Abstract

Biosynthesis of di-myo-inositol-1,1′-phosphate (DIP) is proposed to occur with myo-inositol and myo-inositol 1-phosphate (I-1-P) used as precursors. Activation of the I-1-P with CTP and condensation of the resultant CDP-inositol (CDP-I) with myo-inositol then generates DIP. The sole known biosynthetic pathway of inositol in all organisms is the conversion of d-glucose-6-phosphate to myo-inositol. This conversion requires two key enzymes: l-I-1-P synthase and I-1-P phosphatase. Enzymatic assays using 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy as well as a colorimetric assay for inorganic phosphate have confirmed the occurrence of l-I-1-P synthase and a moderately specific I-1-P phosphatase. The enzymatic reaction that couples CDP-I with myo-inositol to generate DIP has also been detected in Methanococcus igneus. 13C labeling studies with [2,3-13C]pyruvate and [3-13C]pyruvate were used to examine this pathway in M. igneus. Label distribution in DIP was consistent with inositol units formed from glucose-6-phosphate, but the label in the glucose moiety was scrambled via transketolase and transaldolase activities of the pentose phosphate pathway.

Di-myo-inositol-1,1′-phosphate (DIP) is an unusual inositol derivative that has been identified as a major solute in hyperthermophilic archaea including Pyrococcus woesei (22), Pyrococcus furiosus (16), Methanococcus igneus (5), and several eubacteria of the order Thermotogales (15). Intracellular DIP increases with increasing extracellular concentrations of NaCl in both M. igneus (5) and P. furiosus (16). DIP also increases dramatically at supraoptimal growth temperatures (>80°C for M. igneus and 98 to 101°C for P. furiosus). The unusual intracellular high concentration of K+ ions and the extreme optimal growth temperatures (100 to 104°C) of P. woesei (30) suggested the role of DIP as a main counterion of K+ with a possible thermostabilizing action. Scholz et al. (22) demonstrated that among several salts, the potassium salt of DIP provided optimum enzyme stabilization when the activity of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of P. woesei was tested at 105°C under anaerobic conditions.

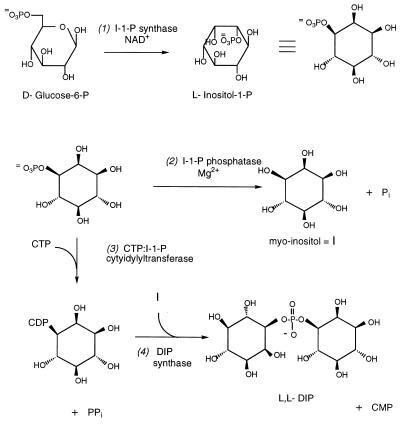

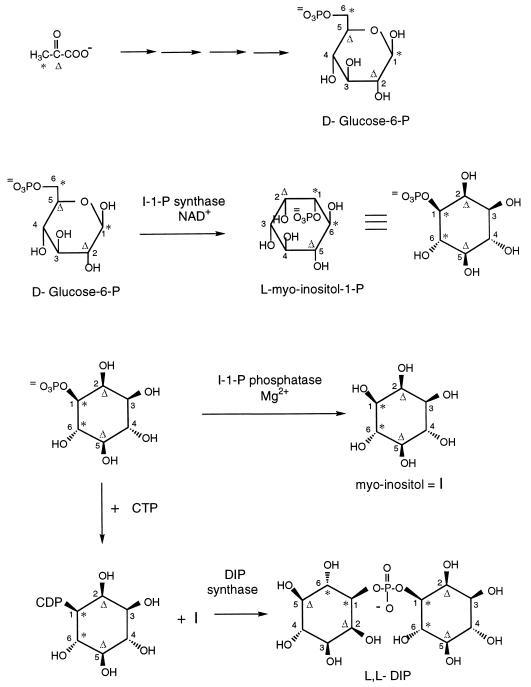

Since de novo synthesis of DIP occurs in response to external levels of NaCl and temperature, there must be regulatory biosynthetic mechanisms linked to osmotic pressure and temperature. To study the regulation, the enzymes and/or other proteins responsible for synthesis of this compatible solute must be isolated. This requires knowledge of the biosynthetic pathways involved in the synthesis of DIP. The sole known pathway for inositol biosynthesis in all other organisms is the conversion of d-glucose-6-phosphate to l-myo-inositol 1-phosphate (l-I-1-P) via l-myo-inositol 1-monophosphate (I-1-P) synthase and hydrolysis of I-1-P to myo-inositol via a specific phosphatase, I-1-P phosphatase (13, 14). Similar enzymes are likely to exist in methanogens. A logical pathway for the biosynthesis of DIP would then use myo-inositol and I-1-P as precursors. Activation of the I-1-P with CTP and condensation of the resultant CDP-inositol (CDP-I) with myo-inositol would generate DIP. As summarized in Fig. 1, DIP biosynthesis requires four key enzymes: I-1-P synthase (step 1), I-1-P phosphatase (step 2), CTP:I-1-P cytidylyltransferase (step 3), and DIP synthase (step 4). The enzymes that catalyze steps 1 and 2 have been well studied in plants, yeasts, and mammalian tissues. However, the enzymes invoked for steps 3 and 4 are novel activities, although based on similar chemical transformations in cells.

FIG. 1.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway for DIP showing the four key enzymatic activities. Based on similar transformations in other organisms, cofactors are indicated for several of the steps.

This work describes the use of 31P nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and colorimetric assays to verify the existence of three of these activities in cell extracts of M. igneus. Specific labeling of DIP with [13C]pyruvate was also used to probe the DIP biosynthetic pathway. The pattern of 13C label incorporation from [3-13C]pyruvate and [2,3-13C]pyruvate coupled with the known stereochemistry of DIP provided evidence that M. igneus also has enzymes of the pentose phosphate pathway (transaldolase and transketolase) that scramble label in glucose-6-phosphate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

The sodium salts of [2,3-13C]pyruvate and [1-313C]pyruvate were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. d-Glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P) disodium salt, I-1-P cyclohexylammonium salt (2-monophosphate isomer content, 27%), fructose-6-phosphate (F-6-P), β-glycerophosphate, NAD+, CTP, CMP-morpholidate, and D2O were obtained from Sigma. Ammonium sulfate and myo-inositol were obtained from Aldrich. CDP-I was chemically synthesized by the method of Roseman et al. (21) for nucleotide coenzymes. CMP-morpholidate and the trioctylamine salt of I-1-P (prepared by cation-exchange chromatography) were incubated in anhydrous pyridine. The CDP-I products (including the CDP adducts at C-1 of l-inositol and d-inositol as well as the CDP-I with the C-2 hydroxyl of inositol in the pyrophosphate bond) precipitated out of the pyridine solution. The precipitate was collected and purified by anion-exchange chromatography. The final mixture contained the CDP-I isomers, a small amount of UMP that cochromatographed with the pyrophosphate diesters, and the self-condensation product, di-cytidine-5,5′-pyrophosphate (DCPP), of CMP-morpholidate as monitored by 31P NMR spectroscopy. A 1H-1H total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) NMR experiment was used to confirm the presence of the inositol ring in CDP-I.

Cell growth and 13C labeling.

M. igneus cell cultures were grown at 85°C in modified MGG medium (5) containing 0.3 M NaCl under an H2-CO2 (4:1) atmosphere. The pH of the medium was adjusted to a slightly acidic value (6.8 to 6.9) prior to sterilization by autoclaving. Once cells reached an optical density of 0.6 at 660 nm, they were harvested by centrifugation at 9,000 rpm for 30 min in a Sorvall centrifuge. Cell pellets were either (i) extracted three to five times with 70% ethanol (this lyses cells and precipitates protein and other macromolecular debris, leaving only small molecules in solution) as described previously (20) to prepare extracts containing DIP or (ii) resuspended and lysed by sonication (see below) to yield a cell-free protein extract. For 13C labeling experiments, 0.15 M stock solutions of the sodium salts of [2,3-13C]pyruvate and [3-13C]pyruvate, each enriched with 99% 13C, were made anaerobic by pressurizing for 10 s with argon (10 lb/in2) followed by 3 min of vacuum and repetition of the procedure three times. Because of the high growth temperature (85°C) and limited stability of pyruvate, the labeled sodium pyruvate was injected into M. igneus cultures (150 ml per bottle) in multiple doses of ∼4 ml/h during exponential growth phase (a total of two or three injections) to ensure maximum uptake and utilization of the compound.

Isolation of DIP.

Fifty milligrams of an M. igneus ethanol extract (prepared by incubating the cell pellet with 5 ml of 70% ethanol, centrifuging the sample, reextracting the pellet with ethanol three or more times, combining the ethanol fractions, and evaporating the solvent [20]) was dissolved in 2 ml of doubly distilled water. The solution pH was adjusted to 6.5 to 7.0 with HCl. The sample was then loaded onto a QAE-Sephadex (Sigma) column (bed volume, 15 ml) equilibrated with 50 mM ammonium acetate (pH 6.8). The column was eluted with 45 ml of 50 mM ammonium acetate. Fractions of 3 ml were collected, and 1-ml aliquots of these fractions were lyophilized, dissolved in D2O, and analyzed by 1H NMR. Fractions 8 to 11 containing pure DIP were pooled, lyophilized, and used for determination of optical activity of DIP.

Cell-free protein extracts.

Since there was no apparent requirement for oxygen-sensitive cofactors in the DIP synthase enzymes, all protein extracts were made under aerobic conditions with the exception of extracts for assays of CDP-I synthase. An intact cell pellet (∼1.0 g) was resuspended in 10 ml of standard buffer (50 mM Tris acetate, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol [pH 8.0]). The cells were lysed by sonication using a 30-s pulse–30-s off cycle repeated 10 times. The extract was then centrifuged at 9,000 rpm for 20 min to remove the cell debris. To the supernatant, solid ammonium sulfate was slowly added to 44% saturation. After a 20-min incubation, the suspension was centrifuged at 17,000 rpm. The precipitate was dissolved in standard buffer; this fraction is designated the 0 to 44% ammonium sulfate fraction. Solid ammonium sulfate was added to the supernatant to 85% saturation, and the precipitated protein was centrifuged and redissolved in standard buffer (the 44 to 85% ammonium sulfate protein fraction). A later fractionation used a 60 to 75% ammonium sulfate fraction for verification of I-1-P synthase activity. Ammonium sulfate fractions were dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 1,000 volumes of standard buffer. These protein fractions were used immediately or quickly frozen on dry ice and stored at −20°C.

In vitro assays for I-1-P, inositol, and DIP biosynthesis.

Two different methods, 31P NMR spectroscopy and a colorimetric inositol monophosphate assay (1), were used to measure the formation of I-1-P. The 31P NMR assays monitored substrate (G-6-P) conversion to I-1-P. The assay mixtures (0.5 ml) contained 5 mM G-6-P, 1 mM NAD+, 15 mM NH4Cl, 50 mM Tris acetate (pH 8.0), 50 μl of enzyme extract, and 20% D2O (for the spectrometer lock). Samples were incubated at 37°C for 38 h, 55°C for 16 h, and 85°C for 2 to 4 h. Good signal-to-noise spectra were acquired within 30 min, and at room temperature (<25°C) no significant product was generated during this time period. The ammonium sulfate fraction also contained G-6-P isomerase activity, which converts G-6-P to F-6-P. All of these different phosphorylated compounds gave rise to distinct resonances in the 31P NMR spectrum (Fig. 1) that could be easily distinguished on the basis of chemical shift and 1H coupling pattern (the -CH2OPO3= unit yields a triplet for each anomer of G-6-P [these overlap to form an asymmetric quartet] with JHP ∼ 6.0 Hz and a triplet for F-6-P with JHP ∼ 5.0 Hz, while the -CHOPO3= of I-1-P occurs as a doublet with JHP ∼ 8.5 Hz). The 31P spectrum in Fig. 1 has not been 1H decoupled to emphasize the different 1H-31P coupling patterns for substrates, products, and side reactions. The I-1-P doublet is about 0.47 ppm upfield of those for G-6-P and 0.14 ppm downfield of F-6-P in the pH range of 7.5 to 8.5. Confirmation of the identity of a 31P resonance as belonging to a particular phosphorylated compound was also provided by the pH dependence of the 31P chemical shift and comparison to known phosphate compounds. Some of an authentic sugar phosphate thought to be responsible for a given resonance was added to the in vitro assay mixture at room temperature. If the added species augmented a resonance observed in the sample (i.e., if the two gave rise to intensity at the same chemical shift), and if this persisted over a wide range of pH values (i.e., only a single peak is observed and not two separate resonances over a wide pH range), the sugar phosphate in the sample was likely to be the known compound. It is highly unlikely that two phosphorylated sugars would have the same chemical shifts and identical pKas. Thus, in identifying products in these in vitro assays, 31P spectra were examined over a range of pH values in the absence and presence of known sugar phosphates. The JHP coupling constants are also characteristic of different sugar compounds and aided in identification of phosphates (e.g., JHP = 6 Hz for G-6-P, JHP = 5 Hz for F-6-P, and JHP = 8.5 Hz for I-1-P).

A colorimetric assay was also used to monitor I-1-P synthase activity. The periodate procedure of Barnett et al. (1) is based on the sensitivity of I-1-P to oxidation by periodate. Substrate G-6-P and its isomerization product, F-6-P, are not sensitive to periodate hydrolysis. The assay conditions were the same as for 31P NMR spectroscopic assays except that the total volume of the incubation mixture was reduced to 60 μl (this volume provided enough material for four separate assays) and incubation times were typically less than 1 h. After incubation of the assay mixture, 20% trichloroacetic acid (30 μl) was added and the mixture was centrifuged. Eight aliquots (10 μl) of supernatant were diluted to 100 μl. Four of these were incubated with 100 μl of 0.2 M NaIO4 at 37°C for 1 h; the other four samples were incubated with 100 μl of water as controls. After the periodate incubation, 100 μl of freshly prepared 1 M Na2SO3 and then 200 μl of water were added to each sample. Pi liberated by the periodate oxidation was quantified by colorimetric phosphate assay using ammonium molybdate malachite green reagents. Absorbances were measured at 660 nm and converted to phosphate concentrations by using a KH2PO4 standard calibration curve. The assay with NaIO4 added gave the total amount of phosphate that came from both the I-1-P synthase and phosphatase activities, while the control assay gave only the Pi produced via phosphatase activity. The difference in these assays (averaged for the four parallel assays) corresponded to the I-1-P synthase activity.

The inositol monophosphatase assay mixture (0.5 ml) contained 2 mM I-1-P, 4 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris acetate (pH 8.0), 50 μl of enzyme extract, and 20% D2O. For 31P NMR assays, the reaction mixture was incubated at 55°C overnight (16 h) or at 85°C for 2 to 4 h. Considerably shorter incubation times were used for the colorimetric phosphate assay using ammonium molybdate malachite green reagents. G-6-P was also used in place of I-1-P in the assay mixture to check for nonspecific phosphatase activity.

DIP synthase assay mixtures contained 50 μl of CDP-I stock solution (20 to 30 mM), 300 μl of cell extract (protein content, ∼1 mg/ml) dialyzed against 100 mM Tris buffer with 10 mM MgCl2, 100 μl of D2O, and 25 μl of 100 mM myo-inositol. The mixture was incubated at 65 or 75°C for 2 to 3 h. High temperatures or longer incubation times failed to increase DIP production due to the denaturation of protein under these conditions. DIP was identified by 31P NMR spectroscopy both of crude reaction mixtures and of a sample purified by QAE-Sephadex chromatography.

NMR spectroscopy.

1H WALTZ-decoupled 13C NMR (125.7-MHz) spectra of ethanol extracts were obtained by using a Varian Unity 500 spectrometer and a 5-mm broadband probe. Samples were dissolved in 0.5 ml of D2O. 13C spectral accumulation parameters included 25,000-Hz sweep width, 65,024 datum points, 90° pulse width (11 μs), and a 1.0-s delay time between acquisitions. Typically, 20,000 to 28,000 transients were acquired, and the free induction decays were processed with 2-Hz line broadening. The absolute amounts of 13C incorporated into DIP carbons in extracts from samples incubated with [3-13C]pyruvate were estimated by comparing 1H intensities and 13C intensities for DIP and the glutamate isomers. The reductive partial tricarboxylic acid cycle used by this organism labels l-α-glutamate at C-3 and C-4 but not at C-2. The intensities of the DIP carbons were compared to that of l-α-glutamate C-2. The bulk ratio of DIP to l-α-glutamate was then obtained from the 1H NMR spectrum of the extract and was used to obtain enrichment levels for the DIP carbons.

31P NMR spectra, used to monitor synthesis of phosphorylated intermediates and products in the DIP pathway, were obtained on the same spectrometer (202.3 MHz) as well as on a Varian Unity 300 system (121.4 MHz). Parameters used on the Unity 500 system include 8,720-Hz sweep width, 27,840 datum points, 90° pulse width, and a 1.0-s delay time between acquisitions. Typically, 256 to 512 transients were acquired, and the FIDs were processed with 1- to 10-Hz line broadening. Acquisition parameters used on the Unity 300 include 5,272-Hz sweep width, 14,656 datum points, 90° pulse width, and a 1.0-s delay time between acquisitions. 31P-1H heteronuclear correlation spectroscopy (HETCOR) experiments were performed with standard Varian software. Samples were not spun, and residual water was suppressed by presaturation for two-dimensional experiments. This experiment was used to correlate the CDP-I and DIP 31P chemical shifts with the nearby proton to which they are coupled. Data acquisition and processing parameters were as follows: sweep widths of 8,720 Hz in the 31P frequency range and 5,034 Hz in the 1H frequency range, 1,024 scans per t1 increment, a JPH of 8.0 Hz used to determine increments in t1, 1H decoupling during acquisition only, and 1,024 × 128 raw data matrix size zero-filled to 1,024 in t1.

1H NMR spectra were acquired with the Varian Unity 500 spectrometer using a 5-mm indirect probe. The 1H-1H TOCSY experiment was performed with standard Varian software and spin-locking incorporated into the pulse sequence. This experiment was used to identify the six 1H chemical shifts of the inositol ring in DIP and in CDP-I. Data acquisition and processing parameters included a sweep width of 5,000 Hz, 96 scans per t1 increment, and 2,048 × 256 raw data matrix size zero-filled to 1,024 in t1.

RESULTS

Chirality of DIP isolated from M. igneus.

The DIP synthesized by Pyrococcus species is chiral and has an l,l configuration of the inositols (26). However, it is possible that the DIP isolated from M. igneus is synthesized in a meso form (l,d configuration of inositols esterified at C-1, alternatively called di-myo-inositol-1,3-phosphate) or with a d,d configuration of the inositol units. Therefore, the optical activity of this compound was measured. Moderate amounts of DIP were separated from the α- and β-glutamate isomers in M. igneus ethanol extracts by anion-exchange chromatography on QAE-Sephadex (the DIP is not significantly retained by the column, whereas the two glutamate isomers stick). The specific rotation of this material (using a concentration of 8 mg/ml) was determined to be [α]d20 = 2.39°. This value can be compared to those for the three different optical isomers of DIP that have been synthesized: l,l, +2.4°; l,d, 0.0; and d,d, −2.8° (26). Thus, the DIP produced by the thermophilic methanogen has the same chirality (l,l) as the DIP produced by the archaeon Pyrococcus.

In vitro assays for enzymes of inositol biosynthesis.

31P NMR spectroscopy can be used to identify intermediates and products of inositol biosynthesis by monitoring the phosphorylated solutes produced from the incubation of known phosphocompounds (and appropriate cofactors) with protein extracts of M. igneus. The chemical shifts of substrates, products, and related compounds such as G-6-P (4.7 ppm), F-6-P (4.0 ppm), I-1-P (4.2 ppm), I-2-P (4.8 ppm), and Pi (2.6 ppm) are well separated and quite distinct from those for NAD+ (−9 to −11 ppm), a cofactor in the I-1-P synthase activity. Both I-1-P synthase and I-1-P phosphatase have been well studied in plants and other organisms (2, 6, 17, 24), and the data obtained provide a background for evaluating these activities in methanogen cell extracts. Two ammonium sulfate fractions (0 to 44% and 44 to 85%, the latter more tightly defined as a 60 to 75% fraction in later experiments) from lysed M. igneus showed evidence of these enzymes. A summary of the cofactors needed for the different reactions identified in the DIP biosynthetic pathway, enzyme specific activities in these relatively crude extracts, and estimated activation energies are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Activities of key enzymes in extracts of M. igneus

| Enzyme | Cofactor (addition) | Sp acta (nmol · min−1 · mg−1) | Activation energyb (kJ · mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I-1-P synthase | NAD+ | 5 | 60–70 |

| I-1-P phosphatase | Mg2+ | 2.3 | 54c |

| CTP:I-1-P cytidylyltransferase | ? | ? | |

| DIP synthase | |||

| 65°C | (Mg2+)d | 0.75 | 120 |

| 75°C | 2.6 |

Measured at 85°C (unless otherwise specified) in crude protein extracts prepared from M. igneus.

Estimated from the temperature dependence of the reaction rate measured in the crude protein extracts. The error is estimated to be ±10 kJ · mol−1 for DIP synthase.

Value measured for I-1-P phosphatase from M. jannaschii I-1-P phosphatase cloned in E. coli (3).

Included in assay mixes since it is often necessary for other cytidylyltransferases.

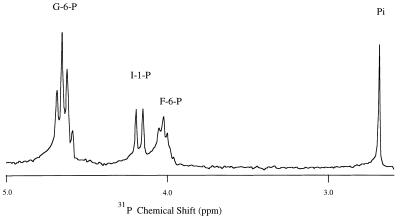

I-1-P synthase activity was detected in the 44 to 85% ammonium sulfate fraction (and in the purer 60 to 75% fraction) and could be monitored by 31P NMR spectroscopy or the colorimetric assay using periodate (1). Since this was a crude protein fraction, there was also a competing G-6-P isomerase reaction to produce F-6-P. However, the isomerase reaction rapidly reaches equilibrium at 37°C when starting with G-6-P or F-6-P (for the reverse direction of the G-6-P synthase). The production of I-1-P in assay mixtures containing G-6-P occurs only when NAD+ is added and only with the protein fraction precipitated with a higher concentration of ammonium sulfate. Mg2+ interferes with the synthesis of I-1-P by accelerating the hydrolysis of G-1-P, I-1-P, and NAD+ by Mg2+-dependent phosphatases. Therefore, this ion was not present in assays for I-1-P synthase. The observed I-1-P synthase in the M. igneus protein extracts differed from the plant and mammalian I-1-P synthase enzymes in two notable respects: its heat stability and its high activation energy. With the 31P assay, an incubation time of 38 h was necessary to detect I-1-P at 37°C; roughly three times as much I-1-P was produced in 16 h at 55°C. Incubation at 85°C for 1 h led to about the same amount of conversion of G-6-P to I-1-P as seen with the 38-h incubation at 37°C. At longer incubation times (4 h) at 85°C, the yield of I-1-P was significant (Fig. 2). At this temperature, the reaction was linear for about 1 h, with a 12% conversion of G-6-P to I-1-P during that time period. Similar I-1-P synthase specific activities were determined with the colorimetric assay. The estimated specific activity was about 5 nmol · min−1 · mg of protein−1, a value higher than that found for ammonium sulfate fractions of yeast (3.16 nmol · min−1 · mg−1 [24]) and pine pollen (0.07 nmol · min−1 · mg−1 [12]) but close to values obtained for Neurospora crassa (8.1 nmol · min−1 · mg−1 [8]), bovine testis (7 nmol · min−1 · mg−1 [17]), and rat testis (6.7 nmol · min−1 · mg−1 [6]). From the temperature dependence of the rates, an activation energy of about 70 kJ/mol was extracted for the methanogen I-1-P synthase.

FIG. 2.

1H-coupled 31P NMR spectrum (202.3 MHz) of an I-1-P synthase assay mixture containing 5 mM G-6-P, 1 mM NAD+, 50 mM Tris acetate (pH 8.2), and 100 μl of 60 to 75% ammonium sulfate protein extract that had been incubated at 85°C for 4 h. Note that only I-1-P is a doublet in the coupled spectrum.

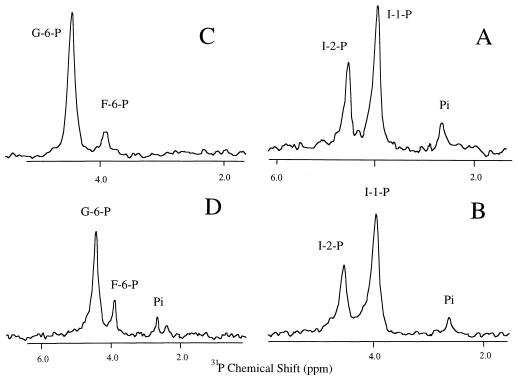

I-1-P phosphatase activity (which is Mg2+ dependent in other organisms) was detected at temperatures of 55°C or higher in the low-ammonium sulfate fraction (Fig. 3A shows the 1H-decoupled 31P spectrum of the reaction mixture). Commercial I-1-P was contaminated with I-2-P, but both 31P resonances were distinct from the product Pi. If the same assay mixture was incubated with G-6-P in place of I-1-P as a potential phosphatase substrate, minimal hydrolysis and production of Pi were observed with the 0 to 44% ammonium sulfate fraction, indicating this phosphatase activity had moderate specificity toward I-1-P (probably both d- and l isomers). As observed for plant enzymes, the I-1-P phosphatase activity required Mg2+. Similar levels of I-1-P phosphatase were detected by 31P NMR and colorimetric assays. With the crude protein mixture, it is difficult to determine whether I-2-P can be hydrolyzed (I-2-P is a substrate for the avian and plant I-1-P phosphatase enzymes but not for the mammalian enzyme). However, this ammonium sulfate fraction did have some activity toward β-glycerophosphate, a compound that is sometimes a substrate for I-1-P phosphatase found in yeasts and plants. I-1-P phosphatases can have various degrees of activity toward secondary phosphate groups as in 2′-AMP, I-2-P, and β-glycerophosphate. In contrast, the 44 to 85% protein fraction exhibited a nonspecific alkaline phosphatase activity that was indiscriminate as to phosphomonoester substrate. Both I-1-P (Fig. 3B) and G-6-P (Fig. 3D) led to production of Pi. With an increase in temperature from 55 to 85°C, hydrolysis of G-6-P by the 0 to 44% protein fraction increased, suggesting that some of the nonspecific phosphatase might also be included in this protein fraction. At 85°C, the 0 to 44% ammonium sulfate fraction had a phosphatase specific activity of 2.3 nmol · min−1 · mg−1 toward I-1-P. The M. igneus I-1-P phosphatase activity could be stimulated by KCl; it was also inhibited by LiCl (though at a concentration [>100 mM] much higher than that required to totally inhibit the mammalian I-1-P phosphatase [1 mM]).

FIG. 3.

1H-decoupled 31P spectra (202.3 MHz) for analysis of specific I-1-P phosphatase activities from incubations (55°C, 16 h) of mixtures containing 6 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris acetate (pH 8.0), and the following: 2 mM I-1-P and the 0 to 44% fraction (A), 2 mM I-1-P and the 44 to 85% fraction (B), 2 mM G-6-P and the 0 to 44% fraction (C), and 2 mM G-6-P and the 44 to 85% fraction (D).

Synthesis of DIP from myo-inositol and CDP-I.

The proposed synthesis of DIP from I-1-P and myo-inositol requires activation of the I-1-P for condensation with myo-inositol. In lipid metabolism, CTP is used as a carrier molecule in phosphoryl and nucleotidyl transfers (25, 27). The nucleophilic character of I-1-P makes it a good candidate for a phosphoryl transfer reaction. The reaction carried out by CTP:I-1-P cytidylyltransferase (CDP-I synthase) would yield the intermediate, CDP-I (Fig. 1). DIP biosynthesis then proceeds similarly to the biosynthesis of phosphatidylserine. CDP-I is attacked by a myo-inositol hydroxyl group with the assistance of a general base provided by an enzyme. Such an activity would represent what we will refer to as a DIP synthase.

Crude protein extract from M. igneus was examined for evidence of CDP-I synthase activity. Due to the CTPase activity found in crude extracts and the thermal instability of the CDP at the high incubation temperature, the reaction mixture was incubated at 65°C for only 1 h. About 90% of CTP was hydrolyzed during this time period. We failed to reproducibly detect any net biosynthesis of CDP-I under various conditions, including preparation of protein extracts under anaerobic conditions using 31P NMR spectra to monitor for CDP-I.

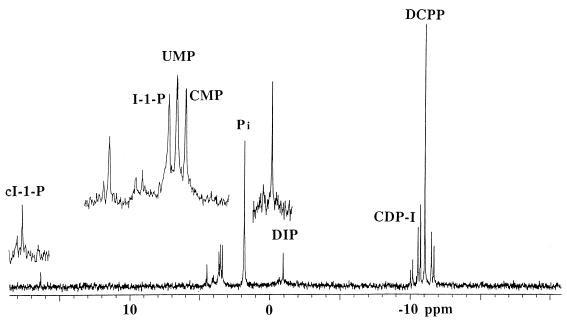

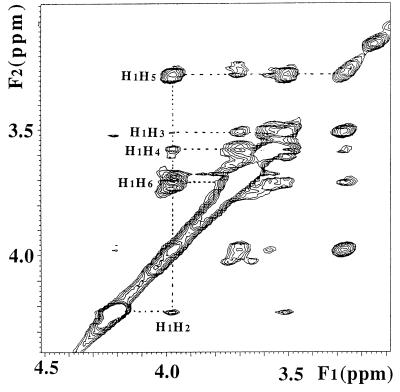

However, an alternate way to confirm the proposed biosynthetic pathway for DIP is to monitor for DIP synthase by using synthetic CDP-I, crude protein, and myo-inositol. These DIP synthase assays were performed with 2 to 3 mM CDP-I, 0.6 mg of protein (from dialyzed cell extract) per ml, and 5 mM myo-inositol; Mg2+ was also included in the assays. This mixture was incubated at 65 or 75°C for 2 or 3 h, and the amount of DIP (and product CMP) produced was monitored by 31P NMR. The several control experiments, the assay mix was incubated without added enzyme, CDP-I, or myo-inositol. As shown in Fig. 4, resonances for both DIP and CMP were easily separated from reactant CDP-I and impurities related to the CDP-I synthesis (UMP and DCPP). CDP-I isomers gave rise to AB quartets; the larger quartet reflects the inositol-1-phosphoryl adduct, while the smaller intensity quartet reflects the CDP attached to the inositol-2-hydroxyl group. The impurity DCPP has two equivalent phosphorus atoms and is characterized by a singlet at −11 ppm. A small amount of I-1-P (characterized by the resonance at ∼3.6 ppm) appeared during the incubation. The resonance for UMP (produced by deamination of CMP) at 3.5 ppm arises from the CDP-I synthesis and was not removed from CDP-I by the anion-exchange chromatography used. However, neither the DCPP nor the UMP was used in product formation. After incubation of the enzyme with the CDP-I and myo-inositol assay mixture, three new resonances appeared with 31P chemical shifts of −0.93, 3.40, and 16.4 ppm. The resonance at 16.4 ppm was identified as cyclic inositol-1,2-phosphate (cIP) (29); this compound was generated nonenzymatically by heating CDP-I at high temperatures. The intensity of Pi (2.2 ppm) also increased significantly, presumably due to the hydrolysis of UMP (Fig. 4). Both CDP-I and enzyme were absolutely necessary for the appearance of the resonances at −0.93 and 3.4 ppm. Several lines of evidence confirmed that the resonance at −0.93 ppm was DIP. First, its 31P chemical shift coincided with authentic DIP (5); it also exhibited the right H-P coupling pattern (a triplet) and coupling constant (8 Hz). This coupling clearly ruled out nonspecific phosphodiester formation. If the enzyme used cytidine (or even uridine) and inositol to form myo-inositol-1-cytidine-5′-phosphate or di-cytidine-5-5′-phosphate, the 1H coupling would have exhibited a quartet, quintet, or mixed pattern. Second, the two-dimensional 31P-1H NMR HETCOR spectrum showed that the proton coupled to this phosphorus had a chemical shift of 4.0 ppm, identical to the chemical shift of the C-1 proton of the inositol ring in DIP; an identical HETCOR spectrum was obtained previously for DIP in an ethanol extract (4). Third, another reaction product, CMP (3.4 ppm), was observed in the assay mixture only after incubation with the enzyme fraction. Fourth, control experiments showed that DIP synthesis required both CDP-I and enzyme. For the assay without added myo-inositol, a very small amount of DIP was produced. However, as noted previously, there was a small amount of I-1-P in the mixture, and significant phosphatase activity (either specific or nonspecific) present in the crude cell extract would easily generate myo-inositol that could be enzymatically condensed with CDP-I to form DIP. When more myo-inositol and 100 μl of fresh cell extract (∼1 mg of protein per ml) were added to this reaction mixture and the sample was incubated at 75°C for 3 h, the intensity of the DIP resonance increased dramatically. The last and strongest piece of evidence for DIP synthesis came from a 1H-1H TOCSY experiment on DIP partially purified from the assay mix. Two DIP synthase assay mixtures were combined and loaded onto the QAE-Sephadex A-25 column (0.7 by 15 cm) and eluted with 50 mM ammonium acetate (pH 7.4). This procedure separated DIP and cIP from all of the other, more negatively charged phosphate esters. After repeated lyophilizations from D2O (to desalt the fractionated DIP and cIP), the sample gave rise to two 31P NMR resonances: a minor resonance at 16.4 ppm (cIP) and a major resonance at −0.83 ppm consistent with DIP (the DIP chemical shift varies slightly with the counterion and solvent mixture). A 1H-coupled 31P spectrum confirmed that the DIP resonance was a triplet (JHP = 8 Hz) and the cIP resonance was a doublet (JHP = 20 Hz). The 31P-1H HETCOR spectrum indicated that the phosphorus was coupled to a proton at 4.0 ppm. 1H NMR spectra contained six DIP CH resonances; a 1H-1H TOCSY spectrum showed that all six protons of the inositol ring were connected in a single spin system (Fig. 5). The chemical shifts (given in parts per million) were identical to those for authentic DIP purified from ethanol extracts of M. igneus: 3.98 (H-1), 4.225 (H-2), 3.51 (H-3), 3.59 (H-4), 3.28 (H-5), and 3.71 (H-6). Rates for DIP production at 65 and 75°C were 0.75 ± 0.25 and 2.6 ± 0.8 nmol · min−1 · mg−1. This leads to an estimate of the activation energy for the reaction of ∼120 kJ/mol.

FIG. 4.

31P spectrum (121.4 MHz) for analysis of DIP synthase activity. Fifty microliters of CDP-I stock solution (30 mM), 300 μl of dialyzed cell extract, and 5 mM myo-inositol were incubated at 65°C for 2 h. The insets show expansions of the 3- to 5-ppm region, the phosphate monoester region, and the DIP region at ∼−1 ppm. Each phosphorus resonance in the spectrum is labeled.

FIG. 5.

1H-1H TOCSY NMR spectrum of DIP partially purified from the DIP synthase assay mixture. The vertical dotted line identifies all six DIP inositol protons in the ring spin system.

13C labeling of DIP and the pentose phosphate pathway.

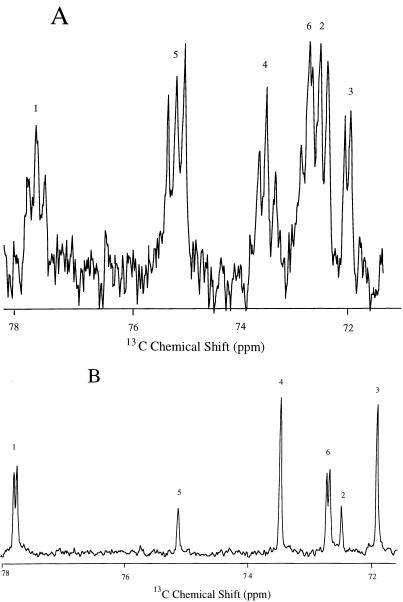

13C label incorporation from specific precursors has provided information on a wide array of biosynthetic pathways (e.g., reductive or oxidative segment of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, amino acid biosynthesis, and β-amino acid osmolyte biosynthesis) in methanogens (7–11, 18, 19, 23). Use of a double-labeled molecule such as [2,3-13C]acetate or [2,3-13C]pyruvate as a precursor allows easy identification of small amounts of label incorporation since a 13C-13C doublet flanks the singlet for 13C-12C (9) when the 13C2 unit is incorporated intact. Label incorporation into DIP can be predicted based on its proposed biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 6). The doubly labeled precursor should label four of the DIP carbons (C-1, C-2, C-5, and C-6), while [3-13C]pyruvate should label only two, C-1 and C-6. The carbons for these species have been identified in natural-abundance 13C NMR spectra of ethanol extracts of M. igneus (5). In the 1H-decoupled 13C NMR spectrum of DIP (Fig. 7A) obtained from labeling of M. igneus cultures with [2,3-13C]pyruvate, 13C-13C coupled doublets clearly flank the natural-abundance peaks of the C-1, C-4, and C-5 nuclei. For C-1, each resonance is also split by a small 13C-31P coupling so that each line in the multiplet is a doublet as well. The 71.8- to 73.0-ppm region of the spectrum is characterized by an extensive overlap of the resonances that correspond to the nuclei of the C-6, C-2, and C-3 atoms. Although the 13C-13C splitting pattern flanking 13C-12C singlets is harder to decipher, the complexity in the region suggests that 13C enrichment occurred for all carbon atoms.

FIG. 6.

Predicted 13C labeling for DIP using [2,3-13C]pyruvate: ∗, label from C-3 of pyruvate; ▵, label from C-2 of pyruvate.

FIG. 7.

1H-decoupled 13C-NMR spectra of DIP obtained from labeling of M. igneus cultures with [2,3-13C]pyruvate (A) and [3-13C]pyruvate (B). Identities of the different DIP carbons are indicated by numbers above the resonances. Relative enrichment of DIP carbons in panel B is monitored by the integrated intensities.

Labeling of M. igneus cells with [3-13C]pyruvate yielded a much simpler pattern of DIP labeling. As shown in Fig. 7B, all 13C resonances were singlets except for C-1 and C-6, which were doublets due to 31P splitting (the same pattern was observed in extracts from unenriched cultures). 13C-O-31P coupling through two bonds is typically 7 to 12 Hz, hence the C-1 doublet. The magnitude of three-bond 13C-C-O-31P coupling is determined by the dihedral angle. It is large for C-6 but small for C-2. Therefore, only C-1 and C-6 are split by 31P. To compare 13C incorporation into the 31P split carbons versus the others, the total intensity of each doublet was measured. A clear pattern of 13C enrichment emerged: the same level of 13C enrichment occurred for carbons C-1, C-4, C-6, and C-3, which was three times more than the amount of 13C in C-5 and C-2. Thus, four DIP carbon atoms exhibited 13C labeling from [3-13C]pyruvate.

The observed 13C labeling patterns of DIP from either [2,3-13C]pyruvate or [3-13C]pyruvate are in contrast to what is predicted based on the simple DIP biosynthetic scheme (Fig. 6). More DIP carbons are labeled than predicted in both cases. The 31P results (which verify the pathway from G-6-P to DIP) together with the determination of DIP ring stereochemistry clearly indicated that the DIP is formed from two l-inositol rings. Therefore, the 13C enrichment must already be in the G-6-P (at C-3 and C-4) before it is shuttled into DIP. The only way to scramble the label in the G-6-P pool would be to include enzymes of the pentose phosphate pathway. Pentose biosynthesis in a different Methanococcus species (28) has been proposed to occur via transketolase and transaldolase activities, a nonoxidative pathway that contains many of the enzymes common to both the oxidative and reductive pentose pathways. If similar activities were operational in M. igneus, the G-6-P pool would have label in C-3 and C-4 as well as in C-1 and C-6 when [3-13C]pyruvate was used as a substrate for carbon assimilation (consistent with Fig. 7B). The net result would be d-glucose molecules with label at C-1, C-3, C-4, and C-6. This would lead to inositol molecules with 13C enrichment at C-1, C-3, C-4, and C-6 as observed. When [2,3-13C]pyruvate is the precursor is used, this modification of gluconeogenesis to include enzymes of the pentose pathway leads to label incorporation at all carbons of DIP (consistent with Fig. 7A).

DISCUSSION

DIP is a novel osmolyte in archaea and closely related eubacteria that appears to track thermophily. Understanding this correlation on a molecular level requires a detailed understanding of DIP biosynthesis in these organisms. The in vitro assays and 13C labeling presented in this work confirm a pathway for DIP synthesis in M. igneus that consists of the following five steps: (i) production of G-6-P by gluconeogenesis and scrambling of glucose label via enzymes of the pentose phosphate pathway; (ii) generation of l-I-1-P by the enzymatic action of I-1-P synthase; (iii) conversion of I-1-P to myo-inositol by a specific phosphatase, I-1-P phosphatase; (iv) conversion of l-I-1-P to CDP-I with CTP as the carrier molecule in the phosphoryl transfer of this reaction; and (v) nucleophilic attack of the free hydroxyl group of C-1 of myo-inositol on CDP-I to produce DIP. Steps ii and iii have been elucidated in detail in plants and other organisms. Analogs of step iv occur in many cells as part of phospholipid biosynthesis, although this is not the way phosphatidylinositol is synthesized in cells (CDP-diacylglycerol is the activated species). Step v, the novel DIP synthesis reaction, is based on phosphatidylinositol synthesis in both eukaryotic and bacterial cells with myo-inositol attacking CDP-I instead of the CDP-diacylglycerol. Step v is the direct synthesis of DIP, and this reaction was shown to occur with chemically synthesized CDP-I and free myo-inositol in crude extracts of M. igneus. Understanding the mechanistic details of how steps iv and v are carried out will require purifying the activities from cell extracts.

One of the intriguing results of the in vitro studies is that the temperature dependence of the different enzymes sheds light on why DIP is accumulated only in M. igneus grown above 80°C. The synthesis of DIP from CDP-I and myo-inositol has quite a high activation energy, ∼120 kJ · mol−1 (Table 1). For comparison, the start of the DIP biosynthetic pathway, I-1-P synthase, exhibits an activation energy of 60 to 70 kJ · mol−1 (Table 1). The I-1-P phosphatase in crude mixtures has an even lower activation energy (<50 kJ · mol−1), although since multiple phosphatases exist, this value may not be very accurate. A purified I-1-P phosphatase from M. jannaschii expressed in Escherichia coli has an activation energy of 54 kJ · mol−1 (3). At lower growth temperatures, any I-1-P generated may be hydrolyzed to myo-inositol, possibly for incorporation into lipids. I-1-P cannot accumulate to levels needed for conversion to CDP-I and eventual DIP synthesis. As the growth temperature is increased, however, not only is more I-1-P generated, but DIP synthase activity is enhanced. Cells need ∼0.15 μmol of DIP per mg of protein for osmotic balance when grown in normal medium containing 0.3 M NaCl (5). The rate of DIP synthesis that is extrapolated for growth at 85°C, ∼0.01 μmol · min−1 · mg−1, easily provides this amount in the doubling time of the organism. Whether the DIP really has a thermoprotective role or whether accumulation of DIP represents a way for the cell to use excess inositol (by storing it in a compound used for osmotic balance) in this organism remains to be determined.

As a by-product of analyzing the pathway for biosynthesis of DIP by 13C labeling, we have found that M. igneus must have many of the enzymes of the pentose phosphate pathway. Yu et al. (28) have suggested that a nonoxidative pathway for pentose production may be advantageous for an autotroph since it would avoid release of CO2. However, the existence of transaldolase and transketolase activities in this methanococcus is in direct contrast to what has been observed with a number of other methanogens. Representatives of other genera (e.g., Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum and Methanospirillum hungatei) do not show evidence of pentose phosphate enzymes, and it has been suggested that pentoses in these methanogens are formed by the oxidative decarboxylation of hexoses (7). Other methanococci have been examined by either 13C NMR or enzymatic assays specifically for these activities, with mixed results. 13C labeling of M. jannaschii (23), a hyperthermophilic organism, indicated that pentose phosphate enzymes were not present since no 13C label scrambling was observed: [3-13C]pyruvate labeled only C-1 and C-6 of hexoses. Another mesophilic methanococcus, M. maripaludis, showed significant transaldolase, transketolase, and appropriate epimerase activities (28). However, no 13C labeling experiments were carried out to verify that hexose labels would be scrambled. These limited comparisons show no correlation between thermophily and a nonoxidative pathway for pentose biosynthesis, since M. igneus appears more like the mesophilic M. maripaludis in possessing active transaldolase, transketolase, and epimerase activities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant DE-FG02-91ER20025 (to M.F.R.) from the Department of Energy Biosciences Division.

We thank William B. Whitman for helpful discussions on the occurrence of pentose pathway enzymes in Methanococcus species.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnett J E G, Brice R E, Corina D L. Colorimetric determination of inositol monophosphates as an assay for d-glucose-6-phosphate-1L-myo-inositol 1-phosphate cyclase. Biochem J. 1970;119:183–186. doi: 10.1042/bj1190183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen I W, Charalampous F C. Biochemical studies on inositol. VIII. Purification and properties of the enzyme system which converts glucose-6-phosphate to inositol. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:3507–3512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L, Roberts M F. Cloning and expression of the inositol monophosphatase gene from Methanococcus jannaschii and characterization of the enzyme. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2609–2615. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2609-2615.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciulla R A. Response of methanogens to osmotic stress: in vitro and in vivo NMR studies. Ph.D. dissertation. Boston, Mass: Department of Chemistry, Boston College; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciulla R A, Burggraf S, Stetter K O, Roberts M F. Occurrence and role of di-myo-inositol-1,1′-phosphate in Methanococcus igneus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3660–3664. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3660-3664.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenberg F, Jr, Ranganathan P. Measurement of biosynthesis of myo-inositol from glucose-6-phosphate. Methods Enzymol. 1987;141:127–143. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)41061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekiel I, Smith I C P, Sprott G D. Biosynthetic pathways in Methanospirillum hungatei as determined by 13C nuclear magnetic resonance. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:316–326. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.1.316-326.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escamilla J E, Contreras M, Martinez A, Zentella-Pina M. L-myo-Inositol-1-phosphate synthase from Neurospora crassa: purification to homogeneity and partial characterization. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982;218:275–285. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans J N S, Raleigh D P, Tolman C J, Roberts M F. 13C NMR spectroscopy of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum: carbon fluxes and primary metabolic pathways. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:16323–16331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans J N S, Tolman C J, Kanodia S, Roberts M F. 2,3-Cyclopyrophosphoglycerate in methanogens: evidence by 13C NMR spectroscopy for a role in carbohydrate metabolism. Biochemistry. 1985;24:5693–5698. doi: 10.1021/bi00342a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorkovenko A, Roberts M F, White R H. Identification, biosynthesis, and function of 1,3,4,6-hexanetetracarboxylic acid in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum strain ΔH. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1249–1253. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.4.1249-1253.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gumber S C, Loewus M W, Loewus F A. myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase from pine pollen: sulfhydryl involvement at the active site. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984;231:372–377. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loewus F A. Inositol metabolism in plants. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1990. Inositol biosynthesis; pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loewus F A, Everard J D, Young K A. Inositol metabolism in plants. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1990. Inositol metabolism: precursor role and breakdown; pp. 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martins L O, Carreto L S, Da Costa M S, Santos H. New compatible solutes related to d-myo-inositol-phosphate in members of the order Thermotogales. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5644–5651. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5644-5651.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martins L O, Santos H. Accumulation of mannosylglycerate and di-myo-inositol-phosphate by Pyrococcus furiosus in response to salinity and temperature. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3299–3303. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3299-3303.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauck L A, Wong Y H, Sherman W R. l-myo-Inositol-1-phosphate synthase from bovine testis: purification to homogeneity and partial characterization. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;19:3623–3629. doi: 10.1021/bi00556a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts M F, Lai M-C, Gunsalus R P. Biosynthetic pathways of the osmolytes Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, β-glutamine, and betaine in Methanohalophilus strain FDF1 deduced from nuclear magnetic resonance analyses. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6688–6693. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6688-6693.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson D E, Noll D, Roberts M F. Free amino acid dynamics in marine methanogens: β-amino acids as compatible solutes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14893–14901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson D E, Roberts M F, Belay N, Stetter K O, Boone D R. Occurrence of β-glutamate, a novel osmolyte, in marine methanogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1504–1508. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1504-1508.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roseman S, Distler J J, Moffatt J G, Khorana H G. Nucleoside polyphosphates. XI. An improved general method for the synthesis of nucleotide coenzymes: syntheses of uridine-5′, cytidine-5′ and guanosine-5′ diphosphate derivatives. J Am Chem Soc. 1961;83:659–663. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scholz S, Sonnenbichler J, Schafer W, Hensel R. Di-myo-inositol-1,1′-phosphate: a new inositol phosphate isolated from Pyrococcus woesei. FEBS Lett. 1992;306:239–242. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81008-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sprott G D, Ekiel I, Patel G B. Metabolic pathways in Methanococcus jannaschii and other methanogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1092–1098. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.1092-1098.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas F D, Susan A H. Myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase: characteristics of the enzyme and identification if its structural gene in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:7077–7085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vance D E. Biosynthesis of membrane lipids and related substances. In: Zubay G, editor. Biochemistry. Dubuque, Iowa: Wm. C. Brown Publishers; 1993. p. 618. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Leeuwen S H, van der Marel G A, Hensel R, van Boom J H. Synthesis of l,l di-myo-inositol-1,1′-phosphate: a novel inositol phosphate from Pyrococcus woesei. Recl Trav Chim Pays-Bas. 1994;113:335–336. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh C. Enzymatic reaction mechanisms. San Francisco, Calif: W. H. Freeman and Co.; 1977. pp. 253–255. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu J-P, Lapado J, Whitman W B. Pathway of glycogen metabolism in Methanococcus maripaludis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:325–332. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.2.325-332.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou C, Wu Y, Roberts M F. Activation of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C towards inositol 1,2-(cyclic)-phosphate. Biochemistry. 1997;36:347–355. doi: 10.1021/bi960601w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zwickl P, Fabry S, Bogedain C, Haas A, Hensel R. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus woesei: characterization of the enzyme, cloning and sequencing of the gene, and expression in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4329–4338. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4329-4338.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]