Abstract

The vic-dioximes are compounds with various industrial uses and scientific applications. Many coordination compounds have been synthesized based on vic-dioximes. This study presents the synthesis and full characterization of two vic-dioximes based on dichloroglyoxime, p-aminobenzoic acid, and p-aminotoluene. Their structures were proved by IR, 1H, 13C and 15N NMR spectral analysis, and single crystal X-ray diffraction. One of the reported vic-dioximes, bis(di-p-aminotoluene)glyoxime mono-p-aminotoluene trihydrate showed good to moderate antimicrobial activity against both nonpathogenic gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas fluorescens), phytopathogenic (Xanthomonas campestris, Erwinia amylovora, E. carotovora) and the fungi (Candida utilis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) at MIC – 70–150 μg/mL.

Keywords: vic-dioxime, spectral analysis, X-ray diffraction, antibacterial activity, antifungal activity

1. Introduction

vic-Dioximes are widely used as general industrial chemical compounds [1], analytical reagents [2,3], model for biological system [4–7], as well as catalysts in various chemical processes [8,9]. Since the early 1900s vic-dioximes have been used extensively as chelating agents in coordination chemistry [10–13]. Even today vic-dioximes and their complexes constitutes an important class with a versatile reactivity [6,8]. Due to the position of two oximic groups, these compounds can exist as three stereoisomeric forms: anti-(E,E), amfi-(E,Z) and sin-(Z,Z), which also influence the modality of metal coordination. The most common is the N-N-chelation coordination mode favored by the anti-(E,E) form [6,13,14], but the coordination of these ligands via oxygen atoms from oximic groups is also known [15,16]. vic-Dioximes can form coordination compounds in molecular [17,18], monodeprotonated [19–22] and bis-deprotonated [23] forms. In the coordinated state the intramolecular hydrogen bonds between the oxime anions can be replaced with boron compounds (BF2+, BF2+, B(C6H5)2+, B(OH)2+), thus, encapsulating the respective compounds [24–27]. In the literature, are described the vicinal dioximes containing either aliphatic or aromatic amines [28–34], for which creation the dichloroglyoxime (DClH2) can be used as a precursor. Also, starting from dichloroglyoxime, a new dioximic ligand was synthesized by condensation with the thiolic derivative - octane-1-thiol, and, based on the obtained dioxime, a Ni-(II) complex was synthesized [35].

The condensation reaction of amines or thiols with dichloroglyoxime leads to the formation of different di-, tetra-, poliamino-derivatives or substituted thioglyoximes [17,36]. Through such kind of reactions, a series of new dioximes have been synthesized [17,37–39]. Both, the oxime and coordination compounds obtained based on their basis show a wide range of pharmacological activities, including antibacterial, antifungal and antidepressant [40–42].

The purposes of this work were the synthesis of new vic-dioxime ligands by the condensation of dichloroglyoxime with p-aminobenzoic acid (paba) and p-aminotoluene (pat), their structure elucidation using modern methods of analysis and biological activity assessments against seven strains of nonpathogenic and phytopatogenic bacteria and fungi.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

All the reactions were conducted at the room temperature or a moderate heating. All the reagents were purchased from Merck and Aldrich and were used without further purification unless noted otherwise.

2.2. Methods

Melting points (m.p.) were measured on a Boetius hot stage and are uncorrected. Infrared spectra (IR) were recorded on a FTIR Spectrum-100 Perkin Elmer spectrometer in Nujol (400–4000 cm−1) and using ATR technique (650–4000 cm−1). The UV-Vis spectra were recorded in methanol on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 25 spectrometer (400–4000 nm), at a concentration of compounds 1 and 2 (c = 0,33·10−5 mol/L and c = 0,23·10−5 mol/L). 1H, 13C and 15N NMR spectra were recorded in DMSO-d6 (99.95 %) on a Bruker Avance DRX 400 (400.13, 100.61 and 40.54 MHz). Chemical shifts (d) are reported in ppm and are referenced to the residual nondeuterated solvent peak (2.50 ppm for 1H and 39.50 ppm for 13C). Coupling constants (J) are reported in Hertz (Hz). The following abbreviations were used to explain the multiplicities: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, qvin. = quintet, sex = sextet, m = multiplet, brs = broad singlet. X-ray analyses on single crystal were performed on a Xcalibur E diffractometers with a CCD detector using graphite-monochromatized MoKα radiation at room temperature.

2.3. Synthesis

2.3.1. Synthesis of bis(p-aminobenzoic acid)-glyoxime hydrate [H4L1]·H2O (1)

The yellow solution resulted after dissolving of dichloroglyoxime (0.31 g, 0.02 mol) and p-aminobenzoic acid (0.55 g, 0.04 mol) in MeOH (10 mL) was stirred for 15 min. Then, to the reaction mixture, consecutively, Na2CO3 (0.21 g, 0.02 mol) was added and after 15 min H2O (3 mL) was added with additional stirring for 2 h. As result, a radish-yellow sediment was obtained, then filtered through a glass filter and washed, consecutively, with MeOH and Et2O. After drying, a beige product (0.395 g, 56%) soluble in DMF and DMSO was obtained. The filtrate has been passed into a chemical beaker and allowed to crystallize at room temperature. After six days, yellowish needle shaped crystals were obtained. m.p. 281–284 °C. Anal. Calcd. for C16H16N4O7 (376.23): (430.09): C, 51.07; H, 4.28; N, 14.89. Found: C, 50.93; H, 4.30; N, 14.79. IR (nmax/cm−1): 3535 (ν(OH)H2O), 3180 (ν(OH)oxime+ ν(NH)), 1677 (ν(C=O)), 1652 (ν(C=N)), 1600, 1519, 1459 (ν(C=C)), 854 (δ(CH)arom. nonplan.). 1HNMR (400.13 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): d 10.92 (l.s., 2H, CO2H), 8.75 (s, 2H, NH), 7.66 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 4H, C2-C6, C2′-C6′), 6.82 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 4H, C3-C5, C3′-C5′). 13CNMR (100.61 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) d 167.6 (COOH), 144.55 (C4, C4′), 142.32 (C8, C9), 130.45 (C2-C6, C2′-C6′), 123.19 (C1, C1′), 117.92 (C3-C5, C3′-C5′). 15NNMR (40.54 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): d 100.9.

2.3.2. Synthesis of bis(di-p-aminotoluene)-glyoxime mono-p-aminotoluene trihydrate [(H2L2)2] pat·3H2O (2)

The yellow solution resulted after dissolving of dichloroglyoxime (0.31 g, 0,02 mol) and p-aminotoluene (0.48 g, 0,04 mol) in EtOH (10 mL) was stirred for 15 min. Then, to the reaction mixture, consecutively, Na2CO3 (0.21 g, 0.02 mol) was added and after 15 min H2O (3 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was heated at 50 °C for 40 min until complete carbonate dissolving, then heating was stopped and it was stirred for 1.5 h. As result, a white coloured sediment was obtained, then filtered through a glass filter and washed with Et2O. After drying, it was obtained a beige product (0.78 g, 53%) soluble in DMF, MeOH, EtOH, DMSO and insoluble in H2O. The filtrate has been passed into a chemical beaker and allowed to crystallize at room temperature. After one week, radish needle shaped crystals were obtained. m.p. 205–207 °C. Anal. Calcd. for C39H51N9O7 (757.89):C, 61.80; H, 6.78; N, 16.64. Found: C, 61.93; H, 6.71; N, 16.72. IR (nmax/cm−1): 3676 (ν(OH) oxime), 3371 (νas(NH2)), 3308 (νs(NH2)), 3187 (ν(NH)), 1614 (δ(NH2)), 1516, 1452, 1407 (ν(C=C)), 812 (δ(CH)arom.nonplan.). 1HNMR (400.13 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) d 10.36 (l.s., 2H, >N-OH), 8.44 (s, 2H, NH), 6.88 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 4H, C3-C5, C3′-C5′), 6.67 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 4H, C2-C6, C2′-C6′), 2.16 (s, 6H, 2xC7,7′-H3). 13CNMR (100.61 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) d 143.56 (C1, C1′), 137.43 (C8, C9), 131.05 (C4, C4′), 129.26 (C3-C5, C3′-C5′), 119.77 (C2-C6, C2′-C6′), 20.64 (C7, C7′). 15NNMR (40.54 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): d 97.1.

2.4. Microbiological activity assessments

Antimicrobial activity evaluation of both compounds was performed on the following microorganisms: nonpathogenic gram-positive and gram-negative strains of Bacillus subtilis NCNM BB-01 (ATCC 33608) and Pseudomonas fluorescens NCNM PFB-01 (ATCC 25323), respectively, and phytopathogenic strains of Xanthomonas campestris NCNM BX-01 (ATCC 53196), Erwinia amylovora NCNM BE-01 (ATCC 29780), E. carotovora NCNM BE-03 (ATCC 15713), as well on the fungi strains of Candida utilis NCNM Y-22 (ATCC 44638) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae NCNM Y-20 (ATCC 4117).

Before the evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of the compounds 1 and 2 the microbial cell viability assessment was done on the used microorganisms. Moreover, this assessment is performed periodically and mandatory in the process of maintaining the microorganisms in the collection.

For testing the double successive dilution method was used as reported before [43]. For this, at the initial stage, 1 mL of peptone broth for test bacteria and Sabouraud broth for test fungi was introduced into a series of 10 tubes. Subsequently, 1 mL of the analyzed preparation was dropped into the first test tube. Then, the obtained mixture was pipetted, and 1 mL of it was transferred to the next tube, so the procedure was repeated until tube no. 10 of the series. Thus, the concentration of the initial preparation decreased 2-fold in each subsequent tube. At the same time, 24 h test microorganisms cultures were prepared. Initially, suspensions of test microorganisms were prepared with optical densities (O.D.) of 2.0 for tested bacteria and 7.0 for fungi according to the McFarland index. Subsequently, 1 mL of the obtained microbial suspension was dropped in a tube containing 9 mL of sterile distilled water. The content of the tube was mixed, and 1 mL of the mixture was transferred to tube no. 2 of the 5-tube series containing 9 mL of sterile distilled water. From the 5-th tubes of the series, 0.1 mL of the microbial suspension was taken, which represent the seeded dose and added to each tube with titrated preparation. Subsequently, the tubes with titrated preparation and the seeded doses of the microorganisms were kept in the thermostat at 35 °C for 24 h. On the second day, a preliminary analysis of the results was made. The last tube from the series in which no visible growth of microorganisms has been detected is considered to be the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the preparation. For the estimation of the minimal bactericidal and fungicidal concentrations, the contents of the test tubes with MIC and with higher concentrations are seeded on peptone and Sabouraud agar from Petri dishes with the use of the bacteriological loop. The seeded dishes are kept in the thermostat at 35 °C for 24 h. The concentration of preparation, which does not allow the growth of any colony of microorganisms, is considered to be the minimal bactericidal and fungicidal concentrations of the preparation.

2.5. Crystallographic studies

Determination of the unit cell parameters and processing of experimental data were performed using the CrysAlis Oxford Diffraction Ltd. (CrysAlis RED, O.D.L. Version 1.171.34.76. 2003). The structures were solved by direct methods and refined by full-matrix least-squares on weighted F2 values for all reflections using the SHELXL2014 suite of programs [44]. All non-H atoms in the compounds were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. The positions of hydrogen atoms in the structures were located on difference Fourier maps or calculated geometrically and refined isotropically in the “rigid body” model with U = 1.2Ueq or 1.5Ueq of corresponding O, N, and C atoms. Crystallographic data and structure refinements are summarized in Table S1, and the details of the hydrogen bonding interactions are given in Table S2. CCDC 2051228 and 2051229 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12, Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

3. Results and discussion

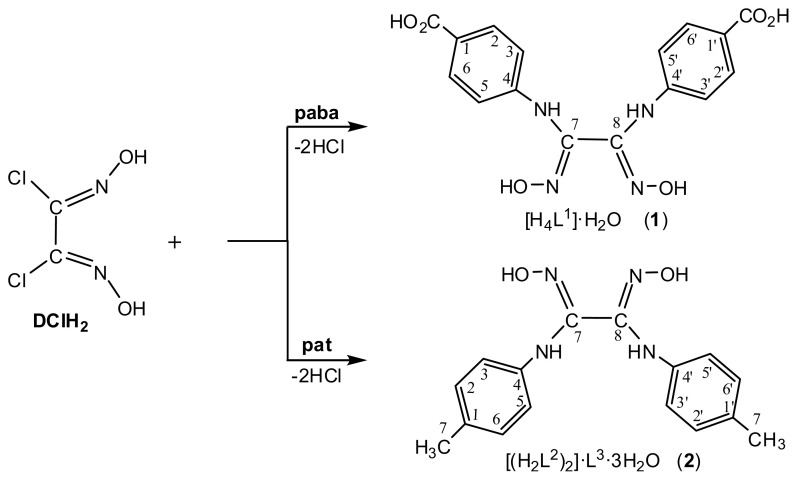

The syntheses of target compounds were performed by interaction of dichloroglyoxime (DClH2) with p-aminobenzoic acid (paba) and p-aminotoluene (pat), in 1:2 molar ratio, in methanol and ethanol, respectively, according to Scheme. The new vic-dioxime bis(p-aminobenzoic acid)-glyoxime hydrate (H4L1·H2O, 1) and bis(di-p-aminotoluene)-glyoxime mono-p-aminotoluene trihydrate ((H2L2)2·pat·3H2O, 2) were obtained in 56% and 53% yields, and their structures were confirmed by spectral IR, 1H, 13C and 15N NMR analyses and single crystal X-ray diffraction.

Scheme.

Synthesis of vic-dioximes 1 and 2.

3.1. FT IR and UV-Vis spectroscopy

The region 3800–2400 cm−1 from the IR spectrum of compound 1 is the most informative and shows multiple strong absorption bands. The absorption maximum from 3535 cm−1 may be attributed to the ν(OH)H2O vibration with the formation of hydrogen bonds [45], and narrow band from 3361 cm−1 as the first overtone of the ν(C=O) group vibration [46]. The presence of oximic OH group is confirmed by a large peak at 3180 cm−1, which is typical also for ν(NH), the value and the width of which proves the association of both mentioned groups by hydrogen bonds [45,47]. Also, the signal from 1626 cm−1 belongs to the δ(NH) vibrations of amino group.

A series of middle intensity absorption bands (in the range 3100–2700 cm−1) may be attributed to the ν(CH) vibrations of the aromatic rings, and their intensity higher than usual is caused by the relatively large number of aromatic rings in the complex [45]. The ν(C=C) vibrations at 1600, 1519 and 1459 cm−1, but also δ(CH)nonpl. oscillation from 854 cm−1 represents 1,4-substituted aromatic rings (two neighboring hydrogen atoms) [45,48].

The spectrum of compounds 2 has many similarities with that of compound 1, but it has also some differences related to the absence of the carboxylic group and presence of –CH3 group from oxime and –NH2 group from molecule of p-aminotoluene, which co-crystallizes with oxime molecule. The main vibrations characteristic for amino group νas(NH2) and νs(NH2) are visible at 3371 and 3308 cm−1, respectively, and that of δ(NH2) is present at 1614 cm−1. The signals of the aliphatic groups (–CH3) are located in the range of 3000–2700 cm−1, as well as those for δas(CH3) and δs(CH3) at 1466 and 1380 cm−1, respectively. The IR spectrum of compound 2 contains some strong absorption bands specific for dimeric carboxylic acids whose –OH groups form hydrogen bonds of O-H…O type at 2672 and 2531 cm−1 [43]. The peak of ν(C=O) groups is well seen at 1677 cm−1, this of ν(C-O)+δ(OH)plan. groups at 1421 cm−1 and δ(OH)nonpl. from dimer at 898 cm−1. The signal of ν(C=N)oxime is visible at 1652 cm−1 [44]. The vibration from 812 cm−1 proves the presence of 1,4-substituted aromatic rings (two neighboring hydrogen atoms) [45].

In the UV-Vis spectra of dioximes 1 and 2, acquired in methanol, two pairs of absorption maximums are observed at 225 and 230 nm, 295 and 340 nm, respectively. First peaks can be assigned to π→π* type transactions in benzene ring (C=C bonds) and to azomethine groups (-C=N) from the oximic unit (Figure 1) [49]. The second pair of peaks represent n→π* type transactions characteristic for iminic groups (-C=N:-) and carbonyl groups (-C=O:) [49, 50].

Figure 1.

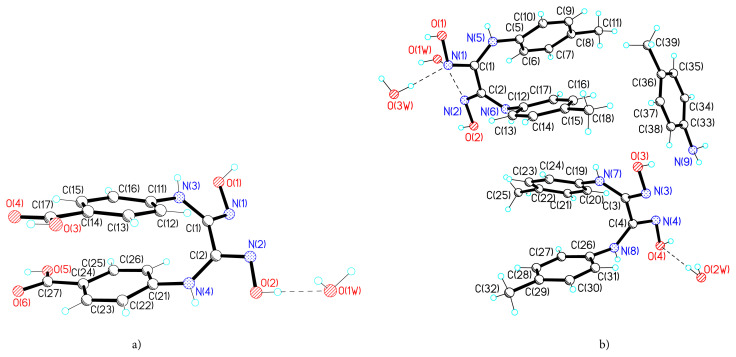

Molecular structure of compounds 1 (a) and 2 (b).

3.2. NMR characterization

The NMR analysis fully confirmed the structure of compounds 1 and 2. Thus, the doublets from 6.82 and 7.66 ppm belong to unsubstituted protons from aromatic rings of ligand 1. The protons from NH groups appeared at 8.75 ppm and those from oximic groups at 10.92 ppm, all as large singlets. The tertiary carbon atoms from aromatic rings were registered at 117.92 and 130.45 ppm, quaternary at 123.19 and 144.55 ppm. The signal of carbons from carboxylic and oximic groups is localized at 142.32 and 167.60 ppm.

According to NMR data, the unsubstituted aromatic protons from the molecule of compound 2 are visible at 6.67 and 6.88 ppm. The protons of methyl groups appear at 2.15 ppm and those from NH groups at 8.43 ppm, all as singlets. The protons from oximic groups were registered as large singlet at 10.36 ppm. The tertiary carbons from aromatic rings were registered at 119.77 and 129.26 ppm, while quaternary at 131.05 and 143.56 ppm. The signals from 137.43 ppm belong s to oximic carbon atoms.

The 15N NMR spectra of compounds 1 and 2 contain the signals of aminic N atoms at 100.9 ppm and 97.1 ppm, respectively.

3.3. Single crystal structures

The recent literature review in CSD [51] revealed that only two polymorphs of dianylineglyoxime salts as uncoordinated dioxime with “aromatic wings” are known [17]. We reported new di-aminobenzoylglioxime compounds 1 and 2 with substituents –COOH and –CH3 in para-positions crystallized in centrosymmetric C2/c (1) and uncentered Pn (2) monoclinic space groups (Table S1).

In the asymmetrical part of the unit cell of the crystal 1 a molecule of H4L1 and water were detected, and in that of crystal 2 - two molecules of H2L2, one crystallization molecule of 4-methylaniline (p-toluidine) L3 and three molecules of water, as a result their formulas, can be described as H4L1·H2O and (H2L2)2·L3·3H2O (Figures 1a and 1b). It should be mentioned, that the title compounds were never reported before. A careful search in CSD showed a Fe(II) complex with ligand, which contains two fragments of methylated dianylineglyoxime being united by three BF2+ moieties [25,52]. In CSD there are nine cases when p-aminotoluene crystallizes with diverse molecules, inclusive derivatives of 4-nitrophthalic acid or of 3,3′-(pentane-1,5-diylbis(oxy))-bis-(5-methoxybenzoic) acid with pat [53, 54].

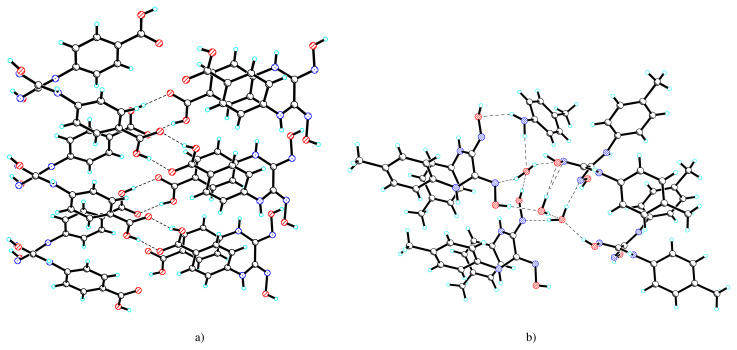

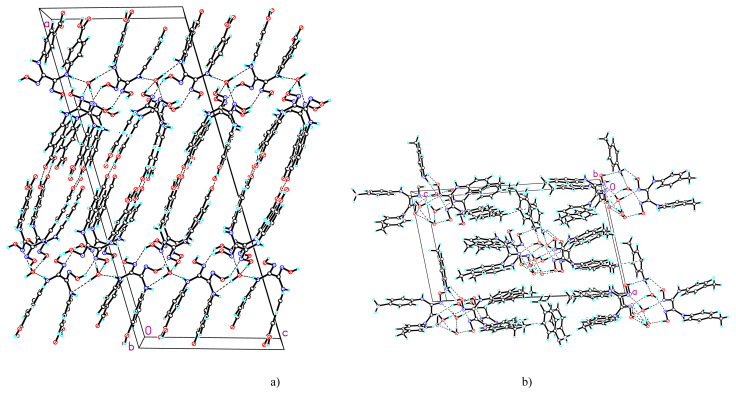

Due the fact that these neutral molecules possess both proton donor groups and acceptor atoms, in respective crystals, the components are connected by complicated system of hydrogen bonds (Table S2). In the crystal of compound 1 can be highlighted chains parallel with plane b, formed by synthons R(8)22 via –COOH groups of neighboring H2L (Figure 2a), which further develops into a 3D network via oximic groups and water molecules (Figure 3a).

Figure 2.

Fragment of chains in 1 (a) and view of H-bonded components in 2 (b).

Figure 3.

Fragments of crystal packing in 1 (a) and 2 (b) along b.

In the crystal of compound 2 three water molecules unite four molecules of H2L2 and one of pat (Figure 2b), which further develops in parallel chains with a, united via fine C-H...X bonds, where X is the center of the aromatic ring from molecule pat (C...X 3.625, H...X 3.087 Å) (Figure 3b).

3.4. Antimicrobial activity

A detailed literature search in the field of biological activity of vic-dioximes offered a few related bibliographic references. In one of them, the authors reported that, in contrast to its metal CuII, NiII, ZnII, CdII complexes, vic-dixime ligand bearing one naphthyl disodium disulfonate unite has no inhibitory effects on the growth of Rhodotorula rubra, Kluyveromyces marxianus, Aspergillus fumigatus and Mucor pusillus fungi strains [41].

Another research group performed an in vitro assessments of some 3- and 4-substituted benzaldehyde hydrazones vic-ligands and their CuII, NiII, CoII complexes on 18 strains of bacteria and yeasts [55]. The authors mentioned that all the tested compounds exhibit moderate antimicrobial activities, the ligands being generally more active. Here must be mentioned mono-3-methylbenzaldehyde hydrazone vic-dioxime, followed by mono-4-methoxybenzaldehyde hydrazone vic-dioxime. These ligands have shown slightly higher activities against Bacillus thrungiensis and strong activity against Candida utilis, C. albicans, C. glabata, C. trophicalis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae compared to the reference compounds.

A comparative study of the antibacterial activity of two vic-dioxime ligands containing one p-tolyl and benzyl-piperazinyl, and bis-benzyl-piperazinyl radicals and their NiII, CuII, CoII, ZnII metal complexes was performed by authors [56]. According to them only ligand bearing bis-benzyl-piperazinyl units have shown weak antibacterial activity.

The in vitro growth inhibitory activity of the vic-dioxime [H4L1]·H2O 1 and [H2L2]·pat·3H2O 2 ligands was assessed against both nonpathogenic gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas fluorescens), phytopathogenic (Xanthomonas campestris, Erwinia amylovora, E. carotovora) and the fungi (Candida utilis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (Table).

Table.

In vitro antifungal and antibacterial activities of compound 1 and 2.

| MBC and MFC, mg/mL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | Bacillus subtilis | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Erwinia amylovora | Erwinia carotovora | Xanthomonas campestris | Candida Utilis | Saccharomuces cerevisiae |

| 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | 70 | 150 | 70 | 150 | 150 | 70 | 150 |

MBC – minimal bactericidal concentration;

MFC - minimal fungicidal concentration;

N/A – non active

Compound 2 exhibits average antibacterial and antifungal properties in the range of concentrations of 70–150 μg/mL for bacteria and fungi. In contrast to other vic-dioxime ligands that do not show antibacterial and antifungal activity compared to their metal complexes [41, 57], we managed to obtain reported ligands in crystalline form and in higher yields using simple but efficient methods of synthesis. Looking to the data presented in Table, it is well seen that compound 2 exhibits variable biological activity depending on the bacterial or fungicidal species. A possible cause of this variation could be the different permeability of the cells of the microorganism or the difference between the ribosomes of the microbial cells [58–61]. In order to avoid speculation about the influence of the co-crystallized p-aminotoluene molecule on the activity of compound 2, a separate evaluation was performed on said bacterial and fungal strains. According to this, p-aminotoluene did not show antimicrobial activity.

A probable explanation of the different activity of compound 1 and 2 may be the presence of different substituents in the benzene ring, otherwise their structure being identical. The inactivity of compound 1 may be due to the presence of the carboxyl group in the para-position of the benzene ring, make this compound highly hydrophilic and, consequently, decrease the cell membrane penetration. In the case of compound 2, the situation is different; the presence of the methyl group in the para-position of the benzene ring increase the lipophilic nature of this compound, and consequently increase its cell membrane penetration capacity.

4. Conclusion

As result of this research bis(p-aminobenzoic acid)-glyoxime hydrate and bis(di-p-aminotoluene)glyoxime mono-p-aminotoluene trihydrate were synthetized and fully characterized, including by single crystal X-ray diffraction. The last reported compound showed good antimicrobial activity against five species of gram-positive, gram-negative, phytopatogenic bacteria, and two strains of fungi. The reported data are a good contribution to the chemistry of vic-dioximes, and the compounds obtained are promising ligands for the synthesis of metal complexes.

Table S1.

Crystal data and structure refinement for compounds 1 and 2.

| 1 | 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Formula | C16H16N4O7 | C39H51N9O7 |

| Mr | 376.33 | 757.89 |

| Cryst. system | monoclinic | monoclinic |

| Space group | C2/c | Pn |

| а / Å | 35.338(2) | 13.863(2) |

| b / Å | 6.8836(4) | 6.4122(14) |

| с / Å | 14.3090(9) | 23.213(5) |

| b / ° | 106.419(7) | 99.512(18) |

| V, Å3 | 3338.7(4) | 2035.1(7) |

| Z | 8 | 2 |

| Dcalcd / g/c | 1.497 | 1.237 |

| μ / mm−1 | 0.120 | 0.087 |

| F(000) | 1568 | 808 |

| Crystal size / mm3 | 0.40 x 0.08 x 0.04 | 0.50 x 0.06 x 0.04 |

| Reflections collected / independent reflections | 5258/2938 (Rint = 0.0312) | 7811/5837 (Rint = 0.0682) |

| Completeness to theta / % (θ = 25.05) | 99.3 | 99.8 |

| Parameters | 244 | 510 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.004 | 1.007 |

| final R1, wR2 | R1 = 0.0522, wR2 = 0.1174 | R1 = 0.0737, wR2 = 0.1349 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = = 0.0890, wR2 = 0.1315 | R1 = 0.2073, wR2 = 0.1988 |

| Largest diff. peak and hole, e×Å−3 | 0.263, −0.292 | 0.233, −0.214 |

Table S2.

Hydrogen bond distances (Å) and angles (°) in molecules 1 and 2.

| D–H···A | d(H···A) | d(D···A) | Đ(DHA) | Symmetry transformations for A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||

| O(1)–H(1)⋯O(2) | 2.65 | 3.449(3) | 166 | −x+1/2, y+1/2, −z+3/2 |

| O(1)–H(1)⋯N(2) | 2.03 | 2.746(3) | 145 | −x+1/2, y+1/2, −z+3/2 |

| O(2)–H(2)⋯O(1W) | 1.99 | 2.809(2) | 175 | x, y, z |

| O(3)–H(3)⋯O(6) | 1.82 | 2.624(2) | 165 | −x, y−1, −z+1/2 |

| O(5)–H(5)⋯O(4) | 1.78 | 2.593(2) | 169 | −x, y+1, −z+1/2 |

| N(4)–H(4)⋯O(1W) | 2.18 | 3.031(3) | 169 | −x+1/2, −y+1/2, −z+1 |

| O(1W)–H(1)⋯N(1) | 1.93 | 2.824(3) | 171 | x, y−1, z |

| O(1W)–H(2)⋯N(3) | 2.42 | 3.405(3) | 170 | −x+1/2, y−1/2, −z+3/2 |

| 2 | ||||

| N(9)–H(9A)⋯O(1W) | 2.19 | 3.14(1) | 178 | x+1/2, −y, z−1/2 |

| N(9)–H(9B)⋯O(1) | 2.52 | 3.18(2) | 132 | x+1/2, −y, z−1/2 |

| O(1)–H(1)⋯O(1W) | 1.83 | 2.64(1) | 172 | x, y+1, z |

| O(2)–H(2)⋯O(2W) | 1.90 | 3.70(1) | 176 | x−1/2, −y, z+1/2 |

| O(3)–H(3)⋯N(9) | 1.93 | 2.72(1) | 162 | x, y+1, z |

| O(4)–H(4)⋯O(3W) | 1.83 | 3.64(1) | 170 | x+1/2, −y, z−1/2 |

| O(1W)–H(1)⋯N(2) | 2.09 | 2.82(1) | 149 | x, y, z |

| O(1W)–H(2)⋯N(4) | 2.10 | 2.86(1) | 156 | x+1/2, −y+1, z−1/2 |

| O(2W)–H(1)⋯O(2W) | 2.00 | 2.88(1) | 178 | x, y, z |

| O(2W)–H(2)⋯O(4) | 2.09 | 2.97(2) | 179 | x, y, z |

| O(2W)–H(2)⋯N(4) | 2.60 | 3.37(1) | 147 | x, y, z |

| O(3W)–H(1)⋯N(1) | 1.96 | 2.83(1) | 177 | x, y, z |

| O(3W)–H(2)⋯N(3) | 1.94 | 3.82(1) | 160 | x−1/2, −y+1, z+1/2 |

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by State Programs of National Agency for Research and Development R. Moldova 20.80009.5007.28. and 20.80009.5007.15.

LL is grateful to National Collection of Non-Pathogenic Microorganisms (NCNM) of the Institute of Microbiology and Biotechnology.

References

- 1. Kanno H, Yamamoto H. Production method of organic solvent solution of dichloroglyoxime. 0.636.605A1. EP. 1994

- 2. Banks CV. The chemistry of vic-dioximes. Record of Chemical Progress. 1964;25:85–103. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh RB, Garg BS, Singh RP. Oximes as spectrophotometric reagents – a review. Talanta. 1979;26(6):425–444. doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(79)80107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Serin S. New vic-dioxime transition metal complexes. Transition Metal Chemistry. 2001;26:300–306. doi: 10.1023/A:1007163418687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schrauzer GN, Windgassen RJ, Kohnle J. Die Konstitution von Vitamin B12s. Chemische Berichte. 1965;98(10):3324–3333. doi: 10.1002/cber.19650981032. (in German) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chakravorty A. Structural chemistry of transitional metal complexes of oximes. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 1974;13(1):1–46. doi: 10.1016/S0010-8545(00)80250-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lance KA, Dzugan S, Busch DH, Alcock NW. The synthesis, characterızatıon and dıoxygen affınıty of pıllared cobalt complexes derıved from the glyoxımato lıgand famıly. Gazzetta Chimica Italiana. 1996;126(4):251–258. SICI-code: 0016-5603(1996)126:4. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boyer JH. Increasing the index of covalent oxygen bonding at nitrogen attached to carbon. Chemical Reviews. 1980;80:495–561. doi: 10.1021/cr60328a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schrauzer GN, Kohnle J. Coenzym B12-Modelle. Chemische Berichte. 1964;97(11):3056–3064. doi: 10.1002/cber.19640971114. (in German) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tschugaeff L. Über eine neue synthese der α-diketone. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 1907;40(1):186–187. doi: 10.1002/cber.19070400127. (in German) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Canpolat E, Kaya M. Synthesis and formation of a new vic-dioxime complexes. Journal of Coordination Chemistry. 2005;58(14):1217–1224. doi: 10.1080/00958970500130501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kukushkin VY, Pombeiro AJL. Oxime and oximate metal complexes: unconventional synthesis and reactivity. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 1999;181(1):147–175. doi: 10.1016/s0010-8545(98)00215-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Forster MO. LVIII.—Studies in the camphane series. Part XI. The dioximes of camphorquinone and other derivatives of isonitrosocamphor. Journal of the Chemical Society, Transaction. 1903;83(9):514–536. doi: 10.1039/ct9038300514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Canpolat E, Kaya M. Synthesis, characterization of some Co(III) complexes with vic-dioxime ligands and their antimicrobial properties. Turkish Journal of Chemistry. 2004;28(2):235–242. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen X-Y, Cheng P, Liu X-W, Yan S-P, Bu W-M, et al. Binuclear and tetranuclear copper(II) complexes bridget by dimethylglyoxime. ChemistryLetters. 2003;32(2):118–119. doi: 10.1246/cl.2003.118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simonov YA, Malinovskii ST, Bologa OA, Zavodnik VE, Andrianov VI, et al. Crystalline and molecular structure of μ-Oxo-di (bis-dimethylglyoxymethocobalt (III)) Crystallography. 1993;28:682–684. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ureche D, Bulhac I, Rija A, Coropceanu E, Bourosh P. Dianilineglyoxime salt and its binuclear Zn(II) and Mn(II) complexes with 1,3-benzenedicarboxylic acid: synthesis and structures. Russian Journal Coordination Chemistry. 2019;45(2):843–855. doi: 10.1134/S107032841912008X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bourosh P, Bulhac I, Simonov Yu A, Gdaniec M, Turta K, et al. Structure of the products formed in the reaction of cobalt chloride with 1,2-cyclohexanedione dioxime. Russian Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2006;51(8):1202–1210. doi: 10.1134/S0036023606080092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Takamura T, Harada T, Furuta T, Ikariya T, Kuwata S. Half-sandwich iridium complexes bearing a diprotic glyoxime ligand: Structural diversity induced by reversible deprotonation. Chemistry an Asian Journal. 2020;15(1):72–78. doi: 10.1002/asia.201901276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bourosh P, Bologa O, Deseatnic-Ciloci A, Tiurina J, Bulhac I. Synthesis, structure, and biological properties of mixed cobalt(III) dioximates with quinidine derivatives. Russian Journal Coordination Chemistry. 2017;43(9):591–599. doi: 10.1134/S1070328417090019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Coropceanu E, Bologa O, Arsene I, Vitiu A, Bulhac I, et al. Synthesis and characterization of inner-sphere substitution products in azide-containing cobalt(III) dioximates. Russian Journal Coordination Chemistry. 2016;42(8):516–538. doi: 10.1134/S1070328416070046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bulhac I, Bouros PN, Bologa OA, Lozan V, Ciobanic O, et al. Specific features of the structures of iron(II) α-benzyl dioxymate solvates with pyridine. Russian Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2010;55(7):1042–1051. doi: 10.1134/S0036023610070090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Galinkina J, Wagner C, Rusanov E, Merzweiler K, Schmidt H, et al. Synthesis und charakterisierung von 2-O-punktionalisierten ethylrhodoximen und – cobaloximen. Journal of Inorganic and General Chemistry. 2002;628(11):2375–2382. doi: 10.1002/1521-3749(200211)628:11<2375::AID-ZAAC2375>3.0.CO;2-Qn. (in German) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coşkan A, Karapinar E. Synthesis of N-(4′-Benzo-[15-crown-5]) thiophenoxyphenylaminoglyoxime and its complexes with some transition metals. Journal of Inclusion Phenomena Macrocyclic Chemistry. 2008;60(1–2):59–64. doi: 10.1007/s10847-007-9352-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Belov AS, Prikhod’ko AI, Novikov VV, Vologzhanina AV, Bubnov YN, et al. First “Click” synthesis of the ribbed-functionalized metal clathrochelates: cycloaddition of benzyl azide to propargylamine iron(II) macrobicycle and the unexpected transformations of the resulting cage complex. European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2012;2012(28):4507–4514. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201200628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jansen JC, Verhage M, van Koningsveld H. The molecular structure of bis(N-methylimidazole)-bis(diphenylboron-dimethylglyoximato)iron(II) FeC40N8O4B2H442CCl2H2. Crystal Structure Communications. 1982;11(1):305–308. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fedder W, von Schnering HG, Umland F. Über die struktur von bis- dihydroxoboroxalendiamid-dioximato)-nickel(II) – tetrahydrat. Journal of Inorganic and General Chemistry. 1971;382(2):123–134. doi: 10.1002/zaac.19713820204. (in German) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yari A, Kakanejadifard A. Spectrophotometric and theoretical studies on complexation of a newly synthesized vic-dioxime derivative with nickel(II) in dimethylformamide. Journal of Coordination Chemistry. 2007;60(10):1121–1132. doi: 10.1080/00958970601110469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chertanova LF, Yanovskii AI, Struchkov Yu T, Sopin VF, Rakitin OA, et al. X-Ray structural investigation of glyoxime derivatives. I. Molecular and crystal structure of amino- and diaminoglyoximes. Journal Structural Chemistry. 1989;30(1):129–133. doi: 10.1007/BF00748195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kakanejadifard A, Amani V. (2Z, 3Z)-3,4-Dihydro-2H-1,4-benzothiazine-2,3-dione dioxime dehydrate. Acta Crystallographica Section E. 2008;E64(8):o1628. doi: 10.1107/S1600536808023301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kakanejadifard A, Sharifi A, Delfani F, Ranjbar B, Hossein N. Synthesis of di and tetraoximes from the reaction of phenylendiamines with dichloroglyoxime. Iranian Journal of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering. 2007;26(4):63–67. doi: 10.30492/IJCCE.2007.7602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Endres H, Schendzielorz M. Basic behovior of oxamide dioxime: structures of di(oxamide dioximium) squarate, 2C2H7N4O2+·C4O42− (I), and of axamide dioximium di(hydrogen squarate), C2H8N4O22+·2C4HO4− (II) Acta Crystallographica Section C. 1984;c40(3):453–456. doi: 10.1107/S0108270184004492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yuksel F, Gürek AG, Durmuş M, Gurol I, Ahsen V, et al. New insight in coordonation of vic-dioximes: Bis- and tris(E,E-dioximato)Ni(II) complexes. Inorganica Chimica Acta. 2008;361:2225–2235. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2007.11.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kilic A, Tas E, Yilmaz I. Synthesis, spectroscopic and redox properties of the mononuclear NII, NII(BPh2)2 containing (B-C) bond and trinuclear CII-NiII-CuII type-metal complexes of N,N′-4-amino-1-benzyl piperidine)-glyoxime. Journal of Chemical Sciences. 2009;121(1):43–56. doi: 10.1007/s12039-009-0005-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gurol I, Gumus G, Yuksel F, Jeanneau E, Ahsen V. Bis[N,N′-bis(octylsulfanyl)glyoximato]nickel(II) Acta Crystallographica Section E. 2006;E62:m3303–3305. doi: 10.1107/S1600536806046605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Coburn MD. Picrylamino-substituted heterocycles. II. Furazans(1,2) Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry. 1968;5(1):83–87. doi: 10.1002/jhet.5570050114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kakanejadifard A, Khajehkolaki A, Ranibar B, Hossein NM. Synthesis of new dioximes and tetraoximes from reaction of aminothiophenoles with dichloroglyoxime. Asian Journal of Chemistry. 2008;20(4):2937–2946. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grundmann C, Mini V, Dean JM, Frommeld H-D. Über nitriloxyde, IV. Dicyan-di-N-oxyd. Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 1965;687(1):191–214. doi: 10.1002/jlac.19656870119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rija A, Bulhac I, Coropceanu E, Gorincioi E, Calmîc E, et al. Synthesis and spectroscopic study of some coordinative compounds of Co(III), Ni(II) and Cu(II) with dianiline- and disulfanilamideglyoxime. Chemistry Journal of Moldova. 2011;6(2):73–78. doi: 10.19261/cjm.2020.795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Babahan İ, Anil H, Sarikavakli N. Synthesis of novel tetraoxime derivative with hydrazine side groups and its metal complexes. Turkish Journal of Chemistry. 2011;35(4):613–624. doi: 10.19261/cjm.2020.795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kurtoğlu M, İspir E, Kurtoğlu N, Serin S. Novel vic-dioximes: Synthesis, complexation with transition metal ions, spectral studies and biological activity. Dyes and Pigments. 2008;77(1):75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2007.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roppoport Z, Liebman JF. Oximes and Hydroxamic Acids. England: Wiley; 2009. The chemistry of Hydroxylamines. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ciocarlan A, Dragalin I, Aricu A, Lupascu L, Ciocarlan N, et al. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the Levisticum officinale W.D.J. Koch essential oil. Chemistry Journal of Moldova. 2018;13(2):63–68. doi: 10.19261/cjm.2018.514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sheldrick GM. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallographica Section C. 2015;C71(1):3–8. doi: 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bellamy LJ. Infrared spectra of complex molecules. New York, USA: Wiley; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarasevich BN. Reference materials. Moscow, Russia: Izdatel’stvo inostrannoi literaturi; 2012. IR spectra of the main classes of organic compounds. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gordon AJ, Ford RA. The chemist’s companion A handbook of practical data, techniques and references. New York-London-Sydney-Toronto: Wiley Interscience; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakanishi K. Infrared absorption spectroscopy. Tokyo, Japan: Holden Day; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kilic A, Tas E, Gumgum B, Yilmaz I. Synthesis, spectral characterization and electrochemical properties of new vic-dioxime complexes bearing carboxylate. Transition Metal Chemistry. 2006;31(5):645–652. doi: 10.1007/s11243-006-0043-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fraser C, Bosnich B. Bimetallic reactivity. Investigation of metal-metal interaction in complexes of a chiral macrocyclic binucleating ligand bearing 6- and 4-coordinate sites. Inorganic Chemistry. 1994;33(2):338–346. doi: 10.1021/ic00080a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Allen FH. The Cambridge Structural Database: a quarter of a million crystal structures and rising. Acta Crystographica Section B. 2002;B58(3):380–388. doi: 10.1107/S0108768102003890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Varzatskii OA, Voloshin YZ, Korobko SV, Shulga SV, Kramer R, et al. On a way to new types of the polyfunctional and polytopic systems based on cage metal complexes: cadmium-promoted nucleophilic substitution with low-active nucleophilic agents. Polyhedron. 2009;28(16):3431–3438. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2009.07.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Colaço M, Dubois J, Wouters J. Mechanochemical synthesis of phthalimides with crystal structures of intermediates and products. Crystal Engineering Communications. 2015;17(12):2523–2528. doi: 10.1039/C5CE00038F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kohmoto S, Kuroda Y, Kishikawa K, Masu H, Azumaya I. Generation of square-shaped cyclic dimers vs zigzag hydrogen-bonding networks and pseudoconformational polymorphism of tethered benzoic acids. Crystal Growth & Design. 2009;9(12):5017–5020. doi: 10.1021/cg901244v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Babahan I, Poyrazoğlu Çoban E, Özmen A, Biyik H, Isman B. Synthesis, characterization and biological activity of vic-dioxime derivatives containing benzaldehydehydrazone groups and their metal complexes. African Journal of Microbiology Research. 2011;5(3):271–283. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bilge T, Uğur A. Preparation and spectral and biological investigation of vic-dioxime ligands containing piperazine moiety and their mononuclear transition-metal complexes. Synthetic Communications. 2013;43(24):3307–3314. doi: 10.1080/00397911.2013.777743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Uğur A, Mercimek B, Özler MA, Şahin N. Antimicrobial effects of bis(Δ2-2-imidazolinyl)-5,5′-dioxime and its mono- and tri-nuclear complexes. Transition Metal Chemistry. 2000;25(4):421–425. doi:org/10.1023/A:1007064819271 . [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kurtoğlu M, Dagdelen MM, Toroğlu S. Synthesis and biological activity of novel (E,E)-vic-dioximes. Transition Metal Chemistry. 2006;31(3):382–388. doi: 10.1007/s11243-006-0006-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sengupta SK, Pandey OP, Srivastava BK, Sharma VK. Synthesis, structural and biochemical aspects of titanocene and zirconocene chelates of acetylferrocenyl thiosemicarbazones. Transition Metal Chemistry. 1998;23(4):349–353. doi:org/10.1023/A:1006986131435 . [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kurtoğlu M, Baydemir SA. Studies on mononuclear transition metal chelates derived from a novel (E,E)-dioxime: synthesis, characterization and biological activity. Journal of Coordination Chemistry. 2007;60(6):655–665. doi: 10.1080/00958970600896076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. İspir E, Kurtoğlu M, Toroğlu S. The d10 metal chelates derived from schiff base ligands having silane: synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial studies of cadmium(II) and zinc(II) complexes. Synthesis and Reactivity in Inorganic, Metal-Organic and Nano-Metal Chemistry. 2006;36(8):627–631. doi:org/10.1080/15533170600910553 . [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Crystal data and structure refinement for compounds 1 and 2.

| 1 | 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Formula | C16H16N4O7 | C39H51N9O7 |

| Mr | 376.33 | 757.89 |

| Cryst. system | monoclinic | monoclinic |

| Space group | C2/c | Pn |

| а / Å | 35.338(2) | 13.863(2) |

| b / Å | 6.8836(4) | 6.4122(14) |

| с / Å | 14.3090(9) | 23.213(5) |

| b / ° | 106.419(7) | 99.512(18) |

| V, Å3 | 3338.7(4) | 2035.1(7) |

| Z | 8 | 2 |

| Dcalcd / g/c | 1.497 | 1.237 |

| μ / mm−1 | 0.120 | 0.087 |

| F(000) | 1568 | 808 |

| Crystal size / mm3 | 0.40 x 0.08 x 0.04 | 0.50 x 0.06 x 0.04 |

| Reflections collected / independent reflections | 5258/2938 (Rint = 0.0312) | 7811/5837 (Rint = 0.0682) |

| Completeness to theta / % (θ = 25.05) | 99.3 | 99.8 |

| Parameters | 244 | 510 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.004 | 1.007 |

| final R1, wR2 | R1 = 0.0522, wR2 = 0.1174 | R1 = 0.0737, wR2 = 0.1349 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = = 0.0890, wR2 = 0.1315 | R1 = 0.2073, wR2 = 0.1988 |

| Largest diff. peak and hole, e×Å−3 | 0.263, −0.292 | 0.233, −0.214 |

Table S2.

Hydrogen bond distances (Å) and angles (°) in molecules 1 and 2.

| D–H···A | d(H···A) | d(D···A) | Đ(DHA) | Symmetry transformations for A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||

| O(1)–H(1)⋯O(2) | 2.65 | 3.449(3) | 166 | −x+1/2, y+1/2, −z+3/2 |

| O(1)–H(1)⋯N(2) | 2.03 | 2.746(3) | 145 | −x+1/2, y+1/2, −z+3/2 |

| O(2)–H(2)⋯O(1W) | 1.99 | 2.809(2) | 175 | x, y, z |

| O(3)–H(3)⋯O(6) | 1.82 | 2.624(2) | 165 | −x, y−1, −z+1/2 |

| O(5)–H(5)⋯O(4) | 1.78 | 2.593(2) | 169 | −x, y+1, −z+1/2 |

| N(4)–H(4)⋯O(1W) | 2.18 | 3.031(3) | 169 | −x+1/2, −y+1/2, −z+1 |

| O(1W)–H(1)⋯N(1) | 1.93 | 2.824(3) | 171 | x, y−1, z |

| O(1W)–H(2)⋯N(3) | 2.42 | 3.405(3) | 170 | −x+1/2, y−1/2, −z+3/2 |

| 2 | ||||

| N(9)–H(9A)⋯O(1W) | 2.19 | 3.14(1) | 178 | x+1/2, −y, z−1/2 |

| N(9)–H(9B)⋯O(1) | 2.52 | 3.18(2) | 132 | x+1/2, −y, z−1/2 |

| O(1)–H(1)⋯O(1W) | 1.83 | 2.64(1) | 172 | x, y+1, z |

| O(2)–H(2)⋯O(2W) | 1.90 | 3.70(1) | 176 | x−1/2, −y, z+1/2 |

| O(3)–H(3)⋯N(9) | 1.93 | 2.72(1) | 162 | x, y+1, z |

| O(4)–H(4)⋯O(3W) | 1.83 | 3.64(1) | 170 | x+1/2, −y, z−1/2 |

| O(1W)–H(1)⋯N(2) | 2.09 | 2.82(1) | 149 | x, y, z |

| O(1W)–H(2)⋯N(4) | 2.10 | 2.86(1) | 156 | x+1/2, −y+1, z−1/2 |

| O(2W)–H(1)⋯O(2W) | 2.00 | 2.88(1) | 178 | x, y, z |

| O(2W)–H(2)⋯O(4) | 2.09 | 2.97(2) | 179 | x, y, z |

| O(2W)–H(2)⋯N(4) | 2.60 | 3.37(1) | 147 | x, y, z |

| O(3W)–H(1)⋯N(1) | 1.96 | 2.83(1) | 177 | x, y, z |

| O(3W)–H(2)⋯N(3) | 1.94 | 3.82(1) | 160 | x−1/2, −y+1, z+1/2 |