infusion, juice, powder, with honey, milk and food | Oral ingestion (drink, food) | |

| Ziziphus spina-christi (L.) Willd | Y | السدر alsudr | Leaves | For Wounds, Digestive, Respiratory, Skin, Magic And Envy, Headaches | 5 | 5 | decoction, infusion, powder, raw |

Oral ingestion (drink), on wound, wash, rub in | |

| Total Of Plants Citation By Gender | 69 | 64 | |||||||

| Citation Depend On Gender Only | 23 | 21 | |||||||

| Common Citation Men + Women | 45 | ||||||||

F: Flora of KSA, V: Vernacular name, Y:Yes , N: No.

3.3. Common diseases in the survey

In this survey, respondents mentioned 88 plant species for the treatment of various diseases, which were divided into 15 main disease classes and categorized as digestive diseases, respiratory diseases, ear and throat diseases, neurologic diseases, dental and periodontal diseases, cardiovascular diseases, skeletal diseases, skin diseases, urologic diseases, reproductive system diseases, endocrine diseases, muscular diseases, pain killers, tonics, and carminatives. The informants used the most plant species (40 species) to treat digestive diseases such as diuretic, gastrointestinal, anti-diarrheal, laxative, colonic, nausea, diarrhea, indigestion, ulcers, and acidity. Respiratory disorders are the second most common categorization of medicinal plants in folk medicine, with 28 plants being used to treat diseases such as asthma, cough, congestion, paranasal sinuses, and bronchitis. Also, fifteen plant species were reported to treat skeletal diseases, whereas 10 plant species were reported for each neurologic disease and cardiovascular disease, as illustrated in (Table 3).

3.4. Participants’ ICF

When both men and women are taken into account, the informant consensus factor (Table 4) shows that people agree most about how to treat ear and throat illnesses, and respiratory diseases, but there is little agreement on how to take medicinal plant as tonic. Heinrich et al. (1998) say that ICF values of 0.68 or more show a high level of consensus. So, most of the populations that have been studied agree on which plants to use for most types of medicine (Teka et al., 2020). There are no ICF differences when considering men's and women's responses separately. So, men and women were had high ICF values (>0,68) for digestive diseases, respiratory diseases, ear and throat diseases, neurologic diseases, dental and periodontal diseases, cardiovascular diseases, skeletal diseases, skin diseases, urologic diseases, reproductive system diseases, endocrine diseases, muscular diseases, pain killers, tonics, and carminatives. (Table 4). The most popular species used by men to treat digestive ailments is Zingiber officinale (26 repetitions), and the most popular species used by women to treat same therapeutic category is Pimpinella anisum (40 repetitions). Ginger and anise are the most common species used by both men and women to treat lung, ear, and throat diseases. Men and women both use mint to treat neurological diseases more than any other plant. Even though ICF is pretty high for women (0.84), it is pretty low for men (0.76), the most common species used by both are Pimpinella anisum, Foeniculum vulgare, Curcuma longa, and Senna alexandrina. The most common species used by both genders is the same, Matricaria aurea. Lastly, the most common species used by both genders in the study areas to treat respiratory and neurological diseases is Matricaria aurea, while for treating oral disorders, gingivitis, and dental pain, the male participants used Syzygium aromaticum more than the females. Other than that, men and women have reached an agreement on how to treat a wide range of disorders.

Table 4.

Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) of traditional medicine plants use by men and women in Makkah and some surrounded villages.

| Categories of Disorders | Men |

Women |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nur | Nt. | Fic | Nur | Nt. | Fic | |

| Digestive diseases | 172 | 40 | 0.76 | 265 | 40 | 0.84 |

| Respiratory diseases | 151 | 28 | 0.81 | 218 | 28 | 0.87 |

| Ear and Throat diseases | 82 | 8 | 0.90 | 110 | 8 | 0.92 |

| Neurologic diseases | 64 | 10 | 0.84 | 92 | 10 | 0.89 |

| Dental & Periodontal diseases | 16 | 4 | 0.75 | 14 | 4 | 0.71 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 35 | 10 | 0.71 | 33 | 10 | 0.69 |

| Skeletal diseases | 58 | 15 | 0.82 | 74 | 15 | 0.86 |

| Skin diseases | 25 | 7 | 0.72 | 33 | 7 | 0.78 |

| Urologic diseases | 33 | 6 | 0.81 | 40 | 6 | 0.85 |

| Reproductive system diseases | 36 | 11 | 0.69 | 35 | 11 | 0.68 |

| Endocrine diseases | 3 | 2 | 0.68 | 5 | 2 | 0.6 |

| Muscular diseases | 9 | 2 | 0.77 | 13 | 2 | 0.84 |

| Pain Killer | 46 | 5 | 0.68 | 70 | 15 | 0.78 |

| Tonic | 15 | 7 | 0.53 | 20 | 7 | 0.65 |

| Carminative | 27 | 5 | 0.81 | 39 | 5 | 0.87 |

Nur: Number of participants, Nt: Number of taxa, Fic: Informant Consensus Factor (ICF = Nur - Nt/Nur).

3.5. Fidelity level of medicinal plants

Top five of high FL value (1 0 0) of frequently used traditional medicinal plants as remedy in Makkah observed for Petroselinum crispum, Lepidium sativum, Citrus sinensis, Salvia Rosmarinus, and Carum carvi, while the lowest FL (25) for Ziziphus spina-christi, and (33.3) for Commiphora myrrha, and Foeniculum vulgare as shown in Table 5. Whereas, for village‘s participants, the high FL value (1 0 0) of frequently used traditional medicinal plants were reside for most species in rate 85.5 %, and the lowest FL (33.3) for Acacia tortilis (Table 6).

Table 5.

Fidelity Level values of frequently used traditional medicinal plants as remedy in Makkah.

| No | Plant Scientific Name | Disorders | LP | LU | FLValue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58 | Agave deserti | For Wounds | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 8 | Allium cepa | Respiratory System, Skeletal System, Skin, Burns | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 19 | Allium sativum | Nervous System, Reproductive System, Pain Relief | 5 | 7 | 71.4 |

| 29 | Aloe vera | Treatment For Hair Loss | 3 | 4 | 75 |

| 44 | Ammi visnaga | Bladder Stones | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 56 | Anastatica hierochuntica | Acceleration Of Childbirth | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 63 | Artemisia judaica | Digestive | 2 | 3 | 66.6 |

| 52 | Beta vulgaris | Anemia | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 49 | Calligonum comosum | Feminine Wash | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 4 | Camellia sinensis | Digestive | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 42 | Camellia sinensis | Digestive | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 36 | Carthamus tinctorius | Depression And Stress Treatment | 3 | 3 | 100 |

| 40 | Carum carvi | Menstrual Pain Relief | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| 62 | Citrullus colocynthis | Hemorrhoids | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 10 | Citrus limon | Digestive, Throat, Fullness, And Fever | 9 | 12 | 75 |

| 9 | Citrus sinensis | Digestive, Throat | 6 | 6 | 100 |

| 57 | Cocos nucifera | Chronic Cough | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 54 | Coffea arabica | Wounds | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 68 | Coleus forskohlii solenostemon | Ear Pain | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 17 | Commiphora myrrha | Respiratory System, Reproductive Hormones, Skin Diseases, Ear, And Throat | 1 | 3 | 33.3 |

| 50 | Commiphora myrrha | Hemorrhoids | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 25 | Commiuphor a myrrha | Superficial Wounds | 3 | 4 | 75 |

| 61 | Cucurbita ficifolia | Prostate Enlargement Plus Childbearing | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 22 | Cuminum cyminum | Digestive | 8 | 9 | 88.88 |

| 18 | Curcuma longa | Nervous System, Reproductive System | 10 | 17 | 58.8 |

| 55 | Cymbopogon | Respiratory, Influenza | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 69 | Eruca sativa | Ful | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 51 | Ferula assa-foetida | Digestive | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 27 | Ficus carica | Treatment Of Blood Pressure And Hemorrhoids | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 2 | Foeniculum vulgare | Digestive System, Respiratory System | 20 | 30 | 66.6 |

| 20 | Foeniculum vulgare | Nervous System, Reproductive System | 1 | 3 | 33.3 |

| 65 | Geum urbanum | Digestive Disorder | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 13 | Hibiscus sabdariffa | Body Tonic That Lowers Blood Pressure | 5 | 6 | 83.3 |

| 12 | Hordeum vulgare | Kidney Disease, Urologist, Carminative | 3 | 3 | 100 |

| 47 | Lawsonia inermis | For Hair to Grow | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 53 | Lens culinaris | Muscular Pain | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 41 | Lepidium sativum | Musculoskeletal System, Bruises | 7 | 7 | 100 |

| 59 | Linum usitatissimum | Lmmunity Booster | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 32 | Malus domestica | Strengthening The Immune System | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 14 | Matricaria aurea | Digestive, Respiratory, Ear And Throat, And Influenza | 22 | 34 | 83.3 |

| 3 | Mentha spicata | Digestive System, Respiratory System, Nervous System, Burns | 18 | 25 | 72 |

| 35 | Nigella sativa | Respiratory System, Expectorant, Protection For The Body, Tonic | 9 | 14 | 64.28. |

| 28 | Olwa europae | Diabetes, Skin Treatment | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| 7 | Origanum syriacum | Respiratory, Endocrine, And Nervous | 4 | 5 | 80 |

| 5 | Petroselinum crispum | Digestive Pain, Gallstones | 9 | 9 | 100 |

| 6 | Pimpinella anisum | Digestive, Nervous, And Respiratory Pain | 31 | 46 | 67.3 |

| 60 | Piper nigrum | Improve Blood Circulation | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 31 | Prunus dulcis | Raising Immunity | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 45 | Prunus mahaleb | Poor Hair | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 33 | Psidium guajava | Respiratory, Digestive | 13 | 16 | 81.2 |

| 11 | Punica granatum | Digestive | 7 | 9 | 77.7 |

| 67 | Rhanterium epapposum | Asthma | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 1 | Rhazya stricta | Digestive | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 37 | Saivia rosmarinus | Blood Circulation Stimulant, Digestive Aid, Diuretic | 6 | 6 | 100 |

| 16 | Salvia officinalis | Respiratory, Reproductive Hormones, Urinary, And Digestive Tract | 13 | 14 | 92.8 |

| 26 | Saussurea costus | Digestive, Respiratory, And Pregnancy Delay | 8 | 11 | 72.7 |

| 43 | Sengalia Senegal | Gastrointestinal And Digestive Systems | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 34 | Senna alexandrina | Digestive | 11 | 11 | 100 |

| 46 | Spinacia oleracea | Anemia | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| 21 | Syzygium aromaticum | Nervous System, Reproductive System, Teeth, Gums, Heart, And Blood Vessels | 13 | 18 | 72.2 |

| 30 | Teucrium marum | Digestive | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 38 | Thymus vulgaris | Respiratory, Digestive Systems | 8 | 9 | 88.8 |

| 64 | Trachyspermum ammi | Digestive | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 23 | Trigonella foenum-graecum | Digestive | 8 | 9 | 88.88 |

| 39 | Urtica dioica | Arthritis | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 66 | Vigna radiata | Joints And Bones | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 15 | Zingiber officinale | Digestive System, Respiratory System, Skin Diseases, Influenza, Throat | 29 | 38 | 76.3 |

| 48 | Ziziphus spina-christi | Dandruff | 1 | 4 | 25 |

LP: respondents number used medicinal plants for a specific disease, LU: the number of respondents used same plant for any disease, FL = Ip/Iu × 100.

Table 6.

Fidelity Level values of frequently used traditional medicinal plants as remedy in Villages.

| No | Plant Scientific Name | Disorders | LP | LU | FLValue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | acacia ampliceps | Body tonic | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 37 | Acacia Senegal | Treatment for Kidney Diseases as well as Dental and Gum Diseases | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 54 | Acacia Senegal | Periodontal or Kidney Treatment | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 52 | Acacia tortilis | Put a stop to the bleeding. | 1 | 3 | 33.3 |

| 45 | Aerva javanica | Diabetic, diuretic | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 60 | Alkanna tinctoria | Reproductive System | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 43 | Alove Vera | Respiratory | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 58 | Anethum graveolens | Diarrhea | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 41 | Anisosciadium lanatum | Digestive | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 49 | Astragalus sarcocolla | Digestive | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 53 | Boswellia sacra | Respiratory | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 44 | Calotropis Gigantea | Wounds | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 17 | Camellia sinensis | Digestive | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 35 | Camellia sinensis | Digestive | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 21 | Carthamus tinctorius | Diseases of the nervous system | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 13 | Carum carvi | Digestive | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 32 | Cassia angustifolia | Reproductive System, Digestive System | 3 | 3 | 100 |

| 11 | Cinnamomum verum | Reproductive system; diseases of the reproductive system | 3 | 3 | 100 |

| 30 | Citrus × sinensis | Body tonic | 3 | 3 | 100 |

| 20 | Citrus limon | Throat disorders; a body tonic | 6 | 10 | 60 |

| 29 | Coffea arabica | Digestive | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 51 | Commiphora gileadensis | for burn injuries | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| 5 | Cuminum cyminum | Digestive | 3 | 3 | 100 |

| 1 | Curcuma longa | Skeleton, carminative, and body tonic | 3 | 4 | 75 |

| 61 | Cydonia oblonga | Digestive | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 14 | Cymbopogon schoenanthus | Nervous system, respiratory, ear, and throat | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| 23 | Elettaria cardamomum | Gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 47 | Ferula assa- foetida | Asthma, Sore Throat, and Respiratory System | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 40 | Frangula alnus | Digestive | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 39 | Garden cress | Alhaykal Aleazmiu | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 57 | Glycyrrhiza glabra | Respiratory | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 42 | Haloxylon salicornicum | Muscular pain and bones | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 6 | Hibiscus sabdariffa | Ear and throat diseases | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 25 | Lawsonia inermis | Diseases of the nervous system | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 48 | Leptadenia pyrotechnica | Cough Worms | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 55 | Linum usitatissimum | Neurologic | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 16 | Matricaria aurea | Gastrointestinal, nervous system, and respiratory | 5 | 7 | 71.4 |

| 9 | Mentha spicata | body tonic, respiratory system, digestive system, ear, and throat | 8 | 12 | 66.6 |

| 18 | Moringa oleifera | Digestive | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 27 | Nigella sativa | Body tonic | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 36 | Nigella sativa | Digestive | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 28 | Olea europaea | Skeletal diseases, skin diseases, and lowering the level of sugar | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 33 | Origanum majorana | Pco (Polycystic Ovary) | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 46 | Petroselinum crispum | Gallstones | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 12 | Pimpinella anisum | Diseases of the digestive, nervous, digestive, and tonic systems | 10 | 12 | 83.3 |

| 3 | plantago ovate | Gastrointestinal, carminative, and nervous systems | 5 | 5 | 100 |

| 26 | Prunus mahaleb | Diseases of the nervous system | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 10 | Psidium guajava | Respiratory, Ear and Throat, and Gastrointestinal | 7 | 7 | 100 |

| 38 | Punica granatum | Body Tonic | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 15 | Razhya stricta | digestive and respiratory systems | 5 | 5 | 1000 |

| 56 | Salvia hispanica | Cardiovascular | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 59 | Salvia officinalis | Diarrhe | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 34 | Spinach oleracea | Anemia | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 31 | Syzygium aromaticum | Gum and skin diseases | 7 | 10 | 70 |

| 7 | Tamarindus indica | Digestive | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 2 | Thymus vulgaris | Respiratory, anti-cold, and digestive | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| 4 | Trachyspermum ammi | Digestive | 3 | 3 | 100 |

| 50 | Tribulus terrestris | Kidney Stone | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 22 | Trigonella foenum-graecum | Diseases of the digestive system, tonic for the body, urinary tract | 9 | 12 | 75 |

| 62 | Vulgare hordeum | Urologic | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| 19 | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Tonic for the body; ear and throat diseases | 7 | 8 | 87.5 |

| 24 | Ziziphus spina-christi | Diseases of the allergic nervous system | 2 | 2 | 100 |

LP: respondents number used medicinal plants for a specific disease, LU: the number of respondents used same plant for any disease, FL = Ip/Iu × 100.

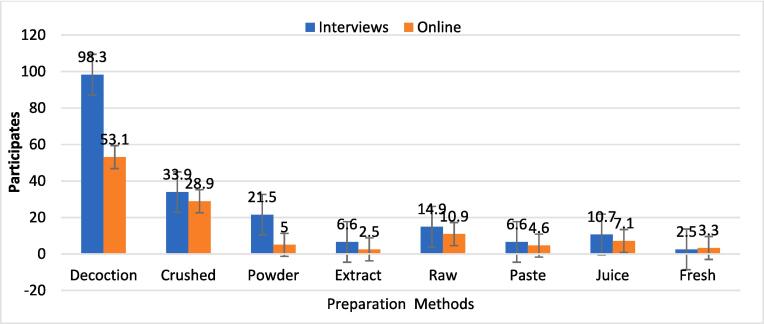

3.6. Preparation of ethnomedicines

For the preparation of ethnomedicines the Interviews participants (face to face) used leaves (66.1 %), stems (18.2 %), peel (5.8 %), roots (20.7 %) flowers (11.6 %), seeds (61.2 %), fruits 27.3 %), gum (12.4 %), and whole plant (36.4 %), the average number of ethno-species listed were 37.3, 12.7, 2.0, 8.7, 8.3, 35.0, 12.3, 7.7, 16.7 % respectively (Table 1, Table 2) and (Fig. 2). For Online questionnaire the most plant parts used were leaves and seeds (45.2, 30.5 %) and the lowest is peel (2.5 %). Out of total recipes preparation decoction was observed (98.3 %), Crushed (33.9 %), powder (21.5 %), extract (6.6 %) and Paste (6.6 %), Juice (10.7 %), and fresh (2.5 %) as shown in (Table 1, Table 2) and (Fig. 3). Also, the average number of preparation method either decoction, crushed, powder, extract, paste, juice, or fresh were 57.3, 13.0, 17.3, 1.7, 2.7, 6.3, 1.0 % respectively from face to face interviews. Furthermore, the Online questionnaire, the decoction and crushed were most preparation method used with the average number of ethno-species (36.1, 16.6 %) respectively.

Fig. 2.

Most plant part used ethnomedicine in Makkah and surrounded villages for Interviews and online questionnaire.

Fig. 3.

Preparation of medicinal plants for using in ethnomedicine in Makkah and surrounded villages for Interviews and online questionnaire.

3.7. Route of administration and dosage

The route of administration for ethnomedicines was mostly observed orally, with additives like sugar, milk, and juice. There was no set dosage, as there is with modern medicines, but they were administered based on disorder and need. Ethnomedicines were used with teaspoons and fingertips, which were passed from generation to generation. Some elderly people were observed who regularly used ethnomedicines in crushed form for many disorders.

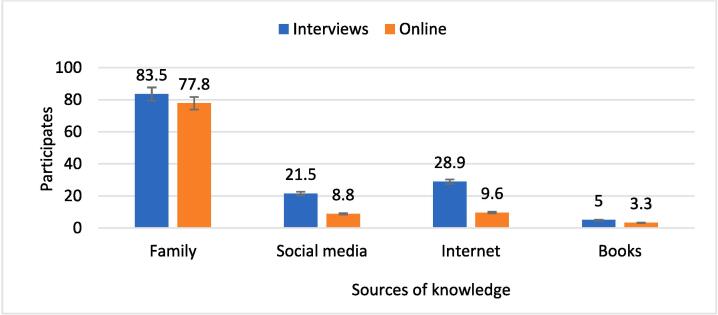

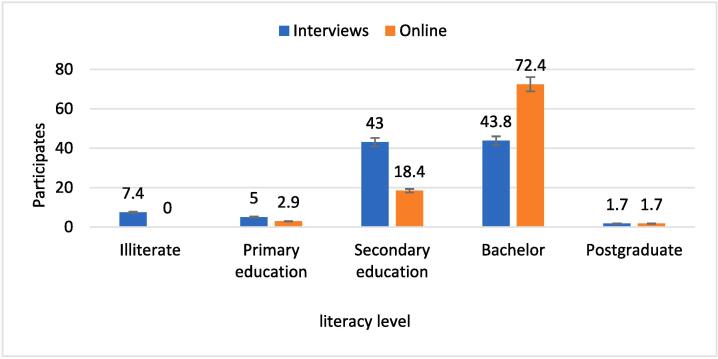

3.8. Gender, age classes, literacy level, and occupation

The average number of ethno-species used by men and women in online questionnaires and face-to-face interviews for many variables and demographic descriptors. Out of 121 face-to-face informants, 58 were male and 63 were female (Table 1). Females (70.2 %) were more knowledgeable than males (68.6 %). Saudis in Makkah learned about medicinal plants from family (83.5 %), social media (21.5 %), the internet (28.9 %), and books (5.0 %). The online questionnaire yielded different rating results for knowledge, but the basic source of experience is still family (778.%) as shown in Fig. 4. Age-wise, the informants were observed in several categories in the range of 25 to 75 years, as shown in Table 1. The age groups 25–34 and 35–44 years were most represented in the interview section (29.8 and 27.3 %, respectively), whereas less than 25 years and 35–44 years were more likely to respond to questions in the questionnaire. According to literacy level of interviews participates were illiterate (7.4 %), Primary education (5.0 %), Secondary education (43.0 %), Bachelor (43.8 %), and Postgraduate (1.7 %) (Table 1). It was observed that percentage of illiterate literate people had less knowledge for number of ethno-species in folk medicine (5.3 %) than those of literate people (95 %). But totally for Online questionnaire were literate peoples (Fig. 5). Contrary to what we expected, the number of plants cited by both men and women did not increase with age, nor with the presence of children or people living in the house shared with the informants.

Fig. 4.

The sources of medicinal plants knowledge mentioned by male and female in Makkah and surrounded villages for interviews and online questionnaire.

Fig. 5.

literacy level of participates of interviews and online questionnaire in Makkah and surrounded villages.

3.9. Cure-type preferences

As seen in Tables S1, S2 in the appendix and Table 7 below, the types of cures that people like can lead to differences in how much they know. The number of medicinal plants mentioned is inversely related to how much people like biomedicine. This is true for both men and women, and it is statistically significant. Also, men who say they prefer using medicinal plants list a lot more of them. In general, both men and women seemed to prefer using medicinal plants over biomedicine. Most men (76, 33.8 %) used both medicinal plants and biomedicine, but 19 (11.8 %) preferred biomedicine and 92 (52.5 %) preferred using medicinal plants. Some of the women (54, or 30 %) liked to use both medicinal plants and biomedicine. Another 108 (or 50 %) liked to use medicinal plants instead of biomedicine, and only 19 (19.3 %) liked biomedicine. When sick, most men and women would first try to heal themselves with plants. Men would only use them to treat minor illnesses and would go to a doctor if the illness lasted more than three days, if their body temperature was high, or if the pain got worse. Women would wait longer to see a doctor if they had a disease that lasted for a week or more, if it was hard to find the cause, or if the disease was serious or chronic.

Table 7.

Preferences for the cure kind in the light gender.

| Gender | Total of Informants | Preferable cure-type |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP |

AM |

Bothe |

||||||||

| no. | % | N | no. | % | N | no. | % | N | ||

| F | 62 | 31 | 50.0B | 108 | 12 | 19.3A | 28 | 19 | 30.6B | 54 |

| M | 59 | 31 | 52.5B | 92 | 7 | 11.8 A | 19 | 20 | 33.8B | 76 |

M/F = Male/Female, MP/AM = Medicinal Plants/Allopathic Medicine, N: plants listed, A p < 0.05, level of significance ≤ 0.01 of root growth inhibition compared with negative control; B p < 0.05, level of significance ≤ 0.05 of root growth inhibition compared with negative control.

4. Discussion

The study is linked to (Newing, 2010, Amar and Lev, 2017), who discussed ethnomedical knowledge in relation to many variables for men and women in urban and rural for the future of traditional medicine. According to (Deeba, 2009; Nisar et al., 2017), who uses crushing, decoction, and grinding techniques for active compound extraction, the method of plant preparation for traditional medicine by crushing and decoction of plant species for ethnomedicines may show promising results (Abubakar and Haque, 2020). The various plant species were used in single, combined, fresh, and dried forms. Our findings agree with (Khan et al., 2014, Alqahtani et al., 2013, Alexiades and Sheldon, 1996, Abubakar and Haque, 2020). Informants, on the other hand, use herbal medications that have undergone crushing and decoction to get results quickly. Also, regarding plant species used in the cure of health disorders that were categorized into groups, depending on the treatment, plants with a high ICF value can be considered more pharmacologically active as compared to plants with a low ICF value. FIC values will be high if most informants acknowledge the use of one or a few plants to treat a specific disease (Canales et al., 2005, Jafarirad and Rasoulpour, 2019). Based on different ethnobotanical indices, the potential plant candidates for discovering new drugs are Zingiber officinale, Pimpinella anisum, Foeniculum vulgare, Curcuma longa, Senna alexandrina, Matricaria aurea, Petroselinum crispum, Lepidium sativum, Citrus sinensis, Salvia Rosmarinus and Carum carvi.

Plants of the Fabaceae, Apiaceae, and Lamiaceae (most commonly cited families) which agree with findings of previous studies by (Alqethami et al., 2017, Trotter and Logan, 1986)., Zingiberaceae, and Brassicaceae are important families. Those families are regularly used, reflecting the influence of historical herbal trade in remediations (Amar and Lev, 2017). Since ancient times, several plants, such as Syzygium aromaticum, Curcuma longa, and Zingiber officinale, have been brought into the Roman world via the Arabian Peninsula (Van Der Veen and Morales, 2015). Additionally, a lot of the described medicinal plants are spices, which have chemical properties that make them desirable medicinal plants. These plants are particularly rich in phytochemical compounds, of which only small amounts are needed for a medicinal effect, facilitating early long-distance trade (Van Der Veen and Morales, 2015). Spices were shipped through ports whose principal purpose was to assist this type of trade. These ports also served as food transfers to Makkah region. Additionally, a third of the therapeutic plants utilized in this region are food plants, which is congruent with data from Makkah (Alqethami et al., 2017). In this study, onion, orange, lemon, and olive are cited as prominent edible plants (Table 3). The widespread use of food plants as medicinal products by the urban population (Vandebroek and Balick, 2012) may be the result of easy access to these plants. The widespread medicinal use of spices and foods in cities may be a global characteristic of urban ethnobotanical knowledge, as these are readily available even in rural environments (Alqethami et al., 2017). In addition to herbs and food plants, a significant number of medicinal plants reported in this study are mentioned in the narratives of the Prophet's life, demonstrating the extensive influence of prophetic medicine in Makkah region. e. g., Nigella sativa, Senna alexandrina, Trigonella foenumgraecum, and Foeniculum vulgare plants (Alqethami et al., 2017, El-Seedi et al., 2019, Khan and Khatoon, 2008). Consequently, local medicine may also be affected by religious factors.

Not Men, as expected, use fewer medicinal plants than women, but their knowledge of them appears to be equal, and the plants used are nearly identical. For instance, almost every plant known to men was also known to women. Second, the most common therapeutic plants are the same for many ailments. Although it was expected that the women would have an increased number and variety of plants listed due to their roles as housewives and primary family care as mentioned in many studies(Torres-Avilez et al., 2016, Amar and Lev, 2017) but the knowledge of men and women was extremely close. Some of the mixtures mentioned by informants are combinations of plants usually eaten as vegetables or tonics (Table S3). It is well known that some plant mixtures work better as medicines than their individual parts, and that the right drug combination can help treat many diseases that have more than one cause, like cancer and heart disease (Gras et al., 2018).

Men and women appear to understand and use plants in similar ways in crucial aspects. Traditional medical plant knowledge relates to a variety of experiences passed down from generation to generation (Díaz-Reviriego et al., 2016; Jamshidi-Kia et al., 2017; Costa et al., 2021). It was discovered that information transmission occurs in the study area not just through friends and family, the internet, and social media but also from relatives to others. These findings agree with those from other Arabian cities (Alqethami et al., 2017). After family, social media and the Internet are the most often mentioned knowledge sources. Face-to-face interviews helped us understand that when a social network is unavailable, men and women turn to websites with comparable content. Men's and women's knowledge, however, does not appear to rise with age and appears to be more influenced by advances in media and information technology.

On the other hand, some current research indicates that traditional and modern medicine can be practiced simultaneously in the Arabian Peninsula, or if one fails, the other will be attempted, but when modern medicine is successful, traditional medicine tends to fade (Tounekti et al., 2019). The current study notes that much fewer plants are known by both men and women who choose biomedicine. Saudis in Makkah, like Saudis in other urban centers, still treat minor illnesses at home. Finally, the using of medicinal plants is still a big part of urban health care (Teixidor-Toneu et al., 2017).

5. Conclusion

Among Saudis in Makkah, medicinal plants play a major role in healthcare. Historical, economic, and religious considerations seem to affect both the variety of medicinal plants used in folk medicine and the methods in which they are administered. Both men and women practice traditional medicine in Makkah. However, the findings of the present study reveal that folk medicine is mainly practiced by middle-aged men and women, as well as by those individuals who demonstrate a strong interest in using medicinal plants. Men are familiar with a subset of the plants that women utilize, and vice versa, maybe as a result of learning from the same online and social media sources. Numerous medicinal plants are also used as vegetables, fruits, grains, oils, and spices. So, in the era of information technology, gender and urban issues must always be considered when conducting ethnopharmacological research in different cultures.

Funding

This work was supported by Deanship of Scientific Research at Umm Al-Qura University (Grant Code: 22UQU4281560DSR13).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sameer H. Qari: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Afnan Alqethami: Formal analysis, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Alaa T. Qumsani: Formal analysis, Investigation, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Umm Al-Qura University for supporting this work through Grant Code (22UQU4281560DSR13). The author would also like to thank the graduate project group, Bandar Al-Hasnani, Nawaf Al-Salami, Abdullah Al-Shanbari, Yasser Al-Hasani, Salem Al-Harbi, Muhammad Al-Harbi, Ziyad Al-Bishri, and Abdul Rahman Al-Harbi, for their assistance in data collection.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.101881.

Contributor Information

Sameer H. Qari, Email: shqari@uqu.edu.sa.

Afnan Alqethami, Email: amqethami@uqu.edu.sa.

Alaa T. Qumsani, Email: atqumsani@uqu.edu.sa.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Aati H., El-Gamal A., Shaheen H., Kayser O. Traditional use of ethnomedicinal native plants in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0263-2. https://ethnobiomed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13002-018-0263-2 [accessed 26 Feb 2023] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas B., Al-Qarawi A.A., Al-Hawas A. The ethnoveterinary knowledge and practice of traditional healers in Qassim Region, Saudi Arabia. J. Arid Environ. 2002;50(3):367–379. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Sattar E., Abou-Hussein D., Petereit F. Chemical Constituents from the Leaves of Euphorbia ammak Growing in Saudi Arabia. Pharmacognosy Research. 2015;7(1):14–17. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.147136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25598629/ [accessed 11 Mar 2023] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar A.R., Haque M. Preparation of Medicinal Plants: Basic Extraction and Fractionation Procedures for Experimental Purposes. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2020;12(1), 1 doi: 10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_175_19. [accessed 27 Feb 2023] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Kazman B.S. “Exploration of Some Medicinal Plants Used in Saudi Arabia and Their Traditional Uses”. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research. 2021;39(5) [Google Scholar]

- Alamgeer P., Ahmad T., Rashid M., Nasir M., Malik H., Mushtaq M.N., Khan J., Qayyum R., Khan A.Q., Muhammad N. Ethnomedicinal Survey of plants of Valley Alladand Dehri, Tehsil Batkhela, District Malakand, Pakistan. International Journal of Basic Medical Sciences and Pharmacy (IJBMSP) 2013;3(1):2049–4963. http://www.ijbmsp.org/index.php/IJBMSP/article/view/31 [accessed 11 Mar 2023] [Google Scholar]

- Alexiades M.N., Sheldon J.W. ‘selected Guidelines for Ethnobotanical Research: a Field Manual’, Advances in Economic Botany. 1996;USA), 306 https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=US9631200 [accessed 11 Mar 2023] [Google Scholar]

- Ali H., Sannai J., Sher H., Rashid A. Ethnobotanical profile of some plant resources in Malam Jabba valley of Swat, Pakistan. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2011;5(18):4676–4687. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani A., Hamid K., Kam A., Wong K.H., Abdelhak Z., Razmovski-Naumovski V., Chan K., Li K.M., Groundwater P.W., Li G.Q. The Pentacyclic Triterpenoids in Herbal Medicines and Their Pharmacological Activities in Diabetes and Diabetic Complications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013;20(7):908–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alqethami A., Aldhebiani A.Y. Medicinal plants used in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: Phytochemical screening. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2021;28(1), 805 doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.11.013. https://pmc/articles/PMC7783804/ [accessed 26 Feb 2023] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alqethami A., Hawkins J.A., Teixidor-Toneu I. Medicinal plants used by women in Mecca: Urban, Muslim and gendered knowledge. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017;13(1):1–24. doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0193-4. https://ethnobiomed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13002-017-0193-4 [accessed 11 Mar 2023] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alqethami A., Aldhebiani A.Y., Teixidor-Toneu I. Medicinal plants used in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A gender perspective. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020;257 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amar Z., Lev E. Arabian Drugs in Early Medieval Mediterranean Medicine. Arabian Drugs in Early Medieval Mediterranean Medicine. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Asiimwe S., Namukobe J., Byamukama R., Imalingat B. ‘Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plant species used by communities around Mabira and Mpanga Central Forest Reserves, Uganda’, Tropical. Med. Health. 2021;49(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s41182-021-00341-z. https://tropmedhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41182-021-00341-z [accessed 27 Feb 2023] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awadh Ali N., Al Sokari S., Gushash A., Anwar S., Al-Karani K., Al-Khulaidi A. Ethnopharmacological Survey of Medicinal Plants in Albaha Region, Saudi Arabia. Pharmacognosy Research. 2017;9(4), 401 doi: 10.4103/pr.pr_11_17. [accessed 26 Feb 2023] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayounis A., Eldamaty T. Applying Geographic Information System (GIS) for Solar Power Plants Site Selection Support in Makkah. Technol. Invest. 2022;13(02):37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Betthauser K., Pilz J., Vollmer L.E. Use and effects of cannabinoids in military veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2015;72(15):1279–1284. doi: 10.2146/ajhp140523. https://academic.oup.com/ajhp/article/72/15/1279/5111382 [accessed 11 Mar 2023] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonini S.A., Premoli M., Tambaro S., Kumar A., Maccarinelli G., Memo M., Mastinu A. Cannabis sativa: A comprehensive ethnopharmacological review of a medicinal plant with a long history. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;227:300–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boy H.I.A., Rutilla A.J.H., Santos K.A., Ty A.M.T., Yu A.I., Mahboob T., Tangpoong J., Nissapatorn V. Recommended Medicinal Plants as Source of Natural Products: A Review. Digital Chinese Medicine. 2018;1(2):131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bruschi P., Sugni M., Moretti A., Signorini M.A., Fico G. Children’s versus adult’s knowledge of medicinal plants: an ethnobotanical study in Tremezzina (Como, Lombardy, Italy) Revista Brasileira De Farmacognosia. 2019;29(5):644–655. [Google Scholar]

- Canales M., Hernández T., Caballero J., Romo De Vivar A., Avila G., Duran A., Lira R. Informant consensus factor and antibacterial activity of the medicinal plants used by the people of San Rafael Coxcatlán, Puebla, México. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97(3):429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.11.013. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15740877/ [accessed 2 Apr 2023] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]