Key Points

Question

What is the association of decreased use of neoadjuvant radiotherapy in nonlocally advanced rectal cancer with cancer-related outcomes and overall survival at a national level?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 2775 patients with colorectal cancer, the decreased use of neoadjuvant radiotherapy from 87% to 37% was not associated with the local regional recurrence rate (5.8% vs 5.5%). The overall survival improved from 79.6% to 86.4%.

Meaning

The results of this study suggest that with routine use of magnetic resonance imaging and the continued improvement of the quality of rectal cancer surgery, neoadjuvant radiotherapy may safely be omitted for most cases of localized rectal cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Neoadjuvant short-course radiotherapy was routinely applied for nonlocally advanced rectal cancer (cT1-3N0-1M0 with >1 mm distance to the mesorectal fascia) in the Netherlands following the Dutch total mesorectal excision trial. This policy has shifted toward selective application after guideline revision in 2014.

Objective

To determine the association of decreased use of neoadjuvant radiotherapy with cancer-related outcomes and overall survival at a national level.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter, population-based, nationwide cross-sectional cohort study analyzed Dutch patients with rectal cancer who were treated in 2011 with a 4-year follow-up. A similar study was performed in 2021, analyzing all patients that were surgically treated in 2016. From these cohorts, all patients with cT1-3N0-1M0 rectal cancer and radiologically unthreatened mesorectal fascia were included in the current study. The data of the 2011 cohort were collected between May and October 2015, and the data of the 2016 cohort were collected between October 2020 and November 2021. The data were analyzed between May and October 2022.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcomes were 4-year local recurrence and overall survival rates.

Results

Among the 2011 and 2016 cohorts, 1199 (mean [SD] age, 68 [11] years; 430 women [36%]) of 2095 patients (57.2%) and 1576 (mean [SD] age, 68 [10] years; 547 women [35%]) of 3057 patients (51.6%) had cT1-3N0-1M0 rectal cancer and were included, with proportions of neoadjuvant radiotherapy of 87% (2011) and 37% (2016). Four-year local recurrence rates were 5.8% and 5.5%, respectively (P = .99). Compared with the 2011 cohort, 4-year overall survival was significantly higher in the 2016 cohort (79.6% vs 86.4%; P < .001), with lower non–cancer-related mortality (13.8% vs 6.3%; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this cross-sectional study suggest that an absolute 50% reduction in radiotherapy use for nonlocally advanced rectal cancer did not compromise cancer-related outcomes at a national level. Optimizing clinical staging and surgery following the Dutch total mesorectal excision trial has potentially enabled safe deintensification of treatment.

This cross-sectional study examines the association of decreased use of neoadjuvant radiotherapy with cancer-related outcomes and overall survival.

Introduction

Randomized clinical trials have demonstrated a decrease in locoregional recurrence (LR) with the use of neoadjuvant short-course radiotherapy (nSCRT) as compared with total mesorectal excision (TME) alone for locally resectable rectal cancer.1,2 The landmark trials were conducted mainly during the 1990s, an era when preoperative imaging for rectal cancer was not performed, while preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is now standard of care for locoregional staging. Despite quality-controlled TME surgery, the circumferential resection margin (CRM) positivity rate was still 19% in the Dutch TME trial. Later on, the MRC CR07 trial reported a CRM positivity of 11%, likely due to increased use of preoperative MRI and better surgical quality.3 Full use of preoperative MRI and improved surgical quality has been associated with further reduction in CRM positivity during the years that followed.4,5

Registry data revealed 80% overall neoadjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy (n[C]RT) use for rectal cancer between 2009 and 2013 in the Netherlands, the highest rate among European countries.6 It was acknowledged that implementation of the Dutch TME trial as a guideline for the use of nSCRT was associated with overtreatment and additional toxic effects, which were followed by revised guideline recommendations in 2014. Limiting the indication for nSCRT in primary resectable rectal cancer in an evidence-based way appeared to be difficult, because new randomized clinical trials that incorporated preoperative MRI and optimized surgery were not available. Updated recommendations in 2014 were mainly based on cohort studies that showed safe oncological outcomes for surgery alone in MRI-defined low-risk rectal cancer (cT1-3 tumors with ≤5 mm of extramural invasion and >1 mm of distance from the mesorectal fascia [cMRF−]).7

This comparative cross-sectional population-based study aimed to analyze the association of decreased use of n(C)RT after guideline revision with long-term outcomes in nonlocally advanced rectal cancer at a national level in 2 cohorts of registered patients in 2011 and 2016, with LR and overall survival (OS) as main outcome parameters.

Methods

This study combined 2 large collaborative research projects that were performed by the Dutch Snapshot Research Group. The first Snapshot project consisted of a cross-sectional population-based cohort study with data collection between May and October 2015 of all patients who underwent surgical resection for rectal cancer between January 1 and December 31, 2011, in the Netherlands, resulting in a follow-up period of 4 years.4 In the second Snapshot project, an identical study design was applied, with data collection between October 2020 and November 2021, of patients who underwent rectal cancer resection between January 1 and December 31, 2016. Patients were identified using the Dutch Colorectal Audit,8 a mandatory registry that collects procedural and 90 days postoperative outcome data of all patients undergoing resection of primary colorectal cancer.

This study was performed and reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. The protocol of the first Snapshot project was approved by the medical ethical committee of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam on May 14, 2014. The protocol of the second Snapshot study was approved by the medical ethical committee of the Free University Medical Center in Amsterdam on June 30, 2020. The Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act was not applicable. The local institutional review board of each participating center decided whether patients were asked to provide informed consent or were given the opportunity to opt out.

Detailed diagnostic and treatment information and long-term surgical and oncological outcomes were collected from the original electronic patient files by local collaborators. The Snapshot data sets were merged with the originally collected data of the Dutch Colorectal Audit by Medical Research Data Management (Deventer, the Netherlands) and anonymized.9 Important data items were collected again for verification. After a 3-month period of data collection, the anonymized data were checked for discrepancies and missing values, and these were communicated to the collaborators by Medical Research Data Management to adjust and complete the data.

Study Population

For the purpose of the present analysis, patients who underwent rectal resection for nonlocally advanced rectal cancer defined as cT1-3N0-1M0 cMRF− according to the Dutch guideline, as determined on MRI, were selected from the Snapshot cohorts. Patients treated according to a watch-and-wait policy or who were undergoing a local excision or resection for regrowth were excluded. If distance to the cMRF was missing, these tumors were classified as cMRF−. For the 2016 cohort, the cT3N0-1 tumors were rereviewed by local radiologists to classify the location of the tumor according to the LOREC definition (low rectal cancer defined as lower border of the tumor below the origin of the levator muscles on the pelvic sidewall) for subgroup analysis.10 eTable 1 in Supplement 1 displays the differences in the Dutch colorectal guideline recommendations for 2011 and 2016.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were 4-year LR and OS rates. Secondary outcomes included 4-year distant recurrence (DR), 4-year disease-free survival (DFS), cancer-related mortality, non–cancer-related mortality, pelvic sepsis, and permanent stoma rate. The starting point was the date of surgery. Disease-free survival was defined as time from surgery until first event of either LR, DR, or death. Metachronous DR was defined as metastases diagnosed at least 3 months after the rectal resection. Pelvic sepsis was defined as an anastomotic leakage or a presacral abscess diagnosed at any time during follow-up after restorative and nonrestorative rectal resection. A permanent stoma was defined as presence of any stoma for fecal diversion at the end of follow-up, thereby censoring patients with follow-up of less than 1 year.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed for both cohorts and for subgroups based on n(C)RT: 2011 n(C)RT−, 2011 n(C)RT+, 2016 n(C)RT−, and 2016 n(C)RT+. The use of n(C)RT was then stratified for tumor stage across the 2 cohorts: cT1-3N0 and cT1-3N1 to determine the numbers needed to treat (NNT) to prevent 1 LR. Patient characteristics are presented as means (SDs) or medians (IQRs) for continuous variables and as numbers with percentages for categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared with the independent samples t test or Mann-Whitney U test and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to determine recurrence and survival probabilities and the log-rank test for subgroup comparisons. Competing risk analyses were performed, with death as competing risk for LR and DR. The LR and DR were not competing risks of each other because both end points were scored separately. Univariable Cox regression analyses were used to assess the association of known prognostic factors and the proportional hazard assumption was tested for each factor. Expected relevant confounders were included in the multivariable analysis using backward selection. Potential interaction between n(C)RT and tumor height, pT stage, pN stage, and type of resection were tested and included in the multivariable analysis when significantly associated. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS, 28.0 Statistics (IBM).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

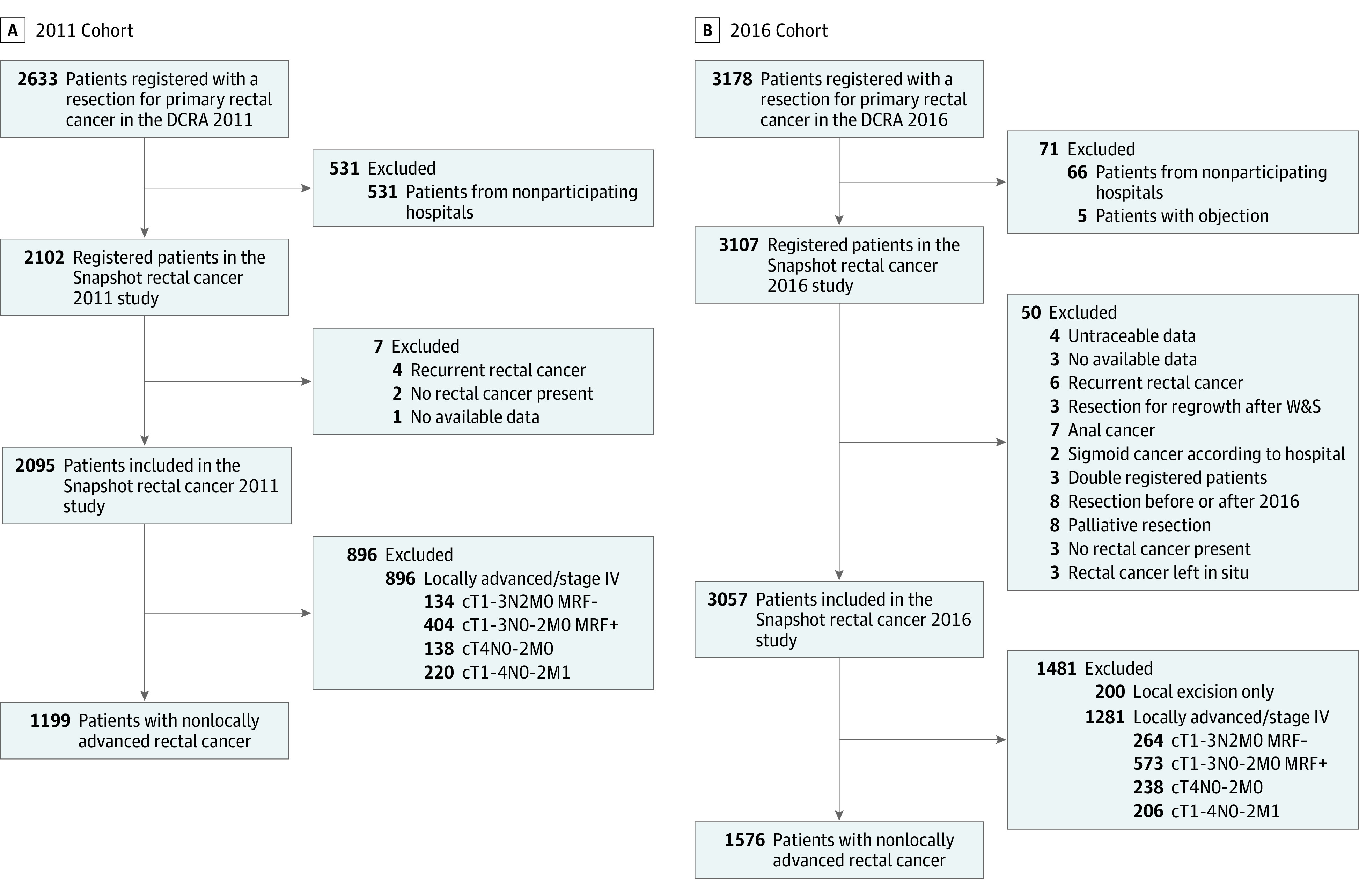

In 2011, 71 of 94 Dutch hospitals (75.5%) performing rectal cancer surgery participated, resulting in registration of 2102 of the 2633 eligible patients (79.8%). In 2016, 67 of 69 hospitals (97.1%) performing rectal cancer surgery participated, resulting in registration of 3107 of 3178 eligible patients (97.8%). Respectively, 1199 and 1576 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria of the current study (Figure 1). Median follow-up was 42 months (IQR, 32-47) and 50 months (IQR, 41-55), respectively. There was no significant difference in age, sex, and American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) classification (Table 1). Fewer patients had cN1 stage in 2016 (386 [40%] vs 531 [36%]). Use of n(C)RT decreased from 87% to 37%. The type of resection was more often sphincter preserving and restorative in 2016. The open surgical approach declined from 648 (56%) to 167 (11%).

Figure 1. Inclusion Flowchart.

DCRA indicates Dutch Colorectal Audit; W&S, wait and see.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics, Treatment, and Pathological Results for the 2011 and 2016 Cohorts.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 cohort (n = 1199) | 2016 cohort (n = 1576) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 68 (11) | 68 (10) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 430 (36) | 547 (35) |

| Male | 768 (64) | 1029 (65) |

| Missing | 1 (0) | 0 |

| ASA score | ||

| I/II | 959 (82) | 1296 (83) |

| III/IV | 212 (18) | 261 (17) |

| Missing | 28 (2) | 19 (1) |

| MRI performed | 1049 (89) | 1480 (94) |

| Missing | 23 (2) | 0 |

| cT stage | ||

| cT1/T2 | 463 (46) | 721 (50) |

| cT3 | 541 (54) | 735 (50) |

| cTx | 195 (16) | 119 (21) |

| cN stage | ||

| cN0 | 572 (60) | 942 (64) |

| cN1 | 386 (40) | 531 (36) |

| cNx | 241 (20) | 103 (7) |

| cTN stage | ||

| cT1-2N0 | 323 (27) | 570 (36) |

| cT3N0 | 230 (19) | 352 (22) |

| cTxN0 | 19 (2) | 20 (1) |

| cT1-2N1 | 116 (10) | 148 (9) |

| cT3N1 | 260 (22) | 382 (24) |

| cT3Nx | 10 (1) | 1 (0) |

| cT1-2Nx | 24 (2) | 3 (0) |

| cT3Nx | 51 (4) | 2 (0) |

| cTxNx | 166 (14) | 98 (6) |

| Distance ARJ in cm, mean (SD)a | 7 (4) | 6 (4) |

| Missing | 335 (28) | 178 (11) |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | ||

| None | 161 (13) | 993 (63) |

| 5 × 5 Short interval | 654 (55) | 384 (24) |

| 5 × 5 Long interval | 56 (5) | 77 (5) |

| 5 × 5 + Systemic therapy | 0 | 10 (1) |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 236 (20) | 109 (7) |

| Systemic therapy only | 0 | 1 (0) |

| Other/unknown course | 92 (8) | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (0) |

| Type of resection | ||

| (L)AR | 645 (54) | 1075 (68) |

| APR | 280 (23) | 249 (16) |

| HP | 230 (19) | 182 (12) |

| Local excision + (L)AR | 12 (1) | 42 (3) |

| Local excision + APR | 15 (1) | 20 (1) |

| Proctocolectomy | 17 (1) | 8 (1) |

| Approach | ||

| Open | 648 (56) | 167 (11) |

| Minimally invasiveb | 519 (44) | 1409 (89) |

| Missing | 32 (3) | 0 |

| (y)pT stage | ||

| (y)pT0 | 54 (5) | 47 (3) |

| (y)pT1 | 110 (10) | 274 (18) |

| (y)pT2 | 456 (40) | 610 (39) |

| (y)pT3 | 498 (44) | 618 (39) |

| (y)pT4 | 22 (2) | 25 (2) |

| (y)pTx | 59 (5) | 2 (0) |

| (y)pN stage | ||

| (y)pN0 | 768 (67) | 1084 (69) |

| (y)pN1 | 295 (26) | 365 (23) |

| (y)pN2 | 81 (7) | 125 (8) |

| (y)pNx | 55 (5) | 2 (0) |

| Resection margin | ||

| R0 | 1120 (98) | 1516 (96) |

| R+ | 28 (2) | 58 (4) |

| Unknown | 51 (4) | 2 (0) |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||

| No | 1067 (90) | 1536 (98) |

| Yes | 119 (10) | 40 (3) |

| Missing | 13 (1) | 0 |

| Pelvic sepsis | ||

| No | 933 (82) | 1346 (86) |

| Yes | 199 (18) | 222 (14) |

| Missing | 67 (6) | 8 (1) |

Abbreviations: APR, abdominoperineal resection; ARJ, anorectal junction; ASA, American Society of Anaesthesiologists; HP, Hartmann procedure (rectal stump with end colostomy); (L)AR, (low) anterior resection; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TME, total mesorectal resection.

Either APR or LAR.

Laparoscopic, robotic, or transanal TME approach.

Long-Term Outcomes per Cohort

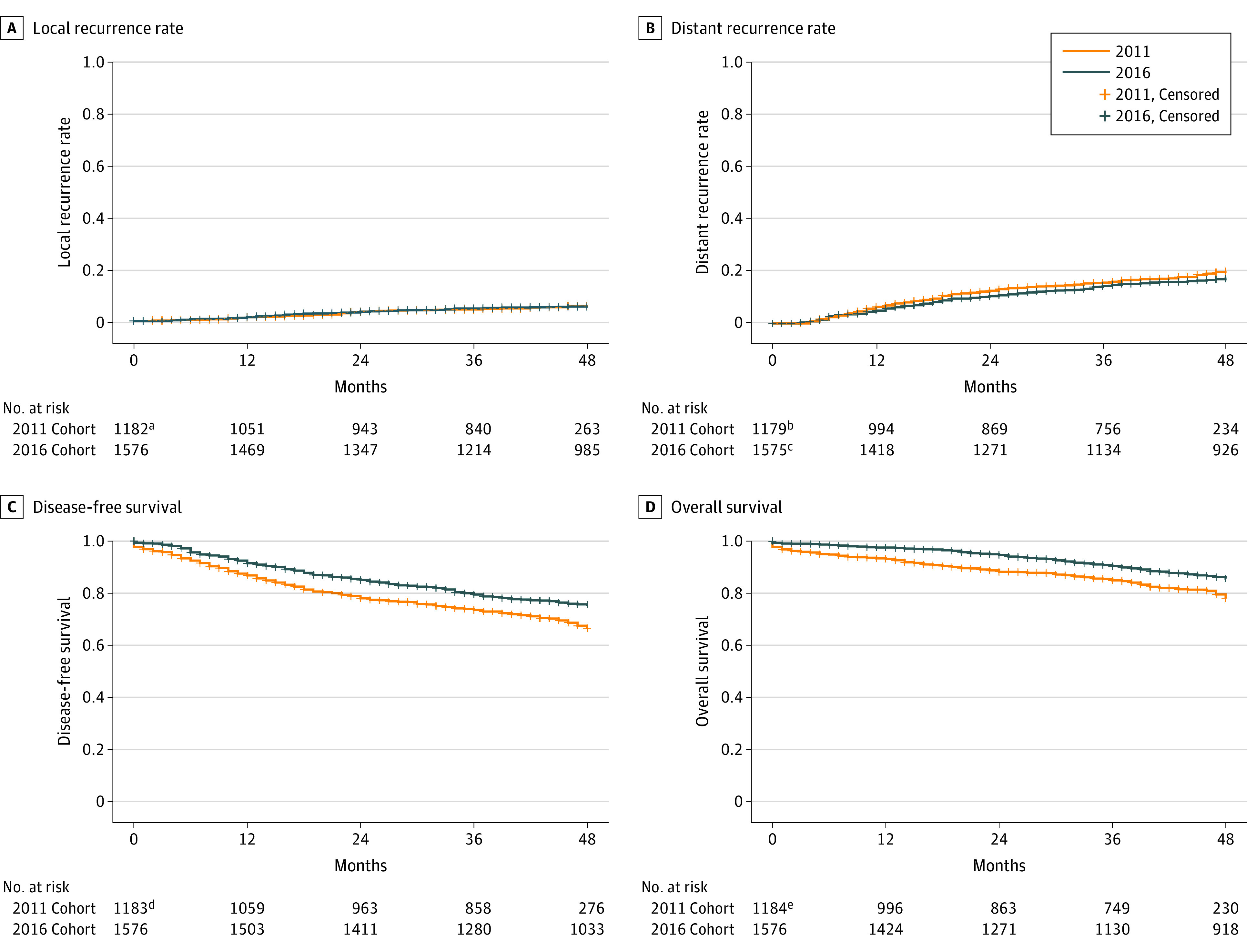

The 4-year LR rate remained similar (5.8% vs 5.5%; P = .99) (Figure 2). The 4-year OS rate increased from 79.6% to 86.4% (P < .001). There was no significant difference in cancer-related mortality (7.6% vs 8.0%; P = .74). Non–cancer-related mortality was higher for the 2011 cohort (13.8% vs 6.3%; P < .001). The 4-year DR rate was not significantly different (19.5% vs 16.8%; P = .11), while the 4-year DFS rate was lower for patients treated in 2011 (67.5% vs 75.7%; P < .001).

Figure 2. Local and Distant Recurrence Rates and Disease-Free and Overall Survival.

A, Hazard ratio (HR), 1.01 (95% CI, 0.94-1.08; P = .76). B, HR, 0.99 (95% CI, 0.95-1.02; P = .45). C, HR, 0.71 (95% CI, 0.61-0.82; P < .001). D, HR, 0.61 (95% CI, 0.51-0.74; P < .001). The presented HR is the adjusted HR after competing risk analyses, with death as competing risk.

aData were missing for 17 patients in the 2011 cohort for the end point of local recurrence.

bData were missing for 20 patients in the 2011 cohort for the end point of distant recurrence.

cData were missing for 1 patient in the 2016 cohort for the end point of distant recurrence.

dData were missing for 16 patients in the 2011 cohort for the end point of overall survival.

eData were missing for 15 patients in the 2011 cohort for the end point of disease-free survival.

Baseline Characteristics as Stratified by n(C)RT

Patients in the 2011 n(C)RT− group were older (age 71 vs 67 years) and had a higher ASA classification (43 [28%] vs 169 [17%] ASA score of III/IV) than patients in the 2011 n(C)RT+ group (Table 2). There was no difference in ASA classification between the 2016 n(C)RT− group and 2016 n(C)RT+ group. Within the 2011 cohort, the n(C)RT− group had a lower cT stage and cN stage compared with the (C)RT+ group. The differences in tumor stage increased in the 2016 cohort, with lower stages in the 2016-n(C)RT− group.

Table 2. Baseline Characteristics, Treatment, and Pathological Results for the 2011 and 2016 Cohorts as Stratified by Use of Neoadjuvant (Chemo)radiotherapy.

| Characteristic | Cohort 2011 | Cohort 2016 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n(C)RT- (n = 161) | n(C)RT+ (n = 1038) | n(C)RT- (n = 994) | n(C)RT+ (n = 582) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 71 (12) | 67 (11) | 68 (10) | 67 (9) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 58 (36) | 372 (36) | 359 (36) | 188 (32) |

| Male | 103 (64) | 665 (64) | 635 (64) | 394 (68) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| ASA score | ||||

| ASA I/II | 112 (73) | 847 (83) | 810 (83) | 486 (85) |

| ASA III/IV | 43 (28) | 169 (17) | 172 (18) | 89 (16) |

| Missing | 6 (4) | 21 (2) | 12 (1) | 7 (1) |

| MRI performed | 102 (67) | 947 (93) | 921 (93) | 559 (96) |

| Missing | 9 (6) | 14 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| cT stage | ||||

| cT1/cT2 | 73 (61) | 390 (44) | 583 (65) | 138 (25) |

| cT3 | 46 (39) | 495 (56) | 317 (35) | 419 (75) |

| cTx/missing | 42 (26) | 152 (15) | 94 (9) | 25 (4) |

| cN stage | ||||

| cN0 | 86 (77) | 486 (57) | 847 (92) | 95 (17) |

| cN1 | 26 (23) | 360 (43) | 71 (8) | 460 (83) |

| cNx/missing | 49 (30) | 191 (18) | 76 (8) | 27 (5) |

| cTN stage | ||||

| cT1-2N0 | 59 (37) | 264 (25) | 551 (55) | 19 (3) |

| cT3N0 | 24 (15) | 206 (20) | 276 (28) | 76 (13) |

| cTxN0 | 3 (2) | 16 (2) | 20 (2) | 0 |

| cT1-2N1 | 9 (6) | 107 (10) | 30 (3) | 118 (20) |

| cT3N1 | 17 (11) | 243 (23) | 41 (4) | 341 (59) |

| cTxN1 | 0 | 10 (1) | 0 | 1 (0) |

| cT1-2Nx | 5 (3) | 19 (2) | 2 (0) | 1 (0) |

| cT3Nx | 5 (3) | 46 (4) | 0 | 2 (0) |

| cTxNx | 39 (24) | 127 (12) | 74 (7) | 24 (4) |

| Distance from ARJ in cm, mean (SD)a | 9 (5) | 6 (4) | 6 (4) | 5 (3) |

| Missing | 85 (53) | 249 (24) | 139 (14) | 40 (7) |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | ||||

| None | 161 (100) | 0 | 993 (100) | 0 |

| 5 × 5 Short interval (surgery ≤2 wk) | 0 | 654 (63) | 0 | 385 (66) |

| 5 × 5 Long interval (surgery >2 wk) | 0 | 56 (5) | 0 | 78 (13) |

| 5 × 5 + Systemic therapy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 (2) |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 0 | 236 (23) | 0 | 109 (19) |

| Systemic therapy only | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 |

| Other/unknown course | 0 | 92 (9) | 0 | 1 |

| Type of resection | ||||

| (L)AR | 96 (60) | 549 (52) | 691 (70) | 388 (67) |

| APR | 18 (11) | 262 (26) | 129 (13) | 118 (20) |

| HP | 37 (23) | 193 (19) | 108 (11) | 72 (12) |

| Local excision + LAR | 2 (1) | 10 (1) | 40 (4) | 2 (0) |

| Local excision + APR | 2 (1) | 13 (1) | 19 (2) | 1 (0) |

| Proctocolectomy | 6 (4) | 11 (1) | 7 (1) | 1 (0) |

| Approach | ||||

| Open | 108 (70) | 540 (53) | 97 (10) | 70 (12) |

| Minimally invasiveb | 46 (30) | 473 (47) | 897 (90) | 512 (88) |

| Missing | 7 (4) | 25 (2) | 4 (0) | 0 |

| (y)pT stage | ||||

| (y)pT0 | 1 (1) | 53 (5) | 7 (1) | 40 (7) |

| (y)pT1 | 22 (15) | 88 (9) | 212 (21) | 62 (11) |

| (y)pT2 | 47 (31) | 409 (41) | 422 (43) | 188 (32) |

| (y)pT3 | 74 (49) | 424 (43) | 335 (34) | 283 (49) |

| (y)pT4 | 7 (5) | 15 (2) | 17 (2) | 8 (1) |

| (y)pTx/unknown | 6 (4) | 49 (5) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| (y)pN stage | ||||

| (y)pN0 | 93 (60) | 675 (67) | 722 (73) | 362 (62) |

| (y)pN1 | 42 (27) | 253 (25) | 202 (20) | 163 (28) |

| (y)pN2 | 17 (11) | 64 (6) | 68 (7) | 57 (10) |

| (y)pNx/unknown | 9 (6) | 46 (4) | 2 (0) | 0 |

| Resection margin | ||||

| R0 | 144 (95) | 976 (98) | 963 (97) | 553 (95) |

| R+ | 8 (5) | 20 (2) | 29 (3) | 29 (5) |

| Unknown | 9 (6) | 42 (4) | 2 (0) | 0 |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| No | 130 (83) | 937 (91) | 962 (97) | 574 (99) |

| Yes | 26 (17) | 93 (9) | 32 (3) | 8 (1) |

| Missing | 5 (3) | 8 (1) | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviations: APR, abdominoperineal resection; ARJ, anorectal junction; ASA, American Society of Anaesthesiologists; HP, Hartmann procedure (rectal stump with end colostomy); (L)AR, (low) anterior resection; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; n(C)RT, neoadjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy; TME, total mesorectal resection.

Either APR or LAR.

Laparoscopic, robotic, or transanal TME approach.

Long-Term Outcomes as Stratified by n(C)RT

Oncological and survival outcomes are shown in eFigures 1 and 2 in Supplement 1. Multivariable analyses of the 2011 cohort revealed that n(C)RT was associated with a decreased risk of LR (hazard ratio [HR], 0.427; 95% CI, 0.218-0.839; P = .01), but not with OS (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). In the 2016 cohort, n(C)RT was still associated with a decrease in the LR rate (HR, 0.409; 95% CI, 0.240-0.698; P < .001) (eTable 3 in Supplement 1), but also with worse OS (HR, 1.418; 95% CI, 1.086-1.852; P = .01). In 2011, the cause of death was more often due to surgical complications and cardiovascular and pulmonary causes, whereas in 2016 this was more often caused by progression of rectal cancer (eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

Pelvic Sepsis and Permanent Stoma

The incidence of pelvic sepsis was 17.6% in the 2011 cohort and 14.2% in the 2016 cohort (P = .02). Within the 2011 cohort, the incidence of pelvic sepsis was lower in the n(C)RT− group (19 [13%] vs 185 [19%] n[C]RT+), although this was not significant (P = .10). There was no difference in permanent stoma rate between both groups in 2011 (39 of 116 [34%] vs 223 of 671 [33%], respectively; P = .94). Within the 2016 cohort, 130 patients (13%) in the n(C)RT− group had pelvic sepsis, as well as 92 patients (16%) in the n(C)RT+ group (P = .14). The permanent stoma rate was significantly lower in the 2016 n(C)RT− group (294 of 938 [31%]) compared with the 2016 n(C)RT+ group (218 of 547 [40%]; P < .001). This difference increased when only analyzing patients with high (non-LOREC) cT3 tumors (43 of 223 [19%] vs 80 of 264 [30%]; P = .01).

Radiotherapy as Stratified for Tumor Stage

A total of 1468 patients had cT1-3N0 rectal cancer, of whom 560 patients (38.1%) received n(C)RT. Treatment with n(C)RT had no significant association with the risk of LR in this subgroup (HR, 0.750; 95% CI, 0.469-1.198; P = .23) and the NNT would be 67 patients (LR rate, 5.4% n(C)RT+ vs 6.9% n(C)RT−). A total of 901 patients had cT1-3N1 rectal cancer, and 805 patients (89.3%) received n(C)RT. In this subgroup, n(C)RT was not significantly associated with a decrease in LR (HR, 0.467; 95% CI, 0.199-1.051; P = .07). The NNT would be 19 patients (LR rate, 3.6% n(C)RT+ vs 8.8% n(C)RT−).

Discussion

This comparative cross-sectional study evaluated the long-term associations of the decreased use of n(C)RT in nonlocally advanced rectal cancer in the Netherlands after guideline revision based on nationwide 2011 and 2016 cohorts. Despite the absolute 50% reduction in n(C)RT, there was no increase in LR. An improvement in OS in the 2016 cohort compared with the 2011 cohort was observed, with lower non–cancer-related mortality. The selection for n(C)RT was different in the 2 cohorts: in 2011, n(C)RT was mainly withheld in elderly individuals with frailty, which explains the lower OS in the upfront surgery group, while in 2016, n(C)RT was applied according to risk stratification based on tumor and nodal stage.

There are noticeable differences in the indication for n(C)RT for rectal cancer in the international guidelines. The current Dutch guideline advises to consider nSCRT for cT3cdN0 (>5 mm extramural invasion) or cT1-3N1 within a shared decision-making process and strongly recommends nCRT in patients with cT4b, cN2, MRF+, or enlarged lateral lymph nodes. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) and the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons guidelines recommend n(C)RT for cT3-T4 and/or cN+ rectal tumors.11,12 The European Society for Medical Oncology guideline13 defines tumors that are cT3a/b (≤5 mm extramural invasion), cN1-2, cMRF−, absence of extramural vascular invasion (EMVI−), and located very low (distance not defined) as intermediate disease. Total mesorectal excision alone is advised for these tumors, unless good-quality mesorectal excision cannot be assured, in which case nSCRT/nCRT is advised. This variety in guidelines underlines the need for more evidence regarding optimal patient selection for n(C)RT.

Functional outcomes are playing an increasing role in the shared decision-making for treating rectal cancer. Treatment with n(C)RT is associated with a higher risk of complications3,14,15 and worse functional outcomes16,17 and is a predictor for nonreversal of a stoma.18 After a median follow-up of 5 years, more incontinence (62% vs 38%) and lower satisfaction with bowel function with a greater effect on daily activities was found in the nSCRT group of the Dutch TME trial.17 After 14 years, the nSCRT+ TME patient group reported more bowel dysfunction.16 In the present cohort, patients with a high (non-LOREC) cT3 tumor who underwent n(C)RT had more often a permanent stoma compared with upfront TME surgery (30% vs 19%). Therefore, avoiding n(C)RT in patients without clear oncological benefit will potentially lower the risk of long-term adverse effects.

This study suggested that the omission of n(C)RT in low-risk patients (cT1-3N0, MRF−) was oncologically safe. Most patients with an intermediate-risk tumor (cT1-3N1 MRF−) still received n(C)RT in 2016; therefore, the association of omission of n(C)RT in this patient group could less reliably be analyzed. There is still controversy whether patients with a cT1-3N1 MRF− rectal tumor should receive n(C)RT if there is no intention for organ preservation in the higher tumors, especially since the clinical suspicion of nodal involvement based on imaging remains inaccurate and has limited prognostic relevance.7,19,20,21,22,23,24 The MERCURY study showed that the assessment of the CRM via magnetic resonance imaging by trained radiologists is superior to the TNM-based criteria in predicting LR, DFS, and OS.7,25 Furthermore, patients with tumors with good prognostic features (cT2-3ab CRM− mrEMVI− tumors, regardless of cN-stage) could be safely treated with surgery alone, resulting in a 3% LR rate. Several studies thereafter confirmed that upfront TME surgery was associated with similarly low LR rates compared with n(C)RT as long as the MRF is free,26,27,28,29,30,31 although this might be debated for the distal tumors based on the OCUM trial.32

The recently published randomized PROSPECT clinical trial showed that neoadjuvant treatment with FOLFOX (and selective nCRT) was noninferior to nCRT (5-year DFS, 80.8% vs 78.6%).33 Patients with cT2N+, cT3N0, or cT3N+ rectal cancer and candidates for sphincter-saving surgery were included; exclusion criteria were a less than 3-mm distance to the radial margin or 4 or more pelvic lymph nodes with a more than 10-mm short axis. The 5-year LR rates were remarkably low (1.8% vs 1.6%) compared with our and other studies and might be explained by the inclusion of patients with relatively small and proximal tumors. Most of these patients would have been treated with upfront surgery according the European guidelines. It is possible that many of the patients in both study arms were overtreated, especially considering the high-grade 3 or greater adverse events that occurred in 41% in the FOLFOX group and 22.8% in the nCRT group.

There was an evident improvement observed in 4-year OS of 6.8% between 2011 and 2016. The most noticeable changes between 2011 and 2016 were the decreased use of n(C)RT, implementation of minimally invasive surgery, and more sphincter-sparing surgery. Whether the omission of n(C)RT has contributed to the improvement in OS is difficult to determine due to the heterogeneity between both cohorts and the different indications for n(C)RT. The COLOR234 and COREAN35 trials have failed to show a benefit of laparoscopic surgery regarding OS. Therefore, the increase in laparoscopy is not likely associated with OS in the present study. Other potential changes, which could not be quantified in this study, are associated with clinical staging, radiation target volumes, and changes in perioperative care. Introduction of the population screening program in 2014 likely contributed to improved outcomes; there were 9% more cT1-2N0 tumors in 2016.36 Furthermore, higher-quality MRI and optimized assessment by radiologists has likely been associated with more appropriate patient selection. New radiation techniques, such as intensity modulated radiotherapy and volumetric modulated arc therapy, have been introduced, with increased sparing of surrounding healthy tissue. To our knowledge, an effect of such technical modifications on OS in patients with rectal cancer has not been described, but intensity modulated radiotherapy was associated with fewer grade 3 or greater adverse events in endometrial cancer based on the PORTEC-3 trial.37 Lastly, a significant proportion of the causes of death were unknown, especially in the 2011 cohort, of which a part still could have been oncological mortality.

Limitations

Due to its retrospective nature, this study had several limitations. First, historical comparisons at a population level incorporate multiple changes in the whole clinical management that do not allow for firm conclusions on individual treatment aspects. Second, the depth of extramural invasion of cT3 tumors, presence of mrEMVI, and enlarged lateral lymph nodes were not reported in 2011 and not consistently reported in 2016 and could not be included in the analyses. Less potentially eligible patients were included in 2011 (79.8%) than in 2016 (97.8%). However, our study results suggested that the nonparticipating hospitals in the 2011 cohort had overall worse results than the participating centers, which might have been associated with an even larger difference in OS between the cohorts if those could have been included.4 Registered complications in both cohorts were associated with surgery, and there were no data on adverse effects directly associated with the radiotherapy. Furthermore, the cause of death was missing for many patients in 2011; therefore, the reason for the improvement in OS could not be reliably assessed. The watch-and-wait strategy was incompletely registered and excluded from the present study, although this was infrequently applied at that time in the Netherlands. Guideline recommendations changed between the cohorts regarding MRI-based nodal staging. Criteria for lymph node involvement were broader in 2011, which was probably associated with more overstaging compared with 2016. Again, this might even have attenuated the observed differences. Finally, because of multiple statistical testing, there is a possibility of inflation of type 1 error rate.

Conclusions

After the Dutch revised colorectal cancer guideline was published in 2014 with a stricter indication for nSCRT for nonlocally advanced rectal cancer, the overall LR rate at a national level remained unchanged. In 2011, n(C)RT was mainly withheld in elderly individuals with frailty, while n(C)RT was more applied according to risk stratification based on MRI staging in 2016. There was an increase in OS over the years, which is likely to be multifactorial.

eTable 1. Overview of guideline differences

eFigure 1. A) Local Recurrence Rate, (B) Distant Recurrence Rate, (C) Disease-Free Survival, (D) Overall Survival for cohort 2011, stratified for neoadjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy

eFigure 2. (A) Local Recurrence Rate, (B) Distant Recurrence Rate, (C) Disease-Free Survival, (D) Overall Survival for cohort 2016, stratified for neoadjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy

eTable 2. Univariate and multivariable analyses for Locoregional Recurrence and Overall Survival in cohort 2011

eTable 3. Univariate and multivariable analyses for Locoregional Recurrence and Overall Survival in cohort 2016

eTable 4. Causes of death per cohort and use of n(C)RT

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.van Gijn W, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. ; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group . Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer: 12-year follow-up of the multicentre, randomised controlled TME trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(6):575-582. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70097-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sebag-Montefiore D, Stephens RJ, Steele R, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy versus selective postoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer (MRC CR07 and NCIC-CTG C016): a multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9666):811-820. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60484-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marijnen CA, Kapiteijn E, van de Velde CJ, et al. ; Cooperative Investigators of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group . Acute side effects and complications after short-term preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision in primary rectal cancer: report of a multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(3):817-825. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutch Snapshot Research Group . Benchmarking recent national practice in rectal cancer treatment with landmark randomized controlled trials. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19(6):O219-O231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gietelink L, Wouters MW, Tanis PJ, et al. ; Dutch Surgical Colorectal Cancer Audit Group . Reduced circumferential resection margin involvement in rectal cancer surgery: results of the Dutch Surgical Colorectal Audit. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(9):1111-1119. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gietelink L, Wouters MWJM, Marijnen CAM, et al. ; Dutch Surgical Colorectal Cancer Audit Group . Changes in nationwide use of preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer after revision of the national colorectal cancer guideline. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(7):1297-1303. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor FG, Quirke P, Heald RJ, et al. ; MERCURY Study Group . Preoperative high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging can identify good prognosis stage I, II, and III rectal cancer best managed by surgery alone: a prospective, multicenter, European study. Ann Surg. 2011;253(4):711-719. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31820b8d52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Leersum NJ, Snijders HS, Henneman D, et al. ; Dutch Surgical Colorectal Cancer Audit Group . The Dutch surgical colorectal audit. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39(10):1063-1070. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hazen SJA, Sluckin TC, Horsthuis K, et al. ; Dutch Snapshot Research Group . Evaluation of the implementation of the sigmoid take-off landmark in the Netherlands. Colorectal Dis. 2022;24(3):292-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moran BJ, Holm T, Brannagan G, et al. The English national low rectal cancer development programme: key messages and future perspectives. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16(3):173-178. doi: 10.1111/codi.12501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Guidelines: Colorectal Cancer. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.You YN, Hardiman KM, Bafford A, et al. ; Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons . The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons clinical practice guidelines for the management of rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(9):1191-1222. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee . Rectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl 4):iv263. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borstlap WAA, Westerduin E, Aukema TS, Bemelman WA, Tanis PJ; Dutch Snapshot Research Group . Anastomotic leakage and chronic presacral sinus formation after low anterior resection: results from a large cross-sectional study. Ann Surg. 2017;266(5):870-877. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birgisson H, Påhlman L, Gunnarsson U, Glimelius B; Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial Group . Adverse effects of preoperative radiation therapy for rectal cancer: long-term follow-up of the Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8697-8705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen TY, Wiltink LM, Nout RA, et al. Bowel function 14 years after preoperative short-course radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: report of a multicenter randomized trial. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2015;14(2):106-114. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peeters KC, van de Velde CJ, Leer JW, et al. Late side effects of short-course preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: increased bowel dysfunction in irradiated patients–a Dutch colorectal cancer group study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6199-6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.den Dulk M, Smit M, Peeters KC, et al. ; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group . A multivariate analysis of limiting factors for stoma reversal in patients with rectal cancer entered into the total mesorectal excision (TME) trial: a retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(4):297-303. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70047-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JH, Beets GL, Kim MJ, Kessels AG, Beets-Tan RG. High-resolution MR imaging for nodal staging in rectal cancer: are there any criteria in addition to the size? Eur J Radiol. 2004;52(1):78-83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown G, Richards CJ, Bourne MW, et al. Morphologic predictors of lymph node status in rectal cancer with use of high-spatial-resolution MR imaging with histopathologic comparison. Radiology. 2003;227(2):371-377. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272011747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bipat S, Glas AS, Slors FJ, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. Rectal cancer: local staging and assessment of lymph node involvement with endoluminal US, CT, and MR imaging–a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2004;232(3):773-783. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2323031368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beets-Tan RG, Beets GL, Vliegen RF, et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in prediction of tumour-free resection margin in rectal cancer surgery. Lancet. 2001;357(9255):497-504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04040-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brouwer NPM, Stijns RCH, Lemmens VEPP, et al. Clinical lymph node staging in colorectal cancer; a flip of the coin? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(8):1241-1246. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giesen LJX, Borstlap WAA, Bemelman WA, Tanis PJ, Verhoef C, Olthof PB; Dutch Snapshot Research Group . Effect of understaging on local recurrence of rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2020;122(6):1179-1186. doi: 10.1002/jso.26111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor FG, Quirke P, Heald RJ, et al. ; Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Rectal Cancer European Equivalence Study Group . Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging assessment of circumferential resection margin predicts disease-free survival and local recurrence: 5-year follow-up results of the MERCURY study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(1):34-43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.3258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JC, Yu CS, Lim SB, et al. Re-evaluation of controversial issues in the treatment of cT3N0-2 rectal cancer: a 10-year cohort analysis using propensity-score matching. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(12):2649-2659. doi: 10.1007/s00384-021-04003-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ptok H, Meyer F, Gastinger I, Garlipp B. Multimodal treatment of cT3 rectal cancer in a prospective multi-center observational study: can neoadjuvant chemoradiation be omitted in patients with an MRI-assessed, negative circumferential resection margin? Visc Med. 2021;37(5):410-417. doi: 10.1159/000514800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto T, Kawada K, Matsusue R, et al. Identification of patient subgroups with low risk of postoperative local recurrence for whom total mesorectal excision surgery alone is sufficient: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2022;37(10):2207-2218. doi: 10.1007/s00384-022-04255-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, Sun Y, Xu Z, Chi P, Lu X. Is neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy always necessary for mid/high local advanced rectal cancer: a comparative analysis after propensity score matching. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(8):1440-1446. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng X, Liu P, Jiang D, et al. Neoadjuvant radiotherapy versus surgery alone for stage II/III mid-low rectal cancer with or without high-risk factors: a prospective multicenter stratified randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2020;272(6):1060-1069. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lord AC, Corr A, Chandramohan A, et al. Assessment of the 2020 NICE criteria for preoperative radiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer treated by surgery alone in comparison with proven MRI prognostic factors: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(6):793-801. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00214-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruppert R, Kube R, Strassburg J, et al. ; OCUM Group . Avoidance of overtreatment of rectal cancer by selective chemoradiotherapy: results of the optimized surgery and MRI-based multimodal therapy trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231(4):413-425.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schrag D, Shi Q, Weiser MR, et al. Preoperative treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(4):322-334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2303269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Abis GA, et al. ; COLOR II Study Group . A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1324-1332. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park JW, Kang SB, Hao J, et al. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid or low rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): 10-year follow-up of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(7):569-577. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00094-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Neree Tot Babberich MPM, Vermeer NCA, Wouters MWJM, et al. ; Dutch ColoRectal Audit . Postoperative outcomes of screen-detected vs non–screen-detected colorectal cancer in the Netherlands. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(12):e183567. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.3567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wortman BG, Post CCB, Powell ME, et al. Radiation therapy techniques and treatment-related toxicity in the PORTEC-3 trial: comparison of 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy versus intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;112(2):390-399. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Overview of guideline differences

eFigure 1. A) Local Recurrence Rate, (B) Distant Recurrence Rate, (C) Disease-Free Survival, (D) Overall Survival for cohort 2011, stratified for neoadjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy

eFigure 2. (A) Local Recurrence Rate, (B) Distant Recurrence Rate, (C) Disease-Free Survival, (D) Overall Survival for cohort 2016, stratified for neoadjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy

eTable 2. Univariate and multivariable analyses for Locoregional Recurrence and Overall Survival in cohort 2011

eTable 3. Univariate and multivariable analyses for Locoregional Recurrence and Overall Survival in cohort 2016

eTable 4. Causes of death per cohort and use of n(C)RT

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement