Abstract

Objectives

Breastfeeding is an energetically costly and intense form of human parental investment, providing sole-source nutrition in early infancy and bioactive components, including immune factors. Given the energetic cost of lactation, milk factors may be subject to tradeoffs, and variation in concentrations have been explored utilizing the Trivers-Willard hypothesis As human milk immune factors are critical to developing immune system and protect infants against pathogens, we tested whether concentrations of milk immune factors (IgA, IgM, IgG, EGF, TGFβ2, and IL-10) vary in response to infant sex and maternal condition [proxied by maternal diet diversity (DD) and body mass index (BMI)] as posited in the Trivers-Willard hypothesis and consider the application of the hypothesis to milk composition.

Methods

We analyzed concentrations of immune factors in 358 milk samples collected from women residing in 10 international sites using linear mixed-effects models to test for an interaction between maternal condition, including population as a random effect and infant age and maternal age as fixed effects.

Results

IgG concentrations were significantly lower in milk produced by women consuming diets with low diversity with male infants than those with female infants. No other significant associations were identified.

Conclusions

IgG concentrations were related to infant sex and maternal diet diversity, providing minimal support for the hypothesis. Given the lack of associations across other select immune factors, results suggest that the Trivers-Willard hypothesis may not be broadly applied to human milk immune factors as a measure of maternal investment which are likely buffered against perturbations in maternal condition.

Keywords: breast milk, human milk, breastfeeding, parental investment, immunity, life history theory

INTRODUCTION

The composition and abundance of human milk immune factors are known to be reflective of a mother’s environmental conditions, including her physical environment (Peroni et al., .2010), geographical location (Amoudruz et al., 2009; Holmlund et al., 2010; Munblit et al., 2016; Ruiz et al., 2017), subsistence strategy (Klein et al., 2018), and microbial exposure (Tomičić et al., 2010, McGuire et al., 2021; Prentice, Watkinson, Prentice, Cole & Whitehead, 1984). Human milk immune factors are also associated with a variety of maternal and infant characteristics including delivery mode (Groer, Davis & Steele, 2004; Striker, Casanova & Nagao, 2004), gestational age (Castellote et al., 2011), mastitis (Prentice, Prentice & Lamb, 1985; Hassiotou et al., 2013; Hunt et al., 2013; Espinosa-Martos et al., 2016; Castro et al., 2022), time postpartum (Turin and Ochoa, 2014; Moles et al., 2015; Ballard and Morrow, 2013; Munblit et al., 2016; Goldman et al., 1983, Czosnyskowska-Lukacka et al., 2020, Prentice, Prentice, Cole, Paul & Whitehead, 1983), pasteurization method (Espinosa-Martos et al., 2013; Escuder-Vieco et al., 2018), and infant illness (Hassiotou et al., 2013; Riskin et al. 2012; Bryan et al., 2007; Breakey et al., 2015). Maternal diet (Urwin et al., 2012; Böttcher et al., 2008) and nutritional status (Lu, Jiang, Wu & Li ,2018; Miranda et al.,1983) are also frequently associated with variation of immune factor concentrations in milk.

Reflecting local ecology (Klein et al., 2018), human milk is thus uniquely suited to prime newborns for their environment (Andreas, Kampmann & Le-Doare, 2015; Brandtzaeg, 2003). In the early postpartum period, a time when infants’ immune systems remain naive (Ballard & Morrow, 2013), mothers transfer immunity to their infants via the provision of colostrum and milk (Andreas et al., 2015; Brandtzaeg, 2003). Lactation, however, is an energetically costly form of parental investment (600 kcals per day; Lunn 1994; Butte & King 2005) which involves diverting available energy away from maternal needs to the synthesis of milk for the offspring, an investment that can span several months to years (Valeggia & Ellison, 2001).Therefore, lactation and the composition of human milk are likely subject to energetic tradeoffs and may be responsive to proximate cues in the environment and from the mother-infant dyad.

Evolutionary approaches to human parental investment and human milk composition

Evolutionary approaches examining how parental investment may interact and influence human milk composition (e.g., Powe, Knott & Conklin-Brittain 2010; Fujita, Wander, Ruvalcaba,& Brindle, 2019) have typically centered on whether there are associations between a mother’s milk composition and the sex of her infant (e.g., do male infants receive milk that has higher energy density than female infants?). A subset of these papers has directly or indirectly examined the Trivers Willard hypothesis or the interaction effects between maternal condition and infant sex on milk composition (Powe et al., 2010; Fujita et al., 2012; Quinn, 2013; 2019; Fujita et al., 2019; Eckart et al., 2022). Trivers-Willard posits that mothers attain greater reproductive success through investing in offspring that are most likely to obtain greater fitness (Trivers & Willard, 1973). Briefly, the hypothesis suggests that maternal condition will influence offspring condition and argues males born to mothers in poor condition (e.g., underweight, malnourished) will experience poor condition and have more challenges in obtaining mates and reproducing than males born to mothers in good condition. Mothers in poor condition are predicted to skew their investment toward female infants, who experience lower levels of reproductive variability, while mothers in good conditions are expected to skew investment towards male offspring because, under those conditions, males may achieve greater reproductive success than their female counterparts (Trivers & Willard, 1973).

Human milk is viewed as a form of parental investment, whereas milk synthesis under certain circumstances can conflict with maternal interest. For example, the mobilization of body stores to source calcium for milk production leads to temporal bone mineral loss in mothers until after weaning (Kalkwarf & Specker, 2001). Currently, it remains uncertain whether milk immune factors are costly enough to produce to be considered maternal investment. However, several studies on IgA suggest that it is a possibility. For instance, certain situations such as extreme undernutrition (Miranda et al., 1983), reduced food availability (Weaver, Arthur, Bunn & Thomas, 1998) and intensive exercise Gregory, Wallace, Gfell, Marks & King, 1997) have shown a decrease in milk IgA concentrations.

Applications of the Trivers-Willard hypothesis to human milk composition, however, have yielded conflicting results. Among well-nourished women in the United States, Powe et al. (2010) found the milk produced by women breastfeeding male infants was higher in energy density than the milk of mothers with female infants. Fujita et al. (2012) found higher fat content in the milk of poor Kenyan mothers with female infants, while economically secure Kenyan mothers produced milk with higher fat content for their sons. Results from another study in the same population showed that mothers with high mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) with sons had higher concentrations of secretory Immunoglobulin A (sIgA) in their milk than did mothers with daughters. Conversely, mothers with low MUAC and with daughters had higher concentrations of sIgA in their milk than did mothers with sons (Fujita et al., 2019). However, among Filipino mothers, Quinn (2013) found no evidence of an infant sex bias in either fat, lactose, protein, or energy content of the milk of mothers when accounting for maternal BMI. In general, studies testing the Trivers-Willard hypothesis in post-birth parental investment contexts have been challenged by a lack of cross-cultural data, small sample sizes, and the operationalization of parental investment and maternal condition (Cronk, 2007; Thouzeau, Cristia & Chevallier, 2022). Nevertheless, the hypothesis continues to be tested across a variety of parental investment domains (e.g., Pink, Schaman & Fieder, 2017; Lynch, Wasielewski & Cronk 2018; Song 2018).

Here, utilizing a previously collected dataset including a range of human milk immune factors (Immunoglobulin A, Immunoglobulin G, Immunoglobulin M, Epidermal Growth Factor, Transforming Growth Factor Beta 2, and Interleukin-10) and standardized maternal condition variables (maternal BMI and diet diversity scores) from a multi-cohort, international human milk composition study (the INSPIRE study), we test the Trivers Willard hypothesis and consider its utility as an evolutionary framework in human milk studies. The application of the Trivers-Willard hypothesis to human milk immune factors would suggest that resource limited mothers may face a tradeoff between caloric investment in milk and production of milk immune factors. These might covary due to phenotypic correlation, but immune factors might be expected to be prioritized secondary to basic caloric needs. It is important to note that costs to mothers of producing human milk immune factors are unknown and therefore operationalizing human milk immune factors as investment is challenging. Nevertheless, this study represents the largest, methodologically consistent test of this hypothesis to our knowledge. Therefore, if the investment variation predictions of Trivers-Willard hypothesis apply to human milk immune factors, we should expect concentrations of immune factors will be lower in milk produced by underweight or overweight/obese women or women consuming diets with lower diversity (indicating poor nutritional status, i.e., poor condition) with sons than those in milk produced by mothers in poor conditions with daughters. Specifically, we test whether Immunoglobulin A (IgA), Immunoglobulin G (IgG), Immunoglobulin M (IgM), Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF), Transforming Growth Factor Beta 2(TGFβ2), and Interleukin 10 (IL-10) concentrations in the milk of mothers with infants varied according to the interaction between infant sex and maternal condition.

METHODS

Study populations

Data used in this analysis were previously collected as part of a prospective multi-cohort, international, cross-sectional study (the INSPIRE study) (McGuire et al., 2017, Ruiz et al., 2017, Lackey et al., 2019, Lane et al., 2019, McGuire et al., 2021, Pace et al., 2021). Data were collected on 410 breastfeeding women and their infants between May 2014 and April 2016. The original sample set included two European (Spanish and Swedish), one South American (Peruvian), two North American (United States: Southeastern Washington/northwestern Idaho and southern California), and six sub-Saharan African (rural and urban Ethiopian, rural and urban Gambian, Ghanaian, and Kenyan) cohorts. Detailed descriptions of these populations have been published previously (see Ruiz et al., 2017, McGuire et al., 2017). The rural Ethiopian cohort (n =40) was not included in this study due to variation in sample preservation approaches that prevented immune factor analysis.

Women did not have to be exclusively breastfeeding to participate. Infants enrolled in the study were between the ages of two weeks and five months. To be included in the study, infants had to be reported healthy by their mothers, defined as no reported illness (including fever, vomiting, severe cough, rapid breathing or diarrhea) seven days prior to enrollment and have not been given antibiotics in the month prior to participation. Mothers had to self-report as healthy, defined as having had no symptoms of illness (including fever, vomiting, severe cough or diarrhea) in the seven days prior to enrollment, not experiencing breast infection or atypical breast pain that they did not consider normal for lactation, and had not taken antibiotics in the 30 days before enrollment. Informed, verbal, or written consent (depending on locale and the subject’s literacy level) was acquired from each participating woman. Ethics approvals were obtained for all procedures from each participating institution and with overarching approval from the Washington State University Institutional Review Board (IRB #13264).

Milk Collection

All milk collection supplies (including gloves, soap wipes, and collection containers) were standardized and provided to personnel at each site to help control for known and unknown biases. The participant’s study breast was cleaned twice with pre-packaged soap wipes by gloved hands either by researchers or participants. At least 20 mL of milk were expressed either by hand or by use of an electric pump (Medela, Inc. McHenry, IL) into a single-use, sterile polypropylene milk container with a polybutylene cap (Medela, Inc.) or polypropylene specimen containers with polyethylene caps (VWR International, LLC). Milk was placed on ice or in a cold box until aliquoted (within 1 hour of the collection). Aliquots of milk were frozen at −20 °C and then shipped on dry ice to Complutense University in Madrid, where immunological assays were performed.

Immune Factors and Immunological Assays

We have previously reported the detailed description of the immunological assay and the wide range of concentrations of immune factors in milk of participants in the INSPIRE study (Ruiz et al., 2017). Briefly, samples from all study sites were aliquoted and subjected to a single freeze-thaw cycle and were analyzed by the same researchers using the same reagents and equipment to reduce potential lab biases. To avoid defrosting cycles, individual aliquots were used for each analysis. Prior to analyses, 1 ml samples were centrifuged at 800g for 15 minutes at 4°C to remove the fatty layer and the intermediate aqueous phase was used for the immunoassay determinations as previously described (Espinosa-Martos et al., 2013). All assays were run in duplicate according to manufacturer’s instructions and standards curves were performed for each analyte. Magnetic bead-based multiplex immunoassays were used to assess the concentrations of TGFβ2 and IL-10 (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). TGFβ2 was acid-activated prior to analysis, per manufacturer recommendations. The RayBio Human EGF ELISA kit was used to quantify EGF concentration (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA, USA). The concentrations of IgG, IgA, and IgM were determined using the Bio-plex Pro Human Isotyping Assay kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Immunoglobulins (IgA, IgG, IgM) were measured in milligrams per liter, IL-10 in nanograms per liter, and EGF and TGFβ2 in micrograms per liter (Ruiz et al., 2017). The inter-assay coefficient of variation were below manufacturer’s instructions for all immune markers and detection limits of assays reported previously (Ruiz et al., 2017). Immune factor concentrations were log transformed prior to statistical analysis. IgA was undetectable for one sample, TGFβ2 in one sample, and IL-10 in 118 samples. These values were assigned a value of one half the lower limit of detection, after log transformation.

Maternal and infant characteristics, diet diversity scores and maternal BMI

Maternal and infant age and infant sex were reported by participating mothers. Maternal BMI and diet diversity scores were calculated and used as a proxy for maternal condition. BMI and diet were chosen because of previous studies that have tested Trivers-Willard (e.g., Quinn, 2013; Fujita et al., 2012) and because they represent the best available data in an existing data set. Diet diversity has been consistently associated with food insecurity among breastfeeding and pregnant women (Kang et al., 2019; Na et al., 2016; Singh et al., 2020). Specifically in regard to maternal condition, DDS has been associated with maternal thinness and anemia in rural Cambodia (McDonald et al., 2015).

Maternal BMI was calculated from maternal height and weight measurements obtained by study personnel. BMI classifications were made according to US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines (CDC, 2021), with scores <18.5 considered underweight; 18.5 to < 25 as healthy, 25 to < 30 as overweight and ≥ 30 as obese. We combined overweight and obese categories with scores ≥ 25, defining the category as overweight/obese.

Diet diversity was characterized by creating a diet diversity score (DDS) for each subject based on the 2011 US Food and Agriculture (FAO) Guidelines for Measuring Household and Individual Dietary Diversity (Kennedy, Ballard & Dop, 2011). Mothers were asked to recall their food consumption over the past 7 days against a checklist of food groups. Data were used to create a DDS similar to the women’s diet diversity score included in the FAO guidelines (Kennedy, Ballard & Dop 2011). For creation of the DDS, the 14 dietary categories from the original diet survey responses were aggregated into 8 consolidated categories (i.e., starchy staples; vegetables; fruits; organ meat; meat and fish; eggs; legumes, nuts and seeds; milk and milk products). Responses were coded dichotomously, where for each category an affirmative response was coded as one and a negative was coded as zero. The DDS of each participant was calculated by summing the number of categories of consumed foods, with potential scores ranging from 0–8.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R (4.0.2). R package nlme (V 3.1–152) was used to create linear mixed-effects (LME) models to examine the potential relationship between concentrations of IgA, IgG, IgM, EGF, TGFβ2, IL-10, maternal characteristics that serve as a proxy for maternal condition (maternal BMI, maternal DDS), and infant sex (female or male). Each LME model included population as a random effect and infant age (wk) and maternal age (y) as fixed effects. In the LME models, BMI and diet diversity scores were treated as continuous variables, with higher BMI or diet diversity indicating better condition. However, since very high and low BMIs may also indicate poor condition, we also tested a second model with BMI as categorical variable according to the classifications described above (underweight, healthy and overweight/obese). Statistical significance was declared at P ≤ 0.05 and statistically trending at P > 0.05- ≤ 0.1. Additional models were run with the 240 datapoints from samples with IL-10 above the limit of detection; these models did not differ from the models with the complete sample in terms of qualitative inferences, so are not reported.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Of the 410 mothers from which we obtained milk samples in the original INSPIRE study, 358 mothers are included in this study. As noted, data from rural Ethiopia were excluded due to variation in sample preservation, and an additional 12 individuals from other populations were missing anthropometric (n =11) or dietary data (n = 1).

The mean maternal age was 27.8 years, ranging between 18–46 years. Infant age ranged from 2.9–16.6 weeks with a mean of 9 weeks old. There were some differences (e.g., BMI and maternal age) in participant characteristics among the cohorts; select characteristics are summarized in Table S1. There were no significant differences in maternal age, maternal BMI, or maternal DDS between mothers of male and female infants Table 1.

Table 1.

Maternal and infant characteristics by infant sex.

| Total Sample (n = 358) | Female (n = 182) | Male (n = 176) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | ||||

| Maternal age, y | 27.76 ± 6.19 | 27.34 ± 6.25 | 28.19 ± 6.12 | 0.193 |

| Maternal BMI, kg/m2 | 24.60 ± 4.60 | 24.24 ± 4.24 | 24.98 ± 4.90 | 0.126 |

| Maternal BMI category | ||||

| Underweight | 17.38 ± 0.90 | 17.33 ± 1.23 | 17.41 ± 0.57 | 0.163 |

| Healthy | 21.98 ± 1.73 | 24.24 ± 4.24 | 21.99 ± 1.81 | 0.616 |

| Overweight/Obese | 29.23 ± 3.67 | 28.67 ± 3.51 | 29.75 ± 3.76 | 0.476 |

| Maternal DDS | 6.11 ± 1.32 | 6.15 ± 1.31 | 6.06 ± 1.32 | 0.539 |

| Infants | ||||

| Infant age1, wk | 9.02 ± 2.89 | 9.15 ± 2.83 | 8.88 ± 2.93 | 0.375 |

Values are given as mean ± standard deviation. P values were calculated from Welch’s two sample t-test for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square for the categorical variables.

Infant age is equivalent to maternal time postpartum

Maternal BMI, Infant Sex, and HM Immune Factor Concentrations

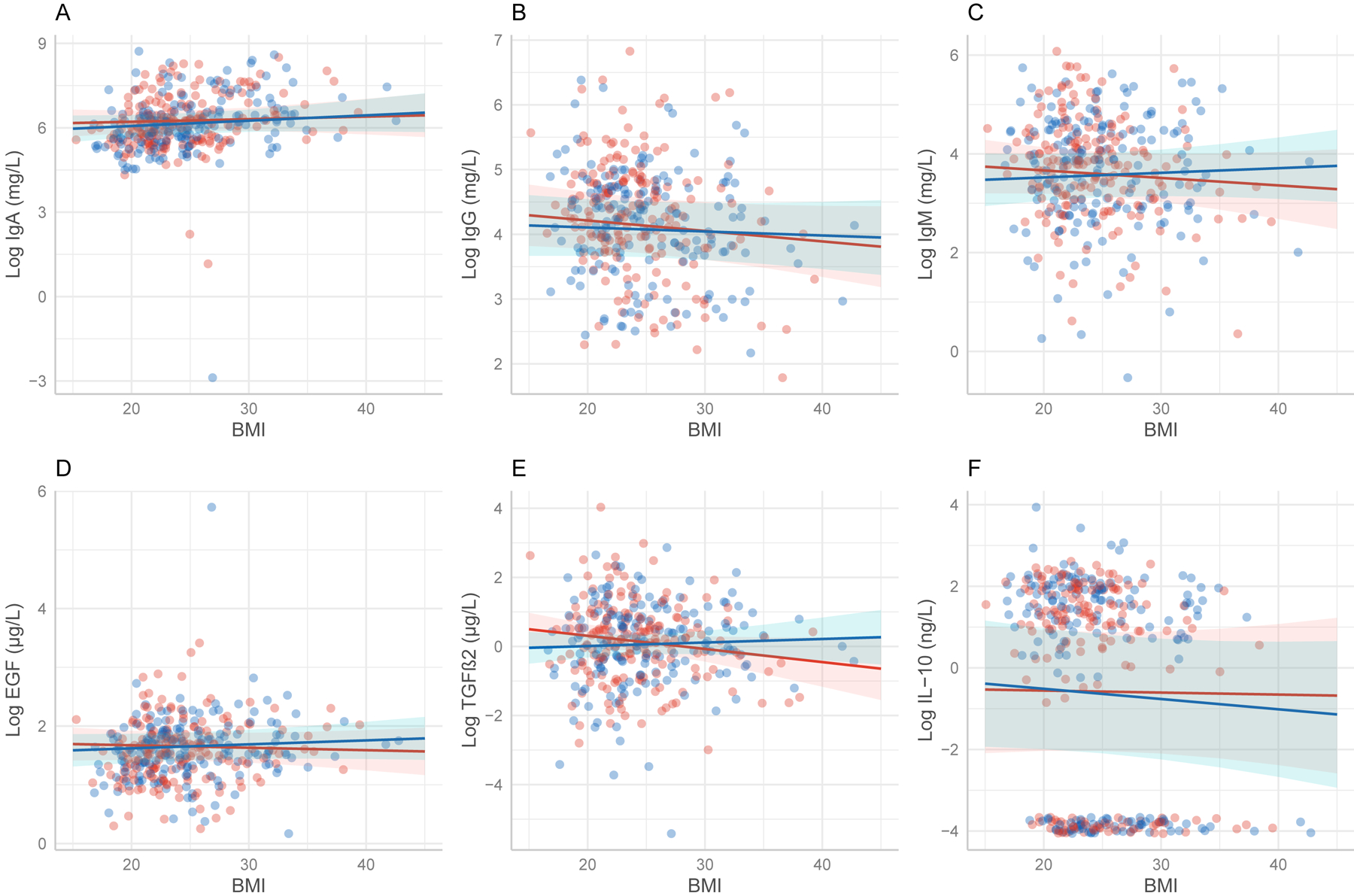

Among underweight and overweight/obese women, those with sons did not have lower concentrations of immune factors in their milk compared to women in similar condition with daughters. LME modeling indicated no significant interactions between infant sex and maternal BMI (as a continuous variable) on concentrations of IgA, IgG IgM, EGF, or IL-10 (Table 2, Figure 1). However, the interaction approached significance for TGFβ2 (β = 0.048, P = 0.07, Table 2, Figure 1). Mothers with BMIs < 26.5 kg/m2 with female infants trended towards higher concentrations of TGFβ2 in their milk than mothers with male infants and BMIs <26.5 kg/m2 (Figure 1). Other immune factors in our linear models, except for IL-10, followed the same overall pattern of higher concentrations in milk of mothers of female infants with lower BMI relative to those with male infants, and vice versa for higher BMI, but the differences were not significant.

Table 2.

Linear mixed-effects models examining variation in human milk immune factor concentrations with maternal body mass index (BMI) as a continuous predictor

| IgA1 | IgG1 | IgM1 | EGF2 | TGFβ22 | IL-103 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P |

| (Intercept) | 5.992 | <0.001 | 4.963 | <0.001 | 4.307 | <0.001 | 1.940 | <0.001 | 0.776 | 0.207 | −0.312 | 0.783 |

| Infant Sex4 | −0.350 | 0.497 | −0.306 | 0.374 | −0.634 | 0.214 | −0.270 | 0.272 | −1.261 | 0.058 | 0.449 | 0.630 |

| Maternal BMI | 0.009 | 0.587 | −0.016 | 0.151 | −0.015 | 0.360 | −0.004 | 0.603 | −0.038 | 0.075 | −0.005 | 0.872 |

| Infant Age5 | −0.018 | 0.292 | −0.003 | 0.776 | −0.029 | 0.083 | −0.010 | 0.232 | 0.048 | 0.029 | 0.011 | 0.728 |

| Maternal Age | 0.008 | 0.400 | −0.014 | 0.015 | −0.003 | 0.760 | −0.004 | 0.408 | −0.005 | 0.648 | −0.009 | 0.581 |

| Infant Sex:Maternal BMI | 0.010 | 0.631 | 0.010 | 0.471 | 0.025 | 0.229 | 0.011 | 0.268 | 0.048 | 0.070 | −0.020 | 0.588 |

|

Random effects Population (Intercept, residual) |

0.551 | 0.875 | 0.673 | 0.585 | 0.690 | 0.866 | 0.370 | 0.418 | 0.355 | 1.129 | 2.316 | 1.582 |

mg/L

μg/L

ng/L

Infant male coded as 1, female coded as 0

Infant age is equivalent to maternal time postpartum.

Figure 1.

Lines show predictions of linear mixed-effects models examining variation in human milk immune factor concentrations with maternal body mass index (BMI) as a continuous predictor. Shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals for the effect. A. IgA (β = 0.010, P = 0.631) B. IgG (β = 0.010, P = 0.471) C IgM (β = 0.025, P = 0.229) D. EGF (β = 0.011, P = 0.268) E.TGFβ2(β = 0.04, P = 0.268) F. IL-10 (β = 0.020, P = 0.588) All factors follow the same overall trend of higher concentrations in milk of mothers with male infants and higher BMI scores except for IL-10, however no relationships are significant.

Next, we ran models with BMI coded categorically to investigate non-linear effects of underweight and overweight/obese BMIs. Results showed general support for the use of BMI in linear terms. However, we present these results cautiously as this analysis may not be cross-culturally valid. Nevertheless, description of analysis and results are included in the supplementary (Table S2).

Maternal Diet Diversity, Infant Sex, and HM Immune Factor Concentrations

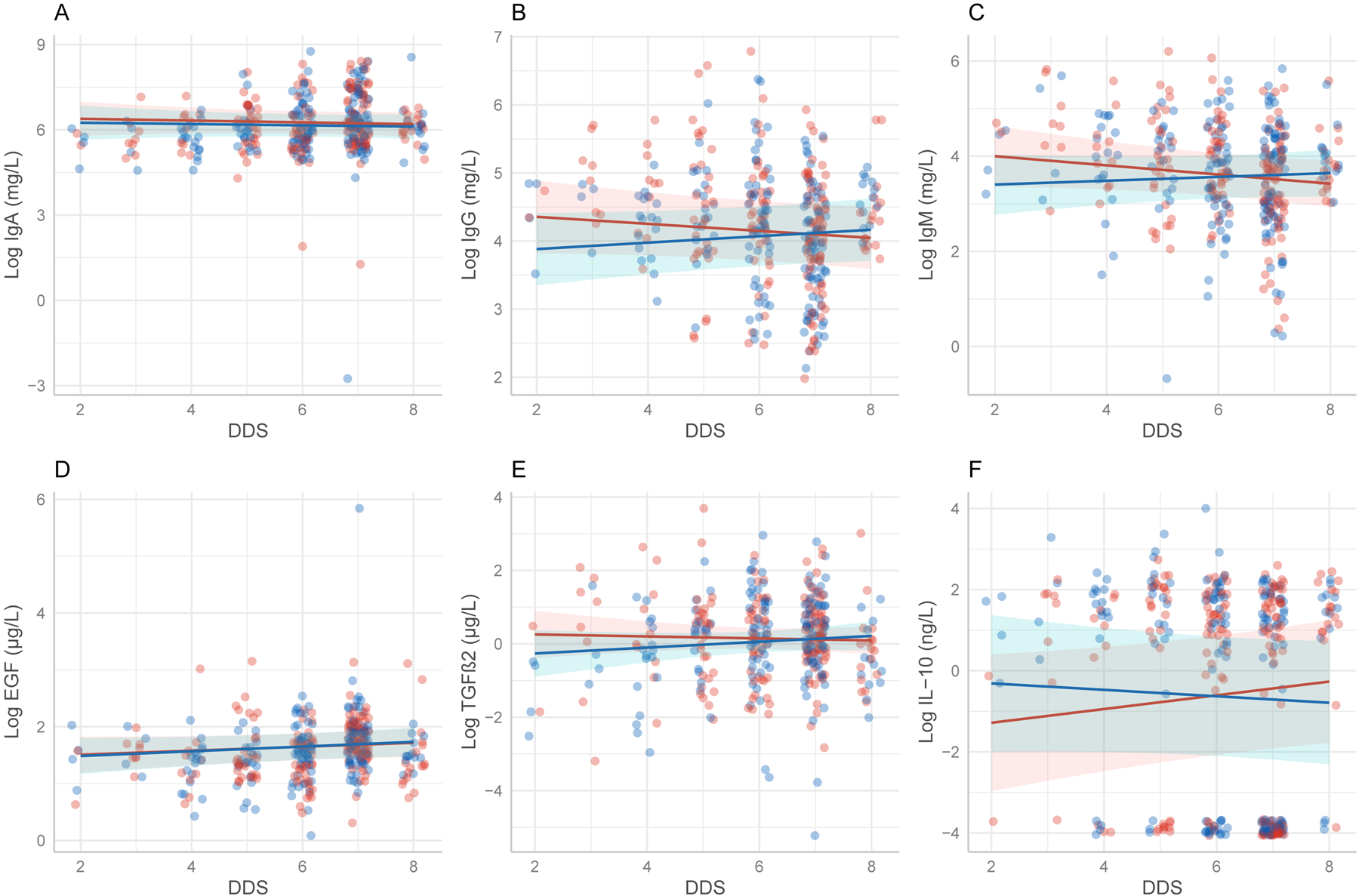

LME models showed an interaction between infant sex and maternal DDS on IgG concentration (β = 0.099, P = 0.037; Table 3). Specifically, mothers consuming less diverse diets with sons had lower concentrations of IgG in their milk compared to mothers in similar condition with daughters (Figure 2B). The interaction approached significance in the same direction for IgM (β = 0.137, P = 0.051; Table 3). However, mothers with high DDS and male infants trended towards lower concentrations of IL-10 in their milk compared to mothers with high DDS and female infants (β = −0.249, P= 0.052; Table 3, Figure 2F), but it was not significant.

Table 3.

Linear mixed-effects outputs for interaction between infant sex, immune factors and maternal diet diversity score (DDS)

| IgA1 | IgG1 | IgM1 | EGF2 | TGFβ22 | IL-103 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P |

| (Intercept) | 6.383 | <0.001 | 4.923 | <0.001 | 4.557 | <0.001 | 1.642 | <0.001 | 0.111 | 0.845 | −1.460 | 0.186 |

| Infant Sex4 | −0.156 | 0.725 | −0.671 | 0.024 | −0.870 | 0.047 | −0.037 | 0.861 | −0.732 | 0.201 | 1.469 | 0.067 |

| Maternal DDS | −0.032 | 0.575 | −0.052 | 0.173 | −0.096 | 0.084 | 0.035 | 0.197 | −0.027 | 0.702 | 0.169 | 0.098 |

| Infant Age5 | −0.021 | 0.222 | −0.003 | 0.803 | −0.031 | 0.062 | −0.011 | 0.176 | 0.047 | 0.032 | 0.016 | 0.590 |

| Maternal Age | 0.009 | 0.282 | −0.016 | 0.006 | −0.003 | 0.727 | −0.004 | 0.362 | −0.008 | 0.462 | −0.011 | 0.474 |

| Infant sex: Maternal DDS | 0.009 | 0.902 | 0.099 | 0.037 | 0.137 | 0.051 | 0.007 | 0.845 | 0.107 | 0.243 | −0.249 | 0.052 |

|

Random effects Population (Intercept, residuals) |

0.587 | 0.877 | 0.689 | 0.583 | 0.690 | 0.860 | 0.358 | 0.418 | 0.352 | 1.133 | 2.337 | 1.575 |

mg/L

μg/L

ng/L

Infant male coded as 1, female coded as 0

Infant age is equivalent to time postpartum

Figure 2.

a Diet Diversity Score = Score depicting the relative diversity of food categories consumed by participants. Lines show predictions of linear mixed-effects models examining interaction between infant sex, immune factors and maternal diet diversity score (DDS). Shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals for the effect. A. IgA (β = 0.009, P = 0.902) B.IgG (β = 0.009, P =0.037) C. IgM (β = 0.137, P =0.051) D.EGF (β = 0.007, P =0.845) E. TGFβ2 (β = 0.107, P = 0.243) F. IL-10 (β = −0.249 P =0.052) All factors follow the same overall trend of higher concentrations in milk of mothers with male infants and high diet diversity except for IL-10, however only IgG is significant.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated maternal biological investment via concentrations of human milk immune factors using predictions from the Trivers-Willard hypothesis. We tested whether concentrations of select immune factors (IgA, IgG, IgM, EGF, TGFβ2, and IL-10) would vary according to maternal condition and infant sex. Specifically, we examined whether concentrations of immune factors would be lower in the milk of mothers with underweight or overweight/obese BMI or low DDS (poor condition) with sons than in the milk of mothers with daughters and with underweight or overweight/obese BMI or low DDS.

We found minimal support for the Trivers-Willard hypothesis. Mothers consuming less diverse diets with male infants had significantly lower concentrations of IgG in their milk compared to mothers with less diverse diets with female infants. This finding is consistent with previous research that found female-biased investment among mothers in poor condition (with varying measures of condition, such as nourishment and economic stability) in the form of energy content (Powe et al., 2010) and fat content (Fujita et al., 2012) in humans. However, our results did not find support for a Trivers-Willard effect with any other immune factor tested with diet diversity or BMI as a measure of maternal condition. Additionally, no associations were found to support the prediction that underweight and overweight/obese women would have lower concentrations of immune factors in their milk for their sons than women in similar conditions with daughters.

Researchers have proposed that immune factors in milk are costly to produce, and the production of those factors are subject to life-history tradeoffs or shifts in energy expenditure (Miller, 2018; Breakey et al., 2015). The mechanism by which immune factors end up in human milk, however, may reflect their overall investment costs. Some immune factors (e.g., IgA) are synthesized in the mammary gland from B cells that migrate from the gastrointestinal tract during pregnancy (Roux, McWilliams, Phillips, Weisz-Carrington & Lamb, 1977). Others (e.g., cytokines) are produced by mammary epithelial cells or by cells carried within the milk, while some (e.g., IgG) are transferred from maternal serum (Agarwal et al., 2011) and may be more costly for mothers to produce. However, immune factors produced locally in the mammary gland may be less costly or require less energy for mothers to produce than those transferred from the maternal circulation (Butler et al., 2015). The exact costs of IgG, the only significant finding that supported the hypothesis, are unknown due to the lack of research on the impact of IgG transferring from maternal circulation to other sites, including the placenta and mammary gland. Therefore, if variation in human immune factors was responsive to the conditions posited in the Trivers-Willard hypothesis we would expect them to act on the more costly immune factors, which our results do not indicate.

Although it was not possible to test the maternal buffering hypothesis with our data, our results, which show no variation among most immune factors by maternal condition and infant sex, suggest some indirect support for the hypothesis that fluctuations in human milk immune factor concentrations are shielded against nutritional and dietary fluctuations (Fujita et al., 2019, Breakey et al., 2015). The maternal buffering hypothesis posits that milk composition is buffered against poor maternal condition and loss of essential nutrients due to food uncertainty that likely occurred in the evolutionary past (Fujita et al., 2019), except in extreme conditions (Miranda et al., 1983). This buffering may occur because primates, including humans, synthesize milk components from precursors obtained from both body stores and dietary intake (Hinde & Milligan, 2011), which may explain why studies have shown some human milk components to be resistant to short-term fluctuations in dietary intake (Fujita et al., 2019, Miranda et al., 1983; Prentice, Prentice, Cole, Paul & Whitehead, 1984). Therefore, the maternal buffering hypothesis may partially explain why we did not see a wider range of relationships between maternal condition and the immune factors in our study.

Potential limitations include our inclusion criteria of only enrolling women who self-reported as healthy. In order to conduct analyses cross-culturally and in multiple sites around the world, we used a broad definition of “healthy” which was determined by an inclusion/exclusion criterion of no reported illness seven days prior to enrollment and no antibiotics use a month prior to participation for mothers and infants and no symptoms of breast infection or atypical breast pain for mothers. However, as seen in the data, variance existed in maternal condition (i.e., BMI and DDS) despite all women self-identifying as healthy. Additionally, DDS are a measure of nutritional diversity, but they do not provide quantitative intake or account for fats and oil which are contributors to energy stores (Kennedy et al., 2011) and therefore may not be a comprehensive or definitive measure of nutritional status. As an indirect measure of body fat and obesity that relies solely on height and weight (Rothman, 2008), BMI may be reflective of poor condition in terms of mother’s overall health but may not reflect poor energy availability. Moreover, there are numerous known and potential unknown factors that influence variation in human milk immune factor concentrations (e.g., potential unknown genetic influences). Here, we only tested a limited range of those factors through measures that were available to us, diet diversity and BMI scores, in this secondary data analysis.

Consideration of Trivers-Willard Hypothesis in Human Parental Investment Studies

The Trivers-Willard hypothesis has had a lasting impact on human parental investment studies (Hrdy, 1987; Cronk, 2007; Veller, Haig & Nowak, 2016). There is some support for Trivers-Willard hypothesis effect in humans when looking at sex ratio (Cronk, 2007, Thouzeau et al., 2007). However, most studies extending the Trivers-Willard hypothesis into investigations on post-birth investment continue to be challenged by small sample sizes (Cronk, 2007) and operationalization difficulties in regard to maternal condition and parental investment (Cronk, 2007 Veller, Haig & Nowak 2016). The operational variability in defining maternal condition is in part because “condition” is a theoretical and general term related to an individual’s ability to contribute to fitness (Trivers & Willard 1973), but in practice condition is a multidimensional construct. Ideally, multiple aspects of maternal condition should be simultaneously considered [e.g., social economic status, access to resources, social support, environmental and mortality risk, physical characteristics (BMI, body measurements), and health conditions]. However, this remains challenging for many studies, particularly as noted above with sample size or in secondary analyses such as those presented here. Individuals may have high condition in some domains and low condition in others [e.g., high body mass index (BMI) and low diet diversity] and consensus on how to measure a holistic ‘maternal condition’ in a complex species like humans has yet to be and may never be obtained. Additionally, there is no general pattern of human parental investment and facultative biasing of investment may depend on parent’s local ecology (Quinn, 2013; Cronk, 2007, Hrdy 1987). For example, parents in one locale may reduce parental investment in one domain in response to environmental or condition cues, while parents in another location may reduce investment in a different domain. Moreover, humans require multiple forms of parental investment to achieve reproductive success (Quinlan, Quinlan & Flinn., 2003) and receive investment from multiple caregivers (Meehan et al., 2005; Helfrecht, Roulette, Lane, Sintayehu & Meehan, 2020), further complicating the testing of Trivers-Willard hypothesis in human populations. While our study was able to control for some of these challenges (e.g., larger sample size, cross-cultural sample), we were certainly not able to control for all (e.g., the possibility of locally relevant facultative investment domains).

As these challenges cannot likely ever be fully or adequately addressed in a species as complex as humans, perhaps, and as noted by others (Cronk, 2007; Quinn, 2013; Veller, Haig & Nowak, 2016;), predictions from Trivers-Willard hypothesis may not be relevantly applicable to post-birth human parental investment. Nevertheless, and of concern, the Trivers-Willard hypothesis is either directly or indirectly referenced as a framework for understanding variation in human milk factors, but rarely explicitly tested [with the exception of Quinn (2013) and Fujita et al., 2012)]. We argue that evidence for the Trivers-Willard hypothesis is limited and suggest it does not apply as a general framework to explain variation in human milk immune factors or milk composition. We advise caution in use and skepticism of its explanatory power for milk factors and post-birth investment.

In summary, we found only limited support for the use of Trivers-Willard hypothesis in explaining variation in human milk immune factors. We found only one significant relationship between maternal DDS, infant sex and concentrations of IgG; no other relationships were significant. Specifically, we found that IgG concentrations were lower in the milk of mothers with male infants consuming low diversity diets than in the milk of mothers with female infants consuming low diversity diets. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to test the Trivers-Willard hypothesis on human milk composition and to investigate variance of IgG, IgM, and IL-10 concentrations within this framework. This study contributes to our understanding of the relationship between maternal-infant health and milk immune composition. These findings add the investigation of human milk as a form of biological investment and human milk composition as subject to parental investment tradeoffs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is supported with funds from the National Science Foundation’s INSPIRE Track 1 Grant: What is Normal Milk? Sociocultural, Evolutionary, Environmental, and Microbial Aspects of Human Milk Composition (Award #1344288), National Institutes of Health NICHD R01 HD092297 and the US Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch project IDA01643 and in-kind donations from Medela. We sincerely thank the Washington State University Health Equity Center for their support. Additionally, we thank Andrew Doel (Medical Research Council Unit, The Gambia) for field supervision and logistics planning and Alansan Sey for questionnaire administration and taking anthropometric measurements in The Gambia; Jane Odei (University of Ghana) for supervising field data collection in Ghana; Haile Belachew (Hawassa University), and Birhanu Sintayehu for planning and logistics and the administration and staff at Adare Hospital in Hawassa for assistance with logistics in Ethiopia; Catherine O Sarange (Egerton University) for field supervision and logistics planning and Milka W. Churuge and Minne M Gachau for recruiting, questionnaire administration, and taking anthropometric measurements in Kenya; Gisella Barbagelatta (Instituto de Investigación Nutricional) for field supervision and logistics planning, Patricia Calderon (Instituto de Investigación Nutricional) for recruiting, questionnaire administration, and taking anthropometric measurements, and Roxana Barrutia (Instituto de Investigación Nutricional) for the management and shipping of samples in Peru; Leónides Fernández, Cristina García-Carral and Irene Espinosa (Complutense University of Madrid) for technical assistance and expertise, and M Ángeles Checa (Zaragoza, Spain), Katalina Legarra (Guernica, Spain), and Julia Mínguez (Huesca, Spain) for participation in the collection of samples in Spain; Kirsti Kaski and Maije Sjöstrand (both Helsingborg Hospital) for participation in the collection of samples, questionnaire administration, and anthropometric measurements in Sweden; Renee Bridge and Kara Sunderland (both University of California, San Diego); Janae Carrothers and Shelby Hix (Washington State University) for logistics planning, recruiting, questionnaire administration, sample collection, and taking anthropometric measurements in California and Washington; Glenn Miller (Washington State University) for his expertise and critical logistic help that were needed for shipping samples and supplies worldwide.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Agarwal S, Karmaus W, Davis S, & Gangur V (2011). Review: Immune markers in breast milk and fetal and maternal body fluids: a systematic review of perinatal concentrations. Journal of Human Lactation : official journal of International Lactation Consultant Association, 27(2), 171–186. 10.1177/0890334410395761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoudruz P, Holmlund U, Schollin J, Sverremark‐Ekström E, & Montgomery SM (2009). Maternal country of birth and previous pregnancies are associated with breast milk characteristics. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 20(1), 19–29. 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2008.00754.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreas NJ, Kampmann B, & Mehring Le-Doare K (2015). Human breast milk: A review on its composition and bioactivity. Early Human Development, 91(11), 629–635. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard O, & Morrow AL (2013). Human milk composition: nutrients and bioactive factors. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 60(1), 49–74. 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereczkei T, & Dunbar RIM (1997). Female-biased reproductive strategies in a Hungarian Gypsy population. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 264(1378), 17–22. 10.1098/rspb.1997.0003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binns C, Lee M, & Low WY (2016). The Long-Term Public Health Benefits of Breastfeeding. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 28(1), 7–14. 10.1177/1010539515624964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher MF, Abrahamsson TR, Fredriksson M, Jakobsson T, & Björkstén B (2008). Low breast milk TGF-β2 is induced by Lactobacillus reuteri supplementation and associates with reduced risk of sensitization during infancy. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 19(6), 497–504. 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00687.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtzaeg P (2003). Mucosal immunity: integration between mother and the breast-fed infant. Vaccine, 21(24), 3382–3388. 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00338-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breakey AA, Hinde K, Valeggia CR, Sinofsky A, & Ellison PT (2015). Illness in breastfeeding infants relates to concentration of lactoferrin and secretory Immunoglobulin A in mother’s milk. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, (1), 21–31. 10.1093/emph/eov002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan D-L, Hart PH, Forsyth KD, & Gibson RA (2007). Immunomodulatory constituents of human milk change in response to infant bronchiolitis. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 18(6), 495–502. 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00565.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JE, Rainard P, Lippolis J, Salmon H, & Kacskovics I (2015). The Mammary Gland in Mucosal and Regional Immunity. In Mucosal Immunology (pp. 2269–2306). Elsevier. 10.1016/B978-0-12-415847-4.00116-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butte NF, & King JC (2005). Energy requirements during pregnancy and lactation. Public Health Nutrition, 8(7A), 1010–1027. 10.1079/phn2005793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellote C, Casillas R, Ramírez-Santana C, Pérez-Cano FJ, Castell M, Moretones MG, López-Sabater MC, & Franch A (2011). Premature delivery influences the immunological composition of colostrum and transitional and mature human milk. The Journal of Nutrition, 141(6), 1181–1187. 10.3945/jn.110.133652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro I, García-Carral C, Furst A, Khwajazada S, García J, Arroyo R, Ruiz L, Rodríguez JM, Bode L, & Fernández L (2022). Interactions between human milk oligosaccharides, microbiota and immune factors in milk of women with and without mastitis. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1367. 10.1038/s41598-022-05250-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2021). Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html [Google Scholar]

- Cronk L (2007). Boy or girl: gender preferences from a Darwinian point of view. Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 15, 23–32. 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60546-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czosnykowska-Łukacka M, Lis-Kuberka J, Królak-Olejnik B, & Orczyk-Pawiłowicz M (2020). Changes in Human Milk Immunoglobulin Profile During Prolonged Lactation. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 8. 10.3389/fped.2020.00428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawod B, & Marshall JS (2019). Cytokines and Soluble Receptors in Breast Milk as Enhancers of Oral Tolerance Development. Frontiers in Immunology, 10. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak B (2010). Milk Epidermal Growth Factor and Gut Protection. The Journal of Pediatrics, 156(2), S31–S35. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckart EK, Peck JD, Kharbanda EO, Nagel EM, Fields DA, & Demerath EW (2021). Infant sex differences in human milk intake and composition from 1- to 3-month post-delivery in a healthy United States cohort. Annals of Human Biology, 48(6), 455–465. 10.1080/03014460.2021.1998620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escuder-Vieco D, Espinosa-Martos I, Rodríguez JM, Fernández L, & Pallás-Alonso CR (2018). Effect of HTST and Holder Pasteurization on the Concentration of Immunoglobulins, Growth Factors, and Hormones in Donor Human Milk. Frontiers in Immunology, 9, 2222. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Martos I, Montilla A, de Segura AG, Escuder D, Bustos G, Pallás C, Rodríguez JM, Corzo N, & Fernández L (2013). Bacteriological, biochemical, and immunological modifications in human colostrum after Holder pasteurisation. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 56(5), 560–568. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31828393ed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Martos I, Jiménez E, de Andrés J, Rodríguez-Alcalá LM, Tavárez S, Manzano S, Fernández L, Alonso E, Fontecha J, & Rodríguez JM (2016). Milk and blood biomarkers associated to the clinical efficacy of a probiotic for the treatment of infectious mastitis. Beneficial Microbes, 7(3), 305–318. 10.3920/BM2015.0134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Roth E, Lo Y-J, Hurst C, Vollner J, & Kendell A (2012). In poor families, mothers’ milk is richer for daughters than sons: A test of Trivers-Willard hypothesis in agropastoral settlements in Northern Kenya. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 149(1), 52–59. 10.1002/ajpa.22092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Wander K, Paredes Ruvalcaba N, & Brindle E (2019). Human milk sIgA antibody in relation to maternal nutrition and infant vulnerability in northern Kenya. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, (1), 201–211. 10.1093/emph/eoz030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galante L, Milan AM, Reynolds CM, Cameron-Smith D, Vickers MH, & Pundir S (2018). Sex-Specific Human Milk Composition: The Role of Infant Sex in Determining Early Life Nutrition. Nutrients, 10(9). 10.3390/nu10091194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman AS, Goldblum RM, & Garza C (1983). Immunologic components in human milk during the second year of lactation. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica, 72(3), 461–462. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1983.tb09748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RL, Wallace JP, Gfell LE, Marks J, King BA. 1997. Effect of exercise on milk immunoglobulin A. Med Sci Sports Exercise 29: 1596–1601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groer M, Davis M, & Steele K (2004). Associations between Human Milk SIgA and Maternal Immune, Infectious, Endocrine, and Stress Variables. Journal of Human Lactation, 20(2), 153–158. 10.1177/0890334404264104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson LA, & Korotkova M (2002). The role of breastfeeding in prevention of neonatal infection. Seminars in Neonatology : SN, 7(4), 275–281. 10.1016/s1084-2756(02)90124-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassiotou F, Hepworth AR, Metzger P, Tat Lai C, Trengove N, Hartmann PE, & Filgueira L (2013). Maternal and infant infections stimulate a rapid leukocyte response in breastmilk. Clinical & Translational Immunology, 2(4), e3. 10.1038/cti.2013.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrecht, Roulette JW, Lane A, Sintayehu B, & Meehan CL (2020). Life history and socioecology of infancy. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 173(4), 619–629. 10.1002/ajpa.24145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde K, & Milligan LA (2011). Primate milk: proximate mechanisms and ultimate perspectives. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 20(1), 9–23. 10.1002/evan.20289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmlund U, Amoudruz P, Johansson MA, Haileselassie Y, Ongoiba A, Kayentao K, Traoré B, Doumbo S, Schollin J, Doumbo O, Montgomery SM, & Sverremark‐Ekström E (2010). Maternal country of origin, breast milk characteristics and potential influences on immunity in offspring. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 162(3), 500–509. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04275.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt KM, Williams JE, Shafii B, Hunt MK, Behre R, Ting R, McGuire MK, & McGuire MA (2013). Mastitis is associated with increased free fatty acids, somatic cell count, and interleukin-8 concentrations in human milk. Breastfeeding Medicine, 8(1), 105–110. 10.1089/bfm.2011.0141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarah H (1987). Sex-Biased Parental Investment Among Primates and Other Mammals: A Critical Evaluation of the Trivers-Willard Hypothesis. In Gelles RJ & Lancaster JB (Eds.), Child Abuse and Neglect (pp. 97–147). Aldine De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Kalkwarf HJ, & Specker BL (2002). Bone mineral changes during pregnancy and lactation. Endocrine, 17(1), 49–53. 10.1385/ENDO:17:1:49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Hurley KM, Ruel-Bergeron J, Monclus AB, Oemcke R, Wu LSF, Mitra M, Phuka J, Klemm R, West KP, & Christian P (2019). Household food insecurity is associated with low dietary diversity among pregnant and lactating women in rural Malawi. Public health nutrition, 22(4), 697–705. 10.1017/S1368980018002719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy G, Ballard T, Dop M(2011). Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity. FAO. https://www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/5aacbe39-068f-513b-b17d-1d92959654ea/ [Google Scholar]

- Klein LD, Huang J, Quinn EA, Martin MA, Breakey AA, Gurven M, Kaplan H, Valeggia C, Jasienska G, Scelza B, Lebrilla CB, & Hinde K (2018). Variation among populations in the immune protein composition of mother’s milk reflects subsistence pattern. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, (1), 230–245. 10.1093/emph/eoy031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SL, & Flanagan KL (2016). Sex differences in immune responses. Nature Reviews Immunology, 16(10), 626–638. 10.1038/nri.2016.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackey KA, Williams JE, Meehan CL, Zachek JA, Benda ED, Price WJ, Foster JA, Sellen DW, Kamau-Mbuthia EW, Kamundia EW, Mbugua S, Moore SE, Prentice AM, K DG, Kvist LJ, Otoo GE, García-Carral C, Jiménez E, Ruiz L, Rodríguez JM, … McGuire MK (2019). What’s Normal? Microbiomes in Human Milk and Infant Feces Are Related to Each Other but Vary Geographically: The INSPIRE Study. Frontiers in Nutrition, 6, 45. 10.3389/fnut.2019.00045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane AA, McGuire MK, McGuire MA, Williams JE, Lackey KA, Hagen EH, Kaul A, Gindola D, Gebeyehu D, Flores KE, Foster JA, Sellen DW, Kamau-Mbuthia EW, Kamundia EW, Mbugua S, Moore SE, Prentice AM, Kvist LJ, Otoo GE, … Meehan CL (2019). Household composition and the infant fecal microbiome: The INSPIRE study. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 169(3), 526–539. 10.1002/ajpa.23843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Jiang J, Wu K, & Li D (2018). Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-α in human milk of different lactation stages and different regions and their relationship with maternal diet. Food & Function, 9(2), 1199–1204. 10.1039/C7FO00770A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn PG (1994). Lactation and other metabolic loads affecting human reproduction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 709, 77–85. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb30389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Wasielewski H, & Cronk L (2018). Sexual conflict and the Trivers-Willard hypothesis: Females prefer daughters and males prefer sons. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 15463–13. 10.1038/s41598-018-33650-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na M, Mehra S, Christian P, Ali H, Shaikh S, Shamim AA, Labrique AB, Klemm RD, Wu LS, & West KP Jr (2016). Maternal Dietary Diversity Decreases with Household Food Insecurity in Rural Bangladesh: A Longitudinal Analysis. The Journal of nutrition, 146(10), 2109–2116. 10.3945/jn.116.234229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan CL (2005). The effects of residential locality on parental and alloparental investment among the Aka foragers of the Central African Republic. Human Nature, 16(1), 58–80. 10.1007/s12110-005-1007-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CM, McLean J, Kroeun H, Talukder A, Lynd LD, & Green TJ (2015). Household food insecurity and dietary diversity as correlates of maternal and child undernutrition in rural Cambodia. European journal of clinical nutrition, 69(2), 242–246. 10.1038/ejcn.2014.161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire MK, Meehan CL, McGuire MA, Williams JE, Foster J, Sellen DW, Kamau-Mbuthia EW, Kamundia EW, Mbugua S, Moore SE, Prentice AM, Kvist LJ, Otoo GE, Brooker SL, Price WJ, Shafii B, Placek C, Lackey KA, Robertson B, Manzano S, … Bode L (2017). What’s normal? Oligosaccharide concentrations and profiles in milk produced by healthy women vary geographically. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 105(5), 1086–1100. 10.3945/ajcn.116.139980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire MK, Randall AZ, Seppo AE, Järvinen KM, Meehan CL, Gindola D, Williams JE, Sellen DW, Kamau-Mbuthia EW, Kamundia EW, Mbugua S, Moore SE, Prentice AM, Foster JA, Otoo GE, Rodríguez JM, Pareja RG, Bode L, McGuire MA, & Campo JJ (2021). Multipathogen Analysis of IgA and IgG Antigen Specificity for Selected Pathogens in Milk Produced by Women From Diverse Geographical Regions: The INSPIRE Study. Frontiers in Immunology, 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2020.614372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EM (2018). Ecological immunity of human milk: Life history perspectives from the United States and Kenya. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 167(2), 389–399. 10.1002/ajpa.23639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Saravia NG, Ackerman R, Murphy N, Berman S, & McMurray DN (1983). Effect of maternal nutritional status on immunological substances in human colostrum and milk. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 37(4), 632–640. 10.1093/ajcn/37.4.632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moles L, Manzano S, Fernández L, Montilla A, Corzo N, Ares S, Rodríguez JM, & Espinosa-Martos I (2015). Bacteriological, biochemical, and immunological properties of colostrum and mature milk from mothers of extremely preterm infants. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 60(1), 120–126. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munblit D, Treneva M, Peroni DG, Colicino S, Chow L, Dissanayeke S, Abrol P, Sheth S, Pampura A, Boner AL, Geddes DT, Boyle RJ, & Warner JO (2016). Colostrum and Mature Human Milk of Women from London, Moscow, and Verona: Determinants of Immune Composition. Nutrients, 8(11). 10.3390/nu8110695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa J, Sasahara A, Yoshida T, Mohamed Sira M, Futatani T, Hirokazu K, & Toshio M (2004). Role of transforming growth factor-beta in breast milk for initiation of IgA production in newborn infants. Early Human Development, 77(1–2), 67–75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15113633/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace RM, Williams JE, Robertson B, Lackey KA, Meehan CL, Price WJ, Foster JA, Sellen DW, Kamau-Mbuthia EW, Kamundia EW, Mbugua S, Moore SE, Prentice AM, Kita DG, Kvist LJ, Otoo GE, Ruiz L, Rodríguez JM, Pareja RG,… McGuire MK (2021). Variation in Human Milk Composition Is Related to Differences in Milk and Infant Fecal Microbial Communities. Microorganisms, 9(6), 1153. 10.3390/microorganisms9061153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmeira P, & Carneiro-Sampaio M (2016). Immunology of breast milk. Revista Da Associação Médica Brasileira, 62(6), 584–593. 10.1590/1806-9282.62.06.584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peroni DG, Pescollderungg L, Piacentini GL, Rigotti E, Maselli M, Watschinger K, Piazza M, Pigozzi R, & Boner AL (2010). Immune regulatory cytokines in the milk of lactating women from farming and urban environments. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 21(6), 977–982. 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.00995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pink KE, Schaman A, & Fieder M (2017). Sex Differences in Intergenerational Income Transmission and Educational Attainment: Testing the Trivers-Willard Hypothesis. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powe CE, Knott CD, & Conklin-Brittain N (2010). Infant sex predicts breast milk energy content. American Journal of Human Biology, 22(1), 50–54. 10.1002/ajhb.20941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice A, Prentice AM, Cole TJ, Paul AA, & Whitehead RG (1984). Breast-milk antimicrobial factors of rural Gambian mothers. I. Influence of stage of lactation and maternal plane of nutrition. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica, 73(6), 796–802. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1984.tb17778.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice Prentice AM, Cole TJ, & Whitehead RG (1983). Determinants of variations in breast milk protective factor concentrations of rural Gambian mothers. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 58(7), 518–522. 10.1136/adc.58.7.518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice A, Prentice AM, & Lamb WH (1985). Mastitis in rural Gambian mothers and the protection of the breast by milk antimicrobial factors. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 79(1), 90–95. 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90245-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice A, Watkinson M, Prentice AM, Cole TJ, & Whitehead RG (1984). Breast-milk antimicrobial factors of rural Gambian mothers. II. Influence of season and prevalence of infection. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica, 73(6), 803–809. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1984.tb17779.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn EA (2013). No evidence for sex biases in milk macronutrients, energy, or breastfeeding frequency in a sample of filipino mothers American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 152: 209–216. 10.1002/ajpa.22346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan RJ, Quinlan MB, & Flinn MV (2003). Parental investment and age at weaning in a Caribbean village. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24(1), 1–16. 10.1016/S1090-5138(02)00104-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riskin A, Almog M, Peri R, Halasz K, Srugo I, & Kessel A (2012). Changes in immunomodulatory constituents of human milk in response to active infection in the nursing infant. Pediatric Research, 71(2), 220–225. 10.1038/pr.2011.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez JM, Fernández L, & Verhasselt V (2021). The Gut‒Breast Axis: Programming Health for Life. Nutrients, 13(2), 606. 10.3390/nu13020606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ (2008). BMI-related errors in the measurement of obesity. International journal of obesity (2005), 32 Suppl 3, S56–S59. 10.1038/ijo.2008.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux ME, McWilliams M, Phillips-Quagliata JM, Weisz-Carrington P, & Lamm ME (1977). Origin of IgA-secreting plasma cells in the mammary gland. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 146(5), 1311–1322. 10.1084/jem.146.5.1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz L, Espinosa-Martos I, García-Carral C, Manzano S, McGuire MK, Meehan CL, McGuire MA, Williams JE, Foster J, Sellen DW, Kamau-Mbuthia EW, Kamundia EW, Mbugua S, Moore SE, Kvist LJ, Otoo GE, Lackey KA, Flores K, Pareja RG, Bode L,… Rodríguez JM (2017). What’s Normal? Immune Profiling of Human Milk from Healthy Women Living in Different Geographical and Socioeconomic Settings. Frontiers in Immunology, 8, 696. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh DR, Ghimire S, Upadhayay SR, Singh S, & Ghimire U (2020). Food insecurity and dietary diversity among lactating mothers in the urban municipality in the mountains of Nepal. PloS one, 15(1), e0227873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striker GAJ, Casanova LD, & Nagao AT (2004). Influence of type of delivery on A, G and M immunoglobulin concentration in maternal colostrum. Jornal De Pediatria, 80(2), 123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song. (2018). Spending patterns of Chinese parents on children’s backpacks support the Trivers-Willard hypothesis. Evolution and Human Behavior, 39(3), 336–342. 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2018.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thouzeau V, Bollée J, Cristia A, & Chevallier C (2022). Decades of Trivers-Willard research on humans: what conclusions can be drawn? BioRxiv, 2022.08.22.504743. 10.1101/2022.08.22.504743 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomicić S, Johansson G, Voor T, Björkstén B, Böttcher MF, & Jenmalm MC (2010). Breast milk cytokine and IgA composition differ in Estonian and Swedish mothers-relationship to microbial pressure and infant allergy. Pediatric Research, 68(4), 330–334. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181ee049d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracer DP (2009). Breastfeeding structure as a test of parental investment theory in Papua New Guinea. American Journal of Human Biology, 21(5), 635–642. 10.1002/ajhb.20928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivers RL, & Willard DE (1973). Natural selection of parental ability to vary the sex ratio offspring. Science (New York, N.Y.), 179 (4068), 90–92. 10.1126/science.179.4068.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turin CG, & Ochoa TJ (2014). The Role of Maternal Breast Milk in Preventing Infantile Diarrhea in the Developing World. Current Tropical Medicine Reports, 1(2), 97–105. 10.1007/s40475-014-0015-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwin HJ, Miles EA, Noakes PS, Kremmyda L-S, Vlachava M, Diaper ND, Pérez-Cano FJ, Godfrey KM, Calder PC, & Yaqoob P (2012). Salmon consumption during pregnancy alters fatty acid composition and secretory IgA concentration in human breast milk. The Journal of Nutrition, 142(8), 1603–1610. 10.3945/jn.112.160804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valeggia C, & Ellison PT (2001). Lactation, Energetics, and Postpartum Fecundity. In Ellison PT (Ed.), Reproductive Ecology and Human Evolution (pp. 85–106). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Veller Haig D, & Nowak MA (2016). The Trivers–Willard hypothesis: sex ratio or investment? Proceedings of the Royal Society. B, Biological Sciences, 283(1830), 20160126–. 10.1098/rspb.2016.0126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver LT, Arthur HML, Bunn JEG, & Thomas JE (1998). Human milk IgA concentrations during the first year of lactation. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 78(3), 235–239. 10.1136/adc.78.3.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.