Key Points

Question

Is the de-escalation strategy of switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel after 1 month of percutaneous coronary intervention suitable for patients with acute myocardial infarction with high ischemic risk?

Findings

In this post hoc analysis of the Ticagrelor vs Clopidogrel in Stabilized Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction (TALOS-AMI) randomized clinical trial, 1371 patients (50.8%) were classified as having high ischemic risk. Compared with ticagrelor-based dual antiplatelet therapy, the ischemic and bleeding outcomes of an unguided de-escalation strategy were consistent regardless of the presence of high ischemic risk features, with no heterogeneity.

Meaning

The findings suggest that the de-escalation strategy is a safe and reasonable option following myocardial infarction in patients with high ischemic risk.

Abstract

Importance

In patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) who have high ischemic risk, data on the efficacy and safety of the de-escalation strategy of switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel are lacking.

Objective

To evaluate the outcomes of the de-escalation strategy compared with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with ticagrelor in stabilized patients with AMI and high ischemic risk following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a post hoc analysis of the Ticagrelor vs Clopidogrel in Stabilized Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction (TALOS-AMI) trial, an open-label, assessor-blinded, multicenter, randomized clinical trial. Patients with AMI who had no event during 1 month of ticagrelor-based DAPT after PCI were included. High ischemic risk was defined as having a history of diabetes or chronic kidney disease, multivessel PCI, at least 3 lesions treated, total stent length greater than 60 mm, at least 3 stents implanted, left main PCI, or bifurcation PCI with at least 2 stents. Data were collected from February 14, 2014, to January 21, 2021, and analyzed from December 1, 2021, to June 30, 2022.

Intervention

Patients were randomly assigned to either de-escalation from ticagrelor to clopidogrel or ticagrelor-based DAPT.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Ischemic outcomes (composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, ischemia-driven revascularization, or stent thrombosis) and bleeding outcomes (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding) were evaluated.

Results

Of 2697 patients with AMI (mean [SD] age, 60.0 [11.4] years; 454 [16.8%] female), 1371 (50.8%; 684 assigned to de-escalation and 687 assigned to ticagrelor-based DAPT) had high ischemic risk features and a significantly higher risk of ischemic outcomes than those without high ischemic risk (1326 patients [49.2%], including 665 assigned to de-escalation and 661 assigned to ticagrelor-based DAPT) (hazard ratio [HR], 1.74; 95% CI, 1.15-2.63; P = .01). De-escalation to clopidogrel, compared with ticagrelor-based DAPT, showed no significant difference in ischemic risk across the high ischemic risk group (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.54-1.45; P = .62) and the non–high ischemic risk group (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.33-1.28; P = .21), without heterogeneity (P for interaction = .47). The bleeding risk of the de-escalation group was consistent in both the high ischemic risk group (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.37-1.11; P = .11) and the non–high ischemic risk group (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.24-0.75; P = .003), without heterogeneity (P for interaction = .32).

Conclusions and Relevance

In stabilized patients with AMI, the ischemic and bleeding outcomes of an unguided de-escalation strategy with clopidogrel compared with a ticagrelor-based DAPT strategy were consistent without significant interaction, regardless of the presence of high ischemic risk.

This post hoc analysis of the Ticagrelor vs Clopidogrel in Stabilized Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction (TALOS-AMI) randomized clinical trial investigates the efficacy and safety of the de-escalation strategy of switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel vs dual antiplatelet therapy with ticagrelor in stabilized patients with acute myocardial infarction and high ischemic risk.

Introduction

In patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) plays a crucial role in minimizing the risk of recurrent ischemic events.1,2,3 Current guidelines1,2,3 recommend DAPT, a combination of aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor, preferably ticagrelor or prasugrel, for at least 12 months after AMI.4,5 However, the efficacy of this treatment is achieved at the expense of an increased risk of bleeding. The benefit of potent P2Y12 inhibitors over clopidogrel for preventing ischemic complications is notable in the early phase after myocardial infarction (MI), when the ischemic risk is the highest, whereas most bleeding events occur during the maintenance phase.6,7,8 Therefore, balancing the risk of ischemic and bleeding events is a cornerstone of antiplatelet management in patients with AMI. Several DAPT strategies have been investigated in randomized clinical trials to achieve this balance.9,10,11,12,13,14

Recently, the Ticagrelor vs Clopidogrel in Stabilized Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction (TALOS-AMI) randomized clinical trial demonstrated that an unguided de-escalation DAPT strategy of switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in stabilized patients with AMI 1 month after an index PCI was noninferior and even superior to the ticagrelor-based DAPT strategy in terms of net clinical outcome, without differences in ischemic risk but with a significant reduction in bleeding risk.9 While recent evidence supports the use of early de-escalation from potent P2Y12 inhibitors to clopidogrel as a feasible option without increasing ischemic risk,9,14,15 the question remains as to whether such a strategy is a safe option for patients with AMI and high ischemic risk. Therefore, a post hoc analysis of the TALOS-AMI trial was designed to investigate the ischemic and bleeding outcomes of a 1-month unguided de-escalation DAPT strategy of switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel compared with those of a ticagrelor-based DAPT strategy in stabilized patients with AMI and high ischemic risk.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a post hoc analysis of the TALOS-AMI trial,9,16 an open-label, assessor-blinded, multicenter, randomized clinical trial, to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the de-escalation DAPT strategy of switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel 1 month after an index PCI. The details of the TALOS-AMI trial have been described previously.9,17 In brief, stabilized patients with AMI and no major adverse ischemic or bleeding events who tolerated DAPT (aspirin and ticagrelor) for 1 month after an index PCI were randomly assigned to either (1) a de-escalation strategy with 11 months of DAPT with clopidogrel or (2) a standard DAPT strategy of continuing ticagrelor for another 11 months. All patients in the trial underwent successful PCI using current-generation drug-eluting stents and received guideline-directed medical therapy. Patients were evaluated at 3, 6, and 12 months after AMI and were monitored for the occurrence of clinical events. Clinical follow-up was performed by office visits or telephone contact regularly and as needed. The patients who experienced clinical events were followed up for 12 months unless they were deceased or quit early. The trial protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each participating institute and conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent. An independent data and safety monitoring board provided external oversight to ensure the safety of the study participants. The trial protocol can be found in Supplement 1, and the statistical analysis plan is shown in Supplement 2. Data were collected from February 14, 2014, to January 21, 2021, and analyzed from December 1, 2021, to June 30, 2022.

Study Population

All participants in the TALOS-AMI trial were classified into 2 groups, high ischemic risk vs non–high ischemic risk. High ischemic risk was defined as fulfilling at least 1 of the following clinical or procedural features: (1) a history of diabetes treated with medication, (2) a history of chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, which was calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation), (3) multivessel PCI, (4) at least 3 lesions treated, (5) a total stent length greater than 60 mm, (6) at least 3 stents implanted, (7) left main PCI, or (8) bifurcation PCI treated with 2 stents. These high-risk features for ischemic events were modified from the previous guidelines.2,3 Multivessel PCI was defined as PCI to treat 2 or more major epicardial coronary arteries. Complex PCI was defined as satisfying at least 1 of the 6 procedural features. The high ischemic risk and non–high ischemic risk groups each included patients assigned to the de-escalation strategy and patients assigned to the ticagrelor-based DAPT strategy.

Outcomes

The primary ischemic outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, ischemic stroke, ischemia-driven revascularization, or stent thrombosis from 1 to 12 months after an index PCI. The key secondary outcomes were Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding18 from 1 to 12 months after an index PCI. Other secondary outcomes included net adverse clinical events, all-cause death, and individual components of the ischemic and bleeding outcomes between randomization and 1-year follow-up. Detailed definitions of outcomes are provided in eTable 1 in Supplement 3.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were reported as counts (percentages) and compared using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables were expressed as mean (SD) and compared by t test. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs were calculated using the Cox regression model. The treatment outcomes of the de-escalation strategy vs the ticagrelor-based DAPT strategy between patients with and without high ischemic risk were also evaluated with interaction testing. In addition, we assessed the HR of ischemic and bleeding outcomes in the categories derived from the individual components of the high ischemic risk criteria. Cumulative incidences of primary and secondary outcomes were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Absolute risk differences for clinical events between groups with and without high ischemic risk were calculated with Kaplan-Meier estimates and Greenwood SEs. Analyses were performed in the intention-to-treat population for all the clinical outcomes. Additional analysis was done in the per-protocol principle. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). All statistical testing was 2-sided. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Of 2697 patients with AMI enrolled in the TALOS-AMI trial (mean [SD] age, 60.0 [11.4] years; 454 [16.8%] female), 1371 patients (50.8%; 684 assigned to de-escalation and 687 assigned to the active control of ticagrelor-based DAPT) were classified as having high ischemic risk features (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3), whereas 1326 patients (49.2%; 665 assigned to de-escalation and 661 assigned to the active control) did not have high ischemic risk. A total of 1282 patients (93.5%) with high ischemic risk and 1228 (92.6%) without high ischemic risk completed follow-up at 12 months. Baseline characteristics for patients stratified by high ischemic risk and antiplatelet strategy are presented in Table 1 and in eTable 2 in Supplement 3. The patients with high ischemic risk were more likely to be older and female and had more comorbidities. Non–ST-segment elevation MI and left ventricular systolic dysfunction were more frequent in the high ischemic risk group.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) According to Ischemic Risk and Antiplatelet Strategy.

| Characteristic | AMI with high ischemic risk (n = 1371) | AMI without high ischemic risk (n = 1326) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | P value | No. (%) | P value | |||

| De-escalation (n = 684) | Active control (n = 687) | De-escalation (n = 665) | Active control (n = 661) | |||

| Age | ||||||

| Mean (SD), y | 61.6 (11.2) | 61.7 (11.4) | .86 | 58.4 (11.1) | 58.0 (11.1) | .44 |

| ≥75 y | 97 (14.2) | 103 (15.0) | .67 | 60 (9.0) | 61 (9.2) | .90 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 120 (17.5) | 139 (20.2) | .20 | 97 (14.6) | 98 (14.8) | .90 |

| Male | 564 (82.5) | 548 (79.8) | 568 (85.4) | 563 (85.2) | ||

| BMI, mean (SD) | 24.7 (3.1) | 24.6 (3.2) | .58 | 24.6 (3.1) | 24.5 (3.1) | .51 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||||

| Diabetes | 362 (52.9) | 369 (53.7) | .77 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Hypertension | 392 (57.3) | 404 (58.8) | .56 | 263 (39.6) | 259 (39.2) | .91 |

| Dyslipidemia | 314 (45.9) | 291 (42.4) | .19 | 249 (37.4) | 265 (40.2) | .31 |

| Current smoker | 322 (47.1) | 305 (44.4) | .32 | 348 (52.3) | 369 (55.9) | .19 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 160 (23.8) | 145 (21.4) | .29 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Previous PCI | 39 (5.7) | 37 (5.4) | .80 | 22 (3.3) | 23 (3.5) | .86 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass graft | 2 (0.3) | 0 | .16 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | >.99 |

| Previous cerebrovascular accident | 33 (4.8) | 34 (5.0) | .92 | 20 (3.0) | 16 (2.4) | .52 |

| Clinical presentation | ||||||

| STEMI | 341 (49.9) | 343 (49.9) | .98 | 393 (59.1) | 378 (57.2) | .48 |

| Non-STEMI | 343 (50.2) | 344 (50.1) | 272 (40.9) | 283 (42.8) | ||

| LVEF <40% | 68 (10.1) | 56 (8.5) | .32 | 35 (5.4) | 37 (5.8) | .78 |

| PRECISE-DAPT score, mean (SD) | 18.8 (10.7) | 18.8 (10.7) | .99 | 14.5 (8.3) | 14.5 (8.2) | .94 |

| Procedural | ||||||

| Radial access | 336 (49.1) | 343 (49.9) | .94 | 330 (49.6) | 343 (51.9) | .62 |

| Femoral access | 348 (50.9) | 344 (50.1) | 335 (50.4) | 318 (48.1) | ||

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 167 (24.4) | 171 (24.9) | .84 | 155 (23.3) | 151 (22.9) | .87 |

| Infarct-related artery | ||||||

| Left main coronary artery | 21 (3.1) | 24 (3.5) | .05 | 0 | 0 | .12 |

| Left anterior descending artery | 307 (45.0) | 270 (39.3) | 378 (56.8) | 364 (55.2) | ||

| Left circumflex artery | 105 (15.4) | 141 (20.5) | 97 (14.6) | 123 (18.7) | ||

| Right coronary artery | 250 (36.6) | 252 (36.7) | 190 (28.6) | 172 (26.1) | ||

| Multivessel PCI | 336 (49.1) | 342 (49.8) | .88 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Total No. of stents, mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.5) | .99 | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | .15 |

| Total stent length, mean (SD), mm | 32.1 (15.2) | 32.7 (16.3) | .49 | 27.5 (10.2) | 26.3 (9.5) | .04 |

| Stent diameter, mean (SD), mm | 3.2 (0.4) | 3.2 (0.5) | .99 | 3.2 (0.5) | 3.2 (0.5) | .50 |

| Bifurcation PCI with 2 stents | 8 (1.2) | 7 (1.0) | .79 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Intravascular ultrasonography | 179 (26.3) | 173 (25.3) | .66 | 154 (23.4) | 134 (20.7) | .25 |

| Optical coherence tomography | 17 (2.5) | 19 (2.8) | .75 | 30 (4.6) | 16 (2.5) | .04 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NA, not applicable; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PRECISE-DAPT, Predicting Bleeding Complications in Patients Undergoing Stent Implantation and Subsequent Dual Antiplatelet Therapy; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

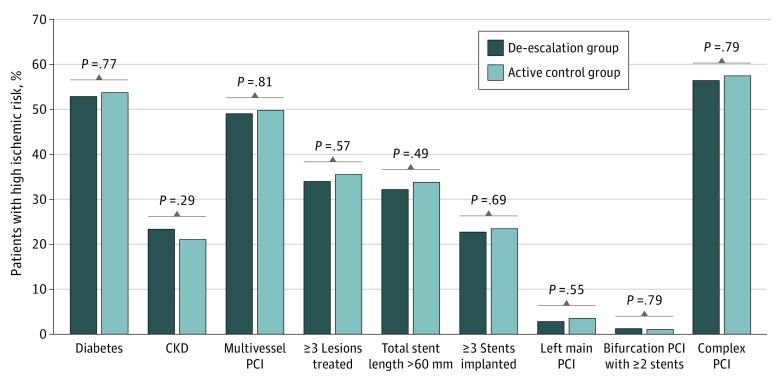

In the high ischemic risk group, baseline characteristics between the 2 antiplatelet strategies were well balanced without a significant difference, except for the prevalence of culprit vessels. The prevalences of individual components of the high risk of ischemia are presented in Figure 1. Among the 1371 patients in the high ischemic risk group, diabetes was present in 731 (53.3%) and chronic kidney disease was present in 305 (22.2%). Complex PCI was performed in 788 patients (57.5%). There was no difference in the prevalence of each ischemic risk feature between the 2 antiplatelet strategies.

Figure 1. Prevalence of the Individual High Ischemic Risk Features.

The prevalence of each high ischemic risk factor is shown according to the clinical and procedural aspects for patients with high ischemic risk in the de-escalation group (de-escalation strategy of switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel) vs the active control group (dual antiplatelet therapy with ticagrelor). CKD indicates chronic kidney disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Outcomes by High Ischemic Risk

Clinical outcomes in patients with AMI with or without high ischemic risk are shown in eTable 3, eTable 4, and eFigure 2 in Supplement 3. The risk of primary ischemic outcome was significantly higher in patients with a high risk of ischemia than in patients without (63 of 1371 patients [5.0%] vs 35 of 1326 patients [2.8%], respectively; HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.15-2.63; P = .01), which was mainly driven by an increased risk of any MI and any revascularization. However, there was no significant difference in the rate of BARC type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding between the high ischemic risk and non–high ischemic risk groups (53 of 1371 patients [4.1%] vs 56 of 1326 patients [4.5%], respectively; HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.63-1.33; P = .64). The risks of net adverse clinical events and other secondary end points were also comparable between the 2 groups.

Outcomes by High Ischemic Risk and Antiplatelet Strategy

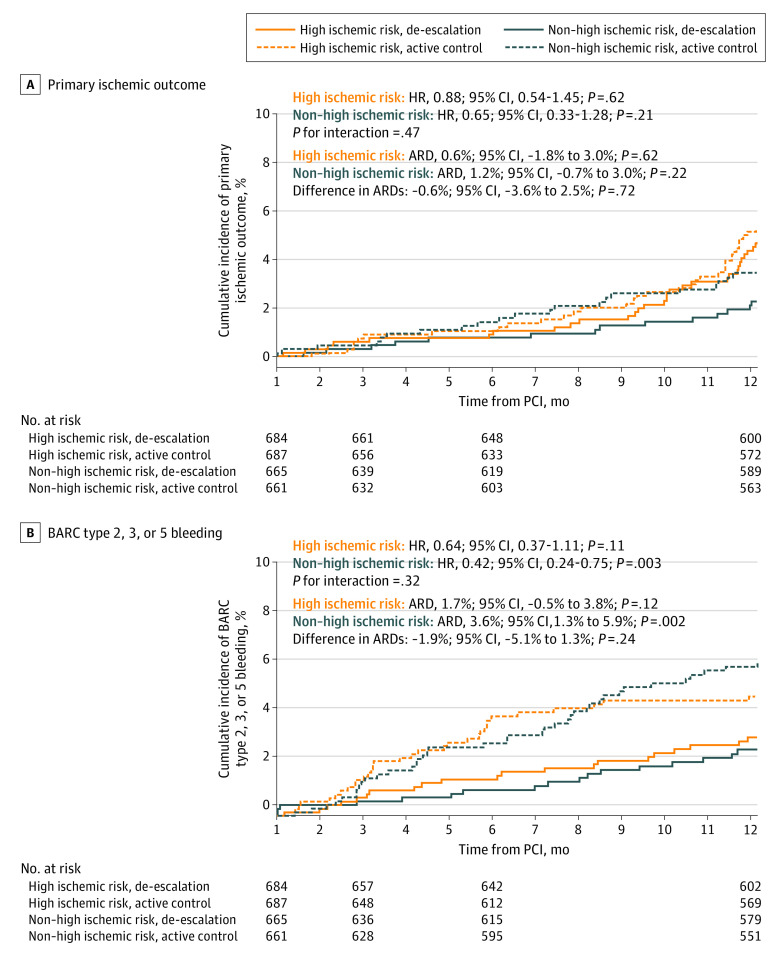

Ischemic outcomes according to the antiplatelet strategies are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2A (per-protocol analysis is shown in eTable 5 and eFigure 3A in Supplement 3). There was no significant difference in the risk of the primary ischemic outcome between the de-escalation and ticagrelor-based DAPT strategies in the high ischemic risk group (30 of 684 patients [4.7%] vs 33 of 687 patients [5.3%], respectively; HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.54-1.45; P = .62) and the non–high ischemic risk group (14 of 665 patients [2.3%] vs 21 of 661 patients [3.4%], respectively; HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.33-1.28; P = .21), without a significant interaction (P for interaction = .47). The difference in absolute risk differences was not significant (−0.6%; 95% CI, −3.6% to 2.5%; P = .72). The individual ischemic outcomes, such as cardiovascular death, MI, ischemic stroke, ischemia-driven revascularization, and stent thrombosis, and the risk of all-cause death were comparable between the 2 antiplatelet strategies in patients with high ischemic risk.

Table 2. Outcomes by High Ischemic Risk and Antiplatelet Strategy.

| Outcome | AMI with high ischemic risk (n = 1371) | AMI without high ischemic risk (n = 1326) | P value for interaction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%)a | HR (95% CI) | P value | No. (%)a | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| De-escalation (n = 684) | Active control (n = 687) | De-escalation (n = 665) | Active control (n = 661) | ||||||

| Primary ischemic outcome | 30 (4.7) | 33 (5.3) | 0.88 (0.54-1.45) | .62 | 14 (2.3) | 21 (3.4) | 0.65 (0.33-1.28) | .21 | .47 |

| BARC bleeding | |||||||||

| Type 2, 3, or 5 | 21 (3.2) | 32 (4.9) | 0.64 (0.37-1.11) | .11 | 17 (2.7) | 39 (6.3) | 0.42 (0.24-0.75) | .003 | .32 |

| Type 2 | 13 (2.0) | 23 (3.5) | 0.55 (0.28-1.09) | .09 | 14 (2.2) | 27 (4.4) | 0.51 (0.27-0.97) | .04 | .87 |

| Type 3 or 5 | 11 (1.7) | 12 (1.9) | 0.90 (0.40-2.04) | .80 | 4 (0.7) | 16 (2.7) | 0.24 (0.08-0.73) | .01 | .06 |

| Net adverse clinical events | 48 (7.4) | 64 (10.0) | 0.72 (0.50-1.05) | .09 | 29 (4.7) | 57 (9.2) | 0.49 (0.31-0.77) | .002 | .19 |

| Composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke | 17 (2.6) | 23 (3.7) | 0.72 (0.38-1.35) | .30 | 10 (1.6) | 15 (2.4) | 0.65 (0.29-1.45) | .29 | .84 |

| All-cause death | 6 (0.9) | 9 (1.4) | 0.65 (0.23-1.82) | .41 | 5 (0.8) | 1 (0.2) | 4.93 (0.58-41.67) | .15 | .10 |

| Cardiovascular death | 3 (0.5) | 5 (0.8) | 0.58 (0.14-2.44) | .46 | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 2.95 (0.31-28.57) | .35 | .24 |

| MI | 10 (1.6) | 13 (2.1) | 0.74 (0.33-1.69) | .48 | 2 (0.3) | 7 (1.1) | 0.28 (0.06-1.35) | .11 | .28 |

| Ischemic stroke | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.8) | 0.20 (0.02-1.69) | .14 | 5 (0.8) | 5 (0.8) | 0.98 (0.28-3.38) | .97 | .20 |

| Ischemia-driven revascularization | 26 (4.1) | 24 (3.9) | 1.05 (0.60-1.82) | .87 | 6 (1.0) | 15 (2.5) | 0.39 (0.15-1.00) | .05 | .08 |

| Stent thrombosis | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.3) | 1.44 (0.24-8.62) | .69 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | NA | NA | .99 |

Abbreviations: AMI, acute myocardial infarction; BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; HR, hazard ratio; MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not applicable.

The percentages represent Kaplan-Meier estimates.

Figure 2. Clinical Outcomes of the Antiplatelet Strategy.

A, In patients with high ischemic risk, there was no significant difference in the primary ischemic outcome between the de-escalation group (de-escalation strategy of switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel) vs the active control group (dual antiplatelet therapy with ticagrelor). The difference in absolute risk differences (ARDs) between patients with high ischemic risk and those without high ischemic risk was not significant. B, In patients with high ischemic risk, the risk of Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding was numerically but not signficantly lower with de-escalation. The difference in ARDs between patients with high ischemic risk and those without high ischemic risk was not significant. HR indicates hazard ratio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Bleeding outcomes according to the antiplatelet strategies are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2B (per-protocol analysis is shown in eTable 5 and eFigure 3B in Supplement 3). With de-escalation treatment compared with standard DAPT, bleeding risk was consistent in both the high ischemic risk group (21 of 684 patients [3.2%] vs 32 of 687 patients [4.9%], respectively; HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.37-1.11; P = .11) and the non–high ischemic risk group (17 of 665 patients [2.7%] vs 39 of 661 patients [6.3%], respectively; HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.24-0.75; P = .003), without significant interaction (P for interaction = .32). The difference in absolute risk differences was not significant (−1.9%; 95% CI, −5.1% to 1.3%; P = .24). In the per-protocol analysis, BARC type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding events were significantly lower in the de-escalation group than in the standard DAPT group in both the high ischemic risk group (17 of 616 patients [2.8%] vs 30 of 603 patients [5.0%], respectively; HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.30-0.99; P = .046) and the non–high ischemic risk group (16 of 592 patients [2.7%] vs 34 of 569 patients [6.0%], respectively; HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.25-0.81; P = .01) (P for interaction = .64).

Subgroup analyses revealed that compared with the standard DAPT strategy, the de-escalation strategy was associated with comparable results for the ischemic and bleeding outcomes across all subgroups, without significant interactions (eFigure 4 in Supplement 3).

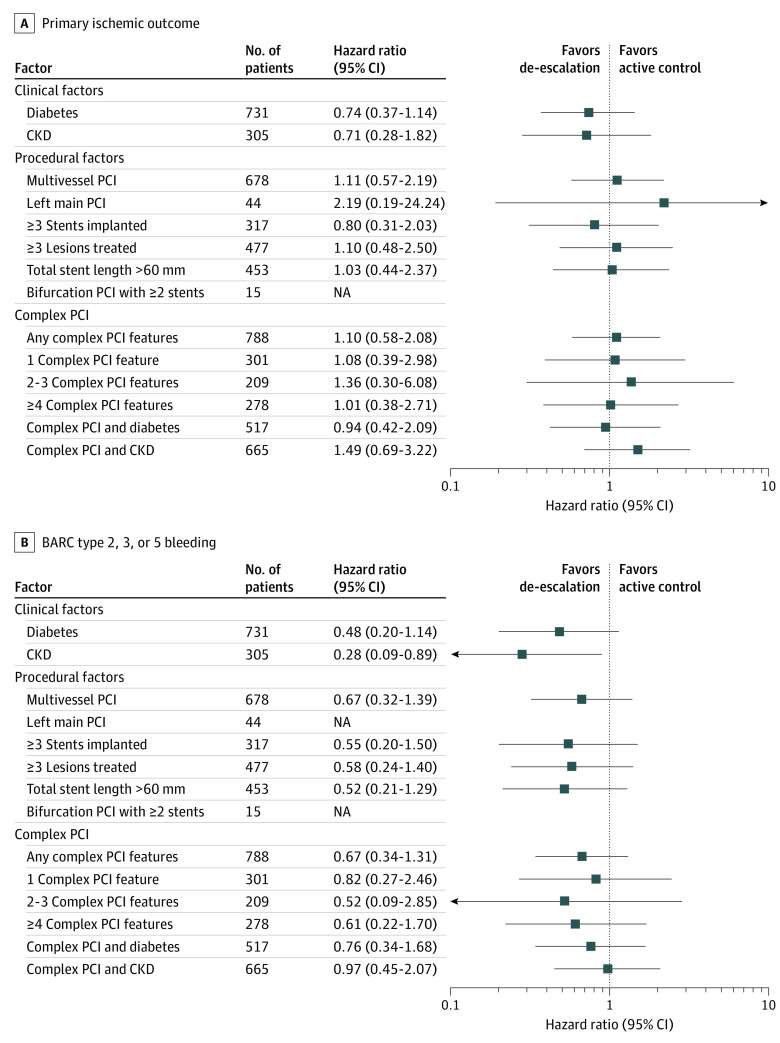

Outcomes by Individual Components of High Ischemic Risk

The impact of de-escalation treatment compared with the ticagrelor-based DAPT strategy according to the individual high ischemic risk features and the number of complex PCI features is shown in Figure 3. The primary ischemic outcomes following de-escalation treatment were consistent across all components of high ischemic risk. Notably, de-escalation therapy was not associated with an increased risk of ischemic events compared with ticagrelor-based DAPT irrespective of the number of complex PCI features or clinical scenarios. The bleeding risk was not significantly different between de-escalation treatment and standard DAPT in patients with high ischemic risk except in those with chronic kidney disease, in whom the de-escalation strategy was associated with a significantly lower bleeding risk compared with the standard DAPT strategy (HR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.09-0.89; P = .03).

Figure 3. Associations of the Antiplatelet Strategy According to the Individual Components of High Ischemic Risk.

A, Across the individual high ischemic risk factors and the number of complex percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) features, there was no significant difference in the risk of primary ischemic outcome between the de-escalation strategy (switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel) and the active control strategy (dual antiplatelet therapy with ticagrelor). B, The risk of Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding was numerically but not significantly lower in the de-escalation strategy compared with the active control group except in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). NA indicates not applicable.

Discussion

Among patients enrolled in the TALOS-AMI trial, more than half had high ischemic risk features. In addition, the risk of the primary ischemic outcome was significantly higher in patients with high ischemic risk, whereas bleeding events were not different compared with patients without high ischemic risk. In stabilized patients with AMI, the ischemic and bleeding outcomes of de-escalation therapy with clopidogrel compared with ticagrelor-based DAPT were consistent regardless of high ischemic risk features, without significant interaction. In patients with a high risk of ischemia, the ischemic outcomes of de-escalation therapy were similar across the individual high ischemic risk criteria. There were no signals of increased ischemic risk with de-escalation therapy according to the increased number of high ischemic risk features.

Previous landmark clinical trials demonstrated that the preventive effect of DAPT on recurrent ischemic events was consistent throughout the first year following the index acute coronary syndrome (ACS) event, but a more significant ischemic benefit was observed during the early phase.6,7,8 In contrast, there was a considerable increase in bleeding events with potent P2Y12 inhibitors, occurring predominantly during the maintenance phase. Thus, the focus of antiplatelet therapy has shifted toward preventing bleeding complications without increasing the ischemic risk. Several DAPT strategies have been proposed to maintain efficacious antithrombotic activity while keeping long-term bleeding risk low.9,10,11,12,13,14 As a result, recent guidelines state that unguided or guided de-escalation of P2Y12 inhibitor treatment may be considered an alternative DAPT strategy, especially for patients with ACS in whom potent platelet inhibition is unsuitable,2 but the decision should be made depending on each patient’s clinical profile. Although evidence generally indicates that de-escalation might be beneficial, the question remains as to whether such a strategy is a safe option for patients with a high risk of ischemia.

Given that ischemic and bleeding risks frequently coincide, selecting the best antiplatelet regimen to obtain the maximal net clinical benefit is of paramount importance and remains a major clinical challenge even for patients with high ischemic risk. Several recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety outcomes of various DAPT strategies in high-risk patients. An extended duration of DAPT has been shown to be more beneficial in preventing recurrent stent-related ischemic events in patients who have undergone complex PCI.19 However, compared with the standard DAPT strategy, short DAPT followed by clopidogrel,20 P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy,21 and ticagrelor monotherapy22,23 could provide similar clinical benefits after complex PCI. In addition, ticagrelor monotherapy24 and prasugrel dose de-escalation25 are not associated with an increased risk of ischemic outcomes in patients with ACS who have high risk of ischemic events or complex PCI, respectively (eTable 6 in Supplement 3). The present study is the first, to our knowledge, to investigate the efficacy and safety of an unguided de-escalation from ticagrelor to clopidogrel 1 month following PCI in patients with AMI who have high ischemic risk. Our findings support that unguided de-escalation from ticagrelor to clopidogrel can be a safe and feasible antiplatelet strategy in patients with high atherothrombotic risk. However, the upper bound of the 95% CI for the primary ischemic outcome in patients with high ischemic risk was 1.45. This value exceeds the reference ratio of 1.25, which represents the primary efficacy end point between 1 and 12 months in the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial.4,9 Due to this disparity, the wide 95% CI for the primary ischemic outcome might not provide sufficient statistical power to conclusively dismiss the possibility of an increased occurrence of ischemic events.

In patients with ACS, recurrent ischemic events 1 month after an index PCI are not uncommon despite the advancement of stent-related device technology and operators’ PCI skills. Maintaining DAPT is essential for preventing recurrent cardiovascular events arising from previously stented culprit arteries as well as nonculprit arteries, especially in patients with AMI.26,27 In previous randomized clinical trials among patients with ACS, aspirin monotherapy28,29 and clopidogrel monotherapy30 after an abbreviated duration of DAPT were shown to be associated with an approximately 2-fold increased risk of MI, suggesting that single antiplatelet therapy with aspirin or clopidogrel would be insufficient in patients with a high risk of recurrent ischemic events. The high prevalence of CYP2C19 poor metabolizers in East Asian individuals may also contribute to an increased risk of recurrent ischemia.31 The combination of clopidogrel and aspirin, which blocks the P2Y12 receptor and thromboxane-mediated pathway simultaneously, has an additive effect. Our DAPT strategy maintains a conventional option for 12 months, and it can be one of the plausible explanations for not increasing the risk of recurrent ischemic events in patients with a high risk of ischemia. Furthermore, de-escalation to clopidogrel could be a feasible option in patients with high bleeding risk, such as patients who have contraindications for prasugrel (eg, old age [>75 years], low body weight), and intolerance to ticagrelor due to adverse effects. Although ticagrelor monotherapy11 after short-term DAPT and prasugrel-based de-escalation10 reduce the risk of net clinical outcomes in patients with ACS, a direct comparison of various DAPT strategies would be difficult owing to substantial differences in the population, methods, end points, and definitions of ischemic and bleeding risk in each study.

In our study, the de-escalation group received a uniform unguided de-escalation from ticagrelor to clopidogrel without the guidance of platelet function tests or genotyping. Despite a higher prevalence of CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles in East Asian individuals,31 which are known to increase platelet reactivity, our study showed comparable outcomes of unguided de-escalation therapy compared with DAPT with a potent P2Y12 inhibitor in terms of ischemic and bleeding outcomes, especially in patients with AMI who have a high risk of ischemic events. This can be explained by the unique design of the TALOS-AMI trial in that the randomization was done beyond the early phase of AMI in stabilized patients who tolerated ticagrelor and did not have ischemic or bleeding events for 1 month after an index PCI, whereas previous trials of platelet function test–guided or genotyping-guided de-escalation strategies were performed within the acute period.32,33 A 2022 meta-analysis34 showed that de-escalation of DAPT after PCI for ACS, either unguided or guided, was associated with reduced clinically relevant bleeding and major adverse cardiovascular events compared with standard DAPT with potent P2Y12 inhibitors.

Atherothrombotic clinical risk factors and complex angiographic features are related to a higher risk of ischemic events in patients undergoing PCI. In our study, procedural risks seemed to have greater ischemic risk than clinical risks inferred from the results of the ischemic outcomes (eFigure 4 in Supplement 3). Généreux et al35 reported that in patients who underwent complex PCI, the ischemic risk was higher within 6 months but not after 6 months. Korean PCI registry data showed clinical risks had a more profound and persistent association with adverse ischemic outcomes, while procedural risks had no association after 2 years.36 Since our study focuses on patients with AMI with 1-year follow-up, procedural risks might influence the greater ischemic risk over clinical risks.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, this post hoc analysis was not prespecified; thus, randomization was not stratified by high ischemic risk. This resulted in demographic and procedural differences between the 2 groups, which can potentially impact the observed associations or outcomes. Additionally, conducting multiple analyses without adjusting for multiple testing might increase type I errors. Owing to the reduced sample size, the power was limited to draw definite conclusions on the ischemic and bleeding outcomes of de-escalation therapy. Therefore, the results of our study should be interpreted with caution (our results are applicable only for patients who successfully completed 1 month of DAPT with aspirin and ticagrelor following AMI without experiencing any adverse events) and need to be validated by further large-scale studies. In addition, the definition of high ischemic risk used in the study might differ between trials. However, we adopted each high-risk feature based on current guidelines.2,3 This trial could not validate the long-term outcomes of the unguided de-escalation DAPT strategy in patients with AMI and high ischemic risk. The long-term follow-up results of the TALOS-AMI trial will potentially address this issue.

Conclusions

Among stabilized patients with AMI without evidence of adverse events in the first month following an index PCI, the ischemic and bleeding outcomes of an unguided de-escalation DAPT strategy of switching from ticagrelor to clopidogrel compared with a ticagrelor-based DAPT strategy were consistent regardless of the presence of high ischemic risk features, with no heterogeneity. However, due to the wide 95% CIs for the primary ischemic outcome, it might not have sufficient power to exclude the possibility of more adverse events in the de-escalation strategy.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Definitions of Outcomes

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of AMI Patients With or Without High Ischemic Risk

eTable 3. Outcomes by High Ischemic Risk

eTable 4. Ischemic Outcomes Stratified by High Ischemic Risk Features

eTable 5. Outcomes by High Ischemic Risk and Antiplatelet Strategy (Per-Protocol)

eTable 6. Major Post-Hoc Study of Randomized Controlled Trials Investigating De-Escalation Antiplatelet Strategy in ACS/AMI Patients Who Underwent Complex PCI or Had High Ischemic Risk

eFigure 1. Patient Flow Diagram of the Present Study

eFigure 2. Impact of High Ischemic Risk in Stabilized Post-Myocardial Infarction Patients

eFigure 3. Clinical Outcomes of the Antiplatelet Strategy (Per-Protocol)

eFigure 4. Subgroup Analysis in Patients With High Ischemic Risk

eReferences.

Group Information. TALOS-AMI Investigators

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. ; Writing Committee Members . 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21-e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(14):1289-1367. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(2):87-165. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. ; PLATO Investigators . Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1045-1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. ; TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators . Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2001-2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez F, Harrington RA. Management of antithrombotic therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):452-460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1607714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker RC, Bassand JP, Budaj A, et al. Bleeding complications with the P2Y12 receptor antagonists clopidogrel and ticagrelor in the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(23):2933-2944. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/I422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antman EM, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, et al. Early and late benefits of prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a TRITON-TIMI 38 (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition With Prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(21):2028-2033. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim CJ, Park MW, Kim MC, et al. ; TALOS-AMI Investigators . Unguided de-escalation from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in stabilised patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (TALOS-AMI): an investigator-initiated, open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10308):1305-1316. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01445-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HS, Kang J, Hwang D, et al. ; HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS Investigators . Prasugrel-based de-escalation of dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome (HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS): an open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority randomised trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10257):1079-1089. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31791-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim BK, Hong SJ, Cho YH, et al. ; TICO Investigators . Effect of ticagrelor monotherapy vs ticagrelor with aspirin on major bleeding and cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome: the TICO randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(23):2407-2416. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehran R, Baber U, Sharma SK, et al. Ticagrelor with or without aspirin in high-risk patients after PCI. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2032-2042. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vranckx P, Valgimigli M, Jüni P, et al. ; GLOBAL LEADERS Investigators . Ticagrelor plus aspirin for 1 month, followed by ticagrelor monotherapy for 23 months vs aspirin plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor for 12 months, followed by aspirin monotherapy for 12 months after implantation of a drug-eluting stent: a multicentre, open-label, randomised superiority trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10151):940-949. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31858-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuisset T, Deharo P, Quilici J, et al. Benefit of switching dual antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome: the TOPIC (Timing of Platelet Inhibition After Acute Coronary Syndrome) randomized study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(41):3070-3078. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoji S, Kuno T, Fujisaki T, et al. De-escalation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(8):763-777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in stabilized patients with acute myocardial infarction: TALOS-AMI. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02018055. Updated April 2, 2021. Accessed October 31, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02018055

- 17.Park MW, Kim CJ, Kim MC, et al. A prospective, multicentre, randomised, open-label trial to compare the efficacy and safety of clopidogrel versus ticagrelor in stabilised patients with acute myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention: rationale and design of the TALOS-AMI trial. EuroIntervention. 2021;16(14):1170-1176. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-20-00187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123(23):2736-2747. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giustino G, Chieffo A, Palmerini T, et al. Efficacy and safety of dual antiplatelet therapy after complex PCI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(17):1851-1864. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.07.760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto K, Watanabe H, Morimoto T, et al. ; STOPDAPT-2 Investigators . Very short dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation in patients who underwent complex percutaneous coronary intervention: insight from the STOPDAPT-2 trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(5):e010384. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.120.010384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roh JW, Hahn JY, Oh JH, et al. P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy in complex percutaneous coronary intervention: a post-hoc analysis of SMART-CHOICE randomized clinical trial. Cardiol J. 2021;28(6):855-863. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2021.0101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dangas G, Baber U, Sharma S, et al. Ticagrelor with or without aspirin after complex PCI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(19):2414-2424. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serruys PW, Takahashi K, Chichareon P, et al. Impact of long-term ticagrelor monotherapy following 1-month dual antiplatelet therapy in patients who underwent complex percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the Global Leaders trial. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(31):2595-2604. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SJ, Lee YJ, Kim BK, et al. Ticagrelor monotherapy versus ticagrelor with aspirin in acute coronary syndrome patients with a high risk of ischemic events. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(8):e010812. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.010812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang D, Lim YH, Park KW, et al. ; HOST-RP-ACS Investigators . Prasugrel dose de-escalation therapy after complex percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a post hoc analysis from the HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(4):418-426. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonaca MP, Bhatt DL, Cohen M, et al. ; PEGASUS-TIMI 54 Steering Committee and Investigators . Long-term use of ticagrelor in patients with prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1791-1800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexopoulos D, Xanthopoulou I, Moulias A, Lekakis J. Long-term P2Y12-receptor antagonists in post-myocardial infarction patients: facing a new trilemma? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(11):1223-1232. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hahn JY, Song YB, Oh JH, et al. ; SMART-DATE Investigators . 6-Month versus 12-month or longer dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome (SMART-DATE): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1274-1284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30493-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong SJ, Kim JS, Hong SJ, et al. ; One-Month DAPT Investigators . 1-Month dual-antiplatelet therapy followed by aspirin monotherapy after polymer-free drug-coated stent implantation: One-Month DAPT trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(16):1801-1811. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe H, Morimoto T, Natsuaki M, et al. ; STOPDAPT-2 ACS Investigators . Comparison of clopidogrel monotherapy after 1 to 2 months of dual antiplatelet therapy with 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome: the STOPDAPT-2 ACS randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(4):407-417. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.5244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim HS, Chang K, Koh YS, et al. CYP2C19 poor metabolizer is associated with clinical outcome of clopidogrel therapy in acute myocardial infarction but not stable angina. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6(5):514-521. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Claassens DMF, Vos GJA, Bergmeijer TO, et al. A genotype-guided strategy for oral P2Y12 inhibitors in primary PCI. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(17):1621-1631. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1907096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sibbing D, Aradi D, Jacobshagen C, et al. ; TROPICAL-ACS Investigators . Guided de-escalation of antiplatelet treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (TROPICAL-ACS): a randomised, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10104):1747-1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32155-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tavenier AH, Mehran R, Chiarito M, et al. Guided and unguided de-escalation from potent P2Y12 inhibitors among patients with acute coronary syndrome: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2022;8(5):492-502. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvab068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Généreux P, Giustino G, Redfors B, et al. Impact of percutaneous coronary intervention extent, complexity and platelet reactivity on outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2018;268:61-67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.03.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang J, Park KW, Lee HS, et al. Relative impact of clinical risk versus procedural risk on clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(2):e009642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.120.009642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Definitions of Outcomes

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of AMI Patients With or Without High Ischemic Risk

eTable 3. Outcomes by High Ischemic Risk

eTable 4. Ischemic Outcomes Stratified by High Ischemic Risk Features

eTable 5. Outcomes by High Ischemic Risk and Antiplatelet Strategy (Per-Protocol)

eTable 6. Major Post-Hoc Study of Randomized Controlled Trials Investigating De-Escalation Antiplatelet Strategy in ACS/AMI Patients Who Underwent Complex PCI or Had High Ischemic Risk

eFigure 1. Patient Flow Diagram of the Present Study

eFigure 2. Impact of High Ischemic Risk in Stabilized Post-Myocardial Infarction Patients

eFigure 3. Clinical Outcomes of the Antiplatelet Strategy (Per-Protocol)

eFigure 4. Subgroup Analysis in Patients With High Ischemic Risk

eReferences.

Group Information. TALOS-AMI Investigators

Data Sharing Statement