Abstract

β-Ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) synthetase II (KAS II) is one of three Escherichia coli isozymes that catalyze the elongation of growing fatty acid chains by condensation of acyl-ACP with malonyl-ACP. Overexpression of this enzyme has been found to be extremely toxic to E. coli, much more so than overproduction of either of the other KAS isozymes, KAS I or KAS III. The immediate effect of KAS II overproduction is the cessation of phospholipid synthesis, and this inhibition is specifically due to the blockage of fatty acid synthesis. To determine the cause of this inhibition, we examined the intracellular pools of ACP, coenzyme A (CoA), and their acyl thioesters. Although no significant changes were detected in the acyl-ACP pools, the CoA pools were dramatically altered by KAS II overproduction. Malonyl-CoA increased to about 40% of the total cellular CoA pool upon KAS II overproduction from a steady-state level of around 0.5% in the absence of KAS II overproduction. This finding indicated that the conversion of malonyl-CoA to fatty acids had been blocked and could be explained if either the conversion of malonyl-CoA to malonyl-ACP and/or the elongation reactions of fatty acid synthesis had been blocked. Overproduction of malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase, the enzyme catalyzing the conversion of malonyl-CoA to malonyl-ACP, partially relieved the toxicity of KAS II overproduction, consistent with a model in which high levels of KAS II blocks access of the other KAS isozymes to malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase.

Fatty acids comprise a major fraction of the cellular dry weight (4) of Escherichia coli and are found in two types of molecules. In phospholipids the acids are esterified to sn-glycerol-3-phosphate, and these lipids make up the leaflets of the cytoplasmic membrane lipid bilayer and the inner leaflet of the outer membrane. In lipid A the fatty acids form the hydrophobic anchor of the hydrophilic outer membrane polysaccharides (22). E. coli synthesizes four major fatty acids, C14:0 (myristate), C16:0 (palmitate), C16:1 (palmitoleate), and C18:1 (cis-vaccenate) (4). Two minor components, laurate (C12:0) and 3-hydroxymyristate, are found exclusively in lipid A, whereas palmitate, palmitoleate, and cis-vaccenate are components of the phospholipids.

All fatty acids in E. coli arise from a single pathway that branches at the 10-carbon stage into the saturated and unsaturated arms (4, 17). Most of the enzymes of the pathway have broad substrate specificities and are used at all stages of the synthetic pathway (for details, see reference 17). The first step in the cyclic pathway is the condensation of malonyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) with the growing acyl chain catalyzed by a β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase (KAS) (the acyl chain is esterified to the thiol group on ACP in the case of KAS I and KAS II but to coenzyme A [CoA] in the case of KAS III [4, 17]). Both KAS I (encoded by fabB) and KAS II (encoded by fabF) elongate the saturated intermediates of the pathway, but each catalyzes a reaction within the unsaturated branch that the other cannot. KAS I is essential for elongation of the unsaturated moieties, whereas the C16:1-to-C18:1 elongation is carried out by KAS II (5, 7, 9, 10, 23). KAS III encoded by fabH is thought to function in initiation of acyl chains (4, 12, 17, 29).

The elongation of palmitoleoyl-ACP to cis-vaccenoyl-ACP by KAS II is sensitive to growth temperature and is utilized by E. coli in order to optimize cell membrane fluidity (6). This elongation activity is temperature dependent in that at lower temperatures the Km for palmitoleoyl-ACP decreases and the relative Vmax increases (7, 10). To study the enzyme in more detail, several laboratories, including our own, have attempted to clone the fabF gene and thereby overproduce KAS II (7, 16, 26), as had previously been done for KAS I and KAS III. Although the fabF sequence had been obtained by the sequencing of partial clones and PCR products (16, 26), numerous attempts to clone the intact fabF gene failed despite the use of a wide variety of vectors and host strains. In contrast, cloning and subsequent manipulation of the other KAS isozyme encoding genes, fabB and fabH, proceeded without complications (6, 7, 26, 29). Edwards and coworkers (7) finally succeeded in cloning fabF by using a vector in which the gene was expressed from a synthetic promoter-operator controlled by the E. coli lacI repressor. We have found that upon induction of strains carrying this plasmid, cell growth and viability decrease rapidly, thus explaining previous failures to clone the intact fabF gene. In this study we have explored the source of this unexpected toxicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains were grown at 37°C (unless otherwise mentioned) in rich broth (RB) or minimal E medium supplemented with 0.5% vitamin-free casein hydrolysate, 5 μM β-alanine, and a carbohydrate carbon source as given. When necessary, the media were supplemented with 25 μg of Timentin (SmithKline Beecham), 30 μg of spectinomycin, or 7 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. Timentin is a mixture of an impermeable β-lactamase inhibitor clavulanic acid (which inhibits extracellular β-lactamase) and the β-lactam antibiotic, ticarcillin. This mixture provides a much stronger and more constant selection for the maintenance of ampicillin-resistant plasmids.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Sourcea |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| UB1005 | metB gyrA λ+ | Lab stock |

| SJ16 | UB1005 panD | Lab stock |

| DK577 | pKH16 in SJ16 | Lab stock |

| SS83 | pQE8 in DK577 | This study |

| SS85 | pCGN4851 in DK577 | This study |

| SS86 | pCGN4851 and pMSD15 in DK577 | This study |

| SS87 | pQE8 and pMSD15 in DK577 | This study |

| SS175 | pSS94 in DK577 | This study |

| SS176 | pSS95 in DK577 | This study |

| SS180 | pSS99 in DK577 | This study |

| SS210 | pCE33 and pCGN4851 in DK577 | This study |

| SS211 | pSS94 and pCGN4851 in DK577 | This study |

| SS212 | pSS95 and pCGN4851 in DK577 | This study |

| SS213 | pSS99 and pCGN4851 in DK577 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKH16 | lacIq | K. Hughes |

| pQE8 | LacI-controlled vector | Qiagen |

| pKM22 | E. coli fabD | 17 |

| pCGN4851 | fabF in pQE30 | 7 |

| pMSD15 | ′tesA under araBAD promoter p15A origin | M. Davis |

| pCE33 | Temperature-inducible origin of replication and λPL promoter | 8 |

| pSS94 | E. coli fabD in pCE33 | This study |

| pSS95 | Mutant E. coli fabD in pCE33 | This study |

| pSS99 | B. subtilis fabD in pCE33 | This study |

Lab stock from laboratory collection.

DNA manipulation and analysis.

Plasmid DNA was purified on Qiagen columns (Hilden, Germany). PCR products were obtained as recommended by the manufacturer (Ready-To-Go PCR Beads; Pharmacia Biotechnology) with plasmids carrying either E. coli or Bacillus subtilis DNA as templates. Plasmids pSS94 and pSS95 were obtained by digestion of pSS88 and pSS89, respectively, with BamHI and BglII and by cloning the smaller plasmid fragment into the BamHI site of pCE33 (8), thus placing the fabD gene under the λPL promoter of the vector. Plasmid pSS88 was obtained by PCR amplification of the insert of plasmid pKM22 (18) with primers 5′-GGAGATCTATGACGCAATTTGCATTT-3′ and 5′-GCGGATCCTCTTTTAAAGCTCGAGCGCCGCTGCC-3′ followed by cloning into an intermediate vector before transfer into pCE33. Plasmid pSS99 was obtained by PCR amplification of the fabD gene of plasmid pRMU100a (18) with primers BSFABDN (5′-GAGGATCCAACAGATGAGTAGTCTGGA-3′) and BSFABDC (5′-TTGGATCCTTAAGCATTATCATTC-3′) followed by cloning into plasmid pCR2.1 (Invitrogen). The insert was then subcloned into pCE33 as a BamHI fragment. Insert orientations were determined by PCR. Site-directed mutagenesis of the fabD gene of pSS88 was performed by using the MutaGenesis kit from Bio-Rad with the oligonucleotide 5′-CCCCCAGGCAGTGACCGGC-3′, which converted the essential-active-site serine to cysteine. The mutation was confirmed both by DNA sequencing and the inability of plasmids carrying the mutant gene to complement a temperature-sensitive E. coli fabD mutant at the nonpermissive temperature (18, 19).

Lipid and fatty acid analyses.

Cultures were grown to mid-exponential phase in RB or minimal E medium, and 1 ml of culture was transferred to a tube containing either sodium [1-14C]acetate (5 μCi of 55 Ci/mol) or [1-14C]palmitate (2 μCi of 8.4 Ci/mol) and then incubated for a further 30 min at 37°C. A chloroform-methanol solution (6 ml, 1:2, by volume) was added to the labeled cultures plus 0.6 ml of a stationary-phase culture added as a carrier to ensure quantitative recovery. Lipid extraction and fractionation by Silica Gel G thin-layer chromatography were done as previously described (3, 13) with plates from Analtech, Inc., and developed with the following solvent systems: petroleum ether-ethyl ether-acetic acid (70:30:2) to the top of the plate followed by chloroform-methanol-acetic acid (65:25:8) to three-fourths of the plate height. Methyl esters of fatty acids were generated by base-catalyzed transesterification (13) and separated on a silver nitrate (20%)-impregnated Silica Gel G HL plate (Analtech, Inc.) with toluene at −15°C as the solvent.

CoA metabolite analysis.

Cultures were grown overnight in minimal E dextrose medium supplemented with 0.5% vitamin-free casein hydrolysate and 50 μCi of β-[3-3H]alanine (60 Ci/mmol). These cultures were subcultured in medium of the same composition and grown to mid-log phase, and samples were then taken before and after induction with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Culture samples (1 ml) were transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, and trichloroacetic acid was added to a final concentration of 6%. The sample preparation was as previously described (24). The high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis used a protocol modified from that of Roughan (24) with a starting buffer concentration of 98.8% solvent A (ammonium acetate, 50 mM [pH 5.0]) and 1.2% solvent B (acetonitrile) adjusted to a final concentration of 80% A–20% B over 40 min. Radioactivity was measured by a flow-through scintillation counter attached in series to the HPLC apparatus.

RESULTS

Toxicity of KAS II overproduction.

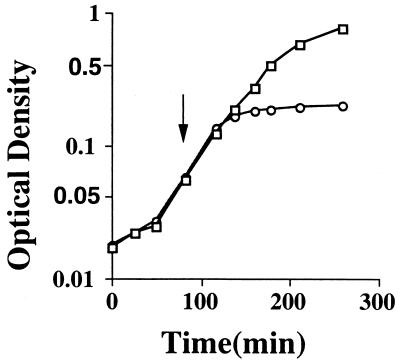

Plasmid pCGN4851 of Edwards and coworkers (7) consists of a fabF PCR product inserted between the SphI and HindIII sites of plasmid pQE30 (Qiagen; see also reference 27), thus placing the promoterless fabF gene downstream of the vector promoter and upstream of the efficient rrnB transcription terminator. The fabF reading frame was fused to the vector-derived N-terminal His tag, which did not affect its activity as measured by in vitro assays (7). Expression of the vector phage T5 promoter is regulated by two copies of the lac operator; one overlapping the −10 and −35 regions and a second located downstream of the −10 region. Upon induction of fabF expression by the addition of IPTG, the production of KAS II resulted in a rapid inhibition of the growth of strain SS85 that carried plasmid pCGN4851, whereas strain SS83 carrying the vector plasmid continued to grow normally (Fig. 1). In some experiments the growth curve failed to plateau, but this was due to the growth of cells that had lost the plasmid (as shown by their sensitivity to ampicillin, the selective marker encoded by plasmid pCGN4851). Viable cell counts assayed by colony formation on ampicillin-containing medium (which lacked IPTG) showed that fewer than 1 in 105 cells remained viable following 15 min of IPTG induction. The inhibition of growth and the loss of viability were not blocked by the addition of cerulenin, a specific inhibitor of KAS I and KAS II. Upon removal of cerulenin, strain SS83 carrying the vector plasmid remained viable and formed colonies in the absence of IPTG, whereas strain SS85 failed to form colonies. Therefore, KAS II activity was not required for the toxic effects. It should be noted that we sequenced the fabF gene of pCGN4851 to preclude the possibility that a mutant gene had been cloned or subsequently selected. The fabF sequence that we obtained was identical to that reported earlier by this (16) and other (1, 26) laboratories.

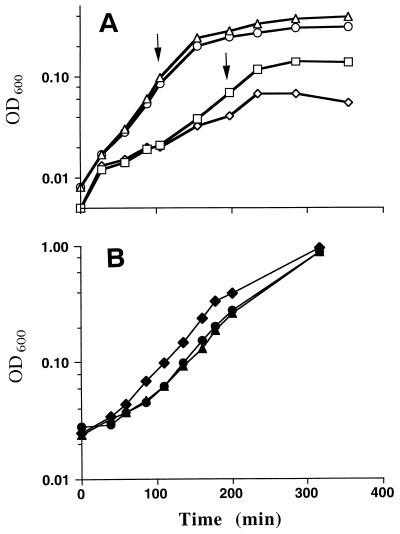

FIG. 1.

Growth inhibition upon overproduction of KAS II of E. coli. Strain SS83 carrying the vector plasmid (□) and strain SS85 carrying the fabF plasmid pCGN4851 (○) were grown in RB overnight at 37°C and subcultured 1:100 into fresh medium at 37°C. The optical density at 600 nm was measured at intervals, and IPTG was added to 0.1 mM at the time indicated by the arrow.

Effects on lipid synthesis.

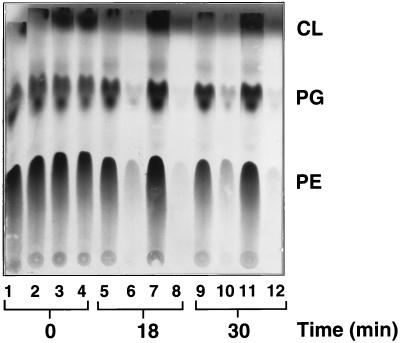

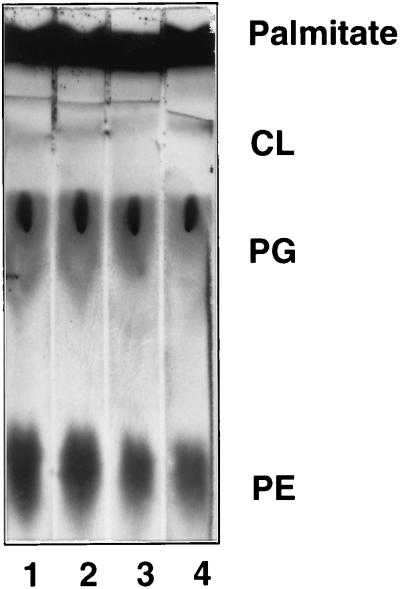

KAS II is an enzyme of fatty acid synthesis, and thus an effect on lipid synthesis seemed the most straightforward explanation for the observed growth inhibition upon FabF overproduction. This explanation was tested by pulse-labeling cultures of strains SS83 and SS85 with [14C]acetate before and after induction with IPTG. Thin-layer chromatography and autoradiography of the extracted lipids (Fig. 2) showed that the incorporation of [14C]acetate into the phospholipid fraction of the FabF-overproducing strain SS85 was rapidly blocked, whereas labeling of the phospholipid fraction of the control strain SS83 proceeded normally. Similar results were obtained when incorporation into the fatty acid moieties was assayed directly (data not shown). Phospholipid synthesis depends directly on fatty acid synthesis, but the reverse situation is also true since inhibition of phospholipid synthesis blocks fatty acid synthesis through feedback inhibition (3, 14). Therefore, our labeling results could be explained by an action exerted at either level of the lipid synthetic pathway. To test if the inhibitory effect of FabF overproduction was exerted at the level of fatty acid synthesis or at the level of phospholipid synthesis (or both), strains SS83 and SS85 were labeled with [14C]palmitic acid under the same conditions used for [14C]acetate labeling. The incorporation of this full-length fatty acid into phospholipid was unaffected (Fig. 3) by the overproduction of KAS II. Therefore, the inhibition of fatty acid synthesis upon overproduction of KAS II was a direct effect rather than an indirect effect mediated through the inhibition of phospholipid synthesis.

FIG. 2.

Lipid synthesis from [14C]acetate in cultures overproducing FabF. The autoradiogram of a Silica Gel G thin-layer chromatogram of the total extractable lipids of E. coli is shown. Cultures were grown in minimal E salts with glucose (strains SS83 and SS85) or arabinose (strains SS86 and SS87). Strain SS83 that carried the vector plasmid and strain SS85 that carried the fabF plasmid pCGN4851, plus derivatives of these strains, SS87 and SS86, respectively, that also contained the ′tesA thioesterase-encoding plasmid, pMSD15, were labeled. Samples (1 ml) of cultures were withdrawn for labeling with [14C]acetate at the times indicated after addition of IPTG. The cultures were then labeled for 30 min before lipid extraction. In each set of four lanes, the first lane is strain SS83, the second is strain SS85, the third is strain SS87, and the fourth is strain SS86, with the times of [14C]acetate addition as indicated. The amounts loaded per lane were normalized by evaluation of the optical densities at 600 nm of cultures.

FIG. 3.

Lipid synthesis from [14C]palmitate in cultures overproducing FabF. The autoradiogram of a Silica Gel G thin-layer chromatogram of the total extractable lipids of E. coli is shown. Samples of strain SS83 (lanes 1 and 3) which carries the vector plasmid and strain SS85 which carries the fabF plasmid pCGN4851 (lanes 2 and 4) were labeled before induction with IPTG (lanes 1 and 2) or after induction (lanes 3 and 4). Cultures were grown overnight in the glucose medium described in the legend to Fig. 2, subcultured into the same medium, and grown to mid-log phase. Samples (1 ml) were taken before and after IPTG addition and labeled with 2 μCi of [14C]palmitate (8.4 Ci/mol) for 30 min before lipid extraction.

Acyl-ACP pools.

Prior work from this laboratory strongly suggests that fatty acid synthesis is regulated by feedback inhibition of a fatty acid synthetic enzyme(s) (3, 14). This raised the possibility that overproduction of FabF might result in the accumulation of a species of acyl-ACP which could act as an unusually potent feedback inhibitor. We have done two types of experiments that indicate that feedback inhibition is not involved. First, we assayed the chain lengths and abundance of the acyl-ACP species present at the onset of the inhibition of lipid synthesis by FabF overproduction. These studies were done with a range of gel electrophoresis conditions that allow the resolution of acyl chain lengths ranging from C2 to C22 (11, 21). We were unable to detect any unusual or abnormal species either qualitatively or quantitatively (data not shown). In our second approach, strain SS85 was transformed with plasmid pMSD15, which carries a modified tesA gene encoding a form of E. coli thioesterase I that becomes trapped in the cytosol and relieves the inhibition of fatty acid synthesis observed upon blocking phospholipid synthesis (3). In this strain, SS86, thioesterase expression is controlled by the E. coli araBAD promoter. Induction of strain SS86 with arabinose failed to relieve the toxicity of FabF, although free fatty acid production indicated cleavage of the cellular acyl-ACPs. Indeed, thioesterase production seemed to exacerbate the toxic effect of FabF overproduction in that a greater inhibition of lipid synthesis was seen than that produced by FabF overproduction alone (Fig. 2), a result that was in agreement with our observation that strains overexpressing both the modified TesA and FabF (SS86) showed a more rapid cessation of growth upon IPTG addition than did strains with the fabF plasmid pCGN4851 alone (data not shown).

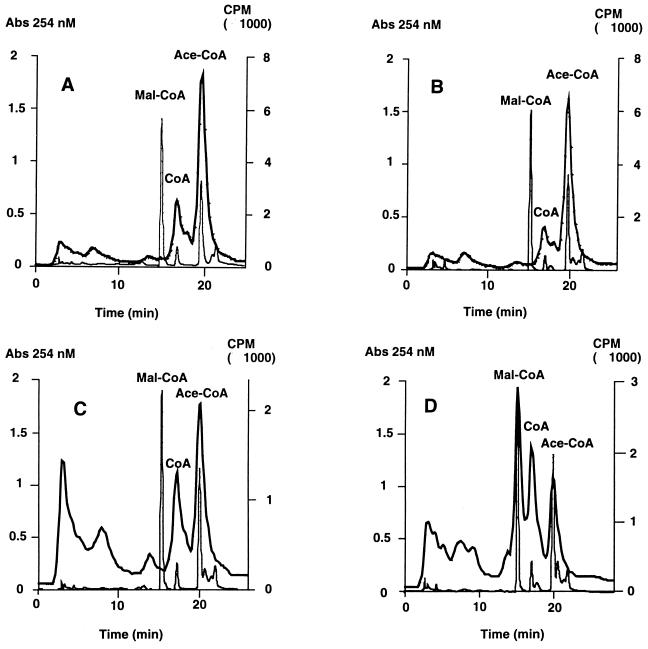

CoA thioester pools.

If the fatty acid synthetic step blocked upon overproduction of FabF is in an early step of fatty acid synthesis, the effect might be reflected in the pools of CoA, acetyl-CoA, and malonyl-CoA. The first committed step in fatty acid synthesis is the formation of malonyl-CoA from acetyl-CoA catalyzed by acetyl-CoA carboxylase. The malonyl-CoA so formed is utilized only in the synthesis of fatty acids. To enter fatty acid synthesis, the malonate moiety must be transferred from CoA to ACP, the reaction catalyzed by malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase, the fabD gene product. The equilibrium of malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase is very strongly biased towards the CoA ester (15). This bias, along with the intracellular excess of CoA over ACP (12, 30), means that the malonyl-CoA pool is a much more sensitive indicator of inhibition of either the production or the utilization of malonyl-CoA than is the malonyl-ACP pool.

We labeled the intracellular CoA esters by growing strains SS83 (carrying the vector plasmid) and SS85 (carrying the fabF plasmid pCGN4851) with tritiated β-alanine, a specific CoA precursor (these strains are β-alanine auxotrophs due to a lesion in the panD gene). The intracellular CoA compositions of cultures of strain SS85 (Fig. 4D) in which FabF overproduction was induced were compared with an uninduced culture (Fig. 4C) and with the compositions of control strain SS83 cultures induced with IPTG (Fig. 4B) or left uninduced (Fig. 4A). Induction of FabF overproduction in strain SS85 (Fig. 4D) resulted in a dramatic increase in the level of malonyl-CoA. Malonyl-CoA, which normally comprises about 0.5% of the total cellular CoA (11, 31), increased to about 40% of the total CoA pool within 12 min of induction of FabF overexpression. This increase was largely at the expense of acetyl-CoA. IPTG addition to strain SS83 (Fig. 4B) did not affect the levels of any CoA species. It should be noted that the various strains differ in the levels of β-[3-3H]alanine-labeled metabolites that elute from the HPLC column before the CoA esters. These compounds (which can also be seen in the chromatograms of Heath and Rock [11]) are assumed to be intermediates (4-phosphopanthetheine, 4-phosphopantothenate, and dephospho-CoA) in the synthesis and/or degradation of CoA (12, 30, 31). Since we have also observed these compounds in extracts of a strain that overproduces acetyl-CoA carboxylase and grows normally, we do not believe these compounds play any direct role in the FabF overproduction toxicity. Jackowski and coworkers (12, 30, 31) have shown that the metabolism of these intermediates is complex and is subject to control by unknown metabolic signals.

FIG. 4.

Effects of KAS II overproduction on pools of CoA metabolites. Strain SS83 which carried the vector plasmid (A and B) and strain SS85 which carried the fabF plasmid, pCGN4851 (C and D), were assayed before (A and C) and after (B and D) induction of KAS II overproduction. Cultures were grown overnight with β-[3-3H]alanine to label the CoA esters and then subcultured into the same medium and grown till early-log phase. Samples of the cultures (1 ml) were transferred to a microcentrifuge tube containing trichloroacetic acid to a final concentration of 6%. The induced cultures received 0.1 mM IPTG, and the induction period was 15 min. A mixture of unlabeled CoA, malonyl-CoA, and acetyl-CoA (to a concentration of 10 μM each) was added to each trichloroacetic acid extract as an internal standard. The samples were prepared and analyzed as described by Roughan (24), except that CoA and the CoA esters were first extracted on a C18 Sep-Pak column before being separated by HPLC on a C18 column. The thick lines indicate the radioactivity traces of the tritiated CoA compounds, and the thin lines indicate the A254 values of nonradioactive internal standards added to correct for losses during sample preparation.

Overproduction of malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase relieves FabF overproduction toxicity.

There are two possible mechanisms that could dramatically alter the cellular malonyl-CoA levels. An increase in acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity could increase the malonyl-CoA pool. Davis and Cronan (unpublished data) have shown that the coordinate overexpression of the four acetyl-CoA carboxylase subunits markedly increases the rate of fatty acid synthesis in vivo. Therefore, increased malonyl-CoA pools should stimulate rather than inhibit fatty acid synthesis, the opposite of the result we observed.

The second mechanism is the inhibition of KAS action. The dramatic increase in malonyl-CoA that we observed is essentially identical to that observed by Heath and Rock (11) upon the inhibition of KAS I and KAS II by cerulenin. Moreover, cerulenin inhibition does not markedly increase the malonyl-ACP pool (11), a result consistent with that found upon FabF overproduction. Therefore, the dramatic increase in malonyl-CoA upon FabF overproduction indicates that excess production of one KAS isozyme, FabF, results in blocking the action of the other two KAS isozymes, isozymes I and III.

One plausible mechanism for the blockage of synthase action by the overproduction of KAS II is that the three KAS isozymes all interact with a key enzyme of fatty acid synthesis and that massive overproduction of KAS II blocks essential interactions of synthases I and/or III with this enzyme. The most likely protein to interact with the KAS isozymes is the fabD gene product, malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase, which provides malonyl-ACP, an unstable KAS substrate required for the elongation reaction. If FabD were the target of KAS II overproduction, we expected that overproduction of the target should relieve toxicity by providing sufficient FabD to allow some productive association of the transacylase with KAS I and/or KAS III. We therefore cloned the E. coli fabD gene into plasmid pCE33 such that it would be transcribed from the powerful vector PL promoter of phage lambda. This plasmid also undergoes a large increase in copy number (hence increased enzyme production) upon a shift to elevated growth temperatures (8).

Overproduction of FabD did partially relieve the effects of FabF overproduction. Upon overproduction of E. coli FabD, strains continued growth for a longer period following induction of FabF overproduction (Fig. 5) and also protected fatty acid synthesis from inhibition upon FabF overproduction. The incorporation of [14C]acetate into fatty acids continued for at least twice as long when both FabD and FabF were overproduced (Fig. 6). Overproduction of FabD had little or no effect on the growth of strains lacking plasmid pCGN4851 (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Growth of strains overproducing KAS II in the presence of high levels of FabD. (A) All strains carried the fabF plasmid, pCGN4851, and either a fabD plasmid or the pCE33 vector used for fabD expression. Strain SS210 carried the vector plasmid (□), strain SS211 carried pSS94, which encodes wild-type E. coli FabD (▵), strain SS212 carried pSS95, which encodes a form of E. coli FabD lacking the essential-active-site serine (◊), and strain SS213 carried pSS99, which encodes wild-type B. subtilis FabD (○), were grown overnight in RB at 30°C and then subcultured into fresh medium at room temperature. The culture flasks were transferred to a shaking water bath at 25°C, and the bath was then set to 40°C and allowed to warm as the cultures grew to induce the expression of the FabD protein under the thermally regulated λPL promoter and to increase the copy number (8). After about 2 h, when the cells had reached mid-log phase, the cultures were induced for KAS II overproduction by the addition of IPTG at the time points shown. Growth was monitored by measuring change in absorption at 600 nm. (B) Control growth curves of strains expressing the three types of FabD. Strain SS175 carried pSS94 (▴), strain SS176 carried pSS95 (⧫), and strain SS180 carried pSS99 (•) in strain DK577. The cultures were grown as described for panel A. OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

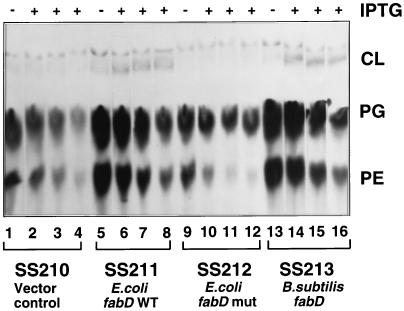

FIG. 6.

Lipid synthesis from [14C]acetate in cultures overproducing FabF and FabD. The autoradiogram of a Silica Gel G thin-layer chromatogram of the total extractable lipids of E. coli is shown. [14C]acetate labeling of strains SS210, SS211, SS212, and SS213 was done before and after induction of pCGN4851 with 0.1 mM IPTG. Strains were grown overnight at 30°C in RB and then diluted into fresh medium at room temperature. The temperature of the shaker was then set to 40°C to induce expression from the plasmid pCE33 derivatives as described in the legend to Fig. 5. All strains carried the fabF plasmid, pCGN4851, and either a fabD plasmid or pCE333, the vector used for fabD expression. Strain SS210 (lanes 1 to 4) carried the vector plasmid, strain SS211 carried pSS94, which encodes wild-type E. coli FabD (lanes 5 to 8), strain SS212 carried pSS95, which encodes a form of E. coli FabD lacking the essential active site serine (lanes 9 to 12), and strain SS213 carried pSS99, which encodes wild-type B. subtilis FabD (lanes 13 to 16). After 2 h of FabD expression, IPTG was added to 0.1 mM. In each set of four lanes, the first lane shows the lipids of cultures labeled before the addition of IPTG and the second, third, and fourth lanes show the lipids of cultures labeled 10, 20, and 30 min after the addition of IPTG, respectively. The amounts loaded per lane were normalized by measuring the optical densities at 600 nm of cultures.

The effects of FabD overproduction on FabF toxicity required an enzymatically active FabD protein. Plasmid pCE33 carrying a mutant fabD that lacked activity (the essential-active-site serine [25] was changed to cysteine by site-directed mutagenesis) failed to relieve FabF toxicity and instead appeared to exacerbate the toxicity. In contrast, expression of B. subtilis FabD from plasmid pCE33 relieved toxicity as efficiently as did the overproduction of E. coli FabD.

DISCUSSION

FabF overproduction has a drastic and rapid effect on growth and fatty acid synthesis in E. coli. Within 12 min of induction, fatty acid synthesis comes to a halt and cultures begin to lose viability. The lack of any major change in the ACP and acyl-ACP pools as measured by confirmationally sensitive urea gels suggests that the toxicity mediated by FabF is not due to an aberrant enzymatic function of the enzyme.

The most immediate effect of FabF overproduction is the accumulation of malonyl-CoA to about 30 to 40% of the total cellular CoA, an increase of ca. 80-fold over the normal level of this specific fatty acid precursor. Increased malonyl-CoA is symptomatic of a block in fatty-acid-chain elongation, since blocking elsewhere in the fatty acid synthetic cycle (e.g., enoyl-ACP reductase) or in the transfer of fatty acids to glycerol 3-phosphate has no effect on malonyl-CoA pools (11). Therefore, we are left with the surprising and counterintuitive result that overproduction of an active KAS isozyme blocks overall chain elongation. We envision three different mechanisms to explain this puzzling result.

First, studies with thiolactomycin suggest that KAS I (FabB) may be the only KAS isozyme essential for the growth of E. coli, since the overproduction of FabB suffices to restore growth in the presence of this antibiotic, an inhibitor of all three KAS isozymes (28). A caveat to these results is that thiolactomycin inhibition is reversible and thus loss of KAS activity in vivo could not be ascertained by assay of the enzyme activities of extracts of the treated cells. This caveat aside, since FabB and FabF are both homodimeric proteins and share some sequence relatedness, it is possible that upon overproduction of FabF, the FabB becomes sequestered as inactive FabF-FabB heterodimers. Indeed, FabB has been reported to readily dissociate into inactive monomers, whereas FabF remains a stable dimer under the same in vitro conditions (7). There are no data supporting or precluding the possibility of heterodimer formation, but this hypothesis seems unable to explain FabF toxicity. First, the resulting strains should exhibit the same growth phenotype as a fabB mutant, i.e., unsaturated fatty acid auxotrophy and cell lysis in the absence of supplementation with an appropriate unsaturated fatty acid (e.g., oleate). However, cultures of strains that overproduce FabF do not lyse, nor is growth rescued by the addition of oleate (or oleate plus palmitate) to the medium. It should be noted that exogenously added 3-hydroxymyristate, the characteristic fatty acid of lipid A, cannot be incorporated into this essential outer membrane component, and therefore exogeneous supplementation is unable to completely bypass blocks early in the fatty acid synthetic pathway (16).

A second possibility is that the very high levels of FabF bind and sequester much of the cellular malonyl-ACP. This possibility seems unlikely since the accumulation of malonyl-CoA and not malonyl-ACP is observed. If the cellular malonyl-ACP was bound to FabF, it should be sequestered from FabD and not be converted back to malonyl-CoA. Moreover, any malonyl-ACP bound to FabF would be released due to the destabilizing effects of the urea present in the gel electrophoretic separations plus the weak binding of malonyl-ACP to the KAS isozymes observed in vitro and hence should have been detected.

For these reasons we favor a third model, one which hypothesizes that in the normal course of fatty acid synthesis the KAS enzymes are associated with malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase (FabD). Overproduction of FabF results in most of the FabD being bound to FabF, leaving little FabD available for association with KAS I and/or KAS III, and the resulting lack of some essential chain elongation reaction catalyzed by either of these enzymes (which cannot be catalyzed by FabF) is responsible for the cellular toxicity. Although the data of Tsay and coworkers (28) implicate KAS I as the most important KAS isozyme, an effect on KAS III cannot be excluded. Indeed, FabF overproduction did not trigger the appearance of the short-chain acyl-ACPs that accumulate during cerulenin treatment when KAS I and KAS II are inactivated and KAS III remains functional (11). This finding suggests that KAS III, as well as KAS I, is inhibited upon FabF overproduction. Indeed, overproduction of FabB fails to reverse the effect of FabF overproduction on growth (data not shown). The physiological effects of a lack of KAS III are unknown, since no fabH mutants that lack KAS III activity have yet been isolated.

Our finding that overproduction of FabD partially relieves the inhibitory effects of FabF on growth and fatty acid synthesis provides support for the direct interaction model. In this model increased FabD would titrate FabF and allow productive association of FabD with the other KAS isozymes. We believe the partial nature of the FabD effect that we observed is due to our inability to produce sufficient FabD protein to totally counter FabF overproduction. The enormously high level of FabF production by the powerful T5 promoter plasmid overwhelms the high level of FabD produced by plasmid CE33. We have unsuccessfully attempted to titrate FabF production by manipulation of the IPTG concentrations under conditions in which LacY permease is inactive. High concentrations (≥10 μM) of IPTG completely inhibited growth, whereas at 1 μM IPTG neither protein overexpression nor growth inhibition was seen. These effects directly correlate with protein overexpression (no detectable FabF overexpression below 10 μM IPTG and massive overproduction above this concentration). It should be noted that the properties of the composite QE phage T5-lac operator-promoter that regulates FabF expression have not been described in the literature. However, we have found that the basal level of expression from this promoter is very low (as claimed by the commercial supplier) and that the level of expression depends very strongly on the levels of both IPTG and LacI. These properties indicate that LacI regulation of promoter action by binding to the tandem operators is extremely cooperative and suggests an involvement of DNA looping (20).

The finding that an active site mutant of E. coli FabD (which presumably retains native structure due to the conservative amino acid substitution made) failed to protect cells from the effects of FabF indicates that malonyl-CoA synthesis is required to ameliorate the effects of FabF overproduction. Moreover, high-level production of the inactive malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase potentiated the inhibitory effect of FabF overproduction, a result predicted by our model. The inactive FabD would bind KAS I and KAS III, thus blocking the infrequent association of these proteins with the small amount of active FabD that is not bound by FabF. It should be noted that FabD is a monomer (15, 24) and thus the inhibitory effect of the mutant FabD cannot be explained by dimer formation between active and inactive FabD proteins. Finally, our finding that B. subtilis FabD is as effective as the E. coli protein in relieving FabF overproduction is interesting in that this organism does not make palmitoleoyl-ACP, the preferred KAS II substrate (18).

Two other points deserve mention. First, a useful and potentially interesting observation is that the toxic effects of FabF are temperature dependent (data not shown). IPTG concentrations which kill strain SS85 at 42°C have a delayed and slower response at 30°C, although the final levels of FabF protein expression are comparable at the two temperatures. The delay in FabF action could be due to a lower rate of fatty acid synthesis. Another possibility is that the increased relative activity of FabF at low temperatures (7, 10) may reflect an altered protein conformation having a decreased affinity for FabD. Second, we have observed no inhibition of fatty acid synthesis in vitro by extracts of cells in which FabF was overexpressed (data not shown). This result can probably be attributed to the weakness of the interaction between FabD and FabF plus the massive dilution accompanying extract preparation.

In conclusion, the present data may provide the first evidence of a protein-protein interaction in bacterial fatty acid synthesis. If so, the toxic effects of FabF overproduction could be viewed as a substrate-channeling mechanism run amok. Future experiments will attempt to test for FabF-FabD interaction by the use of the yeast two-hybrid system which can detect weak interactions. Moreover, it seems unlikely that high-level production of FabF will be toxic to yeast cells because yeasts use a type I fatty acid synthesis pathway, and thus the major problem of working with this protein in E. coli will be avoided.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant AI15650.

We thank David Keating for useful suggestions regarding this work and Grattan Roughan for advice on the HPLC separations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bligh E G, Deyer E J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho H, Cronan J E., Jr Defective export of a periplasmic enzyme disrupts regulation of fatty acid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4216–4219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cronan J E, Jr, Rock C O. Biosynthesis of membrane lipids. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 612–636. [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Agnolo G, Rosenfeld I S, Vagelos P R. Multiple forms of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthetase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:5289–5294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Mendoza D, Klages Ulrich A, Cronan J E., Jr Thermal regulation of membrane fluidity in Escherichia coli: effects of overproduction of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase I. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:2098–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards P, Nelsen J S, Metz J G, Dehesh K. Cloning of the fabF gene in an expression vector and in vitro characterization of recombinant fabF and fabB encoded enzymes from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1997;402:62–66. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01437-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elvin C M, Thompson P R, Argall M E, Hendry P, Stamford N P, Lilley P E, Dixon N E. Modified bacteriophage lambda promoter vectors for overproduction of proteins in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1990;87:123–126. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90503-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garwin J L, Klages A L, Cronan J E., Jr β-Ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase II of Escherichia coli: evidence for function in the thermal regulation of fatty acid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:3263–3265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garwin J L, Klages A L, Cronan J E., Jr Structural, enzymatic, and genetic studies of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases I and II of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:11949–11956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heath R J, Rock C O. Regulation of malonyl-CoA metabolism by acyl-acyl carrier protein and β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15531–15538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackowski S, Rock C O. Metabolism of 4-phosphopantheteine in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:115–129. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.1.115-120.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackowski S, Rock C O. Acetoacetyl-acyl carrier protein synthase, a potential regulator of fatty acid biosynthesis in bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:7927–7931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang P, Cronan J E., Jr Inhibition of fatty acid synthesis in Escherichia coli in the absence of phospholipid synthesis and release of inhibition by thioesterase action. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2814–2821. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2814-2821.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joshi V C, Wakil S J. Studies on the mechanism of fatty acid synthesis. XXVI. Purification and properties of malonyl-coenzyme A-acyl carrier protein transacylase of Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1971;143:493–505. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(71)90234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnuson K, Carey M R, Cronan J E., Jr The putative fabJ gene of Escherichia coli fatty acid synthesis is the fabF gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3593–3595. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3593-3595.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magnuson K, Jackowski S, Rock C O, Cronan J E., Jr Regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:522–542. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.522-542.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnuson K, Oh W, Larson T J, Cronan J E., Jr Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the fabD gene encoding malonyl coenzyme-acyl carrier protein transacylase of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1992;299:262–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morbidoni H R, de Mendoza D, Cronan J E., Jr Bacillus subtilis acyl carrier protein is encoded in a cluster of lipid biosynthesis genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4780–4794. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4794-4800.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Müller J, Oehler S, Müller-Hill B. Repression of lac promoter as a function of distance, phase and quality of an auxiliary lac operator. J Mol Biol. 1996;257:21–29. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Post-Beittenmiller D, Jaworski J G, Ohlrogge J B. In vivo pools of free and acylated acyl carrier proteins in spinach: evidence for sites of regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1858–1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raetz C R H. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides: a remarkable family of bioactive macroampiphiles. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1035–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenfeld I S, D’Agnolo G, Vagelos P R. Synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids and the lesion in fabB mutants. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:2452–2460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roughan G. A semi-preparative enzymic synthesis of malonyl-CoA from [14C]acetate. Biochem J. 1994;300:355–358. doi: 10.1042/bj3000355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serre L, Verbree E C, Dauter Z, Stuitje A R, Derewenda Z S. The Escherichia coli malonyl-CoA:acyl carrier protein transacylase at 1.5-A resolution: crystal structure of a fatty acid synthase component. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12961–12964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siggaard-Andersen M, Wissenbach M, Chuck J A, Svendsen I, Olsen J G, von Wettstein-Knowles P. The fabJ-encoded β-ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase IV from Escherichia coli is sensitive to cerulenin and specific for short-chain substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11027–11031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stüber D, Matile H, Garotta G. System for high level production in Escherichia coli and rapid purification of recombinant proteins: application to epitope mapping, preparation of antibodies, and structure-function analysis. Immunol Methods. 1990;4:121–152. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsay J T, Rock C O, Jackowski S. Overproduction of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase I imparts thiolactomycin resistance to Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:508–513. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.508-513.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsay J T, Oh W, Larson T J, Jackowski S, Rock C O. Isolation and characterization of the β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III gene (fabH) from Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6807–6814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vallari D S, Jackowski S. Biosynthesis and degradation both contribute to the regulation of coenzyme A content in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3961–3966. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.3961-3966.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vallari D S, Jackowski S, Rock C O. Regulation of pantothenate kinase by coenzyme A and its thioesters. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:2468–2471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]