Abstract

Rab GTPases have been implicated in the regulation of specific microtubule- and actin-based motor proteins. We devised an in vitro motility assay reconstituting the movement of melanosomes on actin bundles in the presence of ATP to investigate the role of Rab proteins in the actin-dependent movement of melanosomes. Using this assay, we confirmed that Rab27 is required for the actin-dependent movement of melanosomes, and we showed that a second Rab protein, Rab8, also regulates this movement. Rab8 was partially associated with mature melanosomes. Expression of Rab8Q67L perturbed the cellular distribution and increased the frequency of microtubule-independent movement of melanosomes in vivo. Furthermore, anti-Rab8 antibodies decreased the number of melanosomes moving in vitro on actin bundles, whereas melanosomes isolated from cells expressing Rab8Q67L exhibited 70% more movements than wild-type melanosomes. Together, our observations suggest that Rab8 is involved in regulating the actin-dependent movement of melanosomes.

INTRODUCTION

Normal cellular function requires proper organelle distribution, which is accomplished through the cooperation between microtubule- and actin-based motors. Recently, Rab GTPases have been implicated in the regulation of specific microtubule- or actin-based motor proteins. Such regulation can occur through the direct binding of Rab proteins to the motors. Rab6, which regulates both intra-Golgi transport and retrograde transport from the Golgi back to the endoplasmic reticulum, interacts with Rabkinesin 6 (Echard et al., 1998); Rab11, which regulates plasma membrane recycling, binds myosin Vb (Hales et al., 2002); and genetic evidence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae suggests that the Rab Sec4p interacts with the type V myosin Myo2p (Schott et al., 1999).

Other Rab proteins mediate the movement of organelles on cytoskeleton tracks by recruiting, in a GTP-dependent manner, a specific class of effectors that bind the motors. The Rab7 effector protein RILP controls lysosomal transport by recruiting dynein–dynactin motors (Jordens et al., 2001). Mutations in Sec2p, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) and thus an activator of the Rab protein Sec4, reduce the binding of the myosin Myo2p to the secretory vesicles (Schott et al., 1999). Studies of mouse coat color mutants and of the human Griscelli syndrome showed that myosin Va is recruited to melanosomes by GTP-bound Rab27 via melanophilin, a Rab27a effector (Wu et al., 1998, 2002; Hume et al., 2001). Another Rab27 effector, MyRIP, might recruit myosin VIIa to retinal melanosomes (El-Amaraoui et al., 2002).

In addition to regulating the reversible membrane association of motors with organelles membranes, Rab proteins might regulate the motor activity, the intracellular organization of the cytoskeletal tracks, or the binding of the organelles to the cytoskeletal tracks. It has been suggested, for example, that activated Rab5, which causes the redistribution of endosomes to the perinuclear region and stimulates the association of endosomes with microtubules in vitro, regulates the binding of endosomes to microtubules (Nielsen et al., 1999).

We investigated the possible role of Rab proteins in the actin-based movement of melanosomes. This movement can be considered as a paradigm for the motility of numerous intracellular organelles in eucaryotic cells. Two Rab proteins that have been detected on melanosomes are linked to myosin V. Rab8 in epithelial cells and its orthologue Sec4 in yeast interact with specific myosin V isoforms, whereas activated Rab27 recruits myosin V to melanosomes and thereby regulates the actin-based movement of melanosomes (Pruyne et al., 1998; Hume et al., 2001; Rodriguez and Cheney, 2002; Wu et al., 2002; Chakraborty et al., 2003). To analyze the contribution of Rab27 and Rab8 to the actin-based movement of melanosomes, we reconstituted the movement of isolated melanosomes on actin bundles in vitro. We observed a large decrease in the frequency of movement for melanosomes displaying little or no Rab27. Inhibition of Rab8 by using specific antibodies also reduced the frequency of movement. In contrast, the expression of a dominant active mutant of Rab8, Rab8Q67L, increased the population of melanosomes exhibiting actin-based movement in vitro. Furthermore, the overexpression of Rab8Q67L increased the population of melanosomes displaying directional movement in vivo in the absence of microtubules. Together, these observations indicate that both Rab27 and Rab8 regulate the actin-based movement of melanosomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and Constructs

We used the following primary antibodies: mouse antibodies to Rab27, early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1), and Rab8 (BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY); to tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO); to tyrosinase (αPep7h; Jimenez et al., 1991); to green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN); rabbit antibodies to myosin V (DIL2; a gift of Dr. J. Hammer, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA); affinity-purified rabbit antibodies to Rab8 (a gift of Dr. A. Zahraoui, Institut Curie, Paris, France); and to Rab6 (a gift of Dr. B. Goud, Institut Curie, Paris, France). We used also recombinant plasmids encoding GFP-Rab27T23N and GFP-Rab27Q78L (Menasche et al., 2003), GFP-Rab8Q67L and GFP-Rab8T22N (Marzesco et al., 2002), GFP-Rab7Q67L (Bucci et al., 2000), and glutathione S-transferase (GST)-T fimbrin (Arpin et al., 1994).

Cell Culture and Transfection

MNT-1 and melan-a melanocytes were grown as described previously by Raposo et al. (2001) and by Hume et al. (2001), respectively. HeLa cells were grown in DMEM (Seromed, Berlin, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Seromed), penicillin (10 U/ml; Seromed), and streptomycin (10 mg/ml; Seromed). The immortal ash/ash mouse melanocyte cell line melan-ash3 was obtained by crossing C57BL6/J mice homozygous for ashen (Rab27aash) (Barral et al., 2002) with C57BL6/J mice carrying an Ink4a-Arf exon 2 deletion (Serrano et al., 1996), at Texas A&M University (College Station, TX). Trunk skins from neonatal mice homozygous for both mutations were used at St. George's Hospital Medical School for preparation of melanocyte cultures, as described previously (Sviderskaya et al., 2002). Melan-ash3 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 U/ml streptomycin, 200 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (Calbiochem), and 200 pM cholera toxin at 37°C with 10% CO2.

Transient and stable transfections with recombinant plasmids encoding the GFP–tagged Rab proteins were performed by electroporation using the Optimix kit (EquiBio, Middleses, United Kingdom). Stably transfected MNT-1 cells were established by incubation in selective medium (0.7 mg/ml G418 [Geneticin]) for 10–15 d and checked for GFP fluorescence. Selected clones were checked for the expression of GFP-constructs by immunoblotting. Stably transfected MNT-1 cells were incubated overnight with 10 mM sodium butyrate before each experiment.

Preparation of Melanosomes

This method was adapted from Rogers et al. (1998). Briefly, confluent MNT-1 cells were scraped in H buffer (50 mM imidazole, pH 7.4, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 5 mM magnesium sulfate, 0.15 mg/ml casein, and 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) and homogenized by passing them two to four times through a cell cracker (HGM, Heidelberg, Germany). The postnuclear supernatant, prepared from the cell homogenate by centrifugation at 600 × g for 5 min, was centrifuged at 2500 × g for 5 min. The recovered pellet (P2500) was layered onto a 50% Percoll cushion, centrifuged at 5000 × g for 20 min, and the loose pellet of melanosomes was collected according to Rogers et al. (1998). Percoll was removed by washing for analysis of the melanosomes on SDS-PAGE.

In Vitro Motility Assay

Actin Polymerization. Actin (12.6 μM) from rabbit muscle, Alexa-568 conjugate (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was polymerized in presence of 5 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM ATP, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM DTT for 3 h at 4°C (Arpin et al., 1994). This actin solution was diluted to 1 μM actin in actin buffer (5 mM KPI, pH 7, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 40 mM KCl, and 1 mM MgCl2) with 2 μM phalloidin. After overnight incubation at 4°C, nonpolymerized actin was removed by centrifugation at 100 000 × g for 5 min, and the actin pellet was gently resuspended in actin buffer (F actin).

Bundling of F Actin. To bundle actin filaments, recombinant human GST-T fimbrin, prepared as described by Arpin et al. (1994), was added to F actin at a ratio ranging from 2:1 to 10:1 M concentration, depending on the concentration of actin filaments obtained at the end of the polymerization. Actin bundles were incubated 4 min in the motility chamber with a coverslip coated with 0.1% nitrocellulose in amyl acetate. Free bundles were removed by perfusion with 10 mM 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS), pH 7, 0.5 M NaCl, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.15 mg/ml casein, and 1 mM DTT.

Motility Assay. Melanosomes were diluted in motility buffer (10 mM MOPS, pH 7, 20 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 5 mM MgCl2) supplemented with 2 mM ATP, an ATP-regenerating system (80 μg/ml creatine kinase, 16 mM creatine phosphate), and an antifade system (10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2.5 mg/ml glucose, 20 μg/ml catalase, and 0.1 mg/ml glucose oxydase). They were then injected into the motility chamber. The typical concentration of melanosomes ranged from 0.4 to 0.5 mg/ml in an injected volume of approximatively 12 μl. In some experiments, 50 μg/ml antibody was incubated with melanosomes for 15 min before injection into the motility chamber. Actin-based movements of melanosomes were monitored using a Leica inverted microscope with Plan Apochromat 100× 1.4 numerical aperture oil immersion lens in the differential interference contrast (DIC) mode to visualize melanosomes and with a fluorescence filter (N21 excitation BP515-560 dichroïe 565, emission LP590) to observe Alexa 568. One image of the actin network was taken before each sequence of melanosome images acquired at 1 frame/s for 2 min.

Analysis of the Movements. Successive DIC frames were superimposed with the fluorescent image of the actin network, and melanosomes were designated as moving melanosomes on actin if they exhibited a directional displacement along an actin filament over five or more frames. The number of movement determined with different types of melanosomes was normalized to the number of movement observed in the same experiment with melanosomes isolated from wild-type MNT-1 cells. Statistical differences for the number of movements were evaluated by Pearson's chi-square test with Yates' continuity correction by using R software (R, Development Core Team, 2004). Moving melanosomes were tracked as a function of time using Meta-Morph software (Universal Imaging, Downingtown, PA), and instantaneous velocities were calculated from the absolute displacement of a melanosome along actin filaments over 1 s (time lapse between two frames).

Binding of Melanosomes to Actin Bundles. To determine the number of melanosome that bound actin filaments in vitro, melanosomes diluted in the motility buffer were injected in the motility chamber as described above and incubated for 15 min before washing with motility buffer containing the ATP-regenerating system and the antifade system. The injection of actin filaments before the melanosomes increased the number of melanosomes observed per field by >90% under these experimental conditions. Melanosomes that codistributed with actin filaments were considered to be actin bound. To compare the actin binding properties of melanosomes isolated from different cell types, the number of actin-bound melanosomes was normalized by the concentration of melanosomes per microliter.

Videomicroscopy of In Vivo Movements of Melanosomes

The movements of melanosomes in living cells were monitored for 120 s (1 frame/s) by DIC microscopy after depolymerization of microtubules with 10 μM nocodazole for 1 h at 37°C, according to Gross et al. (2002). Depolymerization of microtubules was monitored by immunofluorescence by using anti-tubulin antibody. Melanosomes were tracked as a function of time, by using MetaMorph software. The mean square displacement (MSD) was computed as a function of time: <r2(t)>= k.Δtα, where brackets denote averaging from the coordinates of each melanosome (Abney et al., 1999).

Indirect Immunofluorescence

Cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence as described by Raposo et al. (1999) by using Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cappel Laboratories, Durham, NC) and viewed with confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Electronic Microscopy

Immunogold labeling of the melanosomal fraction by using a whole mount procedure was performed as described previously (Raposo et al., 1999). Actin filaments polymerized and organized in bundles as described above were negatively stained with 4% uranyl acetate, pH 4, for 5 min and dried on Whatman paper after 5-min fixation in glutaraldehyde.

RESULTS

Development of an Actin-based Motility Assay

Organelle movement on actin filaments has been well documented in dissociated axoplasm or in vitro, by using extruded algal cytoplasm as a source of polarized actin (Kuznetsov et al., 1992; Kachar et al., 1993; Rogers and Gelfand, 1998; Rogers et al., 1998). The presence of algal or axon cytoplasm in the assay precludes the identification of new factors that might contribute to or regulate organelle motility. To investigate the role of Rab proteins in the regulation of the actin-dependent movement of melanosomes, we developed an actin-based motility assay with isolated melanosomes and actin bundles.

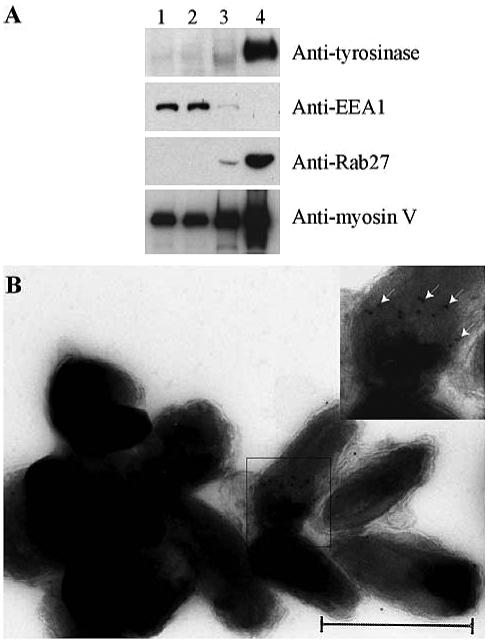

We isolated melanosomes from MNT-1 cells according to the method described by Rogers et al. (1998). The purity of the melanosomal fraction was assessed by biochemical and electron microscopy analyses. The melanosomal fraction was highly enriched in tyrosinase, an enzyme specific to mature melanosomes, whereas EEA1, one of the effectors of Rab5 that is enriched in early endosomes, was hardly detectable (Figure 1A, column 4). Electron microscopy showed that this fraction was composed of dark ovoid vesicles with the characteristic morphology of melanosomes as described by Raposo et al. (2001) (Figure 1B). The membrane integrity of isolated melanosomes was preserved as judged by electron microscopy. Furthermore, isolated melanosomes exhibited motile properties on microtubules (our unpublished data) as well as proteins involved in actin-dependent melanosome movement such as Rab27 and myosin V (Figure 1, A, and B, inset).

Figure 1.

Purification of melanosomes. (A) Western blot analysis of the postnuclear supernatant (lane 1), 2500 × g supernatant (lane 2), 2500 × g pellet (lane 3), and the melanosomal fraction (lane 4) was performed with antibodies against tyrosinase, EEA1, Rab27, and myosin V. (B) Electron micrographs of the melanosomal fraction (inset) immunogold labeling of this fraction with anti-myosin V antibodies (see arrows). Bar, 500 nm.

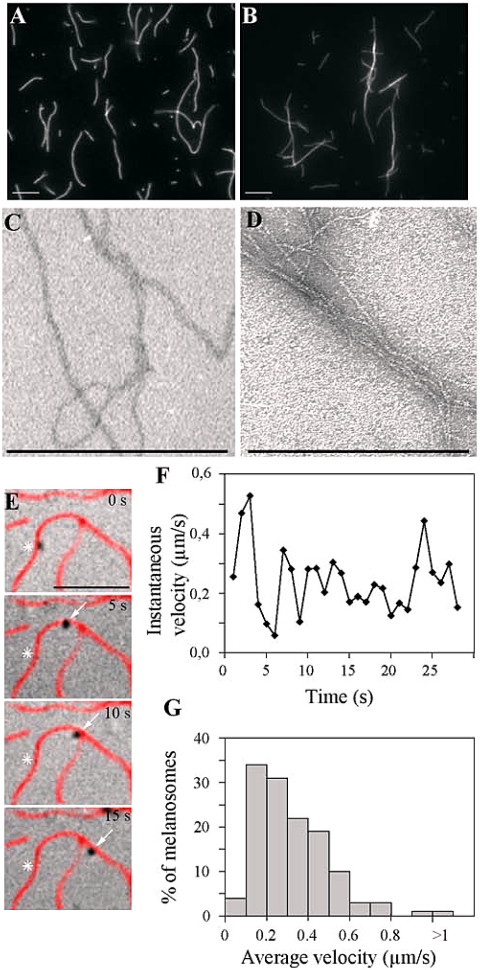

Actin cables in yeast were shown to be required for polarized delivery of secretory vesicles mediated by a myosin V isoform (Pruyne et al., 1998). Thus, we attempted to generate fluorescent parallel actin bundles in vitro. We took advantage of several reports indicating that fimbrin, also named plastin, induces the formation of parallel actin bundles (Bretscher, 1981; Arpin et al., 1994; Volkmann et al., 2001). Addition of recombinant T fimbrin to fluorescent actin filaments induced the reorganization of fluorescent actin filaments, as evidenced by the reduced number of fluorescent actin structures observed under these experimental conditions (Figure 2, A vs. B). It was not possible to determine whether the smaller number of structures observed in presence of T fimbrin was composed of single actin filament or bundles at the resolution of light microscopy, but actin bundles were observed under these experimental conditions by electron microscopy (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Isolated melanosomes move in vitro on actin bundles. (A–D) Organization of actin filaments in the presence of T fimbrin. Fluorescent actin filaments (100 nM) polymerized as described in Materials and Methods were incubated (B and D) or not (A and C) with 1 μM recombinant T fimbrin for 1 h. The filamentous structures formed under these experimental conditions were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (A and B) and electron microscopy (C and D). Bars, 5 μm (A and B) and 500 nm (C and D). (E–G) Analysis of the actin-dependent movements of melanosomes reconstituted in vitro. (E) Sequence of DIC microscopy images of melanosomes overlaid with the corresponding fluorescent image of actin. Stars on each frame mark the starting position of the melanosome; arrows show the successive positions of the melanosome on the actin filament (see also Supplemental Video 1). Bar, 5 μm. (F) Instantaneous velocities during the movement of the melanosome shown in E and plotted as a function of time. (G) Average velocities of 186 moving melanosomes recorded in nine independent experiments binned in 0.1 μm/s increments and plotted as the percentage of moving melanosomes. The last bin represents average velocities faster than 1 μm/s.

The fluorescent bundles were then absorbed to the glass surface of motility chambers coated with nitrocellulose (Hyman and Mitchison, 1993). Movement of isolated melanosomes was reconstituted by injection of the melanosomal fraction in the presence of ATP and recorded using time-lapse videomicroscopy (Figure 2E) (Supplementary Video 1). No addition of soluble factors was required for movement. Addition of T fimbrin at a ratio to actin ranging from 2:1 to 10:1 M concentration (depending on actin filament concentration), increased the frequency of the observed movements 10-fold. Thirty to 50% of the melanosomes observed in the field were detected in the vicinity of actin filaments, and 10–20% of the melanosomes that colocalized with actin filaments moved unidirectionally, in an ATP-dependent manner. Two to three movements per minute and per field were generally observed. Although these movements were discontinuous (Figure 2F), average velocities typically ranged from 0.1 to 0.3 μm/s for 60% of the moving melanosomes (n = 186) (Figure 2G). The velocities measured were slower than those reported for vesicular organelles and endoplasmic reticulum isolated from squid axoplasm, but they were faster than the mean velocity determined previously for the movement of Xenopus melanosomes on Nitella actin bundles (0.04 μm/s) (Rogers and Gelfand, 1998; Tabb et al., 1998). The low velocity observed for Xenopus melanosomes may be due to the presence of cytoplasm. In contrast, the velocities measured in our assay are in good agreement with the value suggested for in vivo melanosomes movement in mammalian cells (0.1–0.175 μm/s) (Wu et al., 1998) and the velocity that we have determined in vivo after depolymerizing microtubules in melan-a cells (0.09 μm/s) (see below).

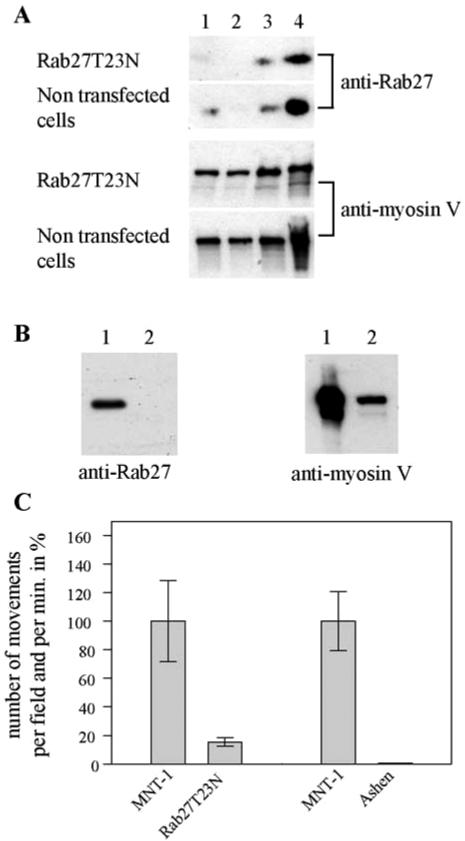

Rab27 Is Required for Actin-dependent Melanosome Movement In Vitro

Rab27a contributes to the localization of melanosomes at the cell periphery (Wilson et al., 2000; Hume et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2001). On activation, Rab27a recruits melanophilin, which in turn recruits myosin Va (Wu et al., 2002). To investigate whether Rab27a contributes to the actin-dependent movement of melanosomes in our in vitro motility assay, we isolated melanosomes from an MNT-1 cell line overexpressing a dominant negative mutant of Rab27a, GFP-Rab27T23N. These melanosomes displayed less endogenous Rab27 and less myosin V than melanosomes isolated from nontransfected cells (Figure 3A, column 4). Rab27a being the product of the ashen gene, we also isolated melanosomes from melan-ash3 cells, an immortal melanocyte cell line derived from the ashen (Rab27a null) mouse (Wilson et al., 2000). Consistent with previously reported data for primary melanocytes and cell lines isolated from ash/ash mice (Wu et al., 2001), we were not able to detect Rab27 in melan-ash3 cells (our unpublished data), or in melanosome-enriched fraction isolated from these cells (Figure 3B, lane 2). Furthermore, the amount of myosin Va detected on melanosomes isolated from melan-ash3 cells was considerably reduced compared with that of wild-type melanosomes (Figure 3B, lane 1 vs. lane 2).

Figure 3.

Rab27 controls actin-dependent movement of melanosomes. (A and B) Detection of Rab27 and myosin V on melanosomes. (A) Endogenous Rab27 and myosin V were detected by Western blot in postnuclear supernatant (lane 1), 2500 × g supernatant (lane 2), 2500 × g pellet (lane 3), and melanosomes (lane 4) isolated from nontransfected MNT-1 cells or from cells stably expressing GFP-Rab27T23N. (B) Endogenous Rab27 and myosin V were detected by Western blot in 25 μg of melanosomes isolated from MNT-1 cells (lane1) and melan-ash3 cells (lane 2). (C) Actin-based movement of melanosomes depends on Rab27. The number of movements per minute and per field for melanosomes from MNT-1 cells overexpressing GFP-Rab27T23N (Rab27T23N) was expressed as a percentage of the number of movements observed under the same experimental conditions with wild-type MNT-1 melanosomes (MNT-1). Four and 30 movements of melanosomes from transfected and wild-type cells, respectively, were observed in the representative experiment shown in C. Melanosomes isolated from melan-ash3 cells (Ashen) also were examined in comparison with MNT-1 melanosomes (MNT-1). Thirty-one movements were observed with wild-type melanosomes in the representative experiment shown in C. No movement was observed with melanosomes from ash/ash cells under our experimental conditions. Error bars are the mean ± SD of the number of movements observed per movies.

In agreement with the large decrease in myosin V, melanosomes isolated from the MNT-1 cell line overexpressing GFP-Rab27T23N exhibited 85% fewer movements than melanosomes isolated from nontransfected cells, whereas no movement was detectable under our experimental conditions with melanosomes isolated from the melan-ash3 cells (Figure 3C). Together, these data indicate that Rab27 is required for actin-dependent melanosome movement in vitro.

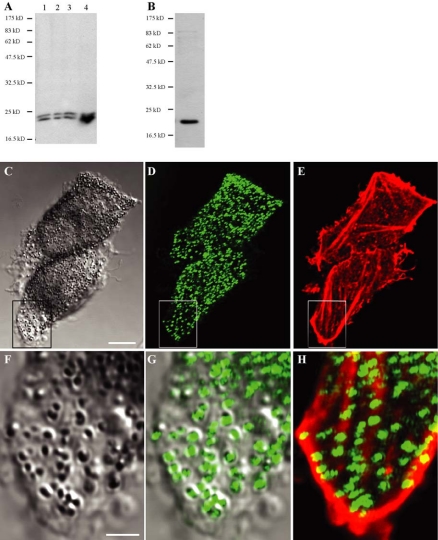

Rab8 Is Associated with Melanosomes

Because Rab8 has been linked to specific isoforms of myosin V and was detected in a subcellular fraction enriched in melanosomes (Pruyne et al., 1998; Rodriguez and Cheney, 2002; Chakraborty et al., 2003), we hypothesized that Rab8 may contribute to the motility of melanosomes. To examine this hypothesis, we first determined whether Rab8 was associated with melanosomes. Using polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies raised against Rab8, we observed that Rab8 was enriched in the melanosomal fraction. Monoclonal anti-Rab8 antibody detected a doublet in the fractions containing vesicular membranes and cytosol and revealed a strong signal in the melanosomal fraction isolated from MNT-1 cells (Figure 4A, lanes 1, 2, and 3 vs. lane 4). The molecular weight of these bands is consistent with the size of Rab8. Furthermore, affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies directed against Rab8 recognized only a single band in the melanosome-enriched fraction, which was also compatible with the size of Rab8 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Rab8 is associated with melanosomes. (A) Total proteins (25 μg) from postnuclear supernatant (lane 1), 2500 × g supernatant (lane 2), 2500 × g pellet (lane 3), and melanosomal fraction (lane 4) were analyzed by Western blot with monoclonal anti-Rab8 antibody. (B) Melanosomal fraction isolated from MNT-1 cells was analyzed by Western blot with affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies directed against Rab8. One protein band, compatible with the size of Rab8, was detected in the melanosomal fraction with the two types of antibodies. (C–H) MNT-1 cells colabeled with affinity-purified polyclonal anti-Rab8 antibodies and fluorescent phalloidin were analyzed by confocal microscopy. C, D, and E show the same confocal section at the base of the cells analyzed in transmission (C) with Rab8 antibodies (D) and phalloidin (E). (F) High magnification of the inset represented in C. (G) Overlay of the insets shown in C and D at higher magnification. (H) Overlay of the insets shown in D and E at higher magnification. Note the codistribution of Rab8 with pigments and the alignment of these pigment granules with actin filaments. Bars, 3.4 μm (C) and 1 μm (F).

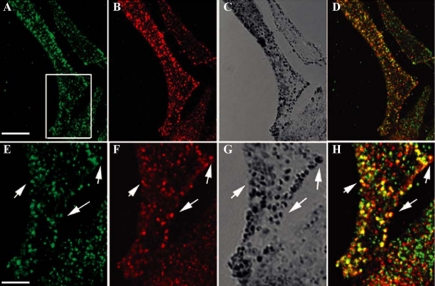

In HeLa cells, Rab8 was detected either at the cell periphery or in the perinuclear region, depending on the cell density (Hattula et al., 2002). Immunofluorescence labeling of Rab8 in MNT-1 cells by using the affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies showed that, in addition to its localization in the perinuclear region (our unpublished data), a significant proportion of this protein colocalized with pigment granules at the cell periphery (Figure 4C vs. D and F vs. G). Alignment of Rab8-labeled pigment granules with actin filaments was often observed in these regions (Figure 4D vs. E and H). This last observation is consistent with previous observations showing that Rab8-positive vesicles codistributed with actin filaments at the periphery of HeLa cells (Hattula et al., 2002). Because Rab27 colocalizes with mature melanosomes, we next compared the cellular distribution of these two Rab proteins in MNT-1 cells. Figure 5, A–D, shows extensive overlap between the distribution of Rab8 and Rab27. Rab8-positive pigments granules at the cell periphery also showed labeling for Rab27 (Figure 5, E–H, arrows).

Figure 5.

Rab8 colocalizes with Rab27 on pigments granules. MNT-1 cells colabeled with affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies directed against Rab8 and monoclonal anti-Rab27 antibodies were analyzed by confocal microscopy. (A–D) Same confocal section through an extended process of MNT-1 cells labeled with anti-Rab8 (A) and anti-Rab27 antibodies (B). (C) Distribution of the pigments granules in this confocal section. (D) Overlay of the images shown in A and B. (E–H) High magnification of the inset represented in A, for the anti-Rab8 (E) and anti-Rab27 labeling (F), the distribution of the pigments granules (G), and the overlay of images shown in E and F (H). Bars, 2 μm (A) and 4.72 μm (E).

Together, these observations indicate that Rab8 is associated with mature melanosomes, and they are consistent with a recent study reporting the presence of Rab8 in a melanosome-enriched subcellular fraction isolated from the B16 cells (Chakraborty et al., 2003). It is unlikely that the association of Rab8 with melanosomes in MNT-1 cells is due to cell transformation because we also detected Rab8 on melanosomes from melan-ash3 cells (our unpublished data).

Rab8 Contributes to the Cellular Distribution of Melanosomes

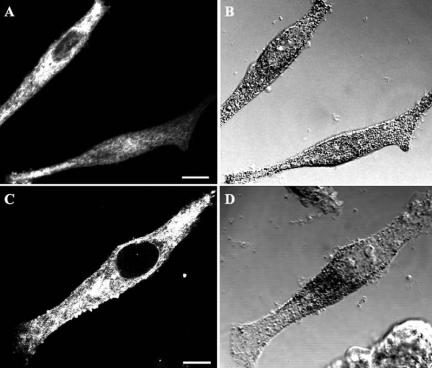

We next determined whether the expression of a dominant active mutant of Rab8, GFP-Rab8Q67L, or a dominant inactive mutant, GFP-Rab8T22N, affected the cellular distribution of mature melanosomes in MNT-1 cells. Pigment granules in cells expressing GFP-Rab8T22N displayed the same cellular distribution as in wild-type cells (Figures 4C and 6B). As previously reported, cells overexpressing GFP-Rab8Q67L frequently displayed fewer actin cables than wild-type cells (our unpublished data) (Peranen et al., 1996). In 75% of cells expressing GFP-Rab8Q67L, pigment granules were concentrated in the perinuclear region in contrast to wild-type cells and cells expressing GFP-Rab8T22N (Figure 6D vs. B and Figure 4C). The observation that clustering of melanosomes in the perinuclear region only occurred in 25% of the cells expressing GFP-Rab8Q67L after nocodazole treatment and in 50% of transfected cells after cytochalasin D treatment suggests that this distribution is dependent on both types of cytoskeleton network.

Figure 6.

Expression of Rab8 mutants perturbs the cellular distribution of melanosomes. MNT-1 cells transiently transfected with GFP-Rab8T22N (A and B) or GFP-Rab8Q67L (C and D) were analyzed for the expression of enhanced GFP-tagged recombinant proteins (A and C) and the distribution of pigment granules by using phase contrast (B and D). Note the perinuclear distribution of the pigment in the cell overexpressing GFP-Rab8Q67L. Bars, 1.6 μm (A) and 2 μm (C).

Rab8 Regulates the Actin-based Movement of Melanosomes In Vivo

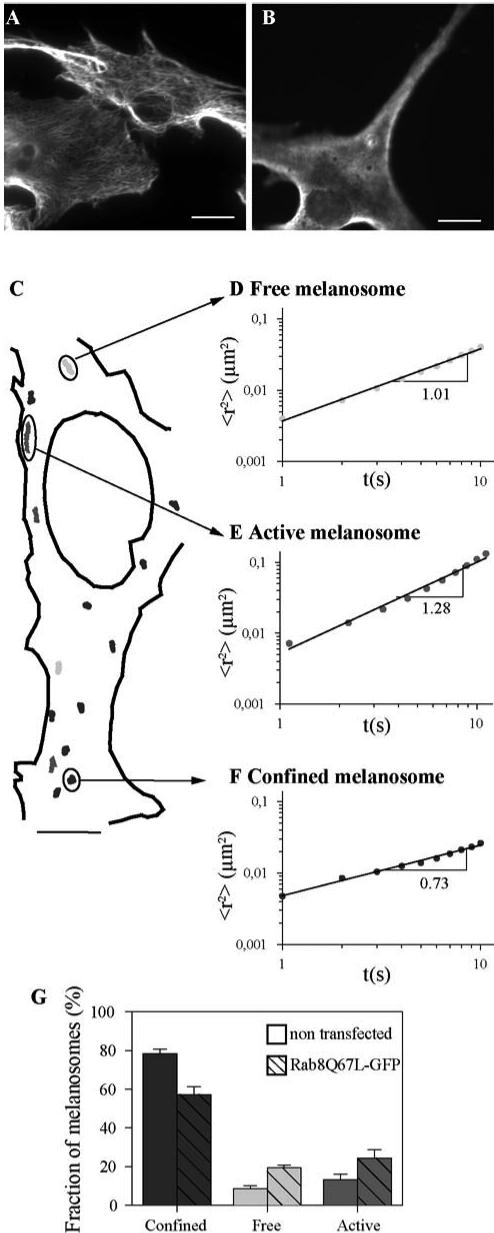

Rab8 may regulate the cellular distribution of melanosomes by controlling the organization of the actin cytoskeletal network. It also may regulate the actin-dependent movements of these organelles. To determine whether Rab8 contributes to the cytoplasmic movements of these organelles, we analyzed residual in vivo movements of melanosomes in cells in which microtubules were depolymerized. Due to their morphology and to the large number of melanosomes present, we could not perform this study with MNT-1 cells and chose melan-a cells as an alternative model. Expression of GFP-Rab8Q67L in these cells also induced the accumulation of melanosomes in the perinuclear region. Microtubules were depolymerized according to Gross et al. (2002). These experimental conditions allowed the depolymerization of all microtubules as shown in Figure 7B. Motions of melanosomes have been tracked after nocodazole treatment (Figure 7C), and the MSD of individual melanosomes was computed from their tracks. MSD fits remarkably well with a power law in which the exponent α reflects the type of movement observed (Amblard et al., 1996; Abney et al., 1999; Caspi et al., 2002). α = 1 characterizes free melanosomes undergoing Brownian motions (Figure 7D). α > 1 characterizes actively transported melanosomes showing directional movements (Figure 7E). α < 1 characterizes confined melanosomes with oscillatory movements (Figure 7F). We classified the melanosomes into three populations according to the value of the exponent. Thirteen percent of melanosomes underwent directional movement in the absence of microtubules and displayed an average exponent of 1.2 (Caspi et al., 2002) (Figure 7G). The mean velocity of this population was 0.09 μm/s. Seventy-eight percent of melanosomes were confined with an average exponent of 0.75. This value was equal to the value calculated for beads embedded or caged in an actin network (Amblard et al., 1996). It therefore might be indicative of melanosomes embedded in a network of actin filaments. The mean velocity and the average exponent of both active and confined melanosomes were the same in cells overexpressing GFP-Rab8Q67L and in nontransfected cells, suggesting that the motion and immobilization of melanosomes is dependent on the same molecular mechanisms under both experimental conditions. However, overexpression of GFP-Rab8Q67L altered the distribution of melanosomes between the three populations defined above. Although the number of confined melanosomes was decreased (57 vs. 78%), striking increases in both Brownian motion (19 vs. 9%) and directional movement (24 vs. 13%) of melanosomes were observed (Figure 7G).

Figure 7.

The active form of Rab8 enhances in vivo melanosome movement. Melan-a cells incubated with (B) or without (A) nocodazole were immunolabeled with anti-tubulin antibody. Bar, 5 μm. (C–G) Analysis of melanosome movements after depolymerization of microtubules. (C) Trajectories observed in nontransfected melan-a cells treated with nocodazole are represented. MSD of melanosomes showing free movement (D) (exponent α = 1), directional movement (E) (active melanosome with exponent α > 1), and confined melanosomes (F) (exponent α < 1) were computed as <r2(t)> = k.Δtα and plotted on a log scale. (G) Proportions of confined (exponent α < 0.95) (dark gray), free (0.95 < α < 1.05) (light gray), and active melanosomes (α > 1.05) (medium gray) were determined from the computed MSD. The average of four independent experiments is plotted as a percentage of the number of melanosomes analyzed per experiment (±SD) in nontransfected and in Rab8Q67L-GFP–expressing cells.

Rab8 Regulates the Actin-dependent Movement of Melanosomes In Vitro

GFP-Rab8Q67L may indirectly facilitate the directional movement of melanosomes by activating an effector involved in the remodeling of actin networks. Alternatively or in addition, Rab8 may control a component of the actomyosin machinery present on melanosomes, which is involved in their movements. To discriminate between these two hypotheses, we analyzed the role of Rab8 by using our in vitro motility assay in which the actin network is immobilized.

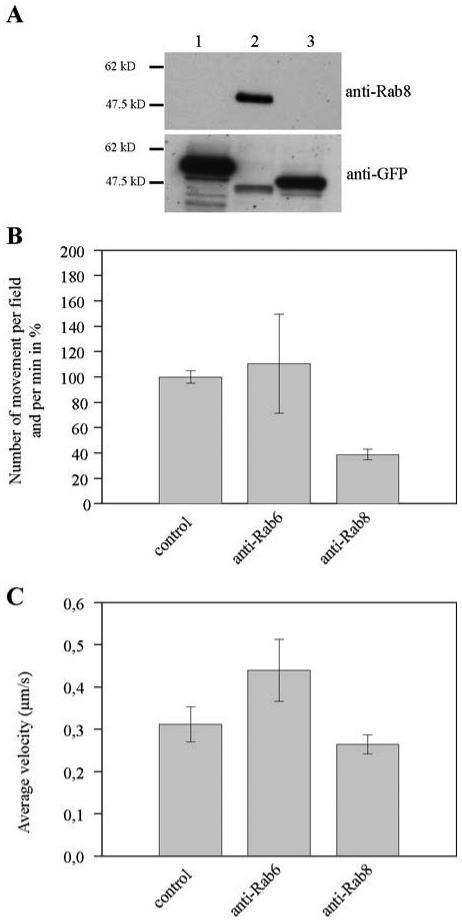

We first inhibited the activity of Rab8 by using the affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies directed against Rab8. These antibodies recognized Rab8 but did not cross-react with other Rab proteins such as Rab7 or Rab27 (Figure 8A). Addition of anti-Rab8 antibodies to the in vitro motility assay did not change the average velocity of the melanosomes, but decreased by 60% the number of movements observed per minute (Figure 8, B and C). In contrast, affinity-purified antibody raised against Rab6, a protein that is not associated with melanosomes, did not affect the frequency of movements (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Anti-Rab8 antibodies decrease the frequency of the actin-based movement of melanosomes in vitro. (A) Lysates from HeLa cells transfected with recombinant plasmids encoding GFP-Rab27Q78L (lane 1), GFP-Rab8Q67L (lane 2), and GFP-Rab7Q67L (lane 3) were analyzed for the expression of recombinant GFP-tagged Rab proteins by Western blot by using affinity-purified polyclonal anti-Rab8 antibodies (anti-Rab8) or anti-GFP antibody (anti-GFP). Note that the affinity-purified antibodies directed against Rab8 recognized exclusively GFP-Rab8Q67L. (B and C) Melanosomes moving in vitro on actin filaments in the absence (control) or in the presence of anti-Rab6 antibodies (anti-Rab6) or affinity-purified polyclonal anti-Rab8 antibodies (anti-Rab8) were tracked. (B) Number of movements per minute and per field for melanosomes treated with anti-Rab6 antibodies or anti-Rab8 antibodies is expressed as a percentage of the number of movements observed under the same experimental conditions with nontreated melanosomes. Errors bars are the mean ± SD of the number of movements observed per movies in three independent experiments. Statistical analysis comparing nontreated melanosomes and melanosomes treated with anti-Rab8 antibodies by using a chi-square test gave p value = 0.009%. (C) Averages of the instantaneous velocities calculated from the collected data under these different experimental conditions are shown (error bars represent ± SD).

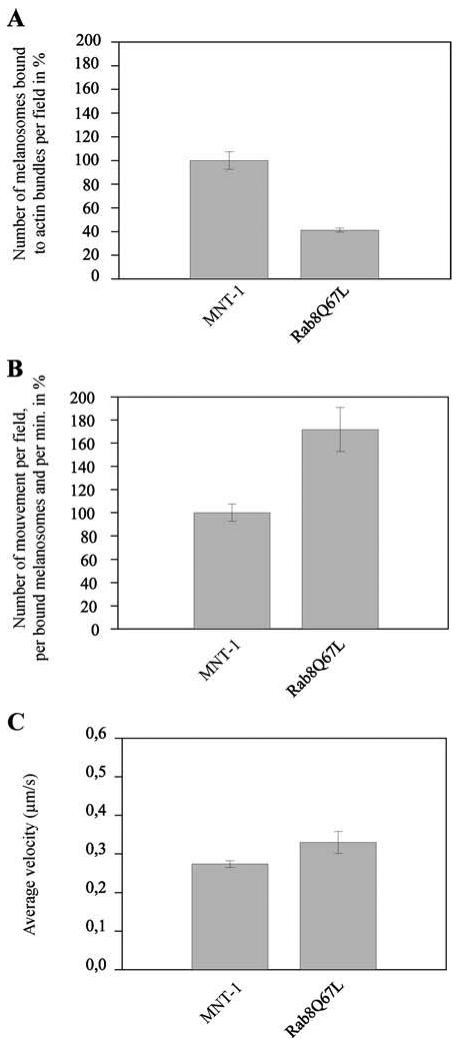

Because GFP-Rab8Q67L increased the number of melanosomes exhibiting in vivo directional movement independent of microtubules, we next examined whether GFP-Rab8Q67L could affect the in vitro movement of melanosomes. We analyzed the movements of melanosomes isolated from cells stably transfected with GFP-Rab8Q67L. The number of melanosomes isolated from these cells that bind actin filaments was reduced by 60% compared with wild-type melanosomes (Figure 9A). However, the number of movements of the actin-bound GFP-Rab8Q67L melanosomes increased by 70% compared with wild-type melanosomes, whereas the average velocity of this population of melanosomes was similar to that of actin-bound melanosomes isolated from nontransfected cells (Figure 9, B and C). Together, these observations suggest that GFP-Rab8Q67L regulates the in vitro movement of melanosomes by controlling their binding to actin filaments

Figure 9.

GFP-Rab8Q67L increases the frequency of actin-dependent melanosome movements. (A) Number of actin-bound melanosomes isolated from wild-type MNT-1 cells was compared with the number of actin-bound melanosomes isolated from GFP-Rab8Q67L–overexpressing cells as described in the Materials and Methods. In the representative experiment shown in A, the mean number of melanosomes from GFP-Rab8Q67L–overexpressing cells that bound actin filaments per field (n = 95) was normalized against the concentration of melanosomes and expressed as a percentage of the normalized number of actin-bound melanosomes isolated from wild-type MNT-1. Errors bars are the mean ± SD of the number of actin-bound melanosomes observed per motility chamber. (B and C) Movements of actin-bound melanosomes isolated from wild-type MNT-1 cells (MNT-1) were compared with those of actin-bound melanosomes isolated from cells overexpressing GFP-Rab8Q67L (Rab8Q67L). (B) Number of movements per minute, per field, and per actin-bound melanosome is expressed as a percentage of the number of movements observed under the same experimental conditions with melanosomes isolated from wild-type MNT-1 cells. Errors bars are the mean ± SD of the number of movements observed per movies in three independent experiments. Statistical analysis comparing wild-type melanosomes and GFP-Rab8Q67L melanosomes by using a chi-square test gave p value = 0.3%. (C) Averages of the instantaneous velocities calculated from the collected data under these different experimental conditions are represented (error bars represent ± SD). Note that GFP-Rab8Q67L increases the number of movements observed for bound melanosomes.

DISCUSSION

We reconstituted the movement of isolated melanosomes on actin bundles, in the absence of cytosol to investigate the regulation of the actin-based movement of melanosomes. It is very likely that the isoform that is thought to move melanosomes in vivo in Xenopus and mammalian cells, myosin Va, is also moving melanosomes isolated from MNT-1 cells in vitro (Hume et al., 2001; Gross et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2002). We observed a large decrease in the frequency of the actin-based movements with melanosomes displaying low levels of a myosin V isoform that was detected with anti-myosin Va antibodies (DIL2) (Figures 1 and 3A) but not with anti-myosin Vc serum (Chabrillat, personal communication).

The main mechanism described up to now for regulation of myosin V-dependent movement of organelles is the reversible association of this motor with the organelles. The Rab protein, Rab27 has been implicated in the recruitment of this myosin to melanosomes, whereas myosin V phosphorylation mediates its dissociation from melanosomes (Karcher et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2001, 2002). Here, we report evidence indicating that a second Rab protein, Rab8, colocalizes with Rab27 on mature melanosomes and regulates the actin-dependent movement of melanosomes.

We first show that the expression of a Rab8 dominant active mutant affects the cellular distribution of melanosomes. Second, we report that expression of the GTP-bound form of Rab8 affects the microtubule-independent movement of melanosomes in vivo. It decreases the number of confined melanosomes and increases the number of melanosomes exhibiting directional and free movements. Third, we observe that Rab8-specific antibodies inhibit the actin-dependent movements of melanosomes in vitro, whereas the GTP-bound dominant active mutant of Rab8 increases the frequency of these movements. Because Rab8 regulates the movement of melanosomes in vitro under experimental conditions where actin bundles are immobilized, it is unlikely that Rab8-dependent regulation of melanosome movement in vivo is restricted to reorganization of the actin network.

It is also unlikely that Rab8 directly controls the activity of the myosin involved in these movements. Loss of function of the gene encoding myosin V (dilute) or genes involved in the recruitment of this myosin to melanosomes, i.e., Rab27 (ashen), and melanophilin (leiden), induced the accumulation of melanosomes in the perinuclear region (Wu et al., 1998, 2001, 2002; Wilson et al., 2000; Hume et al., 2001). In contrast, we observed that the expression of the dominant inactive mutant of Rab8 had no effect on the distribution of melanosomes, whereas the active mutant of Rab8 induced their perinuclear redistribution. Furthermore, GFP-Rab8Q67L changes neither the average velocity of the in vitro and in vivo movements of melanosomes, nor the average exponent of MSD for in vivo directional movements in the absence of microtubules.

The decrease in the number of melanosomes that are confined in the presence of GTP-bound Rab8 in vivo together with the decrease of GFP-Rab8Q67L melanosomes that bound actin filaments in vitro may suggest that the activation of Rab8 induces the dissociation of melanosomes from actin filaments. Actin binding proteins on the surface of melanosomes may play a key role in docking the organelle to actin filaments. However such an interaction needs to be regulated to avoid competition with the force exerted by the molecular motor. It has been reported for example that the phosphorylation of the microtubule binding protein p150glued regulates the transient binding of Golgi membrane to microtubules before their transport (Vaughan et al., 2002). Similarly, Rab8 may regulate an actin binding protein at the surface of the melanosomes. GTP-bound Rab8 might inhibit the binding of this protein to actin filaments and thereby facilitate actin-dependent movements of melanosomes. These mobile melanosomes might, however, cluster in the perinuclear region of the cell due to the additional effect of GTP-bound Rab8 on the organization of actin filaments.

This is the first study demonstrating the contribution of two Rab proteins to the movement of one organelle. Rab8 may regulate the transient binding of melanosomes to actin filaments, whereas Rab27 recruits myosin V to melanosomes. These two Rab proteins must be tightly coordinated to achieve the displacement of melanosomes. A potential candidate for mediating this coordination could be a common effector of these two Rab proteins. Although an actin-binding site has been identified on melanophilin, the molecule bridging myosin Va and Rab27, it is unlikely that Rab8 regulates actin binding by melanophilin because melanophilin does not seem to bind Rab8 (Strom et al., 2002; Fukuda, 2003; Kuroda et al., 2003). Other Rab27 effectors that have been shown to bind Rab8 in vitro are not associated with melanosomes (Strom et al., 2002; Fukuda, 2003). Alternatively, coordination may be achieved through a common nucleotide exchange factor shared by the two Rab proteins. The identification of the actin binding protein controlled by Rab8, as well as the mechanism involved in the coordination of theses two Rab proteins will be examined in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. G. de Saint Basile (Hôpital Necker, Paris, France), A. Zahraoui and A. M. Marzesco, and B. Goud for generous gifts of GFP-Rab27 constructs, GFP-Rab8 constructs, and His tagged β-GDI plasmids, respectively. We also thank Dr. G. Raposo for help with electron microscopy, Dr. L. Lamoreux for crossing the mice and providing the skins, Sylvain Loubéry for help with statistical analysis, and Drs. M. Arpin and J. Plastino for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant to E. C. from the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (Arc no. 4623) and by the Wellcome Trust grant 046038/Z/95/Z to E. S..

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0770) on January 26, 2005.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

References

- Abney, J., Meliza, C., Cutler, B., Kingma, M., Lochner, J., and Scalettar, B. (1999). Real-time imaging of the dynamics of secretory granules in growth cones. Biophys. J. 77, 2887–2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amblard, F., Maggs, A. C., Yurke, B., Pargellis, A., and Leibler, S. (1996). Subdiffusion and anomalous local viscoelasticity in actin networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 4470–4473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpin, M., Friederich, E., Algrain, M., Vernel, F., and Louvard, D. (1994). Functional differences between L- and T-plastin isoforms. J. Cell Biol. 127, 1995–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral, D. C., Ramalho, J. S., Anders, R., Hume, A. N., Knapton, H. J., Tolmachova, T., Collinson, L. M., Goulding, D., Authi, K. S., and Seabra, M. C. (2002). Functional redundancy of Rab27 proteins and the pathogenesis of Griscelli syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 110, 247–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher, A. (1981). Fimbrin is a cytoskeletal protein that crosslinks F-actin in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78, 6849–6853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci, C., Thomsen, P., Nicoziani, P., McCarthy, J., and van Deurs, B. (2000). Rab 7, a key to lysosome biogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 467–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi, A., Granek, R., and Elbaum, M. (2002). Diffusion and direction motion in cellular transport. Phys. Rev. E. Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. Available at: http://link.aps.org/abstract/PRE/v66/e011916. Accessed February 11, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, A. K., Funasaka, Y., Araki, K., Horikawa, T., and Ichihashi, M. (2003). Evidence that small GTPase Rab8 is involved in melanosome traffic and dendrite extension in B16 melanoma cells. Cell Tissue Res. 314, 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echard, A., Jollivet, F., Martinez, O., Lacapere, J.-J., Rousselet, A., Janoueix-Lerosey, L., and Goud, B. (1998). Interaction of a Golgi associated kinesin like protein with Rab6. Science 279, 580–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Amaraoui, A., Schonn, J.-S., Küssel-Andermann, P., Blanchard, S., Desnos, C., Henry, J.-P., Wolfrum, U., Darchen, F., and Petit, C. (2002). MyRIP, a novel Rab effector, enables myosin VIIa recruitment to retinal melanosomes. EMBO Rep. 3, 463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, M. (2003). Distinct Rab binding specificity of Rim1, Rim2, Rabphilin, and Noc2. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 15373–15380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross, S. P., Tuma, M. C., Deacon, S. W., Serpinskaya, A., Reilein, A. R., and Gelfand, V. I. (2002). Interaction and regulation of molecular motors in Xenopus melanophores. J. Cell Biol. 156, 855–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales, C. M., Vaerman, J.-P., and Goldering, J. R. (2002). Rab 11 family interacting protein 2 associates with myosin Vb and regulates plasma membrane recycling. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50415–50421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattula, K., Furuhjelm, J., Arffman, A., and Peränen. (2002). A Rab8-specific GDP/GTP exchange factor is involved in actin remodelling and polarized membrane transport. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3268–3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume, A. N., Collinson, L. M., Rapak, A., Gomes, A., Hopkins, C. R., and Seabra, M. (2001). Rab 27a regulates the peripheral distribution of melanosomes in melanocytes. J. Cell Biol. 152, 795–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, A. A., and Mitchison, T. J. (1993). An assay for the activity of microtubules-based motors on the kinetochores of isolated Chinese hamster ovary chromosomes. Methods Cell Biol. 39, 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, M., Tsukamoto, K., and Hearing, V. J. (1991). Tyrosinases from two different loci are expressed by normal and by transformed melanocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 1147–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordens, I., Fernandez-Borja, M., Marsman, M., Dusseljee, S., Janssen, L., Calafat, J., Janssen, H., Wubbolts, R., and Neefjes, J. (2001). The Rab7 effector protein RILP controls lysosomal transport by inducing the recruitment of dynein-dynactin motors. Curr. Biol. 11, 1680–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachar, B., Urrutia, R., Rivolta, M., and McNiven, M. (1993). Myosin-mediated vesicular transport in the extruded cytoplasm of characean algae cells. Methods Cell Biol. 39, 179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karcher, R. L., Roland, J. T., Zappacosta, F., Hudleston, M. J., Annan, R. S., Carr, S. A., and Gelfand, V. I. (2001). Cell cycle regulation of myosin-V by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Science 293, 1317–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, T. S., Ariga, H., and Fukuda, M. (2003). The actin-binding domain of Slac2-a/melanophilin is required for melanosome distribution in melanocytes. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 5245–5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov, S. A., Langford, G. M., and Weiss, D. G. (1992). Actin-dependent organelle movement in squid axoplasm. Nature 356, 722–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzesco, A. M., Dunia, I., Pandjaitan, R., Recouvreur, M., Dauzonne, D., Benedetti, E., Louvard, D., and Zahraoui, A. (2002). The small GTPase Rab13 regulates assembly of functional tight junctions in epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 1819–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menasche, G., Feldmann, J., Houdusse, A., Desaymard, C., Fischer, A., Goud, B., and de Saint Basile, G. (2003). Biochemical and functional characterization of Rab27a mutations occurring in Griscelli syndrome patients. Blood 101, 2736–2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, E., Severin, F., Backer, J. M., Hyman, A. A., and Zerial, M. (1999). Rab5 regulates motility of early endosomes on microtubules. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peranen, J., Auvinen, P., Virta, H., Wepf, R., and Simons, K. (1996). Rab8 promotes polarized membrane transport through reorganization of actin and microtubules in fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 135, 153–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruyne, D. W., Schott, D. H., and Bretscher, A. (1998). Tropomyosin-containing actin cables direct the Myo2p-dependent polarized delivery of secretory vesicles in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1931–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R, Development Core Team. (2004). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org.

- Raposo, G., Cordonnier, M. N., Tenza, D., Menichi, B., Durrbach, D., Louvard, D., and Coudrier, E. (1999). Association of myosin I with endosomes and lysosomes in mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 1477–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo, G., Tenza, D., Murphy, D. M., Berson, J. F., and Marks, M. S. (2001). Distinct protein sorting and localization to premelanosomes, melanosomes, and lysosomes in pigmented melanocytic cells. J. Cell Biol. 152, 809–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, O., and Cheney, R. (2002). Human myosin-Vc is a novel class V myosin expressed in epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 115, 991–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S. L., and Gelfand, V. I. (1998). Myosins cooperate with microtubules motors during organelle transport in melanophore. Curr. Biol. 8, 161–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S. L., Tint, I. S., and Gelfand, V. I. (1998). In vitro motility assay for melanophore pigment organelles. Methods Enzymol. 298, 361–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott, D. H., Ho, J., Pruyne, D. W., and Bretscher, A. (1999). The COOH-terminal domain of Myo2p, a yeast myosin V, has a direct role in secretory vesicle targeting. J. Cell Biol. 147, 791–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, M., Lee, H., Chin, L., Cordon-Cardo, C., Beach, D., and DePinho, R. A. (1996). Role of the INK4a locus in tumor suppression and cell mortality. Cell 85, 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom, M., Hume, A., Tarafder, A., Barkagianni, E., and Seabra, M. (2002). A family of Rab27-binding proteins. Melanophilin links Rab27a and myosin Va function in melanosome transport. J. Biol. Chem. 28, 25423–25430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sviderskaya, E.V.H., S. P., Evans-Whipp, T. J., Chin, L., Orlow, S. J., Easty, D. J., Cheong, S. C., Beach, D., DePinho, R. A., and Bennett, D. C. (2002). p16(Ink4a) in melanocyte senescence and differentiation. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 94, 446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabb, J. S., Molyneaux, B. J., Cohen, D. L., Kutznetsov, S. A., and Langford, G. M. (1998). Transport of ER vesicles on actin filaments in neurons by myosin V. J. Cell Sci. 111, 3221–3234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, P. S., Miura, P., Henderson, M., Byrne, B., and Vaughan, K. (2002). A role for regulated binding of p150(Glued) to microtubule plus ends in organelle transport. J. Cell Biol. 158, 305–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmann, N., DeRosier, D., Matsudaira, P., and Hanein, D. (2001). An atomic Model of actin Filaments Cross-linked by fimbrin and its implications for bundle assembly and function. J. Cell Biol. 153, 947–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S. M., Yip, R., Swing, D. A., O'Sullivan, T. N., Zhang, Y., Novak, E. K., Swang, R. T., Russel, L. B., Copeland, N. G., and Jenkins, N. (2000). A mutation in Rab27a causes the vesicles transport defects observed in ashen mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 7933–7938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X., Bowers, B., Rao, K., Wei, Q., and Hammer, J. A., 3rd (1998). Visualisation of melanosomes dynamics within wild type and dilute melanocytes suggest a paradigm for myosin V function in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1899–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X., Rao, K., Bowers, M., Copeland, N., Jenkins, N., and Hammer, J. R. (2001). Rab27a enables myosin Va-dependent melanosome capture by recruiting the myosin to the organelle. J. Cell Sci. 114, 1091–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X., Rao, K., Zhang, H., F., W., Sellers, J. R., and Hammer, J. A., 3rd (2002). Identification of an organelle receptor for myosin Va. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.