Abstract

Alginate is a polysaccharide composed of β-d-mannuronic acid (M) and α-l-guluronic acid (G). An Azotobacter vinelandii alginate lyase gene, algL, was cloned, sequenced, and expressed in Escherichia coli. The deduced molecular mass of the corresponding protein is 41.4 kDa, but a signal peptide is cleaved off, leaving a mature protein of 39 kDa. Sixty-three percent of the amino acids in this mature protein are identical to those in AlgL from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. AlgL was partially purified, and the activity was found to be optimal at a pH of 8.1 to 8.4 and at 0.35 M NaCl. Divalent cations are not necessary for activity. The pI of the enzyme is 5.1. When an alginate rich in mannuronic acid was used as the substrate, the Km was found to be 4.6 × 10−4 M (sugar residues). AlgL was found to cleave M-M and M-G bonds but not G-M or G-G bonds. Bonds involving acetylated residues were also cleaved, but this activity may be sensitive to the extent of acetylation.

Alginate is a family of 1-4-linked copolymers of β-d-mannuronic acid (M) and α-l-guluronic acid (G). It is produced by brown algae and by some bacteria belonging to the genera Azotobacter and Pseudomonas (8, 17, 18, 31). The polymer is widely used in industry and biotechnology (36, 44), and the genetics of its biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa has been extensively studied due to its role in the disease cystic fibrosis (33). In bacterial alginates, some of the M residues may be O-2- and/or O-3-acetylated (42). The polymer is initially synthesized as mannuronan, and the G residues are introduced at the polymer level by mannuronan C-5-epimerases (13, 22, 23). The epimerized alginates contain a mixture of blocks of consecutive G residues (G blocks), consecutive M residues (M blocks), and alternating M and G residues (MG blocks). Alginates from Pseudomonas sp. do not contain G blocks (42).

Alginate lyases catalyze the depolymerization of alginates by β-elimination, generating a molecule containing 4-deoxy-l-erythro-hex-4-enepyranosyluronate at the nonreducing end. Such lyases have been found in organisms using alginate as a carbon source, in bacteriophages specific for alginate-producing organisms, and in alginate-producing bacteria (45). An alginate molecule may contain four different glycosidic bonds, M-M, G-M, M-G, or G-G, and the relative rates at which each of these bonds are cleaved vary among different lyases (36a). The lyases also differ in the extent to which they are affected by acetylation (35, 43, 46).

Davidson et al. (10) described an Azotobacter vinelandii lyase which preferred M blocks as a substrate. Kennedy et al. (28) later reported the purification of periplasmic alginate lyases from A. vinelandii and from Azotobacter chroococcum which also seemed to prefer deacetylated, M-rich alginate. The activities of these enzymes were found to be optimal at pH 6.8 and 7.2, respectively, while the enzyme reported by Davidson et al. (10) was found to display optimal activity at pH 7.8.

A gene, algL, encoding an alginate lyase has been cloned from P. aeruginosa (2, 41). The gene was found to be located in a cluster containing most of the genes necessary for the biosynthesis of alginate. A homologous gene cluster has recently been identified in A. vinelandii (38) and shown to encode an alginate lyase (32). In our previous report, we showed that plasmid pHE102, which contains a part of this gene cluster, contains a DNA sequence sharing homology with algL from P. aeruginosa (38). We have now subcloned, sequenced, and expressed this gene in Escherichia coli. The lyase was shown to preferentially cleave deacetylated M-M and M-G bonds, but acetylated substrates were also cleaved.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

E. coli JM109 (48) was grown at 37°C in L broth or on L agar (40) supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) when relevant. The expression vector pTrc99A is a ColE1-based plasmid encoding β-lactamase and LacIq (1).

DNA manipulations and cloning.

Standard recombinant DNA procedures were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (40) except that transformations were carried out as specified by Chung et al. (7).

Alginates used in the study.

Sodium alginates for preparation of G blocks were isolated from the outer cortex of Laminaria hyperborea stipes. The G blocks (G-alginate) were prepared by acidic hydrolysis and fractionation as described by Haug et al. (21). A high-molecular-weight alginate enriched in mannuronic acid (M-alginate) was isolated from P. aeruginosa grown on agar plates at 18°C. This polymer was used both in its native O-acetylated form and after deacetylation as previously described (38). A low-molecular-weight M-alginate was obtained by a controlled depolymerization with acid (19) of the deacetylated M-alginate. An alginate with a high M content was also isolated from the intracellular substance of Aschophyllum nodosum fruiting bodies (FMI).

An alginate with a predominantly alternating structure, designated MG-alginate, was prepared from M-alginate by C-5-epimerization using the recombinantly produced epimerase AlgE4 (13). This yielded an alginate with 40% G and no G blocks. The compositions of the substrates are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Alginates used in this study

| Designation | Source | FM | FG | FMM | FMG | FGG | % Acetylation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mannuronan | Pseudomonas aeruginosa FRD462 (6), slightly degraded by acid hydrolysis | 1.0 | 0 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FMI | Ascophyllum nodosum (fruiting bodies) | 0.85 | 0.15 | NDa | ND | ND | 0 |

| M-alginate | P. aeruginosa 8830 (9), deacetylated | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 |

| MG-alginate | P. aeruginosa 8830 (9), epimerized by AlgE4 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0 | 0 |

| G-alginate | Laminaria hyperborea (stipe, degraded to DPn = 30) | 0.12 | 0.88 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.84 | 0 |

| Acetylated alginate | P. aeruginosa 8830 (9) | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0 | 48 |

ND, not determined.

Measurements of alginate lyase activity.

The unsaturated uronic acids which are generated by the lyases absorbs strongly at 230 nm, and this property was used to measure the alginate lyase activity (37). Unless otherwise stated, lyase was added to a mixture of alginate (1 mg/ml) and buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.1], 0.35 M NaCl) in a cuvette and mixed rapidly, and the absorbance at 230 nm was determined continuously. One unit was defined as the amount of enzyme which increased the absorbance by 1.0 absorbance unit per min.

Purification of AlgL.

JM109 (pHE113) was inoculated (1%) from overnight cultures into new, prewarmed medium and induced by 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) after 4 h. The cells were harvested 4 h after induction, resuspended in 1/10 volume of 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), and sonicated. After centrifugation at 10,800 × g for 30 min, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter and applied to a HiTrap Q ion-exchange column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with the same buffer. The proteins were eluted by a continuous NaCl gradient (0 to 1 M NaCl in 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5]), and the lyase activity was eluted at about 0.18 M NaCl. This fraction was adjusted to 1 M (NH4)2SO4 and applied to a HiTrap Phenyl Sepharose 6 Fast Flow (Low Sub) column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–1 M (NH4)2SO4. The lyase activity was eluted in the void, while most other proteins were retained on the column. These void fractions were used in all characterizations of the enzyme. For measurements of the effect of ionic strength and of various divalent cations on lyase activity, the enzyme was first dialyzed extensively against sterile MilliQ water.

Visualization of AlgL by SDS-PAGE and determination of its N-terminal sequence.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (40). Cells of strain JM109 containing pHE113 were grown overnight in the presence of 1 mM IPTG and resuspended (10 times concentrated) in gel loading buffer. The expression level under these conditions was sufficiently high to allow direct protein blotting and N-terminal sequencing as previously described (12).

Determination of pI.

Strain JM109 (pHE113) was grown overnight in the presence of 1 mM IPTG, resuspended in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5) containing 50 mM NaCl, and disrupted in a French press. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation of the sample at 40,000 × g for 1 h. One milliliter of the supernatant was mixed with 1 ml of ampholyte (Bio-Lyte 3/10; Bio-Rad) and 18 ml of Tris-HCl (5 mM, pH 7.5) containing 10 mM KCl and applied to a Rotofor system (Bio-Rad). Isoelectric focusing was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The fraction containing the lyase was refocused by using Biolyte 5/7.

Determination of Km.

The kinetics of the lyase was measured by using 18 different concentrations of M-alginate ranging from 4.6 × 10−5 M to 4.6 × 10−3 M (sugar residues; the molecular weight of the sugar residues in hydrated sodium alginate is 216). The Km was then determined by using the program hyper.exe 1.1s (11).

1H NMR of alginates degraded by AlgL.

Twenty milligrams of alginate in a volume of 20 ml of buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.1], 0.35 M NaCl) was mixed with 1.3 U of enzyme activity and incubated for 24 h. The reactions were stopped by freezing. Both substrates and products were analyzed by high-field 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy at 90°C, using a Bruker AM-300 (300-MHz) spectrometer. 3-(Trimethylsilyl)propanesulfonate was used as an internal standard in the samples. Prior to the NMR spectroscopy, the samples were desalted on Bio-Gel P-4 (Bio-Rad), freeze-dried, and dissolved in D2O. The removal of salt resulted in a better signal-to-noise ratio. The composition, given as the molar fraction of the monomers G (FG) and M (FM), the dyads (FGG, FMG, FGM, and FMM), and the G-centered triads (FGGG, FMGM, FMGG, and FGGM), was determined from the spectra as described by Grasdalen et al. (19). In this procedure, the area under each peak, which is proportional to the amount of residues giving rise to the signal, is used to calculate the above parameters. From the NMR spectra, we could also identify the resonance signals from the reducing ends as well as the uronic acid residue adjacent to the unsaturated nonreducing end generated by the lyase (24, 25). The degree of polymerization (DPn) was estimated from the relative intensities of the end signals and are generally calculated by DPn = (IG-1 + IM-1 + Iends)/Ired ends. For the lyase-degraded oligomers, only the β-anomeric signal can be seen due to overlap of the α signals by the unsaturated nonreducing ends (ΔM-1 and ΔG-1), and the ends are calculated by summing the contributions from reducing (red) and nonreducing ends. This yields DPn = (IΔG-1 + IΔM-1 + IM-1 + IG-1 + IMred + IGred)/[(IΔG-1 + IΔM-1 + IMred + IGred)/2].

DNA sequencing.

The insert of pHE113 was sequenced at the Biotechnology Center at the University of Oslo.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The algL nucleotide sequence data were deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF037600.

RESULTS

Subcloning and sequencing of an alginate lyase gene.

Restriction mapping of the insert in pHE102 combined with the sequencing of a part of this insert (38) showed that the putative algL gene probably was located on a 1.1-kb NcoI-BamHI fragment. This fragment was subcloned into pTrc99, generating pHE113. The insert in pHE113 was sequenced and found to contain an open reading frame of 1,122 nucleotides, putatively encoding a polypeptide with a molecular mass of 41.4 kDa. Comparison of the amino acid sequence of this deduced polypeptide with that of the mature form of AlgL from P. aeruginosa showed that these proteins are 63% identical. We therefore designated the A. vinelandii gene algL.

Expression of AlgL in E. coli.

The sequence of the insert in pHE113 contains termination codons (at the mRNA level) in all three reading frames just upstream of the putative start ATG; therefore, only the native protein can be made from this construct. SDS-PAGE of proteins from IPTG-induced cells containing pHE113 showed a dominant protein band corresponding to a molecular mass of about 39 kDa (Fig. 1, lane 1). N-terminal sequencing of the protein in this band provided the sequence AEALVPP, indicating that the protein is encoded by algL and that 23 amino acids were cleaved off from the N-terminal end in E. coli. The calculated molecular mass of the mature protein is 39 kDa, corresponding well to the value determined by denaturing gel electrophoresis. The pI of the lyase was found to be 5.1 by isoelectric focusing.

FIG. 1.

Purification of AlgL. Lane 1, induced cells; lane 2, active fraction from ion-exchange column; lane 3, void fraction from hydrophobic interaction column. Sizes are given in kilodaltons.

The lyase was partially purified, and the activity was measured with FMI as the substrate. After the ion-exchange column step, many contaminating proteins still remained (Fig. 1, lane 2), but the specific activity had increased from 1.25 to 7.5 U/mg of protein. The eluate from the hydrophobic column contains only two dominant proteins (Fig. 1, lane 3). N-terminal sequencing of these proteins showed that the 39-kDa protein was the lyase, while the other protein was apparently an unknown E. coli protein. This partially purified lyase (specific activity, 164 U/mg of protein) was used in the subsequent characterizations of the enzyme. During the purification process, 36% of the activity was retained.

Biochemical properties of AlgL.

The pH optimum for AlgL was found to be between 8.1 and 8.4, with about 50% activity at pH 6.7. These results are therefore similar to those reported by Davidson et al. (10) but higher than the pH optimum of 6.8 found by Kennedy et al. (28). This might indicate that A. vinelandii encodes more than one lyase or that different strains encode lyases with different optimal pH values. It was further found that the lyase needs about 0.35 M NaCl for optimal activity. At 0.1 and 1.0 M NaCl, only 8 and 5%, respectively, of maximum activity was retained. Based on these results, all subsequent enzyme incubations were carried out at pH 8.1 and in the presence of 0.35 M NaCl. The apparent Km of the enzyme was found to be 4.6 × 10−4 M (sugar residues) when M-alginate was used as the substrate. It has been shown that some lyases are activated or inhibited by divalent cations (20, 29), but the addition of 1 mM BaCl2, CaCl2, MgCl2, or Na2EDTA did not affect the activity of AlgL from A. vinelandii significantly. When Zn2+ was added, the activity of the enzyme was severely reduced (1 mM ZnCl2 reduced the activity to 7.6% of the control level without Zn2+ added, and even 0.1 mM Zn2+ reduced the activity to 61%).

Effects of different substrates on the activity of AlgL.

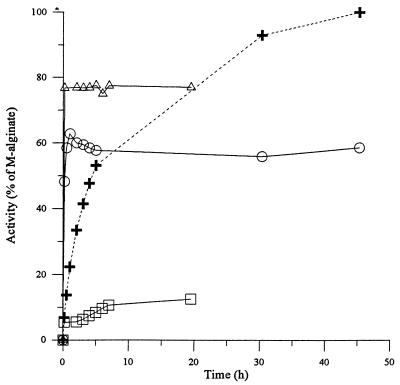

The substrate specificity of the lyase was first analyzed by incubating the enzyme with equal molar amounts (measured as sugar residues) of the different alginates, followed by measurements of the increase in absorbance at 230 nm. The absorbance data were recorded as optical density at 230 nm (OD230) until the degradation was complete. The acetylated alginate gave 77%, MG-alginate gave 60%, and G-alginate gave 12.6% of the activity of M-alginate (Fig. 2). This finding shows that AlgL is a mannuronate lyase which seems unable to cleave G-G bonds, as the observed low-level conversion of G-alginate is probably due to its content of M residues. The effect on MG-alginate seems to imply that either the M-G or G-M bond is cleaved very poorly or not at all, while the other bond is cleaved as efficiently as the M-M bond. If there had been a large difference in cleavage rate between the different bonds, the plot of the activity on MG-alginate relative to that of M-alginate would not have been horizontal but would have been expected to rise slowly with time. The results also show that AlgL is able to attack bonds where one of the residues is acetylated but may not be able to attack bonds linking two acetylated residues. This was unexpected, as the P. aeruginosa lyase showed nearly no activity against alginate with 10% acetylated alginate (30), while a previously characterized A. vinelandii enzyme had 41% activity on 37% acetylated alginate (28).

FIG. 2.

Activities of AlgL on G-alginate, (□), MG-alginate (○), and acetylated M-alginate (▵), given as percentages of the activity on M-alginate degraded for the same length of time. +, kinetics of double-bond formation with M-alginate of high molecular weight as the substrate plotted as percentage of full degradation (OD230 = 0.86, after 30 h of incubation, is used as 100%). The reactions were monitored until no further increase in OD230 was observed. The G-alginate and acetylated alginate were compared to partially hydrolyzed M-alginate, while the MG-alginate was compared to high-molecular-weight M-alginate.

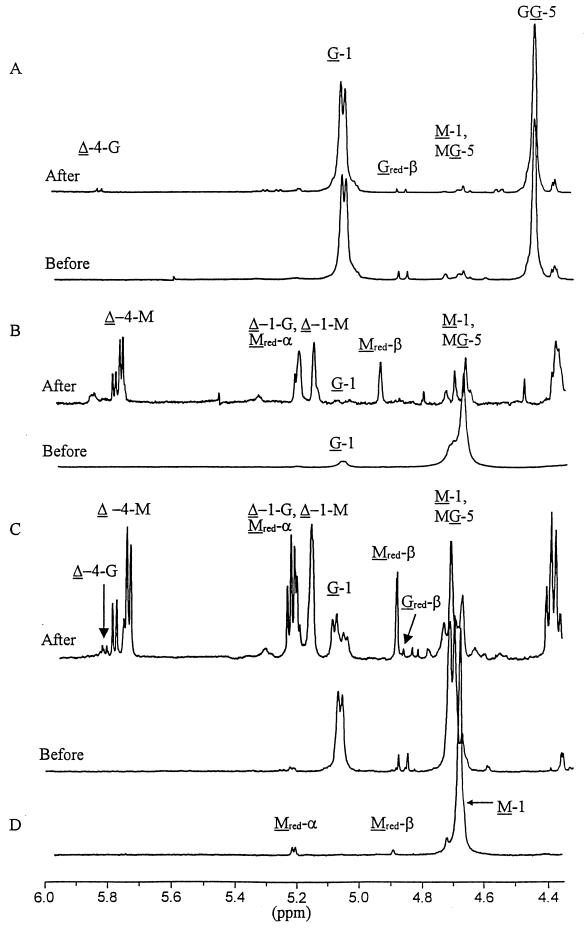

1H NMR studies on different alginates degraded by AlgL.

G-, M-, and MG-alginates were degraded with AlgL, desalted, and analyzed by NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 3). The very low peaks from the unsaturated ends in the spectrum of G-alginate treated with AlgL show that G blocks are not degraded by this enzyme (Fig. 3A), confirming the data shown in Fig. 2. M-alginate on the other hand, is degraded to oligouronides with an average chain length of 3 (Fig. 3B). The MG-alginate was used to distinguish between attack on M-G bonds and G-M bonds. Since this alginate does not contain any G-G bonds, the resulting spectrum (Fig. 3C) is easier to interpret. When an M-M bond is cleaved, the result will be an M on the reducing end (Mred) and ΔM or ΔG on the nonreducing end, where Δ denotes the 4-deoxy-l-erythro-hex-4-enepyranosyluronate residue. If an M-G bond is cleaved, the corresponding residues will be Mred and ΔM; if a G-M bond is cleaved, the products will be Gred and ΔG or ΔM. In the spectrum (Fig. 3C) of the lyase-degraded MG-alginate, the resonance signal arising from Mred-β at 4.90 predominates over Gred-β. Since the α/β ratio is 2.2 for M and only 0.2 for G (25), this indicates an almost exclusive splitting of the M-G glycosidic linkage. Moreover, the ratio Δ4-M/Δ4-G > 15 clearly indicate that AlgL is able to cleave M-G and M-M but not G-M linkages. Both the M-alginate and the MG-alginate were cleaved to an average DPn of 3, while the average DPn of the degraded G-alginate was 28.

FIG. 3.

The 1H NMR (400-MHz) spectra of solutions of oligouronates (10 mg/ml in D2O, at pD 6.8, 90°C) before and after enzymatic degradation by AlgL. (A) G-alginate; (B) M-alginate; (C) MG-alginate; (D) mannuronan (this spectrum was included to identify the signals from Mred). G, M, Gred, Mred, or Δ denotes signals from an internal G or M residue, reducing G or M residue, or the 4-deoxy-l-erythro-hex-4-enepyranosyluronate residue, respectively. The numbers denote which H is causing the signal, and the nonunderlined residues refer to the neighboring residue. The double peak between Δ-4-G and Δ-4-M in spectrum C is probably from the trimer Δ-4-M-Mred (25). The AlgL-degraded G- and MG-alginates were desalted before the NMR analyses. The M-alginate could not be desalted, as this led to an unacceptably high material loss. The high content of salt led to a shift toward somewhat higher parts-per-million values in this spectrum.

DISCUSSION

The occurrence of a lyase gene in the alginate biosynthesis gene cluster may indicate some function in the biosynthesis of alginate. It has been found that P. aeruginosa mutants lacking algL do not produce wild-type levels of alginate (34); this finding seems to support earlier hypotheses that AlgL from P. aeruginosa may have a function in generating short oligosaccharides which could be used as primers for new alginate chains or that it might participate in the determination of chain length (3). Similar functions might be envisioned for the A. vinelandii enzyme.

P. aeruginosa attaches to surfaces by a biofilm, and Boyd and Chakrabarty (3) have shown that overproduction of AlgL leads to an enhanced detachment of bacteria from the film. The release of the cells enables the bacterium to spread to new habitats. Azotobacter species are characterized by the ability to form metabolically dormant cysts in which the cells are surrounded by a protective coat containing alginate (39). It has also been proposed that an alginate lyase degrades the cyst coat during cyst germination (47), and Kennedy et al. (28) showed that the lyase activity increases at the start of germination. Even though algL from A. vinelandii is physically linked to the alginate biosynthesis gene cluster, synthesis of the enzyme is not dependent on the synthesis of alginate, as is the case for AlgL from P. aeruginosa (32). AlgL may therefore be involved in degradation of the cyst in addition to its proposed role in priming the biosynthesis of alginate and/or determining the polymer chain length. In that case, A. vinelandii must have some mechanism to export AlgL to the extracellular environment.

Chavagnat et al. (5) noted that AlgL from P. aeruginosa shares some homology with the lyase A1-III from a Sphingomonas sp. (49). This lyase has been reported to prefer acetylated bacterial alginate as a substrate (27). Three short stretches of extensive homology were identified between the three lyases (amino acids 114 to 129, 197 to 202, and 251 to 275 in the sequence of A. vinelandii AlgL). The second of these motifs ([I/C]NNHSY) is also present in the mannuronan C-5-epimerases AlgG from P. aeruginosa and A. vinelandii (15, 38), as FNNRSY and INNRTH, respectively. Furthermore, it is found twice in each A module of the five secreted epimerases from A. vinelandii (13) as ENNVS/AY and (S/T)NNVAY. It has been proposed that alginate lyases and epimerases have the first part of their reaction in common (16), and so this common motif might be a part of the active site or participate in binding of alginate.

Alginate lyases are commonly divided into G-specific and M-specific lyases, which are able to degrade G and M blocks, respectively. It has been more difficult to determine if the M-G bond or the G-M bond or both are degraded. Such an analysis has been performed for the G-specific lyase from Klebsiella aerogenes (24) and the M-specific lyase from Haliotis tuberculata (abalone) (24–26). The former was shown by NMR to attack both G-G and G-M bonds at about the same rate, while the latter prefers M-M bonds but is able to split G-M bonds, although at a lower rate. We show here that AlgL from A. vinelandii splits M-G and M-M bonds at about the same rate but does not seem to split G-G or G-M bonds. It should be noted that the use of an alginate fully epimerized by AlgE4 to a substrate containing only M blocks and MG blocks made the spectrum much easier to interpret than if an algal alginate with some G blocks had been used as a source for MG-alginate.

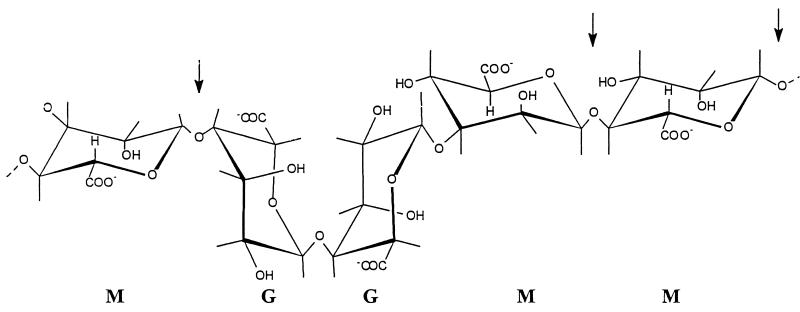

It seems that the abalone lyase recognizes the residue which will end up as the unsaturated end, while the bacterial enzymes recognize the residue which will become the reducing end. The bacterial lyases do not appear to have any clear preferences as to the residue from which the proton is to be removed, despite the conformational differences between M and G (Fig. 4). But since the products and also some of the proposed intermediates are the same (14), it is possible that the two studied bacterial lyases act by stabilizing the intermediate steps in the reaction.

FIG. 4.

Structures of the four different bonds in an alginate molecule. The bonds which are susceptible to AlgL are marked with arrows.

Integration of the NMR spectra shown in Fig. 3A indicated that both M-alginate and MG-alginate are degraded to about trimers, similar to what has been previously reported for other alginate lyases (4, 10, 20, 24, 26). We therefore propose that AlgL is able to cleave only M-M and M-G bonds, leaving trimers and tetramers as the main products when M-alginate and MG-alginate are used as substrates. This would imply that every second G in MG blocks is converted to an unsaturated residue, while each third M-residue in M blocks is converted. If this hypothesis is true, it is possible to calculate the FG after the degradation, provided that the frequencies of the different dyads of the substrate are known. The measured FGs from the spectra in Fig. 3 were 0.97, 0.05, and 0.26 for degraded G-alginate, M-alginate, and MG-alginate, respectively. The expected FGs in this model are 0.95, 0.04, and 0.27, which seems to indicate that the model is correct.

Alginate lyases can be used as a rapid way to characterize the composition of alginates (36a). M-specific lyases may also be used to generate G blocks in a more gentle way than by acid hydrolysis. Since it is easier to produce AlgL in E. coli than to isolate the lyase from abalone, AlgL seems to be a good alternative to the abalone enzyme for both of these applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Wenche Iren Strand for performing the NMR analyses and Knut Sletten, University of Oslo, for performing the N-terminal sequencing.

This work was supported by Pronova Biopolymers a.s. and by the Norwegian Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann E, Ochs B, Abel K-J. Tightly regulated tac promoter vectors useful for the expression of unfused and fused proteins in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1988;69:301–315. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90440-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd A, Ghosh M, May T B, Shinabarger D, Keogh R, Chakrabarty A M. Sequence of the algL gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and purification of its alginate lyase product. Gene. 1993;131:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90662-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd A, Chakrabarty A M. Role of alginate lyase in cell detachment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2355–2359. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2355-2359.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown B J, Preston J F. l-Guluronan-specific alginate lyase from a marine bacterium associated with Sargassum. Carbohydr Res. 1991;211:91–102. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(91)84148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chavagnat F, Duez C, Guinand M, Potin P, Barbeyron T, Henrissat B, Wallach J, Ghuysen J-M. Cloning, sequencing, and overexpression in Escherichia coli of the alginate-lyase-encoding aly gene of Pseudomonas alginovora: identification of three classes of alginate lyases. Biochem J. 1996;319:575–583. doi: 10.1042/bj3190575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chitnis C E, Ohman D E. Cloning of Pseudomonas aeruginosa algG, which controls alginate structure. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2894–2900. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.2894-2900.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung C T, Niemela S L, Miller R H. One-step preparation of competent Escherichia coli: transformation and storage of bacterial cells in the same solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2172–2175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cote G L, Krull L H. Characterization of the exocellular polysaccharides from Azotobacter chroococcum. Carbohydr Res. 1988;181:143–152. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darzins A, Chakrabarty A M. Cloning of genes controlling alginate biosynthesis from a mucoid cystic fibrosis isolate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:9–18. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.9-18.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson I W, Lawson C J, Sutherland I W. An alginate lyase from Azotobacter vinelandii phage. J Gen Microbiol. 1977;98:223–229. doi: 10.1099/00221287-98-1-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Easterby J S. Hyper.exe: hyperbolic regression analysis of enzyme kinetic data. 1996. http://www.liv.ac.uk/-jse/ Available at http://www.liv.ac.uk/-jse/. . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ertesvåg H, Doseth B, Larsen B, Skjåk-Bræk G, Valla S. Cloning and sequencing of an Azotobacter vinelandii mannuronan C-5-epimerase gene. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2846–2853. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2846-2853.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ertesvåg H, Høidal H K, Hals I H, Rian A, Doseth B, Valla S. A family of modular type mannuronan C-5-epimerase genes controls alginate structure in Azotobacter vinelandii. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:719–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feingold D S, Bentley R. Conformational aspects of the reaction mechanisms of polysaccharide lyases and epimerases. FEBS Lett. 1987;223:207–211. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franklin M J, Chitnis C E, Gacesa P, Sonesson A, White D C, Ohman D E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgG is a polymer level alginate C-5-mannuronan epimerase. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1821–1830. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1821-1830.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gacesa P. Alginate-modifying enzymes. A proposed unified mechanism of action for the lyases and epimerases. FEBS Lett. 1987;212:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorin P A J, Spencer J F T. Exocellular alginic acid from Azotobacter vinelandii. Can J Chem. 1966;44:993–998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Govan J R W, Fyfe J A M, Jarman T R. Isolation of alginate-producing mutants of Pseudomonas fluorescens, Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas mendocina. J Gen Microbiol. 1981;125:217–220. doi: 10.1099/00221287-125-1-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grasdalen H, Larsen B, Smidsrød O. A P.M.R. study of the composition and sequence of uronate residues in alginates. Carbohydr Res. 1979;68:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haraguchi K, Kodama T. Purification and properties of poly(β-d-mannuronate) lyase from Azotobacter chroococcum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;44:576–581. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haug A, Larsen B, Smidsrød O. Studies on the sequence of uronic acid residues in alginic acid. Acta Chem Scand. 1967;21:691–704. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haug A, Larsen B. Biosynthesis of alginate. Epimerisation of d-mannuronic to l-guluronic acid residues in the polymer chain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;192:557–559. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(69)90414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haug A, Larsen B. Biosynthesis of alginate. Part II. Polymannuronic acid C-5-epimerase from Azotobacter vinelandii (Lipman) Carbohydr Res. 1971;17:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)82537-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haugen F, Kortner F, Larsen B. Kinetics and specificity of alginate lyases. Part I, a case study. Carbohydr Res. 1990;198:101–109. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(90)84280-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heyraud A, Gey C, Leonard C, Rochas C, Girond S, Kloareg B. NMR spectroscopy analysis of oligoguluronates and oligomannuronates prepared by acid or enzymatic hydrolysis of homopolymeric blocks of alginic acid. Application to the determination of the substrate specificity of Haliotis tuberculata alginate lyase. Carbohydr Res. 1996;289:11–23. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(96)00060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heyraud A, Colin-Morel P, Girond S, Richard C, Kloareg B. HPLC analysis of saturated or unsaturated oligoguluronates and oligomannuronates. Application to the determination of Haliotis tuberculata alginate lyase. Carbohydr Res. 1996;291:115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(96)00138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hisano T, Nishimura M, Yamashita T, Sakaguchi K, Murata K. On the selfprocessing of bacterial alginate lyase. J Ferment Bioeng. 1994;78:109–110. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kennedy L, McDowell K, Sutherland I W. Alginases from Azotobacter species. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:2465–2471. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larsen B, Hoøien K, Østgaard K. Kinetics and specificity of alginate lyases. Hydrobiologia. 1993;260/261:557–561. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linker A, Evans L R. Isolation and characterization of an alginase from mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:958–964. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.3.958-964.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linker A, Jones R S. A polysaccharide resembling alginic acid from a Pseudomonas micro-organism. Nature. 1964;204:187–188. doi: 10.1038/204187a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lloret L, Barreto R, León R, Moreno S, Martínez-Salazar J, Espín G, Soberón-Chávez G. Genetic analysis of the transcriptional arrangement of Azotobacter vinelandii alginate biosynthetic genes: identification of two independent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:449–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.May T B, Chakrabarty A M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: genes and enzymes of alginate synthesis. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:151–157. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90664-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monday S R, Schiller N L. Alginate synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the role of AlgL (alginate lyase) and AlgX. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:625–632. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.625-632.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen L K, Schiller N L. Identification of a slime exopolysaccharide depolymerase in mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Curr Microbiol. 1989;18:323–329. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onsøyen E. Commercial applications of alginates. Carbohydr Eur. 1996;14:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 36a.Østgaard K. Enzymatic microassay for the determination and characterization of alginates. Carbohydr Polymers. 1992;19:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Preiss J, Ashwell G. Alginic acid metabolism in bacteria. I. Enzymatic formation of unsaturated oligosaccharides and 4-deoxy-l-erythro-5-hexoseulose uronic acid. J Biol Chem. 1961;237:309–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rehm B H, Ertesvåg H, Valla S. A new Azotobacter vinelandii mannuronan C-5-epimerase gene (algG) is part of an alg gene cluster physically organized in a manner similar to that in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5884–5889. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5884-5889.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sadoff H L. Encystment and germination in Azotobacter vinelandii. Bacteriol Rev. 1975;39:516–539. doi: 10.1128/br.39.4.516-539.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiller N L, Monday S R, Boyd C M, Keen N T, Ohman D E. Characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate lyase gene (algL): cloning, sequencing, and expression in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4780–4789. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4780-4789.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skjåk-Bræk G, Grasdalen H, Larsen B. Monomer sequence and acetylation pattern in some bacterial alginates. Carbohydr Res. 1986;154:239–250. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skjåk-Bræk G, Paoletti S, Gianferrara T. Selective acetylation of mannuronic acid residues in calcium alginate gels. Carbohydr Res. 1989;185:119–129. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skjåk-Bræk G, Espevik T. Application of alginate gels in biotechnology and biomedicine. Carbohydr Eur. 1996;14:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sutherland I W. Polysaccharide lyases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1995;16:323–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1995.tb00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutherland I W, Keen G A. Alginases from Beneckea pelagia and Pseudomonas spp. J Appl Biochem. 1981;3:48–57. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wyss O, Neumann M G, Socolofsky M D. Development and germination of the Azotobacter cyst. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1961;10:555–565. doi: 10.1083/jcb.10.4.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yonemoto Y, Tanaka H, Hisano T, Sakaguchi K, Abe S, Yamashita T, Kimura A, Murata K. Bacterial alginate lysae gene: nucleotide sequence and molecular route for generation of alginate lyase species. J Ferment Bioeng. 1993;75:336–342. [Google Scholar]