Abstract

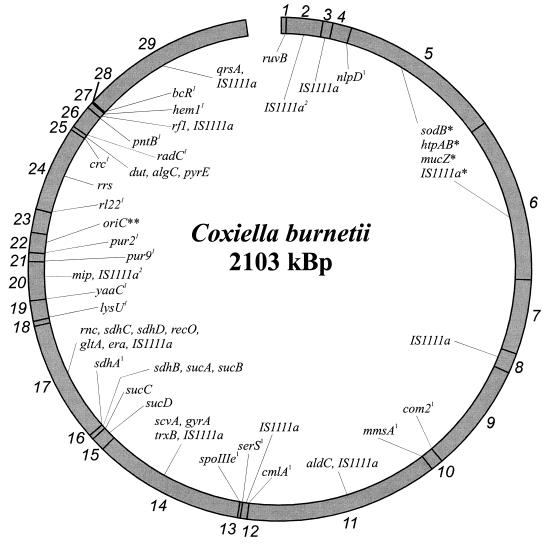

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and PCR techniques have been used to construct a NotI macrorestriction map of the obligate intracellular bacterium Coxiella burnetii Nine Mile. The size of the chromosome has been determined to be 2,103 kb comprising 29 NotI restriction fragments. The average resolution is 72.5 kb, or about 3.5% of the genome. Experimental data support the presence of a linear chromosome. Published genes were localized on the physical map by Southern hybridization. One gene, recognized as transposable element, was found to be present in at least nine sites evenly distributed over the whole chromosome. There is only one copy of a 16S rRNA gene. The putative oriC has been located on a 27.5-kb NotI fragment. Gene organization upstream the oriC is almost identical to that of Pseudomonas putida and Bacillus subtilis, whereas gene organization downstream the oriC seems to be unique among bacteria. The physical map will be helpful in investigations of the great heterogeneity in restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns of different isolates and the great variation in genome size. The genetic map will help to determine whether gene order in different isolates is conserved.

Coxiella burnetii, an obligate intracellular bacterium propagating in the phagolysosomes of eucaryotic cells, is the only species of the genus Coxiella. In comparison to other members of the family Rickettsiaceae, C. burnetii demonstrates high resistance to chemical and physical agents, making it possible for the organism to remain infectious after years outside the host cell (2). C. burnetii infection of humans manifests itself as acute Q fever with influenza-like symptoms. However, infection may also result in the therapy-resistant chronic form of Q fever with endocarditis, granulamatous hepatitis, or osteomyelitis (37).

Though C. burnetii has been recognized worldwide as an important pathogen, little is known about the genes that contribute to virulence, particularly tissue invasiveness and intracellular persistence. Virulence potential is correlated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) content of the organism (55). When propagated in nonimmunocompetent systems such as embryonated chicken eggs or persistently infected cell cultures, C. burnetii converts from phase I to phase II particles. Phase shift is accompanied by a drastic change in LPS content and structure of the outer membrane, with a significant decrease in virulence potential (34). Initial studies of LPS phase variation focused on possible alteration of plasmid-encoded genes. However, cloning and sequencing of the entire QpH1 plasmid (45) and plasmid sequences integrated into the chromosome of plasmidless C. burnetii Scurry Q217 (51) revealed no evidence for genes involved in phase variation. Furthermore, plasmid type had been correlated to the type of disease (39), but this has been refuted by several authors (44, 58). These findings suggest virulence factors to be chromosomally encoded. Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns demonstrated a great heterogeneity of C. burnetii isolates (21, 24, 46) which may be associated with virulence potential. A physical map of C. burnetii Nine Mile would provide a means to evaluate the reason(s) for this great heterogeneity and the different virulence potentials of isolates.

Due to restrictions imposed by the intracellular nature of C. burnetii, genetic studies have always been performed with Escherichia coli as the vehicle for gene expression. Nevertheless, gene organization of an organism can be studied only with an existing genetic map. Classical genetic maps are constructed by well-established methods such as transduction, transformation, conjugation, or transposon mutagenesis. But since obligate intracellular bacteria are not amenable to conventional linkage mapping, the only way to construct a genetic map—apart from sequencing—is to first establish a physical map and then locate genes on the physical map by hybridization techniques. A first step toward generation of C. burnetii mutants was recently undertaken by Suhan et al. (42), with the successful transformation of C. burnetii to ampicillin resistance. Here we present the physical and genetic map of C. burnetii Nine Mile constructed mainly by two methods, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and PCR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

C. burnetii Nine Mile RSA 493 was obtained from L. P. Mallavia, Washington State University, Pullman. C. burnetii NotI/Sau3a and NotI/EcoRI fragments were shotgun cloned in phagemid vector pBluescript II KS(+) (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany) and transformed into E. coli XL1 Blue (Stratagene).

PFGE sample preparation.

Heat-inactivated (15 min, 85°C) C. burnetii organisms were diluted to a concentration of 2 × 109 particles/ml. One volume of this suspension was mixed with 1 volume of solubilized 1% InCert agarose (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) at 50°C. Agarose-embedded C. burnetii was lysed overnight at 56°C with proteinase K (500 μg/ml) and washed twice with 10 volumes of 1× TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA) for 30 min. Proteinase K was inactivated by phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1 mM) at 50°C. C. burnetii total DNA embedded in agarose plugs was digested with 10 U of NotI/ml in 400 μl of 2× Universal buffer (Stratagene) overnight at 37°C.

PFGE.

All PFGE gels (1% MBC agarose; Bio-Rad) were run on a CHEF (contour-clamped homogeneous electric field) mapper apparatus (Bio-Rad). The following parameters were applied to separate NotI fragments of the indicated size ranges: (i) 2 to 270 kb, pulse time of 0.1 to 11.0 s for 8 h, linear gradient and then 9.0 to 24.0 s for 12 h, linear gradient at constant voltage (6 V/cm) and constant angle (120°); (ii) 50 to 270 kb, pulse time of 14.23 to 16.08 s for 23 h 22 min, linear gradient at constant voltage (6 V/cm) and constant angle (120°), ramping factor of −1,357; and (iii) 2 to 55 kb (field inversion gel electrophoresis [FIGE]): pulse time of 0.05 to 0.12 s for 9 h 26 min, forward voltage of 9 V/cm, reverse voltage of 6 V/cm.

DNA probes.

Biotinylated gene probes were prepared by PCR with biotin-21-dUTP (Amersham, Braunschweig, Germany), using different dTTP/biotin-21-dUTP ratios (3:1, 6:1, and 9:1). From cloned DNA fragments, plasmid DNA was prepared and biotin labeled by nick translation (Nick translation biotinylation kit; Serva, Heidelberg, Germany).

Southern hybridization.

To dissect large NotI fragments, PFGE gels were exposed to UV light (Stratalinker; Stratagene) with an energy of 60 mJ/cm2. Southern blotting was performed as downward blotting (8). Fragments were denatured (0.5 M NaOH–1.5 M NaCl, two cycles of 30 min each) and transferred to Biodyne B membranes (Pall; Dreieich, Germany) with 20× SSC (3 M NaCl, 0.3 M sodium citrate) as the transfer buffer. Transferred DNA was immobilized by exposure to UV light (120 mJ/cm2). Hybridization experiments were carried out at 60°C with 200 ng of denatured probe. Since probed DNA was always the same (C. burnetii Nine Mile) and only probes differed, the membrane was cut into stripes (3 by 130 mm) and hybridizations were performed in a specially constructed hybridization chamber. Stringency washes and chemiluminescence detection of biotinylated DNA were carried out as instructed by the manufacturer (Serva).

XL PCR.

XL (extra-large) PCR was developed for the amplification of DNA fragments of up to 40 kb (7). XL PCR was performed on a Perkin-Elmer thermal cycler (model 9600; Perkin-Elmer/ABI, Weiterstadt, Germany) in a total volume of 50 μl consisting of 1× XL buffer, 1.1 mM magnesium acetate, 0.4 μM each primer, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1 U of XL polymerase, and 104 to 106 DNA templates. To amplify the 27.5- and 11-kb fragments, the following conditions were applied (values for the 11-kb fragment are in parentheses): 15 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s, annealing and extension at 68°C for 15 min and 30 s (60°C, 7 min); 15 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s, annealing and extension at 68°C for 15 min and 30 s, with an autoextension time of 15 s per cycle (60°C, 7 min plus 15 s per cycle). Prior to PCR, template DNA was allowed to completely denature at 94°C for 1 min. After PCR, an additional extension step at 72°C for 10 min was applied to maintain fully double-stranded DNA.

Sequencing.

Nonradioactive sequencing reactions were performed with a PRISM Ready Reaction Dye-Deoxy Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Perkin Elmer/ABI) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Sequence analysis.

DNA sequence analysis was performed with the DNASTAR software package (DNASTAR Inc., London, England). Primers were designed with the OLIGO software program (Medprobe, Oslo, Norway) and synthesized on a model 381A DNA synthesizer (Perkin-Elmer/ABI).

RESULTS

Mapping strategy.

The physical map of C. burnetii Nine Mile has been constructed by a top-down approach in combination with PCR technology.

PFGE was applied to separate fragments after NotI digestion of C. burnetii total DNA. PFGE gels were blotted and used in Southern hybridization experiments. Simultaneously, NotI/EcoRI and NotI/Sau3A fragments respectively of C. burnetii were shotgun cloned and sequenced. Sequence data were analyzed for open reading frames (ORFs) containing the NotI restriction site. Polypeptides deduced from ORFs were compared to protein database entries. Two polypeptides showing homology to the same database entry were considered as being adjacent. Proximity was proven by PCR with total C. burnetii DNA as the template. Amplicons from positive PCR results were digested with NotI to verify the contiguity of the two fragments.

Proximity of cloned fragments without any homology to database entries was examined by checkerboard PCR. For this purpose primers deduced from sequenced fragments and directed to the NotI site were combined in pairs and subjected to PCR with C. burnetii total DNA as the template. In all other cases where adjacent fragments were missing, we applied adaptor PCR (54).

Physical map.

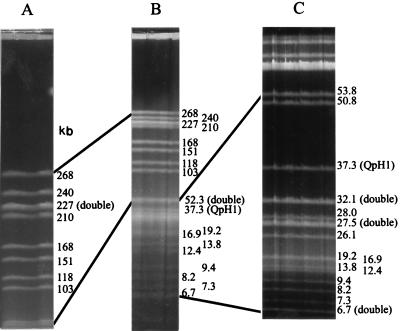

PFGE has been shown to be the method of choice for constructing macrorestriction maps of bacterial genomes (10) provided that appropriate rare-cutting restriction enzymes are available. Criteria for the selection of restriction enzymes have been developed by McClelland et al. (31). Most obviously, in bacterial genomes with G+C contents above 45%, the tetranucleotide sequence CTAG is extremely rare. Similarly, trinucleotides CCG and CGG are rare in genomes with G+C contents of less than 45%. The G+C content of the C. burnetii genome has been determined to be 43 to 45% (36). Therefore, we selected restriction enzymes SfiI (GGCCNNNN′NGGCC), NotI (GC′GGCCGC), FseI (GGCCGG′CC), and SmaI (CCC′GGG). Finally we applied restriction enzyme NotI, which produces 29 fragments, 25 of which are distinguishable on ethidium bromide-stained CHEF-PFGE gels (Fig. 1B). For optimal resolution, portions of the molecular weight size range where DNA fragments accumulated were expanded. Resolution of NotI fragments around the 200-kb region was enhanced by extending the pulse times (Fig. 1A). The 30-kb region was expanded by FIGE (Fig. 1C). The average resolution of the macrorestriction map is 72.5 kb, with 2.1 kb being the smallest and 268 kb being the largest NotI fragment. Altogether, the size of the C. burnetii chromosome is 2,103 kb (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

CHEF-PFGE of NotI-digested total DNA. Different CHEF-PFGE parameters (see text) were applied to separate NotI fragments of 2 to 270 kb (B), 55 to 270 kb (A), and 6.7 to 55 kb (C). Lines indicate regions where resolution of NotI fragments has been increased. Panel A demonstrates fragments ranging in size from 210 to 268 kb to be clearly separated. Nevertheless, the two 227-kb NotI fragments are not distinguishable. Resolution enhancement is even more striking in panel C, where the 52.3-kb double fragment (B) divided into 53.8- and 50.8-kb NotI fragments. Panel C also demonstrates the 27.5- and 32.1-kb NotI fragments to be double fragments, as indicated by increased band intensities. In contrast, band intensity of the QpH1 plasmid suggests that there is only a single copy of the plasmid in C. burnetii Nine Mile.

FIG. 2.

Physical and genetic map of the chromosome of C. burnetii Nine Mile. NotI fragments are indicated by numbers on the outer circle (sizes in kilobases): 1, 7.3; 2, 50.8; 3, 13.8; 4, 26.1; 5, 227; 6, 227; 7, 103; 8, 27.5; 9, 151; 10, 16.9; 11, 268; 12, 9.4; 13, 3.9; 14, 210; 15, 19.2; 16, 6.7; 17, 168; 18, 6.7; 19, 28; 20, 53.8; 21, 12.4; 22, 27.5; 23, 32.1; 24, 118; 25, 5.3; 26, 32.1; 27, 8.2; 28, 2.1; 29, 240. NotI recognition sites are indicated by lines connecting the inner and outer circles. 1, contains the NotI recognition site. 2, hybridization signal intensity suggests IS1111a to exist at least once on the 50.8- and 53.8-kb NotI fragments (in Fig. 1B, lane 1, indicated as the 52-kb fragment). ∗, Could not be related to one of the 227-kb NotI fragments; hybridization signal intensity suggests IS1111a to exist at least once on both 227-kb NotI fragments (Fig. 1B, lane 1). ∗∗, putative genes located around the oriC region: fmu, glysAB, ygi2, ygi1, omp, gidB, gidA, 50K, 60K, and 9K.

In total, 3 NotI fragments (2.1, 5.3, and 6.7 kb) were sequenced completely, and partial sequence information was obtained from 3 NotI, 59 NotI/EcoRI, and 15 NotI/Sau3A fragments. Neighbors of the 3.9-kb NotI fragment had already been determined (EMBL accession no. X75627 and X70045), and one neighbor of the 6.7-kb NotI fragment was extracted from the EMBL database (accession no. L33409). From 87 clones sequenced, 33 fragments (3 NotI, 28 NotI/EcoRI, and 2 NotI/Sau3A) differed in sequence. In total, 50,282 bp including those extracted from the EMBL database were analyzed. The average G+C content has been determined to be 44%. The tetranucleotide sequence CTAG occurs about 23 times less frequently (0.08%) than AAAA (1.88%), whereas trinucleotides CGG and CCG, which are parts of the NotI recognition site show no trend. Assuming a random distribution of nucleotides, NotI sites appear every 131,070 bp. Thus, statistically 16 NotI fragments would be generated upon restriction of the C. burnetii chromosome (2,103 kb) with NotI. This is in contrast to experimental data (29 NotI fragments), meaning that the frequency of trinucleotides CGG and CCG is higher as expected by randomness.

We analyzed sequences for ORFs containing the NotI restriction site and found putative polypeptides deduced from 20 ORFs to be homologous to database entries. In each case, two polypeptides show homology to the same database entry. Hence, 10 NotI linking fragments (Table 1, amplicons 1, 5, 8, 13, 14, 18, 19, 23, 24, and 27) were identified simply as a result of homology to database entries. Remaining linking fragments were identified by checkerboard PCR (Table 1, amplicons 2, 4, 6, 10, 12, and 21) and adaptor PCR (Table 1, amplicons 3, 7, 9, 11, 15, 16, 22, and 25). Sequence data obtained from one adaptor fragment revealed a region containing an unusual G+C stretch of 17 bp with two nested NotI sites (GCGGCCGCGGCCGCGCC; first site in boldface and second site underlined).

TABLE 1.

Linking fragments as identified by PCR

| Amplicon no. | Primer 1/primer 2 | Amplicon size (bp)a | EMBL accession no. | Protein homologyb (Swiss-Prot) | NotI linking fragments (kb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12_1/1454 | 363 | AF064944 | PUR9_ECOLI | 12.4/53.8 |

| 2 | 1406/1408 | 240 | AF064945 | NH | 27.5/151 |

| 3 | 1411/1411NB | 328 | AF064946 | RL22_ECOLI | 32.1/118 |

| 4 | 1412/1465 | 495 | AF064947 | NH | 27.5/103 |

| 5 | 1455/516F | 361 | AF064948 | MMSA_PSEAE | 16.9/268 |

| 6 | 1463/5KS15 | 517 | AF064960/X79075 | NH | 5.3/32.1 |

| 7 | 1467/1467NB1 | 548 | AF064949 | NH | 227/227 |

| 8 | 1468/1629 | 336 | AF064950 | YAAC_PSEFL | 28/53.8 |

| 9 | 1469/1469NB | ≈1,800 | AF064962/AF064963 | NH | 19.2/210 |

| 10 | 1473/1488 | 346 | AF064951 | CMLA_PSEAE | 9.4/268 |

| 11 | 1474/1474NB | ≈1,300 | AF064964/AF064965 | NLPD_ECOLI | 26.1/227 |

| 12 | 1482/1607 | 492 | AF064952 | NH | 103/227 |

| 13 | 1496/1487 | 501 | AF064953 | RUVB_ECOLI | 7.3/50.8 |

| 14 | 1501/542NSF | 349 | Y10436 | GIDA_PSEPU | 27.5/32.1 |

| 15 | 1510/1510NB | ≈1,100 | AF064966/AF064967 | ND | 6.7/168 |

| 16 | 1632/1632NB | 631 | AF064954 | ECOLYSU | 6.7/28 |

| 17 | 200_1/4_1 | 748 | X75627/X70045 | SP3E_BACSU | 3.9/210 |

| 18 | 20T3/1475 | 407 | AF064955 | PUR2_ECOLI | 12.4/27.5 |

| 19 | 2KS5/1451R | 745 | X78969c | HEM1_SALTY | 2.1/8.2 |

| 20 | 4_2/10_1 | 584 | X75627/X70045 | SYS_ECOLI | 3.9/9.4 |

| 21 | 526F/1456 | 314 | AF064956 | ND | 13.8/26.1 |

| 22 | 526R/526NB | 224 | AF064957 | NH | 13.8/50.8 |

| 23 | 543NSF/1452 | 200 | AF064958 | PNTB_ECOLI | 8.2/32.1 |

| 24 | 565/1459 | 518 | AF064959 | COM2_BACSU | 16.9/151 |

| 25 | 5T716/5T716NB | 488 | AF064961/X79075 | PSECRC | 5.3/118 |

| 26 | 6KSN/6KS6307 | 591 | L33409 | DHSA_ECOLI | 6.7/168 |

| 27 | 6SK946/1470F1R | 1,331 | X77919/U07789 | SUCC_ECOLI | 6.7/19.2 |

| 28 | Bicyclo1/2 | 669 | X78969c | BCR_ECOLI | 2.1/240 |

Amplicons 9, 11, and 15 have not been sequenced completely; therefore, the exact amplicon size is not known.

From Swiss-Prot database. ORFs have been detected from amplicons 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12, but deduced polypeptides showed no homology (NH) to database entries. ORFs from amplicons 15 and 21 were not detected (ND).

Reference 53.

Southern hybridizations were used to relate the cloned DNA fragments (NotI/EcoRI and NotI/Sau3a) to the corresponding NotI fragment. Nevertheless, four NotI fragments (227, 32, 27.5, and 6.7 kb) appeared to be double fragments. One of the 6.7-kb NotI fragments has been sequenced completely (EMBL accession no. X77919). The 227- and 32-kb doublets were distinguished by Southern hybridization using a PFGE blot of partially FseI- and FseI/NotI-digested total C. burnetii DNA.

The 27.5-kb NotI double fragment was differentiated by XL PCR. For this purpose, primers deduced from fragments adjacent to the 27.5-kb NotI fragments were combined in pairs and subjected to XL PCR with C. burnetii total DNA as the template. With one primer combination, we achieved a positive result with an amplicon size of about 28 kb. Hybridization with probes derived from the four DNA fragments constituting the ends of the 27.5-kb NotI fragments revealed positive signals with only two of them.

Genetic map.

ORFs with homology to database entries (putative genes) and genes were located on the physical map by Southern hybridization. Hybridization with the omp gene as a probe revealed a hybridization signal with the 27.5-kb NotI double fragment. To relate the omp gene to one of the 27.5-kb NotI fragments, XL PCR was performed with primers deduced from the omp gene and the ends of the 27.5-kb fragments. The positive PCR result with one primer combination was confirmed by hybridization and sequencing of the 11-kb amplicon. In total, we mapped 54 genes and putative genes, of which 39 (Table 2; Table 1, amplicons 17, 20, and 26) were extracted from the EMBL database and 16 putative genes (Table 1, amplicons 1, 3, 5, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 27, and 28) were newly identified during the mapping experiments. Nineteen putative genes with homology to database entries contained the NotI recognition sequence. Several putative polypeptides demonstrated only low homology to database entries (bcr, cmlA, and nlpD), though hydrophobicity plots were very similar. One gene, recognized as transposable element (23), was found to hybridize with at least nine NotI fragments.

TABLE 2.

Genes assigned to the physical map

| Gene | Polypeptide | Accession no.a | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| rrs | M21291 | 1 | |

| qrsA | Sensor-like protein | U07186 | 30, 32 |

| IS1111a | Transposase | M80806 | 23 |

| fmub | Hypothetical protein | U10529 | |

| glysAb | Glycyl-tRNA synthetase (α chain) | Y10435 | |

| glysBb | Glycyl-tRNA synthetase (β chain) | U10529/Y10435 | 43 |

| ygi2b | 32.4-kDa protein | Y10436 | |

| ygi1b | 28.9-kDa protein | Y10436 | |

| omp (com1) | Outer membrane protein | Z11828/M88613 | 5, 22 |

| gidBb | Glucose-inhibited division protein B | Y10436 | |

| 50Kb | 50-kDa protein | Y10436 | |

| 60Kb | 60-kDa protein | U10529 | 43 |

| 9Kb | 9-kDa protein | U10529 | 43 |

| rnpAb | RNase P | U10529 | 43 |

| rpmHb | Ribosomal protein L34 | U10529 | 43 |

| mip | Macrophage infectivity potentiator protein | U14170 | 9, 33, 41 |

| rnC | RNase III | L27436 | 60 |

| recO | Repair and recombination protein | L27436 | 60 |

| era | GTP-binding protein | L27436 | 60 |

| sdhB | Succinate dehydrogenase (small subunit) | X77919 | 20 |

| sdhCb | Succinate dehydrogenase | L33409 | |

| sdhD | Succinate dehydrogenase | X77919 | 20 |

| gltA | Citrate synthase | M36338 | 16, 19 |

| sucAb | 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase | X77919 | |

| sucBb | Dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase | X77919 | |

| sucDb | Succinyl-coenzyme A synthetase | X77919 | |

| scvA | Small cell variant protein | L49019 | 18 |

| trxBb | Thioredoxin reductase | X75627 | |

| gyrAb | DNA gyrase (subunit A) | S82903 | 35 |

| aldCb | α-Acetolactate decarboxylase | U14393 | |

| sodB | Superoxide dismutase | M74242 | 17 |

| htpAB | Heat shock proteins | M20482 | 49 |

| mucZ | Mucoidy-inducing protein | L42518 | 59 |

| dutb | dUTP nucleotide hydrolase | X79075 | |

| algC | Phosphomannomutase | X79075 | |

| pyrEb | Orotate phosphoribosyltransferase | X79075 |

EMBL/GenBank database entry.

Putative gene for which there is no experimental evidence; designation corresponds to homologous genes in the database.

16S rRNA genes appear only once on the C. burnetii chromosome.

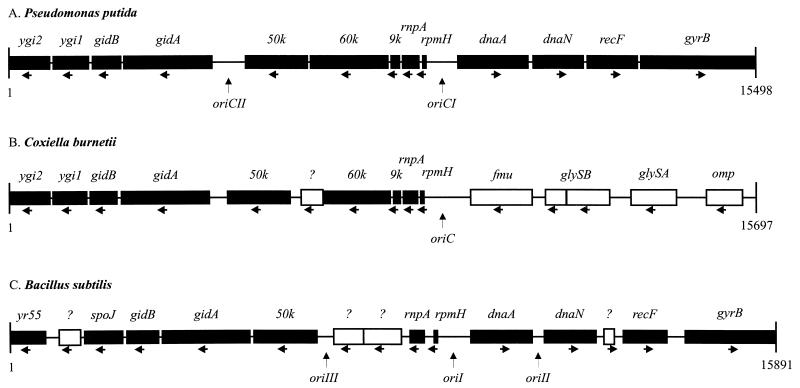

The putative oriC of C. burnetii (43) is located on a 27.5-kb NotI fragment. Gene organization upstream the putative oriC of C. burnetii is identical to that of Pseudomonas putida and nearly identical to that of Bacillus subtilis (Fig. 3). Most strikingly, sequences downstream the oriC of C. burnetii demonstrated a gene organization unique among bacteria. The gyrA gene, which has been found to be clustered in some bacteria with the dnaA, dnaN, recF, and gyrB genes, has been recently identified (35) and was mapped on the 210-kb NotI fragment.

FIG. 3.

Gene organization around the putative oriC of C. burnetii (B) compared to that of P. putida (A) and B. subtilis (C). The region upstream the oriC is almost identical to that of P. putida and B. subtilis (indicated by black boxes). Hypothetical proteins YGI1 and YGI2 of C. burnetii are homologous to YR55 and SpoJ of B. subtilis. Gene organization downstream the putative oriC of C. burnetii is quite different from that of P. putida and B. subtilis, as indicated by white boxes. Whereas in P. putida and B. subtilis genes around the oriC are transcribed in opposite direction, genes in C. burnetii are all transcribed in the same direction (indicated by arrows). Question marks above the white boxes indicate polypeptides without designation and with unknown function.

DISCUSSION

Since the introduction of PFGE (40), strategies for constructing physical maps changed from bottom-up (25, 57) to top-down techniques (10). With bottom-up techniques, genome maps are established by sorting clones from a genomic library. But this procedure is tedious and may become ambiguous if one enters regions of repetitive DNA. Moreover, regions which are difficult to clone represent one of the major problems encountered in bottom-up genome mapping. In contrast, top-down approaches are easily to perform and only few restriction fragments have to be examined for their natural order. Once the physical map is established, locations of a wide variety of other restriction enzymes can be placed on the existing map with relatively little effort.

The macrorestriction map of C. burnetii Nine Mile has been constructed mainly by two methods, PFGE and PCR. Southern hybridization was used to relate cloned fragments to the corresponding NotI fragments, and PCR was used to identify linking fragments.

The size of the C. burnetii Nine Mile chromosome has been determined from PFGE data to be 2,103 kb and thus has been underestimated by several authors (14, 36). Myers et al. (36) used renaturation techniques to determine the chromosome size, and Frazier et al. (14) applied PFGE. Both groups calculated a size of 1,600 kb for the C. burnetii chromosome, which is about 25% less than found in this study. Most obviously, Frazier et al. did not recognize double fragments and/or failed to notice fragments in regions where DNA fragments accumulated. Double fragments in this study were primarily identified by increased band intensities in PFGE gels compared to single bands of similar size. Duplication of these fragments was proven by hybridization to a PFGE blot of C. burnetii DNA digested with a second enzyme, by partial digestion, or by XL PCR. Other mapping strategies use two-dimensional PFGE to circumvent the need for detection of double fragments. However, one general intrinsic problem with two-dimensional PFGE is the reliable detection of smaller fragments due to unfavorably low fluorescence signals of the ethidium bromide stain. Smaller fragments may even diffuse out the agarose plug during digestion.

In most cases, genomes were mapped by two different techniques whereby most often partial digests were combined with the linking clone approach. In this study, linking clones were identified by two PCR methods (checkerboard and adaptor) instead of screening conventional DNA libraries or applying cross-hybridization techniques. The PCR methods circumvent some of the problems associated with cloned linking fragments. For instance, if two unlinked NotI-containing fragments are coligated, aberrant linking clones can be obtained. Cross-hybridization techniques use gel-purified probes to identify linking fragments. Nevertheless, gel-excised fragments contain impurities of randomly sheared DNA, leading to increased background hybridization signals. This increased background may hamper the unambiguous detection of faint hybridization signals generated from probes with very short overlaps. Moreover, in regions where DNA fragments accumulate, it is almost impossible to excise gel plugs without contamination with neighboring bands. Another restriction may be the amount of DNA in this fragment required to produce a reliable probe. A prerequisite to identify linking clones by PCR methods is the availability of sequences to construct primers. Sequences herein were obtained from shotgun cloning experiments. To make sure that clonable sizes are generated after digestion of C. burnetii total DNA, we chose as the second restriction enzyme (apart from EcoRI) Sau3A, which produces DNA fragments below 2 kb in size.

It remains uncertain whether the C. burnetii chromosome is linear or circular. However, several experimental results indicate the presence of a linear chromosome. Thus, it was not possible to clone the ends of the two fragments which would constitute the right and left ends of the linear chromosome, nor was it possible to amplify one of the putative ends (the 7.3-kb fragment) by XL adaptor PCR. In addition, undigested C. burnetii total DNA migrates as a single band on PFGE gels (data not shown), whereas open circular DNA molecules larger than 15 kb fail to migrate in PFGE (28). To date, linear chromosomes have been found in Borrelia burgdorferi (13), Streptomyces lividans (27), Agrobacterium tumefaciens (3), and Rhodococcus fascians (11), but nothing is known about the mechanism of replication in bacteria with linear chromosomes.

The oriC of C. burnetii has not yet been determined unequivocally. Gene organization around the oriC varies according to the taxonomic classification of the organism. Nevertheless, certain bacterial genes involved in replication are clustered. Whereas in all other organisms investigated so far, genes dnaA, dnaN, and gyrB are clustered and in the vicinity of rpmH, none of these genes is present downstream the oriC of C. burnetii (Fig. 3). This unusual gene organization reflects a replication mechanism quite different from that observed in bacteria with circular chromosomes. Therefore, further investigations are feasible to characterize the nature of the ends (e.g., single-stranded loops and telomeric structure) of the linear chromosome. The gyrA gene occupies a central position on the physical map of C. burnetii Nine Mile as has also been demonstrated for the gyrA genes of, for example, Borrelia burgdorferi, Clostridium perfringens, B. subtilis, and Leptospira interrogans (10). Nevertheless, presence of the dnaA gene, which is essential for replication and which is clustered with the gyrA gene in above-mentioned bacteria, remains to be confirmed.

The genetic map of C. burnetii revealed one gene which is recognized as a transposable element to be evenly distributed over the whole chromosome. Hoover et al. (23) demonstrated IS1111a to be present at least 19 times on the C. burnetii Nine Mile chromosome. We have mapped nine copies of the IS1111a gene, indicating that the gene appears more than once on several NotI fragments. Primers derived from the IS1111a element were used to establish a diagnostic PCR (52). Housekeeping genes belonging to the Krebs cycle show gene organizations identical to that of, for example, E. coli (12) or Azotobacter vinelandii (50).

On the C. burnetii chromosome there is only a single copy of the 16S rRNA gene, located on the 118-kb NotI fragment. This finding is in agreement with results published by Afseth and Mallavia (1) and correlates with the slow growth rate of C. burnetii. Though no direct evidence relates the number of rrn operons in an organism to growth rate regulation, slowly growing organisms such as Spiroplasma citri (56), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (26), and Chlamydia trachomatis (4) have been shown to have fewer copies.

As has been shown by DNA solution hybridization (29), C. burnetii isolates have many commonalities. However, RFLP analysis demonstrated a great heterogeneity in restriction patterns (21, 24, 46), possibly due to missense mutations and/or restriction site redistributions. Redistributions again are a result of significant chromosomal rearrangements (e.g., translocations, inversions, insertions, or deletions) which may play an important role in pathogenesis or virulence (47, 48). Similar rearrangements and exchange of DNA blocks have been described for Pseudomonas aeruginosa (38), leading to a 10% variation in chromosome size. Variation in chromosome size is even more striking in C. burnetii isolates ranging from about 1,500 to 2,400 kb. The high degree of DNA homology among C. burnetii isolates suggests that deletions resulting from recombinational (homologous or heterologous) events generated smaller genomes from larger ones. The now existing library of NotI linking fragments will facilitate comparisons of genome organization of different isolates and thus help to elucidate the reason(s) for the great heterogeneity in RFLP patterns. Furthermore, linking fragments may help to clarify which parts of the chromosome are the most conserved or variable ones and may help to answer the question of whether smaller C. burnetii genomes resulted from deletions in larger genomes. If so, this would provide a means for extensive epidemiological studies to evaluate the ubiquitous abundance of C. burnetii. The genetic map of C. burnetii Nine Mile may serve as a basis to identify genes or gene clusters affected by this tremendous loss of genetic information which seems to be no longer necessary for the organism to survive. It has been shown for Borrelia species that gene order is conserved, though nearly all isolates investigated demonstrated unique RFLP patterns (6). Whether this is also true for C. burnetii will be evaluated through comparison of gene order between isolates with different RFLP patterns.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Hannelore Falkenstein and the helpful scientific discussions with Detlef Thiele. We also thank Winfried Oswald for the shotgun cloning experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afseth G, Mallavia L P. Copy number of the 16S rRNA gene in Coxiella burnetii. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:729–731. doi: 10.1023/a:1007384717771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aitken I D, Bögel K, Cracera E, Edlinger E, Houwers D, Krauss H, Rady M, Rehacek J, Schiefer H G, Schmeer N, Tarasevich I V, Tringali G. Q fever in Europe: current aspects of aetiology, epidemiology, human infection, diagnosis and therapy (report of WHO Workshop on Q Fever) Infection. 1987;15:323–328. doi: 10.1007/BF01647731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allerdet-Servent A, Michaux-Charachon S, Jumas-Bilak E, Karayan L, Ramuz M. Presence of one linear and one circular chromosome in the Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 genome. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7869–7874. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7869-7874.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birkelund S, Stephens R S. Construction of physical and genetic maps of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar L2 by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2742–2747. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.2742-2747.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burger C. Ein rekombinantes Protein von Coxiella burnetii als Kandidat für eine Vakzine: Untersuchungen zum Vorkommen des omp-Gens und zur Biosynthese, Reinigung und Antigenität des rekombinanten OMP-Proteins. Vet. Med. thesis. Giessen, Germany: Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casjens S, Delange M, Ley III H L, Rosa P, Huang W M. Linear chromosomes of Lyme disease agent spirochetes: genetic diversity and conservation of gene order. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2769–2780. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2769-2780.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng S, Fockler C, Barnes W M, Higuchi R. Effective amplification of long targets from cloned inserts and human genomic DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5695–5699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chomczynski P. One-hour downward alkaline capillary transfer for blotting of DNA and RNA. Anal Biochem. 1993;201:134–139. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90185-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cianciotto N P, O’Connell W, Dasch G A, Mallavia L P. Detection of mip-like sequences and Mip-related proteins within the family Rickettsiaceae. Curr Microbiol. 1995;30:149–153. doi: 10.1007/BF00296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole S T, Saint Girons I. Bacterial genomics. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;14:139–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crespi M, Messens E, Caplan A B, Van Montagu M, Desomer J. Fasciation induction by the phytopathogen Rhodococcus fascians depends upon a linear plasmid encoding a cytokin synthase gene. EMBO J. 1992;11:795–804. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darlisson M G, Spencer M E, Guest J R. Nucleotide sequence of the sucA gene encoding the 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase of Escherichia coli K12. Eur J Biochem. 1984;141:351–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson B E, MacDougall J, Saint Girons I. Physical map of the linear chromosome of the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi 212, a causative agent of Lyme disease, and localization of rRNA genes. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3766–3774. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3766-3774.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frazier M E, Heinzen R A, Stiegler G L, Mallavia L P. Physical mapping of the Coxiella burnetii genome. Acta Virol. 1991;35:511–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanish J, McClelland M. Methylase-limited partial NotI cleavage for physical mapping of genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3287–3291. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.11.3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinzen R A, Frazier M E, Mallavia L P. Sequence and linkage analysis of the Coxiella burnetii citrate synthase-encoding gene. Gene. 1991;109:63–69. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90589-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinzen R A, Frazier M E, Mallavia L P. Coxiella burnetii superoxide dismutase gene: cloning, sequencing, and expression in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3814–3823. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3814-3823.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinzen R A, Howe D, Mallavia L P, Rockey D D, Hackstadt T. Developmentally regulated synthesis of an unusually small, basic peptide by Coxiella burnetii. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinzen R A, Mallavia L P. Cloning and functional expression of the Coxiella burnetii citrate synthase gene in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1987;55:848–855. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.4.848-855.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinzen R A, Mo Y Y, Robertson S J, Mallavia L P. Characterization of the succinate dehydrogenase-encoding gene cluster (sdh) from the rickettsia Coxiella burnetii. Gene. 1995;155:27–37. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00888-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinzen R A, Stiegler G L, Whiting L L, Schmitt S A, Mallavia L P, Frazier M E. Use of pulsed field gel electrophoresis to differentiate Coxiella burnetii strains. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;590:504–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb42260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendrix L R, Mallavia L P, Samuel J E. Cloning and sequencing of Coxiella burnetii outer membrane protein gene com1. Infect Immun. 1993;61:470–477. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.470-477.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoover T A, Vodkin M H, Williams J C. A Coxiella burnetii repeated DNA element resembling a bacterial insertion sequence. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5540–5548. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5540-5548.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jäger C, Willems H, Thiele D, Baljer G. Molecular characterization of Coxiella burnetti isolates. Epidemiol Infect. 1998;120:157–164. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897008510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohara Y, Akiyama K, Isono K. The physical map of the whole E. coli chromosome: application of a new strategy for rapid analysis and sorting of a large genomic library. Cell. 1987;50:495–508. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krause D C, Mawn C B. Physical analysis and mapping of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4790–4797. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.4790-4797.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leblond P, Redenbach M, Cullum J. Physical map of the Streptomyces lividans 66 genome and comparison with that of the related strain Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3422–3429. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3422-3429.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levene S D, Zimm B H. Separation of open circular DNA using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4054–4057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mallavia L P, Samuel J E, Frazier M E. The genetics of Coxiella burnetii: etiologic agent of Q fever and chronic endocarditis. In: Williams J C, Thompson H A, editors. Q fever: the biology of Coxiella burnetii. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 259–284. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masuzawa T, Sawaki K, Nagaoka H, Akiyama M, Hirai K, Yanagihara Y. Relationship between pathogenicity of Coxiella burnetii isolates and gene sequences of the macrophage infectivity potentiator (Cbmip) and sensor-like protein (qrsA) FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;154:201–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClelland M, Jones R, Patel Y, Nelson M. Restriction endonucleases for pulsed field mapping of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:5985–6005. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.15.5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mo Y Y, Mallavia L P. A Coxiella burnetii gene encodes a sensor-like protein. Gene. 1994;151:185–190. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90654-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mo Y Y, Cianciotto M P, Mallavia L P. Molecular cloning of a Coxiella burnetii gene encoding a macrophage infectivity potentiator (Mip) analogue. Microbiology. 1995;141:2861–2871. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-11-2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moos A, Hackstadt T. Comparative virulence of intra- and interstrain lipopolysaccharide variants of Coxiella burnetii in the guinea pig model. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1144–1150. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.5.1144-1150.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Musso D, Drancourt M, Osscini S, Raoult D. Sequence of quinolone resistance-determining region of gyrA gene for clinical isolates and for an in vitro-selected quinolone-resistant strain of Coxiella burnetii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:870–873. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Myers W F, Baca O G, Wisseman C L., Jr Genome size of the rickettsia Coxiella burnetii. J Bacteriol. 1980;144:460–461. doi: 10.1128/jb.144.1.460-461.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raoult D, Levy P Y, Harlé J R, Etienne J, Massip P, Goldstein F, Micoud M, Beytout J, Gallais H, Remy G, Capron J P. Chronic Q fever: diagnosis and follow up. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;590:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb42206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Römling U, Schmidt K D, Tümmler B. Large genome rearrangements discovered by the detailed analysis of 21 Pseudomonas aeruginosa clone C isolates found in environment and disease habitats. J Mol Biol. 1997;271:386–404. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samuel J E, Frazier M E, Mallavia L P. Correlation of plasmid type and disease caused by Coxiella burnetii. Infect Immun. 1985;49:775–779. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.3.775-779.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartz D C, Cantor C R. Separation of yeast chromosome sized DNAs by pulsed field gradient gel electrophoresis. Cell. 1984;37:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seshu J, McIvor K L, Mallavia L P. Antibodies are generated during infection to Coxiella burnetii macrophage infectivity potentiator protein (Cb-Mip) Microbiol Immunol. 1997;41:371–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1997.tb01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suhan M L, Chen S-Y, Thompson H A. Transformation of Coxiella burnetii to ampicillin resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2701–2708. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2701-2708.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suhan M, Chen S-Y, Thompson H A, Hoover T A, Hill A, Williams J C. Cloning and characterization of an autonomous replication sequence from Coxiella burnetii. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5233–5243. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5233-5243.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thiele D, Willems H. Is plasmid based differentiation of Coxiella burnetii in acute and chronic isolates still valid? Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:427–434. doi: 10.1007/BF01719667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thiele D, Willems H, Haas M, Krauss H. Analysis of the entire nucleotide sequence of the cryptic plasmid QpH1 of Coxiella burnetii. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:413–420. doi: 10.1007/BF01719665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thiele D, Willems H, Köpf G, Krauss H. Polymorphism in DNA restriction patterns of Coxiella burnetii isolates investigated by pulsed field gel electrophoresis and image analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 1993;9:419–425. doi: 10.1007/BF00157400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vodkin M H, Williams J C, Stephenson E H. Genetic heterogeneity among isolates of Coxiella burnetii. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:455–463. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-2-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vodkin M H, Williams J C. Overlapping deletion in two spontaneous phase variants of Coxiella burnetii. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:2587–2594. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-9-2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vodkin M H, Williams J C. A heat shock operon in Coxiella burnetii produces a major antigen homologous to a protein in both mycobacteria and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1227–1234. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1227-1234.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westphal A, Kok de H. 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex from Azotobacter vinelandii. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the gene encoding the succinyltransferase component. Biochemistry. 1990;187:235–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willems H, Ritter M, Jäger C, Thiele D. Plasmid-homologous sequences in the chromosome of plasmidless Coxiella burnetii Scurry Q217. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3293–3297. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3293-3297.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Willems H, Thiele D, Frölich-Ritter R, Krauss H. Detection of Coxiella burnetii in cow’s milk using the polymerase chain reaction. J Vet Med B. 1997;41:580–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1994.tb00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willems H, Thiele D, Krauss H. Sequencing and linkage analysis of a Coxiella burnetii 2.1 kb NotI fragment. Eur J Epidemiol. 1995;11:559–561. doi: 10.1007/BF01719308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Willems H. Adaptor PCR for the specific amplification of unknown DNA fragments. BioTechniques. 1998;24:26–28. doi: 10.2144/98241bm03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams J C, Waag D M. Antigens, virulence factors and biological response modifiers of Coxiella burnetii: strategies for vaccine development. In: Williams J C, Thompson H A, editors. Q fever: the biology of Coxiella burnetii. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 175–222. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ye F, Laigret F, Whitley J C, Citti C, Finch L R, Carle P, Renaudin J, Bove J M. A physical and genetic map of the Spiroplasma citri genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1559–1565. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoshida K, Strathmann M P, Mayeda C A, Martin C H, Palazzolo M J. A simple and efficient method for constructing high resolution physical maps. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3553–3562. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.15.3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu X, Raoult D. Serotyping Coxiella burnetii isolates from acute and chronic patients by using monoclonal antibodies. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;117:15–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zuber M, Hoover T A, Court D L. Analysis of a Coxiella burnetii gene product that activates capsule synthesis in Escherichia coli: requirement for the heat shock chaperone DnaK and the two-component regulator RcsC. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4238–4244. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4238-4244.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zuber M, Hoover T A, Powell B S, Court D L. Analysis of the rnc locus of Coxiella burnetii. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:291–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]