Abstract

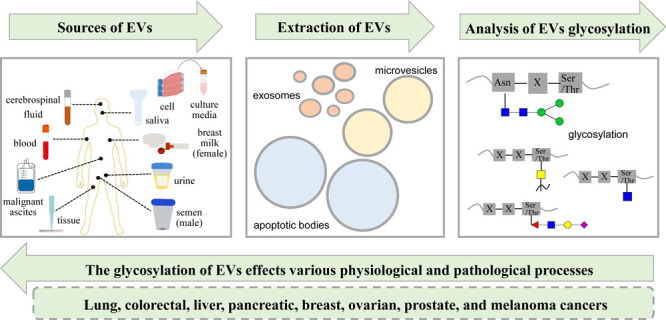

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are membranous structures secreted by various cells carrying diverse biomolecules. Recent advancements in EV glycosylation research have underscored their crucial role in cancer. This review provides a global overview of EV glycosylation research, covering aspects such as specialized techniques for isolating and characterizing EV glycosylation, advances on how glycosylation affects the biogenesis and uptake of EVs, and the involvement of EV glycosylation in intracellular protein expression, cellular metastasis, intercellular interactions, and potential applications in immunotherapy. Furthermore, through an extensive literature review, we explore recent advances in EV glycosylation research in the context of cancer, with a focus on lung, colorectal, liver, pancreatic, breast, ovarian, prostate, and melanoma cancers. The primary objective of this review is to provide a comprehensive update for researchers, whether they are seasoned experts in the field of EVs or newcomers, aiding them in exploring new avenues and gaining a deeper understanding of EV glycosylation mechanisms. This heightened comprehension not only enhances researchers’ knowledge of the pathogenic mechanisms of EV glycosylation but also paves the way for innovative cancer diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

1. Introduction

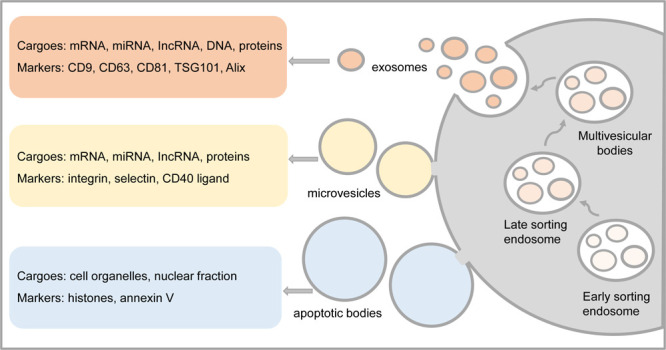

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are membranous vesicles enclosed by a phospholipid bilayer that are produced and secreted by various cell types and contain a wide array of biomolecules.1 EVs are commonly categorized into three major subtypes based on their size, biological characteristics, and production mechanisms: exosomes (Exos, 50–150 nm), microvesicles (MVs, 150–1000 nm), and apoptotic bodies (ApoBDs, 1–5 μm).26 Thereinto, Exos are formed by the fusion of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and the cell membrane, whereas MVs are released by pinching off the cell membrane via outward budding and apoptotic bodies are delivered during the process of cell apoptosis with undetermined origin (Figure 1).7,8 The distinct markers present on EV subtypes allow for their differentiation, highlighting their vital significance in both physiological and pathological processes.9 Evidence from studies suggests that EVs are abundant sources of biomarkers, with exploratory analysis of EVs holding promise for enhancing early disease diagnosis, treatment strategies, and prognostic evaluations.

Figure 1.

Formation, cargos, and markers of extracellular vesicles. The color orange represents exosomes, yellow represents microvesicles, and blue represents apoptotic bodies.

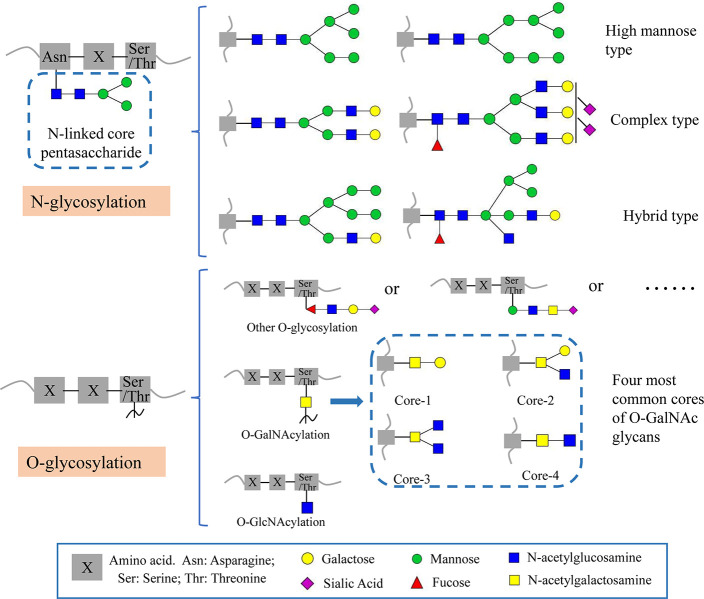

Glycosylation, a common post-translational modification (PTM) of proteins, occurs in eukaryotic cells with the aid of glycosyltransferases.10−12 This modification encompasses N-glycosylation, O-glycosylation, C-glycosylation, and the glycosylated phosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins, and each category is defined based on how glycans are linked to proteins.13 The first two categories are of greater concern in glycosylation (Figure 2). N-glycosylation involves attaching N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) to the nitrogen atom of the protein’s asparagine side chain through an amide bond, typically with the specific amino acid sequence Asn–X–Ser/Thr. This modification can be further categorized into high mannose type, complex type, and hybrid type based on the branching pattern of the glycan chain.14O-glycosylation predominantly occurs at the hydroxyl group of serine or threonine side chains and usually does not have specific amino acid sequences. The extensively studied forms of the O-glycosylation are O-GalNAc and O-GlcNAc.15 Glycosylation is one of the most prevalent PTMs, and glycoproteins are major biomolecules extensively distributed across the surfaces of plasma membranes and cell membranes.16 Glycosylation can alter the conformation, physicochemical properties, and stability of proteins, thereby impacting various physiological processes, including cancer cell proliferation, metastasis, apoptosis, and immune evasion.12,14,17,18 Furthermore, it holds a significant association with the development of numerous diseases.12,19 Remarkably, tumor-derived EVs have been discovered to contain an enrichment of tumor-associated glycans, and glycosylation has been identified as a potent influencer of the biosynthesis and function of EVs, highlighting the potential of EV glycosylation to serve as the viable source of biomarkers.20

Figure 2.

N-glycosylation types and O-glycosylation types of glycoproteins.

Glycosylation can occur on biomolecules, including proteins, lipids, DNA, and more. In this review, we specifically highlight recent advancements in the study of the glycosylation of EVs, covering analytical methods, biological functions, and applications in cancer.

2. The Research of Glycosylation in EVs

EVs are not confined to their initial perception as mere waste carriers at the first time of discovery. In contrast, they play crucial roles in a variety of physiological and pathological events, including immune responses, cellular differentiation, cellular metastasis, and so on.2,5,6 The contents of EVs cargoes, especially glycoproteins, fluctuate with the state of the cells; they serves as a mirror of cellular events and states, conveying information that influences neighboring cells and the surrounding environment.21 The research of glycosylation in EVs holds substantial clinical significance and has garnered increasing attention in recent years.

2.1. Extraction and Analysis of EVs and Glycosylation

While numerous proteins on the surface of EVs have been identified as highly glycosylated, these vesicles are encompassed by an intricate humoral environment.22−24 Consequently, the assessment of their glycoprotein content is susceptible to disruption by various other constituents. Hence, conducting an exhaustive glycoproteome analysis of EVs necessitates the initial purification of these vesicles from the sample, followed by the enrichment of glycosylated proteins.11 Continued technological and experimental advances have unveiled the heterogeneity and diversity of EV glycosylation, thus facilitating their utilization for the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of related diseases. The following section delineates the advancements in research methodologies employed for the separation and analysis of EVs and glycosylation.

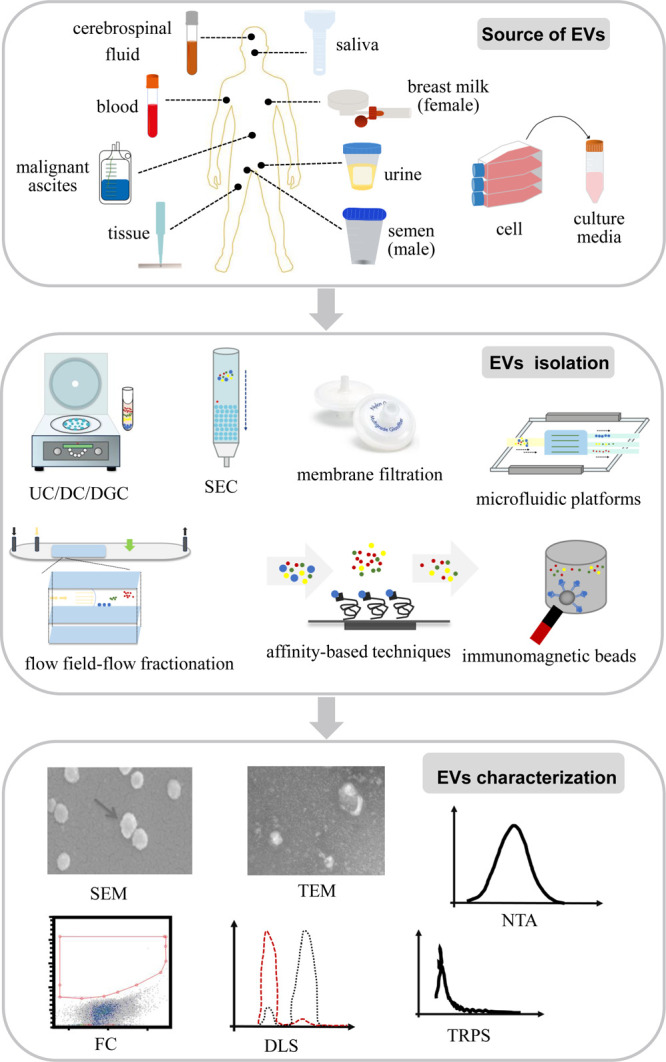

2.1.1. Methods to Isolate and Characterize EVs

EVs are produced by various types of cells and are consistently found in body fluids, including blood, saliva, urine, semen, breast milk, malignant ascites, and cerebrospinal fluid, as well as tissue and cell culture media.22,25 Up to the present, researchers in relevant fields have proposed several predominant techniques for isolating EVs from complex biological samples (Figure 3). These methods include ultracentrifugation (UC),26 differential ultracentrifugation (DC),27,28 density gradient centrifugation (DGC),29 size exclusion chromatography (SEC),30 membrane filtration,31 microfluidic platforms,32 flow field-flow fractionation,33 affinity-based techniques,34 and immunomagnetic bead enrichment.35,36 Among these methods, UC is regarded as the gold standard,37 and the combination of these techniques has been documented to yield high-quality EVs.38−41 While each of these methods presents its own set of advantages and disadvantages,42−44 based on the scope detailed in the present study, these isolation approaches can effectively purify EVs from complex biological samples to a certain degree. This enables both qualitative and quantitative analysis of the biomolecules carried by them.

Figure 3.

Sources, isolation, and characterization of extracellular vesicles.

The efficiency of the isolation of EVs can be characterized by assessing their physical properties (Figure 3), which have been extensively reported in the literature. These methods exhibit distinct advantages and disadvantages that are complementary in their application. For instance, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) generate high-resolution EV images despite limited throughput;45 nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) quantifies EVs concentration and size distribution but requires a specific camera and optimized settings;46−48 tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS) measures the concentration and size distribution of EVs by detecting transient changes in ionic currents, which occur as vesicles traverse nanopores;49,50 dynamic light scattering (DLS) assesses various physical attributes of EVs in suspension, but it requires special attention to conditions that may induce disturbances;51,52 and flow cytometry (FC) characterizes surface proteins and enables precise counting and sorting of EVs, exhibiting high reproducibility across various suspension fluids.27,53,54 Among these, TEM and NTA or TEM and FC are commonly combined for EV characterization.36,55

2.1.2. Methods to Enrich and Characterize Glycosylation

As mentioned above, it is crucial to perform EV purification prior to analyzing glycosylation. Besides, to prevent interference in glycosylation analysis, several enrichment methods for glycans and glycopeptides have been developed. These include size exclusion chromatography (SEC),56 hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC),57 boronic affinity chromatography (BAC),58 porous graphitized carbon (PGC),59 hydrazide chemistry,60 chemical labeling-based enrichment,61 and lectin-based affinity enrichment.62 These glycosylation enrichment methods facilitate the purification of EVs for subsequent analysis. The advantages and disadvantages of these enrichment techniques are extensively discussed in the fields of glycoproteomics and glycomics and will not be further elaborated upon here.10,63−65 The following section primarily focuses on reviewing the analytical methods for glycosylation.

After the enrichment of glycosylation from isolated EVs, glycoproteome and glycome characterization can be performed using multiple techniques (Table 1). Gas chromatography (GC) and liquid chromatography (LC) analyze carbohydrates based on distinctions between their physical properties, and these techniques are well suited for glycosylation analysis of a single glycoprotein.66−68 However, their ability to elucidate the structures of glycan chains is reliant on the presence of reference standards. Mass spectrometry (MS) identifies the glycan structures and glycosylation sites of glycoconjugates through the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of fragmentation ions, and the relative signal intensities can provide quantitative information.44,69−72 The emergence of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) and electron spray ionization (ESI) has advanced the application of MS in the field of macromolecular analysis, encompassing the analysis of glycoconjugates. MALDI-MS offers simplicity in sample pretreatment, rapid detection within seconds, and relatively high sensitivity.73−75 However, its compatibility with chromatography or other separation techniques is limited, making it primarily suitable for the analysis of glycosylation in uncomplicated samples. ESI-MS, including LC-MS, CE-MS and IMS, is compatible with a range of separation techniques, making it well suited for glycosylation analysis of intricate samples.61,76−79 However, it has drawbacks, such as being time-consuming, low throughput, high cost, and the generation of complex spectra, that make it analysis challenging. Western blotting (WB) is a prevalent technique to achieve qualitative, semiquantitative, and validation analysis based on antiglycan antibodies, but its quantitative accuracy and reproducibility are relatively limited.80−82 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is based on the principle of antigen–antibody binding, quantified by fluorescence or luminescence signal intensity.83−85 ELISA is a well-established and reproducible technique with a wide range of applications, but it is limited to the analysis of known substances. Lectins bind and recognize carbohydrates structures, which can be employed to analyze specific glycoproteins and glycans with high sensitivity.22,86−89 However, the method exhibits relatively low accuracy and is susceptible to inhibition and interference from other oligosaccharide structures. Fluorescence detection by conjugates emission is sensitive and rapid, but it requires a specific fluorescent tag because carbohydrates do not absorb visible light, thereby significantly restricting its application.66,90

Table 1. Overview of Glycosylation in EV Analysis Methodsa.

| method | principle | advantages | disadvantages | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC LC | physical properties of analyzed samples | suitable for analysis of a single glycoprotein | require standards to decode the glycosylation structures | (66−68) |

| MALDI-MS | identification of the glycan structures and glycosylation sites by m/z of fragments | simple and fast, only a few seconds, high sensitivity | incompatible with chromatography, only useful for glycosylation analysis in simple samples | (73−75) |

| ESI-MS | compatible with multiple chromatography, suitable for glycosylation analysis in complex samples | time-consuming, low throughput, high cost, complex spectra, difficult to decode | (78, 79, 92) | |

| WB | transfer glycoproteins to membranes and detect with antiglycan antibodies | qualitative and semiquantitative analysis, validation analysis of glycoproteins | poor accuracy and reproducibility in quantification, antibody-dependent | (80, 82) |

| ELISA | antigen–antibody binding, quantification by fluorescence or luminescence signals | mature technology with good reproducible results, suitability for detecting extracellular secreted proteins | quantitative analysis of glycoproteins and glycans with known glycans structures | (83−85) |

| lectin-based method | lectins bind and recognize the carbohydrates structures | high sensitivity, lectin arrays with high throughput | low accuracy, disturbed and inhibited by other monosaccharide structures | (86,87,89,93) |

| fluorescence detection | detection by conjugates emission | fast, high resolution | requires fluorescent labeling prior to detection | (90, 94) |

The abbreviations in the table are explained with the corresponding full names as follows: GC, gas chromatography; LC, liquid chromatography; MALDI-MS, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionizationmass spectrometry; ESI-MS, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry; WB, Western blotting; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; and ref, references.

Currently, the assignment of glycan structures to specific glycosylation sites is primarily accomplished through high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS).91 As of now, none of these techniques can fully substitute for the others, and researchers can select the most appropriate analytical technique based on the specific objectives of their experiment. As mentioned above, there are many methods for the isolation and analysis of glycosylation of EVs, and the selection or combination of different techniques significantly influences the downstream results; however, there is currently no consensus on the “best approach”. The following viewpoints are widely acknowledged and embraced by the majority: researchers tend to prefer more complex isolation and analysis techniques, particularly for complex body fluids or when assessing the glycoproteome within EVs.

2.2. Glycosylation Influences the Biogenesis and Uptake of EVs

EVs are transport vesicles containing a trove of components and are secreted by cells in both physiological and pathological states.34,95,96 Various PTMs of proteins occur during EVs genesis, and they are expected to participate in a variety of biological processes.97 Carbohydrate-structured substances, such as oligosaccharides, polysaccharides, and glycoproteins, are essential components on the vesicle surface that play a role in regulating the biogenesis and the recipient cell uptake of EVs.11,20,98 In the next section, an overview of the research progress regarding glycomics analysis and glycoproteomics analysis shows that glycosylation compositional features are closely related to the biogenesis and uptake of EVs.

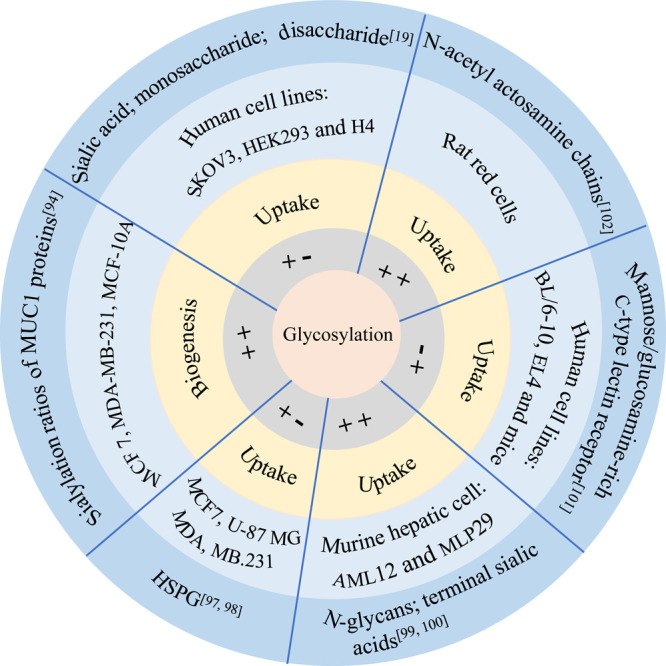

Although the mechanisms are not well understood, several papers have provided evidence that glycosylation affects the biogenesis and uptake of EVs (Figure 4). Guo et al. demonstrated distinct sialylation ratios of MUC1 proteins in both MCF7 and MDAMB231 parental cells and their corresponding EVs using their proposed quantitative localization analysis (QLA) method.97 The results of their experiments revealed that at least part of glycosylation plays a role in the biogenesis pathway of EVs. Fuentes et al. proved that ITGB3 impacted the uptake of EVs by activating endocytosis through interaction with heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG).99 After treating the murine hepatic cell lines (AML12 and MLP29) with glycosidase PNGase F or neuraminidase, the researchers revealed that there was no significant change in the size of the EVs, and the increased uptake of the EVs could be attributed to the charge effects, direct glycan recognition, or a combination of both.23,100 Exosomes, as a smaller subset of EVs, have garnered increasing attention for the effect of glycosylation on their uptake by recipient cells. Genetic evidence from the investigation of cell mutants indicated that HSPG acted as an internalized receptor for cancer cell-derived exosomes and that elevated levels of cell surface HSPG substantially enhanced the uptake of exosomes.101 Moreover, in dendritic cells, the uptake of exosomes was specifically attenuated by d-mannose and d-glucosamine, and this interaction was at least partially mediated by C-type lectins.102 In macrophages, 6N-acetylactosamine chains could inhibit exosome uptake by binding on galectin 5.103 In ovarian carcinoma SKOV3 cells, the removal of sialic acid led to an increase in exosome uptake. Conversely, treatment with high concentrations of monosaccharides or β-lactose resulted in decreased exosome uptake compared to glucose.21

Figure 4.

Schematic representation illustrating the influence of glycosylation on the biogenesis and uptake of EVs. In the gray circle, “++” indicates that glycosylation is positively correlated with EVs, whereas “+–” indicates that glycosylation is negatively correlated with EVs. In the orange ring, the text annotates the correlation between glycosylation and the biogenesis or uptake of EVs. In the light blue circle and the dark blue ring, the text annotates the sample of the study and the type of glycosylation, respectively.

2.3. The Biological Role of Glycosylation of EVs

Glycosylation, characterized by covalent and intricate heterogeneous linkages, has been proved to perform an irreplaceable function in the regulation of biological processes at the cellular level.12,89,91 EVs, which encompass a diverse range of cargos, have been reported to be involved in various biological processes. Proteins encapsulated within EVs often exhibit various types of glycosylation modifications.104 In the following section, we highlight the biological roles exerted by the glycosylation of EVs.

Glycosylation of EVs affects the expression of certain proteins associated with exosomes. For instance, core 1-mediated O-glycosylation regulated CD44 expression by modulating truncated O-glycoproteins released via exosomes. This resulted in the downregulation of CD44 expression intracellularly while upregulating CD44 expression within the exosomes. This finding also suggested that the high proportion of CD44-positive exosomes could potentially serve as a biomarker for aberrant O-glycosylation.36 In addition, the glycosylation of EVs has been found to influence the metastatic potential of certain cells. The glycocalyx, consisting of sugar-coated components such as glycoproteins, proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans, played a significant role in promoting angiogenesis and metastasis through EVs and held a pivotal position within the tumor microenvironment.105 The sialyltransferase ST6GAL1 could be released into the extracellular environment, where it added α-2,6-linked sialic acids to N-glycans on cell surfaces and secreted glycoproteins. In breast cancer, ST6GAL1 enhanced both growth and aggressiveness.106 The high bisecting GlcNAc on the surface of EVs led to the attenuation of the prometastatic function of breast cancer cells. This effect was achieved through the inhibition of galectin 3/vesicle β1 expression.3

Differences in glycomic profiles between the parental cells and secreted EVs are evident. Additionally, variations are observed in the surface glycomic profiles among exosome subpopulations. Therefore, the analysis of glycosylation in EVs is considered to be useful for studying interactions and glycoprotein sorting. Findings from localization and quantitative analysis studies revealed that the glycome signatures of EVs proteins differed from those of their parent cell membranes.97 This suggested that protein-specific glycome signatures could serve as factors for protein sorting. Further, these specific glycans took on an irreplaceable role in intercellular communications. Matsuda et al. reported that the secreted glycoproteins, membrane glycoproteins, and EVs glycoproteins of pancreatic cancer cell lines exhibited markedly different glycome signatures.16 Similarly, CD9-, CD63-, and CD81-positive exosomes shared varying glycome signatures. The experimental data above provide evidence that specific glycans likely play a role in sorting glycoproteins into vesicles. The broad-ranging glycosylation analysis of various types and sources of EVs could contribute to unraveling the mechanisms underlying the interactions between EVs and cells.

The comprehensive and in-depth analysis of EV glycosylation significantly contributes to the advancement of immunotherapy. EVs are characterized by their nanoscale size, biocompatibility, and prolonged circulatory half-life, rendering them valuable as delivery vehicles for drugs and small molecules.107 Furthermore, EV glycosylation not only mediatesphysiological functions through multiple mechanisms but also opens avenues for designing EVs for therapeutic and immunological applications.23 Efficient attachment of antigens to the surface of EVs could be facilitated by binding antigens to the transmembrane domains of viral glycoproteins, resulting in heightened immunogenicity.108 The presence of α-2,3-linked sialic acids on B cell-derived exosomes not only enhanced their recognition and capture of CD169-positive exosomes but also played a crucial role in promoting exosomal antigen-mediated immunity.109 Glycosylation also fostered the interaction between EVs and host immune cells, holding significance in immune regulation and vaccines development.110 Moreover, senescent cells release a higher number of EVs compared to nonsenescent cells, which are accompanied by distinct glycan profiles on their surfaces. These differences enable senescent cells to induce specific types of cell lysis by selectively binding to lectins, potentially serving as a foundation for lectin-targeted therapies.111

3. EV Glycosylation in Cancers

According to the global cancer statistics 2020, the number of new cancer cases globally reached a concerning 19.3 million, resulting in a staggering loss of 9.9 million lives.112 This highlights the significant increase in cancer incidence and mortality, which places a heavy burden on healthcare systems, caregivers, and the global economy and affects the quality of life of patients, causing physical and psychological suffering. Therefore, there is an urgent need for in-depth research into the pathomechanisms of these cancers and the development of innovative early diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to combat this global threat.

Cancer-derived EVs share many common biological functions that impact multiple biological processes in the development and progression of the diseases. The alterations of glycosylation frequently occur during cancer progression. The study of glycosylation in EVs has revealed that cancer-derived EVs are enriched in disease-associated glycans.20 Compared to blood samples, the analysis of EV glycosylation prevented interference from high-abundance proteins, providing a wider dynamic range and higher sensitivity.113 The potential of EV glycosylation in the early diagnosis of disease is increasingly being evaluated, highlighting the value of the application of EVs as one of the most versatile biopsy samples for the discovery of specific diagnostic biomarkers.23,114,115 Notably, global analysis of EV glycosylation not only facilitates the discovery of diagnostic markers but also aids in understanding the causative mechanisms of diseases and contributes to the development of therapeutics.

In the following sections, we will provide an overview of recent advances in EV glycosylation in the research fields of lung, colorectal, liver, pancreatic, breast, ovarian, prostate, and melanoma cancer. The aim is to elucidate the pivotal discoveries in EV glycosylation and underscore its significance in advancing cancer research.

3.1. Lung Cancer

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represent the two most common subtypes of lung cancer.116,117 Notably, there are distinct differences in the N-glycomes of EVs released from SCLC cells and NSCLC cells. The structural motifs of N-glycans found in SCLC-released EVs resembled the brain N-glycans, while NSCLC-released EVs predominantly featured lung-specific N-glycans characterized by core fucosylation, a feature associated with NSCLC.118 Furthermore, lectin array analysis revealed the selective expression of integrins between these two cell types. These profiles suggest a molecular connection between the glycoproteins present in EVs and the types of lung cancer.

NSCLC accounts for approximately 80% of all lung cancer cases, and the treatment and prognosis of NSCLC largely depend on the disease stage.116,117 Unfortunately, many patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, emphasizing the critical need for novel diagnostic biomarkers to enhance both the quality of life and survival rates among NSCLC patients.119 Therefore, the search for novel diagnostic biomarkers is essential to improve the life quality and the survival rate of NSCLC. In the study by Li et al. proteomic analysis revealed that α-2-glycoprotein (LRG1) was upregulated in urinary exosomes from NSCLC patients and in tumor tissues.120 This suggested its potential as a biomarker for NSCLC. While this study did not include ROC curve analysis or diagnostic specificity assessments, it provided the possibility of identifying potential biomarkers for NSCLC at the subcellular level. Pan et al. isolated exosomes via UC and conducted semiquantitative proteomic analysis of exosomes derived from the nonsmall cell line NCI-H838.121 By comparing these exosomal proteins to whole cell membrane proteins, they found that while there was no significant difference in MUC1 levels in the plasma, MUC1 levels in plasma exosomes from NSCLC patients were 1.5-fold higher than those in healthy individuals. This study underscored the potential of plasma exosomal MUC1 as a sensitive diagnostic biomarker for NSCLC. Moreover, Niu et al. identified serum exosomal α-2-HS-glycoprotein (AHSG) and extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM1) as potential diagnostic markers for NSCLC.122 When combined with serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), the area under the curve (AUC) exceeded 0.9, indicating diagnostic and prognostic potential. These findings suggest that serum exosomes contain glycoproteins with valuable diagnostic and prognostic implications.

3.2. Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC), ranking as the third most prevalent malignant tumor, has significantly better survival and quality of life outcomes when diagnosed early.112 Studies have highlighted the potential of glycoconjugate analysis of EVs in human serum associated with CRC as a complementary approach to traditional methods, offering promise for early CRC diagnosis.123 Notably, α-1-acid glycoprotein 1 (ORM1) in human plasma EVs, linked to CRC subtypes, has emerged as a significant factor impacting overall survival and may serve as a key prognostic indicator.124

Detailed investigations into CRC-derived EV glycosylation have covered conditioned media, plasma, and tissues. For instance, Sun et al. isolated EVs from the plasma, cancer tissues, and paracancerous tissues of CRC patients.125 They analyzed the proteome and glycoproteome of the EVs using LC-MS/MS and found that levels of fibrinogen-β chain (FGB) and β-2 glycoprotein 1 (β2-GP1) were significantly elevated in cancer tissue-derived EVs and that FGB and β2-GP1 had more diagnostic potential than CEA and CA19–9. This study used late specimens (T2–T4), and future investigations of early specimens are warranted to determine the specificity of early diagnosis and to explore whether these biomarkers can be used for CRC subtyping and staging. In addition, Chaiyawat et al. isolated secreted proteins and EVs from conditioned media using DC and DGC, respectively.45 By removing N-glycans with PNGase F and O-GalNAc glycans via β-elimination, they isolated the O-GlcNAcylated proteins. Subsequent quantification through 2D gel electrophoresis and LC-MS/MS analysis revealed significantly elevated O-GlcNAcylation in EVs from metastatic CRC cell lines. This study suggests that aberrant O-GlcNAcylation of EV proteins might be involved in the process of cancer metastasis and could serve as a potential biomarker for metastatic CRC.

3.3. Liver Cancer

Among primary liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) comprises more than 75% of cases and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA) comprises more than 10%.112 Early diagnosis of both HCC and iCCA is critical for enhancing patient outcomes, as advanced-stage disease management is more limited and associated with significant side effects.126 At present, both the imaging tests and serum marker tests, which are more commonly used in clinical practice, lack perfect specificity and sensitivity. Researchers in related fields are actively developing new diagnostic markers for liver cancer, including studies on EV glycosylation, with the aim of enabling early diagnosis.

Lv et al. captured glycosylated peptides by reacting aldehyde-modified resins with the amino groups of peptides and then released the N-glycans using PNGase F, enabling MS analysis of the glycome in both serum and cellular exosomes.127 In this study, 77 N-glycans were identified in HCC serum exosomes compared to 74 N-glycans in healthy human serum exosomes, with 24 N-glycans showing differential expression. These findings suggest that profiling serum exosomal N-glycome may yield novel insights into potential HCC biomarkers. Li et al. identified 756 N-glycopeptides in urinary EVs and found that glycoproteins LG3BP, PIGR, and KNG1 are upregulated in HCC128.128 Although this study had a small sample size and the candidate markers were not validated, this study highlights the promise of site-specific glycomics analysis in the quest for new noninvasive diagnostic markers.

3.4. Pancreatic Cancer

Surgical resection is the only curative option for pancreatic cancer (PC).129 However, PC usually lacks noticeable symptoms in the early stages; thus, many patients are diagnosed when the cancer has spread to vital tissues and cannot be treated surgically, which leads to a poor prognosis and high mortality. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop specific liquid biomarkers for the early diagnosis of PC, which is of great clinical significance.

Cancer cells surviving in ascites often display cancer stem cell (CSC)-like features. and understanding the signaling associated with CSC-like cells is essential for addressing therapy-resistant diseases.130 EVs were abundantly secreted by CSC-like cells, creating a tumor-specific microenvironment within the peritoneal cavity. These EVs played pivotal roles in tumorigenesis, tumor growth, metastasis, angiogenesis, the formation of premetastatic niches, immunosuppression, drug resistance, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT).131 Research into the glycosylation of exosomes in PC ascites has suggested that glycosylation could contribute to early diagnosis and prognosis assessment. For instance, Melo et al. isolated exosomes using DC and identified significant enrichment of glypican-1 (GPC1) in tumor-derived exosomes through MS and FC.4 Their study demonstrated that GPC1-carrying circulating exosomes could serve as a potential biomarker for early PC diagnosis. Sakaue et al. employed a kit combined with UC to isolate exosomes from PC ascites.132 In their study, WB analysis revealed elevated expression of the CSC-associated protein CD133 in advanced PC ascites in comparison with gastric cancer and decompensated cirrhotic ascites. Lectin assay analysis further indicated a strong correlation between high glycosylation levels of CD133 and patient survival. These findings suggest that glycosylated CD133 in ascites exosomes holds promise as a prognostic biomarker for advanced PC.

Studies investigating the glycosylation of EVs in the serum of PC patients and in PC cell lines have been documented. Yokose et al. conducted an integrated analysis using lectin microarrays and ExoCounter to examine EVs in PC cell line cultures and serum samples from PC patients.133 Although the structure of the O-glycans needs to be further elucidated, glycomics analysis showed an increase in the number of O-glycans recognized by amaranthus caudatus agglutinin (ACA)/agaricus bisporus agglutinin (ABA) in EVs at the site of PC lesions and a significant decrease in these glycan alterations after surgical intervention, suggesting that they could serve as potential biomarkers for PC. Consequently, exploring the association between the number of O-glycan changes and biological information carried by nucleic acids such as DNA or miRNA is an interesting direction for future research.

3.5. Breast Cancer

Research emphasizes that early diagnosis of breast cancer (BC) improves patients’ five-year post-diagnosis survival.134 The emerging body of evidence highlights the integral role played by EV glycosylation in both the diagnosis and treatment of BC. This evidence opens up promising avenues for identifying and developing biomarkers for EV glycosylation.

In a glycoproteomics study, Chen et al. identified 1453 unique glycopeptides using label-free quantitative techniques, of which 20 glycopeptides were significantly overexpressed in EVs of BC patients and could serve as potential diagnostic markers.25 However, the authors did not demonstrate the diagnostic specificity and accuracy of these candidate biomarkers. Terava et al. developed a method using wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) to detect glycome patterns of human serum EVs glycoproteins and mucins.135 They found that the glycovariants CD63UEA, CA125WGA, and CA15–3WGA had the potential to differentiate between localized BCs and healthy controls and were superior to traditional glycoprotein tumor markers, such as CA125 and CA15–3. However, it is worth noting that most of the samples used in this study were from early stage BCs, and it was not possible to link these glycovariants to specific BC subtypes. The diagnostic performance of these glycovariant biomarkers needs validation in larger clinical cohorts.

Chemoresistance is an important cause of therapy failure in BC. Ma et al. found that a large number of transient receptor potential channel 5 (TrpC5)-containing EVs were present on the surface of adriamycin-resistant human breast cancer cells (MCF-7/ADM), but not in untreated patients.136 They hypothesized that circulating EVs promoted intercellular transport of TrpC5, leading to the production of the multidrug-resistant transporter protein P-glycoprotein, which, in turn, leads to chemoresistance. However, the authors also noted that the correlation between TrpC5-containing EVs and the clinical response to chemotherapy may not be entirely attributable to the role of TrpC5-containing EVs, and that further exploration is needed to determine the potential of TrpC5-containing EVs as a diagnostic biomarker for chemotherapy-resistant BC. Tan et al. utilized DGC to isolate EVs from BC cells and found that bisecting GlcNAc low-expressing EVs promoted carcinogenesis and metastasis.3 The authors also found that vesicular integrin β1 is a target protein of bisecting GlcNAc and that high expression of bisecting GlcNAc strongly inhibited cells metastasis. This suggests that glycosylation modification of EVs affects their biological functions, and the analysis of EV glycosylation is expected to identify new therapeutic targets for BC.

3.6. Ovarian Cancer

In comparison to whole cell membranes, EVs derived from ovarian cancer (OC) cells exhibit distinct glycosignatures, including complex N-glycans with α-2,3-linked sialic acid, fucose, bisecting-GlcNAc, and LacdiNAc structures and O-glycans with the T-antigen.137 These specific glycosignatures hold potential as new biomarkers for OC.

The glycosylated macromolecules found in exosomes from OC patients have garnered significant attention, e.g., CD24 and EpCAM have been reported as potential diagnostic markers.138,139 In addition, Escrevente et al. conducted studies involving carboxyfluoresceine diacetate succinimidyl ester-labeled exosomes from SKOV3 cells isolated by UC.21 They employed immunofluorescence microscopy and FC to investigate exosome uptake by recipient cells under several different conditions, complemented by lectin analysis, to characterize the glycosylation patterns of these exosomes. Their research revealed that exosomes were enriched in high mannose-type and sialic acid-type glycoproteins, influencing their uptake via endocytosis. These glycoproteins hold promise as potential OC biomarkers. Escrevente et al. delved into the glycoproteome and N-glycome of exosomes derived from SKOV3 cells by lectin imprinting, NP-HPLC analysis, and MS.66 Their investigations identified abundant glycoproteins with sialic acid, particularly galectin-3-binding proteins, in SKOV3-derived exosomes. These proteins were confirmed to play an important role in interactions between exosomes and target cells, influencing EV uptake by recipient cells. The characterization of the N-glycome in exosomes revealed predominantly high-mannose glycans and complex glycans with multiantennary. These studies shed light on the potential of exosomal glycosylation as a biomarker for OC. Gomes et al. isolated EVs and total cell membranes from OVMz ovarian carcinoma cells using DC.137 Their analysis, employing immunoblot analysis, SDS-PAGE analysis, and MALDI-TOF/TOF analysis, unveiled disparities in glycoprotein abundance and glycosylation patterns between exosomal vesicles and total cell membranes. They discovered that galectin-3 binding protein (LGALS3BP), which contains a complex N-glycan structure, was highly enriched in EVs. Literature reports indicated that LGALS3BP is significantly overexpressed in patients with advanced stage disease, metastasis, and poor chemotherapeutic outcomes.140 The above evidence suggests that glycosylation profiling of EVs is beneficial for exploring the potential biomarkers of OC.

3.7. Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most common malignant tumors in the male population, with a significant global incidence and mortality rate.141 While prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is mentioned as a marker for prostate cancer, it is important to note that PSA testing has its limitations in both sensitivity and specificity.142 In recent years, researchers have increasingly focused on understanding the significance of glycosylation in improving the accuracy of PCa diagnosis. In the field of glycosylation studies of EVs derived from pancreatic cancer cell lines, Sandvig et al. found that the expression of glycoprotein CUB-containing domain protein 1 in EVs released from the metastatic PCa cell line PC-3 was specific by proteomic analysis.143 In addition, Clark et al. combined extracellular vesicle characterization and quantitative proteomics to study wild-type and FUT8 knockout pancreatic cancer cell models.144 They discovered that overexpression of α 1,6-fucosyltransferase FUT8 in pancreatic cancer cells led to altered glycans on EV surface glycoproteins, which in turn affected the production of extracellular vesicles associated with PCa progression. These emerging evidence strongly indicates that abnormalities in the glycosylation of EVs are closely linked to the development and progression of prostate cancer.

As a result, research into the glycosylation of EVs obtained from biopsy samples of pancreatic cancer patients has gained significant traction. Nyalwidhe et al. conducted an in-depth analysis of glycosylation in EVs from expressed prostatic secretions and urinary exosomes by employing three complementary analytical methods: MALDI-TOF, HPLC, and Triple Quadrupole MS.145 Their findings indicated that patients had significantly lower levels of tri- and tetraantennary N-glycans in prostate fluid exosomes and higher levels of bisecting N-acetylglucosamines, which are associated with disease progression. It is important to note, however, that the samples used in this study were pooled samples; therefore, no definitive conclusions can be drawn at this stage. Vermassen et al. identified an increased number of extracellular vesicles in the urine of pancreatic cancer patients compared to healthy individuals.146 Furthermore, they established a correlation between prostate protein N-glycosylation and the extraction rate of urinary-vesicle-associated prostate-specific antigen. Remarkably, despite the lower sensitivity and specificity, this association demonstrated greater clinical diagnostic value when compared to serum PSA levels and urine glycoprotein profiles. Blaschke et al. introduced an innovative method for N-glycome analysis of EVs in urine and prostate fluid.73 This method has the capability to detect up to 100 N-glycans and has demonstrated its utility across various biological sample types. Notably, its capacity to analyze a large population of clinical samples effectively expands the potential clinical applications of extracellular vesicle N-glycosylation analysis.

3.8. Melanoma

Melanoma of the skin had a worldwide incidence of 324,635 new cases, accounting for 1.7% of all cancer cases in 2020.112 It is a highly aggressive and lethal disease with no available cure, and experts agree that early diagnosis and treatment can dramatically reduce mortality.147 Clinical diagnostic methods for melanoma include visual observation, palpation, and sonographical examination, but they often have limitations in achieving precise early diagnosis.147 Recent studies have revealed that extracellular vesicles transport cargo that facilitates angiogenesis and mechanistic remodeling. This process enables cancer cells to evade immune responses, a pathway closely linked to melanoma metastasis and progression.148 Therefore, the investigation of extracellular vesicle glycosylation has emerged as a prominent area of interest in melanoma research.

Surman et al. isolated ectosomes from cutaneous melanomas through UC.149 They employed a panel of lectins, combined with WB and FC, to compare glycoproteins among ectosomes, whole-cell extracts, and membranes. As a result, the study revealed that ectosomes exhibited variations in specific glycan epitopes, either enriched or deleted. Furthermore, the authors indirectly suggested that ectosomes from distinct cell membrane regions harbored unique glycosylated structures. If confirmed, this finding implies a potential role of glycosylated protein structures in regulating vesicle numbers, which could be of clinical significance. Subsequently, Surman et al. also established the LC-MS/MS approach to perform the initial analysis of the ectosomal N-glycome released by uveal melanoma Mel202 cells.150 They identified distinct glycan patterns between Mel202 cells and secreted ectosomes. These ectosomes were enriched in bisected complex-type N-glycans and α-2,6-linked sialic acids, which may be associated with ectosome formation and interactions. Harada et al. employed UC to isolate EVs from three distinct mouse melanoma B16 variants, each with varying metastatic potentials.151 They conducted an analysis of 2-aminopyridine (PA)-labeled N-glycans using MALDI-TOF MS. This study yielded the initial qualitative and quantitative characterization of intricate glycan structures within the three B16 variants, contributing to the extended exploration of the N-glycome within tumor-derived EVs. Specific modification of the glycocalyx allowed high levels of mannose to be expressed on extracellular vesicles generated after apoptosis. These vesicles delivered tumor-specific antigens and initiated the T-cell immune response.152 Together, these findings hold promising clinical potential for the early diagnosis and T-cell-based immunotherapy of melanoma.

4. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

This review summaries the diversity and importance of methods for the study of EV glycosylation, where modern advanced techniques including FC and MS provide powerful tools for in-depth study of EV glycosylation.5 Continuous improvement and standardization of EV glycosylation analysis methods have enhanced sensitivity and specificity and reduced data discrepancies between different laboratories. Coupled with the establishment of pertinent databases, this facilitates data comparison and sharing across studies. Studies have shown that EV glycosylation significantly influences not only the biogenesis and uptake of these vesicles but also their biological functions and signal transduction, thereby playing a key role in both physiological and pathological processes. Future research should prioritize exploring the mechanisms through which different types of glycosylation modifications impact these processes. With a deeper understanding of these biological functions, researchers in related fields can look forward to the development of new therapeutic strategies and biomarkers that will provide more options for the management of a wide range of diseases.153 Certainly, EV glycosylation research demands multidisciplinary collaboration, including biochemistry, cell biology, immunology, and clinical medicine. This collaborative approach aids in comprehending the significance of EV glycosylation across diverse fields and facilitates the translation of these findings into practical applications for cancer diagnosis, therapy, and monitoring.

In conclusion, the field of EV glycosylation is rapidly advancing, with a broad spectrum of applications. Future research endeavors will continue to deepen our comprehension of this field, likely yielding further innovations and breakthroughs in the diagnosis and therapy of diseases.

Acknowledgments

L.W. and C.G. gratefully acknowledge the Innovation Group Project of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission, Grant 2019CXJQ03; the China National Key Projects for Infectious Disease, Grant 2018ZX10302205003; and the National Science Foundation of China, Grant 82372321.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Raposo G.; Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 373–83. 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi Z.; Sun Q.; Tang W. Research advances and challenges in tissue-derived extracellular vesicles. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1036746. 10.3389/fmolb.2022.1036746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Z.; Cao L.; Wu Y.; Wang B.; Song Z.; Yang J.; Cheng L.; Yang X.; Zhou X.; Dai Z.; Li X.; Guan F. Bisecting GlcNAc modification diminishes the pro-metastatic functions of small extracellular vesicles from breast cancer cells. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 10, e12005 10.1002/jev2.12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo S. A.; Luecke L. B.; Kahlert C.; Fernandez A. F.; Gammon S. T.; Kaye J.; LeBleu V. S.; Mittendorf E. A.; Weitz J.; Rahbari N.; Reissfelder C.; Pilarsky C.; Fraga M. F.; Piwnica-Worms D.; Kalluri R. Glypican-1 identifies cancer exosomes and detects early pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015, 523, 177–82. 10.1038/nature14581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R.; LeBleu V. S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. 10.1126/science.aau6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. M.; Abdelmohsen K.; Mustapic M.; Kapogiannis D.; Gorospe M. RNA in extracellular vesicles. WIREs RNA 2017, 8, e1413 10.1002/wrna.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeo A. M.; Ikezu T. Extracellular vesicle biology in alzheimer’s disease and related tauopathy. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2018, 13, 292–308. 10.1007/s11481-017-9768-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurunathan S.; Kang M. H.; Jeyaraj M.; Qasim M.; Kim J. H. Review of the isolation, characterization, biological function, and multifarious therapeutic approaches of exosomes. Cells 2019, 8, 307. 10.3390/cells8040307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal J.; Arras G.; Colombo M.; Jouve M.; Morath J. P.; Primdal-Bengtson B.; Dingli F.; Loew D.; Tkach M.; Thery C. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, E968–E977. 10.1073/pnas.1521230113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Zhang J.; Xu M.; Yang Z.; Yue S.; Zhou W.; Gui C.; Zhang H.; Li S.; Wang P. G.; Yang S. Advances in glycopeptide enrichment methods for the analysis of protein glycosylation over the past decade. J. Sep. Sci. 2022, 45, 3169–3186. 10.1002/jssc.202200292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins A. M.; Ramos C. C.; Freitas D.; Reis C. A. Glycosylation of cancer extracellular vesicles: capture strategies, functional roles and potential clinical applications. Cells 2021, 10, 109. 10.3390/cells10010109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schjoldager K. T.; Narimatsu Y.; Joshi H. J.; Clausen H. Global view of human protein glycosylation pathways and functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 729–749. 10.1038/s41580-020-00294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagdonaite I.; Malaker S. A.; Polasky D. A.; Riley N. M.; Schjoldager K.; Vakhrushev S. Y.; Halim A.; Aoki-Kinoshita K. F.; Nesvizhskii A. I.; Bertozzi C. R.; Wandall H. H.; Parker B. L.; Thaysen-Andersen M.; Scott N. E. Glycoproteomics. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers. 2022, 2, 48. 10.1038/s43586-022-00128-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mereiter S.; Balmana M.; Campos D.; Gomes J.; Reis C. A. Glycosylation in the era of cancer-targeted therapy: where are we heading?. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 6–16. 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Steen P.; Rudd P. M.; Dwek R. A.; Opdenakker G. Concepts and principles of O-linked glycosylation. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1998, 33, 151–208. 10.1080/10409239891204198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda A.; Kuno A.; Yoshida M.; Wagatsuma T.; Sato T.; Miyagishi M.; Zhao J.; Suematsu M.; Kabe Y.; Narimatsu H. Comparative glycomic analysis of exosome subpopulations derived from pancreatic cancer cell lines. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 2516–2524. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu O.-Y.; Li C.-L.; Chen C.-C.; Shen Y.-C.; Moi S.-H.; Luo C.-W.; Xia W.-Y.; Wang Y.-N.; Lee H.-H.; Wang L.-H.; et al. De-glycosylated membrane PD-L1 in tumor tissues as a biomarker for responsiveness to atezolizumab (Tecentriq) in advanced breast cancer patients. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 123–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinho S. S.; Reis C. A. Glycosylation in cancer: mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 540–55. 10.1038/nrc3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reily C.; Stewart T. J.; Renfrow M. B.; Novak J. Glycosylation in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 346–366. 10.1038/s41581-019-0129-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.; Zhou S.; Yuan T. The ″sugar-coated bullets″ of cancer: tumor-derived exosome surface glycosylation from basic knowledge to applications. Clin. Transl. Med. 2020, 10, e204 10.1002/ctm2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escrevente C.; Keller S.; Altevogt P.; Costa J. Interaction and uptake of exosomes by ovarian. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 108. 10.1186/1471-2407-11-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach J. Q.; Kruger A.; Gallogly S.; Hanley S. A.; Hogan M. C.; Ward C. J.; Joshi L.; Griffin M. D. Surface glycosylation profiles of urine extracellular vesicles. PLoS One 2013, 8, e74801 10.1371/journal.pone.0074801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C.; Royo F.; Aizpurua-Olaizola O.; Pazos R.; Boons G. J.; Reichardt N. C.; Falcon-Perez J. M. Glycosylation of extracellular vesicles: current knowledge, tools and clinical perspectives. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1442985. 10.1080/20013078.2018.1442985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrablova V.; Kosutova N.; Blsakova A.; Bertokova A.; Kasak P.; Bertok T.; Tkac J. Glycosylation in extracellular vesicles: isolation, characterization, composition, analysis and clinical applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 67, 108196. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2023.108196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen I. H.; Aguilar H. A.; Paez Paez J. S.; Wu X.; Pan L.; Wendt M. K.; Iliuk A. B.; Zhang Y.; Tao W. A. Analytical pipeline for discovery and verification of glycoproteins from plasma-derived extracellular vesicles as breast cancer biomarkers. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 6307–6313. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b01090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner C.; Di Vizio D.; Sahoo S.; Thery C.; Witwer K. W.; Wauben M.; Hill A. F. Techniques used for the isolation and characterization of extracellular vesicles: results of a worldwide survey. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2016, 5, 32945. 10.3402/jev.v5.32945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pospichalova V.; Svoboda J.; Dave Z.; Kotrbova A.; Kaiser K.; Klemova D.; Ilkovics L.; Hampl A.; Crha I.; Jandakova E.; Minar L.; Weinberger V.; Bryja V. Simplified protocol for flow cytometry analysis of fluorescently labeled exosomes and microvesicles using dedicated flow cytometer. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 25530. 10.3402/jev.v4.25530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvjetkovic A.; Lotvall J.; Lasser C. The influence of rotor type and centrifugation time on the yield and purity of extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 23111. 10.3402/jev.v3.23111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeppesen D. K.; Fenix A. M.; Franklin J. L.; Higginbotham J. N.; Zhang Q.; Zimmerman L. J.; Liebler D. C.; Ping J.; Liu Q.; Evans R.; Fissell W. H.; Patton J. G.; Rome L. H.; Burnette D. T.; Coffey R. J. Reassessment of exosome composition. Cell 2019, 177, 428–445. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D. S. K.; Upton F. M.; Rees E.; Limb C.; Jiao L. R.; Krell J.; Frampton A. E. Size-exclusion chromatography as a technique for the investigation of novel extracellular vesicles in cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 3156. 10.3390/cancers12113156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant R.; Ansa-Addo E.; Stratton D.; Antwi-Baffour S.; Jorfi S.; Kholia S.; Krige L.; Lange S.; Inal J. A filtration-based protocol to isolate human plasma membrane-derived vesicles and exosomes from blood plasma. J. Immunol. Methods 2011, 371, 143–51. 10.1016/j.jim.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoloff J. M.; Saucedo-Espinosa M. A.; Dittrich P. S. Microfluidic platform for profiling of extracellular vesicles from single breast cancer cells. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 1933–9. 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c04106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Freitas D.; Kim H. S.; Fabijanic K.; Li Z.; Chen H.; Mark M. T.; Molina H.; Martin A. B.; Bojmar L.; Fang J.; Rampersaud S.; Hoshino A.; Matei I.; Kenific C. M.; Nakajima M.; Mutvei A. P.; Sansone P.; Buehring W.; Wang H.; Jimenez J. P.; Cohen-Gould L.; Paknejad N.; Brendel M.; Manova-Todorova K.; Magalhães A.; Ferreira J. A.; Osorio H.; Silva A. M.; Massey A.; Cubillos-Ruiz J. R.; Galletti G.; Giannakakou P.; Cuervo A. M.; Blenis J.; Schwartz R.; Brady M. S.; Peinado H.; Bromberg J.; Matsui H.; Reis C. A.; Lyden D. Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 332–343. 10.1038/s41556-018-0040-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohle G.; Gan J.; Li H. Affinity-based isolation of extracellular vesicles and the effects on downstream molecular analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 7051–7067. 10.1007/s00216-022-04178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Nguyen L. T. H.; Hickey R.; Walters N.; Wang X.; Kwak K. J.; Lee L. J.; Palmer A. F.; Reategui E. Immunomagnetic sequential ultrafiltration (iSUF) platform for enrichment and purification of extracellular vesicles from biofluids. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8034. 10.1038/s41598-021-86910-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T.; Wen T.; Ge Y.; Liu J.; Yang L.; Jiang Y.; Dong X.; Liu H.; Yao J.; An G. Disruption of core 1-mediated O-glycosylation oppositely regulates CD44 expression in human colon cancer cells and tumor-derived exosomes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 521, 514–520. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.10.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andaluz Aguilar H.; Iliuk A. B.; Chen I. H.; Tao W. A. Sequential phosphoproteomics and N-glycoproteomics of plasma-derived extracellular vesicles. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 161–180. 10.1038/s41596-019-0260-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeyen E.; Van Mol K.; Baggerman G.; Willems H.; Boonen K.; Rolfo C.; Pauwels P.; Jacobs A.; Schildermans K.; Cho W. C.; Mertens I. Ultrafiltration and size exclusion chromatography combined with asymmetrical-flow field-flow fractionation for the isolation and characterisation of extracellular vesicles from urine. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1490143. 10.1080/20013078.2018.1490143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco C.; Ghirardello A.; Bertazza L.; Gasparotto M.; Zanatta E.; Iaccarino L.; Valadi H.; Doria A.; Gatto M. Size-exclusion chromatography combined with ultrafiltration efficiently Isolates extracellular vesicles from human blood samples in health and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3663. 10.3390/ijms24043663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou D.; Wang Y.; Yang Q.; Hu L.; Zhu Q. Ultrafiltration combing with phospholipid affinity-based isolation for metabolomic profiling of urinary extracellular vesicles. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1640, 461942. 10.1016/j.chroma.2021.461942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro E. M.; Vestad B.; Steffensen L. A.; Aass H. C. D.; Saeed M.; Øvstebø R.; Costea D. E.; Galtung H. K.; Søland T. M. Efficient extracellular vesicle isolation by combining cell media modifications, ultrafiltration, and size-exclusion chromatography. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0204276 10.1371/journal.pone.0204276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mol E. A.; Goumans M. J.; Doevendans P. A.; Sluijter J. P. G.; Vader P. Higher functionality of extracellular vesicles isolated using size-exclusion chromatography compared to ultracentrifugation. Nanomedicine 2017, 13, 2061–2065. 10.1016/j.nano.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares M.; Pinto M. M.; Nobre R. J.; de Almeida L. P.; da Graca Rasteiro M.; Almeida-Santos T.; Ramalho-Santos J.; Sousa A. P. Isolation of extracellular vesicles from human follicular fluid: size-exclusion chromatography versus ultracentrifugation. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 278. 10.3390/biom13020278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Wang J.; Chen W.; Lu H.; Zhang Y. Comprehensive review of MS-based studies on N-glycoproteome and N-glycome of extracellular vesicles. Proteomics 2023, e2300065 10.1002/pmic.202300065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiyawat R.; Weeraphan C.; Netsirisawan P.; Chokchaichamnankit D.; Srisomsap C.; Svasi J.; Champattanachai V. Elevated O-GlcNAcylation of extracellular vesicle proteins derived from metastatic colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2016, 13, 387–398. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao H.; Chung J.; Balaj L.; Charest A.; Bigner D. D.; Carter B. S.; Hochberg F. H.; Breakefield X. O.; Weissleder R.; Lee H. Protein typing of circulating microvesicles allows real-time monitoring of glioblastoma therapy. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1835–40. 10.1038/nm.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova V.; Ludwig A. K.; Hornung S.; Rotan O.; Horn P. A.; Epple M.; Giebel B. Characterisation of exosomes derived from human cells by nanoparticle tracking analysis and scanning electron microscopy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2011, 87, 146–50. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragovic R. A.; Gardiner C.; Brooks A. S.; Tannetta D. S.; Ferguson D. J.; Hole P.; Carr B.; Redman C. W.; Harris A. L.; Dobson P. J.; Harrison P.; Sargent I. L. Sizing and phenotyping of cellular vesicles using nanoparticle tracking analysis. Nanomedicine 2011, 7, 780–8. 10.1016/j.nano.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akers J. C.; Ramakrishnan V.; Nolan J. P.; Duggan E.; Fu C. C.; Hochberg F. H.; Chen C. C.; Carter B. S. Comparative analysis of technologies for quantifying extracellular vesicles (EVs) in clinical cerebrospinal fluids (CSF). PLoS One 2016, 11, e0149866 10.1371/journal.pone.0149866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coumans F. A.; van der Pol E.; Boing A. N.; Hajji N.; Sturk G.; van Leeuwen T. G.; Nieuwland R. Reproducible extracellular vesicle size and concentration determination with tunable resistive pulse sensing. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 25922. 10.3402/jev.v3.25922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Nakane N.; Maurer-Spurej E. Novel test for microparticles in platelet-rich plasma and platelet concentrates using dynamic light scattering. Transfusion 2011, 51, 363–70. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitar S.; Kejzar A.; Pahovnik D.; Kogej K.; Tusek-Znidaric M.; Lenassi M.; Zagar E. Size characterization and quantification of exosomes by asymmetrical-flow field-flow fractionation. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 9225–33. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b01636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco A. F.; Lewis D. E. Flow cytometric analysis of circulating microparticles in plasma. Cytometry A 2010, 77A, 502–14. 10.1002/cyto.a.20886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler W. L.; Yeung W.; Tait J. F. A new microparticle size calibration standard for use in measuring smaller microparticles using a new flow cytometer. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011, 9, 1216–24. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach J. Q.; Maguire C. M.; Krüger A.; Joshi L.; PrinaMello A.; Griffin M. D. Urinary nanovesicles captured by lectins or antibodies demonstrate variations in size and surface glycosylation profile. Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 1217–1229. 10.2217/nnm-2017-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Manilla G.; Atwood J. III; Guo Y.; Warren N. L.; Orlando R.; Pierce M. Tools for glycoproteomic analysis: size exclusion chromatography facilitates identification of tryptic glycopeptides with N-linked glycosylation sites. J. Proteome Res. 2006, 5, 701–708. 10.1021/pr050275j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. W.; Bilbao A.; Wang J.; Liao Y. C.; Velickovic D.; Wojcik R.; Passamonti M.; Zhao R.; Gargano A. F. G.; Gerbasi V. R.; Pas̆a-Tolić L.; Baker S. E.; Zhou M. Online hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) enhanced top-down mass spectrometry characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 5909–5917. 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c00139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Chen Y.; Liu Z. Boronate affinity materials for separation and molecular recognition: structure, properties and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 8097–123. 10.1039/C5CS00013K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She Y. M.; Tam R. Y.; Li X.; Rosu-Myles M.; Sauve S. Resolving isomeric structures of native glycans by nanoflow porous graphitized carbon chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 14038–14046. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Li X. J.; Martin D. B.; Aebersold R. Identification and quantification of N-linked glycoproteins using hydrazide chemistry, stable isotope labeling and mass spectrometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 660–666. 10.1038/nbt827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M.; Shu H.; Yang M.; Yan G.; Zhang L.; Wang L.; Wang W.; Lu H. Fast discrimination of sialylated N-glycan linkage isomers with one-step derivatization by microfluidic capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 4666–4676. 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c04760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y.; Sheng Y.; Li Q.; Ju S.; Reyes J.; Lebrilla C. B. Determination of the glycoprotein specificity of lectins on cell membranes through oxidative proteomics. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 9501–9512. 10.1039/D0SC04199H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongay S.; Boichenko A.; Govorukhina N.; Bischoff R. Glycopeptide enrichment and separation for protein glycosylation analysis. J. Sep. Sci. 2012, 35, 2341–72. 10.1002/jssc.201200434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M.; Yamada K. Recent advances and trends in sample preparation and chemical modification for glycan analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 207, 114424. 10.1016/j.jpba.2021.114424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. Y.; Qin H. Q.; Ye M. L. Recent advances in glycopeptide enrichment and mass spectrometry data interpretation approaches for glycoproteomics analyses. Chin. J. Chromatogr. 2021, 39, 1045–1054. 10.3724/SP.J.1123.2021.06011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escrevente C.; Grammel N.; Kandzia S.; Zeiser J.; Tranfield E. M.; Conradt H. S.; Costa J. Sialoglycoproteins and N-glycans from secreted exosomes of ovarian carcinoma cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e78631 10.1371/journal.pone.0078631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendiuk Goncalves J.; Walker S. A.; Aguilar Diaz de Leon J. S.; Yang Y.; Davidovich I.; Busatto S.; Sarkaria J.; Talmon Y.; Borges C. R.; Wolfram J. Glycan node analysis detects varying glycosaminoglycan levels in melanoma-derived extracellular vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8506. 10.3390/ijms24108506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y.; Duan B.; Sha J.; Zhang R.; Fan J.; Xu X.; Zhao H.; Niu X.; Geng Z.; Gu J.; Huang B.; Ren S. Serum IgG N-glycans enable early detection and early relapse prediction of colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 152, 536–547. 10.1002/ijc.34298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K.; Waki H.; Ido Y.; Akita S.; Yoshida Y.; Yoshida T.; Matsuo T. Protein and polymer analyses up tom/z 100 000 by laser ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1988, 2, 151–153. 10.1002/rcm.1290020802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn J. B.; Mann M.; Meng C. K.; Wong S. F.; Whitehouse C. M. Electrospray ionization for mass spectrometry of large biomolecules. Science. 1989, 246, 64–71. 10.1126/science.2675315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler W. M.; Waidelich D.; Kerner A.; Hanke S.; Berg R.; Trumpp A.; Rosli C. MALDI versus ESI: the impact of the ion source on peptide identification. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 1207–1215. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapels M. D.; Barofsky D. F. Complementary use of MALDI and ESI for the HPLC-MS/MS analysis of DNA-binding proteins. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 5423–5430. 10.1021/ac030427z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke C. R. K.; Hartig J. P.; Grimsley G.; Liu L.; Semmes O. J.; Wu J. D.; Ippolito J. E.; Hughes-Halbert C.; Nyalwidhe J. O.; Drake R. R. Direct N-glycosylation profiling of urine and prostatic fluid glycoproteins and extracellular vesicles. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 734280. 10.3389/fchem.2021.734280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sviben D.; Forcic D.; Halassy B.; Allmaier G.; Marchetti-Deschmann M.; Brgles M. Mass spectrometry-based investigation of measles and mumps virus proteome. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 160. 10.1186/s12985-018-1073-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi L.; Carnemolla C.; Viviani V.; Landi C.; Pavone V.; Luddi A.; Piomboni P.; Bini L. Soluble protein fraction of human seminal plasma. J. Proteomics. 2018, 174, 85–100. 10.1016/j.jprot.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shajahan A.; Heiss C.; Ishihara M.; Azadi P. Glycomic and glycoproteomic analysis of glycoproteins-a tutorial. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 4483–4505. 10.1007/s00216-017-0406-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S.; Wooding K. M.; Mechref Y. Analysis of permethylated glycan by liquid chromatography (LC) and mass spectrometry (MS). Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1503, 83–96. 10.1007/978-1-4939-6493-2_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou G. Z.; Benktander G. D.; Gizaw S. T.; Gaunitz S.; Novotny M. V. Comprehensive analytical approach toward glycomic characterization and profiling in urinary exosomes. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 5364–5372. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W.; Zhou X.; Benktander J. D.; Gaunitz S.; Zou G.; Wang Z.; Novotny M. V.; Jacobson S. C. In-depth compositional and structural characterization of N-glycans derived from human urinary exosomes. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 13528–13537. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H.; Ju S.; Kang K.; Seo M. H.; Kim J. M.; Miyoshi E.; Yeo M. K.; Park S. Y. Terminal fucosylation of haptoglobin in cancer-derived exosomes during cholangiocarcinoma progression. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1183442. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1183442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne C.; Brooks A. S. SDS-PAGE and western blotting to detect proteins and glycoproteins of interest in breast cancer research. Methods Mol. Med. 2005, 120, 217–229. 10.1385/1-59259-969-9:217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y.; Chen J.; Zheng Z.; Tao Y.; Zhang S.; Zou M.; Yang Y.; Xue M.; Hu F.; Li Y.; Zhang Q.; Xue Y.; Zheng Z. Tubular epithelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles induce macrophage glycolysis by stabilizing HIF-1alpha in diabetic kidney disease. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 95. 10.1186/s10020-022-00525-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K.; Ishikawa N.; Tatsuguchi A.; Saichi N.; Fujii R.; Nakagawa H. Antibody-coupled monolithic silica microtips for highthroughput molecular profiling of circulating exosomes. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6232. 10.1038/srep06232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska K.; Wachalska M.; Graul M.; Rychlowski M.; Bienkowska-Szewczyk K.; Lipinska A. D. Alphaherpesvirus gB homologs are targeted to extracellular vesicles, but they differentially affect MHC class II molecules. Viruses 2020, 12, 429. 10.3390/v12040429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo M. C.; Matsuo A. L.; Ganiko L.; Medeiros L. C.; Miranda K.; Silva L. S.; Freymuller-Haapalainen E.; Sinigaglia-Coimbra R.; Almeida I. C.; Puccia R. The pathogenic fungus paracoccidioides brasiliensis exports extracellular vesicles containing highly immunogenic alpha-Galactosyl epitopes. Eukaryot Cell 2011, 10, 343–51. 10.1128/EC.00227-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria J.; Royo F.; Pazos R.; Salazar L.; Falcon-Perez J. M.; Reichardt N. C. Microarray-based identification of lectins for the purification of human urinary extracellular vesicles directly from urine samples. ChemBioChem. 2014, 15, 1621–6. 10.1002/cbic.201402058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosanovic M.; Jankovic M. Isolation of urinary extracellular vesicles from Tamm- Horsfall protein-depleted urine and their application in the development of a lectin-exosome-binding assay. Biotechniques 2014, 57, 143–9. 10.2144/000114208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobb R. J.; Becker M.; Wen S. W.; Wong C. S.; Wiegmans A. P.; Leimgruber A.; Móller A. Optimized exosome isolation protocol for cell culture supernatant and human plasma. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27031. 10.3402/jev.v4.27031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell S. R.; Ju T.; Cummings R. D. Protein glycosylation in cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2015, 10, 473–510. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012414-040438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitka D.; Mihaly J.; Fraikin J. L.; Beke-Somfai T.; Varga Z. Detection and phenotyping of extracellular vesicles by size exclusion chromatography coupled with on-line fluorescence detection. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19868. 10.1038/s41598-019-56375-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaysen-Andersen M.; Packer N. H.; Schulz B. L. Maturing glycoproteomics technologies provide unique structural insights into the N-glycoproteome and its regulation in health and disease. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2016, 15, 1773–90. 10.1074/mcp.O115.057638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. M.In-depth compositional and structural identification of N-glycans and evaluation of their potential for disease diagnostics. Doctoral Thesis, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Islam M. K.; Syed P.; Lehtinen L.; Leivo J.; Gidwani K.; Wittfooth S.; Pettersson K.; Lamminmaki U. A nanoparticle-based approach for the detection of extracellular vesicles. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10038. 10.1038/s41598-019-46395-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savicheva E. A.; Mitronova G. Y.; Thomas L.; Bohm M. J.; Seikowski J.; Belov V. N.; Hell S. W. Negatively charged yellow-emitting 1-aminopyrene dyes for reductive amination and fluorescence detection of glycans. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 5505–5509. 10.1002/anie.201908063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keerthikumar S.; Chisanga D.; Ariyaratne D.; Al Saffar H.; Anand S.; Zhao K.; Samuel M.; Pathan M.; Jois M.; Chilamkurti N.; Gangoda L.; Mathivanan S. ExoCarta: a web-based compendium of exosomal cargo. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 688–692. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D. S.; Kim D. K.; Kim Y. K.; Gho Y. S. Proteomics of extracellular vesicles: Exosomes and ectosomes. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2015, 34, 474–90. 10.1002/mas.21420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Tao J.; Li Y.; Feng Y.; Ju H.; Wang Z.; Ding L. Quantitative localized analysis reveals distinct exosomal protein-specific glycosignatures: implications in cancer cell subtyping, exosome biogenesis, and function. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 7404–7412. 10.1021/jacs.9b12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker A.; Thakur B. K.; Weiss J. M.; Kim H. S.; Peinado H.; Lyden D. Extracellular vesicles in cancer: cell-to-cell mediators of metastasis. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 836–848. 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes P.; Sese M.; Guijarro P. J.; Emperador M.; Sanchez-Redondo S.; Peinado H.; Hummer S.; Ramon y Cajal S. ITGB3-mediated uptake of small extracellular vesicles facilitates intercellular communication in breast cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4261. 10.1038/s41467-020-18081-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C.; Pazos R.; Royo F.; Gonzalez E.; Roura-Ferrer M.; Martinez A.; Gamiz J.; Reichardt N. C.; Falcon-Perez J. M. Assessing the role of surface glycans of extracellular vesicles on cellular uptake. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11920. 10.1038/s41598-019-48499-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson H. C.; Svensson K. J.; van Kuppevelt T. H.; Li J. P.; Belting M. Cancer cell exosomes depend on cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans for their internalization and functional activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 17380–5. 10.1073/pnas.1304266110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S.; Bai O.; Li F.; Yuan J.; Laferte S.; Xiang J. Mature dendritic cells pulsed with exosomes stimulate efficient cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses and antitumour immunity. Immunology 2007, 120, 90–102. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barres C.; Blanc L.; Bette-Bobillo P.; Andre S.; Mamoun R.; Gabius H. J.; Vidal M. Galectin-5 is bound onto the surface of rat reticulocyte exosomes and modulates vesicle uptake by macrophages. Blood 2010, 115, 696–705. 10.1182/blood-2009-07-231449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piombino C.; Mastrolia I.; Omarini C.; Candini O.; Dominici M.; Piacentini F.; Toss A. The role of exosomes in breast cancer diagnosis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 312. 10.3390/biomedicines9030312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y.; Qiu Y.; Jiang W.; Fu B. M. Glycocalyx acts as a central player in the development of tumor microenvironment by extracellular vesicles for angiogenesis and metastasis. Cancers 2022, 14, 5415. 10.3390/cancers14215415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hait N. C.; Maiti A.; Wu R.; Andersen V. L.; Hsu C. C.; Wu Y.; Chapla D. G.; Takabe K.; Rusiniak M. E.; Bshara W.; Zhang J.; Moremen K. W.; Lau J. T. Y. Extracellular sialyltransferase st6gal1 in breast tumor cell growth and invasiveness. Cancer Gene. Ther. 2022, 29, 1662–1675. 10.1038/s41417-022-00485-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Wang R.; Li D.; Zuo C.; Wen P.; Liu H.; Chen Y.; Fujita M.; Wu Z.; Yang G. Comprehensive analysis of the glycome and glycoproteome of bovine milk-derived exosomes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 12692–12701. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c04605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu K.; McKay P. F.; Samnuan K.; Najer A.; Blakney A. K.; Che J.; O’Driscoll G.; Cihova M.; Stevens M. M.; Shattock R. J. Presentation of antigen on extracellular vesicles using transmembrane domains from viral glycoproteins for enhanced immunogenicity. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12199 10.1002/jev2.12199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]