Abstract

Context.

Previous studies on quality of life (QOL) after lung cancer surgery have identified a long duration of symptoms postoperatively. We first performed a systematic review of QOL in patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer. A subgroup analysis was conducted focusing on symptom burden and its relationship with QOL.

Objective.

To perform a qualitative review of articles addressing symptom burden in patients undergoing surgical resection for lung cancer.

Methods.

The parent systematic review utilized search terms for symptoms, functional status, and well-being as well as instruments commonly used to evaluate global QOL and symptom experiences after lung cancer surgery. The articles examining symptom burden (n = 54) were analyzed through thematic analysis of their findings and graded according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine rating scale.

Results.

The publication rate of studies assessing symptom burden in patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer have increased over time. The level of evidence quality was 2 or 3 for 14 articles (cohort study or case control) and level of 4 in the remaining 40 articles (case series). The most common QOL instruments used were the Short Form 36 and 12, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score. Thematic analysis revealed several key findings: 1) lung cancer surgery patients have a high symptom burden both before and after surgery; 2) pain, dyspnea, cough, fatigue, depression, and anxiety are the most commonly studied symptoms; 3) the presence of symptoms prior to surgery is an important risk factor for higher acuity of symptoms and persistence after surgery; and 4) symptom burden is a predictor of postoperative QOL.

Conclusion.

Lung cancer patients undergoing surgery carry a high symptom burden which impacts their QOL. Measurement approaches use myriad and heterogenous instruments. More research is needed to standardize symptom burden measurement and management, with the goal to improve patient experience and overall outcomes.

Keywords: Symptoms, quality of life, lung cancer, surgery, pulmonary resection

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most common malignancy, affecting over 2 million new people every year, and it is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide.1 A primary modality of curative intent treatment in early stage non–small cell lung cancer is pulmonary resection through minimally invasive or open surgery. Due to the invasiveness of these approaches and common underlying patient comorbidities, lung cancer surgery patients’ quality of life (QOL) is negatively impacted, largely by reductions in physical and pulmonary functioning as well as residual symptom burden.2 In particular, symptom burden has been shown to last for extended durations postoperatively.3 Therefore, strategies for assessing and addressing symptom burden in clinically meaningful ways are exceedingly important.

As outcomes including short term morbidity and long term survival after surgical resection for lung cancer improve,4–8 the focus of care is shifting to designing interventions for optimizing perioperative QOL. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and other survey instruments have been developed and tested for the purpose of symptom monitoring in this group.9 However, widespread use of PROs for improvement of clinical care in lung cancer surgery patients is hampered by lack of consensus on standardized instruments and delivery modes,10–12 despite pilot trials demonstrating feasibility of routine electronic PRO assessments.13

One reason for this implementation gap may be a lack of knowledge of how symptom burden impacts lung cancer surgery patients and their QOL. In the modern era, minimally invasive lung resections have become standard of care14 and earlier discharges are increasing the priority for overburdened health systems.15 Prior systematic reviews on the topic of QOL lung cancer surgery were completed before 2016 and have focused on studies using a select number of QOL instruments.3,10,16,17 Each of the prior systematic reviews had a relatively small (<20) number of included articles. Therefore, we sought to broadly define our questions and explore major categories of work for emerging themes.

This study presents the findings of a subgroup analysis of articles examining postoperative symptom burden identified from a larger systematic review evaluating QOL of patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer. The analysis of these 54 selected articles helps us to answer the questions “what is the prevalence of symptom burden in lung cancer surgery patients?” and “how does this symptom burden relate to quality of life postoperatively?” and provides an important frame-work to better understand the interplay between lung cancer surgery, symptoms, and quality of life.

Methods

Parent Systematic Review

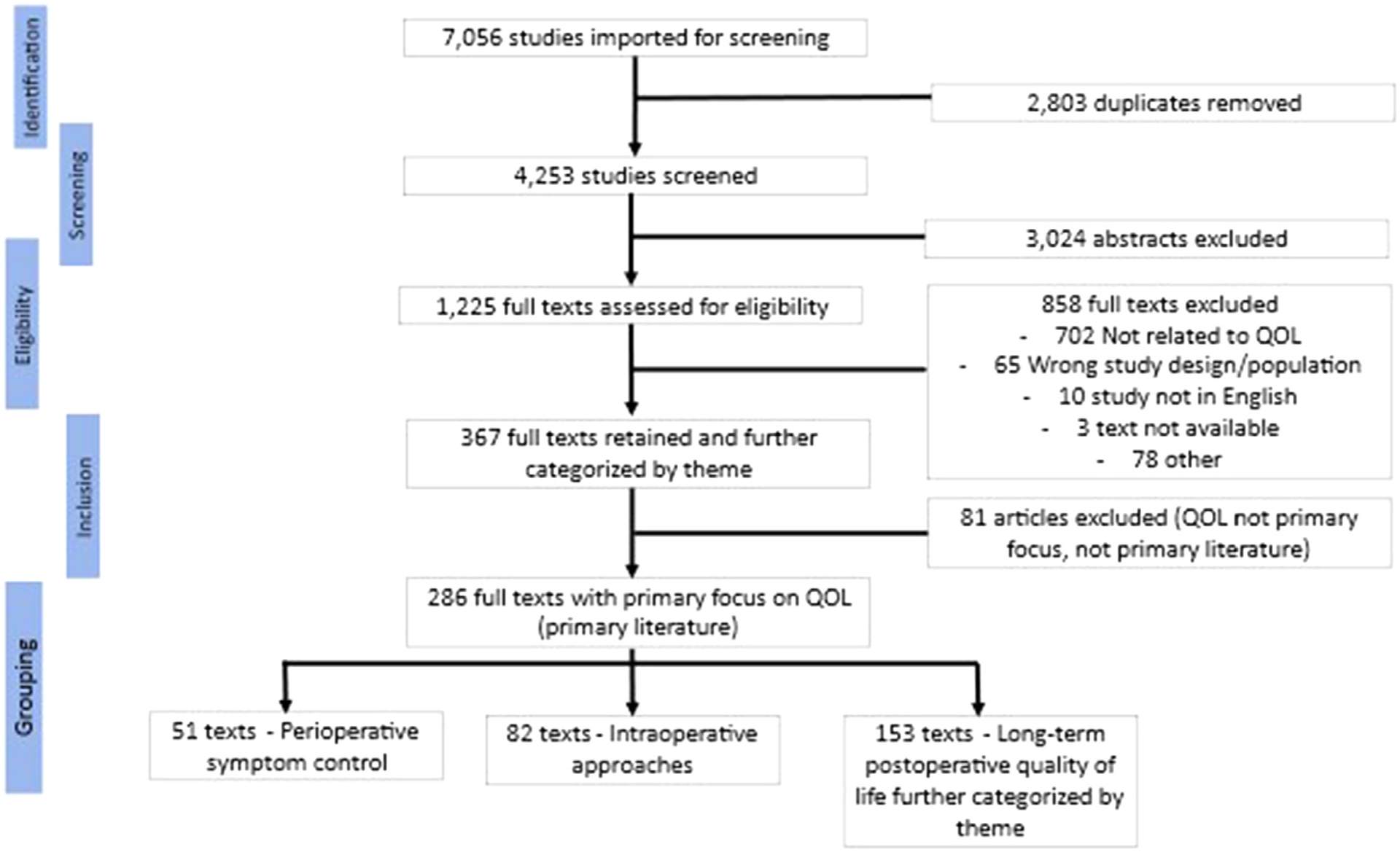

Primary research articles on patients undergoing pulmonary resection for lung cancer who were assessed using QOL instruments were evaluated for inclusion. A medical librarian developed search terms for lung cancer, surgical procedures, and QOL domains including symptoms, functional status, and well-being using subject headings and keywords (Supplemental File 1). These terms were used to search PubMed via the National Library of Medicine, Embase via Elsevier, Web of Science, PsycINFO (via EBSCO), and CINAHL Plus (via EBSCO) from the date of database inception through August 2020. A total of 4253 unique citations were found in all database searches. Every citation was assessed by two authors in an unblinded standardized manner to identify articles (n = 286) focused on the role of QOL in outcomes of lung cancer surgery patients as summarized in the parent study PRISMA diagram. These articles were further grouped by surgical care phases: immediate perioperative management, intraoperative approaches, and long-term postoperative phases (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Parent systematic review PRISMA diagram.

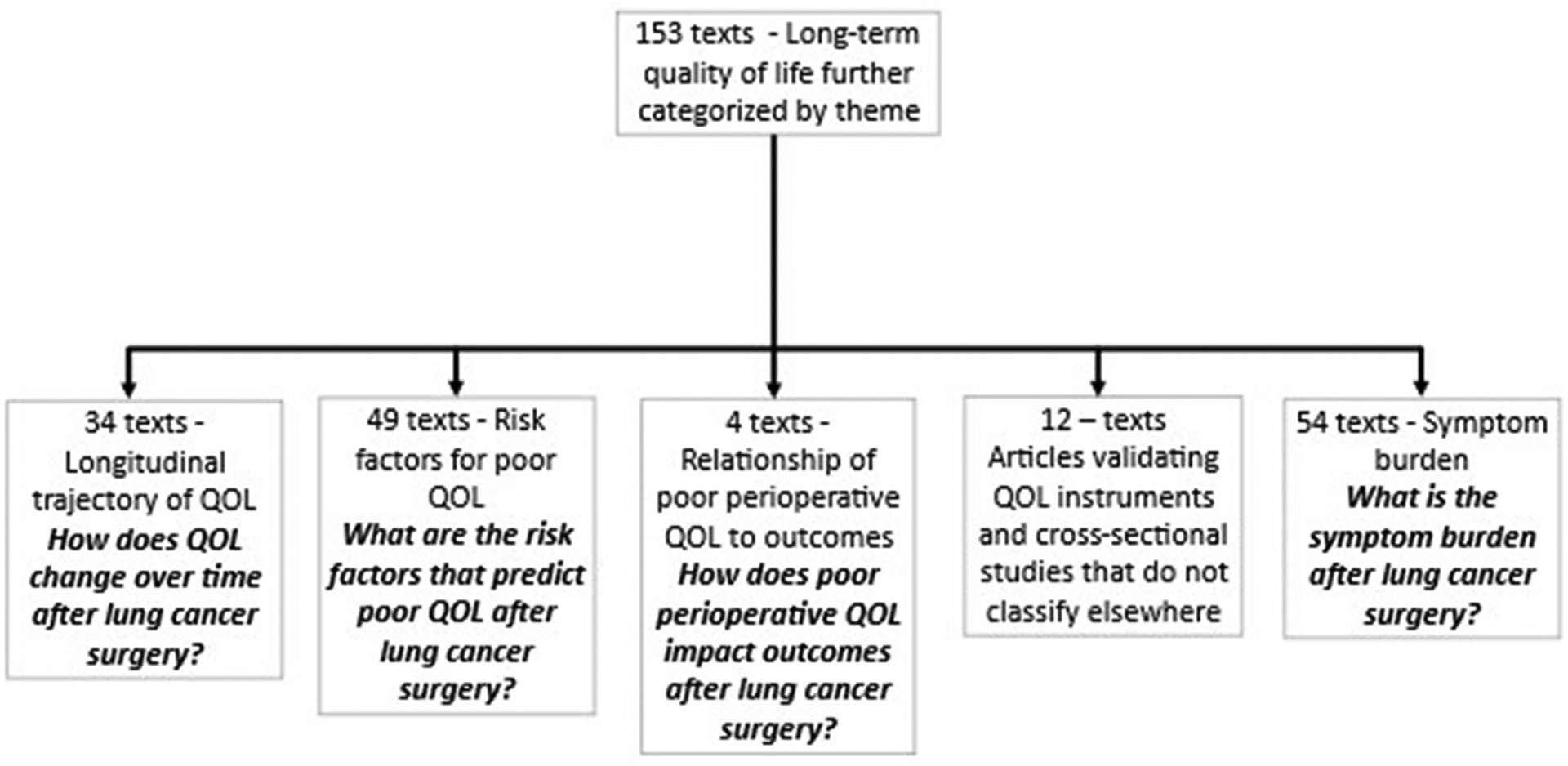

For this work, the postoperative phase grouping (n = 153) was examined further, and these articles were categorized by two members of the study team using thematic analysis (A. M.; G. N. M.; Fig. 2). The identified categories centered on how QOL was framed and examined: 1) the longitudinal trajectory of QOL (n = 34); 2) risk factors for poor postoperative QOL (n = 49); 3) relationship of perioperative QOL with other outcomes (n=4), 4) validation of QOL instruments and other topics (n = 12) and 5) symptom burden in lung cancer surgery patients (n = 54). This study evaluates those 54 articles on symptom burden and its relationship with QOL after lung cancer surgery.

Fig. 2.

Categorization of postoperative QOL articles.

Subset Analysis of Articles Focused on Symptoms

Articles focused on symptoms in patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer were analyzed iteratively through qualitative narrative synthesis of their finding and discussion by two investigators (A.M.; G.N.M) until dominant themes or meanings emerged. In addition, these articles were graded according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine rating scale.18 In brief the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine rating scale is a hierarchical scale. Studies that are randomized and blinded have a lower grade (grade 1) than randomized unblinded trials (grade 2), than cohort studies (grade 3) than do case control studies or case series (grade 4). In addition, the ROBINS-I tool was used to assess risk of bias for the included studies that were not case series.19

Results

Overall Results

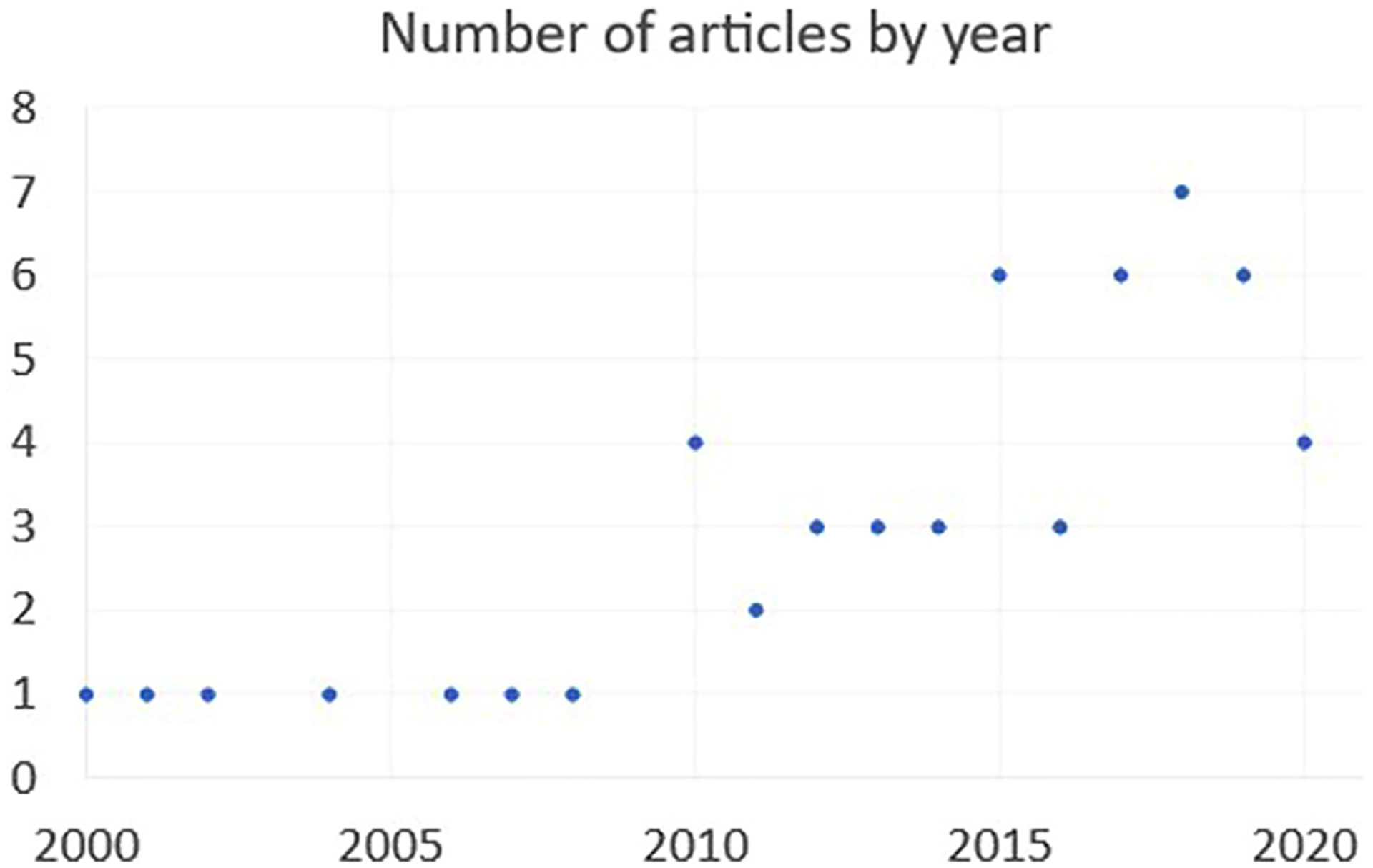

Full text articles (n = 54) assessing symptom burden and QOL in patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer are presented in Table 1, organized by date. The level of evidence quality was 2 or 3 for 14 articles (cohort study or case control) and level of 4 in the remaining 40 articles (case series). There were no studies on symptom burden and QOL with level of evidence quality 1 (randomized control trial or metaanalysis). The trajectory for article publication is in Fig. 3. There is an exponential increase in the number of articles addressing this topic starting in year 2010. There was notable diversity in the QOL instruments used across the studies. A total of 48 different symptom and/or QOL measures were used. The most commonly used measures were SF-36 (n = 12), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score (n = 11), and the EORTC QLQ-LC13or EORTC QLQ-C30. (n = 11) The detailed list of QOL and symptom measurement tools used in all studies is listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Fifty-four Full Text Articles Assessing Symptom Burden in Patients Undergoing Surgery for Lung Cancer

| Author string | Title | Year | Study Type | Study grade | Bias | Year | Country | Patient population | QOL metric | Intervention | Symptom | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shiho et al | Acute and chronic neuropathic pain profiles after video-assisted thoracic surgery: A prospective study | 2020 | Case series | 4 | NA | Not stated | Japan | 27 patients undergoing thoracoscopic lung cancer resection | Numeric rating scale, Douleur Neuropathique 4 (DN4) questionnaire; and Douleur Neuropathique 2 questionnaire | thoracoscopic resection of lung cancer | pain | 20 |

| Yoon et al | Long-term incidence of chronic postsurgical pain after thoracic surgery for lung cancer: a 10-year single-center retrospective study | 2020 | Case control | 4 | Moderate | 2007–2016 | Korea | 3200 patients who underwent thoracic surgery for lung cancer | numeric rating score | lung cancer surgery | pain | 21 |

| Gjeilo et al | Trajectories of Pain in Patients Undergoing Lung Cancer Surgery: A Longitudinal Prospective Study | 2020 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2010–2012 | Norway | 307 patients undergoing surgery for presumed lung cancer divided by those with low baseline levels of pain and high baseline levels | Brief pain inventory; Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire-19 | lung cancer surgery | pain | 23 |

| Gryglicka et al | The patient’s readiness to accept the changes in life after the radical lung cancer surgery | 2020 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2016–2017 | Poland | 135 patients undergoing resection of lung cancer | Acceptance of illness scale; Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | lung cancer surgery | acceptance | 31 |

| Van dams et al | Impact of Health-Related Quality of Life and Prediagnosis Risk of Major Depressive Disorder on Treatment Choice for Stage I Lung Cancer | 2019 | Cohort study | 3 | Moderate | 2004–2013 | United States | 140 patients with stage I non small cell lung cancer who also had major depressive disorder | SF-36 and the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey | 140 patients with stage I NSCLC who have major depressive disorder | depression | 47 |

| Skrzypczak et al | Pneumonectomy – permanent injury or still effective method of treatment? Early and long-term results and quality of life after pneumonectomy due to non-small cell lung cancer | 2019 | Case control | 4 | Serious | 2008–2011 | Poland | 192 patients who underwent pneumonectomy for lung cancer | EORTC QLQ-C30 | pneumonectomy for lung cancer | cough, pain | 29 |

| Hugoy | Predicting postoperative fatigue in surgically treated lung cancer patients in Norway: a longitudinal 5-month follow-up study | 2019 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2010–2012 | Norway | 307 patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer | Lee Fatigue Scale; EORTC QLQ-LC13; Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; General Sleep Disturbance Scale; Brief Pain Inventory | lung cancer surgery | fatigue | 60 |

| Xie et al | Analysis of factors related to chronic cough after lung cancer surgery | 2019 | Case control | 4 | Moderate | 2017–2018 | China | 171 who underwent lobectomy for NSCLC | Leicester Cough Questionnaire, and visual analogue scale for cough | lobectomy for NSCLC | cough, fatigue, depression, sleep disturbance | 44 |

| Shiyko et al | Intra-individual study of mindfulness: ecological momentary perspective in post-surgical lung cancer patients | 2019 | Case series | 4 | NA | 1999–2002 | United States | 59 patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer | Toronto Mindfulness Scale | lung cancer surgery | mindfulness | 82 |

| Ida et al | Preoperative sleep disruption and postoperative functional disability in lung surgery patients: a prospective observational study | 2019 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2016–2017 | Japan | 24 patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer | 12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0; Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | lung cancer surgery | sleep | 63 |

| Huang et al | The structural equation model on self-efficacy during post-op rehabilitation among non–small cell lung cancer patients | 2018 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2015 | China | 238 patients undergoing surgery for non small cell lung cancer | Self-Efficacy Scale for Postoperative Rehabilitation Management of Lung Cancer; FACT-L; HADS; Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; simplified face scale; Medical Coping Modes Questionnaire; Athens Insomnia Scale; VAS; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory | lung cancer surgery | anxiety, depression | 57 |

| Mokhles et al | Treatment selection of early stage non-small cell lung cancer: the role of the patient in clinical decision making | 2018 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2012–2014 | Netherlands | 55 patients with NSCLC undergoing lung resection | Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS) and Control Preferences Scale (CPS), and perceived understanding of information regarding their disease and the treatment, SF-36 | lung resection for lung cancer | pain | 32 |

| Lin and Che | Risk factors of cough in non-small cell lung cancer patients after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery | 2018 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2016–2017 | China | 198 patients with non small cell lung cancer undergoing minimally invasive lung resection | Leicester Cough Questionnaire in Mandarin Chinese (LCQ-MC) | video assisted thoracoscopic lung resection | cough | 42 |

| Ni et al | Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Associated Risk Factors in Patients With Lung Cancer: A Longitudinal Observational Study | 2018 | Case control | 4 | Moderate | 2014–2015 | China | 93 patients newly diagnosed with lung cancer | Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Civilian Version and EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC13 | diagnosis of lung cancer | PTSD, fatigue | 35 |

| Bando et al | Treatment-associated symptoms and coping of postoperative patients with lung cancer in Japan: Development of a model of factors influencing hope | 2018 | Case control | 4 | Serious | Not stated | Japan | 92 patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer | Herth Hope Index, EORTC QLQ-LC13, Japanese version of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations, and Social Support Scale for Cancer Patients | lung cancer surgery | Hope | 45 |

| Malinowska | The relationship between chest pain and level of perioperative anxiety in patients with lung cancer | 2018 | Retrospective cohort study | 4 | Moderate | Not stated | Poland | 150 patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer divided into patients with chest pain preoperatively and those without | Non externally validated survey to assess chest pain and anxiety | lung cancer surgery | pain, anxiety | 34 |

| Chen et al | Self-efficacy, cancer-related fatigue, and quality of life in patients with resected lung cancer | 2018 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2014–2015 | China | 452 patients with NSCLC answering questionnaires regarding QOL, fatigue, and self efficacy | General Self–Efficacy Scale (GSES), Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory–Short Form (MFSI–SF), and Short Form Health Survey (SF–36) | lung cancer surgery | fatigue | 67 |

| Erol et al | Psychiatric assessments in patients operated on due to lung cancer | 2017 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2014 | Turkey | 25 patients undergoing lung resection for lung cancer | Experiences in Close Relationships Scale II, EORTC QLQ C-30, Perceived Family Support Scale, Stress Thermometer and Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale, Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale | lung resection for lung cancer | anxiety, depression | 50 |

| Grigor et al | Impact of Adverse Events and Length of Stay on Patient Experience After Lung Cancer Resection | 2017 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2008–2015 | Canada | 288 questionnaires from patients who underwent resection for lung cancer | Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire | lung resection for lung cancer | satisfaction | 74 |

| Khullar et al | Pilot Study to Integrate Patient Reported Outcomes After Lung Cancer Operations Into The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database | 2017 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2014–2016 | United States | 127 patients undergoing lung resection for lung cancer | PROMIS instruments to assess pain intensity, anxiety, depression, sleep related impairment, ability to participate in social roles, informational and emotional support; cancer-fatigue, cancer-pain interference, and cancer-physical function and mobility | lung resection for lung cancer | pain, anxiety, depression | 13 |

| Halle et al | Trajectory of sleep disturbances in patients undergoing lung cancer surgery: a prospective study | 2017 | Case series | 4 | NA | Not stated | Norway | 307 patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer | General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS) | surgery for lung cancer | sleep disturbance | 65 |

| Banik et al | Enabling, Not Cultivating: Received Social Support and Self-Efficacy Explain Quality of Life After Lung Cancer Surgery | 2017 | Case series | 4 | NA | Not stated | Poland | 102 patients undergoing lung resection for NSCLC | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-LC13, self efficacy scale | surgery for lung cancer | self efficacy | 59 |

| Golden et al | “It wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be”: a qualitative study of early stage non-small cell lung cancer patients after treatment | 2017 | Case series | 4 | NA | Not stated | United States | 11 patients who underwent surgery or stereotactic body radiation therapy for early stage lung cancer | Subjective data | lung resection or stereotactic body radiation therapy | anxiety | 33 |

| Shi et al | Patient-Reported Symptom Interference as a Measure of Post surgery Functional Recovery in Lung Cancer | 2016 | Prospective Cohort study | 2 | Moderate | not stated | United States | 72 treatment-naïve patients with stage I or II NSCLC who were scheduled for thoracic surgery | MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDSI) and SF-12 | lung resection for cancer | pain, nausea, anxiety, sleep, appetite | 69 |

| Park et al | Risk factors for postoperative anxiety and depression after surgical treatment for lung cancer | 2016 | Case control | 3 | Moderate | 2010–2014 | South Korea | 278 patients undergoing curative lung resection for cancer | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | lung resection for cancer | anxiety, depression | 54 |

| Berman et al | Use of Survivorship Care Plans and Analysis of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Multinational Patients With Lung Cancer | 2016 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2010–2014 | Worldwide | 689 lung cancer survivors who created a survivorship care plan by logging into a public website (50% had undergone surgical treatment for their lung cancer) | patient reported outcomes | lung cancer diagnosis | dyspnea, fatigue | 61 |

| Kim et al | Patient perceptions regarding the likelihood of cure after surgical resection of lung and colorectal cancer | 2015 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2003–2005 | United States | 3954 patients identified in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium undergoing colon or lung resection for cancer | Patient reported data collected in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium | lung and colon resection for cancer | hope | 75 |

| Fagundes et al | Symptom recovery after thoracic surgery: Measuring patient-reported outcomes with the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory | 2015 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2004–2008 | United States | 60 patients undergoing lung resection for presumed lung cancer | MD Anderson Symptom Inventory | lung resection for lung cancer | pain, nausea, anxiety, sleep, appetite | 62 |

| Huang et al | Features of fatigue in patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer | 2015 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2005–2010 | China | 254 patients with early stage lung cancer who underwent pulmonary resection | Brief Fatigue Inventory, Physical Activity Questionnaire, Baseline Dyspnea Index, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | lung cancer surgery | fatigue, dyspnea, anxiety, depression | 64 |

| Janet-Vendroux et al | Which is the Role of Pneumonectomy in the Era of Parenchymal-Sparing Procedures? Early/Long-Term Survival and Functional Results of a Single-Center Experience | 2015 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2005–2012 | France | 398 patients undergoing pneumonectomy for lung cancer | SF-12 | pneumonectomy | dyspnea | 39 |

| Oksholm et al | Changes in Symptom Occurrence and Severity Before and After Lung Cancer Surgery | 2015 | Case series | 4 | NA | Not stated | Norway | 228 patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer | Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ-19); Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale | lung resection for cancer | dyspnea, fatigue, pain | 68 |

| Oksholm et al | Trajectories of Symptom Occurrence and Severity From Before Through Five Months After Lung Cancer Surgery | 2015 | Case series | 4 | NA | Not stated | Norway | 285 patients scheduled to undergo surgery for lung cancer | Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale; Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire-19; EORTC QLQ-LC13 | lung resection for cancer | pain, nausea, anxiety, sleep, appetite | 43 |

| Antoniu and Mititiuc | Quality of life following lung cancer surgery: what about before? | 2014 | Prospective cohort study | 2 | Critical | 1997–2000 | Sweden | 132 patients undergoing lung resection compared to coronary artery bypass graft patients | SF-36, hospital anxiety and depression questionnaire, breathlessness questionnaire | lung resection | dyspnea | 56 |

| Jeantieu et al | Postoperative pain and subsequent PTSD-related symptoms in patients undergoing lung resection for suspected cancer | 2014 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2011 | France | 47 patients undergoing lung resection for cancer | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; Impact of Event Scale - Revised to assess post traumatic stress disorder symptoms | lung cancer surgery | anxiety, depression | 37 |

| Lowery et al | Impact of symptom burden in post-surgical non-small cell lung cancer survivors | 2014 | Case series | 4 | NA | Not stated | United States | 183 patients post lung surgery for lung cancer | SF-36; brief pain inventory; brief fatigue inventory; baseline dyspnea index; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | lung cancer resection | fatigue, dyspnea, anxiety, depression | 70 |

| Grosen et al | Persistent post-surgical pain following anterior thoracotomy for lung cancer: a cross-sectional study of prevalence, characteristics and interference with functioning | 2013 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2000–2009 | Denmark | 702 patients undergoing thoracotomy for lung cancer resection | Brief pain inventory | thoracotomy for lung cancer | pain | 28 |

| Koczywas et al | Longitudinal changes in function, symptom burden, and quality of life in patients with early-stage lung cancer | 2013 | Case series | 4 | NA | Not stated | United States | 103 patients with NSCLC (70% underwent lung resection) | Distress thermometer, FACT-L, Lung Cancer Syndrome Index; Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spirituality Tool, The Medical Outcomes Study Social Activity Limitations Scale; The MOS Social Support Survey; Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale | lung cancer treatment | pain, dyspnea | 66 |

| Lin et al | Pain, fatigue, disturbed sleep and distress comprised a symptom cluster that related to quality of life and functional status of lung cancer surgery patients | 2013 | Case series | 4 | NA | Not stated in abstract | China | 145 patients after lung cancer surgery | MD Anderson Symptom Inventory, Karnofsky Performance Scale and Quality of Life Instruments for Cancer Patients - Lung Cancer | Lung cancer surgery | pain, fatigue | 58 |

| Kinney et al | Chronic Post thoracotomy Pain and Health-Related Quality of Life | 2012 | Prospective Case Control | 3 | Low | Not stated | United States | 110 patients undergoing elective thoracotomy (83% for suspected neoplasm) | SF-36; Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) | elective thoracotomy | pain | 27 |

| Yang et al | Quality of life and symptom burden among long-term lung cancer survivors | 2012 | Case series | 4 | NA | 1997–2003 | United States | 447 lung cancer survivors who are alive at least five years after diagnosis (68% underwent surgical resection; 27% combined surgery/chemoradiation) | LCSS | long term survivor of lung cancer | fatigue, pain, dyspnea, cough | 71 |

| Rodríguez-Quintana et al. | Assessment of quality of life, emotional state, and coping skills in patients with neoplastic pulmonary disease | 2012 | Case series | 4 | NA | Not stated | Spain | 121 preoperative patients | EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC-LC13, HADS and Maental adjustment to cancer scale | lung resection for cancer | anxiety, depression, fatigue, pain | 48 |

| Pompili et al | Prospective external convergence evaluation of two different quality-of-life instruments in lung resection patients | 2011 | Prospective cohort study | 2 | Low | 2009 | Italy | 33 post surgical patients | EORTC QLQ-C30 with lung module 13 and SF-36 | lung resection for cancer | fatigue, nausea, pain, dyspnea, insomnia | 40 |

| Guastella et al | A prospective study of neuropathic pain induced by thoracotomy: incidence, clinical description, and diagnosis | 2011 | Case series | 4 | NA | Not stated | France | 54 patients undergoing thoracotomy for surgical treatment of lung cancer | visual analogue scale, douleure neuropathique (DN4) questionnaire | thoracotomy for lung cancer | pain | 26 |

| Rolke et al | HRQoL changes, mood disorders and satisfaction after treatment in an unselected population of patients with lung cancer | 2010 | Prospective cohort study | 2 | Low | 2002–2005 | Norway | 492 patients receiving NSCLC treatment (surgery, chemo, radiation, supportive care) | EORTC QLQ-C30/QLQ-LC13, sense of coherence, hospital anxiety and depression scale | NSCLC post first modality treatment | anxiety, depression | 51 |

| Sarna et al | Women with lung cancer: quality of life after thoracotomy: a 6-month prospective study | 2010 | Prospective Cohort study | 2 | Low | Not stated | United States | 119 NSCLC female survivors between 6 and 6 years post-diagnosis and who received curative surgical treatment (all thoracotomies) | SF-36 | lung resection for cancer | depression, dyspnea | 49 |

| Wang et al | Post-discharge health care needs of patients after lung cancer resection | 2010 | Prospective case control | 3 | Moderate | 2005 | China | 62 patients undergoing lung resection for cancer | Symptom Distress Scale–Chinese Modified Form, Social Support Scale, Health Needs Scale, visual analogue scale | lung resection for cancer | pain | 73 |

| Feinstein et al | Current dyspnea among long-term survivors of early-stage non-small cell lung cancer | 2010 | Case series | 4 | NA | 2005–2007 | United States | 342 patients undergoing lung resection for stage I NSCLC | Baseline Dyspnea Index, Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | lung resection for lung cancer | dyspnea, anxiety, depression | 41 |

| Balduyck et al | Quality of life after lung cancer surgery: a prospective pilot study comparing bronchial sleeve lobectomy with pneumonectomy | 2008 | Prospective cohort study | 2 | Moderate | 2003–2005 | Belgium | 10 patients undergoing sleeve lobectomy and 20 patients undergoing pneumonectomy | EORTC QOLQ-LC13 | sleeve lobectomy or pneumonectomy for lung cancer | dyspnea, pain | 30 |

| Oh et al | Prospective analysis of depression and psychological distress before and after surgical resection of lung cancer | 2007 | Case series | 4 | NA | 1997–2003 | Japan | 165 patients with lung cancer scheduled for surgical treatment | Profile of Mood States questionnaire | lung resection for cancer | depression | 55 |

| Walker et al | Depressive symptoms after lung cancer surgery: Their relation to coping style and social support | 2006 | Prospective Cohort study | 2 | Moderate | 2001–2004 | US | 132 postsurgical patients with early stage NSCLC that smoked 3 months prior to surgery | Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (COPE) scale, Social Support Inventory (SSI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | lung resection for non small cell lung cancer | depression | 53 |

| Sarna et al | Impact of respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function on quality of life of long-term survivors of non-small cell lung cancer | 2004 | Cross Sectional | 2 | Moderate | not stated | United States | 142 disease-free NSCLC survivors (5 years minimum) | SF-36, Division of Lung Disease/American Thoracic Society (ATS) questionnaire (respiratory symptoms) | NA | dyspnea | 38 |

| Myrdal et al | Quality of life following lung cancer surgery | 2002 | Prospective Cohort study | 2 | Moderate | 1997–2004 | Sweden | 194 patients undergoing open surgery for lung cancer compared to matched patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting for coronary artery disease | SF-36, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | lung resection for cancer and coronary bypass | anxiety, depression | 52 |

| Wildgaard et al | Consequences of persistent pain after lung cancer surgery: a nationwide questionnaire study | 2001 | Retrospective Cohort study | 3 | Moderate | 2005–2007 | Denmark | 546 patients undergoing lung resection for cancer divided into those who developed post thoracotomy pain syndrome and those who had not | subjective assessment of impact of pain on ADLs, sleep | lung resection for lung cancer (VATS and thoracotomy) | pain | 24 |

| Goodman | Meeting patients’ post-discharge needs after lung cancer surgery | 2000 | Case series | 4 | NA | Not stated | United Kingdom | 6 patients who held diaries perioperatively while undergoing surgery for lung cancer | Subjective data | surgery for lung cancer | pain | 46 |

Fig. 3.

Number of articles by year analyzing symptom burden.

Table 2.

Quality of Life Outcome Measures and Frequency Used in the 54 Included Articles

| SF-36 or SF-12 | 12 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 or LC-13 | 11 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score | 11 |

| Subjective data | 6 |

| Acceptance of Illness Scale; American Thoracic Society Questionnaire; Athens Insomnia Scale; Baseline Dyspnea Index; Breathlessness Questionnaire; Brief Fatigue Inventory; Brief Pain Inventory; Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale; Control Preferences Scale; Coping Inventory; Decisional Conflict Scale; Douleur Neuropathique 2 or 4; Experiences in Close Relationships Scale II; Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Lung; General Sleep Disturbance Scale; Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire; Herth Hope Questionnaire; Impact of Event Scale; Karnofsky Performance Scale; Lee Fatigue Scale; Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs; Leicester Cough Questionnaire; Lung Cancer Symptom Questionnaire; MD Anderson Symptom Inventory; Medical Coping Modes Questionnaire; Medical Outcomes Study Social Activity Limitations Scale and Symptom Assessment Scale; Mental Adjustment to Care Scale; Mini-Mental State Examination; Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory–Short Form; Numeric Rating Scale; Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Tools; Perceived Family Support Scale; Physical Activity Questionnaire; Picker Patient Experience; Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory; Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Civilian Version; Profile of Moods Questionnaire; Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire-19; Self-Efficacy Scale; Stress Thermometer; Social Support Scale; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Symptom Distress Scale; Toronto Mindfulness Scale; Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey; Visual Analogue Scale; 12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 | <5 |

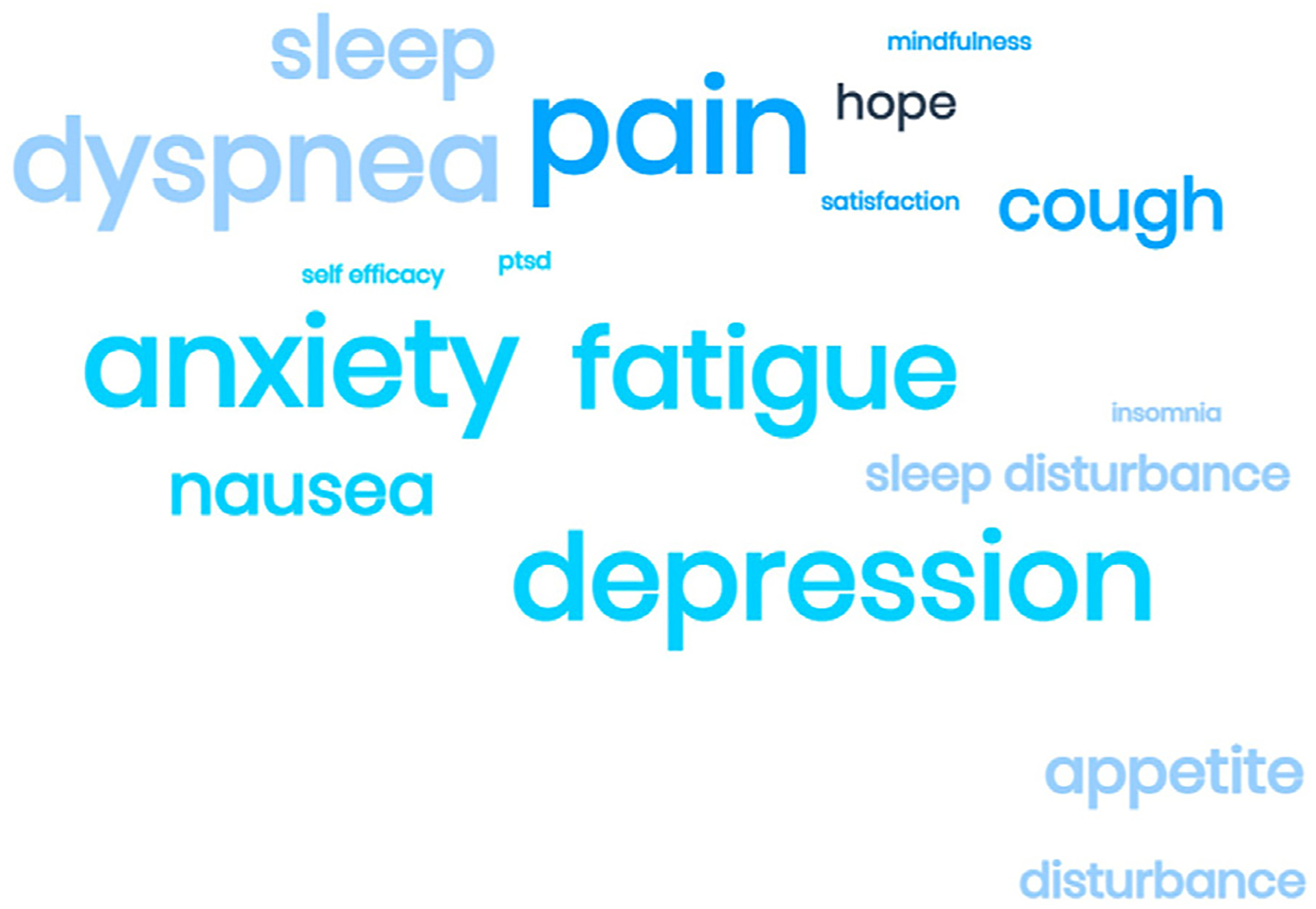

The findings of the articles according to the primary symptoms are discussed below. The frequency of articles addressing each symptom are visually depicted in a word cloud (Fig. 4). We opted to present these findings qualitatively given the overlap of some studies discussing more than one symptom or how symptoms related to each other.

Fig. 4.

Word cloud demonstrating number of articles addressing each symptom concept.

Acute and Chronic Pain.

Acute postoperative pain is expectedly extremely common and increases in the first 1–3 months postoperatively when compared to baseline, but then decreases variably over time.20,21 Two studies report an eventual return to baseline pain in an approximately 6 month time frame,13,22 whereas other studies report that pain persists in as many as 55% of patients at 12 months.23 Chronic pain (typically lasting >2–3 months and known as post-thoracotomy pain syndrome) was discussed in 9 articles.20,21,23–29 Chronic pain may be incisional, radiating (often to the shoulder)30 or neuropathic and affects ~30% of patients after pneumonectomy29 and, in some reports, up to 40% of patients after minimally invasive surgery.20 Patients at risk for chronic postoperative pain are those undergoing posterior lateral thoracotomy compared to those undergoing anterior thoracotomy28 or minimally invasive surgery27 as well as in patients with more comorbidities and preoperative pain.23,31

Chronic pain impacts physical HRQOL and is clinically important in 18% of patients.27 In fact, symptoms such as pain have a greater impact on postoperative QOL than patient’s understanding of treatment plan, involvement in decision making,32 and trust in their physicians.33 Symptoms of pain are associated with anxiety,34 and poorly controlled postoperative pain may impact mental HRQOL through development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related symptoms.35,36 Indeed, up to 50% of patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer experience PTSD.37

Respiratory Symptoms.

Respiratory symptoms (dyspnea and cough) are extremely common and long lasting in lung cancer patients. These symptoms negatively impact physical and emotional QOL more so than objective measures of pulmonary function.38–40 A majority (60%) of patients experience dyspnea even several years after surgery.41 More than a third (37%) of patients develop a cough after surgery that persists for greater than one month.42,43 Predictors of postoperative cough include preoperative COPD.44 Respiratory symptoms may appear in clusters with other symptoms; for example, cough is commonly associated with sleep disturbance.43 Bando et al report that dyspnea and chest pain had a negative influence on emotional HRQOL, specifically by impacting hope.45

Mental Health Symptoms.

The impact of lung cancer diagnosis and surgery on mental health is often not anticipated by patients.46 Mental health impacts outcomes both pre- and postoperatively. Preexisting depression is associated with higher rates of receiving non-operative therapy47 and anxiety and depression are associated with worse postoperative QOL,48 specifically emotional QOL,49 and a higher complication rate.50 Patients with pre-existing anxiety tend to experience mental health symptoms more frequently postoperatively,51 as do patients who continue to smoke.52

Postoperatively, 30% of patients experience depression53 and 19% have anxiety,54 though anxiety is reported to then decrease once surgery is complete.55 Lung cancer surgery patients experience anxiety and depression at higher rates than those after other thoracic procedures such as coronary artery bypass grafting,56 and those who experience these symptoms report lower rates of self-efficacy.57 As psychiatric symptoms tend to appear in clusters with other somatic symptoms58 mental health symptoms may best be treated as a as part of comprehensive cancer support programs. It does seem true that social support has an impact on self-efficacy and related concepts, which in turn has an impact on quality of life.59

Sleep and Fatigue.

Fatigue and sleep disturbance are common in lung cancer surgery patients, including preoperatively due to disease-associated respiratory symptoms and psychiatric symptoms,60–62 but can also last over five months postoperatively.43 Preoperative sleep disturbance is a risk factor for postoperative sleep disturbance.63 Greater than 50% of lung cancer patients experience fatigue64 and 80% poor sleep quality.63 Sleep disturbance worsens until 1 month postoperatively and then returns to preoperative levels.65,66 Fatigue negatively impacts emotional HRQOL (self-efficacy).67

Symptom Clusters.

Lung cancer surgery patients often develop more than one symptom after surgery.68 Symptom clusters may be an important driver of postoperative quality of health. Risk factors for higher interference of symptoms are younger age, more comorbidities, and worse functional status.69 The occurrence of two or more clinically significant symptoms has an adverse impact on HRQOL and functioning,70 and dyspnea, fatigue, cough, pain, and reduced appetite symptom occurrence is linked to declines HRQOL.71 Pain, fatigue, disturbed sleep, and distress co-occur commonly and negatively impact QOL and functional status.72

Symptom burden severity also may be predictive of postoperative health care needs.73 Patients who have a prolonged length of stay report decreased satisfaction upon discharge and also report a lower quality of life postoperatively.74 While 50% of patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer think that the surgery may alleviate cancer related symptoms, only 44% think the surgery may result in side effects or complications.75 Mindfulness programs have been implemented as an attempt to alter the relationship between somatic symptoms and development of anxiety and depression and can be implemented across a broad aspect of lung cancer surgery patients,76 although the impact on QOL is not yet clear. It does seem true that social support has an impact on self-efficacy, which in turn has an impact on quality of life.59

Discussion

Overall, the included studies demonstrate that: 1) lung cancer surgery patients have a high symptom burden both before and after surgery; 2) pain, dyspnea, cough, fatigue, depression, and anxiety are predominant; 3) presence of symptoms prior to surgery is an important risk factor for higher acuity of symptoms and persistence after surgery; and 4) symptom burden is a predictor of postoperative QOL. Importantly, the findings verify the frameworks proposed to evaluate lung cancer patient HRQOL domain priorities from other works.77 This study also demonstrates the rapid increase in the last decade of studies examining symptom burden in patients undergoing lung cancer surgery.

These findings suggest several opportunities to develop programmatic strategies with targeted interventions to improve perioperative symptom burden. First, pain remains a major concern for patients for many months postoperatively, and pain is tied with longer length of stay and costs.78 While 50% of patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer believe that the surgery may alleviate cancer related symptoms, only 44% think the surgery may result in side effects or complications.75 Preoperative counseling about anticipated pain levels and durations should be routinely delivered in order to align expectations and improve outcomes.79–81 Next, Our findings support the pressing need for research to establish the clinical application of validated questionnaires (e.g., the lung cancer specific EORTC LC-2967,68 or shorter symptom inventories such as the MD Anderson Lung Cancer module82 particularly as surgical societies move toward routine patient-reported outcome reporting83 and clinical trialist seek to determine the impact of their therapies on HRQOL.14 The association of residual postoperative symptoms with permanent declines in QOL, the importance of symptom clustering, and the best to prognosticate and tailor interventions to preoperative symptoms is not clear and all are areas for future work.

The major limitation to this study, as with all qualitative reviews, relates to the biases introduced through selection of search terms and review of articles. We did use standard search terms and two reviewers for each stage of the review to mitigate bias but did face a challenge with the large number of found studies, requiring us to further group and categorize articles to improve our focus. There were no studies found on symptom burden with level of evidence quality 1 (randomized control trial or meta-analysis), which limits our ability to draw conclusions that would be generalizable. There was notable heterogeneity in the QOL instruments used across the studies precluding our ability to perform a quantitative analysis. In addition, the majority of studies had a level of quality 4, resulting in a high level of bias in the studies. For this reason, only a qualitative analysis was able to be performed.

Conclusion

Symptom burden has been demonstrated to have an important impact on patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer, and my influence quality of life in this group. Pain, respiratory symptoms, mental health symptoms, and fatigue contribute to lung cancer surgery patients’ symptom burden. While the increased focus on QOL should lead toward a more patient-centered practice, challenges remain in implementation due to the inconsistent use of standard QOL instruments. More research is needed to apply symptom and QOL assessment after lung cancer surgery in a way that is clinically relevant for both patients and surgeons.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

The authors report no conflict of interest related to the content herein.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Abbreviations:

- EORTC QLQ-C30

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire - Core 30

- EORTC QLQ-LC13

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire - Lung Cancer 13

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- MOS SF-36 (SF-36)

Medical Outcomes Study – Short Form 36

- NSCLC

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

- PROMIS

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

- QOL

Quality of Life

- VAS

Visual Analogue Scale

- VATS

Video-assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery

Footnotes

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.05.016.

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Cancer CollaborationFitzmaurice C, Allen C, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:524–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moller A, Sartipy U. Long-term health-related quality of life following surgery for lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poghosyan H, Sheldon LK, Leveille SG, Cooley ME. Health-related quality of life after surgical treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Lung Cancer 2013;81:11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang C-FJ, Sun Z, Speicher PJ, et al. Use and outcomes of minimally invasive lobectomy for Stage I non-small cell lung cancer in the national cancer data base. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:1037–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paul S, Altorki NK, Sheng S, et al. Thoracoscopic lobectomy is associated with lower morbidity than open lobectomy: a propensity-matched analysis from the STS database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;139:366–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boffa DJ, Dhamija A, Kosinski AS, et al. Fewer complications result from a video-assisted approach to anatomic resection of clinical stage I lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan TD, Black D, Bannon PG, McCaughan BC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials on safety and efficacy of video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2553–2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kent M, Wang T, Whyte R, et al. Open, video-assisted thoracic surgery, and robotic lobectomy: review of a national database. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:236–242. discussion 242–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleeland CS, Wang XS, Shi Q, et al. Automated symptom alerts reduce postoperative symptom severity after cancer surgery: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:994–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzsimmons D, Wheelwright S, Johnson CD. Quality of life in pulmonary surgery: choosing, using, and developing assessment tools. Thorac Surg Clin 2012;22:457–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pompili C, Koller M, Velikova G. Choosing the right survey: the lung cancer surgery. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:6892–6901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pompili C, Basch E, Velikova G, Mody GN. Electronic patient-reported outcomes after thoracic surgery: toward better remote management of perioperative symptoms. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:1878–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khullar OV, Rajaei MH, Force SD, et al. Pilot study to integrate patient reported outcomes after lung cancer operations into the society of thoracic surgeons database. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim E, Batchelor T, Shackcloth M, et al. Study protocol for VIdeo assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy versus conventional Open LobEcTomy for lung cancer, a UK multicentre randomised controlled trial with an internal pilot (the VIOLET study). BMJ Open British Med J Publishing Group 2019;9:e029507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tipton K, Leas BF, Mull NK, et al. Interventions To Decrease Hospital Length of Stay. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Technical Briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health-care Research and Quality (US); 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gazala S, Pelletier J-S, Storie D, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis to assess patient-reported outcomes after lung cancer surgery. Scientific World J 2013;2013:789625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pompili C. Quality of life after lung resection for lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2015;7:S138–S144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Grouperemy Howick, Chalmers Iain (James Lind Library), Glasziou Paul, Greenhalgh Trish, Heneghan Carl, Liberati Alessandro, Moschetti Ivan, Phillips Bob, Thornton Hazel, Goddard Olive and Hodgkinson Mary. “The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2,” OCEBM Levels of Evidence — Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), University of Oxford. Available at: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence. Accessed February 3, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterne JA, Hern an MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takenaka S, Saeki A, Sukenaga N, et al. Acute and chronic neuropathic pain profiles after video-assisted thoracic surgery: a prospective study. Medicine 2020;99:e19629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoon S, Hong W-P, Joo H, et al. Long-term incidence of chronic postsurgical pain after thoracic surgery for lung cancer: a 10-year single-center retrospective study. Regional Anesthesia Pain Med 2020;45:331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golder HJ, Papalois V. Enhanced recovery after surgery: history, key advancements and developments in transplant surgery. J Clin Med 2021;10:1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gjeilo KH, Oksholm T, Follestad T, et al. Trajectories of pain in patients undergoing lung cancer surgery: a longitudinal prospective study. J Pain Symptom Manag 2020;59:818–828.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wildgaard K, Ravn J, Nikolajsen L, et al. Consequences of persistent pain after lung cancer surgery: a nationwide questionnaire study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2011;55:60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balduyck B, Hendriks J, Lauwers P, Van Schil P. Quality of life evolution after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study in 100 patients. Lung Cancer 2007;56:423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guastella V, Mick G, Soriano C, et al. A prospective study of neuropathic pain induced by thoracotomy: Incidence, clinical description, and diagnosis. Pain 2011;152:74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinney MAO, Hooten WM, Cassivi SD, et al. Chronic postthoracotomy pain and health-related quality of life. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2012;93:1242–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grosen K, Laue Petersen G, Pfeiffer-Jensen M, et al. Persistent post-surgical pain following anterior thoracotomy for lung cancer: a cross-sectional study of prevalence, characteristics and interference with functioning. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;43:95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skrzypczak PJ, Roszak M, Kasprzyk M, et al. Pneumonectomy – permanent injury or still effective method of treatment? Early and long-term results and quality of life after pneumonectomy due to non-small cell lung cancer. Polish J Cardio-Thoracic Surg 2019;16:7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balduyck B, Hendriks J, Lauwers P, Van Schil P. Quality of life after lung cancer surgery: a prospective pilot study comparing bronchial sleeve lobectomy with pneumonectomy. J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:604–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gryglicka K, Białek K. The patient’s readiness to accept the changes in life after the radical lung cancer surgery. Współczesna Onkologia 2020;24:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mokhles S, Nuyttens J, de Mol M, et al. Treatment selection of early stage non-small cell lung cancer: the role of the patient in clinical decision making. BMC Cancer 2018;18:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golden SE, Thomas CR, Deffebach ME, et al. It wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be”: a qualitative study of early stage non-small cell lung cancer patients after treatment. BMC Res Notes 2017;10:642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malinowska K. The relationship between chest pain and level of perioperative anxiety in patients with lung cancer. Polish J Surgery 2018;90:23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ni J, Feng J, Denehy L, et al. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and associated risk factors in patients with lung cancer: a longitudinal observational study. Integrative Cance Ther 2018;17:1195–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, Che S, Zhang J, et al. Resilience process and its protective factors in long-term survivors after lung cancer surgery: a qualitative study. Supportive Care Cancer 2021;29:1455–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeantieu M, Gaillat F, Antonini F, et al. Postoperative pain and subsequent PTSD-related symptoms in patients undergoing lung resection for suspected cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:362–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarna L, Evangelista L, Tashkin D, et al. Impact of respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function on quality of life of long-term survivors of non-small cell lung cancer. Chest 2004;125:439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janet-Vendroux A, Loi M, Bobbio A, et al. Which is the role of pneumonectomy in the era of parenchymal-sparing procedures? early/long-term survival and functional results of a single-center experience. Lung 2015;193:965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pompili C, Brunelli A, Xiume F, et al. Prospective external convergence evaluation of two different quality-of-life instruments in lung resection patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011;40:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feinstein MB, Krebs P, Coups EJ, et al. Current dyspnea among long-term survivors of early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1221–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin RJ, Che GW. Risk factors of cough in non-small cell lung cancer patients after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:5368–5375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oksholm T, Rustoen T, Cooper B, et al. Trajectories of symptom occurrence and severity from before through five months after lung cancer surgery. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:995–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie M, Zhu Y, Zhou M, et al. Analysis of factors related to chronic cough after lung cancer surgery. Thoracic Cancer 2019;10:898–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bando T, Onishi C, Imai Y. Treatment-associated symptoms and coping of postoperative patients with lung cancer in Japan: development of a model of factors influencing hope: Developing a model influencing hope. Japan J Nursing Sci 2018;15:237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodman H. Meeting patients’ post-discharge needs after lung cancer surgery. Nurs Times 2000;96:35–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Dams R, Grogan T, Lee P, et al. Impact of health-related quality of life and prediagnosis risk of major depressive disorder on treatment choice for Stage I lung cancer. JCO Clin Cancer Informatics 2019;3:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodríguez-Quintana R, Hernando-Trancho F, Cruzado JA, et al. Assessment of quality of life, emotional state, and coping skills in patients with neoplastic pulmonary disease. Psicooncologia 2012;9:95–112. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarna L, Cooley ME, Brown JK, et al. Women with lung cancer: quality of life after thoracotomy: a 6-month prospective study. Cancer Nurs 2010;33:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Erol Y, Çakan A, Ergönül AG, et al. Psychiatric assessments in patients operated on due to lung cancer. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2017;25:518–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rolke HB, Bakke PS, Gallefoss F. HRQoL changes, mood disorders and satisfaction after treatment in an unselected population of patients with lung cancer. Clin Respir J 2010;4:168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Myrdal G, Valtysdottir S, Lambe M, Stahle E. Quality of life following lung cancer surgery. Thorax 2003;58:194–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walker MS, Zona DM, Fisher EB. Depressive symptoms after lung cancer surgery: their relation to coping style and social support. Psychooncology 2006;15:684–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park S, Kang CH, Hwang Y, et al. Risk factors for postoperative anxiety and depression after surgical treatment for lung cancerdagger. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:e16–e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oh S, Miyamoto H, Yamazaki A, et al. Prospective analysis of depression and psychological distress before and after surgical resection of lung cancer. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;55:119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Antoniu SA, Mititiuc I. Quality of life following lung cancer surgery: What about before? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2003;3:375–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang FF, Yang Q, Zhang J, et al. The structural equation model on self-efficacy during post-op rehabilitation among non-small cell lung cancer patients. PLoS One 2018;13:e0204213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin S, Chen Y, Yang L, Zhou J. Pain, fatigue, disturbed sleep and distress comprised a symptom cluster that related to quality of life and functional status of lung cancer surgery patients. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:1281–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Banik A, Luszczynska A, Pawlowska I, et al. Enabling, not cultivating: received social support and self-efficacy explain quality of life after lung cancer surgery. Ann Behav Med 2017;51:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hugoy T, Lerdal A, Rustoen T, Oksholm T. Predicting postoperative fatigue in surgically treated lung cancer patients in Norway: a longitudinal 5-month follow-up study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e028192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berman AT, DeCesaris CM, Simone CB 2nd, et al. Use of survivorship care plans and analysis of patient-reported outcomes in multinational patients with lung cancer. J Oncol Pract 2016;12:e527–e535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fagundes CP, Shi Q, Vaporciyan AA, et al. Symptom recovery after thoracic surgery: measuring patient-reported outcomes with the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;150. 613–9.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ida M, Onodera H, Yamauchi M, Kawaguchi M. Preoperative sleep disruption and postoperative functional disability in lung surgery patients: a prospective observational study. J Anesthesia 2019;33:501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang X, Zhou W, Zhang Y. Features of fatigue in patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Res Med Sci 2015;20:268–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Halle IH, Westgaard TK, Wahba A, et al. Trajectory of sleep disturbances in patients undergoing lung cancer surgery: a prospective study. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2017;25:285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koczywas M, Williams AC, Cristea M, et al. Longitudinal changes in function, symptom burden, and quality of life in patients with early-stage lung cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:1788–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen H-L, Liu K, You Q-S. Self-efficacy, cancer-related fatigue, and quality of life in patients with resected lung cancer. Euro J Cancer Care 2018;27:e12934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oksholm T, Miaskowski C, Solberg S, et al. Changes in symptom occurrence and severity before and after lung cancer surgery. Cancer Nurs 2015;38:351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shi Q, Wang XS, Vaporciyan AA, et al. Patient-reported symptom interference as a measure of postsurgery functional recovery in lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;52:822–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lowery AE, Krebs P, Coups EJ, et al. Impact of symptom burden in post-surgical non-small cell lung cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang P, Cheville AL, Wampfler JA, et al. Quality of life and symptom burden among long-term lung cancer survivors. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin YY, Wu YC, Rau KM, Lin CC. Effects of physical activity on the quality of life in taiwanese lung cancer patients receiving active treatment or off treatment. Cancer Nurs 2013;36:E35–E41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang KY, Chang NW, Wu TH, et al. Post-discharge health care needs of patients after lung cancer resection. J Clin Nurs 2010;19:2471–2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grigor EJM, Ivanovic J, Anstee C, et al. Impact of adverse events and length of stay on patient experience after lung cancer resection. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:382–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim Y, Winner M, Page A, et al. Patient perceptions regarding the likelihood of cure after surgical resection of lung and colorectal cancer. Cancer 2015;121:3564–3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shiyko MP, Siembor B, Greene PB, et al. Intra-individual study of mindfulness: ecological momentary perspective in post-surgical lung cancer patients. J Behav Med 2019;42: 102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brown LM, Gosdin MM, Cooke DT, et al. Health-related quality of life after lobectomy for lung cancer: conceptual frame-work and measurement. Ann Thoracic Surg 2020;110:1840–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huang L, Kehlet H, Petersen RH. Reasons for staying in hospital after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy. BJS Open 2022;6:zrac050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gehring MB, Lerret S, Johnson J, et al. Patient expectations for recovery after elective surgery: a common-sense model approach. J Behav Med 2020;43:185–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mancuso CA, Duculan R, Cammisa FP, et al. Concordance between patients’ and surgeons’ expectations of lumbar surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2021;46: 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oshima Lee E, Emanuel EJ. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med 2013;368: 6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xu W, Dai W, Gao Z, et al. Establishment of minimal clinically important improvement for patient-reported symptoms to define recovery after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 2022. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pompili C, Novoa N, Balduyck B. ESTS Quality of life and Patient Safety Working Group. Clinical evaluation of quality of life: a survey among members of European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2015;21:415–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.