Abstract

Practical relevance:

Chronic otitis can be one of the most frustrating diseases to manage for a small animal practitioner. While it occurs less commonly in the cat than the dog, it is no less challenging. The purpose of this review is to discuss the common and uncommon causes of chronic otitis in the cat within the clinical framework used for diagnosis and treatment. The focus is on diseases that affect the ear canal, rather than those restricted to the pinnae.

Clinical challenges:

Otitis is multifactorial, which complicates management. A common clinical mistake is to focus solely on treating the infection present. Only by addressing all factors will a clinician successfully control chronic otitis. For the purposes of this review, the authors have adopted the established model of separating primary, predisposing and perpetuating causes of otitis. Primary factors are those that directly cause otitis (inflammation); predisposing factors are those that put the patient at risk for development of otitis; and perpetuating factors are those that result in ongoing clinical signs of otitis or that prevent clinical resolution.

Audience:

This review is aimed at veterinarians who treat cats and particularly those with an interest in feline dermatology and otology.

Equipment:

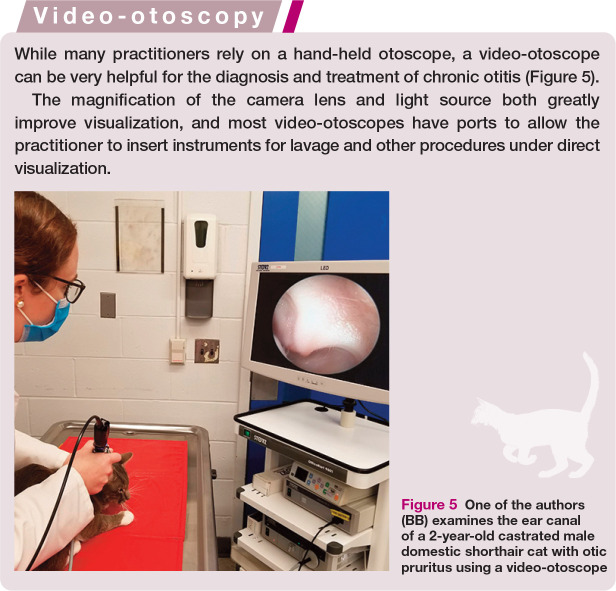

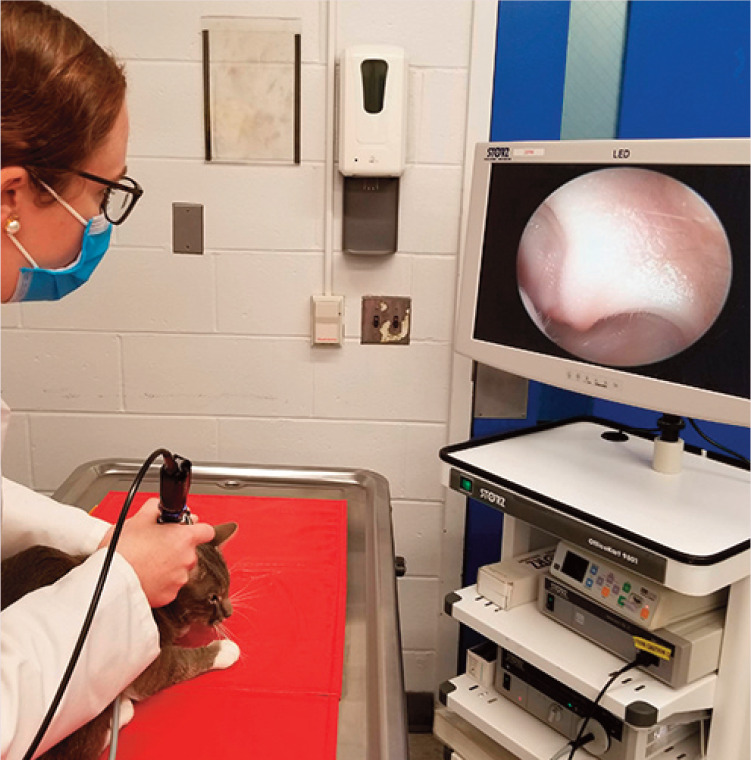

While many practitioners rely on a hand-held otoscope, a video-otoscope can be very helpful for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic otitis.

Evidence base:

This review presents up-to-date information regarding the diagnosis and treatment of chronic otitis in cats, with emphasis on the most recent peer-reviewed literature.

Keywords: Chronic otitis, otitis externa, otitis media, Otodectes cynotis, inflammatory aural polyp

The normal feline ear

Anatomic features and physical examination

With the exception of the Scottish Fold, domestic cats have upright pinnae, allowing for air circulation. This makes them less vulnerable to environmental factors that predispose to otitis, such as humidity and the effects of bathing or swimming. Despite the conformational difference in the Scottish Fold, an increase in otitis has not been reported in this breed.

It is normal for the feline ear to have a moderate amount of dark brown ceruminous debris present in the canal. 1 In the absence of other clinical signs, this is not suggestive of otitis externa. Cerumen may also be clear, white or yellow.

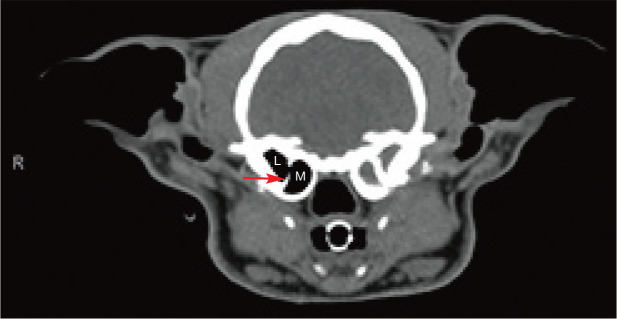

Unlike the dog, the bulla in the cat is divided into medial and lateral compartments by a thin, bony septum with a small opening between (Figure 1). 2 Under otoscopic guidance, it is feasible to access the lateral compartment; however, a bulla osteotomy is typically required to access the medial compartment. This affects treatment options for feline middle ear disease.

Figure 1.

CT of a 6-year-old castrated male domestic shorthair cat with unilateral otitis media and otitis externa. Note the bony septum (arrow) that divides the medial (M) and lateral (L) compartments of the tympanic bulla. On the left side, there is fluid filling the bulla, and the bulla and septum are sclerotic secondary to chronic otitis media

Normal cytologic findings and flora

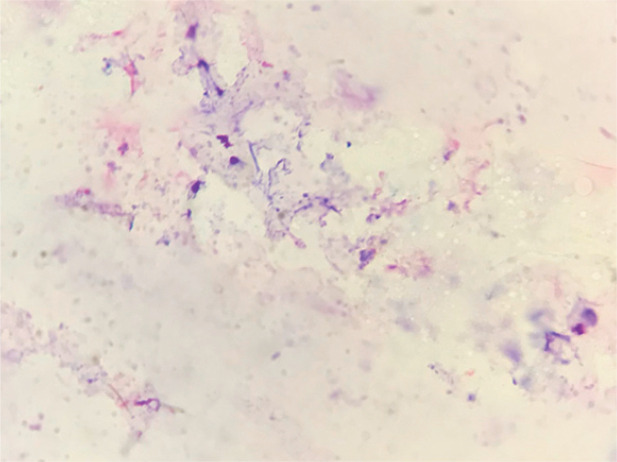

Feline ear cytology can be challenging to interpret because cats’ cerumen can absorb stain, resulting in a stain artifact resembling bacterial cocci (Figure 2). Evaluating for pairs of cocci may help avoid misinterpretation.

Figure 2.

Cytology from a normal feline ear with mild staining artifact

Ginel et al evaluated cytologic samples from the external ear canal of healthy cats and cats with otitis externa to develop reference intervals for otic cytology. 3 Cats were considered normal if they had two or fewer Malassezia organisms and four or fewer bacterial organisms per high-power field (HPF). 3 The presence of cocci on cytology in healthy cats varies greatly by report, ranging from 2% to 71%,1,4 with a median density of 0.3 cocci per HPF in one study. 4 The most commonly cultured bacteria from feral cats’ ears in Grenada, West Indies were coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species, which made up 67% of isolates. 5

Malassezia species, most commonly Malassezia pachydermatis, can be found on aural cytology and culture in normal cats.6–11 The prevalence of Malassezia species on otic cytology reported in the literature ranges from 23% to 83%.1,4,6–8,12 In normal cats, the median density of Malassezia species on cytology ranges from 0.2 to 0.5 organisms per HPF.1,3 Among Belgian stray cats, 94% of those with Malassezia species on cytology had three or fewer organisms per HPF. 12

Rod-shaped bacteria are rarely seen in healthy cats, so their presence suggests otic pathology.1,3 In one study, Bacillus species and Pantoea species accounted for 17% and 4% of bacterial isolates from the ears of feral cats, respectively. 5

Keratinocytes and nucleated keratinocytes are a normal finding in feline otic cytology1,12 and were not increased in a group of cats with otitis externa. 3 Low numbers of melanin clumps and saprophytes can also be seen in normal cats. 12 However, inflammatory cells are not a normal finding in the feline ear, and their presence suggests disease. 3

Clinical presentation of, and diagnostic approach for, feline otitis

Owners often report head shaking, scratching or pawing at the ears, pain, excessive ceruminous debris and/or a foul odor. Less commonly, decreased appetite or lethargy are reported.

On physical examination, a cat with otitis externa may have excoriations, erythema, crusting and edema of the pinna or ear canal. The quantity and character of discharge is variable. The cat may exhibit pain on manipulation of the ear or opening the mouth, and a scratch response can be seen during evaluation of the ear. Aural hematoma is sometimes seen in cats secondary to otic pruritus.

On otoscopic examination, erythema and edema of the canal are typically present. The tympanic membrane can be thickened or opaque. If otitis media is present, fluid may be visible through the tympanum, or the tympanic membrane may bulge outward (see ‘Otitis media’ section later). Purulent debris can impede evaluation of the tympanum or horizontal canal.

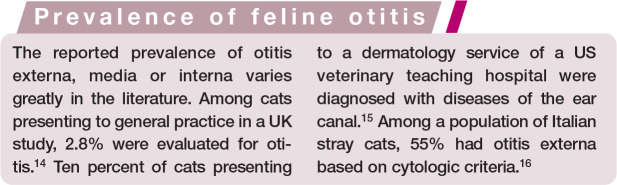

Distribution (unilateral or bilateral) of otitis, lesion character and the presence of concurrent neurologic signs or systemic illness can aid in differentiating between causes (see Table 1). The overall diagnostic approach to otitis is summarized in the box on page 436.

Table 1.

Differentiation of diseases contributing to feline otitis (continued on page 436)

| Disease or etiology | History | Clinical features | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common | Otodectes cynotis | ✜ Most common cause of feline otitis externa ✜ Young cats ✜ No recent history of preventive treatment with efficacy against O cynotis ✜ Older cats may be infested without clinical signs |

✜ Bilateral ✜ Otic pruritus ✜ Excessive dark brown ceruminous debris with ‘coffee ground’ texture ✜ Mites may be present on the face and around the ears ✜ Secondary infection common |

| Allergic skin disease | ✜ Chronic otitis that recurs after cytologic resolution

✜ Previous or concurrent pruritus or skin lesions consistent with feline allergy – eosinophilic granuloma complex, symmetrical alopecia, head and neck pruritus or miliary dermatitis ✜ Good response to glucocorticoids |

✜ Bilateral ✜ Secondary infection common ✜ Excoriations of the pinnae and preauricular area |

|

| Dermatophytosis | ✜ Young cats and geriatric cats ✜ Cats with systemic disease or immunosuppression ✜ Others in the household may be affected ✜ Persians may be over-represented ✜ Poor response to glucocorticoids |

✜ Bilateral ✜ Alopecia, erythema, scale or crust, and variable pruritus ✜ Disease is not usually restricted to the ear canal ✜ Pinnae and head are commonly affected |

|

| Infrequent | Inflammatory aural polyps | ✜ Chronic ✜ Young cats and kittens ✜ Secondary infections may fail to respond to appropriate treatment ✜ Patients may also have previous or concurrent upper respiratory or ocular signs, vestibular signs or Horner’s syndrome |

✜ Unilateral >bilateral ✜ Polyp may be restricted to the middle ear or may extend into the external canal ✜ Smooth, pink nodule can often be visualized in the canal at the level of the tympanum ✜ Secondary bacterial otitis common |

| Neoplasia | ✜ Chronic ✜ Older cats ✜ Secondary infections may fail to respond to appropriate treatment ✜ Vestibular signs, facial nerve paralysis and pain on opening the mouth may be seen |

✜ Unilateral ✜ A mass may be visualized within the canal ✜ Secondary bacterial otitis common |

|

| Pemphigus foliaceus | ✜ Acute onset, chronic disease ✜ Most cats have multiple sites affected ✜ Signs of systemic illness common, including lethargy, fever and decreased appetite ✜ Variable pruritus ✜ Typically, an excellent response to glucocorticoids |

✜ Bilateral ✜ Pustules, erosions and crusts with secondary alopecia on affected skin ✜ Pinnae are the most commonly affected site; ear canals are affected less often ✜ Secondary infection of affected skin is common |

|

| Contact reaction | ✜ Recent treatment with topical otic product ✜ Otic pruritus and discomfort worse after treatment |

✜ Bilateral if both ears treated ✜ Marked otic inflammation, which may extend onto the concave pinnae ✜ Cytology may show worsening inflammation despite improvement in degree of infection |

|

| Uncommon | Ceruminous gland cystomatosis | ✜ Older cats ✜ Male cats over-represented ✜ Cats with a history of chronic otitis ✜ Persians and Abyssinians over-represented |

✜ Bilateral ✜ Dark brown to gray-blue cystic papules and nodules present on the concave pinnae extending into the canal ✜ Secondary infection can occur |

| Proliferative and necrotizing otitis externa (PNOE) | ✜ Kittens and young adults ✜ Patients may have a history of an incomplete response to glucocorticoids |

✜ Bilateral ✜ Concave pinnae and ear canals affected ✜ Proliferative plaques covered in thick adherent keratinaceous exudate ✜ Secondary infection can occur |

|

| Idiopathic facial dermatitis of Persian and Himalayan cats | ✜ Chronic ✜ Young Persian and Himalayan cats ✜ Progressive pruritus ✜ Poor response to glucocorticoids and antibiotics |

✜ Bilateral ✜ Otic erythema and black, waxy debris ✜ Black debris in the hair on the face, progressing to erythema, crusting and ulcers ✜ Secondary infection can occur, particularly on the face |

|

| Ceruminoliths | ✜ Chronic history of otitis externa ✜ Chronic use of ear medications or cleansers may predispose |

✜ Hard concretion of cerumen, keratin and/or dried medication seen on the floor of the horizontal canal close to the tympanum on otoscopy | |

| Idiopathic ceruminous otitis | ✜ Excessive debris may be present lifelong | ✜ Bilateral ✜ Accumulation of ceruminous debris ✜ Secondary infection can occur |

|

| Aspergillus species | ✜ Chronic ✜ History of treatment with oral and topical antibiotics common, especially fluoroquinolones ✜ Immunosuppression may predispose |

✜ Unilateral >bilateral ✜ Brown ceruminous debris ✜ Mixed infection is common ✜ Rarely nodular otitis ✜ Otitis media may occur |

|

| Demodex cati | ✜ Generalized D cati infestation usually occurs in immunocompromized cats | ✜ Bilateral ✜ Ceruminous otitis |

|

| Cryptococcus neoformans | ✜ Acute ✜ Access to outdoors ✜ Males may be over-represented ✜ Additional signs of systemic illness may occur, including upper respiratory signs and sudden blindness |

✜ If widespread disease, cutaneous nodules with draining tracts may also be seen | |

| Rare | Sebaceous gland dysplasia | ✜ Occurs congenitally in short-haired kittens (4–12 weeks old)

✜ Hypotrichosis starts on the head but quickly generalizes |

✜ Bilateral ✜ Crusting within the canal and along pinnal margins ✜ Generalized alopecia and scale with a coarse haircoat ✜ Otitis may occur secondary to obstruction of the canal |

| Cholesterol granuloma | ✜ Vestibular ataxia, circling, head tilt and Horner’s syndrome may be seen | ✜ Unilateral ✜ Associated with otitis media ✜ A mass may be visualized within the middle ear ✜ Infection may be present |

|

| Hypothyroidism | ✜ Chronic ✜ Cats with spontaneous hypothyroidism may also have lethargy, weight gain, hypotrichosis, scale or an unkempt haircoat |

✜ Bilateral | |

| Demodex gatoi | ✜ Other cats in household may be affected ✜ Contagious - typically acquired from other cats ✜ Affected cats may have a history of pinnectomy |

✜ Unilateral in one cat

4

✜ Pruritus results in self-induced alopecia and excoriations in cats with generalized D gatoi infestation |

|

| Sporothrix schenckii | ✜ Acute ✜ Relatively common in Brazil ✜ Reported in a young cat 13 ✜ Access to outdoors |

✜ Unilateral ✜ Ulcers, erythema and dark pyogranulomatous otic discharge ✜ Mixed infection |

Primary factors causing otitis

Parasites

Otodectes cynotis

Otodectes cynotis is the most common primary cause of feline otitis externa and is implicated in 53–69% of clinical cases.8,11,16 Conventional wisdom holds that Otodectes mites are most common in young cats, though older cats may be more likely to have asymptomatic infestations.18,19 The reported prevalence of Otodectes mite infestation is highly variable in the published literature, ranging from 0.9% to 37%.4,12,16,18,20,21 This may be due to differences in populations evaluated (stray vs client-owned), diagnostic techniques and geographic region.

Patients with Otodectes mite infestation are usually affected bilaterally.4,12 They often present with otic pruritus and abundant dark brown ceruminous debris reminiscent of coffee grounds.16,18 One study found that 23% of cats with Otodectes mites were also affected in areas other than the ear canals, 15 and feline chin acne has been associated with Otodectes mite infestation. 18 Secondary bacterial or Malassezia infection may occur.11,22

Otodectes mites can be identified on otoscopy in 67–93% of cases,16,23 but the abundant dark cerumen present in most patients with otoacariasis may reduce the sensitivity of otoscopy. 19 If mites are not seen on otoscopy, an ear mite preparation should be performed (see box below). In one study, collecting cerumen with a curette was more rewarding than with a cotton-tipped applicator, with 93% and 51% diagnostic sensitivity, respectively. 23

There are many products that are effective for the treatment of Otodectes mite infestation in cats. Historically, otic preparations have been used, but these products require repeated aural treatment, which may reduce compliance. Milbemycin oxime (0.1%, MilbeMite; Elanco) remains a clinically useful otic treatment because it is labeled for kittens as young as 4 weeks of age.

Newer systemic products are dosed less frequently and are usually administered as a topical transdermal preparation, which may improve client compliance. Additionally, they will also treat mites that migrate outside of the ear canals (most frequently along the head and neck region) more effectively than otic preparations. A systematic review in 2016 of treatment efficacy for Otodectes mite infestation identified only two treatments with fair evidence supporting their efficacy: spot-on 10% imidacloprid with 1% moxidectin (Advantage Multi; Bayer) and selamectin (Revolution; Zoetis). 22 More recently, researchers have investigated isoxazolines in cats with O cynotis. Afoxolaner (no product available labeled for use in cats), selamectin plus sarolaner (Revolution Plus; Zoetis), fluralaner (Bravecto; Merck) and fluralaner plus moxidectin (Bravecto Plus; Merck) resolved O cynotis infestations in cats after a single application.24–27

Demodex species

Demodex cati has been identified on ear mite preparations in cats15,28 and can be associated with ceruminous otitis externa, with or without pruritus. 1 Infested cats may not show any signs of dermatological disease outside of the ear canal. 15 Cats with generalized demodicosis owing to D cati should be evaluated for any disease that may cause immunosuppression.1,15 The prevalence of D cati infestation is ⩽1%.15,16,18 Demodex gatoi has been documented in an ear of a cat with otitis externa but is not commonly associated with otic disease. 4 Isoxazolines are highly effective at treating demodicosis in the dog, and both fluralaner and sarolaner (in combination with selamectin) have been reported to be effective for treatment of feline demodicosis.29–32

Primary fungal disease

Dermatophytosis

The most common fungal disease in cats is dermatophytosis, involving Microsporum canis in particular. Dermatophytosis causes lesions of alopecia, erythema and scale, and should be considered as a differential in any cat presenting with pruritus or these non-specific skin lesions. One of the common sites for dermatophytic lesions is the ear, including the canal, pinna and surrounding skin, 33 but it is uncommon to see dermatophytosis restricted to the ear canal. Identification of cats with dermatophytosis is important due to the risks of zoonosis and contagious spread in multi-cat environments. For comprehensive guidelines regarding the diagnosis and treatment of dermatophytosis, readers are referred to the 2017 clinical consensus document from the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology. 34

Other fungal diseases

Less commonly, other fungal organisms may cause otomycosis. In a retrospective case series, Goodale et al described nine cats diagnosed with otitis externa with Aspergillus species isolated on culture; Aspergillus fumigatus was the most commonly isolated species. 35 A single case of acute unilateral otitis externa caused by Sporothrix schenckii has been described in a 10-month-old cat in Brazil, which resolved after treatment with itraconazole. 13 Chronic bilateral otitis interna caused by Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii was identified at necropsy in a 7-year-old cat with a 9-day history of vestibular ataxia and head tilt. 36 A prospective case series of 35 cats with cryptococcosis identified one cat for which the site of infection was the ears. 37

Allergic skin disease

Among cats diagnosed with allergies at a veterinary teaching hospital, 17% had bacterial otitis externa, and 6% had Malassezia otitis externa. 14 Otitis externa is most common in cats with feline atopic skin syndrome (formerly ‘non-flea non-food hypersensitivity dermatitis’) relative to cats with food allergy or flea allergy dermatitis, though it can occur with any type of allergic skin disease.38,39 Among cats with feline atopic syndrome, 16–20% had concurrent otitis externa.38,39

Allergic skin disease should be considered in cats where infection recurs after cytologic cure and where other causes have been excluded. Cats with otitis externa owing to allergies are likely to experience pruritus in other body regions, rather than having only otic disease. 39 Control of otitis externa in a patient with allergic skin disease requires the underlying allergy to be addressed.

When evaluating for food allergy in patients with otitis externa, it is important to resolve both infection and inflammation before assessing for response to diet change (and considering dietary rechallenge). This is because secondary infection is not expected to resolve without directed therapy. Additionally, owners may not appreciate worsening inflammation in the absence of infection, so it is recommended that patients be re-evaluated (physical examination and otoscopy) during the dietary rechallenge period.

Disorders of cornification

Idiopathic ceruminous otitis

Idiopathic ceruminous otitis is an overproduction or accumulation of ceruminous debris that may predispose to secondary infections.40,41 It is poorly characterized in the literature, and there is disagreement among dermatologists as to whether it is an independent clinical entity. Idiopathic excessive cerumen production was described in nine cats with lifelong histories of increased cerumen bilaterally without clinical signs of otitis. 15

Idiopathic facial dermatitis of Persian and Himalayan cats

Bond et al described a disorder affecting 13 Persian cats that developed black debris in the hair on their faces, which progressed to erythema and pruritus. 42 Seven (54%) of the affected cats also had otitis externa, characterized by erythema and black waxy debris. The disease was progressive, and no cat responded completely to therapy with glucocorticoids and antimicrobials. In later case reports, affected cats showed a good response to oral ciclosporin, topical tacrolimus, and combination therapy with oral ciclosporin, dexamethasone and aggressive topical therapy.43–45 Though pathophysiology is not well characterized for this disease, the response to immunomodula-tory therapy suggests that there may be an immune-mediated component (see ‘Immune-mediated diseases’ section below).

Hypothyroidism

Spontaneous primary hypothyroidism is rare in adult cats, with only three cases reported in the literature.46–48 In two of these cases, the cats were diagnosed with concurrent chronic otitis externa.47,48 Cats with spontaneous hypothyroidism tend to present with lethargy, weight gain, hypotrichosis, scale and an unkempt haircoat.

Congenital hypothyroidism may occur in kittens, 49 and secondary hypothyroidism may occur as a result of trauma 50 or from treatment of hyperthyroidism.51–53 Otitis externa has not been reported in association with congenital or secondary hypothyroidism in cats.

Sebaceous gland disease

Overall, sebaceous gland disorders are rare in the cat. A case series involving 10 kittens with sebaceous gland dysplasia described crusting within the ear canals and on the pinnal margins, with one kitten developing severe otitis externa secondarily to the condition. 54

Immune-mediated diseases

Proliferative and necrotizing otitis externa

Proliferative and necrotizing otitis externa (PNOE) is a rare disease that affects the concave pinna and ear canal, causing proliferative plaques that develop thick, adherent, tan to dark brown layers of keratinaceous exudate (Figure 3a).28,55–57 Erosions or ulcers develop over time due to the friable proliferative tissue, which can cause pain and pruritus.28,55 Depending on severity, the ear canal may be occluded, predisposing cats to secondary infection.28,55–57

Figure 3.

Proliferative and necrotizing otitis externa in a 1-year-old castrated male Siamese cat; (a) at initial presentation and (b) after 1 month of therapy with oral ciclosporin, topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment, and systemic and topical antimicrobials to treat secondary infection

In one cat, the ear canal was severely affected while the pinna was spared. 58 In a kitten with otitis externa, lesions histologically consistent with PNOE developed on the face, though the canals did not have proliferative or necrotic tissue. 59

Though initially described in kittens under a year old, 55 PNOE has been documented in young adult cats.28,58 This disease may spontaneously resolve in kittens 55 or may persist into adulthood. 28 Biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis.

The most common therapies reported in the literature are topical tacrolimus and topical and systemic glucocorticoids.28,56–58,60 One of the authors (CC) has successfully treated a few severely affected young adult cats with systemic ciclosporin (Figure 3b). The clinician should evaluate for secondary infection and address it if present.

Pemphigus foliaceus

Pemphigus foliaceus (PF) is the most common autoimmune skin disease of cats. 15 Though 80–92% of cats with PF have pinnal lesions, the ear canal is less frequently affected.61–63 Otitis externa has been reported in 7–30% of cats with PF.63,64 Most cats with PF have lesions affecting multiple sites.61–63 The primary lesion of PF is a subcorneal pustule, but these are prone to rupture, so crusts, erosions, alopecia and erythema are more often seen clinically.62,63 Otitis externa secondary to PF typically resolves with infection control and treatment of the underlying disease.

PF is most commonly treated with cortico-steroids, and monotherapy is effective at inducing remission in 62–70% of affected cats.61–63 If corticosteroid monotherapy is insufficient or steroid side effects occur, an alternative or secondary immunomodulatory medication may be used. 62 The immuno-modulatory agents with the strongest evidence in feline PF are ciclosporin and chlorambucil.61,62 Relapse is common in cats with PF, occurring in 27–95% of cases, particularly when medications are tapered or discontinued.61–64

Factors predisposing to otitis

Treatment errors

Healthy cats may have dark ceruminous debris, 15 which can lead owners and veterinary staff to clean or treat these ears unnecessarily. Cleansing or treating a healthy ear is not recommended because it can variously interfere with the ear’s natural cleansing mechanisms, cause mechanical trauma, add moisture or result in a contact reaction. 40

Obstructive ear disease

Inflammatory aural polyps

Inflammatory aural polyps (IAPs) are benign nodules originating from the epithelium lining the middle ear, nasopharynx or Eustachian tube. Though often visible on otoscopy and, thus, seemingly amenable to traction avulsion, there is frequently a stalk present that extends from the polyp into the medial compartment of the bulla and beyond.65,66 The polyp may be confined to the middle ear, without any extension into the external ear canal. 65 IAPs are most often unilateral,65,67 though a recent study found that 24% of cats with IAPs had them bilaterally. 66

Cats with IAPs may present initially with bacterial otitis externa, which can be refractory to treatment. 66 In addition to signs of otitis externa, affected patients may have vestibular signs, respiratory signs, ocular discharge or blepharospasm, or Horner’s syndrome.66,68 IAPs occur most commonly in young cats and kittens, though they can develop at any age.66,68,69

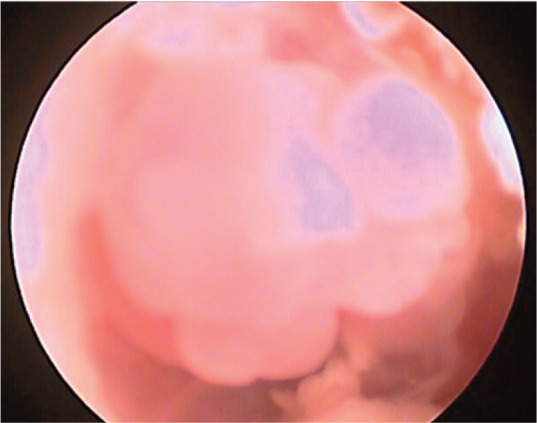

If visible on otoscopy, IAPs often appear as a smooth, pink nodule in the canal at the level of the tympanum (Figure 4). CT is recommended to visualize the extent of the lesion, support the diagnosis and evaluate for bilateral disease.65,66 In one study, 4/6 cats with bilateral IAPs were identified only by CT or video-otoscopy (see box). 66 Definitive diagnosis requires histopathology. 65

Figure 4.

Otoscopic image of an inflammatory aural polyp in the ear canal of a 1-year-old spayed female domestic shorthair cat

Figure 5.

One of the authors (BB) examines the ear canal of a 2-year-old castrated male domestic shorthair cat with otic pruritus using a video-otoscope

IAPs are usually treated in one of two ways: traction avulsion or ventral bulla osteotomy (VBO).66,68 At the time of the procedure, cats should be evaluated for concurrent naso-pharyngeal polyp. 65 Complications may occur with either of these treatment approaches, including Horner’s syndrome, vestibular signs, hemorrhage and facial nerve para-lysis.66,68–70 VBO is more invasive and may carry a greater risk of complications.69,71 Cats with bilateral polyps should be staged to reduce the risk of respiratory complications. 69 IAP recurrence is common and occurs more often in cats that undergo traction avulsion (up to 67%) relative to VBO (5%).66,69,71 In one study, none of the cats that received prednisolone after traction avulsion experienced recurrence, relative to 64% of cats that did not receive a steroid. 71

Two newer techniques have been described to address IAPs. A case series reported a per-endoscopic transtympanic technique for removal of polyps with traction followed by curettage of the bulla, which resulted in a lower rate of recurrence (13.5%) as compared with conventional traction avulsion. 70 Another procedure involved a lateral approach to the ear canal followed by deep traction avulsion. 68 The recurrence rate varied with surgeon experience (14–35%). 68

Neoplasia

Neoplastic disease within the ear canal or middle ear predisposes patients to otitis externa by obstructing the canal and preventing normal self-cleaning. 67 Neoplasia should be considered when unilateral disease is present in an older patient, particularly if secondary infections have not responded as expected to appropriate therapy. 72 In addition to typical signs of otitis, patients with aural neoplasia may have facial nerve paralysis, vestibular signs or pain on opening the mouth.67,73 One study found that cats with neurologic signs at the time of diagnosis had a worse prognosis. 73

The most common aural neoplasm in the cat is ceruminous gland adenocarcinoma (CGA; 374–86% of aural neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; 33%) and carcinoma of unknown origin (CUO; 22%).72,73 SCC and CUO are more locally aggressive and carry a worse prognosis than CGA. 73 Most aural tumors have low metastatic rates, so outcome depends on local disease progression. 73 Cats with CGA have a longer median survival time (49–50 months) than cats with SCC (4 months) or CUO (6 months).72,73

Treatment of otic neoplasia ideally involves surgical resection with a technique such as total ear canal ablation with bulla osteotomy (TECABO). 73 In addition to the potential for definitive cure of the neoplasm, surgery may palliate the patient by removing a source of infection and pain. Depending on the tumor type and surgical margins, radiation or chemotherapy may be recommended after surgery.67,73 Radiation may also be used alone for palliative effect.

Ceruminous gland cystomatosis

Ceruminous gland cystomatosis tends to occur in older cats, though it can occur at any age. Male cats of any breed, and Persians and Abyssinians may be over-represented. 74 Affected cats may have a history of chronic otitis externa. On physical examination, multiple small raised cystic papules to nodules, varying in color from dark brown to gray-blue or purple, are seen in the canal and on the concave pinnae (Figure 6). 74 The number of cysts can range from a few to so many that they obstruct the canal. Diagnosis is often presumptive, though biopsy can be considered if there is concern for malignant neoplasia. Treatment is focused on controlling secondary infections and inflammation. For patients with recurrent infection secondary to cystomatosis, laser ablation is gaining favor among veterinary dermatologists.75,76

Figure 6.

Ceruminous gland cystomatosis in a 12-year-old spayed female domestic mediumhair cat

Cholesteatoma and cholesterol granulomas

There is a single case of feline cholesteatoma in the literature. 77 Two cases of aural cholesterol granuloma have been reported in cats with otitis media,78,79 and cholesterol granu-omas have been experimentally induced in cats.80,81

Perpetuating factors for otitis

Secondary infection with yeast or bacteria

Malassezia otitis

Malassezia species are commonly isolated from the ears of cats with otitis externa, though the exact prevalence varies by report. Malassezia species have been cultured from 58–95% of cats with otitis externa,8–11 meanwhile Malassezia species were identified on cytology in 51% of stray cats with cytological otitis externa in Italy. 16 A greater density of Malassezia species are expected in patients with otitis externa than in normal cats,3,4,7,82 with a mean density of 24 Malassezia organisms per HPF on cytology compared with ⩽2 per HPF in normal cat ears in one study. 3

Bacterial otitis

Cocci and rods were identified in 72% and 29%, respectively, of stray Italian cats with otitis externa, and mixed infections were common. 16 Cocci were commonly seen on cytology in cats with allergy (87% of ear canals). 82 Cocci in cases of feline otitis externa usually belong to Staphylococcus species.83,84 Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pasteurella multocida have been reported as the most common bacterial rods isolated from cats with otitis externa.3,66,83,84 Other organisms isolated from bacterial otitis in multiple cats have included Streptococcus canis, Escherichia coli, Mycoplasma species, Klebsiella species and Corynebacterium species.11,66,85,86

Contact reactions and other complications of treatment

Ototoxicity is a potential risk with many topical medications, particularly if they are permitted to make contact with the inner ear. There are few data regarding the incidence of ototoxicity in cats. 90 Aminoglycosides have induced deafness when administered systemically to cats, 91 and a combination of chlorhexidine and cetrimide was associated with acute vestibular signs in three cats when applied to an ear with a ruptured tympanum. 92

Some veterinary dermatologists consider cats to be especially susceptible to contact reactions with otic preparations, 40 with one veterinary teaching hospital diagnosing contact reactions in 1.4% of patients presenting to its dermatology service. 15 Contact reactions should be suspected when a patient seems to deteriorate clinically after therapy is implemented, and especially if infection is resolved on cytology while the degree of suppurative inflammation worsens.

Topical glucocorticoids cause cutaneous atrophy, which can affect the auricular cartilage in cats, resulting in a potentially permanent drooping appearance to the pinna. 93

Ceruminoliths

Ceruminoliths can form in the ears of cats with chronic otitis externa and are thought to be concretions of debris and possibly ear medication and cleanser.40,41 The ceruminolith tends to be hard with irregular margins, so it can act as a foreign body, perpetuating inflammation and acting as a nidus of infection. 41 True aural foreign bodies are not common in the cat, though they remain a possibility and should be considered in cases of unilateral oti-tis externa. Ceruminoliths typically require removal under general anesthesia, often with otic lavage. 41

Otitis media

While, in dogs, otitis media typically results from otitis externa, cats may have otitis media without otitis externa. Among cats undergoing necropsy, 2–10% had evidence of otitis media on gross evaluation, but 56% had histologic evidence of otitis media.94,95

Affected cats may display head shaking or otic pruritus, or their signs may be exclusively neurologic. Neurologic manifestations of otitis media include vestibular signs (head tilt, ataxia), Horner’s syndrome and facial nerve paralysis. On otoscopic examination, cats with otitis media may have an opaque or bulging tympanic membrane, or fluid may be visible through the tympanic membrane. If fluid is present, it may be clear, purulent or hemorrhagic. 95 Otitis media may occur either unilaterally or bilaterally.94,95

In cases of suspected or confirmed otitis media, fluid from the middle ear should be sampled under general anesthesia via a myringotomy procedure. Otic lavage can be performed if indicated. Advanced imaging (CT) is ideal and should be undertaken prior to myringotomy or otic lavage because lavage adds fluid to the ear canal, which can shadow soft tissue structures.

Aerobic culture is always recommended, and in many cases antimicrobial therapy can wait for culture results. In severe cases, empiric antibiotics can be considered while the culture is pending. Cytology of the fluid from the middle ear can help to guide the selection of an appropriate empiric antibiotic.

Progressive pathologic changes

As a result of chronic otitis externa, patients may develop epidermal hyperplasia, hypertrophy of ceruminous glands and inflammatory infiltrates that result in proliferative tissue filling the ear canal. 67 Though progressive pathologic changes are less commonly reported in cats relative to dogs, ceruminous gland hyperplasia is common in cats with chronic otitis externa and, in one study, was the indication for 30% of cats undergoing TECABO. 72 Ceruminous gland tumors are thought to develop from malignant transformation of glandular hyperplasia, so controlling otic inflammation may serve as a preventive measure. 67

The presence of irregular tissue narrows the canal and can lead to pockets where microorganisms are protected from otic treatments, as well as increased susceptibility to infections due to changes in the skin barrier, disruption of the normal cleaning mechanism in the ear and discomfort for the patient. With chronicity, mineralization and ossification of the canal may occur. In patients with end-stage ear changes, TECABO is recommended; this removes the site of infection and improves patient comfort.

Key Points

Chronic otitis is multifactorial; the factors that contribute to the development and persistence of otitis can be categorized as primary, predisposing and perpetuating.

A successful diagnostic approach involves a combination of history, physical examination with otoscopy, evaluation for Otodectes cynotis and cytology. When appropriate, advanced imaging can be considered.

Because most causes of chronic otitis tend to affect both ears, the presence of unilateral disease should prompt the clinician to evaluate for an inflammatory polyp or mass.

Cytology is vital to identify perpetuating bacterial and yeast infections and guide therapy.

To manage chronic otitis, it is necessary to identify and control as many primary, predisposing and perpetuating factors as possible.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This work did not involve the use of animals and therefore ethical approval was not specifically required for publication in JFMS.

Informed consent: This work did not involve the use of animals (including cadavers) and therefore informed consent was not required. For any animals or people individually identifiable within this publication, informed consent (verbal or written) for their use in the publication was obtained from the people involved.

References

- 1. Tater KC, Scott DW, Miller WH, Jr, et al. The cytology of the external ear canal in the normal dog and cat. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 2003; 50: 370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Little CJL, Lane JG. The surgical anatomy of the feline bulla tympanica. J Small Anim Pract 1986; 27: 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ginel PJ, Lucena R, Rodriguez JC, et al. A semiquantitative cytological evaluation of normal and pathological samples from the external ear canal of dogs and cats. Vet Dermatol 2002; 13: 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tyler S, Swales N, Foster AP, et al. Otoscopy and aural cyto-logical findings in a population of rescue cats and cases in a referral small animal hospital in England and Wales. J Feline Med Surg 2020; 22: 161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hariharan H, Matthew V, Fountain J, et al. Aerobic bacteria from mucous membranes, ear canals, and skin wounds of feral cats in Grenada, and the antimicrobial drug susceptibility of major isolates. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2011; 34: 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crespo MJ, Abarca ML, Cabanes FJ. Occurrence of Malassezia spp. in the external ear canals of dogs and cats with and without otitis externa. Med Mycol J 2002; 40: 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cafarchia C, Gallo S, Capelli G, et al. Occurrence and population size of Malassezia spp. in the external ear canal of dogs and cats both healthy and with otitis. Mycopathologia 2005; 160: 143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nardoni S, Mancianti F, Rum A, et al. Isolation of Malassezia species from healthy cats and cats with otitis. J Feline Med Surg 2005; 7: 141–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dizotti CE, Coutinho SDA. Isolation of Malassezia pachydermatis and M. sympodialis from the external ear canal of cats with and without otitis externa. Acta Vet Hung 2007; 55: 471–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shokri H, Khosravi AR, Rad MA, et al. Occurrence of Malassezia species in Persian and domestic short hair cats with and without otitis externa. J Vet Med Sci 2010; 72: 293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nardoni S, Ebani VV, Fratini F, et al. Malassezia, mites, and bacteria in the external ear canal of dogs and cats with otitis externa. Slov Vet Res 2014; 51: 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bollez A, de Rooster H, Furcas A, et al. Prevalence of external ear disorders in Belgian stray cats. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 149–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mascarenhas MB, Botelho CB, Manier BSML, et al. An unusual case of feline otitis externa due to sporotrichosis. JFMS Open Rep 2019; 5. DOI: 10.1177/2055116919840810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hill PB, Lo A, Eden CAN, et al. Survey of the prevalence, diagnosis and treatment of dermatological conditions in small animals in general practice. Vet Rec 2006; 158: 533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scott DW, Miller WH, Erb HN. Feline dermatology at Cornell University: 1407 cases (1988-2003). J Feline Med Surg 2012; 15: 307–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perego R, Proverbio D, De Giorgi GB, et al. Prevalence of otitis externa in stray cats in northern Italy. J Feline Med Surg 2014; 16: 483–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. August JR. Otitis externa: a disease of multifactorial etiology. Vet Clin Small Anim 1988; 18: 731–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sotikari ST, Koutinas AF, Leontides LS, et al. Factors affecting the frequency of ear canal and face infestation by Otodectes cynotis in the cat. Vet Parasitol 2001; 96: 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Farkas R, Germann T, Szeidemann Z. Assessment of the ear mite (Otodectes cynotis) infestation and the efficacy of an imidacloprid plus moxidectin combination in the treatment of otoacariosis in a Hungarian cat shelter. Parasitol Res 2007; 101: 35–44.17235547 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Akucewich LH, Philman K, Clark A, et al. Prevalence of ectoparasites in a population of feral cats from north central Florida during the summer. Vet Parasitol 2002; 109: 129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Duarte A, Castro I, Pereira da, Fonseca IM, et al. Survey of infectious and parasitic diseases in stray cats at the Lisbon metropolitan area, Portugal. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 441–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang C, Huang HP. Evidence-based veterinary dermatology: a review of published studies of treatments for Otodectes cynotis (ear mite) infestation in cats. Vet Dermatol 2016; 27: 221-e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Combarros D, Boncea AM, Brément T, et al. Comparison of three methods for the diagnosis of otoacariasis due to Otodectes cynotis in dogs and cats. Vet Dermatol 2019; 30: 334-e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Becskei C, Reinemeyer C, King VL, et al. Efficacy of a new spot-on formulation of selamectin plus sarolaner in the treatment of Otodectes cynotis in cats. Vet Parasitol 2017; 238 Suppl 1: S27–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taenzler J, de Vos C, Rainer KAP, et al. Efficacy of fluralaner against Otodectes cynotis infestations in dogs and cats. Parasit Vectors 2017; 10: 30. DOI: 10.1186/s13071-016-1954-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Machado MA, Campos DR, Lopes NL, et al. Efficacy of afox-olaner in the treatment of otodectic mange in naturally infested cats. Vet Parasitol 2018; 256: 29–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Taenzler J, de Vos C, Rainer KAR, et al. Efficacy of fluralaner plus moxidectin (Bravecto Plus spot-on solution for cats) against Otodectes cynotis infestations in cats. Parasit Vectors 2018; 15: 595. DOI: 10.1186/s13071-018-3167-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mauldin EA, Ness TA, Goldschmidt MH. Proliferative and necrotizing otitis externa in four cats. Vet Dermatol 2007; 18: 370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Matricoti I, Maina E. The use of oral fluralaner for the treatment of feline generalized demodicosis: a case report. J Small Anim Pract 2017; 58: 476–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Duangkaew L, Hoffman H. Efficacy of oral fluralaner for the treatment of Demodex gatoi in two shelter cats. Vet Dermatol 2018; 29: 262. DOI: 10.1111/vde.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Simpson AC. Successful treatment of demodicosis due to Demodex cati with sarolaner/selamectin topical solution in a cat. JFMS Open Rep 2021; 7. DOI: 10.1177/2055116920984386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Beccati MB, Pandolfi PP, DiPalma AD. Efficacy of fluralaner spot-on in cats affected by generalized demodico-sis: seven cases [abstract]. Vet Dermatol 2019; 30: 454. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moriello K. Feline dermatophytosis - aspects pertinent to disease management in single and multiple cat situations. J Feline Med Surg 2014; 16: 419–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moriello KA, Coyner K, Paterson S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dermatophytosis in dogs and cats: clinical consensus guidelines of the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology. Vet Dermatol 2017; 28: 266-e68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goodale EC, Outerbridge CA, White SD. Aspergillus otitis in small animals - a retrospective study of 17 cases. Vet Dermatol 2016; 27: 3-e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Paulin J, Morshed M, Armién AG. Otitis interna induced by Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii in a cat. Vet Pathol 2013; 50: 260–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jacobs GJ, Medleau L, Calvert C, et al. Cryptococcal infections in cats: factors influencing treatment outcome and results of sequential serum antigen titers in 35 cats. J Vet Intern Med 1997; 11: 1–4. DOI: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1997.tb00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hobi S, Linek M, Marignac G, et al. Clinical characteristics and causes of pruritus in cats: a multicentre study on feline hypersensitivity-associated dermatoses. Vet Dermatol 2011; 22: 406–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ravens PA, Xu BJ, Vogelnest LJ. Feline atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study of 45 cases (2001-2012). Vet Dermatol 2014; 25: 95-e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kennis RA. Feline otitis: diagnosis and treatment. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2013; 43: 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rosychuk R. Feline ear disease: so much more than ear mites. Proceedings of the Southern European Veterinary Conference; 2008 Oct 17-19; Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bond R, Curtis CF, Ferguson EA, et al. An idiopathic facial dermatitis of Persian cats. Vet Dermatol 2000; 11: 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fontaine J, Heimann M. Idiopathic facial dermatitis of the Persian cat: three cases controlled with cyclosporine [Abstract]. Vet Dermatol 2004; 15 Suppl 1: 64. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chung TH, Ryu MH, Kim DY, et al. Topical tacrolimus (FK506) for the treatment of feline idiopathic facial dermatitis. Aust Vet J 2009; 87: 417–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Carlotti DN, Viaud S, Douet JY. Efficacy of topical treatment in a case of idiopathic facial dermatitis in a Persian cat [article in French]. Prat Med Chir Anim Cie 2009; 44: 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rand JS, Levine J, Best SJ, et al. Spontaneous adult-onset hypothyroidism in a cat. J Vet Intern Med 1993; 7: 272–276. DOI: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1993.tb01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Blois SL, Abrams-Ogg ACG, Mitchell C, et al. Use of thyroid scintigraphy and pituitary immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of spontaneous hypothyroidism in a mature cat. J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 156–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Galgano M, Spalla I, Callegari C, et al. Primary hypothy-roidism and thyroid goiter in an adult cat. J Vet Intern Med 2014; 28: 682–686. DOI: 10.1111/jvim.12283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Greco DS. Diagnosis of congenital and adult-onset hypothy-roidism in cats. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2006; 21: 40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mellanby RJ, Jeffery ND, Gopal MS, et al. Secondary hypothyroidism following head trauma in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2005; 7: 135–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Welches CD, Scavelli RD, Matthiesen DT, et al. Occurrence of problems after three techniques of bilateral thyroidectomy in cats. Vet Surg 1989; 18: 392–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Peterson ME, Becker DV. Radioiodine treatment of 524 cats with hyperthyroidism. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995; 207: 1422–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nykamp SG, Dykes NL, Zarfoss MK, et al. Association of the risk of development of hypothyroidism after iodine 131 treatment with the pretreatment pattern of sodium pertechnetate Tc 99m uptake in the thyroid gland in cats with hyperthyroidism: 165 cases (1990-2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005; 226: 1671–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yager JA, Gross TL, Shearer D, et al. Abnormal sebaceous gland differentiation in 10 kittens (‘sebaceous gland dysplasia’) associated with generalized hypotrichosis and scaling. Vet Dermatol 2012; 23: 136-e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, et al. (eds). Necrotizing diseases of the epidermis. In: Skin diseases of the dog and cat. 2nd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Science, 2005, pp 79–81. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Momota Y, Yasuda J, Ikezawa M, et al. Proliferative and necrotizing otitis externa in a kitten: successful treatment with intralesional and topical corticosteroid therapy. J Vet Med Sci 2016; 78: 1883–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vidémont E, Pin D. Proliferative and necrotizing otitis in a kitten: first demonstration of T-cell-mediated apoptosis. J Small Anim Pract 2010; 51: 599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Borio S, Massari F, Abramo F, et al. Proliferative and necro-tizing otitis externa in a cat without pinnal involvement: video-otoscopic features. J Feline Med Surg 2012; 15: 353–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. McAullife L, Sargent S, Locke E. Pathology in practice. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2020; 257: 287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Momota Y, Yasuda J, Arai N, et al. Contribution of oral triam-cinolone to treating proliferative and necrotizing otitis externa in a 14-year-old Persian cat. JFMS Open Rep 2017; 3. DOI: 10.1177/2055116917691175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Coyner K, Tater J, Rishniw M. Feline pemphigus foli-aceus in non-specialist veterinary practice: a retrospective analysis. J Small Anim Pract 2018; 59: 553–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bizikova P, Burrows A. Feline pemphigus foliaceus: original case series and a comprehensive literature review. BMC Vet Res 2019; 15: 22. DOI: 10.1186/s12917-018-1739-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jordan TJM, Affolter VK, Outerbridge CA, et al. Clinicopathological findings and clinical outcomes in 49 cases of feline pemphigus foliaceus examined in Northern California, USA (1987-2017). Vet Dermatol 2019; 30: 209-e65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Preziosi DE, Goldschmidt MH, Greek JS, et al. Feline pemphigus foliaceus: a retrospective analysis of 57 cases. Vet Dermatol 2003; 14: 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Oliveira CR, O’Brien RT, Matheson JS, et al. Computed tomo-graphic features of feline nasopharyngeal polyps. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2012; 53: 406–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hoppers SE, May ER, Frank LA. Feline bilateral inflammatory aural polyps: a descriptive retrospective study. Vet Dermatol 2020; 31: 385-e102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sula MJM. Tumors and tumorlike lesions of dog and cat ears. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2012; 42: 1161–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Janssens SDS, Haagsman AN, Haar GT. Middle ear polyps: results of traction avulsion after a lateral approach to the ear canal in 62 cats (2004-2014). J Feline Med Surg 2017; 19: 803–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wainberg SH, Selmic LE, Haagsman AN, et al. Comparison of complications and outcome following unilateral, staged bilateral, and single-stage bilateral ventral bulla osteotomy in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2019; 255: 828–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Greci V, Vernia E, Mortellaro CM. Per-endoscopic trans-tympanic traction for the management of feline aural inflammatory polyps: a case review of 37 cats. J Feline Med Surg 2014; 16: 645–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Anderson DM, Robinson RK, White RAS. Management of inflammatory polyps in 37 cats. Vet Rec 2000; 147: 684–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bacon NJ, Gilbert RL, Bostock DE, et al. Total ear canal ablation in the cat: indications, morbidity and long-term survival. J Small Anim Pract 2003; 44: 430–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. London CA, Dubielzig RR, Vail DM, et al. Evaluation of dogs and cats with tumors of the ear canal: 145 cases (1978-1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1996; 208: 1413–1418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, et al. (eds). Sweat gland tumors. In: Skin diseases of the dog and cat. 2nd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Science, 2005, pp 665–694. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Duclos D. Lasers in veterinary dermatology. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2006; 36: 15–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Corriveau LA. Use of a carbon dioxide laser to treat cerumi-nous gland hyperplasia in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2012; 14: 413–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Alexander A, Mahoney P, Scurrell E, et al. Cholesteatoma in a cat. JFMS Open Rep 2019; 5. DOI: 10.1177/2055116919848086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ilha MRS, Wisell C. Cholesterol granuloma associated with otitis media in a cat. J Vet Diagn Invest 2013; 25: 515–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Van der Heyden S, Butaye P, Roels S. Cholesterol granuloma associated with otitis media and leptomeningitis in a cat due to a Streptococcus canis infection. Can Vet J 2013; 54: 72–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Goycoolea MV, Paparella MM, Juhn SK, et al. Otitis media with perforation of the tympanic membrane: a longitudinal experimental study. Laryngoscope 1980; 90: 2037–2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hueb MM, Goycoolea MV. Experimental evidence suggestive of early intervention in mucoid otitis media. Acta Otolaryngol 2009; 129: 444–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Pressanti C, Drouet C, Cadiergues MC. Comparative study of aural microflora in healthy cats, allergic cats and cats with systemic disease. J Feline Med Surg 2014; 16: 992–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hariharan H, Coles M, Poole D, et al. Update on antimicrobial susceptibilities of bacterial isolates from canine and feline otitis externa. Can Vet J 2006; 47: 253–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kroemer S, Garch FE, Galland D, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria isolated from infections in cats and dogs throughout Europe (2002-2009). Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2014; 37: 97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Henneveld K, Rosychuk RAW, Olea-Popelka FJ, et al. Corynebacterium spp. in dogs and cats with otitis externa and/or media: a retrospective study. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2012; 48: 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ackermann AL, Lenz JA, May ER, et al. Mycoplasma infection of the middle ear in three cats. Vet Dermatol 2017; 28: 417-e102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Prakash A, Benfield P. Topical mometasone: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in the treatment of dermatological disorders. Drugs 1998; 55: 145–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Sauvé F. Use of topical glucocorticoids in veterinary dermatology. Can Vet J 2019; 60: 785–788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Radlinksy MAG. Advances in otoscopy. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2016; 46: 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Oishi N, Talaska AE, Schacht J. Ototoxicity in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2012; 42: 1259–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Shepherd RK, Martin RL. Onset of ototoxicity in the cat is related to onset of auditory function. Hearing Res 1995; 92: 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Gallé HG, Venker-van Haagen AJ. Ototoxicity of the antiseptic combination chlorhexidine/cetrimide (Savlon): effects on equilibrium and hearing. Vet Q 1986; 8: 56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Torres SMF. Miscellaneous diseases of the pinna. Merck Veterinary Manual. https://www.msdvetmanual.com/ear-disorders/diseases-of-the-pinna/miscellaneous-diseases-of-the-pinna (2013).

- 94. Schlicksup MD, Van Winkle TJ, Hold DE. Prevalence of clinical abnormalities in cats found to have nonneoplastic middle ear disease at necropsy: 59 cases (1991-2007). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2009; 235: 841–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Sula MM, Njaa BL, Payton ME. Histologic characterization of the cat middle ear: in sickness and in health. Vet Pathol 2014; 51: 951–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Moore SA, Bentley RT, Carrera-Justiz S, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcome of presumptive intracranial complications associated with otitis media/interna: a multi-center retrospective study of 19 cats (2009-2017). J Feline Med Surg 2019; 21: 148–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Martin S, Drees R, Szladovits B, et al. Comparison of medical and/or surgical management of 23 cats with intracranial empyema or abscessation. J Feline Med Surg 2019; 21: 566–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]