Abstract

A DNA fragment conferring resistance to zinc and cobalt ions was isolated from a genomic DNA library of Staphylococcus aureus RN450. The DNA sequence analysis revealed two consecutive open reading frames, designated zntR and zntA. The predicted ZntR and ZntA showed significant homology to members of ArsR and cation diffusion families, respectively. A mutant strain containing the null allele of zntA was more sensitive to zinc and cobalt ions than was the parent strain. The metal-sensitive phenotype of the mutant was complemented by a 2.9-kb DNA fragment containing zntR and zntA. An S. aureus strain harboring multiple copies of zntR and zntA showed an increased resistance to zinc. The resistance to zinc in the wild-type strain was inducible. Transcriptional analysis indicated that zntR and zntA genes were cotranscribed. The zinc uptake studies suggested that the zntA product was involved in the export of zinc ions out of cells.

The trace heavy metal ions such as cobalt, zinc, copper, and nickel play important roles in bacteria. They regulate a wide array of metabolic functions as coenzymes or cofactors, as catalysts or Lewis acid in enzymes, and as structural stabilizers of enzymes and DNA-binding proteins (9, 18). However, these trace heavy metal ions are toxic in excess of normal physiological levels (28). Increasing environmental concentrations of these heavy metals pose a challenge to bacteria. Therefore, bacteria have evolved mechanisms to regulate the influx and efflux processes to maintain the relatively steady intracellular level of the heavy metal ions. Different molecular mechanisms have been reported that are responsible for resistance to various trace heavy metal ions in bacteria (2, 8, 13, 18, 22, 23, 27). The molecular mechanisms involve a number of proteins, such as ion transporters, reductases, glutathione-related cadystins and cysteine-rich metallothioneins, and low-molecular-weight cysteine-rich metal ligands (27). These protein molecules either export the metal ions out of cells or detoxify or sequester them so that the cells can grow in an environment containing high levels of toxic metals. However, there is no common mechanism of resistance to all heavy metal ions. In bacteria, the genes encoding resistance to heavy metals are located either on the bacterial chromosome, on the plasmids, or on both (18, 27).

Staphylococcus aureus is a common human pathogen associated with a number of diseases. Understanding of metal resistance in staphylococci has progressed rapidly in the past 10 years, with well-established cadmium, mercury, antimony, and arsenic resistance systems encoded by plasmids (20, 25, 27). However, staphylococcal strains without plasmids show resistance to heavy metal ions, such as zinc and cobalt. This implies that a plasmid-independent chromosomal determinant might encode resistance to heavy metals such as zinc and cobalt. Although operons encoding cobalt, zinc, and cadmium in Alcaligenes eutrophus (17) and zinc in Escherichia coli (2) have been investigated, relatively little is known about the transport of and resistance mechanisms to zinc and cobalt ions in S. aureus. Here we report the cloning, sequencing, and genetic analysis of a determinant located on the bacterial chromosome that codes for zinc and cobalt resistance in S. aureus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. aureus strains were grown on tryptic soy agar or broth (TSA or TSB), whereas E. coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar or broth at 37°C with shaking (200 rpm). When necessary for selection, ampicillin (50 μg/ml), kanamycin (30 μg/ml for E. coli, 500 μg/ml for S. aureus), and chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml for E. coli, 10 μg/ml for S. aureus) were added to the media. When required, an appropriate volume of filter-sterilized 0.5 M stock solutions of ZnCl2 or CoCl2 was added to TSB. The biomass in liquid cultures was estimated from the optical density at 580 nm (OD580) with a DU-64 Beckman spectrophotometer. Cell yield was determined from a calibration curve relating OD580 to cell dry weight.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus strains | ||

| NCTC8325-4 | Laboratory strain cured of prophages | 19 |

| RN4220 | NCTC8325-4, r− | 19 |

| RN-MZ | RN4220, rzcB::kan (Kanr) | This work |

| RN-CMZ | RN-MZ containing pCU1-ZC plasmid (Kanr Cmr) | This work |

| RN-ZC | RN4220 containing pCU1-ZC plasmid (Cmr) | This work |

| E. coli JM109 | recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thi Δ(lac-proAB) F′(traD36 proAB+ lacIqZΔ M15) | 31 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTZ18R | Cloning vector for E. coli (Ampr) | 16 |

| pTZ18R-ZC | pTZ18R containing 2.9-kb EcoRI fragment conferring resistance to zinc and cobalt (Ampr) | This work |

| pTZ18R-ZCK | pTZ18R containing 4.4-kb EcoRI fragment with rzcB::kan (Kanr Ampr) | This work |

| pCU1 | Shuttle vector (Ampr Cmr) | 1 |

| pCU1-ZC | pCU1 containing 2.9-kb EcoRI fragment conferring resistance to zinc and cobalt (Ampr Cmr) | This work |

| pBT2 | Shuttle vector carrying temperature-sensitive replicon (Ampr Cmr) | 4 |

| pBT2-ZCK | pBT2 containing 4.4-kb EcoRI fragment with rzcB::kan (Ampr Cmr Kanr) | This work |

| pOSTkan | Containing kanamycin resistance cassette | 11 |

DNA manipulation and sequencing.

All standard methods of DNA manipulation were performed according to the protocols of Novick (19) and Sambrook et al. (26). Genomic DNA of S. aureus was isolated by using DNAzol kits (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio). Plasmid was purified with the QIAgen plasmid minipreparation kit (Qiagen, Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.). PCR-amplified products and DNA fragments from agarose gels were purified with QIAquick gel extraction kits. DNA probes were labeled by using the Rediprime DNA labeling system (Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, Ill.). All DNA restriction and modification enzymes were obtained from Promega (Madison, Wis.) and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA sequences were determined with an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer system (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.). Two pairs of oligonucleotide primers were used for PCR amplification: PCA1 and PCA2 (5′-TAAAGGCGGCGACACTTCACAC-3′ and 5′-CTGGTGGTTTTTGCCCAAATTG-3′) and CAF1 and CAB1 (5′-TTAGATGACATCCACGTAGCAACT-3′ and 5′-GACCAAACAAGTCGCCATAAAGAC-3′). DNA sequences were analyzed by the MacVector (version 5.0) program, and multiple protein alignments were performed by the ClustalW program (29).

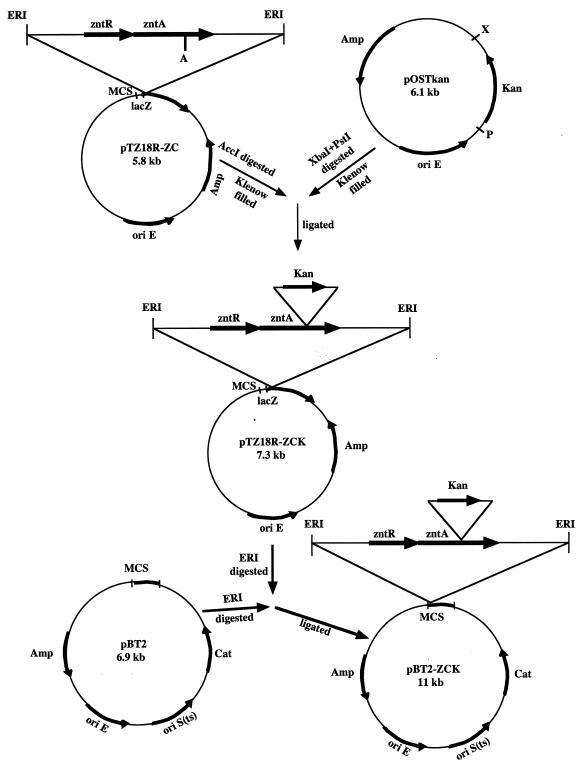

Construction of the zntA mutant and complementation.

The 2.9-kb EcoRI fragment containing zntR and zntA was cloned into vector pTZ18R. The resulting plasmid pTZ18R-ZC (5.8 kb) was digested with SalI and SmaI to remove the AccI site from the multicloning site of the vector and then religated after end filling with Klenow DNA polymerase. The resulting plasmid was digested with AccI to insert a 1.5-kb kanamycin cassette from pOSTkan (11). The EcoRI fragment containing the kanamycin cassette within zntA was then subcloned into the pBT2 shuttle vector that contained a temperature-sensitive staphylococcal origin of replication (4). The resulting plasmid pBT2-ZCK was electroporated into competent S. aureus RN4220 cells. Selection for double-crossover events with the chromosome of S. aureus was carried out at 43°C as described previously (3, 4). One representative mutant was analyzed by Southern blotting in order to exclude possible rearrangement adjacent to the insertion sites or a single crossover event by using the 2.9-kb EcoRI fragment as a probe. The exact insertion site of the kanamycin cassette on the chromosome was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing of the PCR-amplified product with the primers PCA1 and PCA2. To complement the mutation in trans, the 2.9-kb EcoRI fragment containing zntR and zntA was cloned into the pCU1 shuttle vector (1). The resulting plasmid, pCU1-ZC, was electroporated into the mutant strain RN-MZ.

Analysis of zinc ion accumulation.

Zinc concentration was measured as described by Beard et al. (2). Cultures grown overnight were transferred to 40 ml of fresh TSB to give an OD580 of approximately 0.1. When the optical density of cultures came close to 1.0, appropriate amounts of ZnCl2 were added to the cultures to give various final concentrations. The cultures were then incubated for an additional 4 h. Then, 25-ml aliquots of the cultures described above were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 15 min. Cell pellets were washed with 4 ml of TSB and then with 4 ml of 0.1 N HNO3 to remove the surface-bound zinc ions. The intracellular concentrations of zinc were determined with an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Thermo Jarrell Ash Corp., Franklin, Mass.) (2).

Induction of znt transcription.

The wild-type S. aureus strains were grown under the following conditions to evaluate the induction of znt operon in the presence of zinc ions: (i) in TSB without zinc, (ii) in TSB without zinc to mid-log phase and then subcultured (1:100) into TSB containing 1.5 mM zinc; and (iii) in TSB containing 0.5 and 2 mM zinc to mid-log phase and then subcultured (1:100) in TSB containing 1.5 mM zinc. The cells were harvested after 6 h, and the total RNA was isolated with the TRI reagent kit (Molecular Research Center). Then, 10 μg of total RNA from each sample was electrophoresed on formaldehyde agarose gels (1.0%) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were prehybridized for 8 to 12 h and then hybridized overnight with [α-32P]dCTP-labeled znt or kanamycin gene under high-stringency conditions. The membrane was washed and subsequently autoradiographed.

Primer extension.

The primer extension assay was performed by using an oligonucleotide primer of 19 bases (5′-GTAATCGCCTAATGCCTTG-3′) specific to the zntR coding region. The primer (10 ng) and total RNA (10 μg) from wild-type S. aureus were combined in 3 μl of water and boiled for 1 min followed by quick cooling in ice water. The primer extension reaction was carried out in a total volume of 10 μl containing 2 μl of 5× AMV buffer; 2 μl of a 250-μM dATP, dTTP, and dGTP mix; 1 μl of [α-32P]dCTP; 12 U of avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase; and 2 U of RNasin. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Chase solution (3 μl) containing 25-mM concentrations of dGTP, dCTP, dTTP, and dATP was then added, and the mixture was incubated for an additional 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of an equal volume of 98% formamide, 0.3% xylene cyanol, and 0.3% bromophenol blue. Denatured samples (5 μl) were electrophoresed on denaturing polyacrylamide gels. A sequence ladder generated by using the same primer on a 2.9-kb EcoRI fragment was coelectrophoresed and used to determine the position of the transcription start site.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported here has been submitted to GenBank under accession number AF044951.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cloning and sequencing of S. aureus genes encoding zinc and cobalt resistance.

The genomic library of S. aureus RN450 was constructed in the pCU1 shuttle vector (1). S. aureus RN450 was transformed with this pCU1-based S. aureus genomic library by electroporation (19). Approximately 2,000 S. aureus transformants were tested for zinc tolerance by replica plating on TSA medium containing 10 mM ZnCl2. After incubating for 2 days at 37°C, the transformants that showed faster growth were further analyzed. The plasmids isolated from these clones were transformed into S. aureus. DNA from positive transformants yielded resistance to 10 mM ZnCl2, suggesting that zinc resistance was due to a sequence contained on the plasmids. Further restriction analysis and zinc resistance studies indicated that the gene(s) encoding the zinc resistance were located within a 2.9-kb EcoRI fragment that was subsequently subcloned into the pTZ18R vector (16).

The nucleotide sequence of ∼2.0 kb from the 2.9-kb EcoRI fragment revealed two consecutive open reading frames, designated zntR and zntA, of 318 and 978 bp and corresponding to 106 and 326 amino acid residues, respectively. The start codon of zntA is separated from the stop codon of zntR by a single base. The molecular masses of the putative proteins of zntR and zntA were predicted to be 11,987 and 36,230 Da, respectively. Putative Shine-Dalgarno sequences, GAAAGG and AGTGGG, were found upstream of the proposed initiation codons ATG of zntR and zntA, respectively. Also, possible −35 (TTGACA) and −10 (ATTAAT) sequences were identified upstream of zntR. An imperfect 8-2-8 hyphenated inverted repeat (AATATATG-AA-CAAATATT) is located between the −10 region and the site of translation initiation, which represents a potential regulatory site (8). The typical −10 and −35 regions, however, are not present upstream of zntA, a finding consistent with cotranscription of zntR and zntA. Downstream of the stop codon of zntA, there is an inverted repeat, followed by a T-rich region which may function as a transcription termination structure. All of these features suggest that the zntR and zntA were organized in an operon on the S. aureus chromosome. The organization of the znt operon is similar to that of the ars operon, encoding a repressor and a structural gene for antimonite resistance in Staphylococcus xylosus (25).

Analysis of predicted amino acid sequences of ZntR and ZntA.

The predicted ZntR sequence showed 32% identity of amino acid residues with SmtB of Synechococcus (8), 32% identity with CadC of S. aureus (32), 30% identity with ArsR of S. xylosus (25) and S. aureus (10), and 28% identity with ArsR of E. coli (6). All of these homologs are members of the ArsR family (6, 10). ZntR appeared to be a hydrophilic protein, suggesting a cytoplasmic location. The secondary structure and domain analysis of ZntR suggested that there was a consensus DNA-binding helix-turn-helix motif (7), but it lacks the conserved CXC sequence. A putative regulatory region with an inverted repeat was located upstream of zntR, which represented the potential binding site of a regulatory protein (8).

ZntA shared 38% identity with CzcD of A. eutrophus (17), 34% identity with zinc and cobalt resistance genes of yeast (5, 12) and 29% identity with ZnT1 of mice (22). The ZntA protein was predicted to have six transmembrane domains and a long hydrophilic C-terminal tail as reported for CzcD and other members of the cation diffusion family (23). ZntA had two histidine-rich regions, one at the C terminus (10 of 17 amino acids) and the other near the N terminus (8 of 12 amino acids). Similar histidine-rich regions have been reported for zinc and cobalt transporters which are thought to be the domains for binding the zinc ions (5, 12, 18). However, the CzcD of A. eutrophus, which functions as the sensor of a two-component regulatory system of cadmium, zinc, and cobalt, lacked any histidine-rich region (13). Also, in contrast to most bacterial transporters of heavy metal ions, the ZntA protein lacked the conserved CXXC motif for metal binding and had relatively low levels of cysteine residues (1.2%).

Construction of a zntA null mutant and complementation analysis.

The mutation of zntA was achieved to test our hypothesis whether this operon is responsible for zinc and cobalt resistance. The mutant strain RN-MZ was created by the insertion of the kanamycin cassette at the AccI site of the zntA gene (Fig. 1). Insertion of the ∼1.5-kb kanamycin cassette increased the size of the hybridizing EcoRI fragment from ∼4.3 kb in the parent to ∼5.8 kb in the mutant RN-MZ (data not shown). The PCR analysis with primers PCA1 and PCA2 spanning the insertion site of the kanamycin cassette further proved that the size of the PCR product from the mutant strain was increased by ∼1.5 kb compared to that of the wild type. Nucleotide sequence analyses of the PCR products from the mutant and the parent strains also confirmed the insertion of the kanamycin cassette at the AccI site of the zntA gene of the chromosome. As shown in Table 2, the MICs of zinc and cobalt for the mutant RN-MZ (zntA) were each 0.5 mM compared to 5 and 3 mM for the parent strain, respectively. Thus, the mutant RN-MZ (zntA) strain was sensitive to zinc and cobalt ions.

FIG. 1.

Construction of the zntA mutant. First, a 2.9-kb EcoRI fragment containing zntR and zntA was cloned into pTZ18R (ΔSmaI-SalI) to construct the pTZ18R-ZC plasmid (5.8 kb). A 1.5-kb fragment containing the kanamycin resistance cassette from pOSTkan was introduced into the AccI site within zntA by blunt-end ligation. From the resulting plasmid, pTZ18R-ZCK (7.3 kb), the EcoRI fragment was subcloned into the pBT2 shuttle vector to generate the pBT2-ZCK plasmid (11 kb). ERI, EcoRI; A, AccI; X, XbaI; P, PstI; Amp, ampicillin; Kan, kanamycin; Cat, chloramphenicol; ori E, E. coli origin of replication; ori S(ts), temperature-sensitive S. aureus origin of replication.

TABLE 2.

MICs of zinc and cobalt ions for the different S. aureus strains used in this study

| S. aureus strain | MICa (mM) of:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Zn2+ | Co2+ | |

| RN4220 | 5.0 | 3.0 |

| RN-CMZ | 5.0 | 3.0 |

| RN-MZ | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| RN-ZC | >10.0 | 5.0 |

MICs were determined by growing cells in 5 ml of TSB medium with appropriate concentrations of zinc and cobalt ions for 24 h.

In order to determine whether the cloned DNA fragments (zntR and zntA) can complement in trans the zinc- and cobalt-sensitive phenotypes, plasmid pCU1-ZC was transformed into the mutant RN-MZ. As shown in Table 2, the MICs of zinc and cobalt for the mutant containing pCU1-ZC increased from 0.5 mM to 5 and 3 mM, respectively. Thus, the zinc- and cobalt-sensitive phenotypes of the mutant RN-MZ were fully complemented by the pCU1-ZC plasmid. The higher MIC of the RN-ZC compared to wild type (∼2-fold) was due to the presence of the multiple copies of znt. However, no effect on the MICs of cadmium, nickel, copper, arsenic, and mercury was observed either in the parent or in the mutant strain. We also observed that the growth of the RN-MZ under normal physiological conditions was not affected and was similar to that of the wild type (data not shown). This suggested that the zntA was not essential for the growth of S. aureus under normal conditions.

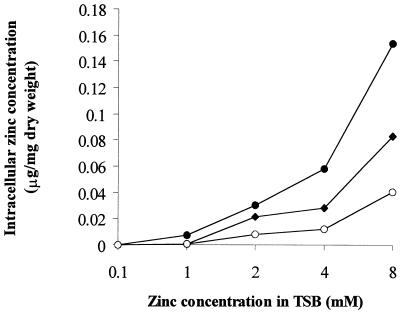

Functional analysis of ZntA.

The intracellular concentration of zinc was measured to determine whether ZntA is involved in the influx or efflux of zinc ions. S. aureus strains grown in TSB medium containing various concentrations of zinc were collected, washed, and digested (2) and were used to determine zinc concentration by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. As shown in Fig. 2, the mutant strain accumulated zinc ion to twice the level of the parent strain. In contrast, in the RN-ZC strain (containing multiple copies of znt) the intracellular zinc concentration was only one-half that of the parent strain. The accumulation of high concentrations of zinc in the zntA mutant is probably indicative of its inability to efflux zinc. The lower zinc concentration in RN-ZC further supports the involvement of ZntA in its transport. Again, the RN-ZC strain showed more-efficient efflux of zinc ions from cells compared to the parent strain due to an increased intracellular level of ZntA.

FIG. 2.

Zinc accumulation by RN4220, RN-ZC and the zntA mutant (RN-MZ) strains of S. aureus. The bacteria grown in TSB medium containing various concentrations of zinc were collected and washed, and the levels of intracellular zinc were determined by atomic absorption spectrometry. Symbols: ⧫, RN4220; •, RN-MZ; ○, RN-ZC.

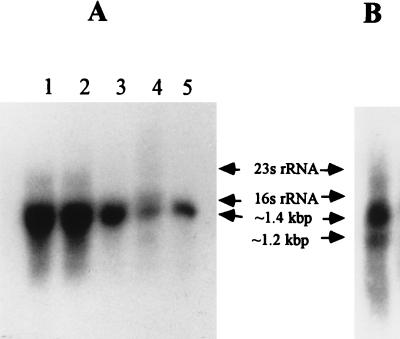

Analysis of znt transcript.

A preliminary study was conducted to evaluate the effect of various concentrations of zinc on the growth of wild-type and mutant S. aureus strains. Northern blot analysis was performed to evaluate the expression of znt during growth of S. aureus strains in the presence or in the absence of zinc. Total RNA was isolated from cultures exposed to different concentrations of zinc and then separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose. Northern blot analysis revealed the presence of only one transcription unit of ∼1.4 kb when fragments containing a portion of zntR and zntA were used as probes (Fig. 3A). This size seemed to be in good agreement with that of the predicted 1.3-kb operon. It also implied that zntR and zntA were cotranscribed. Interestingly, as shown in Fig. 3A (lane 4), the zntA mutant also expressed a ∼1.4-kb transcript size, which was almost equal to the transcript size of zntA in the wild-type strain (lane 5). We assumed that although the insertion inactivated zntA, it read through the kanamycin resistance gene and produced a ∼1.4-kb transcript. When the kanamycin resistance cassette was used as a probe, Northern blotting revealed two hybridizing bands (∼1.4 and ∼1.2 kb) in the mutant total RNA (Fig. 3B). The ∼1.2-kb unit is the transcriptional product of the kanamycin resistance cassette.

FIG. 3.

Northern blot analysis of the zntR and zntA. Total RNA (10 μg) isolated from samples was separated electrophoretically and transferred by blotting onto a membrane. (A) Lanes: 1, S. aureus RN4220 grown with 2 mM zinc to mid-log phase and then diluted (1:100) in TSB medium containing 1.5 mM zinc; 2, S. aureus RN4220 grown with 0.5 mM zinc to mid-log phase and then diluted (1:100) in TSB medium containing 1.5 mM zinc; 3, S. aureus RN4220 grown without zinc to mid-log phase and then diluted (1:100) in TSB medium containing 1.5 mM zinc: 4, RN-MZ grown in TSB; 5, S. aureus RN4220 grown in TSB. The blot was probed with a radiolabeled DNA fragment encompassing zntR and zntA. The sizes of the rRNA are marked with arrows. (B) An RNA sample (10 μg) isolated from the mutant RN-MZ strain was separated electrophoretically and transferred by blotting onto a membrane. The blot was probed with a radiolabeled DNA fragment containing the kanamycin gene.

We observed that resistance to heavy metal ions was dependent not only on the gene copy number but also on the transcriptional regulation of this operon (5, 8, 10, 12, 13). The cultures that were precultivated in the presence of zinc ions showed a shorter lag period than those cultivated in its absence. Furthermore, the induced growth seemed to be dependent on the zinc concentration (data not shown). Northern blot analysis further supported this observation. The concentrations of mRNA corresponding to zntA in the zinc-treated culture were more than those of untreated cultures (Fig. 3A, lanes 1 to 3).

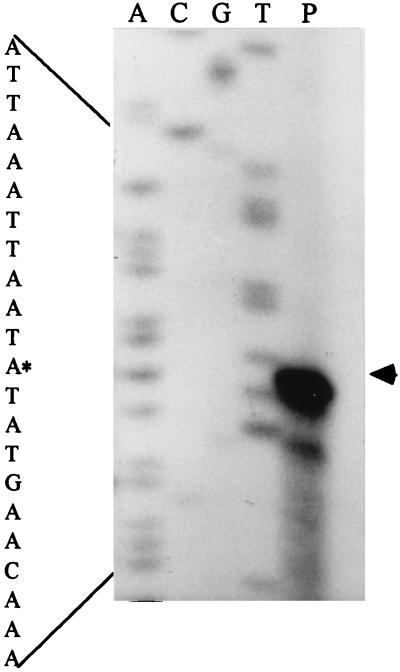

Mapping of znt transcription start site.

To define the transcription unit more precisely, the 5′ end of zntR transcript was mapped. A 19-base oligonucleotide specific to the coding region was annealed with total RNA and extended in a primer extension assay. The transcription start site was located in between the −10 region and an imperfect 8-2-8 hyphenated inverted repeat that represented a potential regulatory site (Fig. 4). The presence of a minor band in Fig. 4 (lane P) may be due to a minor transcription start site in the znt operon, to the degraded mRNA product, or to RNA secondary structures.

FIG. 4.

Mapping of the 5′ end of zntR gene by primer extension analysis. Total RNA from the parent strain RN4220 was hybridized with an oligonucleotide complementary to the mRNA of zntR locus and extended by AMV reverse transcriptase (lane P). Lanes T, G, C, and A correspond to a dideoxy sequencing reaction performed with the same primer. The sequencing encompassing the initiation start (marked by an asterisk) is enlarged.

Localization of znt on the bacterial chromosome.

Various known S. aureus gene clones available in our laboratory were used to explore the location of znt on the bacterial chromosome. These include lytI (15), lytM (24), atl (21), brnQ (30), and others. Dot blot studies showed hybridization of znt with the cosmid clones containing the lytI gene, thus mapping it within the SmaI-B fragment of S. aureus (14).

In our initial studies, we found that many coagulase-positive and coagulase-negative strains of staphylococci were resistant to zinc (∼4.0 mM) and cobalt (∼3.0 mM) ions. We have subsequently isolated a chromosomal fragment of S. aureus conferring resistance to zinc and cobalt ions. Northern blot analysis indicated that the zntR and zntA genes were cotranscribed. Their transcription was inducible and dependent on the concentration of zinc ions. The mutational and complementation analyses of the zntA gene demonstrated that the operon was involved in the transport of zinc and probably cobalt ions. The zinc transport analysis indicated that the zntA mutant accumulated more zinc ion than did the wild-type strain. In addition, the resistance level of zinc and cobalt ions depended on the copy number of znt. These results suggest that ZntA is a structural gene which functions as a transporter of zinc and cobalt ions rather than the sensor of the two-component system. In mutational analysis, the insertion of a kanamycin resistance cassette was found to be close to the C-terminal end of ZntA. Although the insertion fragment was read through, the resulting amino acid residues (data not shown) in the C terminus lacked the characteristic histidine-rich region, and the fusion protein thus was nonfunctional. These observations implied that the C terminus of ZntA, which contains the histidine-rich region, is important for zinc transport.

Uptake and efflux of the heavy metal ions in bacteria are energy-dependent processes (27). However, no gene was found to be present in the staphylococcal znt operon for the necessary energy-transducing systems for transporting zinc and cobalt ions. ZntA also lacks the characteristic ATP-binding sites. No significant differences were observed in the growth kinetics of the mutant under normal physiological conditions, suggesting that zntA may be dispensable in S. aureus.

Our results indicate that we have cloned the gene responsible for the transport of zinc and probably cobalt ions in S. aureus allowing tolerance to heavy metals. The zntA gene codes for a transmembrane structural protein responsible for the efflux of zinc and cobalt ions. The zntR gene also encodes a regulatory molecule which probably autoregulates its own expression. We are currently investigating the functional aspects of zntR.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to James Webb (Chemistry Department, Illinois State University) for his help in zinc measurement. We thank Vineet Singh, Anthony Otsuka, and David Williams for their critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the NIH-AREA, the AHA-IL affiliate, and from K. Singh and Associates, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Augustin J, Rosenstein R, Wieland B, Schneider U, Schnell N, Engelke G, Entian K D, Gotz F. Genetic analysis of epidermin biosynthetic genes and epidermin-negative mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Eur J Biochem. 1992;204:1149–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beard S J, Hashim R, Membrillo-Hernandez J, Hughes M N, Poole R K. Zinc(II) tolerance in E. coli K-12: evidence that the zntA gene (o732) encodes a cation transport ATPase. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:883–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biswas I, Gruss A, Ehrlich S D, Maguin E. High-efficiency inactivation and replacement system for gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3628–3635. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3628-3635.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruckner R. Gene replacement in Staphylococcus carnosus and Staphylococcus xylosus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;151:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conklin D S, McMaster J A, Culbertson M R, Kung C. COT1, a gene involved in cobalt accumulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3678–3688. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diorio C, Cai J, Marmor J, Shinder R, DuBow M S. An Escherichia coli chromosomal ars operon homolog is functional in arsenic detoxification and is conserved in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2050–2056. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2050-2056.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodd I B, Egan J B. Improved detection of helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motifs in protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5019–5027. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.17.5019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huckle J W, Morby A P, Turner J S, Robinson N J. Isolation of a prokaryotic metallothionein locus and analysis of transcription control by trace metal ions. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:177–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hugher M N, Poole R K. Metal speciation and microbial growth—the hard (and soft) facts. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:725–734. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji G, Silver S. Regulation and expression of the arsenic resistance operon from Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pI258. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3684–3694. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3684-3694.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jose P C, Price J A, Maguin E, Scott J R. An M protein with a single C repeat prevents phagocytosis of Streptococcus pyogenes: use of a temperature-sensitive shuttle vector to deliver homologous sequences to the chromosome of S. pyogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:809–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamizono A, Nishizawa M, Teranish Y, Murata K, Kimura A. Identification of a gene conferring resistance to zinc and cadmium ions in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;219:161–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00261172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lelie D, Schwuchow T, Schwidetzky U, Wuertz S, Baeyens W, Mergeay M, Nies D H. Two-component regulatory system involved in transcriptional control of heavy-metal homeostasis in Alcaligenes eutrophus. Mol Microbiol. 1997;213:493–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.d01-1866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mani N, Baddour L M, Offutt D Q, Vijaranakul U, Nadakavukaren M J, Jayaswal R K. Autolysis-defective mutant of Staphylococcus aureus: pathological considerations, genetic mapping and electron microscopic studies. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1406–1409. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1406-1409.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mani N, Tobin P, Jayaswal R K. Isolation and characterization of autolysis-defective mutants of Staphylococcus aureus created by Tn917-lacZ mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1493–1499. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1493-1499.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mead D A, Szczesna-Skorupa E, Kemper B. Single-stranded DNA ‘blue’ T7 promoter plasmid: a versatile tandem promoter system for cloning and protein engineering. Protein Eng. 1986;1:67–74. doi: 10.1093/protein/1.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nies D H. CzcR and CzcD, gene products affecting regulation of resistance to cobalt, zinc, and cadmium (czc system) in Alcaligenes eutrophus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:8102–8110. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.8102-8110.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nies D H, Brown N L. Two-component systems in regulation of heavy metal resistance. In: Silver S, Walden W, editors. Metal ions in gene regulation. New York, N.Y: Chapman and Hall; 1997. pp. 77–103. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novick R P. Molecular biology of the staphylococci. New York, N.Y: VCH Publishers; 1990. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nucifora G, Lien C, Misra T K, Silver S. Cadmium resistance from Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pI258 cadA gene results from a cadmium-efflux ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3544–3548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oshida T, Sugai M, Komassuzawa H, Hong Y-M, Suginaka H, Tomasz A. A Staphylococcus aureus autolysin that has an N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase domain and an endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase domain: cloning sequence analysis and characterization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:285–289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmiter R D, Findley S D. Cloning and functional characterization of a mammalian zinc transporter that confers resistance to zinc. EMBO J. 1995;14:639–649. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paulsen I T, Saier M H. A novel family of ubiquitous heavy metal ion transport proteins. J Membr Biol. 1997;156:99–103. doi: 10.1007/s002329900192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramadurai L, Jayaswal R K. Molecular cloning, sequencing, and expression of lytM, a unique autolytic gene of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3625–3631. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3625-3631.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenstein R, Peschel A, Wieland B, Gotz F. Expression and regulation of the antimonite, arsenite, and arsenate resistance operon of Staphylococcus xylosus plasmid pSX 267. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3676–3683. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3676-3683.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silver S, Phung L T. Bacterial heavy metal resistance: new surprises. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:753–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silver S, Misra T K, Laddaga R A. Bacterial resistance to toxic heavy metals. In: Beveridge T J, Doyle R J, editors. Metal ions and bacteria. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. pp. 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vijaranakul U, Xiong A, Lockwood K, Jayaswal R K. Cloning and nucleotide sequencing of a Staphylococcus aureus gene encoding a branched-chain-amino-acid transporter. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:763–767. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.763-767.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon K P, Silver S. A second gene in the Staphylococcus aureus cadA cadmium resistance determinant of plasmid pI258. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7636–7642. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.23.7636-7642.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]