Abstract

Objective

To compare the success, failure rates and perinatal outcomes following emergency and elective cervical cerclage in singleton and twin pregnancies at a tertiary care perinatal centre over half a decade.

Methods

All pregnant women, both with singleton and twin pregnancies, who had cervical cerclage between June 2014 and May 2019 were included in the retrospective study. Success rates, failure rates, maternal complications and perinatal outcomes were compared in both groups.

Results

There were 129 women enrolled in the study, 48 in the emergency and 81 in the elective group. A significantly greater number of multiparous women were in the elective group (97.5% versus 68.7%; p-value < 0.001). Twins were nearly four times more in the emergency group as compared to the elective group. The mean cervical length at time of cerclage was 2.05 cm and 1.5 cm; (p-value < 0.001) respectively in the elective and emergency groups. Almost half of the women in the emergency group had bulging membranes. (52.2%). Following cerclage, mean gestational age at delivery was similar in both groups. However, more women in the elective group delivered at or beyond 34 weeks in comparison to the emergency groups (71% versus 53.3%. P-value 0.05). Preterm labour leading to preterm births was almost twice in the emergency group than elective group (49% versus 22%, P-value 0.002). Rates of maternal chorioamnionitis were similar in both groups. The overall live birth rates were comparable (81.3% versus 84.4% P-value 0.85) in both the groups. These results were also seen on doing subgroup analysis of elective versus emergency cerclage in singleton pregnancies only. Failure rates were also similar in both groups (18.7% versus 15.6%, P-value 0.85) Composite neonatal morbidity was more in the emergency group than in the elective group (35.5 versus 14%, P-value 0.01).

Conclusion

Live birth rates and failure rates were comparable following elective and emergency cerclage both overall and in singleton pregnancies. Maternal chorioamnionitis and neonatal sepsis rates were similar in both the groups. However, composite neonatal morbidity was higher in the emergency cerclage group.

Keywords: Cervical cerclage, Cervical length, Preterm birth, Preterm labour, Twins, Cervical insufficiency

Introduction

Cervical insufficiency (CI) is the progressive softening and shortening of the cervix leading to the expulsion of an otherwise, normal fetus. The estimated incidence of cervical insufficiency is 1% of all pregnancies and 8% of recurrent spontaneous mid-second trimester pregnancy losses. The treatment of CI is the placement of cervical cerclage.

Based on the urgency, the cerclage may be classified as elective and emergency. Elective or prophylactic cerclage is placed in women with history of previous losses in the mid trimester and is usually history-indicated. On the other hand, an emergency cerclage can be carried out anytime < 28 weeks (before the period of viability) in a woman with a short cervix and/or bulging membranes. This is usually either an Ultrasound (USG)-indicated or clinical examination-indicated cerclage [1]. Performing cervical cerclage in high-risk women improves perinatal outcomes by prolonging the period of Gestation [2, 3]. However, there is limited data comparing outcomes of pregnancies following emergency versus elective cerclage [4]. Some have found elective cerclage with better perinatal outcomes while others have found otherwise [3, 5].

Previously we had published data on the perinatal outcomes following emergency cerclage placement. That study included outcomes in both singletons and multiple gestations and we found overall good rates of live births. However, we did not compare these with outcomes following elective cerclage [6]. Hence this study was done to compare the obstetric and perinatal outcomes after elective and emergency cerclage during the same time period.

Our study aims to compare the success rates, failure rates, maternal and perinatal outcomes following elective and emergency cerclage in singleton and multiple gestations

Method and materials

Data of all women who underwent cervical cerclage between June 2014 and May 2019 were collected. Both singleton and multiple pregnancies were included. The study was approved by the Institutional review board and Ethics committee. Women were placed into elective and emergency cerclage groups, based on indication for cerclage.

Electronic medical records of all patients were retrieved from a computerized database. Age, body mass index (BMI), parity, gestational age at the time of cerclage, previous obstetric history, history of cerclage placement, any known associated factor (such as the presence of congenital uterine malformations history of cervical surgery, ascending genitourinary infection) were recorded.

Mean cervical length (CL) at the time of surgery, the presence or absence of protruding membranes, administration of perioperative antibiotics, progesterone, and tocolysis, and experience of the operating surgeon was also noted. Indications for the cerclage, clinical presentation, gestational age at delivery and perinatal outcome were noted. For the neonatal outcome, gestational age at delivery, birth weight, NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit) admission, neonatal morbidity and mortality were noted.

Pregnancies complicated by congenital fetal anomalies, preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), preterm labour and chorioamnionitis at the time of presentation, were excluded. Elective cerclage was carried out by either McDonald’s or modified Shirodkar’s technique, depending on surgeons' expertise while only McDonald’s stitch was used for the emergency procedure. Shirodkar’s method requires dissection of vaginocervical mucosa and a longer duration of surgery which makes it technically more difficult in emergency situations. Both techniques were performed under spinal anaesthesia. We did not use setons for any of these procedures.

In the McDonald’s method, a purse-string suture with a non-absorbable braided black silk suture no. 1 was placed around the cervix at the level of the internal os. In the Modified Shirodkar technique, the bladder was pushed cephalad after dissection of the vaginocervical mucosa and purse-string suture using mersilene (polyester monofilament) tape was placed at the level of the internal os. The knot was tied either anteriorly or posteriorly as per the preferance of the operating surgeon.

Women with dilated cervices and bulging membranes were placed in the reverse Trendelenburg position to facilitate spontaneous reduction of prolapsed membranes. Gentle pressure with a sponge on a stick was used to replace the membranes, if they were not spontaneously reduced after patient positioning. A single dose of a broad-spectrum antibiotic (third-generation cephalosporin) was used for surgical prophylaxis as per the hospital policy. We did not use perioperative tocolytics such as indomethacin for our emergency cases. However, micronized progesterone 200 mg PV Twice daily or injectable progesterone (25-hydroxy progesterone caproate 250 mg IM weekly) was used in all cases of emergency cerclage up to 34 weeks. The suture was removed after 37 completed weeks, or earlier, in cases of preterm labour or rupture of membranes.

The data was entered using the EPI DATA software and screened for outliers and extreme values using a Box-Cox plot and histogram (for the shape of the distribution). All categorical variables were reported using frequencies and percentages, continuous variables expressed as mean ± Standard deviation (SD) or Median (Interquartile range; IQR). Student’s t-test was used to compare the time interval between cerclage placement and delivery in both groups. The exact Fisher test was applied to the categorical for the comparison of elective and emergency cerclage. P < 0.05 is considered significant. All the statistical analyses were done using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) 25.0.

The primary outcomes assesed were success rates, failure rates, and the latent period between the cerclage placement and delivery in both groups. The success rate was defined as the percentage of pregnancies resulting in live births beyond 28 weeks, following cerclage placement. The failure rate was defined as the percentage of pregnancies resulting in either mid-trimester losses or stillbirths at or beyond 28 weeks. Stillbirth was defined as the birth of a fetus beyond 28 weeks without signs of life [7]. Early neonatal death was defined as the death of a live-born/baby in the first seven days of life [8].

Secondary outcomes studied were the rates of maternal complications like PPROM; preterm birth (PTB) and chorioamnionitis. Neonatal outcomes included the presence of neonatal sepsis and composite neonatal morbidities like hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, hypothermia, and hypocalcemia. Other Perinatal outcomes such as gestation age at birth, newborn birth weight and neonatal survival were also noted.

Results

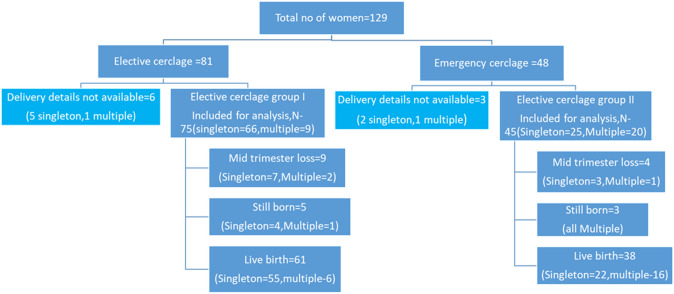

During the study period, 129 women had cerclage procedures: 81 women (62.8%) had elective cerclage and 48 women (37.2%) had emergency cerclage. Details about the delivery were missing for nine women (6 in the elective group and 3 in the emergency group) and hence were excluded from the analysis. Finally, 120 women (75 in the elective group and 45 in the emergency group) and 131 neonates were analyzed for the outcome (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study

The maternal characteristics in both groups are presented in Table 1. Singletons were 76% (98/129) whereas 24% (31/129) were multiple gestations in our cohort (Table 1). Multiple pregnancies were nearly four times more in the emergency group in comparison to the elective group (44% versus 12%, p-value < 0.001) (Table 1). This is because we do not offer elective/prophylactic cerclage to twin pregnancies in the absence of a history suggestive of CI.

Table 1.

Baseline maternal characteristics of women undergoing cervical cerclage (elective and emergency) at our hospital during study period

| Elective (N = 81) | Emergency (n = 48) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years)mean (± SD) | 29.06(± 4.62) | 27.4(± 5.89) | 0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (± SD) | 27.12(± 5.15) | 28.3(± 5.12) | 0.93 |

| Gravida, (N, %) | |||

| Primi | 2(2.5%) | 15(31.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Multi | 79(97.5%) | 33(68.7%) | |

| Mean GA* at cerclage (in weeks) (± SD) | 13.8(± 1.78) | 22.9(± 3.82) | 0.001* |

| Type of pregnancy (N, %) | |||

| Singleton | 71(87.7%) | 27(56.3%) | < 0.001** |

| Multiple | 10(12.3%) | 21(43.8%) | |

| No of first trimester miscarriage (N, %) | |||

| No | 17(21%) | 27(56.3%) | 0.005 |

| One | 25(30.9%) | 10(20.8%) | |

| Two | 21(25.9%) | 5(10.4%) | |

| Three or more | 18(22.2%) | 6(12.5%) | |

| Prev Mid trimester loss (N, %) | |||

| Yes | 59(72.8%) | 19(39.6%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 22(27.2%) | 29(60.4%) | |

| Previous mid-trimester loss (N, %) | |||

| None | 22(27.2%) | 29(60.4%) | < 0.003*** |

| One | 39(48.1%) | 12(25.0%) | |

| Two | 13(16%) | 3(6.3%) | |

| Three or more | 7(8.6%) | 4(8.3%) | |

| Previous death/Early neonatal deaths (N, %) | |||

| Yes | 17(21%) | 6(12.5%) | 0.53 |

| No | 64(79.0%) | 42(87.5%) | |

| Previous Still birth (N, %) | |||

| Yes | 14(17.3%) | 5(10.4%) | 0.33 |

| No | 67(82.7%) | 43(89.6%) | |

| Cause for cervical shortening (N, %) | |||

| Cervical surgery | 2(2.6%) | - | < 0.001 |

| Cervical trauma | - | - | |

| Congenital uterine malformation | 5(6.6%) | - | |

|

Ascending infection No cause identified |

8(10.5%) 66(80.3%) |

21(43.8%) 27(56.3%) |

|

|

Previous h/o cerclage (N, %) Yes No |

19(23.5%) 62(76.5%) |

2(4.2%) 46(95.8%) |

0.004 |

| Indication of cerclage (N, %) | |||

| (a) Short cervix on USG | 5(6.2%) | 19(39.6%) | |

| (b) Physical examination indicated: | 0 | 5(10.4%) | < 0.001 |

| (c) History based | 63(77.8%) | 4(8.3%) | |

| Combination of (a) and (b) | 8(9.9%) | 12(25.0%) | |

| Combination of (a) and (c) | 5(6.2%) | 4(8.3%) | |

| Combination of (b) and (c) | - | 4(8.3%) | |

| Cervical length (in cm) | |||

| ≤ 0.5 | 0 | 8(16.7%) | |

| 0.6–1.0 cm | 7(8.6%) | 8(16.7%) | 0.075 |

| 1.1–1.5 cm | 10(12.3%) | 10(20.8%) | |

| 1.6–2.0 cm | 31(38.3%) | 17(35.4%) | |

| 2.1–2.5 cm | 20(24.7%) | 3(6.25%) | |

| 2.6–3.0 cm | 13(16%) | 2(4.2%) | |

| Mean Cervical length (in cm) (± SD) | 2.05(± 0.6) | 1.53(± 0.71) | < 0.001 |

| Experience of the surgeon (n, %) | |||

| Senior Resident | 29(35.8%) | 32(66.7%) | |

| Consultant | 52(64.2%) | 16 (33.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Type of Suture material used | |||

| Silk | 38(46.9%) | 48(100%) | < 0.001# |

| Mersilene | 43(53.1%) | - | |

| Perioperative antibiotics | |||

| Yes | 64(79%) | 25(52.1%) | 0.001 |

| No | 17(21%) | 23(47.9%) | |

*Elective cerclage is done at 13–14 weeks whereas emergency procedure is done in late mid trimester, whenever cervical length is found to be short

**Since we do not offer elective cerclage to twin pregnancies in the absence of significant history, Emergency cerclage group had a greater number of twin pregnancies than elective

***There were significantly more pregnant women with no mid trimester losses in the emergency group. Those who had had history of mid trimester losses were more likely to be offered an elective cerclage in the subsequent pregnancies. However, few of these women planned for history indicated elective cerclage presented late in pregnancy with symptoms and needed emergency procedure

#Silk suture was used for both elective and emergency procedure whereas Mersilene was used only for elective (Shirodkar’s stitch)

Among women who underwent elective cerclage, 98% were multiparous as compared to only 68% of those undergoing emergency cerclage (Table 1). As elective cerclage was done in women with previous mid-trimester losses therefore more such women were found in the elective cerclage group than emergency 73% (59/81) Versus 40% (19/48,) (P-value < 0.001). Surprisingly, 14.6% women in emergency group had history of two or more mid trimester losses. Lack of awareness among these women regarding need for an elective procedure, made them present late in pregnancy with clinical findings suggestive of CI (Table 1).

Similarly 22 women in the elective group did not have any history of mid trimester losses but had cerclage placement either due to IVF (in vitro fertilisation) pregnancies or previous cervical surgeries. Two Primipara had elective cervical cerclage as both of them had prior cervical surgery like cervical conization and LEEP (Loop electrosurgical excision)

The mean GA (Gestational Age) at cerclage in elective and the emergency group was 13.8 ± 1.78 weeks and 22.9 ± 3.82 weeks; (p-value 0.001) (Table 1). Mean cervical length at the time of cerclage placement was 2.05 cm and 1.5 cm in the elective and emergency groups (P-value < 0.001) (Table 1).

About 50% (24/48) of patients undergoing emergency procedures had bulging membranes at the time of diagnosis. In the elective cerclage group, the mean cervical length of the women who delivered before and after 34 weeks was not different (Table 2). However, in the emergency cerclage group, the mean cervical length was significantly different in women delivering before and after 34 weeks (Table 3).

Table 2.

Maternal complications following cerclage placement in both groups

| Elective (n = 75) | Emergency (n = 45) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| “PPROM” * | 18(24.3%) | 11(24.4%) | 0.98 |

| Preterm labor | 16(21.6%) | 21(48.8%) | 0.002 |

| Preterm labour resulting in PTB ** | 14(18.9%) | 15(35.7%) | 0.045 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 7(9.3%) | 3(7.1%) | 0.68 |

*PPROM Preterm premature rupture of membrane, **PTB Preterm birth

Table 3.

Comparison of perinatal outcomes in elective and emergency cerclage groups

| Pregnancy outcomes | Elective (n = 75) | Emergency (n = 45) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid trimester loss (n, %) | 9; 12% | 4; 8.9% | 0.82 | |

| Still born (n, %) | 5; 6.7% | 3; 6.7% | 1 | |

| Failure rate (Mid trimester loss & stillbirths combined) (n, %) | 14; 18.7% | 7; 15.6% | 0.85 | |

| Pregnancies with live births beyond 28 weeks s (n, %) | 61; 81.3% | 38; 84.4% | 0.85 | |

| Latent period (in days ± SD*) | 142.5(± 49.6) | 67.7(± 46.2) | < 0.001 | |

| Mean GA at delivery (in weeks) (± SD) | 34.2(± 7.0) | 32.2(± 6.7) | 0.13 | |

| GA** at delivery following cerclage placement | < 34 weeks | 22(29.3%) | 21(46.7%) | 0.05 |

| > 34 weeks | 53(70.7%) | 24(53.3%) | ||

| Mean birth weight (in gm) (± SD) | 2532.41(± 794.8) | 2010.9 (± 926.6) | 0.003 | |

| Neonatal sepsis (N, %) | 9/67;13.4% | 8/54; 14.8% | 0.79 | |

| Composite neonatal morbidity (N, %) | 11/67;16.4% | 19/54; 35.2% | 0.01 | |

| Birth weight in singletons (in gms) Median IQR***) | 2730(2120, 3120) | 2500(965, 2945) | 0.17 | |

*Standard Deviation

**Gestational age

***Inter Quartile range

Overall success rates in terms of live birth rates were similar in both groups, (81.3% vs 84.4%; p-value 0.85, Table 3). Failure rates were also comparable across the groups (18.7% versus 15.7% P-values 0.85), Table 3). On doing subgroup analysis of singleton pregnancies only, the success and failure rates were also comparable (83% versus 88%, p value0.4, Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of perinatal outcomes following elective and emergency cerclage in singleton pregnancies (n = 91)

| Pregnancy outcome | Elective (n = 66) | Emergency (n = 25) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mid trimester loss (n, %) | 7/66, 10.6% | 3/25, 12% | 1 |

| Still born (n, %) | 4/66, 6.06% | 0 | - |

| Failure rate (n, %) | 11/66, 16.6% | 3/25, 12% | 0.92 |

| Pregnancies with live birth beyond 28 weeks birth (n, %) | 55/66, 83.3% | 22/25, 88% | 0.4 |

| Latent period (in days ± SD) | 146.3(± 48.7) | 82.1(± 49.4) | 0.6 |

| Mean GA at delivery (in weeks) (± SD) | 34.9(± 6.7) | 32.8(± 7.4) | 0.2 |

| Mean birth weight (in gm) (± SD) | 2644.0(± 734.8) | 2277(± 945) | 0.07 |

The latent periods in elective and emergency cerclage groups were 142 ± 49.6 days and 67.7 ± 46.2 days respectively (P-value < 0.001) (Table 3). This finding was expected as GA at cervical placement was nine weeks earlier in the elective cerclage group than the emergency group (Tables 1, 3).

Comparison of the primary outcomes based on the type of suture material used for the cerclage, braided (silk) versus monofilament (mersilene) showed Success and Failure rates were comparable in both groups (P-value 0.48 and 0.48) (Table 5). Moreover, the latent period in days and the mean GA at delivery were also comparable between the two groups (Table 5). Hence, in our study, neither material was found to be superior to the other.

Table 5.

Subgroup analysis of Perinatal outcomes following elective cerclage using silk and mersilene sutures (n = 75)

| Pregnancy outcome | Silk(n = 34) | Mersilene (n = 41) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mid trimester loss (n, %) | 4/34, 11.8% | 2/41, 4.9% | 0.5 |

| Still born (n, %) | 5/34, 14.7% | 5/41, 12.2% | 1 |

| Failure rate (n, %) | 9/34, 26.5% | 7/41, 17.1% | 0.48 |

| Pregnancies had Live birth (n, %) | 25/34, 73.5% | 34/41, 82.9% | 0.48 |

| Latent period (in days ± SD) | 141.2(± 51.2) | 143.6(± 48.9) | 0.9 |

| Mean GA at delivery (in weeks) (± SD) | 34.5(± 6.9) | 33.9(± 7.0) | 0.5 |

| Mean birth weight (in gm) (± SD) | 2545.4(± 823.3) | 2520(± 780) | 0.2 |

The mean birthweight of the neonates at delivery, was 2532.41(± 794.8) gm in the elective group and 2010.9(± 926.6) gms in the emergency group. This is due to presence of significantly greater number of twins in that group (p-value 0.003) (Table 3). However, on subgroup analysis of singleton pregnancies only, the difference in the mean birth weight was not statistically significant (2644gms versus 2227gms; p-value 0.07) (Table 4).

Maternal complications like PPROM, preterm labour or birth and chorioamnionitis after cerclage are shown in Table 2. Preterm labour was seen twice more often in the emergency group than elective group (P-value 0.002) (Table 2). However, rates of chorioamnionitis following the procedure were similar in both groups (P-value = 0.68) (Table 2). This could be explained by the fact that the emergency group had a significantly more proportion of twin gestations. (Table 1) We did not come across complications of traumatic postpartum haemorrhage or bucket handle tears of the cervix in our study.

Neonatal outcomes were available for 77 babies in the elective group and 54 in the emergency groups, (Fig. 1). Neonatal sepsis was similar in both groups (13.4% vs 14.8% p- value = 0.79, Table 3). This is probably because the rates of chorioamnionitis were similar in both groups (9%versus 7%, P-value 0.6, Table 2).

However, composite neonatal morbidity including hypoglycemia, suboptimal weight gain, hypothermia and hyperbilirubinemia was more than twice in the emergency group compared to the elective group (14.2% vs 35.2%; p-value 0.01) (Table 3). This could be explained by the presence of more twin gestations in the emergency group than in the elective group (Table 1).

On doing a sub-group analysis of singleton pregnancies only, we found that the success rates (83% versus 88%, p value0.4) and failure rates (17% versus 12%, p value 0.9) were comparable in both elective and emergency groups (Table 4). The success rates were higher and failure rates were lower in the emergency cerclage group once the twins were excluded from the analysis, although this was not statistically significant. (Table 4).

Discussion

In a 2017 Cochrane review, Alfirevic et al. reported that cervical cerclage reduces the risk of preterm birth and probably reduces risk of perinatal deaths in women at high‐risk of preterm birth . There was no no evidence to show the beneficial affect of cercelage based on previous obstetric history or short cervix indications. There were limited data for all clinical groups. [3].

History indicated /prophylactic cerclage is carried out at 11–14 weeks, and is a low-risk procedure that has been shown to reduce the risk of preterm births [3, 8]. In contrast, emergency cerclage is carried out in USG diagnosed short cervix or the presence of cervical dilatation with bulging membranes on clinical examination is potentially associated with an increased risk of complications, such as chorioamnionitis and rupture of membranes [9].

In our study, USG indicated cerclage was included in the emergency cerclage group, since we do not offer a universal screening of CL in asymptomatic women. Routine screening for short cervix using CL measurement, at target scans, is not carried out at our hospital. Instead, cervix was assessed by eyeballing on trans- abdominal scans and only if there is suspicion of short cervix, was a TVS (transvaginal sonography) done to measure the CL. CL was also measured when women presented with either of the following symptoms: lower abdominal pain; pelvic pressure and spotting per vaginum

The highlight of our study was the inclusion of twins in both groups. The majority of twins were in the emergency cerclage group than the elective group, 44% versus 12% respectively (Table 1). Prophylactic cerclage has not shown to be of benefit in twins, it has, on the contrary, it has been found to increase preterm births and a non-significant increase in perinatal mortality [2]. In a recent RCT, physical examination indicated cerclage in women with twins and cervical dilatation between 1 and 4 cm was found to decrease PTB by 50% and perinatal mortality by 78% [10].

Based on the above findings, ISUOG (International Society of Ultrasound Obstetrics and Gynaecology) guidelines recommend that there may be a role for physical examination indicated cerclage in asymptomatic twins with cervical dilatation before 24 weeks of pregnancy [1]

The cut-offs of CL used as a threshold for cerclage placement in twins is another area of contention. While some recommend 2.5 cm as a cut-off [1], others have used 2 cm [11] or 1.5 cm as a cut-off [12, 13]. Similar to Lim et al. we used a cut-off of 2 cm as the threshold for placement of cerclage [14].

In this study overall success and failure rates were comparable in elective and emergency groups both overall and in singleton pregnancies alone (Table 4).

Liddiard A et al. reported no statistical difference between the live-birth rate, and the mean birth weight. However, they found a marginal difference in the gestation age at delivery between the two groups [15]

We also compared the success and failure rates based on the type of suture material, braided or monofilament, used for the procedure (Table 5). We found that either suture materials for cerclage had comparable success and failure rates. Also, the perinatal outcomes in both the suture groups were comparable (Table 5).

Success rates and mid-trimester loss rates were similar in both groups (Table 3) despite having a significantly greater number of twins in the emergency group and half of them presenting with protruding membranes. These findings demonstrate that the careful and stringent selection of candidates for emergency cerclage is of paramount importance for the success of the cerclage. We excluded all women who had clinical Chorioamnionitis, PPROM or established labour.

The success of the procedure (especially emergency cerclage) also depends on other factors such as the experience of the operating surgeon, strict asepsis and robust surgical technique. In our study, the majority of the procedures were performed by senior obstetricians. We gave peri-operative antibiotics in all cases of emergency cerclage. (Table 1)

Gluck et al. compared the obstetric outcomes of patients admitted with cervical dilatation or shortened cervical length managed conservatively, to those who underwent elective or history-indicated cerclage. The authors found that the gestational week at delivery and birthweights were similar for both groups [9].

In a meta-analysis including seven studies, the emergency cerclage group had significantly lower gestational age at delivery and birth weights and a higher risk of membrane rupture [16]. In our study, however, we found that the live birth rates, mid-trimester loss and still birth rates were comparable in both groups (Table 3).

On subgroup analysis of singleton pregnancies, there were significantly lesser stillbirths in the emergency group (n=0 versus 4) than in the elective group. (Table 4). As expected, excluding twins resulted in fewer stillbirths in this group as compared to the elective group. Although this is clinically significant, statistical significance could not be demonstrated due to the lack of a comparator in the emergency group (Table 4).

Liddiard et al. also showed no difference in gestational age in weeks, birthweight, live birth rates or newborn requiring neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) between emergency and the prophylactic cerclage groups [15]. However, the complication rate was higher in emergency cerclage patients compared to the prophylactic cerclage group. Similar to ours, they also had more twins in the emergency group.

On comparing neonatal outcomes in both the groups, we found that babies born to women with emergency cerclage were significantly smaller than those born in the elective cerclage group (2000 gms versus 2500 gms, P-value 0.003, Table 3). Although there was no significant difference in the gestational ages at delivery in both groups (P-value 0.13), (Table 3). This was because of a significantly greater number of twins in the emergency group. (Table 1) When we compared birthweights of babies in singleton pregnancies, these were similar in both groups (Table 4).

Composite neonatal morbidity was seen significantly more in the emergency group (35% versus 16%, Table 3).

However, Neonatal sepsis rates were comparable in both groups (Table 3). This was due to similar rates of maternal chorioamnionitis in both elective and emergency cerclage groups (Table 2).

The associated maternal complications in cervical cerclage are preterm labour, chorioamnionitis and preterm rupture of membranes which may result in early delivery with increased neonatal morbidity [17].

Drassinover et al. reported that complication rates were lower following the elective cerclage than the emergency procedure, although this was not statistically significant. However they had not included twins in their analysis [18].

Lee et al. reported that rates of preterm labour and preterm births were twice in the emergency group in comparison to the elective group [19].

We had similar observations, however, the rates of maternal chorioamnionitis were comparable in both the groups (9.3% versus; P-value 0.68) (Table 2). Since maternal chorioamnionitis rates, post procedure, were similar in both emergency and elective groups, preterm labour with or without birth is more likely to have been a consequence of twins, which were significantly more in the emergency group, rather than procedure related complication per se.

The limitations of our study are that it was retrospective, single centre and non-randomised. Hence a lot of data is dependent upon the treating physician's notes.

The strengths of the study are that we included both singletons and twins in our study. Also, we compared maternal outcomes after cerclage and outcome after different type of suture materials.

Conclusion

Success rates and failure rates, were similar in both the groups both overall and in singleton pregnancies alone. There was no difference in outcomes based on the type of suture material (braided or monofilament) used.

Excluding twins from the emergency group, resulted in fewer stillbirths in the emergency group in comparison to the elective group. The rates of maternal chorioamnionitis following cerclage placement were similar in both groups. Preterm labour was twice more common in the emergency group. Neonatal sepsis rates were similar in both groups, however, the composite neonatal morbidity was significantly more in the emergency cerclage group.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Taken from institutional review board.

Informed consent

Not taken (Retrospective study).

Footnotes

Pushplata Kumari is Associate Professor, DGO, MS; Manisha Madhai Beck is Professor and Unit Head, MD; Manish Kumar is Professor, DM; Tresasa Joseph is Associate Professor, MS, MRCOG, FRM (Reproductive Medicine); Meenakshi Kumari is Associate Professor, DGO, MS; Bijesh Yadav is Lecturer, PhD (Biostatistics).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Coutinho CM, Sotiriadis A, Odibo A, Khalil A, D’Antonio F, Feltovich H, et al. ISUOG practice guidelines: role of ultrasound in the prediction of spontaneous preterm birth. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol Off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2022;60(3):435–456. doi: 10.1002/uog.26020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berghella V, Odibo AO, To MS, Rust OA, Althuisius SM. Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography: meta-analysis of trials using individual patient-level data. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(1):181–189. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000168435.17200.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Medley N. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;18(6):CD008991. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008991.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berghella V. Cerclage decreases preterm birth: finally the level I evidence is here. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(2):89–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gluck O, Mizrachi Y, Ginath S, Bar J, Sagiv R. Obstetrical outcomes of emergency compared with elective cervical cerclage. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med Off J Eur Assoc Perinat Med Fed Asia Ocean Perinat Soc Int Soc Perinat Obstet. 2017;30(14):1650–1654. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1220529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumari P, Kumar M, David LS, Vijayaselvi R, Yadav B, Beck MM. A retrospective study analyzing indications and outcomes of mid-trimester emergency cervical cerclage in a tertiary care perinatal centre over half a decade. Trop Doct. 2022;52(3):391–399. doi: 10.1177/00494755221080590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawn JE, Gravett MG, Nunes TM, Rubens CE, Stanton C. The GAPPS review group. global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (1 of 7): definitions, description of the burden and opportunities to improve data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10(1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Final report of the Medical Research Council/Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists multicenter randomised trial of cervical cerclage MRC/RCOG working party on cervical cerclage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100(6):516–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics The american college of obstetricians and gynaecologists. practice bulletin no. 130: prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964–973. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182723b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roman A, Zork N, Haeri S, Schoen CN, Saccone G, Colihan S, et al. Physical examination-indicated cerclage in twin pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(6):902.e1–902.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG practice bulletin No. 142: cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 Pt 1):372–379. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000443276.68274.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li C, Shen J, Hua K. Cerclage for women with twin pregnancies: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(6):543–557.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.11.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Chen M, Cao T, Zeng S, Chen R, Liu X. Cervical cerclage in twin pregnancies: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;260:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim AC, Hegeman MA, In H, et al. Cervical length measurement for the prediction of preterm birth in multiple pregnancies: a systematic review and bivariate meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol Off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(1):10–17. doi: 10.1002/uog.9013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liddiard A, Bhattacharya S, Crichton L. Elective and emergency cervical cerclage and immediate pregnancy outcomes: a retrospective observational study. JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2(11):91. doi: 10.1258/shorts.2011.011043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Q, Chen G, Li N. Clinical effect of emergency cervical cerclage and elective cervical cerclage on pregnancy outcome in the cervical-incompetent pregnant women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;297(2):401–407. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins RD, Saade G, Polin RA, Grobman WA, Buhimschi IA, Watterberg K, et al. Evaluation and management of women and newborns with a maternal diagnosis of chorioamnionitis: summary of a workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(3):426–436. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drassinower D, Coviello E, Landy HJ, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Perez-Delboy A, Friedman AM. Outcomes after periviable ultrasound-indicated cerclage. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med Off J Eur Assoc Perinat Med Fed Asia Ocean Perinat Soc Int Soc Perinat Obstet. 2019;32(6):932–938. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1395848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee M, Rossi RM, DeFranco EA. Severe maternal morbidity associated with cerclage use in pregnancy. J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med Off J Eur Assoc Perinat Med Fed Asia Ocean Perinat Soc Int Soc Perinat Obstet. 2021;26:1–7. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2021.1903424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]