Abstract

Background

Intrauterine adhesion (IUA) results from serious complications of intrauterine surgery or infection and mostly remains incurable. Small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have emerged as a potential new approach for the treatment of IUA; however, their impact is not fully understood. Here, we performed a meta-analysis summarizing the effects of sEVs on IUA in preclinical rodent models.

Methods

This meta-analysis included searches of PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, and the Web of Science databases from January 1, 1997, to April 1, 2022, to identify studies reporting the therapeutic effect of sEVs on rodent preclinical animal models of IUA. We compared improvements in endometrial thickness, endometrial gland number, fibrosis area, embryo number, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1), and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) levels after treatment.

Results

Our search included 100 citations, of which 7 met the inclusion criteria, representing 231 animals. Compared with that in the control group, the fibrosis area in the sEV-treated group was significantly reduced (standardized mean difference (SMD) = −6.87,95 % confidence interval (CI) = −9.67 to −4.07). The number of glands increased after the intervention (95 % CI, 3.72–7.68; P = 0.000). Endometrial thickness was significantly improved in the sEV-treated group (SMD = 2.57, 95 % CI, 1.62–3.52).

Conclusions

This meta-analysis is highlighting that sEV treatment can improve the area of endometrial fibrosis, as well as VEGF, and LIF level, in a mouse IUA model. This knowledge of these findings will provide new insights into future preclinical research.

Keywords: Intrauterine adhesion, Stem cell, Small extracellular vesicles, Meta-analysis, Animal models

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Intrauterine adhesions are complications of intrauterine surgery or infection.

-

•

Extracellular vesicles derived mesenchymal stem cells are a potential therapeutic agent.

-

•

Systemic review and meta-analysis showed that extracellular vesicles have anti-inflammatory effects.

-

•

Levels of LIF and VEGF were elevated after sEVs application.

-

•

SEVs therapy improved the overall outcome of intrauterine adhesions.

1. Introduction

Intrauterine adhesion (IUA), also called Asherman's syndrome, is mainly caused by mechanical injury and/or infection, resulting in the cervical canal/uterine cavity being partially or completely covered with fibrous tissue. Clinical manifestations include irregular menstruation, amenorrhea, secondary infertility, endometriosis, recurrent miscarriage, and abnormal placental development [1]. While pathogenesis of IUA is unclear, it is possible that the damaged endometrium is replaced by fibrous tissue, which, accompanied by insufficient uterine blood supply can result in the endometrium not being able to regenerate or function normally [2]. The current research on IUA involves many theories, and fibroblast proliferation and inflammatory response theories are the most widely studied [3].

The purpose of IUA treatment is to remove fibrous tissue, restore normal uterine morphology, reduce adhesion recurrence rate, restore endometrial function, and improve pregnancy rate. Hysteroscopic surgery is the classical treatment for IUA, combined with hormone therapy, intrauterine devices, Foley catheters, and other auxiliary methods. In recent years, with increasing numbers of follow-up studies, the use of hyaluronic acid, amniotic membrane transplantation, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), stem cells, and stents have all gained popularity [1]. However, these measures are not effective in preventing the recurrence of IUA. A meta-analysis showed that hyaluronic acid gel can effectively reduce the recurrence of IUA but did not show significant improvements in the postoperative pregnancy rate [4]. Additionally, Yang et al. suggested that postoperative estrogen therapy may improve menstrual patterns and did not appear to be associated with IUA recurrence [5]. However, more effective methods to restore endometrial regeneration and reduce IUA recurrence are needed. Therefore, the cellular and molecular pathogenesis of the disease needs to be better elucidated.

Stem cells are defined as undifferentiated or partially differentiated cells with the potential for self-renewal and multilineage differentiation, which makes them a promising treatment agent for damaged endometrial tissue [6,7]. Over the past decade, autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantation has been used to treat IUA in animals and human beings, and studies have shown that stem cell transplantation can promote endometrial regeneration, increase endometrial thickness, restore menstruation, and increase pregnancy rate, especially in refractory IUA [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]]. A meta-analysis indicated that autologous stem cell therapy was better than allogeneic stem cell treatment in terms of pregnancy rate and endometrial tissue recovery [14]. However, the clinical application of stem cells faces many challenges due to long-term preservation, immune rejection and replicative aging. In addition, growing evidence shows that the therapeutic effect of stem cells is mainly based on their paracrine effects, especially those related to small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) secreted by mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [2,7,15].

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are usually described as non-reproducible lipid bilayer particles and are released from cells into the microenvironment. The subtypes of EV are based on a) physical properties or density; b) biochemical components; or c) description of conditions or cell origin. According to the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV), the characterization of EVs should including the number of cultured cells, protein markers, and other techniques to evaluate single vesicle (such as: transmission electron microscopy, and nanoparticle analysis. SEVs, which are approximately 50–150 nm in size, can encapsulate biologically active substances, including proteins, lipids, DNA, mRNA, and non-coding RNA (ncRNA) [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. As reported, EVs release paracrine factors, such as chemokines, growth factors and cytokines, which have anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and pro-angiogenic effects during tissue repair [20], they can also overcome immune rejection and tumors. Therefore, sEVs have become a therapeutic option for IUA. Tan et al. found that miR-29a in bone marrow-derived MSC (BMSC)-sEVs played an anti-fibrotic role during endometrial repair of intrauterine adhesions both in vitro and in vivo [21]. Moreover, sEVs are involved in the process of endometrial repair, including inhibiting fibrotic tissue formation, promoting endometrial gland growth, regulating blood vessel formation, and improving endometrial compatibility. The strong evidence provided in these studies may form the foundation for future clinical studies.

To provide updated evidence for clinical research, we performed this meta-analysis to address the gap in the knowledge regarding the effectiveness of stem cell-derived sEVs in preclinical rodent models. We systematically reviewed relevant articles, including quantitative meta-analysis data, to evaluate the effects and underlying action mechanisms of stem cell-derived sEV treatment in animals with IUA. A meta-analysis of these preclinical data may contribute to future clinical studies.

2. Methods

The protocol for this systematic review is registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) website. Under the registration number is CRD42022335438. This meta-analysis based on the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA2020) guideline, as shown in Additional File 1.

2.1. Search strategy

Two authors (Wei-hong Chen and Shao-rong Chen) searched and collated independently in the PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane and Web of Science databases from relevant studies published between January 1, 1997, and April 1, 2022. The search strategies consisted of the following MeSH and free terms: gynatresia [MeSH terms], extracellular vesicles [MeSH terms], and sEVsome [MeSH Terms]. The search results for other free and MeSH terms are presented in Additional File 2.

2.2. Study selection criteria

Two independent investigators (Wei-hong Chen and Shao-rong Chen) conducted the literature selection. Bifurcations between these investigators were resolved by a third reviewer (Shu Lin).

2.3. Study selection criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) animal models, regardless of species and age, to explore the therapeutic effectiveness of extracellular vesicles for IUA; (2) stem cells-derived sEVs; (3) detailed descried about sEVs extraction and characterization; and (4) data for fibrotic areas.

Exclusion criteria: (1) sEVs derived from incompetent stem cells; (2) data could not be extracted; (3) the article was a review, letter, case report, short survey, conference abstract, or editorial; (4) titles and abstracts related to the topic, but full text is not available; and (5) written in a language other than English.

2.4. Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was based on the change in fibrotic area, whereas the secondary outcome measures included endometrial thickness, number of endometrial glands, number of embryos before and after treatment, and the levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1), and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF).

2.5. Data extraction

The data were extracted by Wei-hong Chen and Shao-rong Chen, and a third reviewer was included to answer and resolve any queries. The extracted information included: (a) first author, year of publication, and country of study; (b) number of animals, species, duration of treatment, follow-up time, and sEV cell origins; (c) endometrial receptivity: LIF, VEGF; and (d) endometrial fibrosis: TGF-β1.

2.6. Quality assessment

The quality of each included study was evaluated by two independent investigators using a Collaborative Approach to Meta-Analysis and Review of Animal Data from Experimental Studies (CAMARADES) based on a 10-item checklist: A, peer-reviewed journal; B, temperature controlled; C, randomly allocated animals; D, blind established model; E, blinded outcome assessment; F, use of anesthetic without significant intrinsic vascular protection activity; G, appropriate animal model (diabetic, advanced age, or hypertensive); H, calculation of sample size; I, statement of compliance with animal welfare regulations; and J, statement of potential conflicts of interest [22,23].

2.7. Bias risk assessment

The risk of bias was evaluated using the Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal Experimentation (SYRCLE) tool [24], which accounts for 10 types of bias, selection (sequence generation, baseline characteristics, allocation concealment); performance (random housing, blinding); detection (random outcome assessment, blinding, incomplete outcome data); reporting (selective outcome reporting); and other biases (other sources of bias).

2.8. Data analysis

All meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager Software version 5.4 and Stata MP Software version 14.0. The data not provided in the articles were obtained using Oringin Software 2021 [25]. All results were denoted as continuous variables and presented as standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95 % confidence intervals (CI).

Heterogeneity was estimated based on the I2 statistic and the P value. At I2< 50 %, the fixed effect model was used, whereas at I2>50%or P < 0.05, the mean heterogeneity was present and random-effected models were used [26]. We performed subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis, and further heterogeneity analysis. Funnel plots were drawn, and Egger's test was used to determine the fibrotic area to investigate publication bias.

3. Results

3.1. Study characteristics

A total of 155 articles were retrieved from the databases, of which seven met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The basic characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. In this meta-analysis, five articles were published in China, one in Egypt, and one in Turkey. In terms of species selection, four studies used Sprague-Dawley rats, two used albino rats, and the remaining one used New Zealand rabbits. All sEVs were derived from stem cells. The detailed characteristics of the sEVs in the included studies are shown in Table 2. Two studies used human umbilical cord MSC (hUCMSCs)-sEVs, two used animal BMSC-sEVs, one used animal autologous adipose-derived MSC (ADSCs)-sEVs, one used animal uterus-derived MSC (uMSCs)-sEVs, and one used menstrual blood-derived stromal cells (MenSCs)-sEVs. All studies described the methods of extraction and characterization of sEVs. The sEVs were characterized by different methods, including transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), and sEVs surface antigen detection was performed using western blotting. Five studies used ultracentrifugation, and two used the total sEVs isolation reagent. The diameter of the isolated sEVs ranged between 30 nm and 200 nm. Specific markers expressed in sEVs included: CD81, CD9, CD63, Alix, Hsp-70, and TSG-101. Six studies established IUA animal models by scraping the endometrium, and the remaining one induced IUA by injecting the uterus with 0.1 ml of trichloroacetic acid. The sEVs were administered in a variety of ways; six studies injected sEVs into the uterine horns or lumen, and one injected sEVs into the tail veins. All seven studies reported areas of fibrosis, and six studies reported gland numbers. The duration of sEVs treatment after IUA induction was <1 week (two studies), 1 week (two studies), or 2 weeks (three studies). Follow-up periods ranged from one to eight weeks.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of search results.

Table 1.

The basic characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Country | Animal Model(Age of Beginning of Study) | Injury Type | Number | Cell source of Evs | Therapy time | Measurement time | Dose | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebrahim 2018 |

Egypt | Female Albino rats (180–200 g,6 weeks old) | Injected 0.1 ml trichloroacetic acid | 7 VS 7 | hUCMSC | Two weeks | 8 weeks | 100 μg/kg | [12] |

| Xiao 2019 |

China | Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (200–220 g) | Scraped | 15 VS 15 | BMSC | 24 h | 2 weeks | 4 × 106 in 500 μl phosphate-buffered saline or PBS | [15] |

| Yao 2019 |

China | Female New Zealand white rabbits (2.5–3.5 kg, 12 weeks old) | Scraped | 16 VS 16 | BMSC | One week | 1 week, 2 weeks, 3 weeks, and 4 weeks | 0.25 ml | [16] |

| Saribas 2019 |

Turkey | Female wistar albino rats (8 weeks old) | Scraped | 6 VS 6 | uMSC | Two weeks | 8 weeks | 25 μg | [14] |

| Xin 2020 |

China | Female Sprague-Dawley rats (230–250 g, 8–9 weeks old) | Scraped | 40 VS 30 | UCMSC | Immediately | 30 and 60 days. | 100 μl | [18] |

| Zhao 2020 |

China | Female Sprague-Dawley rats (220–250 g, 8 weeks old) | Scraped | 12 VS 12 | ADSC | Two weeks | 4 weeks | 100 μg | [17] |

| Zhng 2021 |

China | Female Sprague-Dawley rats (200–220 g, 10 weeks old) | Scraped | 18 VS 18 | MenSC | One week | 4.5, 9 and 18 days | 2.125 × 107 particles [13] | |

Table 2.

The detail characteristics of the sEVs in the included studies.

| Study | Year | Number of cultured cells | Isolation methods | TEM morphology | NTA | WB | Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebrahim | 2018 | 90 % confluency of P3 hUMSCs | Ultracentrifugation | Spheroid double membrane-bound morphology with a diameter of 40–100 nm | |||

| Xiao | 2019 | 90 % confluency of P3–P4 BMSCs | Ultracentrifugation | Mean diameter was 182 nm | CD63 (+), CD9(+) | ||

| Yao | 2019 | 80 % confluency of P3 BMSCs | Total Exosome Isolation Reagent | Round or elliptical vesicles with intact capsule | A diameter of 40–160 nm. The peak particle size was 130 ± 11 nm | CD9 (+), HSP70(+) | 193.6 μg/ml by BCA assay |

| Saribas | 2019 | 2 × 106 P3 uMSC | Total Exosomes Isolation Reagent | Round with a diameter of 40–100 nm | 25 μg/0.1 ml by BCA assay | ||

| Xin | 2020 | 90–100 % confluency of P3 UC-MSCs(6.7 × 104/cm2) | Ultracentrifugation | Spherical with a diameter of approximately 100 nm | The main peak diameter of 136 nm | CD63 (+), TSG101 (+), GRP94 (−) |

|

| Zhao | 2020 | 90 % confluency of P3 ADSCs | Ultracentrifugation | Classic cup-shaped vesicles with on average size 30–200 nm | The mean of particle size was 109.5 nm | CD63 (+), Alix (+) | 1.1 E + 11 particles/ml by NTA |

| Zhang | 2021 | 80 % confluency of P3–P6 MenSCs | Ultracentrifugation | A typical cup- or sphere-shaped morphology | A peak diameter of 127 nm | CD63 (+), CD81 (+) | 1.7 × 109 particles per mL by NTA |

TEM, transmission electron microscopy; NTA, nanoparticle analysis; WB, western blot analysis; BCA, bicinchoninic protein assay; HSP, heat shock protein.

3.2. Quality assessment of included studies

All studies divided participants into at least control group and sEVs treatment group, but only one of the seven trials described randomization of the animals. None of the studies had potential conflicts of interest. None of the studies described the calculation of sample size, blinded induction of models, or blinded assessment of outcomes. Detailed information on the study quality assessment is presented in Additional File 3.

3.3. Risk of bias in studies

The SYRCLE results revealed that baseline characteristics in all studies were assigned as low risk, whereas allocation concealment, performance bias-blinding, and detection bias-blinding were assigned as high risk. The details are shown in Additional File 4.

3.4. Results of the meta-analyses

3.4.1. sEVs derived from stem cell therapy

3.4.1.1. Overall efficacy of sEV treatment

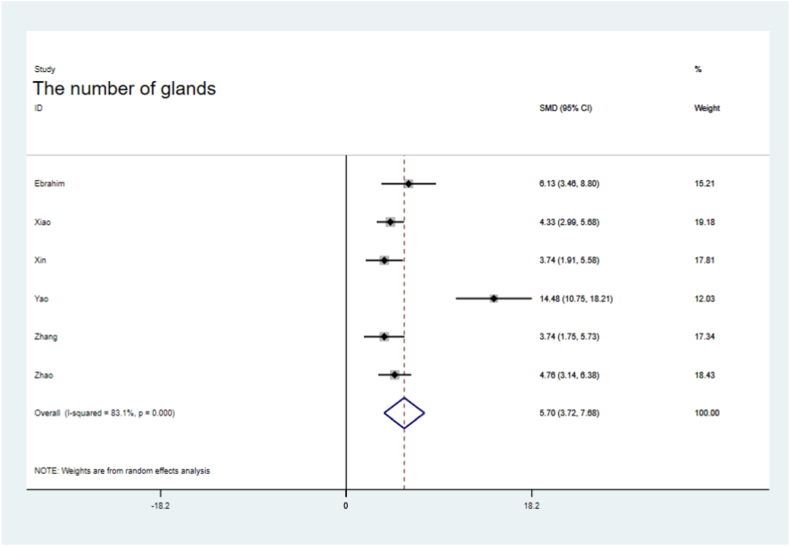

All studies reported significantly lower fibrotic areas in the sEV-treated groups than in the control groups (SMD = −6.87, 95 % CI, −9.67–4.07), but the analysis showed significant heterogeneity (P = 0.000; I2 = 92.4 %, Fig. 2). The difference in gland numbers at follow-up after sEV treatment was 5.70 % (95 % CI, 3.72–7.68; P = 0.000) with significant heterogeneity (I2=83.1 %) and inconsistency (P = 0.000; Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of fibrotic area.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the gland numbers between sEV therapy and controls.

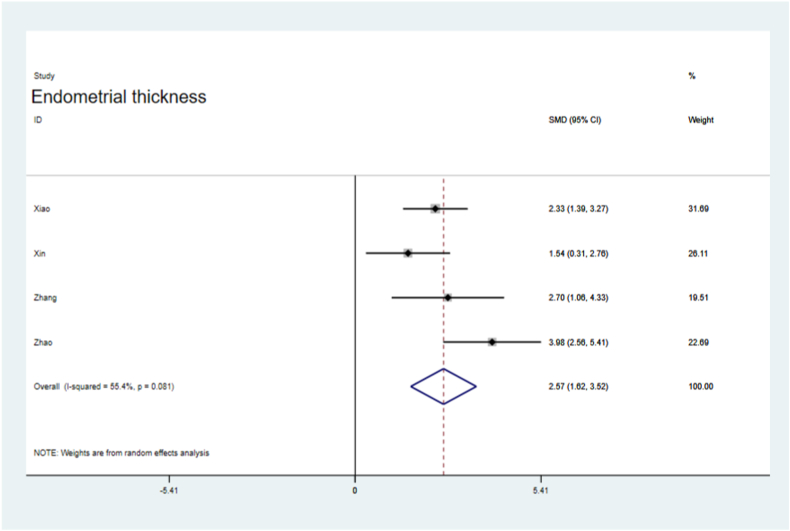

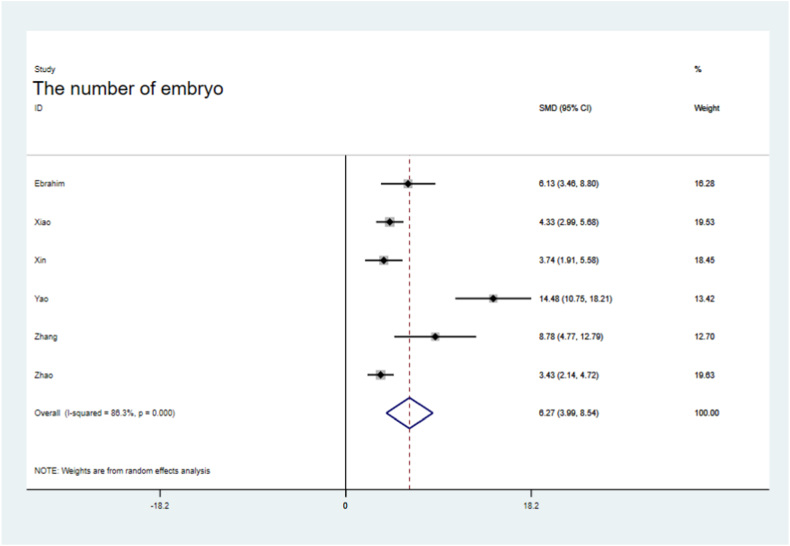

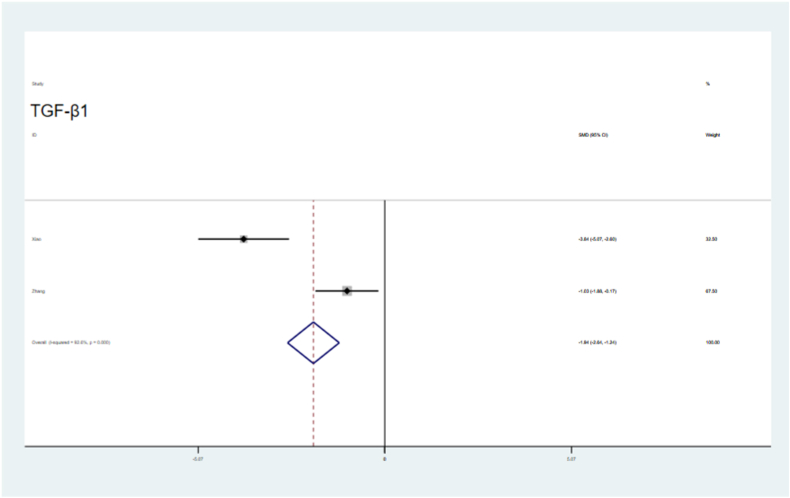

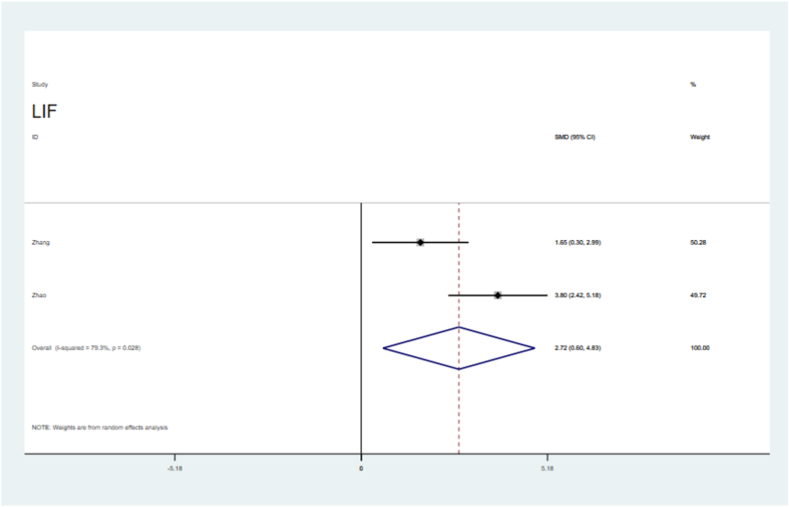

Endometrial thickness was significantly improved in the sEV-treated groups (SMD = 2.57, 95 % CI, 1.62–3.52), with significant the heterogeneity (P = 0.081,I2=55.4 %, Fig. 4). The number of embryos was significantly higher in the sEVs-treated groups than in the control groups (SMD = 6.27, 95 % CI, 3.99–8.54; P = 0.000), with heterogeneity (I2=86.3 %, Fig. 5). VEGF levels were significantly increased in the sEVs-treated groups (SMD = 3.34, 95 % CI, 2.32–4.36), with no obvious significant heterogeneity observed in the included tests (P = 0.589, I2=0.0 %,Fig. 6). TGF-β1 levels were significantly lower in the sEVs-treated groups than in the control group (95 % CI, −5.15 – 0.36; P = 0.000,Fig. 7). LIF levels were significantly increased in the sEVs-treated group (95 % CI, 0.60–4.83; P = 0.028, Fig. 8) compared to those in the control group.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the endometrial thickness.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of embryo number between sEVs therapy and controls.

Fig. 6.

Forest plot showing sEV therapy increased the level of VEGF, compared with controls.

Fig. 7.

Forest plot showing that sEV therapy reduced the level of TGF-β1 compared with controls.

Fig. 8.

Forest plot showing sEV therapy improved the level of LIF, compared with controls.

3.4.1.2. Sensitivity analyses

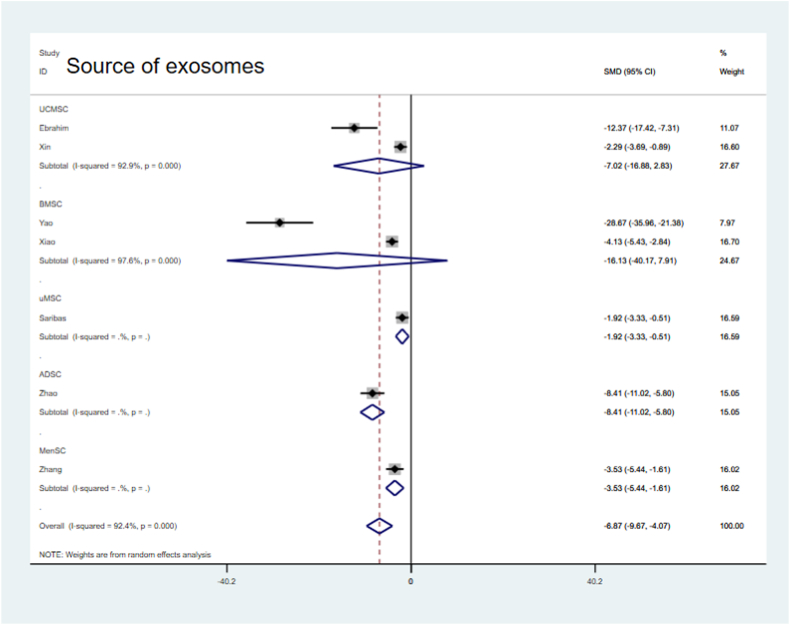

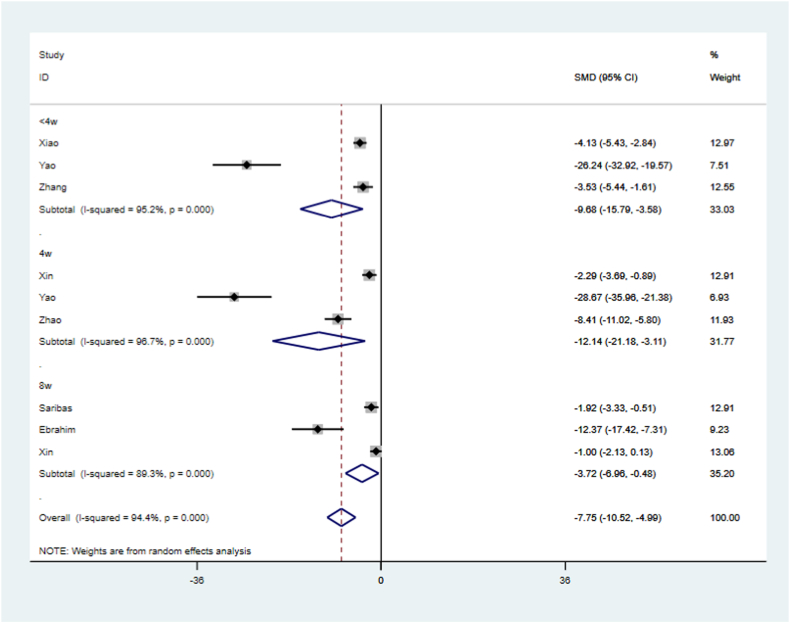

The heterogeneity of the fibrotic area data was high based on the above results. Therefore, we further analyzed the reasons for heterogeneity by conducting sensitivity and subgroup analyses. Sensitivity analysis showed that none of the individual studies had a significant effect on the outcome (Fig. 9). Subgroup analyses were then performed based on the following classifications: species (Fig. 10), sEV origin (Fig. 11), treatment time (Fig. 12), and follow-up time (Fig. 13), where no significant change in heterogeneity was observed. Treatment with sEVs derived from hUCMSCs significantly reduced the fibrotic area (SMD = −7.02, 95 % CI, −16.88 – 2.83; P = 0.000, Fig. 11). Compared with that in the control groups, treatment duration<1 week improved the fibrotic area (SMD = −3.23, 95 % CI, −5.04 to −1.43; P = 0.000, Fig. 12), with reduced heterogeneity (I2= 72.0 %). With a longer follow-up time (8 weeks), a greater improvement in the fibrotic area was observed in the sEV-treated group compared with that in the control group (SMD = −3.72, 95 % CI, −6.96 – 0.48, P = 0.000,Fig. 13).

Fig. 9.

Plot of sensitivity analysis. The plot showed that none of single study significantly influenced the results.

Fig. 10.

Subgroup analysis showing the effect of species.

Fig. 11.

Subgroup analysis showing the effect of sEV origin.

Fig. 12.

Subgroup analysis of treating time.

Fig. 13.

Subgroup analysis of follow-up time.

3.4.1.3. Publication bias

We observed significant publication bias in the funnel plot of the fibrotic regions (Fig. 14). We then used Egger's test to detect bias (P = 0.005), indicating the existence of publication bias (Fig. 15).

Fig. 14.

Publication-bias analysis results. The black spots were unevenly distributed on both sides of the funnel, indicating the existence of publication bias.

Fig. 15.

The outcome of Egger's test.

3.4.2. Comparison of stem cell types and their sEVs in preclinical treatments of IUA animals

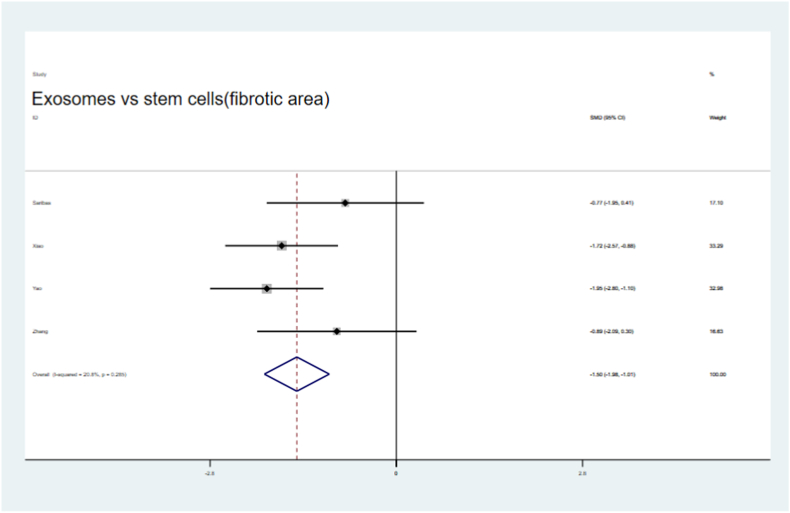

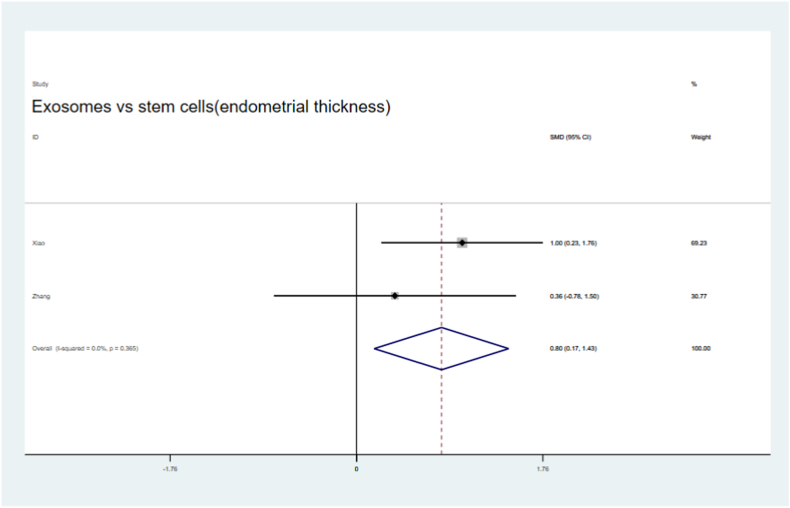

Four of the seven articles utilized stem cells and their sEVs in preclinical IUA animals. We found that the fibrotic areas in the sEV treatment groups were significantly reduced compared with those in the stem cells therapy groups (SMD = −1.50,95 % CI, −1.99 to −1.01), with low heterogeneity (I2 = 20.8 %, Fig. 16). Endometrial thickness was significantly improved both in the sEV and stem cell treatment groups (SMD = 0.80,95 % CI, 0.17–1.43, Fig. 17) compared to that in their respective control groups. Moreover, a non-significant but slight improvement in the number of glands and embryos in both groups was observed (Fig. 18, Fig. 19).

Fig. 16.

Compare of fibrotic area outcome in treatment with sEVs and stem cells.

Fig. 17.

Compare the improvement of endometrial thickness by sEVs therypy and stem cells therapy.

Fig. 18.

Compare the change of gland number by sEVs therapy and stem cells therapy.

Fig. 19.

Compare the change of embryo numbers by sEVs therapy and stem cells therapy.

4. Discussion

This meta-analysis investigated the efficacy of stem cell-derived sEVs in the treatment of IUA preclinical studies. Stem cell-derived sEV therapy significantly improves endometrial thickness, gland numbers, and VEGF levels reducing the fibrotic area in IUA. However, we found significant heterogeneity in the meta-analysis; therefore, we further explored different study designs, including species selection, sEV origin, treatment duration, and follow-up duration. Heterogeneity remained slightly high; nevertheless, these results highlight the potential clinical applicability of sEV therapy.

IUA is a common gynecological disease that develops from infection, trauma, or uterine cavity manipulation, which mainly occurs in women of reproductive age. The mechanism of IUA involves a decrease in the activity of endometrial stromal cells and the occurrence of apoptosis, which activates apoptosis signaling pathways, inhibits endometrial angiogenesis, and leads to endometrial atrophy [27]. Stem cells therapy has brought hope to regenerative medicine, especially for neurological diseases, lung dysfunction, reproductive diseases, skin burns and cardiovascular diseases. However, stem cells therapy faces many challenges, such as low engraftment rate, tumor formation, storage, and transportation, which limit its clinical application [[28], [29], [30]].

MSC-derived exosomes can be applied to establish a novel cell-free therapeutic approach for the treatment of a variety of diseases. Compared with stem cells, sEV have the advantage of low immunogenicity, low toxicity, low tumorigenicity and enhanced biocompatibility [31,32]. In recent years, sEV-mediated tissue repair has been studied in preclinical animal model. Human BMSC-derived exosomes inhibits the expression of α-SMA and type I collagen by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, inhibiting the inflammatory response, and promoting hepatocyte regeneration [33]. It has also been reported that the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway is closely related to endometrial fibrosis [34]. Yao et al. showed thatexosomes derived from BMSCs promoted endometrial gland formation, reduced fibrosis, and reversed the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process in a rat IUA model [35]. Liu et al. confirmed that the exosoems containing miR-223-3p derived from BMSCs suppress inflammation and promote angiogenesis and IUA recovery through the degradation of the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3(NLRP3) [36]. In this meta-analysis, we observed increased levels of LIF and VEGF, which are markers of endometrial receptivity [37]. The subgroup analysis of animal models, considering the sEV origin, treatment time, and follow-up time, demonstrated significant improvement in the fibrotic area (Fig. 11, Fig. 12, Fig. 13). The varying results of the subgroup analysis indicated that the efficacy of sEVs in treating IUA depends on different stimuli. The underlying mechanism may be related to the transport of active ingredients, particularly the upregulation or downregulation of microRNAs.

In clinical applications, researches have reported the diagnostic and therapeutic utility of sEVs in a variety of diseases. A novel urine exosome gene expression assay was used to predict high-grade prostate cancer in patients (NCT03031418) [38]. Jia et al. found that exosome-derived GAP43, neurogranulin, SNAP25, and synaptic marker protein 1 can be used to predict the occurrence of Alzheimer's diseases, five to seven years before cognitive impairment [39]. In a phase 1 clinical trial, Shi and colleagues investigated the role of nebulized human adipose-derived MSC-sEVs in decreasing lung inflammation and alleviating lung injury. All subjects tolerated nebulized MSC-sEVs without adverse reactions within seven days (NCT04313647) [40]. Xie et al. suggested that hUCMSC-sEVs carrying miR-320a may inhibit lung cancer cell growth via the SOX4/Wnt/β-catenin axis [41]. Another study found that the application of uc-msc-sev can significantly improve renal function in patients with grade III-IV chronic kidney disease, including plasma creatinine levels and glomerular filtration rate [42]. However, the current challenges in EV research encompass the method of EV separation, the impact of cell culture parameters, and the effects of different cell treatment approaches [43]. Another crucial issue is the storage of EVs, as studies have shown that storage conditions significantly affect particle loss, purity reduction, and artificial particles fusion in EVs [44]. In addition, the absence of a standardized therapeutic dosage [45] further restricts the clinical application of and use of MSC-sEVs.

Of course, this meta-analysis had certain limitations. First, the number of relevant articles on sEVs therapy in IUA animal models was insufficient. Second, the use of different sEVs sources, preparation techniques, modeling methods, administration methods, dosages, and sample sizes may led to sample bias, selection bias, and higher heterogeneity. Third, the selected articles did not clarify the calculation method for sample size. Fourth, the antibodies and immune rejection to allogeneic donor MSCs may not be immune-privileged [46]. However, in our study, we observed that the injection of MSCs derived sEVs improved IUA symptoms in animals. This may be because the studies we included did not document the complications and adverse effects of sEV therapy. Further investigative studies in the field can complement these results to provide a deeper understanding. In the simultaneous evaluation of IUA treatment with stem cells and sEVs, endometrial fibrosis and endometrial thickness were improved. The results of our analysis suggest that the existence of publication bias may have been caused by an insufficient number of study samples. Thus, more randomized controlled trials are needed to validate these findings.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this meta-analysis demonstrated that stem cell-derived sEV therapy improves the fibrotic area, number of glands, and endometrial thickness. Compared with stem cell therapy, sEV therapy has significant advantages in improving the fibrotic area and endometrial thickness in IUA. Although the results showed significant heterogeneity, the therapeutic effects of sEVs on IUA were observed and require further validation. In recent years, great progress has been made in obtaining high-quality sEVs due to ongoing research advancements. Moreover, the utilizatioin of sEVs derived from stem cells in preclinical studies and clinical trials has yielded encouraging results in disease diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment. However, there are many technical challenges in the separation and detection of extracellular vesicles. Therefore, the development of efficient and specific separation methods is urgently needed. In addition, the heterogeneity of EV, treatment dose, treatment concentration and treatment cycle are also problems that need to be solved. Therefore, more studies on the mechanism of EV are needed to focus on precision treatment, and it is hoped that it can be transformed into clinical trials of intrauterine adhesions.

Funding

Science and Technology Bureau of Quanzhou (2020CT003) and Science and Technology project of Fujian Provincial health commission (2020CXB027).

Availability of data and materials

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and the writing of the paper.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Wei-hong Chen: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Shao-rong Chen: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Xin-xin Hu: Data curation. Qiao-yi Huang: Data curation. Jia-ming Chen: Data curation. Shu Lin: Project administration, Supervision. Qi-yang Shi: Project administration, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to The Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University for providing infrastructure facilities. What's more, we would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Abbreviation

- ADSCs

Adipose mesenchymal stem cells

- BCA

Bicinchoninic protein assay

- BMSCs

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- CI

Confidence interval

- EV

Extracellular vesicle

- EXO

Exosome

- HSP

Heat shock protein

- hUCMSCs

Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells

- I2

Inconsistency index

- IUA

Intrauterine adhesion

- LIF

Leukemia inhibitory factor

- MenSCs

Menstrual blood-derived stromal cells

- MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells

- NTA

Nanoparticle analysis

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- PRP

Platelet-rich plasma

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- TGF-β1

Transforming growth factor β1

- uMSCs

Uterus mesenchymal stem cells

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- WB

Western blot analysis

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22902.

Contributor Information

Shu Lin, Email: shulin1956@126.com.

Qi-yang Shi, Email: wsqy214@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Ma J., et al. Recent trends in therapeutic strategies for repairing endometrial tissue in intrauterine adhesion. Biomater. Res. 2021;25(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s40824-021-00242-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song Y.T., et al. Stem cell-based therapy for ameliorating intrauterine adhesion and endometrium injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021;12(1):556. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02620-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao Y.X., et al. Repair abilities of mouse autologous adipose-derived stem cells and ShakeGel™3D complex local injection with intrauterine adhesion by BMP7-Smad5 signaling pathway activation. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021;12(1):191. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02258-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fei Z., et al. Meta-analysis on the use of hyaluronic acid gel to prevent recurrence of intrauterine adhesion after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019;58(6):731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang L., et al. The effect of estrogen in the prevention of adhesion reformation after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis: a prospective randomized control trial. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2022;20(7):871–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2022.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benor A., Gay S., DeCherney A. An update on stem cell therapy for Asherman syndrome. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020;37(7):1511–1529. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01801-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azizi R., et al. Stem cell therapy in Asherman syndrome and thin endometrium: stem cell- based therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;102:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L., et al. In situ repair abilities of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells and autocrosslinked hyaluronic acid gel complex in rhesus monkeys with intrauterine adhesion. Sci. Adv. 2020;6(21):eaba6357. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba6357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao Y., et al. Allogeneic cell therapy using umbilical cord MSCs on collagen scaffolds for patients with recurrent uterine adhesion: a phase I clinical trial. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018;9(1):192. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0904-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagori C.B., Panchal S.Y., Patel H. Endometrial regeneration using autologous adult stem cells followed by conception by in vitro fertilization in a patient of severe Asherman's syndrome. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2011;4(1):43–48. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.82360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma H., et al. Intrauterine transplantation of autologous menstrual blood stem cells increases endometrial thickness and pregnancy potential in patients with refractory intrauterine adhesion. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020;46(11):2347–2355. doi: 10.1111/jog.14449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh N., et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived stem cell therapy for Asherman's syndrome and endometrial atrophy: a 5-year follow-up study. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2020;13(1):31–37. doi: 10.4103/jhrs.JHRS_64_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan J., et al. Autologous menstrual blood-derived stromal cells transplantation for severe Asherman's syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2016;31(12):2723–2729. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J.M., et al. Clinical evaluation of autologous and allogeneic stem cell therapy for intrauterine adhesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.899666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xin L., et al. A scaffold laden with mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes for promoting endometrium regeneration and fertility restoration through macrophage immunomodulation. Acta Biomater. 2020;113:252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Witwer K.W., et al. Defining mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-derived small extracellular vesicles for therapeutic applications. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2019;8(1) doi: 10.1080/20013078.2019.1609206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Théry C., et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2018;7(1) doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y., et al. Exosome: a review of its classification, isolation techniques, storage, diagnostic and targeted therapy applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020;15:6917–6934. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S264498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen W.H., et al. Therapeutic potential of exosomes/miRNAs in polycystic ovary syndrome induced by the alteration of circadian rhythms. Front. Endocrinol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.918805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung R.K., Lin Y., Liu Y. Recent advances in understandings towards pathogenesis and treatment for intrauterine adhesion and disruptive insights from single-cell analysis. Reprod. Sci. 2021;28(7):1812–1826. doi: 10.1007/s43032-020-00343-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan Q., Xia D., Ying X. miR-29a in exosomes from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit fibrosis during endometrial repair of intrauterine adhesion. Int J Stem Cells. 2020;13(3):414–423. doi: 10.15283/ijsc20049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macleod M.R., et al. Pooling of animal experimental data reveals influence of study design and publication bias. Stroke. 2004;35(5):1203–1208. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000125719.25853.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C., et al. Extracellular vesicles for acute kidney injury in preclinical rodent models: a meta-analysis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020;11(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1530-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hooijmans C.R., et al. SYRCLE's risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014;14:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Y.L., et al. Stem cell-derived exosomes in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction in preclinical animal models: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022;13(1):151. doi: 10.1186/s13287-022-02833-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins J.P., et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cen J., et al. Research progress of stem cell therapy for endometrial injury. Mater Today Bio. 2022;16 doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poulos J. The limited application of stem cells in medicine: a review. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018;9(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0735-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu T.M. Application of mesenchymal stem cells derived from human pluripotent stem cells in regenerative medicine. World J. Stem Cell. 2021;13(12):1826–1844. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v13.i12.1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoang D.M., et al. Stem cell-based therapy for human diseases. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2022;7(1):272. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01134-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jia Y., et al. Small extracellular vesicles isolation and separation: current techniques, pending questions and clinical applications. Theranostics. 2022;12(15):6548–6575. doi: 10.7150/thno.74305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikfarjam S., et al. Mesenchymal stem cell derived-exosomes: a modern approach in translational medicine. J. Transl. Med. 2020;18(1):449. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02622-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rong X., et al. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes alleviate liver fibrosis through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019;10(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1204-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salma U., et al. vol. 2016. Mediators Inflamm; 2016. (Role of Transforming Growth Factor-Β1 and Smads Signaling Pathway in Intrauterine Adhesion). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao Y., et al. Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells reverse EMT via TGF-β1/Smad pathway and promote repair of damaged endometrium. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019;10(1):225. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1332-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y., et al. Bone mesenchymal stem cells-derived miR-223-3p-containing exosomes ameliorate lipopolysaccharide-induced acute uterine injury via interacting with endothelial progenitor cells. Bioengineered. 2021;12(2):10654–10665. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.2001185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Craciunas L., et al. Conventional and modern markers of endometrial receptivity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2019;25(2):202–223. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmy044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKiernan J., et al. A prospective adaptive utility trial to validate performance of a novel urine exosome gene expression assay to predict high-grade prostate cancer in patients with prostate-specific antigen 2-10ng/ml at initial biopsy. Eur. Urol. 2018;74(6):731–738. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jia L., et al. Blood neuro-exosomal synaptic proteins predict Alzheimer's disease at the asymptomatic stage. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(1):49–60. doi: 10.1002/alz.12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi M.M., et al. Preclinical efficacy and clinical safety of clinical-grade nebulized allogenic adipose mesenchymal stromal cells-derived extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2021;10(10) doi: 10.1002/jev2.12134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie H., Wang J. MicroRNA-320a-containing exosomes from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells curtail proliferation and metastasis in lung cancer by binding to SOX4. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2022;42(3):268–278. doi: 10.1080/10799893.2021.1918166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nassar W., et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells derived extracellular vesicles can safely ameliorate the progression of chronic kidney diseases. Biomater. Res. 2016;20:21. doi: 10.1186/s40824-016-0068-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ludwig N., Whiteside T.L., Reichert T.E. Challenges in exosome isolation and analysis in health and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(19) doi: 10.3390/ijms20194684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gelibter S., et al. The impact of storage on extracellular vesicles: a systematic study. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2022;11(2) doi: 10.1002/jev2.12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta D., Zickler A.M., El Andaloussi S. Dosing extracellular vesicles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021;178 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.113961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ankrum J.A., Ong J.F., Karp J.M. Mesenchymal stem cells: immune evasive, not immune privileged. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32(3):252–260. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and the writing of the paper.

Not applicable.