Abstract

Objectives:

Workplace violence is a major issue in society, business and healthcare settings. It adversely affects both employee safety and their ability to provide healthcare services.

Aim:

This study examined the association between workplace violence, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction and turnover intention among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

We collected data from 513 nurses. We conducted ‘Process Macro’ analysis. Firstly, we included three mediators in the model: job satisfaction, workplace violence and emotional exhaustion. Secondly, we used work hours and anxiety as moderators of the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention.

Results:

The findings revealed statistical significance that job satisfaction and workplace violence mediated the relationship between emotional exhaustion and nurse turnover intentions. Work hours and anxiety also moderated the relationship between workplace violence and nurses’ turnover intention.

Conclusion:

Respondents indicated that they were most affected by verbal violence during this time. Workplace violence is a negative factor that affects nurses’ work, affecting them physically and psychologically. This occupational risk should be considered when evaluating nurses exposed to violence, as it affects job satisfaction and turnover intentions. The main theoretical contribution of this research is the identification of the association between workplace violence, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction and turnover intention among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is clear that the research findings will be useful for healthcare professionals. The findings may have practical implications for healthcare administrators and their staff.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, nurses, turnover intention, workplace violence

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, a globally important disease for public health, adversely affected every aspect of life worldwide (Pak, et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that the world needs nurses more than ever (Omidi et al., 2023). Nurses play an important role in infection prevention, infection control, isolation, public health, disasters, epidemics and pandemics (Smith et al., 2020). Between life and survival, nurses risked their lives during the pandemic while performing their duties. They were afraid of becoming infected or unknowingly infect others (Mo et al., 2020). Nurses, a large community of health workers working in the COVID-19 pandemic, had spent weeks diagnosing, treating and caring for patients with limited resources (Newby et al., 2020). Due to the rising COVID-19 patient population, lack of specific therapeutic medications, increased workload, scarcity of personal protective equipment, rapid spread of positive COVID-19 cases and rising death news in the media, healthcare workers were at risk for developing mental health issues and other mental health symptoms (Lai et al., 2020). Patients or their families sometimes act violently in such challenging and high-risk settings. Loss of motivation, job dissatisfaction, emotional exhaustion and even termination of employment have been caused by violence. In response to the violent behaviour towards healthcare workers, there may be emotional burnout, lower job satisfaction, a decline in the standard of patient care, a deterioration of the work environment, an increase in occupational injuries, turnover and a decrease in the population’s use of healthcare services (Castellón, 2011; İlhan, 2010; Zapf, 1999).

Workplace violence is one of the most complex and dangerous occupational hazards for healthcare employees (McPhaul and Lipscomb, 2004; Lanctôt and Guay, 2014; Li et al, 2019). According to the International Labor Organization (1998) report, it occurs everywhere in the world. Studies (Ayrancı, 2005; Magnavita and Heponiemi, 2012; Khoshknab et al, 2015; Lafta and Falah, 2019; Sun et al, 2017) show that healthcare employees are exposed to psychological and/or non-physical violence in the workplace. Victims also suffer the negative effects (Abed et al., 2016).

Violence in healthcare organisations can lead to a number of problems, including a decline in the quality of care provided, deterioration of the workplace, employees leaving the profession, which limits the availability of healthcare services to the general population, a negative impact on recruitment to the health professions, perpetuation of unacceptable social behaviours, an increase in healthcare costs and a decline in staff health (Kingma, 2008).

Several countries have reported violence against nurses in the workplace, including the Czech Republic and Slovakia (Tomagová et al., 2020), Australia (Dafny, 2020), Taiwan (Han et al., 2017; Pai and Lee, 2011), Saudi Arabia (Alkorashy and Al Moalad, 2016; Alyaemnia and Alhudaithib, 2016), Turkey (Çelik et al., 2007; Pinar et al., 2017), Pakistan (Shahzad and Malik, 2014), Australia (Hinchberger, 2009), China (Kwok et al., 2006), Hong Kong (Cheung and Yip, 2017; Kwok et al., 2006), in Iran (Esmaeilpour et al., 2011), Switzerland (Hahn et al., 2010), Malaysia (Alam and Mohammad, 2010), and Jordan (Rayan et al., 2016) at different times. Researchers results are mixed. For example, Tomagová et al. (2020) found that aggression by patients in the Czech Republic and Slovakia increased the nurse’s psychological problems. Han et al. (2017) found that workplace violence (WPV) adversely affected nurses on physical, psychological, social, personal and professional levels. According to Alyaemnia and Alhudaithib (2016), employees were exposed to verbal and physical violence in the last year. Finally, Hahn et al. (2010) found that nurses experienced patient and visitor violence, and there were no formal procedures for patient and visitor violence.

The aim of this study was to (1) examine nurses’ experiences of workplace violence (incidence, sources and reporting of workplace violence) in healthcare organisations and (2) examine the relationship between workplace violence, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction and turnover intention among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. This study provides a new perspective for managers and healthcare providers. It also provides information for policymakers to deal with violence.

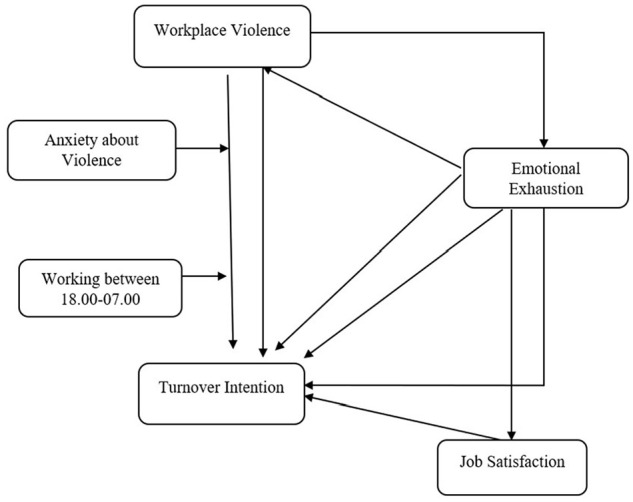

The theoretical framework underlying this study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of the research.

Conceptual development

Workplace violence against nurses in healthcare employees

Workplace violence against healthcare employees, especially nurses, is a major problem in healthcare organisations around the world. According to studies, most nurses have experienced a violent incident in the past 12 months (Alkorashy and Al Moalad, 2016; Al-Omari, 2015; Alyaemnia and Alhudaithib, 2016; Esmaeilpour et al., 2011; Hahn et al., 2010; Pınar and Uçmak, 2011). Violence can be physical, sexual, psychological or related to deprivation of something (WHO, 2002). Nurses are often in the front line of service delivery and are considered to be the most likely personnel for verbal or physical violence (Lawoko et al., 2004). In addition, studies (AbuAlRub and Al-Asmar, 2014; ; Albashtawy and Aljezawi, 2016,Cheung and Yip, 2017; Jackson and Ashley, 2005) have shown that most nurses have been exposed to verbal abuse in the workplace. Violence can come from various sources within healthcare organisations. Studies (AbuAlRub and Al-Asmar, 2014; Albashtawy, 2013; Ayrancı, 2005; Babiarczyk et al., 2020; Bawakid et al., 2017; Boafo and Hancock, 2017; Boafo et al., 2016; Çelik et al., 2007; Cheung and Yip, 2017; Cheung et al., 2018; El-Hneiti et al., 2020; Esmaeilpour et al., 2011; Gates et al., 2006; Havaei et al., 2020; Khoshknab et al., 2015; Kowalenko et al., 2013; Lafta and Falah, 2019; Özcan and Bilgin, 2011; Mento et al., 2020; Pınar and Uçmak, 2011) showed that the most common perpetrators were patients and/or patients’ relatives.

WPV is a growing problem for healthcare providers, and its effects on the mental and physical health of staff are becoming more problematic (Baydın and Erenler, 2014). AlBashtawy and Aljezawi (2016) found that most of the reasons for violence from the nurses’ perspective were waiting times, overcrowding and failure to meet the expectations of patients and families. Baydın and Erenler (2014) found the reasons for WPV to be lack of prevention measures, inadequate training and unwillingness to report assaults due to staff viewing violence as routine and not meeting the expectations of patients and their families. Hahn et al. (2010) found that violence by patients and visitors is stressful for nurses. In addition, studies (Baydın and Erenler, 2014; Budd et al., 1996; Cheung et al., 2018; El-Hneiti et al., 2020; Heponiemi et al., 2014; Hesketh et al., 2003; Shahzad and Malik, 2014; Zhao et al., 2018) showed that workplace violence affects and reduces job satisfaction of healthcare employees, especially nurses. However, some studies (Boafo et al., 2016; Shahzad and Malik, 2014) have found that violence is not reported by those who have suffered it. Generally, they believe that reporting is useless, and no action is taken. On the other hand, studies (AbuAlRub and Al-Asmar, 2014; Al-Omari, 2015; Çelik et al., 2007; Hesketh et al., 2003; Pınar and Uçmak, 2011) found that the majority of participants stated that their employers do not have policies against psychological violence in the workplace.

The mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention

In any industrial environment, the work of employees plays an important role in the success of the company. Therefore, employee job satisfaction is one of the most studied job attitudes and one of the most important research areas for many researchers (Alam and Mohammad, 2010). Job satisfaction is defined as “the positive and negative feelings of an employee towards their job or it is the amount of happiness connected with the job” (Singh and Jain, 2013: 105). While the concept addresses many factors that reveal feelings of satisfaction, it also expresses employees’ attitudes and feelings about their jobs. According to Aziri (2011), a positive attitude towards work indicates job satisfaction, whereas a negative attitude towards work indicates dissatisfaction. Job satisfaction increases effectiveness and productivity (Eliyana et al., 2019), whereas it also influences turnover behaviour. Turnover intention is defined as a likelihood of an employee to leave the current job they are doing (Ngamkroeckjoti et al., 2012). The higher employees’ satisfaction, the lower their intention to leave the organisation (Chen, 2006). Promoting job satisfaction, work ability and a violence-free environment can reduce employees’ intention to leave the job or profession (Bordignon and Monteiro, 2019). Its significance is evident when considering how job satisfaction promotes employee engagement and reduces absenteeism and occupational injuries (Aziri, 2011).

Poor job satisfaction becomes a physical and mental illness with negative personal consequences, leads to deterioration of family and social life and negatively affects organisational outcomes (Maslach et al., 2001). Job satisfaction, which reflects a person’s positive attitude towards his or her job, influences intention to leave (Randhawa, 2007). Studies (Carsten and Spector, 1987; Maslach et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2018) show that there is a negative relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention. In addition, studies (Ducharme et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2021; Kwon et al., 2021) show that emotional exhaustion, which generally describes a state of mental fatigue, has a significant negative relationship with job satisfaction and a significant positive relationship with turnover intention, suggesting a relationship. Roche et al. (2010) found that the level of emotional exhaustion of nurses in Australia was related to their intention to leave. In the study by Kelly et al. (2021), a one unit increase in nurses’ emotional exhaustion level was found to increase turnover by 12%. A study by Kim et al. (2019) found that nurses who were dissatisfied with their jobs showed higher levels of workplace bullying, exhaustion and turnover intention. Given this discussion, our study will test the following hypothesis (see relationship in Figure 1):

H1: The job satisfaction mediates the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention.

The mediating effect of workplace violence on the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention

Healthcare professionals see violence as an occupational hazard, while it is perceived as a neglected, underreported and troubling act in the workplace. The prevalence of violence in the healthcare sector varies by job description, job duration, education level, work unit and severity of patient illness (Olashore et al., 2018). The frequency with which healthcare employees are exposed to violence is quite high. While physicians and nurses are exposed to similar levels of verbal violence, nurses are more frequently exposed to physical, sexual and psychological violence (Sahip Karakaş et al., 2021). Additionally, violence that seriously endangers the physical and mental well-being of healthcare employees has a negative effect on workplace behaviour (Al-Omari, 2015; Luo and Wu, 2003). While it is known that the prevalence of violence varies by country, there are cases where this situation reaches a global level (Belayachi et al., 2010; Fute et al., 2015; Park et al., 2015).

Moreover in a study by Yeun and Han (2016) it was also found that emotional exhaustion was one of the most important factors for turnover intention. In another study by Kelly et al. (2021), nurses’ exhaustion was found to have a significant effect on turnover. Finally, the study by Havaei et al. (2016) found that higher levels of emotional exhaustion among nurses were associated with intent to leave, and workload was the most frequently cited reason for intent to leave.

Studies (Boafo et al., 2016; Boafo and Hancock, 2017; Duan et al., 2019; Heponiemi et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2020; Laeeque et al., 2018; Li et al.,2019, 2020; Liu et al., 2018; Roh and Yoo, 2012; Shahzad and Malik, 2014; Zhao et al., 2018) examined the effects of workplace violence on nurses’ turnover intentions and found that workplace violence significantly affects nurses’ turnover intentions. Accordingly, the frequency of violence increases the fear of violence among healthcare employees, and this influences turnover intention (Akbolat et al., 2018). In the study conducted by Jeong and Kim (2017), it was found that 61% of nurses who were exposed to violence thought of leaving the hospital. In the study conducted by Li et al. (2020), violence was found to have a positive effect on the intention to leave the hospital. Violence was found to significantly increase the intention of Chinese nurses to leave their jobs, according to a study by Zhao et al. (2018). We suggest testing the following hypothesis (see relationship in Figure 1) in light of this evaluation:

H2: Workplace violence mediates the relationship between emotional exhaustion and the turnover intention.

The mediating effect of emotional exhaustion on the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention

Employees have high levels of stress as they are at the forefront of combating this epidemic worldwide (Burdorf et al., 2020). Emotional exhaustion has been identified as a potential stressor by some researchers (Stordeur et al., 2001). Employees who are emotionally exhausted frequently believe they lack adaptable resources and are unable to contribute more to their work. The energy they need to do their job is depleted, and they become unable to do their job (Halbesleben and Buckley, 2004). The presence of emotional exhaustion in public healthcare can have negative consequences, not only for the concerned staff and patients but also for society (López-Cabarcos et al., 2019). Bawakid et al. (2017) found that pressure/violence by patients was one of the most important predictors of high emotional exhaustion. According to ILO (1998) report, workplace violence occurs all over the world. It is one of the most complex and dangerous occupational hazards for healthcare employees (Lanctôt and Guay, 2014; Li et al., 2019; McPhaul and Lipscomb, 2004). Studies (Bernaldo-De-Quirós et al., 2015; Chen, et al., 2016; Duan et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019; Pai et al., 2015) found that emotional exhaustion was significantly and positively associated with workplace violence. According to Bernaldo-De-Quirós et al.’s (2015) study, those in the health professions who had experienced verbal aggression had a significantly higher rate of emotional exhaustion than those who had not. According to Coşkun Cenk’s (2019) study of ambulance workers, those who had experienced verbal abuse reported feeling more worn out than others. Kim et al. (2018) concluded from their study with nurses that workplace violence mediates the relationship between emotional labour and occupational exhaustion.

In a study looking at how violence affects exhaustion in the medical field, it was discovered that physicians who experienced verbal and physical abuse scored statistically significantly higher on measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation (Teke Yaşar and Aygün, 2020). Converso et al. (2021) examined the relationship between exposure to violence, work ability and depersonalisation in their study and found significant differences in work ability, emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation between healthcare employees who were exposed to violence and those who were not. Those exposed to workplace violence showed higher levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation. In another study by Arshadi and Shahbazi (2013), emotional exhaustion was found to mediate the relationship between workplace characteristics and turnover intention. With this in mind, we hypothesise the following (see relationship in Figure 1):

H3: The emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention.

The moderating effect of work hours on the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention

The uninterrupted and continuous service provided around the clock distinguishes the health sector from other sectors. In this system, healthcare workers who work in shifts are exposed to and experience violence (Nalbant, 2006). In particular, nurses are more likely to experience situations of violence through their interactions with patients, their families and other healthcare professionals (Kim et al., 2018). In addition, the level of violence experienced by nurses in different units of the same hospital varies by unit. According to Boafo and Hancock (2017), violence is a factor that affects nurses’ intention to leave the hospital.

Research by Gieter et al. (2011) shows that nurses who work fewer hours have a stronger intention to leave the hospital. In another study by Akbolat et al. (2018), it was found that most violence occurred between 18.00 and 09.00 (68.8%). According to Fujita et al. (2012), the effect of long working hours on long-term care in hospitals leads to an increase in exposure to violence. Therefore, we proposed to test the following hypothesis (see relationship in Figure 1):

H4: Working hours between 6 pm and 7 am moderates the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention.

The moderating effect of fear of violence on the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention

Healthcare organisations are among the highest risk workplaces in terms of violence (Yılmaz, 2020). The increase in violence leads to consequences such as fear, discomfort, anxiety, desire to be hired, relocation and leaving the institution (Al et al., 2012). Boafo, Hancock and Gringart (2016) stated that identifying the incidence of workplace violence is a necessary step to address the problem.

In the study conducted by Yılmaz (2020), it was found that there is a linear relationship between the level of employee anxiety and the rate of exposure to violence. While the rate of exposure to violence among those who reported not being anxious was 63.2%, the rate of exposure to violence among those who reported being very anxious was 94.4%. In another study conducted by Gökçe and Dündar (2008) with nurses, a significant relationship was found between high levels of anxiety and experience of violence. Violence experience significantly increased the trait anxiety score.

Ma et al. (2022), in their study examining the level of fear of violence, which can be categorised as one of the stressors of the work environment, among emergency medical services personnel, found that the level of experience of violence influenced the intention to leave the workplace. Yang et al. (2021) reported that Chinese healthcare employees who were exposed to violence despite their efforts and struggles during the epidemic COVID-19 had high levels of turnover intention. McKay et al. (2020) found that the level of violence experienced by healthcare employees during the pandemic was an important risk factor for turnover intention. Based on this evaluation, we hypothesised the following (see relationship in Figure 1):

H5: Anxiety about violence moderates the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention.

Methods

Data and sampling

All participants were asked to complete survey questionnaires measuring workplace violence, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction and turnover intention among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were collected from 513 nurses in Ankara, Turkey. The study was ethically approved by the Ankara University Hacı Bayram Veli Ethics Committee dated 02 December 2020 and number 12. A Supplemental material is available containing document characteristics of the coded papers. To prevent possible language problems, the questionnaire was translated into Turkish by the research team using the back-translation method. Permission was obtained for the items used in the questionnaire. Data collection took place during the months of September 2020 to February 2021. SPSS was used for data analysis in the study. ‘Process Macro’ (Hayes, 2017), which works with the infrastructure of the statistical package, was used to analyse the obtained data. Process Macro analysis is based on a set of conceptual and statistical diagrams identified by the model number. The individual chooses a pre-programmed model that corresponds to the model they want to predict in their study. Data about which variables serve which roles in the model (e.g. independent variable, dependent variable, mediator, moderator, Sobel test, and covariate), t and p values, confidence intervals and the result of various other statistics are given by this method. Contrary to the structural equation model in Process Macro analysis, it is possible to produce statistical results with less effort (Hayes et al., 2017).

‘Bootstrap Model 1’ analysis was performed for the moderating effect and ‘Bootstrap Model 4’ analysis with confidence intervals was performed for the mediating effect. These analyses are used to test hypotheses about the differentiation of the cause–effect relationship between two variables with the levels of a third variable (Hayes et al., 2017). Based on limited assumptions, these calculations are clearer to understand and very easy to use. It also enables researchers to test hypotheses with the confidence intervals mentioned (Takma and Atıl, 2006).

Measurement scale

The data questionnaire consisted of four sections. The first section of the questionnaire included employee demographic characteristics (gender, age, marital status and education level). Secondly, the study used the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire developed by Weiss et al. (1967) to measure employee job satisfaction. The short form of the scale consisted of 20 items and included three dimensions: intrinsic satisfaction, extrinsic satisfaction and general satisfaction (Weiss et al., 1967). The third part included verbal abuse. The Workplace Violence in the Health Sector Country Case Studies Research Instruments Survey Questionnaires (English version) from the ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI project were used to measure verbal abuse. Fourth, emotional exhaustion was assessed using a nine-item measure developed by Maslach and Jackson (1981). The coefficient alpha for this nine-item measure was 0.92, which is considered acceptable. Finally, turnover intention was measured by three items developed by Cammann et al. (1979). A reliability analysis was conducted for the three-item measure, and the results showed good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74; Table 1).

Table 1.

Reliability assessment of the variables included in the scale.

| Job satisfaction | Cronbach’s alpha | Items |

| 0.929 | 20 | |

| Emotional exhaustion | Cronbach’s alpha | Items |

| 0.922 | 9 | |

| Turnover intention | Cronbach’s alpha | Items |

| 0.749 | 3 | |

| Workplace violence | Cronbach’s alpha | Items |

| 0.704 | 3 |

Statistical analysis

Before testing the hypotheses, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and Durbin–Watson coefficients should be checked in order to understand whether there is a multicollinearity problem in the independent variables. If there is a relationship between the independent variables in the same hypothesis, it creates the problem of multicollinearity. Therefore, the VIF value must be less than 10, and the tolerance value must be greater than 0.20. In addition, it is important that the Durbin–Watson coefficient is greater than 1.5 and less than 2.5 in order to avoid the multicollinearity problem (Büyüköztürk, 2018). In the analyses, it is seen that the Durbin–Watson coefficient is in the range of 1.581–1.844, the tolerance is in the range of 0.622–0.901 and the VIF value is in the range of 1.764. Therefore, it is concluded that the values are within the appropriate ranges.

Findings

Demographic characteristics of respondents

All participants (n = 513) in the study were nurses. Descriptive statistics of the sample demographics reveal that 82.1% of the respondents (N = 421) were female, 51.9% were single, fewer than half held a bachelor’s degree (42.7%) and respondents worked mainly day and night shift (64.9%). About 29.8% and 38.2% of respondents had worked for 1–5 years and more than 11 years, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of respondents.

| Characteristics | Number | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 421 | 82.1 |

| Male | 92 | 17.9 |

| Age | ||

| Age 25 and under | 179 | 34.9 |

| 26–30 | 94 | 18.3 |

| 31–35 | 67 | 13.1 |

| 36–40 | 76 | 14.8 |

| 41–50 | 97 | 18.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 247 | 48.1 |

| Single | 266 | 51.9 |

| Working time in the profession | ||

| Less than 1 year | 82 | 16.0 |

| 1–5 years | 153 | 29.8 |

| 6–10 years | 82 | 16.0 |

| 11 years and above | 196 | 38.2 |

| Education level | ||

| High-school degree | 134 | 26.1 |

| Associate degree | 123 | 24.0 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 219 | 42.7 |

| Postgraduate degree | 37 | 7.2 |

| Working between 18.00 and 07.00 | ||

| Yes | 333 | 64.9 |

| No | 180 | 35.1 |

| Level of anxiety about violence (1: not at all anxiety–5: to very anxiety) | ||

| Level 1 | 67 | 13.1 |

| Level 2 | 76 | 14.8 |

| Level 3 | 151 | 29.4 |

| Level 4 | 87 | 17.0 |

| Level 5 | 132 | 25.7 |

| Verbal violence (in the last 12 months) | ||

| Yes | 233 | 45.4 |

| No | 280 | 54.6 |

| Total | 513 | 100.0 |

About 25.7% of participants were very concerned about violence; they were most exposed to verbal violence; 45.4% reported being exposed to verbal violence in the past 12 months. In addition, it showed that 19.7% of verbal violence was committed by patients’ relatives, 38.8% of nurses considered the incident as typical violence and 36.3% indicated that it was a preventable event.

As a result of the Sobel test performed to determine the significance of the mediating effect in Table 3, the indirect effect was found to be significant (Sobel z = 3.130, p = 0.001). In addition, the Bootstrap results confirmed the results of Sobel’s test (0.037; 0.153) as the confidence intervals did not contain zero at the 95% significance level. When the results of the mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention were examined, emotional exhaustion was found to have a total (β = 0.731, t = 18.795, p = 0.000), indirect (β = 0.091, p = 0.001) and direct (β = 0.639, t = 13.308, p = 0.000) effect. If the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable remains significant when the effect of the mediating variable is controlled, but its strength decreases, this can be interpreted as a partial mediation effect. These results suggest that job satisfaction of healthcare employees has a partial mediating effect on the relationship between emotional exhaustion and intention to leave.

Table 3.

Analysis of mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention with Sobel test.

| Model for Testing Mediation | β | SE | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The direct effect of emotional exhaustion on turnover intention through mediator job satisfaction | 0.639 | 0.048 | 13.308 | 0.000 | ||

| The effect of emotional exhaustion on job satisfaction | −0.485 | 0.028 | −16.819 | 0.000 | ||

| The effect of job satisfaction on turnover intention | −0.188 | 0.059 | −3.191 | 0.001 | ||

| Total effect of emotional exhaustion on turnover intention | 0.731 | 0.038 | 18.795 | 0.000 | ||

| Effect | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | z | p | |

| Bootstrap effect and Sobel test | 0.091 | 0.029 | 0.037 | 0.153 | 3.130 | 0.001 |

According to Table 4, the indirect effect was found to be significant in the Sobel test conducted to determine the significance of the mediating effect (Sobel z = 2.333 p = 0.019). In addition, the Bootstrap results were found to support the results of the Sobel test (0.006; 0.056) as the confidence intervals did not contain zero at the 95% significance level. When examining the results of the mediating effect of workplace violence on the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention, emotional exhaustion was found to have a total (β = 0.731, t = 18.795, p = 0.000), indirect (β = 0.030, p = 0.019) and direct (β = 0.701, t = 17.295, p = 0.000) effect that was found to be significant. These results suggest that workplace violence has a partial mediating effect on the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention among healthcare employees.

Table 4.

Analysis of mediating effect of workplace violence on the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention with Sobel test.

| Model for Testing Mediation | β | SE | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The direct effect of emotional exhaustion on turnover intention through mediator workplace violence | 0.701 | 0.040 | 17.295 | 0.000 | ||

| The effect of emotional exhaustion on workplace violence | 0.059 | 0.008 | 7.037 | 0.000 | ||

| The effect of workplace violence on turnover intention | 0.503 | 0.201 | 2.497 | 0.012 | ||

| Total effect of emotional exhaustion on turnover intention | 0.731 | 0.038 | 18.795 | 0.000 | ||

| Effect | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | z | p | |

| Bootstrap effect and Sobel test | 0.030 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.056 | 2.333 | 0.019 |

As a result of the Sobel test conducted to determine the significance of the mediating effect in Table 5, the indirect effect was found to be significant (Sobel z = 6.508, p = 0.000). In addition, the Bootstrap results were found to support the Sobel test results (0.723; 1.391) as the confidence intervals did not contain zero at the 95% significance level. When the results of the mediating effect of emotional exhaustion on the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention were examined, it was found that the effect of workplace violence was significant total (β = 1.540, t = 6.357, p = 0.000), indirect (β = 1.036, p = 0.000) and direct (β = 0.503, t = 2.497, p = 0.012). These results suggest that healthcare employees’ emotional exhaustion has a partial mediating effect on the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention.

Table 5.

Analysis of mediating effect of emotional exhaustion on the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention with Sobel test.

| Model for Testing Mediation | β | SE | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The direct effect of workplace violence on turnover intention through mediator emotional exhaustion | 0.503 | 0.201 | 2.497 | 0.012 | ||

| The effect of workplace violence on emotional exhaustion | 1.477 | 0.210 | 7.037 | 0.000 | ||

| The effect of emotional exhaustion on turnover intention | 0.701 | 0.040 | 17.295 | 0.000 | ||

| Total effect of workplace violence on turnover intention | 1.540 | 0.242 | 6.357 | 0.000 | ||

| Effect | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | z | p | |

| Bootstrap effect and Sobel test | 1.036 | 0.159 | 0.723 | 1.391 | 6.508 | 0.000 |

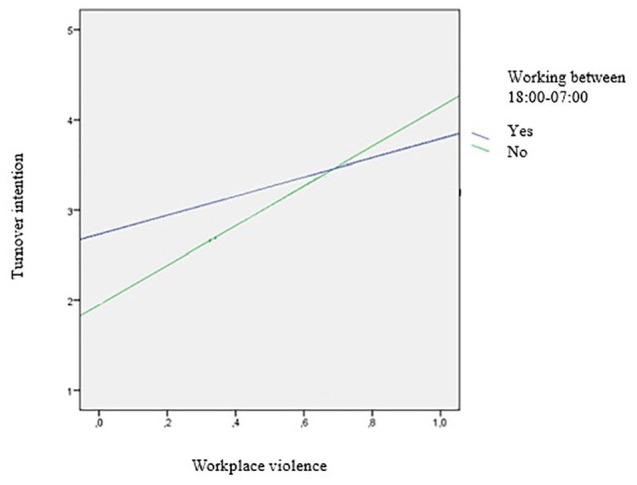

The analysis results in Table 6 show that the moderation effect of workplace violence on turnover intention was significant (R = 0.312, R2 = 0.097, F = 18.319, p = 0.000). The fact that the multiplicative result of the interaction (workplace violence × working between 18.00 and 07.00) was significant (p = 0.032) indicates that there was an interaction effect of these two variables on turnover intention, that is, working between 18.00 and 07.00 had a moderation effect. In addition, the interaction term was found to be significant because the bootstrap lower limit of the confidence interval (0.095) and the bootstrap upper limit of the confidence interval (2.196) did not contain zero at the 95% significance level. The non-significant effect of the moderator variable on the dependent variable in the analyses means a complete moderator (Aksu et al., 2017: 217). According to these results, working hours between 18.00 and 07.00 had a complete effect on workplace violence of nurses on turnover intention.

Table 6.

Analysis of the moderating effect working between 18.00 and 07.00 on the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention.

| Model for Testing Moderation | β | SE | t | p | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: TI | ||||||

| Constant | 3.519 | 0.366 | 9.597 | 0.000 | 2.798 | 4.239 |

| Workplace violence | −0.091 | 0.735 | −0.123 | 0.901 | −1.536 | 1.353 |

| Working between 18.00 and 07.00 | −0.786 | 0.252 | −3.114 | 0.001 | −1.282 | −0.290 |

| Int_1 Workplace violence × Working between 18.00 and 07.00 | 1.146 | 0.534 | 2.142 | 0.032 | 0.095 | 2.196 |

| Moderating variable: Working between 18.00 and 07.00 | ||||||

| 1 | 1.054 | 0.291 | 3.618 | 0.000 | 0.482 | 1.627 |

| 2 | 2.200 | 0.448 | 4.908 | 0.000 | 1.320 | 3.081 |

| R = 0.312; R2 = 0.097; F = 18.319; p = 0.000 | ||||||

BootLLCI: bootstrap lower limit of confidence interval, BootULCI: bootstrap upper limit of confidence interval; Int_1: interaction term; TI: turnover intention; SE: standard error.

In the Figure 2, it is seen that as the workplace violence of nurses that working between 18.00 and 07.00 turnover intention increases. This result is the same for nurses who working except 18.00-07.00. These results show that the moderator variable ‘work between 18.00 and 07.00’ had a significant effect on the relationship between workplace violence and nurses’ turnover intention (p = 0.000).

Figure 2.

The moderating role of working between 18.00 and 07.00 on the relationship between workplace violence on turnover intention.

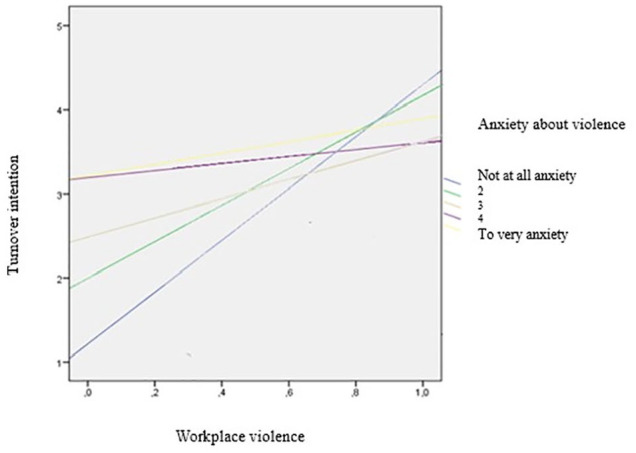

Table 7 shows that the moderator effect of workplace violence on turnover intention was significant (R = 0.416, R2 = 0.173, F = 35.647, p = 0.000). The fact that the multiplicative result of the interaction (workplace violence × anxiety of violence) was significant (p = 0.012) indicates that there was an interaction effect of these two variables on turnover intention, that is, anxiety about violence had a moderating effect. Furthermore, the interaction term was found to be significant because the bootstrap lower limit of the confidence interval (−0.857) and the bootstrap upper limit of the confidence interval (−0.105) did not contain zero at the 95% significance level.

Table 7.

Analysis of the moderating effect anxiety about violence on the relationship workplace violence on turnover intention.

| Model for Testing Moderation | β | SE | t | p | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: TI | ||||||

| Constant | 1.097 | 0.317 | 3.460 | 0.000 | 0.474 | 1.720 |

| Workplace violence | 2.780 | 0.721 | 3.856 | 0.000 | 1.363 | 4.196 |

| Anxiety about violence | 0.454 | 0.089 | 5.072 | 0.000 | 0.278 | 0.630 |

| Int_1 Workplace violence × Anxiety about violence | −0.481 | 0.191 | −2.513 | 0.012 | −0.857 | −0.105 |

| Moderating variable: Anxiety about violence | ||||||

| 1 | 1.849 | 0.391 | 4.730 | 0.000 | 1.081 | 2.618 |

| 3 | 1.205 | 0.243 | 4.942 | 0.000 | 0.726 | 1.684 |

| 4 | 0.560 | 0.312 | 1.792 | 0.073 | −0.053 | 1.174 |

| R = 0.416; R2 = 0.173; F = 35.647; p = 0.000 | ||||||

BootLLCI: bootstrap lower limit of confidence interval; BootULCI: bootstrap upper limit of confidence interval; Int_1: interaction term; TI: turnover intention; SE: standard error.

The significant effect of the moderator variable on the dependent variable in the analyses means a partial moderator (Aksu et al., 2017: 217). According to these results, anxiety about violence has a partial effect on workplace violence of nurses on turnover intention.

It can be seen in the figure that turnover intention increased when nurses’ anxiety about workplace violence increased to a level between 1 and 3 (1 – none, 2 – mild; anxious throughout the day but not all day, 3 – moderate; anxious most of the day, 4 – moderate to severe; anxiety all day and 5 – severe; severe anxiety all day). These results indicate that anxiety of violence as a moderator variable has a significant impact on the relationship between workplace violence and nurses' turnover intention (p = 0.000; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The moderating role of anxiety about violence on the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention.

Conclusion

Workplace violence is one of the greatest hazards for healthcare employees, especially nurses. Numerous studies have been conducted in the literature on this subject. Nurses, who represent one of the most important sides in the fight against COVID-19, have made and continue to make many sacrifices in this process, which requires great effort and dedication. Depending on the level of violence experienced by nurses who are exposed to all types of violence and who experience financial and moral exhaustion in their work environment, their job satisfaction decreases and their intention to fluctuate increases. This study was conducted with nurses who worked in the hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. The relationships between workplace violence, emotional exhaustion, turnover intention and job satisfaction were assessed with moderator and mediator variables.

Three hypotheses were made in the analyses to determine the significance of the mediating effect. Firstly, nurses’ job satisfaction was found to have a partial mediating effect on the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention. Thus, we conclude that H1 is supported (β = 0.731, t = 18.795, p = 0.000). Consistent with previous studies (Ducharme et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2021; Kwon et al., 2021), emotional exhaustion was found to have a significant negative relationship with job satisfaction and a significant positive relationship with turnover intention, suggesting a relationship. Secondly, the level of workplace violence among nurses had a partial mediating effect on the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention. Thus, we conclude that H2 is supported (β = 0.731, t = 18.795, p = 0.000). The findings are generally consistent with those of previous studies. Studies (Boafo and Hancock, 2017; Boafo et al., 2016; Duan et al., 2019; Heponiemi et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2020; Laeeque et al., 2018; Li et al.,2019, 2020; Liu et al., 2018; Roh and Yoo, 2012; Shahzad and Malik, 2014; Zhao et al., 2018) examined the effects of workplace violence on nurses’ turnover intention and found that workplace violence significantly influenced nurses’ turnover intention. Finally, nurses’ emotional exhaustion had a partial mediating effect on the relationship between the level of workplace violence and turnover intention.

Thus, we conclude that H3 is supported (β = 1.540, t = 6.357, p = 0.000). In addition, the significance of the moderating effect was determined for the two hypotheses in the analyses. It was found that working hours between 18.00 and 07.00 had a moderating effect on nurses’ workplace violence and turnover intention, and turnover intention increased with the level of nurses’ workplace violence. According to these results, working hours between 18.00 and 07.00 had a full effect on nurses’ workplace violence and turnover intention. Therefore, we conclude that H4 is supported. Studies (Gieter et al., 2011) found that there was a relationship between working hours and turnover intentions. In addition, the level of anxiety about violence among nurses was found to have a (partial) moderating effect on workplace violence and turnover intention. Intention to turnover increased more than the other scores when the level of workplace violence increased among nurses with anxiety about violence between levels 1 and 3. According to these results, anxiety about violence has a partial influence on nurses’ turnover intention. Thus, we conclude that H5 is supported. Studies (e.g. Ma et al., 2022; McKay et al., 2020) found that exposure to violence affects turnover intention.

The study findings have both theoretical and managerial implications. In terms of theoretical implications, it is important for healthcare organisations to provide information about workplace violence. The managerial implications of this study are quite clear for healthcare organisations. This study highlights the importance of management in preventing workplace violence, reducing emotional exhaustion and intention to leave and increasing job satisfaction among nurses. It will provide a new perspective to healthcare organisations. When workplace violence decreases, all employees in the organisation will be more successful. The results of the study contain some useful findings. To draw attention to the importance of the issue, it is important that healthcare managers and policymakers take the necessary steps as soon as possible. Having good living conditions (balance between private life and work life) of nurses will reduce their emotional exhaustion levels. For this reason, it is important to meet their personal and organisational needs (materially and morally). This will increase job satisfaction and decrease intention to leave. In addition, taking measures (developing an effective protection programme and preparing a guide for the problem) against the increasing cases of violence will reduce nurses’ intention to leave the job. In addition, nurses who had irregular working hours, especially in the COVID-19 epidemic, were exposed to very intense working hours. For this reason, proper regulation of working hours is also important in terms of human living conditions.

Key points for policy, practice and/or research.

Workplace violence increases levels of occupational exhaustion. Nurses need to feel safe in order to increase their commitment to the institution and provide high-quality, skilled services. For this reason, the factors that cause workplace violence and that negatively affect the health of nurses should be investigated and remedial action taken. In addition, the rights of unit nurses should be strengthened so that they can work more effectively.

Considering the findings of the study, health policies to prevent violence should be reviewed. Health administrators should produce different strategies when violence occurs more frequently and in units. In addition to these policies, training programmes should be organised for nurses to reduce their anxiety levels. Finally, it should be ensured that nurses can report violence and be strengthened in this regard.

We should be aware that violence may increase in the future and proactively develop strategies to prevent it.

Planning should include mutual clarification of patient and nurse expectations, establishment of healthy communication channels and education about the impact of all forms of violence on patients, their families and the public.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jrn-10.1177_17449871231182837 for The relationship between workplace violence, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction and turnover intention among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic by Özlem Gedik, Refika Ülke Şimdi, Şerife Kıbrıs and Derya Kara (Sivuk) in Journal of Research in Nursing

Biography

Özlem Gedik is a research assistant in the Faculty of Health Sciences, Afyonkarahisar Health Sciences University. She graduated from Selçuk University at the Department of Healthcare Management in 2017. She has a master’s degree from the same department at Gazi University, also she is a PhD student at the Ankara Haci Bayram Veli University. She worked as an Advertising Officer in Gazi University Hospital, International Health Office. She has interests in health management, health tourism, Industry 4.0 and leadership.

Refika Ülke Şimdi is a research assistant in the Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Erzincan Binali Yıldırım University. She graduated from Necmettin Erbakan University’s Department of Healthcare Management in 2017. She has a master’s degree from the same department at Gazi University, and is also a PhD student at the Ankara Haci Bayram Veli University. She has interests in health management, health information systems and e-health.

Serife Kibris is an instructer in the Arac Rafet Vergili Vocational School Department of Medical Services and Techniques, Kastamonu University. She graduated from Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University School of Nursing in 2007. She has a master’s degree from the Department of Health Administration at Ankara Haci Bayram Veli University, and is a PhD student at the same department. She worked as a nurse Başkent University Faculty of Medicine, TOBB ETÜ Medical Faculty Hospital between 2007 and 2012 in Ankara. She teaches courses on nursing services administration, quality and patient safety, healthcare management and health tourism.

Derya Kara (Sivuk), PhD, is a professor in the Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Ankara Haci Bayram Veli University. She graduated in 2002 from Gazi University. She received her PhD degree from Gazi University. She has extensive experience in human resource management, health care and tourism management with respect to gender. She teaches courses on human research management, health tourism and gender. She has published in national and international journals. She has also received a number of awards in the research field.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: The study was ethically approved by the Ankara Hacı Bayram Veli University Ethics Committee (Reference Number 12, 2.12.20).

ORCID iD: Özlem Gedik  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0840-0765

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0840-0765

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Özlem Gedik, Research Assistant, Healthcare Management, Faculty of Health Sciences, Afyonkarahisar Health Sciences University, Afyonkarahisar, Turkey.

Refika Ülke Şimdi, Research Assistant, Healthcare Management, Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Erzincan Binali Yıldırım University, Erzincan, Turkey.

Şerife Kıbrıs, Instructor, Medical Documentation and Secretarial, Arac Rafet Vergili Vocational School, Kastamonu University, Kastamonu, Turkey.

Derya Kara (Sivuk), Professor, Healthcare Management, Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Ankara Hacı Bayram Veli University, Ankara, Turkey.

References

- Abed M, Morris E, Sobers-Grannum N. (2016) Workplace violence against medical staff in healthcare facilities in Barbados. Occupational Medicine 66: 580–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AbuAlRub RF, Al-Asmar AH. (2014) Psychological violence in the workplace among Jordanian hospital nurses. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 25: 6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbolat M, Ünal Ö, Durmuş A, et al. (2018) Hekim ve hemşirelerin şiddete maruz kalma durumunun ve şiddet görme korkusunun tükenmişliğe etkisi. In: 3. Uluslararası Farklı Şiddet Boyutları ve Toplumsal Algı Kongresi, Kocaeli, pp. 369–371. [Google Scholar]

- Aksu G, Eser MT, Güzeller CO. (2017) Açımlayıcı ve doğrulayıcı faktör analizi ile yapısal eşitlik modeli uygulamaları. Ankara: Detay Yayıncılık. [Google Scholar]

- Al B, Zengin S, Deryal Y, Gökçen C, et al. (2012) Sağlık çalışanlarına yönelik artan şiddet. The Journal of Academic Emergency Medicine 11: 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Alam MM, Mohammad JF. (2010) Level of job satisfaction and intent to leave among Malaysian nurses. Business Intelligence Journal 3: 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Albashtawy M, Aljezawi ME. (2016) Emergency nurses’ perspective of workplace violence in Jordanian hospitals: A national survey. International Emergency Nursing 24: 61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albashtawy M. (2013) Workplace violence against nurses in emergency departments in Jordan. International Nursing Review 60: 550–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkorashy HAE, Al Moalad FB. (2016) Workplace violence against nursing staff in a Saudi university hospital. International Nursing Review 63: 226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Omari H. (2015) Physical and verbal workplace violence against nurses in Jordan. International Nursing Review 62: 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alyaemnia A, Alhudaithi H. (2016) Workplace violence against nurses in the emergency departments of three hospitals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional survey. NursingPlus Open 2: 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Arshadi N, Shahbazi F. (2013) Workplace characteristics and turnover intention: mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 84: 640–645. [Google Scholar]

- Ayrancı U. (2005) Violence toward health care workers in emergency departments in west Turkey. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 28: 361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziri B. (2011) Job satisfactıon: A literature review. Management Research and Practice 3: 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Babiarczyk B, Turbiarz A, Tomagová M, et al. (2020) Reporting of workplace violence towards nurses in 5 European countries: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health 33: 325–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawakid K, Abdulrashid O, Mandoura N, et al. (2017) Burnout of physicians working in primary health care centers under Ministry of Health Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 9: e1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydin AKEA, Erenler AK. (2014) Workplace violence in emergency department and its effects on emergency staff. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health 16: 288–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belayachi J, Berrechid K, Amlaiky F, et al. (2010) Violence toward physicians in emergency departments of Morocco: Prevalence, predictive factors, and psychological impact. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology 5: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernaldo-De-Quirós M, Piccini AT, Gómez MM, et al. (2015) Psychological consequences of aggression in pre-hospital emergency care: Cross sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies 52: 260–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boafo IM, Hancock P. (2017) Workplace violence against nurses: A cross-sectional descriptive study of Ghanaian nurses. SAGE Open 7: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Boafo IM, Hancock P, Gringart E. (2016) Sources, incidence and effects of non-physical workplace violence against nurses in Ghana. Nursing Open 3: 99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordignon M, Monteiro MI. (2019) Predictors of nursing workers’ intention to leave the work unit, health institution and profession. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 27: e3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd JW, Arvey RD, Lawless P. (1996) Correlates and consequences of workplace violence. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 1: 197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdorf A, Porru F, Rugulies R. (2020) The COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic: Consequences for occupational health. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 46: 229–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büyüköztürk Ş. (2018). Sosyal bilimler için veri analizi el kitabı: istatistik, araştırma deseni spss uygulamaları ve yorum, 24. Baskı. Ankara: Pegem Akademi Yayıncılık. [Google Scholar]

- Cammann C, Fichman M, Jenkins D, et al. (1979) The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire. Unpublished Manuscript, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. [Google Scholar]

- Carsten JM, Spector PE. (1987) Unemployment, job satisfaction, and employee turnover: A meta-analytic test of the Muchinsky model. Journal of Applied Psychology 72: 374–381. [Google Scholar]

- Castellón AMD. (2011) Occupational violence in nursing: Explanations and coping strategies. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 19: 156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çelik SŞ, Celik Y, Ağırbaş İ, et al. (2007) Verbal and physical abuse against nurses in Turkey. International Nursing Review 54: 359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CF. (2006) Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and flight attendants’ turnover ıntentions: A note. Journal of Air Transport Management 12: 274–276. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Lin S, Ruan Q, et al. (2016) Workplace violence and its effect on burnout and turnover attempt among Chinese medical staff. Archives of Environmental and Occupational Health 71: 330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung T, Lee PH, Yip PS. (2018) The association between workplace violence and physicians’ and nurses’ job satisfaction in Macau. PLoS One 13: e0207577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung T, Yip PS. (2017) Workplace violence towards nurses in Hong Kong: Prevalence and correlates. BMC Public Health 17: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Converso D, Sottimano I, Balducci C. (2021) Violence exposure and burnout in healthcare sector: Mediating role of work ability. Medicina Del Lavoro 112: 58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coşkun Cenk S. (2019) An analysis of the exposure to violence and burnout levels of ambulance staff. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine 19: 21–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafny HA, Beccaria G. (2020) I do not even tell my partner: Nurses’ perceptions of verbal and physical violence against nurses working in a regional hospital. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29: 3336–3348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X, Ni X, Shi L, et al. (2019) The impact of workplace violence on job satisfaction, job burnout, and turnover intention: The mediating role of social support. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 17: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme LJ, Knudsen HK, Roman PM. (2007) Emotional exhaustion and turnover intention in human service occupations: The protective role of coworker support. Sociological Spectrum 28: 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hneiti M, Shaheen AM, Bani Salameh A, et al. (2020) An explorative study of workplace violence against nurses who care for older people. Nursing Open 7: 285–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliyana A, Ma’arif S, Muzakki (2019) Job satisfaction and organizational commitment effect in the transformational leadership towards employee performance. European Research on Management and Business Economics 25: 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeilpour M, Salsali M, Ahmadi F. (2011) Workplace violence against Iranian nurses working in emergency departments. International Nursing Review 58(1): 130–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita S, Ito S, Seto K, et al. (2012) Risk factors of workplace violence at hospitals in Japan. Journal of Hospital Medicine 7: 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fute M, Mengesha ZB, Wakgari N, et al. (2015) High prevalence of workplace violence among nurses working at public health facilities in Southern Ethiopia. BMC Nursing 14: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates DM, Ross CS, McQueen L. (2006) Violence against emergency department workers. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 31: 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieter DS, Hofmans J, Pepermans R. (2011) Revisiting the impact of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on nurse turnover intention: An individual differences analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies 48: 1562–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gökçe T, Dündar C. (2008) Samsun ruh ve sinir hastalıkları hastanesi’nde çalışan hekim ve hemşirelerde şiddete maruziyet sıklığı ve kaygı düzeylerine etkisi. İnönü Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi Dergisi 15: 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn S, Müller M, Needham I, et al. (2010) Factors associated with patient and visitor violence experienced by nurses in general hospitals in Switzerland: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing 19: 3535–3546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben JR, Buckley MR. (2004) Burnout in organizational life. Journal of Management 30: 859–879. [Google Scholar]

- Han CY, Lin CC, Barnard A, et al. (2017) Workplace violence against emergency nurses in Taiwan: A phenomenographic study. Nursing Outlook 65: 428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaei F, MacPhee M, Ma A. (2020) Workplace violence among British Columbia nurses across different roles and contexts. Healthcare 8: 98–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaei F, MacPhee M, Susan Dahinten V. (2016) RN s and LPN s: Emotional exhaustion and intention to leave. Journal of Nursing Management, 24: 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. (2017) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. NewYork: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Montoya AK, Rockwood NJ. (2017) The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: Process versus structural equation modeling. Australasian Marketing Journal 25: 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Heponiemi T, Kouvonen A, Virtanen M, et al. (2014) The prospective effects of workplace violence on physicians’ job satisfaction and turnover intentions: The buffering effect of job control. BMC Health Services Research 14(1): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh KL, Duncan SM, Estabrooks CA, et al. (2003) Workplace violence in Alberta and British Columbia hospitals. Health Policy 63: 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchberger PA. (2009) Violence against female student nurses in the workplace. Nursing Forum 44: 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- İlhan Ü. (2010) İşyerinde psikolojik tacizin (mobbing) tarihsel arka planı ve Türk hukuk sisteminde yeri. Ege Akademik Bakış 10: 1175–1186. [Google Scholar]

- ILO (1998) When Working Becomes Hazardous, Punching, Spitting, Swearing, Shooting: Violence at Work Goes Global. International Labor Organization, Cenevre, pp. 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M, Ashley D. (2005) Physical and psychological violence in Jamaica’s health sector. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 18: 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong IY, Kim JS. (2017) The relationship between ıntention to leave the hospital and coping methods of emergency nurses after workplace violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27: 1692–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HJ, Shin J, Lee EH. (2020) Relationship of workplace violence to turnover intention in hospital nurses: Resilience as a mediator. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 50: 728–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly LA, Gee PM, Butler RJ. (2021) Impact of nurse burnout on organizational and position turnover. Nursing Outlook 69: 96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshknab MF, Oskouie F, Najafi F, et al. (2015) Psychological violence in the health care settings in Iran: A cross-sectional study. Nursing and Midwifery Studies 4: e24320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Kim J-S, Choe K, et al. (2018) Mediating effects of workplace violence on the relationships between emotional labour and burnout among clinical nurses. Leading Global Nursing Research 74: 2331–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Lee E, Lee H. (2019) Association between workplace bullying and burnout, professional quality of life, and turnover intention among clinical nurses. PLoS One 14: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingma M. (2008) From workplace violence to wellness. In: Needham I, Kingma M, O’Brien-Pallas L, McKenna K, Tucker R, Oud N. (eds) Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. Together, Creating a Safe Work Environment. Netherlands, 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalenko T, Gates D, Gillespie GL, et al. (2013) Prospective study of violence against ED workers. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 31: 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon CY, Lee B, Kwon OJ, et al. (2021) Emotional labor, burnout, medical error, and turnover intention among South Korean nursing staff in a university hospital setting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok K, Li KE, Ng Y, et al. (2006) Prevalence of workplace violence against nurses in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Medical Journal 12: 6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laeeque SH, Bilal A, Babar S, et al. (2018) How patient-perpetrated workplace violence leads to turnover intention among nurses: The mediating mechanism of occupational stress and burnout. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma 27: 96–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lafta RK, Falah N. (2019) Violence against health-care workers in a conflict affected city. Medicine, Conflict and Survival 35: 65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. (2020) Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open 3: e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanctôt N, Guay S. (2014) The aftermath of workplace violence among healthcare workers: A systematic literature review of the consequences. Aggression and Violent Behavior 19: 492–501. [Google Scholar]

- Lawoko S, Soares JJ, Nolan P. (2004) Violence towards psychiatric staff: a comparison of gender, job and environmental characteristics in England and Sweden. Work and Stress 18: 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Zhang L, Xiao G, et al. (2019) The relationship between workplace violence, job satisfaction and turnover intention in emergency nurses. International Emergency Nursing 45: 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Zhang L, Xiao G, et al. (2020) Effects of organizational commitment, job satisfaction and workplace violence on turnover ıntention of emergency nurses: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Practice 26: e12854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zheng J, Liu K, et al. (2019) Workplace violence against nurses, job satisfaction, burnout, and patient safety in Chinese hospitals. Nursing Outlook 67: 558–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Zhao S, Shi L, et al. (2018) Workplace violence, job satisfaction, burnout, perceived organisational support and their effects on turnover intention among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 8: e019525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Cabarcos MÁ, López-Carballeira A, Ferro-Soto C. (2019) The role of emotional exhaustion among public healthcare professionals. Journal of Health Organization and Management 90: 60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Wu XS. (2003) American hospital prevent workplace violence. Chinese Journal of Practical Nursing 19: 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Chen F, Xing D, et al. (2022). Study on the associated factors of turnover intention among emergency nurses in China and the relationship between major factors. International Emergency Nursing 60: 101106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnavita N, Heponiemi T. (2012) Violence towards health care workers in a Public Health Care Facility in Italy: A repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Health Services Research 12: 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. (2001) Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology 52: 397–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C, Jackson SE. (1981) The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- McKay D, Heisler M, Mishori R, et al. (2020) Attacks against health-care personnel must stop, especially as the world fights COVID-19. Lancet 395: 1743–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhaul KM, Lipscomb JA. (2004) Workplace violence in health care: Recognized but not regulated. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 9: 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mento C, Silvestri MC, Bruno A, et al. (2020) Workplace violence against healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 51: 101381. [Google Scholar]

- Mo Y, Deng L, Zhang L, et al. (2020) Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. Journal of Nursing Management 28: 1002–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalbant Ş. (2006) Türkiye’de sağlık sektöründe çalışma koşulları ve sendikal örgütlenme hakkı. Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, İzmir. [Google Scholar]

- Newby JC, Mabry MC, Carlisle BA, et al. (2020) Reflections on nursing ingenuity during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Neuroscience Nursing 52: E13–E16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngamkroeckjoti C, Ounprechavanit P, Kijboonchoo T. (2012) Determinant factors of turnover intention: A case study of air conditioning company in Bangkok, Thailand. In: International conference on trade, tourism and management Bangkok (Tayland), pp. 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Olashore AA, Akanni ÖO, Ogundipe RM. (2018) Physical violence against health staff by mentally ill patients at a psychiatric hospital in Botswana. BMC Health Services Research 18: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omidi Z, Khanjari S, Salehi T, et al. (2023) Association between burnout and nurses’ quality of life in neonatal intensive care units: During the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Neonatal Nursing 29: 144–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özcan NK, Bilgin H. (2011) Violence towards healthcare workers in Turkey: A systematic review. Türkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Science 31: 1442. [Google Scholar]

- Pai DD, Lautert L, Souza SBCD, et al. (2015) Violence, burnout and minor psychiatric disorders in hospital work. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 49: 457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai HC, Lee S. (2011) Risk factors for workplace violence in clinical registered nurses in Taiwan. Journal of Clinical Nursing 20: 1405–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak A, Adegboye OA, Adekunle AI, et al. (2020) Economic consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak: The need for epidemic preparedness. Frontiers in Public Health 8: 241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M, Cho SH, Hong HJ. (2015) Prevalence and perpetrators of workplace violence by nursing unit and the relationship between violence and the perceived work environment. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 47: 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pınar R, Ucmak F. (2011) Verbal and physical violence in emergency departments: A survey of nurses in Istanbul, Turkey. Journal of Clinical Nursing 20: 510–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinar T, Acikel C, Pinar G, et al. (2017) Workplace violence in the health sector in Turkey: A national study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 32: 2345–2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randhawa G. (2007) Relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intentions: An empirical analysis. Indian Management Studies Journal 11: 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Rayan A, Qurneh A, Elayyan R, et al. (2016) Developing a policy for workplace violence against nurses and health care professionals in Jordan: A plan of action. American Journal of Public Health Research 4: 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Roche M, Diers D, Duffield C, et al. (2010) Violence toward nurses, the work environment, and patient outcomes. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 42: 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh YH, Yoo YS. (2012) Workplace violence, stress, and turnover intention among perioperative nurses. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing 24: 489–498. [Google Scholar]

- Sahip Karakaş T, Gamsızkan Z, Cangür Ş. (2021) Exposure of violence and its effects on health care workers. Konuralp Medical Journal 13: 327–333. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad A, Malik RK. (2014) Workplace violence: An extensive issue for nurses in Pakistan – a qualitative ınvestigation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 29: 2021–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GD, Ng F, Li WHC. (2020) COVID-19: Emerging compassion, courage and resilience in the face of misinformation and adversity. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29: 1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stordeur S, D’hoore W, Vandenberghe C. (2001) Leadership, organizational stress, and emotional exhaustion among hospital nursing staff. Journal of Advanced Nursing 35: 533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P, Zhang X, Sun Y, et al. (2017) Workplace violence against health care workers in North Chinese hospitals: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14: 96–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takma Ç, Atıl H. (2006) Bootstrap metodu ve uygulanışı üzerine bir çalışma 2. Güven aralıkları, hipotez testi ve regresyon analizinde Bootstrap metodu. Ege Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi 43: 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Teke Yaşar H, Aygün A. (2020) Burnout in physicians who are exposed to workplace violence. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 69: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomagová M, Zeleníková R, Kozáková R, et al. (2020) Violence against nurses in healthcare facilities in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Central European Journal of Nursing and Midwifery 11: 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D, Dawis R, England G, et al. (1967) Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Work Adjustment Project, Industrial Relations Center, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2002). World Report on Violence and Health, Geneva, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42495/9241545615_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Wang P, Kelifa MO, et al. (2021) How workplace violence correlates turnover intention among Chinese health care workers in COVID-19 context: The mediating role of perceived social support and mental health. Journal of Nursing Management 30: 1407–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeun YR, Han JW. (2016) Effect of nurses’ organizational culture, workplace bullying and work burnout on turnover intention. International Journal of Bio-Science and Bio-Technology 8: 372–380. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz K. (2020) Adana ilinde sağlık çalışanlarının şiddete uğrama sıklığı ve sağlıkta şiddet konusundaki düşünceleri. Uzmanlık Tezi, Çukurova Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi Adli Tıp Anabilim Dalı, Adana. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf D. (1999) Organisational, work group related and personal causes of mobbing/bullying at work. International Journal of Manpower 20: 70–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S-H, Shi Y, Sun Z-N, et al. (2018) Impact of workplace violence against nurses’ thriving at work, job satisfaction and turnover intention: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27: 2620–2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jrn-10.1177_17449871231182837 for The relationship between workplace violence, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction and turnover intention among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic by Özlem Gedik, Refika Ülke Şimdi, Şerife Kıbrıs and Derya Kara (Sivuk) in Journal of Research in Nursing