Abstract

The sheath of the filamentous, gliding cyanobacterium Phormidium uncinatum was studied by using light and electron microscopy. In thin sections and freeze fractures the sheath was found to be composed of helically arranged carbohydrate fibrils, 4 to 7 nm in diameter, which showed a substantial degree of crystallinity. As in all other examined motile cyanobacteria, the arrangement of the sheath fibrils correlates with the motion of the filaments during gliding motility; i.e., the fibrils formed a right-handed helix in clockwise-rotating species and a left-handed helix in counterclockwise-rotating species and were radially arranged in nonrotating cyanobacteria. Since sheaths could only be found in old immotile cultures, the arrangement seems to depend on the process of formation and attachment of sheath fibrils to the cell surface rather than on shear forces created by the locomotion of the filaments. As the sheath in P. uncinatum directly contacts the cell surface via the previously identified surface fibril forming glycoprotein oscillin (E. Hoiczyk and W. Baumeister, Mol. Microbiol. 26:699–708, 1997), it seems reasonable that similar surface glycoproteins act as platforms for the assembly and attachment of the sheaths in cyanobacteria. In P. uncinatum the sheath makes up approximately 21% of the total dry weight of old cultures and consists only of neutral sugars. Staining reactions and X-ray diffraction analysis suggested that the fibrillar component is a homoglucan that is very similar but not identical to cellulose which is cross-linked by the other detected monosaccharides. Both the chemical composition and the rigid highly ordered structure clearly distinguish the sheaths from the slime secreted by the filaments during gliding motility.

Electron microscopic studies have shown that cyanobacteria possess complex gram-negative cell walls. Proceeding from the inside, the cytoplasmic membrane is covered by a peptidoglycan layer and an outer membrane. Also, some filamentous gliding cyanobacteria have additional extracellular cell wall layers. These layers are formed by an S layer attached to the outer membrane and an array of parallel, helically arranged surface fibrils on top of the S layer. In all species studied thus far, the helical arrangement of these surface fibrils corresponds to the sense of rotation during gliding motility (11).

While moving, the filaments secrete slime that seems to be a necessary prerequisite for this specific type of motility. The slime is composed of carbohydrate fibrils which are oriented during the translational motion along the helically arranged surface fibrils before they are shed off and left behind as a collapsed slime tube (11). However, many cyanobacteria are able to form sheaths, which are another distinct type of extracellular carbohydrate (2, 4, 19). The rigid sheath in Phormidium spp. is closely associated with the extracellular cell wall layer on top of the cell surface and impairs the gliding motility of the filaments in aged cultures (11).

Previous studies have demonstrated that various cyanobacterial sheaths consist of a meshwork of polysaccharide fibrils which are variably oriented with respect to the cell surface. In some motile cyanobacteria the fibrils extend radially from the cell surface (13, 15), whereas in other species a helical orientation has been demonstrated (14). However, until now, no reports have been published concerning the chemistry of these fibrils, which Frey-Wyssling and Stecher (7) thought to be cellulose in the genus Nostoc. How these sheaths are anchored on the cell surfaces also has not been studied.

In the present study, the structural and biochemical characterization of the sheath of the gliding filamentous cyanobacterium Phormidium uncinatum is described. It is demonstrated that the fibrils of the sheath have properties very similar but not identical to those of cellulose. It is also shown that the organization of the fibrils in the sheaths of various gliding cyanobacteria always correlate with the motion of the species. Finally, it is suggested that specific surface glycoproteins such as oscillin (12) act as platforms for the assembly and attachment of these extracellular carbohydrate structures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cyanobacterial strains and cultivation.

P. uncinatum Baikal was a gift from D.-P. Häder, University of Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany. Other strains examined and listed in Table 2 included Anabaena variabilis (B1403-4b), Lyngbya aeruginosa (B47.79), Oscillatoria amoena (B1459-7), Oscillatoria chalybea (B1459-2), Oscillatoria geminata (B1459-8), Oscillatoria sancta (B74.79), Oscillatoria tenuis (B75.79), Phormidium autumnale (B78.79), and Phormidium foveolarum (B1462-1) from the Göttingen algal culture collection. Anabaena sp. strain C12, Lyngbya sp. strain C36, and Phormidium ambiguum were kindly provided by W. Nultsch, University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany. Oscillatoria princeps and Oscillatoria limosa were both isolated from a canal at Schloss Nymphenburg, Munich, Germany. For the studies described here, all species were grown photoautotrophically on a mineral medium as previously described (11).

TABLE 2.

Correlation between the arrangement of the sheath fibrils and the motion of different filamentous cyanobacteria during gliding motility as examined in this study

| Cyanobacterial groupings based on rotation and arrangement

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Clockwise rotation, clockwise arrangement | Counterclockwise rotation, counterclock- wise arrangement | Nonrotating species, radial arrangement |

| O. chalybea | O. limosa | O. rubescensa |

| O. tenuis | O. princeps | O. geminata |

| O. sancta | L. aeruginosa | P. foveolarum |

| O. amoena | A. variabilis | |

| P. uncinatum | Anabaena sp. strain C12 | |

| P. autumnale | ||

| P. ambiguum | ||

| Lynbgya sp. strain C36 | ||

The observation reported for O. rubescens is according to the work of Jost (13).

Light and electron microscopy.

A Zeiss Axiovert 10 microscope equipped with bright-field, phase-contrast, and differential-interference contrast optics was used to examine living trichomes and to determine the presence of sheaths on the filaments of the different cyanobacteria. To visualize the arrangement of the fibrils within the sheaths, ensheathed filaments were either broken by ultrasonication or viewed with polarized light by using crossed Nicolprisms and a λ/2 filter. For fluorescence microscopy, the samples were observed after staining with various fluorochromes by using epifluorescence illumination and blue-light excitation (filter combination, FT 510 and LP 520).

Isolated sheaths were adsorbed on glow-discharged carbon-coated grids and negatively stained with 2% (wt/vol) unbuffered uranyl acetate or 1.5% (wt/vol) sodium phosphotungstate at pH 6.8, containing 0.015% glucose to promote homogeneous staining. Alternatively, the structures of the sheaths were visualized after air drying by unidirectional shadowing with 1-nm platinum-carbon (Pt/C) under a nominal angle of 45°.

To visualize the deposited slime tubes, carbon-reinforced 50-mesh nickel grids (covered with Pioloform plastic were glow discharged, immersed in medium, and kept in a Petri dish with Phormidium filaments. After 1 or 2 h under appropriate light conditions, rapidly gliding filaments moved over the grid surface, leaving their slime trails behind. The samples were then either negatively stained as described above or rapidly frozen, freeze-dried, and shadowed with Pt/C under a nominal angle of 45°. Electron micrographs were obtained with a Philips CM 12 at an operating voltage of 100 kV.

Freeze fracturing.

Filaments of P. uncinatum used for freeze fracturing were harvested by centrifugation and immediately frozen by plunging or slamming without fixation or cryoprotection. Alternatively, the cells were stepwise infiltrated with glycerol (25%) and frozen in a cryojet (Balzers Process Systems, Balzers, Liechtenstein). Frozen samples were fractured and replicated in a Balzers BA 360 freeze-etching device at −115°C by the protocol of Moor and Mühlethaler (17). The carbon reinforced Pt/C replicas were cleaned with 70% sulfuric acid, rinsed several times with distilled water, and picked up on uncoated, 400-mesh copper grids.

Freeze substitution.

For freeze substitution, ensheathed filaments or formed hormogonia-like cell chains were immediately cryofixed by plunging them into liquid ethane. Substitution was performed in diethyl ether containing 2% (wt/vol) osmium tetroxide by the protocol described earlier (11).

Isolation of the sheath.

The protocol used for isolating cell-free sheaths was based on procedures described by Weckesser and Jürgens (24). Sheathed filaments of P. uncinatum and the other cyanobacterial species were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice in 20 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 7.0). The filaments were then resuspended in the buffer and broken by ultrasonication. Crude sheath preparations were obtained by centrifugation (15 min at 750 × g) and further purified from residual cell wall material by treatment with lysozyme. The enzyme was added to a protein/sheath ratio of 1:5 (dry weight/wet weight), and the digest was performed at 37°C for 24 h. After being washed, the sheaths were extracted with Triton X-100 (2% [wt/vol] in 10 mM disodium EDTA at room temperature for 20 min) or sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; 4% [wt/vol] in acetate buffer at 60°C for 15 min). Finally, the purified sheath material was repeatedly washed with distilled water prior to lyophilization.

Isolation of slime.

Young, motile cultures of P. uncinatum were grown on agar plates covered with a nitrocellulose filter. These culture conditions were selected to optimize gliding motility and, therefore, to favor the production of slime (11). After the filaments had spread over the filter surface, the formed “pellicle” was carefully scraped off, washed several times with water, and mildly homogenized by ultrasonication. The suspension was diluted with water to decrease the viscosity and centrifuged (15 min at 5,000 × g) to remove the bacterial cells. To dissolve the polysaccharide completely, the supernatant was heated for 30 min at 80°C. After centrifugation (30 min at 100,000 × g), this crude preparation was either used directly for precipitation or purified from contaminating proteins by treatment with trichloroacetic acid (12%). Finally, the slime was precipitated by the dropwise addition of 2 volumes of 95% (wt/vol) ethanol and then centrifuged and lyophilized (9).

FTIR spectroscopy.

Spectroscopic analysis of the purified sheaths was performed by means of Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. The spectra were recorded with a Nicolet 740 FTIR spectrometer. About 50 mg of the sheath material, suspended in water, was dried on the Ge crystal designed for multiple internal reflections. A total of 512 scans were taken for each spectrum at a resolution of better than 2 cm−1.

X-ray diffraction analysis and powder diffraction.

For X-ray diffraction analysis, purified lyophilized sheath samples were placed in thin-walled X-ray capillary tubes, mounted in an Iso-Debeyeflex 100 flat-film vacuum camera, and subjected to CuKα radiation. The resulting X-ray patterns were recorded on Kodak direct-exposure film DEF-5 at a specimen-film distance of 7.5 cm.

To improve the detection of weak diffraction signals, the purified sheath material was also measured in an X-ray powder diffractometer (Stoe, Darmstadt, Germany) by using monochromatic MoKα irradiation. The counted impulse rate was recorded online and analyzed with a software package of the manufacturer.

Carbohydrate analysis procedure.

The monosaccharide compositions of the isolated sheaths and the slime were determined by anion-exchange chromatography (HPAE system; Dionex) with appropriate sugar mixtures used as a calibration standard. The relative amounts of the single sugars were calculated from the areas under the peaks. For the chosen concentrations the relative amounts and the detector signal intensities were directly proportional. For the analysis, 5 mg of lyophilized sheath and slime material was hydrolyzed in 4 M trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) for 3 h at 100°C. The hydrolysates were dried, dissolved in bidistilled water, and applied to the column equilibrated with 15 mM NaOH at a flow rate of 1 ml/min (6). Amino sugars were assayed as ninhydrin derivatives on an amino acid analyzer (Beckman). The uronic acid content was determined by the method of Blumenkrantz and Asboe-Hansen (3) with glucuronic acid as a standard.

Further analytical-chemical methods.

Organic phosphate analysis was done according to the procedure of Lowry et al. (16). Sulfate was quantified by the colorimetric rhodizonic acid assay described by Terho and Hartiala (23). For protein and amino acid detections the isolated sheath material was hydrolyzed with 6 N HCl for 1 h at 150°C and analyzed on an amino acid analyzer (Beckman). Analysis of 2-keto-3-deoxyoctonic acid, an indicator of outer membrane contamination in sheaths, was done by the method of Skoza and Mohos (21) with lipopolysaccharide purified from Escherichia coli (Sigma) as a standard.

SDS-PAGE and amino acid sequencing.

For SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), the tricine system of Schägger and von Jagow was used (20), and the 5 to 13% minigels were routinely stained with colloidal Coomassie blue (18). After being blotted on siliconized glass fibers, the extracted protein was cleaved with endoproteinase Lys-C (Boehringer), and the resulting peptides were separated as described previously (reference 12 and references therein). Finally, the amino acid sequence was determined by using a gas phase sequencer (type 470A; Applied Biosystems).

RESULTS

Occurrence of the different exopolysaccharides.

As summarized in Table 1, the production of exopolysaccharides in P. uncinatum differs according to the age of the culture. A highly hydrated slime is produced during the gliding motility period and is left behind as a collapsed thin tube (Fig. 1). By light microscopy it could only be visualized by staining with India ink particles that adhere to the mucus. Although sheaths formed after prolonged cultivation (6 to 7 weeks) were easily visible when using phase contrast or differential interference contrast (Fig. 2A and Fig. 3), these old cultures showed little or no motility. Particularly, ensheathed filaments were never observed to move, and so it seems that the rigid sheaths inhibit gliding motility in Phormidium spp. and in the other cyanobacterial species. After the formation of hormogonium-like cell chains within these ensheathed filaments, the cell chains lost contact with the tight-fitting sheath and started to move again. Occasionally, these short “filaments” left the sheath, and it could be shown by India ink staining that the cells secrete slime during their movements. Therefore, the slime and the sheath seem to play different roles in gliding motility.

TABLE 1.

Characteristic features of the different exopolysaccharides produced by P. uncinatum

| Property | Characteristic features of P. uncinatuma:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Sheath | Slime | |

| Microscopic visibility | Clearly visible with phase and differential-interference contrast | Visible only after staining |

| Anisotropy | Strong | Barely detectable |

| Crystallinity | Yields sharp X-ray diffraction pattern | No diffraction detectable |

| Autofluorescence | Yellow-green under blue-light excitation | Not detectable |

| Physical properties | A rigid structure formed by parallel helically arranged fibrils | An elastic tube formed by fibrils |

| Compositional analysis | Complex heteropolysaccharide containing homoglucan fibrils | Complex heteropolysaccharide |

| Chemical stability | Stable in 10 N KOH for 1 h | Completely dissolved in 1 N KOH after 5 min |

| Production according to age of cultures | Found only in aged cultures | Found in young, highly motile cultures |

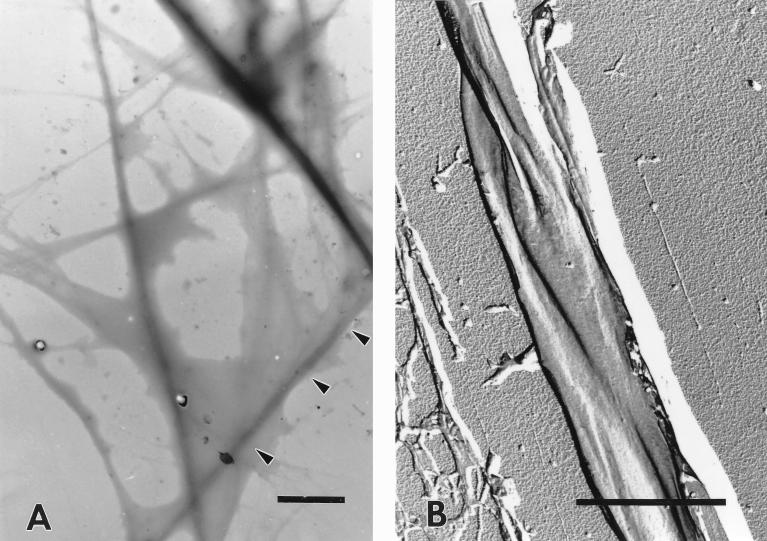

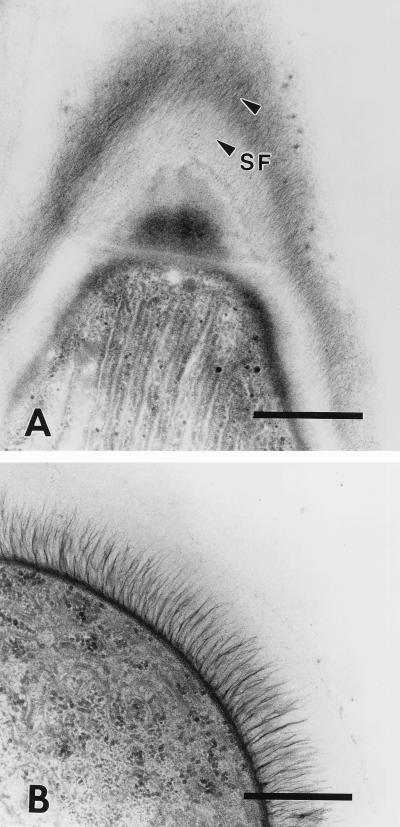

FIG. 1.

(A) Electron micrograph of negatively stained slime tubes of P. uncinatum. The uranyl acetate stain used not only contrasts with the highly hydrated slime tubes negatively but sometimes infiltrates the tubes (arrowheads). Bar, 30 μm. (B) Electron micrograph of a frozen and partially freeze-dried, collapsed slime tube which was left behind a rapidly gliding P. uncinatum filament. The surface of the elastic tube shows characteristic folds. Bar, 10 μm.

FIG. 2.

(A) Differential interference contrast micrograph of the isolated sheaths of P. uncinatum (large arrowheads). Some of the tube-like structures were disrupted by the ultrasonication used during preparation. The curly appearance of disrupted sheaths (small arrowheads) is the consequence of the helical arrangement of the fibrils within the sheaths. Bar, 50 μm. (B) Electron micrograph of the thin section of an isolated sheath. Note the compact fabric of the sheath fibrils after cryosubstitution and the absence of remnants of the outer membrane. Bar, 2 μm.

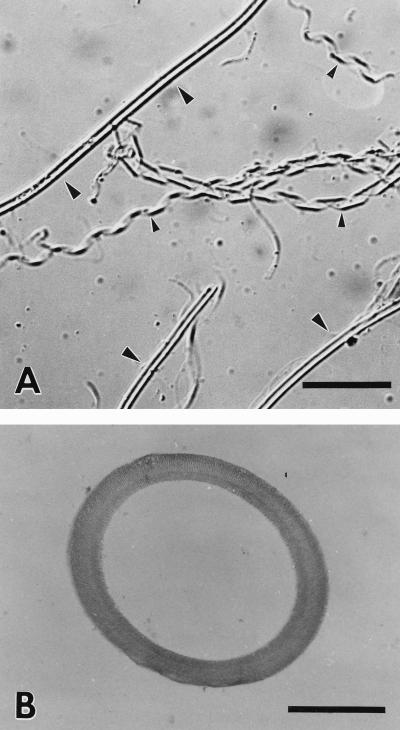

FIG. 3.

Differential-interference contrast micrographs illustrating the correlation between the structure of the sheaths and the motion of various filamentous cyanobacteria. (A) The counterclockwise-rotating species O. princeps, in which the counterclockwise-arranged sheath fibrils can be directly observed (arrowheads). (B) The sheath of the clockwise-rotating species O. tenuis has been disrupted by ultrasonication and shows a curly appearance caused by the clockwise helical arrangement of the fibrils within the sheath (the appearance is nearly identical to that of the sheath of P. uncinatum in Fig. 7). (C and D) P. foveolarum and O. geminata, respectively, are nonrotating cyanobacteria that possess sheaths formed by radially arranged fibrils (see also Fig. 5B), as indicated by the straight ends of the sheaths after disruption (arrowheads) and the characteristic anisotropy observed when using polarized light (pictures not shown). All bars, 10 μm.

Light microscopic observations.

As can be seen from Fig. 2A, the protocol used for the isolation of the sheaths of P. uncinatum resulted in preparations that were devoid of cells. The mechanical stress necessary to break up the filaments often tears the tube-like sheaths, resulting in the curled structures visible on the micrograph (see also Fig. 3B). After further purification the sheaths were considered to be homogeneous and of fairly high purity (Fig. 2B) based upon the absence of phosphorus and 2-keto-3-deoxyoctonic acid, suggesting negligible membrane contamination. The isolated sheaths showed a weak yellow-green autofluorescence and an intense staining with the cellulose-specific fluorochrome Calcofluor White, with aniline blue, and with sulfuric acid-iodine. None of these staining reactions could be observed for the isolated slime secreted by the filaments during gliding motility.

Furthermore, the zinc chloride-iodine reaction of the sheath for cellulose was negative, as was the phloroglucinol reaction for lignins and the I2KI staining for amyloids. However, the most striking difference between both exopolysaccharides was the strong positive anisotropy of the sheaths. This anisotropy was weak or barely detectable for the slime. The characteristic birefringence indicated that the sheaths are composed of fibrillar elements arranged helically with respect to the filament long axis, which possesses a substantial degree of crystallinity.

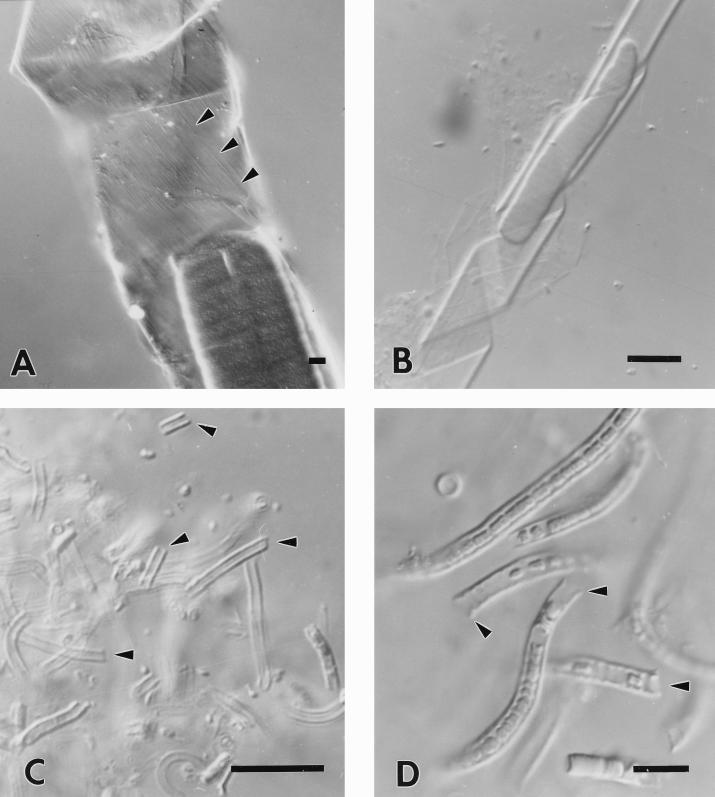

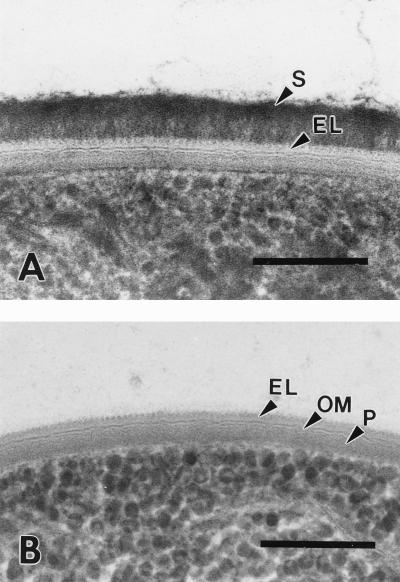

Fine structure of the sheath.

Ultrathin sections of cryosubstituted old-aged filaments of P. uncinatum showed that the sheath consists of a single layer of fine fibrillar material with a total thickness of up to 0.3 μm (Fig. 2B and 4A). The sheath is directly attached to the complex extracellular cell wall layer formed by an S layer and the oscillin surface fibrils (Fig. 4). In accordance with studies on Leptothrix discophora and Sphaerotilus natans (5, 8, 10), the structural appearance of the Phormidium sheath revealed a more compact fabric after cryosubstitution than conventionally processed samples (compare Fig. 4A to Fig. 5A). Nevertheless, as expected from light microscopy, both preparations clearly show that the individual sheath fibrils form a right-handed helix around the cylindrical trichome of P. uncinatum (Fig. 6 and 7; compare also with Fig. 3B). Therefore, the orientation of the sheath fibrils corresponds with the sense of rotation during the screw-like motion of the filaments (11). This correlation between the sheath fibril arrangement and the motion of different cyanobacteria was a characteristic feature found in all gliding filamentous cyanobacteria used in this study and is presented in Table 2 and Fig. 3 and 5. Interestingly, species like Anabaena variabilis or Phormidium foveolarum (Fig. 5B and Fig. 3C), which do not rotate, developed in aged cultures sheaths in which the sheath fibrils were radially arranged with respect to the cell surfaces. It would be difficult to explain this arrangement by the proposed shear-oriented polymerization of the fibrils during gliding motility (14).

FIG. 4.

(A) Cross-section of a cryosubstituted ensheathed filament of P. uncinatum showing the close contact between the sheath (S) and the underlying complex external layer of the cell wall (EL). (B) Cross-section of a cryosubstituted newly formed hormogonium-like cell chain. After the contact with the tight-fitting sheath is loosened, the cells still possess the complex external cell wall layer with its serrated substructure formed by the oscillin fibrils. EL, external layer; OM, outer membrane; P, peptidoglycan. All bars, 100 nm.

FIG. 5.

P. uncinatum. Tangential section of an old ensheathed filament showing the helical, clockwise arrangement of the individual sheath fibrils (SF). The fibrillar network is more visible in these conventionally processed filaments than in the cryosubstituted samples shown in Fig. 4A. (B) Structure of the sheath of A. variabilis. As in all other nonrotating cyanobacteria, the individual sheath fibrils are radially arranged with respect to the filament surface. All bars, 1 μm.

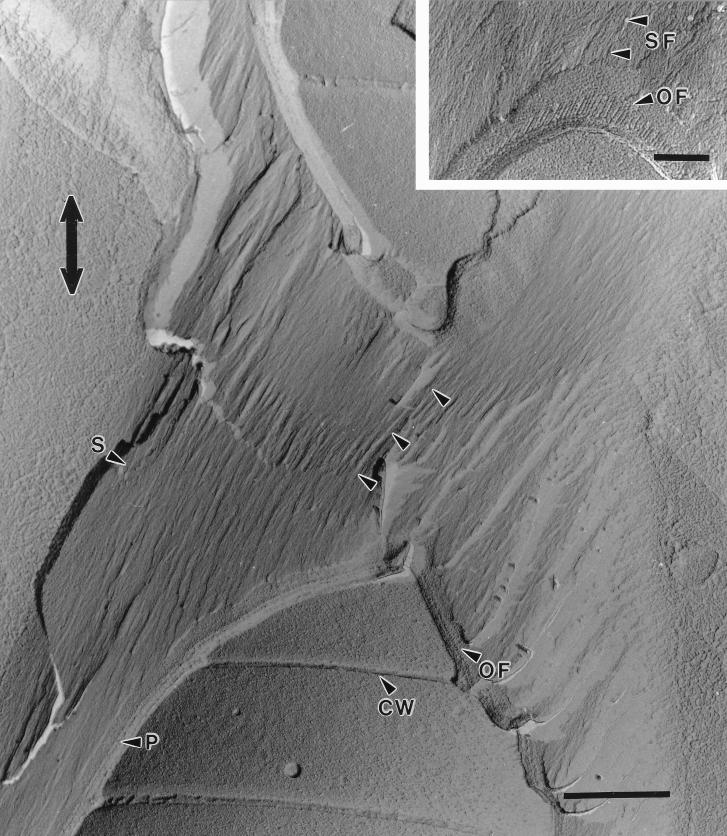

FIG. 6.

Freeze fracture of an ensheathed filament of P. uncinatum showing the helical, clockwise arrangement of the sheath fibrils (small arrowheads). The close contact between the sheath and the complex external layer of the cell wall is clearly visible at the lower right edge of the broken cell, where the serrated surface fibrils, formed by the glycoprotein oscillin (OF), directly interact with the overlying sheath (compare with Fig. 4). The double-headed arrow indicates the long axis of the filament. CW, cross wall; OF, oscillin fibrils; P, peptidoglycan; S, sheath. Scale bar, 1 μm. The inset shows the enlarged view of the contact zone between the sheath and the cell surface. Note the correspondence of the arrangement of the sheath fibrils (SF) and the oscillin fibrils. Bar, 100 nm.

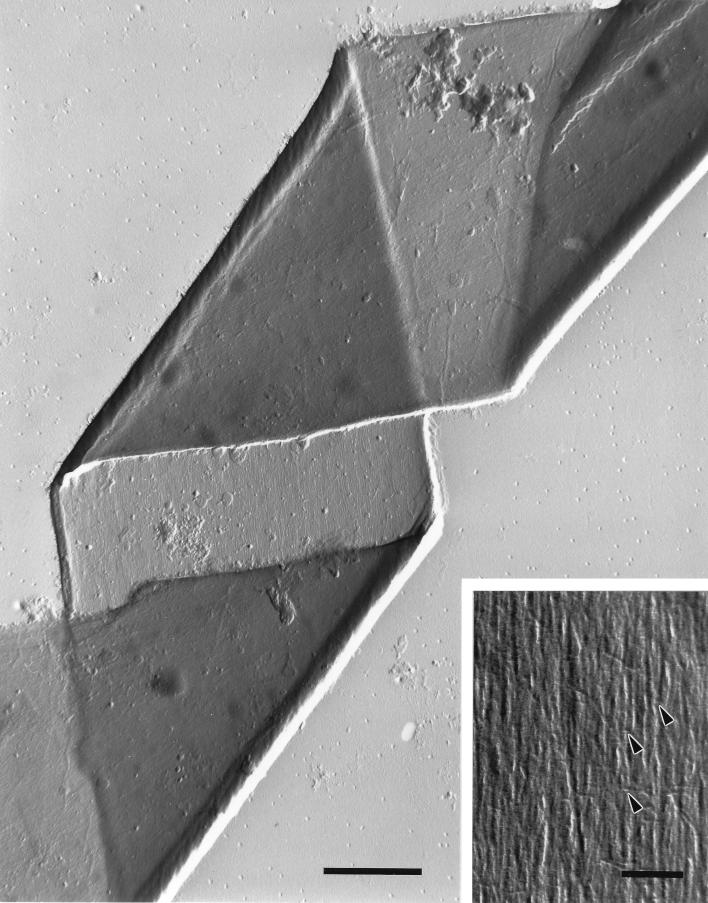

FIG. 7.

Electron micrograph of a metal-shadowed, air-dried sheath of P. uncinatum. The tube-like structure is disrupted by ultrasonication and clearly shows the helical arrangement of the sheath fibrils. Bar, 2 μm. The parallel bundles of fibrils connected by anastomoses and cross-linked through short pin-like elements (arrowheads) are enlarged in the inset. Bar, 200 nm.

Freeze fracture was used to study the carbohydrate network of the sheath of P. uncinatum without fixation or dehydration, confirming the helical arrangement of the sheath fibrils (Fig. 6). Individual fibrils measured 4 to 7 nm in diameter and lay in parallel with a pitch of about 65 ± 3°. The preparations also allowed visualization of the contact zone between the sheath and the underlying cell wall surface, which could not be observed in thin sections. As seen in the inset of Fig. 6, the sheath fibril orientation corresponds to the orientation of the oscillin glycoprotein surface fibrils previously described (11, 12).

Electron microscopy of metal-shadowed, air-dried preparations showed the fibrillar texture of the sheaths (Fig. 7). Similar to the appearance of a plant cell wall, adjacent sheath fibrils are connected by anastomoses forming domains similar to the crystallites of the cellulose microfibrils. Additionally, individual fibrils may be cross-linked through short pin-like connections (arrowheads in Fig. 7). The observed anisotropic properties of the sheath seemed to be determined by these highly ordered fibril aggregates, which are composed of carbohydrate chains with their axes parallel to the axes of the fibrils.

Compositional analysis of isolated sheaths.

Comparison of the dry weight of the isolated sheath material with intact cell filaments demonstrated that the sheath accounted for approximately 21% of the biomass in old Phormidium cultures; this was a much higher value than the amount of extruded slime material, which was estimated to be only about 5% of the biomass (11).

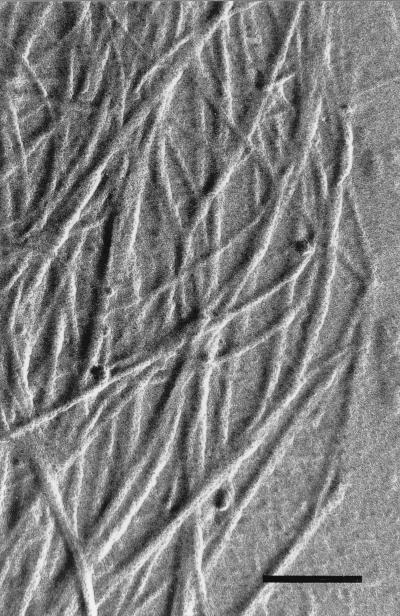

The identification of the component monosaccharides of the isolated sheaths was done by high-pressure liquid chromatography of acid-hydrolyzed samples. To ensure detection of all monosaccharides, the polysaccharide material was subjected to hydrolysis under several different conditions. By these protocols, five different neutral sugars were identified as major constituents of the sheath: glucose (ca. 60%), galactose (18%), xylose (12%), arabinose (<5%), and rhamnose (<5%). The same neutral sugars were also found to compose the slime and the carbohydrate moiety of the surface glycoprotein oscillin (Table 3). The predominance of glucose in the sheath was even more pronounced (ca. 80%) after a pretreatment with 1 M TFA for 1 h at 100°C, which dissolved the pin-like connections and loosened the fibrillar meshwork (Fig. 8). The intact appearance of the remaining fibrils upon electron microscopy strongly suggests that the fibrillar elements of the sheaths are composed of a homoglucan. Neither amino sugars nor uronic acids, phosphate, or sulfate groups could be detected, suggesting that the content of these components was below the detection limits for the assays employed.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the monosaccharide compositions of sheath, slime, and surface glycoprotein oscillin

| Sugar | Monosaccharide composition (%)a of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sheath | Slime | Oscillin | |

| Arabinose | <5 | 11 | <5 |

| Fucose | 9 | <5 | |

| Galactose | 18 | 10 | 3 |

| Glucose | 60 | 34 | 18 |

| Rhamnose | <5 | 3 | 9 |

| Xylose | 12 | 33 | 60 |

All determinations reported here are not quantitative and indicate only the relative amounts of the individual sugar components.

FIG. 8.

Electron micrograph of Pt/C shadowed sheath fibrils after treatment with TFA for 1 h at 100°C. The pin-like connections between neighboring sheath fibrils are dissolved, and the fibrillar meshwork disintegrates into single homoglucan fibrils. Bar, 50 nm.

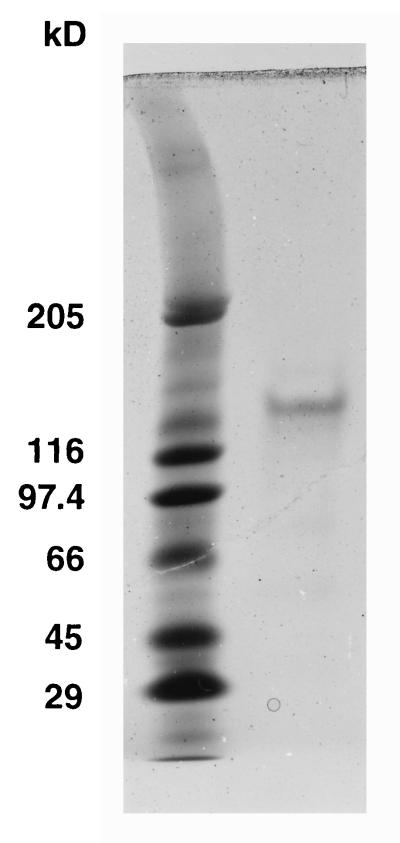

SDS-PAGE of isolated sheaths revealed only a weakly stained band with a molecular mass of 130 kDa (Fig. 9), suggesting that this sheath-associated protein is the surface fibril-forming protein oscillin (12). Oscillin is a 66-kDa protein which not only forms the contact zone between the filament surface and the sheath but is arranged helically just as the sheath fibrils are (see also Fig. 5A and Fig. 6). This interpretation was further confirmed by sequencing of a Lys-C-derived peptide of the sheath-associated protein. The revealed amino acid sequence, GxDxIGFFTGAGDGSNNLGLNLSG, is identical to the oscillin sequence between amino acid positions 136 and 159 (GenBank accession number AF002131). Generally, there were no differences in the chemical compositions of the sheaths isolated with or without detergents. However, in the SDS-treated fractions no association between the sheath and oscillin could be detected.

FIG. 9.

SDS-PAGE of the proteins associated with the isolated sheath of P. uncinatum. The only protein found in larger quantities is the surface glycoprotein oscillin, which seems to act as a platform for the assembly and attachment of the sheath to the cell surface (compare with Fig. 4). Oscillin could not be detected in the SDS-isolated sheaths.

Biophysical characterization of the sheath.

The results of the compositional analysis of isolated sheath and slime material could be further confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy. Both recorded spectra showed a characteristic triple peak centered at 1,030 cm−1 that is typical for polysaccharides but which clearly differed within this region, reflecting the molecular differences of the two polymers.

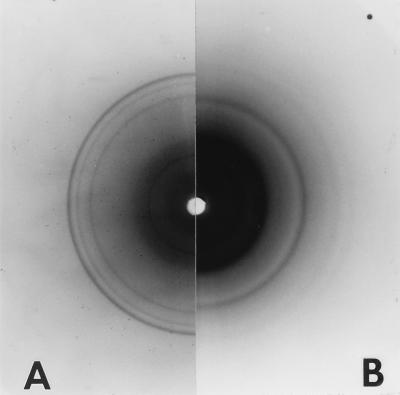

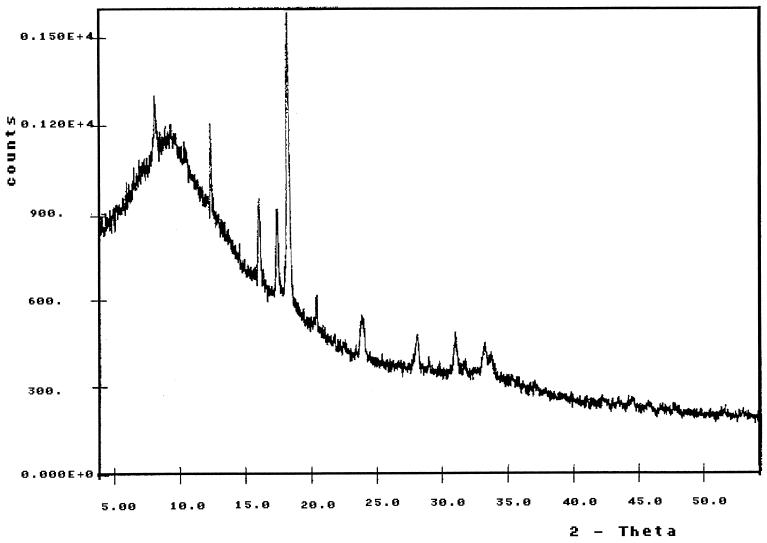

In order to obtain more information about the bonding of the carbohydrate backbone in the crystalline part of the sheaths, X-ray crystallography was used. As shown in Fig. 10A, the isolated and purified sheaths gave a diagram with four diffraction lines: a set of three weak rings at 0.541, 0.333, and 0.253 nm and a stronger sharp ring at 0.221 nm. This diffraction pattern was clearly different from the characteristic lines of cellulose (Fig. 10B), which displayed reflections at 0.605, 0.541, 0.391, and 0.263 nm. To detect even weaker diffraction signals, the sheath material was also measured in an X-ray powder diffractometer (Fig. 11). The counted impulse rate was recorded, and four additional diffraction signals could be identified corresponding to 0.170, 0.146, 0.132, and 0.124 nm. Therefore, the fibrillar component of the sheath of P. uncinatum has a substantial degree of crystallinity, a finding in agreement with the strong anisotropy observed by light microscopy.

FIG. 10.

X-ray diagrams of the isolated and purified sheaths of P. uncinatum (A) and of a test specimen of cellulose powder from cotton linters (B). Both materials gave sharp diffraction lines representing different types of bonding and lattice orders of the homoglucans.

FIG. 11.

X-ray powder diffraction pattern of the isolated and purified sheaths of P. uncinatum. The recorded sharp signals indicate a substantial degree of crystallinity of the sheath material. The four prominent peaks correspond to the four diffraction lines in the X-ray diagram (Fig. 10A). The additional diffraction signals indicate further characteristic small spacings within the lattice of the crystalline sheath material.

DISCUSSION

Different exopolysaccharides for different purposes.

P. uncinatum is able to produce different exopolysaccharides which seem to serve different functions. The slime is only produced by actively moving filaments and consists of highly hydrated heteropolysaccharide fibrils which show, especially at the inner contact zone, an orientational arrangement identical to that of the oscillin fibrils on the filament surface as previously shown (11). These slime fibrils form a flexible tube which is only temporarily attached to the filament before it is shed off and left behind. Unlike slime, the sheath is only produced in old cultures and may protect the filaments from unfavorable conditions such as desiccation. It forms a rigid tube-like structure composed of helically arranged fibrils which are permanently attached to the cell surface and thereby inhibit gliding motility. Various nutritional and environmental factors seem to control which type of exopolysaccharide is formed by the Phormidium filaments. As in Leptothrix discophora strain SS-1 (1) or Gloeothece sp. (22), the sheath of Phormidium appears not to be a stable cell structure, and the ability to form a sheath was frequently lost during repeated subculture, whereas the ability to secrete slime was invariably found as long as the filaments displayed gliding motility.

Structure and formation of the sheaths.

A striking feature of all investigated sheaths is that the orientation of the sheath fibrils is always correlated with the motion of the filaments during gliding; i.e., the fibrils form a right-handed helix in the clockwise-rotating species and a left-handed helix in the counterclockwise-rotating species and are radially arranged in the nonrotating cyanobacteria (Table 2; Fig. 3 and Fig. 5). The correspondence of fibril arrangements with the paths of the filaments was thought to be the result of a shear-oriented polymerization of the sheath monomers (14). Since ensheathed filaments were never observed to move, it is unlikely that the arrangement of the fibrils could be the consequence of shear forces during motility. Instead, it now seems likely that the assembly and attachment of the sheaths via helically or radially arranged surface glycoproteins are the reasons for the observed identical orientational arrangement, an interpretation strongly suggested by the following circumstantial evidence. First, in thin sections the oscillin fibrils directly contact the sheath. Second, both structures are arranged in an identical helical fashion around the filament, which can even be directly visualized in freeze fractures. Finally, the only protein found to be associated with the sheaths after isolation is the surface glycoprotein oscillin.

These observations further indicate that the direct binding of the sheath and the surface proteins can be disrupted by the filament to form short hormogonium-like parts of the filament. These hormogonium-like cell chains are able to move again and have all of the features suggested to be required for gliding motility; i.e., they secrete slime and possess a surface topography created by specific glycoproteins such as oscillin (12).

Fibrillar component of the sheath.

According to the light-microscopic observations and the X-ray diffraction pattern, the sheath of P. uncinatum consists mainly of a fibrillar component with a substantial degree of crystallinity. Furthermore, these results, together with the positive staining reactions, the compositional analysis, and the relatively high resistance of the sheath to chemical degradation, indicate that the microfibrils are formed by a homoglucan with properties very similar but not identical to those of cellulose. The FTIR spectroscopy gave weak indications that the sheath fibrils might consist of a β-1,3-homoglucan; however, the actual type of bonding between the glucose monomers has not been assigned.

From the comparison of the composition of the sheath before and after acid pretreatment, the other four monosaccharides found in the sheath seem to be the components of the pin-like structures. These complex heteropolysaccharide elements might stabilize the fabric of the sheath by cross-linking, giving the structure its characteristic rigidity.

Although it now seems reasonable to explain how complex carbohydrate structures such as sheaths are attached to cyanobacterial cell surfaces, it is still difficult to understand the actual processes of their secretion and assembly. One might speculate that the single fibrils are synthesized by the junctional pore complexes. These pore complexes also seem to be involved in the process of slime secretion (11), and so it may be that the cells are able to switch their polysaccharide production in response to different environmental stimuli.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Wolfgang Baumeister for continuous generous support and encouragement, Julius Schneider for expert assistance in powder diffractometry, Margit Bauer for her help in X-ray crystallography, and Mary Kania for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams L F, Ghiorse W C. Physiology and ultrastructure of Leptothrix discophora SS-1. Arch Microbiol. 1986;145:126–135. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adhikary S P, Weckesser J, Jürgens U J, Golecki J R, Borowiak D. Isolation and chemical characterization of the sheath from the cyanobacterium Chroococcus minutus SAG B.41.79. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:2595–2599. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumenkrantz N, Asboe-Hansen G. New method for quantitative determination of uronic acids. Anal Biochem. 1973;54:484–489. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drews G, Weckesser J. Function, structure and composition of cell walls and external layers. In: Carr N G, Whitton B A, editors. The biology of cyanobacteria. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1982. pp. 333–357. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emerson D, Ghiorse W C. Ultrastructure and chemical composition of the sheath of Leptothrix discophora SP-6. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7808–7818. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7808-7818.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feichtinger K. Die Glykosylierungsstellen und die Strukturen der Oligosaccharide des Membranglykoproteins Dipeptidylpeptidase IV (CD26). Ph.D. thesis. Munich, Germany: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frey-Wyssling A, Stecher H. Über den Feinbau des Nostoc-Schleimes. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat Abt Histochem. 1954;39:515–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham L L, Harris R, Villiger W, Beveridge T J. Freeze-substitution of gram-negative eubacteria: general cell morphology and envelope profiles. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1623–1633. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1623-1633.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray J S S, Brand J, Koerner T A W, Montgomery R. Structure of an extracellular polysaccharide produced by Erwinia chrysanthemi. Carbohydr Res. 1993;245:271–287. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(93)80077-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoeniger J F, Tauschel H D, Stokes J L. The fine structure of Sphaerotilus natans. Can J Microbiol. 1973;19:309–313. doi: 10.1139/m73-051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoiczyk E, Baumeister W. Envelope structure of four gliding filamentous cyanobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2387–2395. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2387-2395.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoiczyk E, Baumeister W. Oscillin, an extracellular Ca2+-binding glycoprotein essential for gliding motility of cyanobacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:699–708. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5971972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jost M. Die Ultrastruktur von Oscillatoria rubescens D.C. Arch Mikrobiol. 1965;50:211–245. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamont H C. Shear-oriented microfibrils in the mucilaginous investments of two motile oscillatoriacean blue-green algae. J Bacteriol. 1969;97:350–361. doi: 10.1128/jb.97.1.350-361.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leak V L. Fine structure of the mucilaginous sheath of Anabaena sp. J Ultrastruct Res. 1967;21:61–74. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(67)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowry O H, Robets N H, Leiner K Y, Wu L M, Farr A L. The quantitative histochemistry of brain. J Biol Chem. 1954;207:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moor H, Mühlethaler K. Fine structure in frozen-etched yeast cells. J Cell Biol. 1963;17:609–628. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.3.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuhoff V, Arold N, Taube D, Ehrhardt W. Improved staining of proteins in polyacrylamide gels with clear background at nanogram sensitivity using Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 and R-250. Electrophoresis. 1988;9:255–262. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150090603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pritzer M, Weckesser J, Jürgens U J. Sheath and outer membrane components from the cyanobacterium Fischerella sp. PCC 7414. Arch Microbiol. 1989;153:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skoza L, Mohos S C. Stable thiobarbituric acid chromophore with dimethyl sulfoxide: application to sialic acid assay in analytical de-O-acetylation. Biochem J. 1976;159:457–462. doi: 10.1042/bj1590457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tease B E, Walker R W. Comparative composition of the sheath of the cyanobacterium Gloeothece ATCC 27152 cultured with and without combined nitrogen. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:3331–3339. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terho T T, Hartiala K. Method for the determination of the sulfate content of glycosaminoglycans. Anal Biochem. 1971;41:471–476. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weckesser J, Jürgens U J. Cell walls and external layers. Methods Enzymol. 1988;167:173–188. [Google Scholar]