Abstract

The Clostridium josui cipA and celD genes, encoding a scaffolding-like protein (CipA) and a putative cellulase (CelD), respectively, have been cloned and sequenced. CipA, with an estimated molecular weight of 120,227, consists of an N-terminal signal peptide, a cellulose-binding domain of family III, and six successive cohesin domains. The molecular architecture of C. josui CipA is similar to those of the scaffolding proteins reported so far, such as Clostridium thermocellum CipA, Clostridium cellulovorans CbpA, and Clostridium cellulolyticum CipC, but C. josui CipA is considerably smaller than the other scaffolding proteins. CelD consists of an N-terminal signal peptide, a family 48 catalytic domain of glycosyl hydrolase, and a dockerin domain. N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis of the C. josui cellulosomal proteins indicates that both CipA and CelD are major components of the cellulosome.

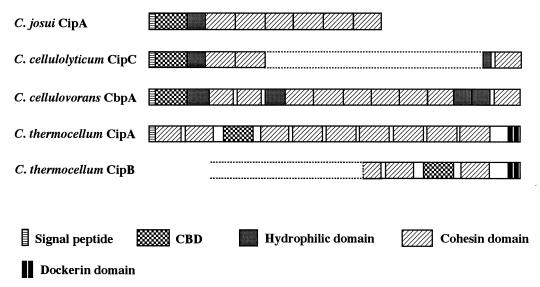

Multienzyme complexes having high activity against crystalline cellulose, known as a cellulosome, have been identified and characterized in cellulolytic clostridia such as Clostridium cellulolyticum (5), Clostridium cellulovorans (8), and Clostridium thermocellum (3, 4, 18) and in anaerobic cellulolytic fungi such as Neocallimastix patriciarum and Piromyces sp. (29). A common feature of the clostridial cellulosomes is that they consist of a large number of catalytic components arranged around noncatalytic scaffolding proteins. The scaffolding proteins have been identified and termed CipA (or scaffoldin) and CipB in C. thermocellum (2, 11, 22), CbpA in C. cellulovorans (27), and CipC in C. cellulolyticum (20). These proteins consist of multiple noncatalytic domains but do not contain any catalytic domains (Fig. 1); e.g., C. thermocellum CipA comprises a cellulose-binding domain (CBD) classified in family III, a docking domain, termed dockerin, and nine cohesin domains (11). Each cohesin domain is a subunit-binding domain which interacts with a dockerin domain of each catalytic component. Therefore, cohesin domains are responsible for integrating catalytic components into the cellulosome (15, 26, 34). C. cellulovorans CbpA is similar to CipA in that both of them contain a family III CBD and nine cohesin domains, although the former contains additional repeated domains of unknown function, termed hydrophilic domains, and does not contain a dockerin domain (27). The strong cellulolytic activity of the clostridial cellulosome systems may be ascribed to the function of the CBD of the scaffolding proteins and/or to the ordered structure of the cellulosomes, because the activity of the dissociated catalytic components was shown to be only 25 to 30% of the activity of the intact cellulosome from C. thermocellum (17).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagrams of the scaffolding proteins responsible for cellulosome assembly. The amino acid sequences of C. cellulolyticum CipC, C. cellulovorans CbpA, and C. thermocellum CipA and CipB were derived from their gene sequences. The complete nucleic acid sequences of C. cellulolyticum cipC and C. thermocellum cipB have not been reported.

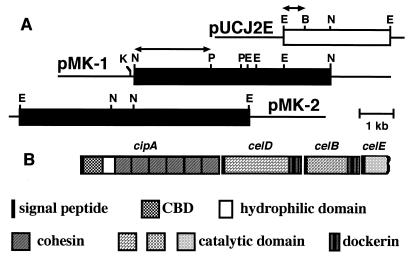

Clostridium josui is a moderately thermophilic cellulolytic bacterium (28). Previously, we cloned a cluster of cellulase genes (9), the celB gene encoding endoglucanase CelB (formerly EG-2), classified into family 8 of glycosyl hydrolases (12), and two incomplete open reading frames (ORFs), ORF1 and ORF2 upstream and downstream of celB, respectively (Fig. 2). The presence of the dockerin domain sequences in the amino acid sequences deduced from celB and ORF1 strongly suggests that C. josui also secretes the cellulosome into the culture medium, although the C. josui cellulosome has not yet been characterized. The organization of this gene cluster, ORF1-celB-ORF2, is similar to that of the cellulase gene cluster, celF-celC-celG, from C. cellulolyticum (5, 9) although the physiological characteristics of C. josui (28) isolated from compost in Thailand are significantly different from those of C. cellulolyticum (21) in several points, especially in optimum growth temperature, i.e., 45°C for the former but 32 to 35°C for the latter. The deduced amino acid sequences of the gene products of ORF1, celB, and ORF2 exhibit extremely high sequence identities—89.9, 92.3, and 96.1%—with those of CelF, CelC, and CelG, respectively, from C. cellulolyticum. In C. cellulolyticum, the cipC gene, encoding a scaffolding protein, was identified upstream of the celF gene and a part of this gene was cloned by an inverse PCR technique (20). These findings suggested that the gene encoding a scaffolding protein of C. josui exists in the region upstream of ORF1.

FIG. 2.

Restriction maps of pMK-1 and pMK-2 (A) and the gene cluster of cipA, celD, celB, and celE (B). Thin lines correspond to vector plasmid DNA. Arrows indicate DNA fragments used as probes for Southern and Northern hybridizations.

In this study, we report cloning and DNA sequencing of the cipA gene encoding the scaffolding protein and the celD gene, formerly ORF1, of C. josui. We also describe the existence of the CelD and CipA proteins as major components of the C. josui cellulosome.

Cloning and DNA sequencing of the celD and cipA genes.

Plasmid pUCJ2E is a pUC118 derivative that contains a 3.8-kb EcoRI fragment (9) carrying the celB gene along with the two incomplete ORFs of C. josui (Fig. 2). Southern hybridization analysis with the EcoRI-BamHI fragment of pUCJ2E as a probe indicated that NheI digestion of C. josui chromosomal DNA gave a 5.8-kb fragment which was associated with the probe (data not shown). Therefore, we cloned this fragment into the XbaI site of pBluescript II KS+ (Stratagene) upon screening by colony hybridization with the same probe. The recombinant plasmid obtained was named pMK-1 (Fig. 2). DNA sequencing of the genomic DNA insert of pMK-1 revealed that the ORF of cipA extended beyond the 5′ end of this DNA fragment, although the full-length celD gene and a part of cipA encoding the C-terminal region of CipA were contained in this region. Southern hybridization was carried out again, with the 2.0-kb NheI-PstI fragment of pMK-1 as a probe, to determine the restriction sites upstream of the 5.8-kb fragment cloned in pMK-1. As a result, we expected that a 6.0-kb EcoRI fragment would contain the full-length cipA gene, and we isolated this DNA fragment (Fig. 2).

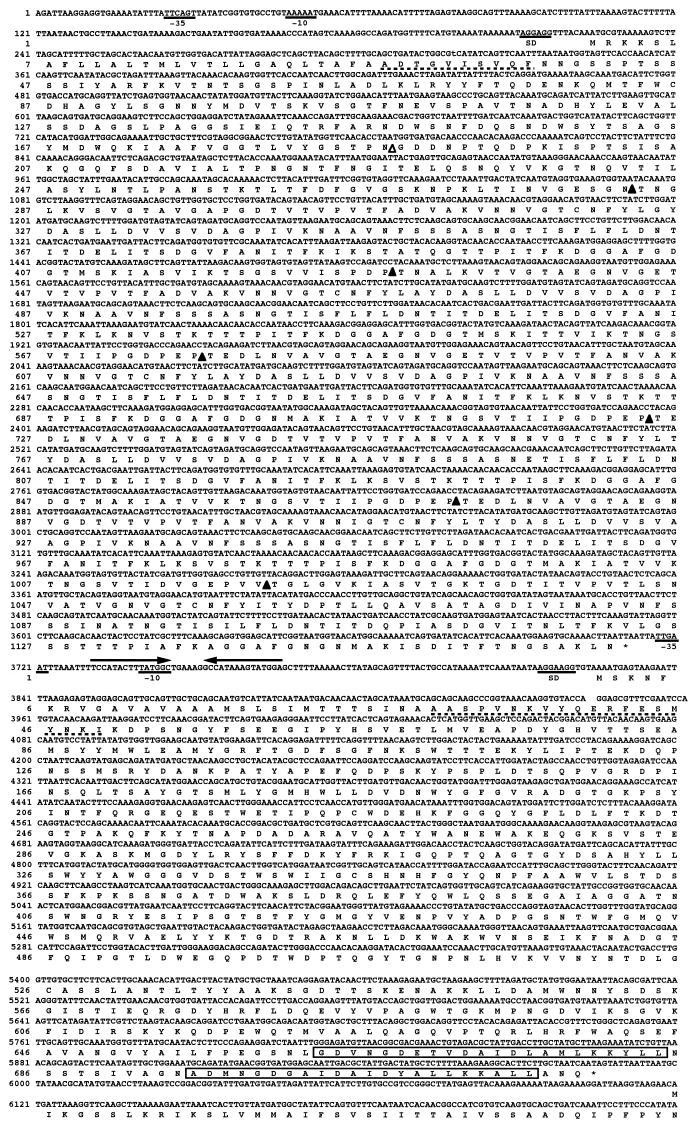

The nucleotide sequences of pMK-1 and pMK-2 were determined with a Licor (Lincoln, Nebr.) model 4000L automated DNA sequencer with appropriate dye primers and a series of the nested deletion subclones. The nucleotide sequence reported was determined at least once in each direction. Sequence data were analyzed with GENETYX computer software (Software Development Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Homology searches in GenBank were carried out with a BLAST program. Figure 3 shows the complete nucleotide sequence containing the full-length cipA and celD structural genes along with their flanking regions. The C. josui cipA gene is the third scaffolding protein gene whose complete nucleotide sequence has been determined.

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of cipA and celD. The putative promoter and Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequences are underlined. The amino acid stretches marked with a broken line were identified in the cellulosomal proteins by automated gas-phase sequencing. A palindrome is indicated by arrows facing each other. The duplicated sequences in the dockerin domain are boxed. ▵, boundary between a CBD and a hydrophilic domain; ▴, boundary between a hydrophilic domain and a cohesin domain or between two contiguous cohesin domains.

The ORF of cipA consists of 3,486 nucleotides encoding a scaffolding-like protein, CipA, of 1,162 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 120,227. The correctness of the position of the initiation codon was supported by the N-terminal amino acid sequence of one of the major components of the C. josui cellulosome (see below). The putative initiation codon ATG was preceded at a spacing of 7 bp by a potential ribosome-binding sequence (AGGAGG) (14). Possible promoter sequences, TTCAGT for a −35 region and AAAAAT for a −10 region with 17 bp between them, were observed; these are homologous with the consensus promoter sequences for the ς70 factor found in Escherichia coli (TTGACA and TATAAT with 17-bp spacing) (25). Downstream of the termination codon TAA, we found a 15-bp palindromic sequence corresponding to an mRNA hairpin loop, a possible transcription terminator, with a ΔG of −30 kcal/mol (ca. −126 kJ/mol) (Freier) followed by four T’s but with a spacing of 2 bp.

The ORF of celD consists of 2,157 nucleotides encoding a putative cellulase, CelD, of 719 amino acids, which was classified into family 48 of glycosyl hydrolases, with a predicted molecular weight of 80,287. The position of the initiation codon of celD was also located on the basis of N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis of major components of the cellulosome. The putative initiation codon ATG was preceded at a spacing of 6 bp by a potential ribosome-binding sequence (AGGAAGG). A possible promoter for celD, TTGAAT for a −35 region and TATGGC for a −10 region with a 17-bp spacing, was found upstream of celD. The −10 sequence overlaps the predicted terminator for cipA. It is not clear whether transcription starting from the promoter for cipA terminates at this putative terminator or continues to celD to form a polycistronic mRNA.

Amino acid sequences of CipA and CelD.

The N terminus of the deduced amino acid sequence of CipA contains a typical signal peptide characteristic of bacterial extracellular proteins (32). Comparison of the amino acid sequence of CipA with entries in the SWISS-PROT and PIR sequence databases revealed that the mature CipA has a molecular structure similar to the scaffolding proteins reported so far, C. cellulovorans CbpA (27), C. thermocellum CipA (11), and C. cellulolyticum CipC (20); i.e., it contains a CBD at its N terminus, followed by a hydrophilic domain and six type I cohesin domains (Fig. 1). In general, scaffolding proteins, which comprise a CBD and a number of cohesin domains, are thought to have mainly two functions: first, they bind a series of catalytic subunits together to form a complex through cohesin-dockerin interaction (15, 26, 30, 34); second, they cause the complex to adsorb onto cellulose and, furthermore, may disorder the crystalline structure of cellulose to produce an easily hydrolyzable substrate through the function of its CBD (7). In C. josui CipA, cohesin domains are located in amino acid 284 to 428, 429 to 576, 577 to 724, 725 to 872, 873 to 1020, and 1021 to 1062. Sequence identities between respective cohesin domains are 63 to 97%. In addition, CipA contains a single hydrophilic domain, which is conserved in C. cellulovorans CbpA (27) and C. cellulolyticum CipC (20) but not in C. thermocellum CipA. Despite the overall similarity of the scaffolding proteins, C. josui CipA is different from C. cellulovorans CbpA and C. thermocellum CipA in that the former is considerably smaller than the others; i.e., the numbers of amino acid residues constituting C. josui CipA, C. cellulovorans CbpA (27), and C. thermocellum CipA (11) are 1,162, 1,848, and 1,854, respectively. Although the full-length scaffolding protein gene, cipC, from C. cellulolyticum has not been cloned, DNA fragments encoding the N- and C-terminal regions of CipC were cloned and sequenced (20). The deduced amino acid sequence of the N-terminal region of CipC, comprising a succession of a signal peptide, a CBD, and two cohesin domains, is highly homologous with the corresponding region of C. josui CipA; the overall sequence identity between them is 82.5%. On the other hand, comparison of the C-terminal regions of CipA and CipC revealed an apparent difference (Fig. 1); i.e., the last (sixth) cohesin domain is connected to another (fifth) cohesin domain in C. josui CipA, although in CipC the last cohesin domain is connected to a hydrophilic domain. Furthermore, N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis of the C. cellulolyticum cellulosomal proteins showed that CipC is a protein of 160 kDa (10), which is larger than the predicted molecular mass (120 kDa) of C. josui CipA. These findings indicate that the molecular architecture of CipA is different from that of CipC. The difference can be explained by assuming that C. josui cipA arose from a common ancestral gene of C. josui cipA and C. cellulolyticum cipC through the deletion of the region encoding its C-terminal moiety, since the N-terminal moieties between these scaffolding protein genes are highly conserved.

Sequence analysis of CelD showed that this enzyme consists of a signal peptide, a family 48 catalytic domain, and a dockerin domain at its C terminus. The overall sequence of CelD was highly homologous with C. cellulolyticum CelF (91% sequence identity) (23) and moderately homologous with C. thermocellum CelS (58% sequence identity) (31). Each of them is known to be one of the major catalytic components in the cellulosome of C. cellulolyticum or C. thermocellum. C. thermocellum CelS is believed to play an important role in the efficient degradation of crystalline cellulose, since purification of components from a cellulosome fraction revealed that the combination of two proteins, noncatalytic scaffolding protein S1, now known as CipA, and exoglucanase S8, known as CelS, was able to completely solubilize Avicel but at very low rates (33). C. cellulolyticum CelF, which has recently been defined as a processive endocellulase, also showed hydrolytic activity toward Avicel by itself (24). Presumably, enzymes of family 48, including C. josui CelD, play important roles in clostridial cellulolytic systems.

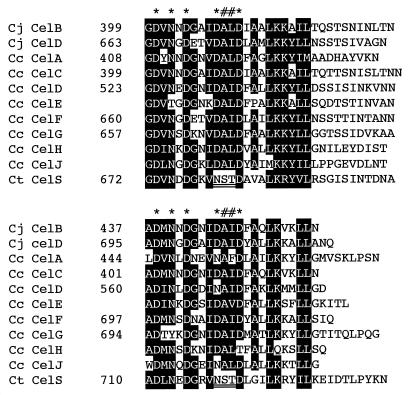

The existence of a dockerin domain in CelD suggested that it is a member of the cellulosomal proteins. Dockerin domains, which consist of two duplicated sequences, each of about 22 amino acid residues, are conserved in the components of cellulosomes from C. cellulolyticum, C. cellulovorans, C. josui, and C. thermocellum. As shown in Fig. 4, the dockerins of C. josui CelB and CelD are similar to those of the C. cellulolyticum cellulases rather than those of C. thermocellum enzymes such as CelS, which has an amino acid sequence typical of this bacterium; i.e., although a DAL or DAI motif is conserved in the dockerins from C. josui and C. cellulolyticum, this motif is replaced by NST in those from C. thermocellum. Recently, Pagès et al. (19) have shown that the cohesin-dockerin interaction in the C. cellulolyticum and C. thermocellum cellulosomes is a species-specific phenomenon, and they have predicted that four amino acid residues, which comprise a repeated pair (AL, AI, or ST) located in the DAL, DAI, or NST motif, are critical to binding specificity as a recognition code.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of dockerin domains of CelB and CelD of C. josui (Cj); CelA, CelC, CelD, CelE, CelF, CelG, CelH, and CelJ of C. cellulolyticum (Cc); and CelS of C. thermocellum (Ct). Sequences of C. cellulolyticum proteins are from reference 19. Asterisks indicate amino acid residues involved in calcium-binding. The NST motifs in C. thermocellum CelS are double underlined. Residues suspected of serving as selectivity determinants are indicated by pound signs (#). Amino acids which are conserved or have similar chemical properties (I, L, M, V, K, R, S, and T) in at least 7 of 10 C. josui and C. cellulolyticum sequences are printed in white on black. Numbers refer to amino acid residues at the start of the respective lines; all sequences are numbered from Met-1 of the peptide. Complete amino acid sequences of CelE, CelH, and CelJ are not known (19).

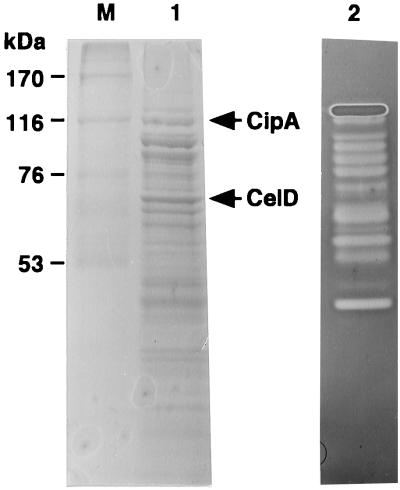

Isolation of the cellulosome from culture of C. josui and identification of CipA and CelD as major components of it.

C. josui was cultivated at 45°C for 7 days in 500 ml of GS medium (13) containing 0.5% ball-milled cellulose as a carbon source. The cells were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was concentrated 50-fold by ultrafiltration through an XM50 membrane (nominal molecular weight cutoff of 50,000) (Amicon). A portion (3 ml) of the concentrated culture supernatant was subjected to HiPrep Sephacryl S-300HR column (16/60) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) chromatography with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 12 mM CaCl2 and 500 mM NaCl as an eluent. A fraction containing protein complexes with a high molecular mass (ca. 700 kDa) was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (16). All protein samples were prepared by heating at 100°C for 3 min in SDS gel loading buffer to denature the proteins. As shown in Fig. 5, a large number of proteins were visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining, and many of them showed endoglucanase activity in the gel containing carboxymethylcellulose as a substrate, by the activity staining assay (1). When the proteins in this fraction were incubated with insoluble cellulose, all of the proteins were bound to the cellulose (data not shown). These results suggest that an extracellular multienzyme complex, cellulosome, may be present in the supernatant of the C. josui culture. After separation of the cellulosomal proteins by SDS-PAGE, the proteins were blotted onto an Immobilon P transfer membrane (Millipore) and subjected to automated amino acid sequencing (model 476A protein sequencer, PE; Applied Biosystems). The N-terminal amino acid sequences of two proteins with molecular masses of 115 and 70 kDa were identified as ADTGVISVQF and AASPVNKVYQERFESMYNKI, respectively, which were found in the amino acid sequences deduced from the cipA and celD genes. These results suggest that CipA and CelD may be components of a C. josui cellulosome and confirm that C. josui CipA is quite smaller than C. cellulolyticum CipC.

FIG. 5.

SDS-PAGE analysis of the cellulase complex from culture fluid of C. josui. Lane 1, Coomassie brilliant blue staining; lane 2, activity staining with carboxymethylcellulose as a substrate; lane M, protein molecular mass standards. Sizes are shown on the left.

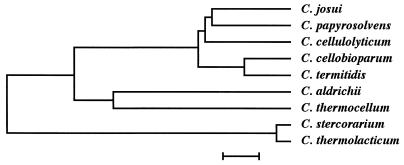

Taxonomic relatedness between C. josui and C. cellulolyticum.

High-level resemblance in the organization of the cellulase gene clusters of C. josui and C. cellulolyticum allows us to expect close taxonomic relatedness between them despite the differences in optimum temperature for their growth, i.e., 45°C for C. josui and 32 to 35°C for C. cellulolyticum. Therefore, we determined the nucleotide sequence of the 16s ribosomal DNA (rDNA) (registered with accession no. AB011057) of C. josui by amplification of rDNA by PCR and direct sequencing of the PCR products. Since C. cellulolyticum was placed in cluster III of the genus Clostridium (6), which consists of cellulolytic species, the 16s rDNA sequences of C. josui and the species of cluster III were aligned and analyzed by the GENETYX computer program. As shown in Fig. 6, the dendrogram places C. josui in cluster III at a position close to C. papyrosolvens and C. cellulolyticum, suggesting that the cellulase gene clusters arise from a common ancestor with some evolutionary modifications.

FIG. 6.

Dendrogram of 16s rDNA sequences of cluster III Clostridium species and C. josui constructed by the GENETYX program. The accession numbers for the rDNA sequences are as follows: C. papyrosolvens, X71852; C. cellulolyticum, X71847; C. cellobioparum, X71856; C. termitidis, X71854; C. aldrichii, X71846; C. thermocellum, L09173; C. stercorarium, L09174; C. thermolacticum, X72870. Bar, 1% sequence divergence.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported herein appear in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession no. AB004845.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly supported by the Bio-Oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution (BRAIN) of Japan. We thank Yasuaki Okamoto of the Tateyama Brewery Co., Ltd., for financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali B R S, Romaniec M P M, Hazlewood G P, Freedman R B. Characterization of the subunits in an apparently homogeneous subpopulation of Clostridium thermocellum cellulosomes. Enzyme Microbiol Technol. 1995;17:705–711. doi: 10.1016/0141-0229(94)00118-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayer E A, Morag E, Lamed R. The cellulosome—a treasure trove for biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 1994;12:379–386. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayer E A, Morag E, Shoham Y, Tormo J, Lamed R. The cellulosome: a cell surface organelle for the adhesion to and degradation of cellulose. In: Fletcher M, editor. Bacterial adhesion: molecular and ecological diversity. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1996. pp. 155–182. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Béguin P, Lemaire M. The cellulosome: an exocellular, multiprotein complex specialized in cellulose degradation. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;31:201–236. doi: 10.3109/10409239609106584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bélaich J-P, Tardif C, Bélaich A, Gaudin C. The cellulolytic system of Clostridium cellulolyticum. J Biotechnol. 1997;57:3–14. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(97)00085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins M D, Lawson P A, Willems A, Cordoba J J, Fernandez-Garayzabal J, Garcia P, Cal J, Hippe H, Farrow J A E. The phylogeny of the genus Clostridium: proposal of five new genera and eleven new species combinations. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:812–826. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Din N, Gilkes N R, Tekant B, Miller R C, Jr, Warren R A J, Kilburn D G. Non-hydrolytic disruption of cellulose fibers by the binding domain of a bacterial cellulase. Bio/Technology. 1991;9:1096–1099. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doi R H, Goldstein M, Hashida S, Park J-S, Takagi M. The Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1994;20:87–93. doi: 10.3109/10408419409113548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujino T, Karita S, Ohmiya K. Nucleotide sequences of the celB gene encoding endo-1,4-β-glucanase-2, ORF1 and ORF2 forming a putative cellulase gene cluster of Clostridium josui. J Ferment Bioeng. 1993;76:243–250. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gal L, Pages S, Gaudin C, Belaich A, Reverbel-Leroy C, Tardif C, Belaich J-P. Characterization of the cellulolytic complex (cellulosome) produced by Clostridium cellulolyticum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:903–909. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.903-909.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerngross U T, Romaniec M P M, Kobayashi T, Huskisson N S, Demain A L. Sequencing of a Clostridium thermocellum gene (cipA) encoding the cellulosomal SL-protein reveals an unusual degree of internal homology. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:325–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henrissat B, Bairoch A. Updating the sequence-based classification of glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem J. 1996;316:695–696. doi: 10.1042/bj3160695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson E A, Sakajoh M, Halliwell G, Madia A, Demain A L. Saccharification of complex cellulosic substrates by the cellulase system from Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:1125–1132. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.5.1125-1132.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knippenberg P H V, Kimmenade J M A V, Heus H A. Phylogeny of the conserved 3′ terminal structure of the RNA of small ribosomal subunits. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;14:4683–4690. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.6.2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruus K, Lua A C, Demain A S, Wu J H D. The anchorage function of CipA (CelL), a scaffolding protein of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9254–9258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morag E, Yaron S, Lamed R, Kenig R, Shoham Y, Bayer E A. Dissociation of the cellulosome of Clostridium thermocellum under nondenaturing conditions. J Biotechnol. 1996;51:235–242. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohmiya K, Sakka K, Karita S, Kimura T. Structure of cellulases and their application. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 1997;14:365–414. doi: 10.1080/02648725.1997.10647949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pagès S, Bélaich A, Bélaich J-P, Morag E, Lamed R, Shoham Y, Bayer E A. Species-specificity of the cohesin-dockerin interaction between Clostridium thermocellum and Clostridium cellulolyticum: prediction of specificity determinants of the dockerin domain. Proteins. 1997;29:517–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pagès S, Bélaich A, Tardif C, Reverbel-Leroy C, Gaudin C, Bélaich J-P. Interaction between the endoglucanase CelA and the scaffolding protein CipC of the Clostridium cellulolyticum cellulosome. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2279–2286. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2279-2286.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petitdemange E, Fond O, Caillet F, Gaudin C. Clostridium cellulolyticum sp. nov., a cellulolytic mesophilic species from decayed grass. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1984;34:155–159. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poole D M, Morag E, Lamed R, Bayer E A, Hazlewood G P, Gilbert J J. Identification of the cellulose binding domain of cellulosome subunit S1 from Clostridium thermocellum YS. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;99:181–186. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90022-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reverbel-Leroy C, Bélaich A, Bernadac A, Gaudin C, Bélaich J-P, Tardif C. Molecular study and overexpression of the Clostridium cellulolyticum celF cellulase gene in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1996;142:1013–1023. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-4-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reverbel-Leroy C, Pagès S, Bélaich A, Bélaich J-P, Tardif C. The processive endocellulase CelF, a major component of the Clostridium cellulolyticum cellulosome: purification and characterization of the recombinant form. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:46–52. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.46-52.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberg M, Court D. Regulatory sequences involved in the promotion and termination of RNA transcription. Annu Rev Genet. 1979;13:319–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.13.120179.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salamitou S, Raynaud O, Lemaire M, Coughlan M, Béguin P, Aubert J-P. Recognition specificity of the duplicated segments present in Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase CelD and in the cellulosome-integrating protein CipA. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2822–2827. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2822-2827.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shoseyov O, Takagi M, Goldstein M A, Doi R H. Primary sequence analysis of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3483–3487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sukhumavasi J, Ohmiya K, Shimizu S, Ueno K. Clostridium josui sp. nov., a cellulolytic, moderate thermophilic species fom Thai compost. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38:179–182. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teunissen M J, Op den Camp H J M. Anaerobic fungi and their cellulolytic and xylanolytic enzymes. Antonie Leeuwenhoek Int J Genet Mol Microbiol. 1993;63:63–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00871733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tokatlidis K, Dhurjati P, Béguin P. Properties conferred on Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase CelC by grafting the duplicated segment of endoglucanase CelD. Protein Eng. 1993;6:947–952. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.8.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang W K, Kruus K, Wu J H D. Cloning and DNA sequence of the gene coding for Clostridium thermocellum SS (CelS), a major cellulosome component. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1293–1302. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1293-1302.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watson M E E. Compilation of published signal sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:5145–5164. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.13.5145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu J H D, Orme-Johnson W H, Demain A L. Two components of an extracellular protein aggregate of Clostridium thermocellum together degrade crystalline cellulose. Biochemistry. 1988;27:1703–1709. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yaron S, Morag E, Bayer E A, Lamed R, Shoham Y. Expression, purification and subunit-binding properties of cohesins 2 and 3 of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:121–124. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00074-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]