Abstract

Escherichia coli cells that contain the pss-93 null mutation are completely deficient in the major membrane phospholipid phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). Such cells are defective in cell division. To gain insight into how a phospholipid defect could block cytokinesis, we used fluorescence techniques on whole cells to investigate which step of the cell division cycle was affected. Several proteins essential for early steps in cytokinesis, such as FtsZ, ZipA, and FtsA, were able to localize as bands to potential division sites in pss-93 filaments, indicating that the generation and localization of potential division sites was not grossly affected by the absence of PE. However, there was no evidence of constriction at most of these potential division sites. FtsZ and green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusions to FtsZ and ZipA often formed spiral structures in these mutant filaments. This is the first report of spirals formed by wild-type FtsZ expressed at normal levels and by ZipA-GFP. The results suggest that the lack of PE may affect the correct interaction of FtsZ with membrane nucleation sites and alter FtsZ ring structure so as to prevent or delay its constriction.

To date, a large number of proteins have been demonstrated to be required in the process of septum formation in prokaryotes (for recent reviews, see references 23, 24, and 35). However, the specific involvement of phospholipids in this membrane-associated process has not been investigated, although mutants that are specifically compromised in phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) synthesis also appear to be blocked in cell division as indicated by their filamentation (12, 18, 30). Therefore, PE must play an important direct or indirect role at some stage of the cell division cycle.

Cells with a temperature-sensitive allele of the pssA gene, which encodes phosphatidylserine synthase, have a significantly reduced level of PE. Cells with a null allele of pssA completely lack PE. In both cases, the cells compensate by accumulating highly elevated levels of the anionic phospholipids phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin (CL) (12, 30, 31). The growth arrest phenotype of these mutants can be suppressed by the addition of divalent cations to the growth medium, but the phospholipid composition and the cell division cycle of the cells remain abnormal (12, 30).

Examination of PE-deficient cells carrying the pss-93 null allele by freeze-fracture electron microscopy demonstrated that the resulting filamentous cells were smooth and lacked visible constrictions (32). Two alternative explanations for the cause of filamentation of the PE-deficient cells were suggested: a nonspecific general stress response to change in phospholipid composition or inhibition of division due to a requirement for a specific phospholipid or membrane phospholipid composition in this process (32). Smooth morphology of the filaments would be consistent with a block in cell division due to failure to position the FtsZ ring, which appears to drive cytokinesis and is analogous to the contractile ring in eukaryotic cells (7). Under stress conditions, DNA damage induces the expression of specific division inhibitors which prevent polymerization of cytoplasmic FtsZ (6, 9). The change in phospholipid composition in pss-93 mutants activates a number of stress-inducible, membrane-associated processes (19, 26) consistent with inhibition of division being related to cell stress. On the other hand, among numerous mutants in phospholipid metabolism, only strains with inhibited PE biosynthesis exhibit filamentation (12, 18, 30). This indicates a possible specific role for PE in cell division in Escherichia coli. Recently, a specific role of PE in cytokinesis was shown in CHO-K1 fibroblasts (14).

In the present study, we investigated whether the block in cell division in mutants lacking PE takes place before or after the positioning of the FtsZ ring. Localization of FtsZ in filaments of PE-deficient pss-93 mutants was determined by immunofluorescence and by using FtsZ protein tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP). We found that FtsZ rings were able to localize properly to potential division sites in pss-93 mutant cells, often forming ladderlike structures, but they usually failed to constrict. Interestingly, FtsZ also formed spiral polymers that may be due to alterations in FtsZ assembly properties or positioning of some division sites. The role of phospholipids in the localization, structure, and function of the cell division apparatus is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

In all experiments, PE-containing strains were AD90 (pss-93::Km recA+) made pssA+ by carrying either plasmid pDD72 (pssA+ Cmr) (12) or pMS5 (pssA+ Apr) (36), both of which are temperature sensitive for replication. PE-deficient cells were the two host strains mentioned above cured of the pssA+-containing plasmids as previously described (12). Plasmids pZG, pAG (25), and pZipG carry Cmr and encode GFP fusions of E. coli FtsZ, FtsA, and ZipA, respectively. As with pZG and pAG, the m2 variant of GFP (10) was fused in frame to the penultimate amino acid residue of ZipA, which was isolated by PCR amplification from E. coli genomic DNA and retained its native ribosome binding site. Expression of the chimeric proteins was controlled by Plac and lacIq on the plasmids as described previously (25). The plasmids described above were introduced into strain AD90/pMS5 (PE containing) by electroporation. The procedure was performed in 1-mm gap cuvettes (part no. 610) with an Electro Cell Manipulator 600 electroporation system (Biotechnologies and Experimental Research Inc.) as described in the manufacturer’s directions. Transformed cells were selected on Luria-Bertani (LB) plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (15 μg/ml) followed by curing of plasmid pMS5 (PE deficient). Plasmid pWM711 (this work) carries the Apr gene and the E. coli ftsZ-GFP fusion from pZG; ftsZ-GFP is expressed at low levels from a constitutive vector promoter. pWM711 was introduced into strain AD90 carrying plasmid pDD72 as described above with selection for ampicillin (50 μg/ml) resistance and subsequent curing of plasmid pDD72. The phospholipid composition of all strains was verified as described previously (27).

All strains for microscopic experiments were grown in LB medium or agar supplemented with 50 mM MgCl2 (absolutely required of all PE-deficient strains). In the case of strain AD90 carrying plasmid pZG, pAG, or pZipG, the growth medium was also supplemented with chloramphenicol (5 to 7 μg/ml); in the case of AD90/pWM711 the growth medium was also supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg/ml). All cultures were grown at 30°C since the pssA+-containing plasmids are temperature sensitive for replication. Fresh overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2 to 0.6 for all experiments unless otherwise noted. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 20 to 40 μM was used for induction of GFP-containing chimeric proteins.

Microscopic techniques.

Exponential-phase cultures grown at 30°C were used for all experiments except as otherwise noted. FtsZ immunofluorescent staining of fixed cells was carried out as described previously (1) except that an Oregon green-conjugated mouse anti-rabbit antibody was used as a secondary antibody. Nucleoids of living cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. Colonies formed by overnight growth on agar plates or cells from liquid cultures both carrying GFP-tagged proteins were observed directly by fluorescence microscopy.

Cells were viewed with an Olympus BX60 epifluorescence microscope equipped with a 100-W mercury lamp, standard fluorescein isothiocyanate filter set, and a 100× fluorite oil immersion objective. Images were captured with an Optronics DEI-750 video camera and manipulated in Adobe PHOTOSHOP 3.0.

Samples for scanning electron microscopy were fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde and 2% OsO4 for 1 h and then washed with water and dehydrated with 50, 70, 95, and 100% ethanol. After critical-point drying, samples were coated with a Polaron high-resolution gold sputter coater. The samples were viewed with a JEOL 6100 scanning electron microscope.

Immunoblotting.

Whole-cell French press lysates (made at 6,000 lb/in2) were subjected to Western blot analysis as described elsewhere (26). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against purified FtsZ or GFP (Clontech) were added at a final dilution of 1:1,000 or 1:2,000, respectively. Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (dilution 1:10,000) and the ECL-Western blotting analysis system (Amersham) was used for detection as recommended by the supplier. Protein was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce) in accordance with the manufacturer’s directions.

RESULTS

Nucleoid segregation and FtsZ levels in pss-93 filaments.

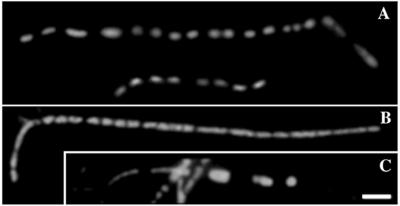

The apparent block of cell division at an early stage in pss-93 mutants prompted us to identify broadly which step in this process might be affected. One possible reason for filamentation is a defect in nucleoid segregation, which is usually coordinated with FtsZ ring positioning at nucleation sites between nucleoids (22). Examination of pss-93 mutant cells revealed that nucleoid segregation was not significantly perturbed in the majority of filaments. A typical cell stained with DAPI exhibiting regularly spaced multiple nucleoids is presented in Fig. 1A and B. Thus, blocking of cell division in such PE-deficient cells was not a consequence of any obvious abnormalities in the segregation of daughter chromosomes. However, in some filaments, larger spacing between nucleoids as well as larger nucleoids were observed, possibly indicating occasional defective segregation (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Nucleoid segregation in pss-93 filamentous cells. The sample was taken from a mid-log-phase culture and stained with DAPI; different examples of nucleoid segregation in pss-93 mutants are shown in panels A to C. Bar, 2 μm.

Another factor which could inhibit the cell division process at an early stage is an alteration in the level of ftsZ expression. It was shown previously that when levels of ftsZ are severalfold below or more than 10-fold above physiological levels, cell division is blocked and filamentous cells that lack normal FtsZ rings are produced (11, 25). However, immunoblot analysis showed no difference in FtsZ protein levels between PE-containing and PE-deficient cells (data not shown), indicating that filamentation in the pss-93 mutants is not due to abnormal FtsZ levels.

Localization of FtsZ in pss-93 filaments.

To determine if and where FtsZ was localized in pss-93 mutant cells, we used immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM) with anti-FtsZ antibodies as well as visualization of FtsZ in living cells by means of FtsZ protein tagged by GFP. In these experiments, cells were taken from either mid-logarithmic to late logarithmic phase cultures or freshly grown colonies on plates.

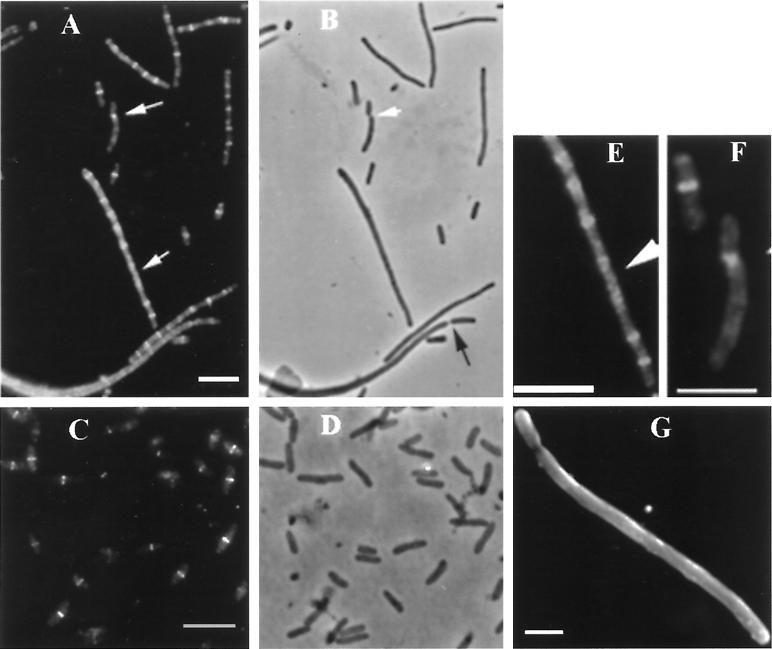

Microscopic examination (Fig. 2A and B) revealed that cells with the pss-93 allele displayed heterogeneous cell lengths, varying from the wild-type length of several micrometers to about 50 times this length, indicating that the process of cell division is strongly inhibited in these cells. On the basis of phase-contrast light microscopy, the majority of the filaments had smooth morphologies (Fig. 2B). This result is consistent with a previous report (32). Examination of PE-deficient cells by scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 2G) supported these results; however, minor indentations could not be excluded completely. Some filaments had one or two visible division constriction sites per filament which usually were located several micrometers from a pole (Fig. 2B and G). These constrictions were consistent with the approximate length of a wild-type cell and supported the idea of asymmetric but not pairwise division in these filaments (13). Cultures usually contained occasional normal-sized cells with a normal constriction at the midpoint. On the other hand, the pss-93 mutant strain containing the covering plasmid pDD72 (normal PE levels) appeared to undergo normal cell division (Fig. 2C and D).

FIG. 2.

FtsZ localization in the PE-deficient mutant pss-93. (A to D) Photomicrographs are arranged in pairs, with immunofluorescence photomicrographs on the left (A and C) and phase-contrast photomicrographs on the right (B and D); (A and B) AD90 (PE deficient); (C and D) AD90/pDD72 (PE containing). The arrows in panel A highlight spiral FtsZ. (E and F) Higher magnifications of the areas of panel A highlighted by arrows. The white arrow in panel B highlights a twisted constriction site. The black arrow in panel B indicates a normal constriction site in a filament. Bars, 5 μm. (G) An analysis of a pss-93 filamentous cell by scanning electron microscopy. Bars, 1 μm.

In IFM experiments, fluorescent bands corresponding to FtsZ could be observed in both short and long pss-93 cells (Fig. 2A). In many filamentous cells, multiple bands of FtsZ formed ladderlike arrays at regular intervals along the entire length of the filaments. These bands are likely FtsZ ring structures, and such multiple bands in filamentous cells were previously reported in E. coli (1, 25) and in aerial mycelia of Streptomyces (38). However, some cells contained FtsZ bands that were not perpendicular to the long axis of the cell which could represent part of a spiral structure. Importantly, distinct spiral structures could be directly observed in filamentous cells (Fig. 2E). These structures were either compact spirals localized apparently at potential division sites or longer spirals (Fig. 2E). An FtsZ polymer organized in the form of a triangle was found in one apparently twisted constriction site (Fig. 2F), suggesting that this was a spiral form of the dividing septum. This was a rare event since of 100 cells analyzed, only one cell with such a division site was observed. Poles of the majority of the filaments appeared normal, with rounded hemispherical morphology, but a few cells had altered poles, such as blunt ends with protrusions or indications of minicell formation (data not shown). These features are reminiscent of the morphology of the ftsZ26 mutant which displays a spiral septum (4, 8). Double staining of the pss-93 filaments with anti-FtsZ antibodies and DAPI showed that bands and short spirals were localized between nucleoids. When long spirals occurred, they filled longer empty spaces between nucleoids in most cases, but occasionally long spirals were seen in association with chains of poorly separated nucleoids (data not shown). The number of FtsZ bands in cells of different lengths was quantitated (Fig. 3). Either single bands, which most likely represent FtsZ rings, or short spirals localized at regular intervals along the filaments were counted as individual bands. The average distance between bands was about 2.5 μm. A number of the very long filaments (100 times wild-type length) only had a few rings (data not shown), possibly indicating that disassembly of the rings eventually occurs in older cells if constriction is not initiated. These could also be dead cells.

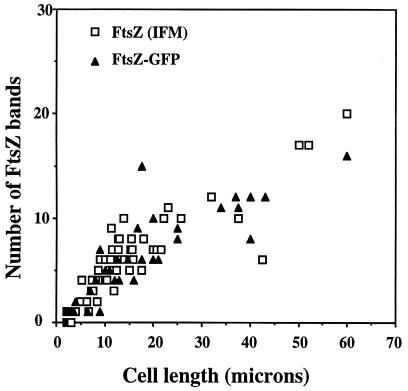

FIG. 3.

Dependence of frequency of FtsZ and FtsZ-GFP localization on cell length. In IFM experiments, individual cells from several fields were measured and scored for the number of bands. In the case of FtsZ-GFP, only cells which did not form aggregates were analyzed.

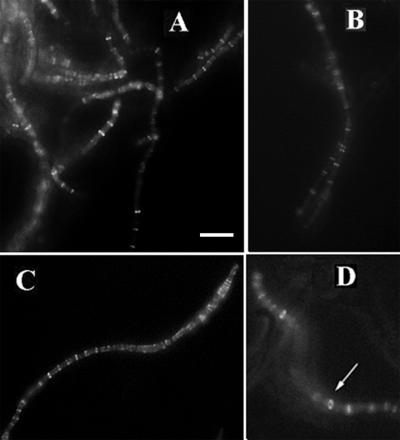

Results with the FtsZ-GFP fusion protein in living cells were, in general, consistent with results obtained by immunofluorescence on fixed cells. When expressed at low levels in E. coli cells, FtsZ-GFP can colocalize with FtsZ protein to allow visualization of cytoskeletal structures in living cells (25). Figure 4A depicts live PE-deficient cells in which FtsZ-GFP was expressed from plasmid pWM711. Western blot analysis demonstrated that the level of expression of the tagged protein was severalfold lower than the physiological level of FtsZ protein (data not shown). Live pss-93 mutant filamentous cells tend to form large aggregates in LB medium supplemented with magnesium, making analysis of the microscopic field difficult; however, many cells had ladderlike multiple bands at regular intervals along the filaments similar to those observed with IFM. Several separate cells showing different fluorescence patterns such as bands and combinations of bands and spirals are presented in Fig. 4B to D. The FtsZ structures shown in Fig. 4B (bands) and C (bands and spirals) are analogous to those in Fig. 2A. Similar results were obtained when FtsZ-GFP was expressed under the regulation of Plac on plasmid pZG containing lacIq (25) in cells grown on agar plates in the presence of 20 μM IPTG. A fluorescent structure is visible in one filament that is turned at an angle which is consistent with a ring (Fig. 4D), supporting the idea that the FtsZ bands in the pss-93 mutant represent actual FtsZ rings and do not represent very short spirals. We also observed some very long spirals that most likely were a result of the GFP fusion (data not shown). A number of separate cells (which did not form aggregates) were scored for cell length and number of FtsZ bands (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 3, the average distance between FtsZ-GFP bands is similar to that obtained by IFM (about 2.5 μm).

FIG. 4.

FtsZ-GFP localization in the PE-deficient mutant pss-93. (A) General view of living mid-log-phase cells grown in LB-Mg medium with expression of FtsZ-GFP from pWM711; (B and C) individual pss-93 cells with multiple FtsZ-GFP bands (B) and bands and spirals (C); (D) pss-93 cells expressing FtsZ-GFP from plasmid pZG taken from LB-Mg plates supplemented with 20 μM IPTG. The arrow in panel D indicates the FtsZ ring structure. Bar, 5 μm.

Localization of ZipA-GFP and FtsA-GFP in pss-93 filaments.

Despite the presence of spiral structures, the presence of ladders of FtsZ rings in the PE-deficient mutant filaments indicated that the major cause of filamentation was downstream of FtsZ ring formation and placement. This prompted us to determine whether ZipA and FtsA, two essential cell division proteins that localize early to the FtsZ ring (3, 17, 25), could also be properly targeted to division sites in the pss-93 mutants. The localization of these proteins was also important because they are both associated with the inner membrane, with ZipA implicated as a possible membrane anchor for FtsZ (17). We studied localization of these proteins by using fusions with GFP, which for both proteins results in a fluorescent ring at the midpoint of wild-type dividing cells (17, 25).

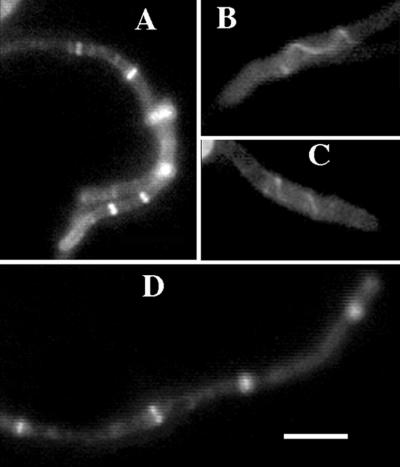

ZipA-GFP under Plac regulation was expressed in PE-deficient cells from plasmid pZipG by the addition of 40 μM IPTG to cultures at an OD600 of about 0.6, and samples for microscopic examination were taken 1 to 2 h later (the generation time under these conditions was about 1 h). ZipA-GFP failed to localize in detectable amounts in about half of the filaments examined. The most common pattern was one or two bands of ZipA-GFP near the cell poles (data not shown). Since the dividing septum in PE-deficient cells was more frequently located close to the ends of the filament, localization of ZipA-GFP close to the poles of the cell could reflect incorporation of tagged protein into the most recently assembled FtsZ ring or currently active division site. The lack of the localization of ZipA-GFP elsewhere in cells could reflect a real failure of ZipA to properly localize in the mutant or perhaps the inability of the newly synthesized ZipA-GFP fusion protein to readily incorporate into preformed FtsZ-ZipA complexes. When IPTG was added to the culture at an OD600 of about 0.2 and samples were taken after 4 h of growth, filaments with multiple bands or spirals in the middle of the cell were visible in the culture (Fig. 5A to C), indicating that the latter explanation is more probable. The distances between multiple ZipA-GFP bands in different filamentous pss-93 cells were from about 2.5 to about 10 μm. The observation of ZipA-GFP spirals (Fig. 5B and C) is significant because ZipA-GFP does not form spirals in otherwise-wild-type cells (data not shown) and suggests that ZipA-GFP may be binding to FtsZ spirals; extended FtsZ spirals with a similar morphology were observed by IFM in some pss-93 filaments (data not shown). The photomicrograph also demonstrates the high optical resolution of GFP fluorescence relative to that with IFM.

FIG. 5.

ZipA-GFP and FtsA-GFP localization in the PE-deficient mutant pss-93. (A to C) Individual cells from liquid LB-Mg medium after 4 h of induction of ZipA-GFP from plasmid pZipG with 40 μM IPTG; (D) individual cell after 4 h of induction of FtsA-GFP from plasmid pAG with 40 μM IPTG. Bar, 5 μm.

The behavior of FtsA-GFP in PE-deficient cells was also studied. In wild-type cells, FtsA localizes early to the septum as a peripheral inner membrane protein in a FtsZ-dependent manner (3, 25, 37). Localization of FtsA-GFP at potential division sites in the pss-93 mutant is shown in Fig. 5D. The distances between multiple bands in different cells varied from about 4.5 to about 16 μm. FtsA-GFP spirals were also observed in the mutant cells (data not shown). One possible reason for the lower frequency of ZipA-GFP and FtsA-GFP localization might be that their expression destabilizes a proportion of FtsZ rings, leading to reduced localization of GFP fluorescence. To address this possibility, we examined the localization of FtsZ rings in cells expressing the fusions. PE-deficient cells were grown with continuous induction of Plac-regulated FtsA-GFP or ZipA-GFP; IPTG was added to the culture at an OD600 of about 0.2, and samples were taken after 4 h of growth. FtsZ localization in these cells was then determined by IFM with anti-FtsZ antibody. The filaments contained multiple bands and spirals, but the number of bands per cell was generally lower than that shown in Fig. 2 (data not shown). These results suggest that some disruption of FtsZ rings occurred in pss-93 mutants under conditions of FtsA-GFP and ZipA-GFP expression.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have demonstrated for the first time the localization of the FtsZ cell division protein in filamentous cells of E. coli with a mutation in phospholipid metabolism that results in a defect in cell division. The prevalence of FtsZ ladders throughout the filaments allows us to conclude that the primary septation defect in PE-deficient cells occurs at a step after FtsZ ring formation and does not occur by induction of stress-dependent inhibitors of FtsZ assembly and localization, such as SulA (9). This conclusion is also supported by findings that a pss-93 strain containing a mutant recA gene (AD93) also forms mostly filaments (12). Thus, PE itself or the ratio of PE to anionic phospholipid plays a specific role in E. coli cell division, presumably by directly affecting the septation complex.

In addition to the ring structures, FtsZ spirals were also observed in pss-93 filaments. Short spirals were localized in the same manner as FtsZ rings, namely, between nucleoids at potential division sites. This finding strongly suggests that substitution of PE with anionic phospholipids (phosphatidylglycerol and CL) in the membrane did not affect generation and localization of potential division sites but did affect the polymerization of FtsZ into the correct ring structure, sometimes resulting in abnormal spiral structures. In the case of the ftsZ26 mutant, in which a mutant FtsZ protein forms spirals, two explanations for spiral formation were suggested: (i) altered interaction between FtsZ monomers and (ii) altered interaction of FtsZ with the membrane-associated nucleation site (4). Since we observed spirals with wild-type FtsZ at normal physiological concentrations in a cell with altered phospholipid composition of the cytoplasmic membrane, the second explanation seems more likely. However, whereas the ftsZ26 mutant spiral septum can constrict (4), the spiral FtsZ structures in the pss-93 mutant fail to constrict normally. In this case, long spirals might originate from short spirals during the process of cell growth because the ends of the short spirals might serve as additional polymerization sites.

FtsZ ladders along intermediate-sized filaments probably result from proper assembly of FtsZ rings (Fig. 4D) at potential division sites which cannot productively constrict. Therefore, another primary consequence of substitution of PE with anionic phospholipids is to inhibit a step subsequent to FtsZ localization and polymerization. Our results indicate that FtsA and ZipA are recruited to FtsZ rings in pss-93 mutants. The lower frequency of ZipA-GFP and FtsA-GFP localization might be a result of some disruption of FtsZ rings due to expression of the fusion proteins. In addition, it is known that ftsA mutant cells, in which FtsA protein has low affinity for the FtsZ ring (3), exhibit a regularly indented morphology (1); this suggests that initial constriction can take place in the absence of a fully functional FtsA. Since PE-deficient cells do not exhibit regular ftsA-like indentations, it is likely that the cell division phenotype is due to a block in a step prior to FtsA action. The presence of ZipA-GFP spirals supports the idea that some FtsZ polymers in PE-deficient filaments have a spiral morphology and makes it unlikely that this alteration in FtsZ polymer structure is caused by the failure of FtsZ to interact with ZipA.

Although cationic lipids facilitate polymerization and stabilization of FtsZ in vitro (15), a change in phospholipid composition may not necessarily have a direct effect on FtsZ ring assembly or constriction because FtsZ may interact with the membrane indirectly via ZipA (17). Are there any possible candidates for a link between a perturbation in membrane phospholipid composition and proper FtsZ ring structure and constriction? Any of the bitopic membrane-spanning septation proteins, which include FtsN, FtsL, FtsI, and FtsQ, could be involved because, as with the PE-deficient filaments, ftsN, ftsI, and ftsQ filaments also all contain multiple FtsZ rings that fail to constrict (1, 2, 29). Although FtsZ rings have not been examined in ftsL mutants, it is interesting that ftsL filaments sometimes contain branches, bulges, and other cell wall abnormalities (16) that are also observed in PE-deficient filaments (27a). FtsW, an essential inner membrane protein required for initial constriction of the FtsZ ring (21), is less likely to be directly involved because ftsW filaments contain very few FtsZ rings, presumably because FtsZ is unstable in the absence of FtsW (20).

Another possibility is that phospholipids are involved directly in initiation of cytokinesis. Essential components of natural membranes are lipids that have the potential to undergo a bilayer-to-nonbilayer transition at temperatures near but above the growth temperature (28, 33). Such lipids also impart a reduced radius of curvature to the membrane bilayer. Such physical properties are displayed by CL in the presence of divalent cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, or Sr2+ but not Ba2+) and PE. It has been postulated that the requirement of PE-deficient cells for Ca2+, Mg2+, or Sr2+ (but not Ba2+) at millimolar concentrations (12) and their elevated levels of CL provide the nonbilayer-forming character to the membrane in the absence of PE (33). This property of lipids could be important for membrane fusion processes involved in the formation of membrane adhesion sites (5). Nonbilayer lipids in the outer leaflet of inner membrane and inner leaflet of outer membrane might facilitate contact formation between inner and outer membranes (34). If membrane fusion is involved in cell envelope invagination, and CL in combination with divalent cations is less effective than PE, then inhibition of FtsZ ring constriction could be a possible consequence.

In summary, our results indicate that either PE itself or wild-type phospholipid composition is required for the normal function of a step(s) after FtsZ localization but before visible FtsZ ring constriction. The increase in the frequency of aberrant FtsZ structures may indicate that correct association of FtsZ with nucleation sites may be influenced by membrane phospholipid composition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by NIH grant GM 20478, awarded to W.D., and NSF grant MCB 9513521, awarded to W.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Addinall S G, Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring formation in fts mutants. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3877–3884. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3877-3884.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addinall S G, Cao C, Lutkenhaus J. FtsN, a late recruit to the septum in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:303–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4641833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Addinall S G, Lutkenhaus J. FtsA is localized to the septum in an FtsZ-dependent manner. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7167–7172. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7167-7172.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Addinall S G, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ-spirals and -arcs determine the shape of the invaginating septa in some mutants of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:231–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayer M E. Areas of adhesion between wall and membrane of Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1968;53:395–404. doi: 10.1099/00221287-53-3-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. Analysis of ftsZ mutations that confer resistance to the cell division inhibitor SulA (SfiA) J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5602–5609. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5602-5609.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature (London) 1991;354:161–164. doi: 10.1038/354161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. Isolation and characterization of ftsZ alleles that affect septal morphology. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5414–5423. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5414-5423.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. Cell division inhibitors SulA and MinCD prevent formation of the FtsZ ring. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1118–1125. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1118-1125.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cormack B P, Valdivia R H, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai K, Lutkenhaus J. ftsZ is an essential cell division gene in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3500–3506. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3500-3506.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeChavigny A, Heacock P N, Dowhan W. Phosphatidylethanolamine may not be essential for the viability of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5323–5332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donachie W D, Begg K J. “Division potential” in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5971–5976. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5971-5976.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emoto K, Kobayashi T, Yamaji A, Aizawa H, Yahara I, Inoue K, Umeda M. Redistribution of phosphatidylethanolamine at the cleavage furrow of dividing cells during cytokinesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12867–12872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erickson H P, Taylor D W, Taylor K A, Bramhill D. Bacterial cell division protein FtsZ assembles into protofilament sheets and minirings, structural homologs of tubulin polymers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:519–523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guzman L-M, Barondess J J, Beckwith J. FtsL, an essential cytoplasmic membrane protein involved in cell division in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7716–7728. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hale C A, de Boer P. Direct binding of FtsZ to ZipA, an essential component of the septal ring structure that mediates cell division in Escherichia coli. Cell. 1997;88:175–185. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81838-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawrot E, Kennedy E P. Phospholipid composition and membrane function in phosphatidylserine decarboxylase mutants of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:8213–8220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue K, Matsuzaki H, Matsumoto K, Shibuya I. Unbalanced membrane phospholipid compositions affect transcriptional expression of certain regulatory genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2872–2878. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2872-2878.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khattar M M, Addinall S G, Stedul K H, Boyle D S, Lutkenhaus J, Donachie W D. Two polypeptide products of the Escherichia coli cell division gene ftsW and a possible role for FtsW in FtsZ function. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:784–793. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.784-793.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khattar M M, Begg K J, Donachie W D. Identification of FtsW and characterization of a new ftsW division mutant of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7140–7147. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7140-7147.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring in bacterial cytokinesis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:403–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lutkenhaus J, Addinall S G. Bacterial cell division and the Z ring. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:93–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lutkenhaus J, Mukherjee A. Cell division. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1615–1626. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma X, Ehrhardt D W, Margolin W. Colocalization of cell division proteins FtsZ and FtsA to cytoskeletal structures in living Escherichia coli cells by using green fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12998–13003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mileykovskaya E, Dowhan W. The Cpx two-component signal transduction pathway is activated in Escherichia coli mutant strains lacking phosphatidylethanolamine. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1029–1034. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1029-1034.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mileykovskaya E I, Dowhan W. Alterations in the electron transfer chain in mutant strains of Escherichia coli lacking phosphatidylethanolamine. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24824–24831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27a.Mileykovskaya, E., and W. Margolin. Unpublished data.

- 28.Morein S, Andersson A-S, Rilfors L, Lindblom G. Wild-type Escherichia coli cells regulate the membrane lipid composition in a “window” between gel and non-lamellar structures. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6801–6809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pogliano J, Pogliano K, Weiss D S, Losick R, Beckwith J. Inactivation of FtsI inhibits constriction of the FtsZ cytokinetic ring and delays the assembly of FtsZ rings at potential division sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:559–564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raetz C R H. Phosphatidylserine synthetase mutants of Escherichia coli: genetic mapping and membrane phospholipid composition. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:3242–3249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raetz C R H, Kantor G D, Nishijima M, Newman K F. Cardiolipin accumulation in the inner and outer membranes of Escherichia coli mutants defective in phosphatidylserine synthetase. J Bacteriol. 1979;139:544–551. doi: 10.1128/jb.139.2.544-551.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rietveld A G, Verkleij A J, de Kruijff B. A freeze-fracture study of the membrane morphology of phosphatidylethanolamine-deficient Escherichia coli cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1324:263–272. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(96)00232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rietveld A G, Killian J A, Dowhan W, de Kruijff B. Polymorphic regulation of membrane phospholipid composition in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12427–12433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rietveld V. Ph.D. thesis. Utrecht, The Netherlands: University of Utrecht; 1996. Polymorphic regulation of membrane phospholipid composition in Escherichia coli. Structural and functional aspects; p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothfield L I, Justice S S. Bacterial cell division: the cycle of the ring. Cell. 1997;88:581–584. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81899-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saha S K, Nishijima S, Matsuzaki H, Shibuya I, Matsumoto K. A regulatory mechanism for the balanced synthesis of membrane phospholipid species in Escherichia coli. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60:111–116. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanchez M, Valencia A, Ferrandiz M-J, Sandler C, Vicente M. Correlation between the structure and biochemical activities of FtsA, an essential cell division protein of the actin family. EMBO J. 1994;13:4919–4925. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06819.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwedock J, McCormick J R, Angert E R, Nodwell J R, Losick R. Assembly of the cell division protein FtsZ into ladder-like structures in the aerial hyphae of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol. 1997;22:231–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]