Abstract

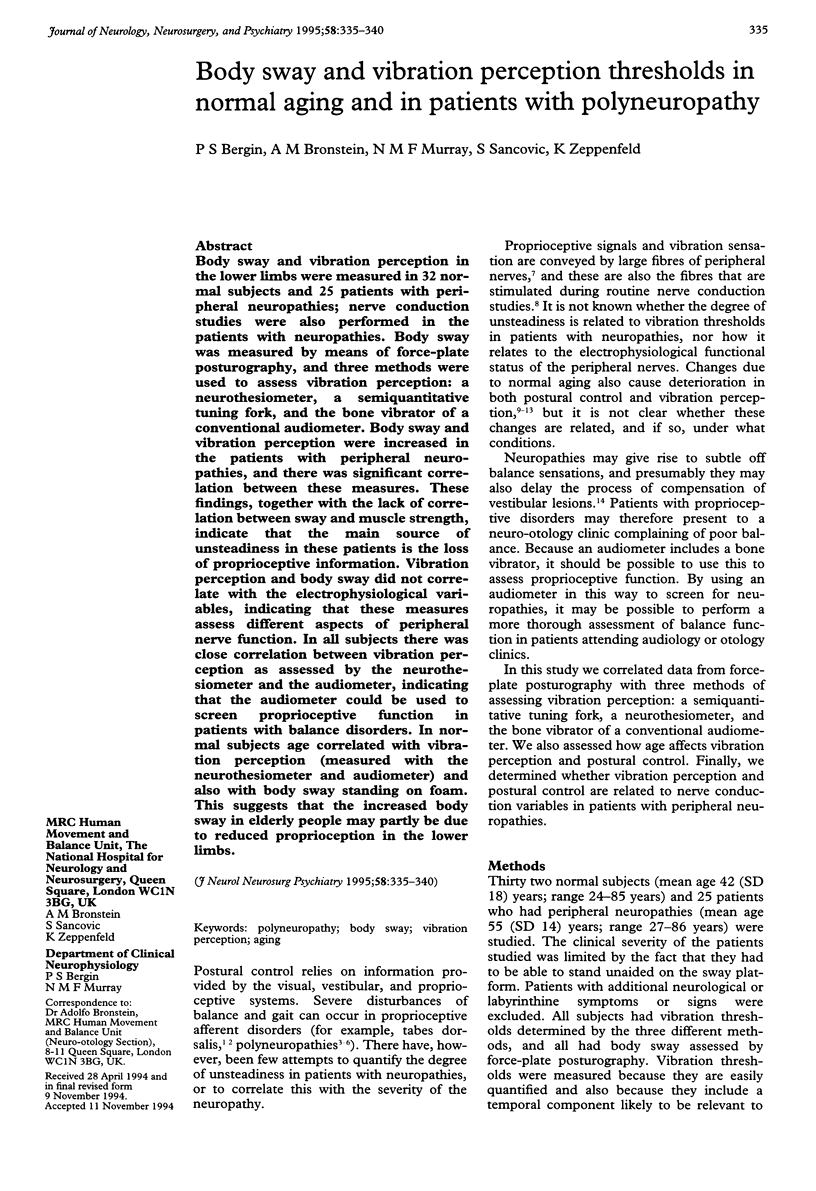

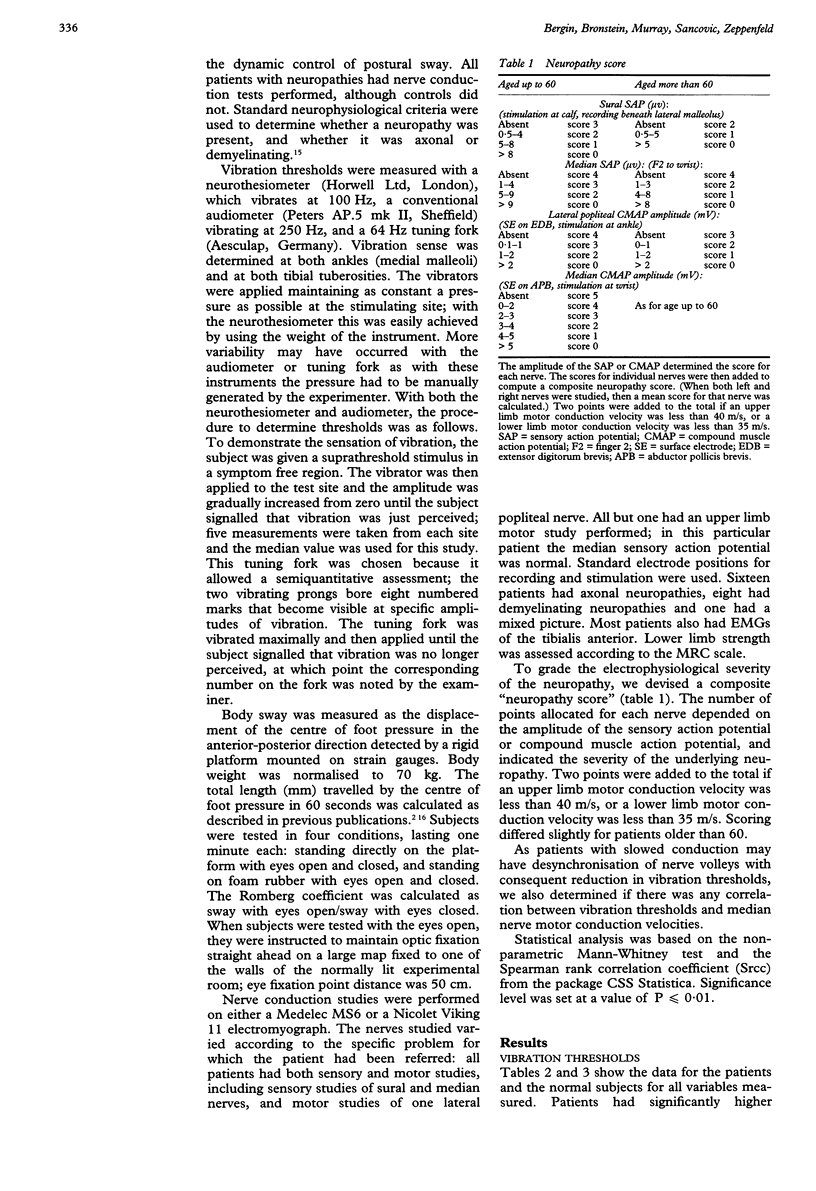

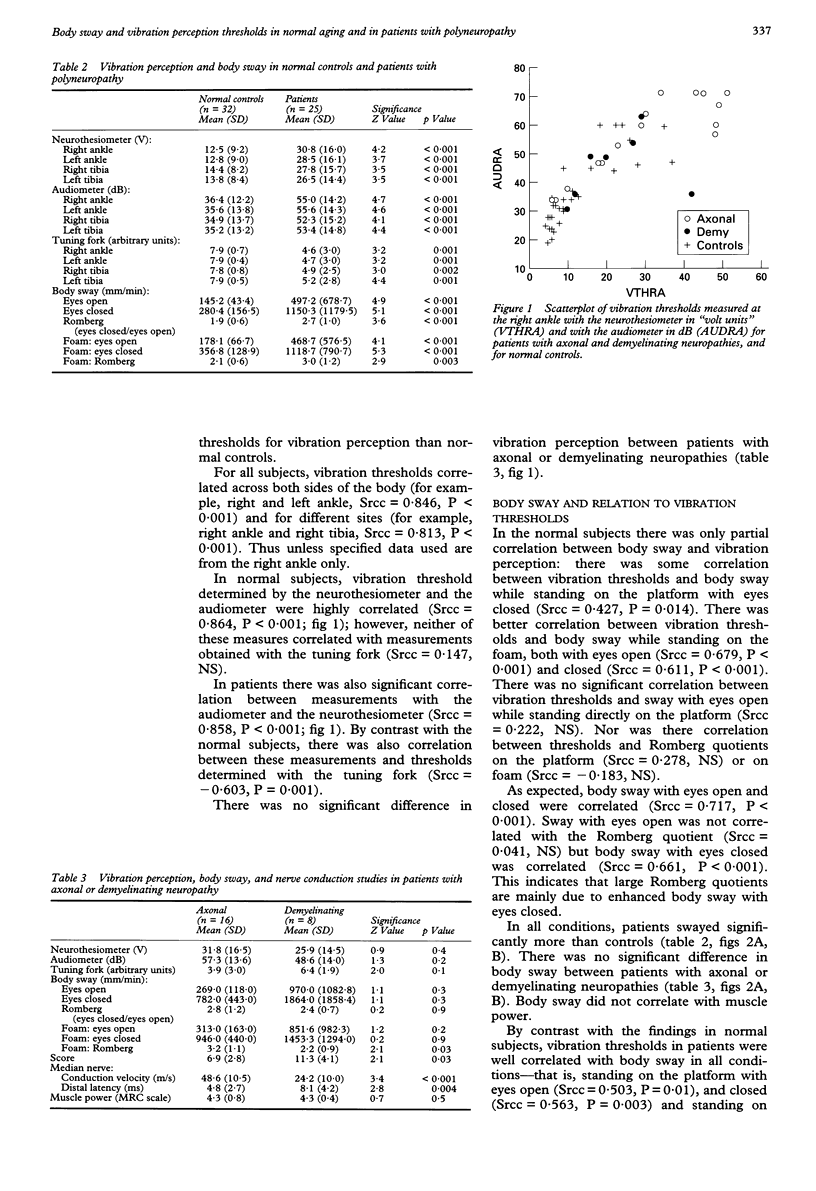

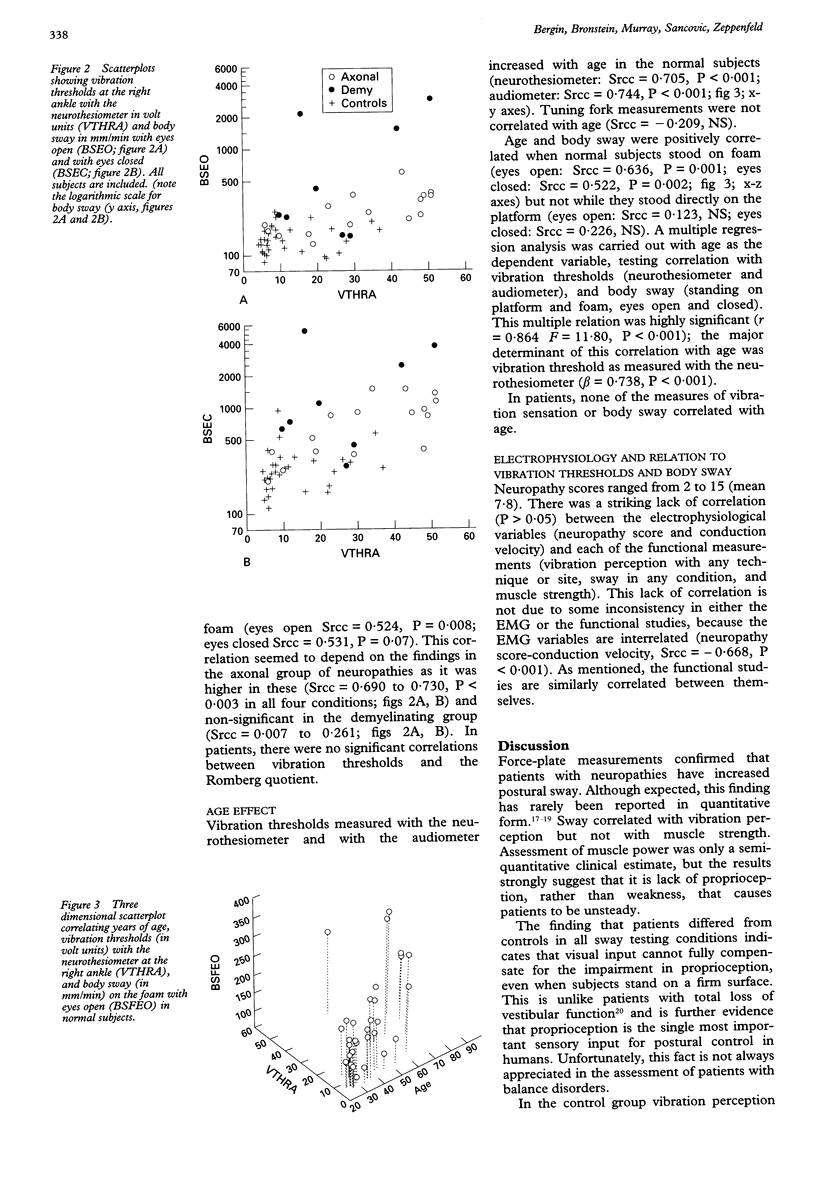

Body sway and vibration perception in the lower limbs were measured in 32 normal subjects and 25 patients with peripheral neuropathies; nerve conduction studies were also performed in the patients with neuropathies. Body sway was measured by means of force-plate posturography, and three methods were used to assess vibration perception: a neurothesiometer, a semiquantitative tuning fork, and the bone vibrator of a conventional audiometer. Body sway and vibration perception were increased in the patients with peripheral neuropathies and there was significant correlation between these measures.d These findings, together with the lack of correlation between sway and muscle strength, indicate that the main source of unsteadiness in these patients is the loss of proprioceptive information. Vibration perception and body sway did not correlate with the electrophysiological variables, indicating that these measures assess different aspects of peripheral nerve function. In all subjects there was close correlation between vibration perception as assessed by the neurothesiometer and the audiometer could be used to screen proprioceptive function in patients with balance disorders. In normal subjects age correlated with vibration perception (measured with the neurothesiometer and audiometer) and also with body sway standing on foam. This suggests that the increased body sway in elderly people may partly be due to redue proprioception in the lower limbs.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Black F. O., Wall C., 3rd, Nashner L. M. Effects of visual and support surface orientation references upon postural control in vestibular deficient subjects. Acta Otolaryngol. 1983 Mar-Apr;95(3-4):199–201. doi: 10.3109/00016488309130936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom S., Till S., Sönksen P., Smith S. Use of a biothesiometer to measure individual vibration thresholds and their variation in 519 non-diabetic subjects. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Jun 16;288(6433):1793–1795. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6433.1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein A. M. Suppression of visually evoked postural responses. Exp Brain Res. 1986;63(3):655–658. doi: 10.1007/BF00237488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donofrio P. D., Albers J. W. AAEM minimonograph #34: polyneuropathy: classification by nerve conduction studies and electromyography. Muscle Nerve. 1990 Oct;13(10):889–903. doi: 10.1002/mus.880131002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman L. J. The distribution of conduction velocities (DCV) in peripheral nerves: a review. Muscle Nerve. 1984 Jan;7(1):2–11. doi: 10.1002/mus.880070103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drachman D. A., Hart C. W. An approach to the dizzy patient. Neurology. 1972 Apr;22(4):323–334. doi: 10.1212/wnl.22.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin J. W., Cornblath D. R., Alexander E., Campbell J., Low P. A., Bird S., Feldman E. L. Ataxic sensory neuropathy and dorsal root ganglionitis associated with Sjögren's syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990 Mar;27(3):304–315. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding A. E., Thomas P. K. The clinical features of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy types I and II. Brain. 1980 Jun;103(2):259–280. doi: 10.1093/brain/103.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hufschmidt A., Dichgans J., Mauritz K. H., Hufschmidt M. Some methods and parameters of body sway quantification and their neurological applications. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr (1970) 1980;228(2):135–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00365601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollegger H., Baumgartner C., Wöber C., Oder W., Deecke L. Spontaneous body sway as a function of sex, age, and vision: posturographic study in 30 healthy adults. Eur Neurol. 1992;32(5):253–259. doi: 10.1159/000116836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledin T., Odkvist L. M., Vrethem M., Möller C. Dynamic posturography in assessment of polyneuropathic disease. J Vestib Res. 1990 1991;1(2):123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchut M. P., Toleikis S. C. Aging and quantitative sensory thresholds. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1990 Aug-Sep;30(5):293–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEINBERG F. U., GRABER A. L. THE EFFECT OF AGE AND PERIPHERAL CIRCULATION ON THE PERCEPTION OF VIBRATION. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1963 Dec;44:645–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solders G., Andersson T., Borin Y., Brandt L., Persson A. Electroneurography index: a standardized neurophysiological method to assess peripheral nerve function in patients with polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 1993 Sep;16(9):941–946. doi: 10.1002/mus.880160909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterman A. B., Schaumburg H. H., Asbury A. K. The acute sensory neuronopathy syndrome: a distinct clinical entity. Ann Neurol. 1980 Apr;7(4):354–358. doi: 10.1002/ana.410070413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrethem M., Ledin T., Ernerudh J., Odkvist L., Holmgren H., Möller C. Correlation between dynamic posturography, clinical investigation, and neurography in patients with polyneuropathy. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1991;53(5):294–298. doi: 10.1159/000276232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles P. G., Pearce S. M., Rice P. J., Mitchell J. M. Vibration perception threshold: influence of age, height, sex, and smoking, and calculation of accurate centile values. Diabet Med. 1991 Feb-Mar;8(2):157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1991.tb01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]