Abstract

Background

Over the past decades, opioid prescriptions have increased in the Netherlands. The Dutch general practitioners’ guideline on pain was recently updated and now aims to reduce opioid prescriptions and high-risk opioid use for non-cancer pain. The guideline, however, lacks practical measures for implementation.

Objective

This study aims to determine practical components for a tool that should assist Dutch primary care prescribers and implements the recently updated guideline to reduce opioid prescriptions and high-risk use.

Methods

A modified Delphi approach was used. The practical components for the tool were identified based on systematic reviews, qualitative studies, and Dutch primary care guidelines. Suggested components were divided into Part A, containing components designed to reduce opioid initiation and stimulate short-term use, and Part B, containing components designed to reduce opioid use among patients on long-term opioid treatment. During three rounds, a multidisciplinary panel of 21 experts assessed the content, usability, and feasibility of these components by adding, deleting, and adapting components until consensus was reached on the outlines of an opioid reduction tool.

Results

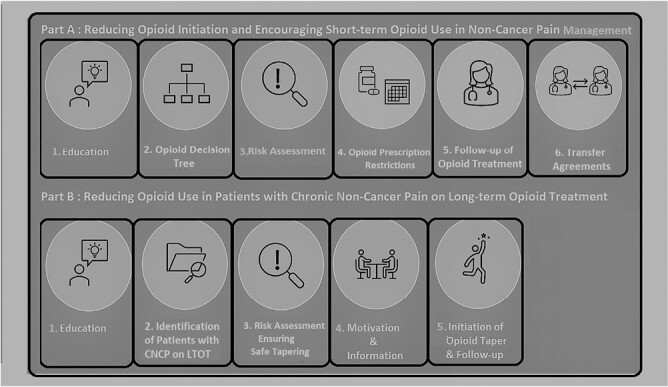

The resulting Part A consisted of six components, namely education, opioid decision tree, risk assessment, agreements on dosage and duration of use, guidance and follow-up, and interdisciplinary collaboration. The resulting Part B consisted of five components, namely education, patient identification, risk assessment, motivation, and tapering.

Conclusions

In this pragmatic Delphi study, components for an opioid reduction tool for Dutch primary care-givers are identified. These components need further development, and the final tool should be tested in an implementation study.

Keywords: analgesics, chronic pain, Delphi technique, deprescriptions, opioid, opioid-related disorders, primary health care

Key messages.

Increased opioid prescriptions for non-cancer pain in the Netherlands need to be addressed.

An opioid reduction tool could facilitate the implementation of primary care guidelines.

An expert team decided by consensus on opioid reduction measures for this tool.

Introduction

In 2020, the United States and Canada reported a record of fatal opioid overdoses.1 Without any intervention, an estimated 1.2 million fatal overdose deaths will occur in the United States between 2020 and 2029.2 Fatal opioid overdoses also occur, although to a lesser extent, in Europe.3 Similar to surrounding European countries, the Netherlands has experienced a rise in opioid prescriptions over the past decades.4 Most of these opioids are prescribed to treat non-cancer-related pain.5 In the Netherlands, the number of opioid-related deaths (0.1 to 0.5 per 100,000 inhabitants per year) and the number of patients treated for opioid use disorder (OUD) (1.5 to 7 per 100,000 inhabitants) have risen fivefold between 2008 and 2017.4 As of 2019, overall opioid numbers had started to decrease in the Netherlands, with approximately 30,000 people who use opioids less in 2019, and 32,000 people who use opioids less in 2020.6 Nevertheless the latest numbers for 2021 revealed an increase of approximately 34,000 patients treated with opioids.6

High-risk opioid use leads to substantial harm. Besides the well-known acute side effects such as respiratory depression, sedation, and constipation, various studies associate opioid use with an increased risk of myocardial infarction, falls, fractures, and all-cause mortality.7 Moreover, even when prescribed by medical doctors, opioids are addictive in nature and may lead to opioid dependence and OUD.8 These harms seem even more poignant considering the increased evidence of opioid’s minimal effectiveness in pain reduction and function improvement in non-cancer pain treatment.9 In reaction to the increase of opioid prescription numbers, the Dutch Ministry of Health initiated a task force called “Appropriate Opioid Use” which is led by the Institute of Responsible Drug Use (IVM), in February 2019.10 The aim of this taskforce was to decrease the overuse and unsafe use of opioids by patients while maintaining access to opioids in justified cases.10 Although opioid numbers were decreasing throughout the installation of this taskforce, the increase of opioid users in 2021 demonstrates that even more efforts are needed to decrease opioid prescription numbers and overall high-risk opioid use.

In Dutch primary care, opioids are prescribed by GPs and are dispensed by community pharmacists. Follow-ups for opioid treatment are typically conducted by GPs or, in, special cases, by community pharmacists and nurse practitioners. Hence, to further reduce opioid prescriptions and high-risk opioid use in primary care, the Tackling And Preventing The Opioid Epidemic, and the Minimal Intervention Strategy opioid reduction research team, initiated a collaborative Delphi study. The aim of this study was to identify practical components to include in a tool that could be used to assist Dutch primary care prescribers and dispensers to reduce opioid prescriptions and high-risk opioid use for acute and chronic non-cancer pain.

Methods

To ensure accurate reporting for this qualitative study the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research guideline was used11 (see Supplementary File 9).

Study design

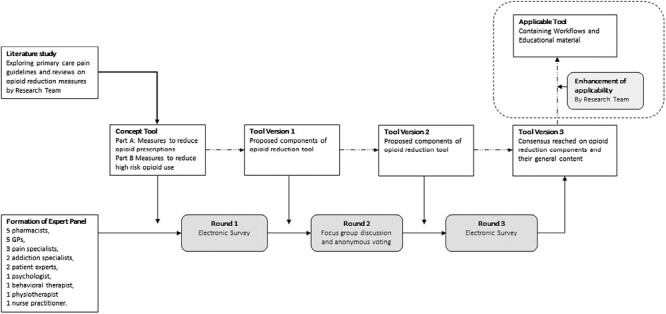

To identify opioid reduction measures for an opioid reduction tool for primary care that is applicable in the Dutch context, a modified Delphi approach with additional focus group discussions among experts was utilized. Beforehand, a concept tool that contained various components for an opioid reduction tool was constructed by the research team using a literature search on opioid reduction measures and close examinations of the Dutch GP guideline regarding the treatment of non-cancer pain. See Figure 1 for a visualization of the methods used in this modified pragmatic Delphi study.

Fig. 1.

Visualization of methods used in this pragmatic Delphi study.

Formation of concept tool based on previous studies

To determine the content of the concept tool, the members of the research team conducted various literature and qualitative studies before conducting this study. Two qualitative studies and a survey study were performed, including a survey among GPs and pharmacists that was used to determine the barriers and facilitators in opioid deprescribing, an interview study that was used to determine barriers and facilitators in opioid reduction among Dutch patients and a focus group study that was used to determine the attitude of GPs towards opioid deprescribing in the Netherlands (de Kleijn et. al., unpublished; Jansen – Groot Koerkamp et al., unpublished; Davies et al., unpublished). Through these studies primary care providers and patients addressed the need for practical tools and information that can facilitate reducing opioid prescriptions and decreasing high-risk opioid use.

The literature studies included a systematic review that was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of opioid reduction strategies, a systematic review that was conducted to determine the effectiveness of interventions in the treatment of withdrawal symptoms during opioid tapering and a qualitative review that explored GPs’ attitudes towards opioid use.12–14 No firm conclusions on effective opioid reduction measures that are useful in primary care could be drawn from these studies; the studies were generally small and underpowered, and they displayed a high risk of bias12 that is consistent with previous systematic reviews.15–17 However, according to these literature studies, team-based or multidisciplinary (pain) programs that support appropriate opioid prescribing, clinician-focused strategies that change clinicians’ prescribing behaviours, and the use of patient support components such as pain management education to ease opioid tapering seem to be opioid reduction measures that are worth exploring in the concept opioid reduction tool (de Kleijn et al., unpublished).9,12,14,18–22

Additionally, to identify other opioid reduction measures for the concept tool, guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic non-cancer pain from the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada were used.9,18–22 Based on these guidelines and studies performed by the research team, a concept tool consisting of multiple opioid reduction measures was developed. To ensure that this concept tool would address local needs and demands, the Dutch GP pain guideline was studied in-depth, and some components in the concept tool were corrected, added, or removed to ensure that the concept tool would align with the implementation of this guideline.23

The consensus on the outlines of the concept tool was reached through discussion of all of the above studies and information among the research team of this Delphi study consisting of three GPs, three pharmacists, two senior health scientists, one GP trainee, and one pharmacist in training who was distinguished in pain treatment. The final concept tool that was agreed upon consisted of a bundle of various opioid reduction measures (see the second column of Table 1 and Supplementary File 1). The concept tool was divided into two parts for practical reasons; Part A aims to reduce opioid initiation and to stimulate short-term use and Part B aims to reduce opioid use in patients who are on long-term opioid treatment (LTOT). Each part contains a number of main components that have been subdivided into subcomponents: Part A contains six main components, and part B contains five main components (see Figure 2 for a schematic overview of these components).

Table 1.

Opioid reduction tool and its changes during the Delphi study.

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part A | Concept tool | Tool version 1 | Tool version 2 | Tool version 3 |

| Component 1.0 Education | Aim Increasing knowledge and skills to patients and primary care-givers about acute and chronic non-malignant pain, effective |

|||

| Subcomponent 1.1 | E-learning modules regarding effective treatments for non-malignant pain and appropriate use of opioids are available to increase knowledge and skills among primary care providers. Topics discussed in the e-learning modules will also be included in online documents and other (visual) supporting material. | E-learning modules regarding (alternative) effective treatments for non-malignant pain and appropriate use of opioids are available to increase knowledge and skills among primary care providers. Topics discussed in the e-learning modules will also be included in online documents and other (visual) supporting material. | No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 1.2 | To increase knowledge and skills among patients, patient brochures and e-modules on non-malignant pain and opioid use are made available. These also serve to support shared decision-making about effective treatments for non-malignant pain. | No change | To increase knowledge and skills among patients, patient brochures and e-modules on non-cancer pain and opioid use are made available. Attention is paid to low-literate people and non-native speakers. These materials also serve to support shared decision-making about effective treatments for non-cancer pain. | No change |

| Subcomponent 1.3 | To gain insight into opioid use, a pharmacotherapeutic consultation (FTO) or consultation between pharmacist and general practitioner takes place several times during the intervention. These preferably take place at the start of the intervention and at 2, 4, and 6 months after the start. During this consultation, the following will be discussed: the opioid prescription data that are provided by the pharmacist as feedback, including the number of first opioid prescriptions, the number of second opioid prescriptions, and number of patients with repeat prescriptions for both weak and strong opioids. There is also room to discuss practical problems encountered by primary care providers through discussing patient cases. | To educate general practitioners (GPs) and pharmacists a pharmacotherapeutic consultation (FTO) is held to provide feedback regarding local opioid prescription numbers. In at least two FTOs 15 min will be used to discuss opioid prescription numbers and to discuss practical problems encountered by primary care providers through discussing patient cases. In the absence of sufficient FTO moments a consultation between GP(s) and pharmacist(s) is sufficient. | No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 1.4 | If primary care providers have remaining questions an (e) consultation with a pain specialist during the intervention is possible. | No change | DELETED | |

| Subcomponent 1.5 | During the intervention there are (online) peer consultation meetings scheduled with other participating GPs and pharmacists (10 sessions are scheduled in 6 months, of which 3 are compulsory). These meetings aim to increase knowledge and skills through mutual discussion. | DELETED | ||

| Component 2.0 Opioids decision tree |

Aim To prevent opioid initiation when considered inappropriate under current guidelines. |

|||

| Subcomponent 2.1 | When a patient with (acute) non-malignant pain visits the GP, the GP takes the following steps in order to achieve an appropriate pain treatment: - Determines location, duration and intensity of pain - Determines the effect of pain on functionality and daily functioning - Determines the type of pain - Sets treatment goals together with the patient. - Evaluates whether the WHO pain ladder has been followed properly. - Evaluates whether advice of the Dutch College of General Practitioners guideline “Pain” is adequately followed. - Discusses the use of alternative pain treatment if necessary. |

In a patient with (acute) non-malignant pain, the GP follows the recommendations described by the GP guideline “pain”. In particular, attention is paid to determining realistic treatment goals and alternative pain treatments. | In a patient with (acute) non-cancer pain, the GP follows the recommendations described by the GP guideline “pain” (update 2021 November 30). In particular, attention is paid to determining realistic treatment goals and alternative pain treatments. | No change. |

|

Component 3.0

Risk assessment |

Aim

To prevent opioid initiation in patients at high risk for an opioid use disorder |

|||

| Subcomponent 3.1 | If an opioid prescription is considered, the GP determines the risk of an opioid use disorder. Opioids should preferably not be prescribed in high-risk patients. The reason for this is discussed with the patient by the GP. Patients with high risk are those with: - an active psychiatric condition (depression, psychosis, etc.) - a substance dependence or addiction (i.e. alcohol, nicotine, illegal drugs, prescription drugs, etc.) or having a history of substance abuse or dependence. |

If an opioid prescription is considered, the GP determines the risk of an opioid use disorder. For patients with problematic opioid use, extra efforts are done to search for alternative effective pain treatment; if these are not existing opioids can be prescribed with extra guidance from a GP or nurse practitioner to prevent LTOT.

Patients with high-risk to develop OUD are those with: - an active psychiatric condition (depression, psychosis, etc.) - a substance dependence or addiction (i.e. alcohol, nicotine, illegal drugs, prescription drugs, etc.) or having a history of substance abuse or dependence. |

When considering an opioid prescription, the GP estimates the risk to an opioid use disorder. Patients with problematic opioid use receive extra guidance by their GP and/or nurse practitioner to prevent long-term use if opioid use cannot be avoided due to insufficient alternatives.

Risk factors for problematic opioid use: - previous opioid dependence - past and current addiction to other substances - psychiatric comorbidity |

When considering an opioid prescription, the GP estimates the risk to an opioid use disorder. Patients with a high risk to an opioid use disorder receive extra guidance by their GP and/or nurse practitioner to prevent long-term use if opioid use cannot be avoided due to insufficient alternatives. Risk factors for problematic opioid use: - previous opioid dependence - past and current addiction to other substances - psychiatric comorbidity |

| Addition |

Addition Subcomponent 3.2

If a patient is currently being treated by a psychiatrist or addiction specialist, the GP is recommended to consult the psychiatrist or addiction specialist before prescribing an opioid treatment. |

No change | No change | |

|

Component 4.0

Selection, dose, and duration as starting opioids |

Aim

Avoid long-term use of opioids |

|||

| Subcomponent 4.1 | When a GP decides to prescribe opioids, the GP will discuss the dosage and duration of the opioid treatment, the treatment goal, the possible side effects, the effectiveness, the short- and long-term effects and risks, and, in particular, discusses the addictive nature of opioids. | No change | No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 4.2 | When deciding to prescribe opioids, the general practitioner will consider the use of opioids as needed (pro re nata). | DELETED | ||

| Subcomponent 4.3 | The first prescription contains opioids in the lowest effective dose for a maximum of 7 days. |

Subcomponent 4.2

The first prescription contains opioids in the lowest effective dose for a maximum of 7 days. |

No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 4.4 | A consultation with the GP is scheduled around the end of the prescription to evaluate the use of opioids if the symptoms persist. | DELETED | ||

| Subcomponent 4.5 | When dispensing the first opioid prescription, the pharmacist/technician asks for the indication, discusses patient expectations and concerns, correct intake of opioids, correct use of “as needed” medication, possible side effects, effects and risks in the short and long term and, in particular, will address the addictive nature of opioids. |

Subcomponent 4.3

When dispensing the first opioid prescription, the pharmacist/technician asks for the indication, discusses patient expectations and concerns, correct intake of opioids, correct use of “as needed” medication, possible side effects, effects, and risks in the short and long term and, in particular, will address the addictive nature of opioids (coordinated with the information provided by the general practitioner). |

No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 4.6 | A first dispense of an opioid prescription issued by a secondary health care provider by the community pharmacist is adjusted to a maximum of 7 days after which the GP is informed of the prescription alteration. Consecutively the GP will contact the secondary care specialist and will discuss who will call the patient for a consultation around the end of the prescription to evaluate the pain. |

Subcomponent 4.4

Recipes issued by secondary care are adjusted to a delivery term of 7 days after which the GP is informed of the prescription alteration. |

Subcomponent 4.4

Recipes issued by secondary care are adjusted to a delivery term of 14 days after which the GP is informed of the prescription alteration. |

Subcomponent 4.4

GPs and pharmacists are encouraged regionally to make interdisciplinary agreements about the duration of opioid prescriptions. In the absence of such an agreement, a first dispense of an opioid prescription issued by a secondary health care provider by the community pharmacist is adjusted to a maximum of 14 days after which the GP is informed of the prescription alteration. |

|

Component 5.0

Follow-up and end of opioid treatment |

Aim

Avoid long-term use of opioids |

|||

| Subcomponent 5.1 | In case of persistent pain, a consultation with the GP takes place at the end of the first prescription. In this consultation, opioid use is evaluated by discussing the effect on pain, functionality and treatment goals, presence of side effects, use of other forms of pain relief, and wishes of the patient with regard to further pain treatment. | No change | No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 5.2 | If a second prescription is chosen, the second prescription will contain opioids for a maximum of 7 days | No change | No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 5.3 | If a second prescription is issued a consultation with the GP is scheduled around the end of the prescription date if the pain persists. | DELETED | ||

| Subcomponent 5.4 | Repeat prescriptions are only possible after (telephone) consultation with the GP. Moreover, only the own GP can prescribe opioid prescription for non-malignant pain. |

Subcomponent 5.3

In the exceptional case that a third prescription is required this prescription will contain opioids for a maximum of 4 weeks (this also applies to current chronic users). A repeat prescription can only be issued by the patients’ own GP. Every 4 weeks a (telephone) consultation with the GP is required. In addition to the discussion of the aforementioned subjects, the GP will strongly advise to taper opioids when the disadvantages outweigh the benefits of the treatment. |

Subcomponent 5.3

In the exceptional case that a third prescription is required this prescription will contain opioids for a maximum of 4 weeks (this also applies to current chronic users). A repeat prescription can only be issued by the patients’ own GP. Every 4 weeks a (telephone) consultation with the GP is required. In high-risk patients, a consultation is required every 2 weeks with the GP. In addition to the discussion of the aforementioned subjects, the GP will strongly advise to taper opioids when the disadvantages outweigh the benefits of the treatment. |

Subcomponent 5.3

In the exceptional case that a third prescription is required this prescription will contain opioids for a maximum of 4 weeks (this also applies to current chronic users). A repeat prescription can only be issued by the patients’ own GP. Every 4 weeks a (telephone) consultation with the GP is required. In high-risk patients a third prescription contains opioids for a maximum of 2 weeks. In addition to the discussion of the aforementioned subjects, the GP will strongly advise to taper opioids when the disadvantages outweigh the benefits of the treatment. |

| Subcomponent 5.5 | When repeat prescriptions are started in secondary care, the GP contacts the secondary care specialist so that there is clarity about the duration of the opioid treatment. |

Subcomponent 5.4

Repeat prescriptions issued by secondary health care providers without any clarity regarding who is responsible of follow-up treatment are denied and patients will be referred back to their secondary health care provider. |

No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 5.6 | For repeat prescriptions, a consultation with the GP is mandatory every 4 weeks. In addition to discussing the aforementioned topics, the GP will advise to reduce or discontinue opioids if the disadvantages outweigh the benefits of the treatment. | DELETED | ||

| Subcomponent 5.7 | The pharmacist does not dispense opioids in an automatic repeat service. |

Subcomponent 5.5

The pharmacist does not dispense opioids in an automatic repeat service. |

No change | No change |

| Addition |

Subcomponent 5.6

Discontinuation of treatment: if opioids have been used for less than 1 month, the dose can be halved every 2 days until discontinuation. If opioids have been used for more than 1 month, an opioid reduction schedule must be developed to taper opioids (see tool B and the guideline on opioid tapering). |

No change | ||

|

Component 6.0

Transfer |

Aim

Avoid inappropriate and long-term use of opioids |

|||

| Subcomponent 6.1 | Opioids for the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain are only prescribed by caring GPs and not by short-term locum GPs. | No change | No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 6.2 | Opioids are only dispensed by patient’s own pharmacy. In emergencies and during holidays an exception is made; opioids may be dispensed by another pharmacy, however, no more than is necessary to bridge the gap until opening of the patient’s own pharmacy. | No change | Opioids are only dispensed by patient’s regular pharmacy. | No change |

| Part B | ||||

|

Component 1.0

Education |

Aim

Increasing the knowledge and skills of patients and healthcare providers with regard to effective treatment of chronic non-malignant pain, effects of LTOT (long-term opioid therapy), motivational interviewing, opioid tapering and discontinuation of opioids, and treatment of possible withdrawal symptoms. |

|||

| Subcomponent 1.1 | E-learning modules regarding modules on effective treatments for chronic non-cancer pain, the effects of LTOT, motivational interviewing, controlled tapering and discontinuation of opioids (including tapering strategy) and treatment of any withdrawal symptoms that may occur are available to increase knowledge and skills among primary care providers. Topics discussed in the e-learning modules will also be included in online reference work and other (visual) supporting material. | E-learning modules regarding effective (alternative) treatments for chronic non-cancer pain, the effects of LTOT, motivational interviewing, controlled tapering and discontinuation of opioids (including tapering strategy) and treatment of withdrawal symptoms are available to increase knowledge and skills among primary care providers. Topics discussed in the e-learning modules will also be included in online reference work and other (visual) supporting materials. | No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 1.2 | To increase knowledge and skills among patients, patient brochures and e-modules on effective treatments of chronic non-malignant pain and the withdrawal of opioids are made available to patients. These also serve to support shared decision-making about effective treatments for non-malignant pain suitable for patients. | No change | No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 1.3 | At the start of the study, a pharmacotherapeutic consultation (FTO) is held to explain the study and provide feedback regarding local opioid prescription numbers. In the 6 months in which the intervention is applied, in at least two FTOs 15 min will be used to discuss opioid prescription numbers and to discuss practical problems encountered by primary care providers through discussing patient cases. In the absence of sufficient FTO moments a consultation between GP(s) and pharmacist(s) is sufficient. | No change | No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 1.4 | If primary care providers have remaining questions an (e) consultation with a pain specialist during the intervention (e.g. via Silo) is possible. | No change | DELETED | |

| Subcomponent 1.5 | During the intervention there are (online) peer consultation meetings are scheduled with other participating GPs and pharmacists (10 sessions are scheduled in 6 months, of which 3 are compulsory). These meetings aim to increase knowledge and skills through mutual discussion. | DELETED | ||

| Component 2.0 Identification of patients with LTOT for non-malignant pain |

Aim

Identification of patients with LTOT for chronic non-malignant pain to promote targeted discontinuation of inappropriate opioid use. |

|||

| Subcomponent 2.1 | The GP and the pharmacist map out which patients use long-term opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. The pharmacist identifies all patients with LTOT. The GP identifies which of these patients use opioids for chronic non-cancer pain that should be encouraged to taper opioid treatment. | No change | No change | No change |

|

Component 3.0

Risk assessment |

Aim

Identification of patients with LTOT who can be safely tapered in primary care. |

|||

| Subcomponent 3.1 | The GP then maps out which patients with LTOT for non-malignant pain can safely taper off in primary care. The GP will do this via the following steps: - Determine recent opioid doses and duration of treatment - Determine whether the patient has an active psychiatric condition (depression, psychosis, etc.) - Determine whether the patient has been actively diagnosed with a disorder in the use of alcohol or other (illegal) substances (nicotine abuse excluded). - Based on the above information, divide the patients into two groups: (i) Patients on opioids taking less than 120 mg morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) without active psychiatric illness and without a current substance use disorder or medical history. (ii) Patients on opioid use with 120 mg morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) or more or patients with active psychiatric illness or substance use disorder at present or in his/her medical history. The GP arrives at two groups in which the following applies: For group 1 it applies that they can reduce opioids safely under the supervision of the GP. For group 2, they are advised to phase out with the help of an addiction clinic or pain centre. If the patient agrees to this, the specialist becomes the primary practitioner and the patient is no longer supervised by the general practitioner. |

The GP identifies which patients can be tapered safely by GP and pharmacist. The GP will make a decision based on former opioid dependence, former unsuccessfully taper attempts, addiction to other substances, psychiatric comorbidity, and wish of the patient.

If patients are referred to the secondary or tertiary care, they will no longer be supervised by the GP. |

The GP identifies which patients can be tapered safely by GP and pharmacist, based on his competence. The GP will make a decision based on former opioid dependence, former unsuccessfully taper attempts, addiction to other substances, psychiatric comorbidity, and the wish of the patient. If patients are referred to the secondary or tertiary care, they will no longer be supervised by the GP. |

No change |

| Component 4.0 Motivation and information when considering opioid withdrawal |

Aim

Encouraging opioid withdrawal and withdrawal among patients with LTOT for chronic non-malignant pain. |

|||

| Subcomponent 4.1 | The GP invites patients who qualify for opioid tapering in primary care for a consultation to discuss their long-term opioid use. This invitation preferably takes place by telephone, but the GP can proceed to send a letter if the number of LTOT users in the practice is more than 10 patients. | The GP invites identified patients with LTOT that can safely taper off in primary care by means of a letter to discuss their opioid treatment. This letter announces that a consultation with the GP or nurse practitioner will follow. In this consult, the GP or nurse practitioner (if found competent) invites the patient to discuss opioid use in a consultation. | The GP invites identified patients with LTOT that can safely taper off in primary care by means of a letter to discuss their opioid treatment. This letter announces that a telephone consultation with the GP or nurse practitioner will follow. In this phone call, the GP or nurse practitioner (if found competent) invites the patient to discuss opioid use in a consultation. | The GP invites identified patients with LTOT that can safely taper off in primary care by means of a letter to discuss their opioid treatment. This letter announces that a telephone consultation with the GP or nurse practitioner will follow. In this phone call, the GP or nurse practitioner (if found competent) invites the patient to discuss opioid use in a consultation. |

| Subcomponent 4.2 | The GP receives patients with long-term opioid use for an initial consultation in which the GP discusses the following topics through motivational interviewing (carefully described in a consultation manual): - Dangers of LTOT - Addictive nature of opioids - Possible increase in pain due to LTOT (hyperalgesia) - Inappropriateness of LTOT for chronic non-malignant pain -Alternative and effective therapies for chronic non-malignant pain (physiotherapy, mindfulness, cognitive behavioural therapy, etc.). The GP also discusses the local options for alternative treatments. - Safely phase out LTOT in primary care. |

In the following consultation, opioid use is discussed by the GP (or, after mutual consultation, pharmacist) using motivational interviewing. In this talk, the following topics are discussed (carefully described in a conversation guide):

- Inappropriateness of LTOT for chronic non-cancer pain - Advantages and disadvantages of LTOT - Possible increase in pain due to LTOT (hyperalgesia) - Addictive nature of opioids - Unlikeliness to increase pain during opioid withdrawal - Opioid tapering being safe in primary care. - Alternative and effective therapies for chronic non-cancer pain (physiotherapy, mindfulness, cognitive behavioural therapy, etc.). The GP also discusses the local possibilities in terms of alternative pain treatments. |

In the following consultation, opioid use is discussed by the GP (or, after mutual consultation, pharmacist) using motivational interviewing. In this talk, the following topics are discussed (carefully described in a conversation guide): - Inappropriateness of LTOT for chronic non-cancer pain - Advantages and disadvantages of LTOT - Possible increase in pain due to LTOT (hyperalgesia) - Addictive nature of opioids - Unlikeliness to increase pain during opioid withdrawal - Opioid tapering being safe in primary care. - Alternative and effective therapies for chronic non-cancer pain (physiotherapy, acceptance-oriented interventions (ACT), cognitive behavioural therapy, etc.). The GP also discusses the local possibilities in terms of alternative pain treatments. |

In the following consultation, opioid use is discussed by the GP (or, after mutual consultation, pharmacist) using motivational interviewing. In this talk, the following topics are discussed (carefully described in a conversation guide): - Inappropriateness of LTOT for chronic non-cancer pain - Advantages and disadvantages of LTOT - Possible increase in pain due to LTOT (hyperalgesia) - Addictive nature of opioids - Unlikeliness to increase pain during opioid withdrawal - Opioid tapering being safe in primary care. - Alternative and effective therapies for chronic non-cancer pain (physiotherapy, acceptance-oriented interventions (ACT), cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), etc.). The GP also discusses the local possibilities in terms of alternative pain treatments. |

| Component 5.0 Initiation of opioid withdrawal and further guidance during this procedure |

Aim

Encouraging and guiding opioid withdrawal and withdrawal in patients with LTOT for chronic non-malignant pain |

|||

| Subcomponent 5.1 | In a second consultation after having decided to taper off opioids, the GP, pharmacist, and patient jointly develop a customized opioid taper schedule using the guideline for tapering opioids. The patient determines the pace of opioid tapering as well as the use of alternative pain treatment. | No change | No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 5.2 | During tapering, follow-up consultations take place with the GP with an interval of 1 week in the first 8 weeks followed by a consult every 2 weeks during the remaining of the tapering period. During the consultation, the following items are discussed: current opioid use (dose, frequency), presence or absence of withdrawal symptoms or other side effects (by using the Objective and Subjective Opioid Withdrawal Scale, OOWS, and SOWS), use of alternative pain treatments and their effect on pain, general pain intensity, functionality and quality of life. And where necessary, the GP prescribes drugs to treat opioid withdrawal symptoms in consultation with the patient, pharmacist, and/or addiction specialist. |

No change | No change | Periodic follow-up consultations with the GP (or, if desired, with the pharmacist) will take place during opioid tapering starting with an interval of once every one or two weeks followed by at least one consultation prior to any reduction. During this consultation, the following subjects are discussed: current opioid use (dosage, frequency), presence or absence of withdrawal symptoms or other side effects, use of alternative pain treatments and their effect on pain, general pain intensity, pain scores, functionality, and quality of life. If necessary, a GP can prescribe drugs for the treatment of opioid withdrawal symptoms after consulting a pharmacist and/or addiction specialist/psychiatrist. |

| Subcomponent 5.3 | During tapering, consultations with a nurse practitioner are held at an interval of once every 2 weeks. The nurse practitioner will explore alternative pain treatments using protocolled alternative interventions such as mindfulness | During opioid tapering, at the request of the patient and/or GP, consultations with the nurse practitioner can be held at an interval of once every 2 weeks. The nurse practitioner will explore alternative pain treatments using protocolled alternative interventions such as mindfulness. | During opioid tapering, at the request of the patient and/or GP, consultations with the nurse practitioner can be held at an interval of once every 2 weeks. The nurse practitioner will explore alternative pain treatments using protocolled alternative interventions such as acceptance and commitment therapy. | During opioid tapering, at the request of the patient and/or GP, consultations with the nurse practitioner can be held at an interval of once every 2 weeks. The nurse practitioner will explore alternative pain treatments using protocolled alternative interventions such as ACT. |

| Subcomponent 5.4 | During the reduction, a consultation with the pharmacist will take place on the patient’s request. | At the start of tapering, a consultation will take place with the community pharmacist. Depending on the patient’s wishes, follow-up consultations with the pharmacist (instead of the general practitioner) can be planned. | No change | No change |

| Subcomponent 5.5 | In general, GPs and nurse practitioners encourage physical activity by means of homework assignments, but where this is considered useful, a referral to a physiotherapist is made. | In general, GPs and nurse practitioners encourage physical activity by means of homework assignments. However, when considered helpful, a patient may be referred to a physiotherapist (preferably a psychosomatic physiotherapist). | In general, GPs and nurse practitioners encourage physical activity. However, when considered helpful, a patient may be referred to a physiotherapist (preferably a psychosomatic physiotherapist). | No change |

| Subcomponent 5.6 | There is a monthly discussion between the GP and the pharmacist about the prescription data of all patients who are tapering their opioids | DELETED | ||

|

Description: In three rounds 20 experts provided their insights and reached consensus on the Tool Version 3 of the Opioid Reduction Tool (ORT) presented in the last column of this table. All changes made by the expert panel are printed in bold. Footnotes: GP: general practitioner. FTO: pharmaceutical consultation between GPs and pharmacists. LTOT: long-term opioid use. ACT: acceptance-oriented interventions (ACT). CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy. | ||||

Original article - Qualitative Research.

Fig. 2.

Schematic overview of all opioid reduction components of the tool as agreed upon by the Expert Panel.

Delphi study

Since the literature studies and qualitative studies demonstrated that the evidence regarding effective opioid reduction measures for primary care is still lacking, it was decided that a Delphi study among an expert panel was needed to ensure that the opioid reduction tool would be in line with current medical practice and would be well-suited for use in primary care. The Delphi method is a regularly used consensus method in medical research, especially in situations in which evidence is lacking. A formal Delphi study is characterized by four main features, namely anonymity, iteration with controlled feedback, statistical group responses, and expert input.24 For this study, a modified Delphi method that incorporated focus group discussions was used. Some of the features that are typically used in formal Delphi studies were not or were partly implemented. According to formal Delphi techniques, the opioid reduction tool would have been developed by the expert panel members themselves.25 Nonetheless, in this modified Delphi study, the research team produced the first concept tool. The advantages of this modification included a higher initial round response rate, the implementation of a more evidence-based first agenda, and saving of time by reducing the number of rounds required to reach consensus26

Another Delphi feature, namely anonymity, was partly harmed in this Delphi study due to the integration of focus group discussions. Although anonymity is a highly valued feature of the Delphi technique, since it eliminates responses based on any form of peer pressure, it may also lead to a lack of accountability, which is expressed through reckless and ill-considered judgements that are made by experts.24 Accordingly, the Delphi technique is often viewed as a technique that should be used to initiate discussions rather than come to in-depth insights on specific topics.24 Focus group discussions, on the other hand, have proven to be particularly useful in generating consensus, as well as reflecting and exploring differences among a carefully selected research population.27 Moreover, these discussions provide participants with the possibility to clarify their points of view by gaining in-depth knowledge on the topic being discussed, which may additionally help to identify shared views depending on the group dynamics.28

The modified Delphi study consisted of three rounds. In the following sections, a detailed description of each round is provided. The minimal response rate per round was set at 70%, which is a response rate that is often used in formal Delphi studies.29,30 Notably, throughout the Delphi study, rigour and validity were ensured by using appropriate qualitative methods, including the practice of reflexivity, in which the research team explored how their collective experiences might alter the data collection and analysis.

Panel of experts

To ensure that the opioid reduction tool would address the needs and demands of Dutch primary care providers, the research team decided that the expert panel should consist mainly of clinicians who prescribe and dispense opioids for pain management namely, GPs and community pharmacists. Moreover, the research team decided to include at least one physiotherapist, one psychologist, one behavioural therapist, and one nurse practitioner to ensure that the proposed multidisciplinary opioid reduction measures would be suitable for Dutch primary care. Finally, since GPs had reported feeling ill-equipped in treating opioid dependence, the team decided that the expert panel was also in need of experts who worked in secondary care and had ample experience with this subject (de Kleijn et al., unpublished).In addition to the invited clinical experts, two patient experts with experience in opioid treatment and tapering were recruited to assess the usefulness of the opioid reduction tool from a patient perspective.

At the end of 2021, a diverse group of clinical experts who worked in primary care and secondary care were purposively identified based on their expertise. All of the experts were approached through personal networks; some of the experts who were contacted were listed as important contributors to clinical practice guidelines and academic research.4,31 The experts who agreed to participate were offered 200 euros as compensation for their time and effort. The final expert panel consisted of 21 experts: 5 community pharmacists, 5 GPs, 3 pain specialists, 2 addiction specialists, 2 patients, 1 psychologist, 1 behavioural therapist, 1 physiotherapist, and 1 nurse practitioner who is specialized in mental healthcare.

Round 1

In an online survey (see Supplementary File 2), the 21 panel experts were asked to respond to several questions regarding opioid reduction measures for which literature did not provide sufficient data and to judge the overall usefulness and feasibility of all of the proposed tool (sub)components of the first concept tool (see Supplementary File 1). Furthermore, the experts could suggest new components or request the removal of components and were asked to submit arguments that substantiated their opinions. The experts were asked to name the three most and the three least useful subcomponents of Parts A and B of the concept tool. A priori, and in line with previous modified Delphi studies, the research team decided that subcomponents that were identified as being the least useful by more than 50% of the experts would be eliminated from the tool.32–34 Moreover, any well substantiated or repeatedly suggested changes or additions to the tool were adopted, which resulted in Tool Version 1. Survey questions that caused substantial disagreement between the experts were highlighted and used to formulate discussion topics for Round 2.

Round 2

To reveal and deepen the collective insight into effective opioid reduction measures for primary care providers, the research team decided to include focus group discussions in Round 2 of this pragmatic modified Delphi study. All of the experts were purposively divided into three heterogeneous groups for a 1.5-h focus group discussion that was held online via MS Teams. One week prior to the discussion, all of the experts received Tool Version 1 and an accompanying document that contained an overview of all the revisions and discussion points that had emerged from the first round (see Supplementary File 5). The focus groups were recorded once oral consent from all participants was obtained. A group discussion was instigated by two moderators who used a focus group discussion guide (see Supplementary File 3).

To formalize the consensus on the adjusted tool, an anonymous vote was held at the end of the focus group discussion; all of the experts were asked to rate the acceptability and usefulness of each (sub) component of the tool on a 5-point Likert scale. If more than 30% of the experts rated a (sub) component with a score of 2 or less, this (sub) component was removed from the tool. After completing all of the group discussions, the recordings of the group discussions were transcribed into text. In a separate meeting, three members of the research group (EJ, LK, and RF) discussed the content of these group discussions to explore consensus within the group.

Round 3

Based on the results from the focus group discussion and the vote among the experts, the tool was revised for a second time. During the third round, Tool Version 2, an overview of all of the revisions, and a second survey was sent to all of the experts (see Supplementary File 3). All of the experts were given 14 days to respond to this online survey. All of the propositions that were provided through the second survey were discussed among the members of the research group. Propositions that were well substantiated or repeatedly suggested by multiple experts were adopted. Finally, based on input and consensus among all of the experts through three consecutive rounds, Tool Version 3 was established.

Results

Round 1

Twenty of the 21 participants completed the first questionnaire in November 2021. One general practitioner agreed to participate but did not respond to the questionnaires, and, therefore, was excluded from the study. Based on the questionnaire seven subcomponents were adjusted, four subcomponents were deleted, and one new subcomponent was added to Part A of the opioid reduction tool (see Supplementary File 5). Regarding Part B of this intervention, nine subcomponents were adjusted and two subcomponents were deleted (see Supplementary File 5). The changes made by the expert panel are printed in bold in the third column of Table 1.

Round 2

During the second round, three focus group discussions were held in December 2021. After the focus group discussion, the expert members anonymously rated the subcomponents using a 5-point Likert scale (see Supplementary File 6). Eighteen out of the 20 (90%) experts of Round 1 completed Round 2 entirely. All of the changes that were made by the expert panel based on Round 2 are printed in bold in the fourth column of Table 1.

Due to the focus group discussions, a couple of components were changed more radically. For example, most of the experts suggested developing extra care and information brochures for non-native speakers and illiterate patients (Subcomponent 1.2 of Parts A and B). Moreover, all of the experts agreed and preferred regional consultations instead of e-consultations (the deletion of Subcomponent 1.4 Parts A and B). In addition, although the GP pain guideline advocates a refill should be dispensed for only two weeks, which should be followed by a consult with a GP, the panel decided that a refill should be dispensed for four weeks to make the prescription restriction feasible (Subcomponent 5.3 Part A). Notably, they agreed that patients who are at high-risk for OUD should receive prescriptions and consultations with a GP every 2 weeks. Multiple GPs attending the focus group discussions suggested a stopping rule for short-term opioid use (Subcomponent 5.6 Part A). Subcomponent 3.1 of Part B (mapping which patient can safely taper in primary care) was adjusted to comply with general practitioner guidelines, which set the competence of a GP as a criterion for tapering off opioids as opposed to leaving this decision to patients alone. Furthermore, Subcomponent 4.1 of Part B (ways to contact patients) was adjusted because several expert members pointed out that ‘opioid tapering’ should not be used as the subject of patients’ letters but rather their ‘opioid use’, which conforms with lessons learned in behavioural change.

Throughout Round 2, it became apparent that various expert panel members were not fully aware of the role that community pharmacists can take in opioid reduction. During the last focus groups, the community pharmacists raised awareness regarding their roles in opioid reduction. As a result, Components 4.3 of Part A and Components 5.2 and 5.4 of Part B, which stimulate the use of community pharmacists, were ranked higher in the last two focus groups in comparison to the first focus groups.

Although the prescriptions from a secondary care specialist to maximum of seven days (Subcomponent 4.4 of Part A) were rated with a score of 2 or less by more than 30% of the experts, this subcomponent was not deleted but adjusted according to the consensus that was reached during the focus group discussions.

Notably, at the end of November 2021, the revised version of the GP guideline on pain management was officially published.31 After careful consideration and in agreement with all of the expert panel members, additional textual changes were made to align the opioid reduction tool with the revised GP pain guideline.

Round 3

During round 3, 18 participants completed the questionnaire in January 2022. One GP and one pharmacist did not fill in the questionnaire. During this round, the expert members suggested some textual changes, which are printed in bold in the last column of Table 1 (see Supplementary File 8 for an overview of these changes). In three rounds, 20 experts provided their insight and approved Tool Version 3, which is presented in the last column of Table 1. In Figure 2, a schematic overview is provided of all of the opioid reduction components of the tool that were agreed upon by the expert panel.

Discussion

Through this pragmatic Delphi study that included focus group discussions, a panel of experts provided their opinion on an opioid reduction tool. The tool, as decided on by the expert panel, contains two parts. Part A aims to reduce opioid initiation and stimulate short-term use, and part B aims to taper opioids in patients who are on LTOT. Part A consists of six opioid reduction components, namely education for patients and primary care providers, an opioid decision tree, a risk assessment, agreements on dosage and duration of use, guidance and follow-up, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Part B consists of five opioid reduction components: education for patients and primary care providers, patient identification, risk assessment, motivation, and tapering. Throughout the Delphi process, the expert panel emphasized the feasibility and usefulness of opioid reduction measures in the opioid reduction tool and changed the tool accordingly by aligning the tool with the current primary care guideline on pain, but the panel also altered some of the measures to suit busy primary care practices. Moreover, the expert panel members emphasized the need for educational materials that suit all types of patients, the close monitoring of patients who are at risk for opioid use disorder, collaboration with community pharmacists to relieve the busy GP practices, and collaboration with members of other disciplines such as psychosomatic physiotherapists, nurse practitioner specialized in mental health, and psychologists.

Over the past decades, opioid use has increased use of opioids in the treatment of non-cancer pain in the Netherlands.26 Most prescriptions are prescribed by GPs and dispensed by community pharmacists.5 Notably, in the Netherlands, GPs are often the prescribers of repeat opioid prescriptions that are used for treatment that is initiated in secondary care and transferred to primary care. To stimulate safe opioid prescribing in accordance with the recently adapted guideline it is essential to support, guide, and educate primary care providers.17,35 Where the Dutch GP pain guideline falls short on explicit and practical agreements and actions for opioid reduction, the components that were pointed out by the experts can simplify and facilitate the implementation of the guideline.31 Notably, as depicted in Figure 1, Tool Version 3 is not the final tool. The research team will translate Tool Version 3 to a format that is functional to use in daily practice, which will contain workflows and educational material that can be used to guide primary care providers to implement the opioid reduction measures that were identified by experts in Tool Version 3. The feasibility and acceptability of the final tool (Tool for Reducing Inappropriate Opioid use for Physician, Pharmacist and patient [TRIO-3P]) is planned to be explored in an implementation study that will be conducted among Dutch general practitioners (GPs) and pharmacists.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first consensus study that has been conducted to determine opioid reduction measures for a tool that will help primary caregivers implement guidelines regarding opioid prescription for non-cancer pain in the Netherlands. As was determined through the literature review, the evidence of effective opioid reduction strategies is still scarce. Meanwhile, guidelines, such as the Dutch GP pain guideline recommend opioid reduction for non-cancer pain. In practice, however, guidelines do not often reach their full potential and provide only facilitate moderate change in health care practice since their users find them too complex and often unclear.36 More specifically, recent qualitative research demonstrates that primary care-givers often feel ill-equipped to reduce opioid prescriptions in patients with non-cancer pain.14 Hence, the research team believes that the use of a consensus method is most suitable for developing an opioid reduction tool that contains opioid reduction measures that can improve the implementation of the current guideline.

Another strength of this study is that the research team, as well as the expert panel, consisted of a majority of primary care-givers, which ensured that the opioid reduction tool falls in line with the needs and demands of Dutch primary care-givers. Moreover, the research team was continuously aware of the impact that their experiences may have had on data collection and analysis. They ensured throughout the focus group discussions that the expert panel members were invited to criticize the feasibility and applicability of all proposed opioid reduction measures. The development of the final tool will be performed by the research team, who are predominantly working in primary care, which should ensure that the final workflows and educational materials are also tailored for implementation into Dutch primary care.

For pragmatic reasons, some of the formal Delphi methods were not implemented. By starting with a concept tool, the number of rounds that were required for this Delphi study to reach consensus was minimized. Moreover, the focus group discussions ensured the full participation of all of the experts and provided the experts with the opportunity to deeply discuss the implementation, applicability, and usefulness of opioid reduction measures. As demonstrated in the results section, the outcomes of the focus groups have had a considerable impact that the research team believes has strengthened the applicability of the proposed measures. Moreover, through discussion, the primary care providers educated each other on the capabilities of each provider regarding opioid reduction which further improved the tool. Specifically, the role of community pharmacists in opioid reduction was amplified since all of the experts agreed that GPs and pharmacists could complement each other and share responsibilities in reducing opioid prescriptions. In conclusion, using this hybrid and pragmatic method resulted in an effective synergy that is believed to have improved the overall outcome of the study.

In the midst of performing this study, the Dutch GP guideline on pain was officially updated and contained elaborate recommendations for reducing high-risk opioid use.31 This update was expected to increase awareness among Dutch GPs and other primary care providers, including community pharmacists, regarding harms that are related to opioid use and to reduce overall opioid prescription numbers for non-cancer pain in primary care.37 Most of these recommendations were implemented in the concept tool since the researchers were handed a concept version of this guideline just days before the Delphi study took place. However, since the guideline was officially published on 2021 November 30, some details did not align with the new guideline. The research team decided to edit some (sub)components after Round 2 to guarantee that the final tool would comply with the new guideline. With this in-between editing, the research team is aware that the anticipated consensus process was disrupted. Nonetheless, a majority of the expert panel members emphasized repeatedly that the tool would only be useful for clinical practice if it complied with the latest version of the guideline, which made this in-between editing permissible.

Finally, although the addition of two patient experts to the expert panel was of considerable value, one might question whether their views and opinions were properly addressed in this Delphi study. The presence of professionals and the academic language of the surveys and discussions might have been intimidating and reduced the participation of the patient experts. Future researchers who conduct a Delphi study that includes patients should address these language issues and the discussion group format to facilitate participation by patients and to ensure rich data collection.

Conclusion

In this pragmatic modified Delphi study, a panel of experts reached consensus on the components needed for a multidisciplinary opioid reduction tool for primary care providers. The components of this opioid reduction tool will need to be further developed into practical workflows, including educational material that may guide primary care providers in implementing existing guidelines and reducing opioid prescriptions and overall high-risk opioid use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wholeheartedly thank all experts that took part in this study for their criticism and insightful recommendations. Moreover, we thank Eman Badawy for her practical help in organizing this pragmatic modified Delphi study.

Contributor Information

Elsemiek A W Jansen-Groot Koerkamp, SIR Institute for Pharmacy Practice and Policy, Leiden, The Netherlands; Division of Pharmaco-epidemiology and Clinical Pharmacology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Loes de Kleijn, Department of General Practice, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Romina Fakhry, Division of Pharmaco-epidemiology and Clinical Pharmacology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Alessandro Chiarotto, Department of General Practice, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Mette Heringa, SIR Institute for Pharmacy Practice and Policy, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Hanneke J B M Rijkels-Otters, Department of General Practice, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Jeanet W Blom, Department Public Health and Primary Care, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Mattijs E Numans, Department Public Health and Primary Care, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Bart W Koes, Department of General Practice, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Research Unit of General Practice, Department of Public Health and the Center for Muscle and Joint Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

Marcel L Bouvy, Division of Pharmaco-epidemiology and Clinical Pharmacology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Author Contributions

All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. Authors EJ and LK contributed equally to this manuscript. Authors AC, MH, HR, JB, MN, BK, and MB contributed equally to this manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Based on the Dutch Medical Research Act (WMO), formal ethical approval for this study was unnecessary, as the participants of the study would not be subject to any action or behavioural change.

Funding

This work was supported by Dutch Research Council [grant number NWO.1160.18.300] and ZonMw [grant number 80-83911-98-1150]. No other funds were received. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of this study.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors report financial relationships that are relevant to this work. None of the authors report a conflict of interest. All the authors are listed and contributed substantially.

Data Availability

The majority of the data has been presented in the supplementary digital content. Transcripts of the focus group discussion cannot be shared due to privacy reasons. Other data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Humphreys K, Shover CL, Andrews CM, Bohnert ASB, Brandeau ML, Caulkins JP, Chen JH, Cuéllar M-F, Hurd YL, Juurlink DN, et al. Responding to the opioid crisis in North America and beyond: recommendations of the Stanford–Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2022;399(10324):555–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rao IJ, Humphreys K, Brandeau ML.. Effectiveness of policies for addressing the US opioid epidemic: a model-based analysis from the Stanford-lancet commission on the North American opioid crisis. The Lancet Regional Health-Americas. 2021;3(1):100031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. European drug report 2018: trends and developments. European Monitoring Centre for Drug and Drug Addiction, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2023. [accessed 2023 Feb 13].

- 4. Kalkman GA, Kramers C, van Dongen RT, van den Brink W, Schellekens A.. Trends in use and misuse of opioids in the Netherlands: a retrospective, multi-source database study. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(10):e498–e505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weesie Y, Dijk CEMJ, Flinterman LE, Hek K.. Voorschrijven van opioïden in de huisartsenpraktijk. NIVEL Utrecht; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. GIP Database. GIP data bank; 2022. [accessed 2022 Oct 28]. https://www.gipdatabank.nl/databank?infotype=g&label=00-totaal&tabel=B_01-basis&geg=gebr&item=N02

- 7. Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, Hansen RN, Sullivan SD, Blazina I, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Deyo RA.. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. Feb 17 2015;162(4):276–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Højsted J, Sjøgren P.. Addiction to opioids in chronic pain patients: a literature review. Eur J Pain. Jul 2007;11(5):490–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R.. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taakgroep gepast gebruik opioïde pijnstillers. Jaarverslag taakgroep gepast gebruik van opioïde pijnstillers 2019. Taakgroep gepast gebruik opioïde pijnstillers; 2022. [accessed 2022 Oct 28]. https://www.medicijngebruik.nl/filedispenser/2E098911-8C82-4544-B823-1213187A312C [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA.. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Kleijn L, Pedersen JR, Rijkels-Otters H, Chiarotto A, Koes B.. Opioid reduction for patients with chronic pain in primary care: systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(717):e293–e300. doi:10.3399/BJGP.2021.0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Langejan AI, de Kleijn L, Rijkels-Otters H, Chudy SFJ, Chiarotto A, Koes BW.. Effectiveness of non-opioid interventions to reduce opioid withdrawal symptoms in patients with chronic pain: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2022;39(2):295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Punwasi R, de Kleijn L, Rijkels-Otters JBM, Veen M, Chiarotto A, Koes B.. General practitioners’ attitudes towards opioids for non-cancer pain: a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e054945. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frank JW, Lovejoy TI, Becker WC, Morasco BJ, Koenig CJ, Hoffecker L, Dischinger HR, Dobscha SK, Krebs EE.. Patient outcomes in dose reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(3):181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mathieson S, Maher CG, Ferreira GE, Hamilton M, Jansen J, McLachlan AJ, Underwood M, Lin CC.. Deprescribing opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of randomised trials. Drugs. 2020;80(15):1563–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eccleston C, Fisher E, Thomas KH, Hearn L, Derry S, Stannard C, Knaggs R, Moore RA.. Interventions for the reduction of prescribed opioid use in chronic non-cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11(11):CD010323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Busse J, Guyatt G, Carrasco A, Akl E, Agoritsas T.. The 2017 Canadian guideline for opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Cancer Pain. 2017;105(39):15–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Häuser W, Morlion B, Vowles KE, Bannister K, Buchser E, Casale R, Chenot J-F, Chumbley G, Drewes AM, Dom G, et al. European* clinical practice recommendations on opioids for chronic noncancer pain - Part 1: role of opioids in the management of chronic noncancer pain. Eur J Pain. 2021;25(5):949–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. NG193. NICE Guideline. Chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain. Methods. 2021:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Centre OPM. Guidance for opioid reduction in primary care. Oxford. Guidance for opioid reduction in primary care (ouh.nhs.uk); 2022. [accessed 2022 Oct 28]. https://www.ouh.nhs.uk/services/referrals/pain/documents/gp-guidance-opioid-reduction.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid analgesics; 2023. [accessed 2023 Feb13]. https://nida.nih.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/opioid-crisis-pain-management/hhs-guide-clinicians-appropriate-dosage-reduction-or-discontinuation-long-term-opioid [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23. Pijn NHGW. NHG-standaard Pijn. Huisarts Wet. 2015;58(9):472–485. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goodman CM. The Delphi technique: a critique. J Adv Nurs. 1987;12(6):729–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jones J, Hunter D.. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ: Brit Med J. 1995;311(7001):376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tan K, Baxter G, Newell S, Smye S, Dear P, Brownlee K, Darling J.. Knowledge elicitation for validation of a neonatal ventilation expert system utilising modified Delphi and focus group techniques. Int J Hum-Comput Stud. 2010;68(6):344–354. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lakshman M, Charles M, Biswas M, Sinha L, Arora NK.. Focus group discussions in medical research. Indian J Pediatr. 2000;67(5):358–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Robinson N. The use of focus group methodology—with selected examples from sexual health research. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(4):905–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Turoff M, Linstone HA.. The Delphi method-techniques and applications. 2002.

- 30. Chiarotto A, Deyo RA, Terwee CB, Boers M, Buchbinder R, Corbin TP, Costa LOP, Foster NE, Grotle M, Koes BW, et al. Core outcome domains for clinical trials in non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(6):1127–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Damen Z K-KF, Keizer D, Luiten WE, Van den Donk M, Van ’t Klooster S, Van Walraven A, Veldhoven CMM, Vossenberg PCTJ.. NHG-standaard Pijn. Nederlands huisartsen genootschap 2021; 2022. [accessed 2022 Oct 28]. https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/pijn

- 32. Gray MP, Barreto EF, Schreier DJ, Kellum JA, Suh K, Kashani KB, Rule AD, Kane-Gill SL.. Consensus obtained for the nephrotoxic potential of 167 drugs in adult critically ill patients using a modified Delphi method. Drug Saf. 2022;45(4):389–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Valerino-Perea S, Armstrong MEG, Papadaki A.. Development of an index to assess adherence to the traditional Mexican diet using a modified Delphi method. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(14):4387–4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kohler JN, Turbitt E, Lewis KL, Wilfond BS, Jamal L, Peay HL, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB.. Defining personal utility in genomics: a Delphi study. Clin Genet. 2017;92(3):290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hamilton M, Mathieson S, Gnjidic D, Jansen J, Weir K, Shaheed CA, Blyth F, Lin C-WC.. Barriers, facilitators, and resources to opioid deprescribing in primary care: experiences of general practitioners in Australia. Pain. 2022;163(4):e518–e526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lugtenberg M, van Zegers-Schaick JM, Westert GP, de Vries PR, Evertse AJ, Burgers JS.. Welke barrières ervaren huisartsen bij de toepassing van aanbevelingen uit NHG-Standaarden? Huisarts en wetenschap. 2010;53(1):13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 37. van den Donk M, van Walraven A, Damen Z.. Meer aandacht voor chronische pijn en verantwoord gebruik van opioïden in NHG-Standaard Pijn. Huisarts en wetenschap. 2021;64(12):49–50. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The majority of the data has been presented in the supplementary digital content. Transcripts of the focus group discussion cannot be shared due to privacy reasons. Other data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.