Abstract

Introduction: Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) is a secondary complication from radiotherapy, which is difficult to manage and significantly reduces the life quality of the affected patients.

Case Report: A 59-year-old female patient, diagnosed with infiltration by squamous cell carcinoma in the left cervical region, underwent adjuvant cervical-facial radiotherapy with a total dose of 66.6 Gy of radiation. Eight years after the diagnosis, the patient underwent multiple extractions and, subsequently, the installation of osseointegrated implants, evolving to extensive intraoral bone exposure associated with oral cutaneous fistula. The patient was initially exposed to photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT), with a low-power laser at wavelengths of 660 nm and 808 nm, and thereafter to antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT). After an improvement in the clinical condition and resolution of the oral cutaneous fistula, a surgical procedure with the Er: YAG laser was performed to remove the remaining necrotic bone. Once the ORN condition was completely treated, the patient’s oral rehabilitation was implemented by the installation of an upper mucous-supported total prosthesis and a lower implant-supported prosthesis.

Conclusion: The patient is in a clinical follow-up and has no signs of bone necrosis recurrence, suggesting that low and high-power laser treatment can be an effective therapeutic alternative to resolve this condition.

Keywords: Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws, Low intensity light therapy, Er-YAG laser, High power laser, Drug-related osteonecrosis of the jaws, Implant Dentistry

Introduction

Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) is a serious and debilitating complication, secondary to radiotherapy1. It was first reported in 1922 and later became more frequently described in the jaws when the practice of head and neck tumor radiation became established.1,2 Today, it presents a higher incidence in the mandible due to anatomical characteristics of the region, such as the presence of denser and less vascularized bone, with rates ranging from 2% to 22%, despite the great advances in dentistry and the development of less aggressive radiotherapy treatments.1-3 Most ORN cases, around 70%, occur in the first three years after completing radiotherapy treatment.2,3

Several risk factors have been associated with a higher rate of development of the condition, such as the location of the primary tumor, local bone infiltration, dental surgical procedures in the previously irradiated area, radiotherapy modality, radiation dose, and poor oral health status.3,4

Over the years, it has received several definitions, and currently, it is best defined as an area of bone and soft tissue necrosis, located in a region that previously received radiation, without evidence of tumor persistence or recurrence. It can compromise the bone superficially or deeply and may present a chronic or acute course, being accompanied by painful symptoms, trismus, fistula and pathological fractures, leading to a significant loss of life quality, which justifies the use of prophylactic and therapeutic measures.2,3

Regarding the treatment of ORN, there is no consensus in the literature, which can be explained by the lack of a universally accepted classification and little understanding of the pathophysiology of this condition.5 The management of ORN seeks to stop the process and remove the associated symptoms, and it can be carried out by combining conservative measures with more invasive measures, such as surgical resection.6-8 For patients diagnosed with ORN in the initial or subclinical phase, the use of conservative measures seems to be well indicated. These measures include the control of oral hygiene, the use of hyperbaric oxygen, he use of antibiotic therapy, and the use of low-power laser and surgical debridement.5-8 For cases that do not respond satisfactorily to conservative treatment or in which the necrotic bone is exposed, a surgical procedure is necessary, with or without the reconstruction of vascularized tissue.5,8 There is no effective drug protocol to interrupt the disease process, although the PENTOCLO protocol has achieved important clinical results in reducing the need for major surgeries, being effective only in the initial stages.5

Lasers have been widely used in current dentistry, being seen as an innovative technology that could replace conventional techniques, mainly high-power lasers, or stimulate tissue repair, analgesia, and modulation of the inflammatory process (low-power lasers).8,9 When interacting with tissues, lasers stimulate angiogenesis, produce collagen, regenerate muscle, reduce inflammation and edema, stimulate nerve regeneration, and form cartilage and bone through the proliferation of osteocytes, which leads to bone remodeling and acceleration of tissue repair.10 Lasers can be divided into low-power lasers, used to perform photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT), and high-power lasers, used to perform surgical procedures, both in soft and bone tissues. There is also antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT), which uses the interaction between a light source and a dye to develop antimicrobial action.10,11

High-power lasers (HILT, high-intensity laser treatment), also called surgical lasers, transform light energy into thermal energy, triggering photothermal effects, such as carbonization, coagulation, ablation, and vaporization.10 They are used for bone tissue removal, coagulation, decontamination, dentin melting, and acid resistance in enamel. The Er-YAG laser has a wavelength in the infrared spectrum (2940 nm), resonant with the biological tissue and with surface action, reducing the risk of heat transmission to neighboring structures as its energy is consumed by the thermo-mechanical ablation process.10,11

The objective of this article is to report the case of a patient affected by ORN after implant placement in the mandibular region and to present the treatment proposed to resolve the condition, suggesting a care protocol with low- and high-power lasers. Initially, PBMT was used with a low-power laser in red and infrared wavelengths, aiming at reducing symptoms and improving the patient’s quality of life. Subsequently, the patient also underwent aPDT and, for complete resolution of the condition, the remaining necrotic bone was removed with the high-power Er:YAG laser.

Case Report

A 59-year-old female patient was diagnosed with infiltration by squamous cell carcinoma in the left cervical region. In the same year, she started adjuvant cervical-facial radiotherapy treatment, which continued until the following year to a total of 66.6 Gy of radiation. Eight years after the diagnosis, the patient underwent the extraction of the right and left canines, central incisors, and mandibular lateral incisors and, after seven months, she had surgery to install five morse taper implants (Implacil, 3.5x13) in the region.

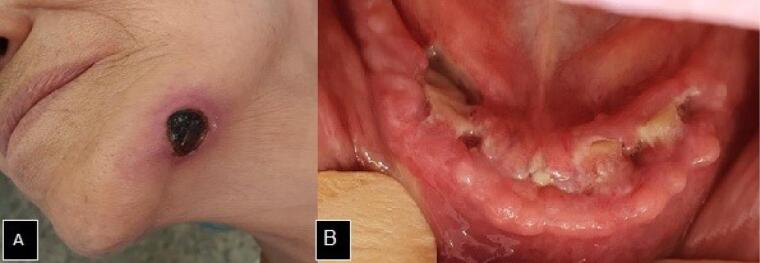

In December of the same year of the teeth extractions, the patient complaining of pain in the mandibular region associated with the extraoral lesion sought dental care. During the extraoral physical examination, the presence of an extensive ulcerated lesion was observed, with an erythematous halo and necrotic center on the left of the base of the mandible, which communicated with an intraoral ulcer, and characterized the presence of an oral cutaneous fistula. On the intraoral examination, there was an ulcerated lesion with an interruption in the continuity of the buccal mucosa and exposure of the necrotic bone throughout the anterior alveolar crest region of the mandible (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A. Extraoral cutaneous fistula in the mandible base region. B. Exposure of necrotic bone in the alveolar crest of the mandibular anterior region

The patient’s treatment began with PBMT through the application of a low-power laser (Therapy XTR- Diode laser, DMC, São Carlos, SP, Brazil), with a fixed power of 100 mW, a wavelength of 660 nm (red) with 4 J applied per intra- and extraoral site, and a wavelength of 808 nm (infrared) with 4 J applied per intraoral site. This procedure aimed to improve the quality of the tissue affected by ORN and reduce pain symptoms in order to provide a better quality of life to the patient.

After 2 months of performing PBMT, treatment with aPDT (aPDT) was established through low-power laser irradiation (Therapy XTR- Diode laser, DMC, São Carlos, SP, Brazil), with a fixed power of 100 mW and a wavelength of 660 nm. The energy of 9 J was applied per intraoral point and 4 J per extraoral point after previous photosensitization with 0.01% methylene blue dye solution (Chimiolux, DMC, São Carlos, SP, Brazil) for 5 minutes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A. Photosensitization with 0.01% methylene blue for 5 min. B. Low-power laser irradiation.

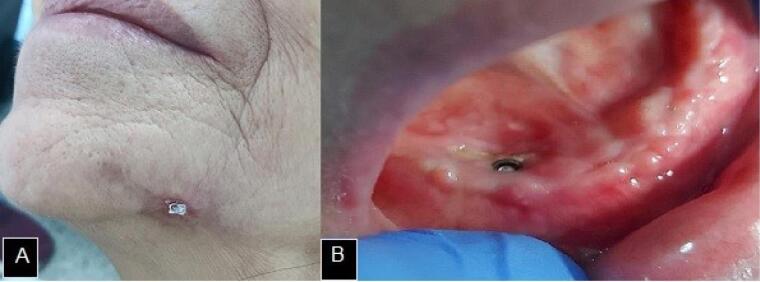

The procedure was performed weekly and, after four weeks, there was a significant reduction in the skin lesion. After 8 months during which the aPDT was set, there was a partial covering of the intraoral bone exposure, with only an area of exposed necrotic bone at the right canine site, associated with the osseointegrated implant (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A. Significant reduction of the cutaneous fistula. B. Partial covering of intraoral mandibular bone exposure

In order to completely end the case, the patient went through the surgical removal of the remaining bony sequestrum with the Er-YAG laser (Fotona, Lightwalker ATSM021-5AF/1S, Ljubljana, Slovenia, λ = 2940 nm), under constant irrigation, in continuous mode, with 150 mJ of energy, 20 Hz of frequency and 3.0 W of power. The surgical procedure was achieved under local anesthesia and ended with the closure of the surgical wound by primary intention using simple stitches.

In the 30-day postoperative follow-up, the surgical wound showed an excellent healing aspect with a partial covering of the bone tissue, with only a small area of bone exposure remaining in the lingual region of the alveolar ridge, which characterized the interruption and regression of the ORN process (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A. Transoperative with the Er:YAG laser. B. Immediate postoperative period. C. Healing aspect 30 days after the surgical procedure. D. Final aspect after mini-implant placement

Three months after the surgery, with the total intraoral bone exposure already covered, the patient’s oral rehabilitation was initiated through the installation of 5 mini-implants. The reopening of the oral mucosa after the period of osseointegration was performed with a high-power laser (Thera Lase Surgery – 808 nm Diode Laser, DMC, São Carlos, SP, Brazil) in continuous mode and with 1.5 W of power.

One month later, the lower implant-supported prosthesis and the upper total mucous-supported prosthesis were installed, completing the patient’s oral rehabilitation and life quality restoration. After one year of follow-up, the patient does not present clinically or radiographically evidence of bone necrosis relapse. The entire treatment is represented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Treatment Flowchart

Discussion

ORN affects the jaws at a prevalence of 2% to 22%, a prevalence that has been decreasing due to intensive dental guidance and the introduction of intensity-modulated radiation therapy, despite continuing to be a significant side effect for radiotherapy4. Its highest incidence is in the mandible, when compared to the maxilla, in a ratio of 24:1, with a positive correlation being identified between the primary site of the tumor and the increased incidence of ORN, as observed in the presented case.1,4

The ORN prevention involves a previous evaluation and dental treatment. Teeth with infection or with a poor prognosis, which are included in the irradiation area, must be removed prior to antineoplastic treatment, respecting an adequate healing time before starting therapy.5 If extraction is not possible before starting treatment, it should be postponed for about 9 to 12 months after the end of radiotherapy treatment with the use of antibiotic prophylaxis. In addition, the dental follow-up of the cancer patient must take place throughout the radiotherapy treatment.5,6,7

The patient in this case report underwent cervical-facial radiotherapy treatment with a total dose of 66.6 Gy and exhibited mandibular ORN after multiple extractions and implant installations in the anterior mandibular region. Among the factors associated with the development of this condition, there are those related to the tumor, such as its primary site and proximity to bone tissue, those related to the treatment, such as the radiotherapy dose, the irradiated mandibular volume, the radiation field, and the dose fractioning, and those related to the patient, in which tooth extraction after radiotherapy and oral health conditions are the main risk factors for its development.3,4,12,13

Once it is set, ORN is difficult to manage and it significantly reduces the patient’s quality of life. In the search for more effective, less painful treatments that can stop the progression of the condition, in addition to improving the patients’ well-being affected by bone necrosis of the jaws, when conservative treatment has not been effective, surgical lasers have been presented as an alternative to mechanical cutting and drilling. However, carbon dioxide and neodymium lasers tend to have deleterious effects, such as protein carbonization and denaturation, unlike the erbium laser whose energy is transported along the tissue that has undergone ablation, leaving little thermal energy to damage the surrounding tissue.5,9

The efficacy of PBMT in wound repair and activation of bone metabolism is supported in the dentistry literature by studies that point out its effects on inflammation modulation, healing process stimulation by inducing the proliferation and transformation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, angiogenesis increase, and release of growth factors that accelerate the formation and deposition of type I and III collagen. Furthermore, aPDT is able to eliminate opportunistic microorganisms without microbial resistance.14,15 The main effects related to the use of PBMT and aPDT in the management of complications arising from cancer treatment, including bone necrosis, are the reduction of painful symptoms, the improvement of the wound healing process, and the elimination of opportunistic microorganisms. These outcomes justify the use of both therapies since besides being minimally invasive therapies without significant adverse effects, they preserve the patient’s masticatory functions and promote life quality improvement, ensuring a good general health status15,16. Due to these effects, when PBMT and aPDT are applied in the preoperative period, they improve the condition of the adjacent tissue, contributing to a better prognosis after performing a more invasive procedure.17-19

For its wavelength, the Er:YAG laser has water and hydroxyapatite as its main chromophores, which explains its ablation mechanism, in which the hard tissue is heated and evaporated by laser energy. Additionally, its wavelength is promptly absorbed by major bone components, such as organic and inorganic matrix, and calcium salts.18,20 Therefore, it has a great ability to remove necrotic bone besides its biomodulation effect on both soft and hard tissues.17-20 Its use produces minimum side effects, as the fragments removed by ablation carry most of the energy with them, leaving little thermal energy that can damage the surrounding tissues, unlike CO2 and Nd:YAG lasers, which tend to present deleterious effects such as carbonization and denaturation of proteins.9,19

The use of phototherapy in the treatment of osteonecrosis associated with the use of medications, especially PBMT and aPDT, has been successfully presented in the academic literature; however, the management of ORN through the association with low- and high-power lasers is still little publicized, which justifies the relevance of disseminating this clinical case to the scientific community. Porcaro et al20 performed the surgical removal of necrotic bone tissue in the maxilla of a patient diagnosed with ORN, after treatment with systemic antibiotic therapy and guidance on local hygiene, using the Er:YAG laser with the same parameters applied in this clinical case. Regarding the parameters used to perform LLLT and aPDT, the same parameters had been successfully used by Ribeiro et al15 in the presentation of a series of ORN cases.

Conclusion

The outcome of the present clinical case, in which there was a resolution of the bone necrosis and further oral rehabilitation of the patient to restore her quality of life, suggests that the use of low- and high-power lasers and photodynamic therapy compose a safe and effective alternative therapy.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Elenice Lika Kawamoto, Paulo Yataro Kawakami.

Data curation: Larissa Couto de Freitas, Ana Maria Aparecida Souza, Luciane Hiramatsu Azevedo.

Formal analysis: Elenice Lika Kawamoto, Paulo Yataro Kawakami, Luciane Hiramatsu Azevedo.

Funding acquisition: Alyne Simões Gonçalves, Luciane Hiramatsu Azevedo.

Investigation: Larissa Couto de Freitas, Alyne Simões Gonçalves, Luciane Hiramatsu Azevedo.

Methodology: Alyne Simões Gonçalves, Luciane Hiramatsu Azevedo.

Project administration: Luciane Hiramatsu Azevedo.

Resources: Elenice Lika Kawamoto, Ana Maria Aparecida Souza, Paulo Yataro Kawakami.

Software: Luciane Hiramatsu Azevedo.

Supervision: Alyne Simões Gonçalves.

Validation: Luciane Hiramatsu Azevedo.

Visualization: Elenice Lika Kawamoto, Ana Maria Aparecida Souza, Paulo Yataro Kawakami.

Writing–original draft: Larissa Couto de Freitas.

Writing–review & editing: Larissa Couto de Freitas, Alyne Simões Gonçalves, Luciane Hiramatsu Azevedo.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with the institutional and national research committee’s ethical standards, and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Please cite this article as follows: de Freitas LC, Kawamoto EL, Souza AMA, Kawakami PY, Gonçalves AS, Azevedo LH. Use of phototherapy and Er-YAG laser in the management of mandible osteoradionecrosis: a case report. J Lasers Med Sci. 2023;14:e58. doi:10.34172/jlms.2023.58.

References

- 1.Chrcanovic BR, Reher P, Sousa AA, Harris M. Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws--a current overview--part 1: physiopathology and risk and predisposing factors. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;14(1):3–16. doi: 10.1007/s10006-009-0198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chronopoulos A, Zarra T, Ehrenfeld M, Otto S. Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws: definition, epidemiology, staging and clinical and radiological findings A concise review. Int Dent J. 2018;68(1):22–30. doi: 10.1111/idj.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aarup-Kristensen S, Hansen CR, Forner L, Brink C, Eriksen JG, Johansen J. Osteoradionecrosis of the mandible after radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: risk factors and dose-volume correlations. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(10):1373–7. doi: 10.1080/0284186x.2019.1643037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jereczek-Fossa BA, Orecchia R. Radiotherapy-induced mandibular bone complications. Cancer Treat Rev. 2002;28(1):65–74. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2002.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camolesi GC, Ortega KL, Medina JB, Campos L, Lorenzo Pouso AI, Gándara Vila P, et al. Therapeutic alternatives in the management of osteoradionecrosis of the jaws Systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2021;26(2):e195–e207. doi: 10.4317/medoral.24132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bessereau J, Annane D. Treatment of osteoradionecrosis of the jaw: the case against the use of hyperbaric oxygen. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(8):1907–10. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rice N, Polyzois I, Ekanayake K, Omer O, Stassen LFA. The management of osteoradionecrosis of the jaws–a review. Surgeon. 2015;13(2):101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin T, Zhou M, Li S, Wang Y, Huang Z. Preoperative status and treatment of osteoradionecrosis of the jaw: a retrospective study of 252 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;58(10):e276–e82. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dostalova T, Jelinkova H. Lasers in dentistry: overview and perspectives. Photomed Laser Surg. 2013;31(4):147–9. doi: 10.1089/pho.2013.3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Paula Eduardo C. Fundamentos de Odontologia – Lasers em Odontologia. São Paulo: Guanabara Koogan; 2013.

- 11. Lago ADN. Laser na Odontologia: Conceitos e Aplicações Clínicas. São Luís: EDUFMA; 2021.

- 12. MD Anderson Head and Neck Cancer Symptom Working Group. Dose-volume correlates of mandibular osteoradionecrosis in oropharynx cancer patients receiving intensity-modulated radiotherapy: results from a casematched comparison. Radiother Oncol. 2017;124(2):232-9. 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Kojima Y, Yanamoto S, Umeda M, Kawashita Y, Saito I, Hasegawa T, et al. Relationship between dental status and development of osteoradionecrosis of the jaw: a multicenter retrospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2017;124(2):139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Freitas PM, Simoes A. Lasers in Dentistry: Guide for Clinical Practice. Weinheim: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015.

- 15.Ribeiro GH, Minamisako MC, da Silva Rath IB, Santos AMB, Simões A, Pereira KCR, et al. Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws: case series treated with adjuvant low-level laser therapy and antimicrobial photodynamic therapy. J Appl Oral Sci. 2018;26:e20170172. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2017-0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Momesso GAC, Lemos CAA, Santiago-Júnior JF, Faverani LP, Pellizzer EP. Laser surgery in management of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: a meta-analysis. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;24(2):133–44. doi: 10.1007/s10006-020-00831-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magalhães IA, Forte CPF, Viana TSA, Teófilo CR, de Matos Brito Lima Verde R, Magalhães DP, et al. Photobiomodulation and antimicrobial photodynamic therapy as adjunct in the treatment and prevention of osteoradionecrosis of the jaws: a case report. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2020;31:101959. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fornaini C, Cella L, Oppici A, Parlatore A, Clini F, Fontana M, et al. Laser and platelet-rich plasma to treat medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ): a case report. Laser Ther. 2017;26(3):223–7. doi: 10.5978/islsm.17-CR-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rugani P, Acham S, Truschnegg A, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Jakse N. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws: surgical treatment with ErCrYSGG-laser Case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110(6):e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porcaro G, Amosso E, Mirabelli L, Busa A, Carini F, Maddalone M. Osteoradionecrosis of the posterior maxilla: a new approach combining erbium:yttrium aluminium garnet laser and Bichat bulla flap. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26(7):e627–9. doi: 10.1097/scs.0000000000002136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]