Abstract

Islet1 (Isl1) belongs to the LIM homeodomain transcription factor family. Its roles in differentiation of motor neurons and organogenesis of pancreas and heart have been revealed. However, less is known about its regulatory mechanism and the target genes. In this study, we identified interactions between Isl1 and Janus tyrosine kinase (JAK), as well as signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)3, but not Stat1 and Stat5, in mammalian cells. We found that Isl1 not only forms a complex with Jak1 and Stat3 but also triggers the tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak1 and its kinase activity, thereby elevating the tyrosine phosphorylation, DNA binding activity, and target gene expression of Stat3. In vivo, the tyrosine-phosphorylated Stat3 was colocalized with Isl1 in the nucleus of the mouse motor neurons in spinal cord after nerve injury. Correspondingly, electroporation of Isl1 and Stat3 into the neural tube of chick embryos resulted in the activation of a reporter gene expression controlled by a Stat3 regulatory sequence, and cotransfection of Isl1 and Stat3 promoted the proliferation of the mouse motor neuron cells. Our data suggest a novel role of Isl1 as an adaptor for Jak1 and Stat3 and reveal a possible functional link between LIM homeodomain transcription factors and the Jak-Stat pathway.

INTRODUCTION

LIM homeodomain transcription factors (LIM-HD) are a subset of homeodomain-containing transcriptional factors that, in cooperation with other transcription factors, regulate expression of genes that are critical in body patterning and generation of cell specificity during development in invertebrates and vertebrates (Dawid et al., 1995; Curtiss and Heilig, 1998). Most of the LIM-HD–encoding genes are expressed in the nervous system, suggesting that LIM-HD proteins function as regulators in the development and differentiation of the nervous system (Hobert and Westphal, 2000; Shirasaki and Pfaff, 2002). LIM is an acronym from the defining members of this family: Lin-11 from Caenorhabditis elegans, Isl-1 from rat, and Mec-3 from C. elegans. One of these founder members, Islet1 (Isl1), was originally isolated in a screen for proteins that can bind to the HD consensus sequence from the insulin gene enhancer (Karlsson et al., 1990) Subsequently, it was found to be expressed in all classes of motor neurons, and in each class its expression precedes that of other LIM homeobox genes, thus defining an early and common step in motor neuron differentiation (Karlsson et al., 1990; Ericson et al., 1992). In Isl1-null mutant mouse embryos, motor neurons fail to develop (Pfaff et al., 1996). In Drosophila, Isl1 is expressed in motor neurons and required for axonal extension to appropriate targets (Thor and Thomas, 1997). In addition, Isl1 also controls pituitary and pancreas organogenesis (Ahlgren et al., 1997; Sheng and Westphal, 1999). Recently, a key role of Isl1 in development of mouse heart also was reported (Cai et al., 2003). The characteristic features of LIM-HD proteins are two LIM domains consisting of two specialized zinc fingers, located at the N terminus of the homeodomain. Although the homeodomain with a helix-turn-helix structure binds to the regulatory DNA sequence of the target genes, the LIM domains are mainly involved in the protein–protein interaction that regulates activity of LIM-HD proteins (Curtiss and Heilig, 1998). In contrast to its critical roles during the embryonic development of several important organs and tissues, the precise mechanisms how Isl1 functions and its downstream targets are less clear.

The interleukin (IL)-6 cytokine family, such as ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), cardiotrophin, oncostatin M, and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), play pleiotropic roles in the immune and the hematopoietic systems, as well as in various aspects of neuronal development, including phenotype determination, survival, and response to nerve injury (reviewed in Schumann et al., 1999; Nakashima and Taga, 2002; Kamimura et al., 2003). The IL-6–type cytokines bind to their specific receptor subunits, which leads to homodimerization of glycoprotein (gp) 130, a common receptor subunit, or heterodimerization of gp130 with gp130-related receptors, which results in the activation of the gp130-associated Janus kinases (JAKs). JAKs subsequently phosphorylate the cytoplasmic region of gp130 that serve as docking sites for the recruitment of the signaling molecules containing the Src homology 2 (SH2) domain (Heinrich et al., 1998; Hirano et al., 2000). The signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)3 is one of the key signaling proteins (Akira et al., 1994) that is recruited to the phosphorylated gp130 via its SH2 domain and subsequently phosphorylated by JAKs on the tyrosine residue 705 at its C terminus. Stat3 then forms dimers via reciprocal interactions between the SH2 domain and the phosphorylated Tyr705, translocates to the nucleus where it binds to specific response elements in the regulatory region of target genes, thereby regulating their expression (Darnell et al., 1994; Lütticken et al., 1994; Stahl et al., 1994). Stat3 exerts pleiotropic effects in a variety of biological processes. Among others, Stat3 plays critical roles in the early mouse development as shown by early embryonic lethality in Stat3-null mice (Takeda et al., 1997). In addition, involvement of Stat3 in glial and neuron differentiation also was suggested (Bonni et al., 1997; Takizawa et al., 2001; Moon et al., 2002). In adult mice, Stat3 is essential for motor neuron survival after lesion (Schweizer et al., 2002). However, whether the Stat3 function is connected to the key transcription factors in the embryonic development, such as the LIM-HD genes, is currently unknown.

In an attempt to identify new genes in the IL-6–type cytokine signaling, we found that Isl1 physically interacts with Jaks and Stat3, which subsequently leads to the activation of Jak1 and Stat3. Our data therefore reveal a possible functional link between Isl1 and the Jak-Stat pathway in certain biological processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening

The intracellular domain of murine gp130 comprising 275 amino acids was amplified with primers containing a 5′ XhoI and a 3′ XmaI restriction enzyme site. The C-terminal 284 amino acids of the murine JAK2 JH1 domain were amplified with primers containing a 5′ XmaI and a 3′ KpnI restriction enzyme site. The resulting fragments were digested with XmaI, treated with calf intestinal phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), ligated, and used as a template to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplify the fusion protein, which was inserted into the pXJ40-FLAG–tagged expression vector for mammalian expression. This construct was further used as a template for PCR amplifications with primers containing a 5′ EcoRIanda3′ SalI restriction enzyme site to clone it into the pGBKT7 vector, containing the GAL4 DNA-binding domain as bait. This plasmid was transformed into the Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain AH109 and tested for expression and autophosphorylation ability by using Western blot analysis. Subsequently, the yeast two-hybrid screen was performed using an embryonic mouse MATCHMAKER cDNA library from E11 (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) as described previously (Lufei et al., 2003).

Cell Culture and DNA Transfections

The African green monkey kidney epithelial cell line COS-1, the human hepatoma cell line HepG2, and the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y were maintained in DMEM with 1000 mg/l glucose containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 ng/ml streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 10 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.3. Cells were transfected in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) by using LipofectAMINE 2000 (Invitrogen) or FuGENE (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) for HepG2 cells, following the manufacturers' instructions. When required, cells were stimulated using 40 ng/ml human IL-6 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 100 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), or 2.7 × 106 U/ml human LIF. The NSC-34 hybrid cell line, obtained by a fusion of motor neuron-enriched embryonic mouse spinal chord cells with mouse neuroblastoma N18TG cells, was a gift from N. R. Cashman (Cashman et al., 1992). Cells were routinely maintained in DMEM, supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated FBS, 1 mM l-glutamine, and antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 ng/ml streptomycin). The human fibrosarcoma cell line deficient in Jak1 (U4A) and its parental cell line 2fTGH, gifts from Z. L. Wen (Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore) were maintained in DMEM containing 4000 mg/ml glucose, supplemented with 10% FBS, in the presence of 250 μg/ml hygromycin and 700 μg/ml G418 (Geneticin) (McKendry et al., 1991). Sodium orthovanadate was activated for maximal inhibition of protein phospo-tyrosyl-phosphatases (Gordon, 1991). Cells were treated with 120 μM Na3VO4 for 15 h before lysis. The protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor Genistein (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used at a final concentration of 100 μM, and cells were treated for 13 h before lysis.

Construction of Plasmids

The expression vector for murine Isl1 was obtained by PCR amplification of the entire coding sequence from a murine embryonic cDNA library. Isl1 was inserted into the pXJ40-HA–tagged vector or the pXJ40-Myc–tagged vector (Ma et al., 2003) via the 5′ BamHI site and the 3′ XhoI site. The mutants spanning different domains of murine Isl1 (Lim1 + 2, aa 17–132; C, aa 151–349; HOX+, aa 151–239; HOX, aa 181–239; and GLN, aa 240–349) were constructed by PCR by using the wild-type plasmid as a template and inserted via the same restriction enzyme sites: The gp130 was constructed by PCR by using HepG2 cDNA as a template to amplify the 274 C-terminal amino acids of the human gp130 and inserting them into the pXJ40-FLAG–tagged or Myc-tagged vector via the 5′ BamHI site and the 3′ XhoI site. The expression vectors for the murine Jak1 and the dominant negative form of Jak1 (K907E) were gifts from J. Ihle (Saint Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN). The various Stat3 deletion mutations, the glutathione S-transferase (GST)-Stat3 fusion protein, and the Stat1 and Stat5 constructs have been described previously (Zhang et al., 2000; Lim and Cao, 2001; Lufei et al., 2003; Ma et al., 2003). All PCR products were checked by sequencing.

Vector-based Stat3 Small Interfering RNA (siRNA)

The vector pBS/U6, used for the DNA vector-based RNA interference (RNAi), was obtained from Dr. Y. Shi (Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA). The generation of pBS/U6 has been described previously (Sui et al., 2002). A 21-nucleotide (nt) coding sequence for human Stat3 was selected, corresponding to nucleotides 1662–1681 (GenBank accession no. NM_139276), which began with GG. BLAST search showed that it did not have significant sequence homology with other genes. Insertion of the individual repeat motifs into pBS/U6 was achieved in two separate steps. Oligo 1 was first inserted into pBS/U6 vector digested with ApaI (and subsequently blunted and filled in with Klenow) and HindIII. The inverted motif that contained the 6-nt spacer and five Ts (oligo 2) was then subcloned into the HindIII and EcoRI sites of the intermediate plasmid to generate pBS/U6-hu Stat3 siRNA. Oligo 1 was 5′ GGCGTCCATCCTGTGGTACAA 3′ (forward) and 5′ AGCTTTGTACCACAGGATGGACGCC 3′ (reverse); oligo 2 was 5′ AGCTTTGTACCACAGGATGGACGCCCTTTTTG 3′ (forward) and 5′ AATTCAAAAAGGGCGTCCATCCTGTGGTACAA 3′ (reverse). The inserted oligonucleotides were confirmed by sequencing.

Antibodies, Immunoprecipitation, GST Pull-Down, and Immunoblotting

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope, the Myc-tag, Jak1, Stat3, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), and monoclonal antisera against the Myc and HA epitope were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The monoclonal antibodies against Stat3, GST, Jak1, and calnexin were purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). The antibodies against stathmin and the phosphotyrosine 705-Stat3–specific antibody were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). The monoclonal antisera against Isl1 (clone 39.4D5 and clone 40.2D6) were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA), and the polyclonal antibody against Isl1 was obtained from T. M. Jessell (Columbia University, New York, NY). The antibodies against the FLAG-tag (M2) and the secondary antibodies against rabbit and mouse antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For immunoprecipitation, 500–800 μg of total cell lysates was used, and the experiments were performed as described previously (Lufei et al., 2003). Signals were normally detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). GST pull-down was performed as described previously (Novotny-Diermayr et al., 2002). Blots were stripped using the Restore buffer from Pierce Chemical (Rockford, IL), according to the manufacturer's instructions before being reprobed. All the IP/Blot, GST pull-down, and Western blot experiments were repeated at least three times, except those shown in Figure 7 that were repeated twice.

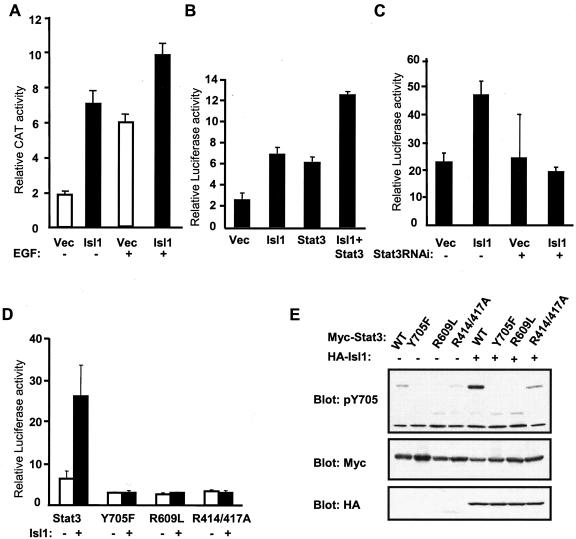

Figure 7.

Detection and characterization of Jak1–Isl1–Stat3 complex. (A) COS-1 cells were cotransfected with Jak1, FLAG-Stat3, and HA-Isl1 as labeled. The cell lysates were either immunoprecipitated with HA or FLAG antibody, and the associated proteins were detected by blotting with anti-Jak1, HA, or FLAG antibody as labeled on the left. The expression of these three proteins in total cell lysates (TCL) were monitored by Western blotting and indicated at the bottom panel by arrows. (B) Isl1 enhances Jak1–Stat3 interaction. COS-1 cells were transfected by Jak1 and FLAG-Stat3 with or without cotransfection of Isl1. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with Jak1 antibody and blotting was performed with Stat3, HA, or Jak1 antibody as described in A. The expression of the transfected proteins in TCL was measured by Western blotting shown in the first two lanes of each panel as labeled. (C) Effect of Isl1 on the Jak1 Tyr-phosphorylation. SH-SY5Y cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing Jak1, FLAG-Stat3, and/or HA-Isl1. The IP/Blot experiments were conducted as described in A shown in top two panels. The expression of FLAG-Stat3 and HA-Isl1 are shown in two bottom panels. (D) Effect of Isl1 on the Stat3 Tyr-phosphorylation. SH-SY5Y cells were cotransfected with Jak1, GST-Stat3, and/or HA-Isl1. GST pull-down experiments were performed, and the blot was probed by antibodies as labeled. The expression of HA-Isl1 and Jak1 were detected by Western blot of the TCL. (E) Measurement of possible tyrosine phosphorylation of Isl1 by Jak1. SH-SY5Y cells were transfected by HA-Isl1 with or without Jak1. The cells were either left untreated or treated with 120 μM of Na3VO4 before harvest. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with HA antibody and blotted with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 (top). The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-HA antibody (bottom). The position of Jak1 and HA-Isl1 is indicated by arrowheads.

Nuclear Extracts, Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSAs), and Cellular Fractionation

Nuclear extracts were prepared and used in DNA binding assays as described previously (Zhang et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2003). Briefly, 10 μg of nuclear extract was used in the DNA binding assays with 32P m67-hSIE, the high-affinity binding site of Stat3 as a radiolabeled probe. Complexes were resolved on 5% native polyacrylamide gels and exposed to film overnight. Cellular fractionation was performed as described previously (Ma et al., 2003) with some modifications. After the nuclear extract was removed the remaining pellet was resuspended in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.3, 1.25 mM EDTA, pH 8, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton-X 100, 0.2% NaF, and 0.1% Na3VO4), incubated for 5 min at room temperature, and briefly vortexed. After a final spin at 16,100 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was transferred into a new tube and used as membrane-enriched fraction.

Reporter Gene Assays

The cells were cotransfected with Stat3 and/or Isl1 expression plasmids with reporter plasmid pSIE-CAT containing three copies of SIE and pCMV-β-gal for normalization. The chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) assay was performed as described previously (Jain et al., 1998). The firefly luciferase reporter gene constructs m67-hSIE-luc and pGL3 α2-M 215luc were gifts from J. Bromberg (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY) and P. C. Heinrich (RWTH Aachen, Universitats Klinikum, Aachen, Germany), respectively. The luciferase assays were carried out as described previously (Lufei et al., 2003).

Sciatic Nerve Lesion and Immunofluorescence

In total, 30 albino strain (BALBc/ByJ) mice were used for the experiments. For animal handling and caring, the International Guiding Principles for Animal Research stipulated by the World Health Organization and adopted by the Laboratory Animal Center, National University of Singapore, were followed. All mice were bred and supplied by the Laboratory Animal Center, National University of Singapore. Three days after birth (P3), the mice were anesthetized using cold anesthesia, and the left sciatic nerve was crushed at the midthigh level by using blunt forceps, but the right side sciatic nerve was not treated and served as control. After recovery from the anesthesia, the pups were returned to their mother. At 12 and 24 h after surgery, the spinal cord at the level of L5 was removed and processed for immunohistochemistry. Tissue sections were double stained with phospho-Y705 Stat3 and Isl1 antibodies. In brief, the mice were terminally anesthetized (2% chloral hydrate; 1 ml/100 g body weight i.p.) and perfused transcardially with a fixative containing 2% paraformaldehyde. Spinal cord sections were cut at 20 μm on a cryostat and thaw-mounted onto gelatinized slides. Sections were blocked using 3% normal goat serum for 1 h, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained using a rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-Y705 Stat3 antibody (1:200) and/or a mouse monoclonal anti-Isl1 (1:200) antibody overnight. After another wash with PBS, the sections were stained with Cy3- or fluorescein isothiocyanate-coupled secondary antibodies (both 1:200) (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, and Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, respectively). After three more washes with PBS, the sections were mounted in Antifade medium (Gel/Mount; Biomeda, Foster City, CA) and examined using a confocal microscope (Bio-Rad MRC 1024). The figures were processed with Adobe Photoshop software.

In Ovo Electroporation

Chick embryos of stage 11–12 (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1951) were used for electroporations. Eggs were windowed, and the DNA solution (1 μg/μl) was injected into the lumen of the neural tube in the trunk region together with pHcRed1-N1 as tracer and then electroporated into the left-hand side of the neural epithelium. In all experiments, the control side was to the right. A series of electric pulses (6 pulses, 25 V, 30 ms) were carried out with a square wave electroporator (BTX ECM830). Eggs were reincubated for 24 h, and embryos with HcRed expression were selected for cryosection and then analyzed by immunostaining. The cotransfected embryo sections were double immunostained with polyclonal antibody against Isl1 (1:2000) and monoclonal antibody against FLAG (1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich) as primary antibodies, and with goat anti-rabbit-Cy5 (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) and goat-anti mouse-AMCA (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) as the secondary antibodies.

Cell Growth/Proliferation Assay

The assay was performed using the cell proliferation kit II (XTT) from Roche Diagnostics as described previously (Lufei et al., 2003).

RESULTS

Identification of Isl1 as a JAK Interacting Protein

The original goal of this experiment was to identify proteins interacting with the Tyr-phosphorylated (active) form of gp130, the common receptor subunit of IL-6–type cytokines. To this end, a gene fusion between the intracellular region of gp130 and the kinase domain of Jak2 (JH1) that retains a high enzymatic activity when expressed alone (Saharinen et al., 2003) was generated (gp130-JH1) and used as bait to screen for the interacting proteins in a yeast two-hybrid system (Durfee et al., 1993). This fusion protein expressed in yeast was indeed phosphorylated on tyrosine as confirmed by Western blot analysis by using an anti-phospho-Tyr antibody. Positive clones that produced proteins interacting with the bait were identified. Four clones encoded LIM domain-containing proteins and among them, two encoded the full-length murine LIM/Homeobox protein Isl1. The specificity of Isl1 and gp130-JH1 interaction in yeast was further confirmed by survival in the selection medium and by the galactosidase reporter assays as described previously (Lufei et al., 2003).

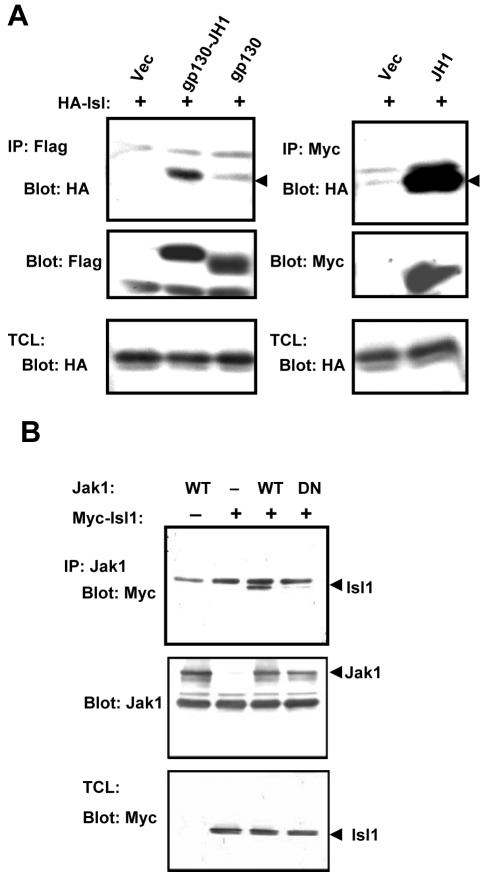

To verify and further characterize the interaction of Isl1 and gp130-JH1 in mammalian cells, we generated FLAG-tagged gp130 plasmids expressing either the intracellular region alone (FLAG-gp130) or a fusion with JH1 (FLAG-gp130-JH1), as well as a Myc-tagged JH1 alone (Myc-JH1). These plasmids were cotransfected with HA-tagged Isl1 or a control plasmid into COS-1 cells, and the protein–protein interaction was analyzed by immunoprecipitation (IP)/Western blot (blot) assay. The results indicated that Isl1 coimmunoprecipitated with the fusion protein gp130-JH1 but not with the vector control. Interestingly, only small amounts of Isl1 coprecipitated with gp130. In contrast, large amounts of Isl1 coprecipitated with JH1 (Figure 1A, top). The data implicate that the major interaction takes place in the JH1 region. We next examined whether Isl1 interacted with the full-length Jaks. We chose Jak1 for further studies because Jak1 plays a predominant role in the IL-6 signaling (Guschin et al., 1995). We found that Isl1 bound to the full-length Jak1 but not to a kinase-inactive Jak1 (Figure 1B). These results suggest that Isl1 may not interact with gp130. Instead, it interacts with Jak1, and the kinase activity of Jak1 seems to be required for such interaction.

Figure 1.

Isl1 interacts with Jak1 in transfected cells. (A) HA-tagged Isl1 and the FLAG-tagged gp130-JH1, gp130, or the empty vector was transiently expressed in COS-1 cells. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an antibody against the FLAG tag and blotted with anti-HA to detect the coprecipitated Isl1 (shown on top left, pointed by an arrowhead). The blot was stripped and reprobed with FLAG antibody for IP efficiency. For the right panels, Myc-tagged JH1 with HA-Isl1 or the respective empty vectors were cotransfected into COS-1 cells. The cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc and blotted with anti-HA antibody. The blot was reprobed with anti-Myc antibody. The expression of HA-Isl1 was monitored in the total cell lysates (TCL) by Western blotting with the HA antibody (bottom). (B) The wild-type murine Jak1 (WT) or the dominant negative mutant K907E (DN) was cotransfected with Myc-tagged Isl1 into COS-1 cells. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with Jak1 antibody and the coprecipitated Isl1 was detected by Western blotting with anti-Myc antibody. After stripping, the blot was reprobed with a monoclonal Jak1 antibody (middle), and the expression of Isl1 in TCL is shown (bottom).

Isl1 Induces Tyr705-Phosphorylation and DNA Binding Activity of Stat3

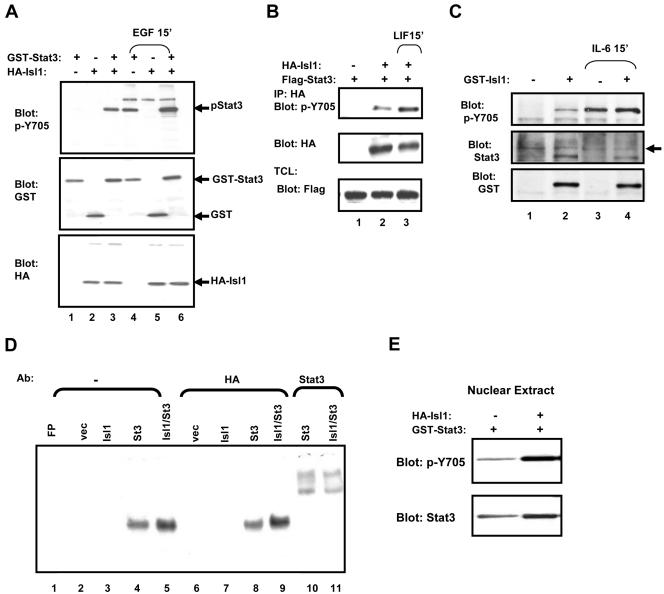

Stat3 is a key mediator in gp130 signaling and a major target of JAKs. We therefore examined the effect of Isl1 on Stat3. Interestingly, we found that coexpressing Isl1 and Stat3 led to Tyr705 phosphorylation of Stat3 in unstimulated COS-1 cells, which is equal to the phosphorylation of Stat3 induced by EGF (Figure 2A, top, lanes 3 and 4). This EGF-induced phosphorylation of Stat3 was further enhanced in the presence of Isl1 (lane 6). Similarly, Isl1 expression triggered Tyr-phosphorylation of transfected Stat3 in the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y, and LIF treatment further enhanced this phosphorylation (Figure 2B, top, lanes 2 and 3). Furthermore, we observed that Isl1 also induced Tyr-phosphorylation of the endogenous Stat3 in the SY5Y cells (Figure 2C, lane 2), which was further enhanced by IL-6 stimulation (lane 4). To further confirm the Tyr-phosphorylation of Stat3 trigged by Isl1 is functional, we measured the DNA binding activity of Stat3 by EMSA by using the Stat3 high-affinity binding site (hSIE) as a probe. Although the Tyr-phosphorylation of Stat3 was either low (Figure 6A) or sometimes undetectable (Figure 2A) in the total cell lysates of the unstimulated cells, a basal level of the nuclear Stat3 can be detected in the DNA binding assay (Figure 2D, lane 4). This DNA binding activity was elevated by cotransfection with Isl1 (lane 5). This was consistent with the tyrosine phosphorylation status of the nuclear Stat3 shown in Figure 2E. We next examined the specificity of the protein–DNA complex with supershift assay. The complex can be supershifted by anti-Stat3 (Figure 2D, lanes 10 and 11) but not by anti-HA antibody (lanes 8 and 9). Together, these data suggest that Isl1 stimulates Tyr705 phosphorylation of Stat3 that leads to an increase in its DNA binding activity. On the other hand, the transfected HA-Isl1 is neither directly interacting with Stat3 binding element (lane 3) nor present in the Stat3-DNA complex shown by lacking supershift with anti-HA antibody (lane 9).

Figure 2.

Isl1 induces Tyr-phosphorylation and DNA binding activity of Stat3. (A) COS-1 cells were transfected with GST-Stat3 and/or HA-Isl1 as indicated on the top. Cells were left unstimulated or treated with EGF for 15 min. Total cell lysates (TCL) were subjected to Western blotting with the antibodies as indicated on the left to measure Stat3 Y705-phosphorylation and expression of the different plasmids. (B) The SH-SY5Y cells were cotransfected with FLAG-Stat3 and HA-Isl1 (+) or the empty HA-vector (–) and treated with LIF as indicated on top. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using the HA antibody and tested for the phosphorylation of Stat3 by using anti-pY705-Stat3 antibody. IP efficiency and expression of Stat3 and Isl1 were examined using the antibodies as indicated on the left. (C) The SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with GST-Isl1 (+) or the empty GST-vector (–) and the Tyr-phosphorylation of the endogenous Stat3 was examined by Western blot analysis with antibodies shown on the left. (D) Ten micrograms of nuclear extract from COS-1 cells transfected with the plasmids indicated on top was used in an EMSA with 32P m67-hSIE as a probe. Samples were incubated without (–) or with 0.2 μg of polyclonal antibody against the HA tag or Stat3 for 15 min before the addition of the radiolabeled probe as indicated on top. FP, free probe. (E) COS-1 cells were transfected with GST-Stat3 in the absence (–) or the presence (+) of Isl1. The nuclear extracts were prepared, and the expression and phosphorylation of Stat3 were analyzed by Western blotting with the antibodies as labeled.

Figure 6.

Enhanced Stat3 tyrosine-phosphorylation by Isl1 is dependent on Jak1. (A) COS-1 cells were transfected with FLAG-Stat3 and/or HA-Isl1 as indicated on top. Cells were pretreated overnight with 100 μM Genistein or 120 μM Na3VO4 before harvest. The tyrosine-phosphorylated Stat3 and its expression in transfected cells were monitored by Western blotting. (B) Jak1 deficient U4A cells (Jak1–/–) and its parental cell line 2fTGH (control cell) were transiently transfected with FLAG-Stat3 and/or HA-Isl1, and the level of Tyr-phosphorylation and expression of Stat3 were monitored by Western blotting.

Isl1 Stimulates Stat3 Transcriptional Activity and Its Target Gene Expression

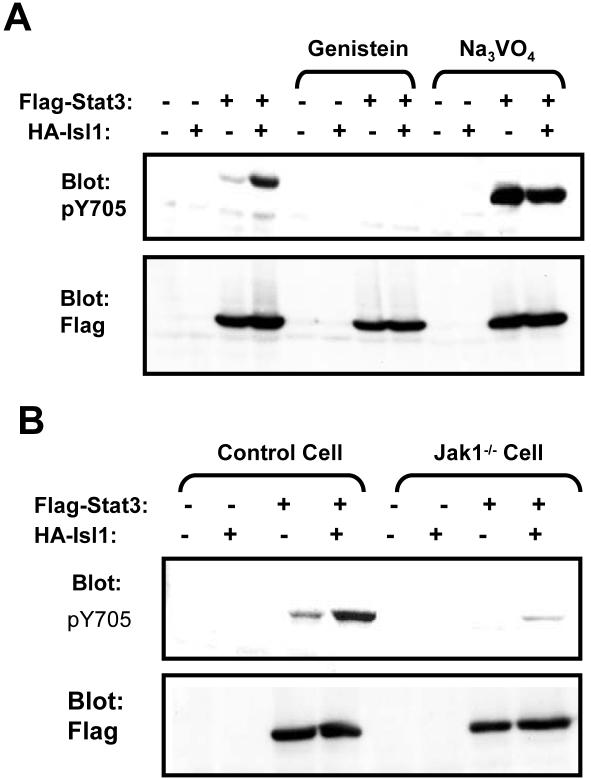

Next, the effect of Isl1 on the transcriptional activity of Stat3 and its target gene expressions was investigated. We first examined whether Isl1 affected the endogenous Stat3 transcription activity in various cell lines that were transfected with a reporter gene containing three copies of hSIE followed by the CAT gene (Jain et al., 1998). In COS-1 cells, CAT activity was increased 3.5-fold by Isl1 in unstimulated conditions, which was higher than that stimulated by EGF (3-fold). EGF treatment, in the presence of Isl1, further enhanced this activity to fivefold (Figure 3A). In addition, Isl1 stimulated the endogenous Stat3 activity (2.7-fold) in SH-SY5Y cells (our unpublished data).

Figure 3.

Isl1 promotes transactivation of Stat3 and its target gene expression. (A) Cells were cotransfected with empty reporter vector (empty bar) or Isl1 (black bar) together with plasmid pSIE-CAT and pCMV-β-gal and left untreated or treated with EGF as indicated. CAT assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The CAT activity from three independent transfection experiments were quantified with Bio-Rad GS700 imaging densitometer, and the relative CAT values are indicated on the y-axis with the SD given as the error bar. (B) HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with the HA vector (Vec), HA-Isl1 (Isl1), Stat3, or HA-Isl1 and Stat3 together with the pGL3-α2M-215luc firefly reporter gene construct and the pRL-TK Renilla luciferase construct for normalization. Relative luciferase values are indicated on the y-axis. Values represent the means of six samples with the SD given as the error bar. One of three independent sets of experiments is shown. (C) COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with the HA vector (Vec) or HA-Isl1 (Isl1), and a vector-based Stat3 RNAi (+) or a empty vector as control (–), together with the pGL3-m67 firefly luciferase reporter gene construct, and the pRL-TK Renilla luciferase construct for normalization. (D) COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with the HA vector (–) or HA-Isl1 (+), and the wild-type or various point mutants of Stat3 (as indicated at the bottom), together with the pGL3-m67 firefly luciferase reporter gene construct, and the pRL-TK Renilla luciferase construct for normalization. (E) COS-1 cells are transfected with various Myc-tagged Stat3 constructs alone or together with HA-tagged Isl1 (as labeled on top). Western blot analysis of total cell lysates is performed with antibodies indicated on the left.

IL-6 stimulates expression of many acute phase proteins, including α2-macroglobulin (α2-M) in hepatocytes, and Stat3 is the major mediator for this (reviewed in Heinrich et al., 2003). We next examined whether Isl1 can enhance the transcription of α2-macroglobulin by using a reporter gene containing the firefly luciferase gene driven by α2-microglobulin promoter by cotransfection in HepG2 cells under normal growth conditions. Expression of the α -macroglobulin reporter gene increased 2.8-fold by cotransfection of Isl1, representing the activity of endogenous Stat3. Overexpression of Stat3 alone increased the α2-macroglobulin expression to 2.4-fold, which was further enhanced to fivefold when cells coexpressed both Isl1 and Stat3 (Figure 3B).

To examine the possibility that Isl1 itself is able to activate the reporter gene, we cotransfected COS-1 cells with Isl1 and a luciferase reporter gene controlled by four copies of hSIE (m67-hSIE-luc) in the presence of a vector control or a plasmid containing Stat3 siRNA to deplete the endogenous Stat3. The reporter assay showed that with the control plasmid, Isl1 induced reporter gene expression to twofold. However, in the presence of Stat3 siRNA, Isl1 did not show this effect (Figure 3C). Therefore, it is likely that Isl1 induces Stat3 regulatory gene expression via activating Stat3. This is in agreement to the results of EMSA described above. To further verify this point, we examined the effect of Isl1 on the Stat3 mutants, which harbor distinct point mutations in the tyrosine phosphorylation site (Y705F), SH2 domain (R609L), or DNA binding domain (R414/417A), that lack transcriptional activity (Zhang et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2003). The wild-type and the mutant Stat3 were transfected into COS-1 cells with the luciferase reporter gene m67-hSIE-luc in the absence or presence of Isl1. As shown in Figure 3D, in the absence of Isl1 (empty bar), a low basal level of transcriptional activity of the wild-type Stat3 was detected, which, however, was increased approximately fivefold in the presence of Isl1 (black bar). In contrast, the different Stat3 mutants exhibited a very low background activity that was not enhanced by coexpression of Isl1. Consistent to these results, we observed that Isl1 could not stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation of the mutants Y705F and R609L in contrast to the wild-type Stat3 (Figure 3E). Although a very weak Tyr-phosphorylation in mutant R414/417A was detected, this mutant failed to enter the nucleus and bind DNA; therefore, it is defective in its transcriptional activity (Ma et al., 2003). These results demonstrate that Isl1 specifically stimulates Stat3 transcriptional activity.

Interaction between Isl1 and Stat3 In Vivo

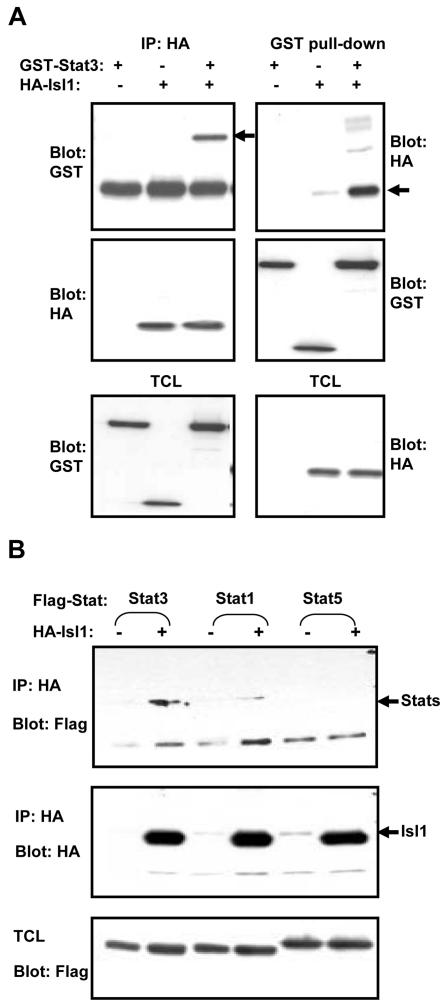

It is possible that Isl1 exerts its effect on Stat3 via a physical interaction. We further investigated this by cotransfection of HA-tagged Isl1 and GST-Stat3 fusion protein followed by IP/Blot or GST pull-down experiments. As shown in Figure 4A, Stat3 coimmunoprecipitated with Isl1 (top left, see arrow). The bands below in all three lanes are likely the nonspecific proteins coprecipitated with HA-antibody and/or protein A beads and reacted with GST antibody in the Western blot. In a reciprocal experiment, Isl1 could be pulled down by GST-Stat3 by using GST antibody-conjugated beads (top right). We also examined whether the Isl1 interacts with other Stat family members. We found that in comparison with Stat3, Isl1 weakly interacted with Stat1 and did not interact with Stat5 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Isl1 interacts with Stat3 in vivo. (A) COS-1 cells were transfected with GST-Stat3 and HA-Isl1 (+) or the respective empty vectors (–). Cell lysates were subjected to either immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody or GST pull-down as indicated. Complexes were resolved on 7.5% SDS-PAGE gels and probed with GST or HA antibody. The coprecipitated GST-Stat3 and HA-Isl1 are indicated by arrows. The expressions of GST-Stat3 and HA-Isl1 were monitored in TCL by Western blotting. (B) COS-1 cells were transfected with different FLAG-tagged Stat constructs together with HA-Isl1 (+) or HA-vector (–) as indicated and immunoprecipitated with HA antibody and blotted with anti-FLAG or anti-HA antibody. The expressions of Stat proteins were monitored in total cell lysates (TCL) as shown in the bottom panel.

Mapping the Binding Domains Mediating Interaction between Isl1 and Stat3

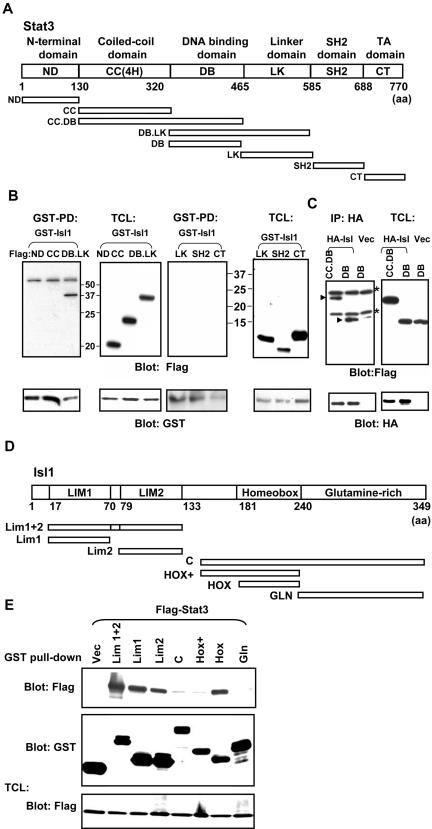

Stat3 contains several functional domains including the N-terminal domain (ND), coiled-coil domain with four α-helices (CC), DNA binding domain (DB), linker domain (LK), SH2 domain, and C-terminal domain (CT) (Becker et al., 1998). To define the domain that binds to Isl1, we generated a series of FLAG-tagged truncation mutants of Stat3 that encode individual domains or their combinations as illustrated in Figure 5A. The mutant proteins were coexpressed with GST-tagged Isl1 (GST-Isl1), and GST pull-down experiments were performed followed by blotting with FLAG antibody. The results indicate that GST-Isl1 only associated with ST3-DB.LK, a truncated Stat3 protein consisting of the DNA binding and the linker domains, whereas no interaction was detected between Isl1 and other domains, such as ND, CC, LK, SH2, and CT (Figure 5B). Because DB.LK consists of the DNA binding domain and the linker domain, but the latter did not interact with Isl1, it is likely that DB is the binding domain. To verify this, FLAG-tagged plasmids containing either DB alone or together with the coiled-coil domain (CC.DB) were cotransfected with HA-tagged Isl1. HA-Isl1 was used to replace GST-Isl1, because the DB protein exhibits a certain degree of nonspecific binding to the GST beads (Lufei et al., 2003). The results in Figure 5C showed that DB is the site of interaction with Isl1.

Figure 5.

Mapping the interacting domains of Stat3 and Isl1. (A) Schematic diagram of murine Stat3 and the deletion mutants used. (B) COS-1 cells were cotransfected with the various FLAG-tagged Stat3 constructs together with GST-Isl1, and lysates were subjected to a GST pull-down (GST-PD). Complexes were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels, and interacting domains were detected by Western blotting with anti-FLAG antibody. The blots were subsequently stripped and reprobed with anti-GST to determine the pull-down efficiency. Expression levels of the transiently transfected proteins in total cell lysates (TCL) also were examined. The molecular weight markers are indicated. (C) Cells were cotransfected with FLAG-tagged Stat3 constructs and HA-Isl1. After immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody, interacting domains were detected by Western blotting with FLAG antibody. Efficiency of the immunoprecipitation and expression of proteins were tested by Western blotting with the antibodies indicated. The arrows indicate FLAG-tagged Stat3 mutants, whereas the nonspecific proteins were labeled by asterisk (*). (D) Schematic diagram of murine Isl1 and the different deletion constructs. (E) COS-1 cells were transfected with FLAG-Stat3 together with the various GST-tagged Isl1 mutants. The experiment was performed as described in B.

Isl1 consists of four domains: LIM1, LIM2, Homeobox (Hox), and a glutamine-rich domain (GLN) (Karlsson et al., 1990). We next delineated the interacting domain on Isl1. Constructs expressing GST fusion proteins of different domains of Isl-1 were generated (Figure 5D) and coexpressed with the FLAG-tagged Stat3. Results from GST pull-down experiments showed that LIM1 and LIM2 domains together strongly interacted with Stat3, whereas LIM1 alone exhibited higher binding affinity than LIM2. In addition, the Hox domain also interacted with Stat3, but the C-terminal GLN region did not. Interestingly, ∼30 amino acids (151–181) adjacent to the N terminus of Hox domain (Hox+) displayed an inhibitory role in Isl1–Stat3 interaction because the presence of this region either in Hox (Hox+) or the C-terminal half (C) of Isl1 abolished the interaction to Stat3 (Figure 5E). Therefore, both LIM domains, especially LIM1, and the homeodomain are likely to be the major regions for Stat3 binding.

Jak1 Is Essential for the Isl1-induced Stat3 Tyr-Phosphorylation

Interaction of Stat3 and Isl1 alone could not explain the effect of Isl1 on the phosphorylation of Stat3. Next, we investigated the possible mechanism for this. First, we examined whether Isl1-induced Stat3 Tyr-phosphorylation was mediated by activation of a tyrosine kinase (TK) or inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPase). After transfection, the cells were treated with either a TK inhibitor, Genistein, or with a PTPase inhibitor, sodium vanadate. We found that inhibition of TK destroyed the Stat3 Tyr-phosphorylation either induced by Isl1, or its basal phosphorylation in the absence of Isl1. In contrast, inhibition of PTPase significantly enhanced Stat3 phosphorylation regardless of the presence or absence of Isl1 (Figure 6A). These results suggest that it is more likely that a TK is required for Isl1-triggered Stat3 Tyr-phosphorylation, although inhibition of a PTPase by Isl1 could not be completely excluded. Because we had observed that Isl1 interacts with Jak1, we reasoned that Isl1-stimulated Stat3 Tyr-phosphorylation may be mediated by Jak1. To test this possibility, we measured the effect of Isl1 on Stat3 Tyr-phosphorylation in a previously reported Jak1-deficient cell line U4A. Indeed, Isl1-induced Stat3 Tyr-phosphorylation was drastically reduced in these cells in comparison with that in the control cells, 2fTGH (Figure 6B, top), indicating that Jak1 plays an essential role in the Isl1-stimulated Stat3 phosphorylation.

Jak1, Isl1, and Stat3 Form a Complex

Proteins containing LIM domains are generally regarded as being mediators of protein–protein interactions by acting as scaffolds or molecular adaptors linking various proteins together. Because Isl1 interacts with Jak1 and Stat3 and promotes Stat3 phosphorylation, we speculate that these three proteins may form a complex. To investigate this possibility, plasmids expressing HA-Isl1, FLAG-Stat3, and Jak1 were cotransfected, and their interactions were tested. The results showed that both Jak1 and Stat3 can be coprecipitated with Isl1. Similarly, Jak1 and Isl1 also can be coprecipitated with Stat3 (Figure 7A). The data suggest that Isl1 may function as an adaptor protein that brings Jak1 and Stat3 in proximity and thereby facilitates Stat3 phosphorylation by Jak1.

To further verify this hypothesis, we cotransfected Stat3 and Jak1 in the presence or absence of Isl1 and tested the effect of Isl1 on the interaction of Stat3 and Jak1. We found that in the presence of Isl1, the Stat3–Jak1 interaction increased in comparison with that in the absence of Isl1 (Figure 7B, top). The associated Isl1 is shown in the middle panel (lane 4). Next, we examined whether Isl1 has any effect on the Jak1 Tyr-phosphorylation and its kinase activity. We observed that Jak1 alone did not show Tyr-phosphorylation. However, the Tyr-phosphorylation was stimulated by cotransfection with Isl1, as well as Stat3, to a lesser extent. Interestingly, the Tyr-phosphorylation of Jak1 was synergistically enhanced by cotransfection with Isl1 and Stat3 together (Figure 7C). In agreement with these results, we detected a strong increase of Stat3 Tyr-phosphorylation by cotransfection of Jak1 and Isl1 (Figure 7D). The results suggest that Isl1 is able to form a complex with Jak1 and Stat3. This complex further stimulates autophosphorylation and kinase activity of Jak1 and causes a concomitant increase in Stat3 Tyr-phosphorylation.

Last, we tested whether Isl1 is phosphorylated by Jak1. We transfected cells with Jak1 and Isl1 and treated the cells with sodium vanadate to avoid the possibility of a rapid dephosphorylation of Is1. We could not detect a clear Tyr-phosphorylation of Isl1 either alone or cotransfected with Jak1 in the absence or the presence of sodium vanadate, (Figure 7E, top). In contrast, we could observe Tyr-phosphorylation of the endogenous (lanes 1 and 2) and transfected Jak1 (lanes 3 and 4) that coprecipitated with Isl1. The expression of Isl1 is shown in the bottom panel. These data suggest that Isl1 is unlikely a substrate of Jak1, at least under these conditions.

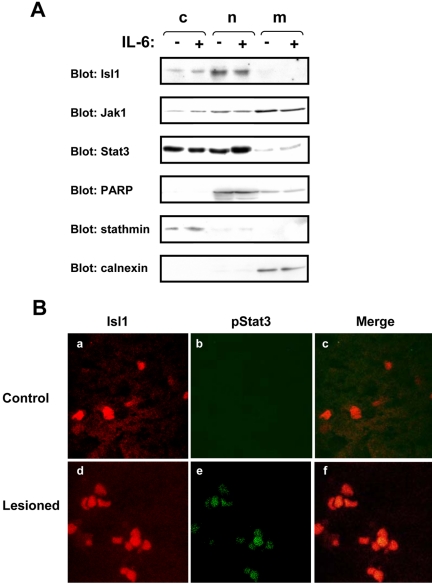

Cellular Localization of the Interacting Proteins

Isl1 is known to be a nuclear protein, whereas Stat3 is a latent cytoplasmic transcription factor that is translocated to the nucleus upon ligand stimulation. However, Jaks are cytoplasmic proteins that associated with the cytokine receptors on the membranes, although a constitutive nuclear localization of Jaks also was previously reported (Lobie et al., 1996; Ram and Waxman, 1997; Ragimbeau et al., 2001). Recently, it was reported to be predominantly localized at the membrane (Behrmann et al., 2004). To obtain a clue for the possible localization of the Jak1–Isl1–Stat3 complex, we analyzed the cellular distribution of these proteins by fractionation. Isl1 usually expressed in low level in most cell lines. We chose PC12 (rat neuronal pheochromocytoma) cells, which express detectable level of Isl1 and relatively high amounts of Stat3 and Jak1. The cells were either left untreated or treated with IL-6, and the cytoplasmic, nuclear, and membrane fractions were separated and analyzed by Western blot. The results in Figure 8A showed that the majority of Isl1 was localized in the nuclear portion with a low level detected in the cytoplasmic fraction. Jak1 is primarily localized in the membrane portion with detectable levels in the nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts. Treatment with IL-6 did not cause obvious change in their cellular localization. In contrast, Stat3 was distributed in both cytoplasm and the nucleus in the untreated cells, and treatment with IL-6 resulted in a decrease in the cytoplasm and a concomitant increase in the nucleus. Low amounts of Stat3 also were detected in the membrane portion. To verify the efficiency of the separation, we tested the expression of various proteins in different fractions. The nuclear protein PARP (D'Amours et al., 1999) was detected in the nucleus as well as in the membrane at a low level, whereas the membrane protein calnexin (Behrmann et al., 2004) was found only in the membrane extract. Stathmin, a cytoplasmic protein, was only present in the cytoplasm (Sobel et al., 1989). These results indicate that almost no contamination between the cytoplasmic and the nuclear fractions. However, the membrane portion may contain small amounts of nuclei. In contrast, the nuclear portion was not contaminated by the membrane portion. These analyses suggest that the complex of Jak1–Stat3–Isl1 is most likely localized in the nucleus, and perhaps a small portion in the cytoplasm, but unlikely at the membranes (see Discussion).

Figure 8.

Cellular fractionation of PC12 cells and the colocalization of activated Stat3 and Isl1 in lesioned motor neurons. (A) PC12 cells were left untreated (–) or stimulated with IL-6 for 15 min before fractionation. Fifteen micrograms of cytoplasmic (c), nuclear (n) or membrane-enriched (m) lysates was subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) Mice were subjected to sciatic nerve transaction on the left side, and the right side was untreated serving as a control. The spinal cord was removed and processed for immunohistochemistry as described in Materials and Methods. Tissue sections were double stained with antiphospho-Tyr-Stat3 (pStat3) or anti-Isl1 antibody to measure the expression of Isl1 and the phosphorylation of Stat3. The proteins were visualized with a laser scanning confocal microscope. Isl1 can be detected in the nucleus of the motor neuron cells of the spinal cord in the control (a) and lesioned side (d). After unilateral sciatic nerve transection, pStat3 labeling of ventral horn motor neurons was undetectable on the side contralateral to the lesion (b). However, at 24 h postlesion, an increase in pStat3 labeling in the nucleus of the motor neuron was consistently detected ipsilateral to the lesion (e), which colocalized with Isl1 shown by merged images on the right (f).

Colocalization of Activated Stat3 and Isl1 in the Nucleus of Motor Neurons

It is known that Isl1 is expressed predominantly in the motor neuron in rat (Ahlgren et al., 1997). IL-6–type cytokines CNTF and LIF play important roles for motor neuron survival after nerve lesion in young adult mice. Stat3 is Tyr-phosphorylated and necessary for motor neuron survival and regeneration in these mice (Schweizer et al., 2002). We wondered whether we could detect a colocalization of Isl1 and the Tyr-phosphorylated Stat3 in the lesioned motor neurons in mice. For this purpose, 3-d-old postnatal mice were subjected to left sciatic nerve transection, and the spinal cord was subsequently removed and processed for immunohistochemistry. The expression of Isl1 and the phosphorylation of Stat3 were then measured by immunofluorescence. Isl1 can be detected in the nucleus of the motor neuron cells in the spinal cord, for both lesioned and untreated nerves. In contrast, activated Stat3 could not be detected in the motor neuron of the control side, but it is evident in the lesioned side by using an anti-phospho-Y705 Stat3 antibody. Furthermore, the intensity of the phosphorylated Stat3 correlated to that of Isl1 and displayed a colocalization with Isl1 in the nucleus (Figure 8B). These results support a possible physiological interaction between Stat3 and Isl1 in the nucleus of motor neurons.

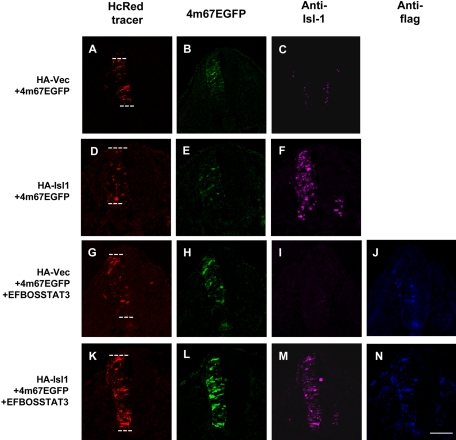

Activation of Stat3 Reporter Gene by Isl1 in the Neural Tube of Chick Embryos

To further confirm the effect of Isl1 on Stat3 activation in vivo, we examine this in the neural tube of chick embryos by using a reporter plasmid 4m67EGFP containing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) driven by a thymidine kinase promoter and four copies of hSIE. This construct was introduced into chick embryos by in ovo electroporation (Timmer et al., 2001). We could detect a weak EGFP expression when this reporter was electroporated with HA-Isl1, which was similar to the control plasmid HA-vector, in the absence of Stat3 (Figure 9, B and E). However, the EGFP expression was increased when a Stat3 expression plasmid EFBOSStat3 was coelectroporated (Figure 9H). The reporter gene expression was further enhanced when EFBOSStat3 and HA-Isl1 were coelectroporated (Figure 9L). Together, these data suggest that Isl1 has a capacity to activate exogenous Stat3 in the neural tube of chick embryo to bind to its specific cis-element and to initiate reporter gene expression.

Figure 9.

Activation of reporter gene by coexpression of Stat3 and Isl1 in neural tube of chick embryos. The FLAG-tagged mouse Stat3 cDNA was placed behind the EF-1α promoter to generate the Stat3 expression construct EFBOSStat3. HA-vector, HA-Isl1, and/or EFBOSStat3 were coelectroporated with the reporter gene construct 4m67EGFP, and tracer plasmid pHcRed1-N1 (as labeled) into the neural tube of stage 12 chick embryos. Tracer, EGFP, Isl1 (anti-Isl1), and Stat3 (anti-FLAG) expressions were detected 24 h later. The numbers of HcRed, EGFP, and Islet-1 expression embryos are 17, 11, and 11 for HA-vector + 4m67EGFP (A–C) and 17, 16, and 15 for HA-Islet-1 + 4m67EGFP (D–F). The numbers of HcRed, EGFP, Islet-1, and FLAG expression embryos are 11, 7, 7, and 7 for HA-vector + 4m67EGFP + EFBOSSTAT3 (G–J) and 14, 10, 10, and 10 for HA-Islet-1 + 4m67EGFP + EFBOSSTAT3 (K–N). The white dashed lines in A, D, G, and K indicate the contour of the electroporated neural tubes. Note that EGFP expression was only localized in a few cells of neural tubes in which HA-vector (B) or HA-Isl1 (E) was coelectroporated with 4m67EGFP. EGFP expression was increased by the coexpression of exogenous Stat3 (EFBOS-Stat3) and 4m67EGFP (H) and further enhanced in the presence of HA-Isl1 (L). The transfected Isl1 protein could be detected readily in the left side of neural tubes electroporated with HA-Isl1 plasmid (F and M), whereas the endogenous Isl1 protein expression also could be detected weakly in the ventral portion of the neural tubes (C, F, I, and M). Bar, 100 μm.

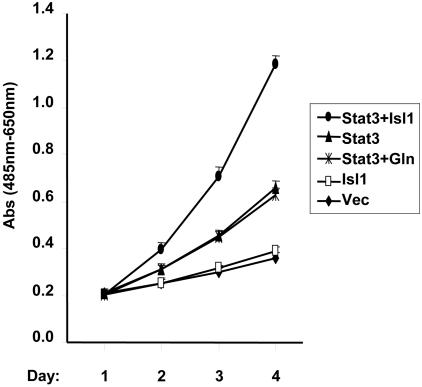

Isl1 Elevates Stat3-regulated Cell Proliferation in the Motor Neuron-like Cells

Last, we examined whether activation of Stat3 by Isl1 has any physiological effect on cell proliferation in motor neurons. NSC-34, an immortalized mouse motor neuron-like cell line, was transfected with the full-length or a mutant Isl1 and Stat3, and the growth rate of these cells was monitored. We found that the expression of Isl1 alone had little effect on the cell growth, whereas Stat3 promoted cell growth to 1.8-fold increase. The growth rate was further enhanced to 3.2-fold by coexpression of Isl1 and Stat3. In contrast, coexpression of Stat3 and the Isl1 mutant GLN, which lacks the Stat3 binding domain, did not enhance the Stat-stimulated cell growth (Figure 10). These results indicate that Stat3 promotes motor neuron-like cell proliferation, and Isl1 further potentiates this effect.

Figure 10.

Isl1, but not the Isl1 mutant deficient in Stat3 binding, elevates Stat3-regulated cell proliferation in NSC-34 cells. NSC-34 cells were transfected with vector (Vec), HA-Isl1, FLAG-Stat3, HA-Isl1 and FLAG-Stat3, or the GLN mutant of Isl1 and Stat3 (see Figure 5D) together. Cells were seeded (5 × 104 cells in 150 μl) and transfected in 96-wells and assayed at 2, 3, or 4 d after transfection. The cell proliferation assay was performed using the cell proliferation kit II (XTT; Roche Diagnostics). Spectrophotometric absorbance was measured at 485-nm wavelength with a reference wavelength at 650 nm. The data shown are one of three independent results. Single points represent means of twelve replicas, with the SD given as the error bars.

DISCUSSION

A Novel Role of Isl1 as an Adaptor Protein for Jak/Stat

Isl1 belongs to LIM-HD family of transcription factors. Its known role as a transcription factor is fulfilled via direct binding to its recognition sites in the promoter region of the target genes either alone or in combination with other transcriptional factors that are usually other members of the LIM-HD family. However, Isl1 and some other LIM-HD proteins are not very effective in DNA binding and transcriptional regulation, and require cofactors. The best characterized high-affinity binding partner for Isl1 is the widely expressed nuclear LIM interactor NLI, also named Ldb1 and CLIM2, which binds to the LIM domains and acts as a bridging factor to build up complexes of different LIM domain-containing proteins (Agulnick et al., 1996; Jurata et al., 1996; Bach, 2000). In addition to NLI, Isl1 also was reported to interact with the estrogen receptor (ER) in the rat hypothalamus. The interaction takes place between the LIM domains of Isl1 and the ligand binding domain of ER. As a consequence, Isl1 prevents dimerization of ER that leads to a specific inhibition of its DNA binding and transcriptional activation (Gay et al., 2000). In our study, we identified that Isl1 interacts with Jaks and Stat3, thereby revealing a new role of Isl1 as a possible adaptor or a scaffold protein between these two important molecules in the cytokine signaling. To support this hypothesis, we found that the individual domains or the combination of several domains of Isl1, including Lim1, Lim2, Lim1 plus Lim2, Hox, GLN, and Hox plus GLN, are not sufficient for induction of Stat3 Tyr-phosphorylation, indicating that the entire molecule of Isl1 is required for its role as an adaptor (Hao and Cao, unpublished data). To further characterize the interactions between Isl1 and Jak1/Stat3, we determined the binding domains. We found that both the LIM domains and the homeodomain of Isl1 are involved in the interaction with Stat3 (Figure 5E), and the same domains also are interacting with Jak1 (Hao, unpublished data). An adaptor protein usually links two proteins via its different domains. Our data imply that the Isl1 may not function as an adaptor protein in a “traditional” manner. In addition, we find that in the presence of Isl1, the association of Stat3 and Jak1 is enhanced, and the Tyr-phosphorylations of both Jak1 and Stat3 also are increased, suggesting that Isl1 is not only essential for the complex formation but also stimulates/potentiates the Jak1 phosphorylation and kinase activity that leads to phosphorylation and activation of Stat3. However, currently, little is known about the molecular and structural basis for these findings. Isl1 could exert such effect either via directly activating the Jak1 autophosphorylation and/or preventing its dephosphorylation, or by stabilizing the complex. On the other hand, our results show that Isl1 binds to the DNA binding domain of Stat3 (Figure 5, B and C). However, the supershift assay indicates that Isl1 is not present in the Stat3–DNA complex (Figure 2D). Hence, the interaction of Isl1 with Stat3 and Jaks could be transiently occurring before Stat3 binding to DNA, and Isl1 does not seem to directly affect DNA binding activity of Stat3.

Cellular Localization of the Jak1–Isl1–Stat3 Complex

Isl1 is a nuclear transcription factor. It is well accepted that Stat proteins are mainly localized in the cytoplasm in the unstimulated cells and translocated into the nucleus after ligand stimulation. However, significant amounts of nuclear Stat3 also have been found in various cell types under unstimulated conditions (Chatterjee-Kishore et al., 2000; Meyer et al., 2002). Therefore, the interaction of Isl1 and Stat3 is likely to be in the nucleus. Indeed, we could see the colocalization of the Tyr-phosphorylated Stat3 and Isl1 in the lesioned murine motor neurons (Figure 7B). On the other hand, Jak family members (Tyk2, Jak1, and Jak2) are generally regarded as membrane-bound or predominantly cytoplasmic proteins. However, subsequently, they also were reported to be constitutively localized in the nucleus (Lobie et al., 1996; Ram and Waxman, 1997; Ragimbeau et al., 2001). Recently, Behrmann et al. (2004) examined the cellular localization of Jak1 in various cell types and concluded that the Jak1, as well as Jak2 and Tyk2, are predominantly localized at the membranes, with no significant amounts in the nucleus or in the cytoplasm. In agreement with their results, we also detected the majority of the endogenous Jak1 in the membrane portion in PC12 cells (Figure 8A) and in the COS-1 cells (Novotny-Diermayr and Cao, unpublished data). Because we did not detect any membrane associated Isl1 in PC12 cells, it is unlikely that the interaction of Isl1 and Jak1 occurs at the membrane. On the other hand, we did observe certain amounts of Jak1 in the nuclear and cytoplasmic portion in both cell lines. We suspect that although the majority of Jak1 is distributed at the membrane, small amounts of Jak1 in the cytoplasm and nucleus cannot be completely ruled out in all cell types. In correlation with these results, we showed that Isl1 has the ability to trigger Stat3 Tyr-phosphorylation independently of ligand stimulation. This effect is approximately equal and additive to that induced by EGF (Figure 2A). Therefore, the Stat3 activation by Isl1 may be mediated by mechanism that is different from receptor-Jak pathway at the membrane. In this way, Isl1 can regulate Stat3 activity either alone or together with the growth factors and cytokines. Consistent with this, we detected only a subset of Jak1 and Stat3 interacting with Isl1 when the three proteins are coexpressed as shown in Figure 7, A and B.

Possible Physiological Significance of the Interaction

Although the interaction and activation of Isl1 to Jak1 and Stat3 were demonstrated in this work mostly based on the overexpressing of Isl1, it is possible that Isl1 has a similar effect under the physiological conditions. Both Stat3 and Isl1 play essential roles in early mouse embryonic development. Deletion of Stat3 by gene targeting leads to embryonic lethality around embryonic day 6.5 and 7.5 before gastrulation via an unknown mechanism (Takeda et al., 1997), whereas elimination of Isl1 in mouse causes growth retardation at E9.5 and embryonic death around E10.5–E11.5, possibly due to impairment in vascular development (Pfaff et al., 1996; Cai et al., 2003). Because Isl1 is the first molecular marker for the motor neuron differentiation, the role of Isl1 in the motor neuron development was initially analyzed and reported in the Isl1-deficient mice. Motor neurons are not generated in these mice, confirming its essential role in the motor neuron differentiation (Pfaff et al., 1996). However, despite a strong expression of Stat3 in the region of neural tube where motor neurons are generated in the mouse embryo at E10.5 (Yan et al., 2004), Cre-mediated conditional knockout of Stat3 in motor neurons did not show significant difference in motor neuron numbers in the spinal cord, suggesting that Stat3 may not be essential for the motor neuron survival during the naturally occurring motor neuron death in embryonic development (Schweizer et al., 2002). However, a role of Stat3 in the motor neuron differentiation cannot be completely ruled out because the Cre is controlled by the neurofilament light chain promoter that commences expression at around E12, which is later than Isl1 expression in the ventral neural tube and the motor neuron differentiation at E9.5. On the other hand, IL-6–type cytokines, including CNTF, IL-6, and LIF, have been demonstrated to be involved in the cellular response to nerve injury (Schwaiger et al., 2000). A transient increase of mRNA for Jak2, Jak3, and Stat3 has been detected, and Stat3 Tyr-phosphorylation also was induced after lesion and sustained until the neuron regeneration has completed (Schwaiger et al., 2000). Indeed, an essential role of Stat3 in motor neuron survival after nerve injury was determined in adult mice (Schweizer et al., 2002). After facial nerve transaction in the Stat3 knockout mice, a dramatic loss of motor neurons was observed. In agreement with these reports, we observed an increased Tyr-phosphorylated Stat3 in motor neurons isolated from mice after sciatic lesion. Such Tyr-phosphorylated Stat3 is colocalized with Isl1, and their intensity seems to be proportional to the level of Isl1 protein. In contrast, no Tyr-phosphorylated Stat3 can be found in control motor neurons (Figure 8B). Therefore, it is possible that the increased Tyr-phosphorylation of Stat3 is mediated by Isl1 that functions as an adaptor protein between Jak and Stat3, either independently or synergistically with the IL-6 type cytokines that are produced after nerve injury.

In our experiments, we showed that Isl1 specifically interacts with Stat3 but does not interact with Stat1 and Stat5. This is consistent with their distinct functions in murine embryonic development. In contrast to the embryonic lethality caused by Stat3 and Isl1 deficiency, genetic ablation of Stat1 or Stat5 does not cause embryonic death, and the deficient mice show no evident developmental abnormalities (Durbin et al., 1996; Meraz et al., 1996; Liu et al., 1997). These results support our assumption that specific modulation of Stat3 activity by Isl1 is important for embryonic development. Therefore, our data for the first time reveal a possible link between Jak-Stat proteins and the LIM-HD transcription factors and their plausible cooperativeness in the regulation of embryonic development, and perhaps also in the other biological processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. R. Cashman, Z. L. Wen, and A. G. Porter for NSC-34, UA4, and SH-SY5Y cell lines; J. Ihle, P. C. Heinrich, J. Bromberg, and Y. Shi for plasmids; and T. M. Jessell for the Isl1 antibodies. We also thank Y. Q. Feng for technical assistance, and D.C.H. Ng for reading the manuscript. This work was supported by the Agency for Science, Technology and Research of Singapore. The in ovo electroporation experiments were supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (39930090, 90208011, 30300174, and 30470856) and National Key Basic Research and Development Program of China (G1999054000 and 2002CB713802) to N. J. X. C. is an adjunct staff in the Department of Biochemistry, National University of Singapore.

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0664) on January 19, 2005.

References

- Agulnick, A. D., Taira, M., Breen, J. J., Tanaka, T., Dawid, I. B., and Westphal, H. (1996). Interactions of the LIM-domain-binding factor Ldb1 with LIM homeodomain proteins. Nature 384, 270–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlgren, U., Pfaff, S. L., Jessell, T. M., Edlund, T., and Edlund, H. (1997). Independent requirement for ISL1 in formation of pancreatic mesenchyme and islet cells. Nature 385, 257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira, S., Nishio, Y., Inoue, M., Wang, X. J., Wei, S., Matsusaka, T., Yoshida, K., Sudo, T., Naruto, M., and Kishimoto, T. (1994). Molecular cloning of APRF, a novel IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 p91-related transcription factor involved in the gp130-mediated signaling pathway. Cell 77, 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrmann, I., Smyczek, T., Heinrich, P. C., Schmitz-Van de Leur, H., Komyod, W., Giese, B., Müller-Newen, G., Hann, S., and Haan, C. (2004). Janus kinase (Jak) subcellular localization revisited: the exclusive membrane-localisation of endogenenous Janus kinase 1 by cytokine receptor interaction uncovers the Jak/receptor complex to be equivalent to receptor tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35486–35493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach, I. (2000). The LIM domain: regulation by association. Mech. Dev. 91, 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, S., Groner, B., and Muller, C. W. (1998). Three-dimensional structure of the Stat3beta homodimer bound to DNA. Nature 394, 145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonni, A., Sun, Y., Nadal-Vicens, M., Bhatt, A., Frank, D. A., Rozovsky, I., Stahl, N., Yancopoulos, G. D., and Greenberg, M. E. (1997). Regulation of gliogenesis in the central nervous system by the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Science 278, 477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, C. L., Liang, X., Shi, Y., Chu, P. H., Pfaff, S. L., Chen, J., and Evans, S. (2003). Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev. Cell 5, 877–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman, N. R., Durham, H. D., Blusztajn, J. K., Oda, K., Tabira, T., Shaw, I. T., Dahrouge, S., and Antel, J. P. (1992). Neuroblastoma x spinal cord (NSC) hybrid cell lines resemble developing motor neurons. Dev. Dyn. 194, 209–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee-Kishore, M., Wright, K. L., Ting, J. P., and Stark, G. R. (2000). How Stat1 mediates constitutive gene expression: a complex of unphosphorylated Stat1 and IRF1 supports transcription of the LMP2 gene. EMBO J. 19, 4111–4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtiss, J., and Heilig, J. S. (1998). DeLIMiting development. Bioessays 20, 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell, J. E., Kerr, I. M., and Stark, G. R. (1994). Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science 264, 1415–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawid, I. B., Toyama, R., and Taira, M. (1995). LIM domain proteins. C. R. Acad. Sci. III 318, 295–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amours, D., Desnoyers, S., D'Silva, I., and Poirier, G. G. (1999). Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem. J. 342, 249–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin, J. E., Hackenmiller, R., Simon, M. C., and Levy, D. E. (1996). Targeted disruption of the mouse Stat1 gene results in compromised innate immunity to viral disease. Cell 84, 443–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durfee, T., Becherer, K., Chen, P. L., Yeh, S. H., Yang, Y., Kilburn, A. E., Lee, W. H., and Elledge, S. J. (1993). The retinoblastoma protein associates with the protein phosphatase type 1 catalytic subunit. Genes Dev. 7, 555–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson, J., Thor, S., Edlund, T., Jessell, T. M., and Yamada, T. (1992). Early stages of motor neuron differentiation revealed by expression of homeobox gene Islet-1. Science 256, 1555–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay, F., Anglade, I., Gong, Z., and Salbert, G. (2000). The LIM/homeodomain protein islet-1 modulates estrogen receptor functions. Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 1627–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, J. A. (1991). Use of vanadate as protein-phosphotyrosine phosphatase inhibitor. Methods Enzymol. 201, 477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guschin, D., Rogers, N., Briscoe, J., Witthuhn, B., Watling, D., Horn, F., Pellegrini, S., Yasukawa, K., Heinrich, P. C., and Stark, G. R. (1995). A major role for the protein tyrosine kinase JAK1 in the JAK/STAT signal transduction pathway in response to interleukin-6. EMBO J. 14, 1421–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger, V., and Hamilton, H. L. (1951). A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J. Morphol. 88, 49–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, P. C., Behrmann, I., Haan, S., Hermanns, H. M., Muller-Newen, G., and Schaper, F. (2003). Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochem. J. 374, 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, P. C., Behrmann, I., Muller-Newen, G., Schaper, F., and Graeve, L. (1998). Interleukin-6-type cytokine signalling through the gp130/Jak/STAT pathway. Biochem. J. 334, 297–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T., Ishihara, K., and Hibi, M. (2000). Roles of STAT3 in mediating the cell growth, differentiation and survival signals relayed through the IL-6 family of cytokine receptors. Oncogene 19, 2548–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert, O., and Westphal, H. (2000). Functions of LIM-homeobox genes. Trends Genet. 16, 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain, N., Zhang, T., Fong, S. L., Lim, C. P., and Cao, X. (1998). Repression of Stat3 activity by activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). Oncogene 17, 3157–3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurata, L. W., Kenny, D. A., and Gill, G. N. (1996). Nuclear LIM interactor, a rhombotin and LIM homeodomain interacting protein, is expressed early in neuronal development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 11693–11698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura, D., Ishihara, K., and Hirano, T. (2003). IL-6 signal transduction and its physiological roles: the signal orchestration model. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 149, 1–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, O., Thor, S., Norberg, T., Ohlsson, H., and Edlund, T. (1990). Insulin gene enhancer binding protein Isl-1 is a member of a novel class of proteins containing both a homeo- and a Cys-His domain. Nature 344, 879–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C. P., and Cao, X. (2001). Regulation of Stat3 activation by MEK kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 21004–21011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X., Robinson, G. W., Wagner, K. U., Garrett, L., Whynshaw-Boris, A., and Henninghausen, L. (1997). Stat5a is mandatory for adult mammary gland development and lactogenesis. Genes Dev. 11, 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobie, P. E., Ronsin, B., Silvennoinen, O., Haldosen, L. A., Norstedt, G., and Morel, G. (1996). Constitutive nuclear localization of Janus kinases 1 and 2. Endocrinology 137, 4037–4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lufei, C., Ma, J., Huang, G., Zhang, T., Novotny-Diermayr, V., Ong, C. T., and Cao, X. (2003). GRIM-19, a death-regulatory gene product, suppresses Stat3 activity via functional interaction. EMBO J. 22, 1325–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lütticken, C., et al. (1994). Association of transcription factor APRF and protein kinase Jak1 with the interleukin-6 signal transducer gp130. Science 263, 92–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J., Zhang, T., Novotny-Diermayr, V., Tan, A. L., and Cao, X. (2003). A novel sequence in the coiled-coil domain of Stat3 essential for its nuclear translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 29252–29260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKendry, R., John, J., Flavell, D., Muller, M., Kerr, I. M., and Stark, G. R. (1991). High-frequency mutagenesis of human cells and characterization of a mutant unresponsive to both alpha and gamma interferons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 11455–11459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meraz, M. A., et al. (1996). Targeted disruption of the Stat1 gene in mice reveals unexpected physiologic specificity in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Cell 84, 431–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, T., Gavenis, K., and Vinkemeier, U. (2002). Cell type-specific and tyrosine phosphorylation-independent nuclear presence of STAT1 and STAT3. Exp. Cell Res. 272, 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon, C., Yoo, J. Y., Matarazzo, V., Sung, Y. K., Kim, E. J., and Ronnett, G. V. (2002). Leukemia inhibitory factor inhibits neuronal terminal differentiation through STAT3 activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 9015–9020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima, K., and Taga, T. (2002). Mechanisms underlying cytokine-mediated cell-fate regulation in the nervous system. Mol. Neurobiol. 25, 233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novotny-Diermayr, V., Zhang, T., Gu, L., and Cao, X. (2002). Protein kinase C delta associates with the interleukin-6 receptor subunit glycoprotein (gp) 130 via Stat3 and enhances Stat3-gp130 interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49134–49142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff, S. L., Mendelsohn, M., Stewart, C. L., Edlund, T., and Jessell, T. M. (1996). Requirement for LIM homeobox gene Isl1 in motor neuron generation reveals a motor neuron-dependent step in interneuron differentiation. Cell 84, 309–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragimbeau, J., Dondi, E., Vasserot, A., Romero, P., Uze, G., and Pellegrini, S. (2001). The receptor interaction region of Tyk2 contains a motif required for its nuclear localization. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30812–30818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram, P. A., and Waxman, D. J. (1997). Interaction of growth hormone-activated STATs with SH2-containing phosphotyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 and nuclear JAK2 tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 17694–17702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saharinen, P., Vihinen, M., and Silvennoinen, O. (2003). Autoinhibition of Jak2 tyrosine kinase is dependent on specific regions in its pseudokinase domain. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 1448–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann, G., Huell, M., Machein, M., Hocke, G., and Fiebich, B. L. (1999). Interleukin-6 activates signal transducer and activator of transcription and mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways and induces de novo synthesis in human neuronal cells. J. Neurochem. 73, 2009–2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaiger, F. W., et al. (2000). Peripheral but not central axotomy induces changes in Janus kinases (JAK) and signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT). Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 1165–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer, U., Gunnersen, J., Karch, C., Wiese, S., Holtmann, B., Takeda, K., Akira, S., and Sendtner, M. (2002). Conditional gene ablation of Stat3 reveals differential signaling requirements for survival of motoneurons during development and after nerve injury in the adult. J. Cell Biol. 156, 287–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, H. Z., and Westphal, H. (1999). Early steps in pituitary organogenesis. Trends Genet. 15, 236–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaki, R., and Pfaff, S. L. (2002). Transcriptional codes and the control of neuronal identity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 25, 251–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, A., Boutterin, M. C., Beretta, L., Chneiweiss, H., Doye, V., Peyro-Saint-Paul, H. (1989). Intracellular substrates for extracellular signaling: characterization of a ubiquitous, neuron-enriched phosphoprotein (stathmin). J. Biol. Chem. 264, 3765–3772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, N., Boulton, T. G., Farruggella, T., Ip, N. Y., Davis, S., Witthuhn, B. A., Quelle, F. W., Silvennoinen, O., Barbieri, G., and Pellegrini, S. (1994). Association and activation of Jak-Tyk kinases by CNTF-LIF-OSM-IL-6 beta receptor components. Science 263, 92–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui, G. C., Soohoo, C., Affar, E. B., Shi, Y. J., Forrester, W., and Shi, Y. (2002). A DNA vector-based RNAi technology to suppress gene expression in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 5515–5520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, K., Noguchi, K., Shi, W., Tanaka, T., Matsumoto, M., Yoshida, N., Kishimoto, T., and Akira, S. (1997). Targeted disruption of the mouse Stat3 gene leads to early embryonic lethality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 3801–3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa, T., Nakashima, K., Namihira, M., Ochiai, W., Uemura, A., Yanagisawa, M., Fujita, N., Nakao, M., and Taga, T. (2001). DNA methylation is a critical cell-intrinsic determinant of astrocyte differentiation in the fetal brain. Dev. Cell 1, 749–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thor, S., and Thomas, J. B. (1997). The Drosophila islet gene governs axon pathfinding and neurotransmitter identity. Neuron 18, 397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmer, J., Johnson, J., and Niswander, L. (2001). The use of in ovo electroporation for the rapid analysis of neural-specific murine enhancers. Genesis 29, 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y., Bian, W., Xie, Z., Cao, X., Le Roux, I., Guillemot, F., and Jing, N. (2004). Stat3 signaling is present and active during development of the central nervous system and eye of vertebrates. Dev. Dyn. 231, 248–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T., Kee, W. H., Seow, K. T., Fung, W., and Cao, X. (2000). The coiled-coil domain of Stat3 is essential for its SH2 domain-mediated receptor binding and subsequent activation induced by EGF and interleukin-6. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 7132–7139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]