Abstract

OmpF and OmpC porins were differentially regulated by nutrient limitation and growth rate in glucose- or nitrogen-limited chemostat cultures of Escherichia coli. Transcriptional and translational ompF fusions showed a sharp peak of expression under glucose limitation at D = 0.3 h−1, with lower amounts at lower and higher growth rates. The peak of OmpR-dependent transcriptional stimulation of ompF under glucose limitation in minimal salts media was about 20-fold above nutrient excess levels and 3-fold higher than that achieved with low osmolarity. Analysis of outer membrane protein levels and results of growth competition experiments with porin mutants were consistent with the enhanced role of OmpF under glucose limitation, but not N limitation. In contrast, OmpC was the major porin under N limitation but was increasingly expressed under glucose limitation at very low growth rates approaching starvation, when OmpF was downregulated. In summary, outer membrane permeability under N-limited, sugar-rich conditions is largely based on OmpC, whereas porin activity is a complex, highly sensitive function of OmpF, OmpC, and LamB glycoporin expression under different levels of glucose limitation. Indeed, the OmpF level was more responsive to nutrient limitation than to medium osmolarity and suggested a significant additional layer of control over the porin-regulatory network.

Porin proteins control the permeability of polar solutes across the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria like Escherichia coli (21). Optimal nutrient access is favored by larger porin channels as in OmpF protein (22) or solute-selective proteins like LamB glycoporin in the outer membrane (4). But high outer membrane permeability is a liability in less favorable circumstances, and access of toxic agents or detergents needs to be minimized through environmental control of outer membrane porosity and the increased proportion of smaller OmpC channels in the outer membrane. Normally, the total amount of OmpF and OmpC proteins is fairly constant, but the relative proportion of the two varies subject to factors such as osmolarity of the medium (11, 12), temperature (16), the concentration of certain antibiotics (3), and growth phase (30). Medium with high osmolarity, high temperature, or toxic ingredients favors the expression of OmpC, and medium of low osmolarity and low temperature increases OmpF and diminishes the level of OmpC (28).

The best-understood input into controlling porin levels involves EnvZ and OmpR, which work together as regulators of ompF and ompC gene expression. EnvZ acts as the osmosensor to monitor the changes of external osmolarity to modify OmpR activity by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation (8). OmpR is the actual transcriptional activator of both porin genes (11, 20, 39). High osmolarity results in more OmpR molecules that are phosphorylated, and low osmolarity produces fewer phosphorylated OmpR (OmpR-P) (35). A low level of OmpR-P stimulates the transcription of the ompF gene, and a high level of OmpR-P activates the ompC gene and represses ompF (7, 19, 28, 29, 31). Other known factors regulating porins include some like integration host factor at the transcriptional level and others influencing ompF messenger translation through micF, which encodes an antisense RNA (reviewed in reference 28).

Much less clear than the above is the influence of nutrient concentration and nutrient limitation on porin expression. In nutrient-limited circumstances, bacteria need to scavenge molecules into the cell in order to maintain rapid growth. Outer membrane permeability becomes a bottleneck because the passive diffusion rate of sugar through porins inevitably drops in a linear fashion with decreasing nutrient concentration (5). E. coli is expert in adapting to the micromolar level of nutrients, and it would not be surprising that bacteria attempt to increase outer membrane permeability under hunger conditions. Previous studies indicate that outer membrane protein patterns are altered with nutrient limitation and growth rate in chemostat cultures limited by different nutrients. Continuous culture with glucose and nitrogen limitation of Klebsiella aerogenes NCTC418 changed the relative amounts of proteins with different types of nutrient limitation and with different growth rates (36). Low growth rates in chemostats also alter the antibiotic sensitivity profile of bacteria, presumably due to altered membrane permeability (2). In E. coli cultures, an early study found that glucose limitation strongly stimulated OmpF expression in chemostats at D = 0.2 h−1 such that the ratio of porins to OmpA protein considerably increased and the OmpC level was low. But nitrate limitation caused less OmpF and more OmpC (26). Another indication of the sensitivity of porins to nutritional status was the finding that cyclic AMP (cAMP) in some (as yet undetermined) way affects the ratio of OmpF to OmpC (32).

One adaptive mechanism affecting outer membranes under glucose limitation is the tight growth rate- and glucose concentration-dependent induction of the LamB glycoporin (4). Given the published evidence listed above, it was unlikely that nonspecific porin expression remained constant under changing environmental nutrient levels, and this study provides a detailed picture of the regulation of the major outer membrane proteins. To study the control of major porins OmpF and OmpC under nutrient limitation, chemostat cultures with glucose or nitrogen limitation were used at various growth rates. Setting the dilution rate in a chemostat defines the growth rate as well as the steady-state nutrient concentration in the culture, with lower dilution rates resulting in lower nutrient levels. Three lines of investigation were adopted with the chemostat cultures, including studies with transcriptional and translational fusions, quantitation of outer membrane proteins, and growth competition experiments with strains lacking individual porins. The three approaches revealed a consistent but surprisingly complex pattern of regulation, particularly of OmpF porin levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

All bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. P1 transduction (18) with P1cml clr100 lysates grown on JB100 and NK6027 was employed to introduce ompR::Tn10 and metC162::Tn10 (into MH513, MH225, MC4100, and BW2951 as recipients) to create strains BW3303, BW3304, and BW3337 to BW3340 in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Origin or reference |

|---|---|---|

| BW2951 | MC4100 lamB::λplacMu55 Φ(lamB-lacZ) | 23 |

| BW3303 | MH513 ompR::Tn10 | This study |

| BW3304 | MH225 ompR::Tn10 | This study |

| BW3337 | MH513 metC162::Tn10 | This study |

| BW3338 | MH225 metC162::Tn10 | This study |

| BW3339 | BW2591 metC162::Tn10 | This study |

| BW3340 | MC4100 metC162::Tn10 | This study |

| JB100 | HfrG6 malT(Con)-1 ompR::Tn10 | 14 |

| MC4100 | F−araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 rpsL150 deoC1 relA1 thiA ptsF25 flbB5301 | 34 |

| MH225 | MC4100 Φ(ompC′-lacZ+)10-25 | 11 |

| MH513 | MC4100 araD+ Φ(ompF′-lacZ+)16-13 | 11 |

| NK6027 | Hfr Δ(gpt-lac)5 λ− relA1 metC162::Tn10 spoT1 thi-1 | Escherichia coli Genetic Stock Center no. 6179 |

| ST010 | Δ(lac-pro) llp-2 uvrC279::Tn10 ST001 λST01 lysogen [Φ(ompF′-lacZ+) operon fusion] | 13 |

| ST100 | Δ(lac-pro) llp-2 uvrC279::Tn10 ST001 λST02 lysogen [Φ(ompF′-lacZ+) protein fusion] | 13 |

Growth medium and culture conditions.

The basal salts medium used in chemostats was minimal medium A (MMA) (18) supplemented with amino acids (40 mg/liter) where necessary. Glucose-limited feed medium consisted of 0.02% (wt/vol) glucose and 0.1% (wt/vol) ammonium sulfate. In N-limited feed medium, 0.003% (wt/vol) ammonium sulfate (or 0.006% [wt/vol] histidine) replaced 0.1% (wt/vol) ammonium sulfate, and 0.2% (wt/vol) glucose was present. Batch cultures used Luria-Bertani broth or nutrient broth and MMA containing 0.4% (wt/vol) glucose and 0.1% (wt/vol) ammonium sulfate (18). Batch-cultured bacteria were grown at 37°C with constant shaking, and chemostat culture cells were grown as previously described (4).

Growth competition experiments.

Experiments were performed with the chemostat media described above with (a) glucose limitation, (b) NH3 limitation, and (c) histidine limitation at D = 0.3h−1. For each competition experiment, independent chemostat cultures of each strain were grown for 20 generations. The individual cultures were mixed in a 1:1 ratio prior to monitoring of competitive growth in the same medium at the same dilution rate as that in the inoculum cultures. Mixed cultures were sampled after 2, 4, 8, 24, 48, and 52 to 54 h, and the number of bacteria was determined by total plate counts (quadruplicate samples) as well as counts with different selection markers (e.g., on tetracycline-containing plates for strains carrying the metC162::Tn10 marker).

β-Galactosidase assay.

The β-galactosidase activity of lacZ fusions was assayed by the method of Miller (18) and expressed in Miller units.

Outer membrane fractions and electrophoresis.

The outer membrane protein fraction was prepared by disrupting cells in a French pressure cell and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as described previously (15, 27). Cells from 70-ml chemostat cultures or 5-ml Luria-Bertani broth cultures were harvested by centrifugation, and the pellet was washed twice with 10 ml of 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), resuspended in 10 ml of the same buffer, and broken by passage three times through a French pressure cell at 6,500 lb/in2. The disrupted membrane was then pelleted by centrifugation at 35,000 × g for 1 h and resuspended in 200 μl of sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 16% glycerol, 0.0048% bromophenol blue, 4.8% 2-mercaptoethanol), and samples were boiled for 5 min at 100°C and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 rpm in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge (model 5412) before electrophoresis. Proteins were separated on a 12% acrylamide gel by electrophoresis in the presence of 8 M urea (9), and protein bands were stained with 0.04% Coomassie blue R and destained with 10% acetic acid. OmpF and OmpC were identified by comparison with the protein profiles of control strains MH513(ompF-lacZ) and MH225(ompC-lacZ), respectively.

RESULTS

Effect of nutrient limitation on outer membrane protein patterns.

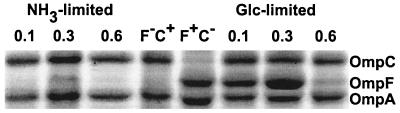

An E. coli K-12 strain wild type for outer membrane profile (strain MC4100) was cultured in chemostats with minimal salts media at three different growth rates either under glucose limitation or with nitrogen limitation in the presence of excess glucose. The cultures reached steady state and were sampled within 3 to 5 days, before mutational changes become evident. Figure 1 shows qualitative comparisons of outer membrane protein profiles under glucose and NH3 limitation at dilution rates of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.6 h−1 (corresponding to doubling times of 7, 2.5, and 1.1 h). These dilution rates with glucose limitation result in steady-state glucose concentrations ranging from below 10−7 M (at D = 0.1 h−1) to above 10−6 M (at D = 0.6 h−1) (24).

FIG. 1.

Outer membrane protein profile of E. coli K-12 wild-type strain MC4100 under glucose and NH3 limitation at dilution rates of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.6 h−1. OmpF and OmpC bands were identified by comparison to the reference strains MH513 and MH225 (F−C+) and (F+C−), respectively.

Under glucose limitation, the amount of OmpC protein was not drastically altered by growth rate, although it was slightly reduced at D = 0.3 h−1 as determined from densitometry of gels such as that in Fig. 1 (result not shown). In striking contrast, the level of OmpF protein was greatly increased at D = 0.3 h−1, but with lower levels at both low and higher dilution rates. The amount of OmpF in excess-glucose, exponential-phase batch culture in MMA was comparable to that found at D = 0.6 h−1 (densitometric results not shown). The low level of OmpF in batch culture can be ascribed to the high osmolarity of the minimal medium, which is over 100 mM with respect to salts and predictably shifted porin expression to OmpC. Nevertheless, the major increase in OmpF protein at D = 0.3 h−1 was observed despite the high osmolarity of the medium (Fig. 1). Indeed, expression was even higher in one-fifth-strength MMA at D = 0.3 h−1 (unpublished results and ompF transcriptional fusion data below).

The amount of OmpC was high and relatively constant at different dilution rates under NH3 limitation. In contrast to glucose limitation, the amount of OmpF protein was very low at all dilution rates under NH3 limitation, with no significant difference among dilution rates. An interesting difference under N limitation was that the proportion of OmpA in the outer membrane was higher than that under glucose limitation at all three dilution rates (densitometric data not shown).

Transcriptional and translational regulation of porin synthesis under nutrient limitation.

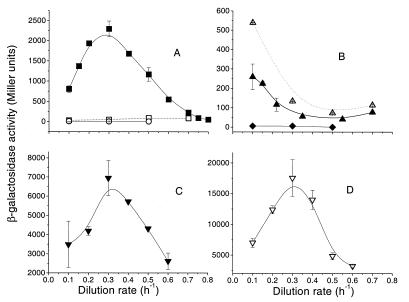

The protein composition of the outer membrane found in Fig. 1 indicated that at least OmpF porin was tightly regulated by nutrient limitation. To test this point, chemostat cultures were also used to study MC4100 derivatives with ompF-lacZ and ompC-lacZ transcriptional and translational fusions at different dilution rates.

Figure 2A shows the transcriptional expression of ompF under glucose limitation. In line with the protein increase shown in Fig. 1, there was a sharp peak of ompF expression under glucose limitation at D = 0.3 h−1, with lower expression at lower and higher growth rates. The peak was about 20-fold above nutrient excess levels (batch cultures with minimal salts medium and 0.2% glucose contained 170 Miller units of activity) and 3-fold higher than that achieved with low osmolarity (cultures in nutrient broth contained about 720 Miller units and those in fivefold-diluted MMA contained about 230 Miller units). The consistency of transcriptional expression with the protein pattern shown in Fig. 1 suggests a significant transcriptional control of OmpF protein amounts under glucose limitation.

FIG. 2.

OmpF and OmpC expression under nutrient limitation. The transcriptional and translational expression levels of porins are shown under glucose and NH3 limitation at different dilution rates. The expression of ompF and ompC genes was monitored by measuring β-galactosidase activities of ompF-lacZ transcriptional fusion in MH513 (■, glucose limitation; □, N limitation) and BW3303 (○, glucose limitation) (A), ompC-lacZ transcriptional fusion in MH225 (▴, glucose limitation; ▵, N limitation) and BW3304 (⧫, glucose limitation) (B), ST010 (▾, ompF operon fusion) with glucose limitation (C), and ST100 (▿, ompF protein fusion), also with glucose limitation (D). The plotted data represents the means of two to five independent determinations at each dilution rate in chemostats.

Conditions of NH3 limitation with excess glucose strongly repressed ompF expression at all dilution rates (Fig. 2A). Fusion expression of MH513 decreased significantly to about 100 U, about 20-fold below the level under glucose limitation at D = 0.3 h−1 (close to that with high-osmolarity minimal medium batch cultures with 130 Miller units).

Expression of ompC in Fig. 2B showed less than a threefold change under glucose limitation at different dilution rates. The highest OmpC expression under glucose limitation was found at the lowest growth rates, and expression decreased from 300 Miller units at D = 0.1 h−1 to about 100 U at higher dilution rates (D = 0.3 to 0.7 h−1), nearly equal to the expression in glucose-rich batch culture. Under NH3 limitation, the expression of ompC increased about 1.5-fold at all dilution rates above that under glucose limitation. The higher transcription at low D values was not evident in an absolute increase in OmpC protein amounts in Fig. 1, and so transcriptional regulation is not the only factor controlling OmpC levels.

To confirm the expression results with an independent set of transcriptional as well as translational fusions, we also tested the ompF-lacZ operon fusion construct in strain ST010 and ompF-lacZ protein fusion ST100 (13). These fusions are present as part of a λ lysogen and have a normal complement of porin genes. With these strains also, the transcriptional expression of ompF-lacZ gave a peak at D = 0.3 h−1 under glucose limitation (Fig. 2C), was slightly lower at D = 0.1 h−1, and was lowest at D = 0.6 h−1, consistent with the pattern in the other results.

The function of ompR in the expression of ompF and ompC under glucose limitation.

Given the extensive change in ompF regulation under glucose limitation, we tested whether the high induction of ompF was dependent on the known transcriptional activator of porin genes, OmpR. Despite the very high level in Fig. 2, all of the expression was abolished in the presence of an ompR::Tn10 mutation, as shown in Fig. 2A and B. Expression of both ompF and ompC under nutrient limitation was entirely OmpR dependent at all dilution rates.

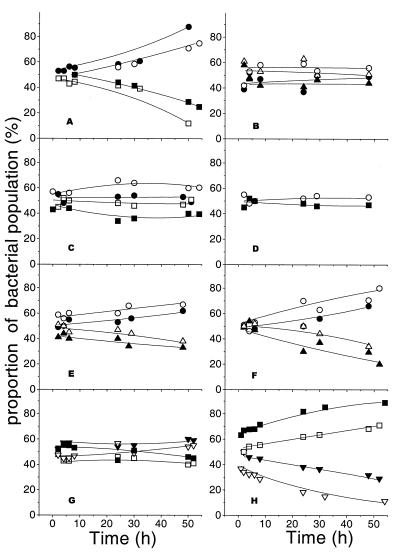

The relative contribution of porins to outer membrane permeability.

To clarify the physiological role of porins in bacteria under nutrient limitation, a series of competitive growth experiments under glucose or N limitation were set up between pairs of strains lacking particular porin proteins. The compared pairs contained additional selectable markers to aid in counting competing strains. To determine that the counting markers were indeed selectively neutral and not influencing growth, experiments were performed with reversed pairings of selectable markers and porin mutation combinations. To start competition experiments, bacteria were cultured in glucose- or N-limited chemostats separately. After 2 days of growth, the cultures were mixed in equal proportions. Competition was monitored in the same medium and at the same dilution rate.

Under glucose limitation at D = 0.3 h−1, the wild-type strain MC4100 (OmpC+ OmpF+ LamB+) had a selective advantage over a mutant without OmpF porin, with the OmpF− strain being gradually washed out (Fig. 3A). In contrast, an OmpC− OmpF+ strain was not significantly growth impaired under glucose limitation in competition with the OmpC+ OmpF+ strain (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that there was a significant difference in the contributions of OmpF and OmpC to glucose diffusion under glucose limitation, entirely consistent with the relative expression of these gene products under glucose limitation.

FIG. 3.

Growth competition between pairs of strains lacking particular porin proteins. Experiments were performed with strains containing the selectable metC::Tn10 marker (open symbols) and those without this marker (solid symbols). Experiments were with glucose and N limitation (with NH3 or histidine limitation) at a dilution rate of 0.3 h−1. The same strains were tested in panels A, C, and D: the OmpF+ OmpC+ LamB+ strains MC4100 (•) and BW3340 (○), competing against OmpF− strains BW3337 (□) and MH513 (■) under glucose (A), NH3 (C), and histidine (D) limitation. The strains in panels B, E, and F were MC4100 (•) and BW3340 (○), competing against OmpC− strains BW3338 (▵) and MH225 (▴) under glucose (B), NH3 (E), and histidine (F) limitation. In panels G and H, the strains were the LamB+ OmpF− strains MH513 (■) and BW3337 (□), competing against LamB− OmpF+ strains BW2951 (▾) and BW3339 (▿) under NH3 and glucose limitation.

In competition experiments under NH3 limitation or histidine limitation, loss of OmpF had little influence on the competitive ability of E. coli (Fig. 3C and D). The OmpC− mutant showed a slightly greater reduction in growth fitness under NH3 limitation (Fig. 3E). Hence, the low level of OmpF shown in Fig. 1 above for N limitation was reflected in the low contribution of OmpF to NH3 permeability, while OmpC is more important than OmpF under N limitation. The relatively small growth disadvantage seen with the OmpC− mutant under NH3 limitation was unexpected, given the high OmpC expression under these conditions in wild-type bacteria, and so the experiments were repeated with another N source, histidine, which has a higher molecular weight (209 as against 17 for NH3). Under histidine limitation, the OmpF− strain was still unimpaired (Fig. 3D) but the OmpC− mutant was more markedly impaired than it was under NH3 limitation (Fig. 3F). Hence, OmpC provides satisfactory channels for satisfying N demand from available amino acids under N limitation but is not completely essential for NH3.

Further experiments with competition between OmpC+ OmpF+ LamB− and OmpC+ OmpF− LamB+ bacteria indicated that there was little difference between loss of OmpF and loss of LamB in their contribution to NH3 permeability (Fig. 3G). This result is consistent with previous data showing that expression of LamB is dramatically repressed under NH3 limitation (23), as is that of OmpF (Fig. 2). On the other hand, LamB was known to contribute to glucose transport at low levels of glucose (4), and so to test the relative contributions of LamB and OmpF, an experiment with competition between pairs of LamB+ OmpF− and LamB− OmpF+ mutants was also carried out. Figure 3H shows that LamB loss created a greater growth disadvantage than did loss of OmpF, and so LamB probably has a greater contribution to glucose transport even at D = 0.3 h−1, the dilution rate giving the peak of OmpF expression in E. coli.

DISCUSSION

Earlier studies concluded that the outer membrane permeability of E. coli for glucose is determined by the major outer membrane porins OmpF, OmpC, and LamB (5, 21). Also known was that different environmental circumstances induce different proportions of these proteins (26). Our results extend these findings to show that each of these porins is optimally induced and functional under different levels of glucose limitation, with the expression of OmpF being particularly sensitive to nutrient level.

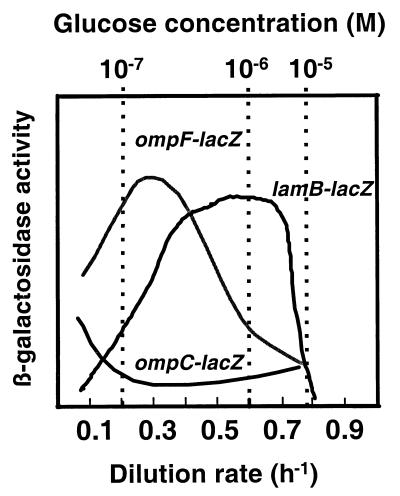

The expression of porins is most strikingly different when the environment of bacteria changes from a glucose-rich state to glucose limitation and eventually glucose depletion and starvation. The optimal scavenging ability of E. coli for glucose is specifically at micromolar medium concentrations of glucose, with lower transport affinity at excess or starvation levels of nutrient (4, 5). There is a sequential change in outer membrane protein composition with decreasing glucose concentrations and growth rate as schematically illustrated in Fig. 4. Yet it is not growth rate per se that controls porin levels but the nature of the limitation, as N limitation gives an entirely different pattern of porin expression, not only for OmpF and OmpC (shown here) but also for LamB (23). As shown in Fig. 4 and as based on published data (33), the glucose concentration in a chemostat drops with decreasing dilution rate (23). Under glucose limitation, the earliest response (starting at above 10−4 M glucose) is induction of the LamB glycoporin, which is maximally induced at approximately 10−6 M medium glucose. It is only then that OmpF expression begins to increase markedly, between 10−6 and 10−7 M glucose. When sugar levels and growth rate are even lower, bacteria switch off both LamB and OmpF and go into a protective mode with the small OmpC channels being increasingly produced. At such low levels of glucose, at D = 0.1 h−1, bacteria stop trying to optimize sugar scavenging strategies and switch to making protectants like trehalose and other stationary-phase responses (24).

FIG. 4.

OmpF, OmpC, and LamB expression patterns during glucose-limited growth in the chemostat. The curves are based on data from Fig. 2 as well as from reference 23.

Since the optimum for OmpF expression does not coincide with the induction of LamB under glucose limitation, there must be differences in the regulatory stimuli controlling these porins. LamB is induced by glucose limitation due to the higher levels of cAMP as well as of endogenous inducer (maltotriose) at D = 0.6 h−1 (23). OmpF expression may be affected by high cAMP levels (32), but the direct role of cAMP in porin regulation is still unexplained. In any case, cAMP levels continue to increase with decreasing dilution rate (25), but OmpF levels decrease below D = 0.3 h−1. So at least one other input is required to explain the pattern.

The results with gene fusions indicated that the high OmpF expression at D = 0.3 h−1 was transcriptionally regulated and entirely OmpR dependent. Previous results have identified low osmolarity and low temperature as being among the conditions stimulating OmpF porin synthesis. As shown in Fig. 1, intermediate levels of glucose limitation gave higher expression than did these other stimuli, even considering that our experiments were at 37°C and with the high osmolarity present in minimal salts. The mechanism of this induction was uninfluenced by micF, which works at the translational level (1) and in which a mutation does not alter OmpF levels at D = 0.3 h−1 (unpublished results). It is also relevant that a further increase in ompF expression is achievable by running chemostats at lower osmolarities and that the expression peaks at D = 0.3 h−1 with MH513 reaching about 2,600 U in one-fifth-strength minimal medium (compared to 2,200 U in full-strength MMA [result not shown]).

The above data suggests that the regulation by nutrient limitation is superimposed on the osmoregulation control of porin expression. The tentative conclusion is that high ompF expression was not due to manipulation of OmpR-P levels but to some other factor(s) regulating transcription. One possibility is through some global, environmentally sensitive factor. Indeed, the regulation of outer membrane permeability is a complex process, involving several global regulators, such as RpoS (30), cAMP/Crp (32), MarA (3), and histone-like DNA binding proteins HNS (10, 38) and integration host factor (39), as well as Lrp (6). Several of these controls operate through micF (28) and so are unlikely to explain the current findings. However, many of these global regulators are potentially affected by nutrient limitation, and their involvement under glucose limitation needs more detailed definition. The only global regulator that has been investigated under chemostat conditions is RpoS (24), whose level increases significantly at D = 0.1 h−1. RpoS-based regulation is therefore unlikely to be responsible for the OmpF peak at D = 0.3 h−1, but RpoS may be involved in the OmpF replacement by OmpC at low dilution rates.

An interesting finding in this study was that NH3-limited growth was not greatly impaired by the loss of any of the major individual porins, OmpF, OmpC, and LamB. Possibly NH3 or NH4+ ions (molecular weight, 17 or 18) are small enough or permeable enough to penetrate bilayers without porins being required. Alternatively, other channels may satisfy NH3 or NH4+ diffusion. For example, reconstituted OmpA protein is capable of forming diffusion pores in bilayers (37). Considering that the level of OmpA was particularly high under N limitation (Fig. 1), OmpA may satisfy an alternative channel requirement. Indeed, a previous study proposed a role for OmpA in amino acid permeability (17), but in vitro studies did not provide supporting evidence for this proposal (37).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank T. Silhavy, M. Berlyn (E. coli Genetic Stock Center), and K. Inoue for kindly supplying bacterial strains. We also thank Lucinda Notley-McRobb for expert advice and assistance and Helen Tweeddale and Zhang E for helpful discussions.

The Australian Research Council provided financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen J, Delihas N. micF RNA binds to the 5′ end of ompF mRNA and to a protein from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9249–9256. doi: 10.1021/bi00491a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown M R W, Collier P J, Gilbert P. Influence of growth rate on susceptibility to antimicrobial agents: modification of the cell envelope and batch and continuous culture studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1623–1628. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.9.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen S P, McMurry L M, Levy S B. marA locus causes decreased expression of OmpF porin in multiple-antibiotic-resistant (Mar) mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5416–5422. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5416-5422.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Death A, Notley L, Ferenci T. Derepression of LamB protein facilitates outer membrane permeation of carbohydrates into Escherichia coli under conditions of nutrient stress. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1475–1483. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1475-1483.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferenci T. Adaptation to life at micromolar nutrient levels: the regulation of Escherichia coli glucose transport by endoinduction and cAMP. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1996;18:301–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1996.tb00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrario M, Ernsting B R, Borst D W, Wiese II D E, Blumenthal R M, Matthews R G. The leucine-responsive regulatory protein of Escherichia coli negatively regulates transcription of ompC and micF and positively regulates translation of ompF. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:103–113. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.103-113.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forst S, Delgado J, Ramakrishnan G, Inouye M. Regulation of ompC and ompF expression in Escherichia coli in the absence of envZ. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5080–5085. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.11.5080-5085.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forst S A, Delgado J, Inouye M. DNA-binding properties of the transcription activator (OmpR) for the upstream sequences of ompF in Escherichia coli are altered by envZ mutations and medium osmolarity. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2949–2955. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.2949-2955.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaal T, Bartlett M S, Ross W, Turnbough C L, Gourse R L. Transcription regulation by initiating NTP concentration—rRNA synthesis in bacteria. Science. 1997;278:2092–2097. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graeme-Cook K A, May G, Bremer E, Higgins C F. Osmotic regulation of porin expression: a role for DNA supercoiling. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1287–1294. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall M N, Silhavy T J. The ompB locus and the regulation of the major outer membrane porin proteins of Escherichia coli K12. J Mol Biol. 1981;146:23–43. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90364-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasegawa Y, Yamada H, Mizushima S. Interactions of outer membrane proteins O-8 and O-9 with peptidoglycan sacculus of Escherichia coli K-12. J Biochem. 1976;80:1401–1409. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue K, Matsuzaki H, Matsumoto K, Shibuya I. Unbalanced membrane phospholipid compositions affect transcriptional expression of certain regulatory genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2872–2878. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2872-2878.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johann M B, Michael D M, Larson T J. Transposon Tn10-dependent expression of lamB gene in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:93–99. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.93-99.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lugtenberg B, Meijers J, Peters R, van der Hoek P, van Alphen L. Electrophoretic resolution of the “major outer membrane protein” of Escherichia coli K12 into four bands. FEBS Lett. 1975;58:254–258. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lugtenberg B, Peters R, Bernheimer H, Berendsen W. Influence of cultural conditions and mutations on the composition of the outer membrane proteins of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1976;147:251–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00582876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manning P A, Pugsley A P, Reeves P R. Defective growth functions of Escherichia coli K12 lacking a major outer membrane protein. J Mol Biol. 1977;116:285–300. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizuno T, Mizushima S. Signal transduction and gene regulation through the phosphorylation of two regulatory components: the molecular basis for the osmotic regulation of the porin genes. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1077–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nara F, Matsuyama S, Mizuno T, Mizushima S. Molecular analysis of mutant ompR genes exhibiting different phenotypes as to osmoregulation of the ompF and ompC genes of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;202:194–199. doi: 10.1007/BF00331636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikaido H, Nakae T. The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. Adv Microb Physiol. 1979;20:163–250. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikaido H, Vaara M. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:1–32. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.1-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Notley L, Ferenci T. Differential expression of mal genes under cAMP and endogenous inducer control in nutrient stressed Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1995;160:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Notley L, Ferenci T. Induction of RpoS-dependent functions in glucose-limited continuous culture: what level of nutrient limitation induces the stationary phase of Escherichia coli? J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1465–1468. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1465-1468.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Notley-McRobb L, Death A, Ferenci T. The relationship between external glucose concentration and cAMP levels inside Escherichia coli—implications for models of phosphotransferase-mediated regulation of adenylate cyclase. Microbiology. 1997;143:1909–1918. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-6-1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Overbeeke N, Lugtenberg B. Expression of outer membrane protein e of Escherichia coli by phosphate limitation. FEBS Lett. 1980;112:229–232. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)80186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peist R, Koch A, Bolek P, Sewitz S, Kolbus T, Boos W. Characterization of the aes gene of Escherichia coli encoding an enzyme with esterase activity. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7679–7686. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.24.7679-7686.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pratt L A, Hsing W H, Gibson K E, Silhavy T J. From acids to OsmZ—multiple factors influence synthesis of the OmpF and OmpC porins in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:911–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pratt L A, Silhavy T J. Identification of base pairs important for OmpR-DNA interaction. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:565–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17030565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pratt L A, Silhavy T J. The response regulator SprE controls the stability of RpoS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2488–2492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russo F D, Slauch J M, Silhavy T J. Mutations that affect separate functions of OmpR, the phosphorylated regulator of porin transcription in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1993;231:261–273. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott N W, Harwood C R. Studies on the influence of the cyclic AMP system on major outer membrane proteins of Escherichia coli K12. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1980;9:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Senn H, Lendenmann U, Snozzi M, Hamer G, Egli T. The growth of Escherichia coli in glucose-limited chemostat cultures: a re-examination of the kinetics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1201:424–436. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silhavy T J, Casadaban M J, Shuman H A, Beckwith J R. Conversion of beta-galactosidase to a membrane-bound state by gene fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3423–3427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slauch J M, Silhavy T J. Genetic analysis of the switch that controls porin gene expression in Escherichia coli K-12. J Mol Biol. 1989;210:281–292. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sterkenburg A, Vlegels E, Wouters J T M. Influence of nutrient limitation and growth rate on the outer membrane proteins of Klebsiella aerogenes NCTC 418. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2347–2355. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-9-2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugawara E, Nikaido H. Pore-forming activity of OmpA protein of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2507–2511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki T, Ueguchi C, Mizuno T. H-NS regulates ompF expression through micF antisense RNA in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3650–3653. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3650-3653.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsui P, Helu V, Freundlich M. Altered osmoregulation of ompF in integration host factor mutants of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4950–4953. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4950-4953.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]