Abstract

Introduction

Canine leptospirosis has always been a differential diagnosis in dogs presenting with clinical signs and blood profiles associated with kidney and/or liver disease. The conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) provides diagnoses, but real-time PCR-based tests provide earlier confirmation and determine the severity of infection, especially in the acute stage, allowing early detection for immediate treatment decisions. To our knowledge, real-time PCR has not been routinely adopted for clinical investigation in Malaysia. This study evaluated TaqMan real-time PCR (qPCR) assays diagnosing leptospirosis and compared their applicability to clinical samples from dogs with kidney and/or liver disease against a conventional PCR reference.

Material and Methods

The qPCR assays were validated using existing leptospiral isolates. Whole blood and urine samples were analysed using a conventional PCR, LipL32(1) and LipL32(2) qPCRs and a microscopic agglutination test. The sensitivity and specificity of the qPCRs were determined.

Results

The LipL32(1) qPCR assay had more diagnostic value than the LipL32(2) qPCR assay. Further evaluation of this assay revealed that it could detect as low as five DNA copies per reaction with high specificity for the tested leptospiral strains. No cross-amplification was observed with other organisms. Analysing the clinical samples, the LipL32(1) qPCR assay had 100.0% sensitivity and >75.0% specificity.

Conclusion

The LipL32(1) qPCR assay is sensitive, specific and has the potential to be applied in future studies.

Keywords: canine leptospirosis, qPCR, sensitivity, specificity

Introduction

Cases of canine leptospirosis have been reported worldwide and were often associated with the Canicola and Icterohaemorrhagiae serovars of Leptospira spp., but dogs may be infected with a wide range of serovars or genotypes (3, 37). The clinical presentation of canine leptospirosis ranged from mild to severe signs involving kidney and liver insufficiency and/or pulmonary haemorrhage (9, 17). In clinical cases, an early and accurate diagnosis of suspected leptospirosis in dogs is essential to allow an immediate decision on treatment and achieve a favourable outcome. Therefore, a validated diagnostic tool should be available to confirm a clinical suspicion of leptospirosis, especially when the clinical signs are not specific to the disease (19).

To date, isolation of the bacterium and serology using a microscopic agglutination test (MAT) remain the methods of reaching a definitive diagnosis. However, the isolation of Leptospira spp. requires the tedious step of obtaining a pure bacterial culture, which takes months in the laboratory, and isolation is therefore not suitable for detecting leptospirosis in the short acute phase (1). Serologically, MAT requires the maintenance of a panel of live cultured leptospiral antigens in the laboratory, and unlike diagnosis by bacteria isolation, this method benefits canine patients in the acute and convalescent phases (10). As alternatives to these methods, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays as both conventional and real-time (qPCR) variants have been widely used for diagnosing leptospirosis because they have reliable sensitivity. Both PCR assays were used to detect the pathogenic Leptospira spp. LipL32 gene (15, 18, 43). Low cost is an advantage of conventional PCR assays in detecting the LipL32 gene, therefore these assays are useful for routine clinical diagnosis. On the other hand, detecting the LipL32 gene using a qPCR has several advantages, including a shorter turnaround time, increased specificity when 5′ nuclease assay probes are used, and substantially less likelihood of cross-contamination (25).

In humans, the qPCR assay has been demonstrated suitable for clinical diagnosis of leptospirosis (23, 36, 40). A similar assay could be adopted for dogs, but the qPCR assay standardised for human clinical samples cannot be used directly for dogs, it needs to be validated using canine clinical samples (35). There is limited information on the analytical sensitivity of the qPCR assay with canine whole blood and urine samples (11, 43). Only one study evaluated the qPCR assay using experimentally contaminated whole blood and urine samples from healthy dogs (25).

In Malaysia, conventional PCRs have been used routinely (16, 21, 32), but the utility of a qPCR assay in detecting pathogenic Leptospira spp. in dog samples has not been established locally. Therefore, this experiment evaluated TaqMan qPCR assays and investigated their applicability in the diagnosis of canine leptospirosis compared with the conventional PCR as a reference method in whole blood and urine samples from dogs diagnosed with kidney and/or liver disease.

Material and Methods

Bacterial strains

Thirty-eight leptospiral strains from pathogenic, intermediate and saprophytic groups of seven species (L. biflexa, L. borgpetersenii, L. kirschneri, L. kmetyi, L. weilii, L. selangorensis and L. wolffii) that were frequently reported locally were selected and used for primer and TaqMan probe validation and optimisation. The leptospiral strains were provided by the Bacteriology Laboratory, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (FVM), Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) and had been isolated from local environmental and animal samplings. The serovars were maintained in Ellinghausen McCullough Johnson Harris (EMJH) media incubated at 30°C. The species and serovar were identified using partial 16S rRNA sequencing and serotyping, respectively (Table 1). An additional six bacterial isolates (other than Leptospira) from clinical specimens provided by the Bacteriology Laboratory (FVM, UPM) were included for primer and TaqMan probe validation (Table 1). The selected bacteria were grown overnight in nutrient broth at 37°C maintained in an aerobic condition. The microbial species were identified using a standard biochemical identification method.

Table 1.

List of bacteria used in the qPCR assay

| Bacterium (n = 44) | Number tested (n) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Pathogenic group | ||

| L. borgpetersenii serovar Ballum strain Mus 127 | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjobovis strain 117123 | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. borgpetersenii serovar Javanica | 1 | Dog |

| L. borgpetersenii serovar Javanica strain Veldrat Bataviae 46 | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. borgpetersenii serovar Tarassovi strain Perepelitsin | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. interrogans serovar Australis | 2 | Dog |

| L. interrogans serovar Australis strain Ballico | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. interrogans serovar Autumnalis strain Akiyami A | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. interrogans serovar Bataviae | 8 | Dog |

| L. interrogans serovar Bataviae strain Swart | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. interrogans serovar Canicola strain Hond Utrecht IV | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain M20 | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. interrogans serovar Djasiman strain Djasiman | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. interrogans serovar Hebdomadis strain Hebdomadis | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. interrogans serovar Icterohaemorrhagiae strain RGA | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. interrogans serovar Lai strain Lai | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. interrogans serovar Pomona strain Pomona | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. interrogans serovar Pyrogenes strain Salinem | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. kirschneri serovar Cynopteri strain 3522C | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. kirschneri serovar Grippotyphosa strain Moskva V | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. kmetyi serovar Malaysia strain Bejo-ISO9 | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| L. weilii serovar Celledoni strain Celledoni | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| Intermediate group | ||

| L. selangorensis | 3 | Environmental |

| L. wolffii | 5 | Environmental |

| Saprophytic group | ||

| L. biflexa serovar Patoc strain Patoc I | 1 | FVM, UPM |

| Other bacteria | ||

| Bacillus spp. (Gram positive) | 1 | Clinical |

| Escherichia coli (Gram negative) | 1 | Clinical |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Gram negative) | 1 | Clinical |

| Salmonella spp. (Gram negative) | 1 | Clinical |

| Staphylococcus aureus (Gram positive) | 1 | Clinical |

| Streptococcus spp. (Gram positive) | 1 | Clinical |

FVM – Faculty of Veterinary Medicine; UPM – Universiti Putra Malaysia

Sample collection

A total of 124 dogs identified with kidney and/or liver disease presented to a primary veterinary healthcare hospital (University Veterinary Hospital (UVH), FVM, UPM) or private veterinary clinics within a 10 km radius of UPM were recruited. Both diseases simultaneously afflicted 68 dogs, kidney disease was the complaint of 34 dogs, and liver disease affected the remaining 22. There were 102 dogs with acute clinical illness (≤7 days from infection) and 22 dogs with chronic clinical illness (>7 days from infection). The inclusion criteria of the recruited dogs were abnormal and elevated serum biochemistry parameters: urea >7.5 mmol/L, creatinine >176 μmol/L, alanine aminotransferase >90.0 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase >100 U/L. The duration of clinical illness for each dog was recorded and categorised based on published guidelines (13). Whole blood samples (of which 124 were used), serum (of which also 124 were tested) and urine samples (of which 113 were available) were collected from the dogs by experienced veterinarians. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (UPM/IACUC/AUP-R084/2016).

Serological detection using a microscopic agglutination test

Microscopic agglutination testing was performed using a panel of 20 leptospiral serovars, namely Australis, Autumnalis, Ballum, Bataviae, Canicola, Celledoni, Copenhageni, Cynopteri, Djasiman, Grippotyphosa, Hardjobovis, Hebdomadis, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Javanica, Lai, Malaysia, Patoc, Pomona, Pyrogenes and Tarassovi. Endpoint titres were determined using serial two-fold dilutions, and the last well with 50.0% agglutination was recorded. The cut-off for a positive MAT reaction was a titre ≥1:100, as defined in previous studies (26, 28), and the serovar with the highest MAT titre was recorded.

Extraction of genomic DNA

Genomic DNA from pure bacterial culture, whole blood and urine was extracted using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), and the protocols provided in the kit were used as described. One protocol was for non-nucleated cells and applied to whole blood, and the second protocol was for cultured cells and intended for urine and bacterial cultures. The total genomic DNA of the bacterial culture was quantified using an Infinite M200 Pro multimode plate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). The end products (DNA template) of bacterial culture, whole blood and urine extraction were inspected for purity using 1.5% agarose gels.

Molecular detection using a conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Sets of primers that targeted the 16S rRNA and LipL32 genes (2, 33) were used. The primer sequences for 16S rRNA were 5’-CAT GCAAGTCAAGCGGAGTA-3’ (forward) and 5’-AGT TGAGCCCGCAGTTTTC-3’ (reverse). The primer sequences for LipL32 were 5’-GTCGACATGAAAAAACTTTCGATT TTG-3’ (forward) and 5’-CTGCAGTTACTTAGTCGCGTCAGA AGC-3’ (reverse). The LipL32 gene was present only in pathogenic Leptospira spp. (38). The reaction volume was 25 μL and was optimised as follows: 12.5 μL 2× MyTaq Red Mix (Bioline, London, UK), 1.25 μL of forward primer and 1.25 μL of reverse primer, and 10 μL of DNA template. Amplification was optimised and performed in a Mastercycler Pro S thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany) with initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 58°C for 45 s, and DNA extension at 72°C for 30 s before the final extension step at 72°C for 6 min. Amplicons were analysed in trisborate-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid buffer at 80 V for 1.5 h with 1.5% gel electrophoresis. The gel was prestained with SYBR Safe DNA gel stain (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and examined using an Alphaimager gel documentation system (ProteinSimple, San José, CA, USA). Amplicons were identified by their band sizes at 541 base pairs (bp) (16S rRNA) and 756 bp (LipL32).

Primer and TaqMan probe specificity

Two sets of LipL32 primers (LipL32(1) and LipL32(2)) and TaqMan probes were used in this study (Table 2). All bacterial strains were tested using both sets of primers and respective TaqMan probes to determine the specificity in detecting pathogenic Leptospira spp. Pathogenic leptospiral strains were grouped as the positive control, intermediate and saprophytic leptospiral strains and other bacteria were grouped as a non-target negative control, and RNase free water (Qiagen) was used as a no-target negative control.

Table 2.

Primers and TaqMan probes for qPCR of pathogenic Leptospira spp.

| Target gene | Nucleotide sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| LipL32(1) | ||

| Forward | 5′-AAG CAT TAC CGC TTG TGG TG-3′ | 36 |

| Reverse | 5′-GAA CTC CCA TTT CAG CGA TT-3′ | |

| TaqMan probe | FAM/ZEN-5’-AA AGC CAG GAC AAG CGC CG-3’-IBFQ | |

| LipL32(2) | ||

| Forward | 5′-CGG GAG GCA GCA GTT AAG AAT-3′ | 41 |

| Reverse | 5′-ACG TAT GGT GCA AGC GTT GTT-3′ | |

| TaqMan probe | FAM/ZEN-5′-GCA ATG TGA TGA TGG TAC CTG CCT-3′-IBFQ | |

TaqMan qPCR parameters and thermal cycling condition

A 20 μL reaction mixture was prepared for the qPCR containing 10 μL 2× SensiFAST Probe Hi-ROX Mix (Bioline), 0.8 μL (400nM) of each forward and reverse primer, 0.2 μL (100nM) of TaqMan probe and 8.2 μL of DNA template. The reaction was subjected to an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, and finally 60°C for 5 min. Positivity was determined by the cycle threshold (Ct) value. The interpretations of Ct value were as follows: ≤29.00 denoted strong positive reactions, ≥30.00–≤37.00 positive reactions, and ≥38.00–≤40.00 weak reactions, which could represent infection states or environmental contamination (42). The assays were performed using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity of the qPCR assay was determined. A fivefold serial dilution of L. interrogans DNA was used as a standard control and the estimated genome size of L. interrogans was 4,627,366 bp (31). The number of DNA copies was calculated based on the following formula: (DNA amount (ng) × 6.022 × 1023)/(length of template (bp) × 1 × 109 × 650). The TaqMan qPCR was performed in triplicate, and DNA copies were averaged and recorded. The limit of detection (LOD) was determined based on the average amount from the triplicates of leptospiral DNA that could be detected. A standard curve was generated based on log DNA copies (x axis) and the mean Ct value (y axis). The qPCR amplification efficiency, E, was calculated using the formula E = 10(-1/slope). The coefficient of regression (R2) was also obtained from the standard curve to measure how well the regression predictions approximated the real data points (the closer R2 to 1, the better the prediction).

Statistical analysis

Positive detections of conventional PCR and qPCR in whole blood and urine samples were recorded and analysed using descriptive statistics with 95.0% confidence intervals (CIs) using SPSS Statistics version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). True positive leptospirosis and true negative leptospirosis groups were defined with the assumption that the conventional PCR was 100.0% sensitive and specific. The epidemiological sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of the qPCR assays were calculated using MedCalc Statistical Software version 2014 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium), with which a detailed analysis for the whole blood and urine assays was also made.

Results

Serologic detection using microscopic agglutination tests

Of the 124 sera tested using the MAT, 53 dogs (42.7%; 95% CI: 34.0–51.4%) were seropositive with antibody titres ranging between 1:100 and 1:800. Multiple patients were seropositive for the Bataviae (n = 12), Javanica (n = 10), Icterohaemorrhagiae (n = 10), Australis (n = 3), Ballum (n = 3), Hardjobovis (n = 3), Malaysia (n = 3), and Pomona (n = 2) serovars. The least common leptospiral serovars observed based on seropositivity were Autumnalis, Canicola, Celledoni, Copenhageni, Cynopteri, Lai, and Pyrogenes (all n = 1). All dogs were seronegative for the Djasiman, Grippotyphosa, Hebdomadis, Patoc, and Tarassovi serovars.

Molecular detection using the conventional PCR

The total molecular detection rate of leptospiral infection using the PCR was 42.7% (53/124; 95% CI: 34.0–51.4%). Among the 53 positive dogs, 17 dogs were positive for blood only, 11 dogs were positive for urine only and 25 dogs were positive for blood and urine Altogether, the positive samples were obtained from 42 whole blood and 36 urine samples.

Primer and TaqMan probe specificity

Neither LipL32(1) nor LipL32(2) were able to detect intermediate or saprophytic leptospiral strains, nor to detect other bacteria strains. The LipL32(1) primer was able to detect all pathogenic leptospiral strains with Ct values ranging from 13.04 to 29.67. LipL32(2) was unable to detect three pathogenic leptospiral strains (Table 3) and showed a higher Ct value than LipL32(1). Therefore, LipL32(1) was selected for the detection of pathogenic Leptospira spp. in whole blood and urine samples in this study.

Table 3.

Comparison of Ct values between a qPCR assay with the LipL32(1) primers and one with the LipL32(2) primers

| Group | DNA concentration (ng/μL) | LipL32(1) Ct value | LipL32(2) Ct value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive control | |||

| L. borgpetersenii serovar Ballum strain Mus 127 | 26.4 | 15.33 | 32.08 |

| L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjobovis strain 117123 | 20.6 | 17.41 | 33.36 |

| L. borgpetersenii serovar Javanica* | 8.2 | 16.22 | 36.14 |

| L. borgpetersenii serovar Javanica strain Veldrat Bataviae 46 | 41.0 | 14.35 | 33.96 |

| L. borgpetersenii serovar Tarassovi strain Perepelitsin | 16.1 | 20.54 | 36.39 |

| L. interrogans serovar Australis* | 9.9–11.9 | 15.43–15.58 | 33.78–34.38 |

| L. interrogans serovar Australis strain Ballico | 11.8 | 29.67 | N |

| L. interrogans serovar Autumnalis strain Akiyami A | 32.6 | 23.56 | N |

| L. interrogans serovar Bataviae* | 5.3–20.1 | 13.91–16.02 | 34.11–35.91 |

| L. interrogans serovar Bataviae strain Swart | 15.8 | 17.97 | 34.29 |

| L. interrogans serovar Canicola strain Hond Utrecht IV | 12.7 | 14.99 | 34.08 |

| L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain M20 | 2.5 | 17.95 | 34.44 |

| L. interrogans serovar Djasiman strain Djasiman | 11.5 | 16.20 | 35.43 |

| L. interrogans serovar Hebdomadis strain Hebdomadis | 28.4 | 16.77 | 33.91 |

| L. interrogans serovar Icterohaemorrhagiae strain RGA | 16.8 | 14.3 | 32.81 |

| L. interrogans serovar Lai strain Lai | 12.8 | 19.22 | 36.19 |

| L. interrogans serovar Pomona strain Pomona | 7.2 | 18.05 | 35.44 |

| L. interrogans serovar Pyrogenes strain Salinem | 43.3 | 21.40 | N |

| L. kirschneri serovar Cynopteri strain 3522C | 29.7 | 14.44 | 33.60 |

| L. kirschneri serovar Grippotyphosa strain Moskva V | 42.3 | 13.04 | 31.79 |

| L. kmetyi serovar Malaysia strain Bejo-ISO9 | 36.1 | 18.78 | 33.34 |

| L. weilii serovar Celledoni strain Celledoni | 13.0 | 24.15 | 40.52 |

| Non-target negative control | |||

| Bacillus spp. | 9.9 | N | N |

| Escherichia coli | 16.0 | N | N |

| L. biflexa serovar Patoc strain Patoc I | 42.9 | N | N |

| L. selangorensis ** | 8.7-14.3 | N | N |

| L. wolffii** | 6.7-19.3 | N | N |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 84.9 | N | N |

| Salmonella spp. | 41.1 | N | N |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 14.4 | N | N |

| Streptococcus spp. | 4.2 | N | N |

| No-target negative control | |||

| RNase-free water | 0 | N | N |

* - dog isolates;

** - environmental isolates; N - negative

Sensitivity analysis

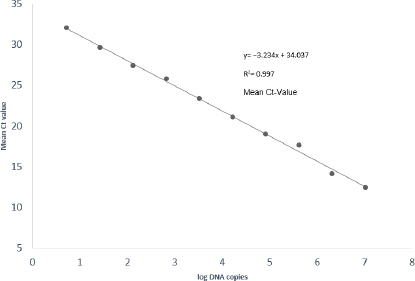

Analytical evaluation of the qPCR assay using LipL32(1) primers and respective TaqMan probe with standard control (DNA concentration 51.85 ng/μL) exhibited a linear relationship of Ct to the amount of leptospiral DNA, with a coefficient of regression (R2) value of 0.997 (Fig. 1). The qPCR assay was able to amplify approximately five DNA copies per reaction in all replicates (Table 4). The amplification factor was two (equivalent to 99.9% efficiency). The lowest and highest Ct values generated from the standard curve were 12.47 and 32.00. Therefore, samples detected within the range of 12.47 to 32.00 were confirmed positive by qPCR.

Fig. 1.

Standard curves of the TaqMan probe–based qPCR assays showing amplification of successive fivefold dilutions of Leptospira interrogans genomic DNA. R2 – coefficient of regression; Ct – cycle threshold

Table 4.

Threshold cycle (Ct) values of fivefold serial dilution of Leptospira genomic DNA in a 20 μL reaction volume

| Dilution factor | Mean DNA copy number/μL | log DNA copies | Mean Ct value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard control with DNA concentration of 51.85 ng/μL (primary stock) | 10,382,320 | 7.01629441 | 12.47 |

| 1:5 | 2,076,464 | 6.317324406 | 14.15 |

| 1:25 | 415,292.8 | 5.618354402 | 17.66 |

| 1:125 | 83,058.56 | 4.919384397 | 18.96 |

| 1:625 | 16,611.712 | 4.220414393 | 21.05 |

| 1:3,125 | 3,322.3424 | 3.521444389 | 23.36 |

| 1:15,625 | 664.46848 | 2.822474384 | 25.79 |

| 1:78,125 | 132.893696 | 2.12350438 | 27.43 |

| 1:390,625 | 26.5787392 | 1.424534376 | 29.67 |

| 1:1,953,125 | 5.31574784 | 0.725564371 | 32.00 |

Molecular detection using the qPCR

The total molecular detection rate of leptospiral infection using qPCR was 53.2% (66/124; 95% CI: 44.1–62.2%). Among the 66 positive dogs, 19 were positive for blood only, 5 were positive for urine only, and 42 were positive for blood and urine. Altogether, the positive samples were obtained from 61 whole blood and 47 urine samples.

Epidemiological sensitivity and specificity of the qPCR assay

Overall, the qPCR assay had a sensitivity of 100.00% (95% CI: 93.28–100.00%) and specificity of 81.69% (95% CI: 70.73–89.87%). Without reference to sample type, the PPV and NPV of the qPCR assay were 80.30% and 100.00% respectively, with an accuracy of 89.52%.

Detailed sensitivity and specificity of the qPCR assays for whole blood and urine

In total, 61 of the 124 (49.20%; 95% CI: 40.11–58.32%) whole blood and 47 of the 113 (41.60%; 95% CI: 32.40–51.24%) urine samples were detected as positive by qPCR. The Ct values for whole blood and urine samples ranged between 23.80 and 31.90 and 13.57 and 31.43, respectively. The qPCR assay for whole blood had a sensitivity of 100.00% (95% CI: 91.59–100.00%) and specificity of 76.80% (95% CI: 66.20–85.44%). The PPV and NPV of the blood assay were 68.90% and 100.00% respectively, with an accuracy of 84.70%. The qPCR assay for urine had a sensitivity of 100.00 % (95% CI: 90.26–100.00%) and specificity of 85.70% (95% CI: 75.87–92.65%). The PPV and NPV of the urine assay were 76.60% and 100.00% respectively, with an accuracy of 90.30%.

Discussion

In clinical diagnostic laboratories, real-time PCR methods (SYBR green and TaqMan chemistries) have gained popularity because they provide the opportunity for rapid diagnosis of leptospirosis in the first days of infection (8). To date, MAT remains the gold-standard method for diagnosis, but MAT and other serological tests are less useful if conducted during the acute phase of infection (6, 25). To improve the interpretation of the test, it is recommended to analyse paired serum samples taken at a two-week interval to confirm leptospirosis (35). In this study, 102 dogs presented with acute clinical illness, this being a phase lasting only up to one week, whereas 22 dogs were in the chronic phase. Therefore, molecular methods such as conventional and qPCRs were preferable to serological methods for the detection of the presence of Leptospira spp., especially in infected dogs in the acute phase. Nevertheless, the MAT results in this study remained important for serological evaluation (despite paired serum samples not having been collected) and the PCR results needed to be interpreted with those of the MAT to confirm leptospirosis. The molecular detection rates using the conventional PCR and the qPCRs were compared in the study.

Polymerase chain reactions allow early detection of Leptospira with high sensitivity and specificity (30). Routinely, conventional PCR has been adopted to diagnose canine leptospirosis locally (32). To date, several qPCR methods have been described in human leptospirosis, and the superior usefulness of the qPCR as a diagnostic tool was demonstrated over the conventional PCR (8, 29, 39), but the validity of this technique has not been determined. To our knowledge, this study was the first to evaluate the analytical performance of a TaqMan probe–based qPCR to detect Leptospira spp. using clinical samples from dogs diagnosed with kidney and/or liver disease.

The microscopic agglutination test is a sensitive assay, but because of the antigenic heterogeneity of Leptospira spp., the test requires many serovars as antigens (6). In this study, the overall serological detection of leptospiral infection in dogs with kidney and/or liver disease was 42.7%, which was much higher than the rate of previous local studies. The reason could likely be the specific selection of dogs to be recruited and the testing of the serum against the particular 20 leptospiral serovars selected. In comparison, one previous study investigated a larger population of apparently healthy shelter and working dogs (12), two investigated healthy dogs from a single location (16, 22) and one study was carried out among pet dogs (21). All of these studies only aimed to determine seropositivity among apparently healthy dogs using a panel of 10 leptospiral serovars, unlike in this study. The dogs recruited to this research were seropositive for 20 leptospiral serovars: Bataviae (n = 12), Javanica (n = 10), Icterohaemorrhagiae (n = 10), Australis (n = 3), Ballum (n = 3), Hardjobovis (n = 3), Malaysia (n = 3), and Pomona (n = 2) in more than one instance and for the other serovars in single instances.

Based on molecular detection with a conventional PCR, 42.7% of the dogs diagnosed with kidney and/or liver disease had leptospirosis. This result was consistent with a previous study which reported 42.4% (14/33; 95% CI: 25.6–59.3%) (28). Despite that study having a smaller sample size, the comparison is valid because the target population was similar. In contrast, a previous study reported lower molecular detection rates of 19.8% (26/131; 95%CI: 13.0–26.7%) (34) and 1.0% (1/106; 95% CI: 0.0–2.8%) (20). Despite the similarity between these studies in both having large sample sizes, this comparison must be regarded with caution because the target population recruited to that study were apparently healthy dogs. This could explain the lower detection rate reported.

This study used two qPCR assays, namely LipL32(1) and LipL32(2), and both assays showed negative detection for other microorganisms, including intermediate and saprophytic Leptospira spp. that may have been present in the clinical samples and caused nonspecific amplification. Only the LipL32(1) assay could amplify all the pathogenic leptospiral strains; its average Ct value of 16.56 indicated strong positive reactions in which abundant target nucleic acid was detected in the positive control. The LipL32(2) assay differed in efficacy, producing an average Ct value of 30.94, indicating positive reactions and a moderate amount of target nucleic acid detected in the positive control. The LipL32(1) assay had higher sensitivity than the LipL32(2) assay and therefore showed better performance in detecting pathogenic Leptospira spp. in the samples from the dogs in this study.

Analytically, the LipL32(1) assay amplified as few as approximately five DNA copies per reaction, which was close to the lowest theoretically possible LOD reported of three copies per reaction (7). The LipL32(1) assay LOD was comparable to previous molecular assays, which amplified between 1 and 10 copies per reaction (4, 5, 27, 29, 39). In terms of leptospiral coverage, another published assay that utilised a similar target showed the same results: it amplified all the pathogenic Leptospira spp. but did not amplify the intermediate and saprophytic Leptospira spp. (25).

The highest Ct value obtained from the standard curve of the LipL32(1) assay in this study was 32.00 and samples with higher values were considered negative. Theoretically, Ct values of 30.00 to 37.00 were positive reactions, but based on the analysis of the LipL32(1) assay’s standard curve, any Ct value higher than 32.00 might be associated with a nonspecific reaction or contamination from the samples. To eliminate doubtful and false-positive results, only samples which yielded Ct values ≤32.00 were considered positive in this study.

The conventional PCR showed that 42 out of 124 whole blood and 36 out of 113 urine samples were positive for pathogenic Leptospira spp. Interestingly, the qPCR had a better detection rate, where 61 out of 124 whole blood and 47 out of 113 urine samples were positive for pathogenic Leptospira spp. Although the conventional PCR and the qPCR followed similar steps, they differ enough for many advantages of the qPCR to be discernible. Assays of the qPCR type can identify amplified fragments during the PCR process. A qPCR measures the amount of the product during the exponential phase, whereas a conventional PCR measures the product during the plateau phase. It was more effective to measure during the exponential phase because measurements taken during the plateau phase do not always clearly indicate the quantity of starting material. In the plateau phase of the amplification, depleted amounts of reagents are available for the amplification (some having been consumed during the exponential phase), and the amplification inhibitors are more active during this phase. Hence, accurate measurement is not possible in conventional PCR methods (14, 24). Moreover, a conventional PCR requires post-PCR analysis using agarose gel electrophoresis, which identifies the product either by size or sequence. Although running gel electrophoresis is relatively inexpensive, it is time-consuming and non-automated. It has low specificity since molecules of the same or similar weights cannot be easily differentiated (40, 43). This may explain why the qPCR assay used had better detection of positive reactions that were quantifiable from the samples compared to the conventional PCR.

Among the 53 seropositive dogs, 30 from which whole blood was drawn and 22 from which urine was collected were positive using the qPCR assay, whereas 16 dogs sampled by whole blood and 15 dogs sampled by urine were positive using the conventional PCR. This suggests that the dogs were in the convalescent phase, when antibodies might have started to react with the antigens, potentially reducing the amount of leptospires circulating in the body, but not to such an extent that they were undetectable using the molecular method. On this assumption, the qPCR had a better ability to detect infection during the convalescent phase.

The Ct values of the qPCR for whole blood ranged between 23.8 and 31.9 and those of the assay for urine samples were 13.57 to 31.43. Similarly, a previous study revealed that the canine whole blood samples had higher Ct values than urine samples (25). It was also mentioned that the sensitivity of the LipL32 qPCR assay was 100 Leptospira spp./mL in whole blood samples, 1,000 Leptospira spp./mL in serum samples, and 10 Leptospira spp./mL in urine samples. The LipL32 qPCR assay was able to detect low amounts of pathogenic Leptospira spp. in urine samples, resulting in low Ct values, which is consistent with the findings in this study (25). Therefore, whole blood and urine samples were preferable to serum samples for the detection of the pathogenic Leptospira spp.

The whole blood and urine samples tested using the qPCR assay were 100% detectable as positive when compared to these samples tested in the conventional PCR in this study, which means that the qPCR assay developed and validated in this research correctly identified all the positive dogs diagnosed with leptospirosis using PCR (it achieved 100% sensitivity). For specificity, the whole blood and urine samples tested using qPCR were 76.83% and 85.71% detected as negative, respectively when compared to these samples tested in the conventional PCR. The PPV of both whole blood and urine was >65.00%, which signifies that among dogs that had a positive qPCR assay result, the probability of disease was more than 65.00%. The NPV for both whole blood and urine samples was 100.00% which indicates that among dogs that had a negative qPCR assay result the probability of being disease-free was 100.00%. This showed that the qPCR assay used in this study was a good test, with accuracy of more than 80.00% for screening and diagnosis of acute canine leptospirosis, especially for dogs diagnosed with kidney and/or liver disease.

In conclusion, the LipL32(1) qPCR assay is a more reliable method for the detection of pathogenic Leptospira spp. than the LipL32(2) qPCR assay because the LipL32(1) assay was able to detect all pathogenic leptospiral strains with a low CT value. In addition, the LipL32(1) qPCR assay performed better in diagnosing acute canine leptospirosis than the conventional PCR, thus hastening an informed decision on therapeutic management and improving clinical outcomes. Although this study tested a targeted dog population, the high sensitivity and specificity of the LipL32(1) qPCR assay favour the exploration of this assay in a future study with a bigger population and a larger number of clinical samples.

Acknowledgements

We thank the small animal veterinarian officers and staff at UVH, and the staff of the Bacteriology Laboratory and Biochemical Laboratory, FVM, UPM for their valuable help in taking the samples from the recruited dogs as well as laboratory assistance. We also thank the private veterinary clinics near UPM (St. Angel Animal Medical Centre and J Avenue Veterinary Clinic) for providing samples.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) with award No. FRGS/1/2016/SKK02/UPM/02/1/5524930.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests Statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this article.

Animal Rights Statement: Ethical approval of this study was obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (UPM/IACUC/AUP-R084/2016).

References

- 1.Ahmed A., Klaasen H.L.B.M., van der Veen M., van den Linden H., Goris M.G.A., Hartskeerl R.A. Evaluation of Real-Time PCR and Culturing for the Detection of Leptospires in Canine Samples Adv Microbiol. 2012;2:162. doi: 10.4236/aim.2012.22021. :. . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed S.A., Sandai D.A., Musa S., Hoe C.H., Riadzi M., Lau K.L., Tang T.H. Rapid diagnosis of leptospirosis by multiplex PCR Malays J Med Sci. 2012;19:9. : . , , –. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azocar-Aedo L., Monti G. Meta-Analyses of Factors Associated with Leptospirosis in Domestic Dogs Zoonoses Public Health. 2016;63:328. doi: 10.1111/zph.12236. : . , , –. doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedir O., Kilic A., Atabek E., Kuskucu A.M., Turhan V., Basustaoglu A.C. Simultaneous detection and differentiation of pathogenic and nonpathogenic Leptospira spp. by multiplex real-time PCR (TaqMan) assay Pol J Microbiol. 2010;59:167. : . , , –. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourhy P., Bremont S., Zinini F., Giry C., Picardeau M. Comparison of real-time PCR assays for detection of pathogenic Leptospira spp. in blood and identification of variations in target sequences J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2154. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02452-10. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budihal S.V., Perwez K. Leptospirosis diagnosis: competency of various laboratory tests J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2014;8:199. doi: 10.7860/jcdr/2014/6593.3950. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bustin S.A., Benes V., Garson J.A., Hellemans J., Huggett J., Kubista M., Mueller R., Nolan T., Pfaffl M.W., Shipley G.L., Vandesompele J., Wittwer C.T. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments Clin Chem. 2009;55:611. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esteves L.M., Bulhões S.M., Branco C.C., Carreira T., Vieira M.L., Gomes-Solecki M., Mota-Vieira L. Diagnosis of Human Leptospirosis in a Clinical Setting: Real-Time PCR High Resolution Melting Analysis for Detection of Leptospira at the Onset of Disease Sci Rep. 2018;15:9213. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27555-2. : . , , , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evangelista K.V., Coburn J. Leptospira as an emerging pathogen: a review of its biology, pathogenesis, and host immune responses Future Microbiol. 2010;5:1413. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.102. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faine S. Guidelines for the control of leptospirosis. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1982. : . , , . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fink J.M., Moore G.E., Landau R., Vemulapalli R. Evaluation of three 5’ exonuclease-based real-time polymerase chain reaction assays for detection of pathogenic Leptospira species in canine urine J Vet Diagn Invest. 2015;27:159. doi: 10.1177/1040638715571360. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goh S.H., Ismail R., Lau S.F., Megat Abdul Rani P.A., Mohd Mohidin T.B., Daud F., Bahaman A.R., Khairani-Bejo S., Radzi R., Khor K.H. Risk Factors and Prediction of Leptospiral Seropositivity Among Dogs and Dog Handlers in Malaysia Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1499. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16091499. : . , , , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene C.E., Sykes J.E., Moore G.E., Goldstein R.E., Schultz D. In: Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. Fourth Edition Greene C.E., Sykes J.E., editors. Saunders Elsevier; St. Louis, MO: 2012. Chapter 42, Leptospirosis pp. 431–447. : , in: , , edited by. , , , –. . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoy M.A. Insect Molecular Genetics: An Introduction to Principles and Application. Third Edition. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA: 2013. Chapter 8, DNA Amplification by the Polymerase Chain Reaction: Molecular Biology Made Accessible pp. 307–372. : , in: , , , –. . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorge S., Monte L.G, De Oliveira N.R, Collares T.F., Roloff B.C., Gomes C.K., Hartwig D.D., Dellagostin O.A., Hartleben C.P. Phenotypic and molecular scharacterisation of Leptospira interrogans isolated from Canis familiaris in Southern Brazil Curr Microbiol. 2015;71:496. doi: 10.1007/s00284-015-0857-z. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khor K.H., Tan W.X., Lau S.F., Roslan M.A., Radzi R., Khairani-Bejo S., Bahaman A.R. Seroprevalence and molecular detection of leptospirosis from a dog shelter Trop Biomed. 2016;33:276. : . , , –. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohn B., Steinicke K., Arndt G., Gruber A.D., Guerra B., Jansen A., Kaser-Hotz B., Klopfleisch R., Lotz F., Luge E., Nöckler K. Pulmonary abnormalities in dogs with leptospirosis J Vet Intern Med. 2010;24:1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0585.x. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koizumi N., Muto M.M., Akachi S., Okano S., Yamamoto S., Horikawa K., Harada S., Funatsumaru S., Ohnishi M. Molecular and serological investigation of Leptospira and leptospirosis in dogs in Japan J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:630. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.050039-0. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kümmerle Fraune C., Schweighauser A., Francey T. Evaluation of the diagnostic value of serologic microagglutination testing and a polymerase chain reaction assay for diagnosis of acute leptospirosis in dogs in a referral center J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;242:1373. doi: 10.2460/javma.242.10.1373. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latosinski G.S., Fornazari F., Babboni S.D., Caffaro K., Paes A.C., Langoni H. Serological and molecular detection of Leptospira spp. in dogs Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2018;51:364. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0276-2017. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau S.F., Low K.N., Khor K.H., Roslan M.A., Khairani-Bejo S., Radzi R., Bahaman A.R. Prevalence of leptospirosis in healthy dogs and dogs with kidney disease in kidney disease in Klang Valley, Malaysia Trop Biomed. 2016;33:469. : . , , –. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lau S.F., Wong J.Y., Khor K.H., Roslan M.A., Abdul-Rahman M.S., Khairani-Bejo S., Radzi R., Bahaman A.R. Seroprevalence of Leptospirosis in Working Dogs Top Companion Anim Med. 2017;32:121. doi: 10.1053/j.tcam.2017.12.001. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levett P.N., Morey R.E., Galloway R.L., Turner D.E., Steigerwalt A.G., Mayer L.W. Detection of pathogenic leptospires by real-time quantitative PCR J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:45. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45860-0. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Logan J.M., Edwards K., Saunders N. Real-time PCR: current technology and applications. Caister Academic Press; Poole: 2009. : . , , , doi: . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin P., Stanchi N., Brihuega B., Bonzo E., Galli L., Arauz M. Diagnosis of canine leptospirosis: Evaluation of two PCR assays in comparison with the microagglutination test Pesq Vet Bras. 2019;39:255. doi: 10.1590/1678-5150-PVB-5868. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller M.D., Annis K.M., Lappin M.R., Lunn K.F. Variability in results of the microscopic agglutination test in dogs with clinical leptospirosis and dogs vaccinated against leptospirosis J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:426. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.0704.x. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miotto B.A., da Hora A.S., Taniwaki S.A., Brandão P.E., Heinemann M.B., Hagiwara M.K. Development and validation of a modified TaqMan based real-time PCR assay targeting the lipl32 gene for detection of pathogenic Leptospira in canine urine samples Braz J Microbiol. 2018;49:584. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2017.09.004. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miotto B.A., Tozzi B.F., Penteado M.de S., Guilloux A.G.A., Moreno L.Z., Heinemann M.B., Moreno A.M., Lilenbaum W., Hagiwara M.K. Diagnosis of acute canine leptospirosis using multiple laboratory tests and characterisation of the isolated strains BMC Vet Res. 2018;14:222. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1547-4. : . , , , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohd Ali M.R., Mohd Safee A.W., Ismail N.H., Abu Sapian R., Mat Hussin H., Ismail N., Yean Yean C. Development and validation of pan-Leptospira Taqman qPCR for the detection of Leptospira spp. in clinical specimens Mol Cell Probes. 2018;38:1. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2018.03.001. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musso D., La Scola B. Laboratory diagnosis of leptospirosis: a challenge J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2013;46:245. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2013.03.001. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nascimento A.L., Ko A.I., Martins E.A., Monteiro-Vitorello C.B., Ho P.L., Haake D.A., Verjovski-Almeida S., Hartskeerl R.A., Marques M.V., Oliveira M.C., Menck C.F., Leite L.C., Carrer H., Coutinho L.L., Degrave W.M., Dellagostin O.A., El-Dorry H., Ferro E.S., Ferro M.I., Furlan L.R., Gamberini M., Giglioti E.A., Góes-Neto A., Goldman G.H., Goldman M.H., Harakava R., Jerônimo S.M., Junquiera-de-Azevedo I.L., Kimura E.T., Kuramae E.E., Lemos E.G., Lemos M.V., Marino C.L., Nunes L.R., de Oliveira R.C., Pereira G.G., Reis M.S., Schriefer A., Siqueira W.J., Sommer P., Tsai S.M., Simpson A.J., Ferro J.A., Camargo L.E., Kitajima J.P., Setubal J.C., VanSluys M.A. Comparative genomics of two Leptospira interrogans serovars reveals novel insights into physiology and pathogenesis J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2164. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.7.2164-2172.2004. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman S.A., Khor K.H., Khairani-Bejo S., Lau S.F., Mazlan M., Roslan A., Goh S.H. Detection and scharacterisation of Leptospira spp. in dogs diagnosed with kidney and/or liver disease in Selangor, Malaysia J Vet Diagn Invest. 2021;33:834. doi: 10.1177/10406387211024575. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabri A.R., Khairani-Bejo S., Zunita Z., Hassan L. Molecular detection of Leptospira sp. in cattle and goats in Kelantan, Malaysia after a massive flood using multiplex polymerase chain reaction Trop Biomed. 2019;36:165. : . , , –. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sant’anna R., Vieira A.S., Grapiglia J., Lilenbaum W. High number of asymptomatic dogs as leptospiral carriers in an endemic area indicates a serious public health concern Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145:1852. doi: 10.1017/S0950268817000632. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuller S., Francey T., Hartmann K., Hugonnard M., Kohn B., Nally J.E., Sykes J. European consensus statement on leptospirosis in dogs and cats J Small Anim Pract. 2015;56:159. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12328. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoddard R.A., Gee J.E., Wilkins P.P., McCaustland K., Hoffmaster A.R. Detection of pathogenic Leptospira spp. through TaqMan polymerase chain reac tion targeting the LipL32 gene Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;64:247. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.03.014. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sykes J.E., Hartmann K., Lunn K.F., Moore G.E., Stoddard R.A., Goldstein R.E. 2010 ACVIM small animal consensus statement on leptospirosis: diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment, and prevention J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:1. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0654.x. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tansuphasiri U., Chanthadee R., Phulsuksombati D., Sangjun N. Development of a duplex-polymerase chain reaction for rapid detection of pathogenic Leptospira Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006;37:297. : . , , –. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thaipadungpanit J., Chierakul W., Wuthiekanun V., Limmathurotsakul D., Amornchai P., Boonslip S., Smythe L.D., Limpaiboon R., Hoffmaster A.R., Day N.P., Peacock S.J. Diagnostic accuracy of real-time PCR assays targeting 16S rRNA and lipL32 genes for human leptospirosis in Thailand: a case-control study PLoS One. 2011;6:e16236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016236. : . , , , doi: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Villumsen S., Pedersen R., Borre M.B., Ahrens P., Jensen J.S, Krogfelt K.A. Novel TaqMan® PCR for detection of Leptospira species in urine and blood: Pit-falls of in silico validation J Microbiol Methods. 2012;91:184. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.06.009. : . , , –. , doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waggoner J.J., Balassiano I., Abeynayake J., Sahoo M.K., Mohamed-Hadley A., Liu Y., Vital-Brazil J.M., Pinsky B.A. Sensitive real-time PCR detection of pathogenic Leptospira spp. and a comparison of nucleic acid amplification methods for the diagnosis of leptospirosis PloS One. 2014;9:e112356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112356. : . , . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory Molecular Diagnostics resource – Real-time PCR Ct Values. : . https://www.wvdl.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/CTmeaninghandout.pdf.

- 43.Xu C., Loftis A., Ahluwalia S.K., Gao D., Verma A., Wang C., Kaltenboeck B. Diagnosis of canine leptospirosis by a highly sensitive FRET-PCR targeting the lig genes PLoS One. 2014;9:e89507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089507. : . , , . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]