Abstract

Introduction

The genetic absence epilepsy rat from Strasbourg (GAERS) is a rat model for infantile absence epilepsy with spike-and-wave discharges (SWDs). This study aimed to investigate the potential of alpha 2A agonism to induce seizures during the pre-epileptic period in GAERS rats.

Methods

Stereotaxic surgery was performed on male pups and adult GAERS rats to implant recording electrodes in the frontoparietal cortices (right/left) under anesthesia (PN23–26). Following the recovery period, pup GAERS rats were subjected to electroencephalography (EEG) recordings for 2 h. Before the injections, pup epileptiform activity was examined using baseline EEG data. Dexmedetomidine was acutely administered at 0.6 mg/kg to pup GAERS rats 2–3 days after the surgery and once during the post-natal (PN) days 25–29. Epileptiform activities before injections triggered unilateral SWDs and induced sleep durations, and power spectral density was evaluated based on EEG traces.

Results

The most prominent finding of this study is that unilateral SWD-like activities were induced in 47% of the animals with the intraperitoneal dexmedetomidine injection. The baseline EEGs of pup GAERS rats had no SWDs as expected since they are in the pre-epileptic period but showed low-amplitude non-rhythmic epileptiform activity. There was no difference in the duration of epileptiform activities between the basal EEG groups and DEX-injected unilateral SWD-like-exhibiting and non-SWD-like activities groups; however, the sleep duration of the unilateral SWD-like-exhibiting group was shorter. Power spectrum density (PSD) results revealed that the 1.75-Hz power in the left hemisphere peaks significantly higher than in the right.

Discussion

As anticipated, pup GAERS rats in the pre-epileptic stage showed no SWDs. Nevertheless, they exhibited sporadic epileptiform activities. Specifically, dexmedetomidine induced SWD-like activities solely within the left hemisphere. These observations imply that absence seizures might originate unilaterally in the left cortex due to α2AAR agonism. Additional research is necessary to explore the precise cortical focal point of this activity.

Keywords: GAERS, spike-and-wave discharges, unilateral seizures, α2AAR, pre-epileptic, dexmedetomidine, pups, epileptiform

Introduction

Absence seizures are the most common type of primary generalized epileptic seizures, and they are distinguished by the presence of spike-and-wave discharges (SWDs) in the electroencephalogram (EEG). These discharges are believed to be caused by cortico-thalamocortical mechanisms. Genetic animal models have played a crucial role in elucidating the underlying causes of absence seizures (1).

Idiopathic, non-convulsive, and generalized absence seizures are the three types of seizures (2). The EEG shows bilaterally coordinated and symmetrical SWDs at 3 Hz during absence seizures (3). Gibbs et al. (4) found the association between behavioral unconsciousness and the presence of 3–4 Hz spike-and-slow wave complexes on the EEG in 1935. When depth electrodes were placed into the thalamus of a patient with absence epilepsy, bilateral and synchronous SWDs were seen (5).

In the domain of absence epilepsy research, two commonly used rat models for studying absence epilepsy are the rats of Strasbourg origin [genetic absence epilepsy rat from Strasbourg (GAERS)] and Rijswijk origin (WAG/Rij). The GAERS rats from Strasbourg are a useful model in which behavioral components accompany SWDs, similar to seizures observed in childhood absence epilepsy (6). Absence epileptic seizures do not appear immediately after birth in GAERS rats but emerge after a latent period. These seizures typically arise between 40 and 120 days, with a peak at ~60 days, when the first SWDs appear on the EEG, making GAERS rats an established model for studying absence epilepsy. As the rats aged, the frequency, and length of these discharges increased. We also observed in the EEGs previously that SWDs do not appear in GAERS rats until the 30th day after birth (7). This reflects that the pre-epileptic period, a silent phase of epileptogenesis, is anticipated to unfold (8), and our understanding of this crucial developmental stage is still limited.

The role of alpha 2A adrenergic receptors (α2AAR), a specific subtype of α2AR known to be involved in the generation and sustainability of SWDs, has been extensively investigated (9–12). In rats, a decrease in noradrenergic and dopaminergic activity has been shown to promote the occurrence of absence-like seizures (13). A previous study has shown that activating α2AAR receptors with the antagonist atipamezole efficiently decreased SWDs in adult GAERS rats (14) but activating α2AAR with agonist dexmedetomidine established a model of status epilepticus similar to prolonged absence seizures (15). In this study, dexmedetomidine also induced a state of switch from status to sleep and back from sleep to status (15). These findings help to show them as key players in the involvement of SWDs.

The generation of SWDs has long been debated, with two main theories emerging. Among these, the cortical theory has garnered a larger following. The somatosensory cortex has received much attention in this area and has been established as a key player in SWD generation through numerous studies (16, 17). Bancaud et al. (18) remarkable research on human patients provided direct evidence that initiating a focal discharge in the frontal cortex later propagates to the cortico-cortical pathways.

Further evidence of cortical involvement, particularly in the frontal and parietal regions, comes from EEG/fMRI data of patients with Rolandic epilepsy, where thalamic signals were found to follow cortical signals with higher amplitude (19). These findings are confirmed by neuropathological discoveries that confirm the cortical influence on SWDs. In addition, recent studies address that dexmedetomidine may facilitate seizure expression with peripheral somatosensory stimulation in rats, and interestingly, these seizures are focal initially (20, 21). These studies mention the high-frequency oscillations (ripples and fast ripples) preceded by the induction of these seizures. In this study, we aimed to investigate the SWDs before they were fully expressed in the GAERS model. Specifically, our objective is to determine whether α2AAR stimulation could induce SWD activity. We aimed to understand better the early stages of SWD and the potential role of α2AAR in SWD initiation.

Methods

Animals and experimental groups

The study was performed at Acibadem Mehmet Ali Aydinlar University Medical Experimental Application and Research Center (DEHAM) and was approved by the Acibadem University Experimental Animals Local Ethics Committee under decision number ACUHAYDEK2020/51.

The GAERS rats were bred and housed in a controlled environment in the animal care and production area. The room was set to a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, and the temperature was 24 ± 2°C. The rats had unrestricted access to standard rat chow and drinking water. To preserve the GAERS strain's specific absence of epilepsy characteristics, inbreeding practices were used from the GAERS strain with 7- to 11-Hz spontaneous SWDs (1). The animals were housed in pairs in cages before the surgical procedures. However, after the completion of the stereotaxic surgeries, each cage accommodated only one animal to ensure proper post-surgery care and monitoring.

Male GAERS offspring rats (PN 23–26) obtained from Acibadem University DEHAM, still in their epileptogenesis period and weighed between 25 and 45 g, did not yet express SWDs. The animals were implanted with electrodes on the PN 23-26 and EEGs were performed on the PN 25–29. The offspring rats were connected to the EEG and their postnatal days were between PN23 and PN26, their EEGs were recorded once after 2–3 days after the surgery and once. The SWD expressions were confirmed as none by the 20-min baseline EEG. The waiting period after stereotaxic surgery was a minimum of 2 days.

Stereotaxic surgery

Stereotaxic surgery was performed under ketamine/chlorobutanol (100 mg/kg, VetaKetam; Oruç Özel Vet. Hiz. Hay. Ve Gida San. Tic. LLC.) and xylazine (10 mg/kg; Rompun, 2%; Bayer HealthCare, LLC) anesthesia, both of which were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) to all experimental group rats. The heads of the animals were first placed in the stereotaxy device after the ear bars were fixed in the anterior chamber of the stereotaxy device (Stoelting Model 51600, Stoelting Co., Illinois). Four stainless steel screws with insulated wires were implanted bilaterally to the right and left frontal bones over the cortex rat brain atlas (22) according to the coordinates provided by reference to the bregma point and adapted to the pup animals (right/left frontal; AP: +2.2, ML: ±1.5; parietal AP: −2.9, ML: ±1.5). The opposite ends of the cables, which had previously been attached to pins, were soldered to the tiny connections generated by cutting the male VGA connectors into four threads with multiwire conductor cables using phosphoric acid and a soldering device instrument. Dental acrylic was used to cover and secure the electrodes and cables to the skull. Following the surgery, a 0.9% isotonic sodium chloride solution was injected subcutaneously to supply any possible fluid loss in the animal.

EEG recordings and analysis

After the electrodes were placed by stereotaxic surgery, the animals were allowed to rest for 2 days. The animals' basal activity was then recorded to analyze the epileptiform activities and freezing behaviors. The signals from the electrodes were transferred to ML 136 bioamplifier (ADInstruments) for EEG recording using the EEG recording wire. The amplifier signals were sent to the computer using the Powerlab system (PowerLab8S ADI Instruments, Oxfordshire, UK). The frequency filter is used in the 1- to 40-Hz band. EEG recordings on the computer were analyzed with the LabChart 8.0 program. Epileptiform activity analysis was performed by manually selecting the EEG activity occurring in both cortices of the animals between the basal EEG from groups, DEX injected-unilateral SWD-like-exhibiting and non-SWD-like activities groups over the duration of 1 sec to improve the accuracy of power spectral analysis (below) by increasing sampled length of time. Sleep time was also monitored during the EEG and video recordings.

Dexmedetomidine injections

Following the recording of basal activity, 0.6 mg/kg dexmedetomidine was injected i.p. acutely into the animals. After the injection of dexmedetomidine, the EEG was recorded for two more hours, and a power spectrum density (PSD) analysis was performed.

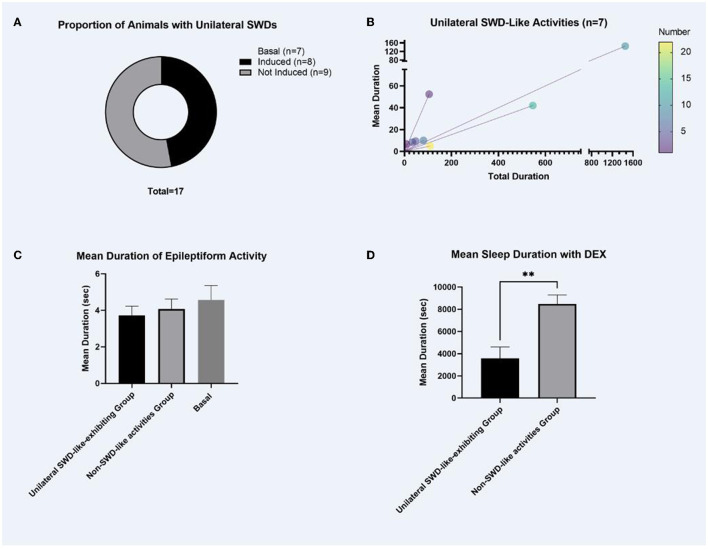

PSD analysis

The SWD and SWD-like EEG data were preprocessed using Fieldtrip (23) and custom MATLAB scripts (R2022a, MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts). SWD activity was obtained and is shown as an example (24). Figure 2 shows the EEG data after bandpass filtering (with zero-phase, third-order, Butterworth filter using bandpass function in MATLAB, between 1 and 40 Hz). Multitaper spectral decomposition was used at 0.25 Hz frequency steps with discrete prolate spheroidal sequences and 1 Hz multitapers. PSD was the amplitude of the time-frequency decomposition calcuated for each frequency.

Figure 2.

Raw recordings and PSD results of SWD and SWD-like activity. The left side of the figure shows the EEG recordings (filtered in 1–40 Hz) of two examples of SWD-like activity developed in the left hemisphere and one example of mature SWD activity recorded previously. Each subsequent two rows belong to the same animal. The right side of the figure shows the PSD results. As shown for the first two animals, SWD-like activity peaks at approximately 1.5–1.75 Hz, but for the third animal, the SWD activity peaks at 6 Hz and is similar on both hemispheres. L, left hemisphere; R, right hemisphere.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism version 9.5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to examine the total, mean duration, and number of SWD-like activities and the percentage of animals in which this activity was triggered (the unilateral SWD-like-exhibiting group). The unpaired Student's t-test was used to compare the mean duration of epileptiform activities and sleep (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01).

Results

Proportion of animals with unilateral SWDs and the total, mean duration, and number of SWD-like activities

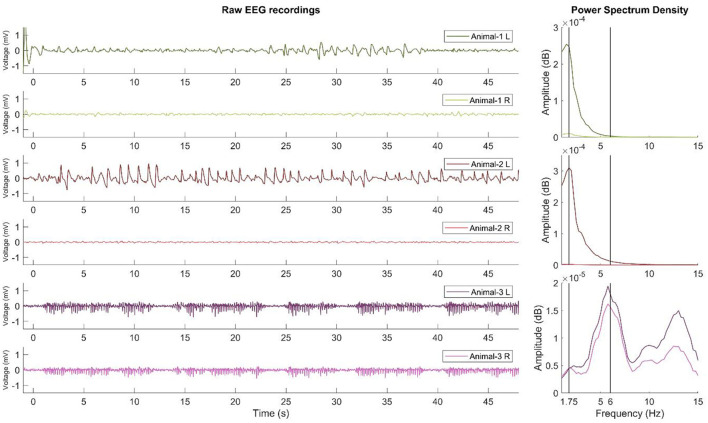

The baseline EEGs of pup GAERS rats did not show SWD as expected but showed low-amplitude non-rhythmic epileptiform activity. A 0.6-mg/kg dexmedetomidine injection generated unilateral SWD-like activity in 47% of the rats (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

The proportion of animals with unilateral SWDs, the total mean duration of SWD-like activities, the mean duration of epileptiform activities, and the sleep duration following dexmedetomidine injections. (A) As expected, the baseline EEGs of pup GAERS rats did not show matured SWDs; it showed low amplitude non-rhythmic epileptiform activity. Mature SWDs occur after post-natal 30 in adult GAERS. Following a 0.6-mg/kg dexmedetomidine injection, unilateral SWD-like activity was observed in 47% (8/17) of the rats, as illustrated in (A). (B) Characteristics of Unilateral SWD-like Activity. Unilateral SWD-like activities were analyzed within the group of animals exhibiting this response shown in (A) (n = 8). (C) Duration of Epileptiform Activities. Comparison of the duration of epileptiform activity between the “unilateral SWD-like-exhibiting group” and the “non-SWD-like activities group” revealed no significant difference in the (C). (D) Sleep Duration Following Dexmedetomidine Injections. In the “unilateral SWD-like-exhibiting group,” the mean sleep duration was significantly shorter compared to the “non-SWD-like activities group.” No sleep activity was observed on the baseline EEG data as expected. The data were given as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01 (significant difference).

The descriptive statistics of unilateral SWD-like activities in the left cortex of animals that were triggered were analyzed (the unilateral SWD-like-exhibiting group). All SWD-like activities between the animals (n = 8) were 297.0 ± 175.3 s up to 3 h. The mean duration of each SWD-like activity among animals exhibiting unilateral SWD-like activities was 34.9 ± 16.9 s. The number of each SWD-like activity between the animals was 8.3 ± 2.4 (Figure 1B).

Mean duration of epileptiform activities and the sleep duration following dexmedetomidine injections

There was no significant difference in the length of epileptiform activity between “the unilateral SWD-like-exhibiting group” and “the non-SWD-like activities group” (Figure 1C). However, in the unilateral SWD-like-exhibiting group, mean sleep duration was considerably shorter than the non-SWD-like activities group (t(df) = 3.812, p = 0.003, p < 0.01, Figure 1D).

PSD analysis of SWD-like activity

As shown in Figure 2, SWD-like activity is qualitatively similar to mature SWD activity, which classically indicates 6-Hz activity. However, SWD-like activity appears slower and peaks at 1.5–1.75 Hz. This activity developed only in the left hemispheres of 47% of the animals injected with the 0.6 mg/kg dexmedetomidine. Furthermore, the PSD results revealed that the 1.75 Hz power in the left hemisphere peaks significantly higher than that of the right hemisphere.

Discussion

Generalized SWDs are known to be the basic building blocks of the EEG of absence epilepsy when manifested bilaterally and synchronously (25). Several genetic and pharmacological animal models have been constructed to understand the fundamental etiological factors behind epilepsies better and identify potential therapeutic targets for anti-epileptic medicines (26). GAERS, as an absence epilepsy model, provides a valuable model to examine the underlying epileptogenesis process in the pre-epileptic stage of the first 30 days of life in this animal model. This process is important for investigating potential anti-epileptogenic and anti-seizure treatment approaches and their use in creating new animal models.

Spike-and-wave discharges are high amplitude, synchronous, and, most significantly, bilateral. Previous studies were performed with unilateral cortical resection, but no change was reported. In contrast, SWDs were no longer noticeable after bilateral resection. These results suggest that SWDs are completely abolished after bilateral removal of the focal region, most likely by interfering with an intracortical columnar circuit (27), which also supports the cortical focus, whereas only inhibition of the local cortical network removed all seizures. Another unilateral onset is that SWDs have induced fluid percussion injury in rats, and it serves as a model for complex partial seizures in human post-traumatic epilepsy (28). In this model, anti-absence ethosuximide has been shown to suppress both unilateral or bilateral SWDs, whereas carbamazepine had no effect (28). Some drugs, such as potassium chloride, block SWDs somewhat in the ipsilateral cortex and thalamus (29). Furthermore, bilateral or unilateral SWDs have been observed to alternate between hemispheres after corpus callosum excision, implying that the corpus callosum is related to SWD generalization (30). Landau–Kleffner syndrome, commonly known as electrical status epilepticus of sleep, has focal SWDs (31). However, no report has shown unilateral induction of SWD-like activities with pharmacological or chemical agents.

In addition to the induction of unilateral seizures with dexmedetomidine, this study questions the focal origin hypothesis of absence seizures, specifically SWDs. Despite the absence of SWD activity observed in the baseline EEG of the pup GAERS, which is expected to be in their epileptogenesis period (before PN30), a dose of 0.6 mg/kg dexmedetomidine selectively induced unilateral SWD-like events in the left cortex of half of the animals. Animals that exhibited unilateral SWD-like activities accounted for 47% of the total sample. Unilateral expression of normally generalized seizures suggests a focal start. Some studies with dexmedetomidine also induced focal seizures suggest the activation of α2AAR may start the SWDs. In addition to these results, dexmedetomidine-inducing focal seizures in a periphery reflex model (20, 21) draw attention to α2AAR-mediated seizure initiation mechanisms.

Dexmedetomidine closely resembles and facilitates natural non-REM sleep (32) and therefore improves sleep in patients receiving dexmedetomidine anesthesia in comparison to other anesthetics after surgery by altering sleep structure (33, 34). Dexmedetomidine also modulates the release of inhibitory compounds such as γ-aminobutyric acid and galanin due to reduced control over the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus, further inhibiting the locus ceruleus and tuberomamillary nucleus by the inhibition and disinhibition of the locus ceruleus and ventral lateral preoptic nucleus (35). The α2AAR agonist effect of dexmedetomidine on NREM sleep might be influenced by postsynaptic α2AAR (36). Meanwhile, changes in high-frequency oscillations in the thalamus and neocortex have also been observed during dexmedetomidine anesthesia (37). In a genetic model of absence epilepsy, alterations in sleep characteristics were identified in WAG/Rij rats encompassing extended transitions from wakefulness to sleep, prolonged intermediate sleep stages, more frequent subsequent arousals, and a reduced proportion of REM sleep (38–40). That also points out the positive relationship between absence seizures and the increase of NREM activity as it is already known both rhythms of SWDs and NREM activities are synchronized in the thalamocortical circuitry (41, 42). The focal point pertains to the plausible role of dexmedetomidine in potentially inducing the transition of slow wave and delta oscillations, thereby precipitating SWDs.

A recent study on the mesoscale modeling of SWDs highlights and sheds light on the initiation, maintenance, and termination of SWDs by integrating pyramidal cells (43) and interneurons in the cortex (44, 45) as well as the ventroposterior medial nucleus of the thalamus, reticular thalamic nucleus (RTN), and nervus trigeminus (46). In this model, SWD might be initiated by one of the three mechanisms: an increase in intracortical excitability, external driving from the nervus trigeminus to the thalamic ventroposterior medial nucleus, or low-frequency harmonic stimulation of the cortex. While the maintenance was caused by increased coupling from RTN nodes to both pyramidal nodes and cortical interneurons (46), the termination was driven by increased coupling from rostral RTN to the brain or high-frequency electrical stimulation. We first demonstrated that SWD-like activity might be induced unilaterally using the α2AAR agonist dexmedetomidine. Though it appears to be the start of SWD-like activity in the left cortex, our previous study with a status epilepticus model found that dexmedetomidine generated sustained SWDs in adult rats, which is more consistent with the maintenance of SWD activity.

Our previous study (15) introduced this absence status epilepticus model with the induction of dexmedetomidine in adult GAERS. Recent reports on dexmedetomidine increasing the duration of SWD activity (15) provide evidence that dexmedetomidine influences SWD duration. For instance, Sitnikova et al. (47, 48) provided preliminary results of dexmedetomidine increasing mean duration of SWDs in another model of genetic absence epilepsy Wistar Albino Glaxo/Rijswijk (WAG/Rij), and dexmedetomidine does not shorten the SWDs unlike other anesthetics (49).

The mean sleep duration differed significantly between animals that exhibited unilateral SWD-like activities or not in this study as well. This difference can potentially be attributed to two distinct factors. First, anesthesia-induced sleep may interfere with the initiation of unilateral activities. Because our EEG recordings were obtained 2 h after injection, some animals may not fully emerge from the anesthesia during this timeframe. Second, given the metabolic differences among the animals, mainly as they are still in the pup stage, it is conceivable that the dosage of dexmedetomidine administered may have exceeded the specific activation threshold of α2AAR. These factors may have contributed to the observed difference in sleep duration between the animals.

Another issue on dexmedetomidine as addressed by many studies is the possible induction of respiratory or cardiovascular system-related adverse effects. Recent studies point out a either positive influence or no influence on the respiratory parameters (50–53). Conversely, a significant reduction in heart rate and instances of bradycardia have been reported as some of the cardiovascular effects (51). Yet, the relationship between them is yet to be investigated in terms of the sleep and SWD-related mechanisms.

As a result, it remains unclear whether the induction of unilateral SWD-like events reflects the initiation or maintenance phase of SWDs. In any case, α2AAR appears to be a strong candidate for further investigation as the primary mechanism behind the initiation or maintenance of SWDs as well as the modulation of switch mechanisms between sleep and SWDs. Further research into the exact cortical process and the role of α2AAR would be valuable.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Acibadem University Experimental Animals Local Ethics Committee under decision number ACUHAYDEK2020/51. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MY and FO conceptualized and designed the study. MY organized the database, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SA performed the analysis and wrote the Results section of the PSD section of the manuscript. Pİ, NM, GD, ÖŞ, SK, and EK contributed to the EEG data acquisition. MY and FO contributed to the manuscript's revision and read and approved the submitted version. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The study was funded by the ABAPKO (Grant 2022/02-20) and Europe Commission [GEMSTONE Horizon Europe grant number 101078981].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Marescaux C, Vergnes M, Depaulis A. Genetic absence epilepsy in rats from strasbourg–a review. J Neural Transm Suppl. (1992) 35:37–69. 10.1007/978-3-7091-9206-1_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panayiotopoulos CP, Chroni E, Daskalopoulos C, Baker A, Rowlinson S, Walsh P. Typical absence seizures in adults: clinical, EEG, video-EEG findings and diagnostic/syndromic considerations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1992) 55:1002–8. 10.1136/jnnp.55.11.1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumenfeld H. Consciousness and epilepsy: why are patients with absence seizures absent? Prog Brain Res. (2005) 150:271–86. 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)50020-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibbs FA, Davis H, Lennox WG. The electro-encephalogram in epilepsy and in conditions of impaired consciousness. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. (1935) 34:1133–48. 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1935.02250240002001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams D. A study of thalamic and cortical rhythms in petit mal. Brain. (1953) 76:50–69. 10.1093/brain/76.1.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danober L, Deransart C, Depaulis A, Vergnes M, Marescaux C. Pathophysiological mechanisms of genetic absence epilepsy in the rat. Prog Neurobiol. (1998) 55:27–57. 10.1016/S0301-0082(97)00091-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yavuz M, Albayrak N, Özgür M, Gülçebi Idriz Oglu M, Çavdar S, Onat F. The effect of prenatal and postnatal caffeine exposure on pentylentetrazole induced seizures in the non-epileptic and epileptic offsprings. Neurosci Lett. (2019) 713:134504. 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komoltsev IG, Frankevich SO, Shirobokova NI, Volkova AA, Levshina IP, Novikova MR, et al. Differential early effects of traumatic brain injury on spike-wave discharges in Sprague-Dawley rats. Neurosci Res. (2021) 166:42–54. 10.1016/j.neures.2020.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King GA, Burnham WM. Alpha 2-adrenergic antagonists suppress epileptiform EEG activity in a petit mal seizure model. Life Sci. (1982) 30:293–8. 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90511-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCallum JB, Boban N, Hogan Q, Schmeling WT, Kampine JP, Bosnjak ZJ. The mechanism of alpha2-adrenergic inhibition of sympathetic ganglionic transmission. Anesth Analg. (1998) 87:503–10. 10.1213/00000539-199809000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sitnikova E, van Luijtelaar G. Reduction of adrenergic neurotransmission with clonidine aggravates spike-wave seizures and alters activity in the cortex and the thalamus in WAG/Rij rats. Brain Res Bull. (2005) 64:533–40. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Micheletti G, Warter JM, Marescaux C, Depaulis A, Tranchant C, Rumbach L, et al. Effects of drugs affecting noradrenergic neurotransmission in rats with spontaneous petit mal-like seizures. Eur J Pharmacol. (1987) 135:397–402. 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90690-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vergnes M, Marescaux C, Depaulis A, Micheletti G, Warter JM. Ontogeny of spontaneous petit mal-like seizures in Wistar rats. Brain Res. (1986) 395:85–7. 10.1016/S0006-8993(86)80011-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yavuz M, Aydin B, Carcak N, Akman O, Raci Yananli H, Onat F. Atipamezole, a specific alpha2A antagonist, suppresses spike-and-wave discharges and alters Ca(2(+))/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the thalamus of genetic absence epilepsy rats. Epilepsia. (2020) 61:2825–35. 10.1111/epi.16728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yavuz M, Akkol S, Onat F. Alpha-2a adrenergic receptor (α2AR) activation in genetic absence epilepsy: an absence status model? Authorea. (2022). 10.22541/au.167042890.02021046/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meeren HKM, Pijn JPM, van Luijtelaar ELJM, Coenen AML, Lopes da Silva FH. Cortical focus drives widespread corticothalamic networks during spontaneous absence seizures in rats. J Neurosci. (2002) 22:1480–95. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01480.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meeren H, van Luijtelaar G, Lopes da Silva F, Coenen A. Evolving concepts on the pathophysiology of absence seizures: the cortical focus theory. Arch Neurol. (2005) 62:371–6. 10.1001/archneur.62.3.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bancaud J, Talairach J, Morel P, Bresson M, Bonis A, Geier S, et al. “Generalized” epileptic seizures elicited by electrical stimulation of the frontal lobe in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. (1974) 37:275–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szaflarski JP, DiFrancesco M, Hirschauer T, Banks C, Privitera MD, Gotman J, et al. Cortical and subcortical contributions to absence seizure onset examined with EEG/fMRI. Epilepsy Behav. (2010) 18:404–13. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bortel A, Yao ZS, Shmuel A. A rat model of somatosensory-evoked reflex seizures induced by peripheral stimulation. Epilepsy Res. (2019) 157:106209. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2019.106209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bortel A, Pilgram R, Yao ZS, Shmuel A. Dexmedetomidine - commonly used in functional imaging studies - increases susceptibility to seizures in rats but not in wild type mice. Front Neurosci. (2020) 14:832. 10.3389/fnins.2020.00832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates–The New Coronal Set, 5th Edn. Burlington, NJ: Elsevier Academic Press; (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oostenveld R, Fries P, Maris E, Schoffelen JM. FieldTrip: open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Comput Intell Neurosci. (2011) 2011:156869. 10.1155/2011/156869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Abbott SBG, Depuy SD, Kanbar R. The retrotrapezoid nucleus and breathing. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2012) 758:115–22. 10.1007/978-94-007-4584-1_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antwi P, Atac E, Ryu JH, Arencibia CA, Tomatsu S, Saleem N, et al. Driving status of patients with generalized spike-wave on EEG but no clinical seizures. Epilepsy Behav. (2019) 92:5–13. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.11.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cortez MA, Kostopoulos GK, Snead OC 3rd. Acute and chronic pharmacological models of generalized absence seizures. J Neurosci Methods. (2016) 260:175–84. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scicchitano F, van Rijn CM, van Luijtelaar G. Unilateral and bilateral cortical resection: effects on spike-wave discharges in a genetic absence epilepsy model. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0133594. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tatum S, Smith ZZ, Taylor JA, Poulsen DJ, Dudek FE, Barth DS. Sensitivity of unilateral- versus bilateral-onset spike-wave discharges to ethosuximide and carbamazepine in the fluid percussion injury rat model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurophysiol. (2021) 125:2166–77. 10.1152/jn.00098.2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vergnes M, Marescaux C. Cortical and thalamic lesions in rats with genetic absence epilepsy. J Neural Transm Suppl. (1992) 35:71–83. 10.1007/978-3-7091-9206-1_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vergnes M, Marescaux C, Lannes B, Depaulis A, Micheletti G, Warter JM. Interhemispheric desynchronization of spontaneous spike-wave discharges by corpus callosum transection in rats with petit mal-like epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. (1989) 4:8–13. 10.1016/0920-1211(89)90052-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McVicar KA, Shinnar S. Landau-Kleffner syndrome, electrical status epilepticus in slow wave sleep, and language regression in children. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. (2004) 10:144–9. 10.1002/mrdd.20028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng ZX, Dong H, Qu WM, Zhang W. Oral delivered dexmedetomidine promotes and consolidates non-rapid eye movement sleep via sleep-wake regulation systems in mice. Front Pharmacol. (2018) 9:1196. 10.3389/fphar.2018.01196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang X, Lin D, Sun Y, Wu A, Wei C. Effect of dexmedetomidine on postoperative sleep quality: a systematic review. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2021) 15:2161–70. 10.2147/DDDT.S304162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song B, Li Y, Teng X, Li X, Yang Y, Zhu J. The effect of intraoperative use of dexmedetomidine during the daytime operation vs the nighttime operation on postoperative sleep quality and pain under general anesthesia. Nat Sci Sleep. (2019) 11:207–15. 10.2147/NSS.S225041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng J, Wu F, Zhang M, Ding D, Fan S, Chen G, et al. The interaction between the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus and the tuberomammillary nucleus in regulating the sleep-wakefulness cycle. Front Neurosci. (2020) 14:615854. 10.3389/fnins.2020.615854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seidel WF, Maze M, Dement WC, Edgar DM. Alpha-2 adrenergic modulation of sleep: time-of-day-dependent pharmacodynamic profiles of dexmedetomidine and clonidine in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (1995) 275:263–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baker R, Gent TC, Yang Q, Parker S, Vyssotski AL, Wisden W, et al. Altered activity in the central medial thalamus precedes changes in the neocortex during transitions into both sleep and propofol anesthesia. J Neurosci. (2014) 34:13326–35. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1519-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gandolfo G, Romettino S, Gottesmann C, Van Luijtelaar G, Coenen A. Genetically epileptic rats show a pronounced intermediate stage of sleep. Physiol Behav. (1990) 47:213–5. 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90063-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coenen AM, Van Luijtelaar EL. Genetic animal models for absence epilepsy: a review of the WAG/Rij strain of rats. Behav Genet. (2003) 33:635–55. 10.1023/A:1026179013847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Luijtelaar G, Bikbaev A. Midfrequency cortico-thalamic oscillations and the sleep cycle: genetic, time of day and age effects. Epilepsy Res. (2007) 73:259–65. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huguenard JR, McCormick DA. Thalamic synchrony and dynamic regulation of global forebrain oscillations. Trends Neurosci. (2007) 30:350–6. 10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crunelli V, Leresche N. Childhood absence epilepsy: genes, channels, neurons and networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2002) 3:371–82. 10.1038/nrn811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Luijtelaar G, Sitnikova E. Global and focal aspects of absence epilepsy: the contribution of genetic models. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2006) 30:983–1003. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Polack P-O, Guillemain I, Hu E, Deransart C, Depaulis A, Charpier S. Deep layer somatosensory cortical neurons initiate spike-and-wave discharges in a genetic model of absence seizures. J Neurosci. (2007) 27:6590–9. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0753-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abbasova KR, Chepurnov SA, Chepurnova NE, van Luijtelaar G. The role of perioral afferentation in the occurrenceof spike-wave discharges in the WAG/Rij modelof absence epilepsy. Brain Res. (2010) 1366:257–62. 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Medvedeva TM, Sysoeva MV, Lüttjohann A, van Luijtelaar G, Sysoev IV. Dynamical mesoscale model of absence seizures in genetic models. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0239125. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sitnikova E, Pupikina M, Rutskova E. Alpha2 adrenergic modulation of spike-wave epilepsy: experimental study of pro-epileptic and sedative effects of dexmedetomidine. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:9445. 10.3390/ijms24119445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sitnikova E, Rutskova E, Smirnov K. Alpha2-adrenergic receptors as a pharmacological target for spike-wave epilepsy. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:1477. 10.3390/ijms24021477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Gailani L, Al-Kaleel A, Arslan G, Ayyildiz M, Agar E. The effect of general anesthetics on genetic absence epilepsy in WAG/Rij rats. Neurol Res. (2022) 44:995–1005. 10.1080/01616412.2022.2095706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hell J, Venn RM, Cusack R, Rhodes A, Grounds RM. Respiratory effects of dexmedetomidine in the ICU. Critical Care. (2000) 4:P193. 10.1186/cc913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boff GA, de Lima CM, Nobre MO, Gehrcke MI. Hemodynamic and respiratory changes from a continuous infusion of dexmedetomidine in general anesthesia in dogs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Soc Dev. (2022) 11:e39611729980. 10.33448/rsd-v11i7.29980 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carollo DS, Nossaman BD, Ramadhyani U. Dexmedetomidine: a review of clinical applications. Curr Opin Anesthesiol. (2008) 21:457–61. 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328305e3ef [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Venn RM, Hell J, Grounds RM. Respiratory effects of dexmedetomidine in the surgical patient requiring intensive care. Crit Care. (2000) 4:302–8. 10.1186/cc712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.