Abstract

Myocardial sleeve around human pulmonary veins plays a critical role in the pathomechanism of atrial fibrillation. Besides the well‐known arrhythmogenicity of these veins, there is evidence that myocardial extensions into caval veins and coronary sinus may exhibit similar features. However, studies investigating histologic properties of these structures are limited. We aimed to investigate the immunoreactivity of myocardial sleeves for intermediate filament desmin, which was reported to be more abundant in Purkinje fibers than in ventricular working cardiomyocytes. Sections of 16 human (15 adult and 1 fetal) hearts were investigated. Specimens of atrial and ventricular myocardium, sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes, pulmonary veins, superior caval vein and coronary sinus were stained with anti‐desmin monoclonal antibody. Intensity of desmin immunoreactivity in different areas was quantified by the ImageJ program. Strong desmin labeling was detected at the pacemaker and conduction system as well as in the myocardial sleeves around pulmonary veins, superior caval vein, and coronary sinus of adult hearts irrespective of sex, age, and medical history. In the fetal heart, prominent desmin labeling was observed at the sinoatrial nodal region and in the myocardial extensions around the superior caval vein. Contrarily, atrial and ventricular working myocardium exhibited low desmin immunoreactivity in both adults and fetuses. These differences were confirmed by immunohistochemical quantitative analysis. In conclusion, this study indicates that desmin is abundant in the conduction system and venous myocardial sleeves of human hearts.

Keywords: arrhythmia, caval vein, conduction system, coronary sinus, desmin, pulmonary vein

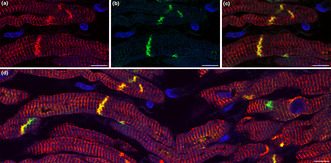

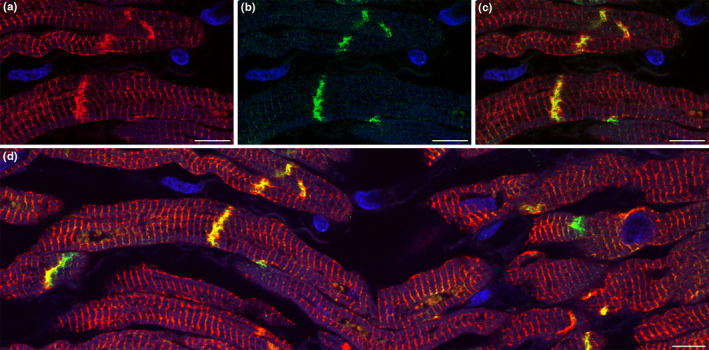

Double labeling immunofluorescence analysis for muscle‐specific intermediate filament desmin (red) and conduction system marker connexin 45 (green). Strong sarcomeric and junctional pattern for desmin labeling is present in the myocardial sleeve of pulmonary vein. Connexin 45 immunoreactivity is restricted to the intercalated discs where it overlaps extensively with desmin. The co‐localisation of connexin 45 and desmin supports the presumed arrhythmogenicity of the venous myocardial sleeves.

1. INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia. It can associate with serious complications such as ischemic stroke and heart failure. Several pathophysiological factors have been reported in the background of atrial fibrillation, namely atrial fibrosis (Gal & Marrouche, 2017; Haemers et al., 2017; Lau et al., 2016; Nattel, 2017), epicardial adipose tissue (Haemers et al., 2017; Lau et al., 2016), inflammatory mechanisms (Haemers et al., 2017; Yao & Veleva, 2018), autonomic nerve activity (Chen et al., 2014; Lau et al., 2016), electrophysiological mechanisms (Lau et al., 2016; Nadadur et al., 2016; Waks & Josephson, 2014) and presence of arrhythmogenic foci (Haïssaguerre et al., 1998; Santangeli & Marchlinski, 2017).

Left atrial myocardium extending into the wall of pulmonary veins and forming myocardial sleeves are well‐known sources of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. Electrophysiological studies indicate that myocardial extensions into caval veins and coronary sinus exhibit similar feature (Chang et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2003; Santangeli et al., 2016; Santangeli & Marchlinski, 2017; Yamaguchi et al., 2010). Arrhythmogenicity of these regions has a well‐established developmental background (Christoffels et al., 2010; Christoffels & Moorman, 2009; Weerd & Christoffels, 2016). However, human studies investigating histologic properties of these structures are limited.

Previously, we examined the connexin 45 immunoreaction to detect the cardiac conduction system and found prominent positive staining in the myocardial sleeves of pulmonary veins, superior caval vein and coronary sinus, indicating their potential pacemaker and/or conducting nature (Kugler et al., 2018). In the current study, we intended to investigate regional differences in desmin immunostaining in human hearts to provide further information about the presumed conducting phenotype of the venous myocardial sleeves. Desmin is a muscle‐specific intermediate filament that plays role in maintaining the structure of sarcomeres, interconnecting the myofibrils through the Z‐disks and linking them to the sarcolemma, the nucleus, and mitochondria (Capetanaki et al., 2007). Albeit desmin is not a dedicated marker for the cardiac pacemaker and conduction system, it was reported to be more abundant in the ventricular conduction system (Liu et al., 2020; Yoshimura et al., 2014) and the nodal regions (Liu et al., 2020; Mavroidis et al., 2020) than in the ventricular working myocardium of human hearts. Intermediate filaments in Purkinje fibers may play a supportive role against mechanical strain during heart contraction (Eriksson & Thornell, 1979) or they might bind glycogen particles and help maintaining the structural integrity of these large cells with peripheral myofibrils (Yoshimura et al., 2014). Impaired desmin has been documented to cause filament assembly defects and abnormal distribution of Ca2+ that may result in cardiac arrhythmias and conduction defects (Su et al., 2022).

2. METHODS

2.1. Human tissues

The work has been ethically approved by the Regional and Institutional Committee of Science and Research Ethics, Semmelweis University (Research Ethics 79 committee approval 122/2016) and the Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Research Council of Hungary (No. IV/1555‐1/2021/EKU). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Demographic data, medical records of patients, and basic data of histological analyses are demonstrated in Table 1. Hearts were removed from cadavers of 15 adult humans. Clinical data were unknown in 8/15 cases. The heart of a 23‐week‐old fetus who was born alive but died at the early perinatal period was also investigated. Prior to death, 7 donors gave written consent for the use of their bodies for education and research {Willed (Whole) Body 77 Program ‐ WWBP}. The remaining 9 hearts were removed from human cadavers during autopsies in possession on ethical approval. Cadavers were kept at 1–5°C until autopsies or fixation, which was performed at 12–72 h postmortem age. After removal during autopsies, hearts were immediately fixed.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and medical data of patients and data of histological analyses.

| Case | Age (years) | Sex | Medical history | Cause of death | Fixation | Investigated tissue | Stain | Quantitative analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Formaldehyde | SCV, RA | HE, desmin (1:200) | No |

| 2 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Formaldehyde | SCV, RA, RV | HE, desmin (1:200) | No |

| 3 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Formaldehyde | SCV, SAN, RA, IAS, RV | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:200) | No |

| 4 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Formaldehyde | SCV, CS, RA, IAS, IVS (left side), LV | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:200) | Yes |

| 5 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Formaldehyde | PV | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:200) | No |

| 6 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Formaldehyde | PV | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:200) | No |

| 7 | 50 | Female | Unknown | Suicide by hanging | Formaldehyde | SCV, CS, PV, SAN, RA, LA, IVS (left side), LV | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:400) | No |

| 8 | 22 | Female | None | Suicide by hanging | Formaldehyde | SCV, CS, PV, SAN, AVN, RA, LA, IVS (right side) | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:200) | Yes |

| 9 | 86 | Female | Hypertension, ischemic stroke, eversion carotid endarterectomy | Postoperative left ventricular failure due to chronic ischaemic heart disease | Formaldehyde | SCV, CS, PV, SAN, RA, LA, IVS (left side) | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:400) | No |

| 10 | 54 | Female | Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (alcohol septal ablation), hypertension, ischemic stroke, liver cirrhosis, surgeries due to strangulated umbilical hernia and small bowel obstruction | Postoperative multiorgan failure and vasoplegia; congestive heart failure | Formaldehyde | SCV, CS, PV, SAN, RA, LA, IVS (left side) | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:400) | No |

| 11 | 43 | Male | Chronic alcohol abuse | Respiratory failure due to pneumonia; accompanying disease: left ventricular hypertrophy | Formaldehyde | SCV, CS, PV, SAN, RA, LA, IVS (left side) | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:400) | Yes |

| 12 | 48 | Male | Nicotinism | Left ventricular failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy | Formaldehyde | SCV, CS, PV, SAN, RA, LA, IVS (left side) | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:400) | Yes |

| 13 | 52 | Male | Master footballer, nicotinism | Sudden cardiac death due to acute myocardial infarction caused by severe three coronary vessel disease | Formaldehyde | SCV, CS, PV, SAN, RA, LA, IVS (left side) | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:400) | Yes |

| 14 | 51 | Female | None | Subarachnoid hemorrhage, respiratory sepsis | Formaldehyde | SCV, CS, PV, SAN, RA, LA, IVS (left and right side), RV | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:400) | No |

| 15 | 64 | Male | Unknown | Unknown | Ethanol | SCV, PV, SAN, AVN, RA, IVS (left and right side) | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:4000–1:5000), connexin 45 (1:50–1:100) | No |

| 16 | 23‐week old fetus | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Ethanol | SCV, SAN, RA, IVS, LV, RV | HE, trichrome, desmin (1:5000), connexin 45 (1:75) | No |

Abbreviations: AVN, atrioventricular node; CS, coronary sinus; HE, hematoxylin–eosin; IAS, interatrial septum; IVS, interventricular septum; LV, left ventricle; PV, pulmonary vein; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; SAN, sinoatrial node; SCV, superior caval vein.

Due to technical reasons, pulmonary veins were investigated in 11/16 and superior caval veins in 14/16 cases. The veins were separated from the atria at the level of their ostia and were cut transversely. Coronary sinus was investigated in 9/16 cases. Tissue samples were also obtained from sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes, left and right atrium, left and right ventricle, and interventricular septum. Specimens were fixed either in 4% formaldehyde (n = 14) or in 70% ethanol (n = 2, including the fetal heart). After dehydration in graded concentrations of alcohol, tissue samples were embedded in paraffin and 3–6 μm sections were prepared. For general histology, paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin and trichrome.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

After deparaffinization and rehydration through graded alcohols, slides were washed three times in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS).

Thereafter, desmin immunohistochemistry of ethanol‐fixed sections was prepared as follows. Heat‐induced citrate‐based antigen retrieval method was applied (Vector Laboratories; Cat# H‐3300) for 30 min. Protein blocking was carried out for 20 min with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with mouse monoclonal antibody against human desmin (Dako; Clone D33; Cat# M0760; dilution 1:4000 for adults and 1:5000 for fetal hearts). Biotinylated horse anti‐mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories; dilution 1:200) was used as a secondary antibody which was followed by an endogenous peroxidase activity‐blocking step using 0,6% hydrogen peroxide (Sigma‐Aldrich) in PBS for 10 min. After the formation of the avidin‐biotinylated peroxidase complex (Vectastain Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories), the binding sites of the primary antibody were visualized by 4‐chloro‐1‐naphthol (Sigma‐Aldrich; Cat# C8890).

For desmin immunohistochemistry performed on formaldehyde‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded tissue sections, a heat‐induced Tris‐EDTA‐based antigen retrieval method was applied (Dako; Target Retrieval Solution pH‐9). Detection of desmin was performed by using mouse anti‐human desmin monoclonal antibody (Dako; Clone D33; Cat# M0760; dilution 1:200 or 1:400) overnight at 4°C. Two different primary antibody concentrations were used due to the somewhat different histological characteristics of the individual specimens. Nevertheless, for different regions of a single heart, the same anti‐desmin antibody dilution was applied. All the other steps of the immunohistochemical protocol (application of peroxidase and protein block, post‐primary blocking, incubation with secondary antibody, applying the 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine as chromogen, counterstaining of the nuclei with hematoxylin) were performed at room temperature (25°C) with Novolink™ Polymer Detection System (Leica Biosystems; Cat# RE7140‐K).

Double labeling immunofluorescence analysis for connexin 45 and desmin was also prepared. Connexin 45 was detected with a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; Cat# sc‐25716; dilution 1:50), while desmin was detected with mouse monoclonal antibody (Dako; Clone D33; Cat# M0760; dilution 1:5000). For fluorescent secondary antibodies, goat anti‐rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 and goat anti‐mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 were applied (Invitrogen). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (Vector Laboratories).

Sections were covered by aqueous Poly/Mount (Polyscience, Inc.) and examined by Zeiss Axiophot photomicroscope and/or Zeiss confocal microscope system. Fluorescent images were captured with an Olympus DP50‐CU digital camera (Olympus Optical Co., Ltd.), whereas an automated 3D‐Histotech whole slide imaging system was used to image other sections.

2.3. Immunohistochemical quantitative analysis

ImageJ (Image Processing and Analysis in Java) program was applied to perform a semiquantitative analysis for the intensity of desmin immunostaining at formaldehyde‐fixed sections of 5 hearts. At least the ventricular subendocardial region, ventricular working myocardium, and one vein was examined in all cases but if possible, six different structures (superior caval vein, pulmonary vein, coronary sinus, sinoatrial node, ventricular conduction system, ventricular working myocardium) were investigated. For each structure, three representative regions were analyzed in the case of 4/5 hearts. Signal intensity of the immunoreactive cells of the conducting system and the extracardiac myocardial sleeves was compared with the ventricular working cardiomyocytes. For this analysis, an equal number of cardiomyocytes were chosen from every region. Difference between signal intensity at representative areas of the ventricular conduction system or myocardial sleeves and the working myocardium was also investigated. The total size of the analyzed areas was equal for each region. The Colour Deconvolution plugin was used to implement stain separation of hematoxylin‐DAB stained images and the derived DAB image was chosen for quantification. Mean gray values of selected cells and areas were then measured and diagrams were created to demonstrate results. More details about quantitative analysis are documented in the Supplementary material.

3. RESULTS

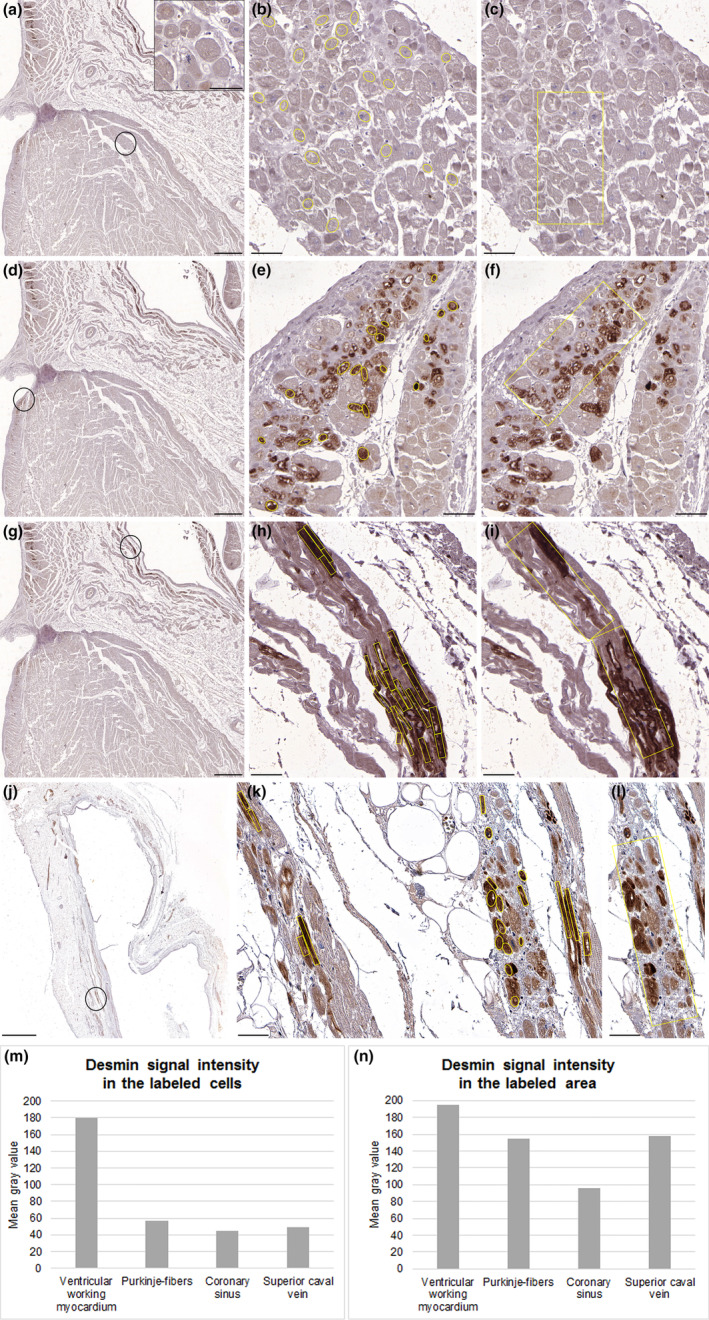

3.1. Quantitative analysis of desmin immunostaining

Quantitative analysis of desmin labeling was prepared on the sections of formaldehyde‐fixed adult hearts (n = 5). Investigation of one heart is detailed below (Figure 1), while quantifications of the other 4 specimens are shown in the Supplementary material (Figures S1‐S10). Distinct structures of the heart were investigated (Figure 1a,d,g,j). There was a marked difference in immunopositivity between ventricular cardiomyocytes and Purkinje fibers (Figures 1b,e) and also between representative areas of the ventricular myocardium and conduction system (Figures 1c,f). Nevertheless, desmin positivity of the working myocardium was obvious. Both highly immunoreactive individual cardiomyocytes and representative region of the myocardial sleeve around the coronary sinus exhibited stronger staining than ventricular myocardium (Figures 1h,i). Myocardial sleeve of the superior caval vein displayed similarly prominent desmin labeling (Figures 1k,l). Based on the quantitative analysis, strongly immunoreactive cells of the conducting system and extracardiac myocardial sleeves exhibited much more prominent desmin signal intensity than ventricular working cardiomyocytes (Figure 1m). However, signal intensities of the examined representative areas differed less. This can be attributed to the mixture of strongly stained conducting‐like cells with less immunoreactive working cardiomyocytes in the myocardial sleeves. Furthermore, non‐staining connective tissue between cardiomyocytes also resulted in higher mean gray values of the examined areas (Figure 1n).

FIGURE 1.

Quantitative analysis of desmin labeling for a formaldehyde‐fixed heart. At the encircled region of ventricular working myocardium (a), both individual cardiomyocytes (b), and the framed area (c) exhibit moderate immunopositivity (a‐inset). At the ventricular subendocardial region (d), Purkinje fibers display strong labeling (e), while some cardiomyocytes are stained weakly (f). In the myocardial sleeve of the coronary sinus (g), most cardiac cells are strongly immunopositive (h) but some cells show modest reaction (i). In myocardial extensions around the superior caval vein (j), most cardiomyocytes display prominent labeling (k), while some cells are weakly positive (l). During quantification, pronounced reduction of mean gray value for Purkinje fibers and strongly immunoreactive cells of the extracardiac myocardial sleeves indicates much stronger desmin signal intensity for these cells than ventricular working cardiomyocytes (m). There was less remarkable difference in mean gray values between representative areas of the ventricular subendocardial region or myocardial sleeves and the working myocardium (n). Scale‐bars: 40 μm (a‐inset), 50 μm (b, c, e, f, h, i, k, l), 1000 μm (a, d, g), 2000 μm (j).

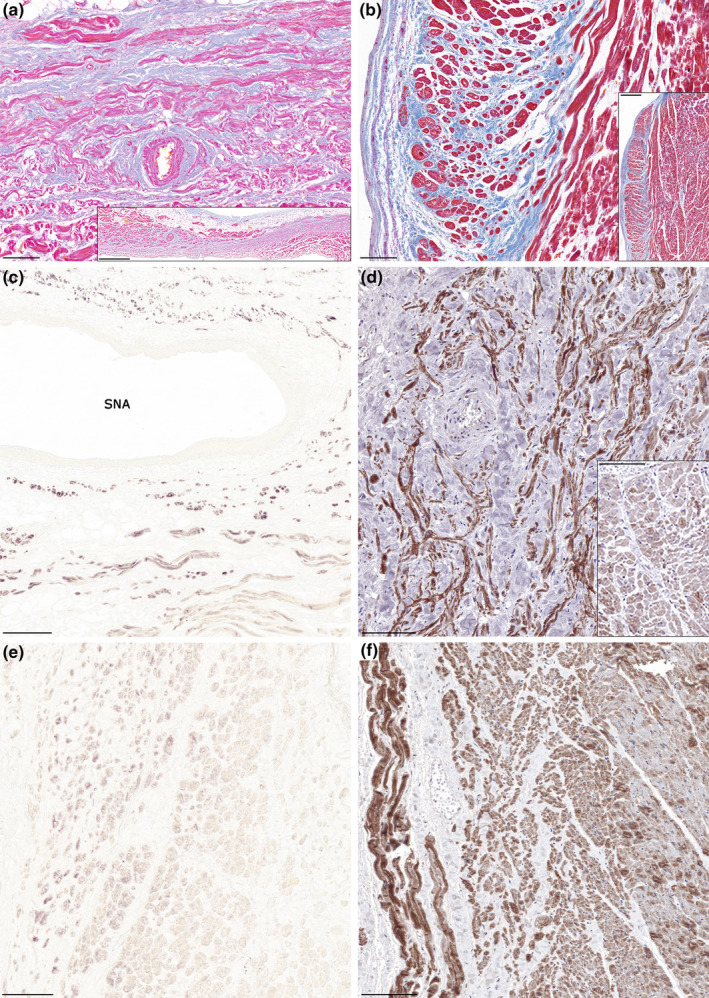

3.2. Cardiac pacemaker and conduction system of the adult hearts

In the adult hearts, regions of the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes as well as the ventricular conduction system at the subendocardial layer of the interventricular septum could be easily identified by hematoxylin–eosin and trichrome stainings. Small pacemaker cells embedded in dense fibrous tissue around the sinoatrial nodal artery and in its adventitial layer as well were characteristic of the sinoatrial node (Figure 2a), while the apex of the triangle of Koch was the site of compact atrioventricular node embedded in the muscular part of atrioventricular septum and surrounded by elongated transitional cells (data not shown). In the ventricular conduction system, large cardiomyocytes (Purkinje fibers) possessing pale cytoplasm and peripheral myofibrils were identified. These cells formed the left and right bundle branches (Figure 2b). Both pacemaker cells of the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes and Purkinje fibers of the ventricular conduction system exhibited strong desmin immunoreactivity compared to the weaker labeling of the surrounding atrial and ventricular working myocardium. These differences were detected at ethanol‐fixed and formaldehyde‐fixed sections as well (Figures 2c–f; Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Desmin immunostaining of the cardiac pacemaker and conduction system. Representative histology images (Krutsay's trichrome) of the sinoatrial node and the ventricular septum (a, b). Small pacemaker cells embedded in dense connective tissue surrounding the sinoatrial nodal artery (a) are characteristic for the sinoatrial node (a‐inset). Left ventricular working myocardium (right side) and the subendocardial conduction system (left side). Purkinje fibers exhibit large cytoplasm with peripheral myofibrils and are embedded in connective tissue (b). An extended area of the ventricular septum is shown in b‐inset. Strong immunopositivity for desmin at the sinoatrial nodal region of ethanol‐fixed (c) and formaldehyde‐fixed (d) hearts. Adjacent atrial working myocardium exhibits weaker labeling (lower part of image [c]; d‐inset). Compared to the weak staining of the working myocardium (right), desmin labeling is pronounced in the ventricular conduction system (left) of the ethanol‐fixed (e) and formaldehyde‐fixed (f) hearts. Label: SNA, sinoatrial nodal artery. Scale‐bars: 100 μm (a, b, d, d‐inset, e, f), 200 μm (c), 500 μm (b‐inset), 1000 μm (a‐inset).

TABLE 2.

Semiquantitative assessment of the prevalence of cardiomyocytes possessing the phenotype of conducting cells (pale cytoplasm, peripheral myofibrils on hematoxylin–eosin or trichrome stained sections) and cardiomyocytes exhibiting strong desmin immunoreactivity in specific regions of the examined hearts.

| Case | Object of semiquantitative assessment (0, none; 1, few; 2, several; 3, abundant) | SCV | CS | PV | SAN | Subendocardium | Working myocardium | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV | IVS | RV | LV | IVS | RV | ||||||

| 1 | Conducting‐like CMs | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 2 | Conducting‐like CMs | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | — | — | 0 |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | — | — | 0 | |

| 3 | Conducting‐like CMs | 2 | — | — | 3 | — | — | 2 | — | — | 0 |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 0 | — | — | 1 | — | — | 2 | — | — | 0 | |

| 4 | Conducting‐like CMs | 2 | 3 | — | — | — | 3 | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 1 | 2 | — | — | — | 2 | — | 0 | 0 | — | |

| 5 | Conducting‐like CMs | — | — | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 6 | Conducting‐like CMs | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 7 | Conducting‐like CMs | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | — | 3 | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | — | 2 | — | 0 | 0 | — | |

| 8 | Conducting‐like CMs | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | 0 | — |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | 1 | — | |

| 9 | Conducting‐like CMs | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | 0 | — |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | — | 2 | — | — | 0 | — | |

| 10 | Conducting‐like CMs | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | 0 | — |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | — | 2 | — | — | 1 | — | |

| 11 | Conducting‐like CMs | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | 0 | — |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | — | 3 | — | — | 1 | — | |

| 12 | Conducting‐like CMs | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | 0 | — |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | — | 2 | — | — | 0 | — | |

| 13 | Conducting‐like CMs | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | — | 2 | — | — | 0 | — |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 2 | 2 | NA | 3 | — | 2 | — | — | 1 | — | |

| 14 | Conducting‐like CMs | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | — | 2 | 2 | — | 0 | 0 |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | — | 2 | 2 | — | 0 | 1 | |

| 15 | Conducting‐like CMs | 2 | — | 2 | 3 | — | 2 | — | — | 0 | — |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 2 | — | 2 | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | 0 | — | |

| 16 | Conducting‐like CMs | NA | — | — | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CMs with strong desmin labeling | 2 | — | — | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Note: Presence of conducting‐like cardiomyocytes could not be clearly evaluated in case of the fetal heart. Desmin immunostaining could not be performed for the PV of case No. 13 and the SAN of case No. 14. due to technical reasons.

Abbreviations: CMs, cardiomyocytes; CS, coronary sinus; IVS, interventricular septum; LV, left ventricle; NA, not applicable; PV, pulmonary vein; RV, right ventricle; SAN, sinoatrial node; SCV, superior caval vein.

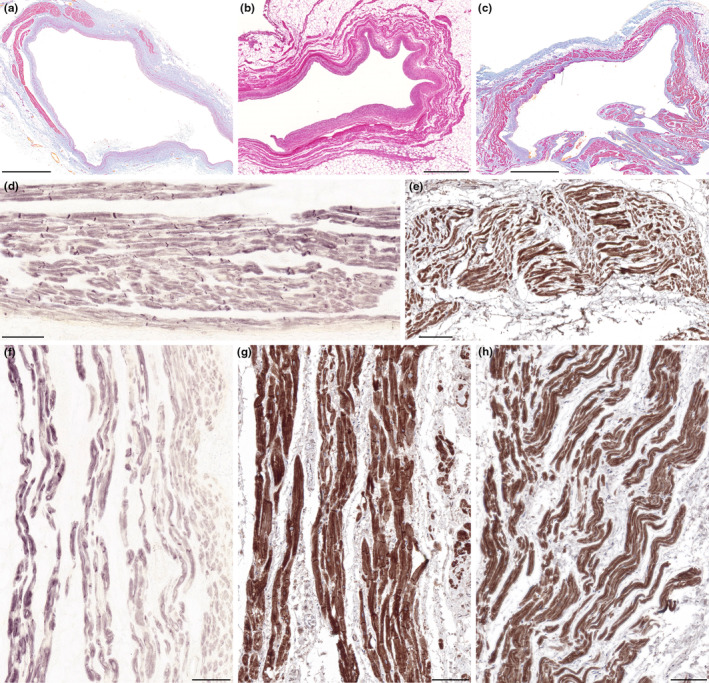

3.3. Myocardial sleeves of pulmonary veins, superior caval veins and coronary sinus in the adult hearts

Myocardial sleeves were present around all examined pulmonary vein, superior caval vein, and coronary sinus samples (Figures 3a–c). Bundles of cardiomyocytes exhibiting similar morphology to Purkinje fibers or pacemaker cells were present in all myocardial sleeves investigated, albeit their amount was different in each sample (Table 2). Purkinje‐like cardiomyocytes were larger in size than working cardiomyocytes and possessed pale cytoplasm and peripheral myofibrils, while nodal‐like cardiomyocytes had particularly small diameter. These conducting‐like cells were frequently embedded in fine collagen fiber networks. Intense desmin immunoreactivity was detected in myocardial extensions into pulmonary veins of both ethanol‐fixed and formaldehyde‐fixed hearts (Figures 3d,e). Similarly, myocardial sleeves of superior caval veins proved to be strongly immunopositive for desmin compared to the atrial and ventricular working myocardium (Figures 3f,g). Abundant desmin labeling could be also observed in the myocardial sleeves surrounding the formaldehyde‐fixed coronary sinus samples (Figure 3h). The amount of cardiomyocytes showing prominent desmin staining differed between the samples (Table 2). Strongly immunoreactive cardiomyocytes frequently displayed similar morphological phenotypes to Purkinje fibers or nodal cardiomyocytes.

FIGURE 3.

Desmin immunostaining of the venous myocardial sleeves. Representative histology images (hematoxylin–eosin [b] and Krutsay's trichrome [a, c]) of the myocardial sleeves. Cross‐section of a pulmonary vein. This part of the vein is partially covered by myocardial sleeve. Cardiomyocytes are localized on the outer side of the venous adventitia (a). Cross‐section of a superior caval vein with myocardial sleeve (b). Transverse section of the coronary sinus in the level of its right atrial orifice. Myocardial sleeve is present around the venous wall (c). Prominent desmin immunoreactivity was observed in the myocardial sleeves around pulmonary veins of ethanol‐fixed (d) and formaldehyde‐fixed (e) hearts. Desmin labeling is remarkable in myocardial extensions around both the ethanol‐fixed (f) and formaldehyde‐fixed (g) superior caval veins. In the myocardial sleeve of the formaldehyde‐fixed coronary sinus, several cardiomyocytes show pronounced immunoreactivity for desmin as well (h). Scale‐bars: 100 μm (d–h), 1000 μm (b), 2000 μm (a, c).

3.4. Double‐immunolabeling of desmin and connexin 45 in an adult heart

Double labeling immunofluorescence analysis for desmin and conduction system marker connexin 45 showed a strong sarcomeric and junctional pattern for desmin labeling in the myocardial sleeve of the ethanol‐fixed pulmonary vein (Figure 4a). Although connexin 45 immunoreactivity was also intense, it was restricted to the intercalated discs (Figure 4b) where it overlapped extensively with desmin (Figures 4c,d). The co‐localisation of these two markers further supports the presumed arrhythmogenicity of this region.

FIGURE 4.

Double‐labeling of desmin and connexin 45 in the myocardial sleeve of a pulmonary vein. Cardiomyocytes display intense red fluorescence which means strong positivity for desmin (a). Connexin 45 expression (green) is detected only between neighboring cardiomyocytes (b) where it colocalizes with desmin resulting in yellow fluorescent signal (c). Double‐immunolabeling of desmin and connexin 45 is also demonstrated at a more extensive area (d). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale‐bars: 10 μm (a–d).

3.5. Human fetal heart

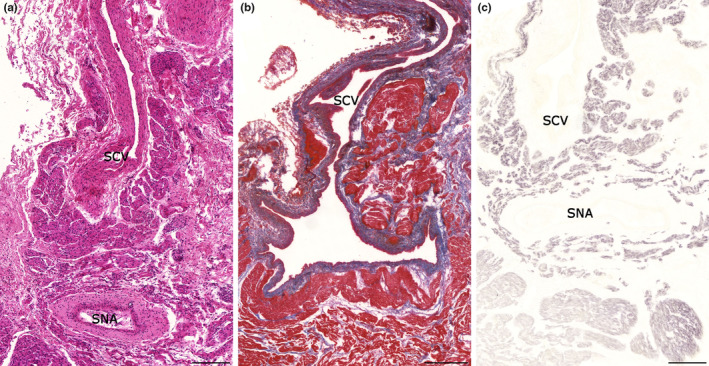

In the 23‐week‐old human fetus, pacemaker cells of the sinoatrial node and Purkinje fibers of the ventricular conduction system could not be differentiated clearly from working cardiomyocytes. However, the sinoatrial nodal region could be identified based on its localization and its artery. Myocardial extensions into the superior caval vein could be observed (Figures 5a,b). Similarly to human adults, prominent desmin labeling was detected in the myocardial sleeve of the fetal superior caval vein. Immunoreaction for desmin was also intense at the sinoatrial nodal region (Figure 5c).

FIGURE 5.

Histology of a 23‐week old human fetal heart. Longitudinal section of superior caval vein. Myocardial extensions can be observed around the wall of the vein. Sinoatrial node with its artery is localized near to the right atrial orifice of the superior caval vein. Hematoxylin–eosin (a). Krutsay's trichrome staining indicates that the myocardial sleeve (red) is localized outside of the venous adventitia (blue) (b). Compared to the adjacent atrial myocardium, desmin immunoreactivity is strongly positive in both the myocardial sleeve around the superior caval vein and the sinoatrial node (c). Labels: SNA, sinoatrial nodal artery; SCV, superior caval vein. Scale bars: 200 μm (a, c), 400 μm (b).

4. DISCUSSION

Although there is a growing knowledge of the possible pathomechanisms of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, the histologic characteristics of the arrhythmogenic regions are still obscure. Based on previous human (Kugler et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2009; Perez‐Lugones et al., 2003) and animal (Masani, 1986) studies, it seems that cardiomyocytes with a similar phenotype to the cardiac pacemaker or conduction cells are present in the myocardial sleeves around pulmonary veins, caval veins and coronary sinus. Few data are available about the immunohistologic features of these regions in humans (Blom et al., 1999; Kholová et al., 2003; Kugler et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2009) and animals (Yamamoto et al., 2006; Yeh et al., 2001; Yeh et al., 2003).

In the current study, we aimed to further characterize the myocardial sleeves with the comparative examination of a general marker of myocytes, the desmin. In the left ventricular myocardium, progressively increased desmin intensity was reported with increasing fetal age in humans (Kim, 1996). It was also found that bovine Purkinje fibers possess numerous intermediate filaments but less myofibrils compared to working cardiomyocytes (Eriksson et al., 1978; Eriksson & Thornell, 1979; Thornell & Eriksson, 1981). Later mammalian studies verified stronger desmin immunoreactivity for the ventricular conduction system compared to the working cardiomyocytes both during the prenatal development (Franco & Icardo, 2001; Ya et al., 1997) and in adults (Vitadello et al., 1990; Ya et al., 1997). Abundant desmin labeling was detected also in the Purkinje fibers of humans (Yoshimura et al., 2014). Obvious difference in desmin immunostaining was observed between ventricular working cardiomyocytes and Purkinje fibers during the current research as well. Intense desmin labeling was reported in the developing human sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes (Liu et al., 2020). In adult mice and human samples, a high amount of desmin was found in the sinoatrial node as well (Mavroidis et al., 2020). Similarly, stronger desmin immunoreactivity was detected in the sinoatrial node compared to the atrial working myocardium in our study. The atrioventricular conductive axis of rabbits could be easily distinguished by prominent desmin immunostaining within the cytoplasm of conducting cardiomyocytes (Ko et al., 2004).

Conducting phenotype of the myocardial sleeves might be explained by developmental factors. Embryonic systemic veins have a substantial overlap in gene expression with the future sinus node. Tbx3 and Hcn4 expressing venous pole of the primary heart tube exhibits high pacemaker activity while later it confines to the sinoatrial node. Incomplete atrialization of sinus venosus‐derived structures, such as superior caval vein (right sinus horn), crista terminalis (right venous valve), coronary sinus ostium (atrial entrance of the left sinus horn), and ligament of Marshall (remnant of the left sinus horn) may result in the persistence of focal automatic activity. Development of the pulmonary venous myocardium is different as it forms independently from the sinus venosus, and displays an atrial working myocardial phenotype and gene program (Tbx18/Hcn4‐negative; Christoffels & Moorman, 2009; Christoffels et al., 2010; Weerd & Christoffels, 2016).

Data about desmin labeling of extranodal supraventricular regions is sparse. In fetal rats, strong desmin immunoreactivity was noted in the sinoatrial node, the superior caval vein, and the myocardium along pulmonary veins (Ya et al., 1997). Interatrial conducting pathway was reported to exhibit strong desmin immunolabeling compared to working cardiomyocytes in monkeys and sheeps (Yamaguchi et al., 2009). However, description of desmin expressing supraventricular structures in human adults is lacking. Only fetal data are available which indicates that similarly to the ventricular conduction system, atrial walls, pulmonary veins, caval veins, and coronary sinus are strongly positive for desmin, while the left ventricle is immunonegative. Mechanical stress caused by involvement of the venous walls in atrial development was thought to induce desmin expression (Yamamoto et al., 2011). Studies on human embryos (Liu et al., 2020) and fetuses (Grigore et al., 2012) reported strong desmin immunoreactivity of the atria compared to weaker (Grigore et al., 2012) or absent (Liu et al., 2020) signal at the ventricular (compact) myocardium.

Based on the lacking data for desmin expression in supraventricular regions of human adults, we examined specimens both from fetal and adult hearts. Strong labeling for desmin in the myocardial sleeve of the fetal superior caval vein is in agreement with Yamamoto et al.'s (2011) report but interestingly, prominent desmin immunoreactivity was found in the pulmonary and non‐pulmonary venous myocardial sleeves of adults as well. Consequently, it is likely that desmin highlights not only the pacemaker and conduction system but also those supraventricular regions which may trigger atrial tachyarrhythmias. Quantification of desmin labeling verified a considerable difference in signal intensity between the ventricular subendocardial region or venous myocardial sleeves and the working myocardium supporting the theory that desmin marks the supraventricular regions in which arrhythmogenic foci may appear. Interestingly enough, cardiomyocytes exhibiting conducting‐like phenotype and strong desmin immunoreactivity were identified in the venous myocardial sleeves of all hearts irrespective of age and cardiovascular history. It is also of note that albeit working myocardium displayed weaker signal intensity than the conduction system, its desmin positivity was obvious. Therefore application of desmin as a selective marker for pacemaker or conducting cardiomyocytes does not seem to be plausible.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Based on the results of the current study on human hearts, we conclude that immunostaining of desmin intermediate filaments is obviously stronger for the ventricular conduction system as well as for supraventricular arrhythmogenic regions than for ventricular working myocardium. Although desmin cannot be applied as a selective marker for the cardiac pacemaker and conduction systems, but prominent desmin immunoreaction coincides with the territory of pulmonary and nonpulmonary myocardial sleeves, the sites of arrhythmogenic foci.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.K. substantially contributed to the design of the study, acquisition, and analysis of data, revision of the literature, and selection of relevant articles. She was also a major contributor in drafting the manuscript. A.M.T. and N.N. contributed to the design of the study, acquisition, and analysis of data, particularly to the immunohistochemistry staining, and revised the manuscript. A.F., K.D., K.T., and G.R. prepared and provided human cardiac samples in possession of ethical approval and revised the manuscript. M.S. figured out the method of sinoatrial node preparation and revised the manuscript. Á.N. substantially contributed to the conception and design of the study, analysis, and interpretation of data, selection of articles and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by institutional funds and by István Apáthy Foundation's Research Grant. N.N. is supported by the Research Excellence Programme of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology in Hungary, within the framework of the TKP2021‐EGA‐25 thematic programme of the Semmelweis University, and by the Hungarian Science Foundation NKFI grant (138664).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no relevant financial or non‐financial interests to disclose.

Supporting information

Data S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to express their gratitude to those who donated their bodies to the University of Semmelweis for anatomical education and research. We are also grateful to Ákos Lukáts MD, PhD, Rita Padányi MD, PhD, Eszter Regős MD, PhD, Gertrúd Forika MD, PhD, Kata Pálos MD, Noémi Jákob MD, Erzsébet Kovács, Viktória Halasy, Judit Fogarasi, Lili Orbán, Ferenc Kilin, Dorottya Csernus‐Horváth, Eszter Pál, Balázs Szalay, Rita Körtvélyessy, Rebeka Bertalan for their excellent technical assistance during tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry studies.

Kugler, S. , Tőkés, A.‐M. , Nagy, N. , Fintha, A. , Danics, K. , Sághi, M. et al. (2024) Strong desmin immunoreactivity in the myocardial sleeves around pulmonary veins, superior caval vein and coronary sinus supports the presumed arrhythmogenicity of these regions. Journal of Anatomy, 244, 120–132. Available from: 10.1111/joa.13947

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The most relevant data generated during the current study are included in this published article. Other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Blom, N.A. , Gittenberger‐de Groot, A.C. , DeRuiter, M.C. , Poelmann, R.E. , Mentink, M.M.T. & Ottenkamp, J. (1999) Development of the cardiac conduction tissue in human embryos using HNK‐1 antigen expression: possible relevance for understanding of abnormal atrial automaticity. Circulation, 99, 800–806. Available from: 10.1161/01.cir.99.6.800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capetanaki, Y. , Bloch, R.J. , Kouloumenta, A. , Mavroidis, M. & Psarras, S. (2007) Muscle intermediate filaments and their links to membranes and membranous organelles. Experimental Cell Research, 313, 2063–2076. Available from: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.Y. , Lo, L.W. , Lin, Y.J. , Chang, S.L. , Hu, Y.F. , Li, C.H. et al. (2013) Long‐term outcome of catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation originating from non pulmonary vein ectopy. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology, 24, 250–258. Available from: 10.1111/jce.12036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.S. , Chen, L.S. , Fishbein, M.C. , Lin, S.F. & Nattel, S. (2014) Role of the autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation. Pathophysiology and Therapy. Circulation Research, 114, 1500–1515. Available from: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffels, V.M. & Moorman, A.F.M. (2009) Development of the cardiac conduction system: why are some regions of the heart more arrhythmogenic than others? Circulation Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, 2, 195–207. Available from: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.829341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffels, V.M. , Smits, G.J. , Kispert, A. & Moorman, A.F.M. (2010) Development of the pacemaker tissues of the heart. Circulation Research, 106, 240–254. Available from: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.205419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, A. & Thornell, L.E. (1979) Intermediate (skeletin) filaments in heart Purkinje fibers. A correlative morphological and biochemical identification with evidence of a cytoskeletal function. The Journal of Cell Biology, 80, 231–247. Available from: 10.1083/jcb.80.2.231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, A. , Thornell, L.E. & Stigbrand, T. (1978) Cytoskeletal filaments of heart conducting system localized by antibody against a 55,000 Dalton protein. Experientia, 34, 792–794. Available from: 10.1007/BF01947331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco, D. & Icardo, J.M. (2001) Molecular characterization of the ventricular conduction system in the developing mouse heart: topographical correlation in normal and congenitally malformed hearts. Cardiovascular Research, 49, 417–429. Available from: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00252-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal, P. & Marrouche, N.F. (2017) Magnetic resonance imaging of atrial fibrosis: redefining atrial fibrillation to a syndrome. European Heart Journal, 38, 14–19. Available from: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigore, A. , Arsene, D. , Filipoiu, F. , Cionca, F. , Enache, S. , Ceauşu, M. et al. (2012) Cellular immunophenotypes in human embryonic, fetal and adult heart. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology, 53, 299–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haemers, P. , Hamdi, H. , Guedj, K. , Suffee, N. , Farahmand, P. , Popovic, N. et al. (2017) Atrial fibrillation is associated with the fibrotic remodelling of adipose tissue in the subepicardium of human and sheep atria. European Heart Journal, 38, 53–61. Available from: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haïssaguerre, M. , Jaïs, P. , Shah, D.C. , Takahashi, A. , Hocini, M. , Quiniou, G. et al. (1998) Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. The New England Journal of Medicine, 339, 659–666. Available from: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kholová, I. , Niessen, H.W.M. & Kautzner, J. (2003) Expression of Leu‐7 in myocardial sleeves around human pulmonary veins. Cardiovascular Pathology, 12, 263–266. Available from: 10.1016/s1054-8807(03)00078-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.D. (1996) Expression of intermediate filament desmin and vimentin in the human fetal heart. The Anatomical Record, 246, 271–278. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko, Y.S. , Yeh, H.I. , Ko, Y.L. , Hsu, Y.C. , Chen, C.F. , Wu, S. et al. (2004) Three‐dimensional reconstruction of the rabbit atrioventricular conduction axis by combining histological, desmin, and connexin mapping data. Circulation, 109, 1172–1179. Available from: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000117233.57190.BD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugler, S. , Nagy, N. , Rácz, G. , Tőkés, A.M. , Dorogi, B. & Nemeskéri, Á. (2018) Presence of cardiomyocytes exhibiting Purkinje‐type morphology and prominent connexin45 immunoreactivity in the myocardial sleeves of cardiac veins. Heart Rhythm, 15, 258–264. Available from: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.09.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, D.H. , Schotten, U. , Mahajan, R. , Antic, N.A. , Hatem, S.N. , Pathak, R.K. et al. (2016) Novel mechanisms in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation: practical applications. European Heart Journal, 37, 1573–1581. Available from: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H. , Tai, C.T. , Hsieh, M.H. , Tsao, H.M. , Lin, Y.J. , Chang, S.L. et al. (2005) Predictors of non‐pulmonary vein ectopic beats initiating paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: implication for catheter ablation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 46, 1054–1059. Available from: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.S. , Tai, C.T. , Hsieh, M.H. , Tsai, C.F. , Lin, Y.K. , Tsao, H.M. et al. (2003) Catheter ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation initiated by non‐pulmonary vein ectopy. Circulation, 107, 3176–3183. Available from: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000074206.52056.2D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.X. , Jing, Y.X. , Wang, J.J. , Yang, Y.P. , Wang, Y.X. , Li, H.R. et al. (2020) Expression patterns of intermediate filament proteins desmin and Lamin a in the developing conduction system of early human embryonic hearts. Journal of Anatomy, 236, 540–548. Available from: 10.1111/joa.13108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masani, F. (1986) Node‐like cells in the myocardial layer of the pulmonary vein of rats: an ultrastructural study. Journal of Anatomy, 145, 133–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavroidis, M. , Athanasiadis, N.C. , Rigas, P. , Kostavasili, I. , Kloukina, I. , te Rijdt, W.P. et al. (2020) Desmin is essential for the structure and function of the sinoatrial node: implications for increased arrhythmogenesis. American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 319, 557–570. Available from: 10.1152/ajpheart.00594.2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadadur, R.D. , Broman, M.T. , Boukens, B. , Mazurek, S.R. , Yang, X. , van den Boogaard, M. et al. (2016) Pitx2 modulates a Tbx5‐dependent gene regulatory network to maintain atrial rhythm. Science Translational Medicine, 8, 354ra115. Available from: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf4891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattel, S. (2017) Molecular and cellular mechanisms of atrial fibrosis in atrial fibrillation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol, 3, 425–435. Available from: 10.1016/j.jacep.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, B.L. , Fishbein, M.C. , Chen, L.S. , Chen, P.S. & Masroor, S. (2009) Histopathological substrate for chronic atrial fibrillation in humans. Heart Rhythm, 6, 454–460. Available from: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez‐Lugones, A. , McMahon, J.T. , Ratliff, N.B. , Saliba, W.I. , Schweikert, R.A. , Marrouche, N.F. et al. (2003) Evidence of specialized conduction cells in human pulmonary veins of patients with atrial fibrillation. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology, 14, 803–809. Available from: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03075.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangeli, P. & Marchlinski, F.E. (2017) Techniques for the provocation, localization, and ablation of non‐pulmonary vein triggers for atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm, 14, 1087–1096. Available from: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangeli, P. , Zado, E.S. , Hutchinson, M.D. , Riley, M.P. , Lin, D. , Frankel, D.S. et al. (2016) Prevalence and distribution of focal triggers in persistent and long‐standing persistent atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm, 13, 374–382. Available from: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, W. , van Wijk, S.W. & Brundel, B.J.J.M. (2022) Desmin variants: trigger for cardiac arrhythmias? Frontiers in Cell and Development Biology, 10, 986718. Available from: 10.3389/fcell.2022.986718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornell, L.E. & Eriksson, A. (1981) Filament systems in the Purkinje fibers of the heart. The American Journal of Physiology, 241, 291–305. Available from: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.241.3.H291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitadello, M. , Matteoli, M. & Gorza, L. (1990) Neurofilament proteins are co‐expressed with desmin in heart conduction system myocytes. Journal of Cell Science, 97, 11–21. Available from: 10.1242/jcs.97.1.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waks, J.W. & Josephson, M.E. (2014) Mechanisms of atrial fibrillation—reentry, rotors and reality. Arrhythmia & Electrophysiology Review (AER), 3, 90–100. Available from: 10.15420/aer.2014.3.2.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerd, J.H. & Christoffels, V.M. (2016) The formation and function of the cardiac conduction system. Development, 143, 197–210. Available from: 10.1242/dev.124883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ya, J. , Markman, M.W. , Wagenaar, G.T. , Blommaart, P.J. , Moorman, A.F. & Lamers, W.H. (1997) Expression of the smooth‐muscle proteins alpha‐smooth‐muscle Actin and calponin, and of the intermediate filament protein desmin are parameters of cardiomyocyte maturation in the prenatal rat heart. The Anatomical Record, 249, 495–505. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, T. , Tsuchiya, T. , Miyamoto, K. , Nagamoto, Y. & Takahashi, N. (2010) Characterization of non‐pulmonary vein foci with an EnSite array in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Europace, 12, 1698–1706. Available from: 10.1093/europace/euq326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, T. , Yi, S.Q. , Tanaka, S. , Ono, K. & Shimada, T. (2009) Ultrastructure and cytoarchitecture of Bachmann's bundle in the mammalian heart. Journal of Arrhythmia, 25, 24–31. Available from: 10.4020/jhrs.25.24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, M. , Abe, S. , Rodríguez‐Vázquez, J.F. , Fujimiya, M. , Murakami, G. & Ide, Y. (2011) Immunohistochemical distribution of desmin in the human fetal heart. Journal of Anatomy, 219, 253–258. Available from: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01382.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, M. , Dobrzynski, H. , Tellez, J. , Niwa, R. , Billeter, R. , Honjo, H. et al. (2006) Extended atrial conduction system characterised by the expression of the HCN4 channel and connexin45. Cardiovascular Research, 72, 271–281. Available from: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, C. & Veleva, T. (2018) Enhanced cardiomyocyte NLRP3 inflammasome signaling promotes atrial fibrillation. Circulation, 138, 2227–2242. Available from: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, H.I. , Lai, Y.J. , Lee, S.H. , Lee, Y.N. , Ko, Y.S. , Chen, S.A. et al. (2001) Heterogeneity of myocardial sleeve morphology and gap junctions in canine superior vena cava. Circulation, 104, 3152–3157. Available from: 10.1161/hc5001.100836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, H.I. , Lai, Y.J. , Lee, Y.N. , Chen, Y.J. , Chen, Y.C. , Chen, C.C. et al. (2003) Differential expression of connexin43 gap junctions in cardiomyocytes isolated from canine thoracic veins. The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry, 51, 259–266. Available from: 10.1177/002215540305100215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura, A. , Yamaguchi, T. , Kawazato, H. , Takahashi, N. & Shimada, T. (2014) Immuno‐histochemistry and three‐dimensional architecture of the intermediate filaments in Purkinje cells in mammalian hearts. Medical Molecular Morphology, 47, 233–239. Available from: 10.1007/s00795-014-0069-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.

Data Availability Statement

The most relevant data generated during the current study are included in this published article. Other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.