Abstract

An open reading frame coding for a putative protein-serine/threonine phosphatase was identified in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrodictium abyssi TAG11 and named Py-PP1. Py-PP1 was expressed in Escherichia coli, purified from inclusion bodies, and biochemically characterized. The phosphatase gene is part of an operon which may provide, for the first time, insight into a physiological role for archaeal protein phosphatases in vivo.

Reversible phosphorylation of proteins plays an important role in a wide variety of cellular processes, including regulation of metabolic pathways, cell differentiation, and signal transduction (4, 6). Serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues are the main targets for reversible phosphorylation in members of the domains Eucarya and Bacteria (7). The eukaryal protein-serine/threonine phosphatases can be classified in four major groups, PP1, PP2A, PP2B, and PP2C, according to their substrate specificity, metal ion dependence, and sensitivity to inhibitors (5). Sequence comparison of the primary structures indicates that PP1, PP2A, and PP2B all have a common catalytic core of about 280 amino acids (1).

In Archaea, the third domain of life forms (28), little is known about protein phosphorylation and the proteins involved therein. Recently, serine/threonine-specific protein phosphatase activities have been identified in the thermoacidophilic crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus (PP1-arch1 [11, 16]) and in two euryarchaeota, Methanosarcina thermophila (PP1-arch2 [18]) and Haloferax volcanii (17). The enzymatic activity of each of these proteins is dependent on the presence of divalent metal ions. PP1-arch2 from M. thermophila is sensitive to inhibitors of eukaryal protein-serine/threonine phosphatases, whereas the other archaeal phosphatases are not. The deduced amino acid sequences of PP1-arch1 and PP1-arch2 show similarity (27 to 31%) to sequences of the eukaryal PP1/PP2A/PP2B superfamily of protein-serine/threonine phosphatases (17). Nothing is currently known about the physiological role of these protein phosphatases in vivo. Members of the genus Pyrodictium (24, 26) are among the most thermophilic organisms known to date. Growth occurs from 80 up to 110°C, with an optimum between 100 and 105°C, depending on the species (25). Strains of Pyrodictium are often chemolithoautotrophs, gaining energy by the formation of H2S from elemental sulfur and molecular hydrogen. Pyrodictium species are further characterized by the synthesis of a unique extracellular network (24). This network consists of hollow tubules (cannulae), which are composed of at least three protein subunits (14, 21). Based on their N-terminal sequences, we have isolated the corresponding genes, canA, canB, and canC (17a). Downstream of canB, an additional open reading frame, pyp1, encoding a polypeptide with homology to the archaeal and eukaryal protein-serine/threonine phosphatases was identified. In this paper we report the expression, purification, and functional characterization of the corresponding polypeptide, Py-PP1 (Pyrodictium PP1). The demonstration that canB and pyp1 are cotranscribed suggests a possible role for Py-PP1 in regulation or modification of the extracellular network.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression in Escherichia coli.

The gene for Py-PP1 was amplified by PCR (3 min at 94°C; 34 cycles of 1 min 10 s at 94°C, 1 min 20 s at 55°C, and 1 min 35 s at 72°C; 10 min at 72°C) from 5 ng of p34/1-9 plasmid DNA, using Taq Extender Polymerase (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany). The primers were designed to introduce an NdeI site at the initiation codon (5′-GTG CAG CGC ATA TGC AGA GGG AG-3′) and a NotI site downstream of the stop codon (5′-GGG GCG GAG CGG CCG CTT CTA GCT CC-3′). The resulting PCR product was cloned into the NdeI/NotI sites of expression vector pET17B (AGS, Heidelberg, Germany) to form plasmid pETpp1.

Purification of recombinant Py-PP1.

The cell pellet obtained from 600 ml of culture was washed with 160 ml of buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), pelleted again, and resuspended in 30 ml of the same buffer. Cells were lysed by two passages through a French pressure cell at 20,000 lb/in2. The crude extract was centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm in a Sorvall SS34 rotor. The pellet was resuspended in 25 ml of buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM EDTA, 200 μg of lysozyme per ml, 5 M urea, and 2% Triton X-100 and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Insoluble proteins were precipitated (10 min, 11,000 rpm, JA20 rotor), dissolved in 4 ml of denaturing solution (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 20 mM EDTA, 20 mM dithiothreitol, 6 M guanidinium-HCl), and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Particles were removed by centrifugation (10 min, 10,000 rpm, JA20 rotor). Denatured Py-PP1 was renatured by dilution (1:100) into renaturing solution (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 M l-arginine; precooled to 4°C) and incubated at 4°C overnight. Finally, the protein solution was concentrated about fourfold (Amicon ultrafiltration cell; 10 K Polysulfon membrane [Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany]) and dialyzed extensively against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–25 mM NaCl. Aliquots were stored frozen at −80°C or refrigerated at 4°C.

Enzyme activity assay.

The protein phosphatase activity of Py-PP1 was tested with a serine/threonine phosphatase assay system from Promega (Heidelberg, Germany). The standard assay mixture contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.0 at 90°C), 25 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MnCl2, 5.5 μg of serine/threonine phosphopeptide (RRA[pT]VA), and 100 ng of enzyme in a total volume of 50 μl. Phosphatase activity was monitored for 10 min at 90°C by submerging the tubes completely in a water or glycerol bath. Reactions were stopped by transferring the tubes to ice water. After cooling to 0°C, released Pi was quantitated with malachite green as described elsewhere (16). All data presented are corrected for spontaneous Pi release. Under the conditions described, assays were linear with respect to time and amount of enzyme added.

Standard procedures.

Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Heil and Zillig (9). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed as described by Laemmli (15).

Sequence analysis.

The Wisconsin Package software (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.) was used for sequence analysis.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence for the Py-PP1-encoding gene reported in this paper has been submitted to the EMBL data bank and assigned accession no. Y12396.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequence analysis.

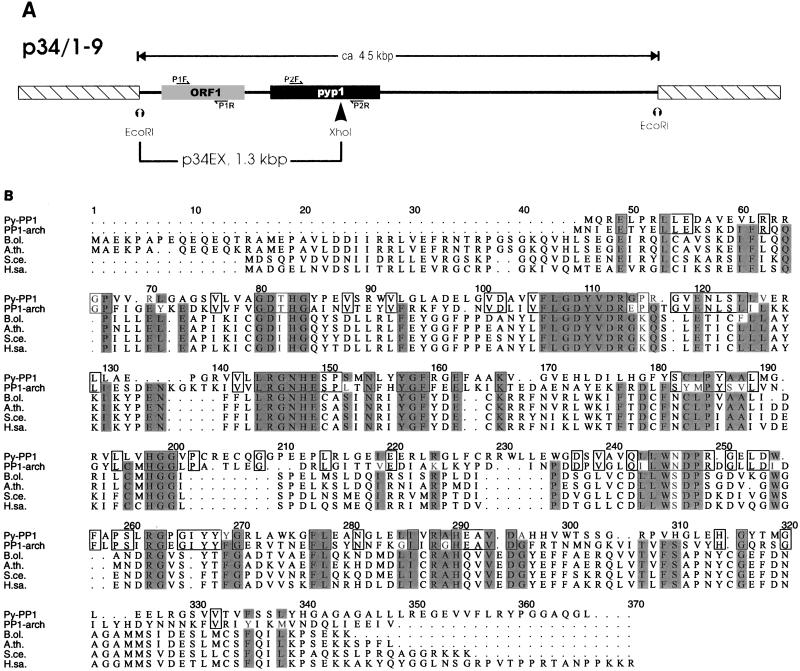

The gene for the B subunit of the extracellular network of P. abyssi TAG11 was isolated from a λgt11 clone on a 4.5-kbp EcoRI fragment (canB [Fig. 1A and reference 17a). Immediately downstream from canB, a 906-bp-long open reading frame (pyp1 [Fig. 1A]) was identified. This gene codes for a polypeptide with a calculated molecular mass of 33,340 Da (pI = 6.15). FASTA homology searches showed that the derived polypeptide has about 40% identity (65% similarity) with PP1-arch1 and PP1-arch2, protein-serine/threonine phosphatases identified in S. solfataricus (17) and M. thermophila TM-1 (23), respectively, and about 31% identity with eukaryal phosphatases of the PP1/PP2A/PP2B superfamily. Highest identities to eukaryal proteins were obtained with two plant enzymes: PP1 from Brassica oleracea (35.2% identity) and PP1 from Arabidopsis thaliana (33.5% identity). Three sequence signatures (GDTHG, GDYVDR, and LRGNHE) characteristic of protein-serine/threonine phosphatases were also identified. Figure 1B shows a sequence alignment of Py-PP1 with PP1-arch1 from S. solfataricus, PP1-arch2 from M. thermophila TM-1, and several eukaryal protein-serine/threonine phosphatases. The sequences can be aligned unambiguously over their entire lengths; conserved residues are scattered over a wide range. The archaeal proteins are shortened at their N termini relative to the eukaryal proteins. The crenarchaeal enzymes, Py-PP1 and PP1-arch1, possess additional residues which introduce gaps in the alignment (Fig. 1B, at positions 140, 165, 200, 230, and 250).

FIG. 1.

(A) Partial restriction map of the 4.5-kbp EcoRI fragment harboring the pyp1 gene from P. abyssi TAG11. Identified genes are marked by grey (canB [ORF1]) and black (pyp1) boxes. Subclone p34EX, containing a 1.3-kbp EcoRI/XhoI fragment, was sequenced on both strands. The pyp1 gene sequence was completed by sequencing flanking regions in p34/1-9. The orientations of primers used for RT-PCR experiments (P1F, P1R, P2F, and P2R [Fig. 4]) are indicated by half-arrows. The scheme is not drawn to scale. (B) Sequence alignment of Py-PP1 with PP1-arch1 from S. solfataricus (accession no. U35278), PP1-arch2 from M. thermophila (U96772), and several eukaryal protein-serine/threonine phosphatases. The eukaryal sequences chosen for the alignment have high similarity scores by pairwise comparison with Py-PP1. Amino acids conserved in at least six of the seven sequences shown are shaded. B.ol., Brassica oleracea (P48487); A.th., Arabidopsis thaliana (P30366); S.ce., Saccharomyces cerevisiae (P32598); H.sa., Homo sapiens (P37140).

Expression in E. coli.

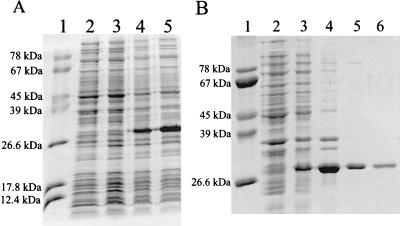

To investigate the enzymatic properties of Py-PP1, we have established a highly efficient expression system in E. coli. The putative phosphatase gene was cloned into the expression vector pET17B by a PCR-based approach, yielding the construct pETpp1. Crude extracts of the recombinant cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE before and after induction with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Fig. 2A). Wild-type pET17B was included as control in parallel experiments. A polypeptide of the expected size (33 kDa) was synthesized in large amounts after induction in cells containing pETpp1 but not in control cells.

FIG. 2.

(A) Expression of Py-PP1 in E. coli. The gene for Py-PP1 was cloned into expression vector pET17B to form plasmid pETpp1 as described in Materials and Methods. E. coli BL21(DE3) was transformed with plasmid pETpp1. Control cells were transformed with wild-type pET17B. Lane 1, size standard; lane 2, crude extract of induced control cells; lanes 3 to 5, crude extracts of cells containing pETpp1 before (lane 3) and after (lane 4, 2 h; lane 5, 4.5 h) induction with 0.3 mM IPTG. After induction with IPTG, a polypeptide of ca. 33 kDa is synthesized in cells containing pETpp1. (B) Purification of recombinant Py-PP1. Purification steps were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Lane 1, size standard; lanes 2 and 3, crude extract before and after induction with IPTG; lane 4, pellet after passage through a French press; lane 5, washed pellet; lane 6, renatured protein. See Materials and Methods for details.

Purification and refolding of the recombinant enzyme.

Initial experiments revealed that the recombinant protein was sequestered inside insoluble complexes (data not shown). These complexes were purified by washing in a buffer containing 5 M urea and 2% Triton X-100 (Fig. 2B, lane 5). The recombinant protein was then solubilized in 6 M guanidinium chloride. Denatured proteins (ca. 1 μg/μl) were refolded by dilution (100-fold) into a buffer containing 0.5 M l-arginine; one-step dilution was found to be very important for the refolding process. Stepwise dilution of the inactive enzyme solution to the appropriate buffer volume or dialysis led to precipitation (data not shown). The renatured enzyme was then dialyzed to remove the l-arginine and concentrated about fourfold (40 ng/μl). Precipitation was observed at higher protein concentrations.

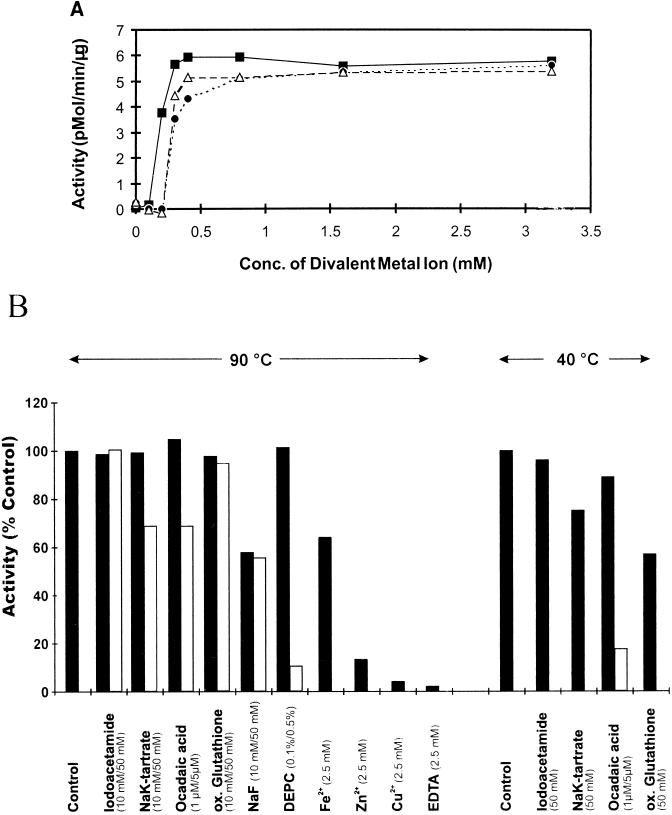

Enzymatic properties of Py-PP1.

The protein phosphatase activity of renatured Py-PP1 was assayed with a commercially available kit. This kit, designed for eukaryal protein-serine/threonine phosphatases, contains as the substrate a phosphorylated peptide which is not denatured at elevated temperatures. Standard assays were carried out at 90°C for 10 min. Enzymatic phosphate release was dependent on the presence of divalent ions such as Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+, or Mg2+ (Fig. 3A). The first three cations were much more effective than Mg2+. Maximal activation was induced at concentrations in the range of 0.5 to 1 mM, while concentrations between 5 and 10 mM were required with Mg2+. Ca2+ had no stimulatory effect. The addition of any second divalent ion in combination with Mn2+, the most effective activator, did not increase the activity relative to the addition of Mn2+ alone (data not shown). Phosphate release was inhibited by EDTA, Cu2+, Zn2+, and Fe2+ (Fig. 3B). Py-PP1 further was inhibited by NaF, NaK tartrate, 0.5% diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC), and okadaic acid. At lower DEPC concentrations (0.05 and 0.1%), no inhibition was observed, even when the assay mixtures were preincubated (without substrate) at room temperature for up to 1 h (data not shown). Inhibition by okadaic acid and oxidized glutathione was greater at 40°C than at 90°C (Fig. 3B). Iodoacetamide (Fig. 3B) and pH changes (pH 4.5 to 8.0) had no significant effect on enzyme activity. No activity was observed below pH 4.0 or above 8.5 (data not shown). Py-PP1 was active in the range from 40 to 110°C. Maximal activity was obtained at 90°C. The enzyme was very stable at 90°C {half-life at 90°C (t1/2[90°C]) ≈ 180 min}, but it was rapidly inactivated at temperatures above 100°C (t1/2[100°C] ≈ 7 min; t1/2[105°C] ≈ 3 min).

FIG. 3.

(A) Activation of Py-PP1 by divalent metal ions. Recombinant Py-PP1 was assayed under standard conditions except that instead of 2.5 mM MnCl2, the following salts were added at the indicated concentrations: MnCl2 (■), NiCl2 (▵), and CoCl2 (•). (B) Effects of potential inhibitors on Py-PP1, summarized from results of several experiments. Recombinant Py-PP1 was assayed under standard conditions except that the components listed were present at the indicated final concentrations. Black and white bars correspond to the lower and higher, respectively, concentrations tested. The assay temperature is indicated at the top. Results are reported as the percentage of activity measured in the absence of additions. ox., oxidized.

Detection of phosphoproteins in vivo.

P. abyssi TAG11 cells were labeled with 32Pi for 1 h in the exponential growth phase. Proteins in whole-cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography. Six bands with estimated molecular masses between 30 and 250 kDa were visible on the X-ray film, indicating the presence of at least six phosphorylated polypeptides in P. abyssi TAG11 under these conditions. No labeled polypeptide could be dephosphorylated with recombinant Py-PP1 (data not shown).

Expression of Py-PP1 in vivo.

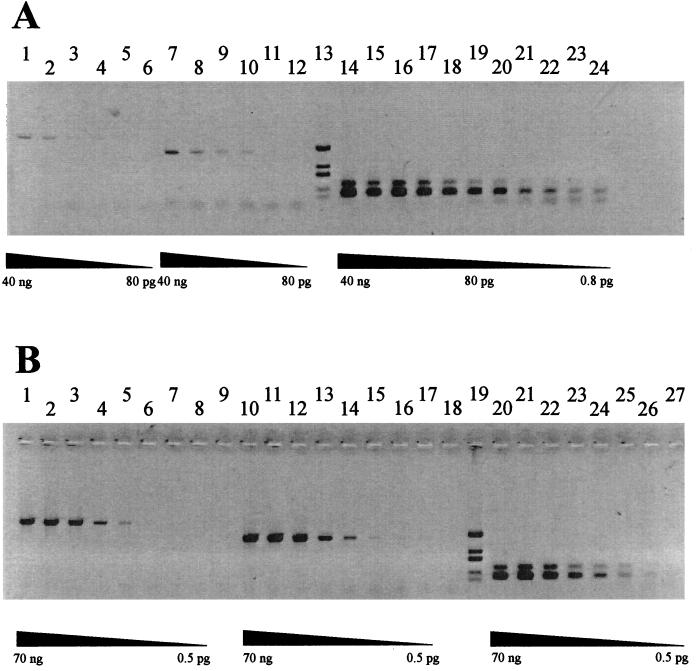

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) is a highly sensitive method to determine the presence of an RNA template. We have used this technique to investigate the possible coexpression of both genes identified on clone p34/1-9. For these experiments, we designed primers to amplify internal parts of canB and of the phosphatase gene pyp1 (Fig. 1A). With the primer combination P1F-P2R, parts of both genes and the intergenic spacer can be amplified. From chromosomal DNA, all three PCR products are amplified with the same efficiency, reflecting identical copy numbers of both genes (Fig. 4B). From RNA, the PCR product corresponding to canB is amplified much more effectively than the phosphatase gene. This indicates that canB is more frequently transcribed than pyp1. A signal was also detected with the primer combination P1F-P2R (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 to 6). This shows that both genes are transcribed into a single mRNA. Signals obtained with phosphatase-specific primers have nearly the same intensity as the band obtained from the cotranscript, suggesting that all pyp1 transcription is due to the canB promoter and not to an independent pyp1 promoter.

FIG. 4.

RT-PCR analysis using total RNA (A) or chromosomal DNA (B) from P. abyssi TAG11 as the template. RNA was isolated by the method of Chomczynski and Sacchi (3) and treated with DNase for 30 min at 37°C. RT-PCRs were performed with the Titan RT-PCR system (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) as specified by the manufacturer. Each primer combination was tested with decreasing amounts of template. From chromosomal DNA, all three PCR products are amplified with the same efficiency. With RNA as the template, the same PCR products are obtained, but the yield varies significantly. Primer pairs (see Fig. 1) used: P1F-P2R (A, lanes 1 to 6; B, lanes 1 to 8); P2F-P2R (A, lanes 7 to 12; B, lanes 10 to 17); P1F-P1R (A, lanes 14 to 24; B, lanes 20 to 27). Lanes in panel A 13 and 19 in panel B, molecular weight standard (DdeI-digested pIC19H).

DISCUSSION

Based on sequence homology, we have identified a gene for a protein-serine/threonine phosphatase, Py-PP1, in the hyperthermophilic crenarchaeon P. abyssi TAG11. The primary structure of Py-PP1 has high similarity with those of PP1-arch1 and PP1-arch2, protein-serine/threonine phosphatases recently isolated from S. solfataricus (17) and M. thermophila (23) (about 40% identity) and PP1/PP2A/2B phosphatases from Eucarya (31 to 34% identity). To confirm the function predicted from sequence analysis, we have expressed the polypeptide in E. coli and investigated the biochemical properties of the recombinant enzyme. In contrast to PP1-arch1 and PP1-arch2, the Pyrodictium enzyme was not produced in a soluble form but rather was trapped within inclusion bodies. Soluble Py-PP1 was obtained by denaturation in guanidinium chloride and subsequent renaturation. A phosphorylated peptide was used as the substrate for the activity assays, thereby permitting the experiments to be performed at physiological temperatures without denaturing the substrate. Metal ion (Mn2+, Ni2+, and Co2+) dependence of Py-PP1 as well as the effects of specific inhibitors were found to be similar to those described for PP1-arch from S. solfataricus and the phosphatase activities detected in two euryarchaeota, H. volcanii and M. thermophila (18, 19). No homologous sequences were detected in the genomes of Methanococcus jannaschii (2), Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (22), and Archaeoglobus fulgidus (13), demonstrating that the protein is not universally conserved among the Archaea.

In Eucarya, protein phosphatases play an important role in the regulation of metabolic pathways and the transfer of extracellular stimuli to the nucleus. Substrate specificity and phosphatase activity are modulated by different regulatory subunits which bind to the catalytic polypeptides (6, 10). Nothing is yet known about the roles of protein phosphatases or their regulation in Archaea. Active PP1-arch1 has been isolated as monomer from S. solfataricus and is presumedly not stably complexed with other (regulatory) polypeptides in vivo (17).

The gene organization in P. abyssi TAG11 provides the first evidence for a possible function of Py-PP1 phosphatase. The gene for Py-PP1 is located downstream of an open reading frame, canB, which codes for a component of the extracellular network of P. abyssi (17a). Sequence comparison with promoter regions of other archaeal genes revealed that the phosphatase gene is not preceded by a TATA box, the main component of archaeal promoters (8). We could demonstrate by RT-PCR that the phosphatase gene and canB are cotranscribed on one mRNA. The experiments also revealed that canB alone is transcribed much more efficiently. The data indicate that the cotranscript is produced by a read-through at the terminator of canB (possible termination sites [27] are found immediately downstream of canB). The cotranscription of these two genes suggests a possible regulatory role of the phosphatase activity on the expression or synthesis of the proteinaceous extracellular network of Pyrodictium. Investigations on the involvement of Py-PP1 in the synthesis of this unique structure are in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants of the DFG (Ra751/1-1) and Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barton G J, Cohen P T, Barford D. Conservation analysis and structure prediction of the protein serine/threonine phosphatases. Sequence similarity with diadenosine tetraphosphatase from Escherichia coli suggests homology to the protein phosphatases. Eur J Biochem. 1994;220:225–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bult J C, et al. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen P. The structure and regulation of protein phosphatases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:453–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen P. Classification of protein-serine/threonine phosphatases: identification and quantitation in cell extracts. Methods Enzymol. 1991;201:389–398. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)01035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen P T. Important roles for novel protein phosphatases dephosphorylating serine and threonine residues. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993;21:884–888. doi: 10.1042/bst0210884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cozzone A J. ATP-dependent protein kinases in Bacteria. J Cell Biochem. 1993;51:7–13. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240510103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hausner W, Frey G, Thomm M. Control regions of an archaeal gene. A TATA box and an initiator element promote cell-free transcription of the tRNA(Val) gene of Methanococcus vannielii. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:495–508. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90492-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heil A, Zillig W. Reconstitution of a bacterial DNA-dependent RNA-polymerase from isolated subunits as a tool for the elucidation of the role of the subunits in transcription. FEBS Lett. 1970;11:165–168. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(70)80519-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter T. Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling. Cell. 1995;80:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennelly P J, Oxenrider K A, Leng J, Cantwell J S, Zhao N. Identification of a serine/threonine-specific protein phosphatase from the archaebacterium Sulfolobus solfataricus. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6505–6510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennelly P J, Potts M. Fancy meeting you here! A fresh look at “prokaryotic” protein phosphorylation. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4759–4764. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4759-4764.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klenk H P, et al. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature. 1997;390:364–370. doi: 10.1038/37052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.König H, Messner P, Stetter K O. The fine structure of the fibers of Pyrodictium occultum. FEMS Lett. 1988;49:207–212. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanzetta P A, Alvarez L J, Reinach P S, Candia O A. An improved assay for nanomole amounts of inorganic phosphate. Anal Biochem. 1979;100:95–97. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leng J, Cameron A J, Buckel S, Kennelly P J. Isolation and cloning of a protein-serine/threonine phosphatase from an archaeon. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6510–6517. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6510-6517.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Mai, B. Unpublished data.

- 18.Oxenrider K A, Kennelly P J. A protein-serine phosphatase from the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;194:1330–1335. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oxenrider K A, Rasche M E, Thorsteinsson M V, Kennelly P J. Inhibition of an archaeal protein phosphatase activity by okadaic acid, microcystin-LR, or calyculin A. FEBS Lett. 1993;331:291–295. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80355-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pley U, Schipka J, Gambacorta A, Jannasch H W, Fricke H, Rachel R, Stetter K O. Pyrodictium abyssi, new species represents a novel heterotrophic marine archaeal hyperthermophile growing at 110°C. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1991;14:245–253. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rieger G, Rachel R, Hermann R, Stetter K O. Ultrastructure of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrodictium abyssi. J Struct Biol. 1995;115:78–87. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith D R, Doucette-Stamm L A, Deloughery C, Lee H, Dubois J, Aldredge T, Bashirzadeh R, Blakely D, Cook R, Gilbert K, Harrison D, Hoang L, Keagle P, Lumm W, Pothier B, Qiu D, Spadafora R, Vicaire R, Wang Y, Wierzbowski J, Gibson R, Jiwani N, Caruso A, Bush D, Reeve J N. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7135–7155. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7135-7155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solow B, Young J C, Kennelly P J. Gene cloning and expression and characterization of a toxin-sensitive protein phosphatase from the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina thermophila TM-1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5072–5075. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5072-5075.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stetter K O. Ultrathin mycelia-forming organisms from submarine volcanic areas having an optimum growth temperature of 105°C. Nature. 1982;300:258–260. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stetter K O. Hyperthermophilic procaryotes. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1996;18:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stetter K O, König H, Stackebrandt E. Pyrodictium gen. nov., a new genus of submarine disc-shaped sulphur reducing archaebacteria growing optimally at 105°C. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1983;4:535–551. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(83)80011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomm M, Hausner W, Hethke C. Transcription factors and termination of transcription in Methanococcus. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1994;16:648–655. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woese C R, Kandler O, Wheelis M L. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria and Eukarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]