SYNOPSIS

Objective.

This study examined the prevalence and correlates of spanking and verbal punishment in a community sample of Latino immigrant families with young children, as well as the association of spanking and verbal punishment with child internalizing and externalizing problems 1 year later. Parenting context (e.g., warmth) and cultural context (e.g., the cultural value of respeto) are considered as potential moderators.

Design.

Parenting and cultural socialization practices were assessed via parent self-report in sample of 633 Mexican and Dominican immigrant families with young children (M age = 4.43 years). Parent and teacher assessments of child internalizing and externalizing were also collected at baseline and 12 months later.

Results.

At Time 1, male child gender was positively correlated with concurrent spanking; familial social support and U.S. American cultural knowledge were negatively correlated with mothers’ spanking. Verbal punishment at Time 1 was associated with externalizing problems at Time 2 among both Mexican and Dominican American children, and this relation was not moderated. Additionally, verbal punishment was associated with Time 2 child internalizing problems among Mexican American children. There were no significant associations between spanking and later child internalizing or externalizing behaviors.

Conclusion.

It is important that researchers examine both physical and verbal discipline strategies to understand their unique influences on Latino child outcomes, as well as contextual influences that may elucidate the use and long-term effects of spanking and verbal punishment on Latino children at different developmental stages.

Keywords: Respeto, discipline, early childhood, Latino families, internalizing, externalizing

INTRODUCTION

Parental warmth and control are two behavioral dimensions central to parenting that are critical for child development (Bornstein & Bornstein, 2014; Maccoby & Martin, 1983). A significant body of work underscores the benefits of parental warmth and emotional responsiveness for child well-being (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000), but there is less agreement regarding the impact of parental control and discipline on child well-being, particularly physical discipline practices such as spanking. Some meta-analyses indicate that spanking is associated with a range of adverse child outcomes (Gershoff, 2002; Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016), but estimates of the effect sizes is debated (Ferguson, 2013; Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005), especially by those using more rigorous methods such as controlling for baseline child problems (Ferguson, 2013). Some studies have found a positive association between spanking and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors (Coley, Kull & Carrano, 2014; Maguire-Jack, Gromoske & Berger, 2012), but the moderated and null findings from other studies suggest that the impact of spanking is not uniform across all children (Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1996; Larzelere & Baumrind, 2010; Lansford et al., 2012; Stacks et al., 2009), thus spurring conversation in the child development literature about whether spanking and other forms of punitive discipline adversely affect all children similarly. Much of this literature has focused on African American families in comparison to European American families, and little is known about these associations in Latino families (but see Coley et al., 2014; German et al., 2013; McLoyd & Smith, 2002, for exceptions). To address this gap, the present study capitalizes on longitudinal data from a large community sample of Latino immigrant families of preschool aged children to better understand parental discipline practices and their relation to child functioning in early childhood.

Theoretical bases for the link between spanking and adverse child outcomes are found in social learning theory (Bandura, 1978) and attachment theory (Ainsworth & Bowlby, 1991; Bretherton, 1992). Social learning theory, for example, suggests that exposure to parental aggression can disinhibit aggressive behavior in children, inculcating aggressive problem-solving scripts and modeling aggression as an acceptable form of behavior. Attachment theory suggests that children develop expectations about self and others via “internal working models” shaped by interactions with primary attachment figures. Thus, children who interpret punitive discipline as a form of rejection may generalize their negative representations of parent-child interactions to themselves, thereby developing less emotional security and greater levels of insecurity and anxiety. Empirical studies, however, indicate that context (e.g., cultural values, parent motivation) may affect the expected association between spanking and adverse child outcomes. As ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and Garcia-Coll et al.’s (1996) integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children highlight, parent-child interactions are influenced by both proximal sources, such as family conditions, to more macro-level sources, such as culture. Indeed, there is some evidence that ethnicity/culture may moderate the association between spanking and child outcomes (Berlin et al., 2009; Berzenski & Yates, 2013; Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1996; Gunnoe & Mariner, 1997; Larzelere & Kuhn, 2005; Slade & Wissow, 2004). According to these scholars, there may be culturally rooted beliefs that shape children’s understanding of spanking as normative and acceptable, buffering some of the negative effect on child well-being (Ispa & Halgunseth, 2004; Lansford et al., 2005). Others emphasize the adaptive nature of spanking in the context of the disadvantaged, dangerous neighborhood conditions in which many ethnic minority parents must rear their children (Simons et al., 2002; Taylor, Hamvas, & Paris, 2011). Finally, some emphasize the moderating role of parental warmth among ethnic groups, finding that spanking is a risk factor only in the absence of a warm and nurturing parent-child relationship (German et al., 2013; McLoyd & Smith, 2002). Guided by the aforementioned literature, and by the recommendation of Halgunseth, Ispa, and Rudy (2006) to consider both psychological and cultural processes involved in the use of parental control within Latino families, this study examines household context, maternal acculturation, parenting context, and child behaviors in understanding the correlates of spanking and verbal punishment as well as their impact on young Latino’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

One out of every four children in the United States is Latino (Child Trends Databank, 2016). Despite being the largest ethnic minority group of children, there is a dearth of literature examining parenting and associated early childhood outcomes among Latino families. Moreover, findings from research on discipline strategies among Latino families in the United States have been mixed (Dumka et al., 2009; Hill et al., 2003), undermining understanding of the association between discipline practices and Latino child well-being. There are studies of Latino parenting practices in relation to child outcomes, but few studies have incorporated cultural values in considering the use and impact of discipline strategies, despite the importance that cultural values play in childrearing (Calzada, Fernandez, & Cortes, 2010; Halgunseth et al., 2006; Harkness, Super, & Keefer, 1992). As a growing body of literature suggests that Latino youth are at elevated risk for internalizing and externalizing behaviors (in large part due to Latino families’ disproportionate exposure to poverty, social inequality, and associated stressors (Calzada, Barajas-Gonzalez, Huang, & Brotman, 2015; Mikolajczyk, Bredehorst, Khelaifat, Maier, & Maxwell, 2007; Pina & Silverman, 2004; Smokowski, Rose, Evans, Cottier, Bower & Bacallao, 2014), a better understanding of which parenting practices may be associated with child internalizing and externalizing problems is critical for informing prevention and early intervention efforts. To this end, the present study describes the use of spanking and verbal punishment in response to misbehavior in a community sample of Latino immigrant mothers of young children; identifies correlates of both spanking and verbal punishment; and tests for associations between spanking and verbal punishment and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors 1 year later.

Spanking, Verbal Punishment, and Child Outcomes

Spanking, defined as “noninjurious, open-handed hitting with the intention of modifying child behavior” (Gershoff & Grogan-Keylor, 2016, p. 453) is not uncommon in the United States, where the majority (80%) of parents of young children report spanking at least once by the time the child is age 10 (Zolotor et al., 2011); with some studies indicating that 45% of parents have spanked their 2- to 5-year-old child in the past month (MacKenzie, Nicklas, Brooks-Gunn & Waldfogel, 2011). Some variation across groups has been found in the acceptability and use of spanking and other forms of corporal punishment; parents of boys and ethnic minority parents tend to endorse spanking more than others (MacKenzie et al., 2011; Straus & Stewart, 1999). In the Latino population, parents have been described as highly controlling (Halgunseth, Ispa, & Rudy, 2006; Rodriguez & Olswang, 2003), and although parental control may be maintained through non-harsh means, high levels of parental control are consistent with the frequent use of spanking (Baumrind, 2012). Indeed, comparative studies describe Latino parents’ reliance on controlling practices and more generally depict Latino parents as authoritarian (Fracasso et al., 1994; Knight et al., 1994). Others, however, argue that although Latino parents are highly demanding with low levels of autonomy granting, their parenting styles are also characterized by high warmth (Domenech Rodriguez, Donovick, & Crowley, 2009). Thus, Latino parents may be highly controlling, but there is also evidence that they are highly nurturing (Calzada & Eyberg, 2002; Calzada et al., 2015; Domenech-Rodriguez, et al., 2009).

In addition to corporal punishment, punitive discipline can include verbal punishment, defined as “scolding, yelling, or derogating” (Berlin et al., 2009, p. 1404). Less attention has been given to the use of verbal punishment, but a similar pattern of findings as is seen with spanking has emerged. In comparison to children who do not experience verbal punishment, those who do experience verbal punishment exhibit higher rates of aggressive and depressive symptoms and lower self-concept (Wang & Kenny, 2014; Yildirim & Roopnarine, 2014). As with spanking, the association between verbal punishment and child outcomes appears to differ by ethnic group. For example, in a sample of Latin American, African American, and European American preschool children, Berzenski and Yates (2013) found that verbal punishment, which included yelling and threatening, but also swearing at the child, was associated with less positive self-concept, but only for children with higher emotion knowledge. Moreover, this interaction was significant only for the non-Latino children in the sample. The authors posited that parental criticism or negativity may not have been associated with negative outcomes for the Latino subsample given the cultural emphases on parental control in Latino families. Qualitative work with Latino mothers suggests that some may indeed view reprimands as a successful means of teaching children to respect and obey their elders (Calzada et al., 2010; Halgunseth & Ispa, 2012), lending credence to the possibility that certain “harsh” practices may not be perceived as such in contexts where cultural values, such as respeto, are strongly endorsed. With its emphasis on obedience and deference to adult wishes (Calzada et al., 2010; Delgado-Gaitan, 1994; Valdes, 1996), respeto is consistent with an authoritarian parenting approach (Calzada et al., 2015; Calzada et al., 2013), but more research is needed to understand how the effects of spanking and verbal punishment may or may not be moderated by cultural values that define such discipline practices as normative.

Correlates of Spanking and Verbal Punishment among Latino Immigrant Parents

Parenting is determined by a confluence of factors, including parents’ maturity, social and psychological resources, child characteristics, socialization goals, and cultural norms and values (Belsky, 1984; Bornstein, 2016; Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Garcia-Coll et al., 1996; Harkness et al., 1992). Belsky’s process model, informed by research on child maltreatment, highlights the importance of parental psychological resources, social support, and parental perceptions of the child in determining parenting. Through this lens, spanking and verbal punishment may be seen as reactive, where parent-centered motivations drive parenting. In contrast, Grusec, Rudy, and Martini (1997) proposed that the conditions promoting parental control differ in individualistic versus collectivistic cultures. As such, in collectivistic cultures, parents are likely to use controlling behaviors in accordance with cultural values rather than in response to psychological strain. Immigrant and ethnic minority parents from collectivist cultures (e.g., Latinos) who live in the United States must therefore “decide which aspects of ethnic parenting they wish to retain and those they wish to relinquish in favor of the dominant culture’s parental values, attitudes, and practices” (Garcia-Coll et al., 1996, p. 1904). Among Latinos in the United States, acculturation has also been associated with meaningful differences in parenting practices (Calzada, Huang, Anicama, Fernandez, & Brotman, 2012; Halgunseth et al., 2006). Descriptive statistics from studies with large community samples (e.g., Early Head Start National Research and Evaluation Project; Fragile Families and Child Well-Being Study) suggest that foreign-born and less acculturated Latina mothers (that is, Latinas with lower levels of adoption of U.S. behaviors, attitudes, and values) use spanking and verbal punishment less frequently than more acculturated Latina mothers (Altschul & Lee, 2011; Berlin et al., 2009; Lee, Perron, Taylor, & Guterman, 2011; Taylor, Guterman, Lee, & Rathouz, 2009). In contrast, other studies suggest that higher levels of acculturation are associated with lower levels of physical and punitive discipline (Hill, Bush, & Roosa, 2003; Regalado, Sareen, Inkelas, Wissow, & Halfon, 2004). Still, no study of which we are aware has considered all of these factors (cultural, socioeconomic) in relation to both spanking and verbal punishment. We therefore examine demographic, socioeconomic, and child factors (marital status, maternal education, maternal age, child gender, child internalizing and externalizing behaviors) that have been previously associated with spanking and verbal punishment (Berger, 2005; Berlin et al 2009; Frias-Armenta & McCloskey, 1998; Maguire et al., 2014; Smith & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Wissow, 2001), as well as mothers’ acculturative status to better understand the correlates of spanking and verbal punishment among immigrant Latina mothers. We also consider sources of support (specifically, support from family) and stress (specifically, household crowding). Perceived familial social support is inversely related to child maltreatment, suggesting that it may protect against the use of corporal punishment (Li, Godinet & Arnserberger, 2011; Martin, Gardner & Brooks-Gunn, 2012). Alternately, household crowding is positively associated with verbal hostility and punitive parenting (Deater-Deckard, Chen, & Bell, 2012; Evans & Saegert, 2000) and is especially relevant in large urban centers like New York City (Schill, Friedman & Rosenbaum 1998), where this study takes place.

The Present Study

The overarching aim of the present study is to examine whether spanking and verbal punishment in response to child misbehavior are associated with later child adjustment in immigrant Latino families of young children. To this end, we describe the use of spanking and verbal punishment (at Time 1) in a large community sample of Latina immigrant mothers of young children; test for correlates associated with these discipline practices at Time 1; and examine the association of spanking and verbal punishment with later (Time 2) child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. A second aim is to test whether the influence of spanking or verbal punishment on child outcomes is moderated by (1) contextual characteristics of the mother-child relationship (e.g., maternal warmth) and (2) the family’s cultural context (e.g., ethnicity, cultural value of respeto). A handful of studies has examined parenting context (e.g., warmth; Berlin et al. 2009; German et al., 2013; Stacks et al., 2009) as a moderator of the association between spanking, verbal punishment, and adverse adjustment among Latinos, but no studies to date with Latino families have tested moderation by cultural context, including country of origin and cultural values, although examination of the influence of cultural variables is often recommended in understanding inconclusive associations between punitive discipline and Latino child outcomes (Halgunseth et al., 2006; Lee & Althschul, 2014; Yildirim & Roopnarine, 2014).

We expect that warmth will attenuate the influence of physical discipline on child outcomes, as demonstrated in previous studies with Latino children (McLoyd & Smith, 2002) and adolescents (German et al., 2013). We make no hypothesis as to whether warmth will moderate the association between verbal punishment and child outcomes given the lack of literature. In considering cultural context as a moderator, we examine two Latino ethnic groups: Mexican-origin and Dominican-origin families. These groups have distinct sociohistorical backgrounds (e.g., migration history and pattern, demographic profiles; Yoshikawa 2011), which may lead to subgroup differences in family processes and specifically, in how punitive discipline influences child outcomes. Finally, we examine moderation by the cultural value of respeto and hypothesize that respeto will buffer the link between punitive discipline practices and child outcomes. Specifically, we posit that in households where respeto is highly endorsed, punitive parenting practices may be perceived as a means by which to inculcate the value respeto (Calzada et al. 2010), thereby understood to be normative rather than rejecting, thus attenuating the association between punitive parenting and child internalizing and externalizing problems.

METHOD

Participants

This study uses data from Mexican- (MA) and Dominican-origin (DA) families who participated in a multi-method longitudinal study examining the early childhood development of Latino children in New York City. Seven hundred and fifty families were recruited from pre-kindergarten (pre-k) and kindergarten (K) classrooms across New York City drawn from 24 public schools. All children were 4 or 5 years old (M =4.43, SD =.59) at the time of enrollment (Time 1), and they were re-assessed approximately 12 months later (Time 2). To better understand the correlates of spanking and verbal punishment among immigrant families, we limited our sample to mothers born outside the United States (n=684). Among these eligible families, we further limited the sample to 633 families (93% of the eligible sample) who had baseline family predictor and parent-rated child outcome data. Of these, 588 (93% of study sample) had teacher-rated child outcome data at baseline. At Time 2, 476 (75%) had child problem behavior outcome data (465/73% with parent-rated and 387/61% with teacher-rated data). Baseline partial missing data analyses indicated that children with and without teacher-rated data did not differ on parent-rated baseline child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Time 2 attrition analyses also indicated that there were no differences in child gender, poverty status, or on baseline mean levels of parenting practices or parent-rated child internalizing and externalizing behaviors between families who did and did not complete an assessment at Time 2. There were differences, however, in ethnicity, education, and marital status. Immigrant mothers who completed a Time 2 assessment were more likely to be Mexican, have less than a high school education, and be married. In the final sample, 60.7% of mother-child dyads were Mexican, and child gender was equally distributed (50.1% male). A majority of the mothers (77.8%) were married or living with a partner, roughly half (53.9%) had at least a high school education, and nearly three quarters (74.3%) reported household incomes below the poverty level. There were on average 5 people living in a home (M =5.18, SD=1.87), although the number ranged from 2 to 18 people. Mothers had been residing in the United States an average of 11.95 years (SD =6.35). See Table 1 for sample characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Descriptive Information for Variables of Interest

| Variable | Total M (SD) | Minimum/Maximum |

|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age | 32.50 (6.61) | 18.00–68.00 |

| Child’s age | 4.43 (.59) | 3.00–6.00 |

| Social support from family | 6.06 (1.14) | 1.00–7.00 |

| Number of people in home | 5.15 (1.83) | 2.00–18.00 |

| Number of years residing in United States | 11.95 (6.35) | 1.00–35.00 |

| U.S. American knowledge | 1.90 (.67) | 1.00–4.00 |

| U.S. American identity | 2.46 (.93) | 1.00–4.00 |

| English language competence | 2.00 (.72) | 1.00–4.00 |

| Verbal harsh | 1.86 (.51) | 1.00–4.00 |

| Spanking | 1.44 (.54) | 1.00–3.67 |

| Warmth | 4.44 (.64) | 1.80–5.00 |

| Respeto | 3.99 (.47) | 2.35–5.00 |

| Externalizing (T1), parent | 47.97 (9.75) | 31.00–92.00 |

| Externalizing (T2), parent | 46.99 (8.70) | 31.00–83.00 |

| Internalizing (T1), parent | 53.14 (10.87) | 29.00–104.00 |

| Internalizing (T2), parent | 52.46 (10.02) | 28.00–87.00 |

| Externalizing (T1), teacher | 46.94 (8.32) | 40.00–92.00 |

| Externalizing (T2), teacher | 47.00 (8.59) | 41.00–93.00 |

| Internalizing (T1), teacher | 46.24 (8.47) | 35.00–92.00 |

| Internalizing (T2), teacher | 46.84 (9.94) | 37.00–105.00 |

| % | ||

| Mexican | 60.7 | |

| Child gender (male) | 50.1 | |

| Poor | 74.3 | |

| Marital status (single) | 22.6 | |

| < High school graduate / GED | 46.1 | |

| Externalizing (T1), parent, risk (Tscore≥60) | 10.3 | |

| Externalizing (T2), parent, risk (Tscore≥60) | 8.0 | |

| Internalizing (T1), parent, risk (Tscore≥60) | 26.1 | |

| Internalizing (T2), parent, risk (Tscore≥60) | 24.4 | |

| Externalizing (T1), teacher, risk (Tscore≥60) | 8.0 | |

| Externalizing (T2), teacher, risk (Tscore≥60) | 9.3 | |

| Internalizing (T1), teacher, risk (Tscore≥60) | 7.5 | |

| Internalizing (T2), teacher, risk (Tscore≥60) | 10.7 |

Note. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; parent = parent report; teacher =teacher report. Poverty is based on federal poverty guidelines, with consideration for number of persons living in the home. An income-to-needs ratio below 1 is considered poor and indicates that the income for the respective family is below the official definition of poverty. M (SD) and % were based on the raw data.

Procedure

Families were recruited between 2010 and 2013. At collaborating sites, research staff, fluent in Spanish and English, attended parent meetings and were present during daily school drop-off and pick-up times to inform parents of the study. To be eligible for the study, mothers had to identify as either Mexican or Dominican, and their children had to be newly enrolled in the partner school. The recruitment rate among eligible families averaged 72% (53 – 94%) across sites.

Interested mothers were scheduled for an appointment at their child’s school where they were met by a pair of bilingual research assistants. One research assistant interviewed the mother, and the other administered a battery of psychological tests to the child; data from child testing are not considered in the present study. Participating mothers were asked which language they preferred to be interviewed in (Spanish or English) before beginning any research activities. Among our immigrant study sample, the majority of mothers (95%) chose to be interviewed in Spanish. Interviews lasted 2 hours, and mothers received a $40 stipend for their participation. Teachers of participating children (99% of mothers consented to the collection of teacher report) were then asked to consent and complete a packet of questionnaires; participating schools and teachers received a $500 honorarium to support classroom needs.

Measures

This study uses parent report of parenting practices, cultural socialization, acculturation, and sociodemographic characteristics collected at Time 1, and parent and teacher report of child behavior collected at Times 1 and 2. All parent questionnaires were available in Spanish and English. Parenting and social support measures were translated into Spanish and back translated by two pairs of bilingual translators from different countries of origin to address the possibility of dialect differences. The measures of parenting practices, cultural socialization, acculturation, and child behavior used in this study have demonstrated adequate validity and reliability in past studies with Mexican and Dominican immigrant mothers (see Calzada, Barajas-Gonzalez, Huang, & Brotman, 2015; Serrano-Villar, Huang, & Calzada, 2016).

Punitive Discipline Practices.

Items from the harsh discipline subscale of the Parenting Practices Interview (PPI; Webster-Stratton, 1998) and the authoritarian subscale of the Parenting Styles and Dimensions (PSD; Robinson, Mandleco, Olsen, & Hart, 1995) were used to create measures of verbal punishment and spanking for this study. In the PPI, parents were asked, “In general, how often do you do each of the following things when your child misbehaves (that is, do something s/he is not supposed to do)?” and were then read a list of items, such as “give spanking.” In the PSD, parents were asked, “Please rate how often you exhibit this behavior with your child,” and read a list of items, such as “yell or shout when child misbehaves.” On both assessments, parents responded on a 5-point likert scale anchored by never and very often. The verbal punishment scale (6 items, α = .69; “use threats as punishment with little or no justification,” “yell or shout when child misbehaves,” “when arguments build up, do or say things you don’t mean to,” “explode in anger towards child,” “yell or scold when child misbehaves”, and “show anger when disciplining child”) and spanking scale (3 items, α = .78 “spank child when disobedient,” “slap child when the child misbehaves,” and “give child a spanking”) were created by averaging across items, with higher scores reflecting more frequent use of these discipline practices.

Correlates of Punitive Discipline.

Sociodemographic variables, including maternal age, marital status, poverty status, maternal education (1= high school or above), child gender (1= male), and number of people in the household, were collected using a demographic form administered at Time 1. Poverty was calculated by comparing each respondent’s reported annual household income with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services poverty guidelines. Acculturative status was assessed using the Abbreviated Multidimensional Acculturation Scale (AMAS; Zea, Asner-Self, Birman, & Buki, 2003), a 42-item measure of acculturative status that was developed and standardized in English and Spanish with Latino university students and community members from various countries of origin. Items were rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) and correspond to cultural competence, language competence, and identity; higher scores indicate higher levels of competence or identity. All domains are measured for both culture of origin (enculturation) and mainstream/ “U.S. American” culture (acculturation). For this study, the U.S. American cultural knowledge (e.g. “how well do you know American history?” ), English language competence (e.g. “how well do you speak English with American friends?”), and U.S. American identity (e.g. “I have a strong sense of being U.S. American”) subscales were used. The three acculturation subscales showed strong internal consistencies with the present sample of immigrant mothers (αs ranged from .92 – .97). We also considered number of years of residence in the United States, calculated based on mother’s report of the year in which they arrived to the United States. Familial social support was assessed using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet & Farley, 1988) administered at Time 1. Respondents indicated agreement on four items tapping into social support from family members (e.g., “my family really tries to help me” and “I can talk about my problems with my family”) on a Likert-scale ranging from very strongly disagree (1) to very strongly agree (7); scores were averaged to reflect total support from family (α = .86).

Potential Moderators.

Parental warmth was assessed using the PSD (described above). The warmth subscale consists of 5 items (e.g., “gives comfort and understanding when child is upset,” and “has warm and intimate time together with child”) and demonstrated adequate internal reliability (α =.68).

The cultural value of respeto was assessed using the Cultural Socialization of Latino Children (CSLC; Calzada et al., 2012), a measure that was developed based on qualitative data of Latina mothers’ cultural values (Calzada et al., 2010). The measure was developed with parallel versions in Spanish and English. The respeto scale includes 20 items (e.g., “I tell my child to defer to adult wishes.”) each rated on a 5-point likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. A mean scale scores was created, with higher scores reflecting more socialization of respeto. Internal consistency was adequate (α =.79).

Mothers’ ethnicity was coded dichotomously (Mexico =1; Dominican Republic=0) based on her self-reported country of origin.

Child Functioning.

The Behavior Assessment System for Children, Parent Rating Scale and Teacher Rating Scale (BASC PRS, BASC TRS; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) is a measure of child behavior and emotional functioning for children between the ages of 2.5 and 18 years. Two versions—for young children (2.5 – 5.11 years) and for school-aged children and adolescents (6 – 18 years)—were used depending on the age of the participant child. The parent form (the PRS) is available in both English and Spanish based on translation and standardization by the measure developers with a sample of 386 Latinos (specific ethnic groups not described; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). The Spanish language version is meant to be used with Spanish-speakers from any country of origin (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). In the present study, standardized (T) scores from the internalizing and externalizing scales (αs ranged from .80-.89) were used. One-year stability of parent-rated problem behaviors for the current study sample was high (rs = .73 for externalizing and .67 for internalizing), and low to moderate for teacher-rated problem behaviors (rs = .52 for externalizing and .21 for internalizing based on ratings from different teachers across two school years).

Data Analytic Plan

To describe the use of spanking and verbal punishment (Aim 1), we conducted descriptive statistics. To examine factors associated with spanking and verbal punishment at Time 1 (Aim 2), correlates were included as sets in linear regression models, with sociodemographic predictors, acculturation predictors, parenting predictors, and parent report of child internalizing and externalizing behavior entered in four-step sequences. Spanking and verbal punishment were examined separately. To test the influence of discipline practices (verbal and physical) on Time 2 internalizing and externalizing behavior, and interaction of discipline practices with other contextual factors (Aim 3), we first examined the direct associations (main effects) between spanking and verbal punishment and child behavioral outcomes, followed by examining three potential moderators (warmth, respeto, and ethnicity). In the main effect model, we included both spanking and verbal punishment, as well as all study moderators in the linear regression models. To test the moderation effects, we added spanking-by-moderator and verbal punishment-by-moderator in the main effect models. Each moderator was tested separately. When significant moderation occurred, we plotted the simple slope for the relation between the discipline variable of interest and child outcome at 1 standard deviation above (“high” level) and below (“low” level) the mean level of the moderator. All analyses adjusted for potential confounders (i.e., child gender, parental education, years in the United States, social support, and household size). Furthermore, Time 1 internalizing and externalizing behaviors (by reporter) were included in each of the regression models (e.g., Time 1 parent report of internalizing and externalizing included in the model predicting Time 2 parent report of externalizing; Time 1 teacher report of internalizing and externalizing included in the model predicting Time 2 teacher report of internalizing, etc.). Analyses were carried out separately for the four reports of child behaviors (parent- and teacher-rated externalizing and internalizing problems).

Analyses for Aims 1 and 2 were based on raw data because of nearly completed data. For Aim 3, we applied multiple imputation methods (Little & Rubin, 2002) to account for partial missing data for child outcome measures (7% missing teacher-rated child outcome data at Time 1; 27% and 39% missing parent-rated and teacher-rated child outcome data at Time 2, respectively). Data were within the recommended follow-up threshold of 60–80% (Vicki, Manno, & Côté, 2004), and attrition analyses indicated that children with and without Time 1 teacher-rated and Time 2 teacher- and parent-rated data did not differ on parent rated baseline child internalizing and externalizing behaviors (described above), suggesting notable biases were less likely to occur (Little & Rubin, 2002). We assumed data were missing at random, and applied SAS Multiple Imputation procedure to impute 10 replicated data sets. The imputation made use of the joint distribution of all the outcome variables, demographic factors, and moderators considered in this study. SAS PROC MIANALYZE was used to combine the results for the final inference testing (SAS 9.13, Cary, NC). To inspect the consistency, we compared the imputed results with non-imputed results.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics of the Sample

Descriptive statistics for variables of interest are presented in Table 1. Mothers reported relatively low levels of US American cultural knowledge, M=1.90, SD=.67, English language competence, M=2.00, SD = .72, and moderate levels of U.S. American identity, M=2.46, SD = .93. Mothers reported relatively high levels of familial social support, M =6.09, SD= 1.05, parental warmth, M =4.44, SD=.64, and respeto, M = 3.96, SD= .46.

At Time 1, parent report of child internalizing and externalizing mean levels were in the average range (norm population sample M= 50, SD=10), with considerable variability (range varied from 29.00 to 91.00 for internalizing and from 31.00 to 90.00 for externalizing). At Time 1, 26% of children had internalizing T scores of 60 or greater, placing them in the at-risk/clinical range of internalizing problems based on mother ratings. Ten percent of children had T scores of 60 or greater on externalizing problems based on mother ratings. Time 1 teacher-reported child internalizing, M = 45.91, SD= 7.92, and externalizing, M =46.23, SD=7.15, behaviors were similar.

Levels of Spanking and Verbal Punishment

Mean levels of spanking were relatively low, M = 1.44, SD= .54, as were levels of verbal punishment, M =1.86, SD= .51. Item-level descriptives (not shown) indicate that 50.7% of mothers reported never using any sort of physical punishment when disciplining their child. Of the three physical discipline questions, the most endorsed was “give your child a spanking when child misbehaves” with 41.4% of mothers responding that they had done so either seldom (26.2%), sometimes (15.0%) or often (0.2%), M=1.57, SD = .75. In contrast, only 3% of mothers indicated that they never used any form of verbal punishment. The most strongly endorsed item was “scold or yell when your child misbehaves”, M=2.71, SD=.83, with 91.8% of mothers indicating they had done so either seldom (26.5%), sometimes (53.9%), often (9.0%) or very often (2.4%).

Correlates of Spanking and Verbal Punishment

Regression results for the association between sociodemographic, acculturation, parenting, and child behavior correlates and spanking and verbal punishment are shown in Table 2. Among sociodemographic predictors (model 1), child gender (male), social support from family, and household size were significantly associated with the use of both spanking and verbal punishment. Male children, low social support, and greater number of household members were associated with greater use of spanking and verbal punishment. Among acculturation predictors (model 2), after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, U.S. American knowledge was inversely associated with spanking. Among parenting context factors (model 3), after adjusting for sociodemographic and acculturation factors, higher maternal warmth was associated with less use of verbal punishment. Finally, child externalizing problems were related to parental use of spanking; and both externalizing and internalizing problems were related to parent use of verbal punishment (model 4).

TABLE 2.

Multivariate Regression Estimates of Spanking and Verbal Punishment at Time 1

| Spanking |

Verbal Punishment |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Step 1. Household context | Est (SE) | p | Est(SE) | p | Est(SE) | p | Est(SE) | p | Est(SE) | p | Est(SE) | p | Est(SE) | p | Est(SE) | p |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Male | .119 (.043) | .006 | .123 (.043) | .005 | .120 (.043) | .006 | .098 (.043) | .022 | .090 (.041) | .029 | .102 (.042) | .015 | .096 (.042) | .021 | .068 (.038) | .075 |

| Poverty | −.034 (.051) | .514 | −.045 (.054) | .402 | −.048 (.054) | .371 | −.040 (.053) | .442 | −.062 (.049) | .206 | −.061 (.051) | .236 | −.069 (.051) | .182 | −.057 (.046) | .221 |

| Single parent household | −.076 (.053) | .152 | −.059 (.054) | .282 | −.063 (.055) | .248 | −.091 (.054) | .093 | −.021 (.051) | .681 | −.016 (.052) | .754 | −.023 (.053) | .668 | −.074 (.047) | .122 |

| Maternal HS education | −.042 (.045) | .351 | −.026 (.048) | .588 | −.021 (.048) | .661 | −.016 (.047) | .737 | −.083 (.043) | .054 | −.057 (.046) | .212 | −.054 (.045) | .234 | −.048 (.042) | .248 |

| Maternal age | −.001 (.003) | .860 | .002 (.004) | .551 | .003 (.004) | .513 | .003 (.004) | .406 | −.002 (.003) | .492 | −.004 (.004) | .253 | −.004 (.004) | .234 | −.002 (.003) | .479 |

| Social support from family | −.059 (.019) | .002 | −.055 (.019) | .004 | −.054 (.019) | .006 | −.042 (.019) | .027 | −.043 (.018) | .018 | −.041 (.018) | .026 | −.037 (.019) | .045 | −.020 (.017) | .249 |

| Number of people in the home | .030 (.013) | .019 | .023 (.013) | .074 | .023 (.013) | .081 | .017 (.013) | .178 | .029 (.012) | .018 | .023 (.012) | .066 | .024 (.102) | .053 | .011 (.011) | .346 |

| Step 2. Maternal acculturation | ||||||||||||||||

| Year in the United States | -- | -- | −.002 (.004) | .726 | −.001 (.004) | .748 | −.002 (.004) | .578 | -- | -- | .008 (.004) | .062 | .008 (.004) | .076 | .006 (.004) | .107 |

| English language competence | -- | − | .050 (.049) | .313 | .060 (.050) | .227 | .049 (.049) | .314 | -- | − | −.024 (.047) | .611 | −.023 (.041) | .574 | −.029 (.043) | .502 |

| U.S. American identity | -- | − | −.040 (.026) | .120 | −.042 (.026) | .105 | −.037 (.025) | .140 | -- | -- | −.032 (.025) | .199 | −.035 (.025) | .157 | −.029 (.022) | .194 |

| U.S. American cultural knowledge | -- | − | −.095 (.048) | .048 | −.098 (.048) | .043 | −.093 (.047) | .046 | -- | − | −.029 (.046) | .527 | −.034 (.046) | .460 | −.020 (.042) | .630 |

| Step 3. Parenting context | ||||||||||||||||

| Maternal warmth | -- | -- | -- | -- | −.038 (.036) | .296 | −.024 (.035) | .498 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −.069 (.034) | .044 | −.048 (.031) | .123 |

| Socializing respeto | -- | − | -- | − | .048 (.048) | .318 | .009 (.049) | .852 | -- | − | -- | − | .088 (.046) | .056 | .005 (.042) | .904 |

| Step 4. Child behavior | ||||||||||||||||

| Externalizing (parent report) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .011 (.003) | .000 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .018 (.002) | .000 |

| Internalizing (parent report) | -- | − | -- | − | -- | − | .001 (.002) | .696 | -- | − | -- | − | -- | − | .006 (.002) | .008 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| R 2 | .046 | .061 | .064 | .106 | .039 | .049 | .060 | .227 | ||||||||

Note. Maternal HS Education= Maternal high school education (1=High school or above). Analyses were also conducted adjusting for both parent and teacher reported behaviors (N=588); teacher rated internalizing and externalizing behaviors were not significantly associated with spanking or verbal punishment (results are available from the first author).

Spanking and Verbal Punishment as Predictors of Child Outcomes

Table 3 presents the results of the regression analyses examining the main and moderated effects of spanking and verbal punishment on child externalizing and internalizing behaviors using imputed data. In the main effect model, verbal punishment was associated with greater child externalizing and internalizing problems (parent report) one year later. Discipline practices were not associated with teacher rated child externalizing or internalizing problems.

TABLE 3.

Main and Moderation Effects in the Association between Punitive Discipline at Time 1 and Child Behavioral Problems at Time 2

| Parent Report, Time 2 | Teacher Report, Time 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Externalizing | Internalizing | Externalizing | Internalizing | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| Main Effect Model | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p |

|

|

||||||||

| Mom HS Edu | .20 (.60) | .739 | −.76 (.76) | .319 | −.59 (.79) | .458 | −.04 (1.11) | .973 |

| Child Male (0=Female) | .33 (.55) | .548 | .22 (.70) | .754 | .33 (.79) | .675 | −.94 (1.18) | .425 |

| Parents years in the US | −.03 (.04) | .513 | −.11 (.05) | .036 | −.01 (.06) | .922 | −.07 (.09) | .415 |

| Social support | .16 (.25) | .517 | −.03 (.32) | .934 | −.19 (.38) | .616 | .28 (.47) | .546 |

| Household size | −.26 (.15) | .095 | −.37 (.18) | .047 | −.47 (.20) | .021 | −.46 (.27) | .083 |

| T1 Externalizing problems | .65 (.04) | <.001 | .02 (.05) | .707 | .53 (.05) | <.001 | .11 (.07) | .101 |

| T1 Internalizing problems | .004 (.03) | .892 | .56 (.04) | <.001 | −.04 (.05) | .416 | .19 (.07) | .009 |

| Spanking | −.33 (.55) | .547 | −.22 (.68) | .749 | 1.03 (.79) | .198 | .71 (1.05) | .498 |

| Verbal punishment | 1.69 (.63) | .008 | 1.57 (.78) | .047 | −.74 (.83) | .378 | −.83 (1.13) | .462 |

| Warmth | −.18 (.44) | .685 | .15 (.52) | .768 | −.29 (.65) | .661 | .24 (.82) | .774 |

| Respeto | −.22 (.65) | .731 | 1.21 (.78) | .123 | 1.83 (.92) | .051 | −.43 (1.22) | .725 |

| Mexican (0=DA) | −.33 (.67) | .629 | .68 (.81) | .398 | −.36 (.91) | .692 | −.53 (1.18) | .652 |

| Ethnicity Moderation Model (MA=1) | ||||||||

| Spanking × MA | −.23 (1.16) | .841 | −.59 (1.48) | .693 | −1.05 (1.53) | .493 | 1.45 (2.01) | .471 |

| Verbal punishment × MA | −.29 (1.17) | .803 | 3.07 (1.43) | .033 | .11 (1.51) | .941 | −.57 (2.08) | .785 |

| Respeto Moderation Model | ||||||||

| Spanking × Respeto | 1.47 (1.11) | .186 | .93 (1.45) | .521 | .45 (1.47) | .757 | −1.11 (2.03) | .587 |

| Verbal punishment × Respeto | −.05 (1.24) | .966 | .20 (1.58) | .899 | −1.29 (1.68) | .443 | .26 (2.07) | .900 |

| Parenting Context Moderation Model | ||||||||

| Spanking × Warmth | .18 (.84) | .827 | −.46 (1.13) | .687 | −.64 (1.07) | .550 | −1.64 (1.53) | .283 |

| Verbal punishment × Warmth | −.91 (.84) | .279 | −.50 (1.07) | .641 | −1.07 (1.09) | .328 | −.29 (1.44) | .838 |

Note. N=633. Results are based on imputed data and are consistent with results using unimputed data. Problem behaviors were assessed at Time 2 (one year after Time1). The main effect model includes two main punitive discipline predictors and moderators. For the moderation models, all main predictors were included as main effects prior to include the interaction terms (estimates not show). HS = high school. T1 = Time 1. For teacher reported child behavior, because teachers generally rated multiple students, we accounted for potential correlations among outcomes of children by applying linear mixed effect models (using SAS PROC MIXED procedure) and including a random effect for teacher.

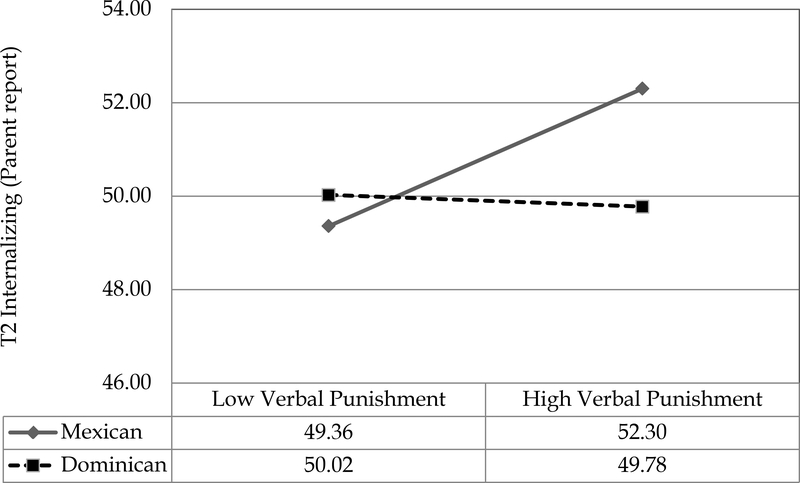

In the moderation effect testing, we found no moderated effects in the link between verbal punishment and parent- or teacher-reported child externalizing problems, but ethnicity emerged as a significant moderator in the link between verbal punishment and parent-rated internalizing problems, p=.033. Post-hoc analyses indicated that the association between verbal punishment and child internalizing problems was significant only for MA (and not DA) families, in that verbal punishment was associated with more internalizing problems for MA children, p =.001, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Association Between Verbal Punishment at Time 1 and Child Internalizing at Time 2, Moderation by Ethnicity

We found no effects between spanking and child outcomes on parent- or teacher-reported child internalizing or externalizing problems. Results were consistent using imputed and non-imputed data.

DISCUSSION

Like all parents, Latino immigrant parents in the United States are faced with the challenge of finding a balance between parenting in a manner that is both emotionally responsive to a child’s needs and also firm so as to guide and correct a child’s behavior. The benefits of emotionally responsive parenting are uncontested, but the impact of parental control on Latino child outcomes is less conclusive. Spanking and verbal punishment have been linked to greater externalizing and internalizing problems in children (Gershoff et al., 2012; Vissing & Straus, 1991; Yildirim & Roonarine, 2014), but not consistently (Slade & Wissow, 2004; Stacks, Oshio, Gerard, & Roe, 2009), thus leading some scholars to posit that culture and context may moderate associations between disciplinary practices and child outcomes. The present study contributes to the literature on Latino parenting and child development by examining spanking and verbal punishment—its use and its correlates—among immigrant families of young Latino children. Overall, mothers in this study reported relatively low levels of spanking and high levels of parental warmth. The high levels of self-reported warmth and low levels of self-reported spanking in this community sample challenge the notion that Latino parents are harsh at the expense of being warm, and lend support to other studies that find Latino parents of young children engage in parenting that is both nurturing and firm (e.g., Calzada & Eyeberg, 2002; Carlson & Harwood, 2003).

We also examined factors associated with spanking and verbal punishment and found that male child gender, familial social support, and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors were significant correlates of both spanking and verbal punishment, consistent with Belsky’s process model. Our finding that male gender is a significant correlate of both physical and verbal discipline is consistent with the literature indicating that boys elicit discipline more so than girls (Boutwell, Frankine, Barnes, & Beaver, 2011; Giles-Sims, Straus, & Sugarman, 1995). Consistent with past studies (Hashima & Amato, 1994; Martin, Gardner, & Brooks-Gunn, 2012), social support was associated with less spanking and verbal punishment. The robust negative association between social support and punitive discipline suggests that social support from family members is a particularly salient protective factor for immigrant Latino mothers of young children. Indeed, social support has been found to buffer against psychological distress related to economic strain (Prelow, Weaver, Bowman & Swenson, 2010) as well as parenting stress (Cardoso, Padilla & Sampson, 2010) among Latina mothers.

We also found a negative association between U.S. American cultural knowledge and spanking, a finding that is inconsistent with past research that shows more spanking among more acculturated mothers (e.g., Berlin et al., 2009); this discrepancy may be due to how acculturation is measured across studies. The present study assessed three different domains of acculturation (language, cultural knowledge, and identity) among immigrant mothers, whereas other studies have created acculturation indices by summing several proxy variables (e.g., nativity, language use) into one scale. The negative association between U.S. American cultural knowledge and spanking is consistent with qualitative research finding that some immigrant parents are afraid to use disciplinary strategies such as spanking for fear of negative legal consequences in the United States (e.g., the child threatens to call local authorities, see Parra-Cardona et al 2009). It may also be that, as Latina mothers are exposed to mainstream ideas, they become more familiar with, and adopt, Westernized discipline practices (Garcia-Coll et al., 1996). Further research using more nuanced measures of acculturation and context (Bornstein, 2017; Halgunseth et al., 2006) is needed to inform our understanding of why, whether, and how immigrant families adapt their parenting practices as they adjust to their new environment.

In examining the associations between spanking and child outcomes, we found no relation with mother-reported or teacher-reported child internalizing or externalizing problems. This suggests that the majority of Latina immigrant mothers in our sample who employed physical discipline did so in a way that did not contribute to their children’s psychopathology 1 year later. The correlates of discipline in this study support the possibility that some mothers spank due to stress and that others may do so because they believe it is a means by which to inculcate respeto. This mix of maternal motivations (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994; Halgunseth et al., 2006) may have resulted in non-significant findings. Research that employs mixed methods to better understand the motivations behind certain disciplinary practices among Latino immigrant mothers with young children could greatly inform this area of research.

We found that verbal punishment was associated with greater externalizing behaviors (mother report), regardless of parental warmth or cultural context. Finally, high levels of harsh verbal punishment were associated with greater internalizing behaviors, but only among Mexican children. Taken together, these findings suggest that verbal punishment is associated with adverse outcomes for young Latino children and that children in Mexican immigrant families might be particularly susceptible to its negative effects. It may be that in Mexican immigrant households, the cumulative effect of poverty and its associated stressors make children more vulnerable to the negative impact of verbal punishment. Research with immigrant families in NYC indicates that Mexican immigrant households are especially stressed (e.g., overcrowded) and, given their more recent migration to NYC, do not have the long-standing community organizations / access to social capital that Dominicans in NYC have (Yoshikawa, 2011); indeed, levels of linguistic isolation and poverty were significantly higher for the Mexican immigrant families in this study. The accumulation of risk factors may be impacting Mexican immigrant families and children in a manner not formally tested here. In other words, the key contextual characteristic is likely sociodemographic risk rather than ethnicity per se.

To capture cultural context more directly, we also considered the Latino cultural value of respeto as a moderator. Consistent with the cultural normativeness hypothesis (Lansford et al., 2005) and with Grusec et al.’s (1997) proposal that controlling practices are not parent-centered in collectivist cultures, we expected that spanking and verbal punishment may be perceived as a normative means by which to inculcate respeto in households where it was highly valued (e.g., respeto would attenuate the link between punitive discipline and child outcomes). This hypothesis was not supported, as respeto did not moderate the significant associations between verbal punishment and child outcomes. Studies testing the cultural normativeness hypothesis have found mixed support, with results varying based on the type of discipline method examined (Gershoff et al., 2010) and whether child or parent report of normativeness is used (Gershoff et al., 2010; Lansford et al., 2005). It is possible that when children are very young, they are not able to interpret punitive discipline as normative rather than rejecting (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994). The limited cognitive skills of participant children, as pre-kindergartners and kindergartners, may also help explain why warmth did not moderate the association between verbal punishment and child outcomes either. It is also important to note that of the studies that have focused specifically on warmth and harsh verbal discipline (McKee et al., 2007; Wang & Kenny, 2014), both found a direct association with adverse youth outcomes that was not moderated by warmth. Our study extends these findings to Latino families of young children to suggest that verbal punishment negatively impacts children regardless of a warm parent-child relationship.

Despite the significance of these results, mean levels of spanking were low, and only 7% of mothers in the sample could be considered as globally harsh (i.e., a standard deviation or greater above the mean on both spanking and verbal punishment). Although limited to self-reported data, these results lend support to the notion that punitive discipline is non-normative in Latino immigrant families of young children. They also, however, introduce the possibility that the low levels of physical discipline limited our ability to detect moderated effects based on the cultural and parenting contexts.

Other limitations need to be noted. The measures of spanking and verbal punishment used in this study did not specify a time period during which the parenting practices of interest occurred making them different from most existing studies of spanking and verbal punishment. Additionally, this was a 1-year longitudinal study. There may be dormant effects of spanking and verbal punishment, or different patterns in use of spanking, verbal punishment, and child adjustment over longer periods of time not captured here. The measures of parenting and respeto were based on maternal self-report, and, as such, social desirability bias may have influenced mothers’ reports of spanking and verbal punishment. Additionally, other cultural values salient to Latino parenting (e.g., familismo) that were not considered in this study may, in concert with respeto and warmth, influence Latino child adjustment. Moreover, we cannot discount that the positive association between parent report of verbal punishment and parent report of child internalizing and externalizing behaviors could be due to shared method variance, as parenting discipline practices were not associated with teacher-rated child internalizing or externalizing problems. Additionally, discipline practices were based on maternal report only; we do not know if paternal discipline practices would be associated with child outcomes in a similar manner. Emerging research with Latino families indicates that the impact of certain punitive parenting practices on child outcomes may differ depending on whether it is the mother’s or father’s parenting that is being examined (White, Liu, Nair, & Tein, 2015). Future studies that include both maternal and paternal report of parenting and cultural socialization practices would inform this area. Another limitation of this study is the limited generalizability, as our sample is not nationally representative, but rather based on a large community sample of immigrant Mexican and Dominican mothers in an urban environment.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THEORY AND PRACTICE

This study contributes to our understanding of the association between Latino parents’ use of verbal and physical discipline and young child outcomes in several important ways. First, we test for the impact of spanking and verbal punishment separately, and find that verbal punishment is associated with adverse child outcomes. This study adds to the small but growing literature that indicates that verbal punishment, be it in “mild” forms as assessed here, or in more aggressive forms (e.g., cursing at child, threatening child, belittling child; Vissing et al., 1991) negatively impacts young children. Parenting programs that aim to support child development by curbing the use of harsh parenting practices should pay special attention to verbal punishment, and emphasize that punitive parenting does not refer to spanking only, as verbal punishment is also associated with adverse child outcomes. Second, we build on previous literature by examining the potential role of cultural context, specifically respeto, as a moderator of the association between punitive verbal and physical discipline and child outcomes. Our findings support a growing body of literature that indicates that respeto is an important contextual variable that matters for the study of Latino family functioning. In this instance, we see that respeto is associated with teacher report of child externalizing symptoms.

The lack of a significant main effect between mild levels of spanking and young Latino child outcomes in this study suggests the potentially purposeful and appropriate use of spanking within some Latino immigrant families should be acknowledged. However, the lack of a significant main effect between spanking and child outcomes is not an endorsement for the use of spanking; the levels of spanking reported in this study by a community sample do not represent the full distribution of corporal punishment in the population (e.g., abuse that would mandate the involvement of child protective services). Moreover, given the controversial nature of parents’ physical discipline practices and the complicated association with child outcomes at different developmental stages, it is important that researchers continue to examine contextual influences that may give us a clearer picture of the long-term effects of spanking and verbal punishment on children from ethnically diverse backgrounds.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the collaborating school sites, the participant families, and the research staff who made this work possible. The authors would also like to thank the reviewers for their comments on prior versions of this manuscript. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors alone, and endorsement by the authors’ institutions and provided funding is not intended and should not be inferred.

Funding: This work was supported by Grant R01 HD066122-01 awarded to the second author from the NIH.

Role of the Funders/Sponsors: None of the funders or sponsors of this research had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Each author signed a form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No authors reported any financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to the work described.

Ethical Principles: The authors affirm having followed professional ethical guidelines in preparing this work. These guidelines include obtaining informed consent from human participants, maintaining ethical treatment and respect for the rights of human or animal participants, and ensuring the privacy of participants and their data, such as ensuring that individual participants cannot be identified in reported results or from publicly available original or archival data.

Contributor Information

R. Gabriela Barajas-Gonzalez, Center for Early Childhood Health and Development, Department of Population Health (CEHD), NYU School of Medicine, 227 East 30th Street, NY, NY 10016. ritagabriela.barajas-gonzalez@nyumc.org..

Esther Calzada, University of Texas at Austin.

Keng-Yen Huang, NYU School of Medicine.

Maite Covas, NYU School of Medicine.

Claudia M. Castillo, Northwestern University.

Laurie Brotman, NYU School of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- Ainsworth M & Bowlby J (1991). An ethological approach to personality development. American Psychologist, 46, 331–341. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1978). Social learning theory of aggression. Journal of Communication, 28, 12–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D (2012). Differentiating between confrontive and coercive kinds of parental power-assertive disciplinary practices. Human Development, 55, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Berzenski SR & Yates TM (2013). Preschoolers’ emotion knowledge and the differential effects of harsh punishment. Journal of Family Psychology, 27 (3), 463–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein L, & Bornstein MH (2014). Parenting styles and child social development. Retrieved from Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development website: http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/sites/default/files/textes-experts/en/654/parenting-styles-and-child-social-development.pdf

- Bornstein MH (2016). Determinants of parenting. In Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 4, Genes and Environment (3rd ed., pp. 180–245). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH (2017). The specificity principle in acculturation science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12 (1), 3–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutwell BB, Frankline CA, Barnes JC, & Beaver KM (2011). Physical punishment and childhood aggression: The role of gender and gene-environment interplay. Aggressive Behavior, 37(6), 559–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28, 759–779 [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Barajas-Gonzalez RG, Huang Y, & Brotman L (2015). Early childhood internalizing problems in Mexican- and Dominican-Origin children: The role of cultural socialization and parenting practices. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 4, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, & Eyberg SM (2002). Self-reported parenting practices in Dominican and Puerto Rican mothers of young children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 31, 354–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Fernandez Y, & Cortes D (2010). Incorporating the cultural value of respeto into a framework of Latino parenting. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 77–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Huang K-Y, Anicama C, Fernandez Y, & Brotman LM (2012). Test of a cultural framework of parenting with Latino families of young children. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18, 285–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso JB, Padilla YC, & Sampson M (2010). Racial and ethnic variation in the predictors of maternal parenting stress. Journal of Social Service Research, 36, 429–444. 10.1080/01488376.2010.510948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson V, & Harwood RL (2003). Attachment, culture, and the caregiving system: The cultural patterning of everyday experiences among Anglo and Puerto Rican mother-infant pairs. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24 (1), 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Kull M, & Carrano J (2014). Parental endorsement of spanking and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems in African American and Hispanic families. Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge K. Al, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Physical discipline among African American and European-American mothers: Links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996; 32:1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Domenech-Rodriguez MM, Donovick MR, & Crowley SL (2009). Parenting styles in a cultural context: observations of “protective parenting” in first-generation Latinos. Family Process, 48, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Bonds D, Millsap R (2009). Academic success in Mexican American adolescent boys and girls: The role of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting and cultural orientation. Sex Roles, 60, 588–599. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Saegert S. Residential crowding in the context of inner city poverty. In: Wapner S, Demick J, Minami H, Yamamoto T, editors. Theoretical Perspectives in Environment-Behavior Research. New York, NY: Plenum; 2000. pp. 247–268. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ. (2013). Spanking, corporal punishment and negative long-term outcomes: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 196–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fracasso MP, Busch-Rossnagel NA, & Fisher CB (1994). The relation between maternal behavior and acculturation to the qualities of attachment in Hispanic infants living in New York City. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 16, 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, Vasquez-Garcia H. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German M, Gonzales N, McLain D, Dumka L, & Millsap R (2013). Maternal warmth moderates the link between harsh discipline and later externalizing behaviors for Mexican American adolescents. Parenting: Science and Practice, 13(3), 169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A metaanalytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 539–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, & Grogan-Kaylor A (2016). Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. Journal of Family Psychology, Advance online publication. 10.1037/fam0000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A, Lansford JE, Chang L, Zelli A, Deater-Deckard K, & Dodge KA (2010). Parent discipline practices in an international sample: Associations with child behaviors and moderation by perceived normativeness. Child Development, 81(2), 487–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Lansford JE, Sexton HR, Davis-Kean PE, & Sameroff AJ (2012). Longitudinal links between spanking and children’s externalizing behaviors in a national sample of White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian American Families. Child Development, 83, 838–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Sims J Straus MA, & Sugarman DB (1995). Child, maternal and family characteristics associated with spanking. Family Relations, 44(2), 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, & Goodnow JJ (1994). Impact of parental discipline methods on the child’s internalization of values: A reconceptualization of current points of view. Developmental Psychology, 30, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, Rudy D, & Martini T (1997). Parenting cognitions and child constructs: An overview and implications for children’s internalization of values. In Grusec JE & Kuczynski L (Eds.), Parenting and children’s internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory (pp. 259–282). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnoe ML & Mariner CL (1997). Toward a developmental contextual model of the effects of parental spanking on children’s aggression. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 151, 768–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth L, & Ispa J (2012). Mexican parenting questionnaire. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 34(2), 232–250. [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth L, Ispa J, & Rudy D (2006). Parental control in Latino families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Development, 77, 1282–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness S, Super CM, & Keefer CH (1992). Learning to be an American parent: How cultural models gain directive force. In D’Andrade RG & Strauss C (Eds.), Publications of the Society for Psychological Anthropology. Human motives and cultural models (pp. 163–178). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hashima PY, & Amato PR (1994). Poverty, social support, ad parental behavior. Child Development, 65, 394–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill N, Bush K, & Roosa M (2003). Parenting and family socialization strategies and children’s mental health: Low-income Mexican American and Euro-American mothers and children. Child Development, 74,189–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ispa JM, & Halgunseth LC (2004). Talking about corporal punishment: nine low-income African American mothers’ perspectives. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 19, 463–484. [Google Scholar]

- Ispa JM, Fine MA, Halgunseth LC, Harper S, Robinson J, Boyce L, Brooks-Gunn J, & Brady-Smith C (2004). Maternal intrusiveness, maternal warmth, and mother-toddler relationship outcomes: Variations across low-income ethnic and acculturation groups. Child Development, 75, 1613–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Virdin LM, & Roosa M (1994). Socialization and family correlates of mental health outcomes among Hispanic and Anglo American children: Consideration of cross-ethnic scalar equivalence. Child Development, 65, 212–224. doi: 10.2307/1131376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Chang L, Dodge KA, Malone PS, Oburu P, Palmérus K, et al. (2005). Physical discipline and children’s adjustment: Cultural normativeness as a moderator. Child Development, 76, 1234–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00847.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Wager LB, Bates JE, Pettit GS, & Dodge KA (2012). Forms of spanking and children’s externalizing behavior. Family Relations, 61, 224–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larzelere RE, & Baumrind D (2010). Are spanking injunctions scientifically supported? Law & Contemporary Problems, 73(2), 57–57. [Google Scholar]

- Larzelere RE, & Kuhn BR (2005). Comparing child outcomes of physical punishment and alternative disciplinary tactics: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8, 1–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb ST, Leve LD, Harold GT, Neiderheiser JM, Shaw DS, & Ge X (2011). Trajectories of parenting and child negative emotionality during infancy and toddlerhood: A longitudinal analysis. Child Development, 82, 1661–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R, & Rubin D (2002). Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, & Martin JA (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In Mussen PH (Series Ed.) & Hetherington EM (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol 4. Socialization, personality and social development (4th ed., pp. 1–101) New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Waldfogel J, & Brooks-Gunn J (2012). Corporal punishment and child behavioural and cognitive outcomes through 5 years of age: Evidence from a contemporary urban birth cohort study. Infant and Child Development,21(3), 3–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Brooks-Gunn J, & Waldfogel J (2011). Who spanks infants and toddlers? Evidence from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing study. Children & Youth Services Review, 33 (8), 1364–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Jack K, Gromoske AN, & Berger LM (2012). Spanking and child development during the first 5 years of life. Child Development,83(6),1960–1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Gardner M, & Brooks-Gunn J (2012). The mediated and moderated effects of family support on child maltreatment. Journal of Family Issues, 33(7), 920–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee L, Roland E, Coffelt N, Olson AL, Forehand R, Massari C, et al. (2007). Harsh discipline and child problem behaviors: The roles of positive parenting and gender. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 187–196. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9070-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, & Smith J (2002). Physical discipline and behavioral problems in African American, European American, and Hispanic children: Emotional support as a moderator. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 40–53 doi: 10.1111/j.17413737.2002.00040.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczyk R, Bredehorst M, Khelaifat N, Maier C, & Maxwell E (2007). Correlates of depressive symptoms among Latino and Non-Latino White adolescents: Findings from the 2003 California Health Interview Survey. BMC Public Health, 7:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphey D, Guzman L, & Torres A (2014). America’s Hispanic Children: Gaining ground, looking forward. Retrieved from ChildTrends website: http://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/2014-38AmericaHispanicChildren.pdf

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Parenting Matters: Supporting Parents of Children Ages 0–8. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/21868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Cardona J, Holtrop K, Córdova D Jr., Escobar-Chew A, Horsford S, Tams L, et al. (2009). “Queremos aprender”: Latino immigrants call to integrate cultural adaptation with best practice knowledge in a parenting intervention. Family Process, 48, 211–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pina AA, & Silverman WK (2004). Clinical phenomenology, somatic symptoms, and distress in Hispanic/Latino and European American youths with anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 33, 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelow HM, Weaver SR, Bowman MA, & Swenson RB (2010). Predictors of parenting among economically disadvantaged Latina mothers: Mediating and moderating factors. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(7), 858–873. 10.1002/jcop.20400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Regalado M, Sareen H, Inkelas M, Wissow LS, & Halfon N (2004) Parents’ discipline of young children: Results from the National Survey of Early Childhood Health. Pediatrics, 113, 1952–1958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, & Kamphaus RW (2004). BASC 2, Behavior assessment system for children. American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, & Hart CH (1995). Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports, 77, 819–830. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez BL, & Olswang L (2003). Mexican-American and Anglo-American mothers’ beliefs about child rearing, education, and language impairment. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12, 452–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. (2011). Base SAS ® 9.3 Procedures Guide. Cary, NC: Copyright © 2011, SAS Institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Villar M, Huang KY, & Calzada EJ (2017). Social Support, Parenting, and Social Emotional Development in Young Mexican and Dominican American Children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 48(4), 597–609. DOI: 10.1007/s10578-016-0685-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, & Phillips DA (Eds.). (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Lin K, Gordon LC, Brody GH, Murry V, & Conger RD (2002). Community Differences in the Association Between Parenting Practices and Child Conduct Problems. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2), 331–345. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JR, & Brooks-Gunn J (1997). Correlates and consequences of harsh discipline for young children. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 151, 777–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Rose RA, Evans CB, Cotter KL, Bower M, & Bacallao M (2014). Familial influences on internalizing symptomatology in Latino adolescents: An ecological analysis of parent mental health and acculturation dynamics. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 1191–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacks AM, Oshio T, Gerard J, & Roe J (2009). The moderating effect of parental warmth on the association between spanking and child aggression: A longitudinal approach. Infant and Child Development, 18, 178–194. doi: 10.1002/icd.596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, & Stewart JH (1999). Corporal punishment by American parents: National data on prevalence, chronicity, severity, and duration in relation to child and family characteristics. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2, 55–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CA, Hamvas L, & Paris R (2011). Perceived instrumentality and normativeness of corporal punishment use among Black mothers. Family Relations, 60 (1), 60–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]