Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

An association between functional dyspepsia (FD) and wheat-containing foods has been reported in observational studies; however, an adaptive response has not been demonstrated. We examined whether antigens present in wheat could provoke a response from FD duodenal lymphocytes.

METHODS:

Lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMCs) were isolated from duodenal biopsies from 50 patients with FD and 23 controls. LPMCs were exposed to gluten (0.2 mg/mL) or gliadin (0.2 mg/mL) for 24 hours. Flow cytometry was performed to phenotype lymphocytes. Quantitative PCR was used to measure the expression of gliadin-associated T-cell receptor alpha variant (TRAV)26-2.

RESULTS:

In response to gliadin (but not gluten) stimulation, the effector Th2-like population was increased in FD LPMCs compared with that in controls and unstimulated FD LPMCs. Duodenal gene expression of TRAV26-2 was decreased in patients with FD compared with that in controls. We identified a positive association between gene expression of this T-cell receptor variant and LPMC effector Th17-like cell populations in patients with FD, but not controls after exposure to gluten, but not gliadin.

DISCUSSION:

Our findings suggest that gliadin exposure provokes a duodenal effector Th2-like response in patients with FD, supporting the notion that food antigens drive responses in some patients. Furthermore, these findings suggest that altered lymphocyte responses to wheat proteins play a role in FD pathogenesis.

KEYWORDS: functional dyspepsia, T cells, gluten sensitivity, gliadin, immune response

INTRODUCTION

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a disorder of gut-brain interaction (DGBI) characterized by relapsing and remitting gastroduodenal symptoms, in the absence of identifiable pathology through routine clinical screening (1). While the mechanisms remain unclear, meal-associated exacerbation would suggest food components are involved (2). Wheat and gluten have been reported as triggers for symptom onset in FD (3–5). In an Australian population study, 45% of respondents reporting wheat sensitivity (WS) met the Rome criteria for FD and/or the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (6), while an Italian study found approximately 16% of patients with food challenge–confirmed WS also had FD (7). This indicates an association between FD and immune responses to wheat. While there is poor agreement between self-reported WS response and double-blind, placebo-controlled challenge with gluten (8); this may be because the immune response is directed against nongluten components of wheat (e.g., fructans) (9).

Immune and physiological similarities including duodenal eosinophilia (10–13) and increased intestinal permeability (14–17) have been reported in FD and nonceliac gluten/wheat sensitivity (NCG/WS). These similarities may arise from a common immune response to wheat antigens. Antigen recognition requires the interaction of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins on antigen-presenting cells with T-cell receptors (TCRs) on lymphocytes. Specific variants in MHC genes increase the risk of celiac disease (18), wheat allergy (19), and NCG/WS (20), but this is underexplored in FD. While TCR diversity is paramount for the recognition of a broad range of antigens (21), specific variants have been implicated in the response to gliadin in patients with celiac disease (22). TRAV26-2 is 1 variant that has been associated with biased gliadin processing (23), but the impact of TCR variants on the response to wheat in the absence of celiac-permissive MHC variants is unknown. Our recent work has demonstrated that patients with DGBI reporting WS have a higher proportion of circulating gut-homing T cells, compared with non-WS patients and controls (24). In this study, we collected duodenal biopsies to determine whether mucosal cells from patients with FD respond to stimulation with gluten or gliadin proteins ex vivo. We then aimed to examine whether this response was associated with TRAV26-2 expression to better understand mechanisms underlying immune responses in FD.

METHODS

Cohort recruitment

Research undertaken was approved by Hunter New England (reference 13/12/11/3.01) and Metro South Health (reference HREC/13/QPAH/690) Human Research Ethics Committees. Written informed consent was received before participation. Participants (aged 18–80 years) were recruited from outpatient gastroenterology clinics at John Hunter, Gosford and Wyong Hospitals in New South Wales, and Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, as part of a larger study investigating immune activation in FD (25). Controls were requiring endoscopy but asymptomatic for FD-associated symptoms. Exclusion criteria for all participants included a body mass index > 40 kg/m2, celiac disease (as per clinical workup histology, with/without serology), inflammatory gastrointestinal conditions, and pregnancy. Self-reported wheat sensitivity and demographic information were captured by interview. A validated outpatient questionnaire incorporated the modified Nepean Dyspepsia Index (26) and Rome III questionnaire (27). Biopsies from the second duodenal portion (D2) were collected.

Gene expression analysis

Complementary DNA was generated from biopsy-isolated mRNA using iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix for quantitative PCR (qPCR; Bio-Rad). Primers for TRAV26-2 and B-actin (see Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16) were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Skokie). qPCR was performed with iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on a QuantStudio6 Flex Real-Time system (Applied Biosystems). Computed tomography values were normalized to B-actin with relative expression calculated using the 2−ΔCt method.

Isolation of lamina propria mononuclear cells from biopsies

Lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMCs) were freshly isolated from 5 pooled biopsies as previously described (25). In brief, epithelium was dissociated (5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-1-ethane-sulfonic acid [HEPES] in HBSS) and discarded. Biopsies were transferred into a collagenase digestion buffer (1× HBSS, 2% foetal calf serum [FCS], 0.5 mg/mL of collagenase D, 10ug/mL of DNAse II) and underwent 2 rounds of mechanical dissociation and straining to isolate LPMCs. Cells were stored in liquid nitrogen until use.

Stimulation of LPMCs with wheat proteins

Thawed LPMCs were resuspended at 1.0–1.5 × 104 cells/well in complete Roswell Park Memorial Institute [RPMI]-1640 media and then rested at 37°C/5% CO2 overnight. ImmunoCult human CD3/CD28 T-cell activator (Stemcell Technologies) was added to samples, as per manufacturer's instructions. Samples were stimulated in duplicates with 0.2 mg/mL of gluten or gliadin (Sigma-Aldrich) or media and incubated (37°C/5% CO2) overnight.

Surface marker staining of LPMCs for flow cytometry

Supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C, while LPMC duplicate samples were combined and incubated with fixable viability dye and Fc block. Cells were stained (4°C/30 minutes) with fluorescent-conjugated antibodies (see Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16). Samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and data acquired on an LSRFortessaX20 cytometer with FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) set to record 20,000 events. Data were analyzed using FlowJo v.10 (BD Biosciences), and CD3+ populations were identified (see Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16). Given lack of overt inflammation in FD and very low LPMC yields from pinch biopsies, gating was performed on patient control samples and surface marker staining was used over intracellular cytokine staining to improve the accuracy of lymphocyte subset identification (28,29). A minimum of 15,000 events was required for the sample to be included in analysis, and cells were analyzed as a percentage of the appropriate parent population to account for this. Using this approach, exclusion of samples with low event numbers resulted in n = 49 for media, n = 50 for gluten, and n = 47 for gliadin stimulation.

Cytometric bead array for cytokines

The Human Th1/Th2/Th17 cytometric bead array kit (BD Biosciences) was used to quantify cytokines in stimulated LPMC supernatants, as per manufacturer's instructions, and data were acquired on an LSRFortessaX20 flow cytometer with FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FCAP array version 3.0 software (BD Biosciences). Cytokine concentrations were normalized to total cell number.

Statistical analysis

Data sets were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.2 (GraphPad Software Inc). Data were visually presented as mean ± SEM and statistics reported as mean ± SD, with P < 0.05 considered significant. Cohort characteristics were analyzed by t tests. The Fisher exact test was used to analyze effects of potential confounders. The Grubb outlier test was performed to identify any significant outliers, and normality was assessed using the D'Agostino-Pearson test. Comparisons between groups were analyzed by t tests or 1-way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test for normally distributed data. Non-normally distributed data were analyzed by Mann-Whitney t tests or Kruskal-Wallis test with uncorrected Dunn test as appropriate. The Spearman rs was used to examine the strength and direction of relationships between variables. The contrasts between experimental conditions reported in this study are not all statistically independent; hence, the P values reported are considered exploratory and are therefore in need of replication.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the cohort

Fifty patients with FD and 23 controls were included (Table 1). Of the 69 potential patients with FD who were initially screened as willing and suitable to participate in the study, 19 were excluded based on endoscopic/histological findings. A total of 59 possible controls were also screened; however, 36 were identified as having organic disease or other exclusionary findings. Within the FD cohort, 24 had postprandial distress syndrome, 6 had epigastric pain syndrome, and 20 reported prandial distress syndrome/EPS overlap. Controls without FD symptoms consisted of 5 participants with iron deficiency anemia, 10 with positive fecal occult blood tests, 5 with reflux symptoms, and 3 with dysphagia. WS was self-reported by 34.8% controls, compared with 35.6% patients with FD (P > 0.99). Duodenal complementary DNA was available for 15 controls and 36 patients with FD. As previously published, the duodenal eosinophil counts for this cohort were increased in FD (3.39 ± 1.61 vs 4.59 ± 2.45, P = 0.048) (25). No controls were on a gluten-free diet; however, 3/15 (20%) of controls reported reducing their gluten intake at endoscopy. 4/40 (10%) patients with FD were on a gluten-free diet and 14/40 (35%) reported reduced gluten intake at endoscopy. However, some participants declined to answer these questions, and specific dietary intake data were not captured in this study. Participants were not required to alter their wheat intake before endoscopy.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics

| Controls | FD | P value | |

| n = 23 | n = 50 | ||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 52.09 ± 13.12 | 46.84 ± 16.80 | 0.15 |

| Female (%) | 11 (47.83) | 38 (77.55) | 0.03* |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 28.99 ± 5.325 | 25.92 ± 4.136 | 0.01* |

| PPI use (%)a | 5 (23.81) | 19 (44.19) | 0.17 |

| H2RA use (%)a | 0 (0.00) | 2 (4.65) | >0.99 |

| NSAID use (%)a | 1 (4.76) | 2 (4.65) | >0.99 |

| Helicobacter pylori positive (%)a | 2 (11.11) | 2 (4.76) | 0.58 |

| IBS comorbidity (%)a | 1 (4.35) | 15 (30.00) | 0.01* |

| Self-reported wheat sensitivity (%)a | 8 (34.78) | 16 (35.56) | >0.99 |

BMI, body mass index; FD, functional dyspepsia; H2RA, H2 receptor antagonist; LPMC, lamina propria mononuclear cells; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

A factor that was not provided by all participants included in this cohort.

* = p < 0.05.

Alterations in total T-cell populations after gluten and gliadin exposure

We examined duodenal LPMC populations after stimulation with gluten or gliadin by flow cytometry to determine whether wheat proteins provoke differential responses in patients with FD compared with that in controls (see Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16). There were no changes in proportions of CD3+ cells among viable LPMCs on stimulation. FD-derived CD4+ cells stimulated with gliadin were increased compared with those stimulated with gluten (26.42 ± 11.86 vs 34.21 ± 15.75, P = 0.008) but neither increased over media. FD-derived CD8+ cell proportions were decreased with gluten stimulation compared with those over media (18.18 ± 10.73 vs 14.02 ± 10.73, P = 0.017) and those stimulated with gliadin (18.76 ± 11.75, P = 0.015) (see Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16). We investigated whether LPMCs exhibit a specific cytokine secretion profile in response to stimulation by measuring IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor, IL-17A, and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) in the supernatant of gluten-stimulated and gliadin-stimulated LPMCs. We found no significant cytokine response in supernatants from FD LPMCs at 24 hours after exposure to gluten or gliadin (see Supplementary Figure 3, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16).

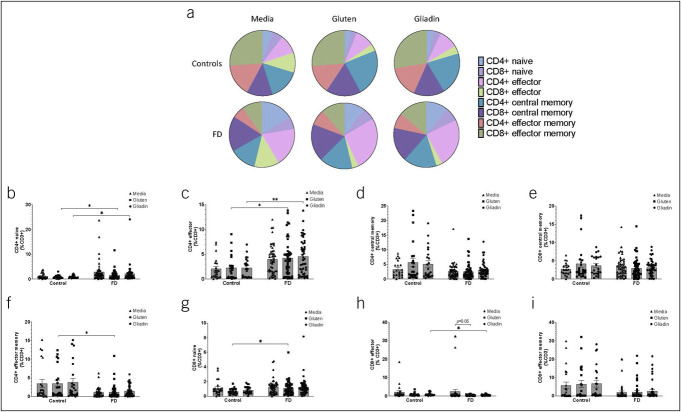

We next examined FD-derived effector (CD45RA+CCR7−) and memory (CD45RO+CCR7+/−) T cells after stimulation. While we observed shifts in the balance of these populations between controls and FD, these were independent of stimulation (Figure 1a). Both the CD4+ naïve and effector populations were increased in FD after gluten (0.84 ± 0.65 vs 1.65 ± 1.82, P = 0.037; 2.29 ± 2.46 vs 4.25 ± 3.61, P = 0.18) and gliadin (0.90 ± 0.54 vs 2.09 ± 3.52, P = 0.015; 2.27 ± 1.97 vs 4.54 ± 3.54, P = 0.001) exposure (Figure 1b,c). The CD4+ (Figure 1d) and CD8+ (Figure 1e) central memory populations were unchanged. However, the proportion of FD-derived CD4+ effector memory cells was decreased compared with those in controls (3.51 ± 4.17 vs 1.24 ± 1.85, P = 0.015) (Figure 1f), while CD8+ naïve T cells were increased (0.66 ± 0.40 vs 0.98 ± 0.67, P = 0.014) (Figure 1g) with gluten. Gliadin resulted in decreased proportions of CD8+ effector (0.98 ± 0.80 vs 0.57 ± 0.35, P = 0.046) (Figure 1h), but CD8+ effector memory cells were unchanged (Figure 1i).

Figure 1.

Mucosal effector and memory lymphocyte populations in controls and patients with FD after stimulation with gluten and gliadin. Isolated lamina propria lymphocytes from controls and patients with FD were analyzed by flow cytometry, and (a) the balance of effector and memory populations was compared between patients with FD and controls across all conditions: Media (negative control), gluten, and gliadin. The proportions of (b) CD4+ naïve (CD45RA+CCR7+), (c) CD4+ effector (CD45RA+CCR7+), (d) CD4+ central memory (CD45RO+CCR7+), and (e) CD8+ central memory cells were examined. The (F) CD4+ effector memory (CD45RO+CCR7-), (g) CD8+ naïve (h) CD8+ effector, and (i) CE8+ effector memory populations were also examined. n = 23 controls, n = 50 patients with FD. Data presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis for control vs FD, parametric and nonparametric t tests. For analysis of effect of stimulation with media, gluten, or gliadin within control or FD cohorts, multiple t testing was conducted with no assumptions of consistent SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. FD, functional dyspepsia.

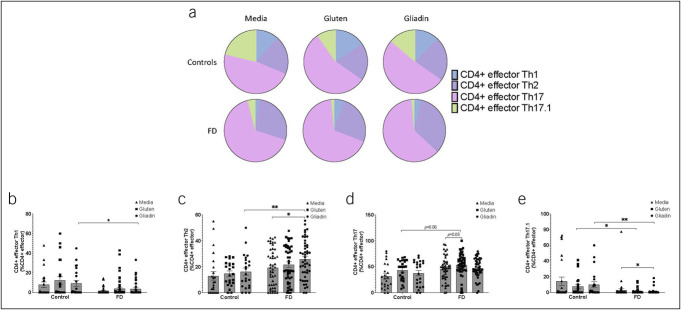

Effector T-helper cell subsets from patients with FD have altered responses to gliadin

We characterized the phenotype of effector T cells by expression of CCR4, CCR6, and CXCR3 (Figure 2a). The proportion of mucosal Th1-like cells was decreased (9.25 ± 13.68 vs 2.88 ± 5.83, P = 0.03) between controls and patients with FD (Figure 2b); however, FD-derived Th2-like cells were increased in response to gliadin compared with those in controls (16.34 ± 13.17 vs 25.83 ± 14.87, P = 0.009) and over media (19.40 ± 14.35 vs 25.83 ± 14.87, P = 0.039) (Figure 2c). By contrast, we observed a nonsignificant increase in effector Th17-like cells when stimulated with gluten in FD LPMCs compared with that in controls (43.49 ± 19.73 vs 53.92 ± 21.73, P = 0.06) and over media (45.90 ± 23.16 vs 53.57 ± 21.81, P = 0.05) (Figure 2d). Exposure to gluten (7.45 ± 12.65 vs 1.23 ± 3.04, P = 0.039) and gliadin (control 10.10 ± 16.76 vs FD 1.07 ± 3.49, P = 0.003; unstimulated FD LPMC 2.85 ± 11.39, P = 0.04) decreased the proportion of effector Th17.1-like cells (Figure 2e). When we examined the central memory populations (see Supplementary Figure 4, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16), we observed a decrease in Th2-like cells (41.44 ± 14.67 vs 34.72 ± 17.41, P = 0.043) in FD LPMCs stimulated with gluten compared with those over media. FD effector memory populations were unchanged after stimulation compared with unstimulated LPMCs (see Supplementary Figure 5, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16).

Figure 2.

Effector T-helper cell subsets in controls and patients with FD after exposure to gluten or gliadin. Effector T-helper cells (CD45RA+CCR7−) were assessed after stimulation with gluten or gliadin, without stimulation, based on expression of CCR6, CCR4, and CXCR3. (a) The balance of the effector T-helper subsets was compared between patients with FD and controls and within the 3 stimulation conditions—media (negative control), gluten, and gliadin. The (b) Th1 (CCR6−CXCR3+), (c) Th2 (CCR6−CCR4+), (d) Th17 (CCR6+CCR4+), and (e) Th17.1 (CCR6+CXCR3+) effector cell populations were examined as a percentage among the total CD3+CD4+ effector T-cell population in controls and patients with FD after stimulation with gluten or gliadin. n = 23 controls, n = 50 patients with FD. Data presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis for control vs patients with FD, parametric and nonparametric t tests based on normality testing. For analysis of effect of stimulation with media, gluten, or gliadin within controls or FD cohort, multiple t testing was performed with no assumptions of consistent SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. FD, functional dyspepsia.

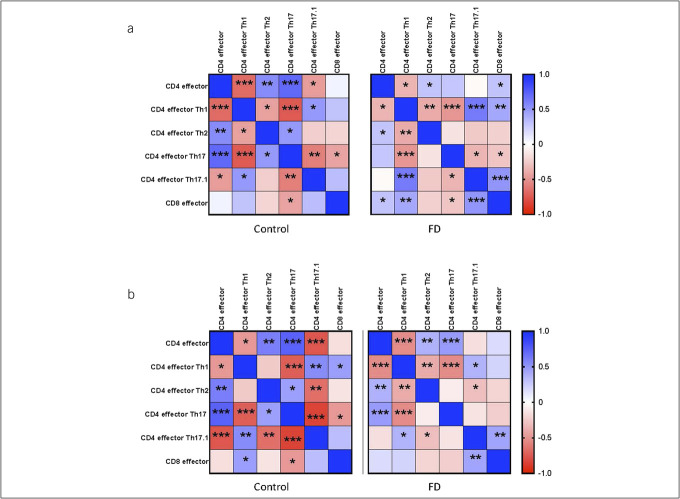

Exposure to gluten and gliadin may drive dysregulation of effector T-helper balance in FD

We next assessed relationships between effector subsets after exposure to gluten (Figure 3a) and gliadin (Figure 3b). We observed positive associations between effector Th2-like and effector Th17-like populations within controls after treatment with both gluten (rs = 0.485, P = 0.019) and gliadin (rs = 0.457, P = 0.028); however, this association was lost in FD (gluten rs = −0.137, P = 0.342; gliadin rs = −0.091, P = 0.545), suggesting dysregulation of the mucosal balance in response to wheat proteins in these patients.

Figure 3.

Correlation matrix of effector T-cell populations in patients with functional dyspepsia and controls. Flow cytometry was used to identify the phenotype of effector (CD45RA+ CCR7-) cells in LPMCs from patients with FD and controls. Heatmaps show the Spearman correlation coefficient (rs) between indicated effector T-cell subsets after stimulation with (a) gluten and (b) gliadin. n = 23 controls, n = 50 patients with FD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. FD, functional dyspepsia.

Effector Th2-like cells are increased in response to gluten in individuals with self-reported wheat sensitivity

We assessed the T-helper subsets in subjects reporting WS (n = 24) compared with those with no reported WS (n = 42), irrespective of FD or control status (see Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16). The proportion of effector Th2-like cells was increased in those reporting WS compared with that in non-WS patients (24.07 ± 10.84 vs 16.6 ± 14.75, P = 0.03) and in WS FD patients compared with that in controls (19.89 ± 15.22 vs 14.88 ± 12.14, P = 0.03), when cells received gluten stimulation. However, there was no significant difference in the proportion of the effector Th2-like cells in WS FD patients (n = 17) compared with non-WS FD patients (n = 29, 24.28 ± 12.38 vs 19.89 ± 15.22, P = 0.54) (see Supplementary Figure 6, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16). These data suggest WS is associated with an effector Th2-like response to gluten; however, wheat sensitivity may not be appreciated by all patients with FD.

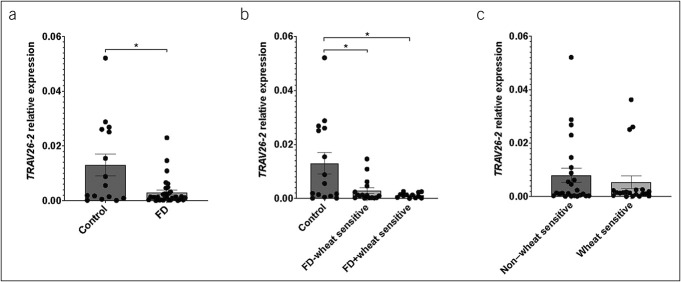

Duodenal TRAV26-2 expression is decreased in patients with FD

Given the known involvement of TRAV26-2 in gliadin processing, we aimed to investigate a relationship between its expression and FD. Biopsies of patients with FD had decreased TRAV26-2 expression (0.013 ± 0.015 vs 0.003 ± 0.005, P = 0.036) (Figure 4a). Within the FD cohort, there was no significant difference in TRAV26-2 expression between those with self-reported WS (n = 12), compared with those without (n = 16), and both groups had significantly lower expression than controls (non-WS 0.003 ± 0.0043, P = 0.047 vs controls; WS 0.001 ± 0.001, P = 0.035 vs controls, P = 0.781 vs non-WS) (Figure 4b), suggesting that perceived WS is independent of duodenal TRAV26-2 expression. Irrespective of FD diagnosis, there was no significant difference in duodenal expression of TRAV26-2 between self-reported WS (n = 20) and those without (n = 24) (non-WS 0.008 ± 0.013 vs WS 0.005 ± 0.011, P = 0.683) (Figure 4c). These data suggest differential TCR variants contribute to the overlap of WS and FD.

Figure 4.

TRAV26-2 gene expression in wheat-sensitive participants and patients with FD. Quantitative PCR was used to evaluate (a) the relative expression of TRAV26-2 to β-actin in patients with FD (n = 33) compared with that in controls (n = 15), (b) in patients with FD stratified by those with self-reported wheat sensitivity (n = 12) and those without (n = 16), and (c) in all participants self-reporting wheat sensitivity (n = 20) compared with those without (n = 23). Data presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis (a, c) nonparametric unpaired t test (b) nonparametric 1-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05. FD, functional dyspepsia.

TRAV26-2 expression correlates with Th17 cell populations after gluten stimulation in patients with FD

Because we observed a significant decrease in TRAV26-2 expression in patients with FD compared with controls, we aimed to determine whether duodenal TRAV26-2 was associated with any LPMC response to stimulation with gluten or gliadin. Correlation analysis of cellular subsets after gluten stimulation against duodenal TRAV26-2 expression (see Supplementary Table 5, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16) revealed no relationship with antigen-experienced Th17-like cells in the control cohort (rs = 0.2916, P = 0.331) (Figure 5ai), but a positive correlation was observed in FD (rs = 0.5349, P = 0.002) (Figure 5aii). We then subdivided the patients with FD based on those with TRAV26-2 relative expression values equal to or above the cohort median of 0.0013 and those whose values were lower. We found patients with FD with higher TRAV26-2 expression had higher proportions of CD4+CD45RO+ Th17-like cells after stimulation with gluten (26.10 ± 12.98 vs 37.72 ± 16.37, P = 0.042) (Figure 5b). There was a similar relationship between TRAV26-2 expression and the proportions of effector Th17-like cells in FD (rs = 0.3733, P = 0.042), but not controls (rs = 0.2238, P = 0.485) (Figures 5ci,ii). When the patients with FD were separated into high and low TRAV26-2 expression, patients with lower TRAV26-2 expression had lower effector Th17-like proportions (65.78 ± 17.01 vs 54.77 ± 13.47, P = 0.033) (Figure 5d). There were no associations between TRAV26-2 expression and lymphocytes after gliadin treatment (see Supplementary Table 6, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16).

Figure 5.

Associations between T-cell subsets after gluten stimulation and TRAV26-2 gene expression in controls and patients with FD. Correlation analyses were used to examine whether there was a relationship between the T-cell response to gluten stimulation in controls and patients with FD and expression of the T-cell receptor alpha variant TRAV26-2. Potential relationships between antigen-experienced Th17 populations and TRAV26-2 were examined in (ai) controls and (aii) patients with FD. (b) We then subdivided the FD cohort by those with TRAV26-2 gene expression equal to or greater than the cohort median and those with lower expression to determine whether there was a difference in antigen-experienced Th17 populations in these subsets. We also investigated a potential relationship between CD4+ effector Th17 cells and TRAV26-2 expression in LPMCs from (ci) controls and (cii) patients with FD after gluten exposure and (d) differences between patients with FD with high and low gene expression. n = 12 controls, n = 32 FD. Data presented as mean ± SEM (b, d). Statistical analysis nonparametric Spearman rs correlation (a, c) and nonparametric or parametric 1-way ANOVA (b, d). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. FD, functional dyspepsia.

There was no significant correlation between TRAV26-2 expression and cytokine concentrations in gluten (see Supplementary Table 7, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16) or gliadin (see Supplementary Table 8, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16) stimulated-LPMC supernatants. We also found no relationship between duodenal TRAV26-2 expression and IFN-γ in controls (rs = −0.8392, P = 0.80) (see Supplementary Figure 7A, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16). However, TRAV26-2 expression and IFN-γ trended toward a negative correlation in patients (rs = −0.3571, P = 0.053) (see Supplementary Figure 7B, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16). Division of patients into high-TRAV26-2 and low-TRAV26-2 expression revealed no difference in IFN-γ, although there was a trend toward increased concentration in TRAV26-2–low compared with TRAV26-2–high patients with FD (0.001674 ± 0.001025 vs 0.002438 ± 0.001250, P = 0.066) (see Supplementary Figure 7C, Supplementary Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16), suggesting LPMCs from patients with lower TRAV26-2 produce more IFN-γ in response to gliadin.

DISCUSSION

Recent work has shown that patients with DGBI who report WS have both a distinct mucosal microbiota and increased circulating gut-homing T cells when compared with non-WS and controls (24). Given that localized rectal immune responses to food (including wheat) have been observed in IBS (30), we aimed to determine whether gluten or gliadin provoked responses in FD-derived LPMCs. Our exploratory findings demonstrate increased proportions of Th2-like effector cells in FD LPMCs after gliadin exposure. Patients with FD have reduced expression of TRAV26-2, which is implicated in biased TCR responses to wheat in patients with celiac disease (23). Duodenal eosinophilia in FD has led to suggestions of a Th2 phenotype for microinflammation, and we have recently shown that duodenal effector Th2-like cells and Th17-like cells are increased in FD (25); however, the antigen(s) stimulating this response were unclear. Both Th17 and Th2 cells are capable of driving eosinophil recruitment and activation (31), and our data suggest gliadin can drive proliferation of an effector Th2-like response, while the Th17-like response may be initiated by microbial antigens (32,33). Given Th17-like subsets correlated with reduced TRAV26-2 expression in patients with FD, 1 hypothesis is that patients with the TRAV26-2 variant may have poor Th17 responses to infections or altered microbial profiles, contributing to heightened immune surveillance. In this scenario, subsequent exposure to food triggers an effector Th2 response, instead of tolerance, to gliadin. An alternative hypothesis is that the contribution of microbial metabolism to wheat digestion (34) results in the generation of immunogenic epitopes that drive differential responses to wheat-associated proteins, and this may be supported by the distinct mucosal microbiome signatures in patients with WS DGBI (24).

Given reports of alterations in specific T-cell subpopulations in FD (25,35–37), it is possible that TCR variants contribute to low-grade inflammation in FD because binding strength of the MHC-antigen-TCR interaction regulates the strength of an immune response (38,39). There are other variants, including TCR beta (TRBV)7-2 and TRBV9, with demonstrated affinity for immunogenic wheat peptides (40) and may warrant investigation. Associations of TRAV26-2 expression with lymphocytes suggest that a subset of patients are predisposed to the development of Th17-dominant responses to gluten; however, this requires direct confirmation. We also observed a trend toward a negative correlation between IFN-γ levels and TRAV26-2 expression after gliadin stimulation in FD. Given that IFN-γ is typically secreted by Th1 cells and we observed increased effector Th2-like cells after gliadin stimulation, TRAV26-2 may affect the Th1/Th2 balance in FD. This is interesting given the Th1/Th17 phenotype of gliadin responses in celiac disease (41), while responses to gliadin in our FD cohort more closely resemble a Th2-dominant, atopy-like response. Assessment of other Th2-associated cytokines (e.g.IL-5, IL-13) not included in our current analysis would confirm this; however, this would require a shorter stimulation time due to the short half-life of cytokines. In addition, further investigation of symptom pattern and severity and wheat responses in a larger cohort are required to fully appreciate the translational implications of these findings.

A limitation of this work is that cytokines were measured at a single time point and therefore may not accurately reflect dynamic changes occurring in the immediate hours after antigen encounter in vivo (42). Low LPMC number and viability could potentially be overcome using PBMCs, allowing for recording of more flow cytometric events; however, previous work has suggested responses to food antigens in DGBIs are specific to the gut (30,43,44). As such, the utility of using PBMCs to detect such responses in these patients remains unclear. Furthermore, the commercially available wheat proteins used were in native form and may not account for physiological and microbial digestion of gluten in vivo (45), which may be critical for immune activation. The in vitro stimulation approach in this study captures the capacity of the cells to respond to specific antigens and reflect the biological education of these cells. However, this may not perfectly translate to the in vivo environment, where factors upstream of the antigen immune cell interaction (i.e. diet, physiological and microbial peptide digestion) also affect the response. In addition, concentration of gliadin in pure gliadin versus gluten may account for some gliadin responses not being seen after stimulation with gluten, despite gluten containing gliadin. Of importance, it is unlikely all patients with FD have wheat-specific responses, given a range of food triggers (2) and brain-to-gut specific pathways (46,47) are associated with FD. This likely accounts for some of the clustering within our data sets. However, we have not yet successfully defined what differentiates immune responsive individuals from nonresponsive individuals, and further work is required in this space. Nevertheless, this work has shown that LPMCs from FD and non-FD participants respond differently to stimulation and responses to both native and deamidated gliadin peptides have been observed in human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ8-mediated celiac disease (48,49). Given the difficulties in obtaining biopsies from healthy individuals, our control cohort is limited by small participant numbers and the use of outpatient controls, a common problem in FD studies (50). Furthermore, it is important to consider that participants in this study are outpatients of a gastroenterology clinic and therefore may not represent the entire spectrum of FD severity (51). Unfortunately, metadata regarding comorbid atopic/autoimmune conditions and medications that may influence the LPMC repertoire was incomplete, hampering our capacity to perform subanalyses on these variables. Despite these limitations, differences in T-cell responses to wheat proteins observed in this exploratory study provide a rationale to further investigate these findings in a larger cohort.

The findings of this observational study suggest differential T-cell responses to gluten and gliadin in some patients with FD. These results suggest Th2 responses previously proposed in FD may occur in response to food components such gliadin. We also show that patients with FD have reduced expression of TRAV26-2, previously associated with T-cell responses against gliadin in celiac disease. We also show that TRAV26-2 expression correlated with Th17-like populations, suggesting that specific TCR variants in patients with FD may be associated with an immune response to the consumption of wheat-containing foods.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Prof. Simon Keely, PhD

Specific author contributions: S.K., N.J.T., M.M.W. and G.H. participated in the design of the concept, hypothesis, and aims of the study. G.L.B and S.K participated in initial drafting of the manuscript. G.L.B performed sample processing, stimulation experiments, cytokine assays and analysis. J.B., M.P., A.M., K.M., J.P., C.N., S.S., and T.F. assisted with collection and processing of patient samples. R.C. and M.M.W. performed histological analysis. J.L.B, and A.C. advised on data analysis. M.P., S.B., M.Z.I., L.T.G., R.F., M.V., A.S., G.H. and N.J.T. assisted with recruitment and review of cohort. P.S.F and J.H. assisted with resources, experimental design and manuscript editing. G.H., K.D., N.P., M.M.W., N.J.T, and S.K. assisted with concept, experimental design and manuscript editing. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support: This study was supported by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

Potential competing interests: M.M.W.: grant/research support: Prometheus Laboratories Inc [irritable bowel syndrome (IBS Diagnostic), Commonwealth Diagnostics International (Biomarkers for FGIDs). K.D.: Patent Holder: FODMAP and gluten-modified grain food products [FGIDs: Australian Patent No. 2014262285; New Zealand Patent No. 629207; South Africa Patent No. 2015/07891]. G.H.: Unrestricted educational support from Bayer Pty, Ltd. and the Falk Foundation. Research support was provided through the Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane by GI Therapies Pty Limited, Takeda Development Center Asia, Pty Ltd., Eli Lilly Australia Pty Limited, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Limited, MedImmune Ltd. Celgene Pty Limited, Celgene International II Sarl, Gilead Sciences Pty Limited, Quintiles Pty Limited, Vital Food Processors Ltd., Datapharm Australia Pty Ltd. Commonwealth Laboratories, Pty Limited, Prometheus Laboratories, Falk GmbH, and Co Kg, Nestle Pty Ltd., Mylan. Patent Holder: A biopsy device to take aseptic biopsies (US 20150320407 A1). N.J.T.: grant/research support: Rome Foundation; Abbott Pharmaceuticals; Datapharm; Pfizer; Salix [irritable bowel syndrome]; Prometheus Laboratories Inc [irritable bowel syndrome (IBS Diagnostic)]; Janssen [Constipation]. Consultant/advisory boards: Adelphi Values [Functional dyspepsia (patient-reported outcome measures)]; (Budesonide)]; GI therapies [Chronic constipation (Rhythm IC)]; Allergens PLC; Napo Pharmaceutical; Outpost Medicine; Samsung Bioepis; Yuhan [IBS]; Synergy [IBS]; and Theravance [Gastroparesis]. Patent Holder: Biomarkers of irritable bowel syndrome [irritable bowel syndrome] Licensing Questionnaires [Mayo Clinic Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire - Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire]; Nestec European Patent [Application No. 12735358.9]; Singapore Provisional Patent [NTU Ref: TD/129/17 Microbiota Modulation of BDNF Tissue Repair Pathway]. S.K.: grant/research support: Cancer Institute NSW (Career Development Fellowship), National Health and Medical Research Council (Project Grant APP1128487) Commonwealth Diagnostics International (Biomarkers for FGIDs), Syntrix Biosystems (contract research–drug delivery), and Fisher and Paykel Healthcare (investigator-initiated research project). G.L.B., M.P., A.M., J.B., K.M., J.L.B., J.P., C.N., S.S., A.C., T.F., R.C., S.B., M.Z.I., R.F., L.T.G., A.S., N.K., P.S.F., J.C.H., N.P., M.V.: None to report.

IRB Approval Statement: Research undertaken was approved by Hunter New England (reference 13/12/11/3.01) and Metro South Health (reference HREC/13/QPAH/690) Human Research Ethics Committees. Written informed consent was received before participation.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS KNOWN

✓ Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a chronic condition associated with gastroduodenal symptoms where patients commonly report wheat consumption as a trigger for symptom onset.

✓ Physiological and immune abnormalities including duodenal eosinophilia and increased intestinal permeability have been demonstrated in FD, suggesting aberrant immune responses to food antigens may be involved in symptom onset.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

✓ Exposure to gliadin provoked an increase in lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMCs) with an effector T helper (Th) 2–like phenotype isolated from patients with FD, compared with control LPMCs.

✓ The gene expression of TRAV26-2 is reduced in patients with FD compared with that in controls. TRAV26-2 is a T-cell receptor variant associated with preferential gliadin processing in celiac disease.

✓ TRAV26-2 expression is associated with Th17-like responses in patients with FD to gluten, but not gliadin.

✓ These data suggest that wheat consumption may drive symptom onset in a subset of patients, and T-cell receptor variants may be implicated in the subtle nature of the immune activation seen in FD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Department of Gastroenterology at the John Hunter Hospital, New Lambton Heights, Australia, and Newcastle Endoscopy Centre, Charlestown, Australia, for their support and assistance with the collection of biopsy samples. We are grateful for the support of Prof. Mike Jones, School of Psychological Sciences, Macquarie University, Australia regarding statistical analysis. We also like to acknowledge the support of Nicole Cole (Analytical Biomolecular Research Facility, University of Newcastle, Australia) and Dr Andrew Lim, Dr Carole Ford, Dr Nikki Alling, Dr Frank Kao, and Dr Ali Kamene (BD Biosciences, Australia and New Zealand) for their help and assistance with flow cytometry for this work.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL accompanies this paper at http://links.lww.com/CTG/B16

Nicholas J. Talley and Simon Keely contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Grace L. Burns, Email: g.burns@newcastle.edu.au.

Michael Potter, Email: Michael.Potter@health.nsw.gov.au.

Andrea Mathe, Email: andrea.mathe@newcastle.edu.au.

Jessica Bruce, Email: jessica.bruce@uon.edu.au.

Kyra Minahan, Email: Kyra.Minahan@newcastle.edu.au.

Jessica L. Barnes, Email: jessica.barnes@newcastle.edu.au.

Jennifer Pryor, Email: jennifer.pryor@uon.edu.au.

Cheenie Nieva, Email: Cheenie.nieva@uon.edu.au.

Simonne Sherwin, Email: simonne.sherwin@newcastle.edu.au.

Annalisa Cuskelly, Email: annalisa.cuskelly@uon.edu.au.

Thomas Fairlie, Email: thomas.fairlie@uqconnect.edu.au.

Raquel Cameron, Email: raquel.cameron@newcastle.edu.au.

Steven Bollipo, Email: steven.bollipo@health.nsw.gov.au.

Mudar Zand Irani, Email: mudar.zandirani@uon.edu.au.

Robert Foster, Email: Robert.Foster@health.nsw.gov.au.

Lay T. Gan, Email: LayTheng.Gan@health.nsw.gov.au.

Ayesha Shah, Email: Ayesha.shah@uq.edu.au.

Natasha Koloski, Email: natasha.koloski@newcastle.edu.au.

Paul S. Foster, Email: paul.foster@newcastle.edu.au.

Jay C. Horvat, Email: jay.horvat@newcastle.edu.au.

Marjorie M. Walker, Email: marjorie.walker@newcastle.edu.au.

Nick Powell, Email: nicholas.powell@imperial.ac.uk.

Martin Veysey, Email: Martin.Veysey@nt.gov.au.

Kerith Duncanson, Email: kerith.duncanson@newcastle.edu.au.

Gerald Holtmann, Email: g.holtmann@uq.edu.au.

Nicholas J. Talley, Email: nicholas.talley@newcastle.edu.au.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: History, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016;150(6):1262–79.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duncanson KR, Talley NJ, Walker MM, et al. Food and functional dyspepsia: A systematic review. J Hum Nutr Diet 2018;31(3):390–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du L, Shen J, Kim JJ, et al. Impact of gluten consumption in patients with functional dyspepsia: A case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;33(1):128–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carvalho RV, Lorena SL, de Souza Almeida JR, et al. Food intolerance, diet composition, and eating patterns in functional dyspepsia patients. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55(1):60–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106(3):508–14; quiz 515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potter MDE, Walker MM, Jones MP, et al. Wheat intolerance and chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in an Australian population-based study: Association between wheat sensitivity, celiac disease and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113(7):1036–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elli L, Tomba C, Branchi F, et al. Evidence for the presence of non-celiac gluten sensitivity in patients with functional gastrointestinal symptoms: Results from a multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled gluten challenge. Nutrients 2016;8(2):84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molina-Infante J, Carroccio A. Suspected nonceliac gluten sensitivity confirmed in few patients after gluten challenge in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15(3):339–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, et al. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology 2013;145(2):320–8.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroccio A, Giannone G, Mansueto P, et al. Duodenal and rectal mucosa inflammation in patients with non-celiac wheat sensitivity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17(4):682–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroccio A, Mansueto P, Iacono G, et al. Non-celiac wheat sensitivity diagnosed by double-blind placebo-controlled challenge: Exploring a new clinical entity. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107(12):1898–906. quiz 1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talley NJ, Walker MM, Aro P, et al. Non-ulcer dyspepsia and duodenal eosinophilia: An adult endoscopic population-based case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5(10):1175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker MM, Aggarwal KR, Shim LSE, et al. Duodenal eosinophilia and early satiety in functional dyspepsia: Confirmation of a positive association in an Australian cohort. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29(3):474–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vazquez-Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, et al. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: Effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology 2013;144(5):903–11 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollon J, Puppa EL, Greenwald B, et al. Effect of gliadin on permeability of intestinal biopsy explants from celiac disease patients and patients with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Nutrients 2015;7(3):1565–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishigami H, Matsumura T, Kasamatsu S, et al. Endoscopy-guided evaluation of duodenal mucosal permeability in functional dyspepsia. Clin Translational Gastroenterol 2017;8(4):e83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komori K, Ihara E, Minoda Y, et al. The altered mucosal barrier function in the duodenum plays a role in the pathogenesis of functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci 2019;64(11):3228–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tjon JM, van Bergen J, Koning F. Celiac disease: How complicated can it get? Immunogenetics 2010;62(10):641–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noguchi E, Akiyama M, Yagami A, et al. HLA-DQ and RBFOX1 as susceptibility genes for an outbreak of hydrolyzed wheat allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019;144(5):1354–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maki M, Caporale D. HLA-DQ1 alpha and beta genotypes associated with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. FASEB J 2017;31(S1):612.1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang CY, Yu PF, He XB, et al. αβ T-cell receptor bias in disease and therapy (Review). Int J Oncol 2016;48(6):2247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christophersen A, Ráki M, Bergseng E, et al. Tetramer-visualized gluten-specific CD4+ T cells in blood as a potential diagnostic marker for coeliac disease without oral gluten challenge. United Eur Gastroenterol J 2014;2(4):268–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen J, van Bergen J, Loh KL, et al. Determinants of gliadin-specific T cell selection in celiac disease. The J Immunol 2015;194(12):6112–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah A, Kang S, Talley NJ, et al. The duodenal mucosa associated microbiome, visceral sensory function, immune activation and psychological comorbidities in functional gastrointestinal disorders with and without self-reported non-celiac wheat sensitivity. Gut Microbes 2022;14(1):2132078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns GL, Bruce JK, Minahan K, et al. Type 2 and type 17 effector cells are increased in the duodenal mucosa but not peripheral blood of patients with functional dyspepsia. Front Immunol 2022;13:1051632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talley NJ, Haque M, Wyeth JW, et al. Development of a new dyspepsia impact scale: The nepean dyspepsia index. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999;13(2):225–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130(5):1466–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silveira-Mattos PS, Narendran G, Akrami K, et al. Differential expression of CXCR3 and CCR6 on CD4+ T-lymphocytes with distinct memory phenotypes characterizes tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Sci Rep 2019;9(1):1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zielinski CE, Corti D, Mele F, et al. Dissecting the human immunologic memory for pathogens. Immunological Rev 2011;240(1):40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aguilera-Lizarraga J, Florens MV, Viola MF, et al. Local immune response to food antigens drives meal-induced abdominal pain. Nature 2021;590(7844):151–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keely S, Foster PS. Stop press: Eosinophils drafted to join the Th17 team. Immunity 2015;43(1):7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burns G, Pryor J, Holtmann G, et al. Immune activation in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;15(10):539–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wauters L, Slaets H, De Paepe K, et al. Efficacy and safety of spore-forming probiotics in the treatment of functional dyspepsia: A pilot randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;6(10):784–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kõiv V, Tenson T. Gluten-degrading bacteria: Availability and applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2021;105(8):3045–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gargala G, Lecleire S, Francois A, et al. Duodenal intraepithelial T lymphocytes in patients with functional dyspepsia. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13(16):2333–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kindt S, Van Oudenhove L, Broekaert D, et al. Immune dysfunction in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterology Motil 2009;21(4):389–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adam B, Liebregts T, Bredack C, et al. Small bowel homing T cells are associated with symptoms and delayed gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2011;140(5):1089–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsui K, Boniface JJ, Steffner P, et al. Kinetics of T-cell receptor binding to peptide/I-Ek complexes: Correlation of the dissociation rate with T-cell responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994;91(26):12862–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sykulev Y, Brunmark A, Jackson M, et al. Kinetics and affinity of reactions between an antigen-specific T-cell receptor and peptide-mhc complexes. Immunity 1994;1(1):15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiao SW, Christophersen A, Lundin KE, et al. Biased usage and preferred pairing of alpha- and beta-chains of TCRs specific for an immunodominant gluten epitope in coeliac disease. Int Immunol 2014;26(1):13–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castellanos-Rubio A, Santin I, Irastorza I, et al. TH17 (and TH1) signatures of intestinal biopsies of CD patients in response to gliadin. Autoimmunity 2009;42(1):69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friberg D, Bryant J, Shannon W, et al. In-vitro cytokine production by normal human peripheral-blood mononuclear-cells as a measure of immunocompetence or the state of activation. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 1994;1(3):261–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fritscher-Ravens A, Pflaum T, Mosinger M, et al. Many patients with irritable bowel syndrome have atypical food allergies not associated with immunoglobulin E. Gastroenterology 2019;157(1):109–18 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fritscher-Ravens A, Schuppan D, Ellrichmann M, et al. Confocal endomicroscopy shows food-associated changes in the intestinal mucosa of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014;147(5):1012–20.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutierrez S, Perez-Andres J, Martinez-Blanco H, et al. The human digestive tract has proteases capable of gluten hydrolysis. Mol Metab 2017;6(7):693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koloski NA, Jones M, Kalantar J, et al. The brain--gut pathway in functional gastrointestinal disorders is bidirectional: A 12-year prospective population-based study. Gut 2012;61(9):1284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koloski NA, Jones M, Talley NJ. Evidence that independent gut-to-brain and brain-to-gut pathways operate in the irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia: A 1-year population-based prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;44(6):592–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henderson KN, Tye-Din JA, Reid HH, et al. A structural and immunological basis for the role of human leukocyte antigen DQ8 in celiac disease. Immunity 2007;27(1):23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sollid LM, Markussen G, Ek J, et al. Evidence for a primary association of celiac disease to a particular HLA-DQ alpha/beta heterodimer. J Exp Med 1989;169(1):345–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burns G, Carroll G, Mathe A, et al. Evidence for local and systemic immune activation in functional dyspepsia and the irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114(3):429–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ford AC, Talley NJ. Mucosal inflammation as a potential etiological factor in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. J Gastroenterol 2011;46(4):421–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]