Abstract

The Rieske 2Fe2S cluster of Chlorobium limicola forma thiosulfatophilum strain tassajara was studied by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Two distinct orientations of its g tensor were observed in oriented samples corresponding to differing conformations of the protein. Only one of the two conformations persisted after treatment with 2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl-p-benzoquinone. A redox midpoint potential (Em) of +160 mV in the pH range of 6 to 7.7 and a decreasing Em (−60 to −80 mV/pH unit) above pH 7.7 were found. The implications of the existence of differing conformational states of the Rieske protein, as well as of the shape of its Em-versus-pH curve, in green sulfur bacteria are discussed.

The cytochrome bc complex, the only energy-conserving enzyme of both photosynthetic and respiratory electron transport systems, has been studied in depth in mitochondria and purple bacteria (10) (bc1 complex), as well as in chloroplasts and cyanobacteria (12) (b6f complex).

Species possessing a cytochrome bc-type enzyme are spread over the entire phylogenetic tree (24) of the bacteria (the complex has been found in green sulfur [14, 33] and green filamentous [35] bacteria, in deinococci [9], and in firmicutes [15, 17–19, 29]), and some of its constituent proteins are even present in archaea (2; for a discussion of the evolutionary implications, see reference 6). The tacit assumption, however, that the bc complexes found in the latter organisms would resemble either the cytochrome bc1- or the cytochrome b6f-type enzymes has been invalidated in recent years by detailed studies of the complex in firmicutes (15, 34). The finding that in the archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, the cytochrome bc complex does not exist as a separate entity but that components thereof apparently are part of a quinol oxidase supercomplex (2) further illustrated the diversity of cytochrome bc-type enzymes and suggested the existence of “peculiar” representatives of this class of enzymes in the hitherto only scantly studied branches of the phylogenetic subtree of the bacteria.

The complex in green sulfur bacteria has been studied in some detail. Again, functional studies detected the typical characteristics known for cytochrome bc complexes from mitochondria and chloroplasts (13). The green sulfur bacterial enzyme, however, appeared to differ from other examined systems with respect to the possible absence of a subunit corresponding to cytochrome c1 or f (33). The recently published X-ray structure of the mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex strongly indicated that long-range conformational movement of the Rieske protein, i.e., a shuttling between cytochrome b and cytochrome c1, is a crucial part of enzyme turnover (7, 36). The possible lack in chlorobiaceae of a c-heme subunit therefore raises the question of the possibility of such a conformational change in the green sulfur bacterial enzyme. Results concerning the electrochemical parameters of the Chlorobium Rieske cluster suggested a pK value of 5 (14, 27). This pK value differs significantly from those found in most of the other systems studied (16, 19, 23, 27, 29), for which pK values of about 8 have been determined. To date, only one further exception to the “pK of 8” class of Rieske centers has been reported, i.e., the cluster found in the archaeon S. acidocaldarius with a pK value of close to pH 6 (3).

In the present work, we have studied the mentioned set of “deviant” characteristics of the green sulfur bacterial cytochrome bc complex in more detail. The results obtained allow a better assessment of the similarities and differences between the Chlorobium enzyme and that of the other species studied so far and thus help to clarify the positioning of the green sulfur bacterial cytochrome bc complex in the evolutionary pathway of this class of enzymes.

The following abbreviations are used in this report: DBMIB, 2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl-p-benzoquinone; Em, redox midpoint potential; MES, 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid; MOPS, morpholinepropanesulfonic acid; MK, menaquinone; PQ, plastoquinone; UQ, ubiquinone.

Chlorobium limicola forma thiosulfatophilum strain tassajara (kindly provided by N. Pfennig, Constance, Federal Republic of Germany) was grown, and membrane fragments were isolated as described previously (1). For oriented membrane multilayers, membrane fragments from C. limicola were separated from chlorosomes by the method of Schmidt (31). Redox titrations were performed at 15°C as described by Dutton (8), in the presence of 30 mM MES, MOPS, Tricine, 3-[(1,1-dimethyl-2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-hydroxypropanesulfonic acid, and glycine. Oriented membrane multilayers were obtained as described by Rutherford and Sétif (30). A DBMIB-treated sample was obtained by applying a solution of DBMIB to an already dried sample and then drying it again under a stream of argon gas in darkness. All of the chemicals used were reagent grade. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker ESP 300E X-band spectrometer fitted with an Oxford Instruments cryostat and temperature control system.

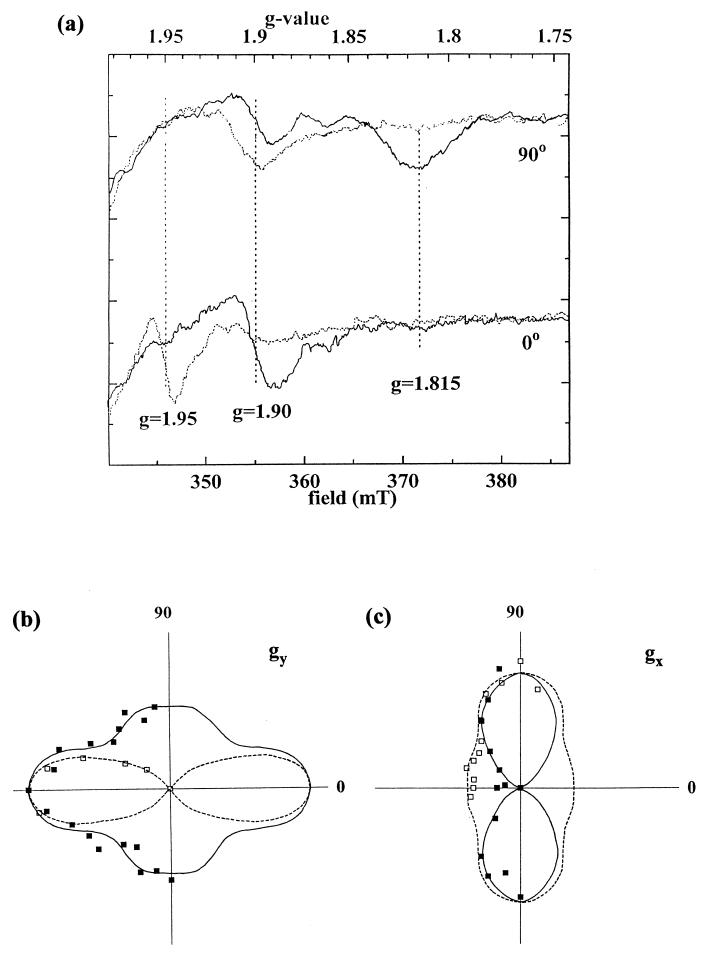

Partial orientation of membrane samples was achieved by drying liquid suspensions of membrane fragments onto sheets of mylar (30). The resulting oriented membrane multilayers allowed determination of the orientations of the principal g-tensor axes of the C. limicola Rieske center with respect to the membrane plane. Figure 1a shows spectra taken at orientations of 0° and 90° (angle between the magnetic field and the membrane plane) in the absence of inhibitor (continuous line). The spectra were characterized by a derivative-shaped gy signal at g = 1.9 and a gx trough at g = 1.815. The gz signal (not shown) was largely obscured by a wide radical signal.

FIG. 1.

(a) EPR spectra of partially ordered membrane multilayers from C. limicola recorded at 0° and at 90° (angle between magnetic field and membrane plane), before (continuous line) and after (dashed line) treatment with DBMIB. Instrument settings: microwave frequency, 9.44 GHz; modulation amplitude, 1.6 mT; temperature, 15 K; microwave power, 6.3 mW. (b and c) Polar plots of signal amplitudes of the gy (b) and gx (c) lines in untreated (solid squares, continuous line) and DBMIB-treated (open squares, dashed line), oriented membrane multilayers from C. limicola.

The dependence of signal amplitude on angle in the absence of inhibitor is shown in the polar plots of Fig. 1b and c (continuous line) for gy (1.90) and gx (1.815), respectively. According to these data, a large fraction of Rieske centers point their gy and gx orientations parallel and perpendicular, respectively, to the membrane, i.e., similar to what has been reported for cytochrome bc1 complexes (26) or for the cytochrome bc complex in the gram positive-bacterium PS3 (19). In contrast to these latter systems, however, a broad additional maximum in the polar plot of gy was observed at high angles with respect to the membrane (>50°). No obvious second maximum could be discerned at the gx signal (g = 1.815). To determine whether the peculiar side maximum on gy was due to sample preparation or reflected actual heterogeneity of g-tensor orientation, the sample of dehydrated membranes was subsequently treated with the quinone analog DBMIB. The DBMIB-induced alterations of the spectrum (Fig. 1a, dotted curves) of the C. limicola Rieske center corresponded to what has been reported for many other cytochrome bc complexes (reviewed in reference 12); i.e., the uninhibited 1.9 gy signal was displaced to 1.95 and the gx trough was shifted from 1.815 to 1.9. A slight trough at g = 1.815 persisted in the DBMIB-treated sample, indicating that a fraction of centers had not bound the inhibitor. This was most probably due to incomplete penetration of the DBMIB solution down to the lowest layers of membranes on the mylar sheet (22). In the presence of the inhibitor, the side maximum at 90° visible for gy of the uninhibited state (i.e., at g = 1.9) completely disappeared, leaving gy (at g = 1.95) highly oriented parallel to the membrane plane (Fig. 1b, dotted curve).

The orientation of the g = 1.9 signal, which consisted predominantly of the gx trough arising from DBMIB-inhibited centers and to a much lesser extent of the gy line of uninhibited centers, was found to be mainly perpendicular to the membrane plane with a small side maximum at 0° (Fig. 1c). The side maximum at 0° most probably arose from the contribution of the gy line of centers devoid of inhibitor. The orientations of the gx and gz signals arising from the “second” species in the uninhibited state could not be determined, since the spectral region of the gz peak was dominated by a large radical signal and the gx trough was apparently too broad to be picked up (see below).

The observation of two distinct orientations of the Rieske cluster’s g tensor suggests the existence of two significantly different conformations of the Chlorobium Rieske protein with respect to the membrane. The conformation giving rise to gy at high angles with respect to the membrane is converted to the “normal” conformation by binding of DBMIB. It is noteworthy that such differing and interconvertible conformational states of the Rieske protein are strongly reminiscent of the two positions of the Rieske protein that have recently been elucidated by X-ray crystallography for the cytochrome bc1 complex from mitochondria (7). The second orientation of gy found in the uninhibited complex from C. limicola, furthermore, strongly resembles the second conformation of Rieske centers that we have recently succeeded in observing by EPR on the oriented purified cytochrome bc1 complex from purple bacteria after specific sample treatments (5). The second conformation in the purple bacterial complex gave rise to gx troughs significantly wider and hence more difficult to observe than the gx trough of the normal conformation, providing a rationalization of why the second gx could not be observed in the membrane sample from C. limicola.

The second orientation of the Rieske g tensor is not observed in the cytochrome bc1 complex from purple bacteria or in the cytochrome bc complex from Bacillus strain PS3 unless specific sample treatments are performed (5). This suggests significant differences in the equilibrium distributions of the two conformational states of the reduced Rieske protein between the former two systems on the one hand and the green sulfur bacterial complex on the other. However, two distinct orientations of the Rieske g tensor differing in relaxation properties have already been observed by EPR on the cytochrome b6f complex from spinach chloroplasts (29, 32). Structural heterogeneity and purely physical explanations were proposed (29) to account for the experimental observations. However, since the X-ray crystallographic structure of the mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex (7, 36) indicates that the Rieske protein can move between a position close to cytochrome c1 and another one close to cytochrome b, it appears much more likely that the two orientations observed in spinach chloroplasts actually arise from structural heterogeneity.

The cytochrome b6f complex contains a c-type cytochrome (cytochrome f) analogous to cytochrome c1 in the mitochrondrial-purple bacterial complex. The fact that the second conformation is observable in the green sulfur bacterial enzyme, as well as in the cytochrome b6f complex, therefore indicates that the detailed equilibrium distribution is modulated by molecular details rather than by the absence or presence of a cytochrome c subunit. Moreover, the occurrence of a domain movement of the Rieske cluster in Chlorobium raises the question of whether a hitherto undetected cytochrome (not present in the reported operon) plays the role of cytochrome c1 or f in C. limicola or whether this movement of the Rieske protein shuttles the electron to a different redox protein.

The domain movement of the Rieske protein thus appears to be an essential feature of enzyme turnover in cytochrome bc-type complexes of bacteria. An in-depth examination of the orientation properties of the Rieske protein in the archaeon S. acidocaldarius will allow judgement of whether such a domain movement is indispensable for the functioning of this type of enzyme in general or whether it represents an evolutionary peculiarity restricted to the domain of the bacteria.

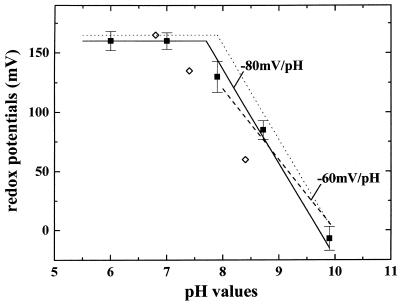

The dependence of Em on the pH value of the Chlorobium Rieske cluster is depicted in Fig. 2 (filled squares). The redox potential was found to be independent of pH up to about pH 7.7 at an Em value of +160 mV. At higher pH values, a decrease with a slope of −60 to −80 mV/pH unit was observed. The dotted curve represents, for comparison, the Em-versus-pH dependence obtained previously for the Rieske cluster in the firmicutis Bacillus strain PS3 (19). The data points reported previously (14) for the Chlorobium Rieske center are shown as open diamonds. Our results are in conflict with these data, which were previously interpreted to suggest a pK value of 5 (14, 27).

FIG. 2.

Determination of the Em of the C. limicola Rieske center and its pH dependence. Em values were determined on the gy signal. EPR conditions were as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The following redox mediators were used, all at 100 μM: 1,4-benzoquinone (+200 mV), 2,6-dichlorophenol indophenol (+217 mV), 2,5-dimethyl-p-benzoquinone (+180 mV), 1,2-naphthoquinone (+145 mV), phenazine methosulfate (+80 mV), 1,4-naphthoquinone (+60 mV), duroquinone (+5 mV), 2,5-dihydroxy-p-benzoquinone (−60 mV), and 2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (−145 mV). Reductive titrations were carried out with sodium dithionite, and oxidative titrations were done with potassium ferricyanide. No hysteresis was observed. All of the titration data obtained could be fitted with simple n = 1 Nernst curves. The dotted line represents the Em-versus-pH curve of the firmicutis Bacillus strain PS3 (19) for comparison. The data points marked as open diamonds show the values obtained by Knaff and Malkin (14).

It is noteworthy that the pH-dependent region of the Em-versus-pH curve in other cytochrome bc complexes is described by two distinct pK values (19–21), resulting in a slope increasing from −60 mV/pH unit to −120 mV/pH unit above pH 10. The two dissociable protons involved in the pH-dependent redox transition have been tentatively identified (16) as the two Nɛ protons of the histidine ligands (11) to the 2Fe2S cluster. A slope steeper than −60 mV/pH unit for the C. limicola Rieske cluster, as suggested by the data points, would indicate the presence of two distinct pK values also in the green sulfur bacterial system. A determination of the second (higher) pK value in C. limicola, however, is beyond the scope of this work. The redox midpoint potential of the Rieske center in C. limicola in the pH-independent region below the pK was determined as +160 mV. This value is approximately 150 mV lower than those observed in “classic” cytochrome bc complexes (ubiquinol [UQH2]- or plastoquinol [PQH2]-oxidizing cytochrome bc1 or cytochrome b6f complexes, respectively) but strongly resembles those observed in the menaquinol (MKH2)-oxidizing complexes from Bacillus strain PS3 (19) (Fig. 2), Thermus thermophilus (16), and Heliobacterium chlorum (18). Three different quinones were found in C. limicola, i.e., MK-7, OH-MK-7, and the so-called chlorobiumquinone (25, 28). The redox potential of chlorobiumquinone was determined to be +40 mV (28), i.e., significantly higher than those of the other two MK species (Em, ∼−70mV). The similarity of the Chlorobium Em-versus-pH curve to those of species using MK as pool quinone therefore strongly indicates that one of the two MKs, rather than chlorobiumquinone, serves as pool quinone for Chlorobium.

A pK value in the vicinity of 8 therefore appears to be common to both UQH2- or PQH2-oxidizing and MKH2-oxidizing cytochrome bc complexes. The Rieske center of the archaeon S. acidocaldarius, with a pK value close to 6.2 (3), represents the only exception to this general rule. The acidophilicity of S. acidocaldarius, its exceptional type of quinone (2), or its localization within the domain of the archaea could explain this deviant pK value. The study of cytochrome bc complexes in acidophilic bacteria will help to elucidate this problem.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Seguin (Saclay, France) for technical assistance concerning bacterial cultures. Thanks are furthermore due to A. R. Crofts (Urbana, Ill.), E. A. Berry (Berkeley, Calif.), C. L. Schmidt (Lübeck, Federal Republic of Germany), and D. Lemesle-Meunier (Marseille, France) for stimulating discussions and communicating data prior to publication. We furthermore thank the group of P. Bertrand for extensive access to the EPR facilities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albouy D, Sturgis J N, Feiler U, Nitschke W, Robert B. Membrane-associated c-type cytochromes from the green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium limicola forma thiosulfatophilum: purification and characterization of cytochrome c553. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1927–1932. doi: 10.1021/bi962624g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anemüller S, Schäfer G. Cytochrome aa3 from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, a single-subunit, quinol-oxidizing archaebacterial terminal oxidase. Eur J Biochem. 1990;191:297–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anemüller S, Schmidt C L, Schäfer G, Bill E, Trautwein A X, Teixeira M. Evidence for a two proton dependent redox equilibrium in an archaeal Rieske iron-sulfur cluster. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;202:252–257. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brugna, M., and W. Nitschke. Unpublished data.

- 5.Brugna, M., S. Rodgers, A. Schricker, G. Montoya, M. Kazmeier, I. Sinning, and W. Nitschke. Unpublished data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Castresana J, Lübben M, Saraste M. New archaebacterial genes coding for redox proteins: implications for the evolution of aerobic metabolism. J Mol Biol. 1995;250:202–210. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crofts, A. R., B. Barquera, R. B. Gennis, R. Kuras, M. Guergova-Kuras, and E. A. Berry. Mechanistic aspects of the Qo-site of the bc1-complex as revealed by mutagenesis studies and the crystallographic structure. In W. Loeffelhardt and G. Schmetterer (ed.), The phototrophic prokaryotes, in press. Plenum Publishing Corporation, New York, N.Y.

- 8.Dutton P L. Oxidation-reduction potential dependence of the interaction of cytochromes, bacteriochlorophyll and carotenoids at 77K, in chromatophores of Chromatium D and Rhodopseudomonas gelatinosa. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;226:63–80. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(71)90178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fee J A, Findling K L, Yoshida T, Hille R, Tarr G E, Hearshen D O, Dunham W R, Day E D, Kent T A, Münck E. Purification and characterisation of the Rieske iron-sulfur protein from Thermus thermophilus. Evidence for a [2Fe-2S] cluster having non-cysteine ligands. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray K A, Daldal F. Mutational studies of the cytochrome bc1 complexes. In: Blankenship R E, Madigan M T, Bauer C E, editors. Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 747–774. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwata S, Saynovits M, Link T A, Michel H. Structure of a water soluble fragment of the “Rieske” iron-sulfur protein of the bovine heart mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex determined by MAD phasing at 1.5 Å resolution. Structure. 1996;4:567–579. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kallas T. The cytochrome b6f complex. In: Bryant D A, editor. The molecular biology of cyanobacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 259–317. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klughammer C, Hager C, Padan E, Schütz M, Schreiber U, Shahak Y, Hauska G. Reduction of cytochromes with menaquinol and sulfide in membranes from green sulfur bacteria. Photosynth Res. 1995;43:27–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00029459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knaff D B, Malkin R. Iron-sulfur proteins of the green photosynthetic bacterium Chlorobium. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;430:244–252. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(76)90082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kramer D M, Schoepp B, Liebl U, Nitschke W. Cyclic electron transfer in Heliobacillus mobilis involving a menaquinol-oxidizing cytochrome bc complex and an RCI-type reaction center. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4203–4211. doi: 10.1021/bi962241i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuila D, Fee J A. Evidence for a redox-linked ionizable group associated with the [2Fe-2S] cluster of Thermus Rieske protein. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:2768–2771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kutoh E, Sone N. Quinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase from the thermophilic bacterium PS3. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:9020–9026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liebl U, Rutherford A W, Nitschke W. Evidence for a unique Rieske iron-sulphur centre in Heliobacterium chlorum. FEBS Lett. 1990;261:427–430. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liebl U, Pezennec S, Riedel A, Kellner E, Nitschke W. The Rieske FeS center from the Gram-positive bacterium PS3 and its interaction with the menaquinone pool studied by EPR. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14068–14072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Link T A, Hagen W R, Pierik A J, Assmann C, von Jagow G. Determination of the redox properties of the Rieske [2Fe-2S] cluster of bovine heart bc1 complex by direct electrochemistry of water-soluble fragment. Eur J Biochem. 1992;208:685–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Link T A. Two pK values of the oxidised ‘Rieske’ [2Fe-2S] cluster observed by CD spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1185:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nitschke, W., and A. W. Rutherford. Unpublished data.

- 23.Nitschke W, Joliot P, Liebl U, Rutherford A W, Hauska G, Müller A, Riedel A. The pH dependence of the redox midpoint potential of the 2Fe2S cluster from cytochrome b6f complex (the ‘Rieske centre’) Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1102:266–268. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olsen G J, Woese C R, Overbeek R. The winds of (evolutionary) change: breathing new life into microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1–6. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.1-6.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powls R, Redfearn R E. Quinones of the Chlorobiaceae. Properties and possible functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;172:429–437. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(69)90139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prince R C. The location, orientation and stoichiometry of the Rieske iron-sulfur cluster in membranes from Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;723:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prince R C, Dutton P L. Further studies on the Rieske iron-sulfur center in mitochondrial and photosynthetic systems: a pK on the oxidized form. FEBS Lett. 1976;65:117–119. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redfearn R E, Powls R. The quinones of green photosynthetic bacteria. Biochem J. 1968;106:50P. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riedel A, Kellner E, Grodzitzki D, Liebl U, Hauska G, Müller A, Rutherford A W, Nitschke W. The [2Fe-2S] centre of the cytochrome bc complex in Bacillus firmus OF4 in EPR: an example of a menaquinol-oxidizing Rieske centre. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1183:263–268. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutherford A W, Sétif P. Orientation of P700, the primary electron donor of photosystem I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1019:128–132. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt K. A comparative study on the composition of chlorosomes (Chlorobium vesicles) and cytoplasmic membranes from Chloroflexus aurantiacus strain Ok-70-fl and Chlorobium limicola f thiosulfatophilum strain 6230. Arch Microbiol. 1980;124:21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schricker, A., and W. Nitschke. Unpublished data.

- 33.Schütz M, Zirngibl S, le Coutre J, Büttner M, Xie D, Nelson N, Deutzmann R, Hauska G. A transcription unit for the Rieske FeS-protein and cytochrome b in Chlorobium limicola. Photosynth Res. 1994;39:163–174. doi: 10.1007/BF00029383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sone N, Tsuchiya N, Inoue M, Noyuchi S. Bacillus stearothermophilus qcr operon encoding Rieske FeS protein, cytochrome b6 and a novel-type cytochrome c1 of quinol-cytochrome c reductase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12457–12462. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zannoni D, Ingledew W J. A thermodynamic analysis of the plasma membrane electron transport components in photoheterotrophically grown cells of Chloroflexus aurantiacus. An optical and electron paramagnetic resonance study. FEBS Lett. 1985;193:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z, Huang L, Shulmeister V M, Chi Y-I, Kim K K, Hung L-W, Crofts A R, Berry E A, Kim S-H. Electron transfer by domain movement in cytochrome bc1. Nature. 1998;392:677–684. doi: 10.1038/33612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]