Abstract

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases. Several studies have investigated the relationship between obesity and AD prevalence, but the results have been conflicting. This study investigated the association between obesity and AD in Korean adolescents.

Methods

We used nationally representative data regarding 1,617 Korean adolescents aged 12–18 years, which were obtained from the cross-sectional Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–2019. Multiple logistic regression analysis (including age, sex, region of residence, number of household members, economic status, lipid profile, and stress level) was used to evaluate the relationships of obesity and abdominal obesity with doctor-diagnosed AD.

Results

Although the results were not statistically significant, obese adolescents were diagnosed with AD (20.8%) more often than non-obese adolescents (20.8% vs. 14.5%, p = 0.055). This tendency was more prominent in male adolescents than in female adolescents, but the finding was not statistically significant. Body mass index and the prevalence of abdominal obesity did not differ between the AD and non-AD groups. Adolescents with AD had significantly higher total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels, compared with adolescents who did not have AD. In the adjusted model, an LDL-C level ≥130 mg/dL was a risk factor for AD (adjusted odds ratio, 1.03; 95% confidence interval, 1.01–1.05).

Conclusions

A high LDL-C level may be a risk factor for AD. Proper management of dyslipidemia through lifestyle modification may aid in AD prevention and control. Further large-scale prospective studies are needed to assess the associations of AD with obesity and dyslipidemia.

Keywords: Dermatitis, Atopic diseases, Obesity, Cholesterol, Low-density lipoprotein, Adolescent, Korea

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease with a high prevalence worldwide. In some countries, >20% of children have AD [1, 2], which negatively influences the quality of life for affected patients and their families [3]. Generally, most infants with AD show improvement before children reach school age. However, a prospective cohort study demonstrated that AD persisted until adulthood in approximately 50% of individuals who had been diagnosed at school age; moreover, 30% of the patients developed AD after 14 years of age [4].

Obesity is a known risk factor for asthma. Several studies have reported that obesity is associated with both AD prevalence and severity [5–10]. This has important clinical ramifications because obesity may constitute a modifiable risk factor [7, 8]. Obesity in infancy or early childhood (age <2 years) is reportedly associated with AD [5]. A recent meta-analysis showed that overweight/obesity was associated with an increased risk of AD [11]. In a population-based study, AD was associated with slightly higher odds of overweight or obesity, but there were no associations of overweight or obesity with AD severity [6].

The prevalence of obesity has increased over time. When the World Health Organization declared that the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 constituted a pandemic, many countries implemented social distancing to reduce disease transmission. School closure was one of the interventions implemented in Korea. Children and adolescents stayed home, which reduced opportunities for physical activity and resulted in weight gain [12].

With the increasing prevalence of obesity related to coronavirus disease 2019-related closures, there is a growing need to clarify the relationship between obesity and AD. This study investigated the association between obesity and AD in Korean adolescents using data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES).

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Participants

This study used data from the KNHANES 2017–2019, which is a nationwide surveillance system that has been assessing the health and nutritional status of Koreans since 1998. This nationally representative cross-sectional survey is conducted annually by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [13]. The survey consists of three components: a health interview, a physical examination, and a nutritional evaluation. The survey results are weighted to represent the non-institutionalized population nationally and in each province.

Among 1,617 adolescents aged 12–18 years (2017, n = 565; 2018, n = 517; 2019, n = 535), we excluded individuals whose records had missing values (n = 137). Thus, data from 1,480 adolescents were analyzed.

Variables

Participants with a “yes” response to question “Have you ever been diagnosed with AD by a physician?” were included in the AD group. Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥95th percentile for the corresponding sex and age in the 2017 growth charts. Children with BMI between the 5th and 85th percentiles were regarded as the healthy group. BMI below the 5th percentile was considered underweight, while BMI between the 85th and 95th percentiles was considered overweight. The waist-to-height ratio was used as an abdominal obesity index; a ratio of ≥0.48 was considered indicative of abdominal obesity [14].

The region of residence was categorized as urban (Seoul, Busan, Daegu, Incheon, Gwangju, Daejeon, Ulsan, and Gyeonggi-do) or rural (Gangwon-do, Chungcheongbuk-do, Chungcheongnam-do, Jeollabuk-do, Jeollanam-do, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, and Jeju-do). Household income was classified into five categories, while stress level was classified into four categories. The presence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was recorded on the basis of a previous diagnosis by a physician; the presence of depression was recorded on the basis of a self-reported depressed mood for ≥2 consecutive weeks.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences in participant characteristics between the AD and non-AD groups were analyzed using Student’s t test and the χ2 test. Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard errors, while categorical variables are presented as proportions. Multiple logistic regression analysis (including age, sex, region of residence, number of household members, economic status, and stress level) was used to evaluate the relationships of obesity and abdominal obesity with AD. All p values of less than 0.05 were considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

The general characteristics of AD and non-AD groups are shown in Table 1. Mean BMI was slightly higher in the AD group than in the non-AD group (22.09 ± 4.24 kg/m2 vs. 21.49 ± 3.87 kg/m2), but the difference was not statistically significant. The prevalence of abdominal obesity did not differ between the groups. There were no significant differences between AD and non-AD groups in terms of economic status, depression, ADHD, or stress level. In univariate analysis, adolescents with AD had significantly higher levels of total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), compared with adolescents who did not have AD (168.47 ± 2.24 mg/dL vs. 162.45 ± 0.99 mg/dL, p = 0.010 and 138.66 ± 4.66 mg/dL vs. 114.0 ± 4.90 mg/dL, p = 0.003, respectively) (Table 1). In multiple logistic regression analysis, dyslipidemia (LDL-C level ≥130 mg/dL) [15] was a risk factor for AD (adjusted odds ratio, 1.03; 95% confidence interval, 1.01–1.05) after adjustments for age, sex, region of residence, number of household members, economic status, BMI, abdominal obesity, lipid profile, depression, ADHD, and stress level. However, a high TC level (≥200 mg/dL) was not a risk factor for AD (adjusted odds ratio, 1.45, 95% confidence interval, 0.91–2.32) (Table 2).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | Doctor-diagnosed atopic dermatitis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| no (n = 1,253) | yes (n = 227) | p value | |

| Age, years | 15.27±0.06 | 15.11±0.16 | 0.306 |

| Gender | 0.262 | ||

| Female | 52.8 (1.5) | 48.3 (3.8) | |

| Male | 47.2 (1.5) | 51.7 (3.8) | |

| Region | 0.801 | ||

| Urban | 68.6 (2.2) | 69.6 (4.2) | |

| Rural | 31.4 (2.2) | 30.4 (4.2) | |

| Number of household members | 0.061 | ||

| ≤3 | 29.1 (1.6) | 22.6 (3.0) | |

| ≥4 | 70.9 (1.6) | 77.4 (3.0) | |

| Economic state | 0.939 | ||

| Lowest | 6.1 (0.8) | 5.2 (1.9) | |

| Middle-low | 15.5 (1.3) | 17.8 (2.9) | |

| Middle | 25.4 (1.8) | 25.9 (3.5) | |

| Middle-high | 28.6 (1.7) | 27.7 (3.7) | |

| Highest | 24.5 (1.8) | 23.5 (3.3) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.49±3.87 | 22.09±4.24 | 0.100 |

| Underweight (<5 percentile) | 8.4 (1.0) | 7.3 (1.8) | 0.208 |

| Healthy (5–85 percentile) | 69.9 (1.5) | 67.4 (3.9) | |

| Overweight (85–95 percentile) | 9.5 (1.0) | 7.4 (1.9) | |

| Obese (≥95 percentile) | 12.3 (1.2) | 17.9 (3.1) | |

| Abdominal obesity | 0.107 | ||

| No (WHtR <0.48) | 82.1 (1.3) | 76.6 (3.5) | |

| Yes (WHtR ≥0.48) | 17.9 (1.3) | 23.4 (3.5) | |

| Lipid profiles, mg/dL | |||

| Total cholesterol | 162.45±0.99 | 168.47±2.24 | 0.010 |

| Triglyceride | 87.63±1.62 | 92.29±5.02 | 0.340 |

| LDL-cholesterol | 114.0±4.90 | 138.66±4.66 | 0.003 |

| Physical activity, days/weeks | 1.18±1.85 | 1.10±1.64 | 0.579 |

| Depression | 0.858 | ||

| No | 91.8 (0.9) | 91.4 (1.9) | |

| Yes | 8.2 (0.9) | 8.6 (1.9) | |

| ADHD | 0.191 | ||

| No | 98.7 (0.4) | 97.5 (1.1) | |

| Yes | 1.3 (0.4) | 2.5 (1.1) | |

| Stress level | 0.714 | ||

| No | 13.9 (1.1) | 13.9 (2.6) | |

| Mild | 60.4 (1.6) | 56.9 (3.7) | |

| Moderate | 22.3 (1.4) | 26.1 (3.4) | |

| Severe | 3.3 (0.6) | 3.0 (1.0) | |

Values are presented as percent (%) or means ± standard error.

BMI, body mass index; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio; LDL-cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression analysis with complex sampling of atopic dermatitis among Korean adolescents

| aOR (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.221 | |

| Female | 1 (reference) | |

| Male | 0.80 (0.56–1.15) | |

| Region | 0.702 | |

| Urban | 1 (reference) | |

| Rural | 0.93 (0.64–1.36) | |

| Number of household members | 0.121 | |

| ≤3 | 1 (reference) | |

| ≥4 | 1.36 (0.92–2.00) | |

| Depression | 0.785 | |

| No | 1 (reference) | |

| Yes | 1.08 (0.61–1.94) | |

| Lipid profiles | ||

| Total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dL | 1.45 (0.91–2.32) | 0.116 |

| LDL-cholesterol ≥130 mg/dL | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.003 |

This model was adjusted by age, sex, region of residence, number of household members, economic state, BMI, abdominal obesity, lipid profiles, depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and stress level.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; LDL-cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

AD was diagnosed more often in obese adolescents than in non-obese adolescents (20.8% vs. 14.5%, p = 0.055). This tendency was more obvious in male adolescents than in female adolescents, but the association was not statistically significant. In multiple logistic regression analysis, obesity and abdominal obesity were not significant risk factors for AD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between obesity, abdominal obesity, and atopic dermatitis among Korean adolescents

| Doctor-diagnosed atopic dermatitisa | Multivariable logistic regressionb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| non-obese | obesec | p value | obesityc | p value | abdominal obesityd | p value | |

| All subjects | 14.5 (1.2) | 20.8 (3.1) | 0.055 | 1.43 (0.77–2.66) | 0.254 | 1.12 (0.64–1.96) | 0.695 |

| Female | 16.2 (1.2) | 20.7 (3.1) | 0.383 | 1.22 (0.52–2.84) | 0.646 | 1.95 (0.87–4.38) | 0.103 |

| Male | 13.0 (1.2) | 20.9 (3.1) | 0.054 | 2.05 (0.78–5.38) | 0.143 | 1.19 (0.50–2.86) | 0.693 |

aValues are presented as prevalence (%).

bThis model was adjusted by age, sex, region of residence, number of household members, economic state, body mass index (BMI), abdominal obesity, lipid profiles, depression, physical activity, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and stress level. Values are presented as adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval).

cBMI ≥95th percentile.

dWaist-to-height ratio ≥0.48.

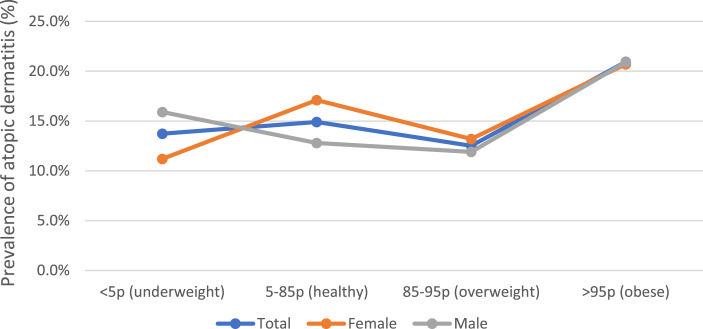

AD prevalence trends differed between sexes when participants were classified according to BMI (<5th percentile, 5th percentile to 85th percentile, 85th percentile to 95th percentile, and >95th percentile) (Fig. 1). The obese group had the highest AD prevalence in both sexes, while the lowest AD prevalence was observed in the underweight group among female adolescents and in the overweight group among male adolescents. However, the association was not statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

Trends of atopic dermatitis prevalence with BMI percentile.

Discussion

In this study, we confirmed that a higher LDL-C level was significantly associated with AD in Korean adolescents. In univariate analysis, TC levels were also higher in adolescents with AD than in adolescents without AD. However, a high TC level (≥200 mg/dL) was not a risk factor for AD in multiple logistic regression analysis. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies of associations between lipid levels and AD. Mean serum lipid levels were higher in patients with severe AD than in AD patients overall, but these differences were only statistically significant for TC and triglyceride levels [16]. In a study of Chinese adults, lower serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and higher LDL-C levels were associated with an increased risk of allergic sensitization, particularly in men [17]. In contrast, a study in Germany showed positive associations between HDL-C levels and atopic diseases [18].

In the present study, obesity and abdominal obesity were not associated with AD prevalence in Korean adolescents. These results were consistent with prior studies that found no association between obesity and AD [9, 10, 19]. Several studies have demonstrated a positive association between obesity and AD [5, 20]; some of those studies also found a positive association between obesity (or high BMI) and AD severity. One study showed that moderate to severe AD was associated with a BMI of ≥97th percentile; moreover, AD was associated with central obesity [21]. A recent study found that AD patients had slightly higher BMI, compared with healthy controls; severe AD patients had significantly higher BMI, compared with AD patients overall [16]. In the present study, we could not analyze the association between obesity and AD severity because severity data were not included in the KNHANES dataset.

The reasons for discrepant findings among studies are unclear; however, the results may have been influenced by study population, region, and age. A few Korean studies have demonstrated an association between obesity/overweight and AD. Overweight was positively associated with AD in Korean adolescents [20]. In a study of Korean elementary school students, obesity among male students was a significant risk factor for AD [22]. In studies of school children, overweight or high BMI was associated with a greater prevalence of asthma and rhinitis but not a greater prevalence of AD [9, 10]. In the present study, obesity was associated with a greater prevalence of asthma in children aged 2–11 years (data not shown), but not in adolescents.

Although the association between obesity and AD was not statistically significant, we found that AD prevalence trends differed between sexes when participants were classified as underweight, healthy, overweight, or obese. These trend differences were not observed in children aged 6–11 years (data not shown). In Japanese children, BMI demonstrated a U-shaped association with the prevalence of asthma but not the prevalence of eczema [19]. In a study of Korean adults [23], AD prevalence demonstrated a U-shaped association with BMI; it was significantly associated with a high BMI (≥30 kg/m2) in young adult women but not in men. In adulthood, obesity may be associated with AD, especially in women.

Thus far, the associations among AD, obesity, and lipid levels have been inconsistent, and the underlying mechanism has not been clarified. It has been suggested that obesity and hyperlipidemia induce pro-inflammatory immune responses [24, 25]. Consistent with this hypothesis, a recent study reported an association between AD and cardiovascular disease [26]. Immune responses substantially differed between obese mice and lean mice; obesity might have converted the classical type-2 T helper-predominant disease associated with AD to more severe disease with prominent T helper-17 inflammation [27].

Our study has important clinical implications for public health because dyslipidemia may be a modifiable risk factor for AD. The increasing prevalence of obesity and related complications in children and adolescents are global public health problems [28]. The increasing prevalence of dyslipidemia among Korean children and adolescents may be related to the adoption of a Western lifestyle, including a Westernized diet [15]. In addition, during coronavirus disease 2019-related closures, physical activity levels were greatly reduced, and many individuals experienced weight gain [12]. Both obesity and AD cause significant burdens on patients, their families, and society. Lifestyle modifications, such as a healthy diet and regular physical activity, may be useful in the prevention and management of AD.

The present study is significant in that it analyzed nationally representative data from the KNHANES. However, it also had some limitations. First, this study was a cross-sectional analysis that could not assess the directions of relationships between AD and risk factors. Second, the KNHANES data were collected using a self-report questionnaire and may be subject to recall bias. Third, the KNHANES did not collect data regarding AD severity, which prevented analysis of differences based on severity. Finally, although pubertal development status may be associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome, it was not investigated in this study. Further large-scale prospective studies are needed to clarify the association between AD and metabolic syndrome, including the influences of obesity and dyslipidemia.

In conclusion, we did not find a statistically significant relationship between obesity and AD prevalence in Korean adolescents. However, a high LDL-C level (≥130 mg/dL) was a risk factor for AD, suggesting that dyslipidemia may be associated with AD development. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm the association between obesity and AD; such studies should also investigate whether appropriate management of obesity in childhood and adolescence could improve AD.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical approval and consent were not required as this study was based on publicly available data.

Conflict of Interest Statement

There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

This study was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Author Contributions

Min Kyeong Seong and Meeyong Shin contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results, and to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Data Availability Statement

Data analyzed during this study are openly available in [the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey] at https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/main.do. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Nutten S. Atopic dermatitis: global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(Suppl 1):8–16. 10.1159/000370220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mallol J, Crane J, von Mutius E, Odhiambo J, Keil U, Stewart A, et al. The international study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC) phase three: a global synthesis. Allergol Immunopathol. 2013;41(2):73–85. 10.1016/j.aller.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reed B, Blaiss MS. The burden of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018;39(6):406–10. 10.2500/aap.2018.39.4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mortz CG, Andersen KE, Dellgren C, Barington T, Bindslev-Jensen C. Atopic dermatitis from adolescence to adulthood in the TOACS cohort: prevalence, persistence and comorbidities. Allergy. 2015;70(7):836–45. 10.1111/all.12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Silverberg JI, Kleiman E, Lev-Tov H, Silverberg NB, Durkin HG, Joks R, et al. Association between obesity and atopic dermatitis in childhood: a case-control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(5):1180–6.e1. 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ascott A, Mansfield KE, Schonmann Y, Mulick A, Abuabara K, Roberts A, et al. Atopic eczema and obesity: a population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(5):871–9. 10.1111/bjd.19597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang A, Silverberg JI. Association of atopic dermatitis with being overweight and obese: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(4):606–16.e4. 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sybilski AJ, Raciborski F, Lipiec A, Tomaszewska A, Lusawa A, Furmańczyk K, et al. Obesity: a risk factor for asthma, but not for atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis and sensitization. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(3):530–6. 10.1017/S1368980014000676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saadeh D, Salameh P, Caillaud D, Charpin D, de Blay F, Kopferschmitt C, et al. High body mass index and allergies in schoolchildren: the French six cities study. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2014;1(1):e000054. 10.1136/bmjresp-2014-000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Song N, Shamssain M, Zhang J, Wu J, Fu C, Hao S, et al. Prevalence, severity and risk factors of asthma, rhinitis and eczema in a large group of Chinese schoolchildren. J Asthma. 2014;51(3):232–42. 10.3109/02770903.2013.867973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ali Z, Suppli Ulrik C, Agner T, Thomsen SF. Is atopic dermatitis associated with obesity? A systematic review of observational studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(8):1246–55. 10.1111/jdv.14879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kang HM, Jeong DC, Suh BK, Ahn MB. The impact of the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic on childhood obesity and vitamin D status. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(3):e21. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):69–77. 10.1093/ije/dyt228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim MS, Kim SY, Kim JH. Secular change in waist circumference and waist-height ratio and optimal cutoff of waist-height ratio for abdominal obesity among Korean children and adolescents over 10 years. Korean J Pediatr. 2019;62(7):261–8. 10.3345/kjp.2018.07038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lim JS, Kim EY, Kim JH, Yoo JH, Yi KH, Chae HW, et al. 2017 Clinical practice guidelines for dyslipidemia of Korean children and adolescents. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2020;25(4):199–207. 10.6065/apem.2040198.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agón-Banzo PJ, Sanmartin R, García-Malinis AJ, Hernández-Martín Á, Puzo J, Doste D, et al. Body mass index and serum lipid profile: association with atopic dermatitis in a paediatric population. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61(1):e60–4. 10.1111/ajd.13154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ouyang F, Kumar R, Pongracic J, Story RE, Liu X, Wang B, et al. Adiposity, serum lipid levels, and allergic sensitization in Chinese men and women. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(4):940–8.e10. 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schäfer T, Ruhdorfer S, Weigl L, Wessner D, Heinrich J, Döring A, et al. Intake of unsaturated fatty acids and HDL cholesterol levels are associated with manifestations of atopy in adults. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33(10):1360–7. 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanaka K, Miyake Y, Arakawa M, Sasaki S, Ohya Y. U-shaped association between body mass index and the prevalence of wheeze and asthma, but not eczema or rhinoconjunctivitis: the ryukyus child health study. J Asthma. 2011;48(8):804–10. 10.3109/02770903.2011.611956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lim MS, Lee CH, Sim S, Hong SK, Choi HG. Physical activity, sedentary habits, sleep, and obesity are associated with asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis in Korean adolescents. Yonsei Med J. 2017;58(5):1040–6. 10.3349/ymj.2017.58.5.1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Silverberg JI, Becker L, Kwasny M, Menter A, Cordoro KM, Paller AS. Central obesity and high blood pressure in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(2):144–52. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim E, Ri S, Seo SC, Choung JT, Yoo Y. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis and its associated factors for elementary school children in Gyeonggi-do province. Allergy Asthma Respir Dis. 2016;4(5):346–53. 10.4168/aard.2016.4.5.346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee JH, Han KD, Jung HM, Youn YH, Lee JY, Park YG, et al. Association between obesity, abdominal obesity, and adiposity and the prevalence of atopic dermatitis in young Korean adults: the Korea national health and nutrition examination survey 2008–2010. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016;8(2):107–14. 10.4168/aair.2016.8.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1796–808. 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Al-Shawwa B, Al-Huniti N, Titus G, Abu-Hasan M. Hypercholesterolemia is a potential risk factor for asthma. J Asthma. 2006;43(3):231–3. 10.1080/02770900600567056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Silverberg JI. Comorbidities and the impact of atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123(2):144–51. 10.1016/j.anai.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bapat SP, Whitty C, Mowery CT, Liang Y, Yoo A, Jiang Z, et al. Obesity alters pathology and treatment response in inflammatory disease. Nature. 2022;604(7905):337–42. 10.1038/s41586-022-04536-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, McPherson K, Finegood DT, Moodie ML, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data analyzed during this study are openly available in [the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey] at https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/main.do. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.