Abstract

The genes encoding tetrachloroethene reductive dehalogenase, a corrinoid-Fe/S protein, of Dehalospirillum multivorans were cloned and sequenced. The pceA gene is upstream of pceB and overlaps it by 4 bp. The presence of a ς70-like promoter sequence upstream of pceA and of a ρ-independent terminator downstream of pceB indicated that both genes are cotranscribed. This assumption is supported by reverse transcriptase PCR data. The pceA and pceB genes encode putative 501- and 74-amino-acid proteins, respectively, with calculated molecular masses of 55,887 and 8,354 Da, respectively. Four peptides obtained after trypsin treatment of tetrachloroethene (PCE) dehalogenase were found in the deduced amino acid sequence of pceA. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the PCE dehalogenase isolated from D. multivorans was found 30 amino acids downstream of the N terminus of the deduced pceA product. The pceA gene contained a nucleotide stretch highly similar to binding motifs for two Fe4S4 clusters or for one Fe4S4 cluster and one Fe3S4 cluster. A consensus sequence for the binding of a corrinoid was not found in pceA. No significant similarities to genes in the databases were detected in sequence comparisons. The pceB gene contained two membrane-spanning helices as indicated by two hydrophobic stretches in the hydropathic plot. Sequence comparisons of pceB revealed no sequence similarities to genes present in the databases. Only in the presence of pUBS 520 supplying the recombinant bacteria with high levels of the rare Escherichia coli tRNA4Arg was pceA expressed, albeit nonfunctionally, in recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3).

Dehalospirillum multivorans is a strictly anaerobic, gram-negative bacterium, which is able to grow with tetrachloroethene (PCE) as the terminal electron acceptor for the oxidation of different electron donors (14, 15, 19). The bacterium is able to grow at the expense of H2 and PCE. Since H2 oxidation cannot be coupled to ATP synthesis via substrate level phosphorylation, the reductive dechlorination of PCE has to be the energy-generating process, probably via a chemiosmotic mechanism. Therefore, this process was referred to as PCE respiration (25).

The key enzyme of the reductive part of catabolism, PCE reductive dehalogenase, mediates in vitro the reductive dechlorination of PCE via trichloroethene to cis-1,2-dichloroethene with reduced methyl viologen as the electron donor. PCE dehalogenase was purified from the cytoplasmic fraction of D. multivorans cells (16). The enzyme contains a corrinoid as well as about eight iron atoms and eight acid-labile sulfur atoms. The corrinoid is involved in this reaction presumably as a redox-active prosthetic group, as deduced from the finding that it has to be reduced to cob(I)alamin prior to the nucleophilic attack on the carbon of PCE (13, 25). This reaction represents a completely new type of biochemical reaction. Here we describe the cloning and sequencing of the genes of the PCE dehalogenase for further characterization of the enzyme and for comparison with the genes of other proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Determination of amino acid sequences of PCE dehalogenase.

D. multivorans was grown as previously described (14). PCE dehalogenase was isolated from the organism as described elsewhere (16). The protein was treated with trypsin (22). The peptides obtained were separated by high-pressure liquid chromatography with a Grom-Sil 300 octyldecyl silane column, and the N-terminal amino acid sequences of four peptides and of PCE dehalogenase were determined by H. Weber at the Fraunhofer-Institut für Grenzflächen und Bioverfahrenstechnik (Stuttgart, Germany) or V. Nödinger at the Institut für Technische Biochemie (University of Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany).

Cloning of pceA.

The isolation of DNA from D. multivorans, restriction, DNA ligation, and other standard techniques were performed as described elsewhere (2). Plasmid DNA for cloning and sequencing was prepared with the Flexi Prep kit (Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany). Properties of plasmids used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pBluescript II SK+ | Derived from pUC19; PlaclacZ′ Apr; f1(+) origin; colE1 origin | Stratagene |

| pET 11d | Expression vector, AprlacIq; T7/lacO promoter; ColE1 origin | Stratagene |

| pLysS | Kmr; T7 lysozyme; orip15A | Stratagene |

| pUBS 520 | Derived from pACYC 177; KmrlacIqargU; orip15A | R. Mattes |

| pW3 | 1.2-kb PCR product in EcoRV site of pBluescript II SK+ | This study |

| pY179 | 6-kb EcoRI fragment of D. multivorans DNA in EcoRI site of pBluescript II SK+ | This study |

| pPCEA | PCR-generated pceA between NcoI and BamHI sites of pET 11d | This study |

| pPCEA′ | PCR-generated pceA′ (without the leader sequence) between NcoI and BamHI sites of pET 11d | This study |

| pPCEAB | PCR-generated pceAB between NcoI and BamHI sites of pET 11d | This study |

Apr, ampicillin resistance gene; Kmr, kanamycin resistance gene.

A homologous probe for pceA was generated by PCR with genomic DNA from D. multivorans as the template. The oligonucleotides (GGI GAG GTI AAG CCI TGG TT and GTC CCA IAC YTC IGT DAT RTT) were derived from the internal peptides GEVKPWFLXAYD and NITEVWDGK (Fig. 1). PCR mixtures (50 μl) for the amplification of genomic DNA contained 50 pmol of each primer, 0.1 μg of chromosomal template DNA, a 0.1 mM concentration of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, Goldstar DNA polymerase reaction buffer, and 1 mM MgCl2. The PCR program started with initial denaturing (3 min, 96°C). The addition of 0.5 U of Goldstar DNA polymerase (Eurogentech, Cologne, Germany) was followed by 29 cycles of polymerization (1 min, 45°C; 1.5 min, 72°C; 0.5 min, 95°C) and a final cycle with prolonged polymerization time (15 min, 72°C). A 1.2-kb fragment was amplified and cloned into a T-tailed vector (11) prepared from pBluescript II SK+ (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany). The resulting plasmid, named pW3, was partially sequenced. The identity of the fragment was confirmed by comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence with the peptide sequences of PCE dehalogenase.

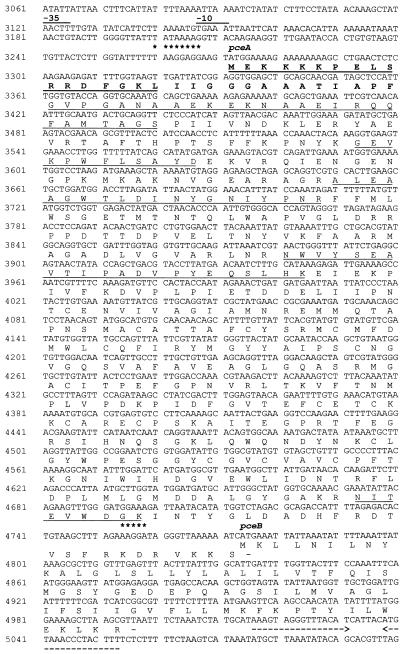

FIG. 1.

DNA sequence of the operon containing the genes for the PCE dehalogenase from D. multivorans and the deduced amino acid sequence. Putative E. coli ς70 promoter sequences (−35 and −10 regions) are overlined. A possible terminator sequence is underlined with broken arrows, and ribosome binding sites are marked with asterisks. The leader peptide is in boldface. Solid lines below the deduced amino acid sequence encoded by pceA indicate sequences also determined by Edman degradation.

Genomic DNA was digested with several restriction endonucleases. The DNA fragments generated were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nylon membrane by the capillary transfer method (21), and hybridized at 68°C with the 1.2-kb PCR product labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) by using the DIG DNA labeling and detection kit (nonradioactive) as indicated by the supplier (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). Genomic EcoRI fragments were isolated from agarose gels (Gene Clean II; Bio 101, La Jolla, Calif.), ligated into pBluescript II SK+, and transformed into E. coli DH5α cells (9). Positive clones were identified by Southern hybridization with the DIG-labeled 1.2-kb PCR product by using the DIG DNA detection kit (nonradioactive). One clone, named pY179, containing a 6-kb EcoRI fragment was used for further analyses.

DNA sequencing and analyses.

The nucleotide sequence of the 6-kb EcoRI fragment was determined by sequencing pY179 and subclones of pY179. For the sequencing reactions, an Applied Biosystems Prizm kit (Weiterstadt, Germany) was used, with subsequent electrophoresis and analyses in an Applied Biosystems A373 sequencer. Oligonucleotides (about 30 bases) were used for sequencing the remaining gaps. Both strands were independently and completely sequenced.

Computer-assisted DNA and protein sequence analyses, alignments, and hydropathic plots were performed with the software package PC/Gene (IntelliGenetics Inc., Geneva, Switzerland). Database searches were performed with BLAST (1).

RNA isolation and analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from freshly grown cells of D. multivorans grown on pyruvate and fumarate or of Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3)/pLysS/pPCEA grown on Luria broth plus 100 μM ampicillin, induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-1-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as described by the supplier. Remaining DNA was digested with DNase I (RNase free; Pharmacia) for 10 min at 37°C in an assay mixture (10 μl) containing 1 to 2 μg of RNA, 3.25 U of DNase I, 3 mM MgCl2, 2 μl of 5× first-strand buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 375 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2; Gibco BRL, Eggenstein, Germany), and 20 U of RNaseOUT (Gibco BRL). Subsequently, the mixture was incubated for 10 min at 70°C to denature the DNase I. cDNA synthesis was done with SuperScript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (RT) (Gibco BRL). The RT-PCR assay mixture (20 μl) contained 9 μl of DNA-free RNA, 20 U of RNaseOUT, 2 μl of 5× first-strand buffer, 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 2 pmol of primer, and 200 U of RT.

The Cy5-labeled primer (Pharmacia) for the primer extension method (6) was constructed complementary to the first 30 bases of pceA (TGA GAG TTC AGG CTT TTT TTT CTT TTC CAT). The length of synthesized cDNA was analyzed with an ALFex-press DNA sequencer (Pharmacia).

RT-PCR experiments were performed with RT-PCR beads (Pharmacia). Five to ten microliters of DNase-digested RNA was used as the template. The primers for cDNA and PCR are given in the Results section. The procedure was performed according to the provider’s instructions.

Expression of the PCE dehalogenase.

The coding regions of pceA and pceAB were amplified from pY179 by PCR as described above by introducing heterologous NcoI and BamHI sites. The primers for pceA were ATA GAC CAT GGA AAA GAA AAA AAA GCC TGA ACT CTC and GCA AGG ATC CTC ATG ATT TTT TAA CCC TAT CCT TTC TAA AGC; the primers for pceAB were ATA GAC CAT GGA AAA GAA AAA AAA GCC TGA ACT CTC and AGC TGG ATC CTT AAC GCT TAA GCT TTT CCC ATA AAA TAT ATG; the primers for pceA′ (pceA without the leader sequence; Fig. 1) were AAC AAC CAT GGG TGT ACC AGG TGC AAA TGC and GCA AGG ATC CTC ATG ATT TTT TAA CCC TAT CCT TTC TAA AGC. The PCR products were ligated into expression vector pET 11d between the NcoI and BamHI sites, and the vector was transformed into E. coli DH5α. Sequencing (300 bp from each side) revealed the correct position of the inserts in pPCEA, pPCEA′, and pPCEAB. Plasmids pPCEA, pPCEA′, pPCEAB, and pET 11d were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pLysS (Stratagene) or E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pUBS 520. Freshly transformed E. coli cells were used to inoculate a 50-ml overnight culture (Luria broth plus 100 μg of ampicillin per ml at 30°C). One liter of the same medium was inoculated with this culture and induced with 0.4 mM IPTG at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of between 0.5 and 0.7. Samples (250 ml) were taken at 0, 1.5, 3, and 4 h after induction, centrifuged for 15 min at 6,000 × g, suspended in 1 ml of 0.1 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) per 0.5 OD600 unit, and disrupted with a French press. The crude extracts were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–12% PAGE).

D. multivorans extracts for supplementation of the growth medium were prepared by suspending 30 g of cells (wet weight; grown on pyruvate and fumarate) in 70 ml of 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. The cells were disrupted with a French press. The crude extract was autoclaved and centrifuged for 20 min at 8,000 × g. One liter of E. coli minimal medium (8) was supplemented with 25 ml of the supernatant.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequences described in the present manuscript have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF022812.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing the PCE dehalogenase gene.

PCE dehalogenase from D. multivorans was purified from the cytoplasmic fraction of pyruvate- and fumarate-grown cells as described elsewhere (16). The N terminus of the purified protein was sequenced. It started with the amino acid glycine, indicating a posttranslational processing of the protein. In addition, the PCE dehalogenase was digested with trypsin and the amino acid sequences of four of the resulting peptides were determined (Fig. 1). Two degenerated oligonucleotides were derived from the amino acid sequences of peptides 1 and 4 (Fig. 1). A 1.2-kb fragment was amplified by PCR with genomic DNA of D. multivorans as the template. The PCR product was cloned in pBluescript, and resulting plasmid pW3 was partially sequenced. All four peptides were found in the deduced amino acid sequence encoded by the 1.2-kb fragment. Given the apparent molecular mass of 58 kDa for the PCE dehalogenase (16), it was calculated that the PCR product contained about 70% of pceA (PCE dehalogenase gene). A gene probe labeled with DIG was prepared with the PCR product as the template.

Genomic DNA from D. multivorans was digested with several restriction endonucleases, and the fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Southern blot analysis of the genomic DNA fragments with the gene probe identified an EcoRI fragment of about 6 kb containing at least part of the pceA gene. Thus, genomic EcoRI fragments of 5.5 to 6.5 kb were isolated from agarose gels, ligated into the pBluescript vector, and transformed into E. coli DH5α. Three of 200 clones hybridized with the gene probe. The plasmid of one of the positive clones, pY179, contained an EcoRI insert of about 6 kb and was used for double-strand sequencing.

Sequence analysis of the PCE dehalogenase gene.

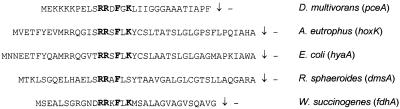

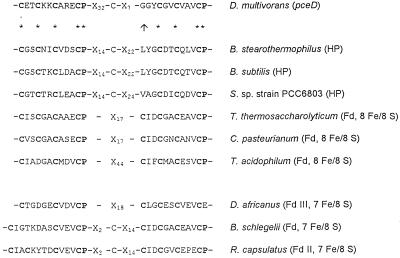

An open reading frame (ORF) coding for a protein (product of pceA) which harbors the N terminus and all four internal peptides of PCE dehalogenase was found on the 6-kb EcoRI fragment (Fig. 1). The sequence of the product of this ORF started 30 amino acids (corresponding to 90 bp of the ORF) upstream of the N terminus of PCE dehalogenase isolated from D. multivorans. In the N-terminal part of the deduced protein encoded by pceA, a putative signal sequence, RRXFXK, followed by a stretch of hydrophobic amino acids was detected (5) (Fig. 2). These findings support the assumption of a processing of the protein. During the first steps of purification of PCE dehalogenase, a protein with an apparent molecular mass of 61 kDa was copurified (Fig. 6, lane 6, band B). The N-terminal sequence of this protein was identical to the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the protein deduced from pceA, indicating that this protein was the unprocessed PCE dehalogenase. The molecular masses of the deduced 501-amino-acid protein (nonprocessed) and of the truncated 471-amino-acid protein were calculated to be 55,887 Da and 52,674 Da, respectively. Taking into consideration the fact that PCE dehalogenase contains a corrinoid and about eight iron and eight acid-labile sulfur atoms (16), the calculated size of the truncated holoenzyme (about 55 kDa) is in accordance with the apparent molecular mass of the native PCE dehalogenase determined by gel filtration (58 kDa). In the amino acid sequence deduced from pceA, consensus sequences similar to that for two Fe4S4 clusters (CXXCXXCXXXCP; 7) were identified from amino acids 365 to 377 and 420 to 428 (Fig. 1). The only difference from the consensus sequence is a glycine instead of a cysteine at amino acid position 417. A consensus sequence for the binding of a corrinoid (DXHXXG; 12) could not be detected. No other significant similarities to genes in the databases were found in sequence comparisons. In addition, no significant similarities were revealed by amino acid sequence comparisons of the pceA gene product with vitamin B12− and coenzyme B12-binding proteins performed with the software package PC/Gene.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the N terminus encoded by pceA from D. multivorans with signal peptide sequences of the small subunits of hydrogenases from Alcaligenes eutrophus and E. coli, dimethyl sulfoxide reductase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, and the large subunit of formate dehydrogenase from W. succinogenes. The data were taken from reference 5. The sequences have been aligned relative to the consensus sequence RRXFXK (in boldface). Cleavage sites are marked by arrows.

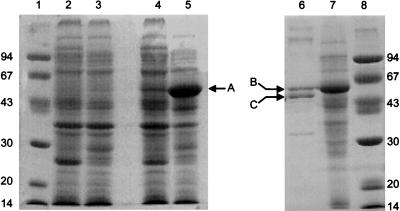

FIG. 6.

Expression of pceA from D. multivorans in E. coli BL21 (DE3) as analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Strains of E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring different plasmids were induced by IPTG. Cell extracts were analyzed by SDS–12% PAGE and subsequently stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G-250. Lane 1, molecular mass markers (molecular mass is given in kilodaltons); lane 2, E. coli/pLysS/pET 11d; lane 3, E. coli/pUBS 520/pET 11d; lane 4, E. coli/pLysS/pPCEA; lane 5, E. coli/pUBS 520/pPCEA; lane 6, PCE dehalogenase enriched from D. multivorans (fraction eluted from the phenyl Superose column; reference 16); lane 7, same as lane 5; lane 8, same as lane 1. A, pceA gene product; B and C, unprocessed and processed D. multivorans PCE dehalogenase, respectively, as confirmed by N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis.

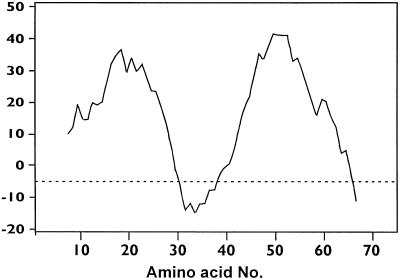

The start codon of a further ORF (pceB) overlaps by four bases the C terminus-encoding region of pceA (Fig. 1). The 74-amino-acid protein encoded by this gene (225 bp) has a calculated molecular mass of 8,354 Da. Two hydrophobic regions were detected in the hydropathic plot of this protein, indicating the presence of two membrane-spanning helices (Fig. 3). Cysteine and histidine residues were not detected in the deduced amino acid sequence of pceB. In addition, sequence comparisons revealed no significant similarities to genes present in the databases.

FIG. 3.

Hydropathic plot of the predicted amino acid sequence of pceB. The plot was obtained by using the software package PC/Gene (IntelliGenetics Inc.).

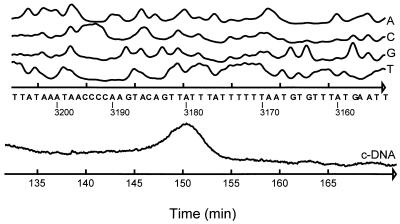

Each of the start codons of pceA and pceB is preceded by a putative ribosome binding site (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 1, there are two stretches resembling the −10 and −35 regions of an E. coli ς70 promoter, indicating a transcription start between positions 3160 and 3170. The primer extension method, with total RNA isolated from D. multivorans as the template, was used to determine that the transcription start site of the PCE dehalogenase was at approximately position 3180 (Fig. 4). In addition, RT-PCR with two different oligonucleotide pairs (pair I: positions 3162 to 3194 and 3501 to 3476; pair II: positions 3090 to 3117 and 3501 to 3476) was conducted with total RNA from D. multivorans. Only with pair I was a PCR product (size, 339 bp) obtained, indicating a transcription start between positions 3117 and 3161. Downstream of the pceB stop codon, an inverted repeat followed by a poly(T) stretch (Fig. 1), which possibly acts as a ρ-independent terminator, was detected. RT-PCR with an oligonucleotide pair (positions 4660 to 4682 and 4992 to 4967) revealed a 335-bp PCR product, indicating cotranscription of pceA and pceB (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Mapping of the pce transcription start site by the primer extension method. The primer for cDNA synthesis and sequencing of Y179 was complementary to the nucleotides at positions 3301 to 3272. Curves A, C, G, and T show the sequencing of Y179. The numbers under the bases correspond to the numbering in Fig. 1. For further details, see Materials and Methods.

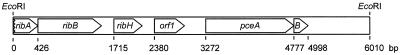

Genes upstream of the pceAB genes.

Upstream of the pceAB genes, one ORF (ORF1) with no significant sequence similarities to genes in the databases was detected. Further upstream of ORF1, three ORFs were identified as genes encoding enzymes of the riboflavin biosynthesis pathway. The first ORF (ribA) encodes the C-terminal part of a protein with the greatest sequence similarity to GTP cyclohydrolase II of Helicobacter pylori (81 of 141 amino acids identical). The two other ORFs encode proteins with sequence similarities to the 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase (ribB) of Photobacterium phosphoreum (115 of 356 amino acids identical) and to the beta subunit of the riboflavin synthase (ribH) of E. coli (81 of 156 amino acids identical). Each of the start codons of the ORFs is preceded by a putative ribosome binding site. An overview of the DNA region comprising the genes for PCE dehalogenase is given in Fig. 5.

FIG. 5.

Physical map of the DNA region comprising the genes for PCE dehalogenase. For further details, see the text.

Expression of the PCE dehalogenase genes in E. coli BL21.

The pceA gene was amplified by PCR with pY179 as the template. The PCR product was cloned in pET 11d downstream of an IPGT-inducible T7/lac promoter and transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3)/pLysS. After induction of the bacteria with 0.4 mM IPTG, neither PCE dehalogenase activity nor a protein of the molecular size of PCE dehalogenase as determined by SDS-PAGE could be detected in crude extracts. RT-PCR of RNA isolated from IPTG-induced bacteria revealed the expected DNA fragments indicating the transcription of the gene (data not shown).

Analysis of the codon usage of the D. multivorans gene in pY179 revealed that the triplet AGA coding for arginine is used much more frequently than in E. coli (data not shown). Moreover, two AGA tandems are present in pceA (positions 3302 to 3307 and 3776 to 3781 in Fig. 1). In E. coli, AGA codons are translated by the rare tRNA4Arg encoded by argU (18).

The plasmid pUBS 520 containing argU was transformed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring pceA, pceA′, or pceAB (see Table 1). After induction of the bacteria with 0.4 mM IPTG, proteins with molecular masses of 61 ± 1 kDa (pceA product) and 57 ± 1 kDa (pceA′ product) were expressed in crude extracts of the respective recombinant bacteria as determined by SDS-PAGE (shown for pceA in Fig. 6). PCE dehalogenase activity could not be detected in crude extracts of recombinant E. coli. Growth of the recombinant bacteria under anaerobic conditions or the addition of vitamin B12 or of autoclaved crude extract of D. multivorans to the medium did not result in functional expression of PCE dehalogenase.

DISCUSSION

We show here for the first time cloning, sequencing, and expression of a PCE reductive dehalogenase from gram-negative, strictly anaerobic D. multivorans. Evidence for the presence of two ORFs, designated pceA and pceB, on the PCE dehalogenase operon is presented. From the finding that a putative E. coli ς70 promoter region precedes pceA and a ρ-independent terminator structure follows the stop codon of pceB, it was concluded that the two genes form one operon. This assumption was further supported by RT-PCR experiments indicating that both ORFs are cotranscribed. ORF pceA encodes the PCE dehalogenating protein. The finding that pceB encodes a highly hydrophobic protein with two transmembrane helices suggests that the gene product might be a membrane-anchoring subunit for the attachment of the pceA gene product to the cytoplasmic membrane. This is feasible, since the PCE dehalogenase is involved in a respiratory process (13, 17). No significant similarities of the pceB product to other proteins was found in sequence comparisons. Since the amino acids histidine and cysteine were lacking in the pceB gene product, a binding of heme to the protein as in cytochromes or of Fe/S clusters is not feasible, indicating that this “subunit” is probably not involved in the electron transport chain.

In the upstream region of pceA, three ORFs (ribABH) were identified as encoding putative enzymes of riboflavin biosynthesis; one ORF could not be identified. No ORF could be detected in the 0.9-kb downstream region of pceB. Putative ribosome binding sites were detected upstream of the start codon of each gene, indicating that the genes could be expressed in D. multivorans.

From the finding that the N terminus of PCE dehalogenase was found downstream of the N terminus of the deduced pceA protein, it is concluded that the protein was modified by truncation of the first 30 amino acids in D. multivorans. The modification signal was probably the peptide RRXFXK followed by a hydrphobic stretch, which was mainly reported for periplasmic, cofactor-binding proteins (5). This is surprising, since PCE dehalogenase was recovered exclusively in the cytoplasmic fraction of D. multivorans. The only other protein containing this leader sequence and facing the cytoplasmic side of the membrane is the dimethyl sulfoxide reductase of E. coli. This enzyme was reported to contain a hydrophobic subunit, which obviously hampers the catalytically active subunits from being excreted into the periplasm (24). Hence, it is feasible that the product of pceB serves a similar function for PCE dehalogenase. Usually, the cleavage sites for these and the Sec signal peptides are preceded by two small amino acids at positions −1 and −3 (23). In the pceA gene product, this site is preceded by phenylalanine at position −1 (Fig. 2).

The deduced amino acid sequence of corrinoid-iron/sulfur protein PCE dehalogenase exhibits no significant similarities to those of other proteins, including other cobalamin-containing enzymes. In addition, the cobalamin-binding site DXHXXG described for, e.g., the cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase (3) as well as for several adenosylcobalamin-containing mutases (4, 12), could not be detected. Since there are corrinoid-containing enzymes, which also lack this binding site, e.g., the corrinoid-iron/sulfur protein of Clostridium thermoaceticum (10), the corrinoid is probably noncovalently bound to the PCE dehalogenase. Evidence based on electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) data is available for the PCE dehalogenase of Dehalobacter restrictus and shows that the cobalamin in this enzyme is a base-off corrinoid (20), suggesting that the cobalt is not coordinated with a histidine of the apoenzyme. Assuming a similar structure for the enzyme of D. multivorans, the lack of a cobalamin binding site is not surprising.

A consensus sequence very similar to that for Fe8S8 ferredoxins (two CXXCXXCXXXCP stretches; 7) was detected in the deduced amino acid sequence encoded by pceA. However, the first cysteine of the second stretch is replaced by glycine. There are three possible explanations for this finding: (i) one iron atom of an Fe4S4 cluster is not bound to the sulfur of cysteine; (ii) one of the clusters contains only three Fe atoms; (iii) one iron atom of an Fe4S4 cluster is bound to the sulfur atom of cysteine, which is not located in the cluster. EPR experiments performed with the PCE dehalogenase of D. restrictus indicated the presence of 8 Fe atoms (20). Until now, the absence of cysteine at the first position of the second stretch has never been reported for Fe/S proteins (examples are given in Fig. 7). Database research revealed a consensus of both stretches with only three other sequences, probably those of unknown proteins (Fig. 7). The elucidation of the structure of the iron-sulfur clusters will have to await EPR studies on the PCE dehalogenase of D. multivorans.

FIG. 7.

Alignment of the putative Fe/S-binding region of the PCE dehalogenase (pceA product) from D. multivorans with the corresponding regions of other Fe/S proteins. The iron-binding cysteines and the prolines are in boldface. The arrow marks the missing cysteine in the second stretch of the Fe/S-binding region of the PCE dehalogenase and of three “hypothetical proteins” (HP) in comparison to sequences of Fe8S8 and Fe7S8 ferredoxins (Fd). B. stearothermophilus, Bacillus stearothermophilus; S. sp. strain PCC6803, Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803; T. thermosaccharolyticum, Thermoanaerobacterium thermosaccharolyticum; C. pasteurianum, Clostridium pasteurianum; T. acidophilum; Thermoplasma acidophilum; D. africanus, Desulfovibrio africanus; B. schlegelii, Bacillus schlegelii; R. capsulatus, Rhodobacter capsulatus.

The high PCE concentrations detected in groundwater and soils of contaminated sites is due to extensive use of this compound as a solvent during the last 50 years. It is surprising that PCE dehalogenase has no significant homology to other proteins known so far, although it has to be assumed that the enzyme was developed from ancestors within this short period of time. The evolutionary origin of the enzyme remains to be unraveled.

The codon usage of D. multivorans differs from that of E. coli especially with respect to the arginine tRNA codons. In the genes of D. multivorans known so far, the frequency of the codon AGA is about the same as in closely related Wolinella succinogenes and about 10 times higher than in E. coli. Since AGA tandems, which often result in the formation of truncated gene products (18), are present in pceA, it was not surprising that the gene was only expressed in E. coli in the presence of pUBS 520, which supplied the recombinant bacteria with high levels of the rare E. coli tRNA4Arg for the AGA codon. Crude extracts of the recombinant E. coli did not exhibit PCE-dehalogenating activity. The protein expressed in E. coli has an apparent molecular mass of 61 kDa, which was about 4 kDa larger than that of the PCE dehalogenase isolated from D. multivorans. Therefore, it is feasible that the 61-kDa gene product is an unprocessed PCE dehalogenase. This might be one of the reasons why the 61-kDa PCE dehalogenase was not enzymatically active. Although the apparent signal peptide RRXFXK should be processed by E. coli under anaerobic conditions (17), no modification of the pceA protein occurred. A possible explanation may be that no cofactors were bound to the dehalogenase in E. coli, while only proteins containing bound cofactors are processed in the signal peptide-carrying proteins (5). We also tried to express the pceA′ gene encoding the processed protein in E. coli. Although the protein was expressed, no PCE dehalogenase activity could be detected. Possibly the corrinoid and/or the Fe/S clusters have not been incorporated in the protein. Since E. coli is not able to synthesize corrinoids, vitamin B12 was added to the growth medium of the recombinant bacteria. The finding that no activity could be detected in the crude extracts of the supplemented bacteria may be due to the possibility that D. multivorans uses corrinoid derivatives other than vitamin B12. To test this hypothesis, autoclaved crude extracts of D. multivorans were added to the growth medium supplying the recombinant E. coli with D. multivorans corrinoids. Supplementation of the medium with D. multivorans corrinoids did not result in functional expression. It is feasible that the cobalamins were not taken up by E. coli under the experimental conditions applied.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the BMBFT, and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

We gratefully acknowledge helpful discussions with J. Altenbuchner and R. Mattes (Stuttgart, Germany). The plasmid pUBS 520 was kindly provided by R. Mattes (Stuttgart, Germany).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D L. Basic alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates, Inc., and John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee R V, Johnston N L, Sobeski J K, Datta P, Matthews R G. Cloning and sequence analysis of the Escherichia coli metH gene encoding cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase and isolation of a tryptic fragment containing the cobalamin-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13888–13895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beatrix B, Zelder O, Linder D, Buckel W. Cloning and expression of the gene encoding the coenzyme B12-dependent 2-methyleneglutarate mutase from Clostridium barkeri in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1994;221:101–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berks B C. A common export pathway for proteins binding complex redox cofactors? Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:393–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boorstein W R, Craig E A. Primer extension analysis of RNA. Methods Enzymol. 1989;180:347–369. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)80111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruschi M, Guerlesquin F. Structure, function and evolution of bacterial ferredoxins. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1988;54:155–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1988.tb02741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorn E, Hellwig M, Reineke W, Knackmuss H-J. Isolation and characterization of a 3-chlorobenzoate degrading pseudomonad. Arch Microbiol. 1974;99:61–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00696222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoue H, Nojima H, Okayama H. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene. 1990;96:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90336-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu W-P, Schiau I, Cunningham J R, Ragsdale S W. Sequence and expression of the gene encoding the corrinoid/iron-sulfur protein from Clostridium thermoaceticum and reconstitution of the recombinant protein to full activity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5605–5614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchuk D, Drumm M, Saulino A, Collins F S. Construction of T-vectors, a rapid and general system for direct cloning of unmodified PCR products. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;19:1154. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.5.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marsh E N, Holloway D E. Cloning and sequencing of glutamate mutase component S from Clostridium tetanomorphum. FEBS Lett. 1992;310:167–170. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81321-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller E, Wohlfarth G, Diekert G. Studies on tetrachloroethene respiration in Dehalospirillum multivorans. Arch Microbiol. 1997;166:379–387. doi: 10.1007/BF01682983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann A, Scholz-Muramatsu H, Diekert G. Tetrachloroethene metabolism of Dehalospirillum multivorans. Arch Microbiol. 1994;162:295–301. doi: 10.1007/BF00301854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neumann A, Wohlfarth G, Diekert G. Properties of the tetrachloroethene and trichloroethene dehalogenase of Dehalospirillum multivorans. Arch Microbiol. 1995;163:276–281. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann A, Wohlfarth G, Diekert G. Purification and characterization of tetrachloroethene reductive dehalogenase from Dehalospirillum multivorans. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16515–16519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nivière V, Wong S-L, Voordouw G. Site-directed mutagenesis of the hydrogenase signal peptide consensus box prevents export of a β-lactamase fusion protein. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:2173–2183. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-10-2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schenk P M, Baumann S, Mattes R, Steinbiß H-H. Improved high-level expression system for eukaryotic genes in Escherichia coli using T7 RNA polymerase and rare argtRNAs. BioTechniques. 1995;19:196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scholz-Muramatsu H, Neumann A, Meßmer M, Moore E, Diekert G. Isolation and characterization of Dehalospirillum multivorans gen. nov. sp. nov., a tetra-chloroethene-utilizing, strictly anaerobic bacterium. Arch Microbiol. 1995;163:48–56. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schumacher W, Holliger C, Zehnder A J B, Hagen W R. Redox chemistry of cobalamin and iron-sulfur cofactors in the tetrachloroethene reductase of Dehalobacter restrictus. FEBS Lett. 1997;409:421–425. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00520-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stone K L, LoPresti M B, Crawford J M, DeAngelis R, Williams K R. Enzymatic digestion of proteins and HPLC peptide isolation. In: Matsudaira P T, editor. A practical guide to protein and peptide purification for microsequencing. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1989. pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Heijne G. A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4683–4690. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiner J H, Bilous P T, Shaw G M, Lubitz S P, Frost L, Thomas G H, Cole J A, Turner R J. A novel and ubiquitous system for membrane targeting and secretion of cofactor-containing proteins. Cell. 1998;93:93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wohlfarth G, Diekert G. Anaerobic dehalogenases. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1997;8:290–295. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(97)80006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]