Abstract

Acute gastric volvulus is a surgical emergency that requires urgent intervention to prevent gastric ischemia and necrosis. Gastric volvulus manifests as an abnormal rotation or torsion of the stomach and may be associated with gastric outlet obstruction. This pathology can be classified as either mesentero-axial or organo-axial volvulus, depending on the axis of rotation. Similarly, it can be categorized as primary or secondary, depending on the etiology. We describe a case of a 63-year-old female with a history of peptic ulcer disease who presented with severe epigastric pain and vomiting of one-day duration. She was diagnosed with an acute mesentero-axial gastric volvulus, which was successfully reduced using a nasogastric tube.

Keywords: acute gastric volvulus, mesentero-axial, paraesophageal hernia, gastric outlet obstruction, gastropexy

Introduction

The term gastric volvulus is derived from the Latin term volvere meaning to turn or roll, and is clinically defined as the abnormal rotation or torsion of the stomach.1,2 Gastric volvulus is classified by its axis of rotation: organo-axial (long-axis) and mesentero-axial (short-axis), with mesentero-axial volvulus making up less than a third of the cases. 3 Peak incidence of acute gastric volvulus is seen in two age cohorts: infants and individuals over the age of 50 years.3,4 Acute gastric volvulus is a very rare condition that is only seen in 4% of hiatal hernias. 4 Other less common causes include congenital anatomic defects and traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. 5 Patients often present acutely with epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting, preceded by violent retching. 6 If not detected early, a gastric volvulus may progress to a closed-loop obstruction causing gastric strangulation with ischemia and necrosis; 2 thus a prompt diagnosis is imperative. Herein, we present a very rare case of an acute mesentero-axial gastric volvulus reduced with a nasogastric tube.

Case Report

A 63-year-old female with a medical history of diabetes mellitus and peptic ulcer disease presented to the emergency department complaining of sudden onset epigastric pain of one-day duration. The pain was described as sharp, rated 8/10 in intensity, but non-radiating. The patient stated that she ate rice, shrimp, and pork at a party when she started to feel nauseous. Before visiting the ED, she had multiple episodes of non-bilious and non-bloody emesis. The patient’s epigastric pain worsened with emesis, and there were no alleviating factors. The patient also felt cold and clammy at the time but denied having fever, chills, lip swelling, metallic taste, blurry vision, new bruises, or rashes.

The patient denied seafood allergies or any food sensitivities. She also denied dysphagia, hoarseness, shortness of breath, chest pain, diarrhea, constipation, recent weight loss, melena, hematochezia, or binge drinking. A focused physical examination revealed epigastric tenderness without guarding, rigidity, or rebound tenderness. There was no palpable organomegaly, ecchymosis, or Murphy sign. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

In the ED, the patient appeared distressed due to pain, but her vital signs were within the normal ranges. She was administered famotidine (20 mg), intravenous (IV), ondansetron (4 mg), IV, and Ketorolac (15 mg), IV for symptomatic control. Limited biliary bedside ultrasonography showed no evidence of acute cholecystitis. The complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, and lipase levels were unremarkable. As the patient’s symptoms persisted, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis was ordered, which revealed a paraesophageal hernia and a possible gastric volvulus (Figure 1). An upper gastrointestinal series (XR Upper GI) and kidney, ureter, and bladder (KUB) X-ray (Figure 2) demonstrated a paraesophageal hernia and mesentero-axial volvulus with an obstructed gastric outlet.

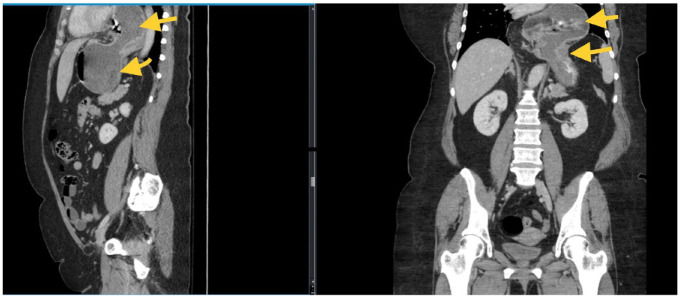

Figure 1.

CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast (Sagittal and coronal views) showing a large hiatal hernia and dilated stomach in left upper quadrant with a large portion in the chest suggestive of a gastric volvulus.

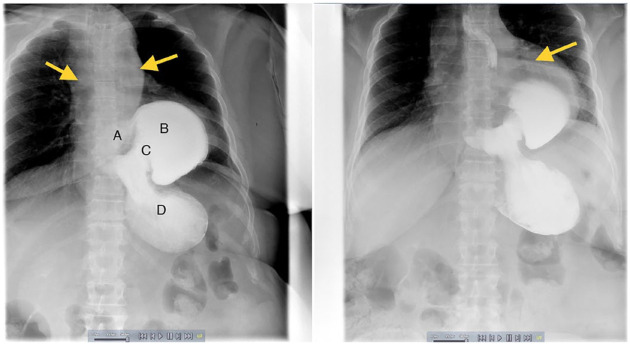

Figure 2.

XR Upper GI series + KUB demonstrating paraesophageal hernia (yellow arrows) and a mesentero-axial volvulus with gastric outlet obstruction. Distal esophagus (A) comes in proximity to the gastric antrum (B) and pylorus (C) which is pathognomonic of this type of volvulus. Gastric body and fundus (D). The stomach is obstructed at the gastric outlet.

Given the patient’s stable condition, a decision was made to defer surgical intervention. The surgical team performed nasogastric tube (NGT) decompression and detorsion. Clear NG drainage (500 mL) occurred over 12 hours, and the patient endorsed flatus the next day. On day 3 of admission, the NGT was removed, and the diet was initiated and advanced as tolerated. A repeat KUB radiograph and contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed a resolution of the gastric volvulus (Figure 3). On day 4, the patient was deemed stable for discharge with plans for follow-up outpatient for elective fundoplication and gastropexy to prevent further volvulus and herniation. The patient remains asymptomatic 3 years after the hospitalization but is not amenable to surgical intervention.

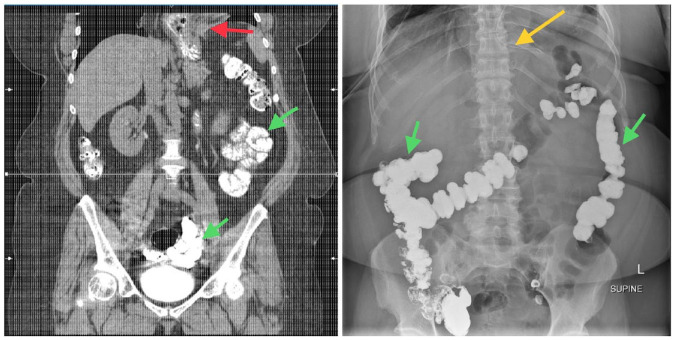

Figure 3.

Repeat CT scan without contrast and KUB x-ray showing the resolution of the gastric volvulus. On both images, contrast can be seen in the small and large bowel from prior contrast study (Green arrows). An NG tube can be seen in the left upper quadrant—stomach (Yellow arrow). A large hiatal hernia is again noted with a significant portion of the stomach located in the chest (Red arrow).

Discussion

First described by Berti in 1886 during an autopsy, gastric volvulus is a rare condition characterized by an abnormal torsion of the stomach.1,3,4,7-9 Gastric volvulus can be acute or chronic, depending on the onset and duration of symptoms. It can also be classified as primary or secondary depending on the cause. In the primary gastric volvulus, defective or loose gastric ligaments are unable to hold the stomach in position, predisposing it to malrotation. Secondary gastric volvulus is caused by esophageal hernias, phrenic nerve palsy, ruptured diaphragm, or congenital defects of the stomach, spleen, or diaphragm.5,7

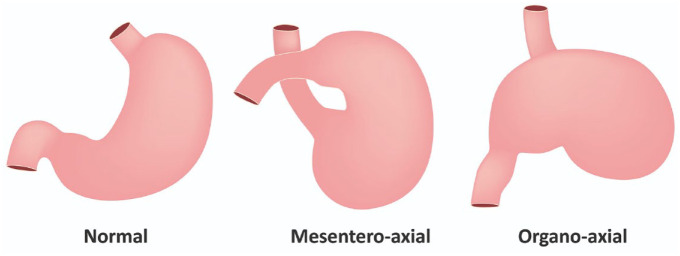

The most common model used to characterize a gastric volvulus involves the axis of rotation, first classified by Von Haberer and Singleton and modified by Carter into three different types. 4 An organo-axial gastric volvulus rotates around the long axis and passes through the cardia and pylorus, where the antrum is rotates antero-superiorly, and the fundus moves postero-inferiorly (Figure 4). 4 Meso-axial rotation occurs along the transverse or short axis, where the antrum is displaced above the gastrojejunal junction (Figure 4), occurring in 30% of the cases. 4 The last subtype is a combination or unclassified volvulus.3,4

Figure 4.

An illustration showing the normal stomach axis and the 2 major types of gastric volvulus.

Seventy-percent of acute gastric volvulus cases demonstrate Borchardt’s triad of epigastric pain, retching with emesis, and the inability to pass a nasogastric tube.1,3,6,8-14 Other symptoms include radiation of the epigastric pain to the back, neck or chest, dysphagia, vomiting, and abdominal distention.5,6 Complications include strangulation leading to ischemia, necrosis, and gangrene along with the risk of perforation, ulceration, and hemorrhage. 3 Due to the rich blood supply of the stomach, strangulation and subsequent ischemia only occurs at a rate of 5% to 28%. 1 Mortality rates for an acute gastric volvulus with ischemic complications are 42% to 56%. 9

A detailed history and physical examination may lead to the suspicion of gastric volvulus; however, a more definitive diagnosis can only be made on imaging. 11 On plain radiographs, signs such as a double air-fluid level or a spherical stomach, as well as the retrocardiac air-fluid level above the diaphragm on the lateral chest film, are indicative of a gastric volvulus.11,15 In addition to chest x-ray, a barium swallow and CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis can aid in the diagnosis and pre-operative planning of gastric volvulus.8,15 Albas et al 8 described 4 CT scan findings predictive of gastric volvulus, including a gastric air-fluid level above the diaphragm, absent-to-decreased distal bowel gas, the reversal of the relative position of the greater curvature of the stomach, and a downward pointing pylorus. Upper GI endoscopy can rule out other acute pathologies including foreign body ingestion and food bolus impaction. Endoscopy may also be used for gastric detorsion in clinically unstable or geriatric patients with malignant arrhythmias.12,16

Typically, a gastric volvulus is treated by stabilizing the patient and repleting their electrolytes. An attempt should be made at decompressing the stomach with a nasogastric tube (NGT). Decompression reduces the tension in the gastric wall, thereby decreasing the risk of ischemia and necrosis. If the NGT cannot be placed at the bedside, the next step entails the placement of the tube via endoscopy. This procedure is known as endoscopic decompression. With this technique, the endoscope is advanced to the gastric lumen, and the contents are suctioned, and the NGT is placed either endoscopically or blindly. Performing endoscopy has the added benefit of mucosal examination. If endoscopy is performed insufflation should be minimized.17,18

Performance of a gastric detorsion by NGT decompression may or may not serve as a bridge to surgery dependent on the response of the patient. Once the patient has had a successful detorsion, the patient may require surgical intervention during the index hospitalization. This can be performed using either an open or laparoscopic approach. For secondary volvulus, the aim would be to repair the anatomic defect that caused the volvulus and, for primary volvulus, the aim would be to perform a gastropexy. Surgery serves to restore the stomach to its normal anatomical position, repairing associated abnormalities, and prevent future episodes of gastric volvulus recurrence. The laparoscopic approach is associated with shorter hospitalization, lower morbidity, better visualization and is less invasive when compared to open surgery.17,19

If an NGT or endoscopic detorsion cannot be easily performed, it may indicate that the patient already has significant ischemia and possible necrosis with a possible perforation. If these findings are suspected, imaging should be performed to confirm the diagnosis. The patient should have a secure airway, be started on broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, and undergo emergent surgery. The surgery undertaken depends on what is viable, including partial gastrectomy, subtotal gastrectomy, and total gastrectomy.12,16

Conclusion

An acute gastric volvulus is described as an anomalous rotation of the stomach due to ligamentous laxity or acquired anatomical defects. This condition can be life threatening and warrants urgent intervention to avoid gastric strangulation with ischemia and gangrene. Because of its high mortality and morbidity rates, acute gastric volvulus must be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute abdomen in infants and older adults.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: LB and MJ conceptualized the idea for this case report. EH, RY, and GM helped with the writing of the manuscript. YC and WB proofread and edited the final manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Our institution does not require IRB approval/waiver for case reports.

Informed Consent: The patient verbally consented to the publication of this case report.

ORCID iD: Lefika Bathobakae  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2772-6085

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2772-6085

Data Availability Statement: Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author

References

- 1. Sevcik WE, Steiner IP. Acute gastric volvulus: case report and review of the literature. Can J Emerg Med. 1999;1(3):200-203. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500004206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zain M, Abada M, Abouheba M, Elrouby A, Ibrahim A. Acute intrathoracic gastric volvulus: a rare delayed presentation of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;70:123-125. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.04.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cavanagh Y, Carlin N, Yuridullah R, Shaikh S. Acute gastric volvulus causing splenic avulsion and hemoperitoneum. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2018;2018:2961063. doi: 10.1155/2018/2961063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kaoukabi A, El MM, Hasbi S, et al. Acute gastric volvulus on hiatal hernia. Case Rep Surg. 2020;2020:1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin YA, Berglind WJ, Cromer R. Acute mesenteroaxial volvulus in the setting of chronic paraesophageal hernia: a case report. Cureus. 2023;15(1):e34124. doi: 10.7759/cureus.34124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hughes M, Huang D, Elbadri S, et al. Acute gastric volvulus in the setting of a paraesophageal hernia with hemoperitoneum: emergency department diagnosis and management. Cureus. 2021;13(12):e20404. doi: 10.7759/cureus.20404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chauhan S, Zackria R, Ryan JK. An unusual case of an acute Mesenteroaxial gastric volvulus secondary to a hiatal hernia. Cureus. 2022;14(11):e31296. doi: 10.7759/cureus.31296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abas MFB, Ko-Ping T, Nurhaziq Bin Harun M, et al. Case report: gastric volvulus–the challenge for early diagnosis. Global Sci J. 2021;9(5):557-561. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jain P, Sanghavi B, Sanghani H, Parelkar SV, Borwankar SS. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia with gastric volvulus. Indian J Surg. 2007;69(6):260-263. doi: 10.1007/s12262-007-0039-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Meshram N, Gadhire M, Kumar V. A case of acute gastric volvulus due to diaphragmatic hernia in an adult with kyphoscoliosis. Int Surg J. 2019;6(5):1809. doi: 10.18203/2349-2902.isj20191916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Germanos S, Gourgiotis S, Saedon M, Lapatsanis D, Salemis NS. Severe abdominal pain as a result of acute gastric volvulus. Int J Emerg Med. 2010;3(1):61-62. doi: 10.1007/s12245-009-0136-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Masjedizadeh AR, Alavinejad P. Endoscopic view in a patient with acute gastric volvulus. Endoscopy. 2015;47(suppl 1 UCTN):E379-E380. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1392501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Padhy AP, Pranay I, Biradar S. An unusual presentation of acute gastric volvulus in the elderly patient: a case report and literature review. Int Surg J. 2020;7(8):2796. doi: 10.18203/2349-2902.isj20203282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hadjittofi C, Matter I, Eyal O, Slijper N. Laparoscopic repair of a late-presenting Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia with acute gastric volvulus. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013008990. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-008990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Al-Faraj D, Al-Haddad M, Al-Hadeedi O, Al-Subaie S. A case of acute mesentero-axial gastric volvulus in a patient with a diaphragmatic hernia: experience with a laparoscopic approach. J Surg Case Rep. 2015;2015(9):rjv119. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjv119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kulkarni K, Nagler J. Emergency endoscopic reduction of a gastric volvulus. Endoscopy. 2007;39(suppl 1):E173. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rashid F, Thangarajah T, Mulvey D, Larvin M, Iftikhar SY. A review article on gastric volvulus: a challenge to diagnosis and management. Int J Surg. 2010;8(1):18-24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chau B, Dufel S. Gastric volvulus. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(6): 446-447. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.041947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morelli U, Bravetti M, Ronca P, et al. Laparoscopic anterior gastropexy for chronic recurrent gastric volvulus: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:244. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]